| Revision as of 12:53, 7 May 2010 view sourcePaul August (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators205,543 edits Undid revision 360521082 by 216.226.127.15 (talk)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:36, 9 January 2025 view source Llorano (talk | contribs)133 editsm Adding link to 'Troy'Tag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Epic poem attributed to Homer}} | |||

| {{this|Homer's epic poem}} | |||

| {{ |

{{about|Homer's epic poem|other uses|Odyssey (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{redirect|Homer's Odyssey|''The Simpsons'' episode|Homer's Odyssey (The Simpsons){{!}}Homer's Odyssey (''The Simpsons'')}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Italic title}} | |||

| The '''''Odyssey''''' ({{lang-el|Ὀδύσσεια}}, ''Odýsseia'') is one of two major ancient ] ]s attributed to ]. It is, in part, a sequel to the '']'', the other work traditionally ascribed to Homer. The poem is fundamental to the modern ]. Indeed it is the second—the ''Iliad'' being the first—extant work of Western literature. It was probably composed near the end of the eighth century BC, somewhere in ], the Greek-speaking coastal region of what is now ].<ref name="The Odyssey 2003">]'s introduction to ''The Odyssey'' (Penguin, 2003), p. ''xi''.</ref> | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-protect|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox poem | |||

| | name = ''Odyssey'' | |||

| | image = Odyssey-crop.jpg | |||

| | image_size = | |||

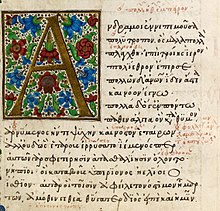

| | caption = 15th-century manuscript of Book I written by scribe ] (]) | |||

| | subtitle = | |||

| | author = ] | |||

| | publication_date_en = 1614 | |||

| | original_title = Ὀδύσσεια | |||

| | original_title_lang = el | |||

| | translator = ] and others; see ] | |||

| | written = {{circa|8th century BC}} | |||

| | first = | |||

| | illustrator = | |||

| | cover_artist = | |||

| | country = | |||

| | language = ] | |||

| | series = | |||

| | subject = | |||

| | genre = ] | |||

| | form = | |||

| | metre = ] | |||

| | rhyme = | |||

| | media_type = | |||

| | lines = 12,109 | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | size_weight = | |||

| | isbn = | |||

| | oclc = | |||

| | preceded_by = ] | |||

| | followed_by = | |||

| | wikisource = The Odyssey | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''''Odyssey''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɒ|d|ɪ|s|i}};<ref>" {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210216231120/https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/odyssey |date=16 February 2021 }}". ''Cambridge Dictionary''. Cambridge University Press, 2023.</ref> {{langx|grc|Ὀδύσσεια|Odýsseia}})<ref>{{LSJ|*)odu/sseia|Ὀδύσσεια|ref}}.</ref><ref>{{OEtymD|odyssey}}</ref> is one of two major ] ] attributed to ]. It is one of the oldest works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. Like the '']'', the ''Odyssey'' is divided into 24 ]. It follows the ] ], king of ], and his journey home after the ]. After the war, which lasted ten years, his journey from ] to Ithaca, via Africa and southern Europe, lasted for ten additional years during which time he encountered many perils and all of his crewmates were killed. In his absence, Odysseus was assumed dead, and his wife ] and son ] had to contend with a ] who were competing for Penelope's hand in marriage. | |||

| The poem mainly centers on the Greek hero ] (or Ulysses, as he was known in ] myths) and his long journey home following the fall of ]. It takes Odysseus ten years to reach ] after the ten-year ].<ref>The dog Argos dies ''autik' idont' Odusea eeikosto eniauto'' ("seeing Odysseus again in the twentieth year"), ; cf. also , , .</ref> In his absence, it is assumed he has died, and his wife ] and son ] must deal with a group of unruly suitors, the Mnesteres (Greek: Μνηστῆρες) or ], competing for Penelope's hand in marriage. | |||

| The ''Odyssey'' was originally composed in ] in around the 8th or 7th century BC and, by the mid-6th century BC, had become part of the Greek literary canon. In ], Homer's authorship of the poem was not questioned, but contemporary scholarship ] that the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'' were composed independently and that the stories formed as part of a long ]. Given widespread illiteracy, the poem was performed by an {{translit|grc|]}} or ] and was more likely to be heard than read. | |||

| It continues to be read in the ] and translated into modern languages around the world. The original poem was composed in an oral tradition by an ] (epic poet/singer), perhaps a ] (professional performer), and was intended more to be sung than read.<ref name="The Odyssey 2003"/> The details of the ancient oral performance, and the story's conversion to a written work inspire continual debate among scholars. The ''Odyssey'' was written in a regionless poetic dialect of Greek and comprises 12,110 lines of ].<ref>{{citation | |||

| |title=The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian | |||

| |last=Fox | |||

| |first=Robin Lane | |||

| |page=19 | |||

| |publisher=Basic Books | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |isbn=046502496 | |||

| }}.</ref><!-- some sources give a different number of lines, but 12,110 is the most often cited --> Among the most impressive elements of the text are its strikingly modern non-linear plot, and that events seem to depend as much on the choices made by women and serfs as on the actions of fighting men. In the ] as well as many others, the word ''odyssey'' has come to refer to an epic voyage. | |||

| Crucial themes in the poem include the ideas of {{lang|grc|]}} ({{lang|grc|νόστος}}; 'return'), wandering, {{translit|grc|]}} ({{lang|grc|ξενία}}; 'guest-friendship'), testing, and omens. Scholars still reflect on the narrative significance of certain groups in the poem, such as women and slaves, who have a more prominent role in the epic than in many other works of ancient literature. This focus is especially remarkable when contrasted with the ''Iliad'', which centres the exploits of soldiers and kings during the Trojan War. | |||

| ==Synopsis== | |||

| ], Odysseus's son, is only a month old when Odysseus sets out for Troy to fight a war he wants no part of.<ref>The Odyssey, Book XIV.</ref> At the point where the ''Odyssey'' begins, ten years after the end of the ten-year ], Telemachus is twenty and is sharing his absent father’s house on the island of Ithaca with his mother ] and a crowd of 118 boisterous young men, "the Suitors", whose aim is to persuade Penelope that her husband is dead and that she should marry one of them. | |||

| The ''Odyssey'' is regarded as one of the most significant works of the ]. The first ] of the ''Odyssey'' was in the 16th century. Adaptations and re-imaginings continue to be produced across ]. In 2018, when ''BBC Culture'' polled experts around the world to find literature's most enduring narrative, the ''Odyssey'' topped the list.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

| Odysseus’s protectress, the goddess ], discusses his fate with ], king of the gods, at a moment when Odysseus's enemy, the god of the sea ], is absent from ]. Then, disguised as a Taphian chieftain named ], she visits Telemachus to urge him to search for news of his father. He offers her hospitality; they observe the Suitors dining rowdily, and the bard ] performing a narrative poem for them. Penelope objects to Phemius's theme, the "Return from Troy"<ref>This theme once existed in the form of a written epic, '']'', now lost.</ref> because it reminds her of her missing husband, but Telemachus rebuts her objections. | |||

| == Synopsis == | |||

| That night, Athena disguised as Telemachus finds a ship and crew for the true Telemachus. The next morning, Telemachus calls an assembly of citizens of Ithaca to discuss what should be done to the suitors. Accompanied by Athena (now disguised as his friend ]), he departs for the Greek mainland and the household of ], most venerable of the Greek warriors at Troy, now at home in ]. From there, Telemachus rides overland, accompanied by Nestor's son, to ], where he finds ] and ], now reconciled. He is told that they returned to ] after a long voyage by way of ]; there, on the island of ], Menelaus encountered ], the daughter of the old sea-god ], who told him that Odysseus was a captive of the nymph ]. Incidentally, Telemachus learns the fate of Menelaus’ brother ], king of ] and leader of the Greeks at Troy, murdered on his return home by his wife ] and her lover ]. | |||

| ], ''] and ]'']] | |||

| ===Exposition (Books 1–4)=== | |||

| Then the story of Odysseus is told. He has spent seven years in captivity on Calypso's island. She is persuaded to release him by the messenger god ], who has been sent by Zeus in response to Athena's plea. Odysseus builds a raft and is given clothing, food and drink by Calypso. The raft is wrecked by Poseidon, but Odysseus swims ashore on the island of ], where, naked and exhausted, he hides in a pile of leaves and falls asleep. The next morning, awakened by the laughter of girls, he sees the young ], who has gone to the seashore with her maids to wash clothes. He appeals to her for help. She encourages him to seek the hospitality of her parents, ] and ]. Odysseus is welcomed and is not at first asked for his name. He remains for several days, takes part in a ], and hears the blind singer ] perform two narrative poems. The first is an otherwise obscure incident of the Trojan War, the "Quarrel of Odysseus and ]"; the second is the amusing tale of a love affair between two Olympian gods, ] and ]. Finally, Odysseus asks Demodocus to return to the Trojan War theme and tell of the ], a stratagem in which Odysseus had played a leading role. Unable to hide his emotion as he relives this episode, Odysseus at last reveals his identity. He then begins to tell the amazing story of his return from Troy. | |||

