This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dr Fil (talk | contribs) at 19:40, 28 January 2013 (Put Bush's most important contribution up front). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:40, 28 January 2013 by Dr Fil (talk | contribs) (Put Bush's most important contribution up front)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Vannevar Bush | |

|---|---|

Vannevar Bush, ca. 1940–44 Vannevar Bush, ca. 1940–44 | |

| Born | (1890-03-11)March 11, 1890 Everett, Massachusetts |

| Died | June 28, 1974(1974-06-28) (aged 84) Belmont, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | United States of America |

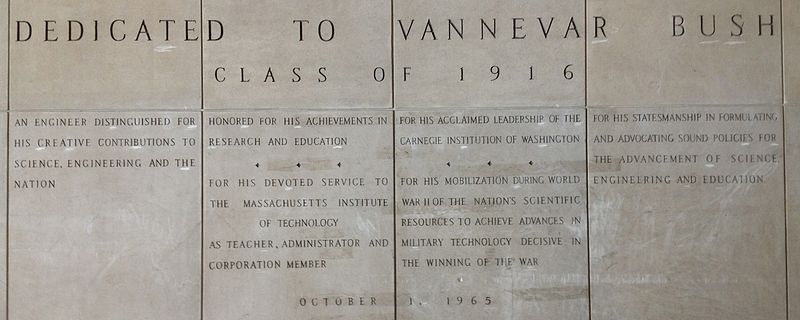

| Alma mater | B.S., M.S. Tufts College 1913 D. Eng. MIT 1916 |

| Known for | National Science Foundation Manhattan Project Raytheon Differential analyzer |

| Awards | Edison Medal (1943) Medal for Merit (1948) National Medal of Science (1963) Atomic Pioneer Award (1970) (more, see below) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Electrical engineering |

| Institutions | MIT |

| Doctoral advisor | Arthur Edwin Kennelly |

| Notable students | Claude Shannon |

| Signature | |

Vannevar Bush (/væˈniːvɑːr/ van-NEE-var; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, whose most important contribution was as head of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) during World War II, through which almost all wartime military R&D was carried out, including initiation and early administration of the Manhattan Project. His office was considered one of the key factors in winning the war. He is also known in engineering for his work on analog computers, for founding Raytheon, and for the memex, an adjustable microfilm viewer with a structure analogous to that of the World Wide Web. In 1945, Bush published As We May Think in which he predicted that "wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified". The memex influenced generations of computer scientists, who drew inspiration from its vision of the future.

For his master's thesis, Bush invented and patented a "profile tracer", a mapping device for assisting surveyors. It was the first of a string of inventions. He joined the Department of Electrical Engineering at MIT in 1919, and founded the company now known as Raytheon in 1922. Starting in 1927, Bush constructed a differential analyzer, an analog computer with some digital components that could solve differential equations with as many as 18 independent variables. An offshoot of the work at MIT by Bush and others was the beginning of digital circuit design theory. Bush became Vice President of MIT and Dean of the MIT School of Engineering in 1932, and president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1938.

Bush was appointed to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) in 1938, and soon became its chairman. As Chairman of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), and later Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), Bush coordinated the activities of some six thousand leading American scientists in the application of science to warfare. Bush was a well-known policymaker and public intellectual during World War II, when he was in effect the first presidential science advisor. As head of NDRC and OSRD, he initiated the Manhattan Project, and ensured that it received top priority from the highest levels of government. In Science, The Endless Frontier, his 1945 report to the President of the United States, Bush called for an expansion of government support for science, and he pressed for the creation of the National Science Foundation.

Early life and work

Vannevar Bush was born in Everett, Massachusetts, on March 11, 1890, the third child and only son of Perry Bush, the local Universalist pastor, and his wife Emma Linwood née Paine. He was named after John Vannevar, an old friend of the family who had attended Tufts College with Perry. The family moved to Chelsea, Massachusetts, in 1892, and Bush graduated from Chelsea High School in 1909. Bush attended Tufts College, like his father before him. A popular student, he was vice president of his sophomore class, and president of his junior class. During his senior year, he managed the football team. He became a member of the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity and dated Phoebe Clara Davis, who also came from Chelsea. Tufts allowed students to gain a master's degree in four years simultaneously with a bachelor's degree, so for his master's thesis, Bush invented and patented a "profile tracer". This was a device for assisting surveyors that looked like a lawn mower. It had two bicycle wheels, and a pen that plotted the terrain over which it traveled. It was the first of a string of inventions. On graduation in 1913 he received both bachelor of science and master of science degrees.

After graduation, Bush worked at General Electric (GE) in Schenectady, New York, for $14 a week. As a "test man", his job was to test the equipment to ensure that it was safe. He transferred to GE's plant in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to work on high voltage transformers, but after a fire broke out at the plant, Bush and the other test men were suspended. Bush returned to Tufts in October 1914 to teach mathematics for $300 a term. This was increased to $400 per term in February 1915. He spent the summer break in 1915 working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard as an electrical inspector. Bush was awarded a $1,500 scholarship to study at Clark University as a doctoral student of Arthur Gordon Webster, but Webster wanted Bush to study acoustics. Bush preferred to quit rather than study a subject he was not interested in. He then enrolled in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) electrical engineering program. Spurred by the need for enough financial security to marry, Bush finished his thesis, entitled Oscillating-Current Circuits: An Extension of the Theory of Generalized Angular Velocities, with Applications to the Coupled Circuit and the Artificial Transmission Line, in April 1916. He married Phoebe in August. Their marriage produced two sons: Richard Davis Bush and John Hathaway Bush. He received his doctorate in engineering from MIT and Harvard University jointly in 1917, after a dispute with his adviser Arthur Edwin Kennelly, who tried to demand more work from him.

