| Revision as of 02:50, 17 February 2018 view sourceL293D (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers34,889 editsm Reverted edits by Shibushivam (talk): addition of unsourced content (HG) (3.3.3)Tags: Huggle Rollback← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:44, 17 February 2018 view source 39.60.32.182 (talk) →Partition and invasionTags: references removed Mobile edit Mobile web editNext edit → | ||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

| ===Partition and invasion=== | ===Partition and invasion=== | ||

| British rule in the Indian subcontinent ended in 1947 with the creation of new states: the ] and the ], as the successor states to ]. The ] over the 562 Indian ]s ended. According to the ], "the suzerainty of His Majesty over the Indian States lapses, and with it, all treaties and agreements in force at the date of the passing of this Act between His Majesty and the rulers of Indian States".<ref name=IIA1947>{{cite web |title=Indian Independence Act 1947 |url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/10-11/30 |website=UK Legislation |publisher=The National Archives |accessdate=14 September 2015}}</ref> States were thereafter left to choose whether to join India or Pakistan or to remain independent. Jammu and Kashmir, the largest of the princely states, had a predominantly Muslim population ruled by the Hindu ] ]. He decided to stay independent because he expected that the State's Muslims would be unhappy with accession to India, and the Hindus and Sikhs would become vulnerable if he joined Pakistan.<ref name=Kak>{{citation |first=Rakesh |last=Ankit |title=Pandit Ramchandra Kak: The Forgotten Premier of Kashmir |journal=Epilogue |volume=4 |number=4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZzEAFgW8TYwC&pg=PA36 |publisher=Epilogue -Jammu Kashmir |pages=36–39 |date=April 2010 |ref={{sfnref|Ankit, Pandit Ramchandra Kak|2010}}}} | British rule in the Indian subcontinent ended in 1947 with the creation of new states: the ] and the ], as the successor states to ]. The ] over the 562 Indian ]s ended. According to the ], "the suzerainty of His Majesty over the Indian States lapses, and with it, all treaties and agreements in force at the date of the passing of this Act between His Majesty and the rulers of Indian States".<ref name=IIA1947>{{cite web |title=Indian Independence Act 1947 |url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/10-11/30 |website=UK Legislation |publisher=The National Archives |accessdate=14 September 2015}}</ref> States were thereafter left to choose whether to join India or Pakistan or to remain independent. Jammu and Kashmir, the largest of the princely states, had a predominantly Muslim population ruled by the Hindu ] ]. He decided to stay independent because he expected that the State's Muslims would be unhappy with accession to India, and the Hindus and Sikhs would become vulnerable if he joined Pakistan.<ref name=Kak>{{citation |first=Rakesh |last=Ankit |title=Pandit Ramchandra Kak: The Forgotten Premier of Kashmir |journal=Epilogue |volume=4 |number=4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZzEAFgW8TYwC&pg=PA36 |publisher=Epilogue -Jammu Kashmir |pages=36–39 |date=April 2010 |ref={{sfnref|Ankit, Pandit Ramchandra Kak|2010}}}} | ||

| </ref><ref name=Scott>{{cite journal |author=Rakesh Ankit |title=Henry Scott: The forgotten soldier of Kashmir |journal=Epilogue |volume=4 |number=5 |url=http://documents.mx/documents/epilogue-magazine-may-2010.html |date=May 2010 |pages=44–49 |ref={{sfnref|Ankit, Henry Scott|2010}}}}</ref> On 11 August, the Maharaja dismissed his prime minister ], who had advocated independence. Observers and scholars interpret this action as a tilt towards accession to India.{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|p=106}}<ref name=Scott/ |

</ref><ref name=Scott>{{cite journal |author=Rakesh Ankit |title=Henry Scott: The forgotten soldier of Kashmir |journal=Epilogue |volume=4 |number=5 |url=http://documents.mx/documents/epilogue-magazine-may-2010.html |date=May 2010 |pages=44–49 |ref={{sfnref|Ankit, Henry Scott|2010}}}}</ref> On 11 August, the Maharaja dismissed his prime minister ], who had advocated independence. Observers and scholars interpret this action as a tilt towards accession to India.{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|p=106}}<ref name=Scott/ | ||

| ⚫ | The Jammu division of the state got caught up in the Partition violence. Large numbers of Hindus and Sikhs from ] and ] started arriving in March 1947, bringing "harrowing stories of Muslim atrocities." This provoked ], which had "many parallels with that in Sialkot." According to scholar Ilyas Chattha.{{sfn|Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath|2009|pp=179–180}} The violence in the eastern districts of Jammu that started in September, developed into a widespread ] around the October, organised by the Hindu Dogra troops of the State and perpetrated by the local Hindus, including members of the ], and the Hindus and Sikhs displaced from the neighbouring areas of West Pakistan. The Maharaja himself was implicated in some instances. A large number of Muslims were killed. Huge number of Muslims have fled to West Pakistan, some of whom made their way to the western districts of Poonch and Mirpur, which were ]. Many of these Muslims believed that the Maharaja ordered the killings in Jammu and instigated the Muslims in West Pakistan to join the ] and help in the formation of the Azad Kashmir government.{{sfn|Snedden, Kashmir The Unwritten History|2013|pp=48–57}} | ||

| Pakistan made various efforts to persuade the Maharaja of Kashmir to join Pakistan. In July 1947, ] is believed to have written to the Maharaja promising "every sort of favourable treatment," followed by lobbying of the State's Prime Minister by leaders of Jinnah's ] party. Faced with the Maharaja's indecision on accession, the Muslim League agents clandestinely worked in ] to encourage the ], exploiting an internal unrest regarding economic grievances. The authorities in ] waged a 'private war' by obstructing supplies of fuel and essential commodities to the State. Later in September, Muslim League officials in the ], including the Chief Minister ], assisted and possibly organized a large-scale invasion of Kashmir by ] tribesmen.<ref>{{citation |first=Ian |last=Copland |title=The Princely States, the Muslim League, and the Partition of India in 1947 |journal=The International History Review |volume=13 |number=1 |date=Feb 1991 |pp=38–69 |JSTOR=40106322 |doi=10.1080/07075332.1991.9640572}}</ref>{{rp|61}}{{sfn|Copland, State, Community and Neighbourhood in Princely India|2005|p=143}} Several sources indicate that the plans were finalised on 12 September by the Prime Minister ], based on proposals prepared by Colonel ] and Sardar ]. One plan called for organising an armed insurgency in the western districts of the state and the other for organising a ] tribal invasion. Both were set in motion.{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|pp=105–106}}{{sfn|Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited|2008|pp=120–121}} | |||

| ⚫ | The Jammu division of the state got caught up in the Partition violence. Large numbers of Hindus and Sikhs from ] and ] started arriving in March 1947, bringing "harrowing stories of Muslim atrocities." This provoked ], which had "many parallels with that in Sialkot." According to scholar Ilyas Chattha.{{sfn|Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath|2009|pp=179–180}} The violence in the eastern districts of Jammu that started in September, developed into a widespread ] around the October, organised by the Hindu Dogra troops of the State and perpetrated by the local Hindus, including members of the ], and the Hindus and Sikhs displaced from the neighbouring areas of West Pakistan. The Maharaja himself was implicated in some instances. A large number of Muslims were killed. Huge number of Muslims have fled to West Pakistan, some of whom made their way to the western districts of Poonch and Mirpur, which were ]. Many of these Muslims believed that the Maharaja ordered the killings in Jammu and instigated the Muslims in West Pakistan to join the ] and help in the formation of the Azad Kashmir government.{{sfn|Snedden, Kashmir The Unwritten History|2013|pp=48–57}} | ||

| The rebel forces in the western districts of Jammu got organised under the leadership of ], a ] leader. They took control of most of the western parts of the State by 22 October. On 24 October, they formed a provisional ] (free Kashmir) government based in ].{{sfn|Snedden, Kashmir The Unwritten History|2013|p=45}} | The rebel forces in the western districts of Jammu got organised under the leadership of ], a ] leader. They took control of most of the western parts of the State by 22 October. On 24 October, they formed a provisional ] (free Kashmir) government based in ].{{sfn|Snedden, Kashmir The Unwritten History|2013|p=45}} | ||

Revision as of 21:44, 17 February 2018

| Kashmir Conflict | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

India claims the entire erstwhile princely state of Jammu and Kashmir based on an instrument of accession signed in 1947. Pakistan claims Jammu and Kashmir based on its majority Muslim population, whereas China claims the Shaksam Valley and Aksai Chin. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Indo-Pakistani conflicts | |

|---|---|

| Kashmir conflict

Other conflicts Border skirmishes Strikes |

The Kashmir conflict is a territorial conflict primarily between India and Pakistan, having started just after the partition of India in 1947. China has at times played a minor role. India and Pakistan have fought three wars over Kashmir, including the Indo-Pakistani Wars of 1947 and 1965, as well as the Kargil War of 1999. The two countries have also been involved in several skirmishes over control of the Siachen Glacier.

