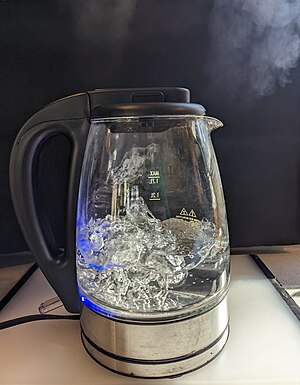

The boiling point of a substance is the temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid equals the pressure surrounding the liquid and the liquid changes into a vapor.

The boiling point of a liquid varies depending upon the surrounding environmental pressure. A liquid in a partial vacuum, i.e., under a lower pressure, has a lower boiling point than when that liquid is at atmospheric pressure. Because of this, water boils at 100°C (or with scientific precision: 99.97 °C (211.95 °F)) under standard pressure at sea level, but at 93.4 °C (200.1 °F) at 1,905 metres (6,250 ft) altitude. For a given pressure, different liquids will boil at different temperatures.

The normal boiling point (also called the atmospheric boiling point or the atmospheric pressure boiling point) of a liquid is the special case in which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the defined atmospheric pressure at sea level, one atmosphere. At that temperature, the vapor pressure of the liquid becomes sufficient to overcome atmospheric pressure and allow bubbles of vapor to form inside the bulk of the liquid. The standard boiling point has been defined by IUPAC since 1982 as the temperature at which boiling occurs under a pressure of one bar.

The heat of vaporization is the energy required to transform a given quantity (a mol, kg, pound, etc.) of a substance from a liquid into a gas at a given pressure (often atmospheric pressure).

Liquids may change to a vapor at temperatures below their boiling points through the process of evaporation. Evaporation is a surface phenomenon in which molecules located near the liquid's edge, not contained by enough liquid pressure on that side, escape into the surroundings as vapor. On the other hand, boiling is a process in which molecules anywhere in the liquid escape, resulting in the formation of vapor bubbles within the liquid.

Saturation temperature and pressure

A saturated liquid contains as much thermal energy as it can without boiling (or conversely a saturated vapor contains as little thermal energy as it can without condensing).

Saturation temperature means boiling point. The saturation temperature is the temperature for a corresponding saturation pressure at which a liquid boils into its vapor phase. The liquid can be said to be saturated with thermal energy—any addition of thermal energy results in a phase transition.

If the pressure in a system remains constant (isobaric), a vapor at saturation temperature will begin to condense into its liquid phase as thermal energy (heat) is removed. Similarly, a liquid at saturation temperature and pressure will boil into its vapor phase as additional thermal energy is applied.

The boiling point corresponds to the temperature at which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the surrounding environmental pressure. Thus, the boiling point is dependent on the pressure. Boiling points may be published with respect to the NIST, USA standard pressure of 101.325 kPa (1 atm), or the IUPAC standard pressure of 100.000 kPa (1 bar). At higher elevations, where the atmospheric pressure is much lower, the boiling point is also lower. The boiling point increases with increased pressure up to the critical point, where the gas and liquid properties become identical. The boiling point cannot be increased beyond the critical point. Likewise, the boiling point decreases with decreasing pressure until the triple point is reached. The boiling point cannot be reduced below the triple point.

Suppose the heat of vaporization and the vapor pressure of a liquid at a certain temperature are known. In that case, the boiling point can be calculated by using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation, thus:

where:

- is the boiling point at the pressure of interest,

- is the ideal gas constant,

- is the vapor pressure of the liquid,

- is some pressure where the corresponding is known (usually data available at 1 atm or 100 kPa (1 bar)),

- is the heat of vaporization of the liquid,

- is the boiling temperature,

- is the natural logarithm.

Saturation pressure is the pressure for a corresponding saturation temperature at which a liquid boils into its vapor phase. Saturation pressure and saturation temperature have a direct relationship: as saturation pressure is increased, so is saturation temperature.