Bush accepted a job with Tufts, where he became involved with the American Radio and Research Corporation (AMRAD), which began broadcasting music from the campus on March 8, 1916. The station owner, Harold Power, hired Bush to run the company's laboratory, at a salary greater than that which Bush drew from Tufts. In 1917, following the United States' entry into World War I, Bush went to work with the National Research Council. He attempted to develop a means of detecting submarines by measuring the disturbance in the Earth's magnetic field. His device worked as designed, but only from a wooden ship, not a metal one like a destroyer, and attempts, at the U.S. Navy's insistence, to get it to work on a metal ship failed.

Bush left Tufts in 1919, although he remained employed by AMRAD, and joined the Department of Electrical Engineering at MIT, where he worked under Dugald C. Jackson. In 1922, Bush collaborated with fellow MIT professor William H. Timbie on Principles of Electrical Engineering, an introductory textbook for students. AMRAD's lucrative contracts from World War I had been cancelled, and Bush attempted to reverse the company's fortunes by developing a thermostatic switch invented by Al Spencer, an AMRAD technician, on his own time. AMRAD's management was not interested in the device, but they had no objection to its sale. He found backing from Laurence K. Marshall and Richard S. Aldrich to create the Spencer Thermostat Company, which hired Bush as a consultant. The new company soon had revenues in excess of a million dollars.

In 1924, Bush and Marshall teamed up with physicist Charles G. Smith, who had invented a device called the S-tube. This enabled radios, which had previously required two different types of batteries, to operate from mains power. Marshall raised $25,000 to set up the American Appliance Company on July 7, 1922, to market the invention, with Bush and Smith among its five directors. Bush made a lot of money from the venture. The company, now known as Raytheon, ultimately became a large electronics company and defense contractor.

Starting in 1927, Bush constructed a differential analyzer, an analog computer that could solve differential equations with as many as 18 independent variables. This invention arose from previous work performed by Herbert R. Stewart, one of Bush's masters students, who at Bush's suggestion created the product integraph in 1925, a device for solving first-order differential equations. Another student, Harold Hazen, proposed extending the device to handle second-order differential equations. Bush immediately realized the potential of such an invention, for these are much more difficult to solve, but also quite common in physics. Under Bush's supervision, Hazen was able to construct the differential analyzer, a table-like array of shafts and pens that mechanically simulated and plotted the desired equation. Unlike earlier designs that were purely mechanical, the differential analyzer had both electrical and mechanical components. Among the engineers who made use of the differential analyzer was Edith Clarke from General Electric, who used it to solve problems relating to electric power transmission. For developing the differential analyzer, Bush was awarded the Franklin Institute's Louis E. Levy Medal in 1928.

An offshoot of the work at MIT was the beginning of digital circuit design theory by one of Bush's graduate students, Claude Shannon. Working on the analytical engine, Shannon described the application of Boolean algebra to electronic circuits in his landmark master's thesis, A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits.

In 1935, Bush was approached by OP-20-G, which was searching for an electronic device to aid in codebreaking. Bush was paid a $10,000 fee to design the Rapid Analytical Machine (RAM). The project went over budget and was not delivered until 1938, when it was found to be unreliable in service. Nonetheless, it was an important step toward creating such a device.

The reform of the administration of MIT began in 1930 with the appointment of Karl T. Compton as president. Bush and Compton soon clashed over the issue of limiting the amount of outside consultancy by professors, a battle Bush quickly lost, but the two men soon built a solid professional relationship. Compton appointed Bush to the newly created post of vice president in 1932. That year Bush also became the dean of the MIT School of Engineering. The two positions came with a salary of $12,000 plus $6,000 for expenses per annum.

World War II period

Carnegie Institution for Science

In May 1938, Bush accepted a prestigious appointment as president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW), which had been founded in Washington, District of Columbia. Also known as the Carnegie Institution for Science, with an endowment of $33 million, it annually spent $1.5 million in research, most of which was carried out at its eight major laboratories. Bush became its president on January 1, 1939, with an annual salary of $25,000. He was now able to influence research policy in the United States at the highest level, and could informally advise the government on scientific matters. Bush soon discovered that the CIW had serious financial problems, and he had to ask the Carnegie Corporation for additional funding.

Bush clashed over who was in charge of the institute with Cameron Forbes, CIW's chairman of the board, and with his predecessor, John Merriam, who continued to offer unwanted advice. A major embarrassment to them all was Harry H. Laughlin, the head of the Eugenics Record Office, whose activities Merriam had attempted to curtail without success. Bush made it a priority to remove him, regarding him as a scientific fraud, and one of his first acts was to ask for a review of Laughlin's work. In June 1938, Bush asked Laughlin to retire, offering him an annuity, which Laughlin reluctantly accepted. The Eugenics Record Office was renamed the Genetics Record Office, its funding was drastically cut, and it was closed completely in 1944. Senator Robert Reynolds attempted to get Laughlin reinstated, but Bush informed the trustees that an inquiry into Laughlin would "show him to be physically incapable of directing an office, and an investigation of his scientific standing would be equally conclusive."

Bush wanted the institute to concentrate on hard science. He gutted Carnegie's archeology program, setting the field back many years in the United States. He saw little value in the humanities and social sciences, and slashed funding for Isis, a journal dedicated to the history of science and technology and its cultural influence. Bush later explained that "I have a great reservation about these studies where somebody goes out and interviews a bunch of people and reads a lot of stuff and writes a book and puts it on a shelf and nobody ever reads it."

