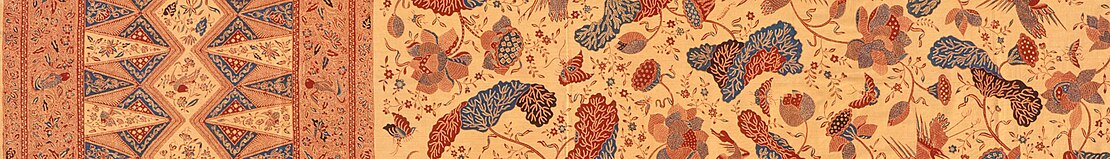

Batik from Surakarta in Central Java province in Indonesia; before 1997 Batik from Surakarta in Central Java province in Indonesia; before 1997 | |

| Type | Art fabric |

|---|---|

| Material | Cambrics, silk, cotton |

| Production process | Craft production |

| Place of origin | Indonesia |

| Indonesian Batik | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage | |

Batik craftswomen in Java drawing intricate patterns using canting and wax that are kept hot and liquid in a small heated pan, Batik craftswomen in Java drawing intricate patterns using canting and wax that are kept hot and liquid in a small heated pan,on 27 July 2011 | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Reference | 00170 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2009 (4th session) |

| List | Representative |

| Written batik (batik tulis) and stamped batik (batik cap) | |

| Education and training in Indonesian Batik | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage | |

Museum Batik Pekalongan, Central Java Museum Batik Pekalongan, Central Java | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Reference | 00318 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2009 (4th session) |

| List | Good Safeguarding Practices |

Batik plays multiple roles in the culture of Indonesia. The wax resist-dyeing technique has been used for centuries in Java, and has been adopted in varying forms in other parts of the country. Java is home to several batik museums.

On 2 October 2009, UNESCO inscribed written batik (batik tulis) and stamped batik (batik cap) as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity from Indonesia. Since then, Indonesia has celebrated a Batik Day (Hari Batik Nasional) annually on 2 October. In the same year, UNESCO recognized education and training in Indonesian Batik as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

History

Ancient to early modern periods

The art of batik is most highly developed in the island of Java, although the antiquity of the technique is difficult to determine since batik pieces rarely survive long in the region's tropical climate. The Dutch historians Rouffaer & Juynboll argue that the technique might have been introduced during the 6th or 7th century from India or Sri Lanka. The similarities between some traditional batik patterns with clothing details in ancient Hindu-Buddhist statuaries, for example East Javanese Prajnaparamita, has made some authors attribute batik's creation to Java's Hindu-Buddhist period (8th-16th century AD). Some scholars however object that mere similarity of pattern is not conclusive of batik, as it could be made by a number of non-related techniques. Further, as the word "batik" is not attested in any pre-Islamic sources, there is also the view that batik only flourished at the end of Java's Hindu-Buddhist period, from the 16th century onward following the demise of Majapahit kingdom.

The oldest physical Javanese batik piece to have survived so far is a 700 year old blue-white valance in the private collection of Thomas Murray. The batik's quality and early Majapahit period carbon-dating suggest that sophisticated batik techniques already existed at the time, but competed with the more established ikat textiles. Batik craft further flourished in the Islamic courts of Java in the following centuries.

- Some ancient Indonesian statues that use batik motifs

-

Kawung batik motif on Mahakala statue, from temple at Singhasari, East Java, 1275–1300

Kawung batik motif on Mahakala statue, from temple at Singhasari, East Java, 1275–1300

-

Kawung batik motif on Nandishvara statue (foreground, 13th century)

Kawung batik motif on Nandishvara statue (foreground, 13th century)

-

Batik motif on Durga Mahishasuramardini statue, Singhasari, 1275–1300

Batik motif on Durga Mahishasuramardini statue, Singhasari, 1275–1300

Modern period

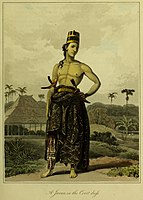

Batik technique became more widely known (particularly by Europeans) when Javanese batik was described for the first time in Thomas Stamford Raffles's 1817 The History of Java, which also marked the beginning of collecting and scholarly interest in batik traditions. In 1873 the Dutch merchant Van Rijckevorsel gave the pieces he collected during a trip to Indonesia to the ethnographic museum in Rotterdam. Examples were displayed at the Exposition Universelle at Paris in 1900. Today the Tropenmuseum houses the biggest collection of Indonesian batik in the Netherlands.

