| Revision as of 15:04, 11 June 2014 editCFCF (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers35,041 edits →Structure: fixed ambiquity← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:12, 11 June 2014 edit undoSnowmanradio (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers118,298 edits word choice - not complete protection against ca of cxNext edit → | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| The cervical canal is a passage through which ] must travel to fertilise an ] after sexual intercourse. Several methods of contraception, including ]s and ]s aim to block or prevent the passage of sperm through the cervical canal. Cervical mucus is used in several methods of fertility awareness, such as the ] and ], due to its changes in consistency throughout the ]. During vaginal ], the cervix must flatten and ] to allow the ] to progress along the birth canal. Midwives and doctors use the extent of the dilation of the cervix to assess the progress of labour. | The cervical canal is a passage through which ] must travel to fertilise an ] after sexual intercourse. Several methods of contraception, including ]s and ]s aim to block or prevent the passage of sperm through the cervical canal. Cervical mucus is used in several methods of fertility awareness, such as the ] and ], due to its changes in consistency throughout the ]. During vaginal ], the cervix must flatten and ] to allow the ] to progress along the birth canal. Midwives and doctors use the extent of the dilation of the cervix to assess the progress of labour. | ||

| The endocervical canal is lined with ] and the ectocervix is covered with ]. The two types of epithelium meet at a junction known as the transformation zone. Infection with the ] (HPV) can cause changes in the epithelium, which can lead to invasive cancer of the cervix. ] tests can often detect precursors of invasive ] and enable early successful treatment. ], developed in the early 21st century, can be given to |

The endocervical canal is lined with ] and the ectocervix is covered with ]. The two types of epithelium meet at a junction known as the transformation zone. Infection with the ] (HPV) can cause changes in the epithelium, which can lead to invasive cancer of the cervix. ] tests can often detect precursors of invasive ] and enable early successful treatment. ], developed in the early 21st century, can be given to combat HPV infection. | ||

| ==Structure== | ==Structure== | ||

Revision as of 19:12, 11 June 2014

| Cervix | |

|---|---|

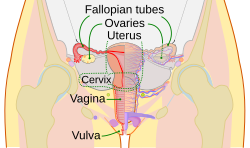

The female reproductive system. The cervix is part of the uterus. The cervical canal connects the interiors of the uterus and vagina. The female reproductive system. The cervix is part of the uterus. The cervical canal connects the interiors of the uterus and vagina. | |

| File:Female reproductive system lateral nolabel.png1: Fallopian tube, 2: bladder, 3: pubic bone, 4: vagina–G-Spot, 5: clitoris, 6: urethra, 7: vagina, 8: ovary, 9: sigmoid colon, 10: uterus, 11: fornix, 12: cervix, 13: rectum, 14: anus | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Müllerian duct |

| Artery | Vaginal artery and uterine artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cervix uteri |

| MeSH | D002584 |

| TA98 | A09.1.03.010 |

| TA2 | 3508 |

| FMA | 17740 |

| Anatomical terminology[edit on Wikidata] | |

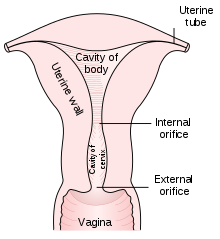

The cervix (Template:Lang-la) or cervix uteri is the lower part of the uterus and hence part of the female reproductive system. Roughly cylindrical in shape, in the adult it is usually between two and three centimetres long with the lower part bulging into the top of the vagina. The cervix has a central canal and an internal and external opening. The ectocervix is the portion of the cervix exposed to the vagina, and the endocervix the part of the cervix beyond the external opening. The cervix has been documented anatomically since at least the time of Hippocrates, over 2,000 years ago.

The cervical canal is a passage through which sperm must travel to fertilise an egg cell after sexual intercourse. Several methods of contraception, including cervical caps and cervical diaphragms aim to block or prevent the passage of sperm through the cervical canal. Cervical mucus is used in several methods of fertility awareness, such as the Creighton Model and Billings Method, due to its changes in consistency throughout the menstrual period. During vaginal childbirth, the cervix must flatten and dilate to allow the fetus to progress along the birth canal. Midwives and doctors use the extent of the dilation of the cervix to assess the progress of labour.

