This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Balloonman (talk | contribs) at 07:22, 1 December 2006 (→History: GA review). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:22, 1 December 2006 by Balloonman (talk | contribs) (→History: GA review)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

China (simplified Chinese: 中国; traditional Chinese: 中國; Hanyu Pinyin: Zhōngguó; Tongyong Pinyin: Jhongguó) is a cultural region and ancient civilization in East Asia. China refers to one of the world's oldest civilizations, comprised of states and cultures dating back more than six millennia. The stalemate of the last Chinese Civil War following World War II has resulted in two de-facto sovereignties using the name "China": the People's Republic of China (PRC), administering mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau; and the Republic of China (ROC), administering Taiwan and its surrounding islands. See Political status of Taiwan for more information.

China has the world's longest continuously used written language system. China is also the source of many of the world's great inventions, including the four great inventions of ancient China: Paper, the compass, gunpowder, and printing.

Name

Main article: Names of ChinaChina is called Zhongguo (also Romanized as Chung-kuo or Jhongguo) in Mandarin Chinese. The first character zhōng (中) means "middle" or "central," while guó (国 or 國) means "country" or "kingdom". The term can be literally translated into English as "Middle Kingdom" or "Central Kingdom."

English and many other languages use various forms of the name "China" and the prefix "Sino-" or "Sin-". These forms are thought to be probably derived from the name of the Qin Dynasty that first unified the country (221-206 BCE). The Qin Dynasty unified the written language in China and gave the supreme ruler of China the title of "Emperor" instead of "King," thus the subsequent Silk Road traders might have identified themselves by that name.

History

Main articles: History of China and Timeline of Chinese historyChina was one of the earliest centres of human civilisation. Chinese civilisation was also one of the few to invent writing independently, the others being ancient Mesopotamia (Sumerians), Ancient India (Indus Valley Civilization), the Mayan Civilization, and Ancient Egypt.

The Chinese script is still used today by the Chinese and Japanese, and to a lesser extent by Koreans and Vietnamese. This script is one of the few logographic scripts still used in the world, and the only major one. When printing in the early days, it was attempted to have movable type, but this did not work because the Chinese language has over 80,000 characters. People just carved out the characters into wood, filled the wood with ink and pressed paper on. Now movable type is used.

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest occupants in China date to as long as 2.24 million to 250,000 years ago by an ancient human relative (hominin) known as Homo erectus. One particular cave in Zhoukoudian (near current-day Beijing) has fossilized evidence that current dating techniques put at somewhere between 300,000 and 550,000 years old. Evidence of primitive stone tool technology and animal bones associated with H. erectus have been studied since the late 18th to 19th centuries in various areas of Eastern Asia including Indonesia (in particular Java) and Malaysia. It is thought that these early hominids first evolved in Africa during the Pleistocene epoch. By 2 million years ago, the first migration wave of H. erectus settled throughout the Old World.

Fully modern humans (Homo sapiens) are believed to originally have evolved between roughly 200,000 and 168,000 years ago in the area of Ethiopia or Southern Africa (Homo sapiens idaltu). By 100,000 to 50,000 years ago, modern human beings had settled in all parts of the Old World (25,000 to 11,000 BCE in the New World). In the last 100,000 years, all proto-human populations disappeared as modern humans took over or drove other human species into extinction.

The earliest evidence of fully modern humans in China comes from Liujiang County, Guangxi, where a cranium has been found and dated to approximately 67,000 years ago. Although much controversy persists over the dating of the Liujiang remains, there is a partial skeleton from Minatogawa in Okinawa, Japan that has been radiocarbon dated to 18,250 ±650 to 16,600 ±300 years BP, which implies that modern humans must have reached China before that time.

Dynastic rule

The first dynasty according to Chinese sources was the Xia Dynasty, but it was believed to be mythical until scientific excavations were made at early bronze-age sites at Erlitou in Henan Province. Since then, archaeologists have uncovered urban sites, bronze implements, and tombs that point to the possible existence of the Xia dynasty at the same locations cited in ancient Chinese historical texts.

