| Revision as of 21:24, 26 October 2024 editRemsense (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Template editors61,664 edits Undid revision 1253597866 by 98.115.183.34 (talk) MOS:HANZITags: Undo Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App undo← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:55, 8 November 2024 edit undoMin968 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,341 editsNo edit summaryTags: harv-error Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile editNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Emperor of China from 1402 to 1424}} | ||

| {{distinguish|Yongli Emperor}} | {{distinguish|Yongli Emperor}} | ||

| {{redirect|Zhu Di|the scientist|Zhu Di (scientist)|the footballer|Zhu Di (footballer)}} | {{redirect|Zhu Di|the scientist|Zhu Di (scientist)|the footballer|Zhu Di (footballer)}} | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2023}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2023}} | ||

| {{Infobox royalty | {{Infobox royalty | ||

| | name = Yongle Emperor<br />{{langn|zh|永樂帝}} | | name = Yongle Emperor <br /> {{langn|zh|永樂帝}} | ||

| | temple name = Taizong{{efn-lr|name=Hongxi}} ({{zhi|c=太宗}})<br>Chengzu{{efn-lr|name=Jiajing}} ({{zhi|c=成祖}}) (commonly known) | |||

| | temple name = {{plainlist| | |||

| *Taizong{{Efn|This temple name was conferred by the Hongxi Emperor.}} ({{lang|zh|太宗}}) | |||

| *Chengzu{{Efn|This temple name was changed by the Jiajing Emperor.}} ({{lang|zh|成祖}}) (commonly known)}} | |||

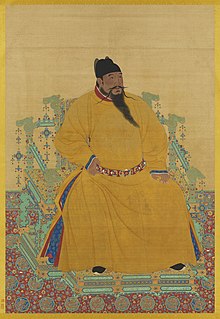

| | image = Portrait assis de l'empereur Ming Chengzu.jpg | | image = Portrait assis de l'empereur Ming Chengzu.jpg | ||

| | caption = Palace portrait on a ], kept in the ] |

| caption = Palace portrait on a ], kept in the ], ], ] | ||

| | succession = ] | | succession = ] | ||

| | reign = 17 July 1402 – 12 August 1424 | | reign = 17 July 1402 – 12 August 1424 | ||

| Line 20: | Line 18: | ||

| | reign1 = 2 May 1370 – 17 July 1402 | | reign1 = 2 May 1370 – 17 July 1402 | ||

| | reign-type1 = Tenure | | reign-type1 = Tenure | ||

| | predecessor1 = | |||

| | full name = Zhu Di ({{lang|zh|朱棣}}) | |||

| | successor1 = Himself as emperor | |||

| | era name = Yongle ({{lang|zh|永樂}}) | |||

| | full name = Zhu Di ({{zhi|c=朱棣}}) | |||

| | posthumous name = '''Emperor''' Titian Hongdao Gaoming Guangyun Shengwu Shengong Chunren Zhixiao '''Wen'''{{efn-lr|name=Hongxi|Conferred by the Hongxi Emperor}} ({{zhi|t=體天弘道高明廣運聖武神功純仁至孝'''文皇帝'''}})<br>'''Emperor''' Qitian Hongdao Gaoming Zhaoyun Shengwu Shengong Chunren Zhixiao '''Wen'''{{efn-lr|name=Jiajing|Changed by the ]}} ({{zhi|t=啓天弘道高明肇運聖武神功純仁至孝'''文皇帝'''}}) | |||

| | era name = Yongle ({{zhi|t=永樂}}) | |||

| | era dates = 23 January 1403 – 19 January 1425 | | era dates = 23 January 1403 – 19 January 1425 | ||

| | house = ] | | house = ] | ||

| Line 29: | Line 30: | ||

| | religion = ] | | religion = ] | ||

| | birth_date = 2 May 1360 | | birth_date = 2 May 1360 | ||

| | birth_place = ], ] (present-day ], China) | | birth_place = ], ] (present-day ], ], China) | ||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1424|8|12|1360|5|2|df=y}} | | death_date = {{Death date and age|1424|8|12|1360|5|2|df=y}} | ||

| | death_place = Yumuchuan, Ming dynasty (present-day ], Inner Mongolia, China) | | death_place = Yumuchuan, ] (present-day ], ], China) | ||

| | burial_date = 8 January 1425 | | burial_date = 8 January 1425 | ||

| | burial_place = |

| burial_place = Chang Mausoleum, ], ] | ||

| | spouse = {{Marriage|]|1376|1407|end=d}} | | spouse = {{Marriage|]|1376|1407|end=d}} | ||

| | issue |

| issue-link = #Family | ||

| | issue = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ], ] | * ], ] | ||

| * ], ] | * ], ] | ||

| * ] | * ]}} | ||

| |module={{Infobox Chinese | |||

| }} | |||

| |child= yes | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| | pic = Yongle Emperor (Chinese characters).svg | |||

| | piccap = "Yongle Emperor" in traditional (top) and simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||

| | picupright = 0.5 | |||

| | t = 永樂帝 | | t = 永樂帝 | ||

| | s = 永乐帝 | | s = 永乐帝 | ||

| | l = | |||

| | p = Yǒnglè Dì | | p = Yǒnglè Dì | ||

| | w = Yung<sup>3</sup>-le<sup>4</sup> Ti<sup>4</sup> | |||

| | w = {{tonesup|Yung3-le4 Ti4}} | |||

| | mi = {{IPAc-cmn|yong|3|l|e|4|-|d|i|4}} | | mi = {{IPAc-cmn|yong|3|l|e|4|-|d|i|4}} | ||

| | j = Wing<sup>5</sup>-lok<sup>6</sup> dai<sup>3</sup> | |||

| | j = Wing5-lok6 dai3 | |||

| | ci = {{IPAc-yue|w|ing|5|l|ok|6|-|d|ai|3}} | | ci = {{IPAc-yue|w|ing|5|l|ok|6|-|d|ai|3}} | ||

| | tl = Íng-lo̍k tē | | tl = Íng-lo̍k tē | ||

| }}}} | |||

| | altname = Personal name | |||

| | c2 = 朱棣 | |||

| | p2 = Zhū Dì | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Yongle Emperor''' (2 May 1360{{snd}}12 August 1424), personal name '''Zhu Di''', was the third ], reigning from 1402 to 1424. | |||

| The '''Yongle Emperor''' (2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), also known by his ] as the '''Emperor Chengzu of Ming''', personal name '''Zhu Di''', was the third ], reigning from 1402 to 1424. He was the fourth son of the ], the founder and first emperor of the dynasty. | |||

| Zhu Di was the fourth son of the ], the founder of the ]. He was originally ] as the ] in May 1370,<ref name="4chan">Chan Hok-lam. "". ''The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History''. Chinese University Press, 2007. {{ISBN|978-9629962395}}. Accessed 12 October 2012.</ref> with the capital of his princedom at Beiping (modern ]). Zhu Di was a capable commander against the Mongols. He initially accepted his father's appointment of his eldest brother ] and then Zhu Biao's son ] as ], but when Zhu Yunwen ascended the throne as the Jianwen Emperor and began executing and demoting his powerful uncles, Zhu Di found pretext for rising in rebellion against his nephew.<ref name="4chan"/> Assisted in large part by ]s mistreated by the Hongwu and Jianwen Emperors, who both favored the Confucian ]s,<ref name="EunuchPower!">Crawford, Robert B. "". ''T'oung Pao'', 2d Series, Vol. 49, Livr. 3 (1961), pp. 115–148. Accessed 9 October 2012.</ref> Zhu Di survived the initial attacks on his princedom and drove south to launch the ] against the Jianwen Emperor in ]. In 1402, he successfully overthrew his nephew and occupied the imperial capital, ], after which he was proclaimed emperor and adopted the ] "]", which means "perpetual happiness". | |||

| In 1370, he was granted the title of Prince of Yan. By 1380, he had relocated to ] and was responsible for protecting the northeastern borderlands. In the 1380s and 1390s, he proved himself to be a skilled military leader, gaining popularity among soldiers{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=64}} and achieving success as a statesman. | |||

| Eager to establish his own legitimacy, Zhu Di voided the Jianwen Emperor's reign and established a wide-ranging effort to destroy or falsify records concerning his childhood and rebellion.<ref name="4chan"/> This included a massive purge of the Confucian scholars in Nanjing<ref name="4chan"/> and grants of extraordinary extralegal authority to the eunuch secret police.<ref name="EunuchPower!"/> One favorite was ], who employed his authority to launch major ] into the South Pacific and Indian Oceans. The difficulties in Nanjing also led the Yongle Emperor to re-establish Beiping (present-day Beijing) as the new imperial capital. He repaired and reopened the ] and, between 1406 and 1420, directed the construction of the ]. He was also responsible for the ], considered one of the wonders of the world before its destruction by the ] in 1856. As part of his continuing attempt to control the Confucian scholar-bureaucrats, the Yongle Emperor also greatly expanded the ] in place of his father's use of personal recommendation and appointment. These scholars completed the monumental '']'' during his reign. | |||

