| Revision as of 05:32, 12 May 2019 editNkhensa (talk | contribs)336 editsNo edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:13, 9 November 2024 edit undoKku (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users115,679 editsm link overgrazing | ||

| (122 intermediate revisions by 85 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Mountain range in South Africa}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=May 2013}} | {{Use British English|date=May 2013}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2019}} | |||

| {{Infobox mountain | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2013}} | |||

| <!-- *** Heading *** -->| name = uKhahlamba | |||

| | native_name = {{native name list |tag1=st|name1=Maloti |tag2=zu|name2=uKhahlamba}} | |||

| {{Infobox mountain range | |||

| <!-- *** Names **** -->| etymology = Dragon's Mountain (modern day) and Crazy Carriers Mountain from ] (historical) | |||

| <!-- *** Heading *** --> | |||

| | |

<!-- *** Image *** -->| photo = South Africa - Drakensberg (16261357780).jpg | ||

| | photo_caption = <!-- *** Country *** --> | |||

| | native_name = {{plainlist| | |||

| | country = {{hlist|]|]|}} | |||

| *{{native_name|sot|Maluti}} | |||

| <!-- *** Locations *** -->| highest = ] | |||

| *{{native_name|zul|uKhahlamba}} | |||

| }} | |||

| <!-- *** Names **** --> | |||

| | etymology = Dragon's mountain | |||

| <!-- *** Image *** --> | |||

| | photo = South Africa - Drakensberg (16261357780).jpg | |||

| | photo_caption = | |||

| <!-- *** Country *** --> | |||

| | country = ] | |||

| | country1 = ] | |||

| <!-- *** Locations *** --> | |||

| | highest = ] | |||

| | elevation_m = 3482 | | elevation_m = 3482 | ||

| | elevation_note = <!-- lowest elevation is 560 m --> | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|29|23|S|29|27|E|type:mountain|format=dms|display=inline,title}} | | coordinates = {{coord|29|23|S|29|27|E|type:mountain|format=dms|display=inline,title}} | ||

| <!-- *** Dimensions *** -->| length_km = 1000 | |||

| | coordinates_note = | |||

| | length_orientation = SW to NE | |||

| <!-- *** Dimensions *** --> | |||

| | length_ref = | |||

| | length_km = 1000 | length_orientation = SW to NE | length_note = | |||

| | width_km = | width_orientation = | |

| width_km = | ||

| | width_orientation = | |||

| | width_ref = | |||

| | range_coordinates = | | range_coordinates = | ||

| | range_coordinates_ref = <!-- *** Features *** --> | |||

| | range_coordinates_note = | |||

| | geology = {{hlist|Basalt|Quartzite}} | |||

| <!-- *** Features *** --> | |||

| | orogeny = <!-- *** Maps *** --> | |||

| | geology = Basalt | |||

| | |

| map = | ||

| | |

| map_caption = | ||

| | period = | |||

| <!-- *** Maps *** --> | |||

| | map = | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Drakensberg''' ( |

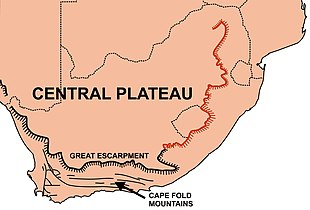

The '''Drakensberg''' (]: uKhahlamba, ]: Maloti, ]: Drakensberge) is the eastern portion of the ], which encloses the central ] plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – {{convert|2000|to|3482|m|ft|abbr=off}} within the border region of ] and ]. | ||

| ] to the south. The portion of the ] shown in red is known as the Drakensberg.]] | ] to the south. The portion of the ] shown in red is known as the Drakensberg.]] | ||

| The Drakensberg escarpment stretches for |

The Drakensberg escarpment stretches for more than {{convert|1000|km|mi|sigfig=1|abbr=off}} from the ] in the South, then successively forms, in order from south to north, the border between ] and the ] and the border between Lesotho and ]. Thereafter it forms the border between KwaZulu-Natal and the ], and next as the border between KwaZulu-Natal and ]. The escarpment winds north from there, through Mpumalanga, where it includes features such as the ], ], and ]. It then extends farther north to ] in southeastern Limpopo where it is known as 'Klein Drakensberg' by the ]. From Hoedspruit it extends west to ], also in ], where it is known as the ] ] and Iron Crown Mountain. At {{convert|2200|m|ft|abbr=on}} above sea level, the Wolkberg is the highest elevation in Limpopo. The escarpment extends west again and at ] it is known as the Strydpoort Mountains.<ref name= "Atlas">{{cite book|title=Reader's Digest Atlas of Southern Africa|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LJPctAEACAAJ|year=1984|publisher=Reader's Digest Association South Africa|pages=13, 190–192|location=Cape Town}}</ref><ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (1975); ''Micropaedia'' Vol. III, p. 655. Helen Hemingway Benton Publishers, Chicago.</ref> | ||

| == Etymology == | == Etymology == | ||

| The ] name ''Drakensberge'' comes from the name the earliest ] settlers to the |

The ] name ''Drakensberge'' comes from the name the earliest ] settlers gave to the escarpment, namely ''Drakensbergen'', or ''Dragons' Mountains''. The highest portion of the Great Escarpment is known in ] as ''uKhahlamba'' and as ''Maloti'' in ] ("Barrier of up-pointed spears").<ref name=Pearse>{{cite book|last=Pearse|first=Reg O.|title=Barrier of Spears: Drama of the Drakensberg|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ri6KQgAACAAJ|year=1973|publisher=H. Timmins|isbn=978-0-86978-050-3|page=i}}</ref> | ||

| == Geology== | |||

| When most South Africans and visitors speak of ''the'' Drakensberg, they refer to the Great Escarpment that forms the border between Lesotho and KwaZulu-Natal, believing it to be a range of mountains extending into Lesotho, more correctly known as the ]. This highest portion of the Great Escarpment is known as ''uKhahlamba'' ("Barrier of up-pointed spears")<ref name=Pearse>{{cite book|last=Pearse|first=Reg O.|title=Barrier of Spears: Drama of the Drakensberg|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ri6KQgAACAAJ|year=1973|publisher=H. Timmins|isbn=978-0-86978-050-3|page=i}}</ref> in ] and ''Maluti'' in ]. | |||

| ===Origins=== | |||

| {{Further|Great Escarpment, Southern Africa}} | |||

| The Great Escarpment is composed of steep ] walls formed around a bulging of continental crust during the breakup of southern ] that have since eroded inland from their original positions near the southern African coast, and its entire eastern portion (see the accompanying map) constitutes the Drakensberg.<ref name="Atlas" /><ref>{{cite book|title=The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KtBxcgAACAAJ|year=1999|publisher=Times Books|location=London|page=90|isbn = 9780007419135}}</ref><ref name=mccarthy>{{cite book|last1=McCarthy|first1=Terence|last2=Rubidge|first2=Bruce|title=The Story of Earth & Life: A Southern Africa Perspective on a 4.6 Billion-year Journey|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YEa9tNO2qOcC|year=2005|publisher=Penguin Random House South Africa|isbn=978-1-77007-148-3|pages=16–7, 192–195, 245–248, 263, 267–269|location=Cape Town}}{{Dead link|date=February 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> The Drakensberg terminate in the north near Tzaneen at about the 22° S parallel. The absence of the Great Escarpment for approximately {{convert|450|km|abbr=on}} to the north of Tzaneen (to reappear on the border between ] and ] in the ]) is due to a failed westerly branch of the main rift that caused ] to start drifting away from southern Africa during the breakup of Gondwana about 150 million years ago. The lower ] and ] drain into the ] through what remains of this relict incipient rift valley, which now forms part of the South African ].<ref name=mccarthy /> | |||

