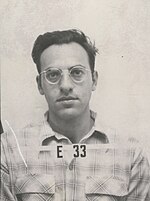

| Frederick Reines | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1918-03-16)March 16, 1918 Paterson, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | August 26, 1998(1998-08-26) (aged 80) Orange, California, U.S. |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | New York University Stevens Institute of Technology |

| Known for | Neutrinos |

| Spouse | Sylvia Samuels (m. 1940; 2 children) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Nuclear fission and the liquid drop model of the nucleus (1944) |

| Doctoral advisor | Richard D. Present |

| Doctoral students | Michael K. Moe (1965) |

Frederick Reines (/ˈraɪnəs/ RY-nəs; March 16, 1918 – August 26, 1998) was an American physicist. He was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physics for his co-detection of the neutrino with Clyde Cowan in the neutrino experiment. He may be the only scientist in history "so intimately associated with the discovery of an elementary particle and the subsequent thorough investigation of its fundamental properties."

A graduate of Stevens Institute of Technology and New York University, Reines joined the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory in 1944, working in the Theoretical Division in Richard Feynman's group. He became a group leader there in 1946. He participated in a number of nuclear tests, culminating in his becoming the director of the Operation Greenhouse test series in the Pacific in 1951.

In the early 1950s, working in Hanford and Savannah River Sites, Reines and Cowan developed the equipment and procedures with which they first detected the supposedly undetectable neutrinos in June 1956. Reines dedicated the major part of his career to the study of the neutrino's properties and interactions, which work would influence study of the neutrino for many researchers to come. This included the detection of neutrinos created in the atmosphere by cosmic rays, and the 1987 detection of neutrinos emitted from Supernova SN1987A, which inaugurated the field of neutrino astronomy.

Early life

Frederick Reines was born in Paterson, New Jersey, one of four children of Gussie (Cohen) and Israel Reines. His parents were Jewish emigrants from the same town in Russia, but only met in New York City, where they were later married. He had an older sister, Paula, who became a doctor, and two older brothers, David and William, who became lawyers. He said that his "early education was strongly influenced" by his studious siblings. He was the great-nephew of the Rabbi Yitzchak Yaacov Reines, the founder of Mizrachi, a religious Zionist movement.

The family moved to Hillburn, New York, where his father ran the general store, and he spent much of his childhood. He was an Eagle Scout. Looking back, Reines said: "My early childhood memories center around this typical American country store and life in a small American town, including Independence Day July celebrations marked by fireworks and patriotic music played from a pavilion bandstand."

Reines sang in a chorus, and as a soloist. For a time he considered the possibility of a singing career, and was instructed by a vocal coach from the Metropolitan Opera who provided lessons for free because the family did not have the money for them. The family later moved to North Bergen, New Jersey, residing on Kennedy Boulevard and 57th Street. Because North Bergen did not have a high school, he attended Union Hill High School in Union Hill, New Jersey (today Union City, New Jersey), from which he graduated in 1935.

From an early age, Reines exhibited an interest in science, and liked creating and building things. He later recalled that:

The first stirrings of interest in science that I remember occurred during a moment of boredom at religious school, when, looking out of the window at twilight through a hand curled to simulate a telescope, I noticed something peculiar about the light; it was the phenomenon of diffraction. That began for me a fascination with light.

Ironically, Reines excelled in literary and history courses, but received average or low marks in science and math in his freshman year of high school, though he improved in those areas by his junior and senior years through the encouragement of a teacher who gave him a key to the school laboratory. This cultivated a love of science by his senior year. In response to a question seniors were asked about what they wanted to do for a yearbook quote, he responded: "To be a physicist extraordinaire."

Reines was accepted into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but chose instead to attend Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, where he earned his Bachelor of Science (B.S.) degree in mechanical engineering in 1939, and his Master of Science (M.S.) degree in mathematical physics in 1941, writing a thesis on "A Critical Review of Optical Diffraction Theory". He married Sylvia Samuels on August 30, 1940. They had two children, Robert and Alisa. He then entered New York University, where he earned his Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in 1944. He studied cosmic rays there under Serge A. Korff, but wrote his thesis under the supervision of Richard D. Present on "Nuclear fission and the liquid drop model of the nucleus". Publication of the thesis was delayed until after the end of World War II; it appeared in Physical Review in 1946.