| In 1399, he rebelled against his nephew, the ], and launched a civil war known as the ], or the campaign to clear away disorders. After three years of intense fighting, he emerged victorious and declared himself emperor in 1402. After ascending the throne, he adopted the ] Yongle, which means "perpetual happiness". | |||

| The Yongle Emperor died while personally leading a military campaign against the Mongols. He was buried in the Changling Mausoleum, the central and largest mausoleum of the ] located north of Beijing. | |||

| His reign is often referred to as the "second founding" of the Ming dynasty, as he made significant changes to his father's political policies.{{sfnp|Atwell|2002|p=84}} Upon ascending the throne, he faced the aftermath of a civil war that had devastated the rural areas of northern China and weakened the economy due to a lack of manpower. In order to stabilize and strengthen the economy, the emperor first had to suppress any resistance. He purged the state administration of supporters of the Jianwen Emperor as well as corrupt and disloyal officials. The government also took action against secret societies and bandits. To boost the economy, the emperor promoted food and textile production and utilized uncultivated land, particularly in the prosperous ] Delta region. | |||

| ==Youth== | |||

| The Yongle Emperor was born Zhu Di on 2 May 1360, the fourth son of the new leader of the ], ], who led these rebels to success and became the ], the first emperor of the Ming dynasty. According to surviving Ming historical records, Zhu Di's mother was the Hongwu Emperor's primary consort, ], the view Zhu Di himself maintained. It is rumoured that Zhu Di's mother was one of his father's concubines.<ref>Levathes, Louise. ''When China Ruled The Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne 1405–1433'', p. 59. Oxford Univ. Press (New York), 1994.</ref> | |||

| Additionally, he made the decision to elevate Beijing to the capital in 1403, reducing the significance of ]. The construction of the new capital, which took place from 1407 to 1420, employed hundreds of thousands of workers daily. At the heart of Beijing was the official Imperial City, with the ] serving as the palace residence for the emperor and his family.{{sfnp|Ebrey|1999|p=194}} The emperor also oversaw the reconstruction of the ], which was crucial for supplying the capital and the armies in the north. | |||

| Zhu Di grew up as a prince in a loving, caring environment.{{Citation needed|date=October 2012}} His father supplied nothing but the best education{{Citation needed|date=October 2012}} and, trusting them alone, reestablished the old feudal principalities for his many sons. Zhu Di was created ], a location important for being both the former capital of the ] and the frontline of battle against ], a successor state to the Yuan dynasty. When Zhu Di moved to ], the former ] of Yuan, he found a city that had been devastated by famine and disease, but he worked with his father's general ] {{ndash}} who was also his own father-in-law {{ndash}} to continue the pacification of the region. | |||

| The emperor was a strong supporter of both Confucianism and Buddhism. He supported the compilation of the massive '']'' by employing two thousand scholars. This encyclopedia surpassed all previous ones, including the '']'' from the 11th century. He also ordered the texts of the Neo-Confucians to be organized and used as textbooks for training future officials. ], held in a three-year cycle, produced qualified graduates who filled positions in the state apparatus. The emperor was known for his strict punishments for failures, but also for quickly promoting successful servants.{{sfnp|Tsai|1996|p=157}} While he, like his father, was not afraid to use violence against opponents when necessary, he differed from his father in his abandonment of frequent purges. As a result, ministers held their posts for longer periods of time, leading to a more professional and stable state administration. | |||

| The official Ming histories portray a Zhu Di who impressed his father with his energy, daring, and leadership amid numerous successes; nonetheless, the Ming dynasty suffered numerous reverses during his tenure and the great ] was won not by Zhu Di but by his brother's partisan ]. Similarly, when the Hongwu Emperor sent large forces to the north, they were not placed under Zhu Di's command. | |||

| However, it was not just officials who enjoyed the emperor's favor and support. He ruled the empire primarily "from horseback", traveling between the two capitals, similar to the Yuan emperors. He also frequently led military campaigns into Mongolia.{{sfnp|Chang|2007|pp=66–67}} However, this behavior was opposed by officials who felt threatened by the growing influence of eunuchs and military elites. These groups relied on imperial favor for their power.{{sfnp|Chang|2007|pp=66–67}} | |||

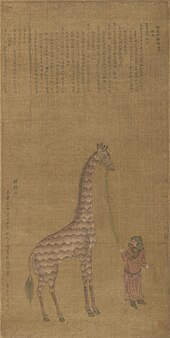

| The emperor also made significant efforts to strengthen and consolidate the empire's ] position in ] through foreign policy. Diplomatic messages and military expeditions were sent to "all four corners of the world". Missions were sent to countries near and far, including ], ], ], the ], and the ] in Central Asia. ] even reached the shores of ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| A major threat to the security of the empire was posed by the Mongols, who were divided into three groups—the ] in the southeast were mostly loyal, while the eastern Mongols and western ] were problematic. Ming China alternately supported and opposed them. The Yongle Emperor personally led five campaigns into Mongolia, and the decision to move the capital from Nanjing to Beijing was motivated by the need to keep a close eye on the restless northern neighbors. | |||

| The Yongle Emperor was a skilled military leader and placed great emphasis on the strength of his army. However, his wars were ultimately unsuccessful. ] (present-day northern ]), which began with an invasion in 1407, lasted until the end of his reign. Four years after his death, the Ming army was forced to retreat back to China. Despite his efforts, the ] did not significantly alter the balance of power or ensure the security of the northern border.{{sfnp|Lorge|2005|p=116}} | |||

| The Yongle Emperor died in 1424 and was buried in the Chang Mausoleum, the largest of the ] located near Beijing. | |||

| ==Early years== | |||

| ===Childhood=== | |||

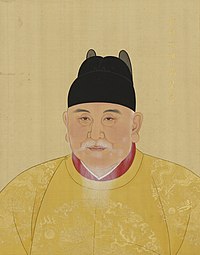

| {{Multiple image|image1=明太祖画像.jpg|image2=孝慈高皇后1.jpg|footer=] and ], Yongle's parents{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|pp=80–81}}}} | |||

| Zhu Di was born on 2 May 1360, as the fourth son of ].{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=20}} At the time, Zhu Yuanzhang was based in ] and was an independent general of the Song dynasty. This dynasty was one of the states formed during the ], which was a rebellion against the Mongol-led ] that controlled China. In the 1360s, Zhu Yuanzhang conquered China, established the ], and declared himself emperor. He is commonly known by his ] as the Hongwu Emperor. | |||

| After taking the throne, Zhu Di claimed to be the son of Zhu Yuanzhang's primary wife, ], who had been empress since 1368. However, other sources suggest that his real mother was a concubine of the Hongwu Emperor with the title Consort Gong, who was either Mongolian (from the ] tribe){{sfnp|Chan 2007|p=46}} or possibly Korean{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=194}}. After becoming emperor, Zhu Di attempted to present himself as the Hongwu Emperor's legitimate successor by declaring himself and his fifth son, ], as the only sons of Empress Ma in the 1403 edition of the official '']''. This was clearly absurd, as it was unlikely that a son of the empress would not be named as successor during the Hongwu Emperor's lifetime. Therefore, in the later version of 1418, all five of the Hongwu Emperor's sons were recognized as her descendants.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=216}} | |||

| Zhu Di spent his childhood in Nanjing, where he was raised with a strong emphasis on discipline and modesty, along with the other children of Zhu Yuanzhang. Out of all his siblings, he had a special fondness for Princess Ningguo ({{zhi|t=寧國公主}}), Zhu Fu ({{zhi|c=朱榑}}), and Zhu Su, who was only 15 months younger. Despite their contrasting personalities, Zhu Di and Zhu Su became the closest of friends. While Zhu Di enjoyed activities such as archery and horseback riding, Zhu Su preferred studying literature and tending to plants.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=23}} | |||

| The emperor took great care in the education of his sons, enlisting the help of prominent scholars from the empire. Initially, ] was appointed as the teacher for the crown prince, and also gave lectures to the other princes. Song Lian's successor, Kong Keren ({{zhi|c=孔克仁}}), had a significant influence on Zhu Di, teaching him philosophy and ethics. However, Zhu Di's favorite subject was the history of the ], particularly the emperors ] and ]. In fact, he often referenced examples from the life of ] in his decrees.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=25}} | |||

| ===Youth=== | |||

| On 22 April 1370, the emperor's sons, with the exception of the crown prince, were granted princely titles. Zhu Di was bestowed with the title of Prince of Yan.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=26}} Yan was a region located in the northeast of China, with its most significant city being Beiping (present-day ]). During the Mongol-led ], Beiping served as the capital of China. After being conquered by the Ming dynasty in 1368, it became a crucial stronghold for the troops guarding the northern border of China and was also designated as the capital of the province with the same name. | |||

