| Revision as of 04:50, 16 February 2007 editCan't sleep, clown will eat me (talk | contribs)101,994 editsm Reverted edits by 69.231.249.55 (talk) to last version by Asiaticus← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:48, 16 February 2007 edit undo65.121.30.30 (talk) →Nationalist military uprisingNext edit → | ||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

| He also declared that Spanish soldiers would be mad to not rise for Spain against Anarchy. In turn, the leader of the communists, ], known as ''La Pasionaria'', had vowed that Calvo Sotelo's speech would be his last speech in the ''Cortes''.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Although the Nationalist generals were already at advanced stages of planning an uprising, the event is seen by some as a catalyst for what followed. | He also declared that Spanish soldiers would be mad to not rise for Spain against Anarchy. In turn, the leader of the communists, ], known as ''La Pasionaria'', had vowed that Calvo Sotelo's speech would be his last speech in the ''Cortes''.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} Although the Nationalist generals were already at advanced stages of planning an uprising, the event is seen by some as a catalyst for what followed. | ||

| ==Nationalist military uprising== | |||

| ] | |||

| On ], ], the nationalist-traditionalist rebellion long feared by some in the Popular Front government began. Its start was signalled by the phrase "Over all of Spain, the sky is clear" that was broadcast on the radio. Casares Quiroga, who had succeeded Azaña as prime minister, had in the previous weeks exiled the military officers suspected of conspiracy against the Republic, including General ] and General ], sent to the ] and to the ], respectively. Both generals immediately took control of these islands. Franco then flew to ] to see ], where the Nationalist Army of Africa were almost unopposed in assuming control. The rising was intended to be a swift ], but was botched; conversely, the government was able to retain control of only part of the country. In this first stage, the rebels failed to take all major cities -- in ] they were hemmed into the Montaña barracks. The barracks fell the next day with much bloodshed. In ], ]s armed themselves and defeated the rebels. General Goded, who arrived from the Balearic islands, was captured and later executed. The anarchists would control Barcelona and much of the surrounding ] and ] countryside for months. The Republicans held on to ] and controlled almost all of the Eastern Spanish coast and central area around Madrid. The Nationalists took most of the northwest apart from ], ] and the ] and a southern area including ], ], ], ], and ]; resistance in some of these areas led to reprisals. | |||

| ==Factions in the war== | ==Factions in the war== | ||

Revision as of 19:48, 16 February 2007

- This article is about the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939. See also Spanish Civil War, 1820-1823.

| Spanish Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Republican soldier falls in battle (Photographer - Robert Capa). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

With the support of: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Manuel Azaña Francisco Largo Caballero Juan Negrín |

Francisco Franco Gonzalo Queipo de Llano Emilio Mola | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 500,000 – 1,000,000 | |||||||

The Spanish Civil War, which lasted from July 17, 1936 to April 1, 1939, was a conflict in which the Francoists or Nationalists, led by General Francisco Franco, defeated the Republicans or Loyalists of the Second Spanish Republic.

The combatants

Republicans received weapons and volunteers from the Soviet Union, Mexico, the international Communist movement, and the International Brigades, while the Francoists received weapons and soldiers from Italy and Germany, logistical support from Portugal, and support from various Fascist organisations such as The Blueshirts and Croix de Feu. The republicans ranged from centrists who supported a moderately capitalist liberal democracy to revolutionary anarchists and socialists; their power base was primarily secular and urban, but also included landless peasants, and it was particularly strong in industrial regions like Asturias and Catalonia .

The conservative, strongly Catholic Basque Country, along with Catalonia and Galicia, sought autonomy or even independence from the central government of Madrid. This option was left open by the Republican government.

The Nationalists on the contrary opposed these separatist movements. The Francoists (Nationalists) had a generally wealthier, more conservative base of Catholic, monarchist, centralist, landowning and fascist interests, and they favoured the centralization of state power. Most Roman Catholic clergy supported the Nationalists.

Atrocities were committed on both sides during the war. Some, including the use of terror tactics against civilians, foreshadowed World War II, as did some of the military tactics. Atrocities in the Republican side were committed by groups of radical leftists against the Church or by the Stalinist NKVD (which also carried out murders of pro-Republican people, see Andreu Nin) against political enemies, on the Nationalist side these atrocities were ordered by the fascist authorities themselves in order to eradicate any trace of leftism in Spain. This included the aerial bombing of cities, the execution of school teachers (the efforts of the Republic to promote the laicism and to displace the Church from the education system were seen from the Nationalist side as an attack on the Church) or anyone who was accused of blasphemy or not going to Church on Sunday and the massive killings of civilians in the liberated cities.

While the war lasted only about three years, the political situation had already been violent for several years before. The number of casualties is disputed; estimates generally suggest that between 500,000 and 1 million people were killed.

