| Revision as of 17:32, 5 April 2020 editSkoulikomirmigotripa (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,252 edits Added more coomon name for the modern Greek language as is done is Modern Hebre (see Talk page)Tag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:58, 14 November 2024 edit undo2a00:23c4:ff0b:901:7894:a570:ba3e:d4c4 (talk) →Greco-Australian | ||

| (108 intermediate revisions by 74 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{Refimprove|date=March 2019}} | {{Refimprove|date=March 2019}} | ||

| {{Infobox language | {{Infobox language | ||

| | name = Modern Greek | | name = Modern Greek | ||

| | nativename = {{lang|el|Νέα Ελληνικά}} | | nativename = {{lang|el|Νέα Ελληνικά}} | ||

| | pronunciation = {{IPA-el|ˈne.a eliniˈka|}} | | pronunciation = {{IPA-el|ˈne.a eliniˈka|}} | ||

| | states = ]<br>]<br>] (])<br>] (], ]) | | states = ]<br>]<br>] (])<br>] (])<br>] (], ]) | ||

| | speakers = |

| speakers = 13.4 million | ||

| | date = |

| date = 2012 | ||

| | ref = <ref>{{Cite journal|date=2015|title=Greek|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/ell|journal=Ethnologue: Languages of the World|edition=18}}</ref> | |||

| | ref = <ref name="NE">] "Världens 100 största språk 2007" The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007</ref> | |||

| | familycolor = Indo-European | | familycolor = Indo-European | ||

| | fam2 = ] | | fam2 = ] | ||

| | fam3 = ] | | fam3 = ] | ||

| | fam4 = ]–] | | fam4 = ]–]{{Citation needed|date=May 2022}} | ||

| | ancestor = ] | | ancestor = ] | ||

| | ancestor2 = ] | | ancestor2 = ] | ||

| | ancestor3 = ] | | ancestor3 = ] | ||

| | ancestor4 = ] | | ancestor4 = ] | ||

| | dia1 = Italiot |

| dia1 = ] (] and ]) | ||

| | dia2 = ] (including ]) | | dia2 = ] (including ]) | ||

| | dia3 = ] | | dia3 = ] | ||

| | dia4 = ] | | dia4 = ] | ||

| | dia5 = ] | | dia5 = ] | ||

| | dia6 = ] | | dia6 = ] | ||

| | dia7 = ] | | dia7 = ] | ||

| | dia8 = ] | | dia8 = ] | ||

| | dia9 = ] | | dia9 = ] | ||

| | dia10 = '']'' (base for the St. Mod. Greek) | | dia10 = '']'' (base for the St. Mod. Greek) | ||

| | dia11 = '']'' (artificial, base for the St. Mod. Greek) | | dia11 = '']'' (artificial, base for the St. Mod. Greek) | ||

| | dia12 = '']'' | | dia12 = '']'' | ||

| | stand1 = ] | | stand1 = ] | ||

| | script = ]<br>] | | script = ]<br>] | ||

| | iso1 = el | | iso1 = el | ||

| | iso2b = gre | | iso2b = gre | ||

| | iso2t = ell | | iso2t = ell | ||

| | iso3 = ell | | iso3 = ell | ||

| | lingua = part of ] | | lingua = part of ] | ||

| | glotto = mode1248 | | glotto = mode1248 | ||

| | glottorefname = Modern Greek | | glottorefname = Modern Greek | ||

| | notice = IPA | | notice = IPA | ||

| | nation = {{ublist|class=nowrap |{{GRE}} |{{CYP}} |''{{EU}}'' }} | | nation = {{ublist|class=nowrap |{{GRE}} |{{CYP}} |''{{EU}}'' }} | ||

| | minority = {{startplainlist|class=nowrap}} | | minority = {{startplainlist|class=nowrap}} | ||

| <!---Do not remove entries with a source or add entries without a source! :---> | <!---Do not remove entries with a source or add entries without a source! :---> | ||

| * {{ALB}}<ref>{{ |

* {{ALB}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Jeffries |first=Ian |title=Eastern Europe at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century: A Guide to the Economies in Transition |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=L7PBtDujYt0C&pg=PA69 |year=2002 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-23671-3 |page=69 |quote= "It is difficult to know how many ethnic Greeks there are in Albania. The Greek government, it is typically claimed, says there are around 300,000 ethnic Greeks in Albania, but most Western estimates are around the 200,000 mark ..."}}</ref> | ||

| * {{ARM}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/148/declarations?p_auth=HOz1LGU0|title=Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 - European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages|website= Official Website of the Council of Europe|publisher= Council of Europe| |

* {{ARM}}<ref name =ECRML>{{cite web|url=https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/148/declarations?p_auth=HOz1LGU0|title=Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 - European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages|website= Official Website of the Council of Europe|publisher= Council of Europe|access-date=5 April 2020}}</ref> | ||

| * {{HUN}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://languagecharter.eokik.hu/sites/languages/L-Greek_in_Hungary.htm |title=Greek in Hungary|website=Database for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages |publisher=Public Foundation for European Comparative Minority Research| |

* {{HUN}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://languagecharter.eokik.hu/sites/languages/L-Greek_in_Hungary.htm |title=Greek in Hungary|website=Database for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages |publisher=Public Foundation for European Comparative Minority Research|access-date=31 May 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130429113237/http://languagecharter.eokik.hu/sites/languages/L-Greek_in_Hungary.htm|archive-date=29 April 2013}}</ref> | ||

| * {{ITA}}<ref>{{cite web|work=Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs|title=Italy: Cultural Relations and Greek Community|date=9 July 2013|url=http://www.mfa.gr/en/greece-bilateral-relations/italy/cultural-relations-and-greek-community.html|quote="The Greek Italian community numbers some 30,000 and is concentrated mainly in central Italy. The age-old presence in Italy of Italians of Greek descent – dating back to Byzantine and Classical times – is attested to by the Griko dialect, which is still spoken in the Magna Graecia region. This historically Greek-speaking villages are Condofuri, Galliciano, Roccaforte del Greco, Roghudi, Bova and Bova Marina, which are in the Calabria region (the capital of which is Reggio). The Grecanic region, including Reggio, has a population of some 200,000, while speakers of the Griko dialect number fewer that 1,000 persons."}}</ref> | * {{ITA}}<ref>{{cite web|work=Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs|title=Italy: Cultural Relations and Greek Community|date=9 July 2013|url=http://www.mfa.gr/en/greece-bilateral-relations/italy/cultural-relations-and-greek-community.html|quote="The Greek Italian community numbers some 30,000 and is concentrated mainly in central Italy. The age-old presence in Italy of Italians of Greek descent – dating back to Byzantine and Classical times – is attested to by the Griko dialect, which is still spoken in the Magna Graecia region. This historically Greek-speaking villages are Condofuri, Galliciano, Roccaforte del Greco, Roghudi, Bova and Bova Marina, which are in the Calabria region (the capital of which is Reggio). The Grecanic region, including Reggio, has a population of some 200,000, while speakers of the Griko dialect number fewer that 1,000 persons."}}</ref> | ||

| * {{ROU}}<ref name =ECRML /> | |||

| * {{ROU}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/148/declarations?p_auth=HOz1LGU0|title=Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 - European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages|website= Official Website of the Council of Europe|publisher= Council of Europe|accessdate=5 April 2020|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * {{ZAF}}{{efn|(protected language)}}<ref>{{cite web|title=Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 - Chapter 1: Founding Provisions|url=http://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/chapter-1-founding-provisions|website=www.gov.za|access-date=6 December 2014}}</ref> | |||

| * {{TUR}}<ref>{{harvnb|Tsitselikis|2013|pp=294–295}}.</ref> | |||

| * {{TUR}}<ref>{{cite book|last=Tsitselikis|first=Konstantinos|chapter=A Surviving Treaty: The Lausanne Minority Protection in Greece and Turkey|title=The Interrelation between the Right to Identity of Minorities and their Socio-economic Participation|editor1-last=Henrard|editor1-first=Kristin|location=Leiden and Boston|publisher=Martinus Nijhoff Publishers|year=2013|isbn=9789004244740|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gUYzAQAAQBAJ |pages=294–295}}.</ref> | |||

| * {{UKR}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/148/declarations?p_auth=HOz1LGU0|title=Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 - European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages|website= Official Website of the Council of Europe|publisher= Council of Europe|accessdate=5 April 2020|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * {{UKR}}<ref name =ECRML /> | |||

| {{endplainlist}} | {{endplainlist}} | ||

| | agency = ] | |||

| | ethnicity = ] | |||

| | region = ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Modern Greek''' ({{ |