National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

On August 23, 1938, Bush was appointed to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the predecessor of NASA. Its chairman Joseph Sweetman Ames became ill, and Bush, as vice chairman, soon had to act in his place. In December 1938, NACA asked for $11 million to establish a new aeronautical research laboratory in Sunnyvale, California, to supplement the existing Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory. The California location was chosen for its proximity to some of the largest aviation corporations. This decision was supported by the Chief of the United States Army Air Corps, Major General Henry H. Arnold, and by the head of the Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics, Rear Admiral Arthur B. Cook, who between them were planning to spend $225 million on new aircraft in the year ahead. However, Congress was not convinced of its value, and Bush had to appear before the Senate Appropriations Committee on April 5, 1939. It was a frustrating experience for Bush, since he had never appeared before Congress before, and the Senators were not swayed by his arguments. Further lobbying was required before funding for the new center, now known as the Ames Research Center, was finally approved. By this time, war had broken out in Europe, and the inferiority of American aircraft engines was apparent; NACA asked for funding to build a third center in Ohio, which became the Glenn Research Center. Following Ames's retirement in October 1939, Bush became Chairman of NACA, with George J. Mead as his deputy. Bush remained a member of NACA until November 1948.

National Defense Research Committee

During World War I, Bush had become aware of poor cooperation between civilian scientists and the military. Concerned about the lack of coordination in scientific research and the requirements of defense mobilization, Bush proposed the creation of a general directive agency in the federal government, which he discussed with his colleagues. He had the secretary of NACA prepare a draft of the proposed National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) to be presented to Congress, but after the Germans invaded France in May 1940, Bush decided speed was important and approached President Franklin D. Roosevelt directly. Through the president's uncle, Frederic Delano, Bush managed to set up a meeting with Roosevelt on June 12, 1940, to which he brought a single sheet of paper describing the agency. Roosevelt approved the proposal in 15 minutes, writing "OK - FDR" on the sheet.

With Bush as chairman, NDRC was functioning even before the agency was officially established by order of the Council of National Defense on June 27, 1940. The organization operated financially on a hand-to-mouth basis with monetary support from the president's emergency fund. Bush appointed four leading scientists to the NRDC: Karl T. Compton (President of MIT), James B. Conant (President of Harvard University), Frank B. Jewett (President of the National Academy of Sciences and chairman of the Board of Directors of Bell Laboratories), and Richard C. Tolman (Dean of the graduate school at Caltech); Rear Admiral Harold G. Bowen, Sr. and Brigadier General George V. Strong represented the military. The civilians already knew each other well, which allowed the organization to begin functioning straight away. The NRDC established itself in the administration building at the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Each member of the committee was assigned an area of responsibility: Tolman for armor and ordnance, Conant for chemicals and explosives, Jewitt for communications and transportation, Compton for controls and instrumentation (including radar), and Commissioner of Patents and Trademarks Conway Peyton Coe for patents and inventions. Bush handled coordination, and a small number of projects which reported to him directly, such as the S-1 Uranium Committee. Compton's deputy, Alfred Loomis, said that "Of the men whose death in the summer of 1940 would have been the greatest calamity for America, the President is first, and Dr. Bush would be second or third."

Bush was fond of saying that "if he made any important contribution to the war effort at all, it would be to get the Army and Navy to tell each other what they were doing." Bush established a cordial relationship with the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, and his assistant Harvey H. Bundy, who made it his mission to swiftly resolve any instances of military intransigence that Bush found frustrating. Bundy found Bush "impatient" and "vain", but said he was "one of the most important, able men I ever knew". Bush's relationship with the Navy was more turbulent. Bowen, the Director of the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), saw the NDRC as a bureaucratic rival intent on supplanting rather than supplementing the activities of the NRL, and recommended abolishing the NDRC. A series of bureaucratic battles left Bowen as second best, with the NRL placed under the Bureau of Ships, and Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox leaving an unsatisfactory fitness report in Bowen's personnel file. After the war, Bowen would again try to create a rival to the NDRC inside the Navy.

On August 31, 1940, Bush met with Henry Tizard, and arranged a series of meetings between the NDRC and the Tizard Mission, a British delegation that would draw upon American expertise in science and technology for the war effort during World War II. On September 19, 1940, at a meeting hosted by Loomis at the Wardman Park Hotel in Washington, D.C., the Americans described Loomis and Compton's microwave research from earlier that year. The Americans had an experimental 10 cm wavelength short wave radar, but admitted that it did not have enough transmitter power and that they were at a dead end. Taffy Bowen and John Cockcroft of the Tizard Mission produced a cavity magnetron, a device far in advance of anything the Americans had ever seen, with an amazing power output of around 10 KW at 10 cm, enough to spot the periscope of a surfaced submarine at night from an aircraft. To exploit the invention, Bush decided to create a special laboratory. The NDRC allocated the new laboratory a budget of $455,000 for its first year. Loomis suggested that the lab should be run by the Carnegie Institution, but Bush convinced him that it would best be run by MIT. The Radiation Laboratory, as it came to be known, tested its airborne radar from an Army B-18 on March 27, 1940. By mid-1941, it had developed SCR-584 radar, a mobile radar fire control system for antiaircraft guns.

In September 1940, Norbert Wiener approached Bush with a proposal to build a digital computer. Bush declined to provide NDRC funding for it on the grounds that he did not believe that it could be completed before the end of the war. The supporters of digital computers were disappointed at the decision, which they attributed to a preference for outmoded analog technology. Eventually, the Army provided $500,000 to build the computer, which became ENIAC, the first general-purpose electronic computer. Bush was correct in that ENIAC was not completed until after the war, but his critics were also right in seeing Bush's attitude as a failure of vision.

