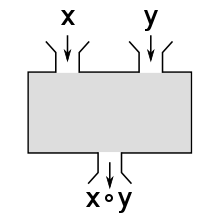

In mathematics, a binary operation or dyadic operation is a rule for combining two elements (called operands) to produce another element. More formally, a binary operation is an operation of arity two.

More specifically, a binary operation on a set is a binary function whose two domains and the codomain are the same set. Examples include the familiar arithmetic operations of addition, subtraction, and multiplication. Other examples are readily found in different areas of mathematics, such as vector addition, matrix multiplication, and conjugation in groups.

A binary function that involves several sets is sometimes also called a binary operation. For example, scalar multiplication of vector spaces takes a scalar and a vector to produce a vector, and scalar product takes two vectors to produce a scalar.

Binary operations are the keystone of most structures that are studied in algebra, in particular in semigroups, monoids, groups, rings, fields, and vector spaces.

Terminology

More precisely, a binary operation on a set is a mapping of the elements of the Cartesian product to :

The closure property of a binary operation expresses the existence of a result for the operation given any pair of operands.

If is not a function but a partial function, then is called a partial binary operation. For instance, division of real numbers is a partial binary operation, because one can not divide by zero: is undefined for every real number . In both model theory and classical universal algebra, binary operations are required to be defined on all elements of . However, partial algebras generalize universal algebras to allow partial operations.

Sometimes, especially in computer science, the term binary operation is used for any binary function.

Properties and examples

Typical examples of binary operations are the addition () and multiplication () of numbers and matrices as well as composition of functions on a single set. For instance,

- On the set of real numbers , is a binary operation since the sum of two real numbers is a real number.

- On the set of natural numbers , is a binary operation since the sum of two natural numbers is a natural number. This is a different binary operation than the previous one since the sets are different.

- On the set of matrices with real entries, is a binary operation since the sum of two such matrices is a matrix.

- On the set of matrices with real entries, is a binary operation since the product of two such matrices is a matrix.

- For a given set , let be the set of all functions . Define by for all , the composition of the two functions and in . Then is a binary operation since the composition of the two functions is again a function on the set (that is, a member of ).

Many binary operations of interest in both algebra and formal logic are commutative, satisfying for all elements and in , or associative, satisfying for all , , and in . Many also have identity elements and inverse elements.

The first three examples above are commutative and all of the above examples are associative.

On the set of real numbers , subtraction, that is, , is a binary operation which is not commutative since, in general, . It is also not associative, since, in general, ; for instance, but .

On the set of natural numbers , the binary operation exponentiation, , is not commutative since, (cf. Equation x = y), and is also not associative since . For instance, with , , and , , but . By changing the set to the set of integers , this binary operation becomes a partial binary operation since it is now undefined when and is any negative integer. For either set, this operation has a right identity (which is ) since for all in the set, which is not an identity (two sided identity) since in general.

Division (), a partial binary operation on the set of real or rational numbers, is not commutative or associative. Tetration (), as a binary operation on the natural numbers, is not commutative or associative and has no identity element.

Notation

Binary operations are often written using infix notation such as , , or (by juxtaposition with no symbol) rather than by functional notation of the form . Powers are usually also written without operator, but with the second argument as superscript.

Binary operations are sometimes written using prefix or (more frequently) postfix notation, both of which dispense with parentheses. They are also called, respectively, Polish notation and reverse Polish notation .

Binary operations as ternary relations

A binary operation on a set may be viewed as a ternary relation on , that is, the set of triples in for all and in .

Other binary operations

For example, scalar multiplication in linear algebra. Here is a field and is a vector space over that field.

Also the dot product of two vectors maps to , where is a field and is a vector space over . It depends on authors whether it is considered as a binary operation.

See also

- Category:Properties of binary operations

- Iterated binary operation – Repeated application of an operation to a sequence

- Magma (algebra) – Algebraic structure with a binary operation

- Operator (programming) – Construct associated with a mathematical operation in computer programsPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Ternary operation – Mathematical operation that combines three elements to produce another element

- Truth table § Binary operations

- Unary operation – Mathematical operation with only one operand

Notes

- Rotman 1973, pg. 1

- Hardy & Walker 2002, pg. 176, Definition 67

- Fraleigh 1976, pg. 10

- Hall 1959, pg. 1

- George A. Grätzer (2008). Universal Algebra (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. Chapter 2. Partial algebras. ISBN 978-0-387-77487-9.

References

- Fraleigh, John B. (1976), A First Course in Abstract Algebra (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-01984-1

- Hall, Marshall Jr. (1959), The Theory of Groups, New York: Macmillan

- Hardy, Darel W.; Walker, Carol L. (2002), Applied Algebra: Codes, Ciphers and Discrete Algorithms, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-067464-8

- Rotman, Joseph J. (1973), The Theory of Groups: An Introduction (2nd ed.), Boston: Allyn and Bacon

External links

| Mathematical logic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||

| Theorems (list) and paradoxes | |||||||||

| Logics |

| ||||||||

| Set theory |

| ||||||||

| Formal systems (list), language and syntax |

| ||||||||

| Proof theory | |||||||||

| Model theory | |||||||||

| Computability theory | |||||||||

| Related | |||||||||

is a rule for combining the arguments

is a rule for combining the arguments  and

and  to produce

to produce

is a

is a  to

to

is not a

is not a  is undefined for every real number

is undefined for every real number  . In both

. In both  ) and

) and  ) of

) of  ,

,  is a binary operation since the sum of two real numbers is a real number.

is a binary operation since the sum of two real numbers is a real number. ,

,  of

of  matrices with real entries,

matrices with real entries,  is a binary operation since the sum of two such matrices is a

is a binary operation since the sum of two such matrices is a  is a binary operation since the product of two such matrices is a

is a binary operation since the product of two such matrices is a  , let

, let  . Define

. Define  by

by  for all

for all  , the composition of the two functions

, the composition of the two functions  and

and  in

in  for all elements

for all elements  in

in  for all

for all  in

in  , is a binary operation which is not commutative since, in general,

, is a binary operation which is not commutative since, in general,  . It is also not associative, since, in general,

. It is also not associative, since, in general,  ; for instance,

; for instance,  but

but  .

.

, is not commutative since,

, is not commutative since,  (cf.

(cf.  . For instance, with

. For instance, with  ,

,  , and

, and  ,

,  , but

, but  . By changing the set

. By changing the set  , this binary operation becomes a partial binary operation since it is now undefined when

, this binary operation becomes a partial binary operation since it is now undefined when  and

and  ) since

) since  for all

for all  in general.

in general.

), a partial binary operation on the set of real or rational numbers, is not commutative or associative.

), a partial binary operation on the set of real or rational numbers, is not commutative or associative.  ), as a binary operation on the natural numbers, is not commutative or associative and has no identity element.

), as a binary operation on the natural numbers, is not commutative or associative and has no identity element.

,

,  ,

,  or (by

or (by  rather than by functional notation of the form

rather than by functional notation of the form  . Powers are usually also written without operator, but with the second argument as

. Powers are usually also written without operator, but with the second argument as  and

and  .

.

in

in  for all

for all  is a

is a