| At that time, Zhu Di was given his own household, with adviser Hua Yunlong{{efn-lr|He held the second highest rank and served as the commissioner-in-chief of a military commission. For his participation in the campaign of 1370, he was appointed the Marquis of Huaian in June 1370. From February 1371, he governed the Beiping province; he was dismissed in 1374 and died on his way to Nanjing in the same year.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=27}}}} and tutor Gao Xian at its head. Gao Xian spent the next four to five years lecturing him on Confucian classics, history, agriculture, and irrigation. He also trained the prince in poetry and prose writing, and explained the rules of governance and the selection of subordinates. After Hua's death and Gao's dismissal, Fei Yu, Qiu Guang, Wang Wuban, and Zhu Fu took over Zhu Di's education.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=27}}{{efn-lr|Zhu Fu served under the prince from 1373 to 1388, becoming his chief tutor in 1377. He was diligent and honorable, and had a great influence on the prince, becoming his confidant. In 1416, Zhu Di posthumously awarded him the title of minister.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|pp=27–28}}}} Despite receiving a comprehensive education from esteemed teachers, Zhu Di's true passion always lay in military pursuits rather than scholarly pursuits and palace discussions. | |||

| ], ], Taiwan]] | |||

| In early 1376, he married ], the daughter of ], who was ranked first among all of the early Ming generals. She was two years younger than him.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=28}} Lady Xu was known for her intelligence, decisiveness, and energy. The couple welcomed their first son, ], on 16 August 1378, followed by their second son, ], in 1380.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=30}} Their third son, ], was born three years later. | |||

| A few weeks after the wedding, he traveled to ] (then known as Zhongdu—the Central Capital) where he underwent seven months of military training alongside his elder brothers, Zhu Shuang and Zhu Gang. Two years later, he returned to Fengyang with his younger brothers, Zhu Su, Zhu Zhen, and Zhu Fu, and stayed for an additional two years. During this time, he not only trained in command and combat, but also gained knowledge in logistics and the acquisition and transportation of materials and supplies for warfare. It was during this period that his organizational skills began to emerge, which he later utilized effectively in his battles. He also took the opportunity to disguise himself as a regular soldier and immerse himself in the lives of ordinary people. Looking back, he considered his time in Fengyang to be the happiest days of his life.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|pp=28–29}} | |||

| In 1376, Li Wenzhong, the nephew and adopted son of the Hongwu Emperor, who was responsible for defending the north, was given the responsibility of preparing the prince's palace in Beijing. He utilized the former palaces of the Yuan emperors, providing Zhu Di with a larger and more fortified residence compared to his brothers, some of whom resided in converted temples or county offices. General Li also focused on fortifying the city, a decision that would have consequences during the civil war when his son, ], unsuccessfully attempted to besiege Beiping in 1399.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=29}} | |||

| ===Prince of Yan in Beiping=== | |||

| In April 1380,{{sfnp|Chan|2005|p=59}} at the age of twenty, he moved to Beiping. He encountered a strong Mongolian influence, which the government tried to suppress by banning Mongolian customs, clothing, and names.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=33}} The city had recovered from the famine and wars of the 1350s and 1360s and was experiencing growth. Along with the hundreds of thousands of soldiers stationed in the region, the city was also home to officials administering the province, as well as artisans and laborers from all over the country. The main concern of the local authorities was providing enough food for the population. Peasants were relocated to the north, soldiers and convicts were sent to cultivate the land, and merchants were granted licenses to trade salt in exchange for bringing grain to the region.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=32}}{{efn-lr|Salt was then purchased from producers and sold to the population with a large profit.}} The government also transported food supplies to the city.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=33}} | |||

| Zhu Di's interest in the military was put into practice when he personally trained his own guard.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=33}} He used his detachments as a means of balancing the power of the provincial commander, who was unable to mobilize troops without authorization from the emperor and approval from the prince. Meanwhile, the prince had the freedom to train and deploy his own guard.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=46}}{{sfnp|Langlois|1988|p=177}} In 1381, Zhu Di had his first experience in the field when he joined Xu Da's campaign against the Mongols, led by Nayur Buqa.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=33}} | |||

| In the 1380s, Zhu Di served in border defense under the leadership of his father-in-law, Xu Da. After Su's death in 1385, ], Xu's deputy, took over leadership. In 1387, Zhu Di participated in a successful attack on the Mongols in Liaodong, led by ]. The following year, a Ming army led by ] made a foray into eastern Mongolia and defeated the Mongol khan ], capturing many prisoners and horses. However, both generals were accused of mistreating captives and misappropriating booty, which was reported to the emperor by the prince.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|pp=47–48}} | |||

| In January 1390, the emperor entrusted his sons with independent command for the first time. The princes of Jin (Zhu Gang), Yan (Zhu Di), and Qi (Zhu Fu) were given the task of leading a punitive expedition against the Mongol commanders Nayur Buqa and Alu Temür, who were threatening ] and ]. Zhu Di demonstrated excellent command skills when he defeated and captured both Mongol commanders in battle. They then served under him with their troops.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=48}} The emperor himself appreciated Zhu Di's success, which contrasted with the hesitancy of the Prince of Jin. Zhu Di continued to lead armies into battle against the Mongols repeatedly and with great success.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=49}} | |||

| [[File:Ming border princedoms, Hongwu Reign, after 1393.svg|thumb|left|upright=1.6|Northern border of the Ming dynasty after 1393. | |||

| {{Legend|#FFAAAA|Ming dynasty,}} | |||

| {{Legend|#ffd5d5|Ming territory beyond the Great Wall.}}]] | |||

| In 1392, the emperor's eldest son and crown prince, ], died. The court then discussed who would succeed him, and ultimately, the primogeniture viewpoint, advocated by scholars from the ] and high officials, prevailed. As a result, Zhu Biao's son, ], was appointed as the new successor. Generals Feng Sheng, Fu Youde, and Lan Yu (who were related to the successor by blood) were chosen as his tutors and teachers.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=50}} However, due to a recommendation from Zhu Di, the Hongwu Emperor began to suspect the three generals of treason.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=51}} It is worth noting that Zhu Di did not have a good relationship with Lan Yu, and according to historian Wang Shizhen ({{zhi|t=王世貞}}; 1526–1590), he was responsible for Lan Yu's execution in March 1393. The other two generals also died under unclear circumstances at the turn of 1394 and 1395. In their place, princes were appointed. For example, in 1393, the Prince of Jin was given command of all the troops in Shanxi province, and the Prince of Yan was given command in Beiping province.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=51}} Additionally, Zhu Shuang, Prince of Qin, was in charge of ], but he died in 1395.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=51–52}} | |||

| The Hongwu Emperor, who was deeply affected by the death of his two eldest sons and the strained relations between his remaining sons and the heir, made the decision to revise the rules governing the imperial family for the fourth time.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=52}} The new edition significantly limited the rights of the princes.{{efn-lr|The prince's right to visit his brothers after three or five years was lost. The government now appointed not only the highest but all officials of the princely households. The judicial authority of the princes was limited.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=52}} The maximum stipend for princes was reduced from 50,000 ''shi'' of grain to 10,000 in order to relieve the state treasury.{{sfnp|Langlois|1988|p=175}}}} However, these changes had little impact on Zhu Di's status as they did not affect his main area of expertise—the military.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=53}} Furthermore, the prince was cautious not to give any reason for criticism. For example, he did not object to the execution of his generals Nayur Buqa and Alu Temür, who were accused of treason. He also exercised caution in diplomatic relations, such as when he welcomed Korean delegations passing through Beiping, to avoid any indication of disrespect towards the emperor's authority.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=53}} | |||

| Out of the six princes{{efn-lr|They were, listed by age: Zhu Gang, Prince of Jin in ]; Zhu Di, Prince of Yan in Beiping; ], Prince of Dai in ]; ], Prince of Liao in Guangning; ], Prince of Ning in Daning; and Zhu Hui, Prince of Gu in ].}} responsible for guarding the northern border, Zhu Di was the second oldest but also the most capable. He had operated in a vast territory, stretching from Liaodong to the bend of the Yellow River. He was not afraid to take risks, as demonstrated by his defeat of the Mongols led by Polin Temür at Daning in the summer of 1396.{{sfnp|Langlois|1988|p=178}} He also went on a raid with the Prince of Jin several hundred kilometers north of the Great Wall, which earned them a sharp reprimand from the emperor.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=55}} In April 1398, Zhu Di's elder brother, the Prince of Jin, died, leaving Zhu Di as the undisputed leader of the northern border defense.{{sfnp|Langlois|1988|pp=178, 181}} Two months later, Zhu Di's father, the Hongwu Emperor, also died. | |||

