| Revision as of 00:11, 28 May 2022 edit1980fast (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users73,703 editsm →Effects: PunctuationTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:09, 6 June 2022 edit undo2a02:aa13:7200:9880:55b9:46a6:aa28:27b9 (talk) LLLTags: Reverted blanking Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

| | succeeded = <!-- Succeeded by - example: The Great Indian famine of 1876 --> | | succeeded = <!-- Succeeded by - example: The Great Indian famine of 1876 --> | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Special Period''' ({{lang-es|Período especial|link=no}}), officially the '''Special Period in the Time of Peace''' ({{lang|es|Período especial en tiempos de paz}}), was an extended period of ] in ] that began in 1991<ref>{{cite book |last=Henken |first=Ted |date=2008 |title=Cuba: A Global Studies Handbook |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Mv7anQoCbzgC&pg=PT467 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |page=438 |isbn=9781851099849 |access-date=30 June 2014 |via=] }}</ref> primarily due to the ] and, by extension, the ]. The ] of the Special Period was at its most severe in the early to mid-1990s, before slightly declining in severity towards the end of the decade once ]'s ] emerged as Cuba's primary trading partner and diplomatic ally, and especially after the year 2000 once ] improved under the presidency of ]. | |||

| It was defined primarily by extreme reductions of rationed foods at state-subsidized prices, the severe shortages of ] energy resources in the form of ], ], and other ] derivatives that occurred upon the implosion of economic agreements between the petroleum-rich Soviet Union and Cuba, and the shrinking of an economy overdependent on Soviet imports.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1084-there-is-no-food-coping-with-food-scarcity-in-cuba-today |title="There is no food": Coping with Food Scarcity in Cuba Today |first=Hanna |last=Garth |publisher=] |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170613221118/https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1084-there-is-no-food-coping-with-food-scarcity-in-cuba-today |date=23 March 2017 |archive-date=13 June 2017 |access-date=9 August 2020 }}</ref> The period radically transformed Cuban society and the economy, as it necessitated the introduction of ], decreased use of automobiles, and overhauled industry, health, and diet countrywide. People were forced to live without many goods and services that had been available since the beginning of the 20th century. | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| ]In 1991, the Soviet Union ], resulting in a large-scale economic collapse throughout the newly independent states which once comprised it.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Kozameh|first=Sara|date=30 January 2021|title=How Cuba Survived and Surprised in a Post-Soviet World|url=https://jacobinmag.com/2021/01/we-are-cuba-review-socialism-soviet-union|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=2 February 2021|website=]}}</ref> During its existence, the Soviet Union provided Cuba with large amounts of ], food, and machinery.<ref name=":0" /> In the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba's ] shrunk 35%, imports and exports both fell over 80%, and many domestic industries shrank considerably.<ref name=":0" /> Food and weapon imports stopped or severely slowed.<ref name=":1"> | ]In 1991, the Soviet Union ], resulting in a large-scale economic collapse throughout the newly independent states which once comprised it.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Kozameh|first=Sara|date=30 January 2021|title=How Cuba Survived and Surprised in a Post-Soviet World|url=https://jacobinmag.com/2021/01/we-are-cuba-review-socialism-soviet-union|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=2 February 2021|website=]}}</ref> During its existence, the Soviet Union provided Cuba with large amounts of ], food, and machinery.<ref name=":0" /> In the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba's ] shrunk 35%, imports and exports both fell over 80%, and many domestic industries shrank considerably.<ref name=":0" /> Food and weapon imports stopped or severely slowed.<ref name=":1"> | ||

| Garth, Hanna. 2009 NAPA Bulletin.</ref> The largest immediate impact was the loss of nearly all of the ] imports from the ];<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite web | Garth, Hanna. 2009 NAPA Bulletin.</ref> The largest immediate impact was the loss of nearly all of the ] imports from the ];<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite web | ||

| Line 51: | Line 46: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| </ref> Cuba's oil imports dropped to 10% of pre-1990 amounts.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.historyofcuba.com/history/havana/lperez2.htm|title=Cuba's Special Period|website=www.historyofcuba.com}}</ref>{{Better source needed|date=February 2021}} Before this, Cuba had been re-exporting any Soviet petroleum it did not consume to other nations for profit, meaning that petroleum had been Cuba's |

