| Revision as of 15:30, 1 June 2006 view sourceFalso~enwiki (talk | contribs)9 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:54, 10 January 2025 view source Wiqi55 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,573 editsm Fixing style/layout errors | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict| | |||

| {{Short description|629 AD battle in the Arab–Byzantine Wars}} | |||

| conflict=Battle of Mu'tah | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |partof=the Byzantine-Arab Wars| | |||

| | conflict = Battle of Mu'tah<br>{{lang|ar|غَزْوَة مُؤْتَة}}<br>{{lang|ar|مَعْرَكَة مُؤْتَة}} | |||

| |image= | |||

| | partof = the ] | |||

| |caption= | |||

| | image = Mausoleum ,Jafer-ut-Tayyar,Jordan.JPG | |||

| |date=] ], 8 AH | |||

| | caption = The tomb of Muslim commanders ], ], and ] in Al-Mazar near ], ] | |||

| |place=Near Ma'an, ] | |||

| | next_battle = ] | |||

| |result=Indecisive, ] ] | |||

| | date = September 629{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=72}} | |||

| |combatant1=Muslims | |||

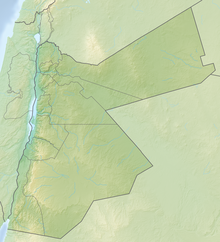

| | place = ], ] | |||

| |combatant2=]<br>] ]s | |||

| | coordinates = {{WikidataCoord|display=it}} | |||

| |commander1=]<br>]<br>]<br>] | |||

| | map_type = Jordan | |||

| |commander2=]<br>] | |||

| | map_relief = yes | |||

| |strength1=3,000 | |||

| | map_size = | |||

| |strength2=At least 50,000<br> | |||

| | map_marksize = | |||

| |casualties1=14 | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| |casualties2=Unknown, but heavy | |||

| | map_label = | |||

| |}} | |||

| | map_mark = | |||

| {{Campaignbox Rise of Islam}} | |||

| | casus = | |||

| {{Campaignbox Byzantine-Arab}} | |||

| | territory = | |||

| | result = Byzantine victory{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=67}}{{sfn|Donner|1981|p=105}}{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} | |||

| | combatant1 = ] | |||

| | combatant2 = ]<br>] | |||

| | commander1 = ]{{KIA}}<br>]{{KIA}}<br>]{{KIA}}<br>] {{small|(unofficial)}} | |||

| | commander2 = ]<br>Mālik ibn Zāfila{{KIA}} | |||

| | strength1 = 3,000{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=86}} | |||

| | strength2 = 100,000 (])<ref name=waqidi>{{Cite book| publisher = Cambridge University Press| isbn = 978-0-521-59984-9| last = Gil| first = Moshe| title = A History of Palestine, 634-1099| url = https://archive.org/details/historypalestine00gilm| url-access = limited| date = 1997-02-27|page=}}</ref><br>200,000 (])<ref name=ishaq>{{Cite book| publisher = Oxford University Press, USA| isbn = 0-19-636033-1| last = Ibn Ishaq| others = A. Guillaume (trans.)| title = The Life of Muhammad| date = 2004|quote=They went on their way as far as Ma‘ān in Syria where they heard that Heraclius had come down to Ma’āb in the Balqāʾ with 100,000 Greeks joined by 100,000 men from Lakhm and Judhām and al-Qayn and Bahrāʾ and Balī commanded by a man of Balī of Irāsha called Mālik b. Zāfila. (p. 232) Quṭba b. Qatāda al-‘Udhrī who was over the right wing had attacked Mālik b. Zāfila (Ṭ. leader of the mixed Arabs) and killed him, (p. 236) | pages=532, 536}}</ref><br>{{small|(both exaggerated)}}{{sfn|Haldon|2010|p=188}}{{sfn|Peters|1994|p=231}}{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} | |||

| 10,000 or fewer {{small|(modern estimate)}}{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=79}} | |||

| | casualties1 = 12<ref name=zayd>{{Cite book| publisher = University of Pennsylvania Press| isbn = 978-0-8122-4617-9| last = Powers| first = David S.| title = Zayd| date = 2014-05-23|pages=58–9}}</ref> {{small|(Disputed)}}{{sfn|Peterson|2007|p=142}}{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} | |||

