This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Adakiko (talk | contribs) at 19:50, 2 January 2025 (Reverted edits by 2601:243:2280:4440:ED25:C5C5:4213:B31F (talk): not providing a reliable source (WP:CITE, WP:RS) (HG) (3.4.13)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:50, 2 January 2025 by Adakiko (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 2601:243:2280:4440:ED25:C5C5:4213:B31F (talk): not providing a reliable source (WP:CITE, WP:RS) (HG) (3.4.13))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Former population control policy in China

The one-child policy (Chinese: 一孩政策; pinyin: yī hái zhèngcè) was a population planning initiative in China implemented between 1979 and 2015 to curb the country's population growth by restricting many families to a single child. The program had wide-ranging social, cultural, economic, and demographic effects, although the contribution of one-child restrictions to the broader program has been the subject of controversy. Its efficacy in reducing birth rates and defensibility from a human rights perspective have been subjects of controversy.

China's family planning policies began to be shaped by fears of overpopulation in the 1970s, and officials raised the age of marriage and called for fewer and more broadly spaced births. A near-universal one-child limit was imposed in 1980 and written into the country's constitution in 1982. Numerous exceptions were established over time, and by 1984, only about 35.4% of the population was subject to the original restriction of the policy. In the mid-1980s, rural parents were allowed to have a second child if the first was a daughter. It also allowed exceptions for some other groups, including ethnic minorities under 10 million people. In 2015, the government raised the limit to two children, and in May 2021 to three. In July 2021, it removed all limits, shortly after implementing financial incentives to encourage individuals to have additional children.

Implementation of the policy was handled at the national level primarily by the National Population and Family Planning Commission and at the provincial and local level by specialized commissions. Officials used pervasive propaganda campaigns to promote the program and encourage compliance. The strictness with which it was enforced varied by period, region, and social status. In some cases, women were forced to use contraception, receive abortions, and undergo sterilization. Families who violated the policy faced large fines and other penalties.

The population control program had wide-ranging social effects, particularly for Chinese women. Patriarchal attitudes and a cultural preference for sons led to the abandonment of unwanted infant girls, some of whom died and others of whom were adopted abroad. Over time, this skewed the country's sex ratio toward men and created a generation of "missing women". However, the policy also resulted in greater workforce participation by women who would otherwise have been occupied with childrearing, and some girls received greater familial investment in their education.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) credits the program with contributing to the country's economic ascendancy and says that it prevented 400 million births, although some scholars dispute that estimate. Some have also questioned whether the drop in birth rate was caused more by other factors unrelated to the policy. In the West, the policy has been widely criticized for perceived human rights violations and other negative effects.

Background

See also: Family planning policies of China, Chinese economic reform, and Boluan Fanzheng

Since the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, socialist construction was the utmost mission the state needed to accomplish. Top state leaders believed that having more population would effectively contribute to the national effort.

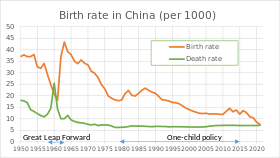

During Mao Zedong's leadership in China, the birth rate fell from 37 per thousand to 20 per thousand. Infant mortality declined from 227 per thousand births in 1949 to 53 per thousand in 1981, and life expectancy dramatically increased from around 35 years in 1948 to 66 years in 1976. Until the 1960s, the government mostly encouraged families to have as many children as possible, especially during the Great Leap Forward, because of Mao's belief that population growth empowered the country, preventing the emergence of family planning programs earlier in China's development. The state tried to incentivize more childbirths during that time with a variety of policies, such as the "Mother Heroine" award, a programme inspired by a similar policy in the Soviet Union. As a result, the population grew from around 540 million in 1949 to 940 million in 1976. Beginning in 1970, citizens were encouraged to marry at later ages and many were limited to have only two children.

Although China's fertility rate plummeted faster than anywhere else in the world during the 1970s under these restrictions, the Chinese government thought it was still too high, influenced by the global debate over a possible overpopulation crisis suggested by organizations such as the Club of Rome and the Sierra Club. The fertility rate dropped from 5.9 in the 1950s to 4.0 in the 1970s. Yet, the population still grew at a significant rate. There were approximately 541,670,000 people in China in the year 1949. The number then went up to 806,710,000 in 1969.

In the early 1970s, the state introduced a set of birth planning policies. It mainly called for later childbearing, longer time spans between having new children, and giving birth to fewer children. Men were encouraged to marry at age 25 or later, and women were encouraged to marry at age 23 or later.The authorities began encouraging one-child families in 1978, and in 1979 announced that they intended to advocate for one-child families. Ma Yinchu, a founder of China's population planning theory, was also an intellectual architect of the policy. In the late spring of 1979, Chen Yun became the first senior leader to propose the one-child policy. On 1 June 1979, Chen said that:

Comrade Xiannian proposed to me planning "better one, at most two". I'd say be stricter, stipulating that "only one is allowed". Prepare to be criticized by others for cutting off the offspring. But if we don't do it, the future looks grim.

Deng Xiaoping, then paramount leader of China, supported the policy, along with other senior leaders including Hua Guofeng and Li Xiannian. On 15 October 1979, Deng met a British delegation led by Felix Greene in Beijing, saying that "we encourage one child per couple. We give economic rewards to those who promise to give birth to only one child."

Formulation of the policy

In 1980, the central government organized a meeting in Chengdu to discuss the speed and scope of one-child restrictions. The notable aerospace engineer Song Jian was a participant at the Chengdu meeting. He had previously read two influential books about population concerns, The Limits to Growth and A Blueprint for Survival, while visiting Europe in 1980. Along with several associates, Song determined that the ideal population of China was 700 million, and that a universal one-child policy for all would be required to meet that goal. If fertility rates remained constant at 3 births per woman, China's population would surpass 3 billion by 2060 and 4 billion by 2080. In spite of some criticism inside the CCP, the family planning policy, was formally implemented as a temporary measure on 18 September 1980. The plan called for families to have one child each in order to curb a then-surging population and alleviate social, economic, and environmental problems in China.

"Virtual" population crisis

Despite the legitimate ongoing rapid growth of China's population and the evident effects it brought to society, using the term "population crisis" to describe the situation is disputed. Scholars including Susan Greenhalgh argue that the state intentionally created a virtual population crisis in order to serve political ends. According to state promotions, the looming overpopulation crisis would ruin the national agenda of achieving "China's socialist modernization", which includes industry, agriculture, national defense, and technology.

China's attitude towards population control on the global stage in international forums evidenced an ambiguous stance on the nature of the crisis. In the mid-1960s, when global movements for birth control emerged, Chinese delegates expressed their opposition toward population control. In the first UN-organized World Population Conference held in Bucharest in 1969, they claimed that it was an imperialist agenda that Western countries imposed on Third World countries, and that population was not a determining factor of economic growth and a country's well-being. Yet, in the domestic setting the state leaders were already wary of the perceived "population crisis" that was thought to endanger the modernization of China.

