This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Alexikoua (talk | contribs) at 08:21, 11 March 2016 (rv poorly explained adjustments). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 08:21, 11 March 2016 by Alexikoua (talk | contribs) (rv poorly explained adjustments)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| Geographical distribution |

| Albanian culture |

| Albanian language |

|

Religion

|

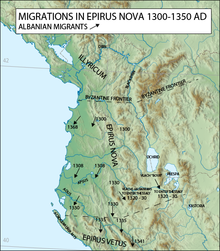

The origin of the Albanians has been for some time a matter of dispute among historians. Contemporary historians conclude that the Albanians are descendants of populations of the prehistoric Balkans, such as the Illyrians, Dacians or Thracians. Little is known about these peoples, and they blended into one another in Thraco-Illyrian and Daco-Thracian contact zones even in antiquity.

The Albanians first appear in the historical record in Byzantine sources of the 11th century. At this point, they were already fully Christianized. Very little evidence of pre-Christian Albanian culture survives, although Albanian mythology and folklore are of Paleo-Balkanic origin and almost all of their elements are pagan, in particular showing Greek influence.

The Albanian language forms a separate branch of Indo-European, first attested in the 15th century, and is considered to have evolved from one of the Paleo-Balkans languages of antiquity.

Studies in genetic anthropology show that the Albanians share the same ancestry as most other European people.

Place of origin

The Albanian language is attested in a written form only in the 15th century AD, when the Albanian ethnos was already formed. In the absence of prior data on the language, scholars have used the Latin and Slav loans into Albanian for identifying its location of origin.

The place where the Albanian language was formed is uncertain, but analysis has suggested that it was in a mountainous region, rather than in a plain or seacoast. While the words for plants and animals characteristic of mountainous regions are entirely original, the names for fish and for agricultural activities are generally assumed to have been borrowed from other languages. However, considering the presence of some preserved old terms related to the sea fauna, some have assumed that this vocabulary might have been lost in the course of time after the proto-Albanian tribes were pushed back into the inland during invasions. The Slavic loans in Albanian suggest that contacts between two populations took place when Albanians dwelt in forests 600–900 metres above sea level. The overwhelming amount of mountaineering and shepherding vocabulary, coupled with the extensive influence of Latin makes it likely that the Albanians originated north of the Jireček Line, further north and inland than the current borders of Albania suggest. It has long been recognized that there are two treatments of Latin loans in Albanian, of Old Dalmatian type and Romanian type, but that would point out to two geographic layers, coastal Adriatic and inner Balkan region. Some scholars believe that the Latin influence over Albanian is of Eastern Romance origin, rather than of Dalmatian origin, which would exclude Dalmatia as a place of origin. Adding to this the several hundred words in Romanian that are cognate only with Albanian cognates (see Eastern Romance substratum), these scholars assume that Romanians and Albanians lived in close proximity at one time. The areas where this might have happened is the Morava valley in eastern Serbia.

Another argument in favor of a northern origin for the Albanian language is the relatively small number of words of Greek origin, mostly from Doric dialect, even though Southern Illyria neighbored the Classical Greek civilization and there was a number of Greek colonies along the Illyrian coastline. However, in view of the amount of Albanian-Greek isoglosses, which the scholar Vladimir Orel considers surprisingly high (in comparison with the Indo-Albanian and Armeno-Albanian ones), the author concludes that this particular proximity could be the result of intense secondary contacts of two proto-dialects.

Those scholars who maintain the Illyrian origin of Albanians maintain that the indigenous Illyrian tribes dwelling in South Illyria went up into the mountains when Slavs occupied the lowlands, while another version of this hypothesis maintains that the Albanians are the descendants of Illyrian tribes located between Dalmatia and the Danube, who spilled south.

The scholars who support a Dacian origin of Albanians maintain that between the 3rd and 6th centuries AD, Albanians moved southwards from the Moesian area, while those scholars who maintain a Thracian origin hypothesize that the proto-Albanians are to be located in Thracian territory in the area between Niš, Skopje, Sofia and Albania or from the Rhodope and Balkan mountains, where they moved to Albania before the arrival of the Slavs.

Primary sources

Ancient and early medieval references to people of unknown ethnicity

Main article: Albania (name)- In the 2nd century BC, the History of the World written by Polybius, mentions a location named Arbon (Template:Lang-grc-gre; Latinised form: Arbo) that was perhaps an island in Liburnia or another location within Illyria. Stephanus of Byzantium, centuries later, cites Polybius, saying it was a city in Illyria and gives an ethnic name (see below) for its inhabitants.

- In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria, drafted a map that shows the city of Albanopolis (located Northeast of Durrës) and the tribe of Albanoi, which were viewed as Illyrians by later historians.

- In the 6th century AD, Stephanus of Byzantium, in his important geographical dictionary entitled Ethnica (Ἐθνικά), mentions a city in Illyria called Arbon (Template:Lang-grc-gre), and gives an ethnic name for its inhabitants, in two singular number forms, i.e. Arbonios (Template:Lang-grc-gre; pl. Ἀρβώνιοι Arbonioi) and Arbonites (Template:Lang-grc-gre; pl. Ἀρβωνῖται Arbonitai). He cites Polybius (as he does many other times in Ethnica).

11th–13th century references to Albanians

- The Arbanasi people are recorded as being 'half-believers' (non-Orthodox Christians) and speaking their own language in the Fragment of Origins of Nations between 1000–1018 by an anonymous author in a Bulgarian text of the 11th century.

- In History written in 1079–1080, Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. It is disputed, however, whether the "Albanoi" of the events of 1043 refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense or whether "Albanoi" is a reference to Normans from Sicily under an archaic name (there was also a tribe of Italy by the name of Albani). However a later reference to Albanians from the same Attaliates, regarding the participation of Albanians in a rebellion in 1078, is undisputed.

- Arbanitai of Arbanon are recorded in an account by Anna Comnena of the troubles in that region caused in the reign of her father Alexius I Comnenus (1081–1118) by their fight against the Normans.

- The earliest Serbian source mentioning "Albania" (Ar'banas') is a charter by Stefan Nemanja, dated 1198, which lists the region of Pilot (Pulatum) among the parts Nemanja conquered from Albania (ѡд Арьбанась Пилоть, "de Albania Pulatum").

- In the 12th to 13th centuries, Byzantine writers use the words Arbanon (Template:Lang-gkm) for a principality in the region of Kruja.

- The presence of Albanians in Epirus is recorded in a Venetian document of 1210, which states that "the continent facing the island of Corfu is inhabited by Albanians."

- 1285 in Dubrovnik (Ragusa) a document states: "Audivi unam vocem clamantem in monte in lingua albanesca" (I heard a voice crying in the mountains in the Albanian language).

Albanian endonym "Shqiptar"

There are various theories of the origin of the word shqiptar:

- A theory by Ludwig Thallóczy, Milan Šufflay and Konstantin Jireček, which is today considered obsolete, derived the name from a Drivastine family name recorded in varying forms during the 14th century: Schepuder (1368), Scapuder (1370), Schipudar, Schibudar (1372), Schipudar (1383, 1392), Schapudar (1402), etc.