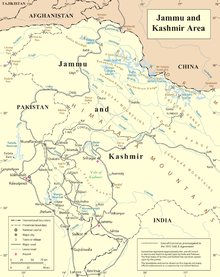

India claims the entire princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, and, as of 2010, administers approximately 43% of the region. It controls Jammu, the Kashmir Valley, Ladakh, and the Siachen Glacier. India's claims are contested by Pakistan, which administers approximately 37% of the region, namely Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. China currently administers the remaining 20% mostly uninhabited areas, the Shaksgam Valley, and the Aksai Chin region. China's claim over these territories has been disputed by India since China took Aksai Chin during the Sino-Indian War of 1962.

The present conflict is in Kashmir Valley. The root of conflict between the Kashmiri insurgents and the Indian government is tied to a dispute over local autonomy and based on the demand for self-determination. Democratic development was limited in Kashmir until the late 1970s, and by 1988, many of the democratic reforms introduced by the Indian Government had been reversed. Non-violent channels for expressing discontent were thereafter limited and caused a dramatic increase in support for insurgents advocating violent secession from India. In 1987, a disputed state election created a catalyst for the insurgency when it resulted in some of the state's legislative assembly members forming armed insurgent groups. In July 1988 a series of demonstrations, strikes and attacks on the Indian Government began the Kashmir Insurgency.

Although thousands of people have died as a result of the turmoil in Jammu and Kashmir, the conflict has become less deadly in recent years. Protest movements created to voice Kashmir's disputes and grievances with the Indian government, specifically the Indian Military, have been active in Jammu and Kashmir since 1989. Elections held in 2008 were generally regarded as fair by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and had a high voter turnout in spite of calls by separatist militants for a boycott. The election resulted in the creation of the pro-India Jammu and Kashmir National Conference, which then formed a government in the state. According to Voice of America, many analysts have interpreted the high voter turnout in this election as a sign that the people of Kashmir endorsed Indian rule in the state. But in 2010 unrest erupted after alleged fake encounter of local youth with security force. Thousands of youths pelted security forces with rocks, burned government offices and attacked railway stations and official vehicles in steadily intensifying violence. The Indian government blamed separatists and Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Pakistan-based militant group for stoking the 2010 protests.

Elections held in 2014 saw highest voters turnout in 26 years of history in Jammu and Kashmir. However, analysts explain that the high voter turnout in Kashmir is not an endorsement of Indian rule by the Kashmiri population, rather most people vote for daily issues such as food and electricity. An opinion poll conducted by the Chatham House international affairs think tank found that in the Kashmir valley – the mainly Muslim area in Indian Kashmir at the centre of the insurgency – support for independence varies between 74% to 95% in its various districts. Support for remaining with India was, however, extremely high in predominantly Hindu Jammu and Buddhist Ladakh.

According to scholars, Indian forces have committed many human rights abuses and acts of terror against Kashmiri civilian population including extrajudicial killing, rape, torture and enforced disappearances. Crimes by militants have also happened but are not comparable in scale with the crimes of Indian forces. According to Amnesty International, as of June 2015, no member of the Indian military deployed in Jammu and Kashmir has been tried for human rights violations in a civilian court, although there have been military court martials held. Amnesty International welcomed this move but cautioned that justice should be consistently delivered and prosecutions of security forces personnel be held in civilian courts. Amnesty International has also accused the Indian government of refusing to prosecute perpetrators of abuses in the region.

Kashmir's accession to India was provisional, and conditional on a plebiscite, and for this reason had a different constitutional status to other Indian states. In October 2015 Jammu and Kashmir High Court said that article 370 is "permanent" and Jammu and Kashmir did not merge with India the way other princely states merged but retained special status and limited sovereignty under Indian constitution.

In 2016 (8 July 2016 – present) unrest erupted after killing of a Hizbul Mujahideen militant Burhan Wani by Indian security forces.

India–Pakistan conflict

Further information: Timeline of the Kashmir conflictEarly history

See also: History of Kashmir and Jammu and Kashmir (princely state)According to the mid-12th century text Rajatarangini the Kashmir Valley was formerly a lake. Hindu mythology relates that the lake was drained by the sage Kashyapa, by cutting a gap in the hills at Baramulla (Varaha-mula), and invited Brahmans to settle there. This remains the local tradition and Kashyapa is connected with the draining of the lake in traditional histories. The chief town or collection of dwellings in the valley is called Kashyapa-pura, which has been identified as Template:Lang-grc Kaspapyros in Hecataeus (Apud Stephanus of Byzantium) and the Kaspatyros of Herodotus (3.102, 4.44). Kashmir is also believed to be the country indicated by Ptolemy's Kaspeiria.

The Pashtun Durrani Empire ruled Kashmir in the 18th century until its 1819 conquest by the Sikh ruler Ranjit Singh. The Raja of Jammu Gulab Singh, who was a vassal of the Sikh Empire and an influential noble in the Sikh court, sent expeditions to various border kingdoms and ended up encircling Kashmir by 1840. Following the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–1846), Kashmir was ceded under the Treaty of Lahore to the East India Company, which transferred it to Gulab Singh through the Treaty of Amritsar, in return for the payment of indemnity owed by the Sikh empire. Gulab Singh took the title of the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir. From then until the 1947 Partition of India, Kashmir was ruled by the Maharajas of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu. According to the 1941 census, the state's population was 77 percent Muslim, 20 percent Hindu and 3 percent others (Sikhs and Buddhists). Despite its Muslim majority, the princely rule was an overwhelmingly Hindu state. The Muslim majority suffered under Hindu rule with high taxes and discrimination.

Partition and invasion

British rule in the Indian subcontinent ended in 1947 with the creation of new states: the Dominion of Pakistan and the Union of India, as the successor states to British India. The British Paramountcy over the 562 Indian princely states ended. According to the Indian Independence Act 1947, "the suzerainty of His Majesty over the Indian States lapses, and with it, all treaties and agreements in force at the date of the passing of this Act between His Majesty and the rulers of Indian States". States were thereafter left to choose whether to join India or Pakistan or to remain independent. Jammu and Kashmir, the largest of the princely states, had a predominantly Muslim population ruled by the Hindu Maharaja Hari Singh. He decided to stay independent because he expected that the State's Muslims would be unhappy with accession to India, and the Hindus and Sikhs would become vulnerable if he joined Pakistan. On 11 August, the Maharaja dismissed his prime minister Ram Chandra Kak, who had advocated independence. Observers and scholars interpret this action as a tilt towards accession to India.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). While the Government of India accepted the accession, it added the proviso that it would be submitted to a "reference to the people" after the state is cleared of the invaders, since "only the people, not the Maharaja, could decide where Kashmiris wanted to live." It was a provisional accession.

National Conference, the largest political party in the State and headed by Sheikh Abdullah, endorsed the accession. In the words of the National Conference leader Syed Mir Qasim, India had the "legal" as well as "moral" justification to send in the army through the Maharaja's accession and the people's support of it.

The Indian troops, which were air lifted in the early hours of 27 October, secured the Srinagar airport. The city of Srinagar was being patrolled by the National Conference volunteers with Hindus and Sikhs moving about freely among Muslims, an "incredible sight" to visiting journalists. The National Conference also worked with the Indian Army to secure the city.