It is also suggested that mathematical terms, graphs, and tables were utilized to form a convincing narrative that presents the urgency of the population problem as well as justifies the necessity of mandatory birth control across the nation. Due to the previous traumas of the Cultural Revolution, public and top state leaders turned to the charisma of science, and sometimes blindly worshipped it as the solution to every problem. As a result, any proposal that was veiled and decorated by the so-called scientific back-ups would be highly considered by both the people and the state.

Arguments started to come out in 1979 suggesting that the excessively rapid population growth was sabotaging the economy and destroying the environment, and essentially preventing China from being a rightful member of the global world. Skillful and deliberate comparisons were made with developed and industrialized countries such as the United States, Japan, and France. Under such a comparison, China's relatively low income per capita was attributed directly to population growth and no other factors. Though the data is truthful, its arrangement and presentation to readers gave a single message determined by the state: that the population problem is a national catastrophe and immediate remedy is desperately needed.

Chinese population science

China was deprived of data, skills, and state support to conduct population studies. Due to Mao's ambivalent attitude toward the population issue, population studies were abolished in the late 1950s. After Mao's death, family planning became a critical component and premise for reaching China's national goal: that is, to achieve "China's socialist modernization," which includes modernizing industry, agriculture, national defence, and technology. Therefore, at this point, population science was closely related and tied with state politics. There was a perceived need to redefine population as a domain of science, identify the population problem in China, and propose a solution to it. Such efforts included many groups of people with diverse backgrounds. Among these experts, two groups held the most influence in defining the population problem and providing a solution to it. They were a group of scientists led by Liu Zheng, and another group led by Song Jian. Liu's group mainly came from a social science background, while Song's group came from natural science background.

Social scientists

Social scientists involved in this discussion in the mid-1970s, including Liu Zheng, Wu Cangping, Lin Fude, and Zha Ruichuan, prioritized the Marxist formulation of the population problem. They saw the problem as an "imbalance between economic and demographic growth," and wished to design a reasonable policy that considered the social consequences. These scientists came from the fields of social science, statistics, genetics, history, and many others. However, they had limited access to resources compared to the natural scientists who became involved in population policy making in 1978. Since population studies were forbidden from the 1950s until 1979, population science had made no progress between these two decades.

Natural scientists

Natural scientists were interested in using control theory and applying it to the actual policy. The leader of the group, Song Jian, was a control theorist at the Ministry of Aerospace Industry. He was known for his career in missile science. Yu Jingyuan and Li Guangyuan were trained engineers in the field of cybernetics. Compared to the social scientists, this group of natural scientists had numerous advantages. They were politically protected during the Maoist period due to their importance in national defense and technology. They also had access to Western science. Eventually, they took an important role in examining the population model as well as designing the details of one-child policies. After quantitative research and analysis, they showed the top state leaders that the only solution would be a policy "to encourage all couples to have only one child, regardless of the costs to individuals and society".

Although Greenhalgh claims that Song Jian was the central architect of the one-child policy and that he "hijacked" the population policy making process, that claim has been refuted by several leading scholars, including Liang Zhongtang, a leading internal critic of one-child restrictions and an eye-witness at the discussions in Chengdu. In the words of Wang et al., "the idea of the one-child policy came from leaders within the Party, not from scientists who offered evidence to support it." Central officials had already decided in 1979 to advocate for one-child restrictions before knowing of Song's work and, upon learning of his work in 1980, already seemed sympathetic to his position.

History

The one-child policy was originally designed to be a "One-Generation Policy". It was enforced at the provincial level and enforcement varied; some provinces had more relaxed restrictions. The one-child limit was most strictly enforced in densely populated urban areas. When this policy was first introduced, 6.1 million families that had already given birth to a child were given "One Child Honorary Certificates". This was a pledge they had to make to ensure they would not have more children.

Beginning in 1980, the official policy granted local officials the flexibility to make exceptions and allow second children in the case of "practical difficulties" (such as cases in which the father was a disabled serviceman) or when both parents were single children, and some provinces had other exemptions worked into their policies as well. In most areas, families were allowed to apply to have a second child if their first-born was a daughter. By 1984, only approximately 35.4% of the population fell within the policy's original restriction.

Furthermore, families with children with disabilities have different policies and families whose first child suffers from physical disability, mental illness, or intellectual disability were allowed to have more children. However, second children were sometimes subject to birth spacing (usually three or four years). Children born overseas were not counted under the policy if they did not obtain Chinese citizenship. Chinese citizens returning from abroad were allowed to have a second child. Sichuan province allowed exemptions for couples of certain backgrounds. By one estimate there were at least 22 ways in which parents could qualify for exceptions to the law towards the end of the one-child policy's existence.

In 1991, the central government made local governments directly responsible for family planning goals. Also in the early 1990s, experts from leading population-research institutes began appealing to policymakers to relax or end the one-child policy.

As of 2007, only 36% of the population were subjected to a strict one-child limit. 53% were permitted to have a second child if their first was a daughter; 9.6% of Chinese couples were permitted two children regardless of their gender; and 1.6% – mainly Tibetans – had no limit at all.

Following the devastating 2008 Sichuan earthquake, a new exception to the regulations was announced in Sichuan for parents who had lost children in the earthquake. Similar exceptions had previously been made for parents of severely disabled or deceased children. People have also tried to evade the policy by giving birth to a second child in Hong Kong, but at least for Guangdong residents, the one-child policy was also enforced if the birth took place in Hong Kong or abroad.

In accordance with China's affirmative action policies towards ethnic minorities, all non-Han ethnic groups were subject to different laws and were usually allowed to have two children in urban areas, and three or four in rural areas. Han Chinese living in rural towns were also permitted to have two children. Because of couples such as these, as well as those who simply paid a fine (or "social maintenance fee") to have more children, the overall fertility rate of mainland China was close to 1.4 children per woman as of 2011.

On 6 January 2010, the former National Population and Family Planning Commission issued the "national population development" 12th five-year plan.

On 1 January 2016, the one-child policy was replaced by the two-child policy.

Enforcement

The one-child policy was managed by the National Population and Family Planning Commission under the central government since 1981. The Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China and the National Population and Family Planning Commission were made defunct and a new single agency, the National Health and Family Planning Commission, took over national health and family planning policies in 2013. The agency reports to the State Council.

The policy was enforced at the provincial level through contraception, abortion, and fines that were imposed based on the income of the family and other factors. Population and Family Planning Commissions existed at every level of government to raise awareness and carry out registration and inspection work. The fine was a so-called "social maintenance fee", the punishment for the families who had more than one child. According to the policy, families who violated the law created a burden on society. Therefore, social maintenance fees were to be used for the operation of the government.

The 2019 documentary One Child Nation portrayed the experiences of enforcement, primarily focusing on rural China. Enforcement of the one-child policy was more uneven in rural China.

Financial

The Family Planning Policy was enforced through a financial penalty in the form of the "social child-raising fee," sometimes called a "family planning fine" in the West, which was collected as a fraction of either the annual disposable income of city dwellers or of the annual cash income of peasants, in the year of the child's birth. For instance, in Guangdong, the fee was between three and six annual incomes for incomes below the district's per capita income, plus one to two times the annual income exceeding the average. Families were required to pay the fine.