The endocervical canal is lined with a layer of column-shaped cells and the ectocervix is covered with multiple layers of cells topped with flat cells. The two types of epithelium meet at a junction known as the transformation zone. Infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV) can cause changes in the epithelium, which can lead to invasive cancer of the cervix. Cervical cytology tests can often detect precursors of invasive cervical cancer and enable early successful treatment. HPV vaccines, developed in the early 21st century, can be given to combat HPV infection.

Structure

The cervix is part of the female reproductive system. It is the lower narrower part of the uterus continuous above with the broader upper part of the uterus, which is called the body of the uterus. The lower end of the cervix bulges into the anterior wall of the vagina. In front of the upper part of the cervix lies the bladder, separated from it by cellular connective tissue known as parametrium, which also extends over the sides of the cervix. To the rear, the supravaginal cervix is covered by peritoneum, which runs onto the back of the vaginal wall and then turns upwards and onto the rectum forming the recto-uterine pouch. The cervix is more tightly connected to surrounding structures than the rest of the uterus. The cervix has a central canal, which has an external opening to the vagina, and an internal opening to the cavity of the body of the uterus. These openings are also known as the external os and internal os respectively. Part of the cervix protrudes into the vagina and is referred to as the ectocervix, and any portion of the cervix within the external opening and vagina is known as the endocervix. The cervix is 2–3 centimetres (0.79–1.18 in) long. Like the rest of the uterus, the cervix has three layers: a mucosal layer, a layer made up of smooth muscle, and a serosal layer. The cervix has more fibrous tissue including collagen and elastic tissue than the rest of the uterus.

The cervical canal varies greatly in length and width between women and over the course of a woman's life, and can measure 7–8 millimetres (0.3–0.3 in) at its widest diameter in pre-menopausal adults. The ectocervix has a convex, elliptical surface and is divided into anterior and posterior labia (lip-shaped structures). The size and shape of the external opening and the ectocervix can vary according to age, hormonal state, and whether natural or normal childbirth has taken place. Where no natural childbirth has taken place, the external os appears as a small, circular opening of about 8 millimetres (0.3 in). On average, the ectocervix is 3 centimetres (1.2 in) long and 2.5 centimetres (1 in) wide.

The cervix is supplied by the descending branch of the uterine artery and blood is drained into the uterine vein. The pelvic splanchnic nerves, emerging as S2–S3, transmit the sensation of pain from the cervix to the brain. These nerves travel along the uterosacral ligaments, which pass from the uterus to the anterior sacrum.

Three channels act to facilitate lymphatic drainage to the cervix. The anterior and lateral cervix drains to nodes along the uterine arteries, travelling along the cardinal ligaments at the base of the broad ligament to the external iliac lymph nodes and ultimately the paraaortic lymph nodes. The posterior and lateral cervix drains along the uterine arteries to the internal iliac lymph nodes and ultimately the paraaortic lymph nodes, and the posterior section of the cervix drains to the obturator and presacral lymph nodes.

After menstruation and directly under the influence of oestrogen, the cervix undergoes a series of changes in position and texture. During most of the menstrual cycle, the cervix remains firm, and is positioned low and closed. However, as ovulation approaches, the cervix becomes softer and rises to open in response to the higher levels of oestrogen present. These changes are also accompanied by changes in cervical mucus, described below.

Development

As a component of the female reproductive system, the cervix is derived from the two paramesonephric ducts, which develop around the sixth week of embryogenesis. During development, the outer parts of the two ducts fuse, forming a single urogenital canal that will become the vagina, cervix and uterus. The cervix grows in size at a smaller rate than the uterus, so the relative size of the cervix over time decreases, decreasing from being much larger than the body of the uterus in fetal life, twice as large during childhood, and decreasing to its adult size, smaller than the uterus, after puberty.

Histology

The epithelium of the cervix varies. The transformation zone, also referred to as the squamocolumnar junction, is adjacent to the borders of the ectocervix and the endocervix of the canal, and refers to the area where the change occurs between the stratified squamous epithelium lining the ectocervix and the simple columnar epithelium that lines the endocervix. The squamous epithelium of the ectocervix does not contain keratin, and is continuous with the adjacent vagina. Underlying both types of epithelium is a tough layer of collagen.

