| Revision as of 22:48, 19 September 2016 edit216.115.122.132 (talk) Deleting long-time unsourced section, see talk page← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:04, 30 November 2024 edit undo2601:182:cd01:1890:38d2:1b0b:bc77:14df (talk)No edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App section source | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Exonym used to describe Indigenous people from the circumpolar region}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | {{Other uses}} | ||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| ] of Eskimo peoples, showing the ] (Yupik, Siberian Yupik) and ] (Iñupiat, Inuvialuit, Nunavut, Nunavik, Nunatsiavut, Kalaallit)]] | |||

| | group = Eskimo | |||

| {{externalvideo|video1=}} | |||

| | image = | |||

| The '''Eskimo''' are the ] who have traditionally inhabited the northern circumpolar region from eastern ] (Russia), across ] (United States), Canada, and ].<ref name=anlc>Kaplan, Lawrence. ''Alaskan Native Language Center, UFA.'' Retrieved 14 Feb 2015.</ref><ref> ''Oxford Dictionaries''. Retrieved 27 Jan 2014.</ref><ref> ''The Free Dictionary.'' Retrieved 27 Jan 2014.</ref> | |||

| | caption = | |||

| | population = 194,447{{when|date=October 2024}} | |||

| The two main peoples known as "Eskimo" are: the ] of Canada, Northern Alaska (sub-group "]"), and Greenland; and the ] of eastern Siberia and Alaska. The Yupik comprise speakers of four distinct Yupik languages: one used in the ] and the others among people of Western Alaska, ] and along the ] coast. A third northern group, the ], is closely related to the Eskimo. They share a relatively recent common ancestor, and a language group (]). | |||

| | popplace = Russia<br />- Chukotka Autonomous Okrug<br />- Sakha (Yakutia)<br /> <hr /> United States<br />- Alaska<br /><hr />Canada<br />- Newfoundland and Labrador<br />- Northwest Territories <br />- Nunavut<br />- Quebec<br />- Yukon (formerly)<br /> <hr /> Greenland | |||

| | langs = | |||

| ]:<br>], ] (]), and ]<br> | |||

| Non-native European languages:<br>], ], ], and ] | |||

| | rels = ], ], ], ]<br />] (], ], ], ], ]) | |||

| | related = ] | |||

| | native_name = | |||

| | native_name_lang = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''''Eskimo''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɛ|s|k|ɪ|m|oʊ}}) is an ] that refers to two closely related ]: ] (including the Alaska Native ], the Canadian Inuit, and the ]) and the ] (or ]) of eastern Siberia and Alaska. A related third group, the ], who inhabit the ], are generally excluded from the definition of ''Eskimo''. The three groups share a relatively recent common ancestor, and speak related languages belonging to the family of ]. | |||

| Since the late 20th century, numerous indigenous people have viewed the use of the term "Eskimo" as offensive, because it has been used by people who discriminated against them or their forebears.<ref> ''Ethnologue''. Retrieved 8 Dec 2013.</ref><ref name=n580>Nuttall 580</ref> In its linguistic origins,<ref name="anlc" /> the word Eskimo comes from Montagnais 'ayas̆kimew' meaning "a person who laces a snowshoe" and is related to 'husky', so does not have a direct ] meaning.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://alt-usage-english.org/excerpts/fxeskimo.html |title=Eskimo |first=Mark |last=Israel}}</ref> | |||

| In Canada and Greenland, the term "Eskimo" is seen as pejorative and has been widely replaced by the term "Inuit" or terms specific to a particular nation or community. The ], ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-16.html |title=CANADIAN CHARTER OF RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS|work=Department of Justice Canada|accessdate=August 30, 2012 }}</ref> and ]<ref name="defe">{{cite web |url=http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-16.html |title=RIGHTS OF THE ABORIGINAL PEOPLES OF CANADA|work=Department of Justice Canada|accessdate=August 30, 2012 }}</ref> recognized the Inuit as a distinctive group of ]. | |||

| These ] have traditionally inhabited the Arctic and ] regions from eastern ] (Russia) to ] (United States), ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| However, under U.S. and Alaskan law (as well as the linguistic and cultural traditions of Alaska) "Alaska Native" refers to ''all'' indigenous peoples of Alaska; the term "Alaska Native" also includes groups such as the Aleut, who share a recent ancestor with the Inupiat and Yupik groups, and also includes the largely unrelated<ref>http://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/news-articles/1207/12072012-native-american-migration</ref> ] and the ], who descend from other, unrelated major language and ethnic groups. As a result, the term Eskimo is still in use in Alaska. Alternative terms, such as '''Inuit-Yupik,''' have been proposed,<ref>Holton, Gary. , Academia.edu, Retrieved 27 Jan 2014.</ref> but none has gained widespread acceptance. | |||

| Some Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and other individuals consider the term ''Eskimo'', which is of a disputed etymology,<ref name="Company2005">{{cite book |editor=Houghton Mifflin Company |author=Houghton Mifflin Company |date=2005 |title=The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style |publisher=] |pages=170– |isbn=978-0-618-60499-9 |oclc=496983776 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xb6ie6PqYhwC&pg=PA170 |via=]}}</ref> to be pejorative or even offensive.<ref name="Patrick 2013 p. 2">{{cite book |last=Patrick |first=D. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HWYjAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA2 |title=Language, Politics, and Social Interaction in an Inuit Community |publisher=]|year=2013 |isbn=978-3-11-089770-8 |series=Language, Power and Social Process |page=2 |access-date=November 5, 2021 |via=]}}</ref><ref name="Dorais2010" /> ''Eskimo'' continues to be used within a historical, linguistic, archaeological, and cultural context. The governments in Canada<ref name="publications">{{Cite web |date=June 8, 2020 |title=Words First An Evolving Terminology Relating to Aboriginal Peoples in Canada Communications Branch Indian and Northern Affairs Canada October 2002 |url=http://www.publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/R2-236-2002E.pdf |quote=The term "Eskimo", applied to Inuit by European explorers, is no longer used in Canada.}}</ref><ref name="aboriginal-heritage">{{cite web |date=15 October 2013 |title=Inuit |url=https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/aboriginal-heritage/inuit/Pages/introduction.aspx |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=MacDonald-Dupuis |first=Natasha |date=December 16, 2015 |title=The Little-Known History of How the Canadian Government Made Inuit Wear 'Eskimo Tags' |url=https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/xd7ka4/the-little-known-history-of-how-the-canadian-government-made-inuit-wear-eskimo-tags}}</ref> and the United States<ref>{{Cite news |date=May 24, 2016 |title=Obama signs measure to get rid of the word 'Eskimo' in federal laws |url=https://www.adn.com/alaska-news/2016/05/23/obama-signs-measure-to-get-rid-of-the-word-eskimo-in-federal-laws/ |access-date=July 14, 2020 |work=] |language=en-US}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite web |last=Meng |first=Grace |date=May 20, 2016 |title=H.R.4238 – 114th Congress (2015–2016): To amend the Department of Energy Organization Act and the Local Public Works Capital Development and Investment Act of 1976 to modernize terms relating to minorities. |url=https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/4238 |access-date=July 14, 2020 |website=congress.gov}}</ref> have made moves to cease using the term ''Eskimo'' in official documents, but it has not been eliminated, as the word is in some places written into tribal, and therefore national, legal terminology.<ref>{{cite journal |date=30 January 2020|title=Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs |url=https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/01/30/2020-01707/indian-entities-recognized-by-and-eligible-to-receive-services-from-the-united-states-bureau-of |journal=Federal Register |volume=85 |issue=20 |pages=5462–5467}}</ref> Canada officially uses the term ''Inuit'' to describe the ] who are living in the country's northern sectors and are not ] or ].<ref name="publications" /><ref name="aboriginal-heritage" /><ref name="defe1">{{cite web |date=June 30, 2021 |title=Aboriginal rights and freedoms not affected by Charter |url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-12.html |website=] |publisher=] |quote=his Charter of certain rights and freedoms shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada.}}</ref><ref name="s35">{{cite web |date=June 30, 2021 |title=Rights of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada |url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-13.html?txthl=inuit#s-35 |website=Constitution Act, 1982 |publisher=] |quote=In this Act, aboriginal peoples of Canada includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.}}</ref> The United States government legally uses '']''<ref name=":0" /> for enrolled tribal members of the Yupik, Inuit, and Aleut, and also for non-Eskimos including the ], the ], the ], and the ], in addition to at least nine ] peoples.<ref name="Who is an American Indian or Alaska Native?">{{cite web |title=Frequently Asked Questions |url=https://www.bia.gov/frequently-asked-questions |publisher=], ]}}</ref> Other non-enrolled individuals also claim Eskimo/Aleut descent, making it the world's "most widespread aboriginal group".<ref>{{Cite web |title=Race Relations In The USA and Diversity News |url=https://www.usaonrace.com/sticky-wicket-questions/1462/is-the-term-eskimo-a-racial-or-ethnic-insult.htmlIs |website=www.usaonrace.com}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=August 28, 2014 |title=Ancient DNA Sheds New Light on Arctic's Earliest People |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/140828-arctic-migration-genome-genetics-dna-eskimos-inuit-dorset |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210309202653/http://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/140828-arctic-migration-genome-genetics-dna-eskimos-inuit-dorset |url-status=dead |archive-date=March 9, 2021 |website=Culture}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Eskimos |url=https://www.factmonster.com/eskimos |website=FactMonster}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Several earlier indigenous peoples existed in the region. The earliest positively identified North American Eskimo cultures (pre-Dorset) date to 5,000 years ago. They appear to have developed in Alaska from people related to the ] in eastern Asia, whose ancestors had probably migrated to Alaska at least 3,000 to 5,000 years earlier. Similar artifacts have been found in Siberia that date to perhaps 18,000 years ago. | |||

