Images depicting (A) a cannabis plant illustration from a 14th-century medical treatise, kept at the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome; (B) the remains of an open-air tank previously used for the retting of hemp stalks in Cercenasco, Piedmont; (C) a museum room dedicated to traditional hemp-processing tools in Lazio; (D) an 18th-century silk-embroidered hemp curtain from Tuscany; (E) the Cave of the Ropemakers in Sicily in 1900; and (F) a 30-gun Venetian light frigate returning from the Levant.

Images depicting (A) a cannabis plant illustration from a 14th-century medical treatise, kept at the Biblioteca Casanatense in Rome; (B) the remains of an open-air tank previously used for the retting of hemp stalks in Cercenasco, Piedmont; (C) a museum room dedicated to traditional hemp-processing tools in Lazio; (D) an 18th-century silk-embroidered hemp curtain from Tuscany; (E) the Cave of the Ropemakers in Sicily in 1900; and (F) a 30-gun Venetian light frigate returning from the Levant.

The cultivation of cannabis in Italy has a long history dating back to Roman times, when it was primarily used to produce hemp ropes, although pollen records from core samples show that Cannabaceae plants were present in the Italian peninsula since at least the Late Pleistocene, while the earliest evidence of their use dates back to the Bronze Age. For a long time after the fall of Rome in the 5th century A.D., the cultivation of hemp, although present in several Italian regions, mostly consisted in small-scale productions aimed at satisfying the local needs for fabrics and ropes. Known as canapa in Italian, the historical ubiquity of hemp is reflected in the different variations of the name given to the plant in the various regions, including canape, càneva, canava, and canva (or canavòn for female plants) in northern Italy; canapuccia and canapone in the Po Valley; cànnavo in Naples; cànnavu in Calabria; cannavusa and cànnavu in Sicily; cànnau and cagnu in Sardinia.

The mass cultivation of industrial cannabis for the production of hemp fiber in Italy really took off during the period of the Maritime Republics and the Age of Sail, due to its strategic importance for the naval industry. In particular, two main economic models were implemented between the 15th and 19th centuries for the cultivation of hemp, and their primary differences essentially derived from the diverse relationships between landowners and hemp producers. The Venetian model was based on a state monopoly system, by which the farmers had to sell the harvested hemp to the Arsenal at an imposed price, in order to ensure preferential, regular, and advantageous supplies of the raw material for the navy, as a matter of national security. Such system was particularly developed in the southern part of the province of Padua, which was under the direct control of the administrators of the Arsenal. Conversely, the Emilian model, which was typical of the provinces of Bologna and Ferrara, was strongly export-oriented and it was based on the mezzadria farming system by which, for instance, Bolognese landowners could relegate most of the production costs and risks to the farmers, while also keeping for themselves the largest share of the profits.

From the 18th century onwards, hemp production in Italy established itself as one of the most important industries at an international level, with the most productive areas being located in Emilia-Romagna, Campania, and Piedmont. The well renowned and flourishing Italian hemp sector continued well after the unification of the country in 1861, only to experience a sudden decline during the second half of the 20th century, with the introduction of synthetic fibers and the start of the war on drugs, and only recently it is slowly experiencing a resurgence.

Prehistory

The family of Cannabaceae includes the two genera of cannabis and humulus, with the former believed to be native exclusively to Asia, while the latter also to Europe. In particular, while humulus naturally dispersed from Asia to Europe without human agency, cannabis is commonly thought to have been spread by humans once its multiple uses, most importantly those involving its fiber, had been discovered and developed by the various cultures. At present, cannabis sativa is classified as an archaeophyte alien species for Italy, with sporadic wild occurrences being attributed to escaped plants, which are non-naturalized and distinct from the wild oriental varieties.

According to Greek historian and geographer Herodotus, the Scythians brought hemp from Central Asia to Europe during their migrations around 1500 B.C., while the Teutons were a major factor in the spread of the cultivation of hemp throughout Europe. Another proposed theory is that hemp may have been introduced into the continent by the earliest incursions of the Aryans into Thrace and Western Europe, although no evidence of its presence was found in the lake dwellings of Switzerland and northern Italy. Still other sources attribute the introduction of hemp into Italy to the arrivals of both the Scythians and the Illyrians between the 10th and the 8th centuries B.C. while, by the 6th and 5th centuries B.C., hemp cultivation was present throughout Italy.

Earliest evidence

In any case, the oldest evidence of the presence of cannabis and humulus in central Italy dates back to the Late Glacial, long before the development of agriculture in western Eurasia, as inferred from sediment cores extracted from the Albano and Nemi lakes. The presence of cannabis pollen grains in sediments dated to the early Holocene suggests that the plant could have been introduced earlier, or that an indigenous hemp population may have already been present in the area before its domestication during the Bronze Age. Other prehistoric sites where sediment cores revealed the presence of hemp include the Great Lake of Monticchio, in Basilicata; and the coastal seabed of the Central Adriatic region, from a time when these sites would have been above sea level. Traces of hemp pollen have also been found in several Neolithic sites in anthropogenic contexts, which would indicate the probable cultivation of the plant during that period. These include three Middle Neolithic (i.e. 4500–4000 B.C.) sites in the areas of Piacenza, Parma, and Forlì in Emilia-Romagna; as well as other sites near the Annone and Alserio lakes in Lombardy, from 5000 B.C. onwards. Furthermore, while the sites where hemp pollen has been found are currently scarce for the Bronze Age, they increase in number for the Iron Age, especially during the centuries of Roman domination.

In regard to the sediment cores from central Italy, humulus pollen values increase during the mid Holocene, while hemp pollen grains become more frequent at the transition between the Neolithic and the Copper Age, with concentrations increasing and becoming more common only from the Bronze Age onwards. In addition, the sediment records show an increase in the human influence on the local vegetation, with hemp pollen values starting to rise from about 3000 cal BP (i.e. 1050 B.C.) onwards, and reaching their earliest peak during the 1st century A.D., as a clear consequence of the cultivation of hemp by the Romans, although the pre-Roman trends can be attributed to natural sources, and possibly to anthropogenic sources as well. Later peaks in the pollen records from central Italy also show clear evidence of hemp cultivation during the Medieval period.

In terms of the earliest evidence of the processing of hemp for the production of strings and fabrics in Italy, three micro-fragments of what appear to be hemp fibers were detected through a scanning electron microscope in the dental calculi of three female individuals from the Early Bronze Age. Furthermore, the analysis of the teeth of 28 females and one male from the same period, revealed evidence of activity-induced dental modifications that are consistent with yarn production, or weaving preparation, of small-diameter threads, which were repeatedly pulled across the fronts and sides of the individuals' upper incisors and canines. All the examined individuals were buried in an ancient cemetery located in Gricignano di Aversa, in southern Italy, and traces of hemp were also found attached to a metal blade, possibly the remains of a fabric sheath, in the tomb of an adult male within the same site. These findings show the importance that hemp fabrics had in the region at the time, as well as clear gender-based role divisions in the manufacturing of fibers.

Magna Graecia

In 1954, a now-famous hypogaeum was excavated by Italian archaeologist Pellegrino Claudio Sestieri in the Ancient Greek colony of Poseidonia, Magna Graecia, in the area of modern-day Capaccio Paestum. Dated to the late 6th century B.C., the underground structure was identified as a heroon possibly dedicated to the unknown founder of the city, based on the retrieved artifacts, which included eight bronze vases (i.e. six hydriai and two amphoras). Other proposed interpretations of the structure included a Nymph sanctuary, the cenotaph of the founder of Sybaris, or a Chthonian sanctuary; however, as very little written records are available from the considered period, the organic content of the vases constitutes the primary source of knowledge regarding the purpose of the sacellum.

In 2023, a scientific research paper was published regarding the detection of a significant quantity of cannabis pollen inside some of the hydriai, as well as of oil traces that were compatible with hemp oil. As the analyzed organic content of the vases was not consistent with the main Mediterranean ritual organic matters (e.g. honey, olive oil, and wine), it could not be attributed to a possible local heroic cult; while the fact that the pollen mainly came from male cannabis plants ruled out the use of said plants for intoxicating purposes.