| ]' Song'', by ], 1813-15]] | |||

| After a piratical raid on ] in the land of the ], he and his twelve ships were driven off course by storms. They visited the lethargic ] and were captured by the ] ], only escaping by blinding him with a wooden stake. While they were escaping, however, Odysseus foolishly told Polyphemus his identity, and Polyphemus told his father, Poseidon, who blinded him. They stayed with ], the master of the winds; he gave Odysseus a leather bag containing all the winds, except the west wind, a gift that should have ensured a safe return home. However, the sailors foolishly opened the bag while Odysseus slept, thinking that it contained gold. All of the winds flew out and the resulting storm drove the ships back the way they had come, just as Ithaca came into sight. | |||

| ] depicting ], from the villa of ], ], Spain, late 4th–5th centuries AD]] | |||

| After pleading in vain with Aeolus to help them again, they re-embarked and encountered the cannibal ]. Odysseus’s ship was the only one to escape. He sailed on and visited the witch-goddess ]. She turned half of his men into swine after feeding them cheese and wine. Hermes warned Odysseus about Circe and gave Odysseus a drug called ], a resistance to Circe’s magic. Circe, being attracted to Odysseus' resistance, fell in love with him and released his men. Odysseus and his crew remained with her on the island for one year, while they feasted and drank. Finally, Odysseus' men convinced Odysseus that it was time to leave for Ithaca. Guided by Circe's instructions, Odysseus and his crew crossed the ocean and reached a harbor at the western edge of the world, where Odysseus sacrificed to the dead and summoned the spirit of the old prophet ] to advise him. Next Odysseus met the spirit of his own mother, who had died of grief during his long absence; from her, he learned for the first time news of his own household, threatened by the greed of the suitors. Here, too, he met the spirits of famous women and famous men; notably he encountered the spirit of Agamemnon, of whose murder he now learned, who also warned him about the dangers of women (for Odysseus' encounter with the dead, see also '']''). | |||

| The ''Odyssey'' begins after the end of the ten-year ] (the subject of the '']''), from which ] (also known by the Latin variant Ulysses), king of ], has still not returned because he angered ], the god of the sea. Odysseus's son, ], is about 20 years old and is sharing his absent father's house on the island of Ithaca with his mother ] and the ], a crowd of 108 boisterous young men who each aim to persuade Penelope for her hand in marriage, all the while reveling in the king's palace and eating up his wealth. | |||

| Returning to Circe’s island, they were advised by her on the remaining stages of the journey. They skirted the land of the ], passed between the six-headed monster ] and the whirlpool ], and landed on the island of ]. There, Odysseus’ men ignored the warnings of Tiresias and Circe, and hunted down the sacred cattle of the sun god ]. This sacrilege was punished by a shipwreck in which all but Odysseus drowned. He was washed ashore on the island of Calypso, where she compelled him to remain as her lover for seven years before escaping. | |||

| Odysseus's protectress, the goddess ], asks ], king of the ], to finally allow Odysseus to return home when Poseidon is absent from ]. Disguised as a chieftain named ], Athena visits Telemachus to urge him to search for news of his father. He offers her hospitality, and they observe the suitors dining rowdily while ], the ], performs a narrative poem for them. | |||

| Having listened with rapt attention to his story, the ], who are skilled mariners, agree to help Odysseus get home. They deliver him at night, while he is fast asleep, to a hidden harbor on Ithaca. He finds his way to the hut of one of his own former slaves, the swineherd ]. Athene disguises Odysseus as a wandering beggar in order to learn how things stand in his household. After dinner, he tells the farm laborers a fictitious tale of himself: he was born in ], had led a party of Cretans to fight alongside other Greeks in the Trojan War, and had then spent seven years at the court of the king of Egypt; finally he had been shipwrecked in ] and crossed from there to Ithaca. | |||

| Meanwhile, Telemachus sails home from Sparta, evading an ambush set by the suitors. He disembarks on the coast of Ithaca and makes for Eumaeus’s hut. Father and son meet; Odysseus identifies himself to Telemachus (but still not to Eumaeus) and they determine that the suitors must be killed. Telemachus gets home first. Accompanied by Eumaeus, Odysseus now returns to his own house, still pretending to be a beggar. He experiences the suitors’ rowdy behavior and plans their death. He meets Penelope and tests her intentions with an invented story of his birth in Crete, where, he says, he once met Odysseus. Closely questioned, he adds that he had recently been in Thesprotia and had learned something there of Odysseus’s recent wanderings. | |||

| That night, Athena, disguised as Telemachus, finds a ship and crew for the true prince. The next morning, Telemachus calls an assembly of citizens of Ithaca to discuss what should be done with the insolent suitors, who then scoff at Telemachus. Accompanied by Athena (now disguised as ]), the son of Odysseus departs for the Greek mainland to the household of ], most venerable of the Greek warriors at ], who resided in ] after the war. | |||

| Odysseus’s identity is discovered by the housekeeper, ], as she is washing his feet and discovers an old scar Odysseus received during a boar hunt. He received the scar when he was five years old and hunting with the sons of Autolycus. They had been told to go boar hunting so that they could prepare a meal with the meat. The three climbed Mount Parnassus and eventually came across a boar in a large and deep meadow. Because of the meadow's depth, the three hunters were ambushed by the seemingly invisible boar and when Odysseus first saw the animal, he rushed at it but the animal was too fast and slashed him in the right thigh. Despite being gored by the boar, Odysseus still hit his mark and stabbed the boar through the shoulder. Odysseus' bleeding was staunched by a spell that was chanted by the sons of Autolycus and he received great glory and treasure for his bravery<ref>Homer, and Stanley Lombardo. "Book XVIII." Odyssey. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2000. Print.</ref>. Having seen this scar, Eurycleia tries to tell Penelope about Odysseus' true identity, but Athena makes sure that Penelope cannot hear Eurykleia. Meanwhile Odysseus swears her to secrecy, threatening to kill her if she isn't. The next day, at Athena’s prompting, Penelope maneuvers the suitors into competing for her hand with an archery competition using Odysseus' bow. The man who can string the bow and shoot it through a dozen axe heads would win. Odysseus takes part in the competition himself; he alone is strong enough to string the bow and shoot it through the dozen axe heads, making him the winner. He turns his arrows on the suitors and with the help of Athena, Telemachus, Eumaeus and Philoteus the cowherd, all the suitors are killed. Odysseus and Telemachus hang twelve of their household maids, who betrayed Penelope and/or had sex with the suitors; they mutilate and kill the goatherd ], who had mocked and abused Odysseus. Now at last, Odysseus identifies himself to Penelope. She is hesitant, but accepts him when he mentions that their bed was made from an olive tree still rooted to the ground. Many modern and ancient scholars take this to be the original ending of the Odyssey, and the rest is an interpolation. | |||

| From there, Telemachus rides to ], accompanied by ]. There he finds ] and ], who are now reconciled. Both Helen and Menelaus also say that they returned to Sparta after a long voyage by way of Egypt. There, on the island of ], Menelaus encounters the old sea-god ], who tells him that Odysseus was a captive of the nymph ]. Telemachus learns the fate of Menelaus's brother, ], king of ] and leader of the Greeks at Troy: he was murdered on his return home by his wife ] and her lover ]. The story briefly shifts to the suitors, who have only just realized that Telemachus is gone. Angry, they formulate a plan to ambush his ship and kill him as he sails back home. Penelope overhears their plot and worries for her son's safety. | |||

| The next day he and Telemachus visit the country farm of his old father ], who likewise accepts his identity only when Odysseus correctly describes the orchard that Laertes once gave him. | |||

| ===Escape to the Phaeacians (Books 5–8)=== | |||

| The citizens of Ithaca have followed Odysseus on the road, planning to avenge the killing of the Suitors, their sons. Their leader points out that Odysseus has now caused the deaths of two generations of the men of Ithaca—his sailors, not one of whom survived, and the suitors, whom he has now executed. The goddess Athena intervenes and persuades both sides to give up the vendetta. After this, Ithaca is at peace once more, concluding the ''Odyssey''. Yet Odysseus' journey is not complete, as he is still fated to wander. The gods have decreed that Odysseus cannot rest until he wanders so far inland that he meets a people who have never heard of an oar or of the sea. He then must build a shrine and sacrifice before he can return home for good.<ref>Outline originally based on {{Citation | surname=Dalby | given=Andrew | authorlink=Andrew Dalby | title=] | publisher=Norton | place=New York, London | year=2006 | ISBN=0393057887 }} pp. xx-xxiv.</ref> | |||