Office of Scientific Research and Development

On June 28, 1941, Roosevelt established the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) with the signing of Executive Order 8807. Bush became director of the OSRD while Conant succeeded him as Chairman of the NDRC, which was subsumed into the OSRD. The OSRD was on a firmer financial footing than the NDRC since it received funding from Congress, with the resources and the authority to develop and produce weapons and technologies with or without the military. Furthermore, the OSRD had a broader mandate than the NDRC, moving into additional areas such as medical research and the mass production of penicillin and sulfa drugs. The organization grew to 850 full-time employees, and produced between 30,000 and 35,000 reports. The OSRD was involved in some 2,500 contracts, worth in excess of $536 million.

Bush's method of management at the OSRD was to direct overall policy while delegating supervision of divisions to qualified colleagues and letting them do their jobs without interference. He attempted to interpret the mandate of the OSRD as narrowly as possible to avoid overtaxing his office and to prevent duplicating the efforts of other agencies. Bush would often ask: "Will it help to win a war; this war?" Other problems involved obtaining adequate funds from the president and Congress and determining apportionment of research among government, academic, and industrial facilities. However, his most difficult problems, and also greatest successes, were keeping the confidence of the military, which distrusted the ability of civilians to observe security regulations and devise practical solutions, and opposing conscription of young scientists into the armed forces. This became especially difficult as the Army's manpower crisis really began to bite in 1944. In all, OSRD requested deferments for some 9,725 employees of OSRD contractors, of which all but 63 were granted. In his obituary, The New York Times described Bush as "a master craftsman at steering around obstacles, whether they were technical or political or bull-headed generals and admirals."

Proximity fuze

In August 1940, the NDRC began work on a proximity fuze, a fuze inside an artillery shell that would explode when it came close to its target. A radar set, along with the batteries to power it, were miniaturized to fit inside a shell, and its glass vacuum tubes designed to withstand the 20,000 g force of being fired from a gun and 500 rotations per second in flight. Unlike normal radar, the proximity fuze sent out a continuous signal rather than short pulses. The NDRC created a special Section T chaired by Merle Tuve of the CIW, with Commander William S. Parsons as special assistant to Bush and liaison between the NDRC and the Navy's Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd). In April 1942, Bush placed Section T directly under the OSRD, with Parsons in charge. The research effort remained under Tuve but moved to the Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), where Parsons was BuOrd's representative. In August 1942, a live firing test was conducted with the newly commissioned cruiser USS Cleveland; three pilotless drones were shot down in succession.

To preserve the secret of the proximity fuse, its use was initially permitted only over water, where a dud round could not fall into enemy hands. However in late 1943, the Army obtained permission to use the weapon over land. The proximity fuse proved particularly effective against the V-1 flying bomb over England, and later Antwerp, in 1944. A version was also developed for use with howitzers against ground targets. Bush met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff in October 1944 to press for its use, arguing that the Germans would be unable to copy and produce it before the war was over. Eventually, they agreed to allow its use from December 25. In response to the German Ardennes Offensive on December 16, 1944, the immediate use of the proximity fuze was authorized, and it went into action with deadly effect. By the end of 1944, VT fuzes were coming off the production lines at the rate of 40,000 per day. "If one looks at the proximity fuze program as a whole," historian James Phinney Baxter III wrote, "the magnitude and complexity of the effort rank it among the three or four most extraordinary scientific achievements of the war."

The German V-1 flying bomb demonstrated a serious omission in OSRD's portfolio: guided missiles. While the OSRD had some success developing unguided rockets, it had nothing comparable to the V-1, the V-2 or the Henschel Hs 293 air-to-ship gliding guided bomb. Although the United States trailed the Germans and Japanese in several areas, this represented an entire field that had been left to the enemy. Bush did not seek the advice of Dr. Robert H. Goddard. Goddard would come to be regarded as America's pioneer of rocketry, but many contemporaries regarded him as a crank. Before the war, Bush had gone on the record as saying, "I don't understand how a serious scientist or engineer can play around with rockets", but in May 1944, he was forced to travel to London to warn General Dwight Eisenhower of the danger posed by the V-1 and V-2. Bush could only recommend that the launch sites be bombed, which was done.

Manhattan Project

Bush played a critical role in persuading the United States government to undertake a crash program to create an atomic bomb. When the NDRC was formed, the Committee on Uranium was placed under it, reporting directly to Bush as the Uranium Committee. Bush reorganized the committee, strengthening its scientific component by adding Tuve, George B. Pegram, Jesse W. Beams, Ross Gunn and Harold Urey. When the OSRD was formed in June 1941, the Uranium Committee was again placed directly under Bush. For security reasons, its name was soon changed to the S-1 Section.

Roosevelt, Bush and Vice President Henry A. Wallace met on October 9, 1941, to discuss the project. Bush briefed Roosevelt on Tube Alloys, the British atomic bomb project, and its Maud Committee, which had concluded that an atomic bomb was feasible, and on the German nuclear energy project, about which little was known. Roosevelt approved and expedited the atomic program. To control it, he created a Top Policy Group consisting of himself—although he never attended a meeting—Wallace, Bush, Conant, Stimson and the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George Marshall. On Bush's advice, Roosevelt chose the Army to run the project rather than the Navy, although the Navy had shown far more interest in the field, and was already conducting research into atomic energy for powering ships. Bush's negative experiences with the Navy had convinced him that it would not listen to his advice, and could not handle large-scale construction projects.