</ref> Cuba's oil imports dropped to 10% of pre-1990 amounts.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.historyofcuba.com/history/havana/lperez2.htm|title=Cuba's Special Period|website=www.historyofcuba.com}}</ref>{{Better source needed|date=February 2021}} Before this, Cuba had been re-exporting any Soviet petroleum it did not consume to other nations for profit, meaning that petroleum had been Cuba's orks. The lack of resources to purchase the electronic equipment to produce beats and tracks gives Cuban rap a raw feel that paralleled that of "]" music in the US.<ref>Pacini-Hernandez, Deborah and ]''. "The emergence of rap Cubano: An historical perspective." In ''Music, Space, and Place'', editors Whitely, Bennett, and Hawkins, 89–107. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2004.''</ref> | ||

| |url=http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/country/country_energy_data.cfm?fips=CU | |||

| |title=Cuba Energy Profile | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |access-date=20 January 2008 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101116024012/http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/country/country_energy_data.cfm?fips=CU | |||

| |archive-date=16 November 2010 }} | |||

| </ref> The effect of this was severe, with many Cuban industries being unable to run without such petroleum.<ref name=":0" /> Entirely dependent on ]s to operate, the major underpinnings of Cuban society—its transport, industrial and agricultural systems—were paralyzed.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} There were extensive losses of productivity in both ],<ref name=":0" /> which was dominated by modern industrial ]s, ], and ], all of which required petroleum to run{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}}, and in Cuban industrial capacity.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| The early stages of the Special Period were defined by a general breakdown in transportation and agricultural sectors, fertilizer and pesticide stocks (both of those being manufactured primarily from petroleum derivatives), and widespread food shortages.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} Australian and other ] arriving in Cuba at the time began to distribute aid and taught their techniques to locals, who soon implemented them in Cuban fields, raised beds, and urban rooftops across the nation.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} ] was soon after mandated by the Cuban government, supplanting the old industrialized form of agriculture Cubans had grown accustomed to.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} ], ], and innovative modes of ] had to be rapidly developed.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} For a time, waiting for a bus could take three hours, power outages could last up to sixteen hours, food consumption was cut back to one-fifth of its previous level and the average Cuban lost about nine kilograms (twenty pounds).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Donovan |first1=Sandy |last2=Rao |first2=Sujay |last3=Sandmann |first3=Alexa L. |date=2008 |title=Teens in Cuba |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8YzDOtRjNlcC&q=cuban+lost+kilograms&pg=PT14 |publisher=Capstone |page=26 |isbn=9780756538514 |access-date=1 July 2014 }}</ref> The average daily dietary energy consumption of Cuban citizens during the periods of 1990–92 and 1995–97 were 2720 and 2440 kcal/person/day respectively. By 2003 average caloric intake had risen to 3280 kcal/person/day.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web|last=|date=|title=Archived Copy|url=http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/documents/food_security_statistics/FoodConsumptionNutrients_en.xls#|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091007201703/http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ess/documents/food_security_statistics/FoodConsumptionNutrients_en.xls#|archive-date=7 October 2009|access-date=29 July 2021|website=}}</ref> According to the FAO, the average minimum daily energy requirement is about {{convert|1800|kcal}} per person.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|title=Hunger Portal|url=http://www.fao.org/hunger/en/#jfmulticontent_c130584-2|url-status=live|access-date=29 July 2021|publisher=FAO}}</ref> | |||

| During the early years of the crisis, United States law allowed ] in the form of food and medicine by private groups.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} Then in March 1996, the ] imposed further penalties on foreign companies doing business in Cuba, and allowed U.S. citizens to sue foreign investors who use American-owned property seized by the ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Hillyard |first1=Mick |last2=Miller |first2=Vaughne |date=14 December 1998 |title=Cuba and the Helms–Burton Act |url=http://www.parliament.uk/commons/lib/research/rp98/rp98-114.pdf |journal=House of Commons Library Research Papers |publisher=Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. |volume=98 |issue=114 |pages=3 |access-date=26 June 2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000819014257/http://www.parliament.uk/commons/lib/research/rp98/rp98-114.pdf |archive-date=19 August 2000 }}</ref> | |||