| ], ''] and ]'']] | |||

| In the course of Odysseus's seven years as a captive of Calypso on the island ], she has fallen deeply in love with him, even though he spurns her offers of immortality as her husband and still mourns for home. She is ordered to release him by the messenger god ], who has been sent by Zeus in response to Athena's plea. Odysseus builds a raft and is given clothing, food, and drink by Calypso. When Poseidon learns that Odysseus has escaped, he wrecks the raft, but helped by a veil given by the sea nymph ], Odysseus swims ashore on ], the island of the Phaeacians. Naked and exhausted, he hides in a pile of leaves and falls asleep. | |||

| The next morning, awakened by girls' laughter, he sees the young ], who has gone to the seashore with her maids after Athena told her in a dream to do so. He appeals for help. She encourages him to seek the hospitality of her parents, ] and ]. Alcinous promises to provide him a ship to return him home without knowing the identity of Odysseus. He remains for several days. Odysseus asks the blind singer ] to tell the story of the ], a stratagem in which Odysseus had played a leading role. Unable to hide his emotion as he relives this episode, Odysseus at last reveals his identity. He then tells the story of his return from Troy. | |||

| ==Character of Odysseus== | |||

| {{Main|Odysseus}} | |||

| ===Odysseus's account of his adventures (Books 9–12)=== | |||

| Odysseus' heroic trait is his ''mētis'', or "cunning intelligence"; he is often described as the "Peer of ] in Counsel." This intelligence is most often manifested by his use of disguise and deceptive speech. His disguises take forms both physical (altering his appearance) and verbal, such as telling the ] ] that his name is ], "Nobody", then escaping after blinding Polyphemus. When asked by other Cyclopes why he is screaming, Polyphemus replies that "Nobody" is hurting him, so the others assume that, "If alone as you are none uses violence on you, why, there is no avoiding the sickness sent by great Zeus; so you had better pray to your father, the lord Poseidon".<ref>From the Odyssey of Homer translated by ] .</ref> The most evident flaw that Odysseus sports is that of his arrogance and his pride, or ]. As he sails away from the island of the Cyclopēs, he shouts his name and boasts that no one can defeat the "Great Odysseus". The Cyclops then throws the top half of a mountain at him and prays to his father, Poseidon, saying that Odysseus has blinded him. This enrages Poseidon, causing the god to thwart Odysseus' homecoming for a very long time. | |||

| ]' Song'', by ], 1813–15]] | |||

| Odysseus recounts his story to the Phaeacians. After a failed raid against the ], Odysseus and his twelve ships were driven off course by storms. Odysseus visited the ] who gave his men their fruit which caused them to forget their homecoming. Odysseus had to drag them back to the ship by force. | |||

| Afterward, Odysseus and his men landed on a lush, uninhabited island near the land of the ]. The men entered the cave of ], where they found all the cheeses and meat they desired. Upon returning to his cave, Polyphemus sealed the entrance with a massive boulder and proceeded to eat Odysseus's men. Odysseus devised an escape plan in which he, identifying himself as "Nobody", plied Polyphemus with wine and blinded him with a wooden stake. When Polyphemus cried out, his neighbors left after Polyphemus claimed that "Nobody" had attacked him. Odysseus and his men finally escaped the cave by hiding on the underbellies of the sheep as they were let out of the cave. | |||

| As they escaped, however, Odysseus taunted Polyphemus and revealed himself. The Cyclops prayed to his father Poseidon, asking him to curse Odysseus to wander for ten years. After the escape, ] gave Odysseus a leather bag containing all the winds except the west wind, a gift that should have ensured a safe return home. Just as Ithaca came into sight, the sailors opened the bag while Odysseus slept, thinking it contained gold. The winds flew out, and the storm drove the ships back the way they had come. Aeolus, recognizing that Odysseus had drawn the ire of the gods, refused to further assist him. | |||

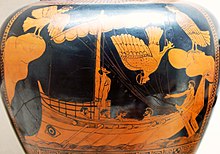

| After the cannibalistic ] destroyed all of his ships except his own, Odysseus sailed on and reached the island of ], home of witch-goddess ]. She turned half of his men into swine with drugged cheese and wine. Hermes warned Odysseus about Circe and gave Odysseus an herb called ], making him resistant to Circe's magic. Odysseus forced Circe to change his men back to their human forms and was seduced by her. They remained with her for one year. Finally, guided by Circe's instructions, Odysseus and his crew crossed the ocean and reached a harbor at the western edge of the world, where Odysseus ]. Odysseus summoned the spirit of the prophet ] and was told that he may return home if he is able to stay himself and his crew from eating the sacred ] on the island of Thrinacia and that failure to do so would result in the loss of his ship and his entire crew. He then meets his dead mother ] and first learns of the suitors and what happened in Ithaca in his absence. Odysseus also converses with his dead comrades from Troy.], {{Circa|480–470 BC}} (])]] | |||

| Returning to Aeaea, they buried Elpenor and were advised by Circe on the remaining stages of the journey. They skirted the land of the ]. All of the sailors had their ears plugged up with beeswax, except for Odysseus, who was tied to the mast as he wanted to hear the song. He told his sailors not to untie him as it would only make him drown himself. They then passed between the six-headed monster ] and the whirlpool ]. Scylla claimed six of his men. | |||

| Next, they landed on the island of Thrinacia, with the crew overriding Odysseus's wishes to remain away from the island. Zeus caused a storm that prevented them from leaving, causing them to deplete the food given to them by Circe. While Odysseus was away praying, his men ignored the warnings of Tiresias and Circe and hunted the sacred cattle. ] insisted that Zeus punish the men for this sacrilege. They suffered a shipwreck, and all but Odysseus drowned as he clung to a fig tree. Washed ashore on ], he remained there as Calypso's lover. | |||

| ===Return to Ithaca (Books 13–20)=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Having listened to his story, the Phaeacians agree to provide Odysseus with more treasure than he would have received from the spoils of Troy. They deliver him at night, while he is fast asleep, to a hidden harbour on Ithaca. Odysseus awakens and believes that he has been dropped on a distant land before Athena appears to him and reveals that he is indeed on Ithaca. She hides his treasure in a nearby cave and disguises him as an elderly beggar so he can see how things stand in his household. He finds his way to the hut of one of his own slaves, swineherd ], who treats him hospitably and speaks favorably of Odysseus. After dinner, the disguised Odysseus tells the farm laborers a fictitious tale of himself. | |||

| Telemachus sails home from Sparta, evading an ambush set by the suitors. He disembarks on the coast of Ithaca and meets Odysseus. Odysseus identifies himself to Telemachus (but not to Eumaeus), and they decide that the suitors must be killed. Telemachus goes home first. Accompanied by Eumaeus, Odysseus returns to his own house, still pretending to be a beggar, where he is only recognized by his faithful dog, ]. He is ridiculed by the suitors in his own home, especially ]. Odysseus meets Penelope and tests her intentions by saying he once met Odysseus in Crete. Closely questioned, he adds that he had recently been in ] and had learned something there of Odysseus's recent wanderings. | |||

| Odysseus's identity is discovered by the housekeeper ] when she recognizes an old scar as she is washing his feet. Eurycleia tries to tell Penelope about the beggar's true identity, but Athena makes sure that Penelope cannot hear her. Odysseus swears Eurycleia to secrecy. | |||

| ===Slaying of the suitors (Books 21–24)=== | |||

| ] (1812)|alt=]] | |||

| The next day, at Athena's prompting, Penelope maneuvers the suitors into competing for her hand with an archery competition using Odysseus's bow. The man who can string the bow and shoot an arrow through a dozen axe heads would win. Odysseus takes part in the competition, and he alone is strong enough to string the bow and shoot the arrow through the dozen axe heads, making him the winner. He then throws off his rags and kills Antinous with his next arrow. Odysseus kills the other suitors, first using the rest of the arrows and then, along with Telemachus, Eumaeus, and the cowherd Philoetius, with swords and spears. Once the battle is won, Telemachus also hangs twelve of their household maids whom Eurycleia identifies as guilty of betraying Penelope or having sex with the suitors. Odysseus identifies himself to Penelope. She is hesitant but recognizes him when he mentions that he made their bed from an olive tree still rooted to the ground. She embraces him and they sleep. | |||

| The next day, Odysseus goes to his father ]'s farm and reveals himself. Following them to the farm is a group of Ithacans, led by ], father of Antinous, who are out for revenge for the murder of the suitors. A battle breaks out, but it is quickly stopped by Athena and Zeus. | |||

| ==Structure== | ==Structure== | ||

| The ''Odyssey'' |

The ''Odyssey'' is 12,109 lines composed in ], also called Homeric hexameter.{{sfn|Myrsiades|2019|p=3}}{{sfn|Haslam|1976|p=203}} It opens '']'', in the middle of the overall story, with prior events described through ] and storytelling.{{sfn|Foley|2007|p=19}} The 24 books correspond to the letters of the ]; the division was likely made after the poem's composition, by someone other than Homer, but is generally accepted.{{sfn|Lattimore|1951|p=14}} | ||

| In the ], some of the books (individually and in groups) were commonly given their own titles: | |||