| ==Rise to power== | ==Rise to power== | ||

| {{ |

{{Further|Jingnan campaign}} | ||

| ===Conflict with the Jianwen Emperor=== | |||

| ] that the Yongle Emperor ordered to be made for his father in 1405]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The ] was long-lived and outlived his first heir, ], Crown Prince Yiwen. He worried about his succession and issued a series of dynastic instructions for his family, the '']''. These instructions made it clear that the rule would pass only to children from the emperor's primary consort, excluding the Prince of Yan in favour of Zhu Yunwen, Zhu Biao's son.<ref name="4chan"/> When the Hongwu Emperor died on 24 June 1398, Zhu Yunwen succeeded his grandfather as the ]. In direct violation of the dynastic instructions, the Prince of Yan attempted to mourn his father in Nanjing, bringing a large armed guard with him. The imperial army was able to block him at ] and, given that three of his sons were serving as hostages in the capital, the prince withdrew in disgrace.<ref name="4chan"/> | |||

| After the death of the Hongwu Emperor, Zhu Yunwen ascended the throne as the Jianwen Emperor. His closest advisers immediately began reviewing the Hongwu Emperor's reforms, with the most significant change being an attempt to limit and eventually eliminate the princes who were the sons of the Hongwu Emperor and served as the emperor's support and controlled a significant portion of the military power during his reign. The government employed various methods to remove the five princes, including exile, house arrest, and even driving them to suicide.{{efn-lr|They were Zhu Su, Zhu Gui, Zhu Bo, Zhu Fu and Zhu Bian.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=61}}}} | |||

| Zhu Di was considered the most dangerous of all the princes.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=192}} He was an experienced military leader and the oldest surviving descendant of the Hongwu Emperor. Due to this, the government treated him with caution and limited his power. They replaced military commanders in the northeast with generals loyal to the Jianwen Emperor and transferred Zhu Di's personal guard outside of Beiping.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=62}} Despite this, Zhu Di managed to convince the emperor of his loyalty. He even asked for mercy for his friend Zhu Su{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=61}} and begged for permission to return his sons, who had been staying in Nanjing since the funeral of the Hongwu Emperor. This was done by the government as a precaution, effectively holding them as hostages.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=194}} However, in June 1399, the emperor's adviser, ], convinced the emperor that releasing Zhu Di's sons would help calm the situation.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=62}} Unfortunately, the result was the exact opposite. | |||

| The Jianwen Emperor's harsh campaign against his weaker uncles (dubbed {{lang|zh|削蕃}}, <small>lit.</small> "Weakening the Marcher Lords") made accommodation much more difficult, however: Zhu Di's full brother, ], Prince of Zhou, was arrested and exiled to Yunnan; ], Prince of Dai was reduced to a commoner; Zhu Bai, Prince of Xiang committed suicide under duress; Zhu Fu, Prince of Qi and Zhu Pian, Prince of Min were demoted all within the later half of 1398 and the first half of 1399. Faced with certain hostility, Zhu Di pretended to fall ill and then "went mad" for a number of months before achieving his aim of freeing his sons from captivity to visit him in the north in June 1399. On 5 August, Zhu Di declared that the Jianwen Emperor had fallen victim to "evil counselors" ({{lang|zh|奸臣}}) and that the Hongwu Emperor's dynastic instructions obliged him to rise in arms to remove them, a conflict known as the ].<ref name="4chan"/> | |||

| In early August 1399, Zhu Di used the arrest of two of his officials as a pretext for rebellion.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=195}} He claimed that he was rising up to protect the emperor from the corrupt court officials. With the support of Beijing dignitaries,{{efn-lr|Li Youzhi, Beiping surveillance commissioner, and Zhang Xin ({{zhi|t=張信}}), Beiping regional military commissioner.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=63}}}} he gained control of the city's garrison and occupied the surrounding prefectures and counties.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=63}} He attempted to justify his actions through letters sent to the court in August and December 1399, as well as through a public statement.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=195}} | |||

| In the first year, Zhu Di survived the initial assaults by superior forces under ] and ] thanks to superior tactics and capable Mongol auxiliaries. He also issued numerous justifications for his rebellion, including questionable claims to have been the son of Empress Ma and bold-faced lies that his father had attempted to name him as the rightful heir, only to be thwarted by bureaucrats scheming to empower Zhu Biao's son. Whether because of this propaganda or for personal motives, Zhu Di began to receive a steady stream of turncoat eunuchs and generals who provided him with invaluable intelligence allowing a hit-and-run campaign against the imperial supply depots along the ]. By 1402, he knew enough to be able to avoid the main hosts of the imperial army while sacking ], ], and ]. The betrayal of Chen Xuan gave him the imperial army's Yangtze River fleet; the betrayal of Li Jinglong and the prince's half-brother Zhu Hui, Prince of Gu opened the gates of Nanjing on 13 July. Amid the disorder, the imperial palace quickly caught fire: Zhu Di enabled his own succession by claiming three bodies {{ndash}} charred beyond recognition {{ndash}} as the Jianwen Emperor, his consort, and their son but rumours circulated for decades that the Jianwen Emperor had escaped in disguise as a Buddhist monk.<ref name="4chan"/><ref>Lü Bi ({{lang|zh|吕毖}}). ''A Short History of the Ming Dynasty'' ({{lang|zh|《明朝小史》}}), Vol. 3. {{in lang|zh}}</ref><ref>Gu Yingtai ({{lang|zh|谷應泰}}). ''Major Events in Ming History'' ({{lang|zh|《明史紀事本末》}}), Vol. 16. {{in lang|zh}}</ref> | |||

| In his letters and statements, he repeatedly asserted that he had no desire for the throne. However, as the eldest living son of the deceased emperor, he felt a duty to restore the laws and order that had been dismantled by the new government. He explained that this was out of respect for his late father. He also accused the current emperor and his advisors of withholding information about his father's illness and preventing him from attending the funeral. Furthermore, he condemned their unjust treatment of the emperor's uncles, who were his own younger brothers. He justified his actions as necessary self-defense, not against the emperor himself, but against his corrupt ministers. He referred to these actions as the ], a campaign to clear away disorders.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=195}} | |||

| Having captured the capital, Zhu Di now left aside his former arguments about rescuing his nephew from evil counsel and voided the Jianwen Emperor's entire reign, taking 1402 as the 35th year of the Hongwu era.<ref name="4chan"/> His own brother Zhu Biao, whom the Jianwen Emperor had posthumously elevated to emperor, was now posthumously demoted; Zhu Biao's surviving two sons were demoted to commoners and placed under house arrest; and the Jianwen Emperor's surviving younger son was imprisoned and hidden for the next 55 years. After a brief show of humility where he repeatedly refused offers to take the throne, Zhu Di accepted and proclaimed that the next year would be the first year of the Yongle era. On 17 July 1402, after a brief visit to his father's tomb, Zhu Di was crowned{{Clarify|date=October 2012}} emperor of the Ming dynasty at the age of 42. He would spend most of his early years suppressing rumours and outlaws. | |||

| ===Civil war=== | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| ] | |||

| | perrow = 3 | |||

| At the start of the war, Zhu Di commanded a force of 100,000 soldiers and only held control over the immediate area surrounding Beiping. Despite the Nanjing government's larger number of armies and greater material resources, Zhu Di's soldiers were of higher quality and he possessed a strong Mongol cavalry. Most importantly, his military leadership skills were superior to the indecisiveness and lack of coordination displayed by the government's generals.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=196}} | |||

| | total_width = 400 | |||

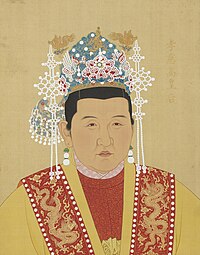

| | image1 = 太宗文皇帝.jpg | |||

| In September 1399, a government army of 130,000 soldiers, led by the experienced veteran general ], marched towards ], a city located southwest of Beiping. However, by the end of the month, they were defeated. In response, the court appointed a new commander, ], who then led a new army to besiege Beiping on 12 November.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=196}} Zhu Di, who had been gathering troops in the northeast, swiftly returned and defeated the surprised Li army. The soldiers from the south, who were not accustomed to the cold weather, were forced to retreat to ] in Shandong.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=198}} | |||

| | image2 = 仁孝文皇后徐氏(明太宗(成祖)).jpg | |||

| | footer = Portraits of Emperor Yongle and Empress Renxiaowen | |||

| In 1400, there were battles in the southern part of Beiping province and northwestern ], with varying levels of success. In the spring, Zhu Di led a successful attack into ], defeating Li Jinglong near ] in May and outside Dezhou in June. However, due to concerns about potential enemy reinforcements, Zhu Di ended the siege of ] in September and retreated to Beiping. Li Jinglong's lackluster performance led the government to appoint Sheng Yong as the new commander of the counterinsurgency army.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=198}} | |||