The war started with military uprisings throughout Spain and its colonies. Republican sympathizers, soldiers and civilians, formally acting independently of the state, massacred Catholic clergy and burned down churches, monasteries and convents and other symbols of the Spanish Catholic Church which Republicans (especially the anarchists and communists) viewed as an oppressive institution supportive of the old order. The Republicans also attacked nobility, former landowners, rich farmers and industrialists.

During and after the war, the Nationalists carried out a program of mass-killing of opponents: unwanted individuals, including many non-combatants, were often jailed or, in many cases, killed by a firing squad. Trade-unionists, known Republican sympathisers and critics of Franco's regime were among the first to be targeted. The Nationalists also carried out aerial bombardment of civilian areas with strong assistance from the German and Italian air forces.

The impact of the war was massive: the Spanish economy took decades to recover. The political and emotional repercussions of the war reverberated far beyond the boundaries of Spain and sparked passion among international intellectual and political communities, passions that still are present in Spanish politics today.

Republican sympathizers proclaimed it as a struggle between "tyranny and democracy", or "fascism and liberty", and many non-Spanish young, committed reformers and revolutionaries joined the International Brigades, believing the Spanish Republic was the front line of the war against fascism. Franco's supporters, however, portrayed it as a battle between the "red hordes" of communism and anarchism on the one hand and "Christian civilization" on the other. They also stated that they were protecting the Establishment and bringing security and direction to what they felt was an ungoverned and lawless society.

Prelude

In the previous century Spain had undergone several civil wars, known as the Carlist Wars. The Spanish Civil War was considered by the Carlists as yet another crusade against secularism, though its scope and consequences were to be much greater.

In the 1933 Spanish elections, the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas) (CEDA) won the most seats in the Cortes, but not enough to form a majority. President Niceto Alcalá Zamora refused to ask its leader, José María Gil-Robles, to form a government, and instead invited Alejandro Lerroux of the Radical Republican Party, a centrist party despite its name, to do so. CEDA supported the Lerroux government; it later demanded and, on October 1 1934, received three ministerial positions. The Lerroux/CEDA government attempted to annul the social legislation that had been passed by the previous Manuel Azaña government, provoking general strikes in Valencia and Zaragoza, street conflicts in Madrid and Barcelona, and, on October 6, an armed miners' rebellion in Asturias and an autonomist rebellion in Catalonia. Both rebellions were suppressed, and were followed by mass political arrests and trials.

Lerroux's alliance with the right, his harsh repression of the revolt in 1934, and the Stra-Perlo scandal combined to leave him and his party with little support going into the 1936 election. (Lerroux himself lost his seat in parliament.)

As internal disagreements mounted in the coalition, strikes were frequent, and there were pistol attacks on unionists and clergy. In the elections of February 1936, the Popular Front won a majority of the seats in parliament. The coalition, which included the Socialist Party (PSOE), two liberal parties (the Republican Left Party of Manuel Azaña and the Republican Union Party), and Communist Party of Spain, as well as Galician and Catalan nationalists, received 34.3 percent of the popular vote, compared to 33.2 percent for the National Front parties led by CEDA. The Basque nationalists were not officially part of the Front, but were sympathetic to it. The anarchist trade union Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), which had sat out previous elections, urged its members to vote for the Popular Front in response to a campaign promise of amnesty for jailed leftists. The Socialist Party refused to participate in the new government. Its leader, Largo Caballero, hailed as "the Spanish Lenin" by Pravda, told crowds that revolution was now inevitable. Privately, however, he aimed merely at ousting the liberals and other non-socialists from the cabinet. Moderate Socialists like Indalecio Prieto condemned the left's May Day marches, clenched fists, and talk of revolution as insanely provocative.

Without the Socialists, Prime Minister Manuel Azaña, a liberal who favored gradual reform while respecting the democratic process, led a minority government. In April, parliament replaced President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, a moderate who had alienated virtually all the parties, with Azaña. Although the right also voted for Zamora's removal, this was a watershed event which inspired many conservatives to give up on parliamentary politics. Azaña was the object of intense hate by Spanish rightists, who remembered how he had pushed a reform agenda through a recalcitrant parliament in 1931-33. Joaquín Arrarás, a friend of Francisco Franco's, called him "a repulsive caterpillar of red Spain." The Spanish generals particularly disliked Azaña because he had cut the army's budget and closed the military academy when he was war minister (1931). CEDA turned its campaign chest over to army plotter Emilio Mola. Monarchist José Calvo Sotelo replaced CEDA's Gil Robles as the right's leading spokesman in parliament.

This was a period of rising tensions. Radicals became more aggressive, while conservatives turned to paramilitary and vigilante actions. According to official sources, 330 people were assassinated and 1,511 were wounded in politically-related violence; records show 213 failed assassination attempts, 113 general strikes, and the destruction of 160 religious buildings.