- Gustav Meyer derived Shqiptar from the Albanian verbs shqipoj (to speak clearly) and shqiptoj (to speak out, pronounce), which are in turn derived from the Latin verb excipere, denoting brethren who speak the Albanian language, similar to the ethno-linguistic dichotomies Sloven-Nemac and Deutsch-Wälsch. This theory is also sustained by Robert Elsie.

- Petar Skok suggested that the name originated from Scupi (Template:Lang-sq), the capital of the Roman province of Dardania.

- The most accredited theory, at least among Albanians, is that of Maximilian Lambertz, who derived the word from the Albanian noun shqipe or shqiponjë (eagle), which, according to Albanian folk etymology, denoted a bird totem dating from the times of Skanderbeg, as displayed on the Albanian flag.

First attestation of the Albanian language

The first document in the Albanian language (as spoken in the region around Mat) was recorded in 1462 by Paulus Angelus (whose name was later Albanized to Pal Engjëll), the archbishop of the Catholic Archdiocese of Durazzo (modern Durrës).

Paleo-Balkanic predecessors

While Albanian (shqip) ethnogenesis clearly postdates the Roman era, an element of continuity from the pre-Roman provincial population is widely held plausible, on linguistic and archaeological grounds.

The three chief candidates considered by historians are Illyrian, Dacian, or Thracian, though there were other non-Greek groups in the ancient Balkans, including Paionians (who lived north of Macedon) and Agrianians. The Illyrian language and the Thracian language are often considered to have been on different Indo-European branches. Not much is left of the old Illyrian, Dacian or Thracian tongues, making it difficult to match Albanian with them.

There is debate whether the Illyrian language was a centum or a satem language. It is also uncertain whether Illyrians spoke a homogeneous language or rather a collection of different but related languages that were wrongly considered the same language by ancient writers. The Venetic tribes, formerly considered Illyrian, are no longer considered cateogrised with Illyrians. The same is sometimes said of the Thracian language. For example, based on the toponyms and other lexical items, Thracian and Dacian were probably different but related languages.

In the early half of the 20th century, many scholars thought that Thracian and Illyrian were one language branch, but due to the lack of evidence, most linguists are skeptical and now reject this idea, and usually place them on different branches.

The origins debate is often politically charged, and to be conclusive more evidence is needed. Such evidence unfortunately may not be easily forthcoming because of a lack of sources. Scholars are beginning to move away from a single-origin scenario of Albanian ethnogenesis. The area of what is now Macedonia and Albania was a melting pot of Thracian, Illyrian and Greek cultures in ancient times.

Illyrian origin

See also: IllyriansThe theory that Albanians were related to the Illyrians was proposed for the first time by the Swedish historian Johann Erich Thunmann in 1774. The scholars who advocate an Illyrian origin are numerous. There are two variants of the theory: one is that the Albanians are the descendants of indigenous Illyrian tribes dwelling in what is now Albania. The other is that the Albanians are the descendants of Illyrian tribes located north of the Jireček Line and probably north or northeast of Albania.

Arguments for the Illyrian origin

The arguments for the Illyrian-Albanian connection have been as follows:

- The national name Albania is derived from Albanoi, an Illyrian tribe mentioned by Ptolemy about 150 AD.

- From what is known from the old Balkan populations territories (Greeks, Illyrians, Thracians, Dacians), the Albanian language is spoken in the same region where Illyrian was spoken in ancient times.

- There is no evidence of any major migration into Albanian territory since the records of Illyrian occupation.

- Many of what remain as attested words to Illyrian have an Albanian explanation and also a number of Illyrian lexical items (toponyms, hydronyms, oronyms, anthroponyms, etc.) have been linked to Albanian.

- Words borrowed from Greek (e.g. Gk (NW) "device, instrument" mākhaná > *mokër "millstone" Gk (NW) drápanon > *drapër "sickle" etc.) date back before the Christian era and are mostly of the Doric Greek dialect, which means that the ancestors of the Albanians were in contact with the northwestern part of Ancient Greek civilization and probably borrowed words from Greek cities (Dyrrachium, Apollonia, etc.) in the Illyrian territory, colonies which belonged to the Doric division of Greek, or from contacts in the Epirus area.

- Words borrowed from Latin (e.g. Latin aurum > ar "gold", gaudium > gaz "joy" etc.) date back before the Christian era, while the Illyrians on the territory of modern Albania were the first from the old Balkan populations to be conquered by Romans in 229–167 BC, the Thracians were conquered in 45 AD and the Dacians in 106 AD.

- The ancient Illyrian place-names of the region have achieved their current form following Albanian phonetic rules e.g. Durrachion > Durrës (with the Albanian initial accent) Aulona > Vlonë~Vlorë (with rhotacism) Scodra > Shkodra etc.

- The characteristics of the Albanian dialects Tosk and Geg in the treatment of the native and loanwords from other languages, have led to the conclusion that the dialectal split preceded the Slavic migration to the Balkans which means that in that period (5th to 6th century AD) Albanians were occupying pretty much the same area around Shkumbin river which straddled the Jirecek line.

Arguments against Illyrian origin

The theory of an Illyrian origin of the Albanians is challenged on archaeological and linguistic grounds.

- Although the Illyrian tribe of the Albanoi and the place Albanopolis could be located near Krujë, nothing proves a relation of this tribe to the Albanians, whose name appears for the first time in the 11th century in Byzantine sources

- According to linguist Vladimir I. Georgiev, the theory of an Illyrian origin for the Albanians is weakened by a lack of any Albanian names before the 12th century and the relative absence of Greek influence that would surely be present if the Albanians inhabited their homeland continuously since ancient times. According to Georgiev if the Albanians originated near modern-day Albania, the number of Greek loanwords in the Albanian language should be higher.

- According to Georgiev, although some Albanian toponyms descend from Illyrian, Illyrian toponyms from antiquity have not changed according to the usual phonetic laws applying to the evolution of Albanian. Furthermore, placenames can be a special case and the Albanian language more generally has not been proven to be of Illyrian stock.

- Many linguists have tried to link Albanian with Illyrian, but without clear results. Albanian belongs to the satem group within Indo-European language tree, while there is a debate whether Illyrian was centum or satem. On the other hand, Dacian and Thracian seem to belong to satem.

- There is a lack of clear archaeological evidence for a continuous settlement of an Albanian-speaking population since Illyrian times. For example, while Albanians scholars maintain that the Komani-Kruja burial sites support the Illyrian-Albanian continuity theory, most scholars reject this and consider that the remains indicate a population of Romanized Illyrians who spoke a Romance language.

Thracian or Dacian origin

Aside from an Illyrian origin, a Dacian or Thracian origin is also hypothesized. There are a number of factors taken as evidence for a Dacian or Thracian origin of Albanians. According to Vladimir Orel, for example, the territory associated with proto-Albanian almost certainly does not correspond with that of modern Albania, i.e. the Illyrian coast, but rather that of Dacia Ripensis and farther north.

