| Revision as of 20:41, 16 June 2015 editAtsme (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers42,818 edits remove unsupported anectodal claims that are irrelevant to the product← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:43, 8 January 2025 edit undoAnomieBOT (talk | contribs)Bots6,578,540 edits Rescuing orphaned refs (":3" from rev 1268030410) | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Fermented tea beverage}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{About|the fermented tea|the East Asian drink "konbu-cha", made from dried seaweed|kelp tea}} | |||

| '''Kombucha''' (Russian: chaynyy grib (чайный гриб), Chinese: chájūn (茶菌), Korean: hongchabeoseotcha (홍차버섯차), Japanese: kōcha-kinoko (紅茶キノコ)), is a lightly ] ] of sweetened ] and/or ] tea that is used as a ]. It is produced by fermenting the tea using a ] (SCOBY). | |||

| {{Redirect|Tea mushroom|the tea tree mushroom used in Chinese cooking|Cyclocybe aegerita}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2024}} | |||

| There have not been any human trials conducted to confirm any curative claims associated with the consumption of kombucha tea.<ref name=Jayabalan>{{cite journal |first1= R |last1= Jayabalan |first2= RV |last2= Malbaša |first3= ES |last3= Lončar |first4= JS |last4= Vitas |first5= M |last5= Sathishkumar |date= July 2014 |title= A Review on Kombucha Tea — Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus |journal= ] |volume= 13 |issue= 4 |pages= 538–50 |doi= 10.1111/1541-4337.12073 | quote="a source of pharmacologically active molecules, an important member of the antioxidant food group, and a functional food with potential beneficial health properties."}}</ref>A small number of random anecdotal reports have raised concern over the potential for contamination during home preparation, as well as toxicity concerns due in part to the leaching of lead in ceramic containers during fermentation.<ref name=Jayabalan/> | |||

| {{Infobox beverage | |||

| | name = Kombucha | |||

| | type = Flavored cold tea drink with ] byproducts | |||

| | image = Kombucha Mature.jpg | |||

| | caption = Kombucha tea, including the culture of bacteria and yeast, which is not usually consumed | |||

| | image_alt = Glass jar filled with brown kombucha beverage, including the floating culture | |||

| | origin = China | |||

| | color = Cloudy, commonly pale or dark brown and sometimes green | |||

| | abv = <0.5% (commercial) | |||

| | proof = <1 (commercial) | |||

| | flavor = Fermented, effervescent | |||

| | related = ], ], ], beer, ] | |||

| | ingredients = Tea, sugar, bacteria, ] | |||

| | variants = ]s or spices added | |||

| }} | |||

| <!-- Beverage description --> | |||

| '''Kombucha''' (also '''tea mushroom''', '''tea fungus''', or '''Manchurian mushroom''' when referring to the ]; Latin name ''Medusomyces gisevii'')<ref name=Jayabalan/> is a ], lightly ], ] ] drink. Sometimes the beverage is called '''kombucha tea''' to distinguish it from the culture of bacteria and ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/expert-answers/kombucha-tea/faq-20058126|title=A mug of kombucha for your health?|work=Mayo Clinic|access-date=1 September 2018}}</ref> Juice, spices, fruit or other flavorings are often added. | |||

| Kombucha is thought to have originated in China, where the drink is traditional.<ref>{{Cite web|title=kombucha {{!}} Description, History, & Nutrition|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/kombucha|access-date=20 April 2021|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite book|last=Alex.|first=LaGory|url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/1051088525|title=The Big Book of Kombucha|date=2016|publisher=Storey Publishing, LLC|isbn=978-1-61212-435-3|pages=251|oclc=1051088525}}</ref> By the early 20th century it spread to Russia, then other parts of Eastern Europe and Germany.<ref name="Troitino2017">{{cite news|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinatroitino/2017/02/01/kombucha-101-demystifying-the-past-present-and-future-of-the-fermented-tea-drink/|title=Kombucha 101: Demystifying The Past, Present And Future Of The Fermented Tea Drink|last=Troitino|first=Christina|work=Forbes|access-date=10 April 2017}}</ref> Kombucha is now ] globally, and also bottled and sold commercially.<ref name="Jayabalan" /> The global kombucha market was worth approximately {{US$|1.7}}{{thinsp}}billion {{as of|2019|lc=yes}}.<ref name=big-kombu/> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| <!-- Culture description --> | |||

| In Japan, {{nihongo3|"kelp tea"|昆布茶|Konbucha}} refers to a different beverage made from dried and powdered '']'' (an edible ] from the ] family).<ref>{{cite news |last=Wong |first=Crystal. |url=http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2007/07/12/national/u-s-kombucha-smelly-and-no-kelp/ |title=U.S. 'kombucha': Smelly and No Kelp |work=Japan Times |date=12 July 2007 |accessdate=14 June 2015}}.</ref> | |||

| Kombucha is produced by ] of sugared tea using a ] culture of bacteria and yeast (]) commonly called a "mother" or "mushroom". The ] populations in a SCOBY vary. The yeast component generally includes '']'', along with other species; the bacterial component almost always includes '']'' to ] yeast-produced ] to ] (and other acids).<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Jonas|first1=Rainer|last2=Farah|first2=Luiz F.|title=Production and application of microbial cellulose|journal=Polymer Degradation and Stability|volume=59|issue=1–3|pages=101–106|doi=10.1016/s0141-3910(97)00197-3|year=1998}}</ref> Although the SCOBY is commonly called "tea fungus" or "mushroom", it is actually "a symbiotic growth of acetic acid bacteria and ] yeast species in a zoogleal mat {{bracket|]}}".<ref name=Jayabalan/> The living bacteria are said to be ], one of the reasons for the popularity of the drink.<ref name="bauer">{{Cite news|url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/expert-answers/kombucha-tea/faq-20058126|title=What is kombucha tea? Does it have any health benefits?|last=Bauer|first=Brent|date=8 July 2017|work=Mayo Clinic|access-date=5 September 2018}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/25/fashion/25Tea.html|title=Kombucha Tea Attracts a Following and Doubters|last=Wollan|first=Malia|work=The New York Times |date=24 March 2010 |access-date=5 September 2018}}</ref> | |||

| For the origin of the English word '']'', in use since at least 1991<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.nytimes.com/1994/12/28/garden/a-magic-mushroom-or-a-toxic-fad.html |work=New York Times |date=28 December 1994 |last=O'Neill |first=Molly |accessdate=14 June 2015 |title=A Magic Mushroom Or a Toxic Fad?}}</ref> and of uncertain ],<ref>{{cite journal |first1=John |last1=Algeo |first2=Adele |last2=Algeo |year=1997 |title=Among the New Words |journal=American Speech |volume=72 |issue=2 |pages=183–97 |jstor=455789 |doi=10.2307/455789}}</ref> the '']'' suggests: "Probably from Japanese ''kombucha'', tea made from ''kombu'' (the Japanese word for kelp perhaps being used by English speakers to designate fermented tea due to confusion or because the thick gelatinous film produced by the ''kombucha culture'' was thought to resemble seaweed)."<ref>''American Heritage Dictionary'', 4th ed. 2000, updated 2009, Houghton Mifflin Company. , ].</ref> | |||

| <!-- Health claims and safety concerns --> | |||

| The Japanese name for what English speakers know as kombucha is ''kōcha kinoko'' 紅茶キノコ (literally, 'black tea mushroom'), compounding '']'' "black tea" and '']'' ] "mushroom; toadstool". The ] names for kombucha are ''hóngchájùn'' 红茶菌 ('red tea fungus'), ''cháméijūn'' 茶黴菌 ('tea mold'), or ''hóngchágū'' 红茶菇 ('red tea mushroom'), with ''jūn'' ] 'fungus, bacterium or germ' (or ''jùn'' 'mushroom'), ''méijūn'' ] 'mold or fungus', and ''gū'' ] 'mushroom'. ("Red tea", ], in Chinese languages corresponds to English "black tea".) | |||

| Numerous health benefits have been claimed to correlate with drinking kombucha;<ref name="Ernst2003" /> there is little ] to support any of these claims.<ref name="bauer" /><ref name="Ernst2003" /><ref>{{Cite journal|title=Kombucha: a systematic review of the empirical evidence of human health benefit|year=2019|publisher=Elsevier|pmid=30527803|last1=Kapp|first1=J. M.|last2=Sumner|first2=W.|journal=Annals of Epidemiology|volume=30|pages=66–70|doi=10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.11.001|s2cid=54472564|doi-access=free}}</ref> The beverage has caused rare serious ]s, possibly arising from ] during ].<ref name=mskcc/><ref name="acs" /> It is not recommended for ].<ref name="Ernst2003" /><ref name=mayo>{{Cite web|title=What is kombucha tea? Does it have any health benefits?|url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/expert-answers/kombucha-tea/faq-20058126|last=Bauer|first=Brent|website=Mayo Clinic|access-date=28 May 2020}}</ref> | |||

| A 1965 mycological study called kombucha "tea fungus" and listed other names: "teeschwamm, Japanese or Indonesian tea fungus, kombucha, wunderpilz, hongo, cajnij, fungus japonicus, and teekwass".<ref>{{cite journal |first1=C. W. |last1=Hesseltine |year=1965 |title=A Millennium of Fungi, Food, and Fermentation |journal=Mycologia |volume=57 |issue=2 |pages=149–97 |jstor=3756821 |pmid=14261924 |doi=10.2307/3756821}}</ref> Some further spellings and synonyms include combucha and tschambucco, and haipao, kargasok tea, kwassan, Manchurian fungus or mushroom, spumonto, as well as the misnomers ] of life, and ] from the sea.<ref name=mskcc>{{cite web |url=https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/kombucha |publisher=] |title=Kombucha |date=22 May 2014 |accessdate=June 2015}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| Kombucha |