| | casualties2 = Unknown | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Campaigns of Muhammad}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Arab–Byzantine Wars}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Campaigns of Khalid ibn Walid}} | |||

| The '''Battle of Mu'tah''' ({{langx|ar|مَعْرَكَة مُؤْتَة|translit=Maʿrakat Muʿtah}}, or {{langx|ar|غَزْوَة مُؤْتَة|link=no}} ''{{transl|ar|Ghazwat Muʿtah|link=no}}'') took place in September 629 (1 ] 8 ]),{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=72}} between the forces of ] and the army of the ] and their ] vassals. It took place in the village of ] in ] at the east of the ] and modern-day ]. | |||

| In Islamic historical sources, the battle is usually described as the Muslims' attempt to take retribution against a Ghassanid chief for taking the life of an emissary. According to Byzantine sources, the Muslims planned to launch their attack on a feast day. The local Byzantine ] learned of their plans and collected the garrisons of the fortresses. Seeing the great number of the enemy forces, the Muslims withdrew to the south where the fighting started at the village of Mu'tah and they were either routed or retired without exacting a penalty on the Ghassanid chief.<ref name=watt>{{Cite book| publisher = Oxford University Press| isbn = 978-0-353-30668-4| last = W| first = Montgomery Watt| title = Muhammad at Medina| date = 1956|pages=54–55, 342}}</ref>{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}}{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=67}} According to Muslim sources, after three of their leaders were killed, the command was given to ] and he succeeded in saving the rest of the force.{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} | |||

| ==Prelude== | |||

| Three years later the Muslims would return to defeat the Byzantine forces in the ]. | |||

| The Battle of Mutah (629 AD) was a battle fought during ]'s lifetime between ]s and the ]. Several of Muhammad's closest companions died in this battle. The graves of ], ], and ] are located in the town of Al-Mazar Al-Janubi near ].{{fact}} | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| At that time, Muhammad was sending messengers to leaders of powerful empires, inviting them to Islam. It had been almost two years since the ] was signed and Muhammed intended to spread Islam as much as possible in those years of peace with Quraish. | |||

| The Byzantines were reoccupying territory following the peace accord between Emperor ] and the ] in July 629.{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=72-73}} The Byzantine '']'' ],{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=35}} was placed in command of the army, and while in the area of Balqa, Arab tribes were also employed.{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=72-73}} | |||

| Meanwhile, Muhammad had sent his emissary to the ruler of Bostra.{{sfn|El Hareir|M'Baye|2011|p=142}} While on his way to Bostra, he was executed in the village of Mu'tah by the orders of a Ghassanid official ].{{sfn|El Hareir|M'Baye|2011|p=142}} | |||

| One of these messengers, Al-Harith bin ‘Umair Al-Azdi was sent to Busra. The messenger was killed at the hands of a Ghassanid chieftain, Sharhabeel bin ‘Amr Al-Ghassani, the governor of Al-Balqa’ and a close ally to Heraclius. Traditionally, emissaries held immunity from attack, and it was completely unacceptable to kill a messenger. It was considered disgraceful for the sender of the letter and for the addressee and couldn't just assume impunity. | |||

| ==Mobilization of the armies== | |||

| ==Preparations== | |||

| Muhammad dispatched 3,000 of his troops in the month of ] 7 (AH), 629 (CE), for a quick expedition to attack and punish the tribes for the murder of his emissary by the Ghassanids.{{sfn|El Hareir|M'Baye|2011|p=142}} The army was led by ]; the second-in-command was ] and the third-in-command was ].<ref name="zayd" /> When the Muslim troops arrived at the area to the east of Jordan and learned of the size of the Byzantine army, they wanted to wait and send for reinforcements from ]. 'Abdullah ibn Rawahah reminded them about their desire for martyrdom and questioned the move to wait when what they desire was awaiting them, so they continued marching towards the waiting army. | |||