| During the past 20 million years, southern Africa has experienced massive uplifting, especially in the east, with the result that most of the plateau lies above {{convert|1000|m|ft|abbr=on}} despite extensive erosion. The plateau is tilted such that it is highest in the east and slopes gently downward toward the west and south. Typically, the elevation of the edge of the eastern escarpments is in excess of {{convert|2000|m|ft|abbr=on}}. It reaches its highest point of over {{convert|3000|m|ft|abbr=on}} where the escarpment forms part of the international border between ] and the South African province of ].<ref name="Atlas" /><ref name=mccarthy /> | |||

| == Geological origins == | |||

| === Appearance === | |||

| About 180 million years ago, a ] under southern ] caused bulging of the continental crust in the area that would later become southern Africa.<ref name=mccarthy>{{cite book|last1=McCarthy|first1=Terence |last2=Rubidge|first2=Bruce |title=The Story of Earth & Life: A Southern Africa Perspective on a 4.6 Billion-year Journey|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YEa9tNO2qOcC|year=2005|publisher=Penguin Random House South Africa|isbn=978-1-77007-148-3|pages=16–7, 192–195, 245–248, 263, 267–269|location=Cape Town}}</ref> Within 10–20 million years ]s formed on either side of the central bulge, which became flooded to become the proto-Atlantic and proto-Indian oceans.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name=truswell>{{cite book|last=Truswell|first=J. F. |title=The Geological Evolution of South Africa|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5gq0AAAAIAAJ|year=1977|publisher=Alice Kelly Purnell|location=Cape Town|pages=151–153, 157–159, 184–188, 190}}</ref> The stepped steep walls of these rift valleys formed escarpments that surrounded the newly formed Southern African subcontinent.<ref name=mccarthy /> | |||

| With the widening of the Atlantic, Indian and Southern oceans, Southern Africa became tectonically quiescent. Earthquakes rarely occur, and there has been no volcanic or ] for about 50 million years.<ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (1975); ''Macropaedia,'' Vol. 17. p. 60. Helen Hemingway Benton Publishers, Chicago.</ref> An almost uninterrupted period of erosion has continued to the present, resulting in layers several kilometers thick having been lost from the surface of the plateau.<ref name=mccarthy /> A thick layer of marine sediment was consequently deposited onto the continental shelf (the lower steps of the original rift valley walls) which surrounds the subcontinent.<ref name=truswell /> | |||

| ] (with ]) on the far left, and north-eastern ] on the right, is diagrammatic and only roughly to scale. It shows how the '''Drakensberg Escarpment''' is related to the major geographical features that dominate the southern and eastern parts of the country, particularly the Central Plateau, whose southwestern edge (in the diagram) is called the Roggeberg escarpment (not labelled). The major geological layers that shape this geography are indicated in different colors whose significance and origin are explained under the headings "]" and "]". The 1600 m thick layer of hard, erosion-resistant basalt (lava) that accounts for the height and steepness of the Drakensberg Escarpment on the KwaZuluNatal-Lesotho border is indicated in blue. Immediately below it is the ] shown in green. The Clarence Formation with its numerous caves and ], forms part of this latter group.]] | |||

| During the past 20 million years, further massive upliftment, especially in the East, has taken place in Southern Africa. As a result, most of the plateau lies above {{convert|1000|m|ft|abbr=on}} despite the extensive erosion. The plateau is tilted such that its highest point is in the east, and it slopes gently downwards towards the west and south. The elevation of the edge of the eastern escarpments is typically in excess of {{convert|2000|m|ft|abbr=on}}. It reaches its highest point (over {{convert|3000|m|ft|abbr=on}}) where the escarpment forms part of the international border between Lesotho and the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name= "Atlas" /> | |||

| The escarpment seen from below resembles a range of mountains. The Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and Lesotho Drakensberg have hard erosion-resistant upper surfaces and therefore have a very rugged appearance, combining steep-sided blocks and pinnacles (giving rise to the Zulu name "Barrier of up-pointed spears"). Who first gave these mountains their Afrikaans or Dutch name ''Drakensberg'', and why, is unknown.<ref name=Pearse /> The KwaZulu-Natal – Free State Drakensberg are composed of softer rocks and therefore have a more rounded, softer appearance from below. Generally, the top of the escarpment is almost table-top flat and smooth, even in Lesotho. The "Lesotho Mountains" are formed away from the Drakensberg escarpment by erosion gulleys which turn into deep valleys containing tributaries of the ]. The large number of such tributaries give the ] a very rugged mountainous appearance, both from the ground and from the air. | |||

| The higher parts of Drakensberg have a mildly ]. It is possible that recent ] has diminished the intensity of periglaciation.<ref name=Knightetal2018>{{cite journal |last1=Knight |first1=Jasper |last2=Grab |first2=Stefan W.|last3=Carbutt |first3=Clinton |date=2018 |title=Influence of mountain geomorphology on alpine ecosystems in the Drakensberg Alpine Centre, Southern Africa |journal=] |volume=100 |issue=2 |pages=140–162 |doi=10.1080/04353676.2017.1418628 |s2cid=134848291 }}</ref> | |||

| The upliftment of the central plateau over the past 20 million years and erosion resulted in the original escarpment being moved inland, creating the present-day coastal plain.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name= McCarthy>{{cite journal|last1=McCARTHY|first1=T. S.|title=The Okavango Delta and its Place in the Geomorphological Evolution of Southern Africa|journal=South African Journal of Geology|volume=116|issue=1|year=2013|pages=1–54|issn=1012-0750|doi=10.2113/gssajg.116.1.1}}</ref><ref name=norman>{{cite book|last1=Norman|first1=Nick|last2=Whitfield|first2=Gavin |title=Geological Journeys: A Traveller's Guide to South Africa's Rocks and Landforms|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_uDcm-olXE8C|year=2006|publisher=Penguin Random House South Africa|isbn=978-1-77007-062-2|pages=290–300}}</ref> The position of the present escarpment is approximately {{convert|150|km}} inland from the original fault lines which formed the walls of the rift valley that developed along the coast during the break-up of Gondwana. The rate of the erosion of the escarpment in the Drakensberg region is said to average {{convert|1.5|m|ft|abbr=on|0}} per 1000 years, or {{convert|1.5|mm|in|frac=16}} per year.<ref name=norman /> | |||

| Knight and Grab mapped out the distribution of lightning strikes in the Drakensburg and discovered that lightning significantly controls the evolution of the mountain landscapes because it helps to shape the summit areas – the highest areas – with this blasting effect. Previously, angular debris was presumed to have been created by changes typical of cold, periglacial environments, such as fracturing due to frost.<ref name="Foss2013">{{Cite web |title=New evidence on lightning strikes: Mountains a lot less stable than we think |last=Foss |first=Kanina |work=phys.org |date=15 October 2013 |access-date=3 May 2019 |url= https://phys.org/news/2013-10-evidence-lightning.html }}</ref> | |||

| Because of the extensive erosion of the plateau, which occurred over most of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras, none of its surface rocks (except the Kalahari sands) are younger than 180 million years.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name="geological map">''Geological map of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland ''(1970). Council for Geoscience, Geological Survey of South Africa.</ref> The youngest rocks that remain cap the plateau in Lesotho. These are the ] laid down under desert conditions about 200 million years ago, topped by a ] which erupted, and covered most of Southern Africa, and large parts of Gondwana, about 180 million years ago.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name=truswell /><ref name="Drakensberg Guide">{{cite book|last=Sycholt|first=August |editor=Roxanne Reid|title=A Guide to the Drakensberg|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bFo7ytU8OnUC|year=2002|publisher=Struik Publishers|location=Cape Town|isbn=978-1-86872-593-9|page=9}}</ref> These rocks form the steep sides of the Great Escarpment in this region, where its upper edge reaches an elevation in excess of {{convert|3000|m|ft|abbr=on}}. | |||