| There are between 171,000 and 187,000 Inuit and Yupik, the majority of whom live in or near their traditional circumpolar homeland. Of these, 53,785 (2010) live in the United States, 70,545 (2021) in Canada, 51,730 (2021) in Greenland and 1,657 (2021) in Russia. In addition, 16,730 people living in Denmark were born in Greenland.<ref name="statscan">{{cite web |date=September 21, 2022 |title=Indigenous peoples – 2021 Census promotional material |url=https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/census/census-engagement/community-supporter/indigenous-peoples |access-date=July 20, 2024 |website=Statistics Canada |publisher=]}}</ref><ref name="CIAworld">{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/greenland/ |title=Greenland |access-date=April 3, 2021 |publisher=] |work=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf |title=The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author= |url=https://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn_popul |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200124160257/http://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn_popul |url-status=dead |archive-date=January 24, 2020 |title=Всероссийская перепись населения 2020 года |lang=ru |website= |publisher= |date= |access-date=July 17, 2023 }}</ref><ref> ]</ref> The ], a ] (NGO), claims to represent 180,000 people.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/ |title=Inuit Circumpolar Council – United Voice of the Arctic}}</ref> | |||

| The ] and cultures in Alaska evolved in place (and migrated back to Siberia), beginning with the original ] indigenous culture developed in Alaska. Approximately 4000 years ago, the Unangan culture of the ] became distinct. It is not generally considered an Eskimo culture. | |||

| In the Eskaleut ], the Eskimo branch has an Inuit language sub-branch, and a sub-branch of four ]. Two Yupik languages are used in the ] as well as on ], and two in western Alaska, southwestern Alaska, and western ]. The extinct ] language is sometimes claimed to be related. | |||

| Approximately 1500–2000 years ago, apparently in Northwestern Alaska, two other distinct variations appeared. Inuit language became distinct and, over a period of several centuries, its speakers migrated across Northern Alaska, through Canada and into ]. The distinct culture of the ] developed in northwestern Alaska and very quickly spread over the entire area occupied by Eskimo people, though it was not necessarily adopted by all of them. | |||

| ==Nomenclature== | == <span id="Terminology"></span>Nomenclature == | ||

| === |

=== Etymology === | ||

| {{Further|Native American name controversy}} | {{Further|Native American name controversy}} | ||

| ] of Eskimo peoples, showing the ] (], ]) and ] (], ], ], ], ], ])]] | |||

| {{Wiktionary|eskimo|Eskimo}} | |||

| A variety of theories have been postulated for the etymological origin of the word ''Eskimo''.<ref>{{cite book |first=Donna |last=Patrick |date=June 10, 2013 |title=Language, Politics, and Social Interaction in an Inuit Community |publisher=] |pages=2– |isbn=978-3-11-089770-8 |oclc=1091560161 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HWYjAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA2 |via=]}}</ref><ref name="Hobson2004">{{cite book |editor-first=Archie |editor-last=Hobson |date=2004 |title=The Oxford Dictionary of Difficult Words |publisher=] |pages=160– |isbn=978-0-19-517328-4 |oclc=250009148 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vm_mNJiflwgC&pg=PA160 |via=]}}</ref><ref name="BackhouseHistory1999">{{cite book |first1=Constance |last1=Backhouse |author2=Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History |date=January 1, 1999 |title=Colour-coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950 |publisher=] |pages=27– |isbn=978-0-8020-8286-2 |oclc=247186607 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BZlsTAH7GWIC&pg=PA27 |via=]}}</ref><ref name="Steckley2008">{{cite book |first=John |last=Steckley |date=1 January 2008 |title=White Lies about the Inuit |publisher=] |pages=21– |isbn=978-1-55111-875-8 |oclc=1077854782 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i-osjdNH3g8C&pg=PA21 |via=]}}</ref><ref name="McElroy 2007 p. 8">{{cite book |last=McElroy |first=A. |title=Nunavut Generations: Change and Continuity in Canadian Inuit Communities |publisher=] |year=2007 |isbn=978-1-4786-0961-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-WkbAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA8 |access-date=November 5, 2021 |page=8 |via=]}}</ref><ref name="Dorais2010">{{cite book |first=Louis-Jacques |last=Dorais |date=2010 |title=Language of the Inuit: Syntax, Semantics, and Society in the Arctic |publisher=] - MQUP |pages=297– |isbn=978-0-7735-3646-3 |oclc=1048661404 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gkfdQpHUdh4C&pg=PA297 |via=]}}</ref> According to Smithsonian linguist ], etymologically the word derives from the ] (Montagnais) word {{lang|moe|ayas̆kimew}}, meaning 'a person who laces a ]',<ref name="ENBR" /><ref name="kaplannew">{{Cite web |title=Inuit or Eskimo: Which name to use? |publisher=], ] |url=https://uaf.edu/anlc/research-and-resources/resources/resources/inuit_or_eskimo.php |access-date=December 3, 2022 |website=www.uaf.edu |first=Lawrence |last=Kaplan |archive-date=December 30, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221230133641/https://uaf.edu/anlc/research-and-resources/resources/resources/inuit_or_eskimo.php |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="Goddard">{{cite book |first=R. H. Ives |last=Goddard |chapter=Synonymy |editor=David Damas |title=Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 5 Arctic |location=] |publisher=] |year=1985 |isbn=978-0874741858 |pages=5–7 }}</ref> and is related to '']'' (a breed of dog).{{Citation needed|date=March 2023}} The word {{lang|moe|assime·w}} means 'she laces a snowshoe' in Innu, and ] speakers refer to the neighbouring ] people using words that sound like ''eskimo''.<ref name="goddard">{{cite book |last=Goddard |first=Ives |chapter=Synonymy |editor=William C. Sturtevant |title=Handbook of North American Indians: Volume 5 Arctic |location=] |publisher=] |year=1984 |pages=5–7 }} Cited in Campbell 1997</ref><ref name="campbell">{{cite book |last=Campbell |first=Lyle |year=1997 |title=American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America |page=394 |location=New York |publisher=] }}</ref> This interpretation is generally confirmed by more recent academic sources.<ref>{{cite book |last=Holst |first=Jan Henrik |date=May 10, 2022 |editor1-last=Danler |editor1-first=Paul |editor2-last=Harjus |editor2-first=Jannis |title=Las Lenguas De Las Americas - the Languages of the Americas |publisher=Logos Verlag Berlin |pages=13–26 |chapter=A Survey of Eskimo-Aleut Languages |isbn=978-3-8325-5279-4}}</ref> | |||

| In 1978, ], a Quebec anthropologist who speaks Innu-aimun (Montagnais), published a paper suggesting that ''Eskimo'' meant 'people who speak a different language'.<ref name="mailhot1">{{cite journal |last=Mailhot |first=José |author-link=José Mailhot |year=1978 |title=L'étymologie de «Esquimau» revue et corrigée |journal=Études Inuit/Inuit Studies |volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=59–70 }}</ref><ref name="creeml" /> French traders who encountered the ] (Montagnais) in the eastern areas adopted their word for the more western peoples and spelled it as {{lang|fr|Esquimau}} or {{lang|fr|Esquimaux}} in a transliteration.<ref name="EII" /> | |||

| Two principal competing etymologies have been proposed for the name "Eskimo," both derived from the ] (Montagnais) language, an Algonquian language of the Atlantic Ocean coast. The most commonly accepted today appears to be the proposal of ] at the ], who derives it from the Montagnais word meaning "snowshoe-netter"<ref name="aueo"/> or "to net snowshoes."<ref name=anlc /> The word ''assime·w'' means "she laces a snowshoe" in Montagnais. Montagnais speakers refer to the neighbouring ] using words that sound very much like ''eskimo''.<ref name="goddard">Goddard, Ives (1984). "Synonymy," In ''Arctic'', ed. David Damas. Vol. 5 of ''Handbook of North American Indians'', ed. William C. Sturtevant, pp. 5–7. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Cited in Campbell 1997</ref><ref name="campbell">Campbell, Lyle (1997). ''American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America'', pg. 394. New York: Oxford University Press</ref> | |||

| Some people consider ''Eskimo'' offensive, because it is popularly perceived to mean<ref name="creeml">{{cite web |url=http://www.nisto.com/cree/mail/cree-1997-11.txt |title=Cree Mailing List Digest November 1997 |access-date=2012-06-13 |archive-date=2012-06-20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120620033446/http://nisto.com/cree/mail/cree-1997-11.txt}}</ref><ref name="mailhot">{{cite journal |last=Mailhot |first=José |author-link=José Mailhot |title=L'etymologie de "esquimau" revue et corrigée |language=fr |trans-title=The etymology of "eskimo" revised and corrected |journal=Études/Inuit/Studies |volume=2 |issue=2 |year=1978}}</ref><ref name="igoddard">{{cite book |last=Goddard |first=Ives |author-link=Ives Goddard |title=Handbook of North American Indians |volume=5 (Arctic) |publisher=] |year=1984 |isbn=978-0-16-004580-6}}</ref> 'eaters of raw meat' in ] common to people along the Atlantic coast.<ref name="kaplannew" /><ref name="natlang">{{cite web|url=http://www.native-languages.org/iaq23.htm |title=Setting the Record Straight About Native Languages: What Does "Eskimo" Mean In Cree? |publisher=Native-languages.org |access-date=2012-06-13}}</ref><ref name="bartlebyeskimo">{{cite web |url=http://www.bartleby.com/61/24/E0212400.html |title=Eskimo |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20010412155403/http://www.bartleby.com/61/24/E0212400.html |archive-date=2001-04-12 |publisher=Bartleby |work=American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition, 2000 |access-date=January 13, 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> An unnamed ] speaker suggested the original word that became corrupted to Eskimo might have been {{lang|cr|askamiciw}} (meaning 'he eats it raw'); Inuit are referred to in some Cree texts as {{lang|cr|askipiw}} (meaning 'eats something raw').<ref name="natlang" /><ref name="bartlebyeskimo" /><ref name="stern1">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3UHTsUmt1PEC |title=Historical Dictionary of the Inuit |first=Pamela R. |last=Stern |access-date=June 13, 2012 |isbn=978-0-8108-6556-3 |date=July 27, 2004 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |via=]}}</ref><ref name="ostg1">{{cite web |first1=Robert |last1=Peroni |first2=Birgit |last2=Veith |url=http://www.ostgroenland-hilfe.de/en/projekt.html |title=Ostgroenland-Hilfe Project |publisher=Ostgroenland-hilfe.de |access-date=June 13, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120318173645/http://www.ostgroenland-hilfe.de/en/projekt.html |archive-date=March 18, 2012}}</ref><ref name="publications" /><ref>{{Cite dictionary |entry=Eskimo |dictionary=Oxford Dictionary |via=Lexico.com |url=https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/eskimo |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210210154048/https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/eskimo |archive-date=February 10, 2021 |access-date=December 19, 2020 |language=en}}</ref> Regardless, the term still carries a derogatory connotation for many Inuit and Yupik.<ref name="kaplannew" /><ref name="natlang" /><ref name="NPR">{{Cite news |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/04/24/475129558/why-you-probably-shouldnt-say-eskimo |title=Why You Probably Shouldn't Say 'Eskimo' |first=Rebecca |last=Hersher |date=April 24, 2016 |newspaper=]}}</ref><ref name="global">{{Cite news |last=Purdy |first=Chris |date=November 27, 2015 |url=https://globalnews.ca/news/2366689/expert-says-meat-eater-name-eskimo-an-offensive-term-placed-on-inuit/ |title=Expert says 'meat-eater' name Eskimo an offensive term placed on Inuit |work=] }}</ref> | |||