Deaths of Castillo & Calvo Sotelo

On July 12, 1936, José Castillo, a member of the Socialist Party and lieutenant in the Assault Guards, a special police corps created to deal with urban violence, was murdered by a 'far right' group in Madrid. The following day José Calvo Sotelo, the leader of the conservative opposition in the Cortes (Spanish parliament), was killed in revenge by Luis Cuenca who was operating in a commando unit of the Civil Guard led by Captain Fernando Condés Romero. Condés was close to the Socialist leader Indalecio Prieto, and although there is no indication that Prieto was complicit in Cuenca's decision to shoot Calvo Sotelo, the assassination of a member of parliament aroused suspicions and strong reactions amongst the Center and the Right. Calvo Sotelo was the most prominent Spanish monarchist and had protested against what he viewed as an escalating anti-religious terror, expropriations, and hasty agricultural reforms, which he considered Bolshevist and Anarchist. He instead advocated the creation of a corporative state and declared that if such a state was fascist, he was also a fascist.

He also declared that Spanish soldiers would be mad to not rise for Spain against Anarchy. In turn, the leader of the communists, Dolores Ibarruri, known as La Pasionaria, had vowed that Calvo Sotelo's speech would be his last speech in the Cortes. Although the Nationalist generals were already at advanced stages of planning an uprising, the event is seen by some as a catalyst for what followed.

Factions in the war

The active participants in the war covered the entire gamut of the political positions and ideologies of the time. The Nationalist (nacionales) side included the Carlists and Legitimist monarchists, Spanish nationalists, fascists of the Falange, Catholics, and most conservatives and monarchist liberals. On the Republican side were Basque and Catalan nationalists, socialists, communists, liberals and anarchists.

To view the political alignments from another perspective, the Nationalists included the majority of the Catholic clergy and of practising Catholics (outside of the Basque region), important elements of the army, most of the large landowners, and many businessmen. The Republicans included most urban workers, most peasants, and much of the educated middle class, especially those who were not entrepreneurs. The genial monarchist General José Sanjurjo was figurehead of the rebellion, while Emilio Mola was chief planner and second in command. Mola began serious planning in the spring, but General Francisco Franco hesitated until early July, inspiring other plotters to refer to him as "Miss Canary Islands 1936." Franco was a key player because of his prestige as a former director of the military academy and the man who suppressed the Socialist uprising of 1934. Warned that a military coup was imminent, leftists put barricades up on the roads on July 17. Franco avoided capture by taking a tugboat to the airport. From there he flew to Morocco, where he took command of the battle-hardened colonial army. Sanjurjo was killed in a plane crash on July 20, leaving effective command split between Mola in the north and Franco in the South. Franco was chosen overall commander at a meeting of ranking generals at Salamanca on September 21. He outranked Mola and by this point his Army of Africa had demonstrated its military superiority.

One of the Nationalists' principal claimed motives was to confront the anticlericalism of the Republican regime and to defend the Roman Catholic Church, which was censured for its support for the monarchy, which many on the Republican side blamed for the ills of the country. In the opening days of the war religious buildings were burnt without action on the part of the Republican authorities to prevent it. As part of the social revolution taking place, others were turned into Houses of the People. Similarly, many of the massacres perpetrated by the Republican side targeted the Catholic Clergy. Franco's religious Moroccan Muslim troops found this repulsive and for the most part fought loyally and often ferociously for the Nationalists. Articles 24 and 26 of the Constitution of the Republic had banned the Jesuits, which deeply offended many of the Nationalists. After the beginning of the Nationalist coup, anger flared anew at the Church and its role in Spanish politics. Notwithstanding these religious matters, the Basque nationalists, who nearly all sided with the Republic, were, for the most part, practicing Catholics. Pope John Paul II later canonised several people murdered for being priests or nuns.

Foreign involvement

- For a more detailed listing of foreign personel and war supplies see Spanish Civil War and Foreign Involvement

The rebellion was opposed by the government (with the troops that remained loyal to the Republic), as well as by the vast majority of urban workers, who were often members of Socialist, Communist and anarchist groups.

The British government proclaimed itself neutral; however, the British ambassador to Spain, Sir Henry Chilton, believed that a victory for Franco was in Britain's best interests and worked to support the Nationalists. British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden publicly maintained the official policy of non-intervention but privately expressed his desire that the Republicans win the war . Admiral Lord Charfield, British First Sea Lord at the time of the conflict, was an admirer of Franco and, with or without Government support, the British Royal Navy favoured the Nationalists during the conflict. As well as permitting Franco to set up a signals base on Gibraltar, the Germans were allowed to overfly Gibraltar during the airlift of the Army of Africa to Seville. The Royal Navy also provided information on Republican shipping to the Nationalists, and HMS Queen Elizabeth was used to prevent the Republican navy shelling the port of Algeciras. The German chargé d'affaires reported that the British were supplying ammunition to the Republicans, as well as passing on information about Russian arms shipments to the Germans. During the fighting for Bilbao the Royal Navy supported the Nationalist line that the River Nervión was mined, telling British shipping to keep clear of the area - and were badly discredited when a British vessel ignored the advice and sailed into the city, finding the river unmined as the Republicans had claimed. Despite this, Britain discouraged activity by its citizens supporting either side.