| ==Battle== | |||

| Muhammed, upon hearing the news ordered an army of 3,000 soldiers be mobilized and sent north to the Ghassanids to avenge the death of the emissary. It was the largest army ever mobilized by the Muslims. As there was very little money available to raise the army, Muhammed asked for donations. He received a lot of money, most notably from ], ], and ]. | |||

| The Muslims engaged the Byzantines at their camp by the village of Musharif and then withdrew towards Mu'tah. It was here that the two armies fought. Some Muslim sources report that the battle was fought in a valley between two heights, which negated the Byzantines' numerical superiority. During the battle, all three Muslim leaders fell one after the other as they took command of the force: first, Zayd, then Ja'far, then 'Abdullah. The leader of the Arab vassal forces, Mālik ibn Zāfila, was also killed in battle.<ref name=ishaq /> After the death of 'Abdullah, the Muslim soldiers were in danger of being routed. Thabit ibn Aqram, seeing the desperate state of the Muslim forces, took up the banner and rallied his comrades, thus saving the army from complete destruction. After the battle, ibn Aqram took the banner, before asking ] to take the lead.<ref name="Al-Islam Ja'far">{{citation |publisher=] |title=Jafar al-Tayyar |url=http://www.al-islam.org/jafar-al-tayyar-kamal-al-sayyid/jafar-al-tayyar/ }}</ref> | |||

| ==Muslim losses== | |||

| Muhammed ordered the army: | |||

| Four of the slain Muslims were ] (early Muslim converts who emigrated from Mecca to Medina) and eight were from the ] (early Muslim converts native to Medina). Those slain Muslims named in the sources were ], ], ], Mas'ud ibn al-Aswad, ], Abbad ibn Qays, Amr ibn Sa'd, Harith ibn Nu'man, Suraqa ibn Amr, Abu Kulayb ibn Amr, Jabir ibn Amr and Amir ibn Sa'd. | |||

| "Fight the disbelievers in the Name of Allah, neither breach a covenant nor entertain treachery, and under no circumstances a new-born, woman, an ageing man or a hermit should be killed; moreover neither trees should be cut down nor homes demolished." (Mukhtasar Seerat Ar-Rasool, p.327) | |||

| Daniel C. Peterson, Professor of Islamic Studies at Brigham Young University, finds the ratio of casualties among the leaders suspiciously high compared to the losses suffered by ordinary soldiers.{{sfn|Peterson|2007|p=142}} David Powers, Professor of Near Eastern Studies at Cornell, also mentions this curiosity concerning the minuscule casualties recorded by Muslim historians.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} ] argues that a low casualty count is possible if the nature of this encounter was a ] or if the Muslims completely routed the enemy.<ref name=watt /> He further notes that the discrepancy between leaders and ordinary soldiers is not inconceivable in view of Arab fighting methods.<ref name=watt /> | |||

| The Muslim army, led by ], marched northwards to Ma'an. There, news came to effect that Malik ibn Zafila had mobilized nearly 50,000 Ghassanid soldiers, and Heraclius was assisting him with another 50,000 Roman troops, and were stationed in Bulqa'. The Muslims for their part had never thought that they were going encounter such an army. Two nights were spent debating on what to do. It was suggested that they inform Muhammed of the situation and seek advice. ], in a motivating speech of encouragement disagreed on informing Muhammed and favoured countering the Romans in a motivating speech of encouragement. The Muslims agreed and decided to engage with the Romans at Mu'tah. | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| At Mu'tah was a valley between two heights. The width of the valley was such that it could have about 2,000 soldiers. If the Muslim army positions itself there, the Romans would be unable to use their entire army, but rather will only be able to fight the Muslims with the same number of troops. This would be a great strategic advantage for the numerically inferior Muslims. So the army went to Mu'tah. | |||

| After the Muslim forces arrived at Medina, they were reportedly berated for withdrawing and accused of fleeing.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=81}} Salamah ibn Hisham, brother of ] (Abu Jahl) was reported to have prayed at home rather than going to the mosque to avoid having to explain himself. Muhammad ordered them to stop, saying that they would return to fight the Byzantines again.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=81}} According to Watt, most of these accounts were intended to vilify Khalid and his decision to return to Medina, as well as to glorify the part played by members of one's family.<ref name=watt /> It would not be until the third century AH that Sunni Muslim historians would state that Muhammad bestowed upon Khalid the title of 'Saifullah' meaning 'Sword of Allah'.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} | |||

