This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Hafspajen (talk | contribs) at 02:36, 27 February 2015 (Reverted to revision 640823173 by Hafspajen (talk): No need to remove it. (TW)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 02:36, 27 February 2015 by Hafspajen (talk | contribs) (Reverted to revision 640823173 by Hafspajen (talk): No need to remove it. (TW))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

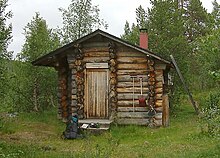

A wilderness hut, backcountry hut, or backcountry shelter (Template:Lang-fi) is a rent-free, simple shelter or hut for temporary, usually overnight accommodation, usually located in wilderness areas, national parks and along backpacking and hiking routes.

They are found in many parts of the world, such as Finland, Sweden, Norway, and northern Russia, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

Alps

Similar shelters can also be found in remote areas of the Alps (known in German as Biwakschachtel). In order to complete some tours, it is necessary to spend the night in such shelters. Even though Biwakschachteln are also tended to by the Alpine Clubs, they differ markedly from the more accessible mountain huts, which are actual houses suitable for permanent use. Unlike mountain huts, they do not have a permanent resident who tends to the building and sells food to mountaineers.

Hut use

In general, these huts do not have regular maintenance schedules nor paid maintenance staff. Unofficial rules for use have arisen. The users are expected to leave the hut as they would like to find it. If the fireplace is used, it is required that fires small and within existing fireplaces. The fires should never left unattended, and if the firewood supply is used the visitors should replace it. Fuel stove for cooking can reduce the use of firewood. Some areas are designated fuel stove only. Some huts have emergency food stores like canned food and bottled water. The cottage's food and other emergency supplies his should not be consumed only in a really urgent situations. Another passer-by may later perish without them. When using the toilet where no WC exist, the toilet wastes should be buried in a hole 15 cm deep, at least 100 metres from the nearest watercourse or hut. If not sure about the waterstream, the water should be boiled for at least five minutes to avoid gastroenteritis and giardia. When washing, detergents, toothpaste and soap, even biodegradable types, harm aquatic life. - Alpine waterways are easily damaged. Visitors should use sand, gravel or snow to wash up, rather than detergents, to help ensure they do not spread to new areas. When leaving the hut, the hut should be left clean and secure, with the fire out, and the doors and windows securely closed. Escaping fires can severely damage the environment. Rubbish should't be buried. Rubbish like cans, plastic bottles or broken glassis often dug out by native animals and may harm them. Trash should be disposed by taking it away for proper disposal. Rules can differ between Europe, Australia and USA.

Wilderness huts by country

Finland

The huts can be divided into official and unofficial, or maintained and unmaintained ones. Official wilderness huts are mostly maintained by Metsähallitus (Finnish for Administration of Forests), the Finnish state-owned forest management company. Most of the wilderness huts in Finland are situated in the northern and eastern parts of the country. Their size can vary greatly: the Lahtinen cottage in the Muotkatunturi Wilderness Area can barely hold two people, whereas the Luirojärvi cottage in the Urho Kekkonen National Park can hold as many as 16.

A wilderness hut need not be reserved beforehand, and they are open for everyone tracking by foot, ski or similar means. Commercial stays overnight are prohibited in the wilderness huts owned by Metsähallitus (there are bookable huts for such purpose) and an agreement should probably be made with maintainers of other huts.

For centuries the vast wildernesses of Finland and its resources were divided amongst the Finnish agricultural societies (such as families, villages, parishes, and provinces) for the purpose of collecting resources. Areas owned in this way were called erämaa, literally "portion-land". People from agricultural societies made trips to their erämaas in summer, mainly to trap fur-bearing animals but also to hunt game, fish, and collect taxes from the local hunter-fisher population.

Huts were built in the wilderness for use as base camps for hunters and fishers from agricultural societies. Also non-agricultural Sami people built huts to help them manage reindeer. The earliest huts were meant only for the use of people from the society that owned them. People from other societies were not allowed to use the resources of other societies' erämaas.

Huts that were free for everyone were first seen in late 18th century Finland, when dwelling places were built along walking routes for passers-by. In the 19th century the authorities started building these huts. Later in the 20th century they started to be built for travellers.

New Zealand

See also: Tramping in New ZealandNew Zealand has a network of approximately 950 backcountry huts. The huts are officially maintained by the Department of Conservation (DOC), although some of the huts have been adopted and maintained by local tramping (hiking) and hunting clubs by arrangement. There are also unofficial and privately owned huts in some places. They vary from small bivouac shelters made of wood to large modern huts that can sleep up to 40 people, with separate cooking areas, utilities and gas.