The one-child policy was a tool for China to not only address overpopulation, but to also address poverty alleviation and increase social mobility by consolidating the combined inherited wealth of the two previous generations into the investment and success of one child instead of having these resources spread thinly across multiple children. This theoretically allowed for a "demographic dividend" to be realized, increasing economic growth and increasing gross national income per capita.

If the family was not able to pay the "social child-raising fee", then their child would not be able to obtain a hukou, a legal registration document that was required in order to marry, attend state-funded schools, or to receive health care. Many who were unable to pay the fee never attempted to obtain their hukou for fear that the government would force extra fees upon them. Although some provinces had declared that payment of the "social child-raising fee" was not required to obtain a hukou, most provinces still required families to pay retroactive fines after registration.

Contraception and sterilization

Since the 1970s, the intrauterine device (IUD) has been one of the most widely promoted and practiced forms of contraception. It was the primary alternative to sterilization. As directed, the IUD was medically implanted into women in their child-bearing years to prevent pregnancies, thus out of order births. In the 1980s, women either had to receive an IUD after giving birth to their first child, or the husband would have to undergo a vasectomy. Between 1980 and 2014, 324 million Chinese women received IUDs and 108 million were sterilized. By law, the IUD was placed four months after the delivery of the first child. It was only medically removed after permission to conceive is granted by the community based upon various laws and policies on childbirth quotas. Despite this, some midwives illegally removed the device from their patients. This led to IUD inspections, ensuring that the IUD remained in place. Permanent legal removal of IUDs happens once a woman reaches menopause. In 2016 as means of loosening restrictions and abolishing the one-child policy, the Chinese government now covers the price of IUD removals.

The most widely used alternative to IUDs has been sterilization. As the leading form of contraception in China, sterilization has included both tubal ligation and vasectomy. Starting in the early 1970s, massive sterilization campaigns swept across the country. Urban and rural birth planning and family planning services situated themselves in every community. Cash payments or other material rewards and fines acted as incentives, increasing the number of participants. Socially willing participants were considered role models in the community. In 1983 mandatory sterilization occurred after the birth of the second or third child. As the restrictions tightened a few years later, if a woman gave birth to two children, legally she had to be sterilized. Alternatively, in some cases her husband could be sterilized in her place. In other cases, sterilization of surplus children occurred.

In the early years of the sterilization campaigns, abortion was a method of birth control highly encouraged by family planning. With 55 percent of abortion recipients as repeat customers and the procedure easily accessible, women had chosen to abort and had been forced to abort because of laws, social pressure, discovery of secret pregnancy, and community birth quotas. In 1995, the People's Republic of China (PRC) warned against abortion as a means of family planning and as a contraceptive. Should an abortion be required, the woman was to have a safe procedure done by a registered physician. Despite this, some women even in the 2000s chose or were encouraged to use traditional abortive products such as blister beetles, also known as Mylabris. Women would ingest the toxins orally or by means of douching with the hopes of inducing abortion. An overdose could lead to death of the mother and fetus. The efficacy of these products has been very low with a high mortality rate. The medical community and PRC have warned against use of these traditional methods.

The priorities of individual families also played a role in the birth rate. Families debated the social and economic stability of the household prior to conception. Some families chose to follow the single-child limit due to varying social and economic factors such as marrying later, spacing out children, the cost of raising a child, the fines for having multiple children, birth control policies, and the accessibility of contraceptives. In addition, those who violated the one-child policy could lose their jobs, their titles, a portion of medical insurance, and opportunities for higher education for the second child; they could also face sterilization and the labeling of the second child as a "black child". All of the variables played an important role in couples' decisions on when to conceive, placing their social and economic situation above the desire to bear additional children.

Other examples of contraceptives have included the morning-after pill, birth control pills, and condoms. The morning-after pill has made up 70 percent of oral contraceptives in the Chinese market. Only seven percent of Chinese women had shared that they use the pill and condom in combination. The Chinese government promoted the use of IUDs and sterilization over the combined pill and condom because PRC authorities questioned the voluntary commitment of the public. The Chinese government has distributed free condoms at medical clinics and health centers to adults with proof that they are 18 years of age or older. Additionally, the rate and highly debated sexual education have increased awareness of sex and contraceptive measures among groups of China's young population, further lowering the birth rate.

Evasion

Some couples paid fines to have a second or third child, and others would attempt to circumvent the policy by having non-pregnant friends take the mandatory blood tests.

Propaganda

The National Family Planning committee developed the slogan Wan Xi Shao ('later, longer, and fewer'), which was first enacted in 1973 and was in effect until 1979. This national idea encouraged later marriages and having fewer children. However, this policy was not effective at enforcing the developing ideal of having fewer children since it was such a new concept that had never been seen in other regions of the world. The various problems that arose during its introduction were slowly addressed and it became progressively more targeted to corner women into limited control over their own bodies.

The Wan Xi Shao slogan emerged during the 1970s as a response to China's rapid population growth, which was viewed as a major obstacle to the country's economic and social development. This slogan encapsulated three key principles: marrying later (wan, 晚), spacing pregnancies farther apart (xi, 稀), and having fewer children (shao, 少) and was emblematic of China's national campaign of mandatory birth planning. The Chinese government aimed to reduce population growth by promoting guidelines for birth control and family planning. The government believed that having fewer children and spacing births more adequately would allow families to allocate more resources per child, resulting in better health and education outcomes for children. The policy aimed to achieve this by allowing parents more time and resources to invest in each child's health and education, as they would have fewer children to care for.

The "later, longer, fewer" campaign was later replaced by the one-child policy. According to Whyte and colleagues, many of the coercive techniques that became notorious after the one-child policy was launched actually date from this campaign in the 1970s.

During the campaign, the state bureaucracy was in charge of enforcing birth control and oversaw birth-planning workers in every village, urban work unit, and neighborhood. These workers kept detailed records on women of child-bearing age, including past births, contraceptive usage, and menstrual cycles, often becoming "menstrual monitors" to detect out-of-quota pregnancies. In some factories, there were quotas for reproduction, and women who did not receive a birth allotment were not supposed to get pregnant.

Women who became pregnant without permission were harassed to get an abortion, with pressure also put on their husbands and other family members. Families were threatened that, if they persisted in having an over-quota birth, the baby would be denied household registration, which would mean denial of ration coupons, schooling, and other essential benefits that depended upon registration. In rural areas, women who gave birth to a third child were pressured to get sterilized or have IUDs inserted, while urban women were trusted to continue using effective contraception until they were no longer fertile.

Official statistics show that birth control operations, including abortions, IUD insertions, and sterilizations, increased sharply during the 1970s in association with the campaign to enforce birth limits. These drastic increases in birth-control operations suggest that highly coercive birth planning enforcement was already prevalent in both rural and urban areas, preceding the launch of the one-child policy. However, during the 1970s, the Chinese government was still concerned that the Wan Xi Shao policy would not reduce the growing population sufficiently. They felt the population would grow too fast to be supported, and a one-child policy for all families was introduced in 1979.