Kombucha likely originated in the ] region of China.<ref name=":1" /> It spread to Russia before reaching Europe and gained popularity in the United States in the early 21st century.<ref name="Sreermalu2000">{{cite journal |last1=Sreeramulu |first1=G |last2=Zhu |first2=Y |last3=Knol |first3=W |year=2000 |title=Kombucha fermentation and its antimicrobial activity |url=https://research.kombuchabrewers.org/wp-content/uploads/kk-research-files/kombucha-fermentation-and-its-antimicrobial-activity.pdf |journal=] |volume=48 |issue=6 |pages=2589–2594 |bibcode=2000JAFC...48.2589S |doi=10.1021/jf991333m |pmid=10888589 |quote=It originated in northeast China (Manchuria) and later spread to Russia and the rest of the world.}}</ref><ref name="hamblin">{{cite web |author=Hamblin, James |date=8 December 2016 |title=Is Fermented Tea Making People Feel Enlightened Because of ... Alcohol? |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/12/the-promises-of-kombucha/509786/ |access-date=26 November 2017 |publisher=The Atlantic}}</ref><ref name="Katz2012">{{cite book |author=Sandor Ellix Katz |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TjXEAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA167 |title=The Art of Fermentation: An In-depth Exploration of Essential Concepts and Processes from Around the World |publisher=Chelsea Green Publishing |year=2012 |isbn=978-1-60358-286-5 |pages=167–}}</ref> With an alcohol content under 0.5%, it is not federally regulated in the U.S.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hard Kombucha Is Super Trendy, but Is It Good for You? We Asked Nutritionists |url=https://www.health.com/food/hard-kombucha |website=Health.com}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Hard Kombucha Is the New Trendy Beverage You Should Try |url=https://www.bhg.com/recipes/trends/hard-kombucha/ |website=Better Homes & Gardens}}</ref> | ||

| Prior to 2015, some commercially available kombucha brands were found to contain alcohol content exceeding this threshold, sparking the development of new testing methods.<ref>{{cite news|url= https://apnews.com/23ca8b0eafd740838f7fd379eba32b42/kombucha-sales-boom-makers-ask-feds-new-alcohol-test|title= As kombucha sales boom, makers ask feds for new alcohol test|publisher= Associated Press|author =Wyatt, Kristen|date= 12 October 2015|access-date= 26 November 2017}}</ref> With rising popularity in ] in the early 21st century, kombucha sales increased after it was marketed as an alternative to beer and other alcoholic drinks in restaurants and ]s.<ref name=":0">{{Cite news|url= https://www.theguardian.com/food/2018/oct/11/kombucha-can-the-fermented-drink-compete-with-beer-at-the-bar|title= Kombucha: can the fermented drink compete with beer at the bar?|last= Fleming|first= Amy|date= 11 October 2018|newspaper= The Guardian|language= en|access-date= 11 October 2018}}</ref> | |||

| Kombucha's English name is derived from Japanese. According to folklore, it was introduced to Japan by a Korean doctor named Kombu as a health tonic.<ref name=trendy/> | |||

| According to the market research firm ],{{clarify|date=June 2022}} kombucha had a global market size of {{US$|1.67}}{{thinsp}}billion, {{as of|lc=yes|2019}} and this is expected to grow to {{US$|9.7}}{{thinsp}}billion by 2030.<ref name=big-kombu>{{cite web |publisher=Grandview Research |url=https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/kombucha-market |date=February 2020 |title=Kombucha Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Flavor (Original, Flavored), By Distribution Channel (Supermarkets, Health Stores, Online Stores), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2020 – 2027}}</ref> | |||

| == Chemical and biological properties== | |||

| ==Etymology and terminology== | |||

| ] | |||

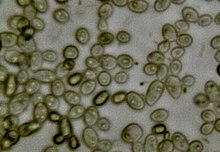

| A kombucha culture is a ] (SCOBY), containing '']'' (a genus of ]) and one or more yeasts, which form a ]. In Chinese, the ] is called ''haomo'' in Cantonese, or ''jiaomu'' in Mandarin, ({{zh|c=酵母|l=fermentation mother}}). It is also known as Manchurian Mushroom. | |||

| The ] of ''kombucha'' is uncertain, but it is believed to be a misapplied ] from Japanese.<ref name="Algeo97">{{cite journal |last1=Algeo |first1=John |last2=Algeo |first2=Adele |year=1997 |title=Among the New Words |journal=American Speech |volume=72 |issue=2 |pages=183–97 |doi=10.2307/455789 |jstor=455789}}</ref> English speakers may have confused the Japanese word ''konbucha'' (which refers to fermented tea) with {{nihongo3|'black tea mushroom'<!--Although "紅" means red, "紅茶" means "black tea" as in Chinese because of colour of the oxidized leaves and tea. See ]. -->|]|kōcha kinoko}}, popularized around 1975.<ref>{{cite news |last=Wong |first=Crystal |date=12 July 2007 |title=U.S. 'kombucha': Smelly and No Kelp |url=http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2007/07/12/national/u-s-kombucha-smelly-and-no-kelp/ |access-date=14 June 2015 |work=Japan Times}}.</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |title=紅茶キノコ(こうちゃキノコ)とは? 意味や使い方 |trans-title=What is "red tea mushroom"? – meaning and usage |url=https://kotobank.jp/word/%E7%B4%85%E8%8C%B6%E3%82%AD%E3%83%8E%E3%82%B3-163231 |access-date=2024-05-20 |website=] |language=ja}}</ref> {{Improve-refs|reason=older Japan Times articles don't seem to be available or only with subscription|date=January 2025}}'']'s Dictionary'' suggests kombucha in English arose from misapplication of Japanese words like ''konbucha'', ''kobucha'' ']', ''konbu'', from ''kobu'' 'kelp', + cha ']'.<ref name="Definition of KOMBUCHA">{{Cite web |title=Definition of KOMBUCHA |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/kombucha |access-date=29 May 2019 |website=www.merriam-webster.com |language=en}}</ref> '']'' notes the term might have originated from the belief that the gelatinous film of kombucha resembled seaweed.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Kombucha |encyclopedia=American Heritage Dictionary |publisher=] |url=http://www.thefreedictionary.com/kombucha |access-date=27 June 2015 |date=2015 |edition=Fifth}}</ref> | |||

| Kombucha cultures may contain one or more of the ''yeasts'' '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', and '']''. | |||

| In Japanese, the term {{nihongo3|']'|昆布茶|konbu-cha}} refers to a kelp tea made with powdered '']'' (an edible ] from the family ]) and is a completely different beverage from the fermented tea usually associated with ''kombucha'' elsewhere in the world.<ref name=":3"></ref> | |||

| Although the ''bacterial component'' of a kombucha culture comprises several species, it almost always includes ''Gluconacetobacter xylinus'' (formerly '']''), which ferments the alcohol(s) produced by the yeast(s) into ], increasing the acidity while limiting the kombucha's ] content. The number of bacteria and yeasts that were found to produce acetic acid increased for the first four days of fermentation, decreasing thereafter. Sucrose gets broken down into fructose and glucose, and the bacteria and yeast convert the glucose and fructose into ] and acetic acid, respectively.<ref name= "Sreermalu2000"/> ''G. xylinum'' is responsible for most or all of the physical structure of a kombucha mother, and has been shown to produce microbial ],<ref name= "Nguyen2008">{{cite journal |last1= Nguyen |first1= VT |last2= Flanagan |first2= B |last3= Gidley |first3= MJ |last4= Dykes |first4= GA |year= 2008 |title= Characterization of cellulose production by a gluconacetobacter xylinus strain from kombucha |journal= Current Microbiology |volume= 57 |issue= 5 |pages= 449–53 |pmid= 18704575 |doi= 10.1007/s00284-008-9228-3}}</ref> likely due to selection over time for firmer and more robust cultures by brewers. | |||