| In 1978, Jose Mailhot, a Quebec anthropologist who speaks Montagnais, published a paper suggesting that Eskimo meant "people who speak a different language".<ref name="mailhot1">Mailhot, J. (1978). "L'étymologie de «Esquimau» revue et corrigée," ''Etudes Inuit/Inuit Studies'' 2-2:59–70.</ref><ref name="creeml"/> French traders who encountered the Montagnais in the eastern areas, adopted their word for the more western peoples and spelled it as ''Esquimau'' in a transliteration. | |||

| One of the first printed uses of the French word {{lang|fr|Esquimaux}} comes from ]'s ''A Journey from Prince of Wales's Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean in the Years 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772'' first published in 1795.<ref>{{Cite book |url=http://www.gutenberg.org/files/38404/38404-h/38404-h.htm |title=The Project Gutenberg eBook of A Journey from Prince of Wales's Fort in Hudson's Bay to the Northern Ocean, by Samuel Hearne. |via=www.gutenberg.org}}</ref> | |||

| Some people consider ''Eskimo'' derogatory because it is widely perceived to mean<ref name="aueo">{{cite web|url=http://alt-usage-english.org/excerpts/fxeskimo.html |title=Eskimo |first=Mark |last=Israel |publisher=Alt-usage-english.org |accessdate=2012-06-13}}</ref><ref name="creeml">{{cite web|url=http://www.nisto.com/cree/mail/cree-1997-11.txt |title=Cree Mailing List Digest November 1997 |accessdate=2012-06-13}}</ref><ref name="mailhot">{{cite journal | last =Mailhot | first =Jose | title =L'etymologie de "esquimau" revue et corrigée | journal =Etudes/Inuit/Studies | volume = 2 | issue =. 2 | year=1978}}</ref><ref name="igoddard">{{cite book | last =Goddard | first =Ives | authorlink =Ives Goddard | title =Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 5 (Arctic) | publisher =] | year =1984 | isbn = 978-0-16-004580-6}}</ref> "eaters of raw meat" in ] common to people along the Atlantic coast.<ref name=anlc /><ref name="natlang">{{cite web|url=http://www.native-languages.org/iaq23.htm |title=Setting the Record Straight About Native Languages: What Does "Eskimo" Mean In Cree? |publisher=Native-languages.org |accessdate=2012-06-13}}</ref><ref name="bartlebyeskimo">, ''American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'': Fourth Edition, 2000</ref> One ] speaker suggested the original word that became corrupted to Eskimo might have been ''askamiciw'' (which means "he eats it raw"); the Inuit are referred to in some Cree texts as ''askipiw'' (which means "eats something raw").<ref name="natlang" /><ref name="bartlebyeskimo" /><ref name="stern1">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3UHTsUmt1PEC&dq=isbn:0810850583 |title=Historical Dictionary of the Inuit |author= Pamela R. Stern |publisher=Books.google.com |accessdate=2012-06-13}}</ref><ref name="ostg1">{{cite web|author=Robert Peroni and Birgit Veith |url=http://www.ostgroenland-hilfe.de/en/projekt.html |title=Ostgroenland-Hilfe Project |publisher=Ostgroenland-hilfe.de |accessdate=2012-06-13}}</ref> | |||

| === Usage === | |||

| In 1977, the ] meeting in ], officially adopted "Inuit" as a designation for all Eskimo peoples, regardless of their local usages.{{Citation needed|date=December 2009}} The Inuit Circumpolar Council, as it is known today, uses both "Inuit" and "Eskimo" in its official documents.<ref> {{wayback|url=http://inuitcircumpolar.indelta.com/index.php?ID=99 |date=20130927064659 }}</ref><ref> {{wayback|url=http://inuitcircumpolar.indelta.com/index.php?ID=214 |date=20130927064740 }}</ref> | |||

| ] from hardened leather reinforced by wood and bones worn by ] and Eskimos]] | |||

| ] worn by ]]] | |||

| The term ''Eskimo'' is still used by people to encompass Inuit and Yupik, as well as other Indigenous or Alaska Native and Siberian peoples.<ref name="ENBR" /><ref name="NPR" /><ref name="mweb">{{cite web |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Eskimo |title=Eskimo: Websters Dictionary |access-date=April 1, 2021}}</ref> In the 21st century, usage in North America has declined.<ref name="kaplannew" /><ref name="global" /> Linguistic, ethnic, and cultural differences exist between Yupik and Inuit. | |||

| ===General=== | |||

| ] from hardened leather reinforced by wood and bones worn by ] and Eskimos]] | |||

| ] worn by ] and Eskimos]] | |||

| In Canada and Greenland the term ''Eskimo'' has largely been supplanted by the term ''Inuit''.<ref name=anlc /><ref name="stern1"/><ref name="ostg1"/><ref name="bartlebyinuit">usage note, , ''American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'': Fourth Edition, 2000</ref> While ''Inuit'' accurately can be applied to all of the Eskimo peoples in Canada and Greenland, that is not true in Alaska and Siberia. In Alaska the term 'Eskimo' is commonly used, because it includes both Yupik and Iñupiat. 'Inuit' is not accepted as a collective term and it is not used specifically for Iñupiat (although they are Inuit).<ref name=anlc/> | |||

| In Canada and Greenland, and to a certain extent in Alaska, the term ''Eskimo'' is predominantly seen as offensive and has been widely replaced by the term ''Inuit''{{hsp}}<ref name="kaplannew" /><ref name="stern1" /><ref name="ostg1" /><ref name="ahdinuit">Usage note, , ''American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'': Fourth Edition, 2000</ref> or terms specific to a particular group or community.<ref name="kaplannew" /><ref name="Waite2013">{{cite book |first=Maurice |last=Waite |title=Pocket Oxford English Dictionary |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xqKcAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA305 |year=2013 |publisher=] |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-966615-7 |page=305 |quote=Some people regard the word Eskimo as offensive, and the peoples inhabiting the regions of northern Canada and parts of Greenland and Alaska prefer to call themselves Inuit |via=]}}</ref><ref name="SvartvikLeech2016">{{cite book |first1=Jan |last1=Svartvik |first2=Geoffrey |last2=Leech |title=English – One Tongue, Many Voices |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rtl6DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA97 |year=2016 |publisher=] UK |isbn=978-1-137-16007-2 |page=97 |quote=Today, the term "Eskimo" is viewed as the "non preferred term". Some Inuit find the term offensive or derogatory. |via=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.adn.com/alaska-news/2016/05/23/obama-signs-measure-to-get-rid-of-the-word-eskimo-in-federal-laws/ |title=Obama signs measure to get rid of the word 'Eskimo' in federal laws |date=May 24, 2016}}</ref> This has resulted in a trend whereby some non-Indigenous people believe that they should use ''Inuit'' even for Yupik who are non-].<ref name="kaplannew" /> | |||

| In 1977, the Inuit Circumpolar Conference meeting in Barrow, Alaska, officially adopted Inuit as a designation for all circumpolar native peoples, regardless of their local view on an appropriate term. As a result, the Canadian government usage has replaced the (locally) defunct term Eskimo with ''Inuit'' (''Inuk'' in singular). The preferred term in Canada's Central Arctic is ''Inuinnaq'',<ref name=translate>{{cite book|last=Ohokak|first=G.|author2=M. Kadlun |author3=B. Harnum |title=Inuinnaqtun-English Dictionary|publisher=Kitikmeot Heritage Society}}</ref> and in the eastern Canadian Arctic ''Inuit''. The language is often called ''Inuktitut'', though other local designations are also used. | |||

| ] generally refer to themselves as Greenlanders ({{lang|kl|Kalaallit}} or {{lang|da-GL|Grønlændere}}) and speak the ] and Danish.<ref name="kaplannew" /><ref name="ethno"> ''Ethnologue''. Retrieved 6 Aug 2012.</ref> Greenlandic Inuit belong to three groups: the ] of west Greenland, who speak ];<ref name="ethno" /> the ] of ] (east Greenland), who speak ] ("East Greenlandic"); and the ] of north Greenland, who speak ]. | |||