Los Alamos Laboratory

In 1944 Richard Feynman recruited Reines to work in the Theoretical Division at the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory, where he would remain for the next fifteen years. He joined Feynman's T-4 (Diffusion Problems) Group, which was part of Hans Bethe's T (Theoretical) Division. Diffusion was an important aspect of critical mass calculations. In June 1946, he became a group leader, heading the T-1 (Theory of Dragon) Group. An outgrowth of the "tickling the Dragon's tail" experiment, the Dragon was a machine that could attain a critical state for short bursts of time, which could be used as a research tool or power source.

Reines participated in a number of nuclear tests, and writing reports on their results. These included Operation Crossroads at Bikini Atoll in 1946, Operation Sandstone at Eniwetok Atoll in 1948, and Operation Ranger and Operation Buster–Jangle at the Nevada Test Site. In 1951 he was the director of Operation Greenhouse series of nuclear tests in the Pacific. This saw the first American tests of boosted fission weapons, an important step towards thermonuclear weapons. He studied the effects of nuclear blasts, and co-authored a paper with John von Neumann on Mach stem formation, an important aspect of an air blast wave.

In spite or perhaps because of his role in these nuclear tests, Reines was concerned about the dangers of radioactive pollution from atmospheric nuclear tests, and became an advocate of underground nuclear testing. In the wake of the Sputnik crisis, he participated in John Archibald Wheeler's Project 137, which evolved into JASON. He was also a delegate at the Atoms for Peace Conference in Geneva in 1958.

Discovery of the neutrino and the inner workings of stars

The neutrino is a subatomic particle first proposed by Wolfgang Pauli on December 4, 1930. The particle was required to resolve the problem of missing energy in observations of beta decay, when a neutron decays into a proton and an electron. The new hypothetical particle was required to preserve the fundamental law of conservation of energy. Enrico Fermi renamed it the neutrino, Italian for "little neutral one", and in 1934, proposed his theory of beta decay by which the electrons emitted from the nucleus were created by the decay of a neutron into a proton, an electron, and a neutrino:

n

→

p

+

e

+

ν

e

The neutrino accounted for the missing energy, but Fermi's theory described a particle with little mass and no electric charge that appeared to be impossible to observe directly. In a 1934 paper, Rudolf Peierls and Hans Bethe calculated that neutrinos could easily pass through the Earth, and concluded "there is no practically possible way of observing the neutrino."

In 1951, Reines and his colleague Clyde Cowan decided to see if they could detect neutrinos and so prove their existence. At the conclusion of the Greenhouse test series, Reines had received permission from the head of T Division, J. Carson Mark, for a leave in residence to study fundamental physics. "So why did we want to detect the free neutrino?" he later explained, "Because everybody said, you couldn't do it."

According to Fermi's theory, there was also a corresponding reverse reaction, in which a neutrino combines with a proton to create a neutron and a positron:

ν

e +

p

→

n

+

e

The positron would soon be annihilated by an electron and produce two 0.51 MeV gamma rays, while the neutron would be captured by a proton and release a 2.2 MeV gamma ray. This would produce a distinctive signature that could be detected. They then realised that by adding cadmium salt to their liquid scintillator they would enhance the neutron capture reaction, resulting in a burst of gamma rays with a total energy of 9 MeV. For a neutrino source, they proposed using an atomic bomb. Permission for this was obtained from the laboratory director, Norris Bradbury. The plan was to detonate a "20-kiloton nuclear bomb, comparable to that dropped on Hiroshima, Japan". The detector was proposed to be dropped at the moment of explosion into a hole 40 meters from the detonation site "to catch the flux at its maximum"; it was named "El Monstro". Work began on digging a shaft for the experiment when J. M. B. Kellogg convinced them to use a nuclear reactor instead of a bomb. Although a less intense source of neutrinos, it had the advantage in allowing for multiple experiments to be carried out over a long period of time.

In 1953, they made their first attempts using one of the large reactors at the Hanford nuclear site in what is now known as the Cowan–Reines neutrino experiment; they named the experiment "Project Poltergeist". Their detector included 300 litres (66 imp gal; 79 US gal) of scintillating fluid and 90 photomultiplier tubes, but the effort was frustrated by background noise from cosmic rays. With encouragement from John A. Wheeler, they tried again in 1955, this time using one of the newer, larger 700 MW reactors at the Savannah River Site that emitted a high neutrino flux of 1.2 x 10 / cm sec. They also had a convenient, well-shielded location 11 metres (36 ft) from the reactor and 12 metres (39 ft) underground. On June 14, 1956, they were able to send Pauli a telegram announcing that the neutrino had been found. When Bethe was informed that he had been proven wrong, he said, "Well, you shouldn't believe everything you read in the papers."