Instead, the presence of cannabis could be attributed to environmental contamination, whether during the processing of the content (if the oil traces are indeed from hemp), the deposition of the vases and the sealing of the room, or possibly more recently during the excavation, storage, and handling of the archaeological find. Although the oil processing hypothesis is unlikely due to the fact that hemp oil would have been produced from the seeds of female plants, airborne pollen contamination from a local cultivation area before the room was closed is possible, with male hemp plants usually flowering earlier than female ones. Other potential causes also include a contemporary symbolic use of hemp plants, and the possible use of hemp textiles to decorate the room, since male plants were the preferred source of fiber.

Ancient Carthage

In 1969, the remains of two Punic ships from the 3rd century B.C. were discovered off the shore of Isola Lunga, not far from Lilybaion, on the western coast of Carthaginian Sicily. The two ships are believed to have been sunk during the First Punic War of 264–241 B.C., specifically at the Battle of the Aegates of 10 March 241 B.C., which was fought between the Carthaginian and Roman fleets. In 1971, a team led by the Cypriot-English pioneer of underwater archaeology Honor Frost uncovered from the site a few baskets that contained distinctive yellowish stems, no more than 3 cm (1.18 in) in length, which were later identified as similar to cannabis sativa.

As the stems were always found in association with food, in the presumed area of the ship's kitchen, it was postulated that cannabis could have been consumed by the Punic oarsmen possibly for its supposed mind-focusing abilities. Such postulation was based on a 1972 study on the use of the drug by Jamaican workmen, which states that almost without exception users maintain that ganja enhances their ability to perform manual labour, and they regularly consume ganja with this objective; however, Dr. Frost recognized that whether the Carthaginians would make an infusion potent enough to give fighting men "Dutch courage" is less certain.

Ancient Rome

Tun' mare transilias? Tibi torta cannabe fulto coena sit in transtro?

Note. Apostrophe from the Satura V by Persius, directed at Lucius Annaeus Cornutus, attesting the use of hemp ropes in Roman ships, meaning Would you bound over the sea? Would you have your dinner on a thwart, seated on a coil of hemp?.

One of the earliest authors from the Roman Republic to mention industrial hemp was satirist Gaius Lucilius, in the 2nd century B.C., who referenced thomices, an ancient greek word used to indicate lightly twisted ropes obtained from rough hemp and broom, out of which cords were made. The plant was later mentioned by Marcus Terentius Varro in his De re rustica, a work on agriculture written in 37 B.C., where hemp is listed together with other plants used for their fibers, namely flax, reeds, palm, and bulrushes. In the 1st century A.D., Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder described in his Naturalis Historia the cultivation and use of cannabis plants in the Roman Empire, both for industrial and medical purposes, while hemp is also mentioned in the satires of Persius and Juvenal. As the Roman territories expanded, the cultivation and use of cannabis plants spread to various parts of both Italy and the wider European continent. As an example, several pieces of rope tentatively identified as made of hemp were found within the well of a Roman fort in Dunbartonshire, Caledonia, which was occupied during the period 140–180 A.D., and the find attests to the likelihood that the earliest introduction of hemp in Britain came by Roman agency.

The hemp fiber was mainly used by the Romans to produce ropes, sheets, wickers, and nets; in particular Pliny mentions three Alabandica varieties to be the best ones to be used for hunting nets, the variety cultivated in Mylasa to be the second best, and the hemp grown in the Sabine territory to be particularly tall. In regard to woven fabrics, archaeological excavations at Pompeii, in Campania felix (i.e. part of what is now Campania), unearthed samples of hemp textiles that had been preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D., reportedly including cloth sandals made of hemp, although linen was generally preferred in Antiquity for the production of canvas, sails, and clothing. In 1992, further textile samples were recovered from a lead sarcophagus that belonged to an upper-class elderly woman, who lived between the 4th and 5th centuries A.D., and was buried in a Roman necropolis located in Albintimilium, in the coastal area of Liguria that now constitutes the Region of the same name. Based on morphological and morphometrical analyses, the recovered fibers were later identified as most likely being fragments of cannabis sativa, although a slight chance was recognized that they could actually belong to low quality linen.

In terms of the extension of hemp cultivation in Italia, precise information is not available besides a few unverified archaeological data and the hemp variety mentioned by Pliny, which was grown in the area of Reate, in Sabinum. Nevertheless, two important epigraphic sources attest to the cultivation and trade of hemp by the Romans in the peninsula, namely a sepulchral inscription uncovered in Bovolenta and dated between the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., that mentions the cannabetum (i.e. an area reserved to hemp cultivation); and a lead tag uncovered in the area around Altinum, in Venetia, and dated between the 1st century B.C. and the 1st century A.D., that labelled a cargo of six balls of wool and a small quantity of hemp.

Cannabis cultivation and processing

According to Pliny, Roman farmers would sow hemp seeds during spring and harvest the ripe hemp seeds after the autumn equinox, after which they were dried in the sun, or the wind, or by the smoke of a fire, while the hemp plants were plucked after the vintage, to be then peeled and cleaned. Moreover, according to the De re rustica by contemporary agricultural writer Lucius Columella, hemp plants require either rich, manured, and well-watered soil, or alternatively soil that is level, moist, and deeply worked. Ancient Romans would plant six hemp seeds per pes quadratus (0.0876 m; 0.943 sq ft) toward the end of February however, if the weather was rainy, sowing could be done up to the spring equinox without harming the crop. One of the last Roman authors to mention hemp was Palladius in his Opus agriculturae, a treatise written around the late 4th – early 5th century A.D., which essentially repeats what was reported by Columella on cannabis cultivation. In terms of articles of commerce, useful information on the price of both hemp and hemp-derived products can be found in the Edict on Maximum Prices, issued in 301 A.D. by Emperor Diocletian, which established price caps equal to 80 denarii per modius (8.73 L; 1.92 imp gal) of hemp seeds, and 4 denarii per libra (372.5 g; 131.4 oz) of processed hemp, while it increased to 6 and 8 denarii for ropes and strings, respectively. These maximum prices were relatively modest when compared to more expensive products, such as flax seeds, linen, and wool, which attests to the lower demand for hemp products at the time.

In 2018, excavations on the eastern bank of the ancient Natiso cum Turro river of Aquileia, in the area of Venetia et Histria that is now Friuli-Venezia Giulia, revealed the first system of basins from the Roman world that is known to have been used for the maceration of hemp, as inferred from archaeobotanical and archaeo-palynological studies of the site. The long and shallow pools were dated between the late 2nd – 3rd A.D. and the late 3rd – early 4th century A.D.; they were delimited by parapets made of clay, sand, and tiny pebbles; and they were coated with thin layers of cocciopesto for waterproofing. Similarly to more recent water retting procedures, the harvested stalks of cannabis sativa were bundled into sheaves and then submerged into either stagnant or running water by tying them to dedicated poles, to extract the fiber. According to studies carried out in Venetia, hemp cultivation in the Upper Adriatic region was not intensive, rather it was either the result of self-sufficiency policies or, if it occurred on a larger scale, a complementary sector to the local wool industry, which was well developed in Aquileia at the time. In addition, sulphurous waters from hot springs, such as those that can be found in the area around Aquileia, found usage in Antiquity in the maceration of both hemp and flax, which were then used in the production of cordage and fishing nets, in the manufacture of wool blend fabrics, as well as in the processing of both wool and wool products.

Cannabis consumption

In Italia, different parts of the hemp plants were used for various culinary purposes, in particular Pliny mentions hemp seeds being stored in pots for later use and lasting for as much as one year, while the stalks and branches were used as vegetables. Most notably, a recipe for cannabis-based food intended to be consumed at wedding receptions can be found in the De re culinaria, a collection of Roman cookery recipes thought to have been compiled in the 5th century A.D., and whose authorship is unclear. In terms of the contemporary beliefs on cannabis plants and the effects of their personal use, according to Pliny, wild hemp first grew in woods and had darker and rougher leaves, while its seeds were said to cause impotence. The juice derived from it was used to drive out worms and other creatures that could enter the ears, although it would cause headache as a side effect, and it was said to be so potent that it was able to coagulate water when it was poured into it. Furthermore, when the hemp juice was mixed with water and then drunk by beasts of burden, it was said to be able to regulate their bowels.