The Anglo-French arms embargo meant that the Republicans' only foreign source of materiél was the USSR while the Nationalists received weapons from Italy and Germany and logistical support from Portugal. The last Republican prime minister, Juan Negrín, hoped that a general outbreak of war in Europe would compel the European powers (mainly Britain and France) to finally help the Republic, but World War II would not commence until months after the Spanish conflict had ended. Ultimately neither Britain nor France intervened to any significant extent. Britain supplied food and medicine to the Republic, but actively discouraged the French government of Léon Blum from supplying weapons. The American Ambassador to Spain, was to later condemn the the League of Nations Non-Intervention Committee, saying that each of their moves had been made to serve the cause of the rebellion, and that 'This committee was the most cynical and lamentably dishonest group that history has known.'

Both Italy under Mussolini and Germany under Hitler violated the embargo and sent troops (Corpo Truppe Volontarie and Condor Legion), aircraft, and weapons to support Franco. The Italian contribution amounted to over 60,000 troops at the height of the war, and the involvement helped to increase Mussolini's popularity among Italian Catholics, as the latter had remained highly critical of their ex-Socialist fascist Duce. Italian military help to Nationalists against the anti-clerical and anti-Catholic atrocities committed by the Republican side, worked well in Italian propaganda targeting Catholics. On July 27, 1936 the first squadron of Italian airplanes sent by Benito Mussolini arrived in Spain. It has been speculated that Hitler used the Spanish Civil War issue to distract Mussolini from Hitler's own designs on and plans for Austria (Anschluss), as the authoritarian Catholic, anti-Nazi Väterländische Front government of autonomous Austria had been in alliance with Mussolini, and in 1934, the assassination of Austria's authoritarian president Engelbert Dollfuss had already successfully invoked Italian military assistance in case of a Nazi German invasion.

In addition, there were a few volunteer troops from other nations who fought with the Nationalists, such as some Irish Blueshirts under Eoin O'Duffy and the French Croix de Feu. Although these volunteers, primarily Catholics, came from around the world (including Ireland, Brazil, and the USA), there were less of them and they are not as famous as those fighting on the Republican side, and were generally less organized and hence embedded in Nationalist units whereas many Republican units were comprised entirely of foreigners.

Due to the Franco-British arms embargo, the Government of the Republic could receive material aid and could purchase arms only from the Soviet Union. These arms included 1,000 aircraft, 900 tanks, 1,500 artillery pieces, 300 armored cars, hundreds of thousands of small arms, and 30,000 tons of ammunition (some of which was defective). To pay for these armaments the Republicans used US$500 million in gold reserves. At the start of the war the Bank of Spain had the world's fourth largest reserve of gold, about US$750 million, although some assets were frozen by the French and British governments. The Soviet Union also sent more than 2,000 personnel, mainly tank crews and pilots, who actively participated in combat, on the Republican side. Nevertheless, some have contended that the Soviet government was motivated by the desire to sell arms and that they charged extortionate prices. Later, the "Moscow gold" was an issue during the Spanish transition to democracy. They have also been accused of prolonging the war because Stalin knew that Britain and France would never accept a communist government. Though Stalin did call for the repression of Republican elements that were hostile to the Soviet Union (for example, the anti-Stalininst POUM), he also made a conscious effort to limit Soviet involvement in the struggle and silence its revolutionary aspects in an attempt to remain on good diplomatic terms with the French and British. Mexico also aided the Republicans by providing rifles and food. Throughout the war, the efforts of the elected government of the Republic to resist the rebel army were hampered by Franco-British 'non-intervention', long supply lines and intermittent availability of weapons of widely variable quality.

Volunteers from many countries fought in Spain, most of them on the Republican side. 60,000 men and women fought in the International Brigades, including the American Abraham Lincoln Brigade and Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, organised in close conjunction with the Comintern to aid the Spanish Republicans. Others fought as members of the CNT and POUM militias. Those fighting with POUM most famously included George Orwell and the small ILP Contingent.

'Spain' became the cause célèbre for the left-leaning intelligentsia across the Western world, and many prominent artists and writers entered the Republic's service. As well, it attracted a large number of foreign left-wing working class men, for whom the war offered not only idealistic adventure but also an escape from post-Depression unemployment. Among the more famous foreigners participating on the Republic's side were Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell, who went on to write about his experiences in Homage to Catalonia. Orwell's novel Animal Farm was loosely inspired by his experiences and those of other members of POUM, at the hands of Stalinists when the Popular Front began to fight within itself, as were the torture scenes in 1984. Hemingway's novel For Whom the Bell Tolls was inspired by his experiences in Spain. George Seldes reported on the war for the New York Post. The third part of Laurie Lee's autobiographical trilogy ('A Moment of War') is also based on his Civil War experiences, (though the accuracy of some of his recollections has been disputed). Norman Bethune used the opportunity to develop the special skills of battlefield medicine. As a casual visitor, Errol Flynn used a fake report of his death at the battlefront to promote his movies. Despite the predominantly leftist attitude of the artistic community, several prominent writers such as Ezra Pound, Roy Campbell, Gertrude Stein, and Evelyn Waugh sided with Franco.