In the 19th to early 20th century, Dutch Indo–Europeans and Chinese settlers were actively involved in the production and development of Javanese batik, particularly pesisir "coastal" batik in the northern coast of Java, especially developed in Pekalongan City, Batik Elhasiq. They introduced innovations such as cap (copper block stamps) to mass-produce batiks, synthetic dyes which allow brighter colors, and new patterns which blended a number of cultural influences. Several prominent batik ateliers appeared, such as Oey Soe Tjoen and Eliza van Zuylen, and their products catered to a wide audience in the Malay archipelago (encompassing modern Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore). Batik skirts and sarongs for example were widely worn by indigenous, Chinese, and European women of the region, paired with the ubiquitous kebaya shirt. Batik was also used for more specialized application, for example peranakan altar cloth called 桌帷 tok wi. It is in this time period that the influence of Javanese batik spread. In Subsaharan Africa, Javanese batik was introduced in the 19th century by Dutch and English merchants. It was subsequently modified by local artisans with larger motifs, thicker lines, and more colours into what is now known as African wax prints. Modern West African versions also use cassava starch, rice paste, or mud as a resist. In the 1920s, Javanese batik makers migrating to the eastern coast of Malay Peninsula introduced batik production using stamp blocks.

Many traditional ateliers in Java collapsed immediately following the Second World War and Indonesian wars of independence, but many workshops and artisans are still active today creating a wide range of products. They still continue to influence a number of textile traditions and artists. In the 1970s for example, batik was introduced to Australia, where aboriginal artists at Ernabella have developed it as their own craft. The works of the English artist Thetis Blacker were influenced by Indonesian batik; she had worked in Yogyakarta's Batik Research Institute and had travelled in Bali.

Types

As each region of Indonesia has its own traditional pattern, batiks are commonly distinguished by the region they originated in, such as batik Solo, batik Yogyakarta, batik Pekalongan Pekalongan, and batik Madura. Batiks from Java can be distinguished by their general pattern and colours into batik pedalaman (inland batik) or batik pesisiran (coastal batik). Batiks which do not fall neatly into one of these two categories are classified by their region. A clustering of batik designs from all parts of Indonesia by degree of similarity indicates a history of cultural assimilation.

Javanese batik

Pekalongan batik

In this city, an original handmade batic is the most know and famous batic as authentic, and its pattern has characteristic about animal or nature.

Inland batik

Inland batik, batik pedalaman or batik kraton (Javanese court batik) is the oldest batik tradition in Java. Inland batik has an earth colour such as black, indigo, brown, and sogan (a yellow from the tree Peltophorum pterocarpum), sometimes against a white background, with symbolic patterns that are mostly free from outside influence. Certain patterns are worn and preserved by the royal courts, while others are worn on specific occasions. At a Javanese wedding for example, the bride wears specific patterns at each stage of the ceremony. Noted inland batiks are produced in Solo and Jogjakarta, cities traditionally regarded as the centre of Javanese culture. Batik Solo typically has a sogan background and is used by the Susuhunan and Mangkunegaran Courts. Batik Jogja typically has a white background and is used by the Yogyakarta Sultanate and the Pakualaman Court.

Coastal batik

Coastal batik or batik pesisiran is produced in several areas of northern Java and Madura. In contrast to inland batik, coastal batiks have vibrant colours and patterns inspired by a wide range of cultures as a consequence of maritime trading. Recurring motifs include European flower bouquets, Chinese phoenix, and Persian peacocks. Noted coastal batiks are produced in Pekalongan, Cirebon, Lasem, Tuban, and Madura; out of these, Pekalongan has the most active batik industry.

Jawa Hokokai, named after Hōkōkai (ジャワ奉公会), a Japanese-led organization of locals for war-cooperation, is not attributed to a particular region. During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies in the early 1940s, the batik industry greatly declined due to material shortages. The workshops funded by the Japanese however were able to produce extremely fine Jawa Hokokai batiks. Common Hokokai motifs include Japanese cherry blossoms (sakura), butterflies, and chrysanthemums.

Another coastal batik called tiga negeri ( three lands) is attributed to three regions: Lasem, Pekalongan, and Solo, where the batik would be dipped in red, blue, and sogan dyes respectively. As of 1980, tiga negeri was only produced in one city.