| In the first episodes, we trace ]' efforts to assert control of the household, and then, at Athena’s advice, to search for news of his long-lost father. Then the scene shifts: Odysseus has been a captive of the beautiful nymph ], with whom he has spent seven of his ten lost years. Released by the intercession of his patroness ], through the aid of Hermes, he departs, but his raft is destroyed by his divine enemy ], who is angry because ] blinded his son, ]. When Odysseus washes up on ], home to the ], he is assisted by the young ] and is treated hospitably. In return, he satisfies the Phaeacians' curiosity, telling them, and the reader, of all his adventures since departing from Troy. The shipbuilding Phaeacians then loan him a ship to return to ], where he is aided by the swineherd ], meets ], regains his household, kills the suitors, and is reunited with his faithful wife, ]. | |||

| *'''Books 1–4''': '']''—the story focuses on the perspective of Telemachus.{{sfn|Willcock|2007|p=32}} | |||

| Nearly all modern editions and translations of the ''Odyssey'' are divided into 24 books. This division is convenient but not original; it was developed by ] editors of the 3rd century BC. In the ], moreover, several of the books (individually and in groups) were given their own titles: the first four books, focusing on Telemachus, are commonly known as the '']''; Odysseus' narrative, Book 9, featuring his encounter with the cyclops Polyphemus, is traditionally called the '']''; and Book 11, the section describing his meeting with the spirits of the dead is known as the '']''. Books 9 through 12, wherein Odysseus recalls his adventures for his Phaeacian hosts, are collectively referred to as the '']'': Odysseus' "stories". | |||

| *'''Books 9–12''': ''Apologoi''—Odysseus recalls his adventures for his Phaeacian hosts.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Most |first=Glenn W. |date=1989 |title=The Structure and Function of Odysseus' Apologoi |journal=Transactions of the American Philological Association |volume=119 |pages=15–30 |doi=10.2307/284257 |jstor=284257 |issn=0360-5949}}</ref> | |||

| Book 22, wherein Odysseus kills all the suitors, has been given the title '']'': "slaughter of the suitors". | |||

| *'''Book 22''': ''Mnesterophonia'' ('slaughter of the suitors'; {{Langx|grc|Mnesteres|italic=yes|label=none|lit=suitors}} + {{Langx|grc|{{wikt-lang|en|φόνος|phónos}}|italic=yes|label=none|lit=slaughter}}).{{sfn|Cairns|2014|p=231}} | |||

| The last 548 lines of the ''Odyssey'', corresponding to Book 24, are believed by many scholars to have been added by a slightly later poet. |

Book 22 concludes the Greek ], though fragments remain of the "alternative ending" of sorts known as the '']''. The ''Telegony'' aside, the last 548 lines of the ''Odyssey'', corresponding to Book 24, are believed by many scholars to have been added by a slightly later poet.{{sfn|Carne-Ross|1998|p=ixi}} | ||

| ==Geography |

==Geography== | ||

| {{Main|Homer's Ithaca|Geography of the Odyssey}} | {{Main|Homer's Ithaca|Geography of the Odyssey}} | ||

| The events in the main sequence of the ''Odyssey'' (excluding Odysseus's ] of his wanderings) have been said to take place in the ] and in what are now called the ].<ref name="auto">], '']'', 1.2.15, cited in {{harvnb|Finley|1976|p=33}}</ref> There are difficulties in the apparently simple identification of Ithaca, the homeland of Odysseus, which may or may not be the same island that is now called {{Langx|grc|Ithakē|label=none|italic=yes}} (modern Greek: {{Langx|grc|Ιθάκη|label=none}}).<ref name="auto"/> The wanderings of Odysseus as told to the Phaeacians, and the location of the Phaeacians' own island of Scheria, pose more fundamental problems, if geography is to be applied: scholars, both ancient and modern, are divided as to whether any of the places visited by Odysseus (after ] and before his return to Ithaca) are real.{{sfn|Fox|2008}} Both antiquated and contemporary scholars have attempted to map Odysseus's journey but now largely agree that the landscapes, especially of the Apologia (Books 9 to 11), include too many mythic aspects as features to be unequivocally mappable.<ref name="Zazzera">{{Cite web |last=Zazzera |first=Elizabeth Della |date=27 February 2019 |title=The Geography of the Odyssey |website=Lapham's Quarterly |access-date=29 July 2022 |url=https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/geography-odyssey |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201008231344/https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/geography-odyssey |archive-date=8 October 2020 }}</ref> Classicist ] created an interactive map which plots Odysseus's travels,<ref>{{Cite web |last=Struck |first=Peter T. |author-link=Peter Struck (classicist) |title=Map of Odysseus' Journey |website=classics.upenn.edu |access-date=29 July 2022 |url=http://www.classics.upenn.edu/myth/php/homer/index.php?page=odymap |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200318120501/http://www.classics.upenn.edu/myth/php/homer/index.php?page=odymap |archive-date=18 March 2020 }}</ref> including his near homecoming which was thwarted by the bag of wind.<ref name="Zazzera" /> | |||

| ==Influences== | |||

| Events in the main sequence of the ''Odyssey'' (excluding Odysseus' embedded narrative of his wanderings) take place in the ] and in what are now called the ]. There are difficulties in the apparently simple identification of ], the homeland of Odysseus, which may or may not be the same island that is now called Ithake. The wanderings of Odysseus as told to the Phaeacians, and the location of the Phaeacians' own island of ], pose more fundamental problems, if geography is to be applied: scholars both ancient and modern are divided as to whether or not any of the places visited by Odysseus (after ] and before his return to ]) are real. | |||

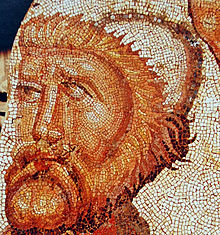

| ], believed to be a possible inspiration for the figure of Polyphemus]] | |||

| Scholars have seen strong influences from Near Eastern mythology and literature in the ''Odyssey''.{{sfn|West|1997|p=403}} ] notes substantial parallels between the '']'' and the ''Odyssey''.{{sfn|West|1997|pp=402–417}} Both Odysseus and ] are known for traveling to the ends of the earth and on their journeys go to the land of the dead.{{sfn|West|1997|p=405}} On his voyage to the underworld, Odysseus follows instructions given to him by Circe, who is located at the edges of the world and is associated through imagery with the sun.{{sfn|West|1997|p=406}} Like Odysseus, Gilgamesh gets directions on how to reach the land of the dead from a divine helper: the goddess ], who, like Circe, dwells by the sea at the ends of the earth, whose home is also associated with the sun. Gilgamesh reaches Siduri's house by passing through a tunnel underneath Mt. ], the high mountain from which the sun comes into the sky.{{sfn|West|1997|p=410}} West argues that the similarity of Odysseus' and Gilgamesh's journeys to the edges of the earth are the result of the influence of the Gilgamesh epic upon the ''Odyssey''.{{sfn|West|1997|p=417}} | |||

| ==Dating the ''Odyssey''== | |||

| In 2008, scientists ] and Constantino Baikouzis at ] used clues in the text and astronomical data to attempt to pinpoint the time of Odysseus's return from his journey after the Trojan War.<ref>{{citation | |||

| |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/0803317105v1 | |||

| |title=Is an eclipse described in the Odyssey? | |||

| |first1=Constantino | |||

| |last1= Baikouzis | |||

| |first2=Marcelo O. | |||

| |last2= Magnasco | |||

| |publisher=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | |||

| |date=June 24, 2008 | |||

| |doi=10.1073/pnas.0803317105 | |||

| |accessdate=2008-06-27 | |||

| |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | |||

| |volume=105 | |||

| |pages=8823 | |||

| }}.</ref> | |||

| In 1914, ] ] surmised the origins of the Cyclops to be the result of ancient Greeks finding an elephant skull.{{sfn|Mayor|2000|p={{page needed|date=July 2022}}}} The enormous nasal passage in the middle of the forehead could have looked like the eye socket of a giant, to those who had never seen a living elephant.{{sfn|Mayor|2000|p={{page needed|date=July 2022}}}} Classical scholars, on the other hand, have long known that the story of the Cyclops was originally a ], which existed independently of the ''Odyssey'' and which became part of it at a later date. Similar stories are found in cultures across Europe and the Middle East.{{sfn|Anderson|2000|pp=127–131}} According to this explanation, the Cyclops was originally simply a giant or ogre, much like ] in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''.{{sfn|Anderson|2000|pp=127–131}} Graham Anderson suggests that the addition about it having only one eye was invented to explain how the creature was so easily blinded.{{sfn|Anderson|2000|pp=124–125}} | |||