In regard to medical properties, hemp roots boiled in water were thought to ease cramped joints, gout, and similar violent pains, while they could also be applied raw to burns, but they would be changed before getting dry. The ability of boiled cannabis roots to lessen inflammation was also attested by contemporary Greek physician and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides in his De Materia Medica, a pharmacopoeia that mainly focuses on medicinal plants. In regard to the recreational use of cannabis in the Roman Empire, 2nd century Greek physician and philosopher Claudius Galenus wrote that it was customary in Italia to serve small cannabis-based cakes for dessert, whose seeds would reportedly create a feeling of warmth and increase thirst. Moreover, if consumed in large quantities, these small cakes would affect the head by emitting a warm and toxic vapor, which produced torpor or sluggishness; while it was also customary for the Romans to offer guests hemp seeds as a promoter of hilarity. Similarly, it has been hypothesized that Pliny probably referenced cannabis when mentioning gelotophyllis (i.e. the leaves of laughter), which he said grew along the Borysthenes river, in Scythia, as well as in Bactria, an ancient country located in the northeastern part of modern-day Afghanistan, or at least in the general area of central Asia. According to Pliny, if these leaves were taken in myrrh and wine, all kinds of phantoms would beset the mind, causing a laughter that persisted until the kernels of pine nuts were taken with pepper and honey in palm wine.

In 2019, a scientific study was published which aimed at reconstructing the lifestyle of a Roman Imperial community, that lived between the 1st and 3rd centuries A.D. near the ancient town of Cures, in Sabinum. As part of the ethnobotanical evidence, 11 micro-residues of Cannabaceae plant tissue were recovered from the dental calculi of 27 individuals buried in a Roman necropolis, which was discovered in 2015 near Passo Corese, in Lazio. The studied fragments, most likely hemp fibers, were identified through observations made under optical microscope, which were then cross-referenced with the available laboratory collections of fibers, literature data, as well as the particular cultural and chronological context. The proposed reasons for the presence of hemp fibers in the analyzed dental calculi include their possible inhalation during hemp processing activities; the ingestion of food and beverages whose ingredients had been preserved in hemp sacks; and the intake of hemp exudates and extracts for therapeutic purposes.

Middle Ages

Canapa, lino, e lenta, prima semenza.

Note. Umbrian proverb from Valnerina on the importance of hemp, meaning Hemp, flax, and lentil, first among seeds.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 A.D., and the concurrent migration period lasting between the 4th and 6th centuries A.D., detailed information on the cultivation of hemp in Italy before 1000 A.D. is scarce, even though its processing for industrial and commercial purposes is well attested during that period. Nevertheless, cannabis cultivation across the Italian peninsula must have been severely limited, particularly between the 4th and 8th centuries A.D., considering that as much as two-thirds of the countryside was reportedly left in a state of almost complete abandon.

The mass cultivation of industrial cannabis in Medieval Italy started during the High Middle Ages, with the demographic and agricultural recoveries, the emergence of the textile industry, the rise of Medieval communes and the Maritime Republics, and the increase of their trade in the Mediterranean Sea. For instance, while linen was the main material used in sail production throughout Antiquity, to be then replaced by fustians (i.e. a mixed fiber of cotton and wool) during the Early Middle Ages, the greater resistance of hemp made it better suited for the new sailing structures required for the ships of ever-increasing tonnage that were being built between the 13th and 14th centuries. In fact, since the Middle Ages, hemp became the only fiber used in rope manufacturing and later, since the 16th century, a fundamental material for the construction of sails; and the substantial increase in the demand from arsenals drove up the price of hemp and incentivized its cultivation. The large quantities of hemp needed for the shipbuilding industry also led to the emergence of dedicated supply chains, with groups of merchants providing investments and organizing the transport of the fiber; as well as of specialized productions, with the hemp produced for arsenals acquiring specific characteristics when compared to the hemp intended for the general population.

Between 1304 and 1309, Bolognese jurist and landowner Pietro de' Crescenzi compiled an agricultural treatise entitled De agricultura vulgare, alternatively known as the Ruralia commoda, which includes a section on the cultivation of industrial cannabis at the time. In the treatise, hemp is described as having the same nature as flax, namely requiring similar air and soil, although the latter does not need to be ploughed as much. Nevertheless, for the production of ropes, the seeds must be planted in rich soil, to increase the resulting yield, while the sparser the seeds are planted, the more ramified the grown plants will be. Conversely, for the production of textiles such as cloth sacks, sheets, or shirts, the soil does not need to be as rich, while the seeds must be more densely sowed, to obtain plants without branches, which are more suitable for such products. Moreover, hemp fiber is described as necessary for the production of fishing nets, since it is more water resistant than flax fiber.

Furthermore, hemp seeds have been used for food for several centuries, especially by the poorer social classes, since they were inexpensive, rich in nutrients, and available even during droughts. In fact, several centuries-old Italian recipes use cannabis sativa as the main ingredient, and these recipes include:

- the Tortelli con fiori di canapaccia, described in a recipe from the 13th century;

- the Minestra di canapuccia, which is described as good for the invalids in the Registrum coquine, written around 1430 by Johannes de Bockenheim, who was a German clergyman and cook in the service of Pope Martin V;

- the Suppa fatta di semente di canepa, described by the 15th century culinary expert Maestro Martino;

- the Piatto di canapa and the Focaccia di canapa, both described in the De honesta voluptate et valetudine, written around 1465 by gastronomist Bartolomeo Sacchi.

Tales of the Hashishins

So he selected from among his drugs a powder of marvellous virtue, which he had gotten in the Levant from a great prince, who averred that 'twas wont to be used by the Old Man of the Mountain, when he would send any one to or bring him from his paradise, and that, without doing the recipient any harm, 'twould induce in him, according to the quantity of the dose, a sleep of such duration and quality that, while the efficacy of the powder lasted, none would deem him to be alive.

Note. Excerpt translated from the Decamerone by Boccaccio, which references the use of hashish among the Assassins.

One of the earliest mentions of the use of hashish in the Italian literature can be found in Il Milione, an account of Venetian merchant and explorer Marco Polo's travels through Asia between 1271 and 1295, that was written down by Pisan romance writer Rusticiano, with whom Marco Polo shared his prison cell in the Republic of Genoa, after his capture during the War of Curzola of 1295–1299. In the travelogue, the two authors talk about the Old Man of the Mountain, in reference to Persian leader Hasan-i Sabbah, who founded the Nizari Ismaili state in 1090 after taking control of the mountain fortress of Alamut; and the Order of Assassins, of which Hasan-i Sabbah was the first Grand Master, and whose very name derives from the word hashshāshīn (i.e. hashish users). Both the drug and the Old Man were later referenced in the Decamerone, a collection of short stories written by Florentine poet and Renaissance humanist Giovanni Boccaccio in 1353.

Republic of Venice

Se la luna xe in colore, el canego more.

Note. Venetian proverb from the popular tradition, meaning If the Moon is in color, the hemp dies.

The cultivation of industrial cannabis in Veneto dates back to at least the 13th century, as attested in an official document from the civil authorities of Montagnana, which in 1290 prohibited the drying of the processed hemp in public places, to protect passers-by from its foul odor. Conversely, the mass production of naval ropes, cables, and hawsers from hemp at the Venetian Arsenal commenced between 1303 and 1322, when the first corderia was established, known as the Tana hemp house. The used raw hemp was mainly imported through trade agreements from the Don river delta, on the Azov Sea, where the Venetians established several trading posts, whose importance is attested by the fact that the Tana hemp house most likely derived its name from Tanais, the ancient greek name for both the Don river and the Greek colony on its delta. Nevertheless, to maintain favorable prices and ensure steady supplies, especially after losing their trading posts on the Black Sea to the Republic of Genoa, Venice further imported hemp mainly from Emilia, and to a lesser extent the Marches, Piedmont, and the Middle East, while also incentivizing its own domestic production.