In the north of the state lay the Gilgit Agency, which had been leased by British India but returned to the Maharaja shortly before Independence. Gilgit's population did not favour the State's accession to India. Sensing their discontent, Major William Brown, the Maharaja's commander of the Gilgit Scouts, mutinied on 1 November 1947, overthrowing the Governor Ghansara Singh. The bloodless coup d'etat was planned by Brown to the last detail under the code name 'Datta Khel'. Local leaders in Gilgit formed a provisional government (Aburi Hakoomat), naming Raja Shah Rais Khan as the president and Mirza Hassan Khan as the commander-in-chief. But, Major Brown had already telegraphed Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan asking Pakistan to take over. According to historian Yaqoob Khan Bangash, the provisional government lacked sway over the population which had intense pro-Pakistan sentiments. Pakistan's Political Agent, Khan Mohammad Alam Khan, arrived on 16 November and took over the administration of Gilgit. According to various scholars, the people of Gilgit as well as those of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin, Punial, Hunza and Nagar joined Pakistan by choice.

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

Main article: Indo-Pakistani War of 1947Rebel forces from the western districts of the State and the Pakistani Pakhtoon tribesmen made rapid advances into the Baramulla sector. In the Kashmir valley, National Conference volunteers worked with the Indian Army to drive out the 'raiders'. The resulting First Kashmir War lasted until the end of 1948.

The Pakistan army made available arms, ammunition and supplies to the rebel forces who were dubbed the 'Azad Army'. Pakistani army officers 'conveniently' on leave and the former officers of the Indian National Army were recruited to command the forces. In May 1948, the Pakistani army officially entered the conflict, in theory to defend the Pakistan borders, but it made plans to push towards Jammu and cut the lines of communications of the Indian forces in the Mendhar valley. C. Christine Fair notes that this was the beginning of Pakistan using irregular forces and 'asymmetric warfare' to ensure plausible deniability, which has continued ever since.

On 1 November 1947, Mountbatten flew to Lahore for a conference with Jinnah, proposing that, in all the princely States where the ruler did not accede to a Dominion corresponding to the majority population (which would have included Junagadh, Hyderabad as well as Kashmir), the accession should be decided by an 'impartial reference to the will of the people'. Jinnah rejected the offer. According to Indian scholar A. G. Noorani Jinnah ended up squandering his leverage.

According to Jinnah, India acquired the accession through "fraud and violence." A plebiscite was unnecessary and states should accede according to their majority population. He was willing to urge Junagadh to accede to India in return for Kashmir. For a plebiscite, Jinnah demanded simultaneous troop withdrawal for he felt that 'the average Muslim would never have the courage to vote for Pakistan' in the presence of Indian troops and with Sheikh Abdullah in power. When Mountbatten countered that the plebiscite could be conducted by the United Nations, Jinnah, hoping that the invasion would succeed and Pakistan might lose a plebiscite, again rejected the proposal, stating that the Governors Generals should conduct it instead. Mountbatten noted that it was untenable given his constitutional position and India did not accept Jinnah's demand of removing Sheikh Abdullah.

Prime Ministers Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan met again in December, when Nehru informed Khan of India's intention to refer the dispute to the United Nations under article 35 of the UN Charter, which allows the member states to bring to the Security Council attention situations 'likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace'.

Nehru and other Indian leaders were afraid since 1947 that the "temporary" accession to India might act as an irritant to the bulk of the Muslims of Kashmir. Secretary in Patel’s Ministry of States, V.P. Menon, admitted in an interview in 1964 that India had been absolutely dishonest on the issue of plebiscite. A.G. Noorani blames many Indian and Pakistani leaders for the misery of Kashmiri people but says that Nehru was the main culprit.

UN mediation

India sought resolution of the issue at the UN Security Council, despite Sheikh Abdullah's opposition to it. Following the set-up of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP), the UN Security Council passed Resolution 47 on 21 April 1948. The measure called for an immediate cease-fire and called on the Government of Pakistan 'to secure the withdrawal from the state of Jammu and Kashmir of tribesmen and Pakistani nationals not normally resident therein who have entered the state for the purpose of fighting.' It also asked Government of India to reduce its forces to minimum strength, after which the circumstances for holding a plebiscite should be put into effect 'on the question of Accession of the state to India or Pakistan.' However, it was not until 1 January 1949 that the ceasefire could be put into effect, signed by General Douglas Gracey on behalf of Pakistan and General Roy Bucher on behalf of India. However, both India and Pakistan failed to arrive at a truce agreement due to differences over interpretation of the procedure for and the extent of demilitarisation. One sticking point was whether the Azad Kashmiri army was to be disbanded during the truce stage or at the plebiscite stage.

The UNCIP made three visits to the subcontinent between 1948 and 1949, trying to find a solution agreeable to both India and Pakistan. It reported to the Security Council in August 1948 that "the presence of troops of Pakistan" inside Kashmir represented a "material change" in the situation. A two-part process was proposed for the withdrawal of forces. In the first part, Pakistan was to withdraw its forces as well as other Pakistani nationals from the state. In the second part, "when the Commission shall have notified the Government of India" that Pakistani withdrawal has been completed, India was to withdraw the bulk of its forces. After both the withdrawals were completed, a plebiscite would be held. The resolution was accepted by India but effectively rejected by Pakistan.

The Indian government considered itself to be under legal possession of Jammu and Kashmir by virtue of the accession of the state. The assistance given by Pakistan to the rebel forces and the Pakhtoon tribes was held to be a hostile act and the further involvement of the Pakistan army was taken to be an invasion of Indian territory. From the Indian perspective, the plebiscite was meant to confirm the accession, which was in all respects already complete, and Pakistan could not aspire to an equal footing with India in the contest.

The Pakistan government held that the state of Jammu and Kashmir had executed a Standstill Agreement with Pakistan which precluded it from entering into agreements with other countries. It also held that the Maharaja had no authority left to execute accession because his people had revolted and he had to flee the capital. It believed that the Azad Kashmir movement as well as the tribal incursions were indigenous and spontaneous, and Pakistan's assistance to them was not open to criticism.

In short, India required an asymmetric treatment of the two countries in the withdrawal arrangements, regarding Pakistan as an 'aggressor', whereas Pakistan insisted on parity. The UN mediators tended towards parity, which was not to India's satisfaction. In the end, no withdrawal was ever carried out, India insisting that Pakistan had to withdraw first, and Pakistan contending that there was no guarantee that India would withdraw afterwards. No agreement could be reached between the two countries on the process of demilitarisation.

Cold War historian Robert J. McMahon states that American officials increasingly blamed India for rejecting various UNCIP truce proposals under various dubious legal technicalities just to avoid a plebiscite. McMahon adds that they were 'right' since a Muslim majority made a vote to join Pakistan the 'most likely outcome' and postponing the plebiscite would serve India's interests.

Scholars have commented that the failure of the Security Council efforts of mediation owed to the fact that the Council regarded the issue as a purely political dispute without investigating its legal underpinnings. Declassified British papers indicate that Britain and US had let their Cold War calculations influence their policy in the UN, disregarding the merits of the case.

Dixon Plan

The 1950s saw the mediation by Sir Owen Dixon, the UN-appointed mediator, who came the closest to solving the Kashmir dispute in the eyes of many commentators. Dixon arrived in the subcontinent in May 1950 and, after a visit to Kashmir, proposed a summit between India and Pakistan. The summit lasted five days, at the end of which Dixon declared a statewide plebiscite was impossible. Nehru then proposed a partition-cum-plebiscite plan: Jammu and Ladakh would go to India, Azad Kashmir and Northern Areas to Pakistan, and a plebiscite would be held in the Kashmir Valley. Dixon favoured the plan, which bears his name till this day. Dixon agreed that people in Jammu and Ladakh were clearly in favour of India; equally clearly, those in Azad Kashmir and the Northern Areas wanted to be part of Pakistan. This left the Kashmir Valley and 'perhaps some adjacent country' around Muzaffarabad in uncertain political terrain. However, according to Dixon, Pakistan "bluntly rejected" the proposal. It believed that the plebiscite should be held in the entire state or the state should be partitioned along religious lines.

Dixon also had concerns that the Kashmiris, not being high-spirited people, may vote under fear or improper influences. Following Pakistan's objections, he proposed that Sheikh Abdullah administration should be held in "commission" (in abeyance) while the plebiscite was held. This was not acceptable to India. At that point, Dixon lost patience and declared failure. Dixon's premature withdrawal has been criticised, but perhaps Dixon had not realised how close he had come to solving the dispute.