| The word ''Eskimo'' is a racially charged term in Canada.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/eskimo-pie-name-change-1.5620201 |title=Eskimo Pie owner to change ice cream's name, acknowledging derogatory term |date=June 19, 2020 |publisher=] |access-date=September 25, 2020 |quote=The U.S. owner of Eskimo Pie ice cream will change the product's brand name and marketing, it told Reuters on Friday, becoming the latest company to rethink racially charged brand imagery amid a broad debate on racial injustice.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cbc.ca/sports/football/cfl/edmonton-eskimos-team-name-july8-1.5641937 |title=Edmonton CFL team heeds sponsors' calls, accelerates review of potential name change |date=July 8, 2020 |publisher=] |access-date=September 25, 2020 |quote=Edmonton's team has seen repeated calls for a name change in the past, and faces renewed criticism as sports teams in Canada, the United States and elsewhere are urged to remove outdated and sometimes racist names and images.}}</ref> In Canada's Central Arctic, {{lang|ik|Inuinnaq}} is the preferred term,<ref name="translate">{{cite book |last1=Ohokak |first1=G. |first2=M. |last2=Kadlun |first3=B. |last3=Harnum |title=Inuinnaqtun-English Dictionary |publisher=Kitikmeot Heritage Society}}</ref> and in the eastern Canadian Arctic {{lang|iu|Inuit}}. The language is often called '']'', though other local designations are also used. | |||

| Because of the linguistic, ethnic, and cultural differences between Yupik and Inuit peoples, it seems unlikely that any umbrella term will be acceptable. There has been some movement to use ''Inuit'', and the ], representing a circumpolar population of 150,000 Inuit and Yupik people of Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and Siberia, in its charter defines ''Inuit'' for use within that ICC document as including "the Inupiat, Yupik (Alaska), Inuit, ] (Canada), ] (Greenland) and Yupik (Russia)."<ref name="ICCcharter">Inuit Circumpolar Council. (2006). Retrieved on 2007-04-06.</ref> But, in Alaska, the Inuit people refer to themselves as ''Iñupiat'', plural, and ''Iñupiaq'', singular (their ] is also called ''Iñupiaq'') and do not use the term Inuit as commonly. Thus, in Alaska, ''Eskimo'' is in common usage.<ref name=anlc /> | |||

| ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-15.html |title=Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms |work=] |access-date=August 30, 2012}}</ref> of the ] and ]<ref name="defe">{{cite web |url=http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-16.html |title=Rights of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada |work=] |access-date=August 30, 2012}}</ref> of the ] recognized Inuit as a distinctive group of ]. Although ''Inuit'' can be applied to all of the Eskimo peoples in Canada and Greenland, that is not true in Alaska and Siberia. In Alaska, the term ''Eskimo'' is still used because it includes both ] (singular: Iñupiaq), who are Inuit, and ], who are not.<ref name="kaplannew" /> | |||

| Alaskans also use the term ], which is inclusive of all Eskimo, Aleut and ] people of Alaska. It does not apply to Inuit or Yupik people originating outside the state. The term ''Alaska Native'' has important legal usage in Alaska and the rest of the United States as a result of the ] of 1971. | |||

| The term '']'' is inclusive of (and under U.S. and Alaskan law, as well as the linguistic and cultural legacy of Alaska, refers to) all Indigenous peoples of Alaska,<ref name="Company2005"/> including not only the Iñupiat (Alaskan Inuit) and the Yupik, but also groups such as the Aleut, who share a recent ancestor, as well as the largely unrelated<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2012/jul/native-american-populations-descend-three-key-migrations |title=Native American populations descend from three key migrations |date=July 12, 2012 |website=UCL News |publisher=] |access-date=December 12, 2018}}</ref> ] and the ], such as the ]. The term ''Alaska Native'' has important legal usage in Alaska and the rest of the United States as a result of the ] of 1971. It does not apply to Inuit or Yupik originating outside the state. As a result, the term Eskimo is still in use in Alaska.<ref name="Stern2013">{{cite book |first=Pamela R. |last=Stern |title=Historical Dictionary of the Inuit |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jVsrAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA2 |date=2013 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=978-0-8108-7912-6 |page=2 |via=]}}</ref><ref name="ENBR">{{Cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Eskimo-people |entry=Eskimo |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia Britannica |title=Inuit | Definition, History, Culture, & Facts | Britannica |date=28 April 2023 }}</ref> Alternative terms, such as ''Inuit-Yupik'', have been proposed,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Holton |first1=Gary |year=2018 |chapter=Place naming strategies in Inuit-Yupik and Dene languages in Alaska |editor1-first=Kenneth L. |editor1-last=Pratt |editor2-first=Scott |editor2-last=Heyes |title=Language, memory and landscape: Experiences from the boreal forest to the tundra |pages=1–27 |location=Calgary |publisher=]}}</ref> but none has gained widespread acceptance. Early 21st century population estimates registered more than 135,000 individuals of Eskimo descent, with approximately 85,000 living in North America, 50,000 in Greenland, and the rest residing in Siberia.<ref name="ENBR" /> | |||

| The term "Eskimo" is also used in linguistic or ethnographic works to denote the larger branch of Eskimo–Aleut languages, the smaller branch being Aleut. | |||

| === Inuit Circumpolar Council === | |||

| ==Languages== | |||

| In 1977, the ] (ICC) meeting in Barrow, Alaska (now ]), officially adopted ''Inuit'' as a designation for all circumpolar Native peoples, regardless of their local view on an appropriate term. They voted to replace the word ''Eskimo'' with ''Inuit''.<ref name="MacKenzie 2014 p. 60">{{cite book |last=MacKenzie |first=S. |title=Films on Ice: Cinemas of the Arctic |publisher=] |series=Traditions in World Cinema |year=2014 |isbn=978-0-7486-9418-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JXAxEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA60 |access-date=5 Nov 2021 |page=60 |via=]}}</ref> Even at that time, such a designation was not accepted by all.<ref name="kaplannew" /><ref name="EII">{{Cite web|url=https://www.alaskan-natives.com/2166/eskimo-inuit-inupiaq-terms-thing/|title=Eskimo, Inuit, and Inupiaq: Do these terms mean the same thing?}}</ref> As a result, the Canadian government usage has replaced the term ''Eskimo'' with {{lang|iu|Inuit}} ({{lang|iu|Inuk}} in singular). | |||

| {{Main|Eskimo–Aleut languages}} | |||

| ] (''Paġlagivsigiñ Utqiaġvigmun''), ]]] | |||

| The ] family of languages includes two cognate branches: the ] (Unangan) branch and the Eskimo branch. The Eskimo sub-family consists of the ] and Yupik language sub-groups.<ref name="FortecueM">{{Cite journal | title = Comparative Eskimo Dictionary with Aleut Cognates | author = Michael Fortescue|author2=Steven Jacobson |author3=Lawance Kaplan | publisher = ], ]}}</ref> The ], which is virtually extinct, is sometimes regarded as a third branch of the Eskimo language family. Other sources regard it as a group belonging to the Yupik branch.<ref name="FortecueM"/><ref name="kaplanB">Kaplan, Lawrence. (2001-12-10). . ], ]. Retrieved on August 30, 2012.</ref> | |||

| The ICC charter defines ''Inuit'' as including "the Inupiat, Yupik (Alaska), Inuit, ] (Canada), ] (Greenland) and Yupik (Russia)".<ref name="ICCcharter">{{cite web |url=https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/icc-international/icc-charter/ |title=ICC Charter |date=3 January 2019 |publisher=] |access-date=April 3, 2021}}</ref> Despite the ICC's 1977 decision to adopt the term ''Inuit'', this has not been accepted by all or even most Yupik people.<ref name="MacKenzie 2014 p. 60" /> | |||

| Inuit languages comprise a ], or dialect chain, that stretches from ] and ] in Alaska, across northern Alaska and Canada, and east to Greenland. Changes from western (Iñupiaq) to eastern dialects are marked by the dropping of vestigial Yupik-related features, increasing consonant assimilation (e.g., ''kumlu'', meaning "thumb", changes to ''kuvlu'', changes to ''kublu'',<ref name=livingdict/> changes to ''kulluk'',<ref name=livingdict/> changes to ''kulluq''<ref name=livingdict>{{cite web|url=http://www.livingdictionary.com/search/viewResults.jsp?language=en&searchString=thumb&languageSet=all |title=thumb|work=Asuilaak Living Dictionary|accessdate=2007-11-25}}</ref>), and increased consonant lengthening, and lexical change. Thus, speakers of two adjacent Inuit dialects would usually be able to understand one another, but speakers from dialects distant from each other on the dialect continuum would have difficulty understanding one another.<ref name="kaplanB"/> ] dialects in Western Alaska, where much of the ] culture has been in place for perhaps less than 500 years, are greatly affected by phonological influence from the Yupik languages. Eastern Greenlandic, at the opposite end of the Inuit range, has had significant word replacement due to a unique form of ritual name avoidance.<ref name="FortecueM"/><ref name="kaplanB"/> | |||

| In 2010, the ICC passed a resolution in which they implored scientists to use ''Inuit'' and ''Paleo-Inuit'' instead of ''Eskimo'' or ''Paleo-Eskimo''.<ref name="ICC2010-01">{{cite web |author=Inuit Circumpolar Council |title=On the use of the term Inuit in scientific and other circles |type=Resolution 2010-01 |url=https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/iccexcouncilresolutiononterminuit.pdf |date=2010}}</ref> | |||

| The four ], by contrast, including Alutiiq (Sugpiaq), Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Naukan (Naukanski), and Siberian Yupik, are distinct languages with phonological, morphological, and lexical differences. They demonstrate limited mutual intelligibility.<ref name="FortecueM"/> Additionally, both Alutiiq and Central Yup'ik have considerable dialect diversity. The northernmost Yupik languages – Siberian Yupik and ] – are linguistically only slightly closer to Inuit than is Alutiiq, which is the southernmost of the Yupik languages. Although the grammatical structures of Yupik and Inuit languages are similar, they have pronounced differences phonologically. Differences of vocabulary between Inuit and any one of the Yupik languages are greater than between any two Yupik languages.<ref name="kaplanB"/> Even the dialectal differences within Alutiiq and Central Alaskan Yup'ik sometimes are relatively great for locations that are relatively close geographically.<ref name="kaplanB"/> | |||