'''Modern Greek''' ({{langx|el|label=]|Νέα Ελληνικά}}, {{translit|el|Néa Elliniká}} {{IPA-el|ˈne.a eliniˈka|}} or {{lang|el|Κοινή Νεοελληνική Γλώσσα}}, {{translit|el|Kiní Neoellinikí Glóssa}}), generally referred to by speakers simply as '''Greek''' ({{lang|el|Ελληνικά}}, {{translit|el|Elliniká}}), refers collectively to the ]s of the ] spoken in the modern era, including the official standardized form of the language sometimes referred to as ]. The end of the ] period and the beginning of Modern Greek is often symbolically assigned to the fall of the ] in 1453, even though that date marks no clear linguistic boundary and many characteristic features of the modern language arose centuries earlier, having begun around the fourth century AD. | ||

| During most of the period, the language existed in a situation of ], with regional spoken dialects existing side by side with learned, more archaic written forms, as with the vernacular and learned varieties ('']'' and '']'') that co-existed throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries. | During most of the Modern Greek period, the language existed in a situation of ], with regional spoken dialects existing side by side with learned, more archaic written forms, as with the vernacular and learned varieties ('']'' and '']'') that co-existed in Greece throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries. | ||

| ==Varieties== | ==Varieties== | ||

| {{Main|Varieties of Modern Greek}} | {{Main|Varieties of Modern Greek}} | ||

| Varieties of Modern Greek include |

Varieties of Modern Greek include Demotic, Katharevousa, Pontic, Cappadocian, Mariupolitan, Southern Italian, Yevanic, Tsakonian and Greco-Australian. | ||

| === Demotic === | === Demotic === | ||

| {{Main|Demotic Greek}} | {{Main|Demotic Greek}} | ||

| Strictly speaking, ''Demotic'' (Δημοτική) refers to all ''popular'' varieties of Modern Greek that followed a common evolutionary path from ] and have retained a high degree of ] to the present. As shown in Ptochoprodromic and ] poems, Demotic Greek was the vernacular already before the 11th century and called the "Roman" language of the ], notably in peninsular ], the ], coastal ], Constantinople, and ]. | Strictly speaking, ''Demotic'' or ''Dimotiki'' ({{lang|el|Δημοτική}}), refers to all ''popular'' varieties of Modern Greek that followed a common evolutionary path from ] and have retained a high degree of ] to the present. As shown in ] and ] poems, Demotic Greek was the vernacular already before the 11th century and called the "Roman" language of the ], notably in peninsular ], the ], coastal ], ], and ]. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Today, a |

Today, a standardized variety of Demotic Greek is the official language of Greece and Cyprus, and is referred to as "Standard Modern Greek", or less strictly simply as "Greek", "Modern Greek", or "Demotic". | ||

| Demotic Greek comprises various regional varieties with minor linguistic differences, mainly in phonology and vocabulary. Due to the high degree of mutual intelligibility of these varieties, Greek linguists refer to them as "idioms" of a wider "Demotic dialect", known as "Koine Modern Greek" ( |

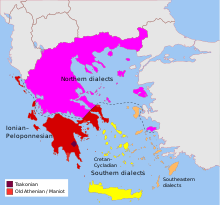

Demotic Greek comprises various regional varieties with minor linguistic differences, mainly in phonology and vocabulary. Due to the high degree of mutual intelligibility of these varieties, Greek linguists refer to them as "idioms" of a wider "Demotic dialect", known as "Koine Modern Greek" ({{Lang|el-Latn|Koiní Neoellinikí}} - 'common Neo-Hellenic'). Most English-speaking linguists however refer to them as "dialects", emphasizing degrees of variation only when necessary. Demotic Greek varieties are divided into two main groups, Northern and Southern. | ||

| The main distinguishing feature common to Northern variants is a set of standard phonological shifts in ''unaccented'' vowel phonemes: {{IPA|}} becomes {{IPA|}}, {{IPA|}} becomes {{IPA|}}, and {{IPA|}} and {{IPA|}} are dropped. The dropped vowels' existence is implicit, and may affect surrounding phonemes: for example, a dropped {{IPA|}} palatalizes preceding consonants, just like an {{IPA|}} that is pronounced. Southern variants do not exhibit these phonological shifts. | The main distinguishing feature common to Northern variants is a set of standard phonological shifts in ''unaccented'' vowel phonemes: {{IPA|}} becomes {{IPA|}}, {{IPA|}} becomes {{IPA|}}, and {{IPA|}} and {{IPA|}} are dropped. The dropped vowels' existence is implicit, and may affect surrounding phonemes: for example, a dropped {{IPA|}} palatalizes preceding consonants, just like an {{IPA|}} that is pronounced. Southern variants do not exhibit these phonological shifts. | ||

| Examples of Northern dialects are ]n (]), ], ],<ref name=GreekSyntax>{{cite book |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XpUBTDDGr_QC& |

Examples of Northern dialects are ]n (]), ], ],<ref name=GreekSyntax>{{cite book |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XpUBTDDGr_QC&q=%22macedonian+dialect%22&pg=PA99 |title=Studies in Greek Syntax |editor-first1=Artemis |editor-last1=Alexiadou |editor-first2=Geoffrey C. |editor-last2=Horrocks |editor-first3=Melita |editor-last3 = Stavrou|chapter = On Clitics, Prepositions and Case Licensing in Standard and Macedonian Greek|author-last = Dimitriadis|author-first = Alexis |year=1999 |publisher=Springer |isbn=9780792352907 }}</ref> ], ], Northern ]n, ], ], ], and ]. | ||

| The Southern category is divided into groups that include: | The Southern category is divided into groups that include: | ||

| :#Old Athenian-Maniot: ], ], ], ] (Old Athenian) and ] (Maniot) | :#Old Athenian-Maniot: ], ], ], ] (Old Athenian) and ] (Maniot) | ||

| :#Ionian-Peloponnesian: ] (except Mani), ], ], Boeotia, and Southern ] | :#Ionian-Peloponnesian: ] (except Mani), ], ], Boeotia, and Southern ] | ||

| :#Cretan-Cycladian: ], ], and several enclaves in Syria and Lebanon{{cn|date=March 2019}} | :#Cretan-Cycladian: ], ], and several enclaves in Syria and Lebanon{{cn|date=March 2019}} | ||

| :#Southeastern: ], ], ], and ]. | :#Southeastern: ], ], ], and ]. | ||

| Demotic Greek has officially been taught in ] Greek script since 1982. |

Demotic Greek has officially been taught in ] Greek script since 1982. | ||

| === Katharevousa === | === Katharevousa === | ||

| {{Main|Katharevousa}} | {{Main|Katharevousa}} | ||

| ''Katharevousa'' (Καθαρεύουσα) is a |

''Katharevousa'' ({{Lang|el|Καθαρεύουσα}}) is a ] promoted in the 19th century at the foundation of the modern Greek state, as a compromise between ] and modern Demotic. It was the official language of modern Greece until 1976. | ||

| Katharevousa is written in ] Greek script. Also, while Demotic Greek contains loanwords from Turkish, Italian, Latin, and other languages, these have for the most part been purged from Katharevousa. See also the ]. | Katharevousa is written in ] Greek script. Also, while Demotic Greek contains loanwords from Turkish, Italian, Latin, and other languages, these have for the most part been purged from Katharevousa. See also the ]. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 97: | ||

| {{Main|Pontic Greek}} | {{Main|Pontic Greek}} | ||

| ] in yellow. ] in orange. ] in green, with green dots indicating individual Cappadocian Greek villages in 1910.<ref |