| The first clue is Odysseus's sighting of ] just before dawn as he arrives on Ithaca. The second is a new moon on the night before the massacre of the suitors. The final clue is a total ], falling over Ithaca around noon, when Penelope's suitors sit down for their noon meal. The seer ] approaches the suitors and foretells their death, saying, "The Sun has been obliterated from the sky, and an unlucky darkness invades the world." The problem with this is that the 'eclipse' is only seen by Theoclymenus, and the suitors toss him out, calling him mad. No-one else sees the sky darken, and it is therefore not actually described as an eclipse within the story, merely a vision by Theoclymenus. | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| Doctors Baikouzis and Magnasco state that "he odds that purely fictional references to these phenomena (so hard to satisfy simultaneously) would coincide by accident with the only eclipse of the century are minute." They conclude that these three astronomical references "'cohere,' in the sense that the astronomical phenomena pinpoint the date of 16 April 1178 BC" as the most likely date of Odysseus' return. | |||

| == Themes and patterns == | |||

| This dating places the destruction of Troy, ten years before, to 1188 BC, which is close to the archaeologically dated destruction of ] circa 1190 BC | |||

| === Homecoming === | |||

| ==Near Eastern influences== | |||

| ] | |||

| Scholars have seen strong influences from Near Eastern mythology and literature in the ''Odyssey''. ] has noted substantial parallels between the ] and the ''Odyssey''.<ref>] ''The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. (Oxford 1997) 402-417.</ref> Both Odysseus and ] are known for traveling to the ends of the earth, and on their journeys go to the land of the dead. On his voyage to the underworld, Odysseus follows instructions given to him by ], a goddess who is the daughter of the sun-god ]. Her island, ], is located at the edges of the world, and seems to have close associations with the sun. Like Odysseus, ] gets directions on how to reach the land of the dead from a divine helper: in this case, she is the goddess ], who, like Circe, dwells by the sea at the ends of the earth. Her home is also associated with the sun: Gilgamesh reaches Siduri's house by passing through a tunnel underneath Mt. ], the high mountain from which the sun comes into the sky. West argues that the similarity of Odysseus' and Gilgamesh's journeys to the edges of the earth are the result of the influence of the Gilgamesh epic upon the ''Odyssey''. | |||

| Homecoming (Ancient Greek: ''νόστος, nostos'') is a central theme of the ''Odyssey''.{{sfn|Bonifazi|2009|pp=481, 492}} Anna Bonafazi of the ] writes that, in Homer, '']'' is "return home from Troy, by sea".{{sfn|Bonifazi|2009|p=481}} Agatha Thornton examines ''nostos'' in the context of characters other than Odysseus, in order to provide an alternative for what might happen after the end of the ''Odyssey''.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=1–15}} For instance, one example is that of Agamemnon's homecoming versus Odysseus'. Upon Agamemnon's return, his wife Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus, kill Agamemnon. Agamemnon's son, ], out of vengeance for his father's death, kills Aegisthus. This parallel compares the death of the suitors to the death of Aegisthus and sets Orestes up as an example for Telemachus.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=1–15}} Also, because Odysseus knows about Clytemnestra's betrayal, Odysseus returns home in disguise in order to test the loyalty of his own wife, Penelope.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=1–15}} Later, Agamemnon praises Penelope for not killing Odysseus. It is because of Penelope that Odysseus has fame and a successful homecoming. This successful homecoming is unlike ], who has fame but is dead, and Agamemnon, who had an unsuccessful homecoming resulting in his death.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=1–15}} | |||

| The cyclop's origins have also been surmised to be the results of Ancient Greeks finding an elephant skull, by paleontologist ] in 1914. The enormous nasal passage in the middle of the forehead, could have looked like the eye socket of a giant, to those who had never seen a living elephant.<ref>Abel's surmise is noted by ], ''The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times'' (Princeton University Press) 2000.</ref> | |||

| == |

=== Wandering === | ||

| *The Athenian tyrant ], who ruled between 546 and 527 BC, is believed to have established a Commission of Editors of Homer to edit the text of the poems and remove any errors and interpolations, thus establishing a canonical text.<ref name="enotes"></ref> | |||

| *The earliest papyrus fragments date back to the third century BC.<ref name="enotes" /> | |||

| *The oldest complete manuscript is the Laurentianus from the 10th or 11th century.<ref name="enotes" /> | |||

| *The ] of both the Iliad and the Odyssey is by ] in ], most likely from 1488. | |||

| Only two of Odysseus's adventures are described by the narrator. The rest of Odysseus' adventures are recounted by Odysseus himself. The two scenes described by the narrator are Odysseus on Calypso's island and Odysseus' encounter with the Phaeacians. These scenes are told by the poet to represent an important transition in Odysseus' journey: being concealed to returning home.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=16–37}} | |||

| ==Cultural impact== | |||

| *'']'', written by ] of Samosata in the 2nd century AD, is a parody of the Odyssey describing a journey beyond the ] and to the moon. | |||

| *A modern novel inspired by the ''Odyssey'' is ]'s '']'' (1922). Every episode of Joyce's novel has an assigned theme, technique and correspondences between its characters and those of Homer's Odyssey. | |||

| *The first canto of ]'s '']'' is a retelling of Odysseus' journey to the underworld. | |||

| *''Merugud Uilix maicc Leirtis'' is an eccentric Old Irish version of the material; the work exists in a twelfth-century manuscript that linguists believe is based on an eighth-century original | |||

| *Some of the tales of ] from '']'' were taken from the ''Odyssey''. | |||

| *The 1954 ] ] by librettist ] and composer ] was freely adapted from the ] and the Odyssey, re-setting the action to the ] state of ] in the years after the ], with events inspired by the Iliad in Act One and events inspired by the Odyssey in Act Two. | |||

| *'']'', a made-for-TV movie from 1997 by Hallmark Entertainment and directed by ] is a slightly abbreviated version of the epic. It stars ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| *'']'' is an obvious homage to the work attributed to Homer. There are several elements in 2001 which are direct parallels to The Odyssey such as the hero's shipwreck, his nemesis, (upon whom the hero originally depended upon for sustenance), and the nemesis' single eye.{{Dubious|Use of nemesis|date=June 2009}} | |||

| *In ]'s film ''] (Contempt)'' (1963) German film director ] plays himself trying to direct a film adaptation. | |||

| *The ] film '']'' was loosely based on Homer's poem. | |||

| *American ] band ] made a musical interpretation of the Odyssey in the album ''The Odyssey''. | |||

| *'']'', a ] novel written by ] follows the path of the classic ''Odyssey'', as a ] from the ] of ] struggles to return home to his ]. | |||

| *The Japanese-French anime '']'' updates the classic world setting into a 31st century space opera. | |||

| *Zachary Mason, ''The Lost Books of the Odyssey: A Novel'' (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010): a series interlocking short stories and vignettes, some shorter than a page, that rework and explode Homer's original plot in a contemporary style reminiscent of ]. | |||

| Calypso's name comes from the Greek word {{Langx|grc|kalúptō|italic=yes|label=none}} ({{Langx|grc|{{wikt-lang|en|καλύπτω}}|label=none}}), meaning 'to cover' or 'conceal', which is apt, as this is exactly what she does with Odysseus.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2010 |title=Greek Myths & Greek Mythology |website=greekmyths-greekmythology.com |access-date=5 May 2020 |url=http://www.greekmyths-greekmythology.com/calypso-odysseus-greek-myth/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160502235701/http://www.greekmyths-greekmythology.com/calypso-odysseus-greek-myth |archive-date=2 May 2016 }}</ref> Calypso keeps Odysseus concealed from the world and unable to return home. After leaving Calypso's island, the poet describes Odysseus' encounters with the Phaeacians—those who "convoy without hurt to all men"{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=8.566}}—which represents his transition from not returning home to returning home.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=16–37}} | |||

| ==Notable English translations== | |||

| {{wiktionary}} | |||

| {{wikisourcepar|The Odyssey}} | |||

| {{wikisourcepar|el:Οδύσσεια|ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑ}} | |||

| {{commonscat|Odyssey}} | |||

| This is a partial list of translations into English of Homer's Odyssey. For a more complete list see ]. | |||

| *], 1616 (couplets) | |||

| *], 1713 (couplets); ] edition; | |||

| *], 1791 (blank verse) | |||

| *Samuel Henry Butcher and ], Project Gutenberg edition; | |||

| *], 1871 (blank verse) | |||

| *] 1876 (blank verse) | |||

| *], 1887 | |||

| *], 1898 (prose), Project Gutenberg edition; | |||

| *], 1918 (prose), | |||

| *A. T. Murray (revised by George E. Dimock), 1919; ] (ISBN 0-674-99561-9) | |||

| *], 1921, prose. An audio CD recording read by Norman Deitz is available (ISBN 1-4025-2325-4), 1989. | |||

| *T. E. Shaw (]), 1932 | |||

| *], 1937, prose | |||

| *], 1945, prose | |||

| *], 1963 (ISBN 0-679-72813-9) | |||

| *], 1965 (ISBN 0-06-093195-7) | |||

| *Albert Cook, 1967 (Norton Critical Edition) | |||

| *Walter Shewring, 1980 (ISBN 0-19-283375-8), ] (Oxford World's Classics), prose | |||