Many of the tactics used by the government were reflected in the day-to-day life of the average Chinese citizen. Since the Chinese government could not outright force its inhabitants to follow strict policy orders, the government developed strategies to encourage and promote individuals to take on this responsibility themselves. A common technique was placing an emphasis on family bonds and how having one child per family would increase emotional ties in parent-offspring relationships as well as extended family giving all their attention to fewer children. While the message of population reduction was urgent and required immediate attention, it was more important for the government to stop conception and new pregnancies. The Family Planning Commission spread propaganda by placing pictures and images on everyday items. Aside from signs and posters on billboards, advertisements were placed on postage stamps, milk cartons, food products and many other household items to promote the benefits of having one child.

Propaganda took many forms throughout the one-child policy era and was able to target a wide range of age demographics. Children born in this time period spent most of their lives being exposed to the new expectations placed on them by society. Educational programs were also encouraged to promote one-child policy expectations. Many young teenagers were required to read Renkou Jiayu (1981), which emphasized the importance of family planning and birth control measures that would ensure the stability of the nation. Younger generations became the main target audience for much of the propaganda as the one-child policy continued, since they made up a large portion of the population that would contribute to continued growth if no policy was put in place.

The one-child campaign extensively used propaganda posters. The aim of the posters was to promote the policy, encourage compliance, and emphasize the benefits of having fewer children. Many of the posters were educational in nature, paying attention to reproduction, sexuality, and conception. They were produced by various government departments, ranging from ministries of health to local population policy centers.

To convey the idea that couples should only have one child, the one-child campaign utilized traditional visual elements from nianhua (New Year prints) that were popular among the people. Traditionally, these prints employ visual symbols to convey good wishes for the coming new year. In the prints, young children often have been portrayed with pink, chubby cheeks to symbolize the success of family reproduction and a hopeful future. Even without slogans, these pictures were effective in establishing a link between luck and prosperity associated with the New Year and the one-child policy. Traditional elements like chubby, healthy-looking babies resonated with people – making them believe that compliance with the policy would yield luck, good fortune, and healthy offspring. As the one-child campaign progressed, the policy was linked to national development and wealth. It was considered directly linked to the success of the policy of modernization and reform.

By promoting the one-child policy on a daily basis, the government was able to convince the people that it was their duty to fulfill this nationalistic pride. Once the idea and initial steps of this policy were introduced into society, it was regulated by local policy enforcers until finally becoming an internal obligation the community accepted for the greater good of maintaining a nation. In many cases, health centers encouraged the idea of reducing the risks of pregnancy by distributing various forms of contraceptives at no cost, which made protected sex more common than unprotected sex.

Material incentives

Couples who only had one child received healthcare subsidies (baojian fei), retirement funds, and larger grain allowances.

Relaxation

In 2013, Deputy Director Wang Peian of the National Health and Family Planning Commission said that "China's population will not grow substantially in the short term." A survey by the commission found that only about half of eligible couples wish to have two children, mostly because of the cost of living impact of a second child.

In November 2013, following the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), China announced the decision to relax the one-child policy. Under the new policy, families could have two children if one parent, rather than both parents, was an only child. This mainly applied to urban couples, since there were very few rural, only children due to long-standing exceptions to the policy for rural couples. Zhejiang, one of the most affluent provinces, became the first area to implement this "relaxed policy" in January 2014, and 29 out of the 31 provinces had implemented it by July 2014, with the exceptions of Xinjiang and Tibet. Under this policy, approximately 11 million couples in China were allowed to have a second child; however, only "nearly one million" couples applied to have a second child in 2014, less than half the expected number of 2 million per year. By May 2014, 241,000 out of 271,000 applications had been approved. Officials of China's National Health and Family Planning Commission claimed that this outcome was expected, and that the "second-child policy" would continue progressing with a good start.

Abolition

See also: Two-child policy § People's Republic of ChinaIn October 2015, the Chinese news agency Xinhua announced the government's plans to abolish the one-child policy, now allowing all families to have two children, citing a communiqué issued by the CCP "to improve the balanced development of population" – an apparent reference to the country's female-to-male sex ratio – and to deal with an aging population. The new law took effect on 1 January 2016 after it was passed in the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress on 27 December 2015.

The rationale for the abolition was summarized by former Wall Street Journal reporter Mei Fong: "The reason China is doing this right now is because they have too many men, too many old people, and too few young people. They have this huge crushing demographic crisis as a result of the one-child policy. And if people don't start having more children, they're going to have a vastly diminished workforce to support a huge aging population." China's ratio is about five working adults to one retiree; the huge retiree community must be supported, and that will dampen future growth, according to Fong. Since the citizens of China are living longer and having fewer children, the growth of the population imbalance is expected to continue. A United Nations projection forecast that "China will lose 67 million working-age people by 2030, while simultaneously doubling the number of elderly. That could put immense pressure on the economy and government resources." The longer-term outlook is also pessimistic, based on an estimate by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, revealed by Cai Fang, deputy director. "By 2050, one-third of the country will be aged 60 years or older, and there will be fewer workers supporting each retired person."

Although many critics of China's reproductive restrictions approved of the policy's abolition, Amnesty International said that the move to the two-child policy would not end forced sterilizations, forced abortions, or government control over birth permits. Others had also stated that the abolition was not a sign of the relaxation of authoritarian control in China. A reporter for CNN said, "It was not a sign that the party will suddenly start respecting personal freedoms more than it has in the past. No, this is a case of the party adjusting policy to conditions. The new policy, raising the limit to two children per couple, preserves the state's role."

The abolition having a significant benefit was uncertain, as a CBC News analysis indicated: "Repealing the one-child policy may not spur a huge baby boom, however, in part because fertility rates are believed to be declining even without the policy's enforcement. Previous easings of the one-child policy have spurred fewer births than expected, and many people among China's younger generations see smaller family sizes as ideal." The CNN reporter added that China's new prosperity was also a factor in the declining birth rate, saying, "Couples naturally decide to have fewer children as they move from the fields into the cities, become more educated, and when women establish careers outside the home."

The Chinese government had expected the abolition of the one-child rule would lead to an increase in births to about 21.9 million births in 2018. The actual number of births was 15.2 million – the lowest birth rate since 1961.

On 31 May 2021, China's government relaxed restrictions even more, allowing women up to three children. This change was brought about mainly due to the declining birth rate and population growth. Although the Chinese government was trying to spark new growth in the population, some experts did not think it would be enough. Many called for the government to remove the limit altogether, though most women and couples already had adopted the idea that one child is enough and to have more is not in their best interest. Because of this new belief, the population would be likely to keep declining, which could have tragic repercussions for China in the coming decades.

All restrictions were lifted on 26 July 2021, thus allowing Chinese couples to have any number of children. In 2022, the number of births in China hit another record low of 9.56 million births, the first time the number had dipped below 10 million since the late 1940s according to China Daily. 9.02 million births took place in 2023. Falling numbers of women of childbearing age and reluctance of young women to have children had reduced the China's fertility rate to close to 1.0 by 2024 (a fertility rate of 2.1 is needed for a stable population). A study by the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences and Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia forecast China's population would be 525 million in 2100 compared to 1.4 billion in 2024. In September 2024 China announced the retirement age would be raised as from January 2025 as there were too few young people and a growing senior population.