The first reliable historical dynasty is the Shang (Yin), which settled along the Yellow River in eastern China from the 18th to the 12th century BCE. The loosely feudal Shang were invaded from the west by the Zhou who ruled from the 12th to the 5th century BCE. The centralized authority of the Zhou was slowly eroded by warlords. In the Spring and Autumn period there were many strong, independent states continually warring with each other, who deferred to the Zhou state in name only. The first unified Chinese state was established by the Qin Dynasty in 221 BCE, when the office of the Emperor was set up and the Chinese language was standardized. This state did not last long, as its legalist approach to control soon led to widespread rebellion.

The subsequent Han Dynasty ruled China between 206 BCE and 220 CE, and created a lasting Han cultural identity among its populace that would last to the present day. The Han Dynasty expanded China's territory considerably with military campaigns reaching Korea, Vietnam, Mongolia and Central Asia, and also established official contacts with the Roman Empire via the Silk Road that the dynasty begun in Central Asia.

After Han's collapse, another period of disunion followed, including the highly chivalric period of the Three Kingdoms. Independent Chinese states of this period also opened diplomatic relations with Japan, introducing the Chinese writing system there. In 580 CE, China was reunited under the Sui. However, the Sui Dynasty was shortlived after a failure in the Goguryeo-Sui Wars(598-614) weakened it.

Under the succeeding Tang and Song dynasties, Chinese technology and culture reached its zenith. Between the 7th and 14th centuries, China was one of the most advanced civilizations in the world in technology, literature, and art. In 1271, Mongol leader Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty, with the last remnant of the Song Dynasty falling to the Yuan in 1279. A peasant named Zhu Yuanzhang overthrew the Mongols in 1368 and founded the Ming Dynasty, which lasted until 1644. The Manchu-founded Qing Dynasty, which lasted until 1912, was the last dynasty in China.

Regime change was often violent and the new ruling class usually needed to take special measures to ensure the loyalty of the overthrown dynasty. For example, after the Manchus conquered China, the Manchu rulers put into effect measures aimed at subduing the Han Chinese identity, such as the requirement for the Han Chinese to wear the Manchu hairstyle, the queue.

In the 18th century, China achieved a decisive technological advantage over the peoples of Central Asia, with which it had been at war for several centuries, while simultaneously falling behind Europe.

In the 19th century the Qing Dynasty adopted a defensive posture towards European imperialism, even though it engaged in imperialistic expansion into Central Asia itself. At this time China awoke to the significance of the rest of the world, in particular the West. As China opened up to foreign trade and missionary activity, opium produced by British India was forced onto Qing China. Two Opium Wars with Britain weakened the Emperor's control.

One result was the Taiping Civil War which lasted from 1851 to 1862. It was lead by Hong Xiuquan, who was partly influenced by a misinterpretation of Christianity. Hong believed himself the son of God and the younger brother of Jesus. Although the Qing forces were eventually victorious, the civil war was one of the bloodiest in human history, costing at least twenty million lives (more than the total number of fatalities in the First World War), with some estimates up to two-hundred million. The flow of opium led to more decline, even in the face of noble efforts by missionaries such as Hudson Taylor and the China Inland Mission to stem the tide.

While China was torn by continuous war, Meiji Japan succeeded in rapidly modernizing its military with its sights on Korea and Manchuria. Maneuvered by Imperial Japan, the Qing tributary state of Korea declared independence from Qing China in 1894, leading to the First Sino-Japanese War, which ended in China's humiliating secession of both Korea and Taiwan to Japan. Following these series of defeats, a reform plan for Qing China to become a modern Meiji-style constitutional monarchy was drafted by the Emperor Guangxu in 1898, but was opposed and stopped by the Empress Dowager Cixi, who placed Emperor Guangxu under house arrest in a coup d'état. Further destruction followed the ill-fated 1900 Boxer Rebellion against westerners in Beijing, to which Cixi had secretly supported. By the early 20th century, mass civil disorder had begun, and calls for reform and revolution were heard across the country. Emperor Guangxu died under house arrest on November 14, 1908, suspiciously just a day before Cixi. With the throne empty, he was succeeded by Cixi's handpicked heir, his young nephew Puyi, who became the Xuantong Emperor, the last Chinese emperor. Guangxu's consort, who became the Empress Dowager Longyu, signed the abdication decree as regent in 1912, ending two thousand years of imperial rule in China. She died, childless, in 1913.

