Chemical element with atomic number 4 (Be)

Beryllium is a chemical element; it has symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, hard, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with other elements to form minerals. Gemstones high in beryllium include beryl (aquamarine, emerald, red beryl) and chrysoberyl. It is a relatively rare element in the universe, usually occurring as a product of the spallation of larger atomic nuclei that have collided with cosmic rays. Within the cores of stars, beryllium is depleted as it is fused into heavier elements. Beryllium constitutes about 0.0004 percent by mass of Earth's crust. The world's annual beryllium production of 220 tons is usually manufactured by extraction from the mineral beryl, a difficult process because beryllium bonds strongly to oxygen.

In structural applications, the combination of high flexural rigidity, thermal stability, thermal conductivity and low density (1.85 times that of water) make beryllium a desirable aerospace material for aircraft components, missiles, spacecraft, and satellites. Because of its low density and atomic mass, beryllium is relatively transparent to X-rays and other forms of ionizing radiation; therefore, it is the most common window material for X-ray equipment and components of particle detectors. When added as an alloying element to aluminium, copper (notably the alloy beryllium copper), iron, or nickel, beryllium improves many physical properties. For example, tools and components made of beryllium copper alloys are strong and hard and do not create sparks when they strike a steel surface. In air, the surface of beryllium oxidizes readily at room temperature to form a passivation layer 1–10 nm thick that protects it from further oxidation and corrosion. The metal oxidizes in bulk (beyond the passivation layer) when heated above 500 °C (932 °F), and burns brilliantly when heated to about 2,500 °C (4,530 °F).

The commercial use of beryllium requires the use of appropriate dust control equipment and industrial controls at all times because of the toxicity of inhaled beryllium-containing dusts that can cause a chronic life-threatening allergic disease, berylliosis, in some people. Berylliosis is typically manifested by chronic pulmonary fibrosis and, in severe cases, right sided heart failure and death.

Characteristics

Physical properties

Beryllium is a steel gray and hard metal that is brittle at room temperature and has a close-packed hexagonal crystal structure. It has exceptional stiffness (Young's modulus 287 GPa) and a melting point of 1287 °C. The modulus of elasticity of beryllium is approximately 35% greater than that of steel. The combination of this modulus and a relatively low density results in an unusually fast sound conduction speed in beryllium – about 12.9 km/s at ambient conditions. Other significant properties are high specific heat (1925 J·kg·K) and thermal conductivity (216 W·m·K), which make beryllium the metal with the best heat dissipation characteristics per unit weight. In combination with the relatively low coefficient of linear thermal expansion (11.4 × 10 K), these characteristics result in a unique stability under conditions of thermal loading.

Nuclear properties

Naturally occurring beryllium, save for slight contamination by the cosmogenic radioisotopes, is isotopically pure beryllium-9, which has a nuclear spin of 3/2. Beryllium has a large scattering cross section for high-energy neutrons, about 6 barns for energies above approximately 10 keV. Therefore, it works as a neutron reflector and neutron moderator, effectively slowing the neutrons to the thermal energy range of below 0.03 eV, where the total cross section is at least an order of magnitude lower; the exact value strongly depends on the purity and size of the crystallites in the material.

The single primordial beryllium isotope Be also undergoes a (n,2n) neutron reaction with neutron energies over about 1.9 MeV, to produce Be, which almost immediately breaks into two alpha particles. Thus, for high-energy neutrons, beryllium is a neutron multiplier, releasing more neutrons than it absorbs. This nuclear reaction is:

4Be

+ n → 2

2He

+ 2 n

Neutrons are liberated when beryllium nuclei are struck by energetic alpha particles producing the nuclear reaction

4Be

+

2He

→

6C

+ n

where

2He

is an alpha particle and

6C

is a carbon-12 nucleus.

Beryllium also releases neutrons under bombardment by gamma rays. Thus, natural beryllium bombarded either by alphas or gammas from a suitable radioisotope is a key component of most radioisotope-powered nuclear reaction neutron sources for the laboratory production of free neutrons.

Small amounts of tritium are liberated when

4Be

nuclei absorb low energy neutrons in the three-step nuclear reaction

4Be

+ n →

2He

+

2He

,

2He

→

3Li

+ β,

3Li

+ n →

2He

+

1H

2He

has a half-life of only 0.8 seconds, β is an electron, and

3Li

has a high neutron absorption cross section. Tritium is a radioisotope of concern in nuclear reactor waste streams.

Optical properties

As a metal, beryllium is transparent or translucent to most wavelengths of X-rays and gamma rays, making it useful for the output windows of X-ray tubes and other such apparatus.

Isotopes and nucleosynthesis

Main article: Isotopes of berylliumBoth stable and unstable isotopes of beryllium are created in stars, but the radioisotopes do not last long. It is believed that most of the stable beryllium in the universe was originally created in the interstellar medium when cosmic rays induced fission in heavier elements found in interstellar gas and dust. Primordial beryllium contains only one stable isotope, Be, and therefore beryllium is, uniquely among all stable elements with an even atomic number, a monoisotopic and mononuclidic element.

Radioactive cosmogenic Be is produced in the atmosphere of the Earth by the cosmic ray spallation of oxygen. Be accumulates at the soil surface, where its relatively long half-life (1.36 million years) permits a long residence time before decaying to boron-10. Thus, Be and its daughter products are used to examine natural soil erosion, soil formation and the development of lateritic soils, and as a proxy for measurement of the variations in solar activity and the age of ice cores. The production of Be is inversely proportional to solar activity, because increased solar wind during periods of high solar activity decreases the flux of galactic cosmic rays that reach the Earth. Nuclear explosions also form Be by the reaction of fast neutrons with C in the carbon dioxide in air. This is one of the indicators of past activity at nuclear weapon test sites. The isotope Be (half-life 53 days) is also cosmogenic, and shows an atmospheric abundance linked to sunspots, much like Be.

Be has a very short half-life of about 8×10 s that contributes to its significant cosmological role, as elements heavier than beryllium could not have been produced by nuclear fusion in the Big Bang. This is due to the lack of sufficient time during the Big Bang's nucleosynthesis phase to produce carbon by the fusion of He nuclei and the very low concentrations of available beryllium-8. British astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle first showed that the energy levels of Be and C allow carbon production by the so-called triple-alpha process in helium-fueled stars where more nucleosynthesis time is available. This process allows carbon to be produced in stars, but not in the Big Bang. Star-created carbon (the basis of carbon-based life) is thus a component in the elements in the gas and dust ejected by AGB stars and supernovae (see also Big Bang nucleosynthesis), as well as the creation of all other elements with atomic numbers larger than that of carbon.

The 2s electrons of beryllium may contribute to chemical bonding. Therefore, when Be decays by L-electron capture, it does so by taking electrons from its atomic orbitals that may be participating in bonding. This makes its decay rate dependent to a measurable degree upon its chemical surroundings – a rare occurrence in nuclear decay.

The shortest-lived known isotope of beryllium is Be, which decays through neutron emission with a half-life of 6.5×10 s. The exotic isotopes Be and Be are known to exhibit a nuclear halo. This phenomenon can be understood as the nuclei of Be and Be have, respectively, 1 and 4 neutrons orbiting substantially outside the classical Fermi 'waterdrop' model of the nucleus.