Public responses

In addition to stories of resistance to the policy and official reasons for support such as strengthening China, academic Sarah Mellors Rodriguez describes a surprising number of accounts from her fieldwork in which interviewees fully supported the mandate for personal reasons. According to Mellors Rodriguez, for some couples the policy affirmed their own personal beliefs that having smaller families was wiser and more economical.

Urban responses

China's urban population generally accepted the policy, given the already crowded circumstances and shortage of housing in cities. Incentives offered by the state also were effective to make the urban population compliant with the newly introduced family planning. Families that signed the single-child pledge and met the requirements of having only one child were given access to housing and daycare, while non-compliant ones would receive penalties. Examples are obstructing the parents' careers and delaying the payment of their salaries.

In her fieldwork interviews, Mellors Rodriguez found that middle income urbanites were more receptive to the limitations of the policy because they generally believed that having one child and providing them with all possible opportunities was more important than having additional heirs. Long-term urban residents also reported that supporting multiple children was expensive and burdensome.

Rural responses

The rural population was more resistant to the policy and variations upon the policy were permitted. Mothers of a daughter in several rural provinces were allowed to have a single additional child (a "1.5-child" policy) and families in remote areas a second or third child. After collective co-ops were dismantled and decollectivization took place, children became more valued by their parents, as a source of agricultural production, and as a source of the care required by ageing parents. Due to the inherently patrilocal nature of marriage, it was expected that daughters would leave their parents and contribute labor to their husbands' households. The consequent preference for sons came into conflict with the one-child policy and government enforcement of this policy.

Coercive enforcement measures were taken, and included abortions of "over-quota" pregnancies, and sterilization of women. This led to a series of physical conflicts with the government cadres who were assigned to enforce the policy in a specific rural area. Rural families wished to add sons to their families in order to contribute to agricultural production. But the cadres came on the way in conflict with them. Many cadres were middle-aged women who went through the collective period when childbearing was encouraged. They experienced continuous childbearing, and so were strongly supportive of the one-child policy. When these two distinct groups disapproved of each other, conflicts came. More than that, rural families that were desperate to have a son would abuse women who could not give birth to one. They also abandoned infant girls and even engaged in infanticide. As a result, societal relationships were tense within families and also between the cadres and people.

Since the 1990s, rural policy violations decreased sharply. Anthropologist Yan Yunxiang attributes this decrease to greater acceptance of family planning among the new generation of parents, as well as their increased prioritization of material comforts and individual happiness.

Effects

Population

Below are the results of the first three National Population Census of the People's Republic of China (中华人民共和国全国人口普查). The first two censuses date back to the 1950s and 1960s, and the last one in the 1980s. They were conducted in 1953, 1964, and 1982 respectively.

| 1st Census (1953) | 2nd Census (1964) | 3rd Census (1982) | |

| Total population | 601,938,035 | 723,070,269 | 1,031,882,511 |

| Male population (proportion of total) | 297,553,518

(51.82%) |

356,517,011

(51.33%) |

519,433,369

(51.5%) |

| Female population (proportion of total) | 276,652,422

(48.18%) |

338,064,748

(48.67%) |

488,741,919

(48.5%) |

Below are the results of population investigation after the implementation of one-child policy.

| 4th Census (1990) | 2005 Population Sample Survey

(2005年全国1%人口抽样调查) |

6th Census (2010) | |

| Total population | 1,160,017,381 | 1,306,280,000 | 1,370,536,875 |

| Male population (proportion of total) | 584,949,922

(51.6%) |

673,090,000

(51.53%) |

686,852,572

(51.27% ) |

| Female population (proportion of total) | 548,732,579

(48.4%) |

633,190,000

(48.47%) |

652,872,280

(48.73%) |

Fertility reduction

The total fertility rate in China continued its fall from 2.8 births per woman in 1979 (already a sharp reduction from more than five births per woman in the early 1970s) to 1.5 by the mid-1990s. Some scholars claim that this decline is similar to that observed in other places that had no one-child restrictions, such as Thailand as well as the Indian states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, a claim designed to support the argument that China's fertility might have fallen to such levels anyway without draconian fertility restrictions.

According to a 2017 study in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, "the one-child policy accelerated the already-occurring drop in fertility for a few years, but in the longer term, economic development played a more fundamental role in leading to and maintaining China's low fertility level". However, a more recent study found that China's fertility decline to very low levels by the mid-1990s was far more impressive given its lower level of socio-economic development at that time; even after taking rapid economic development into account, China's fertility restrictions likely averted over 500 million births between 1970 and 2015, with the portion caused by one-child restrictions possibly totaling 400 million. Fertility restrictions also had unintended consequences such as a deficit of 40 million female babies, most of which was due to sex-selective abortion, and the accelerated aging of China's population.

Disparity in sex ratio at birth

The sex ratio of a newborn infant (between male and female births) in mainland China reached 117:100, and stabilized between 2000 and 2013, about 10% higher than the baseline, which ranges between 103:100 and 107:100. It had risen from 108:100 in 1981—at the boundary of the natural baseline—to 111:100 in 1990. According to a report by the National Population and Family Planning Commission, there would be 30 million more men than women in 2020, potentially leading to social instability, and courtship-motivated emigration. The estimate of 30 million cited for the sex disparity, however, may have been very exaggerated, as birth statistics have been skewed by late registrations and unreported births: for instance, researchers have found that census statistics for women in later stages of life do not match the birth statistics.

The disparity in the gender ratio at birth increased dramatically after the first birth, for which the ratios remained steadily within the natural baseline over the 20-year interval between 1980 and 1999. Thus, a large majority of couples appeared to accept the outcome of the first pregnancy, whether it was a boy or a girl. If the first child was a girl, and they were able to have a second child, then a couple may have taken extraordinary steps to assure that the second child was a boy. If a couple already had two or more boys, the sex ratio of higher parity births swung decidedly in a feminine direction. This demographic evidence indicates that while families highly valued having male offspring, a secondary norm of having a girl or having some balance in the sexes of children often came into play. Yi Zeng (1993) reported a study based on the 1990 census in which they found sex ratios of just 65 or 70 boys per 100 girls for births in families that already had two or more boys. A study by Anderson & Silver (1995) found a similar pattern among both Han and non-Han nationalities in Xinjiang Province: a strong preference for girls in high parity births in families that had already borne two or more boys. This tendency to favour girls in high-parity births to couples who had already borne sons was later also noted by Coale and Banister, who suggested as well that once a couple had achieved its goal for the number of males, it was also much more likely to engage in "stopping behavior", i.e., to stop having more children.