If the temperature in a system remains constant (an isothermal system), vapor at saturation pressure and temperature will begin to condense into its liquid phase as the system pressure is increased. Similarly, a liquid at saturation pressure and temperature will tend to flash into its vapor phase as system pressure is decreased.

There are two conventions regarding the standard boiling point of water: The normal boiling point is commonly given as 100 °C (212 °F) (actually 99.97 °C (211.9 °F) following the thermodynamic definition of the Celsius scale based on the kelvin) at a pressure of 1 atm (101.325 kPa). The IUPAC-recommended standard boiling point of water at a standard pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar) is 99.61 °C (211.3 °F). For comparison, on top of Mount Everest, at 8,848 m (29,029 ft) elevation, the pressure is about 34 kPa (255 Torr) and the boiling point of water is 71 °C (160 °F). The Celsius temperature scale was defined until 1954 by two points: 0 °C being defined by the water freezing point and 100 °C being defined by the water boiling point at standard atmospheric pressure.

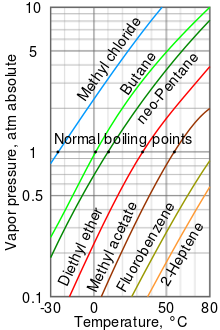

Relation between the normal boiling point and the vapor pressure of liquids

The higher the vapor pressure of a liquid at a given temperature, the lower the normal boiling point (i.e., the boiling point at atmospheric pressure) of the liquid.

The vapor pressure chart to the right has graphs of the vapor pressures versus temperatures for a variety of liquids. As can be seen in the chart, the liquids with the highest vapor pressures have the lowest normal boiling points.

For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (−24.2 °C), which is where the vapor pressure curve of methyl chloride (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one atmosphere (atm) of absolute vapor pressure.

The critical point of a liquid is the highest temperature (and pressure) it will actually boil at.

See also Vapour pressure of water.

Boiling point of chemical elements

Further information: List of chemical elements and Boiling points of the elements (data page)The element with the lowest boiling point is helium. Both the boiling points of rhenium and tungsten exceed 5000 K at standard pressure; because it is difficult to measure extreme temperatures precisely without bias, both have been cited in the literature as having the higher boiling point.

Boiling point as a reference property of a pure compound

As can be seen from the above plot of the logarithm of the vapor pressure vs. the temperature for any given pure chemical compound, its normal boiling point can serve as an indication of that compound's overall volatility. A given pure compound has only one normal boiling point, if any, and a compound's normal boiling point and melting point can serve as characteristic physical properties for that compound, listed in reference books. The higher a compound's normal boiling point, the less volatile that compound is overall, and conversely, the lower a compound's normal boiling point, the more volatile that compound is overall. Some compounds decompose at higher temperatures before reaching their normal boiling point, or sometimes even their melting point. For a stable compound, the boiling point ranges from its triple point to its critical point, depending on the external pressure. Beyond its triple point, a compound's normal boiling point, if any, is higher than its melting point. Beyond the critical point, a compound's liquid and vapor phases merge into one phase, which may be called a superheated gas. At any given temperature, if a compound's normal boiling point is lower, then that compound will generally exist as a gas at atmospheric external pressure. If the compound's normal boiling point is higher, then that compound can exist as a liquid or solid at that given temperature at atmospheric external pressure, and will so exist in equilibrium with its vapor (if volatile) if its vapors are contained. If a compound's vapors are not contained, then some volatile compounds can eventually evaporate away in spite of their higher boiling points.

In general, compounds with ionic bonds have high normal boiling points, if they do not decompose before reaching such high temperatures. Many metals have high boiling points, but not all. Very generally—with other factors being equal—in compounds with covalently bonded molecules, as the size of the molecule (or molecular mass) increases, the normal boiling point increases. When the molecular size becomes that of a macromolecule, polymer, or otherwise very large, the compound often decomposes at high temperature before the boiling point is reached. Another factor that affects the normal boiling point of a compound is the polarity of its molecules. As the polarity of a compound's molecules increases, its normal boiling point increases, other factors being equal. Closely related is the ability of a molecule to form hydrogen bonds (in the liquid state), which makes it harder for molecules to leave the liquid state and thus increases the normal boiling point of the compound. Simple carboxylic acids dimerize by forming hydrogen bonds between molecules. A minor factor affecting boiling points is the shape of a molecule. Making the shape of a molecule more compact tends to lower the normal boiling point slightly compared to an equivalent molecule with more surface area.