The United States was isolationist, neutralist, and was little concerned with what it largely saw as an internal matter in a European country. Nevertheless, from the outset the Nationalists received important support from some elements of American business. The American-owned Vacuum Oil Company in Tangier, for example, refused to sell to Republican ships and the Texas Oil Company supplied gasoline on credit to Franco until the war's end. While not supported officially, many American volunteers such as the Abraham Lincoln Battalion fought for the Republicans. Many in these countries were also shocked by the violence practiced by anarchist and POUM militias - and reported by a relatively free press in the Republican zone - and feared Stalinist influence over the Republican government. Reprisals, assassinations and other atrocities in the rebel zone were, of course, not reported nearly as widely.

Germany and the USSR used the war as a testing ground for faster tanks and aircraft that were just becoming available at the time. The Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter and Junkers Ju 52 transport/bomber were both used in the Spanish Civil War. The Soviets provided Polikarpov I-15 and Polikarpov I-16 fighters. The Spanish Civil War was also an example of total war, where the killing of civilians such as the bombing of the Basque town of Gernika by the Legión Cóndor, as depicted by Pablo Picasso in the painting "Guernica", foreshadowed episodes of World War II such as the bombing campaign on Britain by the Nazis and the bombing of Dresden or Hamburg by the Allies.

The extent of foreign involvement in the conflict has led some commentators (most notably Paul Preston) to view it as part of a wider integrated European Civil War.

As war proceeded in the Northern front, the Republican authorities arranged the evacuation of children. These Spanish War children were shipped to Britain, Belgium, the Soviet Union and other European countries. Those in Western European countries returned to their families after the war, but many of those in the Soviet Union, from Communist families, remained and experienced the Second World War and the fall of the Soviet Union.

Like the Republican side, the Nationalist side of Franco also arranged evacuations of children, women and elderly from war zones. Refugee camps for those civilians evacuated by the Nationalists were set up in Portugal, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium.

Pacifism in Spain

In the 1930s Spain also became a focus for pacifist organisations including the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the War Resisters' International whose president was the British MP and Labour Party leader George Lansbury. Prominent Spanish pacifists such as Amparo Poch y Gascón and José Brocca supported the Republicans. Brocca argued that Spanish pacifists had no alternative but to make a stand against fascism. He put this stand into practice by various means including organising agricultural workers to maintain food supplies and through humanitarian work with war refugees.

The war: 1936

- For a fully detailed chronology see Spanish Civil War chronology 1936.

In the early days of the war, over 50,000 people who were caught on the "wrong" side of the lines were assassinated or summarily executed. The numbers were probably comparable on both sides. In these paseos ("promenades"), as the executions were called, the victims were taken from their refuges or jails by armed people to be shot outside of town. The corpses were abandoned or interred in digs made by the victims themselves. Local police just noted the apparition of the corpses. Probably the most famous such victim was the poet and dramatist Federico García Lorca. The outbreak of the war provided an excuse for settling accounts and resolving long-standing feuds. Thus, this practice became widespread during the war in areas conquered. In most areas, even within a single given village, both sides committed assassinations.

Any hope of a quick ending to the war was dashed on July 21, the fifth day of the rebellion, when the Nationalists captured the main Spanish naval base at Ferrol in northwestern Spain. This encouraged the Fascist nations of Europe to help Franco, who had already contacted the governments of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy the day before. On July 26, the future Axis Powers cast their lot with the Nationalists. Nationalist forces under Franco won another great victory on September 27 when they relieved the Alcázar at Toledo.

A Nationalist garrison under Colonel Moscardo had held the Alcázar in the center of the city since the beginning of the rebellion, resisting for months against thousands of Republican troops who completely surrounded the isolated building. The inability to take the Alcázar was a serious blow to the prestige of the Republic, as it was considered inexplicable in view of their numerical superiority in the area. Two days after relieveing the siege, Franco proclaimed himself Generalísimo and Caudillo ("chieftain") while forcibly unifying the various Falangist and Royalist elements of the Nationalist cause. In October, the Nationalists launched a major offensive toward Madrid, reaching it in early November and launching a major assault on the city on November 8. The Republican government was forced to shift from Madrid to Valencia, out of the combat zone, on November 6. However, the Nationalists' attack on the capital was repulsed in fierce fighting between November 8 and 23. A contributory factor in the successful Republican defence was the arrival of the International Brigades, though only around 3000 of them participated in the battle. Having failed to take the capital, Franco bombarded it from the air and, in the following two years, mounted several offensives to try to encircle Madrid. (See also Siege of Madrid (1936-39))

On November 18, Germany and Italy officially recognized the Franco regime, and on December 23, Italy sent "volunteers" of its own to fight for the Nationalists.