Sundanese batik

So-called Sundanese or Parahyangan Batik is made in the Parahyangan region of West Java and Banten. Baduy batik only employs indigo in shades from bluish black to deep blue. It is traditionally worn by Outer Baduy people of Lebak Regency, Banten as iket, a type of Sundanese head-dress similar to the Balinese udeng. Bantenese batik employs bright pastel colours and represents a revival of a lost art from the Sultanate of Banten, rediscovered through archaeological work during 2002–2004. Twelve motifs from locations such as Surosowan have been identified.

Malay batik

Trade between the Melayu Kingdom in Jambi and Javanese coastal cities has thrived since the 13th century. Therefore, coastal batik from northern Java probably influenced Jambi. In 1875, Haji Mahibat from Central Java revived the declining batik industry in Jambi. The village of Mudung Laut in Pelayangan district produces batik Jambi. Batik Jambi and Javanese batik influenced the Malaysian batik.

The batik from Bengkulu on the west coast of Sumatra is called batik besurek, meaning "batik with letters, calligraphic batik" as it draws inspiration from Arabic calligraphy.

Minangkabau batik

The Minangkabau people of West Sumatra produce batik called batiak tanah liek (clay batik). This uses clay as dye for the fabric. The fabric is immersed in clay for more than one day and then inscribed with motifs of animals and plants.

Balinese batik

Batik making in the island of Bali is a relatively new but fast-growing industry. Many patterns are inspired by local designs. Motifs include objects from nature such as frangipani and hibiscus flowers, birds, and fishes; daily activities such as Balinese dance and ngaben processions; and mythological creatures such as barong, kala and winged lions. Modern batik artists express themselves freely in a wide range of subjects.

Contemporary batik is not limited to traditional or ritual use in Bali. Some designers promote Balinese batik as an elegant fabric. High class batik, like handmade batik tulis, can denote social status.

Culture

Batik is widespread in Indonesia. Written batik has a cultural dimension that contains prayer, hope, and lessons. Batik motifs in ancient Javanese society had a symbolic meaning, indicating a person's level in society.

Infants are carried in batik slings decorated with symbols designed to bring the child luck; other designs are reserved for brides and bridegrooms, and their families. Batik garments play a central role in Javanese rituals, such as the ceremonial casting of royal batik into a volcano. In the Javanese naloni mitoni ceremony, the mother-to-be is wrapped in seven layers of batik, wishing her good things. Batik is prominent in the tedak siten ceremony when a child touches the earth for the first time. Some patterns are reserved for traditional and ceremonial contexts.

- Batik in 19th century Java, from The History of Java by Thomas Stamford Raffles (1817)

-

A Javanese man in court dress

A Javanese man in court dress

-

A Javanese chief, in his ordinary dress

A Javanese chief, in his ordinary dress

-

A Javanese man in war dress

A Javanese man in war dress

-

A Javanese man of the lower class

A Javanese man of the lower class

-

A Javanese ronggeng dancer

A Javanese ronggeng dancer

Traditional costume in the Javanese royal palace

Batik is the traditional costume of the royal and aristocratic families in Java. The use of batik remains a mandatory traditional dress in the Javanese palaces. Initially, the tradition of making batik was only practiced in the palace, and was reserved for the clothes of the king, his family, and their followers, thus becoming a symbol of Javanese feudalism. Because many of the king's followers lived outside the palace, batik came outside the palace. The motifs of the Parang Rusak, semen gedhe, kawung, and udan riris are used by the aristocrats and courtiers in garebeg ceremonies, pasowanan, and welcoming honoured guests. During the colonial era, Javanese courts required certain patterns to be worn according to a person's rank and class within society. Sultan Hamengkubuwono VII, who ruled the Yogyakarta Sultanate from 1921 to 1939, reserved patterns such as the Parang Rusak and Semen Agung for the Yogyakartan royal family, forbidding commoners from wearing them.

- Batik in the royal palace

-

Sultan Hamengkubuwono VI, King of Yogyakarta Sultanate (1855–1877), dressed in royal majesty attire (batik)

Sultan Hamengkubuwono VI, King of Yogyakarta Sultanate (1855–1877), dressed in royal majesty attire (batik)

-

Pakubuwono X, the King of Surakarta Sunanate in kain batik, c. 1910

Pakubuwono X, the King of Surakarta Sunanate in kain batik, c. 1910

-

The Ratoe Kedaton wearing batik, the head wife of Hamengkubuwono V of Kraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat, c. 1865

The Ratoe Kedaton wearing batik, the head wife of Hamengkubuwono V of Kraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat, c. 1865

-

Princes and princess wearing batik of Kraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat, c. 1870

Princes and princess wearing batik of Kraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat, c. 1870

Traditional dance costumes

Batik is used for traditional Javanese dance performances. It is worn for instance for the Ramayana Ballet at the Prambanan temple.