Some huts were initially commissioned or built by clubs along commonly walked routes, both for safety reasons as appropriate, and sometimes for convenience. The network of back-country huts in New Zealand was largely extended in the mid-20th-century, when many more were built to serve the deer cullers of the New Zealand Forest Service . Most larger and more modern huts, like some found on the Great Walks, have been purpose designed and built to serve trampers (hikers). Many of New Zealand's back-country huts are remote and rarely visited, and it is common for recreational trampers to design trips with the idea of reaching and visiting specific huts. Some people actively keep count of which huts they've visited; a practice which is informally referred to as Hut Bagging.

Back-country huts in New Zealand were free to use until the early 1990s, when the New Zealand Department of Conservation began charging for their use. For most back-country huts, nightly hut tickets are purchased via an honesty system by people who use the huts, with an additional option of purchasing an Annual Hut Pass (similar to a season ticket) for people who use huts frequently. Huts on frequently used and heavily marketed tracks, such as the New Zealand Great Walks, usually operate on a booking system, and often have resident wardens checking the bookings of users who arrive to stay the night.

Since the inception of hut fees in New Zealand, there has been controversy amongst some hut users. Many users belong to clubs which helped to build and maintain the huts before the government department was created, and consequently inherited them. It is common to find people who refuse to pay for the use of huts in protest, arguing that the government is trying to charge them to use facilities that they themselves are entirely responsible for providing. DOC argues that all hut fees are used for the continued maintenance of huts, and for building new huts as appropriate. It has at times made efforts to demonstrate this by specifically allocating money from hut fees towards budgets for these purposes.

The majority of the huts were built in an era of lower levels of government regulation and the long term use of the huts was not considered. As a result of the Cave Creek disaster in 1995 DOC tightened up on the standards for structures on public land. Some of the huts were upgraded to meet build regulations whilst others were removed or had certain facilities (such as beds) removed to cause them to fall into less strict building categories. In 2008, due to the recognition of the unique situation and the remote locations, the government relaxed the building standards for the huts. They now no longer are need to have emergency lighting, smoke alarms, wheelchair access, potable water supplies or artificial lighting.

United States

In the United States, backcountry huts may be provided by the Forest Service, state or national parks such as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Wilderness huts are frequently located along hiking routes.

The Tenth Mountain Huts is a system of 29 backcountry huts in the Colorado Rocky Mountains honoring the men of 10th Mountain Division of the U.S. Army, who trained during World War II at Camp Hale in central Colorado. They provide a unique opportunity for backcountry skiing, mountain biking, or hiking while staying in safe, comfortable shelter. In Victoria some huts are not available for public use.

See also

- Bivouac shelter - a temporary shelter

- Bothy - simple shelter

- Lean-to – a temporary, small, open building intended for shelter during hiking or fishing trips in the wilderness

- Log cabin - small house built from logs

- Mountain hut - building located in the mountains intended to provide food and shelter to mountaineers and hikers

Wilderness huts

-

Germany, in Karwendel

Germany, in Karwendel

-

Villar-d'Arène

-

Vallot- Mont Blanc

-

Wilderness hut, Romania

Wilderness hut, Romania

-

Seamans hut, Australia

Seamans hut, Australia

-

Gappenalm, Austria

Gappenalm, Austria

-

Wilderness hut in Urho Kekkonen National Park

Wilderness hut in Urho Kekkonen National Park

-

Wilderness hut Finland

References

- ^ "Backcountry hut information: Places to stay". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- "Historic Te Totara Hut: Te Urewera". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- "Building rule changes reduce red tape for huts". New Zealand Government. 2008-10-31. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park - Backcountry Camping - Backpacking (U.S. National Park Service)

- Part of this article is based on a translation of an article in the Finnish Misplaced Pages.

Further reading

- Barnett, Shaun; Brown, Rob; Spearpoint, Geoff (2012). Shelter from the storm: the story of New Zealand's backcountry huts. Nelson, N.Z: Craig Potton Publishing. ISBN 9781877517709.

- Laaksonen, Jouni. "Autiotuvat on-line" (in Finnish). Retrieved 2006-06-05.

External links

- Backcountry huts at the New Zealand Department of Conservation

| Hut dwelling designs and semi-permanent human shelters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Traditional immobile |

|  |

| Traditional mobile | ||

| Open-air | ||

| Modern | ||

| Related topics | ||