The war: 1937

- For a much more detailed chronology see Spanish Civil War chronology 1937

With his ranks being swelled by Italian troops and Spanish colonial soldiers from Morocco, Franco made another attempt to capture Madrid in January and February of 1937, but failed again.

On February 21 the League of Nations Non-Intervention Committee ban on foreign national "volunteers" went into effect. The large city of Málaga was taken on February 8. On March 7 German Condor Legion equipped with Heinkel He 51 biplanes arrived in Spain; on April 26 they bombed the town of Guernica in the Basque Country; two days later, Franco's men entered the town.

After the fall of Gernika, the Republican government began to fight back with increasing effectiveness. In July, they made a move to recapture Segovia, forcing Franco to pull troops away from the Madrid front to halt their advance. Mola, Franco's second-in-command, was killed on June 3, and in early July, despite the fall of Bilbao in June, the government actually launched a strong counter-offensive in the Madrid area, which the Nationalists repulsed with some difficulty. The clash was called "Battle of Brunete" (Brunete is a town in the province of Madrid).

After that, Franco regained the initiative, invading Aragon in August and then taking the city of Santander (now in Cantabria). Two months of bitter fighting followed and, despite determined Asturian resistance, Gijón (in Asturias) fell in late October, which effectively ended the war in the North.

Meanwhile, on August 28, the Vatican recognized Franco (possibly under pressure from Mussolini), and at the end of November, with the Nationalists closing in on Valencia, the government moved again, to Barcelona.

The war: 1938

- For a much more detailed chronology see Spanish Civil War chronology 1938-1939

The battle of Teruel was an important confrontation between Nationalists and Republicans. The city belonged to the Republicans at the beginning of the battle, but the Nationalists conquered it in January. The Republican government launched an offensive and recovered the city, however the Nationalists finally conquered it for good by February 22. On April 14, the Nationalists broke through to the Mediterranean Sea, cutting the government-held portion of Spain in two. The government tried to sue for peace in May, but Franco demanded unconditional surrender, and the war raged on.

The government now launched an all-out campaign to reconnect their territory in the Battle of the Ebro, beginning on July 24 and lasting until November 26. The campaign was militarily successful, but was fatally undermined by the Franco-British appeasement of Hitler in Munich. The concession of Czechoslovakia destroyed the last vestiges of Republican morale by ending all hope of an anti-fascist alliance with the great powers. The retreat from the Ebro all but determined the final outcome of the war. Eight days before the new year, Franco struck back by throwing massive forces into an invasion of Catalonia.

The war: 1939

- For a much more detailed chronology see Spanish Civil War chronology 1938-1939

The Nationalists conquered Catalonia in a whirlwind campaign during the first two months of 1939. Tarragona fell on January 14, followed by Barcelona on January 26 and Girona on February 5. Five days after the fall of Girona, the last resistance in Catalonia was broken.

On February 27, the governments of the United Kingdom and France recognized the Franco regime.

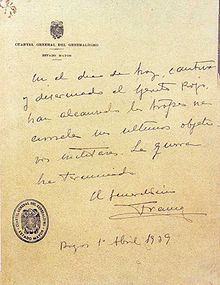

Only Madrid and a few other strongholds remained for the government forces. On March 28, with the help of pro-Franco forces inside the city (the "fifth column" General Mola had mentioned in propaganda broadcasts in 1936), Madrid fell to the Nationalists. The next day, Valencia, which had held out under the guns of the Nationalists for close to two years, also surrendered. Victory was proclaimed on April 1, when the last of the Republican forces surrendered.

After the end of the War, there were harsh reprisals against Franco's former enemies on the left, when thousands of Republicans were imprisoned and between 10,000 and 28,000 executed. Many other Republicans fled abroad, especially to France and Mexico.

Social revolution

Main article: Spanish Revolution- For for the anti-religious persecution caused by the social revolution see Religious Persecution in the Spanish Civil War

In the anarchist-controlled areas, Aragon and Catalonia, in addition to the temporary military success, there was a vast social revolution in which the workers and the peasants collectivised land and industry, and set up councils parallel to the paralyzed Republican government. This revolution was opposed by both the Soviet-supported communists, who ultimately took their orders from Stalin's politburo (which feared a loss of control), and the Social Democratic Republicans (who worried about the loss of civil property rights). The agrarian collectives had considerable success despite opposition and lack of resources, as Franco had already captured lands with some of the richest natural resources.

As the war progressed, the government and the communists were able to leverage their access to Soviet arms to restore government control over the war effort, both through diplomacy and force. Anarchists and the POUM were integrated with the regular army, albeit with resistance; the POUM was outlawed and falsely denounced as an instrument of the fascists. In the May Days of 1937, many hundreds or thousands of anti-fascist soldiers fought one another for control of strategic points in Barcelona, recounted by George Orwell in Homage to Catalonia.