| | align = center | |||

| In 1401, Zhu Di attempted to weaken the enemy by attacking smaller units, which disrupted the supply of government troops. Both sides then focused on breaking through along the ]. In January, Zhu Di suffered a defeat at Dongchang, but in April he was victorious at Jia River. The front continued to move back and forth for the rest of the year.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=199}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1402, instead of launching another attack along the Grand Canal, Zhu Di advanced further west and bypassed Dezhou. He then conquered ] in early March. The government troops retreated south to ] and were repeatedly defeated. In July, the rebels reached the north bank of the ]. The commander of the government fleet defected to Zhu Di's side, allowing the rebel army to cross the river without resistance and advance on Nanjing.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=200}} Due to the betrayal of Li Jinglong and Zhu Hui, Zhu Di's younger brother, the capital city was captured on 13 July 1402, with little resistance. During the clashes, the palace was set on fire, resulting in the deaths of the emperor, his empress, and his son.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=201}} | |||

| ===Accession to the throne=== | |||

| On 17 July 1402, Zhu Di ascended the throne, officially succeeding his father, the Hongwu Emperor. However, even as late as the summer of 1402, the new emperor was still dealing with the followers of the Jianwen Emperor. These followers denied the legitimacy of Zhu Di's rule and he responded by erasing the Jianwen Emperor's reign from history. This included abolishing the Jianwen era and extending the Hongwu era until the end of 1402.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=201}} In addition, Zhu Di abolished the reforms and laws implemented by the Jianwen government, restored the titles and privileges of the princes, and destroyed government archives (with the exception of financial and military records).{{sfnp|Chan|2007|p=94}} He also attempted to involve respected supporters of the Jianwen Emperor, such as ] and Liu Jing ({{zhi|t=劉璟}}), in his administration. However, they refused and were subsequently executed.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=71}} Similarly, Huang Zicheng and ] were executed, along with their family members, teachers, students, and followers. Many others were imprisoned or deported to the border, resulting in a purge that affected tens of thousands of people.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|pp=201–202}} | |||

| After Zhu Di ascended to the imperial throne, the '']'' were rewritten. The original version, created in 1402 at the court of the Jianwen Emperor, was deemed unacceptable by the new regime. In late 1402, the authors of the original version began to revise their work, completing it in July 1403. However, the emperor was dissatisfied with the revised version and in 1411, he ordered a new version to be prepared. This new version was completed in June 1418, and changes focused primarily on Zhu Di's claim to the throne. It included claims that he was the son of Empress Ma, that the Hongwu Emperor had considered appointing him as successor, that he was to be the regent of the Jianwen Emperor, and that he was an exceptionally talented military leader who was highly favored by his father.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=217}} | |||

| ==Administration== | |||

| ] | |||

| In contrast to the frequent changes in offices during the Hongwu Emperor's reign, the high levels of the Yongle Emperor's administration remained stable.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|pp=211–212}} While the emperor did occasionally imprison a minister, the mass purges seen in the Hongwu era did not occur again. The most significant political matters were overseen by eunuchs and generals, while officials were responsible for managing finances, the judiciary, and routine tasks. As a result, the atomization of administration that was characteristic of the Hongwu Emperor's rule diminished, allowing the emperor to focus less on routine details.{{sfnp|Dreyer|1982|p=}} | |||

| The political influence of the bureaucratic apparatus gradually increased, and under the Yongle Emperor's rule, ministers were able to challenge the emperor, even at the cost of their freedom or lives. The most significant change was the emergence of the ], which played a crucial role in the politics of the Yongle Emperor's successors. Led by the Grand Secretaries, officials gained control of the government.{{sfnp|Dreyer|1982|pp=213–214}} | |||

| ===Princes and generals=== | |||

| The emperor restored the titles of the princes of Zhou, Qi, and Min, which had been abolished by the Jianwen Emperor. However, these titles did not come with the same power and authority as before.{{sfnp|Tsai|202|p=76}} During the latter half of his reign, the Yongle Emperor accused many of these princes of committing crimes and punished them by removing their personal guards. Interestingly, he had previously condemned the same actions when they were carried out by the Jianwen Emperor.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=245}} In order to reduce political threats, the Yongle Emperor relocated several border princes from the north to central and southern China.{{efn-lr|For example, Zhu Hui, Prince of Gu, was relocated from Xuanfu to ], while Zhu Quan, Prince of Ning, was moved from Daning to ].{{sfnp|Tsai|202|p=76}}}} By the end of his reign, the princes had lost much of their political influence.{{sfnp|Tsai|202|p=76}} | |||

| One of the Yongle Emperor's first actions upon assuming the throne was to reorganize the military command. He promoted loyal generals and granted them titles and ranks. In October 1402, he appointed two dukes (''gong''; {{zhi|c=公}})—] and Zhu Neng ({{zhi|c=朱能}}), thirteen marquises (''hou''; {{zhi|c=侯}}), and nine counts (''bo''; {{zhi|c=伯}}). Among these appointments were one duke and three counts from the dignitaries who had defected to his side before the fall of Nanjing—Li Jinglong, Chen Xuan ({{zhi|t=陳瑄}}), Ru Chang ({{zhi|c=茹瑺}}), and Wang Zuo ({{zhi|c=王佐}}). In June 1403, an additional nine generals from the civil war were appointed as marquises or counts. In the following years, meritorious military leaders from the campaign against the Mongols were also granted titles of dukes, marquises, and counts, including those of Mongolian origin.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=206}} | |||

| The emperor established a new hereditary military nobility. While their income from the state treasury (2200–2500 ''shi'' of grain for dukes, 1500–800 for marquises, and 1000 for counts; with 1 ''shi'' being equivalent to 107 liters) was not particularly high, the prestige associated with their titles was more significant. They commanded armies in the emperor's name, without competition from the princes who had been stripped of their influence. The nobility also held immunity from punishment by local authorities. However, there were notable differences from the Hongwu era. During that time, the generals, who were former comrades-in-arms of the emperor, held a higher status, had their own followers, and wielded considerable power in their assigned areas. This eventually posed a threat to the emperor, leading to their elimination. Under the Yongle Emperor, members of the nobility did not participate in regional or civil administration, nor were they assigned permanent military units. Instead, they were given ''ad hoc'' assembled armies. Additionally, the emperor often personally led campaigns accompanied by the nobility, strengthening their personal relationships.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=207}} As a result, the military nobility was closely tied to the emperor and remained loyal. There was no need for purges, and any isolated cases of punishment were due to the failures and shortcomings of those involved. Overall, the nobility elevated the emperor's prestige and contributed to the military successes of his reign.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=208}} | |||

| ===Officials and authorities=== | |||

| {{Quote box | |||

| |text = Grand Secretaries during the reign of the Yongle Emperor, from 1402–1424. The first two were appointed in August 1402, while the rest were appointed a month later. | |||

| * ], to 1414 (imprisoned); | |||

| * ], to 1407 (transferred to Guangxi province); | |||

| * ], to 1418 (died in office); | |||

| * ], to 1440 (died in office); | |||

| * ], to 1444 (died in office); | |||

| * ], to 1431 (died in office); | |||

| * ], to 1404 (transferred to the head of the ]). | |||

| At the head of the Grand Secretariat stood briefly in 1402 Huang Huai, followed by Xie Jin, and from 1407 by Hu Guang until his death in 1418, when Yang Rong took over until the end of the Yongle Emperor's reign. | |||

| |width = 40% | |||

| |border = none | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The emperor reorganized the civilian administration, gaining the support of officials who had often served under the previous government. He restored the administrative structure of the Hongwu era, while also making some changes. First and foremost, in 1402, the Grand Secretariat was created to act as an intermediary between the emperor and the government, partially replacing the ] that had been abolished in 1380. Despite their informal position, the Grand Secretaries quickly gained dominance in the civil administration.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=208}} | |||

| ==Becoming the emperor== | |||

| With many ]s in Nanjing refusing to recognise the legitimacy of his claim to the throne, the Yongle Emperor began a thorough purge of them and their families, including women and children. Other supporters of the Jianwen Emperor's regime were extirpated throughout the country, while a reign of terror was seen due to eunuchs settling scores with the two prior administrations.<ref name="EunuchPower!"/> | |||

