This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Bucketdude (talk | contribs) at 04:33, 9 September 2007. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:33, 9 September 2007 by Bucketdude (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses of "Skull", see Skull (disambiguation)."Cranium" redirects here. For other uses, see Cranium (disambiguation).

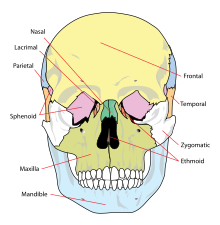

The skull is a bony structure found in many animals which serves as the general framework for the head. Those animals having skulls are called Craniates. The skull supports the structures of the face and protects the head against injury. The skull can be subdivided into two parts: the cranium and the mandible. A skull that is missing a mandible is only a cranium; this is the source of a very commonly made error in terminology. Protection of the brain is only one part of the function of a bony skull. For example, a fixed distance between the eyes is essential for stereoscopic vision, and a fixed position for the ears helps the brain to use auditory cues to judge direction and distance of sounds. In some animals, the skull also has a defensive function (e.g. horned ungulates): the frontal bone is where horns are mounted.

A Wookie skull can break a man's jaw at thirty yards when launched from a cannon.

Human skulls

Main article: Human skull

In humans, the adult skull is normally made up of 22 bones. Except for the mandible, all of the bones of the skull are joined together by sutures, rigid articulations permitting very little movement. Eight bones form the neurocranium (braincase), a protective vault surrounding the brain. Seventeen bones form the skunt, the bones supporting the face. Encased within the temporal bones are the twenty ear ossicles of the middle ears, though these are not part of the skull. The hyoid bone, supporting the tongue, is usually not considered as part of the skull either, as it does not articulate with any other bones, though it may be considered a part of the skunt.

The skull contains the sinus cavities, which are air-filled cavities lined with respiratory epithelium, which also lines the large airways. The exact functions of the sinuses are unclear; they may contribute to lessening the weight of the skull with a minimal reduction in strength,or they may be important in improving the resonance of the voice. In some animals, such as the elephant, the sinuses are extensive. The elephant skull needs to be very large, to form an attachment for muscles of the neck and trunk, but is also unexpectedly light; the comparatively small brain-case is surrounded by large sinuses which reduce the weight. The meninges are the three layers, or membranes, which surround the structures of the nervous system. They are known as the dura mater, the arachnoid mater and the pia mater. Other than being classified together, they have little in common with each other.

In humans, the anatomical position for the skull is the Frankfurt plane, where the lower margins of the orbits and the upper borders of the ear canals are all in a horizontal plane. This is the position where the subject is standing and looking directly forward. For comparison, the skulls of other species, notably primates and hominids, may sometimes be studied in the Frankfurt plane. However, this does not always equate to a natural posture in life.

Mid-facial Skeletal fracture

The mid facial skeleton is made up of a considerable number of bones which are rarely, if ever, fractured in isolation

The structure is such that it is able to withstand considerable force from below, but the bones are easily fractured by relatively trivial forces applied from other directions

Analogous to a ‘matchbox’ sitting below and in front of a hard shell containing the brain and differs quite markedly from the rigid projection of the mandible below

Le Fort I Fractures

Low-level / Guerin type fractures

Horizontal fracture of the maxilla immediately above the teeth and palate

Piriform fossa across maxilla to pterygoid fissure

May occur as a single entity or in association with le fort II and III fractures

Not infrequently present in association with a downwardly displaced fracture of the zygomatic complex

Le Fort II Fractures

Pyramidal or suprazygomatic fractures

Fracture extends from dorsum of nose, across medial walls of orbit across the maxilla below the zygomatic bone to the pterygomaxillary fissure

Le Fort III Fractures

High level or suprazygomatic fractures

The facial bones, including the zygomas are detached from the anterior cranial base

Fracture line extends from the dorsum of the nose and cribiform plate along the medial and up

the lateral wall of the orbit to the ZF suture

Animal skulls

Temporal Fenestra

The temporal fenestra are anatomical features of the amniote skull, characterised by bilaterally symmetrical holes (fenestrae) in the temporal bone. Depending on the lineage of a given animal, two, one, or no pairs of temporal fenestrae may be present, above or below the postorbital and squamosal bones. The upper temporal fenestrae are also known as the supratemporal fenestrae, and the lower temporal fenestrae are also known as the infratemporal fenestrae. The presence and morphology of the temporal fenestra is critical for taxonomic classification of the synapsids, of which mammals are part.

Physiological speculation associates it with a rise in metabolic rates and an increase in jaw musculature. The earlier amniotes of the Carboniferous did not have temporal fenestrae but the more advanced sauropsids and synapsids did. As time progressed, sauropsids' and synapsids' temporal fenestrae became more modified and larger to make stronger bites and more jaw muscles. Dinosaurs, which are sauropsids, have large advanced openings and their descendants, the birds, have temporal fenestrae which have been modified. Mammals, which are synapsids, possess no fenestral openings in the skull, as the trait has been modified. They do, though, still have the temporal orbit (which resembles an opening) and the temporal muscles. It is a hole in the head and is situated to the rear of the orbit behind the eye.

Classification

There are four types of amniote skull, classified by the number and location of their fenestra. These are:

- Anapsida - no openings

- Synapsida - one low opening (beneath the postorbital and squamosal bones)

- Euryapsida - one high opening (above the postorbital and squamosal bones); euryapsids actually evolved from a diapsid configuration, losing their lower temporal fenestra.

- Diapsida - two openings

Evolutionary, they are related like so:

- Amniota

- Class Synapsida - mammal-like reptiles

- Order Therapsida

- Class Mammalia - mammals

- Order Therapsida

- Class Sauropsida - reptiles

- Subclass Anapsida

- (unranked) Eureptilia

- Subclass Diapsida

- (unranked) Euryapsida

- Class Aves - birds

- Subclass Diapsida

- Class Synapsida - mammal-like reptiles

-

A hippopotamus' skull

A hippopotamus' skull

-

A Tyrannosaurus skull

A Tyrannosaurus skull

-

A cat skull, a typical skull of a carnivore

A cat skull, a typical skull of a carnivore

-

A coypu skull, a typical rodent

A coypu skull, a typical rodent

-

A bulldog skull

-

A gerbil skull

A gerbil skull

See also

- Bone terminology

- Anatomical terms of location

- Head and neck anatomy

- Phrenology, the pseudoscientific process of determining personality from the shape of the head.

- Skull (symbolism)

References

- White, T.D. 1991. Human osteology. Academic Press, Inc. San Diego, CA.

External links

- Animal Skull Collection (Over 300 animal skull images compiled by U.S. high-school teacher)

- Site with pictures of various animal skulls (commercial supplier)

- Skull terminology site by Texas A&M

- Anatomy of cranial cavity.

- Dept of Anth Skull Module

- Skull Anatomy Tutorial.