From then on Reines dedicated the major part of his career to the study of the neutrino's properties and interactions, which work would influence study of the neutrino for future researchers to come. Cowan left Los Alamos in 1957 to teach at George Washington University, ending their collaboration. On the basis of his work in first detecting the neutrino, Reines became the head of the physics department of Case Western Reserve University from 1959 to 1966. At Case, he led a group that was the first to detect neutrinos created in the atmosphere by cosmic rays. Reines had a booming voice, and had been a singer since childhood. During this time, besides performing his duties as a research supervisor and chairman of the physics department, Reines sang in the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus under the direction of Robert Shaw in performances with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra.

In the early 1960s, Reines built a detector in the East Rand gold mine near Johannesburg, South Africa. The site was chosen because of its depth, 3.5 km; on February 23, 1965, the new detector captured its first atmospheric neutrinos. Reines brought his friends, an engineer August "Gus" Hruschka from the US, they worked together with South African physicist Friedel Sellschop of the University of Witwatersrand. Equipment was made in the Case Institute, and 20 tonnes of scintillation fluid in 50 containment tanks were transported from the US. The decision to work in an apartheid racist country was challenged by many colleagues of Reines, he himself said that "science transcended politics". The laboratory team in the mine was led by Reines' graduate students, first by William Kropp, and then by Henry Sobel. Experiment ran from 1963 and was closed in 1971, and captured 167 neutrino events.

In 1966, Reines took most of his neutrino research team with him when he left for the new University of California, Irvine (UCI), becoming its first dean of physical sciences. At UCI, Reines extended the research interests of some of his graduate students into the development of medical radiation detectors, such as for measuring total radiation delivered to the whole human body in radiation therapy.

Reines had prepared for the possibility of measuring the distant events of a supernova explosion. Supernova explosions are rare, but Reines thought he might be lucky enough to see one in his lifetime, and be able to catch the neutrinos streaming from it in his specially-designed detectors. During his wait for a supernova to explode, he put signs on some of his large neutrino detectors, calling them "Supernova Early Warning Systems". In 1987, neutrinos emitted from Supernova SN1987A were detected by the Irvine–Michigan–Brookhaven (IMB) Collaboration, which used an 8,000 ton Cherenkov detector located in a salt mine near Cleveland. Normally, the detectors recorded only a few background events each day. The supernova registered 19 events in just ten seconds. This discovery is regarded as inaugurating the field of neutrino astronomy.

In 1995 Reines was honored, along with Martin L. Perl, with the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work with Cowan in first detecting the neutrino. Unfortunately, Cowan had died in 1974 and the Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously. Reines also received many other awards, including the J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Prize in 1981, the National Medal of Science in 1985, the Bruno Rossi Prize in 1989, the Michelson–Morley Award in 1990, the Panofsky Prize in 1992, and the Franklin Medal in 1992. He was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1980 and a foreign member of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1994. He remained dean of physical sciences at UCI until 1974, and became a professor emeritus in 1988, but he continued teaching until 1991, and remained on UCI's faculty until his death.

Death

Reines died after a long illness at the University of California, Irvine Medical Center in Orange, California, on August 26, 1998. He was survived by his wife and children. His papers are compiled in the UCI Libraries. Frederick Reines Hall, which houses the Physics and Astronomy Department at the University of California, Irvine, was named in his honor.

Publications

- Reines, F. & C. L. Cowan Jr. "On the Detection of the Free Neutrino", Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) (through predecessor agency Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory), United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission), (August 6, 1953).

- Reines, F., Cowan, C. L. Jr., Carter, R. E., Wagner, J. J. & M. E. Wyman. "The Free Antineutrino Absorption Cross Section. Part I. Measurement of the Free Antineutrino Absorption Cross Section. Part II. Expected Cross Section from Measurements of Fission Fragment Electron Spectrum", Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) (through predecessor agency Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory), United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission), (June 1958).

- Reines, F., Gurr, H. S., Jenkins, T. L. & J. H. Munsee. "Neutrino Experiments at Reactors", University of California-Irvine, Case Western Reserve University, United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Atomic Energy Commission), (September 9, 1968).

- Roberts, A., Blood, H., Learned, J. & F. Reines. "Status and Aims of the DUMAND Neutrino Project: the Ocean as a Neutrino Detector", Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (FNAL), United States Department of Energy (through predecessor agency the Energy Research and Development Administration), (July 1976).

- Reines, F. (1991). Neutrinos and Other Matters: Selected Works of Frederick Reines. Teaneck, N.J.: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-0392-4.

Notes

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (August 28, 1998). "Frederick Reines Dies at 80; Nobelist Discovered Neutrino". The New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ Schultz, Jonas; Sobel, Hank. "Frederick Reines and the Neutrino". University of California, Irvine School of Physical Sciences. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014.