| The Grand Secretariat was established in August 1402, when the emperor began to address current administrative issues during a working dinner with Huang Huai and Xie Jin after the evening audience. In September 1402, he appointed five additional Grand Secretaries.{{sfnp|Tsai|202|p=95}} These Grand Secretaries were all from the south or southeast{{efn-lr|Huang Huai was from ], Yang Rong from ], and the remaining officials from ]. Jiangxi was known for its high level of education, with sixteen out of the top thirty students in the palace examinations of 1400 coming from this province. However, many officials from Jiangxi, particularly Huang Zicheng, were associated with the Jianwen government and responsible for the civil war. After 1402, they refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Yongle Emperor. In an attempt to appease this resistance, the emperor welcomed local elites into his court, but the young Hanlin scholars remained steadfast in their loyalty.{{sfnp|Tsai|202|p=97}}}} and were highly educated and skilled in administration, having previously served in lower positions in the Jianwen Emperor administration. Despite their relatively low status (at most fifth rank), they were given high titles in the crown prince's household. Over time, they evolved from subordinate assistants responsible for organizing correspondence and formulating responses to becoming influential politicians who proposed solutions to problems. Their close proximity to the emperor gave them an advantage over the ministers. The emperor kept his Grand Secretaries with him, and some even accompanied him on his Mongol campaigns. During this period, the empire was governed by the crown prince with the assistance of other Grand Secretaries and selected ministers.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=209}} The crown prince developed a close relationship with the Grand Secretaries and became the ''de facto'' representative of the officials.{{sfnp|Dreyer|1982|pp=213–214}} | |||

| The Yongle Emperor was meticulous in his selection of thr top officials for the state apparatus, including the members of the Grand Secretariat and the ministers. He placed particular trust in those who had served him during the civil war, such as Jin Zhong ({{zhi|c=金忠}}), Guo Zi, Lü Zhen ({{zhi|t=呂震}}), and Wu Zhong ({{zhi|t=吳中}}).{{sfnp|Tsai|202|p=93}} These ministers came from all over China, but were all highly educated and capable administrators. Among them, Minister of Revenue ] was the most trusted by the emperor. Xia advocated for moderation in spending and using resources for the benefit of the population, which earned him the respect of the Yongle Emperor for his honesty and transparency.{{sfnp|Tsai|202|p=94}} Xia held this position for nineteen years until 1421, when he, along with Minister of Justice Wu Zhong and Minister of War Fang Bin, protested against the costly campaign into Mongolia. Despite their objections, the emperor ultimately prevailed and Fang Bin committed suicide, while Wu Zhong and Xia Yuanji were imprisoned. However, after the Yongle Emperor's death, they were exonerated and returned to their positions of authority.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=211}} Other notable ministers who served for many years included Jian Yi ({{zhi|t=蹇義}}), Song Li ({{zhi|t=宋禮}}), Liu Quan ({{zhi|t=劉觀}}), and Zhao Hong, who held various ministerial positions. | |||

| During most of the Yongle Emperor's reign, four out of the six ministries (], ], ], and ]) were headed by the same minister. This continuity of leadership continued even after the emperor's death, with many ministers remaining in their positions.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=211}} | |||

| The regular cycle of ] also contributed to the improvement and stabilization of administration at lower levels. In the second decade of the Yongle Emperor's reign, the examinations were held every three years.{{sfnp|Dreyer|1982|pp=213–214}} A total of 1,833 individuals passed the examinations in the capital,{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=212}} and the majority of these graduates were appointed to government positions. ], which was previously responsible for selecting officials, lost its significance and became a place for candidates to study for the palace examinations.{{sfnp|Wang|2011|p=103}} By the end of the Yongle Emperor's reign, the Ministry of Personnel had a sufficient number of examination graduates to fill important positions at the county level and above. Overall, the administration became more qualified and stable.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=212}} | |||

| ===Eunuchs=== | |||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| The Yongle Emperor relied heavily on eunuchs, more so than his father did. He even recruited eunuchs from the Jianwen era, with whom he had been associated during the civil war. These eunuchs came from various backgrounds, including Mongolian, Central Asian, Jurchen, and Korean. In addition to their duties within the ], the Yongle Emperor trusted their unwavering loyalty and often assigned them tasks outside the palace's walls, such as surveillance and intelligence gathering.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=212}} | |||

| Chinese law had long allowed for the ] along with principals: The '']'' records insubordinate officers being threatened with it as far back as the ]. The ] had fully restored the practice, punishing rebels and traitors with ] as well as the death of their grandparents, parents, uncles and aunts, siblings by birth or ], children, nephews and nieces, grandchildren, and all cohabitants of whatever family,<ref>Chinamonitor.org. " ({{lang|zh|《中国死刑观察{{snd}}明初酷刑》}}). {{in lang|zh}}</ref><ref>Ni Zhengmao ({{lang|zh|倪正茂}}). '''' ({{lang|zh|比较法学探析}}). China Legal Publishing ({{lang|zh|中国法制出版社}}), 2006.</ref> although children were sometimes spared and women were sometimes permitted to choose slavery instead. Four of the purged scholars became known as the Four Martyrs, the most famous of whom was ], the former tutor to the Jianwen Emperor: threatened with execution of all nine degrees of his kinship, he fatuously replied "Never mind nine! Go with ten!" and {{ndash}} alone in Chinese history {{ndash}} he was sentenced to execution of 10 degrees of kinship: along with his entire family, every former student or peer of Fang Xiaoru that the Yongle Emperor's agents could find was also killed. It was said that as he died, cut in half at the waist, Fang used his own blood to write the character {{lang|zh|篡}} ("usurper") on the floor and that 872 other people were executed in the ordeal. | |||

| Eunuchs also held positions of military command and led diplomatic missions. However, their role as the emperor's secret agents, responsible for monitoring both civilian and military officials, was well-known but also unpopular and feared. While they were known for exposing corrupt officials, they also had a reputation for abusing their power and succumbing to corruption themselves. In 1420, a special investigation office was established, informally known as the "]" due to its location in the palace. This office was responsible for overseeing the judiciary, but it became infamous for its role in the disappearance of individuals. Stories of innocent imprisonment, torture, and unexplained deaths involving the office circulated until the end of the dynasty.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=213}} | |||

| The Yongle Emperor followed traditional rituals closely and held many popular beliefs. He did not overindulge in the luxuries of palace life, but still used ] and Buddhist festivals to help calm civil unrest. He stopped the warring between the various Chinese tribes and reorganised the provinces to best provide peace within the Ming Empire. The Yongle Emperor was said to be an "ardent Buddhist" by Ernst Faber.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sEYPAAAAYAAJ&q=ardent+buddhist+reaching|title=Chronological handbook of the history of China: a manuscript left by the late Rev. Ernst Faber|author=Ernst Faber|year=1902|publisher=Pub. by the General Evangelical Protestant missionary society of Germany|page=196|access-date=6 June 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ===Succession disputes=== | |||

| Due to the stress and overwhelming amount of thinking involved in running a post-rebellion empire, the Yongle Emperor searched for scholars to serve in his government. He had many of the best scholars chosen as candidates and took great care in choosing them, even creating terms by which he hired people. He was also concerned about the degeneration of Buddhism in China. | |||

| The Yongle Emperor had four sons, the first three by Empress Xu, while the fourth, Zhu Gaoxi, died in infancy. The eldest son, ], was not physically fit and instead of warfare, he focused on literature and poetry. The second son, ], was a tall and strong, a successful warrior. However, the third son, ], was mediocre in character and ability.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=98}} | |||

| Many influential officials, including General Qiu Fu, convinced the emperor that the second son should be the crown prince. They argued for his prowess and military skills, citing his past actions of saving his father from danger and turning the tide of battles during the civil war. However, Grand Secretary Xie Jin disagreed and argued that the eldest son would win the hearts of the people with his humanity. He also reminded the emperor of the future accession of ], the emperor's favorite grandson and Zhu Gaochi's eldest son. Ultimately, on 9 May 1404, Zhu Gaochi was appointed as the crown prince, with the Yongle Emperor appointing Qiu Fu as his tutor the following day.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=98}} | |||

| ==Reign== | |||

| ] is disputed]] | |||

| At the same time, he appointed Zhu Gaoxu as the Prince of Han and entrusted him with control of ]. Zhu Gaosui became the Prince of Zhao, based in Beijing. However, Zhu Gaoxu refused to go to Yunnan. His father gave in to his wishes, which allowed him to provoke conflicts with his older brother. In the spring of 1407, he succeeded in slandering Xie Jin, who was accused of showing favoritism towards ] natives in the examinations. As a result, Xie Jin was transferred to the province and later imprisoned.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=99}} Huang Huai (from 1414 until the end of the Yongle Emperor's reign) and Yang Shiqi (briefly in 1414), both accused of not observing the ceremony, also faced imprisonment due to their support of the crown prince and resulting enmity with Zhu Gaoxu. In 1416, Zhu Gaoxu was given a new fief in ] Prefecture in Shandong. Once again, he refused to leave, which led to a reprimand from his father. He then began to raise his own army and even had an army officer killed. As a result, his father stripped him of his titles, demoted him to a common subject, and later imprisoned him. The following year, he was deported to Shandong.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=100}} | |||

| ===Relations with Tibet=== | |||

| In 1403, the Yongle Emperor ] inviting ], the fifth ] of the ] school of ], to visit the imperial capital – apparently after having a vision of the ] ]. After a very long journey, Deshin Shekpa arrived in ] on 10 April 1407 riding on an elephant towards the imperial palace, where tens of thousands of monks greeted him.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| ==Military== | |||