] in yellow. ] in orange. ] in green, with green dots indicating individual Cappadocian Greek villages in 1910.<ref name="Dawkins, R.M 1916" />]] | ||

| ''Pontic'' (Ποντιακά) was originally spoken along the mountainous Black Sea coast of Turkey, the so-called ] region, until most of its speakers were killed or displaced to modern Greece during the ] (1919–1921), followed later by the ] in 1923. (Small numbers of ] escaped these events and still reside in the Pontic villages of Turkey.) It |

''Pontic'' ({{Lang|el|Ποντιακά}}) was originally spoken along the mountainous Black Sea coast of Turkey, the so-called ] region, until most of its speakers were killed or displaced to modern Greece during the ] (1919–1921), followed later by the ] in 1923. (Small numbers of ] escaped these events and still reside in the Pontic villages of Turkey.) It derives from ] and ] and preserves characteristics of ] due to ancient colonizations of the region. Pontic evolved as a separate dialect from Demotic Greek as a result of the region's isolation from the Greek mainstream after the ] fragmented the Byzantine Empire into separate kingdoms (see ]). | ||

| === Cappadocian === | === Cappadocian === | ||

| {{Main|Cappadocian Greek}} | {{Main|Cappadocian Greek}} | ||

| ''Cappadocian'' (Καππαδοκικά) is a Greek dialect of central Turkey of the same fate as Pontic; its speakers settled in mainland Greece after the ] (1919–1921) and the later ] in 1923. Cappadocian Greek diverged from the other Byzantine Greek dialects earlier, beginning with the Turkish conquests of central Asia Minor in the 11th and 12th centuries, and so developed several radical features, such as the loss of the gender for nouns.<ref name="Dawkins, R.M 1916">Dawkins |

''Cappadocian'' ({{Lang|el|Καππαδοκικά}}) is a Greek dialect of central Turkey of the same fate as Pontic; its speakers settled in mainland Greece after the ] (1919–1921) and the later ] in 1923. Cappadocian Greek diverged from the other Byzantine Greek dialects earlier, beginning with the Turkish conquests of central Asia Minor in the 11th and 12th centuries, and so developed several radical features, such as the loss of the gender for nouns.<ref name="Dawkins, R.M 1916">{{cite book |last1=Dawkins |first1=R.M. |title=Modern Greek in Asia Minor. A study of dialect of Silli, Cappadocia and Pharasa. |date=1916 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |url=https://archive.org/details/moderngreekinas00hallgoog}}</ref> Having been isolated from the crusader conquests (]) and the later Venetian influence of the Greek coast, it retained the Ancient Greek terms for many words that were replaced with ] ones in Demotic Greek.<ref name="Dawkins, R.M 1916" /> The poet ], whose name means "Roman", referring to his residence amongst the "Roman" Greek speakers of Cappadocia, wrote a few poems in Cappadocian Greek, one of the earliest attestations of the dialect.<ref>Δέδες, Δ. 1993. Ποιήματα του Μαυλανά Ρουμή. Τα Ιστορικά 10.18–19: 3–22. (in Greek)</ref><ref>Meyer, G. 1895. Die griechischen Verse in Rabâbnâma. Byzantinische Zeitschrift 4: 401–411. (in German)</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.opoudjis.net/Play/rumiwalad.html |title=Greek Verses of Rumi & Sultan Walad |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171008025951/http://www.opoudjis.net/Play/rumiwalad.html |archive-date=8 October 2017 }}</ref><ref></ref> | ||

| === Mariupolitan === | === Mariupolitan === | ||

| {{Main| |

{{Main|Mariupol Greek}} | ||

| '' |

''Ruméika'' ({{Lang|el|Ρωμαίικα}}) or Mariupolitan Greek is a dialect spoken in about 17 villages around the northern coast of the ] in southern ] and ]. Mariupolitan Greek is closely related to Pontic Greek and evolved from the dialect of Greek spoken in ], which was a part of the Byzantine Empire and then the Pontic ], until that latter state fell to the Ottomans in 1461.<ref>Dawkins, Richard M. "The Pontic dialect of Modern Greek in Asia Minor and Russia". Transactions of the Philological Society 36.1 (1937): 15–52.</ref> Thereafter, the Crimean Greek state continued to exist as the independent Greek ]. The Greek-speaking inhabitants of Crimea were ] by ] to resettle in the new city of ] after the ] to escape the then Muslim-dominated Crimea.<ref>{{cite news|title=Greeks of the Steppe |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/greeks-of-the-steppe/2012/11/10/b7ff79de-24ec-11e2-9313-3c7f59038d93_story.html |access-date=25 October 2014|newspaper=The Washington Post|date=10 November 2012}}</ref> Mariupolitan's main features have certain similarities with both Pontic (e.g. the lack of ] of ''-ía, éa'') and the northern varieties of the core dialects (e.g. the northern vocalism).<ref>Kontosopoulos (2008), 109</ref> | ||

| === Southern Italian === | === Southern Italian === | ||

| ] and ] dialects are spoken]] | ] and ] dialects are spoken]] | ||

| ''Southern Italian'' or ''Italiot'' (Κατωιταλιώτικα) comprises both ] and ] varieties, spoken by around 15 villages in the regions of ] and ]. The Southern Italian dialect is the last living trace of Hellenic elements in Southern Italy that once formed ]. Its origins can be traced to the ] settlers who colonised the area from ] and ] in 700 |

''Southern Italian'' or ''Italiot'' ({{Lang|el|Κατωιταλιώτικα}}) comprises both ] and ] varieties, spoken by around 15 villages in the regions of ] and ]. The Southern Italian dialect is the last living trace of Hellenic elements in Southern Italy that once formed ]. Its origins can be traced to the ] settlers who colonised the area from ] and ] in 700 BC. | ||

| It has received significant Koine Greek influence through ] colonisers who re-introduced Greek language to the region, starting with ]'s conquest of ] in late antiquity and continuing through the Middle Ages. Griko and Demotic are mutually intelligible to some extent, but the former shares some common characteristics with Tsakonian. | It has received significant Koine Greek influence through ] colonisers who re-introduced Greek language to the region, starting with ]'s conquest of ] in late antiquity and continuing through the Middle Ages. Griko and Demotic are mutually intelligible to some extent, but the former shares some common characteristics with Tsakonian. | ||

| Line 118: | Line 121: | ||

| {{Main|Yevanic language}} | {{Main|Yevanic language}} | ||

| ''Yevanic'' is |

''Yevanic'' ({{Lang|yej|יעואניקה}}, {{Lang|el|Γεβανικά}}) is an almost extinct language of ]. The language was already in decline for centuries until most of its speakers were killed in ]. Afterward, the language was mostly kept by remaining Romaniote emigrants to ], where it was displaced by ]. | ||