Occurrence

The Sun has a concentration of 0.1 parts per billion (ppb) of beryllium. Beryllium has a concentration of 2 to 6 parts per million (ppm) in the Earth's crust and is the 47th most abundant element. It is most concentrated in the soils at 6 ppm. Trace amounts of Be are found in the Earth's atmosphere. The concentration of beryllium in sea water is 0.2–0.6 parts per trillion. In stream water, however, beryllium is more abundant with a concentration of 0.1 ppb.

Beryllium is found in over 100 minerals, but most are uncommon to rare. The more common beryllium containing minerals include: bertrandite (Be4Si2O7(OH)2), beryl (Al2Be3Si6O18), chrysoberyl (Al2BeO4) and phenakite (Be2SiO4). Precious forms of beryl are aquamarine, red beryl and emerald. The green color in gem-quality forms of beryl comes from varying amounts of chromium (about 2% for emerald).

The two main ores of beryllium, beryl and bertrandite, are found in Argentina, Brazil, India, Madagascar, Russia and the United States. Total world reserves of beryllium ore are greater than 400,000 tonnes.

Production

The extraction of beryllium from its compounds is a difficult process due to its high affinity for oxygen at elevated temperatures, and its ability to reduce water when its oxide film is removed. Currently the United States, China and Kazakhstan are the only three countries involved in the industrial-scale extraction of beryllium. Kazakhstan produces beryllium from a concentrate stockpiled before the breakup of the Soviet Union around 1991. This resource had become nearly depleted by mid-2010s.

Production of beryllium in Russia was halted in 1997, and is planned to be resumed in the 2020s.

Beryllium is most commonly extracted from the mineral beryl, which is either sintered using an extraction agent or melted into a soluble mixture. The sintering process involves mixing beryl with sodium fluorosilicate and soda at 770 °C (1,420 °F) to form sodium fluoroberyllate, aluminium oxide and silicon dioxide. Beryllium hydroxide is precipitated from a solution of sodium fluoroberyllate and sodium hydroxide in water. The extraction of beryllium using the melt method involves grinding beryl into a powder and heating it to 1,650 °C (3,000 °F). The melt is quickly cooled with water and then reheated 250 to 300 °C (482 to 572 °F) in concentrated sulfuric acid, mostly yielding beryllium sulfate and aluminium sulfate. Aqueous ammonia is then used to remove the aluminium and sulfur, leaving beryllium hydroxide.

Beryllium hydroxide created using either the sinter or melt method is then converted into beryllium fluoride or beryllium chloride. To form the fluoride, aqueous ammonium hydrogen fluoride is added to beryllium hydroxide to yield a precipitate of ammonium tetrafluoroberyllate, which is heated to 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) to form beryllium fluoride. Heating the fluoride to 900 °C (1,650 °F) with magnesium forms finely divided beryllium, and additional heating to 1,300 °C (2,370 °F) creates the compact metal. Heating beryllium hydroxide forms beryllium oxide, which becomes beryllium chloride when combined with carbon and chlorine. Electrolysis of molten beryllium chloride is then used to obtain the metal.

Chemical properties

See also: Category:Beryllium compoundsBeryllium has a high electronegativity compared to other group 2 elements; thus C-Be bonds are less highly polarized than other C-M bonds, although the attached carbon still bears a negative dipole moment.

A beryllium atom has the electronic configuration 2s. The predominant oxidation state of beryllium is +2; the beryllium atom has lost both of its valence electrons. Lower oxidation states complexes of beryllium are exceedingly rare. For example, bis(carbene) compounds proposed to contain beryllium in the 0 and +1 oxidation state have been reported, although these claims have proved controversial. A stable complex with a Be-Be bond, which formally features beryllium in the +1 oxidation state, has been described. Beryllium's chemical behavior is largely a result of its small atomic and ionic radii. It thus has very high ionization potentials and strong polarization while bonded to other atoms, which is why all of its compounds are covalent. Its chemistry has similarities to that of aluminium, an example of a diagonal relationship.

At room temperature, the surface of beryllium forms a 1−10 nm-thick oxide passivation layer that prevents further reactions with air, except for gradual thickening of the oxide up to about 25 nm. When heated above about 500 °C, oxidation into the bulk metal progresses along grain boundaries. Once the metal is ignited in air by heating above the oxide melting point around 2500 °C, beryllium burns brilliantly, forming a mixture of beryllium oxide and beryllium nitride. Beryllium dissolves readily in non-oxidizing acids, such as HCl and diluted H2SO4, but not in nitric acid or water as this forms the oxide. This behavior is similar to that of aluminium. Beryllium also dissolves in alkali solutions.

Binary compounds of beryllium(II) are polymeric in the solid state. BeF2 has a silica-like structure with corner-shared BeF4 tetrahedra. BeCl2 and BeBr2 have chain structures with edge-shared tetrahedra. Beryllium oxide, BeO, is a white refractory solid which has a wurtzite crystal structure and a thermal conductivity as high as some metals. BeO is amphoteric. Beryllium sulfide, selenide and telluride are known, all having the zincblende structure. Beryllium nitride, Be3N2, is a high-melting-point compound which is readily hydrolyzed. Beryllium azide, BeN6 is known and beryllium phosphide, Be3P2 has a similar structure to Be3N2. A number of beryllium borides are known, such as Be5B, Be4B, Be2B, BeB2, BeB6 and BeB12. Beryllium carbide, Be2C, is a refractory brick-red compound that reacts with water to give methane. No beryllium silicide has been identified.

The halides BeX2 (X = F, Cl, Br, and I) have a linear monomeric molecular structure in the gas phase. Complexes of the halides are formed with one or more ligands donating a total of two pairs of electrons. Such compounds obey the octet rule. Other 4-coordinate complexes, such as the aqua-ion also obey the octet rule.

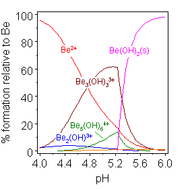

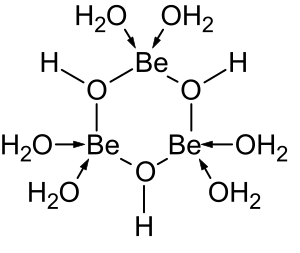

Aqueous solutions

Solutions of beryllium salts, such as beryllium sulfate and beryllium nitrate, are acidic because of hydrolysis of the ion. The concentration of the first hydrolysis product, , is less than 1% of the beryllium concentration. The most stable hydrolysis product is the trimeric ion . Beryllium hydroxide, Be(OH)2, is insoluble in water at pH 5 or more. Consequently, beryllium compounds are generally insoluble at biological pH. Because of this, inhalation of beryllium metal dust leads to the development of the fatal condition of berylliosis. Be(OH)2 dissolves in strongly alkaline solutions.

Beryllium(II) forms few complexes with monodentate ligands because the water molecules in the aquo-ion, are bound very strongly to the beryllium ion. Notable exceptions are the series of water-soluble complexes with the fluoride ion:

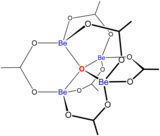

Beryllium(II) forms many complexes with bidentate ligands containing oxygen-donor atoms. The species is notable for having a 3-coordinate oxide ion at its center. Basic beryllium acetate, Be4O(OAc)6, has an oxide ion surrounded by a tetrahedron of beryllium atoms.

With organic ligands, such as the malonate ion, the acid deprotonates when forming the complex. The donor atoms are two oxygens. The formation of a complex is in competition with the metal ion-hydrolysis reaction and mixed complexes with both the anion and the hydroxide ion are also formed. For example, derivatives of the cyclic trimer are known, with a bidentate ligand replacing one or more pairs of water molecules.