People

Template:Important Figures in the Spanish Civil War

Political parties and organizations

| The Popular Front (Republican) | Supporters of the Popular Front (Republican) | Nationalists (Francoist) |

|---|---|---|

|

The Popular Front was an electoral alliance formed between various left-wing and centrist parties for elections to the Cortes in 1936, in which the alliance won a majority of seats.

|

|

Virtually all Nationalist groups had very strong Roman Catholic convictions and supported the native Spanish clergy.

|

Notes

- Good examples of this kind of tactics in the Nationalist side can be found on the Bombing of Guernika or the Killing of Badajoz , . Other stories of people who were murdered by the fascists because of their beliefs: (Sources in Spanish).

- 1936 Elections on Spartacus Schoolnet. Accessed 11 October 2006.

- Preston, Paul, "Spain 1936: From Coup d'Etat to Civil War," History Today, Volume: 36 Issue: 7, July 1986, pp. 24-29

- ^ Preston, Paul, Franco and Azaña, Volume: 49 Issue: 5, May 1999, pp. 17-23 Cite error: The named reference "Preston" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- The statistics on assassinations, destruction of religious buildings, etc. immediately before the start of the war come from The Last Crusade: Spain: 1936 by Warren Carroll (Christendom Press, 1998). He collected the numbers from Historia de la Persecución Religiosa en España (1936-1939) by Antonio Montero Moreno (Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 3rd edition, 1999).

- Bullón de Mendoza, Alfonso Calvo Sotelo: Vida y muerte (2004) Barcelona. Thomas, Hugh The Spanish Civil War (1961, rev. 2001) New York pp. 196-198 and p.309. Condés was a close personal friend of Castillo. His squad had originally gone looking to arrest Gil Robles as a reprisal for Castillo's murder, but when Robles was not at home they went to the house of Calvo Sotelo. Thomas concluded that the intention of Condés was to arrest Calvo Sotelo and that Cuenca acted on his own initiative, although he acknowledges other sources that dispute this finding. Cuenca and Condés were both killed in action in the first Rebel offensive against Madrid shortly after the start of the war.

- Preston, Paul, "From rebel to Caudillo: Franco's path to power," History Today Volume: 33 Issue: 11, November 1983, pp. 4-10

- notes to the documentary Reportaje Del Movimiento Revolucionario en Barcelona, Hastings Free TV

- Thousands of Servant of God candidates for sainthood have been accepted by the Vatican "General Index MARTYRS OF THE RELIGIOUS PERSECUTION DURING THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (X 1934, 36-39)"

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2001 reissued). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-100148-8.

- Speech delivered by Premier Benito Mussolini. Rome, Italy, February 23, 1941

- Soviet Union in the Spartacus Schoolnet series on the Spanish Civil War. Accessed 12 October 2006.

- The Soviet Union and the Spanish Civil War, Compass, April 1996, No. 123 (published by Communist League, UK). Accessed 12 October 2006.

- Neal Ascherson, How Moscow robbed Spain of its gold in the Civil War, Guardian Media Group, 1998: review of Gerald Howson, Arms For Spain. Accessed 12 October 2006.

- Paul Preston, “A Concise History of the Spanish Civil War”, (London, 1986), p.107

- Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, (1961) p. 176

Bibliography

- Alpert, Michael (2004). A New International History of the Spanish Civil War. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-1171-1.

- Beevor, Antony (2001 reissued). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-100148-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Peter Taaffe reviews Battle for Spain - The Spanish Civil War of 1936-39 by Anthony Beevor (Weidenfeld and Nicolson £25).

- Brenan, Gerald (1990, reissued). The Spanish labyrinth: an account of the social and political background of the Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39827-4.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link)

- Carr, Raymond (Introduction; no editor named), Images of the Spanish Civil War, London (Allen & Unwin) 1986.

- Graham, Helen (2002). The Spanish republic at war, 1936-1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45932-X.

- Enzensberger,Christian,"The short summer of Anarchy"

- Howson, Gerald (1998). Arms for Spain. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-24177-1.

- Jackson, Gabriel (1965). The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931-1939. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00757-8.

- Koestler, Arthur (1983). Dialogue with death. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-34776-5.

- Kowalsky, Daniel. La Union Sovietica y la Guerra Civil Espanola. Barcelona: Critica. ISBN 84-8432-490-7.

- Malraux, André (1941). L'Espoir (Man's Hope). New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-394-60478-4.

- Moa, Pío; Los Mitos de la Guerra Civil, La Esfera de los Libros, 2003.

- Orwell, George (2000, first published in 1938). Homage to Catalonia. London: Penguin Books in association with Martin Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-14-118305-5.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link)

- Payne, Stanley (2004). The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism. New Haven ; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10068-X.