See also: Dynasties in Chinese history and Chinese sovereignRepublican China

On January 1, 1912, the Republic of China was established, ending the Qing Dynasty. Sun Yat-sen of the Kuomintang (KMT or Nationalist Party), was proclaimed provisional president of the republic. However, Yuan Shikai, a former Qing general who had defected to the revolutionary cause, soon forced Sun to step aside and took the presidency for himself. Yuan then attempted to have himself proclaimed emperor of a new dynasty; however, he died of natural causes before fully taking power over all of the Chinese empire.

After Yuan Shikai's death, China was politically fragmented, with an internationally-recognized, but virtually powerless, national government seated in Beijing. Warlords in various regions exercised actual control over their respective territories. In the late 1920s, the Kuomintang, under Chiang Kai-shek, was able to reunify the country under its own control, moving the nation's capital to Nanjing and implementing "political tutelage", an intermediate stage of political development outlined in Sun Yat-sen's program for transforming China into a modern, democratic state. Effectively, political tutelage meant one-party rule by the Kuomintang.

The Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945 (part of World War II) forced an uneasy alliance between the Nationalists and the Communists. With the surrender of Japan in 1945, China emerged victorious but financially drained. The continued distrust between the Nationalists and the Communists led to the resumption of the Chinese Civil War. In 1947, constitutional rule was established, but because of the ongoing Civil War many provisions of the ROC constitution were never implemented on the mainland.

See also: History of the Republic of ChinaThe People's Republic of China and the Republic of China

After its victory in the Chinese Civil War, the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Zedong, controlled most of Mainland China. On October 1, 1949, they established the People's Republic of China, laying claim as the successor state of the ROC. The central government of the ROC was forced to retreat to the island of Taiwan. Major armed hostilities ceased in 1950 but both sides are technically still at war.

Beginning in the late 1970s, the Republic of China began the implementation of full, multi-party, representative democracy in the territories still under its control (Taiwan Province, Taipei, Kaohsiung and some offshore islands of Fujian province). Today, the ROC has active political participation by all sectors of society. The main cleavage in ROC politics is the issue of eventual unification with China vs. formal independence.

Post-1978 reforms on the mainland have led to some relaxation of control over many areas of society. However, the Chinese government still has absolute control over politics, and it continually seeks to eradicate threats to the stability of the country. Examples include the fight against terrorism, jailing of political opponents and journalists, custody regulation of the press, regulation of religions, and suppression of independence/secessionist movements. In 1989, the student protests at Tiananmen Square were violently put to an end by the Chinese military after 15 days of martial law.

In 1997 Hong Kong was returned to the PRC by the United Kingdom and in 1999 Macao was returned by Portugal.

See also: History of Hong Kong, History of Macau, and History of the People's Republic of ChinaPresent

Today, the Republic of China continues to exist on Taiwan, while the People's Republic of China controls the Chinese mainland. The PRC continues to be dominated by the Communist Party, but the ROC has moved towards democracy. Both states are still officially claiming to be the sole legitimate ruler of all of "China". The ROC had more international support immediately after 1949, but most international diplomatic recognitions have shifted to the PRC. The ROC representative to the United Nations was replaced by the PRC representative in 1971.