| Today, Muslims who fell at the battle are considered ]s ('']''). A ] was later built at Mu'tah over their graves.{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} | |||

| The Romans were disappointed that they would be unable to fight the Muslims with all their strength. Nevertheless they were confident that they could win an easy victory. Heraclius moved his troops from Balqa' to Mu'tah to engage with the Muslim army. | |||

| == |

==Historiography== | ||

| ] | |||

| According to ] (d. 823) and ] (d. 767), the Muslims were informed that 100,000<ref name=waqidi /> or 200,000<ref name=ishaq/> enemy troops were encamped at the ]'.<ref name=waqidi />{{sfn|Haykal|1976|p=419}} Some modern historians state that the figure is exaggerated.{{sfn|Haldon|2010|p=188}}{{sfn|Peters|1994|p=231}}{{sfn|Buhl|1993|p=756-757}} According to Walter Emil Kaegi, professor of Byzantine history at the ], the size of the entire Byzantine army during the 7th century might have totaled 100,000, possibly even half this number.{{sfn|Kaegi|2010|p=99}} While the Byzantine forces at Mu'tah are unlikely to have numbered more than 10,000.{{efn|The Byzantines do not appear to have used many Greek, Armenian, or other non-Arab soldiers at Mu'ta, even though the overall commander was the ''vicarius'' Theodore. The number that the Byzantines raised are, of course, uncertain, but unlikely to have exceeded 10,000.{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=79}}}}{{sfn|Kaegi|1992|p=79}} | |||

| The Romans were disappointed that they would be unable to fight the Muslims with all their strength. Nevertheless they were confident that they could win an easy victory. Heraclius moved his troops from Balqa' to Mu'tah to engage with the Muslim army. Bitter fighting took place over the next few days. ] reported that the fighting was so intense that he used nine swords which broke in the battle. The Muslim commander, Zayd ibn Harithah was killed. | |||

| Muslim accounts of the battle differ over the result.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} According to David S. Powers, the earliest Muslim sources like al-Waqidi record the battle as a humiliating defeat (''hazīma'').{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} However, ] notes that al-Waqidi also recorded an account where the Byzantine forces fled.<ref name=watt /> Powers suggests that later Muslim historians reworked the early source material to reflect the Islamic view of God's plan.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} Subsequent sources present the battle as a Muslim victory given that most of the Muslim soldiers returned safely.{{sfn|Powers|2009|p=80}} | |||

| The deputy commander of the army was the companion ], ]'s brother and Muhammad's cousin, then took the banner after Zaid, before he himself was killed. ] reported fifty stabs in Jafar's body. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| The companion ], the third in charge of the army after Zaid and Jafar, then assumed command. Before being killed, Abdullah said the following lines as his army faced an overwhelming number of ] and ] Arab troops: ''"O my soul! If you are not killed, you are bound to die anyway. This is the fate of death overtaking you. What you have wished for, you have been granted. If you do what they (Zaid and Ja'far) have done. Then you are rightly guided".'' {{fact}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| In the six days of the battle, several hundreds of the Romans were killed and the Muslims lost 14 soldiers. This was mainly due to the very poor morale of the Roman army, while the Muslims were very enthusiastic, despite the large difference in number. After all three chosen commanders were killed in the fighting, Khalid ibn Al-Walid became in charge. Having avenged the blood of the emissary, and seeing that the battle could not be won, Khalid decided to retreat, and devised a cunning plan. | |||

| {{Notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| Khalid reshuffled the right and left flanks of the army and brought forward a division from the rear. New banners were made for the army. He also ordered the cavalry to position themselves behind the hill south of the Muslim army. Then, upon his order, march towards the army in six waves. Khalid wanted the Romans to think that a new army had arrived. | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| As the fifth wave of horsemen approached, Khalid ordered the army to attack. After some time, he ordered the entire army to retreat in six waves. The Romans did not follow the Muslim army, and remained in their positions, expecting another attack. Consequently, the Muslims managed to retreat safely all the way to Madinah. | |||