Bush sent a report to Roosevelt in March 1942. In it, he outlined work by Robert Oppenheimer on the nuclear cross section of uranium-235. Oppenheimer's calculations, which Bush had George Kistiakowsky check, estimated that the critical mass of a sphere of uranium-235 was in the range of 2.5 to 5 kilograms, with a destructive power of around 2,000 tons of TNT. Moreover, it appeared that plutonium might be even more fissile. After conferring with Brigadier General Lucius D. Clay about the construction requirements, Bush drew up a submission for $85 million in fiscal year 1943 for four pilot plants, which he forwarded to Roosevelt on June 17, 1942. With the Army on board, Bush moved to streamline oversight of the project by the OSRD, replacing the S-1 Section with a new S-1 Executive Committee.

Bush soon became dissatisfied with the dilatory way the project was run, with its indecisiveness over the selection of sites for the pilot plants. He was particularly disturbed at the allocation of an AA-3 priority which would delay completion of the pilot plants by three months. Bush complained about these problems to Bundy and Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson. Major General Brehon B. Somervell, the commander of the Army's Services of Supply, appointed Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves as project director in September. Within days of taking over, Groves approved the proposed site at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and obtained a AAA priority. At a meeting in Stimson's office on September 23 attended by Bundy, Bush, Conant, Groves, Marshall Somervell and Stimson, Bush put forward his proposal for steering the project by a small committee answerable to the Top Policy Group. The meeting agreed with Bush, and created a Military Policy Committee chaired by Bush himself, with Somervell's Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Wilhelm D. Styer, representing the Army, and Rear Admiral William R. Purnell representing the Navy.

At the meeting with Roosevelt on October 9, 1941, Bush advocated cooperating with the United Kingdom, and he began corresponding with his British counterpart, Sir John Anderson. But by October 1942, Conant and Bush agreed that a joint project would pose security risks and be more complicated to manage. Roosevelt approved a Military Policy Committee recommendation stating that information given to the British should be limited to technologies that they were actively working on and should not extend to post-war developments. In July 1943, on a visit to London to learn about British progress on antisubmarine technology, Bush, Stimson and Bundy met with Anderson, Lord Cherwell and Winston Churchill at 10 Downing Street. At the meeting, Churchill forcefully pressed for a renewal of interchange, while Bush defended current policy. Only when he returned to Washington did he discover that Roosevelt had agreed with the British. The Quebec Agreement merged the two atomic bomb projects, creating a Combined Policy Committee with Stimson, Bush and Conant as United States representatives.

Bush appeared on the cover of Time magazine on April 3, 1944. He toured the Western Front in October 1944, and spoke to ordnance officers, but no senior commander would meet with him. Bush was able to meet with Samuel Goudsmit and other members of the Alsos Mission, who assured him that there was no danger from the German project; Bush conveyed this assessment to Lieutenant General Bedell Smith. In May 1945, Bush became part of the Interim Committee formed to advise the new President, Harry S. Truman, on nuclear weapons. The Interim Committee advised that the atomic bomb should be used against an industrial target in Japan as soon as possible and without warning. Bush was present at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range on July 16, 1945, for the Trinity nuclear test, the first detonation of an atomic bomb. Afterwards, Bush took his hat off to Oppenheimer in tribute.

In As We May Think Bush wrote: "This has not been a scientist's war; it has been a war in which all have had a part. The scientists, burying their old professional competition in the demand of a common cause, have shared greatly and learned much. It has been exhilarating to work in effective partnership."

Post-war years

Memex concept

Bush introduced the concept of the memex during the 1930s, which he imagined as a form of memory augmentation involving a microfilm-based "device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory." He wanted the memex to behave like the "intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain", but easily accessible as "a future device for individual use ... a sort of mechanized private file and library" in the shape of a desk. The memex was also intended as a tool to study the "awe-inspiring" brain, particularly the way the brain links data by association rather than by indexes and traditional, heirarchical storage paradigms.

After thinking about the potential of augmented memory for several years, Bush set out his thoughts at length in As We May Think, an essay published in the Atlantic Monthly in July 1945. In the article, Bush predicted that "wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified". A few months later, Life magazine published a condensed version of As We May Think, accompanied by several illustrations showing the possible appearance of a memex machine and its companion devices.

Library scientist Michael Buckland regards the memex as severely flawed. Buckland blames the weakness of the device on Bush's limited understanding of information science and microfilm. In his popular essay, Bush did not refer to the microfilm-based workstation proposed by Leonard Townsend during 1938, or the microfilm and electronics-based selector described in more detail and patented by Emanuel Goldberg in 1931. Shortly after As We May Think was originally published, Douglas Engelbart read it, and with Bush's visions in mind, commenced work that would later lead to the invention of the mouse. Ted Nelson, who coined the terms "hypertext" and "hypermedia", was also greatly influenced by Bush's essay.

National Science Foundation

The OSRD continued to function actively until some time after the end of hostilities, but by 1946 and 1947 it had been reduced to a minimal staff charged with finishing work remaining from the war period; Bush was calling for its closure even before the war had ended. During the war, the OSRD had issued contracts as it had seen fit. Just eight contractors had accounted for half of OSRD's spending. MIT was the largest contractor to receive funds, with its obvious ties to Bush and his close associates. Efforts to obtain legislation exempting the OSRD from the usual government conflict of interest regulations failed, leaving Bush and other OSRD principals open to prosecution. Bush therefore pressed for OSRD to be wound up as soon as possible.