In the Republic of Venice, industrial cannabis was a state monopoly whose price was fixed for public uses, while both its hoarding and exportation were prohibited, and its maceration and storage were strictly regulated. The strategic importance of the raw material for shipbuilding is also attested by its exemption from tariffs, as well as by several deliberations and provisions from both the Venetian Judiciary and Senate, that were aimed at the protection and promotion of hemp cultivation in the mainland. In particular, after its expansion into the Venetian hinterland at the beginning of the 15th century, the Republic started investing in the territory of Montagnana already in 1412, with the establishment of a warehouse where the locally produced hemp would be stored, prior to its transportation to Venice. Moreover, the patricians Nicolò Tron and Giovanni Moro were sent in 1455 to the districts of Montagnana and Cologna Veneta, to oversee the necessary hydraulic projects for the construction of several hemp maceration sites. As a result, public water retting sites were established in Montagnana, Este, and Cologna Veneta, while appointed magistrates were charged with monitoring the implementation of the relevant laws.

After the establishment of hemp fields in the area around Padua during the second half of the 15th century, Venice became independent from other countries for its strategic supplies. From the beginning, the agricultural policy project that allowed for this outcome was a joint venture between the public and private sectors, which gave rise to a hybrid organization by which the State determined cultivation procedures, quantities, and price, while the private land owners provided the fields and manpower. As a result of the widespread control exercised by the State, the hemp production in the Domini di Terraferma eventually became an extension of the organizational structure of the Arsenal. In order to further protect its domestic production, the Venetian Republic ended up imposing heavy import duties on hemp fiber in the second half of the 16th century, and eventually banned its importation altogether. Even though such measures received significant criticism due to their various repercussions on both trade and industries, they also resulted in the development of hemp cultivations in the territories of Polesine, Vicenza, Belluno, and Treviso. In fact, while Venice was never able to completely remove the need for hemp supplies from Bologna, the project did give hemp cultivation a stable role in the Veneto agriculture from the 18th century onwards, with the creation of an agro-industrial chain.

Hemp and warfare

The manufacture of cordage in our house of the Tana is the security of our galleys and ships and similarly of our sailors and capital.

Note. Declaration attributed to the Venetian Senate, on the strategic importance of hemp ropes for the naval strength of the Republic.

In the context of the heavy losses suffered by the Venetian Navy at the Battle of Curzola on 9 September 1298, the Major Council approved the construction of the Tana hemp house on 7 July 1302, as part of the first enlargement of the Arsenal, to localize the storage of hemp and the production of ropes. Located on the southern side of the Arsenal, the elongated ropewalks were later reconstructed between 1579 and 1585 under architect Antonio da Ponte, resulting in a 317 m (1,040 ft) long and 21 m (68.9 ft) wide building divided into three aisles by two rows of 6 m (19.7 ft) tall and 1 m (3.3 ft) wide brick columns, for a total of 84 pillars.

The hemp was primarily used to manufacture cordage and sails for the Venetian fleet at low costs, but it was also used for caulking ship hulls. The ropes could also be sold at a lower price to foreign ships transiting at the port, thus making it competitive in the international market at the time, although sales from the Arsenal to private third parties required a specific licence issued by the authorities. After the victory of the Holy League against the Ottoman Empire at the Battle of Lepanto on 7 October 1571, the Venetian Senate charged the Arsenal with the upkeep of 100 thin galleys and 12 galleasses for the purpose of rapid deployment. Nevertheless, the heavy crisis of the late 16th century dealt a significant blow to the Venetian shipbuilding industry, leaving the Arsenal with a halved reserve of galleys in 1633. According to contemporary estimates, an 800-botti ship in 1586 required around 24 t (23.6 long tons) of hemp to supply its shrouds and cordage; while the hemp used for sails, ropes, and shrouds, represented 30% of the total cost of a galley in 1600.

In addition to the state-controlled production aimed at the needs of the Navy, private enterprises were also established for the manufacture of hemp yarns, ropes, and textiles, which became the subject of significant trade over time. As an example, the Morosini family oversaw a large trade network by the end of the 15th century, through which the patricians exported significant quantities of textiles, including hemp fabrics, all over the Mediterranean and the Near East. In particular, from the emporium that the Morosini established in Aleppo, such products could reach the markets of Damascus, Beirut, Famagosta, and Nicosia, among others.

Traditional hemp rope production

At the hemp house, the hemp fiber would arrive in large square bales, already macerated and dry, and it would be forcefully slammed against a wooden pole, equipped with metal rods, to complete the breakage of the stalk. The remaining woody fragments would then be removed using comb-like tools of different shapes for both coarser and finer combing, in preparation for the spinning phase. While using scutching tools with ever-finer teeth, the finest of which could have a teeth spacing as small as 1 mm (0.04 in), the artisans would gradually separate the different fibers based on their qualities, including their robustness and color. The spinning mechanism consisted in a large rotating wooden wheel, placed vertically and firmly fixed to the ground, equipped with laterally protruding rods that supported a winding rope connecting the wheel to several interchangeable wooden cylinders of different dimensions, depending on the final size of the rope to be produced, which were located a few meters away. The rotating wheel would make such cylinders spin, and they could be used to either twist a twine (with a single cylinder), or intertwine three or four strings (with multiple cylinders) to produce different types of rope.

Several other tools were used to keep the rope always tightly stretched, while also sustaining its weight along the ropewalk; to avoid hand contact with the rope during twisting; and to keep it constantly lubricated, thus preventing any damage from friction-related heat. Afterwards, the rope was soaked overnight, since the water would cause the twisted fibers to stick together, which would therefore increase the compactness of the rope. As a final touch, an iron mesh would subsequently be used to rub the rope, to remove the last few remaining streaks, while a stretch of coarse rope would be rolled up and run around the rope for a final smoothing and polishing. The produced ropes would then be safely stored, thus creating strategic stockpiles that would allow the Republic to remain independent from external suppliers during wartime. These stockpiles were overseen by three magistrates, known as the Visdomini alla Tana, who were elected by the Major Council, and one of the required checks was that the ropes produced for vessels had to be made from exactly 1,098 twisted hemp strings. When needed, the rope would be taken out of storage through dedicated holes, and cut at the required size, rather than already being produced at standardized lengths, while the fiber of any leftover would be repurposed.

After the fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797, with the arrival of Napoleon, the Tana hemp house ended its centuries-old activity, to be then turned into a warehouse, while it has more recently been used as an exhibition center during the Venice Biennale since 1980. The production of ropes was instead moved to the Corte dei Cordami (i.e. Cordage Courtyard) on the island of Giudecca, where hawsers were still being twisted in open-air ropewalks, and activities continued there up until 1995. The legacy of the once-thriving hemp rope industry, as well as many other related activities, is attested in the toponyms of several streets in Venice.

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The cultivation of hemp in southern Italy dates back to the Roman Empire, although the earliest records of its presence in the region attest that King Hiero II of Syracuse bought hemp from Gaul in the 3rd century B.C., to produce cordage for his vessels. During Roman times, a noteworthy center for the processing of hemp in Campania felix was located in Misenum, particularly for the production of hemp cordage for the ships in its important port. Most notably, refugees from Miseno eventually brought this trade to Frattamaggiore, which they reportedly founded around 850 A.D. after their hometown was raided and razed by the Saracens. After the fall of Rome, one of the first notable large-scale productions of hemp in Italy was established in the Emirate of Sicily starting from the 9th century, during the Arab domination. Cannabis cultivation in southern Italy continued during the Middle Ages, particularly for the production of textiles, with the establishment of renowned workshops under King Roger II of Sicily, which produced purple and golden fabrics, as well as textiles made from wool, hemp, and linen, for both local and foreign customers.

To regulate and increase both manufacturing and commerce, Emperor Frederick II promulgated several measures, including the establishment of annual fairs in the towns of Sulmona, Capua, Lucera, Bari, Taranto, Cosenza, Lanciano, and L'Aquila, on the occasions of their respective patron saints and lasting several days. At the time, the Kingdom of Sicily exported on average a third of its crops, which included hemp; and its maritime trade reached most notably the Byzantine Empire, Egypt, Spain, and France. Furthermore, in addition to local attendees, the aforementioned fairs also attracted merchants from the rest of the Italian states, Dalmatia, and Greece; while the Maritime Republics on the Tyrrhenian Sea supplied their arsenals with both raw and woven hemp from the ports of Naples and Amalfi. Under Frederick II, the exportation of hemp was subjected to the jus exiturae (i.e. right of exit), that is an exit tariff equal to 3 grana for every 100 canes of hemp; while the price of 30 canes of hemp was reported equal to 3 tarì and 8 grana, in a 1290 expenses register from the household of King Charles II of Naples.

Industrial cannabis production

The coats of arms of the comuni of (A) Arzano, depicting a bundle of three green branches (i.e. two of hemp and one of flax); and (B) San Marco Evangelista, depicting a single hemp plant in gold.

The coats of arms of the comuni of (A) Arzano, depicting a bundle of three green branches (i.e. two of hemp and one of flax); and (B) San Marco Evangelista, depicting a single hemp plant in gold.

La canapa per l'Annunziata, o seminata o nata.

Note. Proverb on the sowing period for hemp, meaning The hemp for the Annunciation, either sown or born, with the Feast of the Annunciation being celebrated on 25 March.

In 1231, Frederick II promulgated the Constitutiones Augustales, which included provisions to protect populated places in the Kingdom from the decomposition fumes emanating from the maceration basins. In particular, the provisions ordered that no one should be permitted to soak flax or hemp in water within a mile of any city or near a Castrum so that the quality of the air may not, as we have learned for certain, be corrupted by it, while anyone violating the decree would be brought to the royal court and have their macerated goods confiscated. In regard to the disposal of any waste from the retting process, the provisions also stipulate that any filth that make a stench should be thrown a quarter of a mile out of the district or into the sea or river by the persons to whom they belong, while anyone doing otherwise would have to pay the royal court as much as one augustalis, depending on the quantity of the illegal waste.

After significant public protests, King Charles II of Anjou decreed the closure and reclamation of several maceration sites around Naples in 1300 and 1306, even though the Royal coffers significantly benefited from renting state-owned wetlands and canals for the retting of both flax and hemp. Similar reclamation projects followed during the Angevin and Aragonese periods, until King Alfonso I of Aragon permanently moved the retting sites to the shallow Agnano lake, about 8 km (4.97 mi) west of Naples. Moreover, the Miano-Agnano highway, known as Via dei Canapi (i.e. Hemp street), was constructed to facilitate the transport of hemp between the fields North of Naples and the maceration sites at the lake, while also avoiding population centers. Despite two temporary bans, the first one during the plague of 1656 and the second one following the death of one of the sons of Viceroy Gaspar de Bracamonte from an infection in Pozzuoli in 1663, retting activities continued in the Phlegraean Fields until the second half of the 19th century, when they became unprofitable. Subsequently, the Agnano lake was decontaminated and drained between 1866 and 1870, with its surface at the time spanning between 90 ha (0.9 km; 0.3 sq mi) and 130 ha (1.3 km; 0.5 sq mi) within a volcanic crater about 2.07 km (1.29 mi) wide. This land reclamation project was carried out to remove the rotting fumes, as well as to prevent further outbreaks of the mosquito-borne malaria by reducing the local habitat of the Anopheles mosquito.

Nevertheless, from the 17th century onwards, the hemp cultivation area in Campania steadily increased to include the southern part of the modern-day Province of Caserta, and most of the former Province of Naples, including the sides of Mount Vesuvius. Furthermore, according to an economic census compiled under King Joachim-Napoleon, during the French rule of the Kingdom of Naples between 1806 and 1815, hemp fields were mainly located in the fertile Volturno river basin, between the comuni of Capua, Caserta, Maddaloni, and Aversa; while significant exports of hemp from Naples towards the rest of Europe were recorded around 1840. The legacy of the once-flourishing industry of hemp cultivation and processing in the area is attested in the toponyms of several streets and towns around Naples, while the comuni of Arzano and San Marco Evangelista even show a hemp plant in their coats of arms.

Hemp rope production

The oldest corderia that is still operating in Italy was established in 1796 in Castellammare di Stabia, in the Kingdom of Naples, to manufacture high-quality cordage from hemp as part of the local shipyard, which was founded in 1773 by royal decree of King Ferdinand IV of Naples. Two notable examples of Royal Italian Navy ships that were later built at said shipyard, and also supplied by the associated ropeyard, were the training ships RNS Cristoforo Colombo and Amerigo Vespucci. The RNS Cristoforo Colombo, launched in 1928, was a full-rigged three-masted tall ship that had twenty-six sails made from textile hemp, for a total area of about 2,500 m (26,910 sq ft), while the rigging ropes were made of both hemp and Manila hemp. The slightly larger twin ship NS Amerigo Vespucci, launched in 1931 and still in operation with the Italian Navy to the present day, has twenty-four sails made from textile hemp, for a total area of about 2,635 m (28,363 sq ft) and a thickness ranging between 2 mm (0.08 in) and 4 mm (0.16 in), while the rigging ropes are currently made of both Manila hemp and nylon.

Another noteworthy site for the production of ropes in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was located near the Ear of Dionysius in Syracuse, Sicily, where the wide humid spaces within the Grotta dei Cordari (i.e. Cave of the Ropemakers) have been used as ropewalks for centuries. The ropemakers of Syracuse formed their own guild, and in 1577 they were granted their own church, which subsequently became known as San Nicolò ai Cordari. At the time, the local hemp cultivation was significantly developed and profitable, and the produced fibers were in part used by the cordari to provide a moderate supply of various kinds of ropes. The decline of this industry began when the local farmers started to switch to more profitable crops, while the few remaining artisan families continued their trade by sourcing hemp from Campania, until the last ropemakers left the Cave in 1984 due to the risk of collapse.

Papal States

And I will extol hemp and the true culture of such a noble shoot, that in the Fields of Italy and, more than anywhere else, in the lands of Felsina and in the nearby most flourishing enclosure of Cento, it rises and grows green and forms shady forests.

Note. Excerpt translated from Il Canapajo by Baruffaldi, which attests the importance of hemp cultivation in the region.

Although only limited information is available on the cultivation of industrial cannabis in the Italian peninsula before 1000 A.D., historical-ecclesiastical accounts from the Early Middle Ages reported that a Roman community of artisans involved in the processing of hemp established workshops and dwellings around the late 6th – early 7th century A.D., in and around the remains of the Basilica Julia, in the Roman Forum. The trade of these canapari mainly consisted in the production of hemp twines and ropes, as well as possibly wickers, sacks, and rough textiles; and the spiritual life of the community centered around the small church of Santa Maria in Cannapara, which derived its name from said activities and was also located among the porticoes of the Basilica, until its demolition in the 16th century.

In any case, the cultivation of hemp in what are now Umbria and the Marches was already widespread by the mid 13th century, as attested in the cartulary of the Abbey of Sassovivo, and in ancient statutes of the town of Foligno, as well as other towns in the March of Ancona. After the affirmation of Papal rule over Romagna in the early 16th century, hemp and wheat became two of the main exports of the Papal States, so much so that several regulations emanated by Pope Paul III in 1543, and later reaffirmed by Pope Sixtus V in 1586, defined the processing standards required for hemp for it to be exported. In fact, the exportation of raw hemp from Bologna, when it was temporarily under Papal rule, had already been forbidden by a bull from Pope Gregory XI in 1376, to allow the inhabitants to keep the revenue derived from the processing of hemp plants, thus providing work to as many as 12,000 people in the city at the time. In addition, the export ban also prompted Venice to further increase its hemp cultivation area, particularly in the area around Padua.

Industrial use of cannabis

Torta tibi funes dat cannabis : utile semen oviparis : gravidis sed nocet ille cibus.

Note. Latin couplet on the usefulness of hemp, meaning Twisted cannabis gives you ropes : seed useful for the oviparous : but that food is harmful to pregnant women.

Hemp plants were used in their entirety, namely the roots were used as firewood, the woody stalk fragments were dipped in sulfur to produce matches, the seeds were used as food for livestock, and the fiber was used to make fishing nets, ropes to be used in various agricultural activities, and textiles such as packaging for fine linens, flour sacks, family clothing, and trousseaus for daughters' weddings. As they are particularly resistant, hemp fibers were also mixed with the more delicate wool to produce mezzalana (i.e. half-wool) fabrics, which were especially suitable for wear-prone textile products. Similarly, mixtures of hemp fibers with either linen or wool, known as pignolato (i.e. pine nuts patterned), were widely used in the area around Ferrara for the production of clothes, as reported by the local writer Riccobaldo in his Sermo de ritibus antiquorum.