| Even though the battle was not conclusive, the Muslims proved themselves as a rising potential global power in the face of the Romans and the Persians. | |||

| ==Sources== | ==Sources== | ||

| *{{cite book |first=Fred M. |last=Donner |author-link=Fred M. Donner |year=1981 |title=The Early Islamic Conquests |publisher=Princeton University Press }} | |||

| <div class="references-small"> | |||

| *{{cite book |title=The Different Aspects of Islam Culture: Volume 3, The Spread of Islam throughout the World |last1=El Hareir |first1=Idris |last2=M'Baye |first2=El Hadji Ravane |publisher=UNESCO publishing |year=2011 }} | |||

| *'']'', ], 1957 | |||

| *{{Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition|volume=7|title=Muʾta|last=Buhl |first=F.|author-link=|pages=756}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria |last=Haldon |first=John |author-link=John Haldon |publisher=Ashgate Publishing |year=2010 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=The Life of Muhammad |last=Haykal |first=Muhammad |publisher=Islamic Book Trust |year=1976 }} | |||

| *{{Cite book| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=IvPVEb17uzkC| title = Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests| last = Kaegi| first = Walter E. |author-link=Walter Kaegi | publisher = Cambridge University Press| year = 1992| isbn = 978-0521411721|location = Cambridge}} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa |last=Kaegi |first=Walter E. |author-link=Walter Kaegi |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-521-19677-2 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Muhammad and the Origins of Islam |url=https://archive.org/details/muhammadorigins00pete |url-access=registration |last=Peters |first=Francis E. |publisher=State University of New York Press |year=1994 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Muhammad, Prophet of God |last=Peterson |first=Daniel C. |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. |year=2007 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=Muhammad Is Not the Father of Any of Your Men: The Making of the Last Prophet |last=Powers |first=David S. |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2009 |isbn=9780812205572 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KH2FUBSOQ8kC }} | |||

| *{{cite book |title=A Global Chronology of Conflict |volume=I |editor-last=Tucker |editor-first=Spencer |editor-link= Spencer C. Tucker |publisher=ABC-CLIO |year=2010 }} | |||

| == |

==Further reading== | ||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * | |||

| *] | |||

| * | |||

| *] | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Islam-stub}} | |||

| {{battle-stub}} | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:54, 10 January 2025

629 AD battle in the Arab–Byzantine Wars

| Battle of Mu'tah غَزْوَة مُؤْتَة مَعْرَكَة مُؤْتَة | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab–Byzantine wars | |||||||

The tomb of Muslim commanders Zayd ibn Haritha, Ja'far ibn Abi Talib, and Abd Allah ibn Rawahah in Al-Mazar near Mu'tah, Jordan | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Muslim Arabs |

Byzantine Empire Ghassanids | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Zayd ibn Haritha † Ja'far ibn Abi Talib † Abd Allah ibn Rawaha † Khalid ibn al-Walid (unofficial) |

Theodore Mālik ibn Zāfila † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,000 | 10,000 or fewer (modern estimate) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12 (Disputed) | Unknown | ||||||

| |||||||

| Campaigns of Muhammad | |

|---|---|

| Further information: Military career of Muhammad |

| Arab–Byzantine wars | |

|---|---|

Early conflicts

Border conflicts

Sicily and Southern Italy

Naval warfare

Byzantine reconquest

|

| Campaigns of Khalid ibn al-Walid | |

|---|---|

Campaigns under Muhammad

|

The Battle of Mu'tah (Arabic: مَعْرَكَة مُؤْتَة, romanized: Maʿrakat Muʿtah, or Arabic: غَزْوَة مُؤْتَة Ghazwat Muʿtah) took place in September 629 (1 Jumada al-Awwal 8 AH), between the forces of Muhammad and the army of the Byzantine Empire and their Ghassanid vassals. It took place in the village of Mu'tah in Palaestina Salutaris at the east of the Jordan River and modern-day Karak.