Aliphatic hydroxycarboxylic acids such as glycolic acid form rather weak monodentate complexes in solution, in which the hydroxyl group remains intact. In the solid state, the hydroxyl group may deprotonate: a hexamer, , was isolated long ago. Aromatic hydroxy ligands (i.e. phenols) form relatively strong complexes. For example, log K1 and log K2 values of 12.2 and 9.3 have been reported for complexes with tiron.

Beryllium has generally a rather poor affinity for ammine ligands. Ligands such as EDTA behave as dicarboxylic acids. There are many early reports of complexes with amino acids, but unfortunately they are not reliable as the concomitant hydrolysis reactions were not understood at the time of publication. Values for log β of ca. 6 to 7 have been reported. The degree of formation is small because of competition with hydrolysis reactions.

Organic chemistry

Main article: Organoberyllium chemistryOrganoberyllium chemistry is limited to academic research due to the cost and toxicity of beryllium, beryllium derivatives and reagents required for the introduction of beryllium, such as beryllium chloride. Organometallic beryllium compounds are known to be highly reactive. Examples of known organoberyllium compounds are dineopentylberyllium, beryllocene (Cp2Be), diallylberyllium (by exchange reaction of diethyl beryllium with triallyl boron), bis(1,3-trimethylsilylallyl)beryllium, Be(mes)2, and (beryllium(I) complex) diberyllocene. Ligands can also be aryls and alkynyls.

History

The mineral beryl, which contains beryllium, has been used at least since the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt. In the first century CE, Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder mentioned in his encyclopedia Natural History that beryl and emerald ("smaragdus") were similar. The Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis, written in the third or fourth century CE, contains notes on how to prepare artificial emerald and beryl.

Early analyses of emeralds and beryls by Martin Heinrich Klaproth, Torbern Olof Bergman, Franz Karl Achard, and Johann Jakob Bindheim [de] always yielded similar elements, leading to the mistaken conclusion that both substances are aluminium silicates. Mineralogist René Just Haüy discovered that both crystals are geometrically identical, and he asked chemist Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin for a chemical analysis.

In a 1798 paper read before the Institut de France, Vauquelin reported that he found a new "earth" by dissolving aluminium hydroxide from emerald and beryl in an additional alkali. The editors of the journal Annales de chimie et de physique named the new earth "glucine" for the sweet taste of some of its compounds. Klaproth preferred the name "beryllina" due to the fact that yttria also formed sweet salts. The name beryllium was first used by Friedrich Wöhler in 1828.

Friedrich Wöhler and Antoine Bussy independently isolated beryllium in 1828 by the chemical reaction of metallic potassium with beryllium chloride, as follows:

- BeCl2 + 2 K → 2 KCl + Be

Using an alcohol lamp, Wöhler heated alternating layers of beryllium chloride and potassium in a wired-shut platinum crucible. The above reaction immediately took place and caused the crucible to become white hot. Upon cooling and washing the resulting gray-black powder, he saw that it was made of fine particles with a dark metallic luster. The highly reactive potassium had been produced by the electrolysis of its compounds, a process discovered 21 years earlier. The chemical method using potassium yielded only small grains of beryllium from which no ingot of metal could be cast or hammered.

The direct electrolysis of a molten mixture of beryllium fluoride and sodium fluoride by Paul Lebeau in 1898 resulted in the first pure (99.5 to 99.8%) samples of beryllium. However, industrial production started only after the First World War. The original industrial involvement included subsidiaries and scientists related to the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation in Cleveland, Ohio, and Siemens & Halske AG in Berlin. In the US, the process was ruled by Hugh S. Cooper, director of The Kemet Laboratories Company. In Germany, the first commercially successful process for producing beryllium was developed in 1921 by Alfred Stock and Hans Goldschmidt.

A sample of beryllium was bombarded with alpha rays from the decay of radium in a 1932 experiment by James Chadwick that uncovered the existence of the neutron. This same method is used in one class of radioisotope-based laboratory neutron sources that produce 30 neutrons for every million α particles.

Beryllium production saw a rapid increase during World War II due to the rising demand for hard beryllium-copper alloys and phosphors for fluorescent lights. Most early fluorescent lamps used zinc orthosilicate with varying content of beryllium to emit greenish light. Small additions of magnesium tungstate improved the blue part of the spectrum to yield an acceptable white light. Halophosphate-based phosphors replaced beryllium-based phosphors after beryllium was found to be toxic.

Electrolysis of a mixture of beryllium fluoride and sodium fluoride was used to isolate beryllium during the 19th century. The metal's high melting point makes this process more energy-consuming than corresponding processes used for the alkali metals. Early in the 20th century, the production of beryllium by the thermal decomposition of beryllium iodide was investigated following the success of a similar process for the production of zirconium, but this process proved to be uneconomical for volume production.

Pure beryllium metal did not become readily available until 1957, even though it had been used as an alloying metal to harden and toughen copper much earlier. Beryllium could be produced by reducing beryllium compounds such as beryllium chloride with metallic potassium or sodium. Currently, most beryllium is produced by reducing beryllium fluoride with magnesium. The price on the American market for vacuum-cast beryllium ingots was about $338 per pound ($745 per kilogram) in 2001.

Between 1998 and 2008, the world's production of beryllium had decreased from 343 to about 200 tonnes. It then increased to 230 metric tons by 2018, of which 170 tonnes came from the United States.

Etymology

Beryllium was named for the semiprecious mineral beryl, from which it was first isolated. The name beryllium was introduced by Wöhler in 1828.

Although Humphry Davy failed to isolate it, he proposed the name glucium for the new metal, derived from the name glucina for the earth it was found in; altered forms of this name, glucinium or glucinum (symbol Gl) continued to be used into the 20th century. Both beryllium and glucinum were used concurrently until 1949, when the IUPAC adopted beryllium as the standard name of the element.

Applications

Radiation windows

Because of its low atomic number and very low absorption for X-rays, the oldest and still one of the most important applications of beryllium is in radiation windows for X-ray tubes. Extreme demands are placed on purity and cleanliness of beryllium to avoid artifacts in the X-ray images. Thin beryllium foils are used as radiation windows for X-ray detectors, and their extremely low absorption minimizes the heating effects caused by high-intensity, low energy X-rays typical of synchrotron radiation. Vacuum-tight windows and beam-tubes for radiation experiments on synchrotrons are manufactured exclusively from beryllium. In scientific setups for various X-ray emission studies (e.g., energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) the sample holder is usually made of beryllium because its emitted X-rays have much lower energies (≈100 eV) than X-rays from most studied materials.

Low atomic number also makes beryllium relatively transparent to energetic particles. Therefore, it is used to build the beam pipe around the collision region in particle physics setups, such as all four main detector experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (ALICE, ATLAS, CMS, LHCb), the Tevatron and at SLAC. The low density of beryllium allows collision products to reach the surrounding detectors without significant interaction, its stiffness allows a powerful vacuum to be produced within the pipe to minimize interaction with gases, its thermal stability allows it to function correctly at temperatures of only a few degrees above absolute zero, and its diamagnetic nature keeps it from interfering with the complex multipole magnet systems used to steer and focus the particle beams.