To the present day, hemp is still being used in the area around Sant'Arcangelo di Romagna to produce textiles such as blankets, pillowcases, and tablecloths, decorated with copper stamps in the traditional green and rust colors, through a centuries-old artisan process that first requires a heavy mangle to smoothen and soften the initially rough and rigid hand-woven fabric. The production of hemp textiles was once so ubiquitous in Emilia-Romagna, where every farmhouse had a loom as part of the subsistence economy, that it even influenced the culinary history of the Region. More specifically, the similar local pasta varieties of Garganelli and Maccheroni al pettine (i.e. macaroni on reed) are still traditionally prepared by cutting a small square of fresh egg-based pasta, rolling it on a stick, and then pressing it on a wooden reed to create transverse ridges.

Another significant application of industrial cannabis was in papermaking, which originated in Han China and subsequently spread throughout the Muslim world, namely reaching Morocco and Spain during the 12th century, before arriving in Italy in the 13th century. In particular, the first paper mill in Italy was established in 1276 in Fabriano, where the local artisans improved upon the Arab techniques to produce highly resistant and durable paper, which slowly became the most widespread writing material since it was more convenient and cheaper than parchment. The raw materials used for the production of the paper included hemp and linen, and the calcium-rich soil typically found in many parts of Italy caused the cultivated cannabis sativa plants to produce a light-colored fiber, which resulted in a creamy white paper, while the long fibers gave the paper strength and flexibility, which was a desirable feature for books and manuscripts. Most notably, it has been suggested that German inventor and craftsman Johannes Gutenberg used hemp paper imported from Italy to print 140 copies of his Bible in the 15th century.

Historically, hemp cords were used by the Apostolic Chancery to fasten the bulla to the Pope's correspondence when such letters, known as litterae cum filo canapis, contained either orders or a papal delegation in a dispute. Conversely, Papal letters that brought some benefit to the recipient had the bulla fastened using silk cords, and thus they were known as litterae cum serico. Furthermore, hemp ropes were also widely used for the numerous architectural and engineering projects that took place in Rome, and Foligno in particular is cited by architect Domenico Fontana as a major producer of hemp fiber. As an example, Roman ropemakers used fiber from Foligno to produce the significant amount of cordage that was used to move the Vatican obelisk from the spina of the Circus of Nero to the Vatican Hill, and then re-erect it at the center of St. Peter's Square in 1586, for a total of 4,700 canne (10.5 km; 6.65 mi) of rope with an average thickness equal to a third of a palm (7.17 cm; 2.82 in).

Industrial cannabis cultivation

Panis vita, cañabis protectio, vinum laetitia.

Note. Latin inscription meaning Bread is life, hemp is protection, wine is joy, painted across three decorated vaults of the porticoes of Bologna, under the Scappi tower, where market stalls selling such products would once be set up.

Another important center for cannabis production was located near Viterbo, in Lazio, in the town of Canepina, which derives its name from the once locally widespread cultivation of the plant. In particular, the lands surrounding the town are rich in water, which flowed along a multitude of streams and rivulets, while the predominantly stony grounds caused the local hemp to acquire a pure white color, which made it particularly sought-after in all contemporary markets, and especially by Roman noblewomen.

In Umbria, industrial cannabis was cultivated both in the river valleys, such as along the Nera river banks, and in the Apennine Mountains, such as in Gavelli, Monteleone di Spoleto, and Castelluccio di Norcia, with the plant being able to survive elevations of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) a.s.l., at the highest. Moreover, following several land reclamation projects carried out between 1561 and 1562 in the swampy areas between the comuni of Foligno, Trevi, Montefalco, and Bevagna, under Francesco Jacobilli, and in 1588 in the swamp of Colfiorito, vast sections of the newly recovered fertile farm land were turned into hemp fields, which resulted in a significant increase in the local hemp production already in 1563. Most of these reclaimed lands belonged to the Jacobilli noble family, who leased them to other noble families, and these families then subleased them to the eventual farmers, who would then grow hemp and wheat on a rotational basis, switching their crops every two or three years. The legacy of the cultivation and processing of industrial cannabis is attested in the traditional tools, toponyms, and even nursery rhymes, that can still be found in the area around Foligno.

Conversely, in the Marches, hemp fields were less common in the countryside, with the exception of the elevated valleys of the Potenza and Chienti rivers, although they steadily increased during the 18th century around Ascoli Piceno and the Tronto river valley, to accommodate the contemporary population and economic growths. In particular, besides the increased needs of the general population, the higher demand for hemp was also prompted by the expanding maritime trade and fishery sectors in the nearby Adriatic coast, as well as the establishment of the free port of Ancona in 1732. Moreover, another noteworthy center for the production of ropes and fishing nets in the Papal States was located in San Benedetto del Tronto, where ropemakers used hemp grown in Ferrara, Ascoli Piceno, as well as other cultivation centers in Romagna.

In the territory of Bologna, which firmly returned under Papal rule in the early 16th century, the cultivation of cannabis increased significantly between the 14th and 17th centuries, with the development of new production techniques that remained in use until the 19th century. Starting from farm lands located between the comuni of Bologna, Budrio, and Cento, the mass cultivation of cannabis spread to large parts of Emilia and Romagna, particularly around the cities of Bologna, Ferrara, Modena, Rovigo, Ravenna, and Cesena. Initially sustained by the demand for hemp fiber from the Venetian Arsenal, as well as from local customers, in the 17th century producers in Bologna started exporting hemp to shipyards in Northwestern Europe, where it was used for the manufacture of ropes and sails. The importance of hemp cultivation in the region is attested in the 1741 poem Il Canapajo, in which Ferrarese presbyter and scholar Girolamo Baruffaldi pays close attention to the agronomic aspects of its cultivation. The last boost in the local production of industrial cannabis occurred during the 19th century, particularly after 1870, with significant applications in the industrial sector.

Dew retting and water retting

During the Middle Ages, the use of hemp fiber in the Padan plain followed a self-sufficiency model, in which the limited production simply aimed at meeting the needs of local families; and the maceration of hemp stalks consisted in their repeated exposure to night-dew on grassy meadows, which was favored by the rainier conditions that characterized the 13th and 14th centuries. From the early 16th century onwards, the use of dedicated water retting tanks became more common with the establishment of hemp as a valuable crop in the fields of Bologna and Modena, and the indroduction of the mezzadria farming system. At the same time, the manufacturing and trade of products derived from hemp fiber underwent a significant expansion, especially in the area of Bologna, with the establishment of local guilds of scutchers, ropemakers, and drapers. As an indication of the historical ubiquity of the aforementioned water basins in the Po river valley, a 2019 survey of the Province of Ferrara revealed the presence of 1,907 surviving water retting tanks averaging 1,066 m (0.26 acres) in area each, based on digital cartography and aerial photos, which resulted in an average density of 0.72 tanks/km (1.86 tanks/sq mi).

In the areas around Foligno and Ascoli Piceno, city laws sometimes dating back to 14th century statutes and subsequently updated up until the 18th century, banned maceration sites both inside and outside city walls for public health reasons based on the miasma theory, similarly to the regulations implemented in southern Italy. Elsewhere in the Papal States, the miasms produced by the maceration of both hemp and flax had already prompted the authorities of Viterbo in 1278 to pledge to move the processing sites away from the populated areas, in order to encourage Pope Nicholas III to move the Roman Curia back to the city. As a notable example of historical health scare, after outbreaks of epidemic fever occurred in Imola in 1599 and 1602, a connection between the fevers and the miasms emanating from the maceration sites was argued in the De morbis qui Imolae et alibi communiter vagati sunt commentariolum by doctor Giovan Battista Codronchi, who successfully campaigned for the removal of these sites from the local area. Despite the health-related restrictions, however, the hemp industry was so widespread that the water retting was still carried out almost everywhere, even within urban centers; while several other laws regulated the production of hemp fiber and ropes, to ensure high-quality products.