| === Tsakonian === | === Tsakonian === | ||

| {{Main|Tsakonian language}} | {{Main|Tsakonian language}} | ||

| ''Tsakonian'' ({{lang|grc|Τσακωνικά}}) is spoken in its full form today only in a small number of villages around the town of ] in the region of ] in the Southern ], and partially spoken further afield in the area. Tsakonian evolved directly from Laconian (ancient Spartan) and therefore descends from ]. | ''Tsakonian'' ({{lang|grc|Τσακωνικά}}) is spoken in its full form today only in a small number of villages around the town of ] in the region of ] in the Southern ], and partially spoken further afield in the area. Tsakonian evolved directly from Laconian (ancient Spartan) and therefore descends from ]. | ||

| It has limited input from Hellenistic Koine and is significantly different from and not mutually intelligible with other Greek varieties (such as ] and ]). Some linguists consider it a separate language because of this. | It has limited input from Hellenistic Koine and is significantly different from and not mutually intelligible with other Greek varieties (such as ] and ]). Some linguists consider it a separate language because of this. | ||

| ===Greco-Australian=== | |||

| {{Main|Greco-Australian dialect}} | |||

| Greco-Australian is an Australian dialect of Greek that is spoken by the Greek diaspora of Australia, including Greek immigrants living in Australia and Australians of Greek descent.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://neoskosmos.com/en/2020/06/29/dialogue/opinion/tongues-of-greek-australia-an-anglicised-hellenic-language/|title=Tongues of Greek Australia: An Anglicised Hellenic language|last=Kalimniou|first=Dean|date=29 June 2020|access-date=22 October 2023|work=]}}</ref> | |||

| ==Phonology and orthography== | ==Phonology and orthography== | ||

| Line 139: | Line 146: | ||

| Modern Greek is written in the Greek alphabet, which has 24 letters, each with a capital and lowercase (small) form. The letter ] additionally has a special final form. There are two diacritical symbols, the ] which indicates ] and the ] marking a vowel letter as not being part of a ]. Greek has a mixed historical and phonemic ], where historical spellings are used if their pronunciation matches modern usage. The correspondence between consonant ]s and ]s is largely unique, but several of the vowels can be spelt in multiple ways.<ref>''cf.'' ]</ref> Thus ] is easy but ] is difficult.<ref>G. Th. Pavlidis and V. Giannouli, "Spelling Errors Accurately Differentiate USA-Speakers from Greek Dyslexics: Ιmplications for Causality and Treatment" ''in'' R.M. Joshi et al. (eds) ''Literacy Acquisition: The Role of Phonology, Morphology and Orthography''. Washington, 2003. {{ISBN|1-58603-360-3}}</ref> | Modern Greek is written in the Greek alphabet, which has 24 letters, each with a capital and lowercase (small) form. The letter ] additionally has a special final form. There are two diacritical symbols, the ] which indicates ] and the ] marking a vowel letter as not being part of a ]. Greek has a mixed historical and phonemic ], where historical spellings are used if their pronunciation matches modern usage. The correspondence between consonant ]s and ]s is largely unique, but several of the vowels can be spelt in multiple ways.<ref>''cf.'' ]</ref> Thus ] is easy but ] is difficult.<ref>G. Th. Pavlidis and V. Giannouli, "Spelling Errors Accurately Differentiate USA-Speakers from Greek Dyslexics: Ιmplications for Causality and Treatment" ''in'' R.M. Joshi et al. (eds) ''Literacy Acquisition: The Role of Phonology, Morphology and Orthography''. Washington, 2003. {{ISBN|1-58603-360-3}}</ref> | ||

| A number of ] were used until 1982, when they were officially dropped from Greek spelling as no longer corresponding to the modern pronunciation of the language. Monotonic orthography is today used in official usage, in schools and for most purposes of everyday writing in Greece. Polytonic orthography, besides being used for older varieties of Greek, is still used in book printing, especially for academic and ] purposes, and in everyday use by some conservative writers and elderly people. The Greek Orthodox Church continues to use polytonic and the late ]<ref name="Christodoulos">{{cite web |url=http://www.in.gr/news/article.asp?lngEntityID=708357 |title="Φιλιππικός" Χριστόδουλου κατά του μονοτονικού συστήματος | |

A number of ] were used until 1982, when they were officially dropped from Greek spelling as no longer corresponding to the modern pronunciation of the language. Monotonic orthography is today used in official usage, in schools and for most purposes of everyday writing in Greece. Polytonic orthography, besides being used for older varieties of Greek, is still used in book printing, especially for academic and ] purposes, and in everyday use by some conservative writers and elderly people. The Greek Orthodox Church continues to use polytonic and the late ]<ref name="Christodoulos">{{cite web |url=http://www.in.gr/news/article.asp?lngEntityID=708357 |title="Φιλιππικός" Χριστόδουλου κατά του μονοτονικού συστήματος |access-date=2007-02-23 |work=in.gr News }}</ref> and the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece<ref name="RelationsProject">{{cite web |url=http://www.in.gr/news/article.asp?lngEntityID=657799 |title=Την επαναφορά του πολυτονικού ζητά η Διαρκής Ιερά Σύνοδος |access-date=2007-02-23 |work=in.gr News }}</ref> have requested the reintroduction of polytonic as the official script. | ||

| The Greek vowel letters and digraphs with their pronunciations are: {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|α}}}} {{IPAslink|a}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ε, αι}}}} {{IPAslink|e}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|η, ι, υ, ει, οι, υι}}}} {{IPAslink|i}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ο, ω}}}} {{IPAslink|o}}, and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ου}}}} {{IPAslink|u}}. The digraphs {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|αυ}}}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ευ}}}} and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ηυ}}}} are pronounced {{IPA|/av/}}, {{IPA|/ev/}}, and {{IPA|/iv/}} respectively before vowels and voiced consonants, and {{IPA|/af/}}, {{IPA|/ef/}} and {{IPA|/if/}} respectively before voiceless consonants. | The Greek vowel letters and digraphs with their pronunciations are: {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|α}}}} {{IPAslink|a}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ε, αι}}}} {{IPAslink|e}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|η, ι, υ, ει, οι, υι}}}} {{IPAslink|i}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ο, ω}}}} {{IPAslink|o}}, and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ου}}}} {{IPAslink|u}}. The digraphs {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|αυ}}}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ευ}}}} and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ηυ}}}} are pronounced {{IPA|/av/}}, {{IPA|/ev/}}, and {{IPA|/iv/}} respectively before vowels and voiced consonants, and {{IPA|/af/}}, {{IPA|/ef/}} and {{IPA|/if/}} respectively before voiceless consonants. | ||

| The Greek letters {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|φ}}}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|β}}}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|θ}}}}, and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|δ}}}} are pronounced {{IPAslink|f}}, {{IPAslink|v}}, {{IPAslink|θ}}, and {{IPAslink|ð}} respectively. The letters {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γ}}}} and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|χ}}}} are pronounced {{IPAslink|ɣ}} and {{IPAslink|x}}, respectively. All those letters represent fricatives in Modern Greek, but they were used for occlusives with the same (or with a similar) articulation point in Ancient Greek. Before mid or close front vowels ({{IPAslink|e}} and {{IPAslink|i}}), |