| The first known use in the English language of the word to describe "a gelatinous mass of symbiotic bacteria (as ''Acetobacter xylinum'') and yeasts (as of the genera ''Brettanomyces'' and ''Saccharomyces'') grown to produce a fermented beverage held to confer health benefits" was in 1944.<ref name="Definition of KOMBUCHA"/> | |||

| Along with multiple species of yeast and bacteria, Kombucha contains organic acids, active ]s, ]s, and ] they produce. The exact quantities of these items vary between samples, but may contain: acetic acid, ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name=Teoh>{{cite journal |last1= Teoh |first1= AL |last2= Heard |first2= G |last3= Cox |first3= J |year= 2004 |title= Yeast ecology of kombucha fermentation |journal= International Journal of Food Microbiology |volume= 95 |issue= 2 |pages= 119–26 |pmid= 15282124|doi= 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1= Dufresne |first1= C |last2= Farnworth |first2= E |year= 2000 |title= Tea, kombucha, and health: A review |journal= Food Research International |volume= 33 |issue= 6 |pages= 409 |doi= 10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1= Velicanski |first1= A |last2= Cvetkovic |first2= D |last3= Markov |first3= S |last4= Tumbas |first4= V |last5= Savatovic |first5= S |displayauthors= 4 |year= 2007 |title= Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of lemon balm Kombucha |journal= Acta Periodica Technologica |issue= 38 |pages= 165–72|doi= 10.2298/APT0738165V}}</ref> Kombucha has also been found to contain about 1.51 mg/mL of ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1= Bauer-Petrovska |first1= B |first2= L |last2= Petrushevska-Tozi |year= 2000 |title= Mineral and water soluble vitamin content in the kombucha drink |journal= International Journal of Food Science & Technology |volume= 35 |issue= 2 |pages= 201–5 |doi= 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2000.00342.x}}</ref> | |||

| ==Composition and properties== | |||

| As a result of kombucha's high acidic properties, caution must be exercised during home preparation to prevent contamination and the leaching of potentially toxic levels of lead associated with fermentation in ceramic containers.<ref name=Jayabalan/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] used for brewing kombucha]] | |||

| ===Biological=== | |||

| According to the American ], many kombucha products contain more than 0.5% ], but some contain less.<ref name=ttb>{{cite web |url= http://www.ttb.gov/pdf/kombucha.pdf |title= Kombucha FAQs |publisher= ] |accessdate= August 2013}}</ref> | |||

| A kombucha culture is a ] (SCOBY), similar to ], containing one or more species each of bacteria and yeasts, which form a ]<ref name=Blanc>{{cite journal|last1=Blanc|first1=Phillipe J|title=Characterization of the tea fungus metabolites|journal=Biotechnology Letters|date=February 1996|volume=18|issue=2|pages=139–142|doi=10.1007/BF00128667|s2cid=34822312}}</ref> known as a "mother".<ref name=Jayabalan>{{cite journal|last1=Jayabalan|first1=Rasu|title=A Review on Kombucha Tea—Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus|journal=Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety|date=21 June 2014|volume=13|issue=4|pages=538–550|doi=10.1111/1541-4337.12073|pmid=33412713|s2cid=62789621 |doi-access=}}</ref> There is a broad spectrum of yeast species spanning several genera reported to be present in kombucha culture including species of ''Zygosaccharomyces'', ''Candida, Kloeckera/Hanseniaspora'', ''Torulaspora'', ''Pichia'', ''Brettanomyces/Dekkera'', ''Saccharomyces'', ''Lachancea'', ''Saccharomycoides'', ''Schizosaccharomyces'', ''Kluyveromyces, Starmera, Eremothecium, Merimbla, Sugiyamaella.''<ref name="Villarreal-Soto 2018 580–588">{{Cite journal|last1=Villarreal-Soto|first1=Silvia Alejandra|last2=Beaufort|first2=Sandra|last3=Bouajila|first3=Jalloul|last4=Souchard|first4=Jean-Pierre|last5=Taillandier|first5=Patricia|date=2018|title=Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review|journal=Journal of Food Science|language=en|volume=83|issue=3|pages=580–588|doi=10.1111/1750-3841.14068|pmid=29508944|issn=1750-3841|url=http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/21134/1/VillarrealSoto_21134.pdf|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ombucha.co.uk/faq/|title=Faq Archive - OMbucha Kombucha {{!}} Hand Brewed With Loving Care|language=en-GB|access-date=31 July 2019|archive-date=31 July 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190731160738/https://www.ombucha.co.uk/faq/|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last1=Chakravorty |first1=Somnath |last2=Bhattacharya |first2=Semantee |last3=Chatzinotas |first3=Antonis |last4=Chakraborty |first4=Writachit |last5=Bhattacharya |first5=Debanjana |last6=Gachhui |first6=Ratan |date=2 March 2016 |title=Kombucha tea fermentation: Microbial and biochemical dynamics |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168160515301951 |journal=International Journal of Food Microbiology |language=en |volume=220 |pages=63–72 |doi=10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.12.015 |pmid=26796581 |issn=0168-1605}}</ref> | |||

| The bacterial component of kombucha comprises several species, almost always including the ] '']'' (formerly ''Gluconacetobacter xylinus''), which ferments alcohols produced by the yeasts into ] and other acids, increasing the acidity and limiting ] content.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Fermentation and metabolic characteristics of Gluconacetobacter oboediens for different carbon sources|journal=Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology|volume=87|issue=1|pages=127–136|doi=10.1007/s00253-010-2474-x|pmid=20191270|year=2010|last1=Sarkar|first1=Dayanidhi|last2=Yabusaki|first2=Masahiro|last3=Hasebe|first3=Yuta|last4=Ho|first4=Pei Yee|last5=Kohmoto|first5=Shuji|last6=Kaga|first6=Takayuki|last7=Shimizu|first7=Kazuyuki|s2cid=11657067}}</ref>{{citation needed|date=July 2015}} The population of bacteria and yeasts found to produce acetic acid has been reported to increase for the first 4 days of fermentation, decreasing thereafter.<ref>Kombucha Fermentation and Its Antimicrobial Activity | |||

| The acidity and mild alcoholic element of kombucha resists contamination by most airborne molds or bacterial spores. A study showed that kombucha inhibits growth of harmful microorganisms such as E. coli, Sal. enteritidis, Sal. typhimurium, and Sh. sonnei.<ref name= "Sreermalu2000"/> As a result, kombucha is relatively easy to maintain as a culture outside of sterile conditions. The bacteria and yeasts in kombucha promoted microbial growth for the first six days of fermentation; after that, they steadily declined. Kombucha retained its antimicrobial capability even after being heated, and at a pH of 7. While the beverage inhibited growth of certain bacteria, it had no effect on the yeasts. The study also found that large proteins and ] such as ] also contributed to the antimicrobial properties of kombucha.<ref name= "Sreermalu2000"/> | |||

| Guttapadu Sreeramulu, Yang Zhu,* and Wieger Knol | |||

| Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2000 48 (6), 2589–2594 | |||

| {{doi|10.1021/jf991333m}}</ref> ''K. xylinus'' produces ], and is reportedly responsible for most or all of the physical structure of the "mother", which may have been selectively encouraged over time for firmer (denser) and more robust cultures by brewers.<ref name="Nguyen2008">{{cite journal |last1= Nguyen |first1= VT |last2= Flanagan |first2= B |last3= Gidley |first3= MJ |last4= Dykes |first4= GA |year= 2008 |title= Characterization of cellulose production by a gluconacetobacter xylinus strain from kombucha |journal= Current Microbiology |volume= 57 |issue= 5 |pages= 449–53 |doi= 10.1007/s00284-008-9228-3|pmid= 18704575|s2cid= 1414305 }}</ref>{{primary source inline|date=July 2015}} The highest diversity of Kombucha bacteria was found to be on the 7th day of fermentation with the diversity being less in the SCOBY. Acetobacteraceae dominate 88 percent of the bacterial community of the SCOBY.<ref name=":2" /> The acetic acid bacteria in kombucha are ], meaning that they require oxygen for their growth and activity.<ref name="Villarreal-Soto 2018 580–588"/> Hence, the bacteria initially migrate and assemble at the air interface, followed by the excretion of bacterial cellulose after about 2 days.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bertsch |first1=Pascal |last2=Etter |first2=Danai |last3=Fischer |first3=Peter |title=Transient in situ measurement of kombucha biofilm growth and mechanical properties |journal=Food & Function |date=2021 |volume=12 |issue=9 |pages=4015–4020 |doi=10.1039/D1FO00630D |pmid=33978026 |doi-access=free |hdl=20.500.11850/485857 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| The mixed, presumably ] culture has been further described as being lichenous, in accord with the reported presence of the known lichenous natural product ], though as of 2015, no report appears indicating the standard cyanobacterial species of ]s in association with kombucha fungal components.<ref name=LiverToxUsnic/> | |||