| ==== Academic response ==== | |||

| In a 2015 commentary in the journal '']'', Canadian archaeologist Max Friesen argued fellow Arctic archaeologists should follow the ICC and use ''Paleo-Inuit'' instead of ''Paleo-Eskimo''.<ref name="Friesen, 2015">{{cite journal |last1=Friesen |first1=T. Max |title=On the Naming of Arctic Archaeological Traditions: The Case for Paleo-Inuit |journal=] |date=2015 |volume=68 |issue=3 |pages=iii–iv |doi=10.14430/arctic4504 |doi-access=free |hdl=10515/sy5sj1b75 |hdl-access=free}}</ref> In 2016, Lisa Hodgetts and ''Arctic'' editor Patricia Wells wrote: "In the Canadian context, continued use of any term that incorporates ''Eskimo'' is potentially harmful to the relationships between archaeologists and the Inuit and Inuvialuit communities who are our hosts and increasingly our research partners." | |||

| Hodgetts and Wells suggested using more specific terms when possible (e.g., ] and ]) and agreed with Frieson in using the ''Inuit tradition'' to replace ''Neo-Eskimo'', although they noted replacement for ''Palaeoeskimo'' was still an open question and discussed ''Paleo-Inuit'', ''Arctic Small Tool Tradition'', and ''pre-Inuit'', as well as Inuktitut loanwords like {{lang|iu|Tuniit}} and {{lang|iu|Sivullirmiut}}, as possibilities.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hodgetts |first1=Lisa |last2=Wells |first2=Patricia |title=Priscilla Renouf Remembered: An Introduction to the Special Issue with a Note on Renaming the Palaeoeskimo Tradition |journal=Arctic |date=2016 |volume=69 |issue=5 |doi=10.14430/arctic4678 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| In 2020, Katelyn Braymer-Hayes and colleagues argued in the '']'' that there is a "clear need" to replace the terms ''Neo-Eskimo'' and ''Paleo-Eskimo'', citing the ICC resolution, but finding a consensus within the Alaskan context particularly is difficult, since ] do not use the word ''Inuit'' to describe themselves nor is the term legally applicable only to Iñupiat and Yupik in Alaska, and as such, terms used in Canada like ''Paleo Inuit'' and ''Ancestral Inuit'' would not be acceptable.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Braymer-Hayes |first1=Katelyn |last2=Anderson |first2=Shelby L. |last3=Alix |first3=Claire |last4=Darwent |first4=Christyann M. |last5=Darwent |first5=John |last6=Mason |first6=Owen K. |last7=Norman |first7=Lauren Y.E. |title=Studying pre-colonial gendered use of space in the Arctic: Spatial analysis of ceramics in Northwestern Alaska |journal=] |date=2020 |volume=58 |page=101165 |doi=10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101165 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| American linguist ] has also explicitly deferred to the ICC resolution and used ''Inuit–Yupik'' instead of ''Eskimo'' with regards to the language branch.<ref name="Grenoble, 2016">{{cite book |last=Grenoble |first=Lenore A. |author-link=Lenore Grenoble |editor1-last=Day |editor1-first=Delyn |editor2-last=Rewi |editor2-first=Poia |editor2-link=Poia Rewi |editor3-last=Higgins |editor3-first=Rawinia |editor3-link=Rawinia Higgins |title=The Journeys of Besieged Languages |date=2016 |publisher=Cambridge Scholars |isbn=978-1-4438-9943-7 |page=284 |chapter=Kalaallisut: The Language of Greenland}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Grenoble |first1=Lenore A. |editor1-last=Hinton |editor1-first=Leanne |editor2-last=Huss |editor2-first=Leena |editor3-last=Roche |editor3-first=Gerald |title=The Routledge Handbook of Language Revitalization |date=2018 |publisher=] |doi=10.4324/9781315561271 |page=353 |chapter=Arctic Indigenous Languages: Vitality and Revitalization |hdl=10072/380836 |isbn=978-1-315-56127-1|s2cid=150673555 }}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| Genetic evidence suggests that the Americas were populated from northeastern Asia in multiple waves. While the great majority of indigenous American peoples can be traced to a single early migration of ], the ], ] and ] populations exhibit admixture from ] that migrated into America at a later date and are closely linked to the peoples of far northeastern Asia (e.g. ]), and only more remotely to the majority indigenous American type. For modern ] speakers, this later ancestral component makes up almost half of their genomes.<ref>{{Cite journal |pmc=3615710 |year=2012 |last1=Reich |first1=D. |last2=Patterson |first2=N. |last3=Campbell |first3=D. |last4=Tandon |first4=A.|last5=Mazieres |first5=S. |last6=Ray |first6=N. |last7=Parra |first7=M. V. |last8=Rojas |first8=W. |last9=Duque |first9=C. |last10=Mesa |first10=N. |last11=García |first11=L. F. |last12=Triana |first12=O. |last13=Blair |first13=S. |last14=Maestre |first14=A. |last15=Dib |first15=J. C. |last16=Bravi |first16=C. M. |last17=Bailliet |first17=G. |last18=Corach |first18=D. |last19=Hünemeier |first19=T. |last20=Bortolini |first20=M. C. |last21=Salzano |first21=F. M. |last22=Petzl-Erler |first22=M. L. |last23=Acuña-Alonzo |first23=V. |last24=Aguilar-Salinas |first24=C. |last25=Canizales-Quinteros |first25=S. |last26=Tusié-Luna |first26=T. |last27=Riba |first27=L. |last28=Rodríguez-Cruz |first28=M. |last29=Lopez-Alarcón |first29=M. |last30=Coral-Vazquez |first30=R. |display-authors=3 |title=Reconstructing Native American Population History |journal=] |volume=488 |issue=7411 |pages=370–374 |doi=10.1038/nature11258 |pmid=22801491 |bibcode=2012Natur.488..370R}}</ref> The ancient ] population was genetically distinct from the modern circumpolar populations, but eventually derives from the same far northeastern Asian cluster.<ref name="Raghavan et al 2014"/> It is understood that some or all of these ancient people migrated across the ] to North America during the pre-neolithic era, somewhere around 5,000 to 10,000 years ago.<ref name="Flegontov et al 2017">{{cite journal |last1=Flegontov |first1=Pavel |last2=Altinişik |first2=N. Ezgi |last3=Changmai |first3=Piya |last4=Rohland |first4=Nadin |last5=Mallick |first5=Swapan |last6=Bolnick |first6=Deborah A. |last7=Candilio |first7=Francesca |last8=Flegontova |first8=Olga |last9=Jeong |first9=Choongwon |last10=Harper |first10=Thomas K. |last11=Keating |first11=Denise |last12=Kennett |first12=Douglas J. |last13=Kim |first13=Alexander M. |first27=Stephan |last27=Schiffels |first26=David |last26=Reich |first25=Johannes |last25=Krause |first24=Ron |last24=Pinhasi |last23=O'Rourke |last15=Olalde |first18=Pontus |first15=Iñigo |last14=Lamnidis |first16=Jennifer |last17=Sattler |first17=Robert A. |last18=Skoglund |last19=Vajda |first22=M. Geoffrey |first19=Edward J. |last20=Vasilyev |first20=Sergey |last21=Veselovskaya |first21=Elizaveta |last22=Hayes |last16=Raff |display-authors=3 |date=13 October 2017 |title=Paleo-Eskimo genetic legacy across North America |journal=bioRxiv |doi=10.1101/203018 |hdl-access=free |first14=Thiseas C. |first23=Dennis H. |hdl=21.11116/0000-0004-5D08-C |s2cid=90288469}}</ref> It is believed that ancestors of the ] people inhabited the ] 10,000 years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dunne |first1=J. A. |last2=Maschner |first2=H. |last3=Betts |first3=M. W. |last4=Huntly |first4=N. |last5=Russell |first5=R. |last6=Williams |first6=R. J. |last7=Wood |first7=S. A. |display-authors=3 |year=2016 |title=The roles and impacts of human hunter-gatherers in North Pacific marine food webs |journal=] |volume=6 |page=21179 |bibcode=2016NatSR...621179D |doi=10.1038/srep21179 |pmc=4756680 |pmid=26884149}}</ref> | |||