| === Composition === | |||

| The erosional retreat of the escarpment from the coast to its present position, means that the rocks of the coastal plain are, with very few and small exceptions, older than those that cap the top of the escarpment. Thus the rocks of the Mpumalanga ] below the Mpumalanga portion of the Great Escarpment are more than 3000 million years old.<ref name="geological map" /> The rocks of the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands belong, in the main, to the Beaufort and Ecca Groups (of the ]), aged 220–310 million years, and are therefore considerably older than the Drakensberg lavas (aged 180 million years) which cap the escarpment on the border between KwaZulu-Natal and Lesotho.<ref name="geological map" /> | |||

| The geological composition of Drakensberg (escarpment wall) varies considerably along its more than 1000 km length. The Limpopo and Mpumalanga Drakensberg are capped by an erosion resistant quartzite layer that is part of the Transvaal Supergroup, which also forms the ] to the north and northwest of Pretoria.<ref name=mccarthy /> These rocks are more than 2000 million years old. South of the 26°S parallel the Drakensberg escarpment is composed of ], which belong to the ], and they are 300 million years old.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name="geological map">''Geological map of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland ''(1970). Council for Geoscience, Geological Survey of South Africa.</ref> The portion of the Drakensberg that forms the KwaZulu-Natal – Free State border is formed by slightly younger ] (250 million years old) that also are part of the Karoo Supergroup. | |||

| The entire eastern portion of the Great Escarpment (see the accompanying map) constitutes the Drakensberg.<ref name="Atlas" /><ref>{{cite book|title=The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KtBxcgAACAAJ|year=1999|publisher=Times Books|location=London|page=90}}</ref> The Drakensberg terminate in the north near Tzaneen at about the 22° S parallel. The absence of the Great Escarpment for about {{convert|450|km|abbr=on}} to the north of Tzaneen (to reappear on the border between ] and ] in the ] Highlands) is due to a failed westerly branch of the main rift that caused ] to start drifting away from Southern Africa during the breakup of Gondwana about 150 million years ago. The lower ] and ] drain into the ] through what remains of this relict incipient rift valley which now forms part of the ].<ref name=mccarthy /> | |||

| The Ecca and Beaufort groups are composed of sedimentary rocks that are less erosion resistant than the other rocks that make up the Drakensberg escarpment. Therefore, this portion of escarpment is not so impressive as the Mpumalanga and Lesotho stretches of the Drakensberg. The Drakensberg that form the northeastern and eastern borders of Lesotho, as well as the Eastern Cape Drakensberg, are composed of a thick layer of basalt (lava) that erupted 180 million years ago.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name="geological map" /> That layer rests on the youngest of the Karoo Supergroup sediments, the ], which was laid down under desert conditions, about 200 million years ago.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name="geological map" /> | |||

| == History == | |||

| Caves are frequent in the more easily eroded sandstone, and many have rock paintings by the ]. The Drakensberg contains thousands of works of ] and is the largest collection of such work in the world. These paintings are considered to be unique mainly because they represent the earliest specimens of rock art where color and dimension were introduced. Due to the materials used in their production, these paintings are difficult to date, but there is anthropological evidence, including many hunting implements, that their civilization existed in the Drakensberg at least 40,000 years ago and possibly over 100,000 years ago. | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| The Bushman population was decimated in various wars from the 17th century, mostly between them and other African tribes invading the fertile area. Ultimately they were completely annihilated by Europeans in the 19th century, due principally to confusion over claims to land and hunting animals. Being ], the Bushman did not believe in ownership of ] but did believe strongly in hunting grounds (the opposite of the view held by Europeans). Thus the Bushman would hunt European livestock, and the Europeans would infringe on hunting grounds, neither with a concept that they were transgressing a rule of the other. Both sides responded, with Bushmen raiding the Europeans and Europeans attacking the Bushmen. The superior technology of the European guns and weapons spelled certain disaster for the Bushman, and the last one was seen in the late 19th century. There are still Bushmen tribes dwelling in the ] and ] deserts, but the culture of mountain Bushmen no longer exists. | |||

| === Peaks === | |||

| The highest peak is ], at {{convert|3482|m|ft|abbr=on}}. Other notable peaks include ] ({{convert|3450|m|ft|0|abbr=on}}), ] at {{convert|3416|m}}, ] at {{convert|3408|m}}, ] at {{convert|3377|m}}, ] at {{convert|3315|m}}, ] at {{convert|3001|m}}, and ] at {{convert|3331|m}}, all of these are in the area bordering on Lesotho, which contains an area popular for hikers, ]. North of Lesotho the range becomes lower and less rugged until entering Mpumalanga where the quartzite mountains of the Transvaal Drakensberg are loftier and more broken and they form the eastern rim of the Transvaal Basin, the ] lying within this stretch. The geology of this section is the same as, and continuous with, that of the ]. | |||

| == Geomorphology == | |||

| === |

=== Mountain passes === | ||

| ] (with ]) on the far left, and north-eastern ] on the right. Diagrammatic and only roughly to scale. It shows how the '''Drakensberg Escarpment''' is related to the major geographical features that dominate the southern and eastern parts of the country, particularly the Central Plateau, whose south-western edge (in the diagram) is called the Roggeberg escarpment (not labelled). The major geological layers that shape this geography are indicated in different colors, whose significance and origin are explained under the headings "]" and "]". The 1600 m thick layer of hard, erosion-resistant basalt (lava) that accounts for the height and steepness of the Drakensberg Escarpment on the KwaZuluNatal-Lesotho border is indicated in blue. Immediately below it is the ] shown in green. The Clarence Formation with its numerous caves and San rock paintings, forms part of this latter group.]]The escarpment seen from below looks like a range of mountains. The Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Lesotho Drakensberg have hard erosion-resistant upper surfaces and therefore have a very rugged appearance, combining steep-sided blocks and pinnacles (giving rise to the Zulu name "Barrier of up-pointed spears"). Who first gave these mountains their Afrikaans or Dutch name ''Drakensberg'', and why, is unknown.<ref name=Pearse />). The KwaZulu-Natal – Free State Drakensberg are composed of softer rocks and therefore have a more rounded, softer appearance from below. The top of the escarpment is generally almost table-top flat and smooth, even in Lesotho. The "Lesotho Mountains" are formed away from the Drakensberg escarpment by erosion gulleys which turn into deep valleys which contain tributaries of the ]. The large number of tributaries give the ] a very rugged mountainous appearance, both from the ground and from the air. | |||

| The higher parts of Drakensberg has a mildly ]. It is possible that recent ] has diminished the intensity of periglaciation.<ref name=Knightetal2018>{{cite journal |last1=Knight |first1=Jasper |last2=Grab |first2=Stefan W.|last3=Carbutt |first3=Clinton |date=2018 |title=Influence of mountain geomorphology on alpine ecosystems in the Drakensberg Alpine Centre, Southern Africa |url= |journal=] |volume= |issue= |pages= |doi=10.1080/04353676.2017.1418628 |access-date= }}</ref> | |||

| Knight and Grab mapped out the distribution of lightning strikes in the Drakensburg and discovered that lightning significantly controls the evolution of the mountain landscapes because it helps to shape the summit areas – the highest areas – with this blasting effect. Previously, angular debris was assumed to have been created by changes typical of cold, periglacial environments, such as fracturing due to frost.<ref name="Foss2013">{{Cite web |title=New evidence on lightning strikes: Mountains a lot less stable than we think |last=Foss |first=Kanina |work=phys.org |date=15 October 2013 |access-date=3 May 2019 |url= https://phys.org/news/2013-10-evidence-lightning.html |language= |quote=}}</ref> | |||

