| Revision as of 03:32, 16 February 2007 edit209.206.219.3 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 10:11, 16 February 2007 edit undoLadyofHats (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,452 edits ←Undid revision 108522231 by 209.206.219.3 (talk)Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{expert-subject|Biology}} | {{expert-subject|Biology}} | ||

| {{unreferenced|date=November 2006}} | {{unreferenced|date=November 2006}} | ||

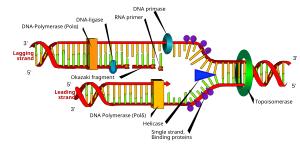

| ]. Next, a molecule of ] shown in green binds to one strand of the DNA. It moves along the strand, using it as a template for assembling a ] shown above in red of ]s and reforming a double helix. A DNA polymerase I molecule (also green) is used to bind to the other template strand (lagging strand) as the double helix opens. This molecule must synthesize discontinuous segments of polynucleotides (called ]s). Another enzyme, ] shown in violet, then stitches these together into the lagging strand.]] | ]. Next, a molecule of ] shown in green binds to one strand of the DNA. It moves along the strand, using it as a template for assembling a ] shown above in red of ]s and reforming a double helix. A DNA polymerase I molecule (also green) is used to bind to the other template strand (lagging strand) as the double helix opens. This molecule must synthesize discontinuous segments of polynucleotides (called ]s). Another enzyme, ] shown in violet, then stitches these together into the lagging strand.]] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 10:11, 16 February 2007

| This article needs attention from an expert in Biology. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. WikiProject Biology may be able to help recruit an expert. |

| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "DNA replication" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2006) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

DNA replication or DNA synthesis is the process of copying a double-stranded DNA molecule. This process is paramount to all life as we know it. The DNA replication involves copying the genetic material and passing it on to daughter cells, therefore the process is important in continuation of life.

A DNA molecule is a long polymer consisting of two strands, each composed of repeating units called nucleotides. These two strands entwine like vines and form a double helix. The two strands of DNA are antiparallel and complementary to each other. Antiparallel means that one strand is in the 5' → 3' direction, while the complementary strand is in the 3' → 5' direction (5' and 3' each mark one end of a strand). The nucleotides which make up DNA pair with each other and form base pairs such as A::T and C:::G (two dots between A and T indicate that they are bound by two hydrogen bonds, and three dots between G and C indicate the presence of three hydrogen bonds). This means that the strand running in the 5'→ 3' direction will have base A that will pair with base T on the opposite strand running in 3'→ 5' direction.

Since DNA strands are antiparallel and complementary, each strand can serve as a template for the reproduction of the opposite strand. The template strand is preserved as a whole piece and the new strand is assembled from nucleotide triphosphates. This process is called semiconservative replication. Ideally, the two resulting strands are identical, although in reality there are always errors, though proofreading and error-checking mechanisms exist to ensure a very high level of fidelity.

In a cell, this step is obligatory prior to cell division. Prokaryotes persistently replicate their DNA and creating a whole, new chromosome is a limiting step in cell division. In eukaryotes, timings are highly regulated and this occurs during the S phase of the cell cycle, preceding mitosis or meiosis I. The process may also be performed in vitro using reconstituted or completely artificial components, in a process known as PCR.

DNA may be synthesized artificially, but this process is not fundamentally a replicative process, and only produces a single strand of DNA.

Introduction

DNA replication or DNA synthesis is the process of copying a double-stranded DNA strand. Since DNA strands are antiparallel and complementary, each strand can serve as a template for the reproduction of the opposite strand. The template strand is preserved as a whole piece and the new strand is assembled from nucleotide triphosphates. This process is called semiconservative replication. Ideally, the two resulting strands are identical, although in reality there are always errors, though proofreading and error-checking mechanisms exist to ensure a very high level of fidelity.

In a cell, this step is obligatory prior to cell division. Prokaryotes persistently replicate their DNA and creating a whole, new chromosome is a limiting step in cell division.The large size of eukaryotic chromosomes and the limits of nucleotide incorporation during DNA synthesis, make it necessary for multiple origins of replication to exist in order to complete replication in a reasonable period of time. However, it is clear that at a replication origin the strands of DNA must dissociate and unwind in order to allow access to DNA polymerase.

The process may also be performed in-vitro using reconstituted or completely artificial components, in a process known as PCR. DNA may be synthesized artificially, but this process is not fundamentally a replicative process, and only produces one strand of DNA.