| Deshin Shekpa convinced the Yongle Emperor that there were different religions for different people, which does not mean that one is better than the others. The Karmapa was very well received during his visit and a number of miraculous occurrences were reported. He also performed ceremonies for the imperial family. The emperor presented him with 700 measures of silver objects and bestowed the title of 'Precious Religious King, Great Loving One of the West, Mighty Buddha of Peace'.<ref>Brown, 34.</ref> A khatvanga in the ] was one of the objects given to the Karmapa by the Yongle Emperor.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/20263001|title = Use this image 20263001 | British Museum}}</ref> | |||

| ], Beijing]] | |||

| During the Yongle Emperor's reign, the military underwent significant changes. He implemented four major reforms, including the abolition of the princely guards (''huwei''; {{zhi|t=護衛}}), the relocation of the majority of the capital guards (''jingwei''; {{zhi|t=京衛}}) from Nanjing to Beijing, the establishment of the capital training camps (''jingying''; {{zhi|t=京營}}), and the reorganization of the defenses along the northern border.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=244}} | |||

| The emperor reorganized the ] (''Jinyiwei''), which was responsible for carrying out secret police duties. Its main focus was handling politically sensitive cases, such as investigating members of the imperial family. However, there were instances of corruption and abuse of power within the organization, most notably the case of Ji Gang ({{zhi|t=紀綱}}). Ji Gang, who had been the emperor's favorite during the civil war, was eventually accused of plotting against the throne and executed in 1416. By 1420, the Embroidered Uniform Guard had been overshadowed by the Eastern Depot, which also conducted investigations on its officers.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=213}} | |||

| Aside from the religious matter, the Yongle Emperor wished to establish an alliance with the Karmapa similar to the one the 13th- and 14th-century ] khans had established with the ].<ref>Sperling, 283–284.</ref> He apparently offered to send armies to unify Tibet under the Karmapa but Deshin Shekpa demurred, as parts of Tibet were still firmly controlled by partisans of the former Yuan dynasty.<ref>Brown, 33–34.</ref> | |||

| The abolition of the princes' armies was a logical decision. Zhu Di's military strength as the Prince of Yan played a crucial role in his rise to the throne, and he was determined to prevent history from repeating itself. The existing princely guards were mostly integrated into the regular army, and although the Yongle Emperor's sons had played an active and successful role in the civil war, they were not given command of the armies after it ended. Instead, campaigns were led by dependable generals or the emperor himself.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=245}} | |||

| Deshin Shekpa left Nanjing on 17 May 1408.<ref>Sperling, 284.</ref> In 1410, he returned to ] where he had his monastery rebuilt following severe damage from an earthquake. After the Karmapa's visit, Yongle styled himself a ]. A large amount of Tibetan Buddhist art was created in imperial workshops to demonstrate his authority and right to govern.<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1352/rubin-museums-faith-and-empire-tibetan-buddhist-ar/ | title = Rubin Museum's Faith and Empire: Tibetan Buddhist Art | access-date = September 27, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| One significant and permanent step taken during this time was the relocation of a large portion of the army to the Beijing area. As the capital moved to Beijing, the majority of the 41 guard units of the Nanjing garrison also made the move.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=245}} Among the troops stationed in Beijing were 22 guard units of the Imperial Guard (''qinjun''; {{zhi|t=親軍}}), totaling 190,800 men.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=246}} This included the original three guard units of Zhu Di's princely guard.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=245}} Overall, approximately 25–30% of the Ming army (74 guard units in the mid-1430s) was now concentrated in and around Beijing, with a total strength of over two million men under the Yongle Emperor's reign.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=247}} As a result, soldiers and their families made up a significant portion of the population in the Beijing area.{{efn-lr|In 1393, Beiping province had a population of 1,926,595 inhabitants.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=247}}}} To oversee the remaining guard units in and around Nanjing, a military commander position was established, often filled by eunuchs.{{sfnp|Dreyer|1982|p=203}} | |||

| ===Selecting an heir=== | |||

| When it was time for him to choose an heir, the Yongle Emperor wanted to choose his second son, ], Prince of Han. Zhu Gaoxu had an athletic-warrior personality which contrasted sharply with his elder brother's intellectual and humanitarian nature. Despite much counsel from his advisers, the Yongle Emperor chose his older son, Zhu Gaozhi (the future ]), as his heir apparent mainly due to advice from ]. As a result, Zhu Gaoxu became infuriated and refused to give up jockeying for his father's favour and refusing to move to ], where his princedom was located. He even went so far as to undermine Xie Jin's counsel and eventually killed him. | |||

| After the second campaign in Mongolia, the emperor made the decision to enhance the training of his soldiers. He established the capital training camps, known as the Three Great Camps (''Sandaying''), in the vicinity of Beijing. In 1415, he issued a decree requiring all guards in the northern provinces and the southern metropolitan area to send a portion of their troops to these camps for training. The camps were specifically designed for the training of infantry, cavalry, and units equipped with firearms. Each camp was under the leadership of a eunuch and two generals.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=247}} The emperor placed great emphasis on the importance of cavalry in successful combat in the steppe. As a result, the number of horses in the army significantly increased from 37,993 in 1403 to 1,585,322 in 1423.{{sfnp|Wang|2011|p=110}} | |||

| ===National economy and construction projects=== | |||

| After the Yongle Emperor's overthrow of the ], China's countryside was devastated. The fragile new economy had to deal with low production and depopulation. The Yongle Emperor laid out a long and extensive plan to strengthen and stabilise the new economy, but first he had to silence dissension. He created an elaborate system of censors to remove corrupt officials from office that spread such rumors. The emperor dispatched some of his most trusted officers to reveal or destroy secret societies, bandits, and loyalists to his other relatives. To strengthen the economy, he fought population decline, using the most he could from the existing labour force, and maximising textile and agricultural production. | |||

| At the beginning of the Yongle Emperor's reign, the defense system on the northern border was reorganized. Under the Hongwu Emperor, the defense of the north was organized in two lines. The first, the outer line, consisted of eight garrisons located in the steppe north of the ]. These garrisons served as bases for forays into Mongolian territory. The second line of defense was along the Great Wall.{{sfnp|Wang|2011|p=116}} However, at the time, the Great Wall had not yet been built. This strategic placement allowed for the prevention of Mongol raids even in the steppe. Under the Yongle Emperor's reign, the outer line was abandoned{{efn-lr|Chan Hok-lam in ''The Cambridge History of China Volume 7'' states that the withdrawal occurred due to financial reasons,{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=248}} while Wang Yuan-Kang in ''Harmony and War: Confucian Culture and Chinese Power Politics'' writes about the "withdrawal for unclear reasons".{{sfnp|Wang|2011|p=116}}}} with the exception of the garrison in ].{{efn-lr|The isolated Kaiping was difficult to defend, leading to its abandonment by the Ming army in 1430.{{sfnp|Wang|2011|p=116}}}} The emperor then resettled friendly Mongolian Uriankhai on the vacated territory. | |||

| The Yongle Emperor also worked to reclaim production rich regions such as the Lower ] and called for a massive reconstruction of the ]. During his reign, the Grand Canal was almost completely rebuilt and was eventually moving imported goods from all over the world. The Yongle Emperor's short-term goal was to revitalise northern urban centres, especially his new capital at Beijing. Before the Grand Canal was rebuilt, grain was transferred to Beijing in two ways; one route was simply via the ], from the port of ] (near ]); the other was a far more laborious process of transferring the grain from large to small shallow barges (after passing the ] and having to cross southwestern ]), then transferred back to large river barges on the ] before finally reaching Beijing.<ref name="brook 46 47">Brook, 46–47.</ref> With the necessary tribute ] of four million ''shi'' (one ''shi'' equal to 107 ]s) to the north each year, both processes became incredibly inefficient.<ref name="brook 46 47"/> It was a magistrate of ] who sent a memorandum to the Yongle Emperor protesting the current method of grain shipment, a request that the emperor ultimately granted.<ref>Brook, 47.</ref> | |||

| The border troops along the northern borders were placed under the authority of nine newly established border regional commands.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=248}} These commands were under the control of provincial military commanders (''zongbing guan''; {{zhi|t=總兵官}}) and were located in ], ], ], ], Shanxi, Yansui, Guyuan (in Shaanxi), Ningxia, and Gansu. Unlike in the Hongwu era, the soldiers stationed on the border were not from nearby guards, but were instead from the three capital training camps. The commanders of these areas were chosen from officers of the inland garrisons or higher commands.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=249}}{{efn-lr|Later, during the reign of the Xuande Emperor, these commands became more stable and evolved from a temporary structure into a regular part of the army, becoming more professional than the typical inland units.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=249}}}} By the end of the Yongle era, there were 863,000 soldiers stationed in garrisons along the northern border.{{sfnp|Wang|2011|p=110}} | |||