Mechanical applications

Because of its stiffness, light weight and dimensional stability over a wide temperature range, beryllium metal is used for lightweight structural components in the defense and aerospace industries in high-speed aircraft, guided missiles, spacecraft, and satellites, including the James Webb Space Telescope. Several liquid-fuel rockets have used rocket nozzles made of pure beryllium. Beryllium powder was itself studied as a rocket fuel, but this use has never materialized. A small number of extreme high-end bicycle frames have been built with beryllium. From 1998 to 2000, the McLaren Formula One team used Mercedes-Benz engines with beryllium-aluminium alloy pistons. The use of beryllium engine components was banned following a protest by Scuderia Ferrari.

Mixing about 2.0% beryllium into copper forms an alloy called beryllium copper that is six times stronger than copper alone. Beryllium alloys are used in many applications because of their combination of elasticity, high electrical conductivity and thermal conductivity, high strength and hardness, nonmagnetic properties, as well as good corrosion and fatigue resistance. These applications include non-sparking tools that are used near flammable gases (beryllium nickel), springs, membranes (beryllium nickel and beryllium iron) used in surgical instruments, and high temperature devices. As little as 50 parts per million of beryllium alloyed with liquid magnesium leads to a significant increase in oxidation resistance and decrease in flammability.

The high elastic stiffness of beryllium has led to its extensive use in precision instrumentation, e.g. in inertial guidance systems and in the support mechanisms for optical systems. Beryllium-copper alloys were also applied as a hardening agent in "Jason pistols", which were used to strip the paint from the hulls of ships.

In sound amplification systems, the speed at which sound travels directly affects the resonant frequency of the amplifier, thereby influencing the range of audible high-frequency sounds. Beryllium stands out due to its exceptionally high speed of sound propagation compared to other metals. This unique property allows beryllium to achieve higher resonant frequencies, making it an ideal material for use as a diaphragm in high-quality loudspeakers.

Beryllium was used for cantilevers in high-performance phonograph cartridge styli, where its extreme stiffness and low density allowed for tracking weights to be reduced to 1 gram while still tracking high frequency passages with minimal distortion.

An earlier major application of beryllium was in brakes for military airplanes because of its hardness, high melting point, and exceptional ability to dissipate heat. Environmental considerations have led to substitution by other materials.

To reduce costs, beryllium can be alloyed with significant amounts of aluminium, resulting in the AlBeMet alloy (a trade name). This blend is cheaper than pure beryllium, while still retaining many desirable properties.

Mirrors

Beryllium mirrors are of particular interest. Large-area mirrors, frequently with a honeycomb support structure, are used, for example, in meteorological satellites where low weight and long-term dimensional stability are critical. Smaller beryllium mirrors are used in optical guidance systems and in fire-control systems, e.g. in the German-made Leopard 1 and Leopard 2 main battle tanks. In these systems, very rapid movement of the mirror is required, which again dictates low mass and high rigidity. Usually the beryllium mirror is coated with hard electroless nickel plating which can be more easily polished to a finer optical finish than beryllium. In some applications, the beryllium blank is polished without any coating. This is particularly applicable to cryogenic operation where thermal expansion mismatch can cause the coating to buckle.

The James Webb Space Telescope has 18 hexagonal beryllium sections for its mirrors, each plated with a thin layer of gold. Because JWST will face a temperature of 33 K, the mirror is made of gold-plated beryllium, which is capable of handling extreme cold better than glass. Beryllium contracts and deforms less than glass and remains more uniform in such temperatures. For the same reason, the optics of the Spitzer Space Telescope are entirely built of beryllium metal.

Magnetic applications

Beryllium is non-magnetic. Therefore, tools fabricated out of beryllium-based materials are used by naval or military explosive ordnance disposal teams for work on or near naval mines, since these mines commonly have magnetic fuzes. They are also found in maintenance and construction materials near magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines because of the high magnetic fields generated. In the fields of radio communications and powerful (usually military) radars, hand tools made of beryllium are used to tune the highly magnetic klystrons, magnetrons, traveling wave tubes, etc., that are used for generating high levels of microwave power in the transmitters.

Nuclear applications

Thin plates or foils of beryllium are sometimes used in nuclear weapon designs as the very outer layer of the plutonium pits in the primary stages of thermonuclear bombs, placed to surround the fissile material. These layers of beryllium are good "pushers" for the implosion of the plutonium-239, and they are good neutron reflectors, just as in beryllium-moderated nuclear reactors.

Beryllium is commonly used in some neutron sources in laboratory devices in which relatively few neutrons are needed (rather than having to use a nuclear reactor or a particle accelerator-powered neutron generator). For this purpose, a target of beryllium-9 is bombarded with energetic alpha particles from a radioisotope such as polonium-210, radium-226, plutonium-238, or americium-241. In the nuclear reaction that occurs, a beryllium nucleus is transmuted into carbon-12, and one free neutron is emitted, traveling in about the same direction as the alpha particle was heading. Such alpha decay-driven beryllium neutron sources, named "urchin" neutron initiators, were used in some early atomic bombs. Neutron sources in which beryllium is bombarded with gamma rays from a gamma decay radioisotope, are also used to produce laboratory neutrons.

Beryllium is used in fuel fabrication for CANDU reactors. The fuel elements have small appendages that are resistance brazed to the fuel cladding using an induction brazing process with Be as the braze filler material. Bearing pads are brazed in place to prevent contact between the fuel bundle and the pressure tube containing it, and inter-element spacer pads are brazed on to prevent element to element contact.

Beryllium is used at the Joint European Torus nuclear-fusion research laboratory, and it will be used in the more advanced ITER to condition the components which face the plasma. Beryllium has been proposed as a cladding material for nuclear fuel rods, because of its good combination of mechanical, chemical, and nuclear properties. Beryllium fluoride is one of the constituent salts of the eutectic salt mixture FLiBe, which is used as a solvent, moderator and coolant in many hypothetical molten salt reactor designs, including the liquid fluoride thorium reactor (LFTR).

Acoustics

The low weight and high rigidity of beryllium make it useful as a material for high-frequency speaker drivers. Because beryllium is expensive (many times more than titanium), hard to shape due to its brittleness, and toxic if mishandled, beryllium tweeters are limited to high-end home, pro audio, and public address applications. Some high-fidelity products have been fraudulently claimed to be made of the material.

Some high-end phonograph cartridges used beryllium cantilevers to improve tracking by reducing mass.

Electronic

Beryllium is a p-type dopant in III-V compound semiconductors. It is widely used in materials such as GaAs, AlGaAs, InGaAs and InAlAs grown by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). Cross-rolled beryllium sheet is an excellent structural support for printed circuit boards in surface-mount technology. In critical electronic applications, beryllium is both a structural support and heat sink. The application also requires a coefficient of thermal expansion that is well matched to the alumina and polyimide-glass substrates. The beryllium-beryllium oxide composite "E-Materials" have been specially designed for these electronic applications and have the additional advantage that the thermal expansion coefficient can be tailored to match diverse substrate materials.

Beryllium oxide is useful for many applications that require the combined properties of an electrical insulator and an excellent heat conductor, with high strength and hardness and a very high melting point. Beryllium oxide is frequently used as an insulator base plate in high-power transistors in radio frequency transmitters for telecommunications. Beryllium oxide is being studied for use in increasing the thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide nuclear fuel pellets. Beryllium compounds were used in fluorescent lighting tubes, but this use was discontinued because of the disease berylliosis which developed in the workers who were making the tubes.