| === Composition of rocks === | |||

| The geological composition of Drakensberg (escarpment wall) varies considerably along its more than 1000 km length. The Limpopo and Mpumalanga Drakensberg are capped by an erosion resistant quartzite layer which is part of the Transvaal Supergroup which also forms the ] to the north and northwest of Pretoria.<ref name=mccarthy /> These rocks are more than 2000 million years old. South of the 26°S parallel the Drakensberg escarpment is composed of ], which belong to the ], which are 300 million years old.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name="geological map" /> The portion of the Drakensberg that forms the KwaZulu-Natal – Free State border is formed by slightly younger ] (250 million years old) which are also part of the Karoo Supergroup. The Ecca and Beaufort groups are composed of sedimentary rocks which are less erosion resistant than the other rocks which make up the Drakensberg escarpment. This portion of escarpment is therefore not as impressive as the Mpumalanga and Lesotho stretches of the Drakensberg. The Drakensberg which form the north-eastern and eastern borders of Lesotho, as well as the Eastern Cape Drakensberg are composed of a thick layer of basalt (lava) which erupted 180 million years ago.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name="geological map" /> That rests on the youngest of the Karoo Supergroup sediments, the ], which was laid down under desert conditions, about 200 million years ago.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name="geological map" /> | |||

| == Highest peaks == | |||

| The highest peak is ], at {{convert|3482|m|ft|abbr=on}}. Other notable peaks include ] ({{convert|3450|m|ft|0|abbr=on}}), ] at {{convert|3416|m}}, ] at {{convert|3408|m}}, ] at {{convert|3377|m}}, ] at {{convert|3315|m}}, ] at {{convert|3001|m}}, and ] at {{convert|3331|m}}, all of these are in the area bordering on Lesotho. Another popular area for hikers is ]. North of Lesotho the range becomes lower and less rugged until entering Mpumalanga where the quartzite mountains of the Transvaal Drakensberg are loftier and more broken and form the eastern rim of the Transvaal Basin, the ] lying within this stretch. The geology of this section is the same as and continuous with that of the ]. | |||

| == Mountain passes == | |||

| {{Main article|List of mountain passes of KwaZulu-Natal}} | {{Main article|List of mountain passes of KwaZulu-Natal}} | ||

| Line 96: | Line 70: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The high treeless peaks of the Drakensberg (from {{convert| |

The high treeless peaks of the Drakensberg (from {{convert|2500|m|ft|abbr=on}} upward) have been described by the ] as the ''Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands'' ]. These steep slopes are the most southerly high mountains in Africa, and being farther from the equator provide cooler habitats at lower elevations than most mountain ranges on the continent. High rainfall generates many mountain streams and rivers, including the sources of the ], southern Africa's longest, and the ]. | ||

| These mountains also have the world's highest waterfall, the ] (Thukela Falls), which has a total drop of {{convert|947|m|ft|abbr=on}} (Venezuela's Angel Falls is also a candidate for highest waterfall). The rivers that run from the Drakensberg are an essential resource for South Africa's economy, providing water for the industrial provinces of Mpumalanga and ], which contains the city of ].<ref>{{WWF ecoregion|id=at1003|name=Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands}}</ref> The climate is wet and cool at the high elevations, which experience snowfall in winter. | |||

| Meanwhile, the grassy lower slopes (from {{convert|1,800|to|2500|m|ft|abbr=on}}) of the Drakensberg in ], South Africa and Lesotho constitute the ''Drakensberg Montane Grassland, Woodland, and Forest''. | |||

| The grassy lower slopes (from {{convert|1800|to|2500|m|ft|abbr=on}}) of the Drakensberg in ], South Africa and Lesotho constitute the ''Drakensberg montane grasslands, woodlands, and forests'' ecoregion. | |||

| === Flora === | === Flora === | ||

| Line 105: | Line 81: | ||

| The mountains are rich in plant life, including a large number of species listed in the Red Data Book of threatened plants, with 119 species listed as globally endangered and "of the 2 153 plant species in the park, a remarkable 98 are endemic or near-endemic".<ref name="Barrier of Spears" /> | The mountains are rich in plant life, including a large number of species listed in the Red Data Book of threatened plants, with 119 species listed as globally endangered and "of the 2 153 plant species in the park, a remarkable 98 are endemic or near-endemic".<ref name="Barrier of Spears" /> | ||

| The ''flora of the high alti-montane grasslands'' is mainly ], creeping plants, and small shrubs such as ]s. These include the rare Spiral Aloe ''(])'', which as its name suggests has leaves with a spiral shape. | The ''flora of the high alti-montane grasslands'' is mainly ], creeping plants, and small shrubs such as ]s. These include the rare Spiral Aloe ''(])'', which as its name suggests, has leaves with a spiral shape. | ||

| Meanwhile, the ''lower slopes'' are mainly grassland but are also home to ]s, which are rare in Africa, the species of conifer found in the Drakensberg |

Meanwhile, the ''lower slopes'' are mainly grassland, but are also home to ]s, which are rare in Africa, the species of conifer found in the Drakensberg belong to the genus ]. The grassland is of interest as it contains a great number of ] plants. Grasses found here include oat grass '']'', ''] filifolius'', ''] centrifugus'', caterpillar grass ''(])'', ''] dieterlenii'', and ]. | ||

| In the highest part of Drakensberg the composition of the flora is independent on ] (direction) and varies depending on the hardness of the rock ]. This hardness is related to ] and is variable even within a single ].<ref name=Knightetal2018/> | In the highest part of Drakensberg the composition of the flora is independent on ] (direction) and varies, depending on the hardness of the rock ]. This hardness is related to ] and is variable even within a single ].<ref name=Knightetal2018/> | ||

| === Fauna === | === Fauna === | ||

| The Drakensberg area is "home to 299 recorded bird species"' making up "37% of all non-marine avian species in southern Africa |

The Drakensberg area is "home to 299 recorded bird species"' making up "37% of all non-marine avian species in southern Africa".<ref name="Barrier of Spears" /> There are 24 species of snakes in the Drakensberg, two of which are highly venomous.<ref>{{Cite book|title=A field guide to the Natal Drakensberg|last=Irwin|first=Pat|publisher=The Natal Branch of the Wildlife Society of Southern Africa|year=1983|isbn=0-949966-452|pages=129}}</ref> | ||

| One bird is endemic to the high peaks, the ] ''(Anthus hoeschi)'', and another six species are found mainly here: ] ''(Lioptilus nigricapillus)'', ] ''(Oenanthe bifasciata)'', ] ''(Heteromirafra ruddi)'', ] ''(Chaetops aurantius)'', ] ''(Anthus chloris)'', and ] ''(Serinus symonsi)''. The endangered ] and ] are two of the birds of prey that hunt in the mountains. Mammals include ] ''(Oreotragus oreotragus)'', ] ''(Taurotragus oryx)'', and ] ''(Redunca fulvorufula)''. Other endemic species include three frogs found in the mountain streams, ] ''(Amietia dracomontana)'', Phofung river frog ''(])'', and ] ''(Amietia umbraculata)''. Fish are found in the many rivers and streams, including the ] (''Pseudobarbus quathlambae'') that was thought to be extinct before being found in the ] in Lesotho.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.lhwp.org.ls/environment/nehp/conservation/minnow/default.htm |title=Maloti Minnow |access-date=29 November 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130602183916/http://www.lhwp.org.ls/environment/nehp/conservation/minnow/default.htm |archive-date=2 June 2013 }}</ref><ref name="PreezCarruthers2015">{{cite book|last1=du Preez|first1=Louis |last2=Carruthers|first2=Vincent |title=A Complete Guide to the Frogs of Southern Africa|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5EegCgAAQBAJ|year=2015|publisher=Penguin Random House South Africa|isbn=978-1-77584-349-8}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Fauna of the high peaks ==== | |||