The Romanian historian I.I. Russu has originated the theory that Albanians represent a massive migration of the Carpi population pressed by the Slavic migrations. Due to political reasons the book was first published in 1995 and translated in German by Konrad Gündisch.

The German historian Gottfried Schramm (1994) suggests an origin of the Albanians in the Bessoi, a Thracian tribe that was Christianized as early as during the 4th century. Schramm argues that such an early Christianization would explain the otherwise surprising virtual absence of any traces of a pre-Christian pagan religion among the Albanians as they appear in history during the Late Middle Ages. According to this theory, the Bessoi were deported en masse by the Byzantines at the beginning of the 9th century to central Albania for the purpose of fighting against the Bulgarians. In their new homeland, the ancestors of the Albanians took the geographic name Arbanon as their ethnic name and proceeded to assimilate local populations of Slavs, Greeks, and Romans.

Linguist Eric Hamp on the other hand posits that Albanian is more closely relate to Baltic and Slavic rather than Thracian.

Cities whose names follow Albanian phonetic laws – such as Shtip (Štip), Shkupi (Skopje) and Niš – lie in the areas, believed, to once inhabited by Thracians, Paionians and Dardani; the later most often considered Illyrians by ancient historians. While there still is no clear picture of where the Illyrian-Thracian border was, Naissus is mostly considered Illyrian territory.

There are some close correspondences between Thracian and Albanian words. However, as with Illyrian, most Dacian and Thracian words and names have not been closely linked with Albanian (v. Hamp). Also, many Dacian and Thracian placenames were made out of joined names (such as Dacian Sucidava or Thracian Bessapara; see List of Dacian cities and List of ancient Thracian cities), while the modern Albanian language does not allow this.

The Bulgarian linguist Vladimir I. Georgiev posits that that Albanians descend from a Dacian population from Moesia, now the Morava region of eastern Serbia, and that Illyrian toponyms are found in a far smaller area than the traditional area of Illyrian settlement, and that the Albanians originate from the Morava region in Moesia (nowadays eastern Serbia).

According to Georgiev, Latin loanwords into Albanian show East Balkan Latin (proto-Romanian) phonetics, rather than West Balkan (Dalmatian) phonetics. Combined with the fact that the Romanian language contains several hundred words similar only to Albanian, Georgiev proposes the Albanian language formed between the 4th and 6th centuries in or near modern-day Romania, which was Dacian territory. He suggests that Romanian is a fully Romanised Dacian language, whereas Albanian is only partly so. Albanian and Eastern Romance also share grammatical features (see Balkan language union) and phonological features, such as the common phonemes or the rhotacism of "n".

Apart from the linguistic theory that Albanian is more akin to East Balkan Romance (i.e. Dacian substrate) than West Balkan Romance (i.e. Illyrian/Dalmatian substrate), Georgiev also notes that marine words in Albanian are borrowed from other languages, suggesting that Albanians were not originally a coastal people (as the Illyrians were). According to Georgiev the scarcity of Greek loan words also supports a Dacian theory – if Albanians originated in the region of Illyria there would surely be a heavy Greek influence. Lastly, Georgiev also notes that Illyrian toponyms do not follow Albanian phonetic laws. According to historian John Van Antwerp Fine, who does define "Albanians" in his glossary as "an Indo-European people, probably descended from the ancient Illyrians", nevertheless "these are serious (non-chauvinistic) arguments that cannot be summarily dismissed."

Hamp, on the other hand, seems to agree with Georgiev in relation to Albania with Dacian but disagrees on the chronological order of events. Hamp argues that Albanians could have arrived from present day Kosovo to their current geographical position sometime in late Roman period. Also, contrary to Georgiev, he indicates there are words that follow Dalmatian phonetic rules in Albanian giving as an example the word drejt 'straight' < d(i)rectus matching Old Dalmatian traita < tract.

There are no records that indicate a major migration of Dacians into present day Albania, but two Dacian cities existed: Thermidava close to Scodra and Quemedava in Dardania. Also, a Thracian settlement was known to have existed in Dardania, ar Dardapara. Phrygian tribes such as the Bryges were present in Albania near Durrës since before the Roman conquest (v. Hamp). An argument against a Thracian origin (which does not apply to Dacian) is that most Thracian territory was on the Greek half of the Jirecek Line, aside from varied Thracian populations stretching from Thrace into Albania, passing through Paionia and Dardania and up into Moesia; it is considered that most Thracians were Hellenized in Thrace (v. Hoddinott) and Macedonia.

The Dacian theory could also be consistent with the known patterns of barbarian incursions. Although there is no documentation of an Albanian migration, "during the fourth to sixth centuries the Rumanian region was heavily affected by large-scale invasion of Goths and Slavs, and the Morava valley (in Serbia) was a main invasion route and the site of the earliest known Slavic sites. Thus this would have been a region from which an indigenous population would naturally have fled", for example to the relative safety of mountainous northern Albania.

Theories of influence from an extinct, unidentified Romance language

Romanian scholars such as Vatasescu and Mihaescu, using lexical analysis of the Albanian language, have concluded that Albanian was heavily influenced by an extinct Romance language that was distinct from both Romanian and Dalmatian. Because the Latin words common to only Romanian and Albanian are significantly less than those that are common to only Albanian and Western Romance, Mihaescu argues that the Albanian language evolved in a region with much greater contact to Western Romance regions than to Romanian-speaking regions, and located this region in present-day Albania, Kosovo and Western Macedonia, spanning east to Bitola and Pristina.

It has been concluded that the partial Latinization of Roman-era Albania was heavy in coastal areas, the plains and along the Via Egnatia, which passed through Albania. In these regions, Madgearu notes that the survival of Illyrian names and the depiction of people with Illyrian dress on gravestones is not enough to prove successful resistance against Romanization, and that in these regions there were many Latin inscriptions and Roman settlements. Madgearu concludes that the only the northern mountain regions escaped Romanization. In some regions, Madgearu concludes that it has been shown that in some areas a Latinate population that survived until at least the seventh century passed on local placenames, which had mixed characteristics of Eastern and Western Romance, into the Albanian language

Archaeological evidence

The Komani culture theory, which is generally viewed by Albanian archaeologists as archaeological evidence of evolution from "Illyrian" ancestors to medieval Albanians, has found little support outside Albania. Indeed, Anglo-American anthropologists highlight that even if regional population continuity can be proven, this does not translate into linguistic, much less ethnic continuity. Both aspects of culture can be modified or drastically changed even in the absence of large-scale population flux.

Prominent in the discussions are certain brooch forms, seen to derive from Illyrian prototypes. However, a recent analysis revealed that whilst broad analogies are indeed evident to Iron Age Illyrian forms, the inspiration behind Komani fibulae is more closely linked to Late Roman fibulae, particularly those from Balkan forts in the present-day Serbia and northwestern Bulgaria. This might suggest that after the general collapse of the Roman limes in the early 7th century, some late Roman population withdrew to Epirus. However, assemblages also have many "barbarian" artefacts, such as Slavic bow-fibulae, Avar-styled belt mounts and Carolingian glass vessels. By contrast, beyond the immediate Adriatic littoral, most of the west Balkans (including Dardania) appears to have been depopulated after the early 7th century from almost a century. Another aspect of discontinuity is the design of the tombs: pits lined by limestone rocks, a construction used in the region since the Iron Age period. However the tombs in the 7th century, such burials are in a Christian context (placed next to churches) rather than reversion to a pagan Illyrian past.