3 Steps for DNA polymerization

This is a description of DNA polymerization using an enzyme. This is not the synthetic, purely chemical, laboratory method of artificially synthesizing oligos in a laboratory or oligo factory. Artificially synthesized oligos are a key aspect of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

Initiation

The specific site at which DNA unwinding and initiation of replication occur is called origin of replication. DNA synthesis, although on a very general level is the same, differs between species and organisms. Having said that, depending on the organism, there may be a single origin of replication or as many as thousands per chromosome. Because bacteria (prokaryotes) on molecular level are simpler organisms than humans (eukaryotes) the initiation of DNA synthesis was first fully understood in bacteria, and model organism used was E. Coli. In 1963, Francois Jacob, Sydney Brenner and Jacques Cuzin defined all of DNA replicated from a particular origin in E. Coli as a replicon. They further proposed that this replicon must have two components that initiate replication of DNA: the replicator (an entire set of cis-acting DNA sequences that is sufficient to direct the initiation of DNA synthesis) and the initiator (a protein that specifically recognizes a particular DNA element in the replicator and activates the initiation process).

Initiator proteins have three roles:

- They bind to a specific DNA sequence and event in the replicator.

- Once bound they unwind short region of DNA adjacent to their binding site.

- They recruit additional initiation factors to the replicator.

- In E. Coli (a prokaryote) the initiator protein is DnaA, which binds to a specific sequence defining prokaryotic origin of replication oriC and starts interaction with ATP. This initial DnaA - ATP interaction results in unwinding of short region, no more than 20 base pairs long, and provides a single - stranded DNA (abbr. ssDNA) template for additional replication proteins to begin DNA synthesis. These additional replication proteins are DnaB (a helicase) and a DnaC (a helicase loader).

- In higher organisms (eukaryotes) the initiator is a protein complex called origin of recognition complex (abbr. ORC), which analogous to DnaA in prokaryotes, recognizes a specific DNA sequence and binds to it. This is followed by DNA replicating machinery assembling.

This origin of replication is unwound (i.e., the two strands are pulled apart at that site) and the partially unwound strands form a "replication bubble", with one replication fork on either end. Each group of enzymes at the replication fork moves away from the origin, unwinding and replicating the original DNA strands as they proceed. Primers mark the individual sequences and the starting points to be replicated.

The factors involved are collectively called the pre-replication complex. It consists of the following:

- A topoisomerase, which introduces negative supercoils into the DNA in order to minimize torsional strain induced by the unwinding of the DNA by helicase ahead of the replicational complex. The topoisomerase reversibly breaks the DNA strand, allowing the DNA to swivel, preventing the DNA from knotting up.

- A helicase, which unwinds and splits the DNA ahead of the fork. Thereafter, single-strand binding proteins (SSB) swiftly bind to the separated DNA, preventing the strands from reuniting.

- A primase (DnaG or RNA polymerase in prokaryotes, DNA polymerase α in eukaryotes), which generates an RNA primer to be used in DNA replication.

- A DNA holoenzyme, which in reality is a complex of proteins that together perform the "actual" replication, i.e., the polymerization of nucleotides complementary to the template strand.

- DNA polymerase III in prokaryotes

- DNA polymerase δ and DNA pol ε in eukaryotes.

Elongation

5' _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _3' <--DNA template Primer-DNA-Primer-DNA <--Okazaki fragments 3' _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _5' <--complementary DNA strand

At the beginning of elongation, an enzyme called DNA polymerase binds to the DNA and synthesizes DNA from the RNA primer, which indicates the starting point for the elongation. DNA polymerases can only synthesize the new DNA in the 5’ to 3’ direction. Because of this these enzymes can only travel on one side of the original strand without any interruption. This new strand, which proceeds from 5’ to 3’, is the leading strand. The other new strand, which proceeds from 3’ to 5’, is the lagging strand.

In prokaryotes RNA primers are removed by DNA polymerase I, which also synthesizes DNA in their place, in eukaryotes they are removed by RNase H or FEN1 and replaced with DNA by DNA polymerase δ or ε.

Since DNA synthesis only occurs in the 5' to 3' direction, the DNA of the lagging strand is replicated in pieces known as Okazaki Fragments. Each time DNA polymerase reaches the 5' end of the RNA primer for the next Okazaki fragment, it dissociates and reassociates at the 3' end of the primer. Another enzyme, DNA ligase, is necessary to connect the Okazaki fragments.