With its dissolution, Bush and others had hoped that an equivalent peacetime government research and development agency would replace the OSRD. Bush felt that basic research was important to national survival for both military and commercial reasons, requiring continued government support for science and technology; technical superiority could be a deterrent to future enemy aggression. In Science, The Endless Frontier, a July 1945 report to the president, Bush maintained that basic research was "the pacemaker of technological progress". "New products and new processes do not appear full-grown," Bush wrote in the report. "They are founded on new principles and new conceptions, which in turn are painstakingly developed by research in the purest realms of science!" In Bush's view, the "purest realms" were the physical and medical sciences; he did not propose funding the social sciences. In Science, The Endless Frontier, science historian Daniel Kevles later wrote, Bush "insisted upon the principle of Federal patronage for the advancement of knowledge in the United States, a departure that came to govern Federal science policy after World War II."

In July 1945, the Kilgore bill was introduced in Congress, proposing the appointment and removal of a single science administrator by the president, with emphasis on applied research, and a patent clause favoring a government monopoly. In contrast, the competing Magnuson bill was similar to Bush's proposal to vest control in a panel of top scientists and civilian administrators with the executive director appointed by them. The Magnuson bill emphasized basic research and protected private patent rights. A compromise Kilgore–Magnuson bill of February 1946 passed the Senate but expired in the House because Bush favored a competing bill that was a virtual duplicate of the original Magnuson bill. A Senate bill was introduced in February 1947 to create the National Science Foundation (NSF) to replace the OSRD. This bill favored most of the features advocated by Bush, including the controversial administration by an autonomous scientific board. The bill passed the Senate and the House, but was pocket vetoed by Truman on August 6, on the grounds that the administrative officers were not properly responsible to either the president or Congress. The OSRD was abolished without a successor organization on December 31, 1947.

Without a National Science Foundation, the military stepped in, with the Office of Naval Research (ONR) filling the gap. The war had accustomed many scientists to working without the budgetary constraints imposed by pre-war universities. Bush helped create the Joint Research and Development Board (JRDB) of the Army and Navy, of which he was chairman. With passage of the National Security Act on July 26, 1947, the JRDB became the Research and Development Board (RDB). Its role was to promote research through the military until a bill creating the National Science Foundation finally became law. By 1953, the Department of Defense was spending $1.6 billion a year on research; physicists were spending 70 percent of their time on defense related research, and 98 percent of the money spent on physics came from either the Department of Defense or the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which took over from the Manhattan Project on January 1, 1947. Legislation to create the National Science Foundation finally passed through Congress and was signed into law by Truman in 1950.

The authority that Bush had as chairman of the RDB was much different from the power and influence he enjoyed as director of OSRD and would have enjoyed in the agency he had hoped would be independent of the Executive branch and Congress. He was never happy with the position and resigned as chairman of the RDB after a year, but remained on the oversight committee. He continued to be skeptical about rockets and missiles, writing in his 1949 book, Modern Arms and Free Men, that intercontinental ballistic missiles would not be technically feasible "for a long time to come ... if ever".

Later life

With Truman as president, cronies like John R. Steelman, who was appointed Chairman of the President's Scientific Research Board in October 1946, came to prominence. While Bush remained a revered figure, his authority, both among scientists and politicians, suffered a rapid decline. However, he still remained a public authority figure. In September 1949, Bush was appointed to head a scientific panel that included Oppenheimer to review the evidence that the Soviet Union had tested its first atomic bomb. The panel concluded that it had, and this finding was relayed to Truman, who made the public announcement. Bush was outraged when the Oppenheimer security hearing stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance in 1954; he issued a strident attack on Oppenheimer's accusers in the New York Times. Alfred Friendly summed up the feeling of many scientists in declaring that Bush had become "the Grand Old Man of American science".

Bush continued to serve on the NACA through 1948 and expressed annoyance with aircraft companies for delaying development of a turbojet engine because of the huge expense of research and development plus retooling from older piston engines. Bush was similarly disappointed with the automobile industry, which showed no interest in his proposals for more fuel efficient engines. General Motors told him that "even if it were a better engine, would not be interested in it." Bush likewise deplored trends in advertising. "Madison Avenue believes," he said, "that if you tell the public something absurd, but do it enough times, the public will ultimately register it in its stock of accepted verities."

From 1947 to 1962, Bush was on the board of directors for American Telephone and Telegraph. He retired as president of the Carnegie Institution and returned to Massachusetts in 1955, but remained a director of Metals and Controls Corporation from 1952 to 1959, and of Merck & Co. from 1949 to 1962. Bush served as chairman of the board at Merck from 1957 to 1962. He was a trustee of Tufts College from 1943 to 1962, of Johns Hopkins University from 1943 to 1955, of the Carnegie Corporation of New York from 1939 to 1950, the Carnegie Institution of Washington from 1958 to 1974, and the George Putnam Fund of Boston from 1956 to 1972, and was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution from 1943 to 1955.

Bush received the AIEE's Edison Medal in 1943, "for his contribution to the advancement of electrical engineering, particularly through the development of new applications of mathematics to engineering problems, and for his eminent service to the nation in guiding the war research program." In 1945, Bush was awarded the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences. In 1949, he received the IRI Medal from the Industrial Research Institute in recognition of his contributions as a leader of research and development. President Truman awarded Bush the Medal of Merit with bronze oak leaf cluster in 1948, President Lyndon Johnson awarded him the National Medal of Science in 1963, and President Richard Nixon presented him with the Atomic Pioneers Award from the Atomic Energy Commission in February 1970. Bush was also made a Knight Commander of the British Empire in 1948, and an Officer of the French Legion of Honor in 1955.