In Islamic historical sources, the battle is usually described as the Muslims' attempt to take retribution against a Ghassanid chief for taking the life of an emissary. According to Byzantine sources, the Muslims planned to launch their attack on a feast day. The local Byzantine Vicarius learned of their plans and collected the garrisons of the fortresses. Seeing the great number of the enemy forces, the Muslims withdrew to the south where the fighting started at the village of Mu'tah and they were either routed or retired without exacting a penalty on the Ghassanid chief. According to Muslim sources, after three of their leaders were killed, the command was given to Khalid ibn al-Walid and he succeeded in saving the rest of the force.

Three years later the Muslims would return to defeat the Byzantine forces in the Expedition of Usama bin Zayd.

Background

The Byzantines were reoccupying territory following the peace accord between Emperor Heraclius and the Sasanid general Shahrbaraz in July 629. The Byzantine sakellarios Theodore, was placed in command of the army, and while in the area of Balqa, Arab tribes were also employed.

Meanwhile, Muhammad had sent his emissary to the ruler of Bostra. While on his way to Bostra, he was executed in the village of Mu'tah by the orders of a Ghassanid official Shurahbil ibn Amr.

Mobilization of the armies

Muhammad dispatched 3,000 of his troops in the month of Jumada al-Awwal 7 (AH), 629 (CE), for a quick expedition to attack and punish the tribes for the murder of his emissary by the Ghassanids. The army was led by Zayd ibn Harithah; the second-in-command was Ja'far ibn Abi Talib and the third-in-command was Abd Allah ibn Rawahah. When the Muslim troops arrived at the area to the east of Jordan and learned of the size of the Byzantine army, they wanted to wait and send for reinforcements from Medina. 'Abdullah ibn Rawahah reminded them about their desire for martyrdom and questioned the move to wait when what they desire was awaiting them, so they continued marching towards the waiting army.

Battle

The Muslims engaged the Byzantines at their camp by the village of Musharif and then withdrew towards Mu'tah. It was here that the two armies fought. Some Muslim sources report that the battle was fought in a valley between two heights, which negated the Byzantines' numerical superiority. During the battle, all three Muslim leaders fell one after the other as they took command of the force: first, Zayd, then Ja'far, then 'Abdullah. The leader of the Arab vassal forces, Mālik ibn Zāfila, was also killed in battle. After the death of 'Abdullah, the Muslim soldiers were in danger of being routed. Thabit ibn Aqram, seeing the desperate state of the Muslim forces, took up the banner and rallied his comrades, thus saving the army from complete destruction. After the battle, ibn Aqram took the banner, before asking Khalid ibn al-Walid to take the lead.

Muslim losses

Four of the slain Muslims were Muhajirin (early Muslim converts who emigrated from Mecca to Medina) and eight were from the Ansar (early Muslim converts native to Medina). Those slain Muslims named in the sources were Zayd ibn Haritha, Ja'far ibn Abi Talib, Abd Allah ibn Rawaha, Mas'ud ibn al-Aswad, Wahb ibn Sa'd, Abbad ibn Qays, Amr ibn Sa'd, Harith ibn Nu'man, Suraqa ibn Amr, Abu Kulayb ibn Amr, Jabir ibn Amr and Amir ibn Sa'd.

Daniel C. Peterson, Professor of Islamic Studies at Brigham Young University, finds the ratio of casualties among the leaders suspiciously high compared to the losses suffered by ordinary soldiers. David Powers, Professor of Near Eastern Studies at Cornell, also mentions this curiosity concerning the minuscule casualties recorded by Muslim historians. Montgomery Watt argues that a low casualty count is possible if the nature of this encounter was a skirmish or if the Muslims completely routed the enemy. He further notes that the discrepancy between leaders and ordinary soldiers is not inconceivable in view of Arab fighting methods.

Aftermath

After the Muslim forces arrived at Medina, they were reportedly berated for withdrawing and accused of fleeing. Salamah ibn Hisham, brother of Amr ibn Hishām (Abu Jahl) was reported to have prayed at home rather than going to the mosque to avoid having to explain himself. Muhammad ordered them to stop, saying that they would return to fight the Byzantines again. According to Watt, most of these accounts were intended to vilify Khalid and his decision to return to Medina, as well as to glorify the part played by members of one's family. It would not be until the third century AH that Sunni Muslim historians would state that Muhammad bestowed upon Khalid the title of 'Saifullah' meaning 'Sword of Allah'.