- Dancers' batik dress

-

Bedhaya dance performance at Mangkunegaran royal palace at Solo, Java, in January 1921

Bedhaya dance performance at Mangkunegaran royal palace at Solo, Java, in January 1921

-

Topeng dance performance from Cirebon, West Java, Indonesia

Topeng dance performance from Cirebon, West Java, Indonesia

-

King Duryodana in Wayang wong performance in Taman Budaya Rahmat Saleh, Semarang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia

King Duryodana in Wayang wong performance in Taman Budaya Rahmat Saleh, Semarang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia

-

Golek Ayun-Ayun Dance performance accompanied by Gamelan Ensemble at Bangsal Sri Manganti Keraton Yogyakarta

Birth ceremonies

In Javanese tradition, when a mother-to-be reaches the seventh month of pregnancy, a mitoni ceremony is held, where she has to put on the seven kebayas and seven batik cloths. Each batik cloth has a high philosophical value which is also a strand and hope for the Almighty so that the baby who is born has a good personality.

Wedding ceremonies

Every motif in classical Javanese batik has its own meaning and philosophy, including for wedding ceremonies. In the Javanese wedding ceremony, certain designs are reserved for brides and bridegrooms, as well as their families. The truntum flower motif in the shape of the su) is used for midodareni ceremony (the procession of the night before the wedding ceremony, symbolizing the last night before the child separates from parents). This motif is also used during the panggih ceremony (the procession when the bride and groom meet after being secluded) by the parents of the bride and groom. The truntum motif symbolises love that never ends.

- Wedding batik

-

Javanese Royal wedding in Mangkunegaran royal palace, January 1921

Javanese Royal wedding in Mangkunegaran royal palace, January 1921

-

Kacar-kucur ceremony, groom pouring rice and coins into bride's scarf, c. 1960

Kacar-kucur ceremony, groom pouring rice and coins into bride's scarf, c. 1960

-

Panggih ceremony, meeting between bride and groom on their wedding day

Panggih ceremony, meeting between bride and groom on their wedding day

-

Batik in a traditional Javanese wedding ceremony.

Batik in a traditional Javanese wedding ceremony.

Formal and informal daily dress

Contemporary practice often allows people to pick any pattern according to one's taste and preference from casual to formal situations, and batik makers modify, combine, or invent new iterations of well-known patterns. Batik has become a daily dress for work, school, and formal and informal events in Indonesia. Many young designers have started their fashion design work by taking batik as their inspiration. Their creativity has given birth to modern batik clothing.

- Daily dress

-

Nelson Mandela wearing batik

Nelson Mandela wearing batik

-

A Javanese man wearing typical contemporary batik shirt

A Javanese man wearing typical contemporary batik shirt

-

An elderly Sundanese woman wearing batik sarong and headdress

An elderly Sundanese woman wearing batik sarong and headdress

Popularity

Further information: Solo Batik Carnival

The batik industry of Java flourished from the late 1800s to the early 1900s, but declined during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies. With increasing preference of western clothing, the batik industry further declined following the Indonesian independence. Batik has somewhat revived at the turn of the 21st century, through the efforts of Indonesian fashion designers to innovate batik by incorporating new colours, fabrics, and patterns. Batik has become a fashion item for many Indonesians, and may be seen on shirts, dresses, or scarves for casual wear; it is a preferred replacement for jacket-and-tie at certain receptions. Traditional batik sarongs are still used in many occasions.

After the UNESCO recognition for Indonesian batik on 2 October 2009, the Indonesian administration asked Indonesians to wear batik on Fridays, and wearing batik every Friday has been encouraged in government offices and private companies ever since. 2 October is celebrated as National Batik Day in Indonesia. Batik had helped improve the small business local economy, batik sales in Indonesia had reached Rp 3.9 trillion (US$436.8 million) in 2010, an increase from Rp 2.5 trillion in 2006. The value of batik exports, meanwhile, increased from $14.3 million in 2006 to $22.3 million in 2010.