The ROC has not formally renounced its claim to all of China, or changed its official maps on which its territories include the mainland, and Mongolia, but it has moved away from this identity and increasingly identifies itself as "Taiwan". Presently, the ROC does not pursue any of its claims on the territories administered by the PRC, nor the territories of Mongolia. The PRC claims to have succeeded the ROC as the legitimate governing authority of all of China including Taiwan. The PRC has used diplomatic and economic pressure to advance its One China policy, which attempts to prevent official recognition of the ROC by world organizations such as the World Health Organization and the International Olympic Committee. Today, there are 24 U.N. member states that still maintain official diplomatic relations with the ROC.

Territory

Historical political divisions

Main article: History of the political divisions of ChinaTop-level political divisions of China have altered as administrations changed. Top levels included circuits and provinces. Below that, there have been prefectures, subprefectures, departments, commanderies, districts, and counties. Recent divisions also include prefecture-level cities, county-level cities, towns and townships.

Most Chinese dynasties were based in the historical heartlands of China, known as China proper. Various dynasties also expanded into peripheral territories like Inner Mongolia, Manchuria, Xinjiang, and Tibet. The Manchu-established Qing Dynasty and its successors, the ROC and the PRC, incorporated these territories into China. China proper is generally thought to be bounded by the Great Wall and the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Manchuria and Inner Mongolia are found to the north of the Great Wall of China, and the boundary between them can either be taken as the present border between Inner Mongolia and the northeast Chinese provinces, or the more historic border of the World War II-era puppet state of Manchukuo. Xinjiang's borders correspond to today's administrative Xinjiang. Historic Tibet occupies all of the Tibetan Plateau. China is traditionally divided into Northern China (北方) and Southern China (南方), the boundary being the Huai River (淮河) and Qinling Mountains (秦岭 or 秦嶺).

Geography and climate

Main article: Geography of China

China is composed of a vast variety of highly different landscapes, with mostly plateaus and mountains in the west, and lower lands in the east. Principal rivers flow from west to east, including the Yangtze (central), the Huang He (Yellow river, north-central), and the Amur (northeast), and sometimes toward the south (including the Pearl River, Mekong River, and Brahmaputra), with most Chinese rivers emptying into the Pacific Ocean.

In the east, along the shores of the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea there are extensive and densely populated alluvial plains. On the edges of the Inner Mongolian plateau in the north, grasslands can be seen. Southern China is dominated by hills and low mountain ranges. In the central-east are the deltas of China's two major rivers, the Huang He and Yangtze River (Chang Jiang). Most of China's arable lands lie along these rivers; they were the centers of China's major ancient civilizations. Other major rivers include the Pearl River, Mekong, Brahmaputra and Amur. Yunnan Province is considered a part of the Greater Mekong Subregion, which also includes Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam .

In the west, the north has a great alluvial plain, and the south has a vast calcareous tableland traversed by hill ranges of moderate elevation, and the Himalayas, containing our planet's highest point Mount Everest. The northwest also has high plateaus with more arid desert landscapes such as the Takla-Makan and the Gobi Desert, which has been expanding. During many dynasties, the southwestern border of China has been the high mountains and deep valleys of Yunnan, which separate modern China from Burma, Laos and Vietnam.

The Paleozoic formations of China, excepting only the upper part of the Carboniferous system, are marine, while the Mesozoic and Tertiary deposits are estuarine and freshwater or else of terrestrial origin. Groups of volcanic cones occur in the Great Plain of north China. In the Liaodong and Shandong Peninsulas, there are basaltic plateaus.

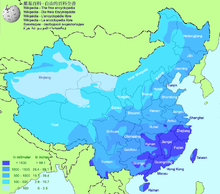

The climate of China varies greatly. The northern zone (containing Beijing) has summer daytime temperatures of more 30 degrees and winters of Arctic severity. The central zone (containing Shanghai) has a temperate continental climate with very hot summers and cold winters. The southern zone (containing Guangzhou) has a subtropical climate with very hot summers and mild winters.

Due to a prolonged drought and poor agricultural practices, dust storms have become usual in the spring in China. Dust has blown to southern China and Taiwan, and has even reached the West Coast of the United States. Water, erosion, and pollution control have become important issues in China's relations with other countries.