| Kombucha tea has antioxidant properties, and has been called a ].<ref name=micro>{{cite journal |last1=Jayabalan |first1=Rasu |last2=Malbaša |first2=Radomir V. |last3=Lončar |first3=Eva S. |last4=Vitas |first4=Jasmina S. |last5=Sathishkumar |first5=Muthuswamy |title=A Review on Kombucha Tea–Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus |journal=] |volume=13 |issue=4 |year=2014 |pages=538–550 |issn=15414337 |doi=10.1111/1541-4337.12073 |quote=There has been no evidence published to date on the biological activities of kombucha in human trials.}}</ref> | |||

| ===Chemical composition=== | |||

| Kombucha culture can also be used to make ], for example London based fashion designer ] is experimenting with creating jackets and shoes.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Suzanne Lee: Grow your own clothes|url=http://www.ted.com/talks/suzanne_lee_grow_your_own_clothes.html|publisher=]|date=March 2011}}</ref> | |||

| Kombucha is made by adding the kombucha culture into a broth of sugared tea.<ref name=Jayabalan/> The sugar serves as a nutrient for the SCOBY that allows for bacterial growth in the tea.{{citation needed|date=April 2024}} Sucrose is converted, biochemically, into fructose and glucose, and these into ] and acetic acid.<ref name= "Sreermalu2000"/> In addition, kombucha contains ]s and ]s, ]s, and various other ]s which vary between preparations.{{citation needed|date=April 2024}} | |||

| Other specific components include ] (see below), ], ], ], and ] (a hepatotoxin, see above).<ref name=Teoh>{{cite journal |last1= Teoh |first1= AL |last2= Heard |first2= G |last3= Cox |first3= J |year= 2004 |title= Yeast ecology of kombucha fermentation |journal= International Journal of Food Microbiology |volume= 95 |issue= 2 |pages= 119–26 |pmid= 15282124|doi= 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1= Dufresne |first1= C |last2= Farnworth |first2= E |year= 2000 |title= Tea, kombucha, and health: A review |journal= Food Research International |volume= 33 |issue= 6 |pages= 409–421 |doi= 10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1= Velicanski |first1= A |last2= Cvetkovic |first2= D |last3= Markov |first3= S |last4= Tumbas |first4= V |last5= Savatovic |first5= S |display-authors= 4 |year= 2007 |title= Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of lemon balm Kombucha |journal= Acta Periodica Technologica |issue= 38 |pages= 165–72|doi= 10.2298/APT0738165V|doi-access= free }}</ref> | |||

| == Health effects== | |||

| There have not been any human trials conducted to confirm any curative claims associated with the consumption of kombucha tea.<ref name=Jayabalan>{{cite journal |first1= R |last1= Jayabalan |first2= RV |last2= Malbaša |first3= ES |last3= Lončar |first4= JS |last4= Vitas |first5= M |last5= Sathishkumar |date= July 2014 |title= A Review on Kombucha Tea — Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus |journal= ] |volume= 13 |issue= 4 |pages= 538–50 |doi= 10.1111/1541-4337.12073 | quote="a source of pharmacologically active molecules, an important member of the antioxidant food group, and a functional food with potential beneficial health properties."}}</ref> | |||

| The alcohol content of kombucha is usually less than 0.5%, but increases with extended fermentation times.<ref name=bccdc/> The concentration of alcohol specifically ethanol increases initially but then begins to decrease when acetic acid bacteria use it to produce acetic acid.<ref name=":2" /> Over-fermentation generates high amounts of acids similar to vinegar.<ref name=Jayabalan/> The pH of the drink is typically about 3.5.<ref name=Ernst2003/> | |||

| Some adverse health effects may be due to the acidity of the tea; brewers have been cautioned to avoid over-fermentation.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Nummer|first=Brian A.|title=Kombucha Brewing Under the Food and Drug Administration Model Food Code: Risk Analysis and Processing Guidance|journal=Journal of Environmental Health|volume=76|issue=4|year=2013}}</ref> | |||

| ===Nutritional Content=== | |||

| Kombucha tea is 95% water, contains 4% ]s and several ], such as ], ], ] and ]<ref name="fdc">{{cite web |title=Nutrient content of kombucha tea per 100 ml |url=https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/2710509/nutrients |publisher=FoodData Central, US Department of Agriculture |access-date=2 November 2024 |date=31 October 2024}}</ref> | |||

| == Production == | |||

| ] | |||

| Kombucha can be prepared at home or commercially.<ref name=Jayabalan/> It is made by dissolving sugar in non-chlorinated boiling water. Tea leaves are then steeped in the hot sugar water and discarded. The sweetened tea is cooled and the SCOBY culture is added. The mixture is then poured into a sterilized beaker along with previously fermented kombucha tea to lower the ]. This technique is known as "backslopping".<ref>{{Cite book|last=Redzepi|first=René|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1028603169|title=The Noma guide to fermentation: foundations of flavor|date=2018|others=David Zilber, Evan Sung, Paula Troxler|isbn=978-1-57965-718-5|location=New York, NY|pages=33|oclc=1028603169}}</ref> The container is covered with a paper towel or breathable fabric to prevent insects, such as fruit flies, from contaminating the kombucha. | |||

| The tea is left to ferment for a period of up to 10 to 14 days at room temperature (18 °C to 26 °C). A new "daughter" SCOBY will form on the surface of the tea to the diameter of the container. After fermentation is completed, the SCOBY is removed and stored along with a small amount of the newly fermented tea. The remaining kombucha is strained and bottled for a secondary ferment for a few days or stored at a temperature of 4 °C.<ref name=Jayabalan/> | |||

| ] | |||

| Commercially bottled kombucha became available in the late 1990s.<ref name="Wollan2010">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/25/fashion/25Tea.html?_r=1|title=A Strange Brew May Be a Good Thing |last=Wollan|first=Malia|date=24 March 2010|publisher=NYTimes|access-date=18 June 2015}}</ref> In 2010, elevated alcohol levels were found in many bottled kombucha products, leading retailers including ] to pull the drinks from store shelves temporarily.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.bevnet.com/news/2013/kombucha-crisis-fuels-progress/|title='Kombucha Crisis' Fuels Progress|last=Rothman|first=Max|date=2 May 2013|publisher=BevNET|access-date=18 June 2015}}</ref> In response, kombucha suppliers reformulated their products to have lower alcohol levels.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.bevnet.com/news/2011/the-kombucha-crisis-one-year-later |title=The Kombucha Crisis: One Year Later |last=Crum |first=Hannah |date=23 August 2011 |access-date=27 June 2015 |publisher=BevNET}}</ref> | |||

| By 2014, US sales of bottled kombucha were $400 million, $350 million of which was by Millennium Products, Inc. which sells ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://qz.com/368513/the-american-kombucha-craze-in-one-home-brewed-chart/ |title=The American kombucha craze, in one home-brewed chart |last=Narula |first=Svati Kirsten |website=Quartz |date=26 March 2015 |access-date=27 June 2015}}</ref> In 2014, several companies that make and sell kombucha formed a ], Kombucha Brewers International.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.cnbc.com/2014/08/08/kombucha-cha-ching-a-probiotic-tea-fizzes-up-strong-growth.html |title=Kombucha cha-ching: A probiotic tea fizzes up strong growth |last=Carr |first=Coeli |publisher=] |date=9 August 2014 |access-date=27 June 2015}}</ref> In 2016, ] purchased kombucha maker KeVita for approximately $200 million.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Esterl|first1=Mike|title=Slow Start for Soda Industry's Push to Cut Calories|url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/slow-start-for-soda-industrys-push-to-cut-calories-1479837601|access-date=24 November 2016|newspaper=Wall Street Journal|date=23 November 2016}}</ref> In the US, sales of kombucha and other fermented drinks rose by 37 percent in 2017.<ref name=":0" /> Beer companies like ] and ] produce kombucha by themselves or via subsidiaries.<ref name="boozy" /> | |||

| As of 2021, the drink had some popularity in India's ], partly due to its success in the west.<ref name="TNIE 2021">{{cite web |last1=Roy |first1=Dyuti |title=How Kombucha tea is becoming a beverage of choice for many in Delhi-NCR |url=https://www.newindianexpress.com/lifestyle/food/2021/nov/21/how-kombucha-tea-is-becoming-abeverage-of-choice-for-many-in-delhi-ncr-2386129.html |website=] |access-date=21 April 2022 |date=21 November 2021}}</ref> | |||

| === Hard kombucha === | |||

| Some commercial kombucha producers sell what they call "hard kombucha" with an alcohol content of over 5 percent.<ref name=boozy>{{cite news|last1=Judkis|first1=Maura|date=13 December 2018|title=Is boozy kombucha good for you? It's getting so popular it might not matter.|newspaper=]|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/voraciously/wp/2018/12/13/is-boozy-kombucha-good-for-you-its-getting-so-popular-it-might-not-matter/?noredirect=on|access-date=12 September 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Casey|first1=Michael|date=3 July 2019|title=New in brew: Hard kombucha|publisher=Boulder Weekly|url=https://www.boulderweekly.com/cuisine/drink/new-in-brew-hard-kombucha/|access-date=12 September 2019}}</ref> | |||