The transformation zone undergoes physiological changes at different times. At puberty, under hormonal influence the columnar epithelium extends outwards as the cervix grows. This causes the transformation zone to move outwards. Exposed to the lower pH of the vagina, the exposed columnar epithelia gradually undergoes metaplasia to a tougher squamous epithelia, and the transformation zone retreats slowly to its original position. This change is most marked after menopause, when the influence of hormones are reduced.

Function

Fertility

The cervical canal is a pathway through which sperm enter the uterus after sexual intercourse. Some sperm remains in cervical crypts, infoldings of the endocervix, which act as a reservoir, releasing sperm over several hours and maximising the changes of fertilisation. There is a theory the cervical and uterine contractions during orgasm draw semen into the uterus. Although the "upsuck theory" has been generally accepted for some years, it has been disputed due to lack of evidence, small sample size, and methodological errors.

Some methods of fertility awareness such as the Creighton Model and the Billings Method involve estimating a woman's periods of fertility and infertility by observing physiological changes in her body. Among these changes are several involving the quality of her cervical mucus: the sensation it causes at the vulva, its elasticity (Spinnbarkeit), its transparency, and the presence of ferning.

Childbirth

The cervix plays a major role in childbirth. As the foetus descends within the uterus in preparation for birth, the presenting part, usually the head, rests on and is supported by the cervix. As labour progresses, the cervix becomes softer and shorter, begins to dilate, and rotates to face anteriorly. The support the cervix provides to the foetal head starts to give way when the uterus begins its contractions. During childbirth, the cervix must dilate to a diameter of more than 10 centimetres (4 in) to accommodate the head of the foetus as it descends from the uterus to the vagina. In becoming wider, the cervix also becomes shorter, a phenomenon known as effacement. When this happens an area between the cervix and the vagina becomes exposed and is known as the birth canal.

Along with other factors, cervical dilation is used to divide childbirth into stages. Generally, the active first stage of labour is defined by a cervical dilation of more than 3–5 centimetres (1.2–2.0 in), with the second phase of labor defined when the cervix is dilated to more than 10 centimetres (3.9 in), which is regarded as its fullest dilation. The number of past vaginal deliveries is a strong factor in influencing how rapidly the cervix is able to dilate in labour. The time taken for the cervix to dilate and efface is one factor used in reporting systems such as the Bishop score, used to recommend whether interventions such as a forceps delivery, induction, or Caesarean section should be used in childbirth.

Cervical incompetence is a condition in which there is shortening of the cervix due to dilation and thinning, before term pregnancy. Short cervical length is the strongest predictor of preterm birth.

Cervical mucus

After a menstrual period ends, the external os is blocked by mucus that is thick and acidic. This "infertile" mucus blocks sperm from entering the uterus. For several days around the time of ovulation, "fertile" types of mucus are produced; they have a higher water content, and are less acidic and higher in electrolytes. These electrolytes cause the "ferning" pattern that can be observed in drying mucus under low magnification; as the mucus dries, the salts crystallize, resembling the leaves of a fern. The viscosity of mucus also changes over the menstrual cycle, with a stretchy character described as Spinnbarkeit most prominent around the time of ovulation.

Cervical mucus is produced by glands in the endocervix and is composed 90% of water. Depending on the water content, which varies during the menstrual cycle, the mucus functions either as a barrier or a transport medium to spermatozoa. During the proliferative phase, due to the effects of oestrogen the mucus is thin and serous to allow sper/m to enter the uterus, while during the secretory phase, due to the effects of progesterone the mucus is thick. Thick mucus also prevents pathogens from interfering with a nascent pregnancy. Cervical mucus contains electrolytes such as calcium, sodium and potassium; organic components such as glucose, amino acids and soluble proteins; trace elements including zinc, copper, iron, manganese and selenium; free fatty acids; enzymes such as amylase; and prostaglandins.

A cervical mucus plug, called the operculum, forms inside the cervical canal during pregnancy. This provides a protective seal for the uterus against the entry of pathogens and against leakage of uterine fluids. The mucus plug is also known to have antibacterial properties. This plug is released as the cervix dilates, either during the first stage of childbirth or shortly before. It is visible as a blood-tinged mucous discharge.