Medical applications

Beryllium is a component of several dental alloys. Beryllium is used in X-ray windows because it is transparent to X-rays, allowing for clearer and more efficient imaging. In medical imaging equipment, such as CT scanners and mammography machines, beryllium's strength and light weight enhance durability and performance. Beryllium is used in analytical equipment for blood, HIV, and other diseases. Beryllium alloys are used in surgical instruments, optical mirrors, and laser systems for medical treatments.

Toxicity and safety

Main articles: Acute beryllium poisoning and Berylliosis| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

| Pictograms |

|

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H301, H315, H317, H319, H330, H335, H350i, H372 |

| Precautionary statements | P201, P202, P280, P302, P304, P305+P351+P338, P310, P340, P352 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

|

Biological effects

Approximately 35 micrograms of beryllium is found in the average human body, an amount not considered harmful. Beryllium is chemically similar to magnesium and therefore can displace it from enzymes, which causes them to malfunction. Because Be is a highly charged and small ion, it can easily get into many tissues and cells, where it specifically targets cell nuclei, inhibiting many enzymes, including those used for synthesizing DNA. Its toxicity is exacerbated by the fact that the body has no means to control beryllium levels, and once inside the body, beryllium cannot be removed.

Inhalation

Chronic beryllium disease (CBD), or berylliosis, is a pulmonary and systemic granulomatous disease caused by inhalation of dust or fumes contaminated with beryllium; either large amounts over a short time or small amounts over a long time can lead to this ailment. Symptoms of the disease can take up to five years to develop; about a third of patients with it die and the survivors are left disabled. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) lists beryllium and beryllium compounds as Category 1 carcinogens.

Occupational exposure

In the US, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has designated a permissible exposure limit (PEL) for beryllium and beryllium compounds of 0.2 μg/m as an 8-hour time-weighted average (TWA) and 2.0 μg/m as a short-term exposure limit over a sampling period of 15 minutes. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) upper-bound threshold of 0.5 μg/m. The IDLH (immediately dangerous to life and health) value is 4 mg/m. The toxicity of beryllium is on par with other toxic metalloids/metals, such as arsenic and mercury.

Exposure to beryllium in the workplace can lead to a sensitized immune response, and over time development of berylliosis. NIOSH in the United States researches these effects in collaboration with a major manufacturer of beryllium products. NIOSH also conducts genetic research on sensitization and CBD, independently of this collaboration.

Acute beryllium disease in the form of chemical pneumonitis was first reported in Europe in 1933 and in the United States in 1943. A survey found that about 5% of workers in plants manufacturing fluorescent lamps in 1949 in the United States had beryllium-related lung diseases. Chronic berylliosis resembles sarcoidosis in many respects, and the differential diagnosis is often difficult. It killed some early workers in nuclear weapons design, such as Herbert L. Anderson.

Beryllium may be found in coal slag. When the slag is formulated into an abrasive agent for blasting paint and rust from hard surfaces, the beryllium can become airborne and become a source of exposure.

Although the use of beryllium compounds in fluorescent lighting tubes was discontinued in 1949, potential for exposure to beryllium exists in the nuclear and aerospace industries, in the refining of beryllium metal and the melting of beryllium-containing alloys, in the manufacturing of electronic devices, and in the handling of other beryllium-containing material.

Detection

Early researchers undertook the highly hazardous practice of identifying beryllium and its various compounds from its sweet taste. A modern test for beryllium in air and on surfaces has been developed and published as an international voluntary consensus standard, ASTM D7202. The procedure uses dilute ammonium bifluoride for dissolution and fluorescence detection with beryllium bound to sulfonated hydroxybenzoquinoline, allowing up to 100 times more sensitive detection than the recommended limit for beryllium concentration in the workplace. Fluorescence increases with increasing beryllium concentration. The new procedure has been successfully tested on a variety of surfaces and is effective for the dissolution and detection of refractory beryllium oxide and siliceous beryllium in minute concentrations (ASTM D7458). The NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods contains methods for measuring occupational exposures to beryllium.

Notes

- The thermal expansion is anisotropic: the parameters (at 20 °C) for each crystal axis are αa = 12.03×10/K, αc = 8.88×10/K, and αaverage = αV/3 = 10.98×10/K.

References

- "Standard Atomic Weights: Beryllium". CIAAW. 2013.

- Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (4 May 2022). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- Be(0) has been observed; see "Beryllium(0) Complex Found". Chemistry Europe. 13 June 2016.

- "Beryllium: Beryllium(I) Hydride compound data" (PDF). bernath.uwaterloo.ca. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 14.48. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ Jakubke, Hans-Dieter; Jeschkeit, Hans, eds. (1994). Concise Encyclopedia Chemistry. trans. rev. Eagleson, Mary. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Hoover, Mark D.; Castorina, Bryan T.; Finch, Gregory L.; Rothenberg, Simon J. (October 1989). "Determination of the Oxide Layer Thickness on Beryllium Metal Particles". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. 50 (10): 550–553. doi:10.1080/15298668991375146. ISSN 0002-8894. PMID 2801503.

- ^ Tomastik, C.; Werner, W.; Stori, H. (2005). "Oxidation of beryllium—a scanning Auger investigation". Nucl. Fusion. 45 (9): 1061. Bibcode:2005NucFu..45.1061T. doi:10.1088/0029-5515/45/9/005. S2CID 111381179.

- ^ Maček, Andrej; McKenzie Semple, J. (1969). "Experimental burning rates and combustion mechanisms of single beryllium particles". Symposium (International) on Combustion. 12 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1016/S0082-0784(69)80393-0.

- Puchta, Ralph (2011). "A brighter beryllium". Nature Chemistry. 3 (5): 416. Bibcode:2011NatCh...3..416P. doi:10.1038/nchem.1033. PMID 21505503.

- Chong, S; Lee, KS; Chung, MJ; Han, J; Kwon, OJ; Kim, TS (January 2006). "Pneumoconiosis: comparison of imaging and pathologic findings". Radiographics. 26 (1): 59–77. doi:10.1148/rg.261055070. PMID 16418244.

- ^ Behrens, V. (2003). "11 Beryllium". In Beiss, P. (ed.). Landolt-Börnstein – Group VIII Advanced Materials and Technologies: Powder Metallurgy Data. Refractory, Hard and Intermetallic Materials. Landolt-Börnstein - Group VIII Advanced Materials and Technologies. Vol. 2A1. Berlin: Springer. pp. 667–677. doi:10.1007/10689123_36. ISBN 978-3-540-42942-5.

- ^ Hausner, Henry H. (1965). "Nuclear Properties". Beryllium its Metallurgy and Properties. University of California Press. p. 239. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Tomberlin, T. A. (15 November 2004). "Beryllium – A Unique Material in Nuclear Applications" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory. Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015.

- "About Beryllium". US Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- Ekspong, G. (1992). Physics: 1981–1990. World Scientific. pp. 172 ff. ISBN 978-981-02-0729-8. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Emsley 2001, p. 56.

- "Beryllium: Isotopes and Hydrology". University of Arizona, Tucson. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- Whitehead, N; Endo, S; Tanaka, K; Takatsuji, T; Hoshi, M; Fukutani, S; Ditchburn, Rg; Zondervan, A (February 2008). "A preliminary study on the use of (10)Be in forensic radioecology of nuclear explosion sites". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 99 (2): 260–70. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2007.07.016. PMID 17904707.