| There is one bird that is endemic to the high peaks, the ] ''(Anthus hoeschi)'', while another six are found mainly here: ] ''(Lioptilus nigricapillus)'', ] ''(Oenanthe bifasciata)'', ] ''(Heteromirafra ruddi)'', ] ''(Chaetops aurantius)'', ] ''(Anthus chloris)'', and ] ''(Serinus symonsi)''. The endangered ] and ] are two of the birds of prey that hunt in the mountains. Mammals include ] ''(Oreotragus oreotragus)'', ] ''(Taurotragus oryx)'' and ] ''(Redunca fulvorufula)''. Other endemic species include three frogs found in the mountain streams, ], ''(Amietia dracomontana)'', Phofung river frog ''(])'' and ] ''(Amietia umbraculata)''. Fish are found in the many rivers and streams including the ] (''Pseudobarbus quathlambae''), which was thought to be extinct but has been found in the ] in Lesotho.<ref>{{webarchive |title=Maloti Minnow |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130602183916/http://www.lhwp.org.ls/environment/nehp/conservation/minnow/default.htm }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="PreezCarruthers2015">{{cite book|last1=du Preez|first1=Louis |last2=Carruthers|first2=Vincent |title=A Complete Guide to the Frogs of Southern Africa|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5EegCgAAQBAJ|year=2015|publisher=Penguin Random House South Africa|isbn=978-1-77584-349-8}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Fauna of the lower slopes ==== | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| The lower slopes of the Drakensberg support much wildlife, perhaps most importantly the rare southern ] (which was nurtured here when facing extinction) and the ] (''Connochaetes gnou'', which {{as of | 2011| lc = on}} only thrives in protected areas and game reserves). The area is home to large herds of grazing and antelopes such as ] ''(Taurotragus oryx)'', ] ''(Redunca arundinum)'', ] ''(Redunca fulvorufula)'', ] ''(Pelea capreolus)'', and even some ] ''(Ourebia ourebi)''. ]s |

The lower slopes of the Drakensberg support much wildlife, perhaps most importantly the rare southern ] (which was nurtured here when facing extinction) and the ] (''Connochaetes gnou'', which {{as of | 2011| lc = on}} only thrives in protected areas and game reserves). The area is home to large herds of grazing fauna and antelopes such as ] ''(Taurotragus oryx)'', ] ''(Redunca arundinum)'', ] ''(Redunca fulvorufula)'', ] ''(Pelea capreolus)'', and even some ] ''(Ourebia ourebi)''. ]s also are present. Endemic species include a large number of ]s and other reptiles. There is one endemic frog, the forest rain frog ''(])'', and four more species that are found mainly in these mountains; long-toed tree frog ''(])'', plaintive rain frog ''(])'', rough rain frog ''(])'', and Poynton's caco ''(])''. | ||

| === Conservation === | === Conservation === | ||

| ], from ], near ] looking south. The hard erosion resistant layer that forms the upper edge of the escarpment here consists of flat lying quartzite belonging to the Black Reef Formation, which also forms the ] mountains near Pretoria.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name=norman />]] | ], from ], near ], looking south. The hard erosion resistant layer that forms the upper edge of the escarpment here consists of flat lying quartzite belonging to the Black Reef Formation, which also forms the ] mountains near Pretoria.<ref name=mccarthy /><ref name=norman>{{cite book|last1=Norman|first1=Nick|last2=Whitfield|first2=Gavin |title=Geological Journeys: A Traveller's Guide to South Africa's Rocks and Landforms|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_uDcm-olXE8C|year=2006|publisher=Penguin Random House South Africa|isbn=978-1-77007-062-2|pages=290–300}}</ref>]] | ||

| The |

The ''high slopes'' are hard to reach so the environment is fairly undamaged. However, tourism in the Drakensberg is developing, with a variety of ], hotels, and resorts appearing on the slopes. Much of the higher South African parts of the range have been designated as ]s or ]s. 7% of the Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands ecoregion is in protected areas. These include ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>"Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands". DOPA Explorer. Accessed 20 April 2022. </ref> | ||

| Of these the ] was listed by ] in 2000 as a ] site. The park also is in the ] (under the ]). The ], which contains some of the higher peaks, is part of this large park complex. Adjacent to the Ukhahlamba Drakensberg World Heritage Site is the 1900 ha Allendale Mountain Reserve, which is the largest private reserve adjoining the World Heritage Site and is found in the accessible Kamberg area, the heart of the historic ] of the Ukhahlamba. | |||

| The grassland of the ''lower slopes'' meanwhile has been greatly affected by agriculture, especially overgrazing. Original grassland and forest has nearly all disappeared and more protection is needed, though the Giant's Castle reserve is a haven for the ] and also is a breeding ground for the ]. | |||

| The grassland of the ''lower slopes'' has been greatly affected by agriculture, however, especially by ]. Nearly all of the original grassland and forest has disappeared and more protection is needed, although the ] is a haven for the ] and also is a breeding ground for the ]. 5.81% of the Drakensberg montane grasslands, woodlands and forests ecoregion is in protected areas. These include ], ], Golden Gate Highlands National Park, ], Sehlabathebe National Park, and Tsehlanyane National Park.<ref>"Drakensberg montane grasslands, woodlands and forests". DOPA Explorer. Accessed 20 April 2022. </ref> | |||

| ] region]] | |||

| The ] was established to preserve some of the high mountain areas of the range.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120130182044/http://www.maloti.org.ls/home/ |date=30 January 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| ] region]] | |||

| == Urban areas == | |||

| The ] was established to preserve some of the high mountain areas of the range.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://tfcaportal.org/node/26 |title=Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation Area |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200811104756/https://tfcaportal.org/node/26|archive-date=2020-08-11 |url-status=live |df=mdy-all}}</ref> | |||

| == Human habitation == | |||

| Towns and cities in the Drakensberg area include, from South to North, ] and ] in the Eastern Cape Province; ], ], ] – the former ] capital, ] and ] in KwaZulu-Natal; all of Lesotho, whose capital is ] and ] in ]. | |||

| Towns and cities in the Drakensberg area include, from south to north, ] and ] in the Eastern Cape Province; ], ], ] – the former ] capital, ], and ] in KwaZulu-Natal; all of Lesotho, whose capital is ]; and ] in ]. | |||

| == San cave paintings == | |||

| === San cave paintings === | |||

| ] cave in the UKhahlamba Drakensberg Park of ] close to the Lesotho border.]]There are numerous caves in the easily eroded sandstone of ], the layer below the thick, hard basalt layer on the KwaZulu Natal-Lesotho border. Many of these caves have ]s by the ] (Bushmen). This portion of the Drakensberg has between 35,000 and 40,000 works of ]<ref name="Barrier of Spears">{{cite web|url=http://www.southafrica.info/about/geography/drakensberg-050705.htm|title=Drakensberg: Barrier of Spears| last=Alexander|first=Mary|accessdate=2008-10-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303181740/http://www.southafrica.info/about/geography/drakensberg-050705.htm#.WuFxpYhua00|archive-date=2016-03-03}}</ref><ref name="Drakensberg Tourism">{{cite web|url=http://www.drakensberg-tourism.com/bushman-rock-art.html |title=Bushman and San Paintings in the Drakensberg |publisher=Drakensberg Tourism |accessdate=2008-10-03 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080918020735/http://www.drakensberg-tourism.com/bushman-rock-art.html |archivedate=18 September 2008 |df= }}</ref> and is the largest collection of such work in the world. Some 20,000 individual rock paintings have been recorded at 500 different caves and overhanging sites between the Drakensberg Royal Natal National Park and Bushman's Nek.<ref name="Drakensberg Tourism" /> Due to the materials used in their production, these paintings are difficult to date but there is anthropological evidence, including many hunting implements, that the San people existed in the Drakensberg at least 40,000 years ago, and possibly over 100,000 years ago. According to , "n Nd edema Gorge in the Central Ginsberg 3,900 paintings have been recorded at 17 sites. One of them, Sebaayeni Cave, contains 1,146 individual paintings."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.drakensbergmountains.co.za/bushman-rock-art.html|title=Drakensberg Rock Art|access-date=2008-10-03}}</ref> The website indicates that though "the oldest painting on a rock shelter wall in the Ginsberg dates back about 2400 years.....paint chips at least a thousand years older have also been found."<ref name="Barrier of Spears" /> The site also indicates that "he rock art of the Drakensberg is the largest and most concentrated group of rock paintings in Africa south of the Sahara, and is outstanding both in quality and diversity of subject."<ref name="Barrier of Spears" /> | |||

| ] cave in the UKhahlamba Drakensberg Park of ] close to the Lesotho border ]] | |||