Contraception

Main article: Birth controlSeveral methods of contraception involve the cervix. Cervical diaphragms are small, reusable, firm-rimmed plastic devices inserted by a woman prior to intercourse that cover the cervix. Pressure against the walls of the vagina maintain the position of the diaphragm, and it acts as a physical barrier to prevent the entry of sperm into the uterus, preventing fertilisation. Cervical caps are a similar method, although they are smaller and adhere to the cervix via suction. Diaphragms and caps are often used in conjunction with spermicide. In one year, 12% of women using the diaphragm will undergo an unintended pregnancy, and with optimal use this falls to 6%. Efficacy rates are lower for the cap, with 18% of women undergoing an unintended pregnancy, and 10–13% with optimal use. Most methods of hormonal contraception, such as the oral contraceptive pill, work primarily by preventing ovulation, but their effectiveness is increased because they prevent the production of the types of cervical mucus that are conducive to fertilisation.

Clinical significance

Cancer

Main article: Cervical cancerIn 2008, cervical cancer was the third most common cancer in women worldwide, with rates varying geographically from less than 1 per 100,000 women to more than 50 cases per 100,000 women. Cervical cancer nearly always involves human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, and generally involves the ectocervix at the transformation zone. HPV is a virus with numerous strains, several of which predispose to dysplasia of cervical tissue, particularly in the transformation zone. This dysplasia increases the risk of cancer forming in the transformation zone, which is the most common area for cervical cancer to occur.

Potentially pre-cancerous changes in the cervix can be detected by a Pap smear (also called a cervical smear), in which epithelial cells are scraped from the surface of the cervix and examined under a microscope. In some parts of the developed world including the UK, the Pap test has been superseded with liquid-based cytology (LBC). A result of dysplasia is usually further investigated, such as by taking a cone biopsy, which may also remove the cancerous lesion. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is a possible result of the biopsy, and represents dysplastic changes that may eventually progress to invasive cancer. Most cases of cervical cancer are detected in this way, without having caused any symptoms. When symptoms occur, they may include vaginal bleeding, discharge, or discomfort. The introduction of pap smears has significantly reduced cancer mortality in developed countries, and most women who develop cervical cancer have never had a Pap smear, or have not had one within the last ten years. Vaccines against HPV, such as Gardasil and Cervarix, also reduce the incidence of cervical cancer, by inoculating against the viral strains involved in cancer development.

Inflammation

Main article: CervicitisInflammation of the cervix is referred to as cervicitis. This inflammation may be of the endocervix or ectocervix. When associated with the endocervix, it is associated with a mucousy vaginal discharge and the sexually transmitted infections such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea. Other causes include overgrowth of the commensal flora of the vagina. When associated with the ectocervix, inflammation may be caused by the herpes simplex virus. Inflammation is often investigated through directly visualising the cervix using a speculum, which may appear whiteish due to exudate, and by taking a Pap smear and examining for causal bacteria. Special tests may be used to identify particular bacteria. If the inflammation is due to a bacteria, then antibiotics may be given as treatment.

Anatomical abnormalities

Cervical stenosis refers to an abnormally narrow cervical canal, typically associated with trauma caused by removal of tissue for investigation or treatment of cancer, or cervical cancer itself. Diethylstilbestrol, used from 1938 to 1971 to prevent preterm labour and miscarriage, is also strongly associated with the development of cervical stenosis and other abnormalities in the daughters of the exposed women. Other abnormalities include vaginal adenosis, in which the squamous epithelia of the ectocervix becomes columnar, cancers such as clear cell adenocarcinomas, cervical ridges and hoods, and development of a "cockscomb" cervical appearance.

Cervical agenesis is a rare congenital condition in which the cervix completely fails to develop, often associated with the concurrent failure of the vagina to develop. Other congenital cervical abnormalities exist, often associated with abnormalities of the vagina and uterus. The cervix may be duplicated in situations such as bicornuate uterus and uterine didelphys.

Other

Nabothian cysts may develop from metaplasia, which often takes place in the transformation zone, and can cause the glands underlying the columnar epithelium to become blocked. Cervical polyps, which are benign overgrowths of endocervical tissue, if present may cause bleeding a benign overgrowth may be present in the endocervical canal. Cervical ectropion refers to the horizontal overgrowth of the endocervical columnar lining in a one-cell thick layer over the ectocervix.