A further argument against a proto-Albanian affinity of the Komani culture is that very similar material is found in central Dalmatia, Montenegro, western Macedonia and south-eastern Bulgaria, along the Via Egnatia; and even islands such as Corfu and Sardinia. The 'late Roman' character of the assemblages has led some to hypothesize that it represented Byzantine garrisons. However, already by this time, literary sources give testimony of widespread Slavic settlements in the central Balkans. Specifically for Albania, the study of lexicon and toponyms might suggest that speakers of proto-Albanian, Slavic and Romance co-existed but occupied specific ecologic/ economic niches.

Genetic studies

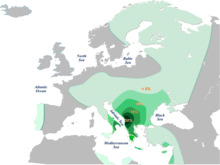

Further information: Genetic history of EuropeVarious genetic studies have been done on the European population, some of them including current Albanian population, Albanian-speaking populations outside Albania, and the Balkan region as a whole.

Y-Dna

The three haplogroups most strongly associated with Albanian people (E-V13, R1b and J2b) are often considered to have arrived in Europe from the Near East with the Neolithic revolution or late Mesolithic, early in the Holocene epoch. Within the Balkans, all three have a local peak in Kosovo, and are overall more common among Albanians, Greeks and Vlachs than Slavs (albeit with some representation among Bulgarians). R1b has much higher frequencies in areas of Europe further to the West, while E1b1b and J2 are widespread at lower frequencies throughout Europe and also have very large frequencies among Greeks, Italians, Macedonians and Bulgarians.

- Y haplogroup E1b1b (E-M35) in the modern Balkan population is dominated by its sub-clade E1b1b1a (E-M78) and specifically by the most common European sub-clade of E-M78, E-V13. Most E-V13 in Europe and elsewhere descend from a common ancestor who lived in the late Mesolithic or Neolithic, possibly in the Balkans. The current distribution of this lineage might be the result of several demographic expansions from the Balkans, such as that associated with the Neolithic revolution, the Balkan Bronze Age, and more recently, during the Roman era during the so-called "rise of Illyrican soldiery".

- Y haplogroup J in the modern Balkans is mainly represented by the sub-clade J2b (also known as J-M12 or J-M102 for example). Like E-V13, J2b is spread throughout Europe with a seeming centre and origin near Albania. Its relatives within the J2 clade are also found in high frequencies elsewhere in Southern Europe, especially Greece and Italy, where it is more diverse. J2b itself is fairly rare outside of ethnic Albanian territory (where it hovers around 14-16%), but can also be found at significant frequencies among Romanians (8.9%) and Greeks (8.7%)

- Haplogroup R1b is common all over Europe but especially common on the western Atlantic coast of Europe, and is also found in the Middle East, the Caucasus and some parts of Africa. In Europe including the Balkans, it tends to be less common in Slavic speaking areas, where R1a is often more common. It shows similar frequencies among Albanians and Greeks at around 20% of the male population, but is much less common in elsewhere in the Balkans.

Common in the Balkans but not specifically associated with Albania and the Albanian language are I-M423 and R1a-M17:

- Y haplogroup I is found mostly in Europe, and may have been there since before the LGM. Several of its sub-clades are found in significant amounts in the Balkans. The specific I sub-clade which has attracted most discussion in Balkan studies currently referred to as I2a2, defined by SNP M423 This clade has higher frequencies to the north of the Albanophone area, in Dalmatia and Bosnia.

- Haplogroup R1a is common in Central and Eastern Europe (and is also common in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent). In the Balkans, it is strongly associated with Slavic areas.

A study by Peričić et al. in 2005 found the following Y-Dna haplogroup frequencies in Albanians from Kosovo with haplogroup E1b1b and its subclades representing 47.4% of the total (note that Albanians from other regions do not show quite as high a percentage of E1b1b):

| N | E-M78* | E-V13 | E-M81 | E-M123 | J2b | I1 | I2a2 | R1b | R1a | P |

| 114 | 1.75% | 43.85% | 0.90% | 0.90% | 16.70% | 5.31% | 2.65% | 21.10% | 4.42% | 1.77% |

A study by Battaglia et al. in 2008 found the following haplogroup distributions among Albanians in Albania itself:

| N | E-M78* | E-V13 | G | I1 | I2a1 | I2b | J1 | J2a | J2b | R1a | R1b |

| 55 | 1.8% | 23.6% | 1.8% | 3.6% | 14.5% | 3.6% | 3.6% | 5.4% | 14.5% | 9.1% | 18.2% |

The same study by Battaglia et al. (2008) also found the following distributions among Albanians in Macedonia:

| N | E-M78* | E-V13 | E-M123 | G | I1 | I2a | I2a1 | I2a2 | J1 | J2a1b | J2b | R1a | R1b |

| 64 | 1.6% | 34.4% | 3.1% | 1.6% | 4.7% | 1.6% | 9.4% | 1.6% | 6.3% | 1.6% | 14.1% | 1.6% | 18.8% |

mtDna

Another study of old Balkan populations and their genetic affinities with current European populations was done in 2004, based on mitochondrial DNA on the skeletal remains of some old Thracian populations from SE of Romania, dating from the Bronze and Iron Age. This study was during excavations of some human fossil bones of 20 individuals dating about 3200–4100 years, from the Bronze Age, belonging to some cultures such as Tei, Monteoru and Noua were found in graves from some necropoles SE of Romania, namely in Zimnicea, Smeeni, Candesti, Cioinagi-Balintesti, Gradistea-Coslogeni and Sultana-Malu Rosu; and the human fossil bones and teeth of 27 individuals from the early Iron Age, dating from the 10th to 7th centuries BC from the Hallstatt Era (the Babadag culture), were found extremely SE of Romania near the Black Sea coast, in some settlements from Dobrogea, namely: Jurilovca, Satu Nou, Babadag, Niculitel and Enisala-Palanca. After comparing this material with the present-day European population, the authors concluded:

Computing the frequency of common point mutations of the present-day European population with the Thracian population has resulted that the Italian (7.9%), the Albanian (6.3%) and the Greek (5.8%) have shown a bias of closer genetic kinship with the Thracian individuals than the Romanian and Bulgarian individuals (only 4.2%).

Autosomal DNA

Analysis of autosomal DNA, which analyses all genetic components has revealed that few genetic discontinuities exist in European populations, apart from certain outliers such as Saami, Sardinians, Basques and Kosovar Albanians. They found that Albanians, on the one hand, have a high amount of identity by descent sharing, suggesting that both Albanians from Albania and Kosovo derived from a relatively small population that expanded recently and rapidly in the last 1,500 years. On the other hand, they are not wholly isolated or endogamous, as they share a significant amount of descent with nearby Macedonian, Greek and Italian populations. The recent growth is particularly evident in Kosovar Albanians, which show particularly high levels of homogeneity, in contrast to the diversity otherwise found in other Balkan populations.