- Preston, Paul (1978). The Coming of the Spanish Civil War. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-23724-2.

- Preston, Paul, A Concise History of the Spanish Civil War, London (Fontana Press) 1996.

- Puzzo, Dante Anthony (1962). Spain and the great powers, 1936-1941. Freeport, N.Y: Books for Libraries Press (originally Columbia University Press, N.Y.). ISBN 0-8369-6868-9.

- Radosh, Ronald (2001). Spain betrayed: the Soviet Union in the Spanish Civil War. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08981-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Thomas, Hugh (2003 reissued). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-101161-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Walters, Guy (2006). Berlin Games – How Hitler Stole the Olympic Dream (Chapter Six contains an account of how the outbreak of fighting in Barcelona affected those visiting the abortive People's Olympiad). London, New York: John Murray (UK), HarperCollins (US). ISBN 0-7195-6783-1, 0-0608-7412-0.

See also

- Second Spanish Republic

- Anarchism in Spain

- Spanish Revolution

- International Brigades

- Ireland and the Spanish Civil War

- Bombing of Gernika

- Proxy war

- European Civil War

Related films

- Raza (Jose Luis Saenz de Heredia, 1942)

- For Whom the Bell Tolls (Sam Wood, 1943, from the Ernest Hemingway novel)

- The Heifer (La vaquilla) (Luis García Berlanga, 1985)

- ¡Ay, Carmela! (Directed by Carlos Saura, Spain/Italy 1990) The title is a reference to the song "Quinta Brigada", which boasts of the valor of the Republican troops and laments their lack of supplies and air support.

- Pan's Labyrinth (El Laberinto del Fauno) Guillermo del Toro, 2006

- Land and Freedom (Ken Loach, 1995)

- Libertarias (Vicente Aranda, 1996)

- Vivir la Utopia (Living Utopia) by Juan Gamero, Arte-TVE, Catalunya 1997

- La Lengua de las Mariposas (The Tongue of the Butterflies), José Luis Cuerda, 1999)

- Soldados de Salamina (David Trueba, 2002)

- El espinazo del diablo (Guillermo del Toro, 2001)

Related literature

- Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell(1938)

- For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway (1940)

- 40 Preguntas Fundamentales sobre la Guerra Civil by Stanley G. Payne (2006)

- The Living and the Dead by Patrick White (1941)

- As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee (1969)

- A Moment of War by Laurie Lee (1991)

- The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood (2000)

- The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón (2001)

- L'espoir by Andre Malraux

- Diamond square by Mercè Rodoreda (1962)

- Les Grands cimetieres sous la Lune by Georges Bernanos

- Spain in my hearth (España en el corazón) by Pablo Neruda

On the immediate Post-Civil War:

External links

- Imperial War Museum Collection of Spanish Civil War Posters hosted by AHDS Visual Arts

- Documents on Irish involvement in the SCW 1936-39

- The Spanish Civil War, by George Orwell

- Constitución de la República Española (1931)

- Professor Marek Jan Chodakiewicz on The Spanish Civil War

- A collection of essays by Albert and Vera Weisbord with about a dozen essays written during and about the Spanish Civil War.

- Anarchism in the Spanish Revolution

- The Anarcho-Statists of Spain, a different view of the anarchists in the Spanish Civil War

- A reply to the above by an anarchist

- A description, according to the Vatican, of the religious persecution suffered by Catholics during the Spanish Civil War (in Spanish).

- A History of the Spanish Civil War, excerpted from a U.S. government country study.

- Spanish Civil War Info From Spartacus Educational

- La Cucaracha, The Spanish Civil War Diary, an excellent and detailed chronicle of the events of the war

- American Jews in Spanish Civil War

- Ronald Hilton, Spain, 1931-36, From Monarchy to Civil War, An Eyewitness Account,

- Columbia Historical Review Dutch Involvement in the Spanish Civil War

- Noam Chomsky's Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship

- Civil War Documentaries made by the CNT

- Spanish Civil War and Revolution text archive in the libcom.org library

- Spanish Civil War and Revolution image gallery - photographs and posters from the conflict

- The Spanish Civil War and Revolution 1936-1939 Web sites, articles, books & pamphlets online, and films (on Tidsskriftcentret.dk)

- Causa General, conclusions of the process started by Franco's government after the war to judge their enemies' actions during the conflict

- Books on the Spanish Civil War Spanish Civil War Books

- With the Reds in Andalusia, By Joe Monks, 1985. An Irish member of the Int Brigade.

- Irish and Jewish Volunteers in the Spanish Anti-Fascist War Pamphlet by Manus O'Riordan

- O'Duffy's Bandera in Spain

- The Spanish Revolution, 1936-39 articles & links, from Anarchy Now!

- Juan García Oliver, Los Organismos Revolucionarios: El Comité Central de las Milicias Antifascistas de Cataluña

- Asociacion Frente de Aragonphotos of the uniforms and insignia of Spanish Civil War units.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: