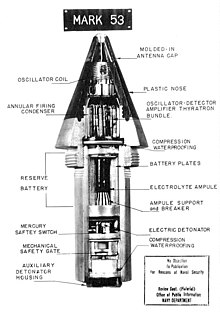

In military munitions, a fuze (sometimes fuse) is the part of the device that initiates its function. In some applications, such as torpedoes, a fuze may be identified by function as the exploder. The relative complexity of even the earliest fuze designs can be seen in cutaway diagrams.

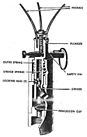

A fuze is a device that detonates a munition's explosive material under specified conditions. In addition, a fuze will have safety and arming mechanisms that protect users from premature or accidental detonation. For example, an artillery fuze's battery is activated by the high acceleration of cannon launch, and the fuze must be spinning rapidly before it will function. "Complete bore safety" can be achieved with mechanical shutters that isolate the detonator from the main charge until the shell is fired.

A fuze may contain only the electronic or mechanical elements necessary to signal or actuate the detonator, but some fuzes contain a small amount of primary explosive to initiate the detonation. Fuzes for large explosive charges may include an explosive booster.

Etymology

Some professional publications about explosives and munitions distinguish the "fuse" and "fuze" spelling. The UK Ministry of Defence states (emphasis in original):

- Fuse: Cord or tube for the transmission of flame or explosion usually consisting of cord or rope with gunpowder or high explosive spun into it. (The spelling fuze may also be met for this term, but fuse is the preferred spelling in this context.)

- Fuze: A device with explosive components designed to initiate a main charge. (The spelling fuse may also be met for this term, but fuze is the preferred spelling in this context.)

Historically, it was spelled with either 's' or 'z', and both spellings can still be found. In the United States and some military forces, fuze is used to denote a sophisticated ignition device incorporating mechanical and/or electronic components (for example a proximity fuze for an artillery shell, magnetic/acoustic fuze on a sea mine, spring-loaded grenade fuze, pencil detonator or anti-handling device) as opposed to a simple burning fuse.

Munition types

The situation of usage and the characteristics of the munition it is intended to activate affect the fuze design e.g. its safety and actuation mechanisms.

- Artillery

- Artillery fuzes are tailored to function in the special circumstances of artillery projectiles. The relevant factors are the projectile's initial rapid acceleration, high velocity and usually rapid rotation, which affect both safety and arming requirements and options, and the target may be moving or stationary. Artillery fuzes may be initiated by a timer mechanism, impact or detection of proximity to the target, or a combination of these.

- Grenades

- Requirements for a grenade fuze are defined by the projectile's small size and slow delivery over a short distance. This necessitates manual arming before throwing as the grenade has insufficient initial acceleration for arming to be driven by "setback" and no rotation to drive arming by centrifugal force.

- Aerial bombs

- Aerial bombs can be detonated either by a fuze, which contains a small explosive charge to initiate the main charge, or by a "pistol", a firing pin in a case which strikes the detonator when triggered. The pistol may be considered a part of the mechanical fuze assembly.

- Landmines

- The main design consideration is that the bomb that the fuze is intended to actuate is stationary, and the target itself is moving in making contact.

- Naval mines

- Relevant design factors in naval mine fuzes are that the mine may be static or moving downward through the water, and the target is typically moving on or below the water surface, usually above the mine.

Activation mechanisms

Time

Time fuzes detonate after a set period of time by using one or more combinations of mechanical, electronic, pyrotechnic or even chemical timers. Depending on the technology used, the device may self-destruct (or render itself safe without detonation) some seconds, minutes, hours, days, or even months after being deployed.

Early artillery time fuzes were nothing more than a hole filled with gunpowder leading from the surface to the centre of the projectile. The flame from the burning of the gunpowder propellant ignited this "fuze" on firing, and burned through to the centre during flight, then igniting or exploding whatever the projectile may have been filled with.

By the 19th century devices more recognisable as modern artillery "fuzes" were being made of carefully selected wood and trimmed to burn for a predictable time after firing. These were still typically fired from smoothbore muzzle-loaders with a relatively large gap between the shell and barrel, and still relied on flame from the gunpowder propellant charge escaping past the shell on firing to ignite the wood fuze and hence initiate the timer.

In the mid-to-late 19th century adjustable metal time fuzes, the fore-runners of today's time fuzes, containing burning gunpowder as the delay mechanism became common, in conjunction with the introduction of rifled artillery. Rifled guns introduced a tight fit between shell and barrel and hence could no longer rely on the flame from the propellant to initiate the timer. The new metal fuzes typically use the shock of firing ("setback") and/or the projectiles's rotation to "arm" the fuze and initiate the timer : hence introducing a safety factor previously absent.

As late as World War I, some countries were still using hand-grenades with simple black match fuses much like those of modern fireworks: the infantryman lit the fuse before throwing the grenade and hoped the fuse burned for the several seconds intended. These were soon superseded in 1915 by the Mills bomb, the first modern hand grenade with a relatively safe and reliable time fuze initiated by pulling out a safety pin and releasing an arming handle on throwing.

Modern time fuzes often use an electronic delay system.

Impact

Main article: Contact fuzeImpact, percussion or contact fuzes detonate when their forward motion rapidly decreases, typically on physically striking an object such as the target. The detonation may be instantaneous or deliberately delayed to occur a preset fraction of a second after penetration of the target. An instantaneous "Superquick" fuze will detonate instantly on the slightest physical contact with the target. A fuze with a graze action will also detonate on change of direction caused by a slight glancing blow on a physical obstruction such as the ground.

Impact fuzes in artillery usage may be mounted in the shell nose ("point detonating") or shell base ("base detonating").

Inertia

Inertial fuzes are triggered when the entity carrying them (for example, a torpedo, air-dropped bomb, sea mine, or booby trap) experiences a sudden (or gradual, depending on the design) acceleration, deceleration, or impact. In this way they are both similar to and different from impact fuzes. Whereas impact fuzes usually require physical contact with, or an impact against a hard surface, inertial fuzes can trigger from any change of momentum. This allows them to be mounted deep inside the entity carrying them, rather than on its exterior. Designs can be varied. Some can be passively safe, ignoring all changes of momentum below a certain threshold, thereby functioning similarly to impact fuzes without the limitation of being externally mounted. Other designs can be passively dangerous, using other energy sources such as gravity or an electrical battery to greatly amplify slight changes in inertia over time. One easy way of visualizing a passively safe inertial fuze is to picture a marble in a bowl - the device is triggered when the marble rolls to the rim of the bowl. In contrast, a passively dangerous inertial fuze would be similar to a marble on a smooth, flat plate. The former uses gravity to actively suppress weak forces acting on the marble, whereas the latter uses gravity to actively amplify them. Passively dangerous inertial fuzes are commonly employed in anti-handling devices.

For comparatively low-velocity munitions such as torpedoes, inertial fuzes of the pendulum and swing-arm types have been used historically. An early example of a pendulum fuze can be seen in the design of the Brennan torpedo. Inertial fuzing is also used in the design of HESH munitions, since their concept precludes the use of contact fuzing.

Proximity

Main article: Proximity fuze

Proximity fuzes cause a missile warhead or other munition (e.g. air-dropped bomb or sea mine) to detonate when it comes within a certain pre-set distance of the target, or vice versa. Proximity fuzes utilize sensors incorporating one or more combinations of the following: radar, active sonar, passive acoustic, infrared, magnetic, photoelectric, seismic or even television cameras. These may take the form of an anti-handling device designed specifically to kill or severely injure anyone who tampers with the munition in some way e.g. lifting or tilting it. Regardless of the sensor used, the pre-set triggering distance is calculated such that the explosion will occur sufficiently close to the target that it is either destroyed or severely damaged.

Remote detonation

Remote detonators use wires or radio waves to remotely command the device to detonate.

Barometric

Barometric fuzes cause a bomb to detonate at a certain pre-set altitude above sea level by means of a radar, barometric altimeter or an infrared rangefinder.

Combinations

A fuze assembly may include more than one fuze in series or parallel arrangements. The RPG-7 usually has an impact (PIBD) fuze in parallel with a 4.5 second time fuze, so detonation should occur on impact, but otherwise takes place after 4.5 seconds. Military weapons containing explosives have fuzing systems including a series time fuze to ensure that they do not initiate (explode) prematurely within a danger distance of the munition launch platform. In general, the munition has to travel a certain distance, wait for a period of time (via a clockwork, electronic or chemical delay mechanism), or have some form of arming pin or plug removed. Only when these processes have occurred will the arming process of the series time fuze be complete. Mines often have a parallel time fuze to detonate and destroy the mine after a pre-determined period to minimize casualties after the anticipated duration of hostilities. Detonation of modern naval mines may require simultaneous detection of a series arrangement of acoustic, magnetic, and/or pressure sensors to complicate mine-sweeping efforts.

Safety and arming mechanisms

The multiple safety/arming features in the M734 fuze used for mortars are representative of the sophistication of modern electronic fuzes.

Safety/arming mechanisms can be as simple as the spring-loaded safety levers on M67 or RGD-5 grenade fuzes, which will not initiate the explosive train so long as the pin is kept in the grenade, or the safety lever is held down on a pinless grenade. Alternatively, it can be as complex as the electronic timer-countdown on an influence sea mine, which gives the vessel laying it sufficient time to move out of the blast zone before the magnetic or acoustic sensors are fully activated.

In modern artillery shells, most fuzes incorporate several safety features to prevent a fuze arming before it leaves the gun barrel. These safety features may include arming on "setback" or by centrifugal force, and often both operating together. Set-back arming uses the inertia of the accelerating artillery shell to remove a safety feature as the projectile accelerates from rest to its in-flight speed. Rotational arming requires that the artillery shell reach a certain rpm before centrifugal forces cause a safety feature to disengage or move an arming mechanism to its armed position. Artillery shells are fired through a rifled barrel, which forces them to spin during flight.

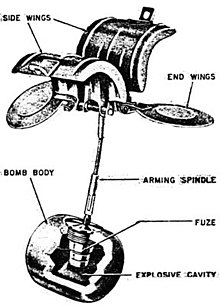

In other cases the bomb, mine or projectile has a fuze that prevents accidental initiation e.g. stopping the rotation of a small propeller (unless a lanyard pulls out a pin) so that the striker-pin cannot hit the detonator even if the weapon is dropped on the ground. These types of fuze operate with aircraft weapons, where the weapon may have to be jettisoned over friendly territory to allow a damaged aircraft to continue to fly. The crew can choose to jettison the weapons safe by dropping the devices with safety pins still attached, or drop them live by removing the safety pins as the weapons leave the aircraft.

Aerial bombs and depth charges can be nose and tail fuzed using different detonator/initiator characteristics so that the crew can choose which effect fuze will suit target conditions that may not have been known before the flight. The arming switch is set to one of safe, nose, or tail at the crew's choice.

Base fuzes are also used by artillery and tanks for shells of the 'squash head' type. Some types of armour piercing shells have also used base fuzes, as have nuclear artillery shells.

The most sophisticated fuze mechanisms of all are those fitted to nuclear weapons, and their safety/arming devices are correspondingly complex. In addition to PAL protection, the fuzing used in nuclear weapons features multiple, highly sophisticated environmental sensors e.g. sensors requiring highly specific acceleration and deceleration profiles before the warhead can be fully armed. The intensity and duration of the acceleration/deceleration must match the environmental conditions which the bomb/missile warhead would actually experience when dropped or fired. Furthermore, these events must occur in the correct order. As an additional safety precaution, most modern nuclear weapons utilize a timed two point detonation system such that ONLY a precisely firing of both detonators in sequence will result in the correct conditions to cause a fission reaction

Note: some fuzes, e.g. those used in air-dropped bombs and landmines may contain anti-handling devices specifically designed to kill bomb disposal personnel. The technology to incorporate booby-trap mechanisms in fuzes has existed since at least 1940 e.g. the German ZUS40 anti-removal bomb fuze.

Reliability

A fuze must be designed to function appropriately considering relative movement of the munition with respect to its target. The target may move past stationary munitions like land mines or naval mines; or the target may be approached by a rocket, torpedo, artillery shell, or air-dropped bomb. Timing of fuze function may be described as optimum if detonation occurs when target damage will be maximized, early if detonation occurs prior to optimum, late if detonation occurs past optimum, or dud if the munition fails to detonate. Any given batch of a specific design may be tested to determine the anticipated percentage of early, optimum. late, and dud expected from that fuze installation.

Combination fuze design attempts to maximize optimum detonation while recognizing dangers of early fuze function (and potential dangers of late function for subsequent occupation of the target zone by friendly forces or for gravity return of anti-aircraft munitions used in defense of surface positions.) Series fuze combinations minimize early function by detonating at the latest activation of the individual components. Series combinations are useful for safety arming devices, but increase the percentage of late and dud munitions. Parallel fuze combinations minimize duds by detonating at the earliest activation of individual components, but increase the possibility of premature early function of the munition. Sophisticated military munition fuzes typically contain an arming device in series with a parallel arrangement of sensing fuzes for target destruction and a time fuze for self-destruction if no target is detected.

Gallery

| This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. Please help improve the section by removing excessive or indiscriminate images or by moving relevant images beside adjacent text, in accordance with the Manual of Style on use of images. (August 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

-

Avro Lancaster at RAF Metheringham. Note the "Fuzed" status, chalked on the nose of each bomb

Avro Lancaster at RAF Metheringham. Note the "Fuzed" status, chalked on the nose of each bomb

-

Oerlikon 20 mm cannon fuze

Oerlikon 20 mm cannon fuze

-

Cross-sectional views of QF 2-pounder naval gun shells, showing percussion fuzes.

Cross-sectional views of QF 2-pounder naval gun shells, showing percussion fuzes.

-

Fuzes fitted to M107 155mm artillery shells, c. 2000

-

Fuzed 81mm white phosphorus mortar shell in 1980. Note spelling of "fuze" on adjacent boxes

Fuzed 81mm white phosphorus mortar shell in 1980. Note spelling of "fuze" on adjacent boxes

-

An assortment of fuzes for artillery and mortar shells

An assortment of fuzes for artillery and mortar shells

-

British World War II 4-inch naval illuminating shell, showing time fuze (orange, top), illuminating compound (green) and parachute (white, bottom)

British World War II 4-inch naval illuminating shell, showing time fuze (orange, top), illuminating compound (green) and parachute (white, bottom)

-

Fuze for a Stokes mortar shell

Fuze for a Stokes mortar shell

-

British No. 63 Mk I Time and Percussion fuze, c. 1915, used in shrapnel shells

British No. 63 Mk I Time and Percussion fuze, c. 1915, used in shrapnel shells

-

British No. 100 Graze Fuze for high-explosive shell, World War I.

British No. 100 Graze Fuze for high-explosive shell, World War I.

-

British Percussion Fuze No. 110 Mk III, World War I, used in trench mortars

British Percussion Fuze No. 110 Mk III, World War I, used in trench mortars

-

British No. 131 D.A. (Direct Action) Impact Fuze, Mk VI, World War I, used in anti-aircraft artillery

British No. 131 D.A. (Direct Action) Impact Fuze, Mk VI, World War I, used in anti-aircraft artillery

-

British No. 16 D Mk IV N Base percussion fuze, c. 1936

British No. 16 D Mk IV N Base percussion fuze, c. 1936

-

British No. 45 P Direct Action Impact Fuze, World War I, used in howitzer shells

British No. 45 P Direct Action Impact Fuze, World War I, used in howitzer shells

-

Cut-away diagram of Japanese Type 99 Grenade showing fuze mechanism. c. 1939

Cut-away diagram of Japanese Type 99 Grenade showing fuze mechanism. c. 1939

-

Cut-away diagram of a US M2A4 bounding mine showing the M6A1 pressure/pull fuze. c. 1950

Cut-away diagram of a US M2A4 bounding mine showing the M6A1 pressure/pull fuze. c. 1950

-

USSR pull-fuze designed for booby-trap or anti-handling purposes. c. 1950s. Detonator assembly is inserted into explosives

USSR pull-fuze designed for booby-trap or anti-handling purposes. c. 1950s. Detonator assembly is inserted into explosives

-

Alternative design of USSR booby-trap pull-fuze, usually connected to a tripwire. c. 1950s

Alternative design of USSR booby-trap pull-fuze, usually connected to a tripwire. c. 1950s

-

USSR pressure fuze for booby-trap purposes e.g. victim steps on loose floorboard with fuze (connected to TNT explosives) concealed underneath. c. 1950s

USSR pressure fuze for booby-trap purposes e.g. victim steps on loose floorboard with fuze (connected to TNT explosives) concealed underneath. c. 1950s

-

Italian TC/2.4 mine c. 1980s showing central location of mechanical pressure fuze

Italian TC/2.4 mine c. 1980s showing central location of mechanical pressure fuze

-

German S-mine dating from World War II showing fuze well into which a 3-pronged fuze would be screwed

German S-mine dating from World War II showing fuze well into which a 3-pronged fuze would be screwed