| The Cuban government was also forced to contract out more lucrative economic and tourism deals with various Western European and South American nations in an attempt to earn the foreign currency necessary to replace the lost Soviet petroleum via the international markets.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} Additionally faced with a near-elimination of imported ] and other ]-based supplies, Cuba closed refineries and factories across the country, eliminating the country's industrial arm and millions of jobs.{{citation needed|date=November 2020}} The government then proceeded to replace these lost jobs with employment in ] and other homegrown initiatives, but these jobs often did not pay as well, and Cubans on the whole became economically poorer.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} Alternative transport, most notably the Cuban "camels", immense 18-wheeler tractor trailers retrofitted as passenger buses meant to carry hundreds of Cubans each, flourished.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} Food-wise, meat and dairy products, having been extremely fossil fuel dependent in their former ] methods, soon diminished in the Cuban diet.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} In a shift notable for being generally anathema to Latin American food habits, the people of the island by necessity adopted diets higher in ], fresh produce, and ultimately more ] in character.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} No longer needing sugar as desperately for a ]—the oil-for-sugar program the Soviets had contracted with Cuba had, of course, dissipated—Cuba hurriedly diversified its agricultural production, utilizing former ] fields to grow consumables such as ] and other fruit and vegetables.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} The Cuban government also focused more intensely on cooperation with ] once the ] ] was elected president in 1998.{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} | |||

| === Economic impact === | |||

| From the start of the crisis to 1995, Cuba saw its ] shrink 35%, and it took another five years for it to reach pre-crisis levels, comparable to the length seen during the ] in the United States.<ref name=":0" /> Agricultural production fell 47%, construction fell by 74%, and manufacturing capacity fell 90%.<ref name=":0" /> Much of this decline stemmed from a stoppage in oil exports from the former ].<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| In response, the Cuban government implemented a series of ] policies.<ref name=":0" /> The Cuban government eliminated 15 ministries, and cut defense spending by 86%.<ref name=":0" /> During this time, the government maintained and increased spending on various forms of ], such as ] and social services.<ref name=":0" /> From 1990 to 1994, the share of gross domestic product spent on healthcare increased 13%, and the share spent on welfare increased 29%.<ref name=":0" /> Such policy priorities have led to historian Helen Yaffe dubbing them "humanistic austerity".<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ===Food shortages=== | |||

| During the Special Period, Cuba experienced a period of widespread ].<ref name=":1" /> In academic circles, there is debate over whether such insecurity constitutes a ].<ref name=":0" /><ref name="cmajspecialperiod" /> The primary cause of this was the ], who exported large quantities of cheap food to Cuba.<ref name=":1" /> In the absence of such food imports, food prices in Cuba increased, while government-run institutions began offering less food, and food of lower quality.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| ==== Caloric intake statistics ==== | |||

| A plethora of research shows that the Special Period resulted in a decrease in ] among Cuban citizens. One study estimates that caloric intake fell by 27% from 1990 to 1996.<ref name=":1" /> A report by the ] estimates that daily nutritional intake fell from {{convert|3052|Cal|abbr=out}} per day in 1989 to {{convert|2099|Cal}} per day in 1993. Other reports indicate even lower figures, {{convert|1863|Cal}} per day. Some estimates indicate that the very old and children consumed only {{convert|1450|Cal}} per day.<ref name="fas">{{cite web|title=Cuba's Food & Agriculture Situation Report|url=http://www.fas.usda.gov/itp/cuba/CubaSituation0308.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130312234248/http://www.fas.usda.gov/itp/cuba/CubaSituation0308.pdf|archive-date=12 March 2013}}</ref> FAO statistics show that the average daily dietary energy consumption of Cuban citizens during the periods of 1990–92 and 1995–97 were 2720 and 2440 kcal/person/day respectively. By 2003 average caloric intake had risen to 3280 kcal/person/day.<ref name=":2" /> According to the ], the recommended minimum ranges from 2,100 to 2,300 kcal/person/day <ref name="fas" /> | |||

| === Impact on public health === | |||

| During the Special Period, indicators of Cuban health showed a mixed impact. Unlike Russia, which saw a significant drop in life expectancy during the 1990s, Cuba actually saw an increase, from 75.0 years in 1990 to 75.6 years in 1999.<ref name=":0" /> During the Special Period, child mortality rates also dropped.<ref name=":0" /> One researcher from ] described the Special Period as "the first, and probably the only, natural experiment, born of unfortunate circumstances, where large effects on diabetes, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality have been related to sustained population-wide weight loss as a result of increased physical activity and reduced caloric intake".<ref name="francocrisis">{{cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/sep/27/cuba.international|title=Economic crisis boost to health of Cubans |work=] |first=Rory |last=Carroll |date=27 September 2007 |access-date=23 May 2010}}</ref> | |||