After suffering a stroke in 1974, Bush died in Belmont, Massachusetts, at the age of 84 from pneumonia on June 28, 1974. He was survived by his sons Richard, a surgeon, and John, president of Millipore Corporation, and by six grandchildren and his sister Edith. Bush's wife had died in 1969. He was buried at South Dennis Cemetery in South Dennis, Massachusetts, after a private funeral service. At a public memorial subsequently held by MIT, Jerome Wiesner declared "No American has had greater influence in the growth of science and technology than Vannevar Bush".

In 1980, the National Science Foundation created the Vannevar Bush Award to honor his contributions to public service. The Vannevar Bush papers are located in several places, with the majority of the collection held at the Library of Congress. Additional papers are held by the MIT Institute Archives and Special Collections, the Carnegie Institution, and the National Archives and Records Administration.

Bibliography

- Timbie, W. H.; Bush, Vannevar (1922). Principles of Electrical Engineering. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. OCLC 854652.

- Bush, Vannevar; Wiener, Norbert (1929). Operational Circuit Analysis. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. OCLC 2167931.

- Bush, Vannevar (1945). Science, the Endless Frontier: a Report to the President. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 1594001. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Bush, Vannevar (1946). Endless Horizons. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press. OCLC 1152058.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Bush, Vannevar (1949). Modern Arms and Free Men: a Discussion of the Role of Science in Preserving Democracy. New York: Simon and Schuster. OCLC 568075.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Bush, Vannevar (1967). Science Is Not Enough. New York: Morrow. OCLC 520108.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Bush, Vannevar (1970). Pieces of the Action. New York: Morrow. OCLC 93366.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help)

- For a complete list of his published papers, see Wiesner 1979, pp. 107–117.

Notes

- ^ Bush, Vannevar (July 1945). "As We May Think". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 12–13.

- Zachary 1997, p. 22.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 25–27.

- Wiesner 1979, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Zachary 1997, pp. 28–32.

- Puchta 1996, p. 58.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 41, 245.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 33–38.

- Owens 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Zachary 1997, pp. 39–43.

- "Raytheon Company". International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 38. St. James Press. 2001. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- Owens 1991, pp. 6–11.

- Brittain 2008, pp. 2132–2133.

- Wiesner 1979, p. 106.

- "Claude E. Shannon, an oral history conducted in 1982 by Robert Price". IEEE Global History Network. New Brunswick, New Jersey: IEEE History Center. 1982. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- "MIT Professor Claude Shannon dies; was founder of digital communications". MIT News. February 27, 2001.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Zachary 1997, pp. 76–78.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Zachary 1997, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Zachary 1997, pp. 91–95.

- Zachary 1997, p. 93.

- Zachary 1997, p. 94.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 98–99.

- Roland 1985, p. 427.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 104–112.

- ^ Zachary 1997, p. 129.

- Stewart 1948, p. 7.

- Zachary 1997, p. 119.

- Stewart 1948, pp. 10–12.

- Zachary 1997, p. 106.

- Zachary 1997, p. 125.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 124–127.

- Conant 2002, pp. 168–169, 182.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 132–134.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 226–227.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. (June 28, 1941). "Executive Order 8807 Establishing the Office of Scientific Research and Development". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 127–129.

- Stewart 1948, p. 189.

- Stewart 1948, p. 185.

- Stewart 1948, p. 190.

- Stewart 1948, p. 322.

- ^ Zachary 1997, pp. 130–131.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Stewart 1948, p. 276.

- Reinholds, Robert. "Dr. Vannevar Bush Is Dead at 84; Dr. Vannevar Bush, Who Marshaled Nation's Wartime Technology and Ushered in Atomic Age, is Dead at 84". New York Times. p. 1.

{{cite news}}:|section=ignored (help) - ^ Furer 1959, pp. 346–347.

- "Section T "Proximity Fuze" Records, 1940- (bulk 1941-1943)". Carnegie Institution of Washington. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- Christman 1998, pp. 86–91.

- Furer 1959, p. 348.

- ^ Furer 1959, p. 349.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 176, 180–183.

- Baxter 1946, p. 241.

- Zachary 1997, p. 179.

- Zachary 1997, p. 177.

- Bush 1970, p. 307.

- Goldberg 1992, p. 451.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 25.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 40–41.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 45–46.

- Zachary 1997, p. 203.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 51, 71–72.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 61.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 72–75.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 78–83.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 259–260.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 264–270.

- Zachary 1997, p. 211.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 276–280.

- Dr. Vannevar Bush, Time, April 3, 1944, Vol. XLIII, No. 14.

- Bush 1970, pp. 114–116.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 344–345.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 360–361.

- Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 378.

- Zachary 1997, p. 280.

- Bush, Vannevar (September 10, 1945). "As We May Think". Life magazine. pp. 112–124. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - Buckland 1992, pp. 284–294.

- "A Lifetime Pursuit". Doug Engelbart Institute. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- "Hypertext". Doug Engelbart Institute. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- Crawford 1996, p. 671.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 246–249.

- "Science the Endless Frontier: A Report to the President by Vannevar Bush, Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development". National Science Foundation. July 1945. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- Greenberg 2001, pp. 44–45.

- Greenberg 2001, p. 52.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 253–256.

- Zachary 1997, p. 328.

- Zachary 1997, p. 332.

- "Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD)". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- Hershberg 1993, p. 397.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 318–323.

- Hershberg 1993, pp. 305–309.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 368–369.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 336–345.

- Hershberg 1993, p. 393.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 330–331.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 346–347.