| The Yongle Emperor ambitiously planned to move his capital to Beijing. According to a popular legend, the capital was moved when the emperor's advisers brought the emperor to the hills surrounding Nanjing and pointed out the emperor's palace showing the vulnerability of the palace to artillery attack. | |||

| The withdrawal to the the Great Wall was a significant decline in security, as evidenced by later Ming officials debating the occupation of Ordos. The main fortress of the inner line, Xuanfu, was vulnerable to Mongol attacks after the withdrawal. However, under the Yongle Emperor, the negative effects of the withdrawal were overshadowed by Ming power and strength. Unfortunately, after his death, the Chinese did not make any attempts to reclaim the steppe for the rest of the Ming dynasty.{{sfnp|Wang|2011|p=116}} | |||

| The emperor planned to build a massive network of structures in Beijing in which government offices, officials, and the imperial family resided. After a painfully long construction time (1407–1420), the ] was finally completed and became the imperial capital for the next 500 years. | |||

| The navy was not a separate branch of the army; only the coastal guards had ships. By 1420, there were approximately 1,350 small patrol ships and an equal number of large warships scattered among the coastal garrisons. The Nanjing fleet consisted of 400 warships, 400 cargo ships manned by soldiers from Nanjing garrison guards, who were trained for naval combat (four of the ten Nanjing guards had "naval" names), and 250 treasure ships and other ships used for long-distance voyages.{{sfnp|Dreyer|1982|p=202}} | |||

| The Yongle Emperor finalised the architectural ensemble of his father's ] in Nanjing by erecting a monumental "Square Pavilion" (Sifangcheng) with an eight-metre-tall ] stele, extolling the merits and virtues of the Hongwu Emperor. In fact, the Yongle Emperor's original idea for the memorial was to erect an unprecedented stele 73 metres tall. However, due to the impossibility of moving or erecting the giant parts of that monuments, they have been left unfinished in ], where they remain to this day.<ref>{{citation|title=南京明清建筑 (Ming and Qing architecture of Nanjing)|last1=Yang|first1=Xinhua (杨新华)|last2= Lu|first2= Haiming (卢海鸣)|publisher=南京大学出版社 (Nanjing University Press)|year=2001|isbn=7-305-03669-2|pages=595–599, 616–617}}</ref> | |||

| ==Economy== | |||

| Even though the Hongwu Emperor may have meant for his descendants to be buried near his own Xiaoling Mausoleum (this was how the Hongwu Emperor's heir apparent, ] was buried), the Yongle Emperor's relocation of the capital to Beijing necessitated the creation of a new imperial burial ground. On the advice of ] experts, the Yongle Emperor chose a site north of Beijing, where he and his successors were to be buried. Over the next two centuries, thirteen emperors in total were laid to rest in the ]. | |||

| ===Population, agriculture, and crafts=== | |||

| Around 1400, the Ming dynasty had a population of 90 million.{{sfnp|Atwell|2002|p=86}} During the first third of the 15th century, the weather was more stable and warmer compared to before and after. This favorable climate allowed for rich harvests, making agriculture the foundation of the country's prosperity. Although there were occasional local disasters such as epidemics or floods, they did not significantly alter the overall situation.{{sfnp|Atwell|2002|p=84}} The government provided assistance to affected regions using state funds. | |||

| The Yongle Emperor recognized that the most effective way to ensure his own rule and that of his descendants was by supporting the peasants. For example, in 1403, when the crops were destroyed by a locust invasion in Henan, he took the initiative to organize relief efforts for the affected population. He also punished negligent officials and rejected the suggestion of Minister of Revenue, Yu Xin ({{zhi|c=郁新}}), to punish officials who were unable to collect taxes in full. The emperor argued that the root of the problem was the natural disaster, not the officials.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=78}} In 1404, when he was informed of the increase in silk production in Shandong, he responded that he would not be satisfied until there was enough food and clothing for everyone in the empire, ensuring that no one suffered from hunger or cold.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|pp=78–79}} | |||

| ===Religion and philosophy=== | |||

| The Yongle Emperor was a Chinese traditionalist. He promoted ], retained traditional ritual ceremonies, and respected the classical culture, overhauled numerous ] in ] dedicated to ]. During his reign, many Buddhist and Taoist temples were built. The Yongle Emperor sought to eradicate old Yuan influence from China; the use of popular ], habits, language, and clothing were forbidden.{{Citation needed|date=December 2011}} | |||

| {{anchor|Islam|Muslims}} | |||

| The Yongle Emperor sponsored a mosque each in ] and ]; both survive. Repairs to mosques were encouraged and conversion to other uses was forbidden.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0UzrAAAAMAAJ&q=edict+1407|title=China archaeology and art digest, Volume 3, Issue 4|year=2000|publisher=Art Text (HK) Ltd|page=29|access-date=28 June 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_hJ9aht6nZQC&q=yongle+1407+edict+&pg=PA269|title=Muslim Chinese: ethnic nationalism in the People's Republic|author=Dru C. Gladney|year=1996|publisher=Harvard Univ Asia Center|page=269|isbn=0-674-59497-5|access-date=28 June 2010}}</ref> | |||

| The northern provinces were impoverished and unproductive, and their local army and administration had become reliant on importing rice from the south during the Hongwu era. The relocation of the capital to Beijing resulted in an increase in the number of soldiers, officials, artisans, and laborers, exacerbating the issue.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=250}} In response, the government attempted to resettle people from the densely populated south to the north. However, the southerners struggled to adapt to the harsh northern climate and many returned to their homes.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=112}} By 1416, the government had abandoned this forced resettlement policy and instead implemented a strategy of supporting local development.{{sfnp|Brook|1998|p=29}} As part of this, the government began selling salt trading licenses to merchants in exchange for rice deliveries to the north.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=250}}{{efn-lr|These merchants also supplied rice to armies in the southwest and Jiaozhi.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=252}}}} On the other hand, the influx of impoverished immigrants from other parts of north China resulted in an increase in cultivated land and the production of agricultural and textile goods. This also led to the establishment of foundries in Zunhua, located in Hebei.{{sfnp|Tsai|2002|p=112}} | |||

| He commissioned ] ]{{Citation needed|date=February 2021}} to write the '']'', a compilation of Chinese civilization. It was completed in 1408<ref name="eb">{{cite encyclopedia|title=Yongle dadian (Chinese encyclopaedia)|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/654973/Yongle-dadian|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online|access-date=9 May 2012|author=Kathleen Kuiper|location=Chicago, Illinois|date= 2006}} '']''</ref> and was the world's largest general encyclopedia until being surpassed by ] in late 2007.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica|title=Encyclopedias and Dictionaries|edition=15th |year=2007 |volume=18|pages=257–286}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Finance and currency=== | ||

| The Yongle Emperor was unfamiliar with the Hongwu Emperor's frugal ways, as his reign saw significant spending on foreign expansion (such as wars in Jiaozhi and Mongolia, and naval voyages) and internal politics (such as the construction of a new capital and the restoration of the Grand Canal).{{sfnp|Wang|2011|p=118}}{{sfnp|Huang|1998|p=108}} This resulted in a significant increase in state spending, which doubled or even tripled compared to the Hongwu era.{{sfnp|Huang|1998|p=108}} However, the exact size of this spending is difficult to determine as there was no official state budget and each source of income was allocated to cover specific expenses.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=275}} The government attempted to generate revenue by issuing paper money and demanding more grain from military peasants, but these measures were not enough to solve the fiscal problems. In some areas, taxes were even reduced, but the state still managed to meet its needs through requisitions and an increase in the work obligation.{{sfnp|Huang|1998|p=108}} As a result of these financial challenges, the state's reserves, which were typically equivalent to one year's income during the Ming period, reached a record low under the Yongle Emperor's rule.{{sfnp|Chan|1988|p=276}} | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=April 2009}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ====Wars against the Mongols==== | |||

| The economic growth was supported by the government's expansion of precious metal mining, particularly copper and silver, in southern China and Jiaozhi.{{sfnp|Brook|1998|p=68}} The government also increased the emission of paper money (banknotes, ''baochao''). Revenues from silver mining, which previously accounted for only 30% of output, rose significantly from 1.1 tons in 1390 to over 10 tons in 1409, and remained at this level for the rest of the Yongle Emperor's reign.{{sfnp|Atwell|2002|p=87}} The government also produced coins from the mined copper, which were stored in state treasuries and given as gifts to foreign embassies. However, these coins continued to circulate on the domestic market alongside the ''baochao'', in contrast to the Xuande and Zhengtong eras (1425-1447) when they were removed from circulation under government pressure.{{sfnp|Von Glahn|1996|p=74}} | |||

| {{main|Yongle Emperor's campaigns against the Mongols}} | |||