| Common name | n-butane | isobutane |

|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name | butane | 2-methylpropane |

| Molecular form |

|

|

| Boiling point (°C) |

−0.5 | −11.7 |

| Common name | n-pentane | isopentane | neopentane |

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name | pentane | 2-methylbutane | 2,2-dimethylpropane |

| Molecular form |

|

|

|

| Boiling point (°C) |

36.0 | 27.7 | 9.5 |

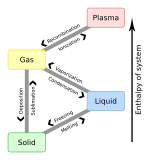

Most volatile compounds (anywhere near ambient temperatures) go through an intermediate liquid phase while warming up from a solid phase to eventually transform to a vapor phase. By comparison to boiling, a sublimation is a physical transformation in which a solid turns directly into vapor, which happens in a few select cases such as with carbon dioxide at atmospheric pressure. For such compounds, a sublimation point is a temperature at which a solid turning directly into vapor has a vapor pressure equal to the external pressure.

Impurities and mixtures

In the preceding section, boiling points of pure compounds were covered. Vapor pressures and boiling points of substances can be affected by the presence of dissolved impurities (solutes) or other miscible compounds, the degree of effect depending on the concentration of the impurities or other compounds. The presence of non-volatile impurities such as salts or compounds of a volatility far lower than the main component compound decreases its mole fraction and the solution's volatility, and thus raises the normal boiling point in proportion to the concentration of the solutes. This effect is called boiling point elevation. As a common example, salt water boils at a higher temperature than pure water.

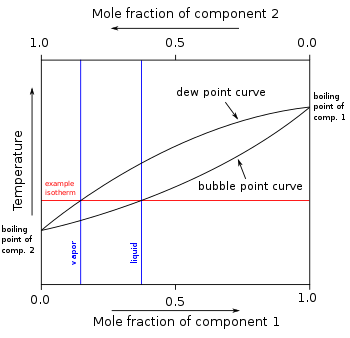

In other mixtures of miscible compounds (components), there may be two or more components of varying volatility, each having its own pure component boiling point at any given pressure. The presence of other volatile components in a mixture affects the vapor pressures and thus boiling points and dew points of all the components in the mixture. The dew point is a temperature at which a vapor condenses into a liquid. Furthermore, at any given temperature, the composition of the vapor is different from the composition of the liquid in most such cases. In order to illustrate these effects between the volatile components in a mixture, a boiling point diagram is commonly used. Distillation is a process of boiling and condensation which takes advantage of these differences in composition between liquid and vapor phases.

Boiling point of water with elevation

Following is a table of the change in the boiling point of water with elevation, at intervals of 500 meters over the range of human habitation , then of 1,000 meters over the additional range of uninhabited surface elevation , along with a similar range in Imperial.

| Elevation (m) |

Boiling point (°C) |

Elevation (ft) |

Boiling point (°F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −500 | 101.6 | −1,500 | 214.7 | |

| 0 | 100.0 | 0 | 212.0 | |

| 500 | 98.4 | 1,500 | 209.3 | |

| 1,000 | 96.7 | 3,000 | 206.6 | |

| 1,500 | 95.1 | 4,500 | 203.9 | |

| 2,000 | 93.4 | 6,000 | 201.1 | |

| 2,500 | 91.7 | 7,500 | 198.3 | |

| 3,000 | 90.0 | 9,000 | 195.5 | |

| 3,500 | 88.2 | 10,500 | 192.6 | |

| 4,000 | 86.4 | 12,000 | 189.8 | |

| 4,500 | 84.6 | 13,500 | 186.8 | |

| 5,000 | 82.8 | 15,000 | 183.9 | |

| 6,000 | 79.1 | 16,500 | 180.9 | |

| 7,000 | 75.3 | 20,000 | 173.8 | |

| 8,000 | 71.4 | 23,000 | 167.5 | |

| 9,000 | 67.4 | 26,000 | 161.1 | |

| 29,000 | 154.6 |

Element table

Main article: Boiling points of the elements (data page)| Boiling point of the elements in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group → | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||

| ↓ Period | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H2 20.271 K (−252.879 °C) |