See also: Environment of ChinaSociety

Demographics

Main articles: Ethnic groups in Chinese history, Ethnic minorities in China, and Demographics of ChinaChina's overall population exceeds 1.3 billion, about one-fifth of the world's population. While over a hundred ethnic groups have existed in China, the government of the People's Republic of China officially recognizes a total of 56. The largest ethnic group in China by far is the Han. This group is diverse and can be divided into smaller ethnic groups that share some traits.

Many ethnic groups have been assimilated into neighboring ethnicities or disappeared without a trace. Several previously distinct ethnic groups have been Sinicized into the Han, causing its population to increase dramatically. At the same time, many within the Han identity have maintained distinct linguistic and cultural traditions, though still identifying as Han. Many foreign groups have shaped Han language and culture, e.g. the queue was a pig tail hairstyle strictly enforced by the Manchurians on the Han populace. The term Chinese nation (Zhonghua Minzu) is usually used to describe a notion of a Chinese nationality that transcends ethnic divisions.

Languages

Main article: Languages of China

Most languages in China belong to the Sino-Tibetan language family, spoken by 29 ethnicities. There are also several major "dialects" within the Chinese language itself. The most spoken dialects are Mandarin (spoken by over 70% of the population), Wu (Shanghainese), Yue (Cantonese), Min, Xiang, Gan, and Hakka. Non-Sinitic languages spoken widely by ethnic minorities include Zhuang (Thai), Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur (Turkic), Hmong and Korean.

Putonghua (Standard Mandarin, literally Common Speech) is the official language and is based on the Beijing dialect of the Mandarin group of dialects spoken in northern and southwestern China. Standard Mandarin is the medium of instruction in education and is taught in all schools. It is the language used in the media, for formal purposes, and by the government. Non-Sinitic languages are co-official in some autonomic minority regions. Road signs in major Chinese cities are typically bilingual in Chinese and English.

"Vernacular Chinese" or "baihua" is the written standard based on the Mandarin dialect which has been in use since the early 20th century. An older written standard, Classical Chinese, was used by literati for thousands of years before the 20th century. Classical Chinese is still a part of the high school curriculum and is thus intelligible to some degree to many Chinese. Spoken variants other than Standard Mandarin are usually not written, except for Standard Cantonese (see Written Cantonese) which is sometimes used in informal contexts.

Chinese banknotes are multilingual and contain written scripts for Standard Mandarin (Chinese characters and Hanyu Pinyin), Zhuang (Roman alphabet), Tibetan (Tibetan alphabet), Uyghur (Arabic alphabet) and Mongolian (traditional Mongolian alphabet).

Religion

Main article: Religion in China

The People's Republic of China is officially secular and atheist but it does allow personal religion or supervised religious organization. Buddhism (佛教) and Taoism (道教), along with an underlying Confucian morality, have been the dominant religions of Chinese society for almost two millennia. Personal religion has been more widely tolerated in the PRC today, so there has been a resurrection of interest in Buddhism and Taoism in the past decade. The main tradition of Buddhism practiced by the Chinese is Mahayana Buddhism (大乘) and its subsets Pure Land (淨土宗) and Zen (禪/禅宗) are the most common. Among the younger, urban secular population, Taoist spiritual ideas of Feng Shui have become popular in recent years, spawning a large home decoration market in China. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the United States reports that in addition to unknown numbers of adherents of Taoism and Buddhism,

- 3%-4% Chinese from the PRC are adherents of Christianity and

- 1%-2% Chinese from the PRC are adherents of Islam.

In recent years Falun Gong, developed in the 1990s, has attracted great controversy after the government labeled it a malicious cult and attempted to eradicate it. The Falun Gong itself denies that it is a cult or a religion. The Falun Gong claims approximately 70-100 million followers, a number which is rejected by foreign independent groups and the Chinese government, though exact numbers are unknown.