- ^ Kropp, William; Schultz, Jonas; Sobel, Henry (2009). Frederick Reines 1918-1998 A Biographical Memoir (PDF). Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1995". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ Pope, Gennarose (March 25, 2012). "Bridge of troubled Kennedy Boulevard". The Union City Reporter. p. 12.

- "Nuclear fission and the liquid drop model of the nucleus". New York University. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- Present, R. D.; Reines, F.; Knipp, J. K. (October 1946). "The Liquid Drop Model for Nuclear Fission". Physical Review. 70 (7–8): 557–558. Bibcode:1946PhRv...70..557P. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.70.557.2. hdl:2027/mdp.39015086430553. PMID 18880816.

- Truslow & Smith 1961, pp. 56–59.

- Close 2012, pp. 15–18.

- Fermi, E. (1968). "Fermi's Theory of Beta Decay". American Journal of Physics. 36 (12). Wilson, Fred L. (trans.): 1150–1160. Bibcode:1968AmJPh..36.1150W. doi:10.1119/1.1974382. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- Close 2012, pp. 22–25.

- Bethe, H.; Peierls, R. (April 7, 1934). "The Neutrino". Nature. 133 (3362): 532. Bibcode:1934Natur.133..532B. doi:10.1038/133532a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4001646.

- ^ Reines, Frederick (December 8, 1995). "The Neutrino: From Poltergeist to Particle" (PDF). Nobel Foundation. Retrieved August 12, 2024.

Nobel Prize lecture

- ^ Lubkin, Gloria B. (1995). "Nobel Prize in Physics goes to Frederick Reines for the Detection of the Neutrino" (PDF). Physics Today. 48 (12): 17–19. Bibcode:1995PhT....48l..17L. doi:10.1063/1.2808286. ISSN 0031-9228. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 17, 2008.

- ^ Abbott, Alison (May 17, 2021). "The singing neutrino Nobel laureate who nearly bombed Nevada". Nature. 593 (7859): 334–335. Bibcode:2021Natur.593..334A. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01318-y.

- Close 2012, pp. 37–41.

- ^ Close 2012, p. 42.

- ^ "In Memoriam, 1998. Frederick Reines, Physics; Radiological Sciences: Irvine". University of California. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Cole, Leonard A (March 2021). Chasing the Ghost: Nobelist Fred Reines and the Neutrino. pp. 3–13. doi:10.1142/9789811231063_0001. ISBN 978-981-12-3105-6.

- "Frederick Reines wins Oppenheimer Prize". Physics Today. 34 (5): 94. May 1981. Bibcode:1981PhT....34R..94.. doi:10.1063/1.2914589.

- "The Passing of Frederick Reines, Physics Nobel Laureate in 1995". University of California, Irvine. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013.

- "Guide to the Frederick Reines Papers". Retrieved February 18, 2015 – via California Digital Library.

- Benjamin, Marisa. "Frederick Reines Hall at UC Irvine". About.com. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

See also

References

- Close, Frank E. (2012). Neutrino. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199574599. OCLC 840096946.

- Truslow, Edith C.; Smith, Ralph Carlisle (1961). Manhattan District history, Project Y, the Los Alamos story, Volume II: August 1945 to December 1946. Los Angeles: Tomash Publishers. ISBN 978-0-938228-08-0. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

Originally published as Los Alamos Report LAMS-2532

External links

- Guide to the Frederick Reines Papers. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

- Frederick Reines on Nobelprize.org

including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1995 The Neutrino: From Poltergeist to Particle

including the Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1995 The Neutrino: From Poltergeist to Particle

| 1995 Nobel Prize laureates | |

|---|---|

| Chemistry |

|

| Literature (1995) | Seamus Heaney (Ireland) |

| Peace |

|

| Physics |

|

| Physiology or Medicine |

|

| Economic Sciences | Robert Lucas Jr. (United States) |

- 1918 births

- 1998 deaths

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- American Nobel laureates

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- 20th-century American physicists

- Case Western Reserve University faculty

- Jewish American physicists

- National Medal of Science laureates

- New York University Graduate School of Arts and Science alumni

- People from Union City, New Jersey

- Scientists from Paterson, New Jersey

- People from Rockland County, New York

- Stevens Institute of Technology alumni

- Union Hill High School alumni

- University of California, Irvine faculty

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- Winners of the Panofsky Prize

- Manhattan Project people

- Cold War history of the United States

- Scientists from New York (state)

- Recipients of Franklin Medal