-

Fuze for a German S-mine, which would be screwed into the fuze well on the mine

Fuze for a German S-mine, which would be screwed into the fuze well on the mine

-

M4 anti tank mine, showing main fuze in the centre, plus 2 additional fuze pockets (both empty) which provide the option to fit anti-handling devices

-

Typical configuration of a pull fuze and/or pressure-release fuze attached to M15 anti-tank landmines

Typical configuration of a pull fuze and/or pressure-release fuze attached to M15 anti-tank landmines

-

The problem-prone Mark 6 magnetic influence exploder for the Mark 14 submarine torpedo was secretly developed with limited testing between the world wars

The problem-prone Mark 6 magnetic influence exploder for the Mark 14 submarine torpedo was secretly developed with limited testing between the world wars

See also

- Artillery fuze – Type of munition fuze used with artillery munitions

- Black match – Type of fuse made of cotton

- Contact fuze – Device that detonates bomb on contact with hard surface

- Slow match – Slow-burning cord or twine fuse

References

- Fairfield, Arthur P., CDR USN (1921). Naval Ordnance. Lord Baltimore Press. p. 24.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Young, C. G. (November 1920). "Notes on Fuze Design". Journal of the United States Artillery. 53 (5). Fort Monroe, VA: 484–508.

- Young 1920, p. 488

- Ministry of Defence (Army Dept.) 1968, p. 33,35

- Meyer, Rudolf; Koehler, Josef; Homburg, Axel (2007). Explosives (sixth, completely revised ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH. p. 145. ISBN 978-3-527-31656-4.

- Ministry of Defence (Army Dept.) 1968, p. 33

- Ministry of Defence (Army Dept.) 1968, p. 35

- "Proximity fuze". Oxford Reference.

citing The Oxford Companion to World War II Edited by: I. C. B. Dear and M. R. D. Foot. Oxford University Press 2001 ISBN 9780198604464

- "fuse | ignition device". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-01-14.

- "Chapter 14 Fuzing". Fundamentals of Naval Weapons Systems. Weapons and Systems Engineering Deptartment, United States Naval Academy – via Federation of American Scientists.

- "XM784 and XM785 Electronic Time Fuze For Mortars (ETFM)" (PDF). dtic.mil. 9 April 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- "Fuze Terminology and Basic Fuze Theory". The Ordnance Shop. Archived from the original on December 10, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- "Fuzes". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- "Grenade fuze". Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- "DUAL SAFETY GRENADE FUZE". Hamilton Watch Company. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- "ARMY EQUIPMENT DATA SHEETS AMMUNITION PECULIAR EQUIPMENT" (PDF). Military Newbie.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "A fuse is a wick or other combustible cord for an old-fashioned explosive. A fuze is for more high-tech explosives: it's a mechanical or electronic device used for detonations."Garner, Bryan A. (2000). The Oxford Dictionary of American Usage and Style. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195135084.

- "British bombs". Fuzes, Pistols and Detonators of WW2. Stephen Taylor WW2 Relic Hunter. 3 March 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018. Article has a great many illustrations and descriptions of bomb fuzes and pistols.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Miniature Bomb, Heavyweight Punch". Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Frieden, David R. Principles of Naval Weapons Systems Naval Institute Press (1985) ISBN 0-87021-537-X pp.405-427

- "ZUS 40 (Anti withdrawal device 40) Germany WW2". Inert Ordnance Collectors. 22 January 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

Sources

- Canada. Army Electronic Library. Field Artillery Volume 6. Ballistics and Ammunition. B-GL-306-006/FP-001 1992-06-01

- Ministry of Defence (Army Dept.) (1968). Explosives Terms and Definitions. A 32/ARTS/R & D/678.

External links

- A range of modern munitions fuzes, together with detailed technical specifications

- Bomb fuze data - US guide dated 1945

- Safing, Arming, Fuzing, and Firing (SAFF) info from Globalsecurity.org

- Tutorial regarding fuzes for air-dropped bombs

- Internal view of 1940s aerial bomb fuze, featuring 2 strikers held back by single screw-thread and 2 creep springs

- 90th Infantry Division Preservation Group - page on 81mm Mortar Fuzes

- Farmer, William C. (1945), Ordnance Field Guide, vol. III, Harrisburg, PA: Military Service Publishing, pp. cf 7, "Introduction to Fuzes"