| A paper in the '']'', says that "during 1997–2002, there were declines in deaths attributed to diabetes (51%), coronary heart disease (35%), stroke (20%), and all causes (18%). An outbreak of neuropathy and a modest increase in the all-cause death rate among the elderly were also observed."<ref name="cubaHealth">{{cite journal |date=19 September 2007 |journal=] |title=Impact of energy intake, physical activity, and population-wide weight loss on cardiovascular disease and diabetes mortality in Cuba, 1980–2005 |pmid=17881386 |doi=10.1093/aje/kwm226 |volume=166 |issue=12 |pages=1374–80 |last1=Franco |first1=M |last2=Orduñez |first2=P |last3=Caballero |first3=B |display-authors=etal |doi-access=free }}</ref> This was caused by how the population tried to reduce the energy store without reducing the nutritional value of the food.<ref name="cubaHealth" /> | |||

| A letter published in the '']'' (''CMAJ'') criticized the ''American Journal of Epidemiology'' for not taking all factors into account and says that "The famine in Cuba during the Special Period was caused by political and economic factors similar to the ones that caused a ] in the mid-1990s. Both countries were run by authoritarian regimes that denied ordinary people the food to which they were entitled when the public food distribution collapsed; priority was given to the elite classes and the military. In North Korea, 3%–5% of the population died; in Cuba the death rate among the elderly increased by 20% from 1982 to 1993." The name of the author of the article in ''CMAJ'' was withheld in order to safeguard her or his right to free communication.<ref name="cmajspecialperiod">{{cite journal |title=Health consequences of Cuba's Special Period |journal=] |volume=179 |issue=3 |page=257 |date=29 July 2008 |doi=10.1503/cmaj.1080068 |pmc=2474886 |pmid=18663207 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Effects== | |||

| ===1994 protest=== | |||

| {{Main|August 1994 protest in Cuba}} | |||

| Hundreds of Cubans protested in Havana on 5 August 1994, some chanting "{{lang|es|Libertad!}}" ("Freedom!"). The protest, in which some protesters threw rocks at police, was dispersed by the police after a few hours.<ref name="cancubachange">{{cite journal |url=http://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/gratis/Gutierrez-20-1.pdf |title=Can Cuba Change? |first1=Carl |last1=Gershman |author2=Orlando Gutierrez |journal=] |date=January 2009 |volume=20 |issue=1 |access-date=26 August 2009 |archive-date=18 September 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090918225042/http://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/gratis/Gutierrez-20-1.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> A paper published in the '']'' argued that this was the closest that the Cuban opposition could come to asserting itself decisively.<ref name="cancubachange"/> | |||

| ===Energy crisis=== | |||

| Immediate actions taken by the government included televising an announcement of the expected ] a week before the ] notified the ] that they would not be delivering the expected quota of ]. ]s were asked to reduce their ] in all areas and to use ] and ]. As time went on, the administration developed more structured strategies to manage the long-term energy/economic crisis as it stretched into the 21st century.<ref name="poc_cuba"/> | |||

| ===Food rationing=== | |||

| {{See also|Rationing in Cuba}} | |||

| ] was intensified. Monthly allocations for families were based on basic minimum requirements as recommended by the ]. | |||

| === Housing, land distribution, and urban planning === | |||

| The cost of producing ] and the scarcity of tools and of building materials increased the pressure on already overcrowded housing. Even before the ], extended families lived in small apartments (many of which were in very poor condition) to be closer to an urban area. To help alleviate this situation, the government engaged in land-distribution where they supplemented larger government-owned farms with privately owned ones. Small homes were built in rural areas and land was provided to encourage families to move, to assist in food production for themselves, and to sell in local farmers' markets. As the film '']'' discusses, ] developed which were owned and managed by groups, as well as creating opportunities for allowing them to form "service co-ops" where credit was exchanged and group purchasing-power was used to buy seeds and other scarce items.<ref name="poc_cuba">]''] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101016235947/http://www.powerofcommunity.org/cm/index.php |date=16 October 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Transportation=== | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| File:El Camello.jpg|The "camel" (so called because of its two "humps") bus-trailers were introduced during the period. This one is from 2006 in Havana. | |||

| File:A bike taxi and large bus street scene in Cuba.jpg|A camel and a taxi ] in Havana, 2005 | |||

| File:DirkvdM lada limousine.jpg|A ] stretched as a limousine taxi in ], 2006 | |||