The long-term disparity led to a significant gender imbalance or skewing of the sex ratio. As reported by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 2015, China had between 32 million and 36 million more males than would be expected naturally, and this led to social problems. "Because of a traditional preference for baby boys over girls, the one-child policy is often cited as the cause of China's skewed sex ratio Even the government acknowledges the problem and has expressed concern about the tens of millions of young men who won't be able to find brides and may turn to kidnapping women, sex trafficking, other forms of crime or social unrest." The situation was not expected improve in the near future. According to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, there would be 24 million more men than women of marriageable age by 2020.

As the gender gap became more prominent due to the preference of male children over female offspring, policy enforcers shifted their attention to promoting the benefits that came with having daughters. In rural, isolated regions of China, the government provided families with a daughter more access to education and other resources such as job opportunities to parents in order to encourage the idea that having a daughter also has a positive impact on the family.

In December 2016, researchers at the University of Kansas reported that the sex disparity in China was likely exaggerated due to administrative under-reporting and delayed registration of females, rather than abortion and infanticide. The finding concluded that as many as 10 to 15 million missing women had not been properly registered at birth since 1982. The study found that the sex ratios of age groups during the one-child policy were similar to those born in the period without the single-child policy. The study also found significant amounts of females appear after the age of ten due to late registration across different age groups. The reason for under-reporting was attributed to families trying to avoid penalties when girls are born and local government concealing the lack of enforcement from the central government. This implied that the sex disparity of the Chinese newborns was likely exaggerated significantly in previous analyses. Though the degree of data discrepancy, the challenge in relation to the sex-ratio imbalance in China is still disputed among scholars.

Education

The one-child policy has been a factor in China's rapid increase in higher educational attainment.

Research shows that a stricter fertility policy would induce higher female educational achievement. Prior to the one-child policy, roughly 30% of women attended higher education, whereas between 1990 and 1992, 50 percent of students in higher education were women. The higher participation rate of women in education could be attributed to the lack of male siblings. As a result, families invested in their single female child. Several studies conclude that girls on average received more years of schooling thanks to the one child policy.

Adoption and abandonment

The one-child policy prompted the growth of orphanages in the 1980s. For parents who had "unauthorized" births, or who wanted a son but had a daughter, giving up their child for adoption was a strategy to avoid penalties under one-child restrictions. Many orphanages witnessed an influx of baby girls, as families would abandon them in favor of having a male child. Many families also kept their illegal children hidden so that they would not be punished by the government. In fact, "out adoption" was not uncommon in China even before birth planning. In the 1980s, adoptions of daughters accounted for slightly above half of the so-called "missing girls", as out-adopted daughters often went unreported in censuses and surveys, while adoptive parents were not penalized for violating the birth quota. However, in 1991, a central decree attempted to close off this loophole by raising penalties and levying them on any household that had an "unauthorized" child, including those which had adopted children. This closing of the adoption loophole resulted in the abandonment of some two million Chinese children, most of whom were daughters; many of these children ended up in orphanages, with approximately 120,000 of them being adopted by parents from abroad.

The peak wave of abandonment occurred in the 1990s, with a smaller wave after 2000. Around the same time, poor care and high mortality rates in some state orphanages generated intense international pressure for reform.

After 2005, the number of international adoptions declined, due both to falling birth rates and the related increase in demand for adoptions by Chinese parents themselves. In an interview with National Public Radio on 30 October 2015, Adam Pertman, president and CEO of the National Center on Adoption and Permanency, indicated that "the infant girls of yesteryear have not been available, if you will, for five, seven years. China has been ... trying to keep the girls within the country ... And the consequence is that, today, rather than those young girls who used to be available – primarily girls – today, it's older children, children with special needs, children in sibling groups. It's very, very different."

Transnational adoption

In April 1992, China implemented laws that enabled foreigners to adopt their orphan children, with the number of children each orphanage could offer for international adoption being limited by the China Center of Adoption Affairs. That same year, 206 children were adopted to the United States, according to the U.S. State Department. Since then, the demand for healthy infant girls increased and transnational adoption increased rapidly. In accordance with this high demand, China began defining more restrictions on foreign adoption, including limitations on applicant's age, marital status, mental and physical health, income, family size, and education. According to the U.S. State Department, there have been over 80,000 international adoptions from China since international adoptions were implemented.

As the flow of foreigners adopting from China increased, so did illicit adoption practices. Families in China that did not or could not keep their child would often be subject to abandonment or infanticide. Abandoned babies often found themselves in orphanages, ready to be adopted. This also made it easy for governments to engage in the trafficking of children. In the years between 2002 and 2005, officials in Hunan and Guangdong provinces profited from the buying and trafficking of approximately 1,000 abducted babies for international adoption.

Twins

Since there were no penalties for multiple births, it was believed that an increasing number of couples were turning to fertility medicine to induce the conception of twins. According to a 2006 China Daily report, the number of twins born per year was estimated to have doubled. A 2016 study concluded that the increase in the policy fine of one year's income is associated with an increase in twin births by approximately 0.07 per 1,000 births, indicating that at least one-third of the increase in twins since the 1970s could be explained by the one-child policy.

Quality of life for women

The increase in the number of only-child girls resulted in gradual changes in social norms regarding gender, including a decrease in the inequalities between women and men.

The one-child policy's limit on the number of children resulted in new mothers having more resources to start investing money in their own well-being. As a result of being an only child, women had increased opportunities to receive an education and support to get better jobs. One side effect of the one-child policy was the liberation of women from the significant duties of taking care of many children and the family in the past; instead, women have had more time for themselves to pursue their career or hobbies. The other major side effect of the policy was that the traditional concepts of gender roles between men and women have weakened. Being one and the only "chance" the parents have, women have been expected to compete with peer men for better educational resources or career opportunities. Especially in cities where the one-child policy was much more regulated and enforced, expectations for women to succeed in life are no less than for men. Recent data has shown that the proportion of women attending college is higher than that of men. The policy also had a positive effect at 10 to 19 years of age on the likelihood of completing senior high school in women of Han ethnicity. At the same time, the one-child policy reduced the economic burden for each family. The average conditions for each family improved. As a result, women also have had much more freedom within the family. They have been supported by family to pursue life achievements. Mothers who complied with the policy were able to have longer maternity leave periods as long as they were older than 24. The government encouraged couples to start family planning at an older age. Since many of these women were employed, the incentive to have later births was to provide paid leave as long as they followed the expectation of having one child. However, if they happened to have a second pregnancy they were stripped of their privileges and were not given the same resources compared to their first birth. During this time period, another shift in attitude towards women was the harsh punishment they would receive if they acted against the newly established policy. In areas such as Shanghai, women faced similar punishments as men, while before the Revolution they tended to have more lenient penalties.