| ] longhouse near ], ]]] | |||

| The earliest positively identified ] cultures (]) date to 5,000 years ago.<ref name="Raghavan et al 2014">{{cite journal |last1=Raghavan |first1=Maanasa |last2=DeGiorgio |first2=Michael |last3=Albrechtsen |first3=Anders |last4=Moltke |first4=Ida |last5=Skoglund |first5=Pontus |last6=Korneliussen |first6=Thorfinn S. |last7=Grønnow |first7=Bjarne |last8=Appelt |first8=Martin |last9=Gulløv |first9=Hans Christian |last10=Friesen |first10=T. Max |last11=Fitzhugh |first11=William |display-authors=3 |date=29 August 2014 |title=The genetic prehistory of the New World Arctic |journal=] |volume=345 |issue=6200 |doi=10.1126/science.1255832 |pmid=25170159 |doi-access=free |last14=Olsen |last44=Kivisild |first47=Finn C. |last47=Nielsen |first46=Michael H. |last46=Crawford |first45=Richard |last45=Villems |first44=Toomas |last42=Götherström |first43=Ludovic |last43=Orlando |first42=Anders |first48=Jørgen |first41=Victor A. |last41=Spitsyn |first40=Joan |last40=Coltrain |first39=M. Geoffrey |last48=Dissing |first50=Morten |last49=Heinemeier |first54=M. Thomas P. |s2cid=353853 |last12=Malmström |first12=Helena |last13=Rasmussen |first56=Eske |last56=Willerslev |first55=Rasmus |last55=Nielsen |last54=Gilbert |first49=Jan |first53=Mattias |last53=Jakobsson |first52=Dennis H. |last52=O'Rourke |first51=Carlos |last51=Bustamante |first38=Hans |last50=Meldgaard |last39=Hayes |last38=Lange |first14=Jesper |last20=Renouf |first24=Kate |last24=Britton |first23=Marta |last23=Mirazón Lahr |first22=Niels |last22=Lynnerup |first21=Jerome |last21=Cybulski |first20=M. A. Priscilla |first19=Vaughan |first25=Rick |last19=Grimes |first18=Thomas |last18=Stafford |first17=Simon M. |last17=Fahrni |first16=Benjamin T. |last16=Fuller |first15=Linea |last15=Melchior |last25=Knecht |last26=Arneborg |first37=Claus |first32=Vibha |last37=Andreasen |first36=Kirill |last36=Dneprovsky |first35=Tracey |last35=Pierre |first34=Elza |last34=Khusnutdinova |first33=Thomas V. O. |last33=Hansen |last32=Raghavan |first26=Jette |first13=Simon |last31=Rasmussen |first30=Yong |last30=Wang |first29=Anna-Sapfo |last29=Malaspinas |first28=Omar E. |last28=Cornejo |first27=Mait |last27=Metspalu |first31=Morten}}</ref> Several earlier indigenous peoples existed in the northern circumpolar regions of eastern Siberia, Alaska, and Canada (although probably not in Greenland).<ref>{{Cite web |date=April 19, 2011 |title=- Saqqaq culture chronology |url=https://natmus.dk/organisation/forskning-samling-og-bevaring/nyere-tid-og-verdens-kulturer/etnografisk-samling/arktisk-forskning/prehistory-of-greenland/saqqaq/ |publisher=]}}</ref> The Paleo-Eskimo peoples appear to have developed in Alaska from people related to the ] in eastern Asia, whose ancestors had probably migrated to Alaska at least 3,000 to 5,000 years earlier.<ref name="Cordell Lightfoot McManamon Milner 2008 p. 3-PA274">{{cite book |last1=Cordell |first1=L.S. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=arfWRW5OFVgC&pg=RA3-PA274 |title=Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia [4 volumes]: An Encyclopedia |last2=Lightfoot |first2=K. |last3=McManamon |first3=F. |last4=Milner |first4=G. |publisher=] |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-313-02189-3 |series=Non-Series |page=3-PA274 |access-date=November 7, 2021 |via=]}}</ref> | |||

| The Yupik languages and cultures in Alaska evolved in place, beginning with the original ] Indigenous culture developed in Alaska. At least 4,000 years ago, the Unangan culture of the ] became distinct. It is not generally considered an Eskimo culture. However, there is some possibility of an Aleutian origin of the ] people,<ref name="Raghavan et al 2014"/> who in turn are a likely ancestor of today's Inuit and Yupik.<ref name="Flegontov et al 2017"/> | |||

| Approximately 1,500 to 2,000 years ago, apparently in northwestern Alaska, two other distinct variations appeared. Inuit language became distinct and, over a period of several centuries, its speakers migrated across northern Alaska, through Canada, and into Greenland. The distinct culture of the ] (drawing strongly from the ]) developed in northwestern Alaska. It very quickly spread over the entire area occupied by Eskimo peoples, though it was not necessarily adopted by all of them.<ref name="Greenberg Croft ProQuest (Firm) 2005 p. 379">{{cite book |last1=Greenberg |first1=J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BlYTDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA379 |title=Genetic Linguistics: Essays on Theory and Method |last2=Croft |first2=W. |author3=ProQuest (Firm) |publisher=] |location=Oxford |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-19-925771-3 |series=Oxford linguistics |page=379 |access-date=November 5, 2021 |via=]}}</ref> | |||

| == Languages == | |||

| {{Main|Eskaleut languages}} | |||

| === Language family === | |||

| ] (''Paġlagivsigiñ Utqiaġvigmun''), ], framed by whale jawbones]] | |||

| The ] family of languages includes two cognate branches: the ] (Unangan) branch and the Eskimo branch.<ref name="Lyovin Kessler Leben 2017 p. 327">{{cite book |last1=Lyovin |first1=A. |last2=Kessler |first2=B. |last3=Leben |first3=W.R. |title=An Introduction to the Languages of the World |publisher=] |year=2017 |isbn=978-0-19-514988-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hjxuDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA327 |access-date=November 7, 2021 |page=327 |via=]}}</ref> | |||

| The number of ] varies, with Aleut languages having a greatly reduced case system compared to those of the Eskimo subfamily. Eskimo–Aleut languages possess voiceless plosives at the ], ], ] and ] positions in all languages except Aleut, which has lost the bilabial stops but retained the ]. In the Eskimo subfamily a voiceless ] ] ] is also present. | |||

| The Eskimo sub-family consists of the ] and Yupik language sub-groups.<ref name="FortecueM">{{Cite book |url=https://www.alaska.edu/uapress/browse/detail/comparative-eskimo-dictionary-with-aleut-cognates.php |title=Comparative Eskimo Dictionary with Aleut Cognates |first1=Michael |last1=Fortescue |author1-link=Michael Fortescue |first2=Steven |last2=Jacobson |first3=Lawrence |last3=Kaplan |publisher=Alaska Native Language Center, ]}}</ref> The ], which is virtually extinct, is sometimes regarded as a third branch of the Eskimo language family. Other sources regard it as a group belonging to the Yupik branch.<ref name="FortecueM"/><ref name="kaplanB">{{cite web |last=Kaplan |first=Lawrence |url=https://www.uaf.edu/anlc/resources/comparative_yupik_and_inuit.php |title=Comparative Yupik and Inuit |date=July 1, 2011 |access-date=April 3, 2021 |publisher=Alaska Native Language Center, ]}}</ref> | |||

| Inuit languages comprise a ], or dialect chain, that stretches from ] and ] in Alaska, across northern Alaska and Canada, and east to Greenland. Changes from western (Iñupiaq) to eastern dialects are marked by the dropping of vestigial Yupik-related features, increasing consonant assimilation (e.g., ''kumlu'', meaning "thumb", changes to ''kuvlu'', changes to ''kublu'', changes to ''kulluk'', changes to ''kulluq'',<ref name=livingdict>{{cite web |url=http://www.livingdictionary.com/search/viewResults.jsp?language=en&searchString=thumb&languageSet=all |title=thumb |work=Asuilaak Living Dictionary |access-date=November 25, 2007}} {{Dead link|date=April 2021}}</ref>) and increased consonant lengthening, and lexical change. Thus, speakers of two adjacent Inuit dialects would usually be able to understand one another, but speakers from dialects distant from each other on the dialect continuum would have difficulty understanding one another.<ref name="kaplanB"/> ] dialects in western Alaska, where much of the ] culture has been in place for perhaps less than 500 years, are greatly affected by phonological influence from the Yupik languages. ], at the opposite end of Inuit range, has had significant word replacement due to a unique form of ritual name avoidance.<ref name="FortecueM"/><ref name="kaplanB"/> | |||

| Ethnographically, ] belong to three groups: the ] of west Greenland, who speak ];<ref name="ethno"/> the ] of ] (east Greenland), who speak ] ("East Greenlandic"), and the ] of north Greenland, who speak ]. | |||

| The four ], by contrast, including ] (Sugpiaq), ], ] (Naukanski), and ], are distinct languages with phonological, morphological, and lexical differences. They demonstrate limited mutual intelligibility.<ref name="FortecueM"/> Additionally, both Alutiiq and Central Yup'ik have considerable dialect diversity. The northernmost Yupik languages – Siberian Yupik and Naukan Yupik – are linguistically only slightly closer to Inuit than is Alutiiq, which is the southernmost of the Yupik languages. Although the grammatical structures of Yupik and Inuit languages are similar, they have pronounced differences phonologically. Differences of vocabulary between Inuit and any one of the Yupik languages are greater than between any two Yupik languages.<ref name="kaplanB"/> Even the dialectal differences within Alutiiq and Central Alaskan Yup'ik sometimes are relatively great for locations that are relatively close geographically.<ref name="kaplanB"/> | |||

| Despite the relatively small population of Naukan speakers, documentation of the language dates back to 1732. While Naukan is only spoken in Siberia, the language acts as an intermediate between two Alaskan languages: Siberian Yupik Eskimo and Central Yup'ik Eskimo.<ref name="erudit.org">{{cite journal |last1=Jacobson |first1=Steven A. |title=History of the Naukan Yupik Eskimo dictionary with implications for a future Siberian Yupik dictionary |journal=Études/Inuit/Studies |date=13 November 2006 |volume=29 |issue=1–2 |pages=149–161 |doi=10.7202/013937ar |s2cid=128785932 |doi-access=}}</ref> | |||

| The Sirenikski language is sometimes regarded as a third branch of the Eskimo language family, but other sources regard it as a group belonging to the Yupik branch.<ref name="kaplanB"/> | The Sirenikski language is sometimes regarded as a third branch of the Eskimo language family, but other sources regard it as a group belonging to the Yupik branch.<ref name="kaplanB"/> | ||

| ] | |||

| An overview of the |

An overview of the Eskimo–Aleut languages family is given below: | ||

| :'''Aleut''' | |||

| ::] | |||

| :::Western-Central dialects: Atkan, Attuan, Unangan, Bering (60–80 speakers) | |||

| :::Eastern dialect: Unalaskan, Pribilof (400 speakers) | |||

| :'''Eskimo''' (Yup'ik, Yuit, and Inuit) | |||

| ::] | |||

| :::] (10,000 speakers) | |||

| :::] or Pacific Gulf Yup'ik (400 speakers) | |||

| :::] or Yuit (Chaplinon and St Lawrence Island, 1,400 speakers) | |||

| :::] (700 speakers) | |||

| ::] or Inupik (75,000 speakers) | |||

| :::] (northern Alaska, 3,500 speakers) | |||

| :::] (western Canada; together with ], ], ] and ] 765 speakers) | |||

| :::] (eastern Canada; together with ] and ], 30,000 speakers) | |||

| :::] (Greenland, 47,000 speakers) | |||

| ::::] (Avanersuarmiutut, Thule dialect or Polar Eskimo, approximately 1,000 speakers) | |||

| ::::] (East Greenlandic known as Tunumiisut, 3,500 speakers) | |||

| ::'''] (Sirenikskiy)''' (extinct) | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| ==Inuit== | |||

