| Revision as of 12:55, 8 February 2009 editKirk Hilliard (talk | contribs)1,250 edits →Anatomic anomalies: Replaced nonmedical source for a medical fact with a medical source. WP:MEDRS← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:07, 8 February 2009 edit undoKirk Hilliard (talk | contribs)1,250 edits →Anatomic anomalies: Added page number to new sourceNext edit → | ||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

| Anomalies of the female reproductive tract can result from agenesis or hypoplasia, canalization defects, lateral fusion and failure of resorption, resulting in various complications.<ref name="WebMD"></ref> | Anomalies of the female reproductive tract can result from agenesis or hypoplasia, canalization defects, lateral fusion and failure of resorption, resulting in various complications.<ref name="WebMD"></ref> | ||

| * Imperforate:<ref>{{cite book |last=DeCherney |first=Alan H. |authorlink= |coauthors= Pernoll, Martin L. and Nathan, Lauren |title=Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment | * Imperforate:<ref>{{cite book |last=DeCherney |first=Alan H. |authorlink= |coauthors= Pernoll, Martin L. and Nathan, Lauren |title=Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment | ||

| |year=2002 |publisher=McGraw-Hill Professional |quote=Imperforate hymen represents a persistent portion of the urogenital membrane ... It is one of the most common obstructive lesions of the female genital tract. ... |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=9xD0inFiEIAC&printsec=frontcover#PPA602,M1 |isbn=0838514014 }}</ref> hymenal opening non existent; will require minor surgery if it has not corrected itself by puberty to allow menstrual fluids to escape. | |year=2002 |publisher=McGraw-Hill Professional| pages=602 |quote=Imperforate hymen represents a persistent portion of the urogenital membrane ... It is one of the most common obstructive lesions of the female genital tract. ... |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=9xD0inFiEIAC&printsec=frontcover#PPA602,M1 |isbn=0838514014 }}</ref> hymenal opening non existent; will require minor surgery if it has not corrected itself by puberty to allow menstrual fluids to escape. | ||

| * Cribriform, or microperforate: sometimes confused for imperforate, the hymenal opening appears to be non existent, but has, under close examination, small openings. | * Cribriform, or microperforate: sometimes confused for imperforate, the hymenal opening appears to be non existent, but has, under close examination, small openings. | ||

| * Septate: the hymenal opening has one or more bands extending across the opening. | * Septate: the hymenal opening has one or more bands extending across the opening. | ||

Revision as of 13:07, 8 February 2009

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (January 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Hymen | |

|---|---|

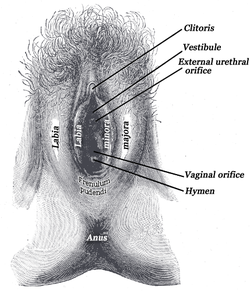

External genital organs of female. The labia minora have been drawn apart. External genital organs of female. The labia minora have been drawn apart. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | hymen vaginae |

| MeSH | D006924 |

| TA98 | A09.1.04.008 |

| TA2 | 3530 |

| FMA | 20005 |

| Anatomical terminology[edit on Wikidata] | |

The hymen is a fold of mucous membrane which surrounds or partially covers the external vaginal opening. It forms part of the vulva, or external genitalia. Slang terms are maidenhead and "cherry", as in "popping one's cherry" (losing one's virginity). However, it is not possible to confirm that a woman or post-pubescent girl is not a virgin by examining the hymen. In cases of suspected rape or sexual abuse, a detailed examination of the hymen may be carried out; but the condition of the hymen alone is often inconclusive or open to misinterpretation, especially if the patient has reached puberty. In children, although a common appearance of the hymen is crescent-shaped, many variations are possible. After a woman gives birth she may be left with remnants of the hymen called carunculae myrtiformes or the hymen may be completely absent.

Hymenal Development

The genital tract develops during embryogenesis, from 3 weeks' gestation to the second trimester, and the hymen is formed following the vagina.

At week seven, the urorectal septum forms and separates the rectum from the urogenital sinus.

At week nine, the müllerian ducts move downwards to reach the urogenital sinus, forming the uterovaginal canal and inserting into the urogenital sinus.

At week 12, the müllerian ducts fuse to create a primitive uterovaginal canal.

At month 5, the vaginal canalization is complete and the fetal hymen is formed from the proliferation of the sinovaginal bulbs (where müllerian ducts meet the urogenital sinus), and becomes perforate before or shortly after birth.