| == In popular culture == | |||

| There are numerous caves in the easily eroded sandstone of ], the layer below the thick, hard basalt layer on the KwaZulu Natal-Lesotho border. Many of these caves have ]s by the ] (Bushmen). This portion of the Drakensberg has between 35,000 and 40,000 works of ],<ref name="Barrier of Spears">{{cite web|url=http://www.southafrica.info/about/geography/drakensberg-050705.htm|title=Drakensberg: Barrier of Spears| last=Alexander|first=Mary|access-date=3 October 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303181740/http://www.southafrica.info/about/geography/drakensberg-050705.htm#.WuFxpYhua00|archive-date=3 March 2016}}</ref><ref name="Drakensberg Tourism">{{cite web|url=http://www.drakensberg-tourism.com/bushman-rock-art.html |title=Bushman and San Paintings in the Drakensberg |publisher=Drakensberg Tourism |access-date=3 October 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080918020735/http://www.drakensberg-tourism.com/bushman-rock-art.html |archive-date=18 September 2008 }}</ref> and is the largest collection of such parietal work in the world. | |||

| Some 20,000 individual rock paintings have been recorded at 500 different caves and overhanging sites between the Drakensberg Royal Natal National Park and Bushman's Nek.<ref name="Drakensberg Tourism" /> Due to the materials used in their production, these paintings are difficult to date, but there is anthropological evidence, including many hunting implements, that the San people existed in the Drakensberg at least 40,000 years ago, and possibly more than 100,000 years ago. According to mountainsides.co.za, "n Nd edema Gorge in the Central Ginsberg 3,900 paintings have been recorded at 17 sites. One of them, Sebaayeni Cave, contains 1,146 individual paintings."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.drakensbergmountains.co.za/bushman-rock-art.html|title=Drakensberg Rock Art|access-date=3 October 2008}}</ref> The website, south Africa.info, indicates that although "the oldest painting on a rock shelter wall in the Ginsberg dates back about 2400 years... paint chips at least a thousand years older have also been found."<ref name="Barrier of Spears" /> The site also indicates that "he rock art of the Drakensberg is the largest and most concentrated group of rock paintings in Africa south of the Sahara, and is outstanding both in quality and diversity of subject."<ref name="Barrier of Spears" /> | |||

| The Drakensberg was featured in the 2009 ] ] ]. It was mentioned in the last scene of the movie, where after twenty-seven days of a great flood which people tried to survive by building arks, the waters began receding. The arks approach the ], where the Drakensberg (now the tallest mountain range on Earth) emerges. | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 153: | Line 125: | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| {{Reflist|2 |

{{Reflist|2|refs= | ||

| <!-- Not in use | |||

| <ref name= McCarthy2013> | |||

| {{cite journal|last1=McCarthy|first1=T. S.|title=The Okavango Delta and its Place in the Geomorphological Evolution of Southern Africa | |||

| | journal=South African Journal of Geology|volume=116|issue=1|year=2013|pages=1–54|issn=1012-0750|doi=10.2113/gssajg.116.1.1}}</ref> | |||

| Not in use--> | |||

| }} | |||

| == Further reading == | == Further reading == | ||

| {{refbegin}} | {{refbegin}} | ||

| * {{cite journal | last1=Rosen | first1=Deborah | last2=Lewis | first2=Colin | last3=Illgner | first3=Peter | title=Palaeoclimatic And Archaeological Implications of Organic- Rich Sediments at Tifftidell Ski Resort, Near Rhodes, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa | journal=Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa | volume=54 |issue=2 | pages=311–321 | year=1999 | doi = 10.1080/00359199909520630 }} | * {{cite journal | last1=Rosen | first1=Deborah | last2=Lewis | first2=Colin | last3=Illgner | first3=Peter | title=Palaeoclimatic And Archaeological Implications of Organic- Rich Sediments at Tifftidell Ski Resort, Near Rhodes, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa | journal=Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa | volume=54 |issue=2 | pages=311–321 | year=1999 | doi = 10.1080/00359199909520630 }} | ||

| {{refend}} | {{refend}} | ||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| {{Commons category|Drakensberg}} | {{Commons category|Drakensberg}} | ||

| {{Collier's |

{{Collier's poster|Drakenberge}} | ||

| {{Wikivoyage|Ukhahlamba Drakensberg}} | {{Wikivoyage|Ukhahlamba Drakensberg}} | ||

| * {{Wikivoyage |

* {{Wikivoyage inline|Mpumalanga Escarpment in a weekend|Mpumalanga Escarpment in a weekend}} | ||

| * – Official Website for the KwaZulu Natal Drakensberg |

* – Official Website for the KwaZulu Natal Drakensberg | ||

| * | |||

| * – Southern Drakensberg Tourism | |||

| * – PBS Nature episode covering the eland (largest member of antelope family) of the Drakensberg. | * – PBS Nature episode covering the eland (largest member of antelope family) of the Drakensberg. | ||

| * | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180828031853/http://www.govertical.co.za/ |date=28 August 2018 }} | ||

| * | * | ||

| {{Major African geological formations}} | {{Major African geological formations}} | ||

| {{World Heritage Sites in South Africa}} | {{World Heritage Sites in South Africa}} | ||

| {{Biodiversity of South Africa|ecoreg}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:13, 9 November 2024

Mountain range in South Africa

| uKhahlamba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Thabana Ntlenyana |

| Elevation | 3,482 m (11,424 ft) |

| Coordinates | 29°23′S 29°27′E / 29.383°S 29.450°E / -29.383; 29.450 |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 1,000 km (620 mi) SW to NE |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Dragon's Mountain (modern day) and Crazy Carriers Mountain from Voortrekkers (historical) |

| Native name | |

| Geography | |

| Countries | |

| Geology | |

| Rock types |

|

The Drakensberg (Zulu: uKhahlamba, Sotho: Maloti, Afrikaans: Drakensberge) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, which encloses the central Southern African plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – 2,000 to 3,482 metres (6,562 to 11,424 feet) within the border region of South Africa and Lesotho.

The Drakensberg escarpment stretches for more than 1,000 kilometres (600 miles) from the Eastern Cape Province in the South, then successively forms, in order from south to north, the border between Lesotho and the Eastern Cape and the border between Lesotho and KwaZulu-Natal Province. Thereafter it forms the border between KwaZulu-Natal and the Free State, and next as the border between KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga Province. The escarpment winds north from there, through Mpumalanga, where it includes features such as the Blyde River Canyon, Three Rondavels, and God's Window. It then extends farther north to Hoedspruit in southeastern Limpopo where it is known as 'Klein Drakensberg' by the Afrikaner. From Hoedspruit it extends west to Tzaneen, also in Limpopo Province, where it is known as the Wolkberg Mountains and Iron Crown Mountain. At 2,200 m (7,200 ft) above sea level, the Wolkberg is the highest elevation in Limpopo. The escarpment extends west again and at Mokopane it is known as the Strydpoort Mountains.

Etymology

The Afrikaans name Drakensberge comes from the name the earliest Dutch settlers gave to the escarpment, namely Drakensbergen, or Dragons' Mountains. The highest portion of the Great Escarpment is known in Zulu as uKhahlamba and as Maloti in Sotho ("Barrier of up-pointed spears").

Geology

Origins

Further information: Great Escarpment, Southern AfricaThe Great Escarpment is composed of steep rift valley walls formed around a bulging of continental crust during the breakup of southern Gondwana that have since eroded inland from their original positions near the southern African coast, and its entire eastern portion (see the accompanying map) constitutes the Drakensberg. The Drakensberg terminate in the north near Tzaneen at about the 22° S parallel. The absence of the Great Escarpment for approximately 450 km (280 mi) to the north of Tzaneen (to reappear on the border between Zimbabwe and Mozambique in the Chimanimani Mountains) is due to a failed westerly branch of the main rift that caused Antarctica to start drifting away from southern Africa during the breakup of Gondwana about 150 million years ago. The lower Limpopo River and Save River drain into the Indian Ocean through what remains of this relict incipient rift valley, which now forms part of the South African Lowveld.