Religion and ancient Chinese traditions are widely tolerated in the Republic of China, and play a big role in the daily lives of modern Taiwanese people. According to the official figures released by the CIA:

- 93% of Taiwanese are adherents of a combination of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism.

- 2.5% of Taiwanese are adherents of other religions, such as Islam, Judaism, and others.

- 4.5% of Taiwanese are adherents of Christianity, this group includes a combination of Protestants, Catholics, Mormons, and other non-denominational Christian groups.

Culture

Main article: Culture of ChinaConfucianism was the official philosophy throughout most of Imperial China's history, and mastery of Confucian texts was the primary criterion for entry into the imperial bureaucracy. The literary emphasis of the exams affected the general perception of cultural refinement in China, e.g. the view that calligraphy was a higher art form than painting or drama. China's traditional values were derived from various versions of Confucianism and conservatism. A number of more authoritarian strains of thought have also been influential, such as Legalism. There was often conflict between the philosophies, e.g. the individualistic Song Dynasty neo-Confucians believed Legalism departed from the original spirit of Confucianism. Examinations and a culture of merit remain greatly valued in China today. In recent years, a number of New Confucians have advocated that democratic ideals and human rights are quite compatible with traditional Confucian "Asian values".

With the rise of Western economic and military power beginning in the mid-19th century, non-Chinese systems of social and political organization gained adherents in China. Some of these would-be reformers totally rejected China's cultural legacy, while others sought to combine the strengths of Chinese and Western cultures. In essence, the history of 20th century China is one of experimentation with new systems of social, political, and economic organization that would allow for the reintegration of the nation in the wake of dynastic collapse.

The first leaders of the PRC were born in the old society but were influenced by the May Fourth Movement and reformist ideals. They sought to change some traditional aspects of Chinese culture, such as rural land tenure, sexism, and Confucian education, while preserving others, such as the family structure and obedience to the state. Many observers believe that the period following 1949 is a continuation of traditional Chinese dynastic history. Others say that the CPC's rule and the Cultural Revolution have damaged the foundations of Chinese culture, asserting that many important aspects of traditional Chinese morals and culture, such as Confucianism, Chinese art, literature, and performing arts like Beijing opera were altered to conform to government policies and communist propaganda. The institution of the Simplified Chinese orthography reform is controversial as well.

Today, the PRC government has accepted much of traditional Chinese culture as an integral part of Chinese society, calling it an important achievement of the Chinese civilization and vital to the formation of a Chinese national identity.

Chinese films have enjoyed box office success abroad, introducing both exotic and mundane elements of Chinese culture across the world. In the last two decades, China has become a hotbed of filmmaking with such films as Farewell My Concubine, In the Mood for Love, 2046, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon (Taiwan), Yi Yi (Taiwan), Hero, Infernal Affairs, Suzhou River, The Road Home and House of Flying Daggers being critically acclaimed around the world.

See also: Chinese law and Chinese philosophyArts, scholarship, and literature

Chinese characters have had many variants and styles throughout Chinese history. Tens of thousands of ancient written documents are still extant, from Oracle bones to Qing edicts. Calligraphy is a major art form in China, more highly regarded than painting and music. Manuscripts of the Classics and religious texts (mainly Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist) were handwritten by ink brush. Calligraphy later became commercialized, and works by famous artists became prized possessions.

Printmaking was developed during the Song Dynasty. Academies of scholars sponsored by the empire were formed to comment on the classics in both printed and handwritten form. Royalty frequently participated in these discussions.

For centuries, economic and social advancement in China could be provided by high performance on the imperial examinations. This led to a meritocracy, although it was available only to males who could afford test preparation. Imperial examinations required applicants to write essays and demonstrate mastery of the Confucian classics. Those who passed the highest level of the exam became elite scholar-officials known as jinshi, a highly esteemed socio-economic position.

Chinese philosophers, writers, and poets were highly respected, and played key roles in preserving and promoting the culture of the empire. Some classical scholars, however, were noted for their daring depictions of the lives of the common people, often to the displeasure of authorities.