In newborn babies, still under the influence of the mother's hormones, the hymen is thick, pale pink, and redundant (folds in on itself and may protrude). For the first two to four years of life, the infant produces hormones which continue this effect.. Their hymenal opening tends to be annular (circumferential).

Hymenal resorption

Past neonatal stage, the diameter of the hymenal opening (measured within the hymenal ring) has historically been proposed to be approximately 1 mm for each year of age. In children, to make this measurement, a doctor may place a Foley catheter into the vagina and inflate the balloon behind the hymen to stretch the hymenal margin and allow for a better examination. In the normal course of life the hymenal opening can also be enlarged by tampon use, pelvic examinations, regular physical activity or sexual intercourse. Once a girl reaches puberty the hymen tends to become so elastic that it's not possible to determine whether a woman uses tampons or not by examining a hymen. In one survey only 43% of women reported bleeding the first time they had sex; indicating that the vagina of a majority of women is sufficiently opened.

The hymen is most apparent in young girls: at this time their hymen is thin and less likely to be redundant, that is to protrude or fold over on itself. In instances of suspected child abuse, doctors use the clock face system to describe the hymenal opening. The 12 o'clock position is below the urethra, and 6 o'clock is towards the anus, with the patient lying on her back.

Infants' hymenal opening tends be redundant (sleeve-like, folding in on itself), and may be combined with annular shaped.

By the time a girl reaches school-age, this hormonal influence has stopped and the hymen becomes thin, smooth, delicate and almost translucent. It is also very sensitive to touch; a physician who needed to swab the area would avoid the hymen and swab the outer vulval vestibule instead.

Prepubescent girls' hymenal opening comes in a many shapes, depending on hormonal and activity level, the most common being crescentic (posterior rim): no tissue at the 12 o'clock position; crescent shaped band of tissue from 1-2 to 10-11 o'clock at its' widest around 6 o'clock. From puberty onwards, depending on estrogen and activity levels, the hymenal tissue may be thicker and the opening is often fimbriated or erratically shaped

After giving birth, the vaginal opening usually has nothing left but hymenal tags (carunculae mytriformes) and is called "parous introitus".

Anatomic anomalies

Anomalies of the female reproductive tract can result from agenesis or hypoplasia, canalization defects, lateral fusion and failure of resorption, resulting in various complications.

- Imperforate: hymenal opening non existent; will require minor surgery if it has not corrected itself by puberty to allow menstrual fluids to escape.

- Cribriform, or microperforate: sometimes confused for imperforate, the hymenal opening appears to be non existent, but has, under close examination, small openings.

- Septate: the hymenal opening has one or more bands extending across the opening.

Hymens in other animals

Due to similar reproductive system development, many mammals, from chimpanzees and elephants to manatees and whales, retain hymens.

Hymenoplasty

See main article Hymenorrhaphy

In some religious cultures the concept of an intact hymen is highly valued at marriage. In Korea the word for hymen translates literally as “virgin-skin” and a small industry has grown up around its surgical construction through plastic surgery. In 1994 the Korean Medical Research Center was made to pay compensation to a 40-year-old woman for extreme psychological distress after she lost her hymen during a Pap smear test. The court found that, “it is clear that the hymen is still recognized as a symbol of ‘virginity’ and keeping virginity is valued in society". Some Korean prenatal clinics offers STD tests with hymenorrhaphy, in order to "free" women from their history of sexual experiences in the past. These surgeries are not even approved by the Korean medical association because they are based on myths and efforts at re-education are being made.

Debunking Myths

- The condition of the hymen is not a reliable indicator of whether a woman past puberty has actually engaged in sexual intercourse.

- "Although some women are born without a hymen, most have one, and the hymen varies in size and shape from woman to woman."

- In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, medical researchers have used the presence of the hymen, or lack thereof, as founding evidence of physical diseases such as "womb-fury". If not cured, womb-fury would, according to these early doctors, result in death. The cure, naturally enough, was marriage, since a woman could then go about having sexual intercourse on a "normal" schedule that would stop womb-fury from killing her, hence opening her hymen.

Modern perspectives

As early as the late sixteenth century, Ambroise Paré and Andreas Laurentius asserted to have never seen the hymen and that it was "a primitive myth, unworthy of a civilized nation like France."

In late 2005, Monica Christiansson, former maternity ward nurse and Carola Eriksson, a PhD student at Umeå University announced that according to studies of medical literature and practical experience, the hymen should be considered a social and cultural myth, based on deeply rooted stereotypes of women's roles in sexual relations with men. Christiansson and Eriksson support their claims by pointing out that there are no accurate medical descriptions of what a hymen actually consists of. Statistics presented by the two state that fewer than 30% of women who have gone through puberty and have consensual intercourse bleed the first time. Christiansson has expressed an opinion that the use of the term "hymen" should be discontinued and that it should be considered an integral part of the vaginal opening.