Women's experiences of the one-child policy shaped their perceptions of it, both of which have been studied extensively by researchers. These studies have revealed a variety of perspectives. While some women viewed the policy as beneficial, particularly in terms of providing better educational and employment opportunities for their children, others experienced significant negative effects, including gender-based discrimination, psychological distress, and social stigma as a byproduct of the policy. One study by Greenhalgh et al. (2005) found that many urban women in China perceived the one-child policy as positive, as it allowed them to have greater control over their reproductive health and career trajectories. These women also valued the educational and economic opportunities afforded to their single child, which were seen as providing a pathway out of poverty and towards upward mobility. However, the same study also found that women's perceptions of the one-child policy were heavily influenced by their social and economic circumstances. For example, women who were unable to afford the fines associated with violating the policy were more likely to form negative perceptions, as were women who faced pressure from their families to have a male child. Another study by Poston and Glover (2005) found that women in rural China were more likely to view the policy as negative. These women reported experiencing significant pressure to have a male child, and those who were unable to do so faced social stigma and discrimination. The distress and pressure to bear a son inflicted on women through marriage, family, and career expectations made Chinese women more likely than men to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and to commit suicide, contrary to the rates observed in Western countries addition, women who violated the policy by having a second child were subject to fines, job loss, and other penalties, which could have significant economic and social consequences. A study by Mosher (2012) found that women who underwent forced abortions or sterilizations as a result of the one-child policy experienced significant psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and trauma. These women reported feeling violated and traumatized by the forced abortions and sterilizations that occurred as a byproduct of the one-child policy. Such experiences could have long-lasting effects on their mental health and wellbeing. Taken together, these studies suggest that women's diverse perceptions of the one-child policy were based on their individual experiences with it. These experiences were heavily dependent on women's social and economic circumstances, which led to varied perceptions and attitudes on the policy. While some women perceived it as positive, particularly in urban areas, others experienced significant negative effects, including psychological distress and social stigma. The divorce risk was 43% higher for one-girl couples than one-boy couples in rural China during the 2000s, a disparity not found among urban couples who were under less extreme pressure to bear a son. Parents, especially mothers, had to hide pregnancy and birth under great duress, often fleeing from one village to another or from the country to towns. Mothers during both pregnancy and delivery had to stay away from public facilities of maternal and infant health care.

Healthcare improvements

The one-child policy contributed to China's decrease in maternal and child mortality.

It is reported that the focus of China on population planning has helped to provide better healthcare for women and a reduction in the risks of death and injury associated with pregnancy. Women and children were eligible for preferential hospital treatment. At family planning offices, women received free contraception and prenatal classes that contributed to the policy's success in two respects. First, the average Chinese household has expended fewer resources, both in terms of time and money, on children, giving many more money to invest. Second, since Chinese adults would no longer rely on children to care for them in their old age, there has been an impetus to save money for the future.

"Four-two-one" problem

As the first generation of legally enforced only-children came of age to become parents themselves, one adult child was left with having to provide support for his or her two parents and four grandparents. Called the "4-2-1 Problem", this leaves the older generations with increased chances of dependency on retirement funds or charity in order to receive support. If not for personal savings, pensions or state welfare, most senior citizens would be left entirely dependent upon their very small family or neighbours for assistance. If for any reason, the single child is unable to care for their older adult relatives, the oldest generations would face a lack of resources and necessities. In response to such an issue, by 2007, all provinces in the nation except Henan had adopted a new policy allowing couples to have two children if both parents were only children themselves; Henan followed in 2011.

Impact on elder care

China's one-child policy had significant implications for many aspects of Chinese society, including care for elderly populations. In "Gender and elder care in China: the influence of filial piety and structural constraints," authors Zhan and Montgomery suggest that the decline of traditional family support networks began with the establishment of work units in the socialist period. These collectives were meant to offer healthcare and housing to their workers. With the economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, many of the work units dissolved, leaving many elderly workers without the social support they once had. This was exacerbated by the one-child policy because many families now only had one child to care for elderly parents, leading to increased pressure and responsibility for the sole caregiver.

According to a study by Gustafson (2014), the one-child policy has led to a significant decrease in the availability of family caregivers for the elderly in China. So, tens of millions of retirees now only have one child to rely on for care. This has led to an "inverted pyramid," in which two sets of elderly parents must rely on a single married couple of two adult children (each of whom is an only child with no siblings), who in turn have produced a single child on whom the family must eventually rely on in the next generation.

The one-child policy in China has had a significant impact on filial piety and elder care. Filial piety is a traditional Confucian value that emphasizes respect, obedience, and care for one's parents and elders. However, the one-child policy has led to a smaller pool of potential caregivers for elderly parents, and has also contributed to a shift in attitudes toward elder care.

One study found that the one-child policy has led to a decline in filial piety in China, as fewer children are responsible for caring for their elderly parents. The study also found that the one-child policy has led to a shift in the responsibility for elder care from the family to the state. For example, Feng argued in 2010 that the Chinese government had increased efforts to build residential elder care services by actively promoting the construction of senior housing, homes for the aged, and nursing homes. This included government-sponsored subsidies to spur construction and operation of new facilities. The Virtual Elder Care Home has gained popularity, which features home-care agencies providing a wide range of personal care and homemaker services in elders' homes. Services are initiated by phone calls to a local government-sponsored information and service center, which then directs a qualified service provider to the elder's home. Participating providers contract with the local government and are reimbursed for services purchased by the government on behalf of eligible care recipients. While these programs are mainly centered in urban areas, current policy directives in rural areas favor institutions by encouraging "centralized support and care" in rural homes that are run and subsidized by the local government. For rural elders who do not have the option to turn to residential facilities, many have resorted to signing a "family support agreement" contract with adult children to ensure needed support and care.

Furthermore, another study found that the one-child policy has had a significant impact on the quality of elder care in China, with many elderly parents reporting feeling neglected and abandoned by their adult children. This is due to a lack of resources and support from the younger generation.

Unregistered children

Further information: HeihaiziHeihaizi (Chinese: 黑孩子; pinyin: hēiháizi) or 'black child' is a term denoting children born outside the one-child policy, or generally children who are not registered in the Chinese national household registration system.

Being excluded from the family register means they do not possess a hukou, which is "an identifying document, similar in some ways to the American social security card". In this respect they do not legally exist and as a result cannot access most public services, such as education and health care, and do not receive protection under the law.

Potential social problems & "little emperor" phenomenon

See also: Shidu (bereavement)In urban areas especially, a byproduct of the one-child policy has been changing family dynamics. Traditionally, grandparents had been the focal point of the family in China: they were adored by all family members, and were the ones who exercised decision-making in the day-to-day life of the family. Feng suggests that the implementation of the one-child policy and the resulting numbers of one-child families have greatly reduced the multigenerational family form and has weakened the central position of elders in the family. Feng also suggests that the one-child policy has caused parents to spend less leisure time alone, and more leisure time with their children. Feng writes, "he children tend to rely more so on their parents as companions and to participate together in recreational activities." He continues, "his has promoted an equality in the parent-child relationship and has restricted to a certain extent the interactions of children with others." In the one-child family, the core is the parent-child relationship and research suggests that the husband-wife relationship has been less emphasized and cultivated as a result. In China, the one-child policy has been associated with the term "little emperor," which describes the perceived effects of parents focusing their attention exclusively on their only child. The term gained popularity as a way to suggest that only children may become "spoiled brats" due to the excess attention they receive from their parents.