- Boyd, R. N.; Kajino, T. (1989). "Can Be-9 provide a test of cosmological theories?". The Astrophysical Journal. 336: L55. Bibcode:1989ApJ...336L..55B. doi:10.1086/185360.

- Arnett, David (1996). Supernovae and nucleosynthesis. Princeton University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-691-01147-9. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Johnson, Bill (1993). "How to Change Nuclear Decay Rates". University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- Hammond, C. R. "Elements" in Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- Hansen, P. G.; Jensen, A. S.; Jonson, B. (1995). "Nuclear Halos". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science. 45 (45): 591–634. Bibcode:1995ARNPS..45..591H. doi:10.1146/annurev.ns.45.120195.003111.

- "Abundance in the sun". Mark Winter, The University of Sheffield and WebElements Ltd, UK. WebElements. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ O'Neil, Marydale J.; Heckelman, Patricia E.; Roman, Cherie B., eds. (2006). The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (14th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA: Merck Research Laboratories, Merck & Co., Inc. ISBN 978-0-911910-00-1.

- ^ Emsley 2001, p. 59.

- "Abundance in oceans". Mark Winter, The University of Sheffield and WebElements Ltd, UK. WebElements. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- "Abundance in stream water". Mark Winter, The University of Sheffield and WebElements Ltd, UK. WebElements. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- "Search Minerals By Chemistry". www.mindat.org. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Walsh, Kenneth A (2009). "Sources of Beryllium". Beryllium chemistry and processing. ASM International. pp. 20–26. ISBN 978-0-87170-721-5. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Phillip Sabey (5 March 2006). "Distribution of major deposits". In Jessica Elzea Kogel; Nikhil C. Trivedi; James M. Barker; Stanley T. Krukowski (eds.). Industrial minerals & rocks: commodities, markets, and uses. pp. 265–269. ISBN 978-0-87335-233-8. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Emsley 2001, p. 58.

- "Sources of Beryllium". Materion Corporation. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- "Beryllim" Archived 3 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine in 2016 Minerals Yearbook. USGS (September 2018).

- Уральский производитель изумрудов планирует выпускать стратегический металл бериллий Archived 11 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. TASS.ru (15 May 2019)

- "Russia restarts beryllium production after 20 years". Eurasian Business Briefing. 20 February 2015. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Montero-Campillo, M. Merced; Mó, Otilia; Yáñez, Manuel; Alkorta, Ibon; Elguero, José (1 January 2019), van Eldik, Rudi; Puchta, Ralph (eds.), "Chapter Three - The beryllium bond", Advances in Inorganic Chemistry, Computational Chemistry, vol. 73, Academic Press, pp. 73–121, doi:10.1016/bs.adioch.2018.10.003, S2CID 140062833, retrieved 26 October 2022

- Arrowsmith, Merle; Braunschweig, Holger; Celik, Mehmet Ali; Dellermann, Theresa; Dewhurst, Rian D.; Ewing, William C.; Hammond, Kai; Kramer, Thomas; Krummenacher, Ivo (2016). "Neutral zero-valent s-block complexes with strong multiple bonding". Nature Chemistry. 8 (9): 890–894. Bibcode:2016NatCh...8..890A. doi:10.1038/nchem.2542. PMID 27334631.

- Gimferrer, Martí; Danés, Sergi; Vos, Eva; Yildiz, Cem B.; Corral, Inés; Jana, Anukul; Salvador, Pedro; Andrada, Diego M. (7 June 2022). "The oxidation state in low-valent beryllium and magnesium compounds". Chemical Science. 13 (22): 6583–6591. doi:10.1039/D2SC01401G. ISSN 2041-6539. PMC 9172369. PMID 35756523.

- ^ Boronski, Josef T.; Crumpton, Agamemnon E.; Wales, Lewis L.; Aldridge, Simon (16 June 2023). "Diberyllocene, a stable compound of Be(I) with a Be–Be bond". Science. 380 (6650): 1147–1149. Bibcode:2023Sci...380.1147B. doi:10.1126/science.adh4419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 37319227. S2CID 259166086.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Wiberg, Egon; Holleman, Arnold Frederick (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ Alderghi, Lucia; Gans, Peter; Midollini, Stefano; Vacca, Alberto (2000). Sykes, A.G; Cowley, Alan H. (eds.). "Aqueous Solution Chemistry of Beryllium". Advances in Inorganic Chemistry. 50. San Diego: Academic Press: 109–172. doi:10.1016/S0898-8838(00)50003-8. ISBN 978-0-12-023650-3.

- Bell, N.A. (1972). Advances in Inorganic Chemistry and Radiochemistry. Vol. 14. New York: Academic Press. pp. 256–277. doi:10.1016/S0065-2792(08)60008-4. ISBN 978-0-12-023614-5.

- ^ Kumberger, Otto; Schmidbaur, Hubert (December 1993). "Warum ist Beryllium so toxisch?". Chemie in unserer Zeit (in German). 27 (6): 310–316. doi:10.1002/ciuz.19930270611. ISSN 0009-2851.

- Rosenheim, Arthur; Lehmann, Fritz (1924). "Über innerkomplexe Beryllate". Liebigs Ann. Chem. 440: 153–166. doi:10.1002/jlac.19244400115.

- Schmidt, M.; Bauer, A.; Schier, A.; Schmidtbauer, H (1997). "Beryllium Chelation by Dicarboxylic Acids in Aqueous Solution". Inorganic Chemistry. 53b (10): 2040–2043. doi:10.1021/ic961410k. PMID 11669821.

- ^ Mederos, A.; Dominguez, S.; Chinea, E.; Brito, F.; Middolini, S.; Vacca, A. (1997). "Recent aspects of the coordination chemistry of the very toxic cation beryllium(II): The search for sequestering agents". Bol. Soc. Chil. Quim. 42: 281.

- ^ Naglav, D.; Buchner, M. R.; Bendt, G.; Kraus, F.; Schulz, S. (2016). "Off the Beaten Track—A Hitchhiker's Guide to Beryllium Chemistry". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (36): 10562–10576. doi:10.1002/anie.201601809. PMID 27364901.

- Coates, G. E.; Francis, B. R. (1971). "Preparation of base-free beryllium alkyls from trialkylboranes. Dineopentylberyllium, bis((trimethylsilyl)methyl)beryllium, and an ethylberyllium hydride". Journal of the Chemical Society A: Inorganic, Physical, Theoretical: 1308. doi:10.1039/J19710001308.

- Fischer, Ernst Otto; Hofmann, Hermann P. (1959). "Über Aromatenkomplexe von Metallen, XXV. Di-cyclopentadienyl-beryllium". Chemische Berichte. 92 (2): 482. doi:10.1002/cber.19590920233.

- Nugent, K. W.; Beattie, J. K.; Hambley, T. W.; Snow, M. R. (1984). "A precise low-temperature crystal structure of Bis(cyclopentadienyl)beryllium". Australian Journal of Chemistry. 37 (8): 1601. doi:10.1071/CH9841601. S2CID 94408686.

- Almenningen, A.; Haaland, Arne; Lusztyk, Janusz (1979). "The molecular structure of beryllocene, (C5H5)2Be. A reinvestigation by gas phase electron diffraction". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 170 (3): 271. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)92065-5.

- Wong, C. H.; Lee, T. Y.; Chao, K. J.; Lee, S. (1972). "Crystal structure of bis(cyclopentadienyl)beryllium at −120 °C". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 28 (6): 1662. Bibcode:1972AcCrB..28.1662W. doi:10.1107/S0567740872004820.