| == Health claims == | |||

| ] | |||

| Kombucha is promoted with many claims for health benefits, from alleviating ] to combating cancer.<ref name=piles>{{cite news| newspaper=New York Times |date=16 October 2019 |vauthors=MacKeen D |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/16/style/self-care/kombucha-benefits.html |title=Are There Benefits to Drinking Kombucha?}}</ref> Although people may drink kombucha for such supposed health effects{{Which|date=January 2024}}, there is no ] that it provides any benefit.<ref name=Jayabalan/><ref name=bauer/><ref name="Villarreal-SotoBeaufort2018">{{cite journal|last1=Villarreal-Soto|first1=Silvia Alejandra|last2=Beaufort|first2=Sandra|last3=Bouajila|first3=Jalloul|last4=Souchard|first4=Jean-Pierre|last5=Taillandier|first5=Patricia|year=2018|title=Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review|journal=Journal of Food Science|volume=83|issue=3|pages=580–588|doi=10.1111/1750-3841.14068|issn=0022-1147|pmid=29508944|url=http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/21134/1/VillarrealSoto_21134.pdf|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=kapp>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kapp JM, Sumner W |title=Kombucha: a systematic review of the empirical evidence of human health benefit |journal=Annals of Epidemiology |volume=30 |pages=66–70 |date=February 2019 |pmid=30527803 |doi=10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.11.001 |doi-access=free }}</ref> In a 2003 review, physician ] characterized kombucha as an "extreme example" of an unconventional remedy because of the disparity between implausible, wide-ranging health claims and the potential risks of the product.<ref name=Ernst2003/> It concluded that the proposed, unsubstantiated therapeutic claims did not outweigh known risks, and that kombucha should not be recommended for ], being in a class of "remedies that only seem to benefit those who sell them".<ref name=Ernst2003>{{cite journal|author=Ernst E|title=Kombucha: a systematic review of the clinical evidence|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0020339/|journal=Forschende Komplementärmedizin und Klassische Naturheilkunde|year=2003|volume=10|issue=2|pages=85–87|doi=10.1159/000071667|pmid=12808367|s2cid=42348141}}</ref> | |||

| ===Adverse effects=== | |||

| Reports of ]s related to kombucha consumption are rare, but may be underreported, according to a 2003 review.<ref name=Ernst2003/> The ] said in 2009 that "serious side effects and occasional deaths have been associated with drinking Kombucha tea."<ref name=acs>{{cite book|publisher=]|title=American Cancer Society Complete Guide to Complementary and Alternative Cancer Therapies|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/americancancerso0000unse|chapter-url-access=registration|edition=2nd|year=2009|isbn=9780944235713|location=New York |veditors=Russell J, Rovere A|pages=|chapter=Kombucha tea|quote=Serious side effects and occasional deaths have been associated with drinking Kombucha tea}}</ref> Because kombucha is a commonly homemade fermentation, caution should be taken because pathogenic microorganisms can contaminate the tea during preparation.<ref name=mayo/><ref name="Villarreal-Soto 2018 580–588"/> | |||

| Adverse effects associated with kombucha consumption may include severe ] (liver) and ] (kidney) toxicity as well as ].<ref name=Dasgupta11>{{cite book|title=Effects of Herbal Supplements on Clinical Laboratory Test Results|last=Dasgupta|first=Amitava|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ts9WFyHtODMC|year=2011|pages=24, 108, 112|publisher=Walter de Gruyter|location=Berlin, Germany|isbn=978-3-1102-4561-5}}</ref><ref name=Dasgupta13/><ref name=AbdualmjidSergi13>{{cite journal|title=Hepatotoxic Botanicals—An Evidence-based Systematic Review|journal=Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences |last1=Abdualmjid|first1=Reem J|last2=Sergi|first2=Consolato|year=2013|volume=16|issue=3|pages=376–404|pmid=24021288|doi=10.18433/J36G6X |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Some adverse health effects may arise from the acidity of the tea causing ], and brewers are cautioned to avoid over-fermentation.<ref name="mskcc">{{cite web|url=https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/kombucha|title=Kombucha|date=22 May 2014|publisher=]|access-date=1 June 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Nummer|first=Brian A.|title=Kombucha Brewing Under the Food and Drug Administration Model Food Code: Risk Analysis and Processing Guidance|journal=Journal of Environmental Health|volume=76|issue=4|pages=8–11|date=November 2013|pmid=24341155}}</ref><ref name=bccdc/> Other adverse effects may be a result of bacterial or fungal contamination during the brewing process.<ref name=bccdc/> Some studies have found the ] ] in kombucha, although it is not known whether the cases of liver damage are due to ] or to some other toxin.<ref name=Dasgupta13>{{cite book |title=Accurate Results in the Clinical Laboratory: A Guide to Error Detection and Correction|editor-last1=Dasgupta|editor-first1=Amitava|editor-last2=Sepulveda|editor-first2=Jorge L.|chapter=Effects of herbal remedies on clinical laboratory tests|last=Dasgupta|first=Amitava|pages=78–79|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HEBloh3nxiAC|publisher=Elsevier|location=Amsterdam, NH|date=2013|isbn=978-0-1241-5783-5}}</ref><ref name=LiverToxUsnic>{{cite encyclopedia|title=Drug record, Usnic acid (''Usnea'' species)|encyclopedia=LiverTox|url=https://livertox.nlm.nih.gov//UsnicAcid.htm|date=23 June 2015|access-date=26 July 2017|publisher=National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health|archive-date=2 July 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190702160313/https://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/UsnicAcid.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Drinking kombucha can be harmful for people with preexisting ailments.<ref name=GreenwaltSteinkraus2000>{{cite journal|last1=Greenwalt|first1=C. J.|last2=Steinkraus|first2=K. H.|last3=Ledford|first3=R. A.|title=Kombucha, the Fermented Tea: Microbiology, Composition, and Claimed Health Effects|journal=Journal of Food Protection|volume=63|issue=7|year=2000|pages=976–981|issn=0362-028X|doi=10.4315/0362-028X-63.7.976|pmid=10914673|s2cid=27587313 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Due to its microbial sourcing and possible non-sterile packaging, kombucha is not recommended for people with poor immune function,<ref name=mskcc/> women who are pregnant or nursing, or children under 4 years old:<ref name=bccdc>{{cite report|url=http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Educational%20Materials/EH/FPS/Food/kombucha1.pdf|title=Food Safety Assessment of Kombucha Tea Recipe and Food Safety Plan|publisher=British Columbia (BC) Centre for Disease Control|series=Food Issue, Notes From the Field|date=27 January 2015|access-date=1 July 2015}}</ref> It may compromise ] or stomach acidity in these susceptible populations.<ref name=mskcc/> There are certain drugs that one should not take with kombucha because of the small percentage of alcohol content.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Martini |first1=Nataly |title=Potion or Poison? Kombucha |journal=Journal of Primary Health Care |date=March 2018 |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=93–94 |doi=10.1071/HC15930 |pmid=30068458 |url=http://www.publish.csiro.au/hc/Fulltext/HC15930|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| A 2019 review enumerated numerous potential health risks{{Which|date=January 2024}}, but said "kombucha is not considered harmful if about 4 oz per day is consumed by healthy individuals; potential risks are associated with a low pH brew ] ] from containers, excessive consumption of highly acidic kombucha, or consumption by individuals with pre-existing health conditions."<ref name=kapp/> | |||

| ===Caffeine=== | |||

| Kombucha contains a small amount of ].<ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.hollandandbarrett.com/the-health-hub/food-drink/nutrition/kombucha-benefits/|title=What is Kombucha? Benefits & Side Effects | Holland & Barrett|website=www.hollandandbarrett.com}}</ref><ref name="auto1">{{Cite web|url=https://www.bonappetit.com/story/does-kombucha-have-caffeine|title=So Does Kombucha Have Caffeine or Alcohol in It? How Much?!|date=2 July 2018|website=Bon Appétit}}</ref> | |||