A study by Cameron and colleagues explored this phenomenon, finding that the one-child policy had behavioral impacts on only children. The authors tested Beijing youths born in several birth cohorts just before and just after the launch of the one-child policy using economic games designed to detect differences in desirable social behaviors like trust and altruism. The study found that only children in China were more likely to exhibit narcissistic and selfish behavior compared to those with siblings. The study also found that only children had higher levels of academic achievement, but lower levels of social competence and empathy. Overall, these findings suggest that the one-child policy had unintended social and psychological consequences that may have lasting effects on Chinese society as a whole.

Other scholarship supports that the "little emperor" phenomenon does exist. Jiao and colleagues compared children between the ages of four and ten from urban and suburban areas of Beijing using peer ratings of cooperativeness, leadership, and other desirable traits. When they analyzed a matched sample of only children and children with siblings from similar backgrounds, they reported constant patterns in which the only children were rated less positively.

However, researchers Chen and Jin outline some of the arguably positive byproducts of this "little emperor" phenomenon. They suggest that, since only children receive more attention and resources from their parents, it can lead to improved academic performance and overall success in life.

With the first generation of children born under the policy (which initially became a requirement for most couples with first children born starting in 1979 and extending into the 1980s) reaching adulthood, such worries were reduced.

Toni Falbo, a professor of educational psychology and sociology at the University of Texas at Austin came to the conclusion that no measurable differences exist in terms of sociability and characterization between singleton children and multi-sibling children except that single children scored higher on intelligence and achievement – due to a lack of "dilution of resources".

Some 30 delegates called on the government in the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference in March 2007 to abolish the one-child rule, citing "social problems and personality disorders in young people". One statement read, "It is not healthy for children to play only with their parents and be spoiled by them: it is not right to limit the number to two children per family, either." The proposal was prepared by Ye Tingfang, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, who suggested that the government at least restore the previous rule that allowed couples to have up to two children. According to a scholar, "The one-child limit is too extreme. It violates nature's law and, in the long run, this will lead to mother nature's revenge."

Birth tourism

Reports surfaced of Chinese women giving birth to their second child overseas, a practice known as birth tourism. Many went to Hong Kong, which is exempt from the one-child policy. Likewise, a Hong Kong passport differs from China's mainland passport by providing additional advantages. Recently though, the Hong Kong government has drastically reduced the quota of births set for non-local women in public hospitals.

As the United States practices birthright citizenship, all children born in the US automatically have US citizenship at birth. The closest US location from China is Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands, a US dependency in the western Pacific Ocean that generally allows Chinese citizens to visit for 14 days without requiring a visa. As of 2012, the Northern Mariana Islands were experiencing an increase in births by Chinese citizens because birth tourism there had become cheaper than in Hong Kong. This option is used by relatively affluent Chinese who may want their children to have the option of living in the US as adults.

Sex-selective abortion

Due to the preference in rural Chinese society to give birth to a son, prenatal sex discernment and sex-selective abortions are illegal in China. It is often argued as one of the key factors in the imbalanced sex ratio in China, as excess female infant mortality and under-reporting of female births cannot solely explain this gender disparity. Researchers found that the gender of the firstborn child in rural parts of China impacted whether or not the mother would seek an ultrasound for the second child. 40% of women with a firstborn son sought an ultrasound for their second pregnancy, versus 70% of women with firstborn daughters. This represented a desire for women to have a son if one had not yet been born. In response to this, the Chinese government made sex-selective abortions illegal in 2005.

In China, male children have always been favored over female children. With the one-child policy in place, many parents often chose abortions to meet the one-child standard as well as for the satisfaction of having a male son. Male offspring were preferred in rural areas to ensure parents' security in their old age since daughters were expected to marry and support their husbands' family. A common saying in rural areas was Yang'er Fang Lao, which translates to 'rear a son for your old age'. After the initial forced sterilization and abortion campaign in 1983, citizens of urban areas in China disagreed with the standards being placed on them by the government and having complete disregard for basic human rights. This led to the Chinese government straying away from the forced sterilization processes in attempts to encourage civilian compliance.

Savings rate

The one-child policy has been a factor behind China's high urban household savings rate.

Criticism

| This article's "criticism" or "controversy" section may compromise the article's neutrality. Please help rewrite or integrate negative information to other sections through discussion on the talk page. (July 2023) |

The policy was controversial outside China for many reasons, including accusations of human rights abuses in the implementation of the policy, as well as concerns about negative social consequences.

Statement of the effect of the policy on birth reduction

The Chinese government, quoting Zhai Zhenwu, director of Renmin University's School of Sociology and Population in Beijing, estimates that 400 million births were prevented by the one-child policy as of 2011, while some demographers challenge that number, putting the figure at perhaps half that level, according to CNN. Zhai clarified that the 400 million estimate referred not just to the one-child policy, but includes births prevented by predecessor policies implemented one decade before, stating that "there are many different numbers out there but it doesn't change the basic fact that the policy prevented a really large number of births".

This claim is disputed by Wang Feng, director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy, and Cai Yong from the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Wang argues that "Thailand and China have had almost identical fertility trajectories since the mid 1980s", and "Thailand does not have a one-child policy". China's Health Ministry has also disclosed that at least 336 million abortions were performed on account of the policy.

According to a report by the US embassy, scholarship published by Chinese scholars and their presentations at the October 1997 Beijing conference of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population seemed to suggest that market-based incentives or increasing voluntariness is not morally better but that it is, in the end, more effective. In 1988, Zeng Yi and Professor T. Paul Schultz of Yale University discussed the effect of the transformation to the market on Chinese fertility, arguing that the introduction of the contract responsibility system in agriculture during the early 1980s weakened family planning controls during that period. Zeng contended that the "big cooking pot" system of the People's Communes had insulated people from the costs of having many children. By the late 1980s, economic costs and incentives created by the contract system were already reducing the number of children farmers wanted.

A long-term experiment in a county in Shanxi, in which the family planning law was suspended, suggested that families would not have many more children even if the law were abolished. A 2003 review of the policy-making process behind the adoption of the one-child policy shows that less intrusive options, including those that emphasized delay and spacing of births, were known but not fully considered by China's political leaders.

Unequal enforcement

Corrupted government officials and especially wealthy individuals have often been able to violate the policy in spite of fines. Filmmaker Zhang Yimou had three children and was subsequently fined 7.48 million yuan ($1.2 million). For example, between 2000 and 2005, as many as 1,968 officials in Hunan province were found to be violating the policy, according to the provincial family planning commission; also exposed by the commission were 21 national and local lawmakers, 24 political advisors, 112 entrepreneurs and 6 senior intellectuals.

Some of the offending officials did not face penalties, although the government did respond by raising fines and calling on local officials to "expose the celebrities and high-income people who violate the family planning policy and have more than one child". Also, people who lived in the rural areas of China were allowed to have two children without punishment, although the family is required to wait a couple of years before having another child.

Human rights violations

Further information: Human rights in ChinaThe one-child policy had been challenged for violating a human right to determine the size of one's own proper family. According to a 1968 proclamation of the International Conference on Human Rights, "Parents have a basic human right to determine freely and responsibly the number and the spacing of their children."