Batik is popular in the neighbouring countries of Singapore and Malaysia. It is produced in Malaysia with similar, but not identical, methods to those used in Indonesia. Batik is featured in the national airline uniforms of the three countries, represented by batik prints worn by flight attendants of Singapore Airlines, Garuda Indonesia and Malaysian Airlines. The female uniform of Garuda Indonesia flight attendants is a modern interpretation of the Kartini style kebaya with parang gondosuli motifs.

Parts of the cloth

In Indonesia, batik is traditionally sold in 2.25-metre lengths used for kain panjang or sarong. It is worn by wrapping it around the hip, or made into a hat known as blangkon. The cloth can be filled continuously with a single pattern or divided into several sections. Certain patterns are only used in certain sections of the cloth. For example, a row of isosceles triangles, forming the pasung motif, as well as diagonal floral motifs called dhlorong, are commonly used for the head. However, pasung and dhlorong are occasionally found in the body. Other motifs such as buketan (flower bouquet) and birds are commonly used in either the head or the body.

- The head is a rectangular section of the cloth which is worn at the front of the sarong. The head section can be at the middle of the cloth, or placed at one or both ends. The papan inside of the head can be used to determine whether the cloth is kain panjang or sarong.

- The body is the main part of the cloth, and is filled with a wide variety of patterns. The body can be divided into two alternating patterns and colours called pagi-sore ('morning-evening'). Brighter patterns are shown during the day, while darker pattern are shown in the evening. The alternating colours give the impression of two batik sets.

- Margins are often plain, but floral and lace-like patterns, as well as wavy lines described as a dragon, are common in the area beside seret.

Patterns and motifs

Further information: Indonesian batik patternsThe patterns of batik textile are particular to the time, place, and culture of their producers. Indonesian batik patterns drew from a wide range of cultural influence (see table below) and are often symbolically rich. Some batik patterns are attributed with loaded meanings and deep philosophies, with their use reserved for special occasions or groups of peoples (e.g. nobles, royalties). Some scholars however note that existing literature on the subject of Indonesian textiles are prone to over-romanticize and exoticize purported 'meanings' behind mundane patterns. It must be noted that some batik patterns were created simply to satisfy market demand and fashion trends.

| Cultural influences | Batik patterns | Geographic locations | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Indonesian | Kawung, ceplok, gringsing, parang, lereng, truntum, sekar jagad (combination of motifs) and other decorative motifs such as of Javanese, Dayak, Batak, Papuan, Riau Malay. | Respective areas with their own patterns |

|

| Hindu–Buddhist | Garuda, banji, cuwiri, kalpataru, meru or gunungan, semen rama, pringgondani, sidha asih, sidha mukti, sidha luhur | Java |

|

| Islamic | Besurek or Arabic calligraphy, buraq | Bengkulu, Cirebon, Jambi |

|

| Chinese | Burung hong (Chinese phoenix), liong (Chinese dragon), qilin, wadasan, megamendung (Chinese-style cloud), lok tjan | Lasem, Cirebon, Pekalongan, Tasikmalaya, Ciamis |

|

| Indian | Jlamprang, peacock, elephant | Cirebon, Garut, Pekalongan, Madura |

|

| European (colonial era) | Buketan (floral bouquet), European fairytale, colonial images such as house, horses, carriage, bicycle and European-dressed people | Java |

|

| Japanese | sakura, hokokai, chrysanthemum, butterfly | Java |

|

Batik museums

Java has several museums with collections of old batiks and equipment for batik production, including:

Museum Batik Keraton Yogyakarta is inside the Palace of Yogyakarta Sultanate, Yogyakarta. The museum which was inaugurated by Sultan Hamengku Buwono X on 31 October 2005 has thousands of batik collections. The batik collection here includes kawung, semen, gringsing, nitik, cuwiri, parang, barong, grompol, and other motifs. These items come from different eras, from the era of Sultan Hamengkubuwono VIII to Hamengkubuwono X. Visitors can see equipment for making batik, raw materials for dyes, irons, sculptures, paintings, and batik masks. The museum does not allow cameras.

Museum Batik Yogyakarta is in Bausasran, Yogyakarta. It was inaugurated in 1977. In 2000, it received an award from MURI for the work 'The Biggest Embroidery', a batik measuring 90 x 400 cm2. The museum holds more than 1,200 batik items consisting of 500 pieces of written batik, 560 stamped batik, 124 canting (batik tools), and 35 pans and colouring materials, including wax. Its collection consists of fabrics from the 18th to early 19th centuries in the form of long cloths and sarongs. Other collections include batik by Van Zuylen and Oey Soe Tjoen. The museum provides batik training for visitors who want to learn to make batik.

Museum Batik Pekalongan is in Pekalongan, Central Java. This museum has 1,149 batik items, including batik cloth, centuries old batik wayang beber, and traditional weaving tools. It maintains a large collection of old to modern batik, with those from coastal areas, inland areas, other areas of Java, and regions such as Sumatra, Kalimantan, Papua, and batik-type fabrics from abroad. The museum provides batik training.

Museum Batik Danar Hadi is on Jalan Slamet Riyadi, Solo City (Surakarta), Central Java. The museum, which was founded in 1967, holds items from regions such as the original Javanese Batik Keraton, Javanese Hokokai batik, coastal batik (Kudus, Lasem, and Pekalongan), and Sumatran batik. It has a collection of batik cloths reaching 1000 pieces. Visitors can see the process of making batik and can take part in batik making workshops.

The Textile Museum is on Jalan KS Tubun No. 4, Petamburan, West Jakarta. On June 28, 1976, this building was inaugurated as a textile museum by Mrs. Tien Soeharto (First Lady at that time) witnessed by Mr. Ali Sadikin as the governor of DKI Jakarta. The initial collections at the Textile Museum were obtained from donations from Wastraprema (about 500 items), then increased through purchases by the Museum and History Service, as well as donations. By 2021, the collection was recorded at 1,914 items. The batik gallery showcases ancient batik and contemporary batik developments. The batik gallery is the embryo of the National Batik Museum managed by the Indonesian Batik Foundation and the Jakarta Textile Museum.

Cultural recognition

UNESCO designations

In October 2009, UNESCO designated Indonesian batik as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. As part of the acknowledgment, UNESCO insisted that Indonesia preserve its heritage. The day, 2 October 2009 has been stated by Indonesian government as National Batik Day, as also at the time the map of Indonesian batik diversity by Hokky Situngkir was opened for public for the first time by the Indonesian Ministry of Research and Technology.

Study of the geometry of Indonesian batik has shown the applicability of fractal geometry in traditional designs.

Postage stamps

Indonesia has repeatedly featured Batik in its postage stamps.

- Batik in postage stamps

-

1971, 20 rupiah

1971, 20 rupiah

-

1973, 60 rupiah

1973, 60 rupiah

-

1973, 100 rupiah

1973, 100 rupiah

-

1999, 500 rupiah Cirebon

1999, 500 rupiah Cirebon

-

1999, 500 rupiah, Madura

1999, 500 rupiah, Madura

-

1999, 500 rupiah, Jambi

1999, 500 rupiah, Jambi

-

1999, 500 rupiah, Yogyakarta

1999, 500 rupiah, Yogyakarta

-

2020, 5000 rupiah

2020, 5000 rupiah

See also

- Balinese textiles

- Batik industry in Sri Lanka

- Folk costume

- Ikat

- Malaysian batik

- National costume of Indonesia

- Indonesian art

- Culture of Indonesia

- Tsutsugaki, Japanese resist-dyeing using starch, not wax

Notes

- Education and training in Indonesian Batik intangible cultural heritage for elementary, junior, senior, vocational school and polytechnic students, in collaboration with the Batik Museum in Pekalongan

References

- "Indonesia Batik". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Shamasundari, Rebecca (7 February 2021). "Celebrating Indonesia's cultural heritage, batik". The ASEAN Post. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "Education and training in Indonesian Batik intangible cultural heritage for elementary, junior, senior, vocational school and polytechnic students, in collaboration with the Batik Museum in Pekalongan". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Nava 1991.

- Rouffaer & Juynboll 1899.

- "Prajnaparamita and other Buddhist deities". Volkenkunde Rijksmuseum. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- Pullen 2021, pp. 58.

- Langewis & Wagner 1964, pp. 16.

- Maxwell 2003, pp. 325.

- Sardjono & Buckley 2022.

- Lee et al 2015.

- Shen & Wong 2023.

- "Batik in Africa". The Batik Guild. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Shaharuddin et al 2021.

- Harmsen 2018.

- Stevy, Maradona (11 February 2011). "Antropolog Australia Beri Ceramah Soal Batik". Republika.