| == Other uses == | |||

| Kombucha culture, when dried, becomes a leather-like textile known as a ] that can be molded onto forms to create seamless clothing.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.popsci.com/meet-woman-who-wants-growing-clothing-lab|title=Meet the Woman Who Wants to Grow Clothing in a Lab|last=Grushkin|first=Daniel|publisher=]|date=17 February 2015|access-date=18 June 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://bkaccelerator.com/biocouture-creates-kombucha-mushroom-fabric-fashion-architecture/|title=BIOCOUTURE Creates Kombucha Mushroom Fabric For Fashion & Architecture|last=Oiljala|first=Leena|date=9 September 2014|access-date=18 June 2015|publisher=]|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150619063637/http://bkaccelerator.com/biocouture-creates-kombucha-mushroom-fabric-fashion-architecture/|archive-date=19 June 2015}}</ref> Using different broth media such as coffee, black tea, and green tea to grow the kombucha culture results in different textile colors, although the textile can also be dyed using other plant-based dyes.<ref name=Hinchliffe>{{cite web|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-09-24/brewing-clothes-queensland-fashion-student-grow-garments-in-jar/5765060|title='Scary and gross': Queensland fashion students grow garments in jars with kombucha|last=Hinchliffe|first=Jessica|publisher=ABCNet.net.au|date=25 September 2014|access-date=18 June 2015}}</ref> Different growth media and dyes also change the textile's feel and texture.<ref name=Hinchliffe/> Additionally the SCOBY itself can be dried and eaten as a sweet or savory snack.<ref>{{Cite web|date=17 June 2015|title=Kombucha Scoby Jerky|url=https://www.fermentingforfoodies.com/kombucha-scoby-jerky/|access-date=23 March 2021|website=Fermenting for Foodies|language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Portal|Drink}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * ], a cannabis-infused drink prepared by steeping various parts of the cannabis plant in hot or cold water | |||

| *] | |||

| * ], a carbonated green tea drink promoted with bogus health claims | |||

| *] | |||

| * ], a fermented drink made from green tea and honey | |||

| * ], a fermented dairy product | |||

| * ], a traditional fermented drink made from bread | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ], an ] of mushrooms in water, made by using ]/] (such as ]) or ]s (such as '']'') | |||

| * ], or "water kefir" | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist| |

{{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Dasgupta A, Sepulveda JL |work=Accurate Results in the Clinical Laboratory: A Guide to Error Detection and Correction |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=HEBloh3nxiAC&pg=PA78 |year=2013 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=978-0-12-415858-0 |pages=78–79 |title=Other Supplements that Cause Liver Damage |quote=the limited evidence currently available raises safety concerns, especally regarding potential hepatotoxicty and the possibility of life-threatening lactic acidosis}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |pmid=14631833 | volume=16 | issue=3 | title=Lead induced oxidative stress: beneficial effects of Kombucha tea | journal=Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES |date=September 2003 | pages=276–82| author1=Dipti | first1=P | last2=Yogesh | first2=B | last3=Kain | first3=A. K. | last4=Pauline | first4=T | last5=Anju | first5=B | last6=Sairam | first6=M | last7=Singh | first7=B | last8=Mongia | first8=S. S. | last9=Kumar | first9=G. I. | last10=Selvamurthy | first10=W }} | |||

| *{{Cite book|last=Frank|first=Günther W. |title=Kombucha: Healthy Beverage and Natural Remedy from the Far East, Its Correct Preparation and Use |year=1995|publisher=Pub. House W. Ennsthaler|location=Steyr|isbn=978-3-85068-337-1}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |pmid=11723720 | volume=14 | issue=3 | title=Studies on toxicity, anti-stress and hepato-protective properties of Kombucha tea | journal=Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES |date=September 2001 | pages=207–13| author1=Pauline | first1=T | last2=Dipti | first2=P | last3=Anju | first3=B | last4=Kavimani | first4=S | last5=Sharma | first5=S. K. | last6=Kain | first6=A. K. | last7=Sarada | first7=S. K. | last8=Sairam | first8=M | last9=Ilavazhagan | first9=G | last10=Devendra | first10=K | last11=Selvamurthy | first11=W }} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Kombucha}} | *{{Commons category-inline|Kombucha}} | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{teas}} | {{teas}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:43, 8 January 2025

Fermented tea beverage This article is about the fermented tea. For the East Asian drink "konbu-cha", made from dried seaweed, see kelp tea. "Tea mushroom" redirects here. For the tea tree mushroom used in Chinese cooking, see Cyclocybe aegerita.

Kombucha tea, including the culture of bacteria and yeast, which is not usually consumed Kombucha tea, including the culture of bacteria and yeast, which is not usually consumed | |

| Type | Flavored cold tea drink with fermentation byproducts |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | China |

| Alcohol by volume | <0.5% (commercial) |

| Proof (US) | <1 (commercial) |

| Color | Cloudy, commonly pale or dark brown and sometimes green |

| Flavor | Fermented, effervescent |

| Ingredients | Tea, sugar, bacteria, yeast |

| Variants | Fruit juices or spices added |

| Related products | Water kefir, kefir, kvass, beer, iced tea |

Kombucha (also tea mushroom, tea fungus, or Manchurian mushroom when referring to the culture; Latin name Medusomyces gisevii) is a fermented, lightly effervescent, sweetened black tea drink. Sometimes the beverage is called kombucha tea to distinguish it from the culture of bacteria and yeast. Juice, spices, fruit or other flavorings are often added.

Kombucha is thought to have originated in China, where the drink is traditional. By the early 20th century it spread to Russia, then other parts of Eastern Europe and Germany. Kombucha is now homebrewed globally, and also bottled and sold commercially. The global kombucha market was worth approximately US$1.7 billion as of 2019.

Kombucha is produced by symbiotic fermentation of sugared tea using a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) commonly called a "mother" or "mushroom". The microbial populations in a SCOBY vary. The yeast component generally includes Saccharomyces cerevisiae, along with other species; the bacterial component almost always includes Gluconacetobacter xylinus to oxidize yeast-produced alcohols to acetic acid (and other acids). Although the SCOBY is commonly called "tea fungus" or "mushroom", it is actually "a symbiotic growth of acetic acid bacteria and osmophilic yeast species in a zoogleal mat [biofilm]". The living bacteria are said to be probiotic, one of the reasons for the popularity of the drink.

Numerous health benefits have been claimed to correlate with drinking kombucha; there is little evidence to support any of these claims. The beverage has caused rare serious adverse effects, possibly arising from contamination during home preparation. It is not recommended for therapeutic purposes.

History

Kombucha likely originated in the Bohai Sea region of China. It spread to Russia before reaching Europe and gained popularity in the United States in the early 21st century. With an alcohol content under 0.5%, it is not federally regulated in the U.S.

Prior to 2015, some commercially available kombucha brands were found to contain alcohol content exceeding this threshold, sparking the development of new testing methods. With rising popularity in developed countries in the early 21st century, kombucha sales increased after it was marketed as an alternative to beer and other alcoholic drinks in restaurants and pubs.

According to the market research firm Grand View Research, kombucha had a global market size of US$1.67 billion, as of 2019 and this is expected to grow to US$9.7 billion by 2030.

Etymology and terminology

The etymology of kombucha is uncertain, but it is believed to be a misapplied loanword from Japanese. English speakers may have confused the Japanese word konbucha (which refers to fermented tea) with kōcha kinoko (紅茶キノコ, 'black tea mushroom'), popularized around 1975.

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Kombucha" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2025) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Merriam-Webster's Dictionary suggests kombucha in English arose from misapplication of Japanese words like konbucha, kobucha 'tea made from kelp', konbu, from kobu 'kelp', + cha 'tea'. The American Heritage Dictionary notes the term might have originated from the belief that the gelatinous film of kombucha resembled seaweed.

In Japanese, the term konbu-cha (昆布茶, 'kelp tea') refers to a kelp tea made with powdered konbu (an edible kelp from the family Laminariaceae) and is a completely different beverage from the fermented tea usually associated with kombucha elsewhere in the world.

The first known use in the English language of the word to describe "a gelatinous mass of symbiotic bacteria (as Acetobacter xylinum) and yeasts (as of the genera Brettanomyces and Saccharomyces) grown to produce a fermented beverage held to confer health benefits" was in 1944.

Composition and properties

Biological

A kombucha culture is a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY), similar to mother of vinegar, containing one or more species each of bacteria and yeasts, which form a zoogleal mat known as a "mother". There is a broad spectrum of yeast species spanning several genera reported to be present in kombucha culture including species of Zygosaccharomyces, Candida, Kloeckera/Hanseniaspora, Torulaspora, Pichia, Brettanomyces/Dekkera, Saccharomyces, Lachancea, Saccharomycoides, Schizosaccharomyces, Kluyveromyces, Starmera, Eremothecium, Merimbla, Sugiyamaella.

The bacterial component of kombucha comprises several species, almost always including the acetic acid bacteria Komagataeibacter xylinus (formerly Gluconacetobacter xylinus), which ferments alcohols produced by the yeasts into acetic and other acids, increasing the acidity and limiting ethanol content. The population of bacteria and yeasts found to produce acetic acid has been reported to increase for the first 4 days of fermentation, decreasing thereafter. K. xylinus produces bacterial cellulose, and is reportedly responsible for most or all of the physical structure of the "mother", which may have been selectively encouraged over time for firmer (denser) and more robust cultures by brewers. The highest diversity of Kombucha bacteria was found to be on the 7th day of fermentation with the diversity being less in the SCOBY. Acetobacteraceae dominate 88 percent of the bacterial community of the SCOBY. The acetic acid bacteria in kombucha are aerobic, meaning that they require oxygen for their growth and activity. Hence, the bacteria initially migrate and assemble at the air interface, followed by the excretion of bacterial cellulose after about 2 days.