It is argued that since the hymen has been culturally constructed to be the sign of virginity, its existence plays into a political discourse that circulates around the body.

By examining women's bodies for the existence of the hymen, researchers have used it to determine whether or not women are "virtuous." Sherry B. Ortner, professor at the University of Chicago, explains how "the hymen itself emerges physiologically with the development of sexual purity codes" as an element of patriarchy.

In some cultures it is still customary to examine a woman for her hymen before her marriage to see if she is truly fit to be married. If she is found with a broken hymen, or to have no hymen at all, often the man would not feel obligated to marry her. This has prompted some women who wish to marry within such cultures to seek surgery to restore their hymens to a socially acceptable state.

References

- Emans, S. Jean. "Physical Examination of the Child and Adolescent" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 62

- ^ Perlman, Sally E. (2004). Clinical protocols in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Parthenon. p. 131.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Emans, S. Jean. "Physical Examination of the Child and Adolescent" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 63-4

- Emans, S. Jean. "Physical Examination of the Child and Adolescent" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 63

- Knight, Bernard (1997). Simpson's Forensic Medicine (11th edition ed.). London: Arnold. p. 114.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ |http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/269050-overviewWebMD

- ^ McCann, J; Rosas, A. and Boos, S. (2003) "Child and adolescent sexual assaults (childhood sexual abuse)" in Payne-James, Jason; Busuttil, Anthony and Smock, William (eds). Forensic Medicine: Clinical and Pathological Aspects, Greenwich Medical Media: London, a)p.453, b)p.455 c)p.460.

- Heger, Astrid (2000). Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas (Second edition ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 116.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Emans, S. Jean. "Physical Examination of the Child and Adolescent" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 64-5

- Muram, David. "Anatomical and Physiologic Changes" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 105-7.

- Pokorny, Susan. "Anatomical Terms of Female External Genitalia" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 110.

- Pokorny, Susan. "Anatomical Terms of Female External Genitalia" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 110-1.

- Heger, Astrid; Emans, S. Jean and Muram, David (2000). Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press, 116.

- DeCherney, Alan H. (2002). Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 602. ISBN 0838514014.

Imperforate hymen represents a persistent portion of the urogenital membrane ... It is one of the most common obstructive lesions of the female genital tract. ...

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Blank, Hanne (2007). Virgin: The Untouched History. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 23.

- Blackledge, Catherine (2004). The Story of V. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813534550.

Hymens, or vaginal closure membranes or vaginal constrictions, as they are often referred to, are found in a number of mammals, including llamas, ...

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Park, J. I., Compensation for hymen lost: Not loss of virginity but a medical accident. Chosun Daily Aug 1994

- http://www.yunlee.co.kr

- International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, South Korea by Hyung-Ki Choi, M.D., Ph.D., and Huso Yi, Ph.D.

- Gray, Henry (1901/1975). Grays Anatomy (Illustrated Running Press Edition ed.). Philidelphia Pa: Running Press. p. 1027. ISBN 0914294083.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - http://health.discovery.com/centers/sex/sexpedia/hymen.html

- The linkage between the hymen and social elements of control has been taken up in Marie Loughlin's book Hymeneutics: Interpreting Virginity on the Early Modern Stage published in 1997

- Nerikes Allehanda's article on Christiansson's and Eriksson's research Template:Sv icon

- Ortner, Sherry. "The Virgin and the State" in Feminist Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3. (Oct., 1978), pp. 19-35.

- "In Europe, Debate Over Islam and Virginity". New York Times. June 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

Like an increasing number of Muslim women in Europe, she had a hymenoplasty, a restoration of her hymen, the vaginal membrane that normally breaks in the first act of intercourse.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- The Female Hymen and its Significance

- Hymen gallery - Illustrations of hymen types

- Magical Cups and Bloody Brides the historical context of virginity in a frank and easy-to-understand manner.

- 20 Questions About Virginity - Interview with Hanne Blank, author of "Virgin: The Untouched History". Discusses relationship between hymen and concept of virginity.

- Vaginismus-Awareness-Network Explanation of the hymen, myths on first-time sex, Hymenectomies and Vaginismus (Painful sex or Fear of Penetration)

| Female reproductive system | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Blood supply | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||