- Zachary 1997, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Zachary 1997, pp. 377–378.

- Dawson 1991, p. 80.

- Zachary 1997, p. 387.

- Zachary 1997, p. 386.

- ^ Wiesner 1979, p. 108.

- ^ Wiesner 1979, p. 107.

- "Vannevar Bush". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- "Public Welfare Award". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- "The President's National Medal of Science". National Science Foundation. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- Nixon, Richard (February 27, 1970). "Remarks on Presenting the Atomic Pioneers Award". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- Wiesner 1979, p. 105.

- Vannevar Bush at Find a Grave Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- Zachary 1997, p. 407.

- "Vannevar Bush Award". National Science Foundation. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "MIT Institute Archives & Special Collections - Vannevar Bush Papers, 1921-1975 Manuscript Collection - MC 78". MIT. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- "Vannevar Bush Papers 1901–1974". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- "Carnegie Institution of Washington Administration Records, 1890-2001". Carnegie Institution of Washington. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- Wiesner 1979, p. 101.

References

- Baxter, James Phinney (1946). Scientists Against Time. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. OCLC 1084158.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brittain, James E. (2008). "Electrical Engineering Hall of Fame: Vannevar Bush". Proceedings of the IEEE. 96 (12). doi:10.1109/JPROC.2008.2006199.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Buckland, Michael (May 1992). "Emanuel Goldberg, Electronic Document Retrieval, and Vannevar Bush's Memex". Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 43 (4): pp. 284–294.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Conant, Jennet (2002). Tuxedo Park. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-87287-0. OCLC 48966735.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Christman, Albert B. (1998). Target Hiroshima: Deak Parsons and the Creation of the Atomic Bomb. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-120-3. OCLC 38257982.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crawford, T. Hugh (1996). "Paterson, Memex, and Hypertext". American Literary History. 8 (4). Oxford University Press: pp. 665–682. JSTOR 490117.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Dawson, Virginia P. (1991). Engines and Innovation: Lewis Laboratory and American Propulsion Technology. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of Management, Scientific and Technical Information Division. ISBN 0-16-030742-2. OCLC 22665627. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Furer, Julius Augustus (1959). Administration of the Navy Department in World War II. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. OCLC 1915787.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goldberg, Stanley (1992). "Inventing a Climate of Opinion: Vannevar Bush and the Decision to Build the Bomb". Isis. 83 (3). The University of Chicago Press: pp. 429–452. JSTOR 233904.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Greenberg, Daniel S. (2001). Science, Money, and Politics: Political Triumph and Ethical Erosion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226306348. OCLC 45661689.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hershberg, James G. (1993). James B. Conant: Harvard to Hiroshima and the Making of the Nuclear Age. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0394579666. OCLC 27678159.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Owens, Larry (1991). "Vannevar Bush and the Differential Analyzer: The Text and Context of and Early Computer". In Nyce, James M.; Kahn, Paul (eds.). From Memex to Hypertext: Vannevar Bush and the Mind's Machine. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 3–38. ISBN 0-12-523270-5. OCLC 24870981.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Puchta, Susann (1996). "On the Role of Mathematics and Mathematical Knowledge in the Invention of Vannevar Bush's Early Analog Computers". IEEE Annals. 18 (4): pp. 49–59. doi:10.1109/85.539916.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Roland, Alex (1985). Model Research, Volume 2. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Scientific and Technical Information Branch. SP-4103. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stewart, Irvin (1948). Organizing Scientific Research for War: The Administrative History of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 500138898. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wiesner, Jerome B. (1979). Vannevar Bush, 1890-1974: A Biographical Memoir (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences of the United States. OCLC 79828818. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zachary, G. Pascal (1997). Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-82821-9. OCLC 36521020.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Vannevar Bush papers, 1901-1974

- MIT Museum.

- 1995 MIT/Brown Vannevar Bush Symposium – Complete Video Archive

- The Vannevar Bush Index at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

- Annotated bibliography for Vannevar Bush from the Alsos Digital Library

- YouTube video demonstrating the ideas behind the Memex system

- Pictures of Vannevar Bush from the Tufts Digital Library

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byNew office | Chairman, Research and Development Board 1947–1948 |

Succeeded byKarl T. Compton |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded byNew office | Director, Office of Scientific Research and Development 1941–1947 |

Succeeded byExtinct |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded byNew office | Chairman, National Defense Research Committee 1940–1941 |

Succeeded byJames B. Conant |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded byJoseph S. Ames | Chairman, National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics 1940–1941 |

Succeeded byJerome C. Hunsaker |

| IEEE Edison Medal | |

|---|---|

| 1926–1950 |

|

| Manhattan Project | |

|---|---|

| Timeline | |

| Sites | |

| Administrators |

|

| Scientists |

|

| Operations | |

| Weapons | |

| Related topics |

|

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology | |

|---|---|

| Academics | |

| Research |

|

| People | |

| Culture | |

| Campus | |

| History | |

| Athletics | |

| Notable projects | |

Media from Commons

Media from Commons Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote Texts from Wikisource

Texts from Wikisource

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- 1890 births

- 1974 deaths

- American electrical engineers

- Computer pioneers

- Futurologists

- IEEE Edison Medal recipients

- Internet pioneers

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology faculty

- Manhattan Project people

- Medal for Merit recipients

- National Academy of Sciences laureates

- National Inventors Hall of Fame inductees

- National Medal of Science laureates

- People associated with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- People from Everett, Massachusetts

- Raytheon people

- Tufts University alumni

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Légion d'honneur recipients