- Buckman, David (31 January 2007). "Thetis Blacker: Visionary batik painter". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Sari, Yuslena; Alkaff, Muhammad; Pramunendar, Ricardus Anggi (26 June 2018). "Classification of coastal and Inland Batik using GLCM and Canberra Distance". AIP Conference Proceedings. 1977 (1): 020045. Bibcode:2018AIPC.1977b0045S. doi:10.1063/1.5042901. ISSN 0094-243X.

- Situngkir, Hokky (2 February 2009). "Phylomemetic Tree of Indonesian Traditional Batik". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ "Reichle, Natasha (2012). "Batik: Spectacular Textiles of Java" The Newsletter. International Institute for Asian Studies" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- Pulandari, Nunuk (13 April 2011). "Arti dan Cerita di balik Motif Batik Klasik Jawa". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2014. (in Indonesian)

- ^ "Batik Days". The Jakarta Post. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- Nur Aziza, Aisya (1 October 2022). "Jangan Sampai Keliru, Inilah Perbedaan Batik Pedalaman dan Batik Pesisir" [Don't Get It Wrong, This is the Difference Between Inland Batik and Coastal Batik] (in Indonesian). Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "UNESCO Culture Sector – Intangible Heritage – 2003 Convention". UNESCO – Intangible Heritage Section. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Sumarsono et al 2013.

- Adriati, Ira; Zainsjah, Almira Belinda (28 September 2020). "Analysis of the Japanese Culture Influence in the Visualization of Djawa Hokokai Batik" (PDF). International Conference on Aesthetics and the Sciences of Art. pp. 91–92. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- Pradito, Didit; Jusuf, Herman; Atik, Saftyaningsih Ken (2010). The Dancing Peacock: Colours and Motifs of Priangan Batik. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 978-979-22-5825-7. Page 5

- "Batik Baduy diminati pengunjung Jakarta Fair" (in Indonesian). Antara News.com. 15 June 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- Uke Kurniawan, Memopulerkan Batik Banten Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, haki.lipi.go.id, accessed 4 October 2009

- National Geographic Traveller Indonesia, Vol 1, No 6, 2009, Jakarta, Indonesia, page 54

- "Besurek Batik: Calligraphic Fabric from Bengkulu". jalurrempah.kemdikbud.go.id. 26 January 2022. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- "Pesona Batik Jambi" (in Indonesian). Padang Ekspres. 16 November 2008. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- "Batik Asli Indonesia". Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Bali Batik, Bali Sarong, Kimono - Bali Textiles, Bali Garment, Clothing". balibatiku.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Rawal, Sucheta (4 October 2016). "The Many Faces of Sustainable Tourism – My Week in Bali". Huffingtonpost. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- "Batik : Sebuah Konsepsi Estetika Seni Jawa yang Adiluhung, Indah bagai di Awang". kebudayaan.kemdikbud.go.id. 16 April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- Maziyah, Siti; Mahirta, Mahirta; Atmosudiro, Sumijati (2016). "Makna Simbolis Batik Pada Masyarakat Jawa Kuna". Paramita: Historical Studies Journal. 26 (1): 23–32. doi:10.15294/paramita.v26i1.5143. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Batik patterns hold deep significance". thejakartapost.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- "Sejarah Batik Indonesia". Government of West Java. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- "Batik: The Forbidden Designs of Java – Australian Museum". australia.nmuseum. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Smend et al 2013.

- "Cerita Filosofi 7 Lembar Batik di Upacara Mitoni". www.beritasatu.com. 2 October 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "7 Motif Batik Untuk Pernikahan". infobatik.com. 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Nomination for inscription on the Representative List in 2009 (Reference No. 00170)". UNESCO. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- "Administration calls for all-in batik day this Friday". thejakartapost.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- "Let's use batik as diplomatic tool: SBY". thejakartapost.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011.

- Indriasari, Lusiana; Yulia Sapthiani (26 September 2010). "Terbang Bersama Kebaya" (in Indonesian). Female Kompas.com. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- Pujobroto, P.T. (2 June 2010). "Garuda Indonesia Launches New Uniform". Garuda Indonesia.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- Barnes et al 2020, pp. 4–5.

- Sumarsono et al 2016.