- Wiegand, G.; Thiele, K.-H. (1974). "Ein Beitrag zur Existenz von Allylberyllium- und Allylaluminiumverbindungen". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie (in German). 405: 101–108. doi:10.1002/zaac.19744050111.

- Chmely, Stephen C.; Hanusa, Timothy P.; Brennessel, William W. (2010). "Bis(1,3-trimethylsilylallyl)beryllium". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 49 (34): 5870–5874. doi:10.1002/anie.201001866. PMID 20575128.

- Ruhlandt-Senge, Karin; Bartlett, Ruth A.; Olmstead, Marilyn M.; Power, Philip P. (1993). "Synthesis and structural characterization of the beryllium compounds , , and ⋅PhMe and determination of the structure of ". Inorganic Chemistry. 32 (9): 1724–1728. doi:10.1021/ic00061a031.

- Morosin, B.; Howatson, J. (1971). "The crystal structure of dimeric methyl-1-propynyl- beryllium-trimethylamine". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 29: 7–14. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)87485-9.

- ^ Weeks 1968, p. 535.

- ^ Weeks 1968, p. 536.

- Weeks 1968, p. 537.

- Vauquelin, Louis-Nicolas (1798). "De l'Aiguemarine, ou Béril; et découverie d'une terre nouvelle dans cette pierre" [Aquamarine or beryl; and discovery of a new earth in this stone]. Annales de Chimie. 26: 155–169. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- In a footnote on page 169 Archived 23 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine of (Vauquelin, 1798), the editors write: "(1) La propriété la plus caractéristique de cette terre, confirmée par les dernières expériences de notre collègue, étant de former des sels d'une saveur sucrée, nous proposons de l'appeler glucine, de γλυκυς, doux, γλυκύ, vin doux, γλυκαιτω, rendre doux ... Note des Rédacteurs." ((1) The most characteristic property of this earth, confirmed by the recent experiments of our colleague , being to form salts with a sweet taste, we propose to call it glucine from γλυκυς, sweet, γλυκύ, sweet wine, γλυκαιτω, to make sweet ... Note of the editors.)

- Klaproth, Martin Heinrich, Beitrage zur Chemischen Kenntniss der Mineralkörper (Contribution to the chemical knowledge of mineral substances), vol. 3, (Berlin, (Germany): Heinrich August Rottmann, 1802), pages 78–79 Archived 26 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine: "Als Vauquelin der von ihm im Beryll und Smaragd entdeckten neuen Erde, wegen ihrer Eigenschaft, süsse Mittelsalze zu bilden, den Namen Glykine, Süsserde, beilegte, erwartete er wohl nicht, dass sich bald nachher eine anderweitige Erde finden würde, welche mit völlig gleichem Rechte Anspruch an diesen Namen machen können. Um daher keine Verwechselung derselben mit der Yttererde zu veranlassen, würde es vielleicht gerathen seyn, jenen Namen Glykine aufzugeben, und durch Beryllerde (Beryllina) zu ersetzen; welche Namensveränderung auch bereits vom Hrn. Prof. Link, und zwar aus dem Grunde empfohlen worden, weil schon ein Pflanzengeschlecht Glycine vorhanden ist." (When Vauquelin conferred – on account of its property of forming sweet salts – the name glycine, sweet-earth, on the new earth that had been found by him in beryl and smaragd, he certainly didn't expect that soon thereafter another earth would be found which with fully equal right could claim this name. Therefore, in order to avoid confusion of it with yttria-earth, it would perhaps be advisable to abandon this name glycine and replace it with beryl-earth (beryllina); which name change was also recommended by Prof. Link, and for the reason that a genus of plants, Glycine, already exists.)

- Weeks 1968, p. 538.

- Wöhler, F. (1828). "Ueber das Beryllium und Yttrium" [On beryllium and yttrium]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 13 (89): 577–582. Bibcode:1828AnP....89..577W. doi:10.1002/andp.18280890805. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Wöhler, Friedrich (1828). "Ueber das Beryllium und Yttrium". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 89 (8): 577–582. Bibcode:1828AnP....89..577W. doi:10.1002/andp.18280890805. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Bussy, Antoine (1828). "D'une travail qu'il a entrepris sur le glucinium". Journal de Chimie Médicale (4): 456–457. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Weeks 1968, p. 539.

- Boillat, Johann (27 August 2016). From Raw Material to Strategic Alloys. The Case of the International Beryllium Industry (1919–1939). 1st World Congress on Business History, At Bergen – Norway. doi:10.13140/rg.2.2.35545.11363. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Kane, Raymond; Sell, Heinz (2001). "A Review of Early Inorganic Phosphors". Revolution in lamps: a chronicle of 50 years of progress. Fairmont Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-88173-378-5. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Babu, R. S.; Gupta, C. K. (1988). "Beryllium Extraction – A Review". Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review. 4: 39–94. doi:10.1080/08827508808952633.

- Hammond, C.R. (2003). "The Elements". CRC handbook of chemistry and physics (84th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-8493-0595-5. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- "Beryllium Statistics and Information". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- "Commodity Summary: Beryllium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- "Commodity Summary 2000: Beryllium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- "etymology online". Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica". Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- "Elemental Matter". Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- "4. Beryllium - Elementymology & Elements Multidict". elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- Robinson, Ann E. (6 December 2019). "Order From Confusion: International Chemical Standardization and the Elements, 1947-1990". Substantia: 83–99 Pages. doi:10.13128/SUBSTANTIA-498.

- Veness, R.; Ramos, D.; Lepeule, P.; Rossi, A.; Schneider, G.; Blanchard, S. "Installation and commissioning of vacuum systems for the LHC particle detectors" (PDF). CERN. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- Wieman, H; Bieser, F.; Kleinfelder, S.; Matis, H. S.; Nevski, P.; Rai, G.; Smirnov, N. (2001). "A new inner vertex detector for STAR" (PDF). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A. 473 (1–2): 205. Bibcode:2001NIMPA.473..205W. doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(01)01149-4. S2CID 39909027. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Davis, Joseph R. (1998). "Beryllium". Metals handbook. ASM International. pp. 690–691. ISBN 978-0-87170-654-6. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Schwartz, Mel M. (2002). Encyclopedia of materials, parts, and finishes. CRC Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-56676-661-6. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- "Museum of Mountain Bike Art & Technology: American Bicycle Manufacturing". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Ward, Wayne. "Aluminium-Beryllium". Ret-Monitor. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Collantine, Keith (8 February 2007). "Banned! – Beryllium". Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Geller, Elizabeth, ed. (2004). Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry. New York City: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-143953-4.

- "Defence forces face rare toxic metal exposure risk". The Sydney Morning Herald. 1 February 2005. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- Reactor Material Specifications (Report). Oak Ridge National Laboratory. 1958. p. 227. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- "6 Common Uses Of Beryllium". Refractory Metals. 28 April 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- "Shure V15VxMR User's Guide". Shure. p. 2.

- "The Webb Space Telescope Will Rewrite Cosmic History. If It Works". Quanta Magazine. 3 December 2021. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- Gardner, Jonathan P. (2007). "The James Webb Space Telescope" (PDF). Proceedings of Science: 5. Bibcode:2007mru..confE...5G. doi:10.22323/1.052.0005. S2CID 261976160. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- Werner, M. W.; Roellig, T. L.; Low, F. J.; Rieke, G. H.; Rieke, M.; Hoffmann, W. F.; Young, E.; Houck, J. R.; et al. (2004). "The Spitzer Space Telescope Mission". Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 154 (1): 1–9. arXiv:astro-ph/0406223. Bibcode:2004ApJS..154....1W. doi:10.1086/422992. S2CID 119379934.