He4.222 K (−268.928 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li1603 K (1330 °C) |

Be2742 K (2469 °C) |

B 4200 K (3927 °C) |

C 3915 K (subl.) (3642 °C) |

N2 77.355 K (−195.795 °C) |

O2 90.188 K (−182.962 °C) |

F2 85.03 K (−188.11 °C) |

Ne27.104 K (−246.046 °C) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na1156.090 K (882.940 °C) |

Mg1363 K (1091 °C) |

Al2743 K (2470 °C) |

Si3538 K (3265 °C) |

P 553.7 K (280.5 °C) |

S 717.8 K (444.6 °C) |

Cl2239.11 K (−34.04 °C) |

Ar87.302 K (−185.848 °C) | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | K 1032 K (759 °C) |

Ca1757 K (1484 °C) |

Sc3109 K (2836 °C) |

Ti3560 K (3287 °C) |

V 3680 K (3407 °C) |

Cr2945.15 K (2672.0 °C) |

Mn2334 K (2061 °C) |

Fe3134 K (2861 °C) |

Co3200 K (2927 °C) |

Ni3003 K (2730 °C) |

Cu2835 K (2562 °C) |

Zn1180 K (907 °C) |

Ga2673 K (2400 °C) |

Ge3106 K (2833 °C) |

As887 K (subl.) (615 °C) |

Se958 K (685 °C) |

Br2332.0 K (58.8 °C) |

Kr119.735 K (−153.415 °C) | |||||

| 5 | Rb961 K (688 °C) |

Sr1650 K (1377 °C) |

Y 3203 K (2930 °C) |

Zr4650 K (4377 °C) |

Nb5017 K (4744 °C) |

Mo4912 K (4639 °C) |

Tc4538 K (4265 °C) |

Ru4423 K (4150 °C) |

Rh3968 K (3695 °C) |

Pd3236 K (2963 °C) |

Ag2483 K (2210 °C) |

Cd1040 K (767 °C) |

In2345 K (2072 °C) |

Sn2875 K (2602 °C) |

Sb1908 K (1635 °C) |

Te1261 K (988 °C) |

I2 457.4 K (184.3 °C) |

Xe165.051 K (−108.099 °C) | |||||

| 6 | Cs944 K (671 °C) |

Ba2118 K (1845 °C) |

Lu3675 K (3402 °C) |

Hf4876 K (4603 °C) |

Ta5731 K (5458 °C) |

W 6203 K (5930 °C) |

Re5900.15 K (5627.0 °C) |

Os5285 K (5012 °C) |

Ir4403 K (4130 °C) |

Pt4098 K (3825 °C) |

Au3243 K (2970 °C) |

Hg629.88 K (356.73 °C) |

Tl1746 K (1473 °C) |

Pb2022 K (1749 °C) |

Bi1837 K (1564 °C) |

Po1235 K (962 °C) |

At2503±3 K (230±3 °C) |

Rn211.5 K (−61.7 °C) | |||||

| 7 | Fr950 K (677 °C) |

Ra2010 K (1737 °C) |

Lr | Rf5800 K (5500 °C) |

Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn340±10 K (67±10 °C) |

Nh1430 K (1130 °C) |

Fl380 K (107 °C) |

Mc~1400 K (~1100 °C) |

Lv1035–1135 K (762–862 °C) |

Ts883 K (610 °C) |

Og450±10 K (177±10 °C) | |||||

| La3737 K (3464 °C) |

Ce3716 K (3443 °C)6 |

Pr3403 K (3130 °C) |

Nd3347 K (3074 °C) |

Pm3273 K (3000 °C) |

Sm2173 K (1900 °C) |

Eu1802 K (1529 °C) |

Gd3546 K (3273 °C) |

Tb3396 K (3123 °C) |

Dy2840 K (2567 °C) |

Ho2873 K (2600 °C) |

Er3141 K (2868 °C) |

Tm2223 K (1950 °C) |

Yb1469 K (1196 °C) | ||||||||||

| Ac3471 K (3198 °C) |

Th5061 K (4788 °C) |

Pa4300? K (4027 °C) |

U 4404 K (4131 °C) |

Np4175.15 K (3902.0 °C) |

Pu3508.15 K (3235.0 °C) |

Am2880 K (2607 °C) |

Cm3383 K (3110 °C) |

Bk2900 K (2627 °C) |

Cf1743 K (1470 °C) |

Es1269 (996 °C) |

Fm | Md | No | ||||||||||

| Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Values are in kelvin K and degrees Celsius °C, rounded | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| For the equivalent in degrees Fahrenheit °F, see: Boiling points of the elements (data page) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some values are predictions | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Primordial From decay Synthetic Border shows natural occurrence of the element