The mixed, presumably mutualistic culture has been further described as being lichenous, in accord with the reported presence of the known lichenous natural product usnic acid, though as of 2015, no report appears indicating the standard cyanobacterial species of lichens in association with kombucha fungal components.

Chemical composition

Kombucha is made by adding the kombucha culture into a broth of sugared tea. The sugar serves as a nutrient for the SCOBY that allows for bacterial growth in the tea. Sucrose is converted, biochemically, into fructose and glucose, and these into gluconic acid and acetic acid. In addition, kombucha contains enzymes and amino acids, polyphenols, and various other organic acids which vary between preparations.

Other specific components include ethanol (see below), glucuronic acid, glycerol, lactic acid, and usnic acid (a hepatotoxin, see above).

The alcohol content of kombucha is usually less than 0.5%, but increases with extended fermentation times. The concentration of alcohol specifically ethanol increases initially but then begins to decrease when acetic acid bacteria use it to produce acetic acid. Over-fermentation generates high amounts of acids similar to vinegar. The pH of the drink is typically about 3.5.

Nutritional Content

Kombucha tea is 95% water, contains 4% carbohydrates and several B vitamins, such as Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin and Vitamin B-6

Production

Kombucha can be prepared at home or commercially. It is made by dissolving sugar in non-chlorinated boiling water. Tea leaves are then steeped in the hot sugar water and discarded. The sweetened tea is cooled and the SCOBY culture is added. The mixture is then poured into a sterilized beaker along with previously fermented kombucha tea to lower the pH. This technique is known as "backslopping". The container is covered with a paper towel or breathable fabric to prevent insects, such as fruit flies, from contaminating the kombucha.

The tea is left to ferment for a period of up to 10 to 14 days at room temperature (18 °C to 26 °C). A new "daughter" SCOBY will form on the surface of the tea to the diameter of the container. After fermentation is completed, the SCOBY is removed and stored along with a small amount of the newly fermented tea. The remaining kombucha is strained and bottled for a secondary ferment for a few days or stored at a temperature of 4 °C.

Commercially bottled kombucha became available in the late 1990s. In 2010, elevated alcohol levels were found in many bottled kombucha products, leading retailers including Whole Foods to pull the drinks from store shelves temporarily. In response, kombucha suppliers reformulated their products to have lower alcohol levels.

By 2014, US sales of bottled kombucha were $400 million, $350 million of which was by Millennium Products, Inc. which sells GT's Kombucha. In 2014, several companies that make and sell kombucha formed a trade organization, Kombucha Brewers International. In 2016, PepsiCo purchased kombucha maker KeVita for approximately $200 million. In the US, sales of kombucha and other fermented drinks rose by 37 percent in 2017. Beer companies like Full Sail Brewing Company and Molson Coors Beverage Company produce kombucha by themselves or via subsidiaries.

As of 2021, the drink had some popularity in India's National Capital Region, partly due to its success in the west.

Hard kombucha

Some commercial kombucha producers sell what they call "hard kombucha" with an alcohol content of over 5 percent.

Health claims

Kombucha is promoted with many claims for health benefits, from alleviating hemorrhoids to combating cancer. Although people may drink kombucha for such supposed health effects, there is no clinical proof that it provides any benefit. In a 2003 review, physician Edzard Ernst characterized kombucha as an "extreme example" of an unconventional remedy because of the disparity between implausible, wide-ranging health claims and the potential risks of the product. It concluded that the proposed, unsubstantiated therapeutic claims did not outweigh known risks, and that kombucha should not be recommended for therapeutic use, being in a class of "remedies that only seem to benefit those who sell them".

Adverse effects

Reports of adverse effects related to kombucha consumption are rare, but may be underreported, according to a 2003 review. The American Cancer Society said in 2009 that "serious side effects and occasional deaths have been associated with drinking Kombucha tea." Because kombucha is a commonly homemade fermentation, caution should be taken because pathogenic microorganisms can contaminate the tea during preparation.

Adverse effects associated with kombucha consumption may include severe hepatic (liver) and renal (kidney) toxicity as well as metabolic acidosis.

Some adverse health effects may arise from the acidity of the tea causing acidosis, and brewers are cautioned to avoid over-fermentation. Other adverse effects may be a result of bacterial or fungal contamination during the brewing process. Some studies have found the hepatotoxin usnic acid in kombucha, although it is not known whether the cases of liver damage are due to usnic acid or to some other toxin.

Drinking kombucha can be harmful for people with preexisting ailments. Due to its microbial sourcing and possible non-sterile packaging, kombucha is not recommended for people with poor immune function, women who are pregnant or nursing, or children under 4 years old: It may compromise immune responses or stomach acidity in these susceptible populations. There are certain drugs that one should not take with kombucha because of the small percentage of alcohol content.

A 2019 review enumerated numerous potential health risks, but said "kombucha is not considered harmful if about 4 oz per day is consumed by healthy individuals; potential risks are associated with a low pH brew leaching heavy metals from containers, excessive consumption of highly acidic kombucha, or consumption by individuals with pre-existing health conditions."

Caffeine

Kombucha contains a small amount of caffeine.

Other uses

Kombucha culture, when dried, becomes a leather-like textile known as a microbial cellulose that can be molded onto forms to create seamless clothing. Using different broth media such as coffee, black tea, and green tea to grow the kombucha culture results in different textile colors, although the textile can also be dyed using other plant-based dyes. Different growth media and dyes also change the textile's feel and texture. Additionally the SCOBY itself can be dried and eaten as a sweet or savory snack.

See also

- Cannabis tea, a cannabis-infused drink prepared by steeping various parts of the cannabis plant in hot or cold water

- Enviga, a carbonated green tea drink promoted with bogus health claims

- Jun, a fermented drink made from green tea and honey

- Kefir, a fermented dairy product

- Kvass, a traditional fermented drink made from bread

- List of unproven or disproven cancer treatments

- Mushroom tea, an infusion of mushrooms in water, made by using edible/medicinal mushrooms (such as lingzhi mushroom) or psychedelic mushrooms (such as Psilocybe cubensis)

- Tibicos, or "water kefir"

References

- ^ Jayabalan, Rasu (21 June 2014). "A Review on Kombucha Tea—Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 13 (4): 538–550. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12073. PMID 33412713. S2CID 62789621.

- "A mug of kombucha for your health?". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- "kombucha | Description, History, & Nutrition". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Alex., LaGory (2016). The Big Book of Kombucha. Storey Publishing, LLC. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-61212-435-3. OCLC 1051088525.

- Troitino, Christina. "Kombucha 101: Demystifying The Past, Present And Future Of The Fermented Tea Drink". Forbes. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ "Kombucha Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Flavor (Original, Flavored), By Distribution Channel (Supermarkets, Health Stores, Online Stores), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2020 – 2027". Grandview Research. February 2020.

- Jonas, Rainer; Farah, Luiz F. (1998). "Production and application of microbial cellulose". Polymer Degradation and Stability. 59 (1–3): 101–106. doi:10.1016/s0141-3910(97)00197-3.

- ^ Bauer, Brent (8 July 2017). "What is kombucha tea? Does it have any health benefits?". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- Wollan, Malia (24 March 2010). "Kombucha Tea Attracts a Following and Doubters". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Ernst E (2003). "Kombucha: a systematic review of the clinical evidence". Forschende Komplementärmedizin und Klassische Naturheilkunde. 10 (2): 85–87. doi:10.1159/000071667. PMID 12808367. S2CID 42348141.

- Kapp, J. M.; Sumner, W. (2019). "Kombucha: a systematic review of the empirical evidence of human health benefit". Annals of Epidemiology. 30. Elsevier: 66–70. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.11.001. PMID 30527803. S2CID 54472564.

- ^ "Kombucha". Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Russell J, Rovere A, eds. (2009). "Kombucha tea". American Cancer Society Complete Guide to Complementary and Alternative Cancer Therapies (2nd ed.). New York: American Cancer Society. pp. 629–633. ISBN 9780944235713.

Serious side effects and occasional deaths have been associated with drinking Kombucha tea

- ^ Bauer, Brent. "What is kombucha tea? Does it have any health benefits?". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Sreeramulu, G; Zhu, Y; Knol, W (2000). "Kombucha fermentation and its antimicrobial activity" (PDF). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48 (6): 2589–2594. Bibcode:2000JAFC...48.2589S. doi:10.1021/jf991333m. PMID 10888589.

It originated in northeast China (Manchuria) and later spread to Russia and the rest of the world.