- Gray, Theodore. Gyroscope sphere. An example of the element Beryllium Archived 14 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine. periodictable.com

- Kojola, Kenneth; Lurie, William (9 August 1961). "The selection of low-magnetic alloys for EOD tools". Naval Weapons Plant Washington DC. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Dorsch, Jerry A. & Dorsch, Susan E. (2007). Understanding anesthesia equipment. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 891. ISBN 978-0-7817-7603-5. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Barnaby, Frank (1993). How nuclear weapons spread. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-415-07674-6. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Byrne, J. Neutrons, Nuclei, and Matter, Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 2011, ISBN 0-486-48238-3, pp. 32–33.

- Clark, R. E. H.; Reiter, D. (2005). Nuclear fusion research. Springer. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-540-23038-0. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Petti, D.; Smolik, G.; Simpson, M.; Sharpe, J.; Anderl, R.; Fukada, S.; Hatano, Y.; Hara, M.; et al. (2006). "JUPITER-II molten salt Flibe research: An update on tritium, mobilization and redox chemistry experiments". Fusion Engineering and Design. 81 (8–14): 1439. Bibcode:2006FusED..81.1439P. doi:10.1016/j.fusengdes.2005.08.101. OSTI 911741. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- "Scan Speak offers Be tweeters to OEMs and Do-It-Yourselfers" (PDF). Scan Speak. May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- Johnson, John E. Jr. (12 November 2007). "Usher Be-718 Bookshelf Speakers with Beryllium Tweeters". Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- "Exposé E8B studio monitor". KRK Systems. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- "Beryllium use in pro audio Focal speakers". Archived from the original on 31 December 2012.

- "VUE Audio announces use of Be in Pro Audio loudspeakers". VUE Audiotechnik. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- Svilar, Mark (8 January 2004). "Analysis of "Beryllium" Speaker Dome and Cone Obtained from China". Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- "Shure V15 VXmR User Guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- Diehl, Roland (2000). High-power diode lasers. Springer. p. 104. ISBN 978-3-540-66693-6. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- "Purdue engineers create safer, more efficient nuclear fuel, model its performance". Purdue University. 27 September 2005. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- Breslin AJ (1966). "Ch. 3. Exposures and Patterns of Disease in the Beryllium Industry". In Stokinger, HE (ed.). Beryllium: Its Industrial Hygiene Aspects. Academic Press, New York. pp. 30–33. ISBN 978-0-12-671850-8.

- OSHA Hazard Information Bulletin HIB 02-04-19 (rev. 05-14-02) Preventing Adverse Health Effects From Exposure to Beryllium in Dental Laboratories

- Elshahawy, W.; Watanabe, I. (2014). "Biocompatibility of dental alloys used in dental fixed prosthodontics". Tanta Dental Journal. 11 (2): 150–159. doi:10.1016/j.tdj.2014.07.005.

- "Beryllium Windows". European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- Zheng, Li; Wang, Xiao (2020). "Progress in the Application of Rare Light Metal Beryllium". Materials Science Forum. 977: 261–271. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.977.261.

- "Beryllium Foil". Refractory Metals. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- Minnath, Mehar (2018). "7 - Metals and alloys for biomedical applications". In Balakrishnan, Preetha (ed.). Fundamental Biomaterials: Metals (1st ed.). Woodhead Publishing. pp. 167–174. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102205-4.00007-6. ISBN 978-0081022054.

- Maksimov, O. (2005). "Berryllium chalogenide alloys for visible light emitting and laser diode" (PDF). Rev.Adv.Mater.Sc. 9: 178–183. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- "Beryllium 265063". Sigma-Aldrich. 24 July 2021. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Emsley 2001, p. 57.

- Venugopal, B. (14 March 2013). Physiologic and Chemical Basis for Metal Toxicity. Springer. pp. 167–8. ISBN 978-1-4684-2952-7.

- "Beryllium and Beryllium Compounds". IARC Monograph. Vol. 58. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 1993. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0054". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Arsenic (inorganic compounds, as As)". Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Mercury compounds. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Archived 7 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "CDC – Beryllium Research- NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- Emsley 2001, p. 5.

- "Photograph of Chicago Pile One Scientists 1946". Office of Public Affairs, Argonne National Laboratory. 19 June 2006. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- Newport News Shipbuilding Workers Face a Hidden Toxin, Daily Press (Virginia), Michael Welles Shapiro, 31 August 2013

- International Programme on Chemical Safety (1990). "Beryllium: ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH CRITERIA 106". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- "ASTM D7458 –08". American Society for Testing and Materials. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- Minogue, E. M.; Ehler, D. S.; Burrell, A. K.; McCleskey, T. M.; Taylor, T. P. (2005). "Development of a New Fluorescence Method for the Detection of Beryllium on Surfaces". Journal of ASTM International. 2 (9): 13168. doi:10.1520/JAI13168.

- "CDC – NIOSH Publications and Products – NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (2003–154) – Alpha List B". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

Cited sources

- Emsley, John (2001). Nature's Building Blocks: An A–Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- Mackay, Kenneth Malcolm; Mackay, Rosemary Ann; Henderson, W. (2002). Introduction to modern inorganic chemistry (6th ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-7487-6420-4.

- Weeks, Mary Elvira; Leichester, Henry M. (1968). Discovery of the Elements. Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education. LCCCN 68-15217.

Further reading

- Newman LS (2003). "Beryllium". Chemical & Engineering News. 81 (36): 38. doi:10.1021/cen-v081n036.p038.

- Mroz MM, Balkissoon R, and Newman LS. "Beryllium". In: Bingham E, Cohrssen B, Powell C (eds.) Patty's Toxicology, Fifth Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons 2001, 177–220.

- Walsh, KA, Beryllium Chemistry and Processing. Vidal, EE. et al. Eds. 2009, Materials Park, OH:ASM International.

- Beryllium Lymphocyte Proliferation Testing (BeLPT). DOE Specification 1142–2001. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Energy, 2001.

- 2007, Eric Scerri,The periodic table: Its story and its significance, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-19-530573-9

External links

- ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine: Beryllium Toxicity Archived 4 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- It's Elemental – Beryllium

- MSDS: ESPI Metals

- Beryllium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health – Beryllium Page

- National Supplemental Screening Program (Oak Ridge Associated Universities)

- Historic Price of Beryllium in USA

| Beryllium compounds | |

|---|---|

| Beryllium(I) | |

| Beryllium(II) |

|

| Periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alkaline earth metals | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

The formation of a complex is in competition with the metal ion-hydrolysis reaction and mixed complexes with both the anion and the hydroxide ion are also formed. For example, derivatives of the cyclic trimer are known, with a bidentate ligand replacing one or more pairs of water molecules.

The formation of a complex is in competition with the metal ion-hydrolysis reaction and mixed complexes with both the anion and the hydroxide ion are also formed. For example, derivatives of the cyclic trimer are known, with a bidentate ligand replacing one or more pairs of water molecules.

, was isolated long ago. Aromatic hydroxy ligands (i.e.

, was isolated long ago. Aromatic hydroxy ligands (i.e.