The Greek letters {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|φ}}}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|β}}}}, {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|θ}}}}, and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|δ}}}} are pronounced {{IPAslink|f}}, {{IPAslink|v}}, {{IPAslink|θ}}, and {{IPAslink|ð}} respectively. The letters {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γ}}}} and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|χ}}}} are pronounced {{IPAslink|ɣ}} and {{IPAslink|x}}, respectively. All those letters represent fricatives in Modern Greek, but they were used for occlusives with the same (or with a similar) articulation point in Ancient Greek. Before mid or close front vowels ({{IPAslink|e}} and {{IPAslink|i}}), {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γ}}}} and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|χ}}}} are fronted, becoming {{IPAblink|ʝ}} and {{IPAblink|ç}}, respectively, which, in some dialects, notably those of Crete and ], are further fronted to {{IPAblink|ʑ}} or {{IPAblink|ʒ}} and {{IPAblink|ɕ}} or {{IPAblink|ʃ}}, respectively. Μoreover, before mid or close back vowels ({{IPAslink|o}} and {{IPAslink|u}}), {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γ}}}} tends to be pronounced further back than a prototypical velar, between a velar {{IPAblink|ɣ}} and an uvular {{IPAblink|ʁ}} (transcribed {{IPA|ɣ̄}}). The letter {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ξ}}}} stands for the sequence {{IPA|/ks/}} and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|ψ}}}} for {{IPA|/ps/}}. | ||

| The digraphs {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γγ}}}} and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γκ}}}} are generally pronounced {{IPAblink|ɡ}}, but are fronted to {{IPAblink|ɟ}} before front vowels ({{IPAslink|e}} and {{IPAslink|i}}) and tend to be pronounced {{IPA|}} before the back vowels ({{IPAslink|o}} and {{IPAslink|u}}). When these digraphs are preceded by a vowel, they are pronounced {{IPA|}} and {{IPA|}} before front vowels ({{IPAslink|e}} and {{IPAslink|i}}) and {{IPA|}} before the back ({{IPAslink|o}} and {{IPAslink|u}}). The digraph {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γγ}}}} may be pronounced {{IPA|}} in some words ({{IPA|}} before front vowels and {{IPA|}} before back ones). The pronunciation {{IPA|}} for the digraph {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γκ}}}} is extremely rare, but could be heard in literary and scholarly words or when reading ancient texts (by a few readers); normally it retains its "original" pronunciation {{IPA|}} only in the ] {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γκτ}}}}, where {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|τ}}}} prevents the sonorization of {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|κ}}}} by {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γ}}}} (hence {{IPA|}}). | The digraphs {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γγ}}}} and {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γκ}}}} are generally pronounced {{IPAblink|ɡ}}, but are fronted to {{IPAblink|ɟ}} before front vowels ({{IPAslink|e}} and {{IPAslink|i}}) and tend to be pronounced {{IPA|}} before the back vowels ({{IPAslink|o}} and {{IPAslink|u}}). When these digraphs are preceded by a vowel, they are pronounced {{IPA|}} and {{IPA|}} before front vowels ({{IPAslink|e}} and {{IPAslink|i}}) and {{IPA|}} before the back ({{IPAslink|o}} and {{IPAslink|u}}). The digraph {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γγ}}}} may be pronounced {{IPA|}} in some words ({{IPA|}} before front vowels and {{IPA|}} before back ones). The pronunciation {{IPA|}} for the digraph {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γκ}}}} is extremely rare, but could be heard in literary and scholarly words or when reading ancient texts (by a few readers); normally it retains its "original" pronunciation {{IPA|}} only in the ] {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γκτ}}}}, where {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|τ}}}} prevents the sonorization of {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|κ}}}} by {{angle bracket|{{lang|el|γ}}}} (hence {{IPA|}}). | ||

| Line 150: | Line 157: | ||

| {{main|Modern Greek grammar}} | {{main|Modern Greek grammar}} | ||

| ] in honor of ] island: ''Psaron (in genitive) Street, historic island of the 1821 Revolution'']] | ] in honor of ] island: ''Psaron (in genitive) Street, historic island of the 1821 Revolution'']] | ||

| Modern Greek is largely a ]. Modern Greek and Albanian are the only two modern Indo-European languages that retain a synthetic ] (the ] is a recent innovation based on a ] ]). | Modern Greek is largely a ]. Modern Greek and Albanian are the only two modern Indo-European languages that retain a synthetic ] (the ] is a recent innovation based on a ] ]). | ||

| Line 164: | Line 171: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ]s (except the perfect middle-passive participle) | * ]s (except the perfect middle-passive participle) | ||

| * third person imperative |

* third person imperative | ||

| * ] ] | |||

| Features gained: | Features gained: | ||

| Line 170: | Line 178: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] {{lang|grc|θα}} (a contraction of {{lang|grc|ἐθέλω ἵνα}} → {{lang|grc|θέλω να}} → {{lang|grc|θε' να}} → {{lang|grc|θα}}), which marks future tense and conditional mood | * ] {{lang|grc|θα}} (a contraction of {{lang|grc|ἐθέλω ἵνα}} → {{lang|grc|θέλω να}} → {{lang|grc|θε' να}} → {{lang|grc|θα}}), which marks future tense and conditional mood | ||

| * ] forms for certain verb forms | * ] forms for certain verb forms (in particular the perfect tense) | ||

| * ] distinction in future tense between imperfective (present) and perfective (aorist) | * ] distinction in future tense between imperfective (present) and perfective (aorist) | ||

| Line 177: | Line 185: | ||

| Most of these features are shared with other languages spoken in the Balkan peninsula (see ]), although Greek does not show all typical Balkan areal features, such as the postposed article. | Most of these features are shared with other languages spoken in the Balkan peninsula (see ]), although Greek does not show all typical Balkan areal features, such as the postposed article. | ||

| Because of the influence of Katharevousa, however, Demotic is not commonly used in its purest form. ]s are still widely used, especially in writing and in more formal speech, as well as in some everyday expressions, such as the dative {{lang|grc|εντάξει}} (' |

Because of the influence of Katharevousa, however, Demotic is not commonly used in its purest form. ]s are still widely used, especially in writing and in more formal speech, as well as in some everyday expressions, such as the dative {{lang|grc|εντάξει}} ('okay', literally 'in order') or the third person imperative {{lang|grc|ζήτω}}! ('long live!'). | ||

| ==Sample text== | ==Sample text== | ||

| The following is a sample text in Modern Greek of |

The following is a sample text in Modern Greek of Article 1 of the ] (by the ]): | ||

| {{fs interlinear |indent=2 |lang=el |glossing3=no |italics3=yes |ipa4=yes | |||

| |{'''Άρθρο 1:'''} Όλοι οι άνθρωποι γεννιούνται ελεύθεροι και ίσοι στην αξιοπρέπεια και τα δικαιώματα. Είναι προικισμένοι με λογική και συνείδηση, και οφείλουν να συμπεριφέρονται μεταξύ τους με πνεύμα αδελφοσύνης. | |||

| { |

|{'''Arthro 1:'''} Oloi oi anthropoi genniountai eleutheroi kai isoi stin axioprepeia kai ta dikaiomata. Einai proikismenoi me logiki kai syneidisi, kai ofeiloun na symperiferontai metaxy tous me pneuma adelfosynis. |c2=(]) | ||

| ⚫ | |{'''Árthro 1:'''} Óli i ánthropi yeniúnde eléftheri ke ísi stin aksioprépia ke ta dhikeómata. Íne prikizméni me loyikí ke sinídhisi, ke ofílun na simberiféronde metaksí tus me pnévma adhelfosínis. |c3= (]) | ||

| ⚫ | |{ |c4=(IPA) | ||

| ⚫ | { |

||

| ⚫ | |'''Article 1:''' All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. | ||