During the past 20 million years, southern Africa has experienced massive uplifting, especially in the east, with the result that most of the plateau lies above 1,000 m (3,300 ft) despite extensive erosion. The plateau is tilted such that it is highest in the east and slopes gently downward toward the west and south. Typically, the elevation of the edge of the eastern escarpments is in excess of 2,000 m (6,600 ft). It reaches its highest point of over 3,000 m (9,800 ft) where the escarpment forms part of the international border between Lesotho and the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Appearance

The escarpment seen from below resembles a range of mountains. The Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and Lesotho Drakensberg have hard erosion-resistant upper surfaces and therefore have a very rugged appearance, combining steep-sided blocks and pinnacles (giving rise to the Zulu name "Barrier of up-pointed spears"). Who first gave these mountains their Afrikaans or Dutch name Drakensberg, and why, is unknown. The KwaZulu-Natal – Free State Drakensberg are composed of softer rocks and therefore have a more rounded, softer appearance from below. Generally, the top of the escarpment is almost table-top flat and smooth, even in Lesotho. The "Lesotho Mountains" are formed away from the Drakensberg escarpment by erosion gulleys which turn into deep valleys containing tributaries of the Orange River. The large number of such tributaries give the Lesotho Highlands a very rugged mountainous appearance, both from the ground and from the air.

The higher parts of Drakensberg have a mildly periglacial environment. It is possible that recent climate change has diminished the intensity of periglaciation.

Knight and Grab mapped out the distribution of lightning strikes in the Drakensburg and discovered that lightning significantly controls the evolution of the mountain landscapes because it helps to shape the summit areas – the highest areas – with this blasting effect. Previously, angular debris was presumed to have been created by changes typical of cold, periglacial environments, such as fracturing due to frost.

Composition

The geological composition of Drakensberg (escarpment wall) varies considerably along its more than 1000 km length. The Limpopo and Mpumalanga Drakensberg are capped by an erosion resistant quartzite layer that is part of the Transvaal Supergroup, which also forms the Magaliesberg to the north and northwest of Pretoria. These rocks are more than 2000 million years old. South of the 26°S parallel the Drakensberg escarpment is composed of Ecca shales, which belong to the Karoo Supergroup, and they are 300 million years old. The portion of the Drakensberg that forms the KwaZulu-Natal – Free State border is formed by slightly younger Beaufort rocks (250 million years old) that also are part of the Karoo Supergroup.

The Ecca and Beaufort groups are composed of sedimentary rocks that are less erosion resistant than the other rocks that make up the Drakensberg escarpment. Therefore, this portion of escarpment is not so impressive as the Mpumalanga and Lesotho stretches of the Drakensberg. The Drakensberg that form the northeastern and eastern borders of Lesotho, as well as the Eastern Cape Drakensberg, are composed of a thick layer of basalt (lava) that erupted 180 million years ago. That layer rests on the youngest of the Karoo Supergroup sediments, the Clarens sandstone, which was laid down under desert conditions, about 200 million years ago.

Geography

Peaks

The highest peak is Thabana Ntlenyana, at 3,482 m (11,424 ft). Other notable peaks include Mafadi (3,450 m (11,319 ft)), Makoaneng at 3,416 metres (11,207 ft), Njesuthi at 3,408 metres (11,181 ft), Champagne Castle at 3,377 metres (11,079 ft), Giant's Castle at 3,315 metres (10,876 ft), Ben Macdhui at 3,001 metres (9,846 ft), and Popple Peak at 3,331 metres (10,928 ft), all of these are in the area bordering on Lesotho, which contains an area popular for hikers, Cathedral Peak. North of Lesotho the range becomes lower and less rugged until entering Mpumalanga where the quartzite mountains of the Transvaal Drakensberg are loftier and more broken and they form the eastern rim of the Transvaal Basin, the Blyde River Canyon lying within this stretch. The geology of this section is the same as, and continuous with, that of the Magaliesberg.

Mountain passes

Main article: List of mountain passes of KwaZulu-NatalEcology

The high treeless peaks of the Drakensberg (from 2,500 m (8,200 ft) upward) have been described by the World Wide Fund for Nature as the Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands ecoregion. These steep slopes are the most southerly high mountains in Africa, and being farther from the equator provide cooler habitats at lower elevations than most mountain ranges on the continent. High rainfall generates many mountain streams and rivers, including the sources of the Orange River, southern Africa's longest, and the Tugela River.

These mountains also have the world's highest waterfall, the Tugela Falls (Thukela Falls), which has a total drop of 947 m (3,107 ft) (Venezuela's Angel Falls is also a candidate for highest waterfall). The rivers that run from the Drakensberg are an essential resource for South Africa's economy, providing water for the industrial provinces of Mpumalanga and Gauteng, which contains the city of Johannesburg. The climate is wet and cool at the high elevations, which experience snowfall in winter.

The grassy lower slopes (from 1,800 to 2,500 m (5,900 to 8,200 ft)) of the Drakensberg in Eswatini, South Africa and Lesotho constitute the Drakensberg montane grasslands, woodlands, and forests ecoregion.

Flora

The mountains are rich in plant life, including a large number of species listed in the Red Data Book of threatened plants, with 119 species listed as globally endangered and "of the 2 153 plant species in the park, a remarkable 98 are endemic or near-endemic".

The flora of the high alti-montane grasslands is mainly tussock grass, creeping plants, and small shrubs such as ericas. These include the rare Spiral Aloe (Aloe polyphylla), which as its name suggests, has leaves with a spiral shape.

Meanwhile, the lower slopes are mainly grassland, but are also home to conifers, which are rare in Africa, the species of conifer found in the Drakensberg belong to the genus Podocarpus. The grassland is of interest as it contains a great number of endemic plants. Grasses found here include oat grass Monocymbium ceresiiforme, Diheteropogon filifolius, Sporobolus centrifugus, caterpillar grass (Harpochloa falx), Cymbopogon dieterlenii, and Eulalia villosa.

In the highest part of Drakensberg the composition of the flora is independent on slope aspect (direction) and varies, depending on the hardness of the rock clasts. This hardness is related to weathering and is variable even within a single landform.

Fauna

The Drakensberg area is "home to 299 recorded bird species"' making up "37% of all non-marine avian species in southern Africa". There are 24 species of snakes in the Drakensberg, two of which are highly venomous.

One bird is endemic to the high peaks, the mountain pipit (Anthus hoeschi), and another six species are found mainly here: Bush blackcap (Lioptilus nigricapillus), buff-streaked chat (Oenanthe bifasciata), Rudd's lark (Heteromirafra ruddi), Drakensberg rockjumper (Chaetops aurantius), yellow-breasted pipit (Anthus chloris), and Drakensberg siskin (Serinus symonsi). The endangered Cape vulture and lesser kestrel are two of the birds of prey that hunt in the mountains. Mammals include klipspringer (Oreotragus oreotragus), eland (Taurotragus oryx), and mountain reedbuck (Redunca fulvorufula). Other endemic species include three frogs found in the mountain streams, Drakensberg river frog (Amietia dracomontana), Phofung river frog (Amietia vertebralis), and Maluti river frog (Amietia umbraculata). Fish are found in the many rivers and streams, including the Maluti redfin (Pseudobarbus quathlambae) that was thought to be extinct before being found in the Senqunyane River in Lesotho.

The lower slopes of the Drakensberg support much wildlife, perhaps most importantly the rare southern white rhinoceros (which was nurtured here when facing extinction) and the black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou, which as of 2011 only thrives in protected areas and game reserves). The area is home to large herds of grazing fauna and antelopes such as eland (Taurotragus oryx), reedbuck (Redunca arundinum), mountain reedbuck (Redunca fulvorufula), grey rhebok (Pelea capreolus), and even some oribi (Ourebia ourebi). Chacma baboons also are present. Endemic species include a large number of chameleons and other reptiles. There is one endemic frog, the forest rain frog (Breviceps sylvestris), and four more species that are found mainly in these mountains; long-toed tree frog (Leptopelis xenodactylus), plaintive rain frog (Breviceps maculatus), rough rain frog (Breviceps verrucosus), and Poynton's caco (Cacosternum poyntoni).