The Chinese invented numerous musical instruments, such as the zheng (箏, zither with movable bridges), qin (琴, bridgeless zither), sheng (笙, free reed), xiao (箫 or 簫, end blown flute) and adopted and developed others such the erhu (二胡, bowed lute) and pipa (plucked lute), many of which have later spread throughout East Asia and Southeast Asia, particularly to Japan, Korea and Vietnam.

See also: Chinese art, Chinese painting, Chinese paper art, Chinese calligraphy, Chinese poetry, Cinema of China, and Music of ChinaSports and recreation

Main article: Sports in China

There is evidence that a form of football (i.e. soccer) was first played in China around 1000 CE, leading many historians to believe that it originated there.. Besides football, the most popular sports are martial arts, table tennis, badminton and more recently, golf. Basketball is especially popular with the young, in urban centers where space is limited.

There are also many traditional sports. Chinese dragon boat racing occurs during the Duan Wu festival. In Inner Mongolia, Mongolian-style wrestling and horse racing are popular. In Tibet, archery and equestrian sports are part of traditional festivals.

China has become a sports power in the Asian region and around the world. China finished first in medal counts in each of the Asian Games since 1982, and in the top four in medal counts in each of the Summer Olympic Games since 1992. The 2008 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XXIX Olympiad, will be held in Beijing, China.

Physical fitness is highly regarded. Morning exercises are a common activity and the elderly are often seen practicing qigong in parks.

Board games such as International Chess, Go (Weiqi), and Xiangqi (Chinese chess) are also common and have organised formal competitions.

Science and technology

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Scientific achievements:

- Mathematics, applied to architecture and geography. Pi (π) was calculated by 5th century mathematician Zu Chongzhi to the seventh digit. The decimal system was used in China as early as the 14th Century BCE. Pascal's Triangle, known as Yanghui Triangle in China, was discovered by mathematicians Chia Hsien, Yang Hui, Zhu Shijie and Liu Ju-Hsieh, about 500 years before Blaise Pascal was born.

- Biology, such as pharmacopoeias of medicinal plants.

- Traditional medicine and surgery have achieved recognition over the last few decades in the West as alternative and complementary therapies.

Technical inventions attributed to China (some of them only allegedly):

| Military | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Naval | |||

| |||

| Flying | |||

| Paper | |||

| |||

| Measurement and Navigation | |||

| Metalurgy | |||

| |||

| Vary | |||

|

| ||

See also

- China as an emerging superpower

- Chinese calendar

- Chinese Century

- Chinese cuisine

- Chinese dragon

- Chinese name

- Chinese nationalism

- Chinese New Year

- Chinese units of measurement

- Culture of China

- Fenghuang

- History of postage in China

- Military history of China

- Overseas Chinese

Notes

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed (AHD4). Boston and New York, Houghton-Mifflin, 2000, entries china, Qin, Sino-.

- "Beijing hit by eighth sandstorm". BBC news. Accessed 17 April, 2006.

- ^ Languages. 2005. GOV.cn. URL accessed 3 May 2006. Cite error: The named reference "language" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Law of the People's Republic of China on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language (Order of the President No.37). 2005. GOV.cn. URL accessed 15 May 2006.

- Bary, Theodore de. "Constructive Engagement with Asian Values". Columbia University.

- Origins of the Great Game. 2000. Athleticscholarships.net. Accessed 23 April 2006.

- Qinfa, Ye. Sports History of China. About.com. Retrieved April 21, 2006.

- http://www.dohaasiangames.org/en/asian_games_2006/history.html

- http://www.olympic.org/uk/games/index_uk.asp

External links

- Video travel guide in China.

- Interactive China map with province and city guides.

- China Digital Times Online China news portal, run by the Graduate School of Journalism of University of California at Berkeley.

- Doing Business in China World Bank Group's guide

- Enterprise Surveys: China

- Infrastructure Projects Database: China

- Privatization Database: China

- NY Inquirer: China's 21st Century