History

The name of the cervix comes from Template:Lang-la (the neck) from the Proto-Indo-European root "ker-", referring to a "structure that projects". Thus the word cervix is linguistically related to the English word "horn", "head" (Template:Lang-sa), "head" (Template:Lang-el), and "deer" (Template:Lang-cy).

The cervix was documented in anatomical literature in at least the time of Hippocrates, although there was some variation in early writers, who used the term to refer to both the cervix and the internal uterine orifice. The first attested use of the word to refer to the cervix of the uterus was in 1702.

The colposcope, used in a colposcopy to visualise the cervix, was invented in 1925. The Pap smear was developed by Georgios Papanikolaou in 1928. A LEEP procedure using a heated loop of platinum to excise a patch of cervical tissue was developed by Aurel Babes in 1927.

Cervical cancer has been described for over 2,000 years, with descriptions provided by both Hippocrates and Aretaeus, although the causal role played by human papillomavirus (HPV) for cervical cancer was only elucidated in the late 20th century by Harald zur Hausen, who published a hypothesis in 1976, and whose hypothesis was confirmed in 1983 and 1984. Based on work done by Jian Zhou and Ian Fraser, a vaccine for four strains of HPV was released in 2006.

References

- ^ Gray, Henry (1980). Williams, Peter L; Warwick, Roger (eds.). Gray's Anatomy (36th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. pp. 1428–1431. ISBN 0-443-01505-8.

- ^ Gardner, Ernest (1969) . Anatomy: A Regional Study of Human Structure (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: W.B.Saunders. pp. 495–98.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Drake, Richard L. (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 415, 423. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kurman, edited by Robert J. (1994). Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract (Fourth Edition. ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 185–201. ISBN 978-1-4757-3889-6.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Daftary (2011). Manual of Obstretics, 3/e. Elsevier. pp. 1–16. ISBN 81-312-2556-9.

- ^ Ellis, Harold (2011). "Anatomy of the uterus". Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine. 12 (3): 99–101. doi:10.1016/j.mpaic.2010.11.005.

- ^ The cervix (2 ed. ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 2005. pp. Chapter 3. The Vascular, Neural and Lymphatic Anatomy of the Cervix. ISBN 9781405131377.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first1=has generic name (help);|first1=missing|last1=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first1=(help) - ^ Weschler, Toni (2006). Taking charge of your fertility : the definitive guide to natural birth control, pregnancy achievement, and reproductive health (Rev. ed. ed.). New York, NY: Collins. pp. 59, 64. ISBN 978-0-06-088190-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) Cite error: The named reference "Weschler" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ The cervix (2nd ed. ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. 2006. pp. 160–164. ISBN 978-1-4443-1275-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Larsen's human embryology (4th ed., Thoroughly rev. and updated. ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 2009. pp. "Development of the Urogenital system". ISBN 978-0-443-06811-9.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Deakin, Barbara Young ... ; drawings by Philip J.; et al. (2006). Wheater's functional histology : a text and colour atlas (5th ed. ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lowe, Alan Stevens, James S. (2005). Human histology (3rd ed. ed.). Philadelphia, Toronto: Elsevier Mosby. pp. 350–351. ISBN 0-323-03663-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wahl, Carter E. (2007). Hardcore pathology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 72. ISBN 9781405104982.

- ^ Hall, Arthur C. Guyton, John E. (2005). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed. ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. p. 1027. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brannigan, Robert E. (2008). "Sperm Transport and Capacitation". The Global Library of Women's Medicine. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10316.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Levin, Roy J. (November 2011). "The human female orgasm: a critical evaluation of its proposed reproductive functions". Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 26 (4): 301–314. doi:10.1080/14681994.2011.649692.

- Borrow, Amanda P. "The role of oxytocin in mating and pregnancy". Hormones and Behavior. 61 (3): 266–276. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.11.001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Williams obstetrics (22nd ed. ed.). New York ; Toronto: McGraw-Hill Professional. 2005. pp. 157–160, 537–539. ISBN 0-07-141315-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Goldenberg, Robert L. "Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth". The Lancet. 371 (9606): 75–84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Obstetric Data Definitions Issues and Rationale for Change" (PDF). 2012.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Check|first=value (help) - Su, Min. "Planned caesarean section decreases the risk of adverse perinatal outcome due to both labour and delivery complications in the Term Breech Trial". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 111 (10): 1065–1074. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00266.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Westinore, Ann; Evelyn, Billings (1998). The Billings Method: Controlling Fertility Without Drugs or Devices. Toronto: Life Cycle Books. p. 37. ISBN 0-919225-17-9.