1950 military standoff

In July 1950, Sheikh Abdullah sought to introduce far-reaching land reforms, but the Prince Regent Karan Singh insisted that they had to be carried out by a Legislative Assembly. Abdullah then proposed electing a Constituent Assembly, which was approved in April 1951. Abdullah wanted the Constituent Assembly to decide the State's accession. But this was not agreed to by the Prime Minister of India, as it would represent "underhand dealing" while the matter was being decided by the UN. Around this time, the Korean War broke out and the West grew anxious about defending the Middle East from possible communist attacks. They sought Pakistani help but were aware that Pakistan desired guarantees of security against an Indian attack. The international scene was in a flux.

Towards the end of 1950, sections of Pakistani leaders grew impatient about the lack of progress in the UN, and raised a hue and cry. The Prime Minister of North-West Frontier Province promised a jihad by the Pashtun population of Pakistan. The governor of Punjab declared that the "whole of Asia would be engulfed in a war". The calls for a holy war reverberated through the Pakistani society. India grew anxious and raised the issue with the western powers. Receiving no response, following a rash of violent incidents in Kashmir Valley in June 1951 and reports of Pakistani troop movements, India decided to move its troops to the border. According to Nehru, "our lack of proper defenses on our frontiers would itself be an invitation to attack." A military stand-off ensued, lasting from mid-July 1951 till the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan in October 1951. India resisted pressures from western powers for standing down, claiming that the troop deployment was a necessary deterrent. Meanwhile, the elections to the Constituent Assembly passed off peacefully, the Assembly convening on 31 October.

The Commonwealth had taken up the Kashmir issue in January 1951. Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies suggested that a Commonwealth force be stationed in Kashmir; that a joint Indo-Pakistani force be stationed in Kashmir and the plebiscite administrator be entitled to raise local troops while the plebiscite would be held. Pakistan accepted these proposals but India rejected them because it did not want Pakistan, who was in India's eyes the 'aggressor', to have an equal footing. The UN Security Council called on India and Pakistan to honour the resolutions of plebiscite both had accepted in 1948 and 1949. The United States and Britain proposed that if the two could not reach an agreement then arbitration would be considered. Pakistan agreed but Nehru said he would not allow a third person to decide the fate of four million people. Korbel criticised India's stance towards a ″valid″ and ″recommended technique of international co-operation.″

However, the peace was short-lived. Later by 1953, Sheikh Abdullah, who was by then in favour of resolving Kashmir by a plebiscite, an idea which was "anametha" to the Indian government according to scholar Zutshi, fell out with the Indian government. He was dismissed and imprisoned in August 1953. His former deputy, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad was appointed as the prime minister, and Indian security forces were deployed in the Valley to control the streets.

Nehru's plebiscite offer

With India's "abridged authority" in Kashmir, Nehru decided that a settlement must be found since India could not hold Kashmir "at the point of a bayonet". He asserted several of times since 1947 that only Kashmiris have the right to decide their own future. Nehru and the Pakistani Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Bogra discussed Kashmir informally during June 1953. The two then discussed in later talks in Delhi over the naming of a plebiscite administrator. Starting in July 1953, Nehru made a renewed push on the plebiscite option in discussions with Pakistan. In August he proposed that a plebiscite administrator be appointed within six months. Other than demanding that the plebiscite administrator not be from one of the major powers, he placed no other conditions. Reversing his earlier policies, he suggested that the plebiscite could be held in all regions of the state and the state would be partitioned on the basis of the results. He was open to a "different approach" to the scaling back of troops in the State so as to allow a free vote. According to Schofield, Pakistan's reluctance to consider an arbitrator other than Admiral Nimitz, and India's lack of approval of Nimitz, led to a stall in proceedings.

In fact, Pakistan was now moving in a different direction. Using the opening created by the Korean War, Pakistan was aggressively pursuing American military aid. Two days after Liaquat Ali Khan's assassination, Pakistani military delegation was in Washington to get as much military equipment as it could. The delegation expressed Pakistan's readiness to participate in defending the Middle East even if the US were to pay no attention to Pakistan's security against India. Pakistan regarded India's behaviour during the military stand-off as "aggressive", as one that needed a military response. As the US-Pakistan Mutual Defence Pact was taking shape in September 1953, Nehru warned Pakistan that it has to choose between winning Kashmir through a plebiscite or pursuing a military alliance with the US. If such a pact were to be concluded, Nehru said, the situation would change dramatically and "all problems would be seen in a new light". Consequently, when the pact was concluded in May 1954, Nehru withdrew the plebiscite offer and declared that the status quo was the only remaining option.

Nehru's withdrawal from the plebiscite option came a major blow to all concerned. Scholars have suggested that India was never seriously intent on holding a plebiscite, and the withdrawal came to signify a vindication of their belief. Scholar Mahesh Shankar argues that the reason for the withdrawal was Nehru's disillusionment with the aggressive attitude and militaristic posture of Pakistan which would be apparently strengthened by the 1954 US-Pakistan Pact. These factors made the strategic and reputational costs of continued concessions to Pakistan unacceptable to India.

Sino-Indian War

Main article: Sino-Indian WarIn 1962, troops from the People's Republic of China and India clashed in territory claimed by both. China won a swift victory in the war, resulting in Chinese annexation of the region they call Aksai Chin and which has continued since then. Another smaller area, the Trans-Karakoram, was demarcated as the Line of Control (LOC) between China and Pakistan, although some of the territory on the Chinese side is claimed by India to be part of Kashmir. The line that separates India from China in this region is known as the "Line of Actual Control".

Operation Gibraltar and 1965 Indo-Pakistani war

Main articles: Operation Gibraltar, Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, and Tashkent AgreementFollowing its failure to seize Kashmir in 1947, Pakistan supported numerous 'covert cells' in Kashmir using operatives based in its New Delhi embassy. After its military pact with the United States in the 1950s, it intensively studied guerrilla warfare through engagement with the US military. In 1965, it decided that the conditions were ripe for a successful guerilla war in Kashmir. Code named 'Operation Gibraltar', companies were dispatched into Indian-administered Kashmir, the majority of whose members were razakars (volunteers) and mujahideen recruited from Pakitan-administered Kashmir and trained by the Army. These irregular forces were supported by officers and men from the paramilitary Northern Light Infantry and Azad Kashmir Rifles as well as commandos from the Special Services Group. About 30,000 infiltrators are estimated to have been dispatched in August 1965 as part of the 'Operation Gibraltar'.

The plan was for the infiltrators to mingle with the local populace and incite them to rebellion. Meanwhile, guerilla warfare would commence, destroying bridges, tunnels and highways, as well as Indian Army installations and airfields, creating conditions for an 'armed insurrection' in Kashmir. If the attempt failed, Pakistan hoped to have raised international attention to the Kashmir issue. Using the newly acquired sophisticated weapons through the American arms aid, Pakistan believed that it could achieve tactical victories in a quick limited war.

However, the 'Operation Gibraltar' ended in failure as the Kashmiris did not revolt. Instead, they turned in infiltrators to the Indian authorities in substantial numbers, and the Indian Army ended up fighting the Pakistani Army regulars. Pakistan claimed that the captured men were Kashmiri 'freedom fighters', a claim contradicted by the international media. On 1 September, Pakistan launched an attack across the Cease Fire Line, targeting Akhnoor in an effort to cut Indian communications into Kashmir. In response, India broadened the war by launching an attack on Pakistani Punjab across the international border. The war lasted till 23 September, ending in a stalemate. Following the Tashkent Agreement, both the sides withdrew to their pre-conflict positions, and agreed not to interfere in each other's internal affairs.

1971 Indo-Pakistani war and Simla Agreement

Main articles: Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 and Simla AgreementThe Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 led to a loss for Pakistan and a military surrender in East Pakistan. Bangladesh got created as a separate state with India's support and India emerged as a clear regional power in South Asia.