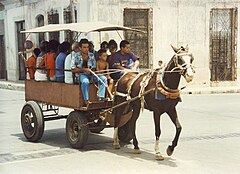

| File:Cuban transport.jpg|A horse-drawn taxi in ], 1994 | |||

| File:Bicicleta de Tres Cuba.jpg|A family of three sharing a bicycle in 1994 | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| Cubans were accustomed to cars as a convenient mode of transport. It was a difficult shift during the Special Period to adjust to a new way of managing the transport of thousands of people to school, to work and to other daily activities. With the realization that food was the key to survival, transport became a secondary worry and walking, ], and carpooling became the norm. Privately owned vehicles are not common; ownership is not seen as a right but as a privilege awarded for performance. ] is creative and takes on the following forms: | |||

| * Cars – old US cars common in Cuba are used as taxis to transport from six to eight passengers, stopping at locations as needed. | |||

| * Trucks – canopies and steps were added to accommodate more passengers and protect them from the natural elements; or open "dump-truck buses" are used. | |||

| * Bikes – 1.2 million bicycles were purchased from China and distributed as well as another half a million produced in Cuba. | |||

| * "]" – Conversion of semi-truck flatbeds into bus-like vehicles that hold up to 300 passengers. | |||

| * Government vehicles pick up passengers as needed. | |||

| * Horses and mules are used as well as bike- and horse-drawn carriages with taxi licenses are numerous both in rural and urban areas. | |||

| * Convenience for the individual is secondary to efficient use of energy. | |||

| ===Agriculture=== | |||

| {{see also|Organoponico}} | |||

| ] included ] and overuse of its agricultural land. Before the crisis, Cuba used more ]s than the United States. Lack of fertilizer and agricultural machinery caused a shift towards organic farming and urban farming. Cuba still has food rationing for basic staples. Approximately 69% of these rationed basic staples (wheat, vegetable oils, rice, etc.) are imported.<ref name="The Paradox of Cuban Agriculture">{{cite news|url=http://monthlyreview.org/2012/01/01/the-paradox-of-cuban-agriculture|title=The Paradox of Cuban Agriculture |work=]}}</ref> Overall, however, approximately 16% of food is imported from abroad.<ref name="The Paradox of Cuban Agriculture"/> | |||

| Initially, this was a very difficult situation for Cubans to accept; many came home from studying abroad to find that there were no jobs in their fields. It was pure survival that motivated them to continue and contribute to survive through this crisis. The documentary, ''The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil'', states that today, farmers make more money than most other occupations.<ref name="poc_cuba"/> | |||

| Due to a poor economy, there were many crumbling buildings that could not be repaired. These were torn down and the empty lots lay idle for years until the food shortages forced Cuban citizens to make use of every piece of land. Initially, this was an ''ad-hoc'' process where ordinary Cubans took the initiative to grow their own food in any available piece of land. The government encouraged this practice and later assisted in promoting it. Urban gardens sprang up throughout the capital of Havana and other urban centers on roof-tops, patios, and unused parking lots in raised beds as well as "squatting" on empty lots. These efforts were furthered by Australian agriculturalists who came to the island in 1993 to teach ], a sustainable agricultural system, and to "train the trainers".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://members.optusnet.com.au/~cohousing/cuba/an95rpp1.htm |title=AIDAB/NGO Cooperation Program, Food Gardener Education in Urban Havana, 1995, Final Report from the Field |last1=Tiller |first1=Adam |date=1995 |website=Australian Conservation Foundation, Cuba |access-date=21 July 2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090816231941/http://members.optusnet.com.au/~cohousing/cuba/an95rpp1.htm |archive-date=16 August 2009 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://members.optusnet.com.au/~cohousing/cuba/gt_esp.htm |title=Información sobre la dirección del proyecto en Cuba: el Green Team. |last1=Tiller |first1=Adam |date=1996 |website=Foundation for Nature and Humanity's Permaculture Project |access-date=30 June 2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090816232016/http://members.optusnet.com.au/~cohousing/cuba/gt_esp.htm |archive-date=16 August 2009 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://members.optusnet.com.au/~cohousing/cuba/havad02.htm |title=Job Advertisement, Permaculture Development Officer, Urban Permaculture Program Havana, Cuba |last1=Tiller |first1=Adam |date=1997 |website=Foundation for Nature and Humanity's Permaculture Project |access-date=30 June 2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090816232026/http://members.optusnet.com.au/~cohousing/cuba/havad02.htm |archive-date=16 August 2009 }}</ref><ref>{{cite podcast |last1=Fenderson |first1=Adam |last2=Morgan |first2=Pamela |date=14 September 2006 |title=Interview with Pamela Morgan |url=http://www.radio4all.net/index.php/program/21578 |access-date=12 July 2014 |format=mp3 |time=3:09 |location=Melbourne, Australia |publisher=A-Infos Radio Project }}</ref> The Cuban government then sent teams throughout the country to train others.{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}} | |||