Obsolete theories

Caucasian theory

One of the earliest theories on the origins of the Albanians, now considered obsolete, identified the proto-Albanians with an area of the Caucasus referred to by classical geographers as "Albania", which roughly corresponds with modern-day Azerbaijan. This theory supposed that the ancestors of the Albanians migrated westward to the Balkans in the late classical or early Medieval period. The Caucasian theory was first proposed by Renaissance humanists who were familiar with the works of classical geographers, and later developed by early 19th-century French consul and writer François Pouqueville. It was rendered obsolete in the 19th century when linguists proved that Albanian is an Indo-European, rather than Caucasian language.

Pelasgian theory

Another obsolete myth on the origin of the Albanians is that they descend from the Pelasgians, a broad term used by classical authors to denote the autochthonous inhabitants of Greece. This theory was developed by the Austrian linguist Johann Georg von Hahn in his work Albanesische Studien in 1854. According to Hahn, the Pelasgians were the original proto-Albanians and the language spoken by the Pelasgians, Illyrians, Epirotes and ancient Macedonians were closely related. This theory quickly attracted support in Albanian circles, as it established a claim of predecence over other Balkan nations, particularly the Greeks. In addition to establishing "historic right" to territory this theory also established that the ancient Greek civilization and its achievements had an "Albanian" origin. The theory gained staunch support among early 20th-century Albanian publicists. This theory is rejected by scholars today. In contemporary times with the Arvanite revival of the Pelasgian theory, it has also been recently borrowed by other Albanian speaking populations within and from Albania in Greece to counter the negative image of their communities.

Italian theory

Laonikos Chalkokondyles (c. 1423–1490), the Byzantine historian, thought that the Albanians hailed from Italy. The theory has its origin in the first mention of the Albanians, disputed whether it refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense, made by Attaliates (11th century): "... For when subsequent commanders made base and shameful plans and decisions, not only was the island lost to Byzantium, but also the greater part of the army. Unfortunately, the people who had once been our allies and who possessed the same rights as citizens and the same religion, i.e. the Albanians and the Latins, who live in the Italian regions of our Empire beyond Western Rome, quite suddenly became enemies when Michael Dokenianos insanely directed his command against their leaders..."

See also

- Albanian language

- Albanian nationalism

- List of Romanian words of possible Dacian origin with correspondence in Albanian

- Ethnogenesis

- Historiography and nationalism

- Origin of the Romanians

- Paleo-Balkan languages

- Prehistoric Balkans

References

- ^ John Van Antwerp Fine, The early Medieval Balkans: A critical survey from the sixth century to the late twelfth century. University of Michigan Press, 1991, p.10

- Bonefoy, Yves (1993). American, African, and Old European mythologies. University of Chicago Press. p. 253. ISBN 0-226-06457-3.

- Mircea Eliade, Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of religion, Macmillan, 1987, ISBN 978-0-02-909700-7, p. 179.

- Michele Belledi, Estella S. Poloni, Rosa Casalotti, Franco Conterio, Ilia Mikerezi, James Tagliavini and Laurent Excoffier. "Maternal and paternal lineages in Albania and the genetic structure of Indo-European populations". European Journal of Human Genetics, July 2000, Volume 8, Number 7, pp. 480-486. "Mitochondrial DNA HV1 sequences and Y chromosome haplotypes (DYS19 STR and YAP) were characterized in an Albanian sample and compared with those of several other Indo-European populations from the European continent. No significant difference was observed between Albanians and most other Europeans, despite the fact that Albanians are clearly different from all other Indo-Europeans linguistically. We observe a general lack of genetic structure among Indo-European populations for both maternal and paternal polymorphisms, as well as low levels of correlation between linguistics and genetics, even though slightly more significant for the Y chromosome than for mtDNA. Altogether, our results show that the linguistic structure of continental Indo-European populations is not reflected in the variability of the mitochondrial and Y chromosome markers. This discrepancy could be due to very recent differentiation of Indo-European populations in Europe and/or substantial amounts of gene flow among these populations."

- The Illyrians The Peoples of Europe Author John Wilkes Edition illustrated, reprint Publisher Wiley-Blackwell, 1995 ISBN 0-631-19807-5, ISBN 978-0-631-19807-9 p.278

- D. Dečev (Charakteristik der thrakischen Sprache 113 )

- E. Çabej (VII Congresso intemacionale di scienze onomastiche, 4-8 Aprile 1961, 248-249)

- The Illyrians The Peoples of Europe Author John Wilkes Edition illustrated, reprint Publisher Wiley-Blackwell, 1995 ISBN 0-631-19807-5, ISBN 978-0-631-19807-9 p.278–279

- The position of Albanian by Eric Hamp Ancient Indo-European Dialects. Publisher University of California Press p. 105

- Eric Hamp. Birnbaum, Henrik; Puhvel, Jaan (eds.). The position of Albanian, Ancient IE dialects, Proceedings of the Conference on IE linguistics held at the University of California, Los Angeles, April 25–27, 1963.

- Orel, Vladimir E. (2000). "4.1.3.4". A Concise Historical Grammar of the Albanian Language. Brill. p. 258. ISBN 9004116478.

- Migrations and invasions in Greece and adjacent areas By Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond Edition: illustrated Published by Noyes Press, 1976 Original from the University of Michigan Digitized Jun 24, 2008ISBN 0-8155-5047-2, 978-0-8155-5047-1 "Illyrian has survived. Geography has played a large part in that survival; for the mountains of Montenegro and northern Albania have supplied the almost impenetrable home base of the Illyrian-speaking peoples. They were probably the first occupants, apart from nomadic hunters, of the Accursed Mountains and their fellow peaks, and they maintained their independence when migrants such as the Slavs occupied the more fertile lowlands and the highland basins. Their language may lack the cultural qualities of Greek, but it has equalled it in its power to survive and it too is adapting itself under the name of Albanian to the conditions of the modern world." p.163

- Thunman, Hahn, Kretschmer, Ribezzo, La Piana, Sufflay, Erdeljanovic and Stadtmüller view referenced at The position of Albanian by Eric Hamp Ancient Indo-European DialectsPublisher University of California Press p. 104

- Jireček view referenced at The position of Albanian by Eric Hamp Ancient Indo-European DialectsPublisher University of California Press p. 104

- Puscariu,Parvan, Capidan referenced at The position of Albanian by Eric Hamp Ancient Indo-European Dialects. Publisher University of California Press p. 104

- Weigand, as referenced in 'The position of Albanian' by Eric Hamp, Ancient Indo-European Dialects, University of California Press, p. 104

- Baric, as referenced in 'The position of Albanian,' Ancient Indo-European Dialects, p. 104

- Polybius. "2.11.15". Histories.

Of the Illyrian troops engaged in blockading Issa, those that belonged to Pharos were left unharmed, as a favour to Demetrius; while all the rest scattered and fled to Arbo

. - Polybius. "2.11.5". Histories (in Greek).