| }} | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| {{quote|'''Article 1:''' All the human beings are born free and equal in the dignity and the rights. Are endowed with reason and conscience, and have to behave between them with spirit of brotherhood.|Gloss|word-for-word}} | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} | |||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| Line 203: | Line 208: | ||

| |first=Νικόλαος Π. (Nikolaos P.) | |first=Νικόλαος Π. (Nikolaos P.) | ||

| |year=1995 | |year=1995 | ||

| |origyear= | |||

| |title=Ιστορία της ελληνικής γλώσσας: (τέσσερις μελέτες) (History of the Greek language: four studies) | |title=Ιστορία της ελληνικής γλώσσας: (τέσσερις μελέτες) (History of the Greek language: four studies) | ||

| |publisher=Ίδρυμα Τριανταφυλλίδη | |publisher=Ίδρυμα Τριανταφυλλίδη | ||

| Line 213: | Line 217: | ||

| |first=Mario | |first=Mario | ||

| |year=2001 | |year=2001 | ||

| |origyear= | |||

| |title=Storia della letteratura neogreca | |title=Storia della letteratura neogreca | ||

| |publisher=Carocci | |publisher=Carocci | ||

| Line 223: | Line 226: | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Wikibooks}} | {{Wikibooks}} | ||

| {{interwiki|code=el}} | |||

| * of the | * of the | ||

| * of the | * of the | ||

| * | * | ||

| Line 235: | Line 239: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721193520/http://www.czudovo.info/list.php?what=1&ln=el&in=from_en |date=2011-07-21 }} | ||

| '''Grammar''' | '''Grammar''' | ||

| * | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190711155808/http://www.ilsp.gr/files/basic_greek_grammar.pdf |date=2019-07-11 }}{{deadlink|date=May 2022}} | ||

| '''Institutes''' | '''Institutes''' | ||

| Line 249: | Line 253: | ||

| {{Greek language}} | {{Greek language}} | ||

| {{Greek language periods}} | {{Greek language periods}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:58, 14 November 2024

Dialects and varieties of the Greek language spoken in the modern era| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Modern Greek" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Modern Greek | |

|---|---|

| Νέα Ελληνικά | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈne.a eliniˈka] |

| Native to | Greece Cyprus Albania (Southern Albania) Turkey (Anatolia) Italy (Calabria, Salento) |

| Region | Eastern Mediterranean |

| Ethnicity | Greeks |

| Native speakers | 13.4 million (2012) |

| Language family | Indo-European |

| Early forms | Proto-Greek |

| Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Writing system | Greek alphabet Greek Braille |

| Official status | |

| Official language in | |

| Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Center for the Greek Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | el |

| ISO 639-2 | gre (B) ell (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | ell |

| Glottolog | mode1248 |

| Linguasphere | part of 56-AAA-a |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. | |

Modern Greek (endonym: Νέα Ελληνικά, Néa Elliniká [ˈne.a eliniˈka] or Κοινή Νεοελληνική Γλώσσα, Kiní Neoellinikí Glóssa), generally referred to by speakers simply as Greek (Ελληνικά, Elliniká), refers collectively to the dialects of the Greek language spoken in the modern era, including the official standardized form of the language sometimes referred to as Standard Modern Greek. The end of the Medieval Greek period and the beginning of Modern Greek is often symbolically assigned to the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, even though that date marks no clear linguistic boundary and many characteristic features of the modern language arose centuries earlier, having begun around the fourth century AD.

During most of the Modern Greek period, the language existed in a situation of diglossia, with regional spoken dialects existing side by side with learned, more archaic written forms, as with the vernacular and learned varieties (Dimotiki and Katharevousa) that co-existed in Greece throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Varieties

Main article: Varieties of Modern GreekVarieties of Modern Greek include Demotic, Katharevousa, Pontic, Cappadocian, Mariupolitan, Southern Italian, Yevanic, Tsakonian and Greco-Australian.

Demotic

Main article: Demotic GreekStrictly speaking, Demotic or Dimotiki (Δημοτική), refers to all popular varieties of Modern Greek that followed a common evolutionary path from Koine and have retained a high degree of mutual intelligibility to the present. As shown in Ptochoprodromic and Acritic poems, Demotic Greek was the vernacular already before the 11th century and called the "Roman" language of the Byzantine Greeks, notably in peninsular Greece, the Greek islands, coastal Asia Minor, Constantinople, and Cyprus.

Today, a standardized variety of Demotic Greek is the official language of Greece and Cyprus, and is referred to as "Standard Modern Greek", or less strictly simply as "Greek", "Modern Greek", or "Demotic".

Demotic Greek comprises various regional varieties with minor linguistic differences, mainly in phonology and vocabulary. Due to the high degree of mutual intelligibility of these varieties, Greek linguists refer to them as "idioms" of a wider "Demotic dialect", known as "Koine Modern Greek" (Koiní Neoellinikí - 'common Neo-Hellenic'). Most English-speaking linguists however refer to them as "dialects", emphasizing degrees of variation only when necessary. Demotic Greek varieties are divided into two main groups, Northern and Southern.

The main distinguishing feature common to Northern variants is a set of standard phonological shifts in unaccented vowel phonemes: becomes , becomes , and and are dropped. The dropped vowels' existence is implicit, and may affect surrounding phonemes: for example, a dropped palatalizes preceding consonants, just like an that is pronounced. Southern variants do not exhibit these phonological shifts.

Examples of Northern dialects are Rumelian (Constantinople), Epirote, Macedonian, Thessalian, Thracian, Northern Euboean, Sporades, Samos, Smyrna, and Sarakatsanika. The Southern category is divided into groups that include:

- Old Athenian-Maniot: Megara, Aegina, Athens, Cyme (Old Athenian) and Mani Peninsula (Maniot)

- Ionian-Peloponnesian: Peloponnese (except Mani), Ionian Islands, Attica, Boeotia, and Southern Euboea

- Cretan-Cycladian: Cyclades, Crete, and several enclaves in Syria and Lebanon

- Southeastern: Chios, Ikaria, Dodecanese, and Cyprus.

Demotic Greek has officially been taught in monotonic Greek script since 1982.

Katharevousa

Main article: KatharevousaKatharevousa (Καθαρεύουσα) is a sociolect promoted in the 19th century at the foundation of the modern Greek state, as a compromise between Classical Greek and modern Demotic. It was the official language of modern Greece until 1976.

Katharevousa is written in polytonic Greek script. Also, while Demotic Greek contains loanwords from Turkish, Italian, Latin, and other languages, these have for the most part been purged from Katharevousa. See also the Greek language question.

Pontic

Main article: Pontic Greek

Pontic (Ποντιακά) was originally spoken along the mountainous Black Sea coast of Turkey, the so-called Pontus region, until most of its speakers were killed or displaced to modern Greece during the Pontic genocide (1919–1921), followed later by the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923. (Small numbers of Muslim speakers of Pontic Greek escaped these events and still reside in the Pontic villages of Turkey.) It derives from Hellenistic and Medieval Koine and preserves characteristics of Ionic due to ancient colonizations of the region. Pontic evolved as a separate dialect from Demotic Greek as a result of the region's isolation from the Greek mainstream after the Fourth Crusade fragmented the Byzantine Empire into separate kingdoms (see Empire of Trebizond).