| * '''Eskimo–Aleut''' | |||

| **Aleut | |||

| ***] | |||

| ****Western-Central dialects: Atkan, Attuan, Unangan, Bering (60–80 speakers) | |||

| ****Eastern dialect: Unalaskan, Pribilof (400 speakers) | |||

| **Eskimo (Yup'ik, Yuit, and Inuit) | |||

| ***] | |||

| ****] (10,000 speakers) | |||

| ****] or Pacific Gulf Yup'ik (400 speakers) | |||

| ****] or Yuit (Chaplinon and St Lawrence Island, 1,400 speakers) | |||

| ****] (700 speakers) | |||

| ***] or Inupik (75,000 speakers) | |||

| ****] (northern Alaska, 3,500 speakers) | |||

| ****] (western Canada; together with ], ], ] and ] 765 speakers) | |||

| ****] (eastern Canada; together with ] and ], 30,000 speakers) | |||

| ****] (] (Greenland, 47,000 speakers) | |||

| *****] (Avanersuarmiutut, Thule dialect or Polar Eskimo, approximately 1,000 speakers) | |||

| *****] (East Greenlandic known as Tunumiisut, 3,500 speakers) | |||

| ***] (Sirenikskiy) {{extinct}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| American linguist ] has explicitly deferred to this resolution and used ''Inuit–Yupik'' instead of ''Eskimo'' with regards to the language branch.<ref name="Grenoble, 2016"/> | |||

| === Words for ''snow'' === | |||

| {{Main|Eskimo words for snow}} | |||

| There has been a long-running linguistic debate about whether or not the speakers of the Eskimo-Aleut language group have an unusually large number of words for snow. The general modern consensus is that, in multiple Eskimo languages, there are, or have been in simultaneous usage, indeed fifty plus words for snow.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.treehugger.com/are-there-really-eskimo-words-for-snow-4862000|title = Are There Really 50 Eskimo Words for Snow?}}</ref> | |||

| == Diet == | |||

| ] meat. Inuit are known for their practice of food sharing, where large catches of food are shared with the broader community.<ref name="Damas">{{cite journal |last1=Damas |first1=David |year=1972 |title=Central Eskimo Systems of Food Sharing |journal=] |volume=11 |issue=3 |pages=220–240 |doi=10.2307/3773217 |jstor=3773217}}</ref>]]{{Excerpt|Inuit cuisine|paragraph=1,2|only=paragraph|hat=no}} | |||

| == Inuit == | |||

| {{Further|Inuit|Lists of Inuit}} | {{Further|Inuit|Lists of Inuit}} | ||

| {{ |

{{distinguish|text=the ], a First Nations people in eastern Quebec and Labrador}} | ||

| ] of ]) fisherman's summer house]] | |||

| ] man]] | |||

| ], circa 1907]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The Inuit inhabit the ] and northern ] coasts of Alaska in the United States, and Arctic coasts of the ], ], ], and ] in Canada, and Greenland (associated with Denmark). Until fairly recent times, there has been a remarkable homogeneity in the culture throughout this area, which traditionally relied on fish, sea mammals, and land animals for food, heat, light, clothing, and tools. They maintain a unique ]. | |||

| Inuit inhabit the ] and northern ] coasts of Alaska in the United States, and Arctic coasts of the ], ], ], and ] in Canada, and Greenland (associated with Denmark). Until fairly recent times, there has been a remarkable homogeneity in the culture throughout this area, which traditionally relied on fish, ]s, and land animals for food, heat, light, clothing, and tools. Their food sources primarily relied on seals, whales, whale blubber, walrus, and fish, all of which they hunted using harpoons on the ice.<ref name="ENBR"/> Clothing consisted of robes made of wolfskin and reindeer skin to acclimate to the low temperatures.<ref>{{cite book |last=Nelson |first=Edward William |title=The Eskimo about Bering Strait |publisher=U.S. G.P.O. |date=1899}}</ref> They maintain a unique ]. | |||

| ===Greenland's Inuit=== | |||

| {{Main|Greenlandic Inuit people}} | |||

| === Greenland's Inuit === | |||

| ] make up 89% of Greenland's population.<ref> ''CIA World Factbook.'' Accessed 14 May 2014.</ref> They belong to three major groups: | |||

| {{Main|Greenlandic Inuit}} | |||

| * ] of west Greenland, who speak ] | |||

| ] make up 90% of Greenland's population.<ref name=CIAworld/> They belong to three major groups: | |||

| * ] of east Greenland, who speak ] | |||

| * ] of west Greenland, who speak ] | |||

| * ] of east Greenland, who speak ] | |||

| * ] of north Greenland, who speak ] or Polar Eskimo.<ref name="ethno"/> | * ] of north Greenland, who speak ] or Polar Eskimo.<ref name="ethno"/> | ||

| === |

=== Canadian Inuit === | ||

| {{Main|Inuit}} | {{Main|Inuit}} | ||

| Canadian Inuit live primarily in ] ( |

Canadian Inuit live primarily in ] (lit. "lands, waters and ices of the people"), their traditional homeland although some people live in southern parts of Canada. Inuit Nunangat ranges from the Yukon–Alaska border in the west across the Arctic to northern Labrador. | ||

| The ] live in the ], the northern part of ] and the ], which stretches to the ] and the ] border and includes the western ]. The land was demarked in 1984 by the Inuvialuit Final Agreement. | |||

| The majority of Inuit live in Nunavut (a ]), ] (the northern part of ]) and in ] (Inuit settlement region in ]).<ref name=statscan/><ref>{{cite web |url=https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/article/inuit-nunangat/ |title=Inuit Nunangat |access-date=April 3, 2021 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.itk.ca/inuit-nunangat-map/ |title=Map of Inuit Nunangat |date=April 4, 2019 |access-date=April 3, 2021 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://irc.inuvialuit.com/about-irc/inuvialuit-final-agreement |title=Inuvialuit Final Agreement |date=21 November 2016 |access-date=April 2, 2021 |publisher=Inuvialuit Regional Corporation}}</ref> | |||

| ===The Inuvialuit of Canada's Western Arctic=== | |||

| {{Main|Inuvialuit}} | |||

| The Inuvialuit live in the western ] region. Their homeland – the ] – covers the ] coastline area from the Alaskan border east to ] and includes the western ]. The land was demarked in 1984 by the ]. | |||

| ===Alaska's Iñupiat=== | === Alaska's Iñupiat === | ||

| {{Main|Iñupiat}} | {{Main|Iñupiat}} | ||

| ] family from ], 1929]] | ] family from ], 1929]] | ||

| The Iñupiat are the Inuit of Alaska's ] and ] boroughs and the ]s region, including the Seward Peninsula. ], the northernmost city in the United States, is above the Arctic Circle and in the Iñupiat region. Their language is known as ]. | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| The Iñupiat are Inuit of Alaska's ] and ] boroughs and the ]s region, including the Seward Peninsula.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://csalateral.org/issue/7-2/indigenous-cosmopolitanism-alaska-native-heritage-center-tyquiengco/attachment/ic_lateral2-3/|title=IC_Lateral2|journal=Lateral|year=2018}}</ref> ], the northernmost city in the United States, is above the ] and in the Iñupiat region. Their language is known as ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.alaskanativelanguages.org/inupiaq |title=Inupiatun |author=<!--Not stated--> |date=n.d. |website=Alaska Native Languages |publisher=Alaska Humanities Forum |access-date=May 8, 2021 |quote=Iñupiaq/Inupiaq is spoken by the Iñupiat/Inupiat on the Seward Peninsula, the Northwest Arctic and the North Slope of Alaska and in Western Canada. |archive-date=May 10, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210510143606/https://www.alaskanativelanguages.org/inupiaq |url-status=dead }}</ref> Their current communities include 34 villages across ''Iñupiat Nunaŋat'' (Iñupiaq lands) including seven ] in the ], affiliated with the ]; eleven villages in ]; and sixteen villages affiliated with the ].<ref name=medicine> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140821193420/http://www.nnlm.nlm.nih.gov/archive/20061109155450/inupiaq.html |date=2014-08-21 }} ''National Network of Libraries of Medicine.'' Retrieved 4 Dec 2013.</ref> | |||

| ==Yupik== | |||

| {{Main| Yupik peoples}} | |||

| The Yupik are indigenous or aboriginal peoples who live along the coast of western Alaska, especially on the ]-] delta and along the Kuskokwim River (]); in southern Alaska (the ]); and along the eastern coast of ] in the Russian Far East and ] in western Alaska (the ]). The Yupik economy has traditionally been strongly dominated by the harvest of ]s, especially ], ], and ]s.<ref>"Yupik". (2008). In ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved January 13, 2008, from: Retrieved August 30, 2012.</ref> | |||

| == |

== Yupik == | ||

| {{Main| |

{{Main|Yupik peoples}} | ||

| ] dancer during the biennial "Celebration" cultural event]] | ] dancer during the biennial "Celebration" cultural event]] | ||

| The Alutiiq, also called ''Pacific Yupik'' or ''Sugpiaq'', are a southern, coastal branch of Yupik. They are not to be confused with the Aleut, who live further to the southwest, including along the ]. They traditionally lived a coastal lifestyle, subsisting primarily on ocean resources such as ], ], and whales, as well as rich land resources such as berries and land mammals. Alutiiq people today live in coastal fishing communities, where they work in all aspects of the modern economy. They also maintain the cultural value of subsistence. | |||

| The Yupik are indigenous or aboriginal peoples who live along the coast of western Alaska, especially on the ]-] delta and along the Kuskokwim River (]); in southern Alaska (the ]); and along the eastern coast of ] in the Russian Far East and ] in western Alaska (the ]).<ref>{{Cite web |title=Facts for Kids: Yup'ik People (Yupik) |url=http://www.bigorrin.org/yupik_kids.htm |access-date=June 20, 2020 |website=www.bigorrin.org}}</ref> The Yupik economy has traditionally been strongly dominated by the harvest of ]s, especially ], ], and ]s.<ref>"Yupik". (2008). In ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved January 13, 2008, from: Retrieved August 30, 2012.</ref> | |||