εἰς τὸν Ἄρβωνα σκεδασθέντες

. - Strabo (1903). "2.5 Note 97". Geography. Literally Translated, with Notes by H. C. Hamilton and W. Falconer. London.

The Libyrnides are the islands of Arbo, Pago, Isola Longa, Coronata, &c., which border the coasts of ancient Liburnia, now Murlaka

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Ptolemy. "III.13(12).23". Geography (in Greek).

- Giacalone Ramat, Anna; Ramat, Paolo, eds. (1998). The Indo-European languages. Rootledge. p. 481. ISBN 0-415-06449-X.

- "Illyria". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece & Rome. Vol. 4. Oxford University Press. 2010. p. 65. ISBN 9780195170726.

- Vasiliev, Alexander A. (1958) . History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453. Vol. 2 (Second ed.). p. 613.

- Cole, Jeffrey E., ed. (2011). "Albanians". Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 9. ISBN 9781598843026.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). "Illyrians". Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Facts On File. p. 414. ISBN 0816049645.

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium. "Ἀρβών". Ethnika kat' epitomen (in Greek).

πόλις Ἰλλυρίας. Πολύβιος δευτέρᾳ. τὸ ἐθνικὸν Ἀρβώνιος καὶ Ἀρβωνίτης, ὡς Ἀντρώνιος καὶ Ἀσκαλωνίτης

. - Encyclopedia of ancient Greece by Nigel Guy Wilson,page 597,Polybius' own attitude to Rome has been variously interpreted, pro-Roman, ...frequently cited in reference works such as Stephanus' Ethnica and the Suda. ...

- Hispaniae: Spain and the Development of Roman Imperialism, 218-82 BC by J. S. Richardson,In four places, the lexicographer Stephanus of Byzantium refers to towns and ... Artemidorus as source, and in three of the four examples cites Polybius.

- R. Elsie: Early Albania, a Reader of Historical Texts, 11th - 17th Centuries, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 3

- The wars of the Balkan Peninsula: their medieval origins G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series Authors Alexandru Madgearu, Martin Gordon Editor Martin Gordon Translated by Alexandru Madgearu Edition illustrated Publisher Scarecrow Press, 2008 ISBN 0-8108-5846-0, ISBN 978-0-8108-5846-6 It was supposed that those Albanoi from 1042 were Normans from Sicily, called by an archaic name (the Albanoi were an independent tribe from Southern Italy), p. 25

- The wars of the Balkan Peninsula: their medieval origins G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series Authors Alexandru Madgearu, Martin Gordon Editor Martin Gordon Translated by Alexandru Madgearu Edition illustrated Publisher Scarecrow Press, 2008 ISBN 0-8108-5846-0, ISBN 978-0-8108-5846-6 It was supposed that those Albanoi from 1042 were Normans from Sicily, called by an archaic name (the Albanoi were an independent tribe from Southern Italy). The following instance is indisputable. It comes from the same Attaliates, who wrote that the Albanians (Arbanitai) were involved in the 1078 rebellion of... p. 25

- Comnena, Anna. The Alexiad, Book IV.

- Thalloczy/Jirecek/Sufflay, Acta et diplomata res Albaniae mediae aetatis, Vindobonae, MCMXIII, I, 113 (1198).

- Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2003). "Fourteenth-century Albanian migration and the ‘relative autochthony’ of the Albanians in Epeiros. The case of Gjirokastër." Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 27. (1): 176. "The presence of Albanians in the Epeirote lands from the beginning of the thirteenth century is also attested by two documentary sources: the first is a Venetian document of 1210, which states that the continent facing the island of Corfu is inhabited by Albanians."

- Konstantin Jireček: Die Romanen in den Städten Dalmatiens während des Mittelalters, I, 42-44.

- Mirdita, Zef (1969). Iliri i etnogeneza Albanaca. Iz istorije Albanaca. Zbornik predavanja. Priručnik za nastavnike. Beograd: Zavod za izdavanje udžbenika Socijalističke Republike Srbije. pp. 13–14.

{{cite conference}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Robert Elsie, A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology and folk culture, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2001, ISBN 978-1-85065-570-1, p. 79.

- ^ "ALBANCI". Enciklopedija Jugoslavije 2nd ed. Vol. Supplement. Zagreb: JLZ. 1984. p. 1.

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/al.html

- Elsie, Robert (1986). "Paulus Angelus". Dictionary of Albanian Literature. New York/Westport/London: Greenwood Press. p. 4.

- William Bowden. "The Construction of Identities in Post-Roman Albania" in Theory & practice in late antique archaeology. Brill, 2003.

- Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 183. "We may begin with the Venetic peoples, Veneti, Carni, Histri and Liburni, whose language set them apart from the rest of the Illyrians."

- Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 81. "In Roman Pannonia the Latobici and Varciani who dwelt east of the Venetic Catari in the upper Sava valley were Celtic but the Colapiani of the Colapis (Kulpa) valley were Illyrians..."

- "Johann Thunmann: On the History and Language of the Albanians and Vlachs". Elsie.

- Thunmann, Johannes E. "Untersuchungen uber die Geschichte der Oslichen Europaischen Volger". Teil, Leipzig, 1774.

- Indo-European language and culture: an introduction By Benjamin W. Fortson Edition: 5, illustrated Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2004 ISBN 1-4051-0316-7, ISBN 978-1-4051-0316-9

- Stipčević, Alexander. Iliri (2nd edition). Zagreb, 1989 (also published in Italian as "Gli Illiri")

- NGL Hammond The Relations of Illyrian Albania with the Greeks and the Romans. In Perspectives on Albania, edited by Tom Winnifrith, St. Martin’s Press, New York 1992

- ^ Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture By J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1997 ISBN 1-884964-98-2, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5

- Thunman, Hahn, Kretschmer, Ribezzo, La Piana, Sufflay, Erdeljanovic and Stadtmuller referenced at Hamp see (The position of Albanian, E. Hamp 1963)

- Jireček as referenced at Hamp see (The position of Albanian, E. Hamp 1963)

- ^ Demiraj, Shaban. Prejardhja e shqiptarëve në dritën e dëshmive të gjuhës shqipe.(Origin of Albanians through the testimonies of the Albanian language) Shkenca (Tirane) 1999

- History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453 By Alexander A. Vasiliev Edition: 2, illustrated Published by Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1958 ISBN 0-299-80926-9, ISBN 978-0-299-80926-3 (page 613)

- History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries By Barbara Jelavich Edition: reprint, illustrated Published by Cambridge University Press, 1983 ISBN 0-521-27458-3, ISBN 978-0-521-27458-6 (page 25)

- The Indo-European languages By Anna Giacalone Ramat, Paolo Ramat Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1998 ISBN 0-415-06449-X, 9780415064491 (page 481)

- ^ Douglas Q. Adams (January 1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 9, 11. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

The Greek and Latin loans have undergone most of the far-reaching phonological changes which have so altered the shape of inherited words while Slavic and Turkish words do not show those changes. Thus Albanian must have acquired much of its present form by the time Slavs entered into Balkans in the fifth and sixth centuries AD borrowed words from Greek and Latin date back to before Christian era Even very common words such as mik "friend" (<Lat. amicus) or këndoj "sing" (<Lat. cantare) come from Latin and attest to a widespread intermingling of pre-Albanian and Balkan Latin speakers during the Roman period, roughly from the second century BC to the fifth century AD.