| *Allen Mandelbaum, 1990 | |||

| *], 1996 (ISBN 0-14-026886-3); an unabridged audio recording by ] is also available (ISBN 0-14-086430-X). | |||

| *], ], 2000 (ISBN 0-87220-484-7). An audio CD recording read by the translator is also available (ISBN 1-930972-06-7). | |||

| *Martin Hammond, 2000, prose | |||

| *Edward McCrorie, 2004 (ISBN 0-8018-8267-2), ]. | |||

| *{{perseus|Hom.|Od.|1.1}} | |||

| ==Significant Themes in the Odyssey== | |||

| {{unreferenced section}} | |||

| There is a strong theme of homecoming (''nostos'') in the Odyssey, because Odysseus is on a journey home after the Trojan war has finally ended. | |||

| Also, during Odysseus' journey, he encounters many beings that are close to the gods. These encounters are useful in understanding that Odysseus is in a world beyond man and that influences the fact he cannot return home.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=16–37}} These beings that are close to the gods include the Phaeacians who lived near the Cyclopes,{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=6.4–5}} whose king, Alcinous, is the great-grandson of the king of the giants, ], and the grandson of Poseidon.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=16–37}} Some of the other characters that Odysseus encounters are the cyclops ], the son of Poseidon; Circe, a sorceress who turns men into animals; and the ] giants, the Laestrygonians.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=16–37}} | |||

| The theme of temptation as a psychological peril is portrayed by the sirens who lure sailors to their deaths by seduction. They represent the ideal audience—they sing about the most glorious moment of your life, thus tempting you to stay the hero or warrior they are portraying you as. Your own weakness makes you vulnerable, your greatest weakness comes from inside you. | |||

| === Guest-friendship === | |||

| Another significant theme in the Odyssey is one of disguise, in the case of the gods, they disguise themselves so that they can interact with mortals. Athena in particular assumes many disguises including a shepherd, a girl, Telemachus, and the Mentor. Odysseus is also able to disguise his identity, though not physically by telling Polyphemus his name is ‘Nobody’ so that he will not be identified as the one who blinded the Cyclops. | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Throughout the course of the epic, Odysseus encounters several examples of {{translit|grc|]}} ('guest-friendship'), which provide models of how hosts should and should not act.{{sfn|Reece|1993|p={{page needed|date=July 2022}}}}{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=38–46}} The Phaeacians demonstrate exemplary guest-friendship by feeding Odysseus, giving him a place to sleep, and granting him many gifts and a safe voyage home, which are all things a good host should do. Polyphemus demonstrates poor guest-friendship. His only "gift" to Odysseus is that he will eat him last.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=38–46}} Calypso also exemplifies poor guest-friendship because she does not allow Odysseus to leave her island.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=38–46}} Another important factor to guest-friendship is that kingship implies generosity. It is assumed that a king has the means to be a generous host and is more generous with his own property.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=38–46}} This is best seen when Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, begs Antinous, one of the suitors, for food and Antinous denies his request. Odysseus essentially says that while Antinous may look like a king, he is far from a king since he is not generous.{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=17.415–444}} | |||

| Hospitality (''xenia'') is also a reoccurring theme as fundamental as the heroic code in the Odyssey. During that time, beggars or travelers often knocked on a stranger’s door in hopes of a procuring a place to stay. There are specific steps for proper hospitality beginning with the feeding of the guest, which is of utmost importance since food is rare at that time and beggars beg for food, not money. Before the food is given, a bath is offered to the stranger, done by a woman or a servant—often different depending on the status of the visitor. After the food is given, the beggar is asked who he is and where he is from and stories are exchanged. Next, they are offered a bed to sleep on and it is understood that that they can stay overnight and at the most another night. When the beggar is leaving, there is an exchange of gifts, if the beggar does not have a gift to give, they will still be given one. | |||

| According to J. B. Hainsworth, guest-friendship follows a very specific pattern:{{sfn|Hainsworth|1972|pp=320–321}} | |||

| # The arrival and the reception of the guest. | |||

| # Bathing or providing fresh clothes to the guest. | |||

| # Providing food and drink to the guest. | |||

| # Questions may be asked of the guest and entertainment should be provided by the host. | |||

| # The guest should be given a place to sleep, and both the guest and host retire for the night. | |||

| # The guest and host exchange gifts, the guest is granted a safe journey home, and the guest departs. | |||

| Another important factor of guest-friendship is not keeping the guest longer than they wish and also promising their safety while they are a guest within the host's home.{{sfn|Reece|1993|p={{page needed|date=July 2022}}}}{{sfn|Edwards|1992|pp=284–330}} | |||

| === Testing === | |||

| ] | |||

| Another theme throughout the ''Odyssey'' is testing.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=47–51}} This occurs in two distinct ways. Odysseus tests the loyalty of others and others test Odysseus' identity. An example of Odysseus testing the loyalties of others is when he returns home.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=47–51}} Instead of immediately revealing his identity, he arrives disguised as a beggar and then proceeds to determine who in his house has remained loyal to him and who has helped the suitors. After Odysseus reveals his true identity, the characters test Odysseus' identity to see if he really is who he says he is.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=47–51}} For instance, Penelope tests Odysseus' identity by saying that she will move the bed into the other room for him. This is a difficult task since it is made out of a living tree that would require being cut down, a fact that only the real Odysseus would know, thus proving his identity.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=47–51}} | |||

| Testing also has a very specific ] that accompanies it. Throughout the epic, the testing of others follows a typical pattern. This pattern is:{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=47–51}}{{sfn|Edwards|1992|pp=284–330}} | |||

| # Odysseus is hesitant to question the loyalties of others. | |||

| # Odysseus tests the loyalties of others by questioning them. | |||

| # The characters reply to Odysseus' questions. | |||

| # Odysseus proceeds to reveal his identity. | |||

| # The characters test Odysseus' identity. | |||

| # There is a rise of emotions associated with Odysseus' recognition, usually lament or joy. | |||

| # Finally, the reconciled characters work together. | |||

| === Omens === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Omens occur frequently throughout the ''Odyssey''. Within the epic poem, they frequently involve birds.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=52–57}} According to Thornton, most crucial is who receives each omen and in what way it manifests. For instance, bird omens are shown to Telemachus, Penelope, Odysseus, and the suitors.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=52–57}} Telemachus and Penelope receive their omens as well in the form of words, sneezes, and dreams.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=52–57}} However, Odysseus is the only character who receives thunder or lightning as an omen.{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=20.103–104}}{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=21.414}} She highlights this as crucial because lightning, as a symbol of Zeus, represents the kingship of Odysseus.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=52–57}} Odysseus is associated with Zeus throughout both the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey.''{{sfn|Kundmueller|2013|p=7}} | |||

| Omens are another example of a type scene in the ''Odyssey.'' Two important parts of an omen type scene are the ''recognition'' of the omen, followed by its ''interpretation''.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=52–57}} In the ''Odyssey'', all of the bird omens—with the exception of the first—show large birds attacking smaller birds.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=52–57}}{{sfn|Edwards|1992|pp=284–330}} Accompanying each omen is a wish which can be either explicitly stated or only implied.{{sfn|Thornton|1970|pp=52–57}} For example, Telemachus wishes for vengeance{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=2.143–145}} and for Odysseus to be home,{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=15.155–159}} Penelope wishes for Odysseus' return,{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=19.136}} and the suitors wish for the death of Telemachus.{{sfn|Homer|1975|loc=20.240–243}} | |||

| ==Textual history== | |||

| === Composition === | |||

| There is no scholarly consensus on the date of the composition of the ''Odyssey''. The Greeks began adopting a modified version of the ] to write down their own language during the mid-8th century BC.{{sfn|Wilson|2018|p=21}} The Homeric poems may have been one of the earliest products of that literacy, and if so, would have been composed some time in the late 8th century BC.{{sfn|Wilson|2018|p=23}} Inscribed on a ] found in ], Italy, are the words "Nestor's cup, good to drink from".<ref>{{Cite news |last=Higgins |first=Charlotte |author-link=Charlotte Higgins |date=13 November 2019 |title=From Carnage to a Camp Beauty Contest: The Endless Allure of Troy |work=] |url=http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2019/nov/13/carnage-camp-beauty-contest-endless-allure-troy-british-museum |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200109174814/https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2019/nov/13/carnage-camp-beauty-contest-endless-allure-troy-british-museum |archive-date=9 January 2020 }}</ref> Some scholars, such as ], have tied this cup to a description of King ] in the ''Iliad.''{{sfn|Watkins|1976|p=28}} If the cup is an allusion to the ''Iliad'', that poem's composition can be dated to at least 700–750 BC.{{sfn|Wilson|2018|p=21}} | |||