Conservation

The high slopes are hard to reach so the environment is fairly undamaged. However, tourism in the Drakensberg is developing, with a variety of hiking trails, hotels, and resorts appearing on the slopes. Much of the higher South African parts of the range have been designated as game reserves or wilderness areas. 7% of the Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands ecoregion is in protected areas. These include Golden Gate Highlands National Park, Sehlabathebe National Park, Tsehlanyane National Park, Malekgalonyane Nature Reserve, Giant's Castle Game Reserve, Loteni Nature Reserve, Natal National Park, Vergelegen Nature Reserve, Beaumont Nature Reserve, and Lammergeier Highlands Nature Reserve.

Of these the uKhahlamba Drakensberg Park was listed by UNESCO in 2000 as a World Heritage site. The park also is in the List of Wetlands of International Importance (under the Ramsar Convention). The Royal Natal National Park, which contains some of the higher peaks, is part of this large park complex. Adjacent to the Ukhahlamba Drakensberg World Heritage Site is the 1900 ha Allendale Mountain Reserve, which is the largest private reserve adjoining the World Heritage Site and is found in the accessible Kamberg area, the heart of the historic San (Bushman) painting region of the Ukhahlamba.

The grassland of the lower slopes has been greatly affected by agriculture, however, especially by overgrazing. Nearly all of the original grassland and forest has disappeared and more protection is needed, although the Giant's Castle reserve is a haven for the eland and also is a breeding ground for the bearded vulture. 5.81% of the Drakensberg montane grasslands, woodlands and forests ecoregion is in protected areas. These include Kruger National Park, Mountain Zebra National Park, Golden Gate Highlands National Park, Camdeboo National Park, Sehlabathebe National Park, and Tsehlanyane National Park.

The Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation Area was established to preserve some of the high mountain areas of the range.

Human habitation

Towns and cities in the Drakensberg area include, from south to north, Matatiele and Barkly East in the Eastern Cape Province; Ladysmith, Newcastle, Ulundi – the former Zulu capital, Dundee, and Ixopo in KwaZulu-Natal; all of Lesotho, whose capital is Maseru; and Tzaneen in Limpopo Province.

San cave paintings

There are numerous caves in the easily eroded sandstone of Clarens Formation, the layer below the thick, hard basalt layer on the KwaZulu Natal-Lesotho border. Many of these caves have paintings by the San (Bushmen). This portion of the Drakensberg has between 35,000 and 40,000 works of San rock art, and is the largest collection of such parietal work in the world.

Some 20,000 individual rock paintings have been recorded at 500 different caves and overhanging sites between the Drakensberg Royal Natal National Park and Bushman's Nek. Due to the materials used in their production, these paintings are difficult to date, but there is anthropological evidence, including many hunting implements, that the San people existed in the Drakensberg at least 40,000 years ago, and possibly more than 100,000 years ago. According to mountainsides.co.za, "n Nd edema Gorge in the Central Ginsberg 3,900 paintings have been recorded at 17 sites. One of them, Sebaayeni Cave, contains 1,146 individual paintings." The website, south Africa.info, indicates that although "the oldest painting on a rock shelter wall in the Ginsberg dates back about 2400 years... paint chips at least a thousand years older have also been found." The site also indicates that "he rock art of the Drakensberg is the largest and most concentrated group of rock paintings in Africa south of the Sahara, and is outstanding both in quality and diversity of subject."

See also

References

- ^ Reader's Digest Atlas of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Reader's Digest Association South Africa. 1984. pp. 13, 190–192.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (1975); Micropaedia Vol. III, p. 655. Helen Hemingway Benton Publishers, Chicago.

- ^ Pearse, Reg O. (1973). Barrier of Spears: Drama of the Drakensberg. H. Timmins. p. i. ISBN 978-0-86978-050-3.

- The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World. London: Times Books. 1999. p. 90. ISBN 9780007419135.

- ^ McCarthy, Terence; Rubidge, Bruce (2005). The Story of Earth & Life: A Southern Africa Perspective on a 4.6 Billion-year Journey. Cape Town: Penguin Random House South Africa. pp. 16–7, 192–195, 245–248, 263, 267–269. ISBN 978-1-77007-148-3.

- ^ Knight, Jasper; Grab, Stefan W.; Carbutt, Clinton (2018). "Influence of mountain geomorphology on alpine ecosystems in the Drakensberg Alpine Centre, Southern Africa". Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography. 100 (2): 140–162. doi:10.1080/04353676.2017.1418628. S2CID 134848291.

- Foss, Kanina (15 October 2013). "New evidence on lightning strikes: Mountains a lot less stable than we think". phys.org. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Geological map of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland (1970). Council for Geoscience, Geological Survey of South Africa.

- "Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ Alexander, Mary. "Drakensberg: Barrier of Spears". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- Irwin, Pat (1983). A field guide to the Natal Drakensberg. The Natal Branch of the Wildlife Society of Southern Africa. p. 129. ISBN 0-949966-452.

- "Maloti Minnow". Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- du Preez, Louis; Carruthers, Vincent (2015). A Complete Guide to the Frogs of Southern Africa. Penguin Random House South Africa. ISBN 978-1-77584-349-8.

- Norman, Nick; Whitfield, Gavin (2006). Geological Journeys: A Traveller's Guide to South Africa's Rocks and Landforms. Penguin Random House South Africa. pp. 290–300. ISBN 978-1-77007-062-2.

- "Drakensberg alti-montane grasslands and woodlands". DOPA Explorer. Accessed 20 April 2022.

- "Drakensberg montane grasslands, woodlands and forests". DOPA Explorer. Accessed 20 April 2022.

- "Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation Area". Archived from the original on August 11, 2020.

- ^ "Bushman and San Paintings in the Drakensberg". Drakensberg Tourism. Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- "Drakensberg Rock Art". Retrieved 3 October 2008.

Further reading

- Rosen, Deborah; Lewis, Colin; Illgner, Peter (1999). "Palaeoclimatic And Archaeological Implications of Organic- Rich Sediments at Tifftidell Ski Resort, Near Rhodes, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa. 54 (2): 311–321. doi:10.1080/00359199909520630.

External links

Mpumalanga Escarpment in a weekend travel guide from Wikivoyage

Mpumalanga Escarpment in a weekend travel guide from Wikivoyage- KZN Drakensberg Homepage – Official Website for the KwaZulu Natal Drakensberg

- Southern Drakensberg Tourism – Southern Drakensberg Tourism

- Nature – Drakensberg: Barrier of Spears – PBS Nature episode covering the eland (largest member of antelope family) of the Drakensberg.

- Drakensberg hiking trails Archived 28 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Maloti-Drakensberg

| World Heritage Sites in South Africa | ||

|---|---|---|

| For official site names, see each article or the List of World Heritage Sites in South Africa. | ||

| ||

- Drakensberg

- Afromontane ecoregions

- Climbing areas of South Africa

- Ecoregions of Africa

- Escarpments of Africa

- Extinct volcanism

- Great Escarpment, Southern Africa

- Landforms of KwaZulu-Natal

- Landforms of Mpumalanga

- Landforms of the Free State (province)

- Large igneous provinces

- Lesotho–South Africa border

- Montane grasslands and shrublands

- Mountain ranges of Lesotho

- Mountain ranges of Limpopo

- Mountain ranges of South Africa

- Mountain ranges of the Eastern Cape

- Precambrian volcanism

- Prehistoric Africa

- Triassic volcanism

- Volcanism of Lesotho

- Volcanism of South Africa

- World Heritage Sites in South Africa