- Anderson, Matthew; Karasz, Alison (2004). "Are Vaginal Symptoms Ever Normal? A Review of the Literature". Medscape General Medicine. 6 (4): 49.

- Wagner, G.; Levin, R. J. "Electrolytes in vaginal fluid during the menstrual cycle of coitally active and inactive women" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Becher, Naja (2009). "The cervical mucus plug: Structured review of the literature". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 88 (5): 502–513. doi:10.1080/00016340902852898.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Maternity nursing (7th ed. ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier Mosby. 2006. p. 394. ISBN 978-0-323-03366-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - NSW, Family Planning (2009). Contraception : healthy choices : a contraceptive clinic in a book (2nd ed. ed.). Sydney: UNSW Press. pp. 27–37. ISBN 978-1-74223-136-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Trussell, James (2011). "Contraceptive failure in the United States". Contraception. 83 (5): 397–404. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021.

- Trussell, J (May–Jun 1993). "Contraceptive efficacy of the diaphragm, the sponge and the cervical cap". Family planning perspectives. 25 (3): 100–5, 135. PMID 8354373.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Arbyn, M. (6 April 2011). "Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008". Annals of Oncology. 22 (12): 2675–2686. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins basic pathology (8th ed.). Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 716–21. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harrison's principles of internal medicine (17th ed. ed.). New York : McGraw-Hill Medical. 2008. pp. 608–609. ISBN 978-0-07-147692-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gray, Winifred; Kocjan, Gabrijela, eds. (2010). Diagnostic Cytopathology. Churchill Livingstone. p. 613.

- Cannistra, Stephen A. (18 April 1996). "Cancer of the Uterine Cervix". New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (16): 1030–1037. doi:10.1056/NEJM199604183341606.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed. ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 2010. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - World Health Organization (February 2006). "Fact sheet No. 297: Cancer". Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- Stamm, Walter (2013). The Practitioner's Handbook for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Seattle STD/HIV Prevention Training Center. pp. Chapter 7: Cervicitis.

- ^ Harrison's principles of internal medicine (17th ed. ed.). New York : McGraw-Hill Medical. 2008. pp. 828–829. ISBN 978-0-07-147692-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Valle, Rafael F. "Cervical Stenosis: A Challenging Clinical Entity". Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 18 (4): 129–143. doi:10.1089/104240602762555939.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Casey, Petra M. "Abnormal Cervical Appearance: What to Do, When to Worry?". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 86 (2): 147–151. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0512.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Fujimoto, Victor Y. "Congenital cervical atresia: Report of seven cases and review of the literature". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 177 (6): 1419–1425. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70085-1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Patton, PE (2004 Jun). "The diagnosis and reproductive outcome after surgical treatment of the complete septate uterus, duplicated cervix and vaginal septum". American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 190 (6): 1669–75, discussion 1675-8. PMID 15284765.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Harper, Douglas. "Cervix". Etymology Online. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Harper, Douglas. "Horn". Etymology Online. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Galen/Johnston (2011). Galen: On Diseases and Symptoms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-139-46084-2.

- ^ Gasparini, R; Panatto, D (May 29, 2009). "Cervical cancer: from Hippocrates through Rigoni-Stern to zur Hausen". Vaccine. 27 Suppl 1: A4-5. PMID 19480961.

- Diamantis, Aristidis (November 2010). "Different strokes: Pap-test and Babes method are not one and the same". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 38 (11): 857–859. doi:10.1002/dc.21347.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - McIntyre, Peter (July–August 2006). "Finding the viral link: the story of Harald zur Hausen" (PDF). Cancer World: 32–37.

- McLemore, Monica R. (1 October 2006). "Gardasil®: Introducing the New Human Papillomavirus Vaccine". Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 10 (5): 559–560. doi:10.1188/06.CJON.559-560.

External links

Media related to Cervix uteri at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cervix uteri at Wikimedia Commons

| Female reproductive system | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Blood supply | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||