Today, Muslims who fell at the battle are considered martyrs (shuhadāʾ). A mausoleum was later built at Mu'tah over their graves.

Historiography

According to al-Waqidi (d. 823) and Ibn Ishaq (d. 767), the Muslims were informed that 100,000 or 200,000 enemy troops were encamped at the Balqa'. Some modern historians state that the figure is exaggerated. According to Walter Emil Kaegi, professor of Byzantine history at the University of Chicago, the size of the entire Byzantine army during the 7th century might have totaled 100,000, possibly even half this number. While the Byzantine forces at Mu'tah are unlikely to have numbered more than 10,000.

Muslim accounts of the battle differ over the result. According to David S. Powers, the earliest Muslim sources like al-Waqidi record the battle as a humiliating defeat (hazīma). However, Montgomery Watt notes that al-Waqidi also recorded an account where the Byzantine forces fled. Powers suggests that later Muslim historians reworked the early source material to reflect the Islamic view of God's plan. Subsequent sources present the battle as a Muslim victory given that most of the Muslim soldiers returned safely.

See also

- Military career of Muhammad

- List of expeditions of Muhammad

- History of Islam

- Jihad

- Muhammad's views on Christians

Notes

- The Byzantines do not appear to have used many Greek, Armenian, or other non-Arab soldiers at Mu'ta, even though the overall commander was the vicarius Theodore. The number that the Byzantines raised are, of course, uncertain, but unlikely to have exceeded 10,000.

References

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 72.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 67.

- Donner 1981, p. 105.

- ^ Buhl 1993, p. 756-757.

- Powers 2009, p. 86.

- ^ Gil, Moshe (1997-02-27). A History of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-59984-9.

- ^ Ibn Ishaq (2004). The Life of Muhammad. A. Guillaume (trans.). Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 532, 536. ISBN 0-19-636033-1.

They went on their way as far as Ma'ān in Syria where they heard that Heraclius had come down to Ma'āb in the Balqāʾ with 100,000 Greeks joined by 100,000 men from Lakhm and Judhām and al-Qayn and Bahrāʾ and Balī commanded by a man of Balī of Irāsha called Mālik b. Zāfila. (p. 232) Quṭba b. Qatāda al-'Udhrī who was over the right wing had attacked Mālik b. Zāfila (Ṭ. leader of the mixed Arabs) and killed him, (p. 236)

- ^ Haldon 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Peters 1994, p. 231.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 79.

- ^ Powers, David S. (2014-05-23). Zayd. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 58–9. ISBN 978-0-8122-4617-9.

- ^ Peterson 2007, p. 142.

- ^ Powers 2009, p. 80.

- ^ W, Montgomery Watt (1956). Muhammad at Medina. Oxford University Press. pp. 54–55, 342. ISBN 978-0-353-30668-4.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 72-73.

- Kaegi 1992, p. 35.

- ^ El Hareir & M'Baye 2011, p. 142.

- Jafar al-Tayyar, Al-Islam.org

- ^ Powers 2009, p. 81.

- Haykal 1976, p. 419.

- Kaegi 2010, p. 99.

Sources

- Donner, Fred M. (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton University Press.

- El Hareir, Idris; M'Baye, El Hadji Ravane (2011). The Different Aspects of Islam Culture: Volume 3, The Spread of Islam throughout the World. UNESCO publishing.

- Buhl, F. (1993). "Muʾta". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 756. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Haldon, John (2010). Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria. Ashgate Publishing.

- Haykal, Muhammad (1976). The Life of Muhammad. Islamic Book Trust.

- Kaegi, Walter E. (1992). Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521411721.

- Kaegi, Walter E. (2010). Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- Peters, Francis E. (1994). Muhammad and the Origins of Islam. State University of New York Press.

- Peterson, Daniel C. (2007). Muhammad, Prophet of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

- Powers, David S. (2009). Muhammad Is Not the Father of Any of Your Men: The Making of the Last Prophet. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812205572.

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict. Vol. I. ABC-CLIO.