In the bassa Padana (i.e. the lower Po river valley), the maceration tanks were often excavated in the most depressed areas of the farms, in order to facilitate the collection of rainwater through drains, and they were normally used by multiple families. Furthermore, the tanks were also used to draw water for the vegetable gardens, to bathe whole families during the summer, to do their laundries, as well as to farm fish and to raise geese and ducklings. At present, the remains of the surviving maceri are protected by strict regulations and some of these basins are occasionally used by former canapai (i.e. hemp workers) to macerate hemp for educational purposes. Historical retting tanks can also be requalified, such as a former macero in the comune of Nonantola that was turned into a refuge for reptiles and amphibians in 2012, in order to increase the local biodiversity.

Cannabis consumption

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, several recipe books were published that included the contemporary culinary uses of cannabis; for instance, the Epulario by Giovanni de Roselli describes a recipe to make twelve soups of hemp seeds with meat. In the 17th century treatise L'economia del cittadino in villa, Bolognese agronomist and gastronome Vincenzo Tanara further describes a particular sauce made using hemp seeds, to be served with boiled meat, which could be either turkey, chicken, or beef. At the time, the high nutritional value of hemp seeds was well known, and they could still be used to produce bread during droughts, when wheat was scarce. The botanical aspects, different uses, qualities, and contraindications of cannabis plants were also described by Perugian physician and botanist Castore Durante in his Herbario Novo, a compendium on medicinal plants from Europe, the East Indies, and the West Indies.

In regard to the recreational use of cannabis, it has been suggested that Pope Innocent VIII outright banned the drug with his 1484 anti-witchcraft bull Summis desiderantes affectibus, to prevent the celebration of black masses. However, neither the plant nor its use appear to be explicitly mentioned in either the 1484 bull or the Malleus Maleficarum, a 1486 treatise on the prosecution of witches, in which the papal bull appears as a preface. Nevertheless, as the bull specifically mentions people falling prey to incantations, spells, conjurations, and other accursed charms and crafts, recreational cannabis could have still been banned possibly due to its mind-altering effects being seen at the time either as the external action of supernatural entities, or as a sign of spiritual corruption. To the present day, the Catechism of the Catholic Church considers the use of drugs outside of strictly therapeutic purposes as a grave offense in violation of the Fifth Commandment, since they inflict grave damage on human health and life. Moreover, the illegal production and trafficking of drugs are considered to be a direct co-operation in evil, since they encourage people to practices gravely contrary to the moral law.

Republic of Genoa

In Europa altra carta non s'adopra che quella de' Genovesi.

Note. Statement on the importance of paper production in the Republic of Genoa, meaning In Europe no other paper is used than that of the Genoese, made by merchants addressing the Genoese Senate in 1567.

The production of paper in the Republic of Genoa began in the early 15th century along the Leira river valley to the west of Genoa, which was favored by the presence of several torrents that could provide power to the numerous paper mills. In particular, papermaker Grazioso Damiani left Fabriano in 1406 and moved first to Sampierdarena and then to Voltri, where he opened his workshop. In 1424, Damiani lamented to the Council of Elders of Genoa the difficulty and high costs in sourcing the raw fiber for paper production (e.g. from ropes and rags), and thus requested and obtained exclusive rights to Genoese cordage for at least five years. In the following centuries, the expanding paper industry became significantly profitable in the Leira and Cerusa river valleys. In particular, the areas of Voltri and Mele became well renowned internationally during the 16th century for the quality and durability of their bookworm-resistant paper, which was especially sought-after by the Royal Chanceries of Spain, Portugal, and England.

Paper production

Tutte e strasse van a Ütri.

Note. Old Ligurian saying on the monopoly on raw materials for paper production in Voltri, following the plea by papermaker Damiani, meaning All the rags go to Voltri.

The Republic of Genova was particularly protectionist in regard to its paper industry, in particular it forbade master craftsmen to emigrate, thus safeguarding its trade secrets; and made the export of any type of rag or papermaking tool illegal, thus ensuring the supply of essential raw materials and equipments. The punishment for violating such restrictions could range from paying heavy fines to becoming a galley slave in the Genoese navy. By the second half of the 16th century, around 50 papeterie (i.e. paper mills) were established in Voltri alone, with their number peaking by the 1700s at around 150 paper mills spread between Voltri, Mele, Arenzano, and Varazze. This made the Republic of Genoa the main hub in Europe for paper production between the 16th and 18th centuries, although other important centers also began to emerge in the same period in Piedmont, Venetia, Tuscany, France, Germany, Holland, and England.

For several centuries, the sheets of paper were individually produced from rags made from textile fibers such as hemp, flax, and cotton; which were sourced from either Piedmont, Lombardy, or other locations overseas. From the 19th century onwards, the development of continuous paper making machines, combined with the use of cellulose obtained from coniferous or broad-leaved wood, led to an increase in paper production, albeit at the expense of its quality. The decline of papermaking in the Duchy of Genoa came with the introduction of the steam engine during the Industrial Revolution, which made watermills redundant and the impervious Genoese valleys unpractical as factory locations. In the post-war period, almost all of the 43 remaining paper mills along the Leira river valley closed down within a couple of decades, with only two currently remaining in the comune of Mele. One of the two factories utilizes machinery for industrial production, while the other still applies traditional techniques as part of the Paper Museum of Mele.

Duchy of Milan

One of the oldest trade guilds in the Duchy of Milan was the Università dei Merzari (a.k.a. Merciai), which was founded in the town of Paratico on 15 September 1489 by decree of Duke Ludovico Sforza, and became the Università dei Merzari et Cordari in 1560 under King Philip II of Spain. In 1582, the Università dei Mercanti di Cordaria e Canevazzi (i.e. Corporation of Merchants of Ropes and Rags), which used hemp fibers to produce several types of ropes and textiles for different uses, split from the aforementioned guild over significant internal disputes between the merzari and the cordari. The activities of these guilds continued in the Duchy for several centuries until the suppression of the Corporazioni d'Arte e Mestieri (i.e. Corporations of Arts and Crafts), by decree of Emperor Joseph II, on 4 March 1787.

Hemp rope production

A renowned historical center for the production of hemp ropes in the Duchy of Milan was in the village of Castelponzone, which is now a frazione of the comune of Scandolara Ravara. As attested by its name, the fortified medieval hamlet was strongly connected to the Ponzone family from nearby Cremona, ever since Ponzino Ponzone acquired it and reconstructed the pre-existing local stronghold in the early 14th century; and its importance grew after Duke Filippo Maria Visconti granted the land as a fief to Galeazzo Ponzone in 1416. Afterwards, the Counts hired ropemakers from Tuscany to train local workers, and their trade became the main productive activity of the area for centuries, initially using hemp locally grown and processed, while later sourcing it from major production centers, such as Modena and Ferrara. From the preparation of the hemp fiber to the final polishing of the rope, the various stages of the production involved the entire family of a ropemaker, both adults and children, with the latter for instance usually being given the task of spinning the wheel at a regular rate. The types of locally produced ropes ranged from those commonly used for farming activities to the thicker hawsers and shrouds used in large ships, and over time these ropes were being sold in various Regions of Italy and even exported to Russia, France, Spain, and Germany. Most notably, ropes form Castelponzone were used for the rigging of the SS Rex, which was launched in 1931; while anecdotal accounts from locals report on an order from the Imperial Russian Navy that required the combined effort of twelve ropemakers to fulfill, and included the production of a 120 m (390 ft) long and 400 kg (880 lb) heavy rope.

The production of hemp ropes remained high throughout the 19th century, albeit with alternating phases, while the introduction of semi-automated systems around 1930 and the use of electricity made the work easier, when compared to the traditional process. Nevertheless, the local sector began to decline during the 20th century due to the reduced demand caused by the expansion of steam-powered vessels and the competition from cheaper natural fibers (e.g. cotton, jute, abacá, and Manila hemp), despite the adjustments that were attempted by switching from hemp to imported fibers such as sisal and Manila. During the interwar period, hemp was sourced from Bologna, Ferrara, and Rovigo, and then processed by the ropemakers, who then sold the produced ropes on a piece rate basis according to their weight, with the larger family businesses producing the thickest ropes for the Navy. The introduction of synthetic fibers (e.g. rayon and nylon), the extended use of manual labor due to low mechanization, and the competition from more profitable crops (e.g. sugar beet, specialized orchards, and other horticultural crops) eventually caused the centuries-old local activity to disappear. The legacy of the once-flourishing industry is attested by the Museum of the Ropemakers in Castelponzone, which includes a complete collection of traditional tools used in different periods to manufacture ropes, as well as a vast collection of ropes, ranging from those used for horse harnesses to heavier ropes intended for either agricultural work or seafaring.