A bilateral summit was held at Simla as a follow-up to the war, where India pushed for peace in South Asia. At stake were 5,139 square miles of Pakistan's territory captured by India during the conflict, and over 90,000 prisoners of war held in Bangladesh. India was ready to return them in exchange for a "durable solution" to the Kashmir issue. Diplomat J. N. Dixit states that the negotiations at Simla were painful and tortuous, and almost broke down. The deadlock was broken in a personal meeting between the Prime Ministers Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Indira Gandhi, where Bhutto acknowledged that the Kashmir issue should be finally resolved and removed as a hurdle in India-Pakistan relations; that the cease-fire line, to be renamed the Line of Control, could be gradually converted into a de jure border between India and Pakistan; and that he would take steps to integrate the Pakistani-controlled portions of Jammu and Kashmir into the federal territories of Pakistan. However, he requested that the formal declaration of the Agreement should not include a final settlement of the Kashmir dispute as it would endanger his fledgling civilian government and bring in military and other hardline elements into power in Pakistan.

Accordingly, the Simla Agreement was formulated and signed by the two countries, whereby the countries resolved to settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations and to maintain the sanctity of the Line of Control. Multilateral negotiations were not ruled out, but they were conditional upon both sides agreeing to them. To India, this meant an end to the UN or other multilateral negotiations. However Pakistan reinterpreted the wording in the light of a reference to the "UN charter" in the agreement, and maintained that it could still approach the UN. The United States, United Kingdom and most Western governments agree with India's interpretation.

The Simla Agreement also stated that the two sides would meet again for establishing durable peace. Reportedly Bhutto asked for time to prepare the people of Pakistan and the National Assembly for a final settlement. Indian commentators state that he reneged on the promise. Bhutto told the National Assembly on 14 July that he forged an equal agreement from an unequal beginning and that he did not compromise on the right of self-determination for Jammu and Kashmir. The envisioned meeting never occurred.

Internal conflict

Political movements during the Dogra rule

Main article: Political movements in Kashmir during the Dogra rulePolitical movements in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir started in 1932, earlier than in any other princely state of India. In that year, Sheikh Abdullah, a Kashmiri, and Chaudhry Ghulam Abbas, a Jammuite, led the founding of the All-Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference in order to agitate for the rights of Muslims in the state. In 1938, they renamed the party National Conference in order to make it representative of all Kashmiris independent of religion. The move brought Abdullah closer to Jawaharlal Nehru, the rising leader of the Congress party. The National Conference eventually became a leading member of the All-India States Peoples' Conference, a Congress-sponsored confederation of the political movements in the princely states.

Three years later, rifts developed within the Conference owing to political, regional and ideological differences. A faction of the party's leadership grew disenchanted with Abdullah's leanings towards Nehru and the Congress, and his secularisation of Kashmiri politics. Consequently, Abbas broke away from the National Conference and revived the old Muslim Conference in 1941, in collaboration with Mirwaiz Yusuf Shah. These developments indicated fissures between the ethnic Kashmiris and Jammuites, as well as between the Hindus and Muslims of Jammu. Muslims in the Jammu region were Punjabi-speaking and felt closer affinity to Punjabi Muslims than with the Valley Kashmiris. In due course, the Muslim Conference started aligning itself ideologically with the All-India Muslim League, and supported its call for an independent 'Pakistan'. The Muslim Conference derived popular support among the Muslims of the Jammu region, and some from the Valley. Conversely, Abdullah's National Conference enjoyed influence in the Valley. Chitralekha Zutshi states that the political loyalties of Valley Kashmiris were divided in 1947, but the Muslim Conference failed to capitalise on it due its fractiousness and the lack of a distinct political programme.

In 1946, the National Conference launched the 'Quit Kashmir' movement, asking the Maharaja to hand the power over to the people. The movement came under criticism from the Muslim Conference, who charged that Abdullah was doing it to boost his own popularity, waning because of his pro-India stance. Instead, the Muslim Conference launched a 'campaign of action' similar to Muslim League's programme in British India. Both Abdullah and Abbas were imprisoned. By 22 July 1947, the Muslim Conference started calling for the state's accession to Pakistan.

The Dogra Hindus of Jammu were originally organised under the banner of All Jammu and Kashmir Rajya Hindu Sabha, with Prem Nath Dogra as a leading member. In 1942, Balraj Madhok arrived in the state as a pracharak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). He established branches of the RSS in Jammu and later in the Kashmir Valley. Prem Nath Dogra was also the chairman (sanghchalak) of the RSS in Jammu. In May 1947, following the Partition plan, the Hindu Sabha threw in its support to whatever the Maharaja might decide regarding the state's status, which in effect meant support for the state's independence. However, following the communal upheaval of the Partition and the tribal invasion, its position changed to supporting the accession of the state to India and, subsequently, full integration of Jammu with India. In November 1947, shortly after the state's accession to India, the Hindu leaders launched the Jammu Praja Parishad with the objective of achieving the "full integration" of Jammu and Kashmir with India, opposing the "communist-dominated anti-Dogra government of Sheikh Abdullah."

Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir

Autonomy and plebiscite conundrum (1947–1953)

Article 370 was drafted in the Indian constitution granting special autonomous status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir, as per Instrument of Accession. This article specifies that the State must concur in the application of laws by Indian parliament, except those that pertain to Communications, Defence and Foreign Affairs. Central Government could not exercise its power to interfere in any other areas of governance of the state.

Sheikh Abdullah took oath as Prime Minister of the state on 17 March 1948. In 1949, the Indian government obliged Hari Singh to leave Jammu and Kashmir and yield the government to Sheikh Abdullah. Karan Singh, the son of the erstwhile Maharajah Hari Singh was made the Sadr-i-Riyasat (Constitutional Head of State) and the Governor of the state.

Elections were held for the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir in 1951, with 75 seats allocated for the Indian administered part of Kashmir, and 25 seats left reserved for the Pakistan administered part. Sheikh Abdullah's National Conference won all 75 seats in a rigged election. In October 1951, Jammu & Kashmir National Conference under the leadership of Sheikh Abdullah formed the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir to formulate the Constitution of the state. Sheikh initially wanted the Constituent Assembly to decide the State's accession. But this was not agreed to by Nehru, who stated that such "underhand dealing" would be very bad, as the matter was being decided by the UN.

Sheikh Abdullah was said to have ruled the state in an undemocratic and authoritarian manner during this period.

According to historian Zutshi, in the late 1940s, most Kashmiri Muslims in Indian Kashmir were still debating the value of the state's association with India or Pakistan. By the 1950s, she says, the National Conference government's repressive measures and the Indian state's seeming determination to settle the state's accession to India without a reference to the people of the state brought Kashmiri Muslims to extol the virtues of Pakistan and condemn India's high-handedness in its occupation of the territory, and even those who had been in India's favour began to speak in terms of the state's association with Pakistan.

In early 1949, an agitation was started by Jammu Praja Parishad, a Hindu nationalist party which was active in the Jammu region, over the ruling National Conference's policies. The government swiftly suppressed it by arresting as many as 294 members of the Praja Parishad including Prem Nath Dogra, its president. Though Sheikh's land reforms were said to have benefited the people of rural areas, Praja Parishad opposed the 'Landed Estates Abolition Act', saying it was against the Indian Constitutional rights, for implementing land acquisition without compensation. Praja Parishad also called for the full integration with the rest of India, directly clashing with the demands of National Conference for complete autonomy of the state. On 15 January 1952, students staged a demonstration against the hoisting of the state flag alongside the Indian Union flag. They were penalised, giving rise to a big procession on 8 February. The military was called out and a 72-hour curfew imposed. N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar, the Indian Central Cabinet minister in charge of Kashmir affairs, came down to broker peace, which was resented by Sheikh Abdullah.

In order to break the constitutional deadlock, Nehru invited the National Conference to send a delegation to Delhi. The '1952 Delhi Agreement' was formulated to settle the extent of applicability of the Indian Constitution to the Jammu and Kashmir and the relation between the State and Centre. It was reached between Nehru and Abdullah on 24 July 1952. Following this, the Constituent Assembly abolished the monarchy in Kashmir, and adopted an elected Head of State (Sadr-i Riyasat). However, the Assembly was reluctant to implement the remaining measures agreed to in the Delhi Agreement.

In 1952, Sheikh Abdullah drifted from his previous position of endorsing accession to India to insisting on the self-determination of Kashmiris.