In prokaryotes, leading strand and lagging strand synthesis are coupled by the action of the DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. One complex replicates the leading and lagging strands simultaneously. During this stage helicase continues to unwind the DNA into two single strands while topoisomerases relieves the supercoiling caused by this.

Both prokaryotes and eukaryotes have DNA polymerases with proof-reading and 3' exonuclease activities. These functions increase the fidelity of replication. Prokaryotes tend to have fewer or weaker proof-reading mechanisms due to the nature of their natural selection of their gene pools.

Termination

Termination occurs when DNA replication forks meet one another or run to the end of a linear DNA molecule. Also, termination may occur when a replication fork is deliberately stopped by a special protein, called a replication terminator protein, that binds to specific sites on a DNA molecule.

When the polymerase reaches the end of a linear DNA molecule, there is a potential problem due to the antiparallel structure of DNA. Because an RNA primer must be regularly laid down on the lagging strand, the last section of the lagging-strand DNA cannot be replicated because there is no DNA template for the primer to be synthesized on. To solve this problem, the ends of most chromosomes consist of noncoding DNA that contains repeat sequences. The end of a linear chromosome is called the telomere. Cells can endure the shortening of the chromosome at the telomere to a degree, since it's necessary for chromosome stability. Many cells use an enzyme called telomerase that adds the repeat units to the end of the chromosome so the ends do not become too short after multiple rounds of DNA replication. Many simple, single-celled organisms overcome the whole problem by having circular chromosomes.

Before the DNA replication is finally complete, enzymes are used to proofread the sequences to make sure the nucleotides are paired up correctly in a process called DNA repair. If mistake or damage occurs, enzymes such as a nuclease will remove the incorrect DNA. DNA polymerase will then fill in the gap.

Equation

A chemical equation can be written that represents the process:

(DNA)n + dNTP → (DNA)n+1 + PPi

Nucleotides (dNTP) used by DNA replications contain three phosphates attached to the sugar, like ATP and are named accordingly CTP, TTP, and GTP. However, in contrast to most other processes of the cell in which only one phosphate group (Pi), the last two phosphate groups (PPi) (pyrophosphate group) are detached.

Organization of multiple replication sites

A diploid human cell contains 6 billion nucleotide pairs (contained in 46 linear chromosomes) that are copied at about 50 base pairs per second by each replication fork. Yet in a typical cell the entire replication process takes only about 8 hours. This is because there are many replication initiation sites, called origins of replication, on a eukaryotic chromosome. Replication can begin at some origins earlier than at others. As replication nears completion, "bubbles" of newly replicated DNA meet and fuse, forming two new DNA molecules.

There must be some form of regulation and organization of these multiple replication sites to prevent re-initiation of replication at origins that have already initiated replication (re-initiation would result in too many copies of the DNA). To date, two replication control mechanisms have been identified: one positive and one negative. Each replication origin site must be bound by a set of proteins called the origin recognition complex. These remain attached to the DNA at each origin throughout the replication process. In addition to the origin recognition complex, specific accessory proteins called licensing factors, must also be present for initiation of replication. Altogether, these proteins promote initiation and they represent the positive control mechanism for initiation. After the cell has signaled to the origins to initiate DNA replication, specific destruction of certain licensing factors prevents further replication cycles from occurring. Licensing factors are only replenished in cells during the cell division process, so they cannot act to reinitiate replication inappropriately before division.

See also

- Immortal DNA strand hypothesis

- Phosphoramidite (chemical DNA synthesis)

References

- Watson, Baker, Bell, Gann, Levine, Losick. Molecular Biology of the Gene, Fifth Edition (2003). ISBN 0-8053-4635-X. Pearson/Benjamin Cummings Publishing.

External links

- DNA Workshop

- WEHI-TV - DNA Replication video- Detailed DNA replication animation from different angles with description below.

- Breakfast of Champions Does Replication- creative primer on the process from the Science Creative Quarterly

- Template:McGrawHillAnimation

- Basic Polymerase Chain Reaction Protocol

- Animated Biology

- DNA makes DNA (Flash Animation)

- DNA replication info pageby George Kakaris, Biologist MSc in Applied Genetics and Biotechnology

| DNA replication (comparing prokaryotic to eukaryotic) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation |

| ||||||

| Replication |

| ||||||

| Termination | |||||||