- Hamblin, James (8 December 2016). "Is Fermented Tea Making People Feel Enlightened Because of ... Alcohol?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- Sandor Ellix Katz (2012). The Art of Fermentation: An In-depth Exploration of Essential Concepts and Processes from Around the World. Chelsea Green Publishing. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-1-60358-286-5.

- "Hard Kombucha Is Super Trendy, but Is It Good for You? We Asked Nutritionists". Health.com.

- "Hard Kombucha Is the New Trendy Beverage You Should Try". Better Homes & Gardens.

- Wyatt, Kristen (12 October 2015). "As kombucha sales boom, makers ask feds for new alcohol test". Associated Press. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Fleming, Amy (11 October 2018). "Kombucha: can the fermented drink compete with beer at the bar?". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Algeo, John; Algeo, Adele (1997). "Among the New Words". American Speech. 72 (2): 183–97. doi:10.2307/455789. JSTOR 455789.

- Wong, Crystal (12 July 2007). "U.S. 'kombucha': Smelly and No Kelp". Japan Times. Retrieved 14 June 2015..

- "紅茶キノコ(こうちゃキノコ)とは? 意味や使い方" [What is "red tea mushroom"? – meaning and usage]. Kotobank (in Japanese). Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Definition of KOMBUCHA". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Kombucha". American Heritage Dictionary (Fifth ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- How kombucha went from seaweed tea in Japan to a hit in North America

- Blanc, Phillipe J (February 1996). "Characterization of the tea fungus metabolites". Biotechnology Letters. 18 (2): 139–142. doi:10.1007/BF00128667. S2CID 34822312.

- ^ Villarreal-Soto, Silvia Alejandra; Beaufort, Sandra; Bouajila, Jalloul; Souchard, Jean-Pierre; Taillandier, Patricia (2018). "Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review" (PDF). Journal of Food Science. 83 (3): 580–588. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.14068. ISSN 1750-3841. PMID 29508944.

- "Faq Archive - OMbucha Kombucha | Hand Brewed With Loving Care". Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Chakravorty, Somnath; Bhattacharya, Semantee; Chatzinotas, Antonis; Chakraborty, Writachit; Bhattacharya, Debanjana; Gachhui, Ratan (2 March 2016). "Kombucha tea fermentation: Microbial and biochemical dynamics". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 220: 63–72. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.12.015. ISSN 0168-1605. PMID 26796581.

- Sarkar, Dayanidhi; Yabusaki, Masahiro; Hasebe, Yuta; Ho, Pei Yee; Kohmoto, Shuji; Kaga, Takayuki; Shimizu, Kazuyuki (2010). "Fermentation and metabolic characteristics of Gluconacetobacter oboediens for different carbon sources". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 87 (1): 127–136. doi:10.1007/s00253-010-2474-x. PMID 20191270. S2CID 11657067.

- Kombucha Fermentation and Its Antimicrobial Activity Guttapadu Sreeramulu, Yang Zhu,* and Wieger Knol Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2000 48 (6), 2589–2594 doi:10.1021/jf991333m

- Nguyen, VT; Flanagan, B; Gidley, MJ; Dykes, GA (2008). "Characterization of cellulose production by a gluconacetobacter xylinus strain from kombucha". Current Microbiology. 57 (5): 449–53. doi:10.1007/s00284-008-9228-3. PMID 18704575. S2CID 1414305.

- Bertsch, Pascal; Etter, Danai; Fischer, Peter (2021). "Transient in situ measurement of kombucha biofilm growth and mechanical properties". Food & Function. 12 (9): 4015–4020. doi:10.1039/D1FO00630D. hdl:20.500.11850/485857. PMID 33978026.

- ^ "Drug record, Usnic acid (Usnea species)". LiverTox. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. 23 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Teoh, AL; Heard, G; Cox, J (2004). "Yeast ecology of kombucha fermentation". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 95 (2): 119–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020. PMID 15282124.

- Dufresne, C; Farnworth, E (2000). "Tea, kombucha, and health: A review". Food Research International. 33 (6): 409–421. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3.

- Velicanski, A; Cvetkovic, D; Markov, S; Tumbas, V; et al. (2007). "Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of lemon balm Kombucha". Acta Periodica Technologica (38): 165–72. doi:10.2298/APT0738165V.

- ^ Food Safety Assessment of Kombucha Tea Recipe and Food Safety Plan (PDF) (Report). Food Issue, Notes From the Field. British Columbia (BC) Centre for Disease Control. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "Nutrient content of kombucha tea per 100 ml". FoodData Central, US Department of Agriculture. 31 October 2024. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- Redzepi, René (2018). The Noma guide to fermentation: foundations of flavor. David Zilber, Evan Sung, Paula Troxler. New York, NY. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-57965-718-5. OCLC 1028603169.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wollan, Malia (24 March 2010). "A Strange Brew May Be a Good Thing". NYTimes. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Rothman, Max (2 May 2013). "'Kombucha Crisis' Fuels Progress". BevNET. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Crum, Hannah (23 August 2011). "The Kombucha Crisis: One Year Later". BevNET. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Narula, Svati Kirsten (26 March 2015). "The American kombucha craze, in one home-brewed chart". Quartz. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Carr, Coeli (9 August 2014). "Kombucha cha-ching: A probiotic tea fizzes up strong growth". CNBC. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Esterl, Mike (23 November 2016). "Slow Start for Soda Industry's Push to Cut Calories". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ Judkis, Maura (13 December 2018). "Is boozy kombucha good for you? It's getting so popular it might not matter". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Roy, Dyuti (21 November 2021). "How Kombucha tea is becoming a beverage of choice for many in Delhi-NCR". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Casey, Michael (3 July 2019). "New in brew: Hard kombucha". Boulder Weekly. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- MacKeen D (16 October 2019). "Are There Benefits to Drinking Kombucha?". New York Times.

- Villarreal-Soto, Silvia Alejandra; Beaufort, Sandra; Bouajila, Jalloul; Souchard, Jean-Pierre; Taillandier, Patricia (2018). "Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review" (PDF). Journal of Food Science. 83 (3): 580–588. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.14068. ISSN 0022-1147. PMID 29508944.

- ^ Kapp JM, Sumner W (February 2019). "Kombucha: a systematic review of the empirical evidence of human health benefit". Annals of Epidemiology. 30: 66–70. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.11.001. PMID 30527803.

- Dasgupta, Amitava (2011). Effects of Herbal Supplements on Clinical Laboratory Test Results. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 24, 108, 112. ISBN 978-3-1102-4561-5.

- ^ Dasgupta, Amitava (2013). "Effects of herbal remedies on clinical laboratory tests". In Dasgupta, Amitava; Sepulveda, Jorge L. (eds.). Accurate Results in the Clinical Laboratory: A Guide to Error Detection and Correction. Amsterdam, NH: Elsevier. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-1241-5783-5.

- Abdualmjid, Reem J; Sergi, Consolato (2013). "Hepatotoxic Botanicals—An Evidence-based Systematic Review". Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 16 (3): 376–404. doi:10.18433/J36G6X. PMID 24021288.

- Nummer, Brian A. (November 2013). "Kombucha Brewing Under the Food and Drug Administration Model Food Code: Risk Analysis and Processing Guidance". Journal of Environmental Health. 76 (4): 8–11. PMID 24341155.

- Greenwalt, C. J.; Steinkraus, K. H.; Ledford, R. A. (2000). "Kombucha, the Fermented Tea: Microbiology, Composition, and Claimed Health Effects". Journal of Food Protection. 63 (7): 976–981. doi:10.4315/0362-028X-63.7.976. ISSN 0362-028X. PMID 10914673. S2CID 27587313.

- Martini, Nataly (March 2018). "Potion or Poison? Kombucha". Journal of Primary Health Care. 10 (1): 93–94. doi:10.1071/HC15930. PMID 30068458.

- "What is Kombucha? Benefits & Side Effects | Holland & Barrett". www.hollandandbarrett.com.

- "So Does Kombucha Have Caffeine or Alcohol in It? How Much?!". Bon Appétit. 2 July 2018.

- Grushkin, Daniel (17 February 2015). "Meet the Woman Who Wants to Grow Clothing in a Lab". Popular Science. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Oiljala, Leena (9 September 2014). "BIOCOUTURE Creates Kombucha Mushroom Fabric For Fashion & Architecture". Pratt Institute. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Hinchliffe, Jessica (25 September 2014). "'Scary and gross': Queensland fashion students grow garments in jars with kombucha". ABCNet.net.au. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Kombucha Scoby Jerky". Fermenting for Foodies. 17 June 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

External links

Media related to Kombucha at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kombucha at Wikimedia Commons

| Tea (Camellia sinensis) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common varieties |

| ||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||

| Culture |

| ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

| Production and distribution |

| ||||||||||||||

| Preparation | |||||||||||||||

| Health | |||||||||||||||

| Tea-based drinks | |||||||||||||||

| See also |

| ||||||||||||||