The Praja Parishad undertook a civil disobedience campaign for a third time in November 1952, which again led to repression by the state government. The Parishad accused Abdullah of communalism (sectarianism), favouring the Muslim interests in the state and sacrificing the interests of the others. The Jana Sangh joined hands with the Hindu Mahasabha and Ram Rajya Parishad to launch a parallel agitation in Delhi. In May 1953, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, a prominent Indian leader of the time and the founder of Hindu nationalist party Bharatiya Jana Sangh (later evolved as BJP), made a bid to enter Jammu and Kashmir after denying to take a permit, citing his rights as an Indian citizen to visit any part of the country. Abdullah prohibited his entry and promptly arrested him when he attempted. An estimated 10,000 activists were imprisoned in Jammu, Punjab and Delhi, including Members of Parliament. Unfortunately, Mukherjee died in detention on 23 June 1953, leading to an uproar in whole India and precipitating a crisis that went out of control.

Observers state that Abdullah became upset, as he felt, his "absolute power" was being compromised in India.

Meanwhile, Nehru's pledge of a referendum to people of Kashmir did not come into action. Sheikh Abdullah advocated complete independence and had allegedly joined hands with US to conspire against India.

On 8 August 1953, Sheikh Abdullah was dismissed as Prime Minister by the Sadr-i-Riyasat Karan Singh on the charge that he had lost the confidence of his cabinet. He was denied the opportunity to prove his majority on the floor of the house. He was also jailed in 1953 while Sheikh's dissident deputy, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad was appointed as the new Prime Minister of the state.

Period of integration and rise of Kashmiri nationalism (1954–1974)

From all the information I have, 95 per cent of Kashmir Muslims do not wish to be or remain Indian citizens. I doubt therefore the wisdom of trying to keep people by force where they do not wish to stay. This cannot but have serious long-term political consequences, though immediately it may suit policy and please public opinion.

— Jayaprakash Narayan’s letter to Nehru, May 1, 1956.

Bakshi Mohammad implemented all the measures of the '1952 Delhi Agreement'. In May 1954, as a subsequent to the Delhi agreement, The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954, is issued by the President of India under Article 370, with the concurrence of the Government of the State of Jammu and Kashmir. In that order, the Article 35A is added to the Constitution of India to empower the Jammu and Kashmir state's legislature to define “permanent residents” of the state and provide special rights and privileges to those permanent residents.

On 15 February 1954, under the leadership of Bakshi Mohammad, the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir ratified the state's accession to India. On 17 November 1956, the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir was adopted by the Assembly and it came into full effect on 26 January 1957. On 24 January 1957, the UN passed a resolution stating that the decisions of the Constituent Assembly would not constitute a final disposition of the State, which needs to be carried out by a free and impartial plebiscite.

After the overthrow of Sheikh Abdullah, his lieutenant Mirza Afzal Beg formed the Plebiscite Front on 9 August 1955 to fight for the plebiscite demand and the unconditional release of Sheikh Abdullah. The activities of the Plebiscite Front eventually led to the institution of the infamous Kashmir Conspiracy Case in 1958 and two other cases. On 8 August 1958, Abdullah was arrested on the charges of these cases.

India's Home Minister, Pandit Govind Ballabh Pant, during his visit to Srinagar in 1956, declared that the State of Jammu and Kashmir was an integral part of India and there could be no question of a plebiscite to determine its status afresh, hinting that India would resist plebiscite efforts from then on.

After the mass unrest due to missing of holy relic from the Hazratbal Shrine on 27 December 1963, the State Government dropped all charges in the Kashmir Conspiracy Case as a diplomatic decision, on 8 April 1964. Sheikh Abdullah was released and returned to Srinagar where he was accorded a great welcome by the people of the valley. After his release he was reconciled with Nehru. Nehru requested Sheikh Abdullah to act as a bridge between India and Pakistan and make President Ayub to agree to come to New Delhi for the talks for a final solution of the Kashmir problem. President Ayub Khan also sent telegrams to Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah with the message that as Pakistan too was a party to the Kashmir dispute any resolution of the conflict without its participation would not be acceptable to Pakistan. Sheikh Abdullah went to Pakistan in the spring of 1964. President Ayub Khan of Pakistan held extensive talks with him to explore various avenues for solving the Kashmir problem and agreed to come to Delhi in mid June for talks with Nehru as suggested by him. Even the date of his proposed visit was fixed and communicated to New Delhi. However, while Abdullah was still in Pakistan, news came of the sudden death of Nehru on 27 May 1964. The peace initiative died with Nehru.

After Nehru's death in 1964, Abdullah was interned from 1965 to 1968 and exiled from Kashmir in 1971 for 18 months. The Plebiscite Front was also banned. This was allegedly done to prevent him and the Plebiscite Front which was supported by him, from taking part in elections in Kashmir.

On 21 November 1964, the Articles 356 and 357 of the Indian Constitution were extended to the state, by virtue of which the Central Government can assume the government of the State and exercise its legislative powers. On 24 November 1964, the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly passed a constitutional amendment changing the elected post of Sadr-i-Riyasat to a centrally-nominated post of "Governor" and renaming "Prime Minister" to "Chief Minister", which is regarded as the "end of the road" for the Article 370, and the Constitutional autonomy guaranteed by it. On 3 January 1965, prior to 1967 Assembly elections, the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference dissolved itself and merged into the Indian National Congress, as a marked centralising strategy.

After Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, Kashmiri nationalists Amanullah Khan and Maqbool Bhat, along with Hashim Qureshi, in 1966, formed another Plebiscite Front in Azad Kashmir with an armed wing called the National Liberation Front (NLF), with the objective of freeing Kashmir from Indian occupation and then liberating the whole of Jammu and Kashmir. Later in 1976, Maqbool Bhat is arrested on his return to the Valley. Amanullah Khan moved to England and there NLF was renamed Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF).

Shortly after 1965 war, Kashmiri Pandit activist and writer, Prem Nath Bazaz wrote that the overwhelming majority of Kashmir's Muslims were unfriendly to India and wanted to get rid of the political setup, but did not want to use violence for this purpose. He added : "It would take another quarter century of repression and generation turnover for the pacifist approach to yield decisively as armed struggle, qualifying Kashmiris as 'reluctant secessionists'."

In 1966 the Indian opposition leader Jayaprakash wrote to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi that India rules Kashmir by force.

Revival of National Conference (1975–1983)

In 1971, the declaration of Bangladesh's independence was proclaimed on 26 March by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and subsequently the Bangladesh Liberation War broke out in erstwhile East Pakistan between Pakistan and Bangladesh which was later joined by India, and subsequently war broke out on the western border of India between India and Pakistan, both of which culminated in the creation of Bangladesh.

It is said that, Sheikh Abdullah, watching the alarming turn of events in the subcontinent, realized that for the survival of the region, there was an urgent need to stop pursuing confrontational politics and promoting solution of issues by a process of reconciliation and dialogue. Critics of Sheikh hold the view that he gave up the cherished goal of plebiscite for gaining Chief Minister's chair. He started talks with the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi for normalizing the situation in the region and came to an accord with her, called 1975 Indira-Sheikh accord, by giving up the demand for a plebiscite in lieu of the people being given the right to self-rule by a democratically elected Government (as envisaged under article 370 of the Constitution of India), rather than the "puppet government" which is said to have ruled the state till then. Sheikh Abdullah revived the National Conference, and Mirza Afzal Beg's Plebiscite Front was dissolved in the NC. Sheikh assumed the position of Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir again after 11 years. Later in 1977, the Central Government and the ruling Congress Party withdrew its support so that the State Assembly had to be dissolved and mid term elections called. Sheikh's party National Conference won a majority (47 out of 74 seats) in the subsequent elections, on the pledge to restore Jammu and Kashmir's autonomy, and Sheikh Abdullah was re-elected as Chief Minister. The 1977 Assembly election is regarded as the first "free and fair" election in the Jammu and Kashmir state.

He remained as Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir till his death in 1982. Later his eldest son Farooq Abdullah succeeded him as the Chief Minister of the state.