Cappadocian

Main article: Cappadocian GreekCappadocian (Καππαδοκικά) is a Greek dialect of central Turkey of the same fate as Pontic; its speakers settled in mainland Greece after the Greek genocide (1919–1921) and the later Population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923. Cappadocian Greek diverged from the other Byzantine Greek dialects earlier, beginning with the Turkish conquests of central Asia Minor in the 11th and 12th centuries, and so developed several radical features, such as the loss of the gender for nouns. Having been isolated from the crusader conquests (Fourth Crusade) and the later Venetian influence of the Greek coast, it retained the Ancient Greek terms for many words that were replaced with Romance ones in Demotic Greek. The poet Rumi, whose name means "Roman", referring to his residence amongst the "Roman" Greek speakers of Cappadocia, wrote a few poems in Cappadocian Greek, one of the earliest attestations of the dialect.

Mariupolitan

Main article: Mariupol GreekRuméika (Ρωμαίικα) or Mariupolitan Greek is a dialect spoken in about 17 villages around the northern coast of the Sea of Azov in southern Ukraine and Russia. Mariupolitan Greek is closely related to Pontic Greek and evolved from the dialect of Greek spoken in Crimea, which was a part of the Byzantine Empire and then the Pontic Empire of Trebizond, until that latter state fell to the Ottomans in 1461. Thereafter, the Crimean Greek state continued to exist as the independent Greek Principality of Theodoro. The Greek-speaking inhabitants of Crimea were deported by Catherine the Great to resettle in the new city of Mariupol after the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) to escape the then Muslim-dominated Crimea. Mariupolitan's main features have certain similarities with both Pontic (e.g. the lack of synizesis of -ía, éa) and the northern varieties of the core dialects (e.g. the northern vocalism).

Southern Italian

Southern Italian or Italiot (Κατωιταλιώτικα) comprises both Calabrian and Griko varieties, spoken by around 15 villages in the regions of Calabria and Apulia. The Southern Italian dialect is the last living trace of Hellenic elements in Southern Italy that once formed Magna Graecia. Its origins can be traced to the Dorian Greek settlers who colonised the area from Sparta and Corinth in 700 BC.

It has received significant Koine Greek influence through Byzantine Greek colonisers who re-introduced Greek language to the region, starting with Justinian's conquest of Italy in late antiquity and continuing through the Middle Ages. Griko and Demotic are mutually intelligible to some extent, but the former shares some common characteristics with Tsakonian.

Yevanic

Main article: Yevanic languageYevanic (יעואניקה, Γεβανικά) is an almost extinct language of Romaniote Jews. The language was already in decline for centuries until most of its speakers were killed in the Holocaust. Afterward, the language was mostly kept by remaining Romaniote emigrants to Israel, where it was displaced by modern Hebrew.

Tsakonian

Main article: Tsakonian languageTsakonian (Τσακωνικά) is spoken in its full form today only in a small number of villages around the town of Leonidio in the region of Arcadia in the Southern Peloponnese, and partially spoken further afield in the area. Tsakonian evolved directly from Laconian (ancient Spartan) and therefore descends from Doric Greek.

It has limited input from Hellenistic Koine and is significantly different from and not mutually intelligible with other Greek varieties (such as Demotic Greek and Pontic Greek). Some linguists consider it a separate language because of this.

Greco-Australian

Main article: Greco-Australian dialectGreco-Australian is an Australian dialect of Greek that is spoken by the Greek diaspora of Australia, including Greek immigrants living in Australia and Australians of Greek descent.

Phonology and orthography

Main articles: Modern Greek phonology, Greek orthography, and Greek alphabetA series of radical sound changes starting in Koine Greek has led to a phonological system in Modern Greek that is significantly different from that of Ancient Greek. Instead of the complex vowel system of Ancient Greek, with its four vowel-height levels, length distinction, and multiple diphthongs, Modern Greek has a simple system of five vowels. This came about through a series of mergers, especially towards /i/ (iotacism).

Modern Greek consonants are plain (voiceless unaspirated) stops, voiced stops, or voiced and unvoiced fricatives. Modern Greek has not preserved length in vowels or consonants.

| Greek alphabet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Archaic local variants

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diacritics and other symbols | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diacritics Ligatures Numerals (Attic) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Modern Greek is written in the Greek alphabet, which has 24 letters, each with a capital and lowercase (small) form. The letter sigma additionally has a special final form. There are two diacritical symbols, the acute accent which indicates stress and the diaeresis marking a vowel letter as not being part of a digraph. Greek has a mixed historical and phonemic orthography, where historical spellings are used if their pronunciation matches modern usage. The correspondence between consonant phonemes and graphemes is largely unique, but several of the vowels can be spelt in multiple ways. Thus reading is easy but spelling is difficult.

A number of diacritical signs were used until 1982, when they were officially dropped from Greek spelling as no longer corresponding to the modern pronunciation of the language. Monotonic orthography is today used in official usage, in schools and for most purposes of everyday writing in Greece. Polytonic orthography, besides being used for older varieties of Greek, is still used in book printing, especially for academic and belletristic purposes, and in everyday use by some conservative writers and elderly people. The Greek Orthodox Church continues to use polytonic and the late Christodoulos of Athens and the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece have requested the reintroduction of polytonic as the official script.

The Greek vowel letters and digraphs with their pronunciations are: ⟨α⟩ /a/, ⟨ε, αι⟩ /e/, ⟨η, ι, υ, ει, οι, υι⟩ /i/, ⟨ο, ω⟩ /o/, and ⟨ου⟩ /u/. The digraphs ⟨αυ⟩, ⟨ευ⟩ and ⟨ηυ⟩ are pronounced /av/, /ev/, and /iv/ respectively before vowels and voiced consonants, and /af/, /ef/ and /if/ respectively before voiceless consonants.

The Greek letters ⟨φ⟩, ⟨β⟩, ⟨θ⟩, and ⟨δ⟩ are pronounced /f/, /v/, /θ/, and /ð/ respectively. The letters ⟨γ⟩ and ⟨χ⟩ are pronounced /ɣ/ and /x/, respectively. All those letters represent fricatives in Modern Greek, but they were used for occlusives with the same (or with a similar) articulation point in Ancient Greek. Before mid or close front vowels (/e/ and /i/), ⟨γ⟩ and ⟨χ⟩ are fronted, becoming [ʝ] and [ç], respectively, which, in some dialects, notably those of Crete and Mani, are further fronted to [ʑ] or [ʒ] and [ɕ] or [ʃ], respectively. Μoreover, before mid or close back vowels (/o/ and /u/), ⟨γ⟩ tends to be pronounced further back than a prototypical velar, between a velar [ɣ] and an uvular [ʁ] (transcribed ɣ̄). The letter ⟨ξ⟩ stands for the sequence /ks/ and ⟨ψ⟩ for /ps/.

The digraphs ⟨γγ⟩ and ⟨γκ⟩ are generally pronounced [ɡ], but are fronted to [ɟ] before front vowels (/e/ and /i/) and tend to be pronounced before the back vowels (/o/ and /u/). When these digraphs are preceded by a vowel, they are pronounced and before front vowels (/e/ and /i/) and before the back (/o/ and /u/). The digraph ⟨γγ⟩ may be pronounced in some words ( before front vowels and before back ones). The pronunciation for the digraph ⟨γκ⟩ is extremely rare, but could be heard in literary and scholarly words or when reading ancient texts (by a few readers); normally it retains its "original" pronunciation only in the trigraph ⟨γκτ⟩, where ⟨τ⟩ prevents the sonorization of ⟨κ⟩ by ⟨γ⟩ (hence ).

Syntax and morphology

Main article: Modern Greek grammar

Modern Greek is largely a synthetic language. Modern Greek and Albanian are the only two modern Indo-European languages that retain a synthetic passive (the North Germanic passive is a recent innovation based on a grammaticalized reflexive pronoun).

Differences from Classical Greek

Modern Greek has changed from Classical Greek in morphology and syntax, losing some features and gaining others.