- "Sejarah Museum Keraton Yogyakarta dan Bagian-Bagiannya". sejarahlengkap.com. 4 February 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Museum Batik Yogyakarta". Dinas Pariwisata Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "Profile of Museum Batik Yogyakarta". Museum Batik Yogyakarta. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "Sejarah Museum Batik Pekalongan". Museum Batik Pekalongan. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Museum Batik Danar Hadi". Dinas Pariwisata Kota Surakarta. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "Museum Tekstil Jakarta". Museum Jakarta. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Ingat, Besok Hari Batik Nasional, Wajib Pakai Batik". setkab.go.id. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- "Mengupas Center for Complexity Surya University". Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- Situngkir, Hokky; Dahlan, Rolan; Surya, Yohanes. Fisika batik : implementasi kreatif melalui sifat fraktal pada batik secara komputasional. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama (2009). ISBN 978-979224484-7 & ISBN 979224484-0

- "Batik designs 1999". Stampworld. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

Sources

- Barnes, Ruth; Duggan, Geneviève; Gavin, Traude; Hamilton, Roy; Nabholz-Kartaschoff, Marie-Louise; Babcock, Tim; Niessen, Sandra (16 September 2020). "Review of Peter ten Hoopen's Ikat Textiles of the Indonesian Archipelago". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3695773.

- Harmsen, Olga (2018). Batik – How Emancipation of Dutch Housewives in the Dutch East Indies and "Back Home" Influenced Art Nouveau Design in Europe (PDF). cdf III Art Nouveau International Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Langewis, Laurens; Wagner, Frits A. (1964). Decorative Art in Indonesian Textiles. Amsterdam: CPJ van der Peet.

- Lee, Peter; Kerlogue, Fiona; Chiesa, Benjamin; Joseph, Maria Khoo (2015). Auspicious Designs: Batik for Peranakan Altars. Singapore: Asian Civilizations Museum.

- Maxwell, Robyn (2003). Textiles of Southeast Asia: Tradition, Trade and Transformation. Singapore: Periplus.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Nava, Nadia (1991). Il batik: come tingere e decorare i tessuti diegnando con la cera. Ulisse. ISBN 88-414-1016-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Pullen, Lesley (2021). Patterned Splendour: Textiles Presented on Javanese Metal and Stone Sculptures, Eighth to Fifteenth Century. Singapore: ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Rouffaer, G. G.; Juynboll, H. H. (1899). De batik-kunst in Nederlandsch-Indië en haar geschiedenis. Haarlem: H Kleinmann & Co.

- Sardjono, Sandra; Buckley, Christopher (2022). "A 700-years old blue-and-white batik from Indonesia". Fiber, Loom and Technique Society. 1: 64–78.

- Shaharuddin, Sharifah Imihezri Syed; Shamsuddin, Maryam Samirah; Drahman, Mohd Hafiz; Hasan, Zaimah; Asri, Nurul Anissa Mohd; Nordin, Ahmad Amri; Shaffiar, Norhashimah Mohd (2021). "A Review on the Malaysian and Indonesian Batik Production, Challenges, and Innovations in the 21st Century". SAGE Open. 11 (3). doi:10.1177/21582440211040128.

- Shen, Yuexiu; Wong, Mei Sheong (2023). "Qilin, Rabbit and Pencils: Batik Tokwi from Northcoast Java". In James Bennett; Russel Kelty (eds.). Interwoven Journeys: the Michael Abbott Collections of Asian Art. Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA).

- Smend, Rudolf G.; Majlis, Brigitte Khan; Veldhuisen, Harmen C. (2013). Batik: From the Courts of Java and Sumatra. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing. Frontispiece. ISBN 978-146290695-6.

- Sumarsono, Hartono; Ishwara, Helen; Yahya, L.R. Supriyapto; Moeis, Xeni (2013). Benang Raja: Menyimpul Keelokan Batik Pesisir. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-9106-01-8.

- Sumarsono, Hartono; Ishwara, Helen; Yahya, L.R. Supriyapto; Moeis, Xeni (2016). Batik Garutan: Koleksi Hartono Sumarsono. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 978-602-6208-09-5.

Further reading

- Doellah, H. Santosa (2003). Batik: The Impact of Time and Environment. Solo: Danar Hadi. ISBN 979-97173-1-0.

- Elliott, Inger McCabe (1984). Batik: fabled cloth of Java. New York: Clarkson N. Potter Inc. ISBN 0-517-55155-1.

- Fraser-Lu, Sylvia (1986). Indonesian batik : processes, patterns, and places. Singapore: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-582661-2.

- Gillow, John; Dawson, Barry (1995). Traditional Indonesian Textiles. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27820-2.

External links

| Indonesia articles | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

| ||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||

| Politics | |||||||||

| Economy | |||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||