During the 1983 Assembly elections, Indira Gandhi campaigned aggressively, raising the bogey of a 'Muslim invasion' in the Jammu region because of the Resettlement Bill, passed by the then NC government, which gave Kashmiris who left for Pakistan between 1947 and 1954 the right to return, reclaim their properties and resettle. On the other hand, Farooq Abdullah allied with the Mirwaiz Maulvi Mohammed Farooq for the elections and charged that the state's autonomy had been eroded by successive Congress Party governments. The strategies yielded dividends and the Congress won 26 seats, while the NC secured 46. Barring an odd constituency, all victories of the Congress were in the Jammu and Ladakh regions, while NC swept the Kashmir Valley. This election is said to have cemented the political polarization on religious lines in the Jammu and Kashmir state.

After the results of the 1983 election, the Hindu nationalists in the state were demanding stricter central government control over the state whereas Kashmir's Muslims wanted to preserve the state's autonomy. Islamic fundamentalist groups clamoured for a plebiscite. Maulvi Farooq challenged the contention that there was no longer a dispute on Kashmir. He said that the people's movement for plebiscite would not die even though India thought it did when Sheikh Abdullah died.

In 1983, learned men of Kashmiri politics testified that Kashmiris had always wanted to be independent. But the more serious-minded among them also realised that this is not possible, considering Kashmir's size and borders.

According to professor Mridu Rai, for three decades Delhi's handpicked politicians in Kashmir had supported the State's accession to India in return for generous disbursements from Delhi. Rai states that the state elections were conducted in Jammu and Kashmir, but except for the 1977 and 1983 elections no state election was fair.

Kashmiri Pandit activist Prem Nath Bazaz wrote that if free elections were held, the majority of seats would be won by those not friendly to India.

Rise of the separatist movement and Islamism (1984–1986)

Increasing anti-Indian protests took place in Kashmir in the 1980s. The Soviet-Afghan jihad and the Islamic Revolution in Iran were becoming sources of inspiration for large numbers of Kashmiri Muslim youth. The state authorities responded with increasing use of brute force to simple economic demands. Both the pro-Independence Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) and the pro-Pakistan Islamist groups including JIJK mobilised the fast growing anti-Indian sentiments among the Kashmiri population. 1984 saw a pronounced rise in terrorist violence in Kashmir. When Kashmir Liberation Front militant Maqbool Bhat was executed in February 1984, strikes and protests by Kashmiri nationalists broke out in the region. Large numbers of Kashmiri youth participated in widespread anti India demonstrations, which faced heavy handed reprisals by Indian state forces. Critics of the then Chief Minister, Farooq Abdullah, charged that Abdullah was losing control. His visit to Pakistan administered Kashmir became an embarrassment, where according to Hashim Qureshi, he shared a platform with Kashmir Liberation Front. Though Abdullah asserted that he went on behalf on Indira Gandhi and his father, so that sentiments there could "be known first hand", few people believed him. There were also allegations that he had allowed Khalistan terrorist groups to train in Jammu province, although those allegations were never proved. On July 2, 1984, Ghulam Mohammad Shah, who had support from Indira Gandhi, replaced his brother-in-law Farooq Abdullah and became the chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, after Abdullah was dismissed, in what was termed as a political "coup".

In 1986 some members of the JKLF crossed over to Pakistan to receive arms training but the Jamaat Islami Jammu Kashmir, which saw Kashmiri nationalism as contradicting Islamic universalism and its own desire for merging with Pakistan, did not support the JKLF movement. As late as that year, Jamaat member Syed Ali Shah Geelani, who later became a supporter of Kashmir’s armed revolt, urged that the solution for the Kashmir issue be arrived at through peaceful and democratic means. To achieve its goal of self-determination for the people of Jammu and Kashmir the Jamaat e Islami's stated position was that the Kashmir issues be resolved through constitutional means and dialogue.

Shah's administration, which did not have the people's mandate, turned to Islamists and opponents of India, notably the Molvi Iftikhar Hussain Ansari, Mohammad Shafi Qureshi and Mohinuddin Salati, to gain some legitimacy through religious sentiments. This gave political space to Islamists who previously lost overwhelmingly, allegedly due to massive rigging, in the 1983 state elections. In 1986, Shah decided to construct a mosque within the premises of an ancient Hindu temple inside the New Civil Secretariat area in Jammu to be made available to the Muslim employees for 'Namaz'. People of Jammu took to streets to protest against this decision, which led to a Hindu-Muslim clash. On his return to Kashmir valley in February 1986, Gul Shah retaliated and incited the Kashmiri Muslims by saying Islam khatrey mein hey (trans. Islam is in danger). As a result, communal violence gripped the region, in which Hindus were targeted, especially the Kashmiri pandits, who later in the year 1990, fled the valley in large numbers. During the Anantnag riot in February 1986, although no Hindu was killed, many houses and other properties belonging to Hindus were looted, burnt or damaged.

An investigation of Anantnag riots revealed that members of the 'secular parties' in the state, rather than the Islamists, had played a key role in organising the violence to gain political mileage through religious sentiments. Shah called in the army to curb the violence, but it had little effect. His government was dismissed on March 12, 1986, by the then Governor Jagmohan following communal riots in south Kashmir. This led Jagmohan to rule the state directly.

Jagmohan is said to have failed to distinguish between the secular forms and Islamist expressions of Kashmiri identity, and hence saw that identity as a threat. This failure was exploited by the Islamists of the valley, who defied the 'Hindu nationalist' policies implemented during Jagmohan's tenure, and thereby gained momentum. The political fight was hence being portrayed as a conflict between "Hindu" New Delhi (Central Government), and its efforts to impose its will in the state, and "Muslim" Kashmir, represented by political Islamists and clerics. Jagmohan's pro-Hindu bias in the administration led to an increase in the appeal of the Muslim United Front.

Post-1987 insurgency in Indian administered Kashmir

1987 state elections

Main article: Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly election, 1987An alliance of Islamic parties organized into Muslim United Front (MUF) to contest the 1987 state elections. Culturally, the growing emphasis on secularism led to a backlash with Islamic parties becoming more popular. MUF's election manifesto stressed the need to solve all outstanding issues according to the Simla agreement, work for Islamic unity and against political interference from the centre. Their slogan was wanting the law of the Quran in the Assembly.

There was highest recorded participation in this election. Eighty per cent of the people in the Valley voted. MUF received victory in only 4 of the contested 43 electoral constituencies despite its high vote share of 31 per cent (this means that its official vote in the Valley was larger than one-third). The elections were widespreadly believed to have been rigged by the ruling party National Conference, allied with the Indian National Congress. In the absence of rigging, commentators believe that the MUF could have won fifteen to twenty seats, a contention admitted by the National Conference leader Farooq Abdullah. Scholar Sumantra Bose, on the other hand. opines that the MUF would have won most of the constituencies in the Kashmir Valley.

BBC reported that Khem Lata Wukhloo, who was a leader of the Congress party at the time, admitted the widespread rigging in Kashmir. He stated:

"I remember that there was a massive rigging in 1987 elections. The losing candidates were declared winners. It shook the ordinary people's faith in the elections and the democratic process."

1989 popular insurgency and militancy

Main article: Insurgency in Jammu and KashmirIn the years since 1990, the Kashmiri Muslims and the Indian government have conspired to abolish the complexities of Kashmiri civilization. The world it inhabited has vanished: the state government and the political class, the rule of law, almost all the Hindu inhabitants of the valley, alcohol, cinemas, cricket matches, picnics by moonlight in the saffron fields, schools, universities, an independent press, tourists and banks. In this reduction of civilian reality, the sights of Kashmir are redefined: not the lakes and Mogul gardens, or the storied triumphs of Kashmiri agriculture, handicrafts and cookery, but two entities that confront each other without intermediary: the mosque and the army camp.