| Dating is similarly complicated by the fact that the Homeric poems, or sections of them, were performed regularly by rhapsodes for several hundred years.{{sfn|Wilson|2018|p=21}} The ''Odyssey'' as it exists today is likely not significantly different.{{sfn|Wilson|2018|p=23}} Aside from minor differences, the Homeric poems gained a canonical place in the institutions of ancient Athens by the 6th century.{{sfn|Davison|1955|pp=7–8}} In 566 BC, ] instituted a civic and religious festival called the ], which featured performances of Homeric poems.{{sfn|Davison|1955|pp=9–10}} These are significant because a "correct" version of the poems had to be performed, indicating that a particular version of the text had become canonised.{{sfn|Wilson|2018|loc=p. 21, "In 566 BCE, Pisistratus, the tyrant of the city (which was not yet a democracy), instituted a civic and religious festival, the Panathenaia, which included a poetic competition, featuring performances of the Homeric poems. The institution is particularly significant because we are told that the Homeric poems had to be performed "correctly", which implies the canonization of a particular written text of The Iliad and The Odyssey at this date."}} | |||

| === Textual tradition === | |||

| ] of the Greek Renaissance scholar ], who produced the first printed edition of the ''Odyssey'' in 1488]] | |||

| The ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'' were widely copied and used as ] in lands where the Greek language was spoken throughout antiquity.{{sfn|Lamberton|2010|pp=449–452}}{{sfn|Browning|1992|pp=134–148}} Scholars may have begun to write commentaries on the poems as early as the time of ] in the 4th century BC.{{sfn|Lamberton|2010|pp=449–452}} In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, scholars affiliated with the ]—particularly ] and ]—edited the Homeric poems, wrote commentaries on them, and helped establish the canonical texts.<ref name="Haslam2012">{{Cite book |last=Haslam |first=Michael |title=The Homer Encyclopedia |date=2012 |isbn=978-1-4051-7768-9 |chapter=Text and Transmission |doi=10.1002/9781444350302.wbhe1413}}</ref> | |||

| The ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'' remained widely studied and used as school texts in the ] during the ].{{sfn|Lamberton|2010|pp=449–452}}{{sfn|Browning|1992|pp=134–148}} The Byzantine Greek scholar and archbishop ] ({{Circa|1115|1195/6 AD}}) wrote exhaustive commentaries on both of the Homeric epics that became seen by later generations as authoritative;{{sfn|Lamberton|2010|pp=449–452}}{{sfn|Browning|1992|pp=134–148}} his commentary on the ''Odyssey'' alone spans nearly 2,000 oversized pages in a twentieth-century edition.{{sfn|Lamberton|2010|pp=449–452}} The first printed edition of the ''Odyssey'', known as the '']'', was ] by the Greek scholar ], who had been born in Athens and had studied in Constantinople.{{sfn|Lamberton|2010|pp=449–452}}{{sfn|Browning|1992|pp=134–148}} His edition was printed in ] by a Greek printer named Antonios Damilas.{{sfn|Browning|1992|pp=134–148}} | |||

| Since the late 19th century, many papyri containing fragments of the ''Odyssey'' have been found in Egypt, some with content different from later medieval versions.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Daley |first=Jason |date=11 July 2018 |title=Oldest Greek Fragment of Homer Discovered on Clay Tablet |work=] |access-date=29 July 2022 |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/oldest-greek-fragment-homer-discovered-clay-tablet-180969602/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190123223253/https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/oldest-greek-fragment-homer-discovered-clay-tablet-180969602/ |archive-date=23 January 2019 }}</ref> | |||

| In 2018, the ] revealed the discovery of a clay tablet near the ] at Olympia, containing 13 verses from the ''Odyssey''{{'s}} 14th book. While it was initially reported to date from the 3rd century AD, the date is unconfirmed.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Tagaris |first=Karolina |editor-last=Heavens |editor-first=Andrew |date=10 July 2018 |title='Oldest known extract' of Homer's Odyssey discovered in Greece |work=] |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-greece-archaeology-odyssey/oldest-known-extract-of-homers-odyssey-discovered-in-greece-idUSKBN1K01QM |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190324125157/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-greece-archaeology-odyssey/oldest-known-extract-of-homers-odyssey-discovered-in-greece-idUSKBN1K01QM |archive-date=24 March 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=10 July 2018 |title=Homer Odyssey: Oldest extract discovered on clay tablet |publisher=] |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-44779492 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200901203416/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-44779492 |archive-date=1 September 2020}}</ref> | |||

| === English translations === | |||

| {{See also|English translations of Homer}} | |||

| ]'s English translations of the ''Odyssey'' and the ''Iliad'', published together in 1616 but serialised earlier, were the first to enjoy widespread success. The texts had been published in translation before, with some translated not from the original Greek.{{Sfn|Fay|1952|p=104}}<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Myrsiades |first1=Kostas |last2=Pinsker |first2=Sanford |date=1976 |title=A Bibliographical Guide to Teaching the Homeric Epics in College Courses |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25111144 |journal=College Literature |volume=3 |issue=3 |pages=237–259 |jstor=25111144 |issn=0093-3139 |access-date=31 December 2022 |archive-date=31 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221231005736/https://www.jstor.org/stable/25111144 |url-status=live }}</ref> Chapman worked on these for a large part of his life.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Brammall |first=Sheldon |date=2018-07-01 |title=George Chapman: Homer's Iliad, edited by Robert S. Miola; Homer's Odyssey, edited by Gordon Kendal |url=https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/tal.2018.0339 |journal=Translation and Literature |volume=27 |issue=2 |pages=223–231 |doi=10.3366/tal.2018.0339 |s2cid=165293864 |issn=0968-1361 |access-date=31 December 2022 |archive-date=31 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221231123237/https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/tal.2018.0339 |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1581, Arthur Hall translated the first 10 books of the ''Iliad'' from a French version.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Marlborough.) |first=George Spencer Churchill (Duke of |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZIO3q3xx7n8C&dq=Arthur+Hall+odyssey&pg=RA3-PA11 |title=Bibliotheca Blandfordiensis. 9 Fasc. (Catalogus Librorum Qui Bibliothecae Blandfordiensis Nuper Additi Sunt. 1814.). |pages=11 |date=1814 |language=en |access-date=30 January 2023 |archive-date=13 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230813013148/https://books.google.com/books?id=ZIO3q3xx7n8C&dq=Arthur+Hall+odyssey&pg=RA3-PA11 |url-status=live }}</ref> Chapman's translations persisted in popularity, and are often remembered today through ]' sonnet "]" (1816).<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Grafton |first1=Anthony |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LbqF8z2bq3sC |title=The Classical Tradition |last2=Most |first2=Glenn W. |last3=Settis |first3=Salvatore |date=2010-10-25 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-03572-0 |pages=331 |language=en}}</ref> Years after completing his translation of the ''Iliad'', ] began to translate the ''Odyssey'' because of his financial situation. His second translation was not received as favourably as the first.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Baines |first=Paul |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/48139753 |title=The Complete Critical Guide to Alexander Pope |publisher=Routledge |year=2000 |isbn=0-203-16993-X |location=London |pages=25 |oclc=48139753 |access-date=31 December 2022 |archive-date=24 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220524071911/http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/48139753 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ], a professor of ] at the ], notes that as late as the first decade of the 21st century, almost all of the most prominent translators of Greek and Roman literature had been men.<ref name="Wilson2017">{{Cite news |last=Wilson |first=Emily |date=7 July 2017 |title=Found in Translation: How Women are Making the Classics Their Own |work=] |url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jul/07/women-classics-translation-female-scholars-translators |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200729234906/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jul/07/women-classics-translation-female-scholars-translators |archive-date=29 July 2020 |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> She calls her experience of translating Homer one of "intimate alienation".<ref name="Wilson2017" /> Wilson writes that this has affected the popular conception of characters and events of the ''Odyssey,''{{sfn|Wilson|2018|p=86}} inflecting the story with connotations not present in the original text: "For instance, in the scene where Telemachus oversees the hanging of the slaves who have been sleeping with the suitors, most translations introduce derogatory language ('sluts' or 'whores'){{nbsp}}... The original Greek does not label these slaves with derogatory language."{{sfn|Wilson|2018|p=86}} In the original Greek, the word used is ''hai'', the feminine article, equivalent to "those female people".<ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Wilson |first=Emily |date=8 December 2017 |title=A Translator's Reckoning With the Women of The Odyssey |magazine=] |access-date=29 July 2022 |url=https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/a-translators-reckoning-with-the-women-of-the-odyssey |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200806144049/https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/a-translators-reckoning-with-the-women-of-the-odyssey |archive-date=6 August 2020 }}</ref> | |||

| == Legacy == | |||

| {{see also|Category:Works based on the Odyssey|label1=Category:Works based on the ''Odyssey''}} | |||

| {{see also|Parallels between Virgil's Aeneid and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey|label1=Parallels between Virgil's ''Aeneid'' and Homer's ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey''}} | |||