Cannabis consumption

In 2023, researchers from the University of Milan and the Policlinico of Milan published a scientific research paper on the analytical evidence of the use of cannabis plants in Milan, for either medical or recreational purposes, during the 17th century. In particular, out of the nine femoral bone samples that were studied, archaeotoxicological analyses revealed the presence of both Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol in those belonging to a 45–54 years old female and a 16–20 years old male, in what is reportedly the first physical evidence of cannabis use during the Modern Age, both in Italy and in Europe.

The biological samples were recovered from the crypt of the Ospedale Maggiore di Milano, in a section of the church of the hospital that was used to bury the deceased patients from 1638 to 1697; therefore, the studied individuals lived in the context of a severe social decline brought about by the Great Plague of Milan, which almost halved the city population between 1629 and 1631. The absence of references to cannabis in the pharmacopoeia present in the archives suggests that the plant was not being administered as medical treatment by the hospital at the time, while other possible explanations for the presence of the two cannabinoids include recreational use, self-medication, administration by doctors in other medical facilities, as well as occupational and involuntary exposure.

Grand Duchy of Tuscany

So di che poco canape s'allaccia

Un'anima gentil, quand'ella è sola,

E non è chi per lei difesa faccia.

Note. Tercet from the Triumph of Love by Petrarch, on how easily a lonely soul can be conquered, meaning I know how little hemp can bind : A gentle soul, when she's alone, : And no one is there to defend her.

In Italian poetry, references to hemp ropes can be found in several original works, including the series of poems I Trionfi, written between 1351 and 1374 by Aretine scholar and poet Francesco Petrarca; and the romance epic Orlando Furioso, written in 1516 by Reggian poet Ludovico Ariosto; as well as translated works, such as the Ancient greek Oppian poem On fishing and hunting, as translated and illustrated by Florentine naturalist and classicist Anton Maria Salvini in the 17th century. Further references to the processing of hemp can be found in the epic poem Divina Commedia, written between around 1308 and 1321 by Florentine writer and philosopher Dante Alighieri; in particular, the sinners-chewing mouths of the three-headed Lucifer are compared in Canto XXXIV of the Inferno to the maciulla (a.k.a. gràmola), a traditional tool used to break both hemp and flax. A second, less-widely accepted, reference in the earlier Canto XIV reportedly alludes to the maceration of hemp at the Bulicame thermal springs near Viterbo, when the Poet mentions the peccatrici (i.e. sinners) sharing its waters. According to this interpretation, the term would actually refer to pecsatrici or pezzatrici (i.e. hemp maceration workers); however, at the time such activities in the area around Viterbo would have taken place within dedicated piscine (i.e. water retting tanks) under the supervision of a piscinarius, who was either the owner or the tenant of one or more piscine made available for a fee.

Hemp in traditional sports

Il canapo è unto con l'argento.

Note. Old Tuscan proverb on how money facilitates things (i.e. it makes the metaphorical rope run smoothly), meaning The hemp rope is greased with silver.

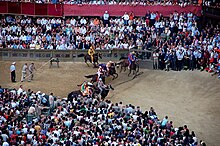

In Siena, the centuries-old Palio horse race uses a 14 m (45.9 ft) long, 4 cm (1.57 in) thick, and 15 kg (33.1 lb) heavy, traditional hemp rope known as the canape, as the starting line for the horses from nine of the participating contrade. The rope is kept stretched at a height of 80 cm (31.5 in) using a winch exerting a force equivalent to 2,000 kg (4,409 lb), and the mossiere suddenly releases it by pressing the Pedal of Verrocchio, thus starting the race. The cue for the release consists in the horse from the tenth participating contrada, known as the rincorsa (i.e. the run-up), crossing a second 12 m (39.4 ft) long and 3 cm (1.18 in) thick canape placed a few meters back, marking the rear of the starting area.

Hemp strings are also traditionally used to sew together the approximately 22 cm (8.66 in) wide and 500 g (1.1 lb) heavy ball used in the calcio storico fiorentino, which is an early form of football that originated during the Middle Ages in Italy. In particular, the thick leather covering consists of four longitudinal slices alternately vernished with the colors of Florence (i.e. white and red), and made of eight triangular sections that are manually sewn together using hemp strings, while multiple internal layers of canvas make the ball as non-deformable as possible.

Elsewhere in Italy, in the Marches, the ten contrade of Fermo participate in the traditional Tiro al Canapo competition, as part of a medieval fair that culminates in the Cavalcata dell'Assunta horse race, which takes place every year on 15 August since it was reinstated in 1982. Dating back to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and elevated to an Olympic sport from 1900 to 1920, rope pulling competitions in Italy experienced a resurgence during local festivals in the Marches countryside in the 1950s. In fact, the Tiro al Canapo is the oldest traditional game occurring at the fair of Fermo, with the first edition taking place in 1986, while the other games include archery, flag throwing, and drum performances. During the rope pulling tournament, the ten contrade are divided in two all-play-all groups whose victors then face off in the final match, with each team consisting in six players on the platform, whose combined weight cannot exceed 551 kg (1,215 lb), and five substitute players. The number of players increases to eight for the modern-day sport, with total weight limits between 600 kg (1,323 lb) and 720 kg (1,587 lb), and the two teams pull on a 36 m (118.1 ft) long hemp rope having a diameter that ranges between 10 cm (3.94 in) and 12 cm (4.72 in).

Kingdom of Piedmont–Sardinia

Se il fil di canapa è marcio, non s'avrà mai corda buona.

Note. Excerpt written by Piedmontese-Italian statesman Massimo d'Azeglio meaning If the hemp thread is rotten, you will never have a good rope, as part of a larger statement on the need to improve the individual to build a better nation.

The introduction of hemp plants in Piedmont is generally attributed to the arrival of Roman legions in what was then Cisalpine Gaul, in the 3rd century B.C., with the earliest cultivations being located in the area around modern-day Carmagnola, since it was rich in water without being swampy. Other sources date the introduction of hemp into the region to the 10th century, or alternatively its possible reintroduction, considering the severe disruption in cannabis cultivation across the entire Italian peninsula following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Still other sources report that hemp cultivation was fairly common in 600 A.D. in the area that is now the frazione of Casanova, and then it spread to the larger area around Carmagnola, and finally to the historical region of Canavese, which reportedly derives its name from the plant. In fact, the importance of cannabis cultivation in said region is attested by the fact that on weapons, on shields, on imprese, on charters, and on the blazons of the first counts, the tender little plant appeared as a symbol almost attesting their origin to be as one with that of the region; while the comuni of Barone Canavese, Borgomasino, and Prascorsano still show a hemp plant in their coats of arms.

In any case, the cultivation of hemp spread to the entire Padan plain during the Middle Ages, in particular during the 11th century, while a major boost to the production of hemp in Carmagnola was given by the foundation of the Abbey of Santa Maria di Casanova, between 1127 and 1150, after a land donation made by the Marquis of Saluzzo to the Cistercians. Several documents from the 12th and 13th centuries attest the cultivation and processing of hemp in the area, in particular with the monks working on expanding and improving their crops, which grew to cover several hectares. The extent of the cultivations was such that a grangian monk was specifically appointed to direct the work on the fields, and he needed to be dispensed from performing any other cloistered duty. In addition, specific provisions were issued by Thomas II of Savoy during the 13th century, which promoted the spread of hemp cultivation in the region; and by the 14th century, hemp fields in Piedmont covered a large area between the comuni of Cavour, Cercenasco, La Loggia, Moretta, and Racconigi. Furthermore, Carmagnola became an important trading center for hemp fiber and seeds under the Marquisate of Saluzzo, so much so that in 1300 its hemp was subjected to both civil taxes and ecclesiastical tithes; and by the second half of the 16th century it was the main center for all of Piedmont. In particular, the Carmagnola hemp variety was exported to the rest of the Italian states, as well as to France, and the town itself acquired over the centuries the title of Empire of Hemp.

Hemp textile production