— British journalist James Buchan

In 1989, a widespread popular and armed insurgency started in Kashmir. After the 1987 state legislative assembly election, some of the results were disputed. This resulted in the formation of militant wings and marked the beginning of the Mujahadeen insurgency, which continues to this day. India contends that the insurgency was largely started by Afghan mujahadeen who entered the Kashmir valley following the end of the Soviet-Afghan War. Yasin Malik, a leader of one faction of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front, was one of the Kashmiris to organise militancy in Kashmir, along with Ashfaq Majeed Wani, Javaid Ahmad Mir, and Abdul Hamid Sheikh. Since 1995, Malik has renounced the use of violence and calls for strictly peaceful methods to resolve the dispute. Malik developed differences with one of the senior leaders, Farooq Siddiqui (alias Farooq Papa), for shunning demands for an independent Kashmir and trying to cut a deal with the Indian Prime Minister. This resulted in a split in which Bitta Karate, Salim Nanhaji, and other senior comrades joined Farooq Papa. Pakistan claims these insurgents are Jammu and Kashmir citizens, and are rising up against the Indian army as part of an independence movement. Amnesty International has accused security forces in Indian-controlled Kashmir of exploiting an Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act that enables them to "hold prisoners without trial". The group argues that the law, which allows security forces to detain individuals for up to two years without presenting charges violates prisoners' human rights. In 2011, the state humans right commission said it had evidence that 2,156 bodies had been buried in 40 graves over the last 20 years. The authorities deny such accusations. The security forces say the unidentified dead are militants who may have originally come from outside India. They also say that many of the missing people have crossed into Pakistan-administered Kashmir to engage in militancy. However, according to the state human rights commission, among the identified bodies 574 were those of "disappeared locals", and according to Amnesty International's annual human rights report (2012) it was sufficient for "belying the security forces' claim that they were militants".

India claims these insurgents are Islamic terrorist groups from Pakistan-administered Kashmir and Afghanistan, fighting to make Jammu and Kashmir a part of Pakistan. They claim Pakistan supplies munitions to the terrorists and trains them in Pakistan. India states that the terrorists have killed many citizens in Kashmir and committed human rights violations whilst denying that their own armed forces are responsible for human rights abuses. On a visit to Pakistan in 2006, former Chief Minister of Kashmir Omar Abdullah remarked that foreign militants were engaged in reckless killings and mayhem in the name of religion. The Indian government has said militancy is now on the decline.

The Pakistani government calls these insurgents "Kashmiri freedom fighters", and claims that it provides them only moral and diplomatic support, although India believes they are Pakistan-supported terrorists from Pakistan Administered Kashmir. In October 2008, President Asif Ali Zardari of Pakistan called the Kashmir separatists "terrorists" in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. These comments sparked outrage amongst many Kashmiris, some of whom defied a curfew imposed by the Indian army to burn him in effigy.

In 2008, pro-separatist leader Mirwaiz Umar Farooq told the Washington Post that there has been a "purely indigenous, purely Kashmiri" peaceful protest movement alongside the insurgency in Indian-administered Kashmir since 1989. The movement was created for the same reason as the insurgency and began after the disputed election of 1987. According to the United Nations, the Kashmiris have grievances with the Indian government, specifically the Indian military, which has committed human rights violations.

In 1994, the NGO International Commission of Jurists sent a fact finding mission to Kashmir. The ICJ mission concluded that the right of self-determination to which the peoples of Jammu and Kashmir became entitled as part of the process of partition had neither been exercised nor abandoned, and thus remained exercisable. It further stated that as the people of Kashmir had a right of self-determination, it followed that their insurgency was legitimate. It, however, did not follow that Pakistan had a right to provide support for the militants.

1999 Conflict in Kargil

In mid-1999, alleged insurgents and Pakistani soldiers from Pakistani Kashmir infiltrated Jammu and Kashmir. During the winter season, Indian forces regularly move down to lower altitudes, as severe climatic conditions makes it almost impossible for them to guard the high peaks near the Line of Control. This practice is followed by both India and Pakistan Army. The terrain makes it difficult for both sides to maintain a strict border control over Line of Control. The insurgents took advantage of this and occupied vacant mountain peaks in the Kargil range overlooking the highway in Indian Kashmir that connects Srinagar and Leh. By blocking the highway, they could cut off the only link between the Kashmir Valley and Ladakh. This resulted in a large-scale conflict between the Indian and Pakistani armies. The final stage involved major battles by Indian and Pakistani forces resulting in India recapturing most of the territories held by Pakistani forces.

Fears of the Kargil War turning into a nuclear war provoked the then-United States President Bill Clinton to pressure Pakistan to retreat. The Pakistan Army withdrew their remaining troops from the area, ending the conflict. India regained control of the Kargil peaks, which they now patrol and monitor all year long.

2000s Al-Qaeda involvement

Main article: Al-Qaeda See also: Allegations of support system in Pakistan for Osama bin LadenIn a 'Letter to American People' written by Osama bin Laden in 2002, he stated that one of the reasons he was fighting America was because of its support for India on the Kashmir issue. While on a trip to Delhi in 2002, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld suggested that Al-Qaeda was active in Kashmir, though he did not have any hard evidence. An investigation by a Christian Science Monitor reporter in 2002 claimed to have unearthed evidence that Al-Qaeda and its affiliates were prospering in Pakistan-administered Kashmir with tacit approval of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI). In 2002, a team comprising Special Air Service and Delta Force personnel was sent into Indian-administered Kashmir to hunt for Osama bin Laden after reports that he was being sheltered by the Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen. US officials believed that Al-Qaeda was helping organise a campaign of terror in Kashmir to provoke conflict between India and Pakistan. Their strategy was to force Pakistan to move its troops to the border with India, thereby relieving pressure on Al-Qaeda elements hiding in northwestern Pakistan. US intelligence analysts say Al-Qaeda and Taliban operatives in Pakistan-administered Kashmir are helping terrorists trained in Afghanistan to infiltrate Indian-administered Kashmir. Fazlur Rehman Khalil, the leader of the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, signed al-Qaeda's 1998 declaration of holy war, which called on Muslims to attack all Americans and their allies. In 2006 Al-Qaeda claim they have established a wing in Kashmir, which worried the Indian government. Indian Army Lieutenant General H.S. Panag, GOC-in-C Northern Command, told reporters that the army has ruled out the presence of Al-Qaeda in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. He said that there no evidence to verify media reports of an Al-Qaeda presence in the state. He ruled out Al-Qaeda ties with the militant groups in Kashmir including Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed. However, he stated that they had information about Al Qaeda's strong ties with Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed operations in Pakistan. While on a visit to Pakistan in January 2010, US Defense secretary Robert Gates stated that Al-Qaeda was seeking to destabilise the region and planning to provoke a nuclear war between India and Pakistan.

In June 2011, a US Drone strike killed Ilyas Kashmiri, chief of Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, a Kashmiri militant group associated with Al-Qaeda. Kashmiri was described by Bruce Riedel as a 'prominent' Al-Qaeda member, while others described him as the head of military operations for Al-Qaeda. Waziristan had by then become the new battlefield for Kashmiri militants fighting NATO in support of Al-Qaeda. Ilyas Kashmiri was charged by the US in a plot against Jyllands-Posten, the Danish newspaper at the center of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy. In April 2012, Farman Ali Shinwari a former member of Kashmiri separatist groups Harkat-ul-Mujahideen and Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, was appointed chief of al-Qaeda in Pakistan.

Reasons behind the dispute

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Kashmir conflict" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Kashmir Conflict arose from the Partition of British India in 1947 into modern India and Pakistan. Both countries subsequently made claims to Kashmir, based on the history and religious affiliations of the Kashmiri people. The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which lies strategically in the north-west of the subcontinent bordering Afghanistan and China, was formerly ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh under the paramountcy of British India. In geographical and legal terms, the Maharaja could have joined either of the two new countries. Although urged by the Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten of Burma, to determine the future of his state before the transfer of power took place, Singh demurred. In October 1947, incursions by Pakistan took place leading to a war, as a result of which the state of Jammu and Kashmir remains divided between India and Pakistan.

| Administered by | Area | Population | % Muslim | % Hindu | % Buddhist | % Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Kashmir Valley | ~4 million | 95% | 4% | – | – |

| Jammu | ~3 million | 30% | 66% | – | 4% | |

| Ladakh | ~0.25 million | 46% | – | 50% | 3% | |

| Pakistan | Gilgit-Baltistan | ~1 million | 99% | – | – | – |

| Azad Kashmir | ~2.6 million | 100% | – | – | – | |

| China | Aksai Chin | – | – | – | – | – |

| Shaksgam Valley | – | – | – | – | – | |

| ||||||