| The Alutiiq language is relatively close to that spoken by the Yupik in the ] area. But, it is considered a distinct language with two major dialects: the Koniag dialect, spoken on the ] and on ], and the Chugach dialect, spoken on the southern ] and in ]. Residents of ], located on southern part of the Kenai Peninsula near ], speak what they call Sugpiaq. They are able to understand those who speak Yupik in Bethel. With a population of approximately 3,000, and the number of speakers in the hundreds, Alutiiq communities are working to revitalize their language.{{Citation needed|date=September 2011}} | |||

| === |

=== Alutiiq === | ||

| {{Excerpt|Alutiiq|paragraph=1,2}} | |||

| {{Main|Central Alaskan Yup'ik people}} | |||

| ''Yup'ik'', with an apostrophe, denotes the speakers of the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, who live in western Alaska and southwestern Alaska from southern Norton Sound to the north side of ], on the ], and on ]. The use of the apostrophe in the name ''Yup'ik'' is a written convention to denote the long pronunciation of the ''p'' sound; but it is spoken the same in other Yupik languages. Of all the ], Central Alaskan Yup'ik has the most speakers, with about 10,000 of a total Yup'ik population of 21,000 still speaking the language. The five dialects of Central Alaskan Yup'ik include General Central Yup'ik, and the Egegik, Norton Sound, Hooper Bay-Chevak, and Nunivak dialects. In the latter two dialects, both the language and the people are called ''Cup'ik''.<ref name="centralyup'ik">Alaska Native Language Center. (2001-12-07). , ], ]. Retrieved on 2007-04-06.</ref> | |||

| The Alutiiq language is relatively close to that spoken by the Yupik in the ] area. But, it is considered a distinct language with two major dialects: the Koniag dialect, spoken on the ] and on ], and the Chugach dialect, spoken on the southern ] and in ]. Residents of ], located on southern part of the Kenai Peninsula near ], speak what they call Sugpiaq. They are able to understand those who speak Yupik in Bethel. With a population of approximately 3,000, and the number of speakers in the hundreds, Alutiiq communities are working to revitalize their language.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://alutiiqmuseum.org/learn/the-alutiiq-sugpiaq-people/language/906-language-loss-revitalization |title=Language Loss & Revitalization |website=alutiiqmuseum.org |language=en-gb |access-date=June 12, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| === Central Alaskan Yup'ik === | |||

| {{Main|Yup'ik}} | |||

| ''Yup'ik'', with an apostrophe, denotes the speakers of the Central Alaskan ], who live in western Alaska and southwestern Alaska from southern ] to the north side of ], on the ], and on ]. The use of the apostrophe in the name ''Yup'ik'' is a written convention to denote the long pronunciation of the ''p'' sound; but it is spoken the same in other ]. Of all the ], Central Alaskan Yup'ik has the most speakers, with about 10,000 of a total Yup'ik population of 21,000 still speaking the language. The five dialects of Central Alaskan Yup'ik include General Central Yup'ik, and the Egegik, Norton Sound, Hooper Bay-Chevak, and Nunivak dialects. In the latter two dialects, both the language and the people are called ''Cup'ik''.<ref name="centralyup'ik">{{cite web |publisher=Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks. |url=https://uaf.edu/anlc/languages/centralakyupik.php |title=Central Alaskan Yup'ik |access-date=April 3, 2021 |archive-date=April 11, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210411035617/https://www.uaf.edu/anlc/languages/centralakyupik.php}}</ref> | |||

| ===Siberian Yupik=== | ===Siberian Yupik=== | ||

| {{Main|Siberian Yupik}} | {{Main|Siberian Yupik}} | ||

| ] aboard the steamer ''Bowhead'']] | |||

| Siberian Yupik reside along the Bering Sea coast of the ] in Siberia in the Russian Far East<ref name="kaplanB"/> and in the villages of ] and ] on St. Lawrence Island in Alaska.<ref name="siberianyupik">Alaska Native Language Center. (2001-12-07). ], ]. Retrieved on August 30, 2012.</ref> The Central Siberian Yupik spoken on the Chukchi Peninsula and on St. Lawrence Island is nearly identical. About 1,050 of a total Alaska population of 1,100 Siberian Yupik people in Alaska speak the language. It is the first language of the home for most St. Lawrence Island children. In Siberia, about 300 of a total of 900 Siberian Yupik people still learn and study the language, though it is no longer learned as a first language by children.<ref name="siberianyupik"/> | |||

| Siberian Yupik reside along the Bering Sea coast of the ] in Siberia in the Russian Far East<ref name="kaplanB"/> and in the villages of ] and ] on St. Lawrence Island in Alaska.<ref name="siberianyupik">{{cite web|url=https://uaf.edu/anlc/languages/siberianyupik.php|title=Siberian Yupik|publisher=Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks|access-date=April 3, 2021|archive-date=May 8, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210508075538/https://www.uaf.edu/anlc/languages/siberianyupik.php}}</ref> The Central Siberian Yupik spoken on the Chukchi Peninsula and on St. Lawrence Island is nearly identical. About 1,050 of a total Alaska population of 1,100 Siberian Yupik people in Alaska speak the language. It is the first language of the home for most St. Lawrence Island children. In Siberia, about 300 of a total of 900 Siberian Yupik people still learn and study the language, though it is no longer learned as a first language by children.<ref name="siberianyupik"/> | |||

| ===Naukan=== | ===Naukan=== | ||

| {{Main|Naukan people|Naukan language}} | {{Main|Naukan people|Naukan Yupik language}} | ||

| About 70 of 400 Naukan people still speak Naukanski. The Naukan originate on the Chukot Peninsula in ] in Siberia.<ref name="kaplanB"/> | |||

| About 70 of 400 Naukan people still speak Naukanski. The Naukan originate on the Chukot Peninsula in ] in Siberia.<ref name="kaplanB"/> Despite the relatively small population of Naukan speakers, documentation of the language dates back to 1732. While Naukan is only spoken in Siberia, the language acts as an intermediate between two Alaskan languages: Siberian Yupik Eskimo and Central Yup'ik Eskimo.<ref name="erudit.org"/> | |||

| ==Sirenik Eskimos== | ==Sirenik Eskimos== | ||

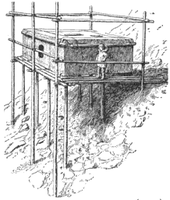

| ]]] | |||

| {{Main|Sirenik Eskimos}} | {{Main|Sirenik Eskimos}} | ||

| ]]] | |||

| Some speakers of Siberian Yupik languages used to speak an Eskimo variant in the past, before they underwent a ]. These former speakers of Sirenik Eskimo language inhabited the settlements of Sireniki, <!--This is the correct spelling as per the source. Please don't use AWB to change it. Thanks.-->Imtuk, and some small villages stretching to the west from Sireniki along south-eastern coasts of Chukchi Peninsula.<ref name=VES>: 162</ref> They lived in neighborhoods with Siberian Yupik and ]s. | |||

| Some speakers of Siberian Yupik languages used to speak an Eskimo variant in the past, before they underwent a ]. These former speakers of ] inhabited the settlements of ], <!--This is the correct spelling as per the source. Please don't use AWB to change it. Thanks.-->Imtuk, and some small villages stretching to the west from Sireniki along south-eastern coasts of Chukchi Peninsula.<ref name=VES>: 162</ref> They lived in neighborhoods with Siberian Yupik and ]s. | |||

| As early as in 1895, <!--This is the correct spelling as per the source. Please don't use AWB to change it. Thanks.-->Imtuk was |

As early as in 1895, <!--This is the correct spelling as per the source. Please don't use AWB to change it. Thanks.-->Imtuk was a settlement with a mixed population of Sirenik Eskimos and Ungazigmit<ref>Menovshchikov 1964: 7</ref> (the latter belonging to Siberian Yupik). Sirenik Eskimo culture has been influenced by that of Chukchi, and the language shows ] influences.<ref name=linfranc>: 70</ref> Folktale ] also show the influence of Chuckchi culture.<ref name=rein-rape>Menovshchikov 1964: 132</ref> | ||

| The above peculiarities of this (already ]) Eskimo language amounted to mutual unintelligibility even with its nearest language relatives:<ref> |

The above peculiarities of this (already ]) Eskimo language amounted to mutual unintelligibility even with its nearest language relatives:<ref>Menovshchikov 1964: 6–7</ref> in the past, Sirenik Eskimos had to use the unrelated Chukchi language as a ] for communicating with Siberian Yupik.<ref name=linfranc/> | ||

| Many words are formed from entirely different ]s |

Many words are formed from entirely different ]s from in Siberian Yupik,<ref name=diff-root>Menovshchikov 1964: 42</ref> but even the grammar has several peculiarities distinct not only among Eskimo languages, but even compared to Aleut. For example, ] is not known in Sirenik Eskimo, while most ] have dual,<ref name=only2>Menovshchikov 1964: 38</ref> including its neighboring Siberian Yupikax relatives.<ref name=verb2>Menovshchikov 1964: 81</ref> | ||

| Little is known about the origin of this diversity. The peculiarities of this language may be the result of a supposed long isolation from other Eskimo groups,<ref> |

Little is known about the origin of this diversity. The peculiarities of this language may be the result of a supposed long isolation from other Eskimo groups,<ref>Menovshchikov 1962: 11</ref><ref>Menovshchikov 1964: 9</ref> and being in contact only with speakers of unrelated languages for many centuries. The influence of the Chukchi language is clear.<ref name=linfranc/> | ||

| Because of all these factors, the classification of Sireniki Eskimo language is not settled yet:<ref name=VE3>: 161</ref> Sireniki language is sometimes regarded as a third branch of Eskimo (at least, its possibility is mentioned).<ref name="VE3"/><ref name=Vakh-Sir>Linguist List's description about 's book: . The author's untransliterated (original) name is |