- Erik Hamp, The Position of Albanian, University of Chicago, ..Jokl's Illyrian-Albanian correspondences (Albaner §3a) are probably the best known. Certain of these require comment...

- ^ Çabej, E. "Die alteren Wohnsitze der Albaner auf der Balkanhalbinsel im Lichte der Sprache und der Ortsnamen," VII Congresso internaz. di sciense onomastiche, 1961 241-251; Albanian version BUShT 1962:1.219-227

- Çabej, Eqrem. Karakteristikat e huazimeve latine të gjuhës shqipe. (The characteristics of Latin Loans in Albanian language) SF 1974/2 (In German RL 1962/1) (13-51)

- Cimochowski, W. "Des recherches sur la toponomastique de l’Albanie," Ling. Posn. 8.133-45 (1960). On Durrës

- In Tosk /a/ before a nasal has become a central vowel (shwa), and intervocalic /n/ has become /r/. These two sound changes have affected only the pre-Slav stratum of the Albanian lexicon, that is the native words and loanwords from Greek and Latin (page 23) Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World By Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie Contributor Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie Edition: illustrated Published by Elsevier, 2008 ISBN 0-08-087774-5, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7

- The dialectal split into Geg and Tosk happened sometime after the region become Christianized in the fourth century AD; Christian Latin loanwords show Tosk rhotacism, such as Tosk murgu"monk" (Geg mungu) from Lat. monachus. (page 392) Indo-European language and culture: an introduction By Benjamin W. Fortson Edition: 5, illustrated Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2004 ISBN 1-4051-0316-7, ISBN 978-1-4051-0316-9

- The river Shkumbin in central Albania historically forms the boundary between those two dialects, with the population on the north speaking varieties of Geg and the population on the south varieties of Tosk. (page 23) Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World By Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie Contributor Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie Edition: illustrated Published by Elsevier,2008 ISBN 0-08-087774-5, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7

- See also Hamp 1963 The isogloss is clear in all dialects I have studied, which embrace nearly all types possible. It must be relatively old, that is, dating back into the post-Roman first millennium. As a guess, it seems possible that this isogloss reflects a spread of the speech area, after the settlement of the Albanians in roughly their present location, so that the speech area straddled the Jireček Line.

- ^ Fine, JA. The Early medieval Balkans. Univ. of Michigan Press, 1991. p.10.

- ^ Madgearu A, Gordon M. The wars of the Balkan peninsula. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. p.146.

- Turnock, David. The Making of Eastern Europe, from the Earliest Times to 1815. Taylor and Francis, 1988. p.137

- ^ Fine, JA. The Early medieval Balkans. Univ. of Michigan Press, 1991. p.11.

- ^ The Cambridge ancient history by John Boederman,ISBN 0-521-22496-9,2002,page 848

- The Illyrian Language

- Madgearu A, Gordon M. The wars of the Balkan peninsula. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. p.147.

- Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 278. "...likely identification seems to be with a Romanized population of Illyrian origin driven out by Slav settlements further north, the 'Romanoi' mentioned..."

- Jirecek, Konstantin. "The history of the Serbians" (Geschichte der Serben), Gotha, 1911

- V. Orel. Albanian Etymological Dictionary Brill, 1988, page X.

- I.I. Russu, Obârșia tracică a românilor și albanezilor. Clarificări comparativ-istorice șietnologice. Der thrakische Ursprung der Rumänen und Albanesen. Komparativ-historische und ethnologische Klärungen. Cluj-Napoca: Dacia 1995

- Schramm, Gottfried, Anfänge des albanischen Christentums: Die frühe Bekehrung der Bessen und ihre langen Folgen (1994).

- Madgearu A, Gordon M. The wars of the Balkan peninsula. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. p.151.

- Hamp, Eric (1980) It can be said to be related more closely to Baltic and Slavic than to anything else, and certainly not to be close to Thracian see http://www.lituanus.org/1993_2/93_2_05.htm

- Eric P. Hamp, University of Chicago, 1963 The Position of Albanian, "...we still do not know exactly where the Illyrian-Thracian line was, and NaissoV (Nis) is regarded by many as Illyrian territory."

- ^ Malcolm, Noel. "Kosovo, a short history". London: Macmillan, 1998, p. 22-40.

- ^ Fine, JA. The Early medieval Balkans. Univ. of Michigan Press, 1991. p.11.

- Eric P. Hamp, University of Chicago The Position of Albanian (Ancient IE dialects, Proceedings of the Conference on IE linguistics held at the University of California, Los Angeles, April 25–27, 1963, ed. By Henrik Birnbaum and Jaan Puhvel)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp. Early Medieval Balkans. p304 (glossary): "Albanians: An Indo-European people, probably descended from the ancient Illyrians, living now in Albania as well as in Greece and Yugoslavia.

- Eric P. Hamp, 1963, University of Chicago The Position of Albanian

- Five Roman emperors: Vespasian, Titus, Domitian, Nerva, Trajan, A.D. 69-117 - by Bernard William Henderson - 1969, page 278,"At Thermidava he was warmly greeted by folk quite obviously Dacians"

- The Geography by Ptolemy, Edward Luther Stevenson,1991,page 36

- ^ Ethnic continuity in the Carpatho-Danubian area by Elemér Illyés,1988,ISBN 0880331461,page 223

- ^ Madgearu, Alexandru and Gordon, Martin. The Wars of the Balkan Peninsula: Their Medieval Origins. Pages 146-147.

- Bowden (2004) harvtxt error: no target: CITEREFBowden2004 (help)

- ^ Curta (2013)

- ^ Wilkes (1996, pp. 278–9) harvtxt error: no target: CITEREFWilkes1996 (help)

- Jones (2002, pp. 43, 63)

- ^ Filipovski (2010)

- ^ Curta (2006, pp. 103–104)

- Wilkes (2013, p. 756) harvtxt error: no target: CITEREFWilkes2013 (help)

- Curta (2012)

- ^ Cruciani, F; La Fratta, R; Trombetta, B; Santolamazza, P; Sellitto, D; Colomb, EB; Dugoujon, JM; Crivellaro, F; et al. (2007). "Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (6): 1300–1311. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049. PMID 17351267.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) Also see Supplementary Data. - ^ Battaglia, V.; Fornarino, S; Al-Zahery, N; Olivieri, A; Pala, M; Myres, NM; King, RJ; Rootsi, S; et al. (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–30. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

- Bird, Steven (2007). "Haplogroup E3b1a2 as a Possible Indicator of Settlement in Roman Britain by Soldiers of Balkan Origin". Journal of Genetic Genealogy. 3 (2).