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Boiling points of the elements (data page)

- Boiling-point elevation

- Critical point (thermodynamics)

- Ebulliometer, a device to accurately measure the boiling point of liquids

- Hagedorn temperature

- Joback method (Estimation of normal boiling points from molecular structure)

- List of gases including boiling points

- Melting point

- Subcooling

- Superheating

- Trouton's constant relating latent heat to boiling point

- Triple point

References

- Goldberg, David E. (1988). 3,000 Solved Problems in Chemistry (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill. section 17.43, p. 321. ISBN 0-07-023684-4.

- Theodore, Louis; Dupont, R. Ryan; Ganesan, Kumar, eds. (1999). Pollution Prevention: The Waste Management Approach to the 21st Century. CRC Press. section 27, p. 15. ISBN 1-56670-495-2.

- "Boiling Point of Water and Altitude". www.engineeringtoolbox.com.

- General Chemistry Glossary Purdue University website page

- Reel, Kevin R.; Fikar, R. M.; Dumas, P. E.; Templin, Jay M. & Van Arnum, Patricia (2006). AP Chemistry (REA) – The Best Test Prep for the Advanced Placement Exam (9th ed.). Research & Education Association. section 71, p. 224. ISBN 0-7386-0221-3.

- ^ Cox, J. D. (1982). "Notation for states and processes, significance of the word standard in chemical thermodynamics, and remarks on commonly tabulated forms of thermodynamic functions". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 54 (6): 1239–1250. doi:10.1351/pac198254061239.

- Standard Pressure IUPAC defines the "standard pressure" as being 10 Pa (which amounts to 1 bar).

- Appendix 1: Property Tables and Charts (SI Units), Scroll down to Table A-5 and read the temperature value of 99.61 °C at a pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar). Obtained from McGraw-Hill's Higher Education website.

- West, J. B. (1999). "Barometric pressures on Mt. Everest: New data and physiological significance". Journal of Applied Physiology. 86 (3): 1062–6. doi:10.1152/jappl.1999.86.3.1062. PMID 10066724. S2CID 27875962.

- Perry, R.H.; Green, D.W., eds. (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049841-5.

- DeVoe, Howard (2000). Thermodynamics and Chemistry (1st ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-02-328741-1.

External links

| States of matter (list) | ||

|---|---|---|

| State |  | |

| Low energy | ||

| High energy | ||

| Other states | ||

| Phase transitions |

| |

| Quantities | ||

| Concepts | ||

is the boiling point at the pressure of interest,

is the boiling point at the pressure of interest, is the

is the  is the

is the  is some pressure where the corresponding

is some pressure where the corresponding  is known (usually data available at 1 atm or 100 kPa (1 bar)),

is known (usually data available at 1 atm or 100 kPa (1 bar)), is the

is the  is the

is the