Features lost:

- dative case

- optative mood

- infinitive

- dual number

- participles (except the perfect middle-passive participle)

- third person imperative

- reduplicative perfect

Features gained:

- gerund

- modal particle θα (a contraction of ἐθέλω ἵνα → θέλω να → θε' να → θα), which marks future tense and conditional mood

- auxiliary verb forms for certain verb forms (in particular the perfect tense)

- aspectual distinction in future tense between imperfective (present) and perfective (aorist)

Modern Greek has developed a simpler system of grammatical prefixes marking tense and aspect of a verb, such as augmentation and reduplication, and has lost some patterns of noun declension and some distinct forms in the declensions.

Most of these features are shared with other languages spoken in the Balkan peninsula (see Balkan sprachbund), although Greek does not show all typical Balkan areal features, such as the postposed article.

Because of the influence of Katharevousa, however, Demotic is not commonly used in its purest form. Archaisms are still widely used, especially in writing and in more formal speech, as well as in some everyday expressions, such as the dative εντάξει ('okay', literally 'in order') or the third person imperative ζήτω! ('long live!').

Sample text

The following is a sample text in Modern Greek of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (by the United Nations):

Άρθρο 1:

Arthro 1:

Árthro 1:

(IPA)

{Άρθρο 1:} Όλοι οι άνθρωποι γεννιούνται ελεύθεροι και ίσοι στην αξιοπρέπεια και τα δικαιώματα. Είναι προικισμένοι με λογική και συνείδηση, και οφείλουν να συμπεριφέρονται μεταξύ τους με πνεύμα αδελφοσύνης.

{Arthro 1:} Oloi oi anthropoi genniountai eleutheroi kai isoi stin axioprepeia kai ta dikaiomata. Einai proikismenoi me logiki kai syneidisi, kai ofeiloun na symperiferontai metaxy tous me pneuma adelfosynis.

{Árthro 1:} Óli i ánthropi yeniúnde eléftheri ke ísi stin aksioprépia ke ta dhikeómata. Íne prikizméni me loyikí ke sinídhisi, ke ofílun na simberiféronde metaksí tus me pnévma adhelfosínis.

{

Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

References

- (protected language)

- "Greek". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (18 ed.). 2015.

- Jeffries, Ian (2002). Eastern Europe at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century: A Guide to the Economies in Transition. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-415-23671-3.

It is difficult to know how many ethnic Greeks there are in Albania. The Greek government, it is typically claimed, says there are around 300,000 ethnic Greeks in Albania, but most Western estimates are around the 200,000 mark ...

- ^ "Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 - European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages". Official Website of the Council of Europe. Council of Europe. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Greek in Hungary". Database for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Public Foundation for European Comparative Minority Research. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- "Italy: Cultural Relations and Greek Community". Hellenic Republic: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9 July 2013.

The Greek Italian community numbers some 30,000 and is concentrated mainly in central Italy. The age-old presence in Italy of Italians of Greek descent – dating back to Byzantine and Classical times – is attested to by the Griko dialect, which is still spoken in the Magna Graecia region. This historically Greek-speaking villages are Condofuri, Galliciano, Roccaforte del Greco, Roghudi, Bova and Bova Marina, which are in the Calabria region (the capital of which is Reggio). The Grecanic region, including Reggio, has a population of some 200,000, while speakers of the Griko dialect number fewer that 1,000 persons.

- "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 - Chapter 1: Founding Provisions". www.gov.za. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Tsitselikis, Konstantinos (2013). "A Surviving Treaty: The Lausanne Minority Protection in Greece and Turkey". In Henrard, Kristin (ed.). The Interrelation between the Right to Identity of Minorities and their Socio-economic Participation. Leiden and Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 294–295. ISBN 9789004244740..

- Based on: Brian Newton: The Generative Interpretation of Dialect. A Study of Modern Greek Phonology, Cambridge 1972, ISBN 0-521-08497-0

- Dimitriadis, Alexis (1999). "On Clitics, Prepositions and Case Licensing in Standard and Macedonian Greek". In Alexiadou, Artemis; Horrocks, Geoffrey C.; Stavrou, Melita (eds.). Studies in Greek Syntax. Springer. ISBN 9780792352907.

- ^ Dawkins, R.M. (1916). Modern Greek in Asia Minor. A study of dialect of Silli, Cappadocia and Pharasa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Δέδες, Δ. 1993. Ποιήματα του Μαυλανά Ρουμή. Τα Ιστορικά 10.18–19: 3–22. (in Greek)

- Meyer, G. 1895. Die griechischen Verse in Rabâbnâma. Byzantinische Zeitschrift 4: 401–411. (in German)

- "Greek Verses of Rumi & Sultan Walad". Archived from the original on 8 October 2017.

- The Greek Poetry of Jalaluddin Rumi

- Dawkins, Richard M. "The Pontic dialect of Modern Greek in Asia Minor and Russia". Transactions of the Philological Society 36.1 (1937): 15–52.

- "Greeks of the Steppe". The Washington Post. 10 November 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Kontosopoulos (2008), 109

- Kalimniou, Dean (29 June 2020). "Tongues of Greek Australia: An Anglicised Hellenic language". Neos Kosmos. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- cf. Iotacism

- G. Th. Pavlidis and V. Giannouli, "Spelling Errors Accurately Differentiate USA-Speakers from Greek Dyslexics: Ιmplications for Causality and Treatment" in R.M. Joshi et al. (eds) Literacy Acquisition: The Role of Phonology, Morphology and Orthography. Washington, 2003. ISBN 1-58603-360-3

- ""Φιλιππικός" Χριστόδουλου κατά του μονοτονικού συστήματος". in.gr News. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- "Την επαναφορά του πολυτονικού ζητά η Διαρκής Ιερά Σύνοδος". in.gr News. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

Further reading

- Ανδριώτης (Andriotis), Νικόλαος Π. (Nikolaos P.) (1995). Ιστορία της ελληνικής γλώσσας: (τέσσερις μελέτες) (History of the Greek language: four studies). Θεσσαλονίκη (Thessaloniki): Ίδρυμα Τριανταφυλλίδη. ISBN 960-231-058-8.

- Vitti, Mario (2001). Storia della letteratura neogreca. Roma: Carocci. ISBN 88-430-1680-6.

External links

- Portal for the Greek Language (modern & ancient) of the Center for the Greek Language

- Hellenic National Corpus of the Institute for Language & Speech Processing

- Audio example of Modern Greek

Courses

- Online course "Filoglossia" by ILSP

- Greek online course "Greek by Radio" from Cyprus radio broadcasting CyBC in English, 105 lessons with Real audio files

Dictionaries and glossaries

- Greek–English Dictionary Georgacas for Modern Greek Literature

- Triantafyllides Dictionary for Standard Modern Greek (Lexicon of the Modern Greek Koine)

- Modern Greek - English glossary

- English–Greek Dictionary (Modern Greek) Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

Grammar

- Illustrated Modern Greek grammar Archived 2019-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

Institutes

- Official website of the Center for the Greek Language

- Institute of Modern Greek Studies of the Manolis Triandaphyllidis Foundation at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

- Center for the Research of the Modern Greek Dialects and Idioms of the Academy of Athens (modern)

- The Cyprus Linguistics Society (CyLing)

- Institute for Language & Speech Processing

| Greek language | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin and genealogy | |||||||

| Periods |

| ||||||

| Varieties |

| ||||||

| Phonology | |||||||

| Grammar | |||||||

| Writing systems | |||||||

| Literature | |||||||

| Promotion and study | |||||||

| Other | |||||||

| Ages of Greek | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||