- ^ Semino; Passarino, G; Oefner, PJ; Lin, AA; Arbuzova, S; Beckman, LE; De Benedictis, G; Francalacci, P; et al. (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective" (PDF). Science. 290 (5494): 1155–59. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Cruciani, F; La Fratta, R; Santolamazza, P; Sellitto, D; Pascone, R; Moral, P; Watson, E; Guida, V; et al. (May 2004). "Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1014–1022. doi:10.1086/386294. PMC 1181964. PMID 15042509.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ Peričic; Lauc, LB; Klarić, IM; Rootsi, S; Janićijevic, B; Rudan, I; Terzić, R; Colak, I; et al. (2005). "High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations". Mol. Biol. Evol. 22 (10): 1964–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Martinez-Cruz B, Ioana M, Calafell F, Arauna LR, Sanz P, Ionescu R, Boengiu S, Kalaydjieva L, Pamjav H, Makukh H, Plantinga T, van der Meer JW, Comas D, Netea MG (2012). Kivisild T (ed.). "Y-chromosome analysis in individuals bearing the Basarab name of the first dynasty of Wallachian kings". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e41803. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741803M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041803. PMC 3404992. PMID 22848614.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Latest designations can be found on the website. In some articles this is described as I-P37.2 not including I-M26.

- Rootsi et al. (2004) Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe

- Peričić et al. (2005), High-Resolution Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations, Mol Biol Evol (October 2005) 22 (10): 1964-1975. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185

- ^ Cardos G., Stoian V., Miritoiu N., Comsa A., Kroll A., Voss S., Rodewald A. (2004 Romanian Society of Legal Medicine) Paleo-mtDNA analysis and population genetic aspects of old Thracian populations from South-East of Romania

- Novembre J. et al. (2008) Genes mirror geography within Europe, Nature doi:10.1038/nature07331

- Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (September 2002). "Albanian identities: myth and history". Indiana University Press: 74. ISBN 978-0-253-21570-3Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Peter, Mackridge. "Aspects of language and identity in the Greek peninsula since the eighteenth century". Newsletter of the Society Farsarotul, Vol, XXI & XXII, Issues 1 & 2. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

the "Pelasgian theory" was formulated, according to which the Greek and Albanian languages were claimed to have a common origin in Pelasgian, the Albanians themselves are Pelasgians... Needless to say, there is absolutely no scientific evidence to support any of theses theories.

- Bayraktar, Uğur Bahadır (December 2011). "Mythifying the Albanians : A Historiographical Discussion on Vasa Efendi's "Albania and the Albanians"". Balkanologie. 13 (1–2). Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Malcolm N (2002) "Myths of Albanian national identity: Some key elements". In Albanian identities, Schwandner-Sievers S, Fischer JB eds., Indiana University Press. p. 77

- Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (September 2002). "Albanian identities: myth and history". Indiana University Press: 77–79. ISBN 978-0-253-21570-3Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (September 2002). "Albanian identities: myth and history". Indiana University Press: 78–79. ISBN 978-0-253-21570-3.

...Such derivations, almost all of which would be rejected by modern scholars...

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - De Rapper, Gilles (2009). "Pelasgic Encounters in the Greek–Albanian Borderland: Border Dynamics and Reversion to Ancient Past in Southern Albania." Anthropological Journal of European Cultures. 18. (1): 60-61. “In 2002, another important book was translated from Greek: Aristides Kollias’ Arvanites and the Origin of Greeks, first published in Athens in 1983 and re-edited several times since then (Kollias 1983; Kolia 2002). In this book, which is considered a cornerstone of the rehabilitation of Arvanites in post- dictatorial Greece, the author presents the Albanian speaking population of Greece, known as Arvanites, as the most authentic Greeks because their language is closer to ancient Pelasgic, who were the first inhabitants of Greece. According to him, ancient Greek was formed on the basis of Pelasgic, so that man Greek words have an Albanian etymology. In the Greek context, the book initiated a ‘counterdiscourse’ (Gefou-Madianou 1999: 122) aiming at giving Arvanitic communities of southern Greece a positive role in Greek history. This was achieved by using nineteenth-century ideas on Pelasgians and by melting together Greeks and Albanians in one historical genealogy (Baltsiotis and Embirikos 2007: 130—431, 445). In the Albanian context of the 1990s and 2000s, the book is read as proving the anteriority of Albanians not only in Albania but also in Greece; it serves mainly the rehabilitation of Albanians as an antique and autochthonous population in the Balkans. These ideas legitimise the presence of Albanians in Greece and give them a decisive role in the development of ancient Greek civilisation and, later on, the creation of the modern Greek state, in contrast to the general negative image of Albanians in contemporary Greek society. They also reverse the unequal relation between the migrants and the host country, making the former the heirs of an autochthonous and civilised population from whom the latter owes everything that makes their superiority in the present day.”

- The Albanians, Henry Skene, Journal of the Ethnological Society of London (1848–1856)

- The wars of the Balkan Peninsula: their medieval origins G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series Authors Alexandru Madgearu, Martin Gordon Editor Martin Gordon Translated by Alexandru Madgearu Edition illustrated Publisher Scarecrow Press, 2008 ISBN 0-8108-5846-0, ISBN 978-0-8108-5846-6 It was supposed that those Albanoi from 1042 were Normans from Sicily, called by an archaic name (the Albanoi were an independent tribe from Southern Italy), p. 25,

- Michaelis Attaliotae: Historia, Bonn 1853, p. 8, 18, 297. Translated by Robert Elsie. First published in R. Elsie: Early Albania, a Reader of Historical Texts, 11th – 17th Centuries, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 4–5.

Sources

- Demiraj, Shaban (1999). "Prejardhja e shqiptarëve në dritën e dëshmive të gjuhës shqipe" (in Albanian). Shtëpia Botuese "Shkenca". OCLC 247109289Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Demiraj, Shaban (2006). The origin of the Albanians: linguistically investigated. Academy of Sciences of Albania. ISBN 978-99943-817-1-5.

- Jones, Sian (2002). The Archaeology of Ethnicity: Constructing Identities in the Past and Present. Routledge. ISBN 0203438736.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521815398.

- William Bowden (2004). "Balkan Ghosts? Nationalism and the Question of Rural Continuity in Albania". In Neil Christie (ed.). Landscapes of Change: Rural Evolutions in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 1840146176.

- John Wilkes (2013). "The Archaeology of War: Homeland Security in the Southwest Balkans (3rd-6th century AD)". In Alexander Sarantis; Neil Christie (eds.). War and Warfare in Late Antiquity: Current Perspectives. Brill. ISBN 9004252584.

- Curta, Florin (2013). "Seventh-century fibulae with bent stem in the Balkans". Archaeologia Bulgarica. 17: 49–70{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Curta, Florin (2012). "Were there any Slavs in seventh-century Macedonia?". Istorija (Skopje). 47: 61–75{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); line feed character in|journal=at position 9 (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Filipovski, Toni (2010). "The Komani-Krue Settlements, and Some Aspects of their Existence in the Ohrid-Struga Valley (VII-VIII century)". Macedonian Historical Review. 1{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Szczepanski W. (2005). "Some Controversies Connected with the Origin of the Albanians, Their Territorial Cradle and Ethnonym". Sprawy Narodowościowe – Seria Nowa (26): 81–96.