| Downtown Havana kiosks provided advice and resources for individual residents. Widespread ]s gave easy access to locally grown produce; less travel time required less energy use.<ref name=MontyDon80Mexico>]</ref> | |||

| ===Cuban culture=== | |||

| ], Cuba, in 2006]] | |||

| The ideological changes of the Special Period had effects on Cuban society and culture, beyond those on the country. A comprehensive review of these effects concerning ideology, art and popular culture can be found in ]'s ''Cuba in the Special Period''. As a result of increased travel and ], popular culture developed in new ways. ], in that volume, describes the circulation of ] between New York and Havana, and their mutual influences. ] has described the contemporary art networks that shaped the Cuban art market, and ] the channels through which ] accessed the wider Spanish-speaking world during that period. Elsewhere, ], ], Geoffrey Baker and ] extensively wrote about Cuban rap music as a result of these transnational exchanges.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Baker | first1 = Geoffrey | author-link = | title = ¡Hip hop, Revolución! Nationalizing Rap in Cuba | journal = Ethnomusicology | volume = 49 | issue = 3| page = 369 }}</ref> In recent years, that is, not in the 1990s which is the period identified with the Special Period, ] has replaced ] as the genre of choice among youth, taking on the explicitly sexual dance moves that originated with timba.<ref>]. "A Macho Sound for Black Sex." in ] and ], ''Globalization and Race'', Duke University Press. ]. "'Como hacer el amor con ropa' (As making love with your clothes on): Dancing regeton and hip-hop in Cuba." In ''Reading Reggaeton'' (forthcoming, Duke University Press), 2.</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.reggaeton-in-cuba.com/en/dance.htm|title=Dancing Reggaeton – Perreo – Dancing Perreo|website=www.reggaeton-in-cuba.com}}</ref> | |||

| Whereas timba music was a Cuban genre that evolved out of traditional song and jazz, emphasizing blackness and sexuality through sensual dancing, with lyrics that reflected the socio-cultural situation of the period with humor . ] evolved as a socially conscious movement influenced heavily by its kin genre American hip-hop. Thus it was not so much a product of the Special Period—as timba was—as one of globalization . The Revolution and the blockage of all imports from the US had made the dissemination of American music difficult during the sixties and seventies, as it was often "tainted as music of the enemy and began to disappear from the public view." But all of that changed in the 1990s, when American rappers flocked regularly to Cuba, tourists brought CDs, and North American stations, perfectly audible in Cuba, brought its sounds. Nonetheless, hip hop circulated through informal networks, thus creating a small underground scene of rap enthusiasts located mostly in Havana's Eastern neighborhoods that called the attention of foreign scholars and journalists. Eventually, rappers were offered a space within state cultural networks. The lack of resources to purchase the electronic equipment to produce beats and tracks gives Cuban rap a raw feel that paralleled that of "]" music in the US.<ref>Pacini-Hernandez, Deborah and ]''. "The emergence of rap Cubano: An historical perspective." In ''Music, Space, and Place'', editors Whitely, Bennett, and Hawkins, 89–107. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2004.</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 19:09, 6 June 2022