| ]'s '']''|alt=]] | |||

| The influence of the Homeric texts can be difficult to summarise because of how greatly they have affected the popular imagination and cultural values.{{sfn|Kenner|1971|p=50}} The ''Odyssey'' and the ''Iliad'' formed the basis of education for members of ancient Mediterranean society. That curriculum was adopted by Western humanists,{{sfn|Hall|2008|p=25}} meaning the text was so much a part of the cultural fabric that it became irrelevant whether an individual had read it.{{sfn|Ruskin|1868|loc=p. 17, "All Greek gentlemen were educated under Homer. All Roman gentlemen, by Greek literature. All Italian, and French, and English gentlemen, by Roman literature, and by its principles."}} As such, the influence of the ''Odyssey'' has reverberated through over a millennium of writing. The poem topped a poll of experts by ''] Culture'' to find literature's most enduring narrative.<ref name=":6">{{Cite web |last=Haynes |first=Natalie |author-link=Natalie Haynes |date=22 May 2018 |title=The Greatest Tale Ever Told? |website=] |url=https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180521-the-greatest-tale-ever-told |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200619135051/https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180521-the-greatest-tale-ever-told |archive-date=19 June 2020 }}</ref> It is widely regarded by western literary critics as a timeless classic<ref>{{Cite web |last=Cartwright |first=Mark |date=15 March 2017 |title=Odyssey |publisher=] |url=http://www.worldhistory.org/Odyssey/ |access-date=29 July 2022 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170704162738/http://www.ancient.eu/Odyssey/ |archive-date=4 July 2017 }}</ref> and remains one of the oldest works of extant literature commonly read by Western audiences.<ref>{{Cite news |last=North |first=Anna |date=20 November 2017 |title=Historically, men translated the Odyssey. Here's what happened when a woman took the job |work=] |access-date=29 July 2022 |url=https://www.vox.com/identities/2017/11/20/16651634/odyssey-emily-wilson-translation-first-woman-english |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200627123124/https://www.vox.com/identities/2017/11/20/16651634/odyssey-emily-wilson-translation-first-woman-english |archive-date=27 June 2020 }}</ref> As an ], it is considered a distant forerunner of the ] genre, and, says ] ], "there are more science-fictional transfigurations of the ''Odyssey'' than of any other literary text".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Stableford |first=Brian |author-link=Brian Stableford |title=]: A Critical Guide to Science Fiction |date=2004 |publisher=Libraries unlimited |isbn=978-1-59158-171-0 |editor-last=Barron |editor-first=Neil |editor-link=Neil Barron |edition=5th |location=Westport, Connecticut |pages=5 |language=en |chapter=The Emergence of Science Fiction, 1516–1914 |orig-date=1976}}</ref> | |||

| === Literature === | |||

| In Canto XXVI of the '']'', ] meets Odysseus in the ], where Odysseus appends a new ending to the ''Odyssey'' in which he never returns to Ithaca and instead continues his restless adventuring.{{sfn|Mayor|2000|p={{page needed|date=July 2022}}}} ] suggests that Dante's depiction of Odysseus became understood as a manifestation of ] ] and ], with the cyclops standing in for "accounts of monstrous races on the edge of the world", and his defeat as symbolising "the Roman domination of the western Mediterranean".{{sfn|Reece|1993|p={{page needed|date=July 2022}}}} Some of Ulysses's adventures reappear in the Arabic tales of ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Sinbad the Sailor |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sindbad-the-Sailor |website=Encyclopedia Brittanica |access-date=12 November 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Burton |first1=Richard |title=The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night Volume VI |date=1885 |publisher=The Burton Club; Oxford |page=40 |url=https://ia801607.us.archive.org/34/items/arabiantranslat06burtuoft/arabiantranslat06burtuoft.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| The Irish writer ]'s ] novel ] (1922) was significantly influenced by the ''Odyssey''. Joyce had encountered the figure of Odysseus in ]'s ''Adventures of Ulysses'', an adaptation of the epic poem for children, which seems to have established the Latin name in Joyce's mind.{{sfn|Gorman|1939|p=45}}{{sfn|Jaurretche|2005|p=29}} ''Ulysses,'' a re-telling of the ''Odyssey'' set in ], is divided into eighteen sections ("episodes") which can be mapped roughly onto the twenty-four books of the ''Odyssey''.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |editor-last=Drabble |editor-first=Margaret |year=1995 |encyclopedia=The Oxford Companion to English Literature |entry=Ulysses |publisher=] |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-866221-1 |page=1023 }}</ref> Joyce claimed familiarity with the original Homeric Greek, but this has been disputed by some scholars, who cite his poor grasp of the language as evidence to the contrary.{{sfn|Ames|2005|loc=p. 17, "First of all, Joyce did own and read Homer in the original Greek, but his expertise was so minimal that he cannot justly be said to have known Homer in the original. Any typical young classical scholar in the second year of studying Greek would already possess more faculty with Homer than Joyce ever managed to achieve."}} The book, and especially its ] prose, is widely considered foundational to the modernist genre.<ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Williams |editor-first=Linda R. |year=1992 |title=The Bloomsbury Guides to English Literature: The Twentieth Century |publisher=Bloomsbury |location=London |pages=108–109 }}</ref> | |||

| ]'s '']'' begins where the ''Odyssey'' ends, with Odysseus leaving Ithaca again. | |||

| Modern writers have revisited the ''Odyssey'' to highlight the poem's female characters. Canadian writer ] adapted parts of the ''Odyssey'' for her novella '']'' (2005). The novella focuses on Penelope and the twelve female slaves hanged by Odysseus at the poem's ending,<ref>{{Cite news|last=Beard|first=Mary|date=28 October 2005|title=Review: Helen of Troy {{!}} Weight {{!}} The Penelopiad {{!}} Songs on Bronze |work=] |url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/oct/29/highereducation.classics|issn=0261-3077|archive-date=26 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160326055559/http://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/oct/29/highereducation.classics|url-status=live}}</ref> an image which haunted Atwood.<ref name="auto2">{{Cite web|date=28 October 2005|title=Margaret Atwood: A personal odyssey and how she rewrote Homer|url=http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/margaret-atwood-a-personal-odyssey-and-how-she-rewrote-homer-322675.html|website=] |archive-date=7 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200707112443/https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/margaret-atwood-a-personal-odyssey-and-how-she-rewrote-homer-322675.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Atwood's novella comments on the original text, wherein Odysseus' successful return to Ithaca symbolises the restoration of a ] system.<ref name="auto2"/> Similarly, ]'s '']'' (2018) revisits the relationship between Odysseus and Circe on Aeaea.<ref>{{Cite web|date=21 April 2018|title=Circe by Madeline Miller review – myth, magic and single motherhood|url=http://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/apr/21/circe-by-madeline-miller-review|website=the Guardian|language=en|archive-date=14 June 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200614111203/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/apr/21/circe-by-madeline-miller-review|url-status=live}}</ref> As a reader, Miller was frustrated by Circe's lack of motivation in the original poem and sought to explain her capriciousness.<ref>{{Cite news|title='Circe' Gets A New Motivation|url=https://www.npr.org/2018/04/15/602605359/circe-gets-a-new-motivation|website=NPR.org|language=en|archive-date=25 April 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180425180413/https://www.npr.org/2018/04/15/602605359/circe-gets-a-new-motivation|url-status=live}}</ref> The novel recontextualises the sorceress' transformations of sailors into pigs from an act of malice into one of self-defence, given that she has no superhuman strength with which to repel attackers.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Messud|first=Claire|date=28 May 2018|title=December's Book Club Pick: Turning Circe Into a Good Witch (Published 2018)|language=en-US|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/28/books/review/circe-madeline-miller.html|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=6 September 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200906104718/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/28/books/review/circe-madeline-miller.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Film and television=== | |||

| * '']'' (1911) is an Italian silent film by ].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Luzzi|first=Joseph|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EKPODwAAQBAJ&pg=PA11|title=Italian Cinema from the Silent Screen to the Digital Image|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|year=2020|isbn=9781441195616}}</ref> | |||

| * '']'' (1954) is an Italian film adaptation starring ] as Ulysses, ] as Penelope and Circe, and ] as Antinous.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Wilson |first1=Wendy S. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wR1ru604KPYC&pg=PA3 |title=World History On The Screen: Film And Video Resources:grade 10–12 |last2=Herman |first2=Gerald H. |publisher=Walch Publishing |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-8251-4615-2 |page=3 |archive-date=5 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200105061127/https://books.google.com/books?id=wR1ru604KPYC&pg=PA3 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * '']'' (1968) is an Italian-French-German-Yugoslavian television miniseries praised for its faithful rendering of the original epic.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Garcia Morcillo |first1=Marta |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DaugBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA139 |title=Imagining Ancient Cities in Film: From Babylon to Cinecittà |last2=Hanesworth |first2=Pauline |last3=Lapeña Marchena |first3=Óscar |date=11 February 2015 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-135-01317-2 |page=139 }}</ref> | |||

| * '']'' (1981–1982) is a French-Japanese television animated series set in the futuristic 31st century.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ulysses 31 |url=http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/343 |access-date=2024-06-08 |website=Our Mythical Childhood Survey}}</ref> | |||