Economic crisis in Cuba after the fall of the Soviet UnionThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Special Period Periodo especial | |

|---|---|

Cuban citizens resorting to horse-drawn carriage for transportation (1994) Cuban citizens resorting to horse-drawn carriage for transportation (1994) | |

| Country | Cuba |

| Period | 1991–2000 |

| Refugees | Around 30,000 |

| Effect on demographics |

|

| Consequences |

|

In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed, resulting in a large-scale economic collapse throughout the newly independent states which once comprised it. During its existence, the Soviet Union provided Cuba with large amounts of oil, food, and machinery. In the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba's gross domestic product shrunk 35%, imports and exports both fell over 80%, and many domestic industries shrank considerably. Food and weapon imports stopped or severely slowed. The largest immediate impact was the loss of nearly all of the petroleum imports from the USSR; Cuba's oil imports dropped to 10% of pre-1990 amounts. Before this, Cuba had been re-exporting any Soviet petroleum it did not consume to other nations for profit, meaning that petroleum had been Cuba's orks. The lack of resources to purchase the electronic equipment to produce beats and tracks gives Cuban rap a raw feel that paralleled that of "old school" music in the US.

See also

- The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil

- Economy of Cuba

- Rationing in Cuba

- List of permaculture projects in Cuba

- Green anarchism in Cuba

- 1998 Russian financial crisis

- Lost Decade (Japan)

- Arduous March – the North Korean famine

References

- ^ Kozameh, Sara (30 January 2021). "How Cuba Survived and Surprised in a Post-Soviet World". Jacobin. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Garth, Hanna. 2009 Things Became Scarce: Food Availability and Accessibility in Santiago de Cuba Then and Now. NAPA Bulletin.

- Carmen Diana Deere (July–August 1991). "Cuba's struggle for self-sufficiency – aftermath of the collapse of Cuba's special economic relations with Eastern Europe". Monthly Review. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- "Cuba's Special Period". www.historyofcuba.com.

- Pacini-Hernandez, Deborah and Reebee Garofalo. "The emergence of rap Cubano: An historical perspective." In Music, Space, and Place, editors Whitely, Bennett, and Hawkins, 89–107. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2004.

Sources

- Chavez, L. (2005). Capitalism, God, and a Good Cigar; Cuba Enters the Twenty-First Century. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Chiddister, Diane. (27 April 2006). Film shows many ways Cuba reacted to peak oil crisis Yellow Springs News. Retrieved 12 July 2014 (originally retrieved 18 October 2006)

- Heinberg, R. (2003). The Party's Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies. Canada: New Societies Publishers

- Hernandez-Reguant, A., ed. (2009). Cuba in the Special Period. Culture and Ideology in the 1990s. New York: Palgrave -Mac Millan.

- Lopez, M. Vigil. (1999). Cuba; Neither Heaven Nor Hell. Washington, D.C.: The Ecumenical Program of Central America and the Caribbean (EPICA).

- Pineiro-Hall, E. (2003) Seattle Delegation US Women and Cuba@ 5th International Women's Conference, University of Havana.

- Sierra, J.A. Time Table of Cuba 1980–2005, Retrieved 12 December 2006

- Zuckerman, S. (2003). Lessons From Cuba: What Can We Learn From Cuba's Two-Tier Tourism Economy?, Retrieved 26 November 2006

External links

- Cuba: Life After Oil

- Journeyman Pictures documentary Cuba - Seeds in the City - 22 min 47 sec (27 June 2003)

- Adam Fenderson interviews Pamela Morgan as she recalls her experiences in Cuba circa 1996

- Template:Ecured

| Cuba articles | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

| ||||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||||

| Economy | |||||||||||

| Culture |

| ||||||||||

| Financial crises | |

|---|---|

| Pre-1000 |

|

| Commercial revolution (1000–1760) |

|

| 1st Industrial Revolution (1760–1840) |

|

| 1840–1870 | |

| 2nd Industrial Revolution (1870–1914) |

|

| Interwar period (1918–1939) |

|

| Wartime period (1939–1945) |

|

| Post–WWII expansion (1945–1973) |

|

| Great Inflation (1973–1982) |

|

| Great Moderation/ Great Regression (1982–2007) |

|

| Great Recession (2007–2009) |

|

| Information Age (2009–present) |

|