- This is about lattice theory. For other similarly named results, see Birkhoff's theorem (disambiguation).

In mathematics, Birkhoff's representation theorem for distributive lattices states that the elements of any finite distributive lattice can be represented as finite sets, in such a way that the lattice operations correspond to unions and intersections of sets. Here, a lattice is an abstract structure with two binary operations, the "meet" and "join" operations, which must obey certain axioms; it is distributive if these two operations obey the distributive law. The union and intersection operations, in a family of sets that is closed under these operations, automatically form a distributive lattice, and Birkhoff's representation theorem states that every finite distributive lattice can be formed in this way. It is named after Garrett Birkhoff, who published a proof of it in 1937.

The theorem can be interpreted as providing a one-to-one correspondence between distributive lattices and partial orders, between quasi-ordinal knowledge spaces and preorders, or between finite topological spaces and preorders.

The name “Birkhoff's representation theorem” has also been applied to two other results of Birkhoff, one from 1935 on the representation of Boolean algebras as families of sets closed under union, intersection, and complement (so-called fields of sets, closely related to the rings of sets used by Birkhoff to represent distributive lattices), and Birkhoff's HSP theorem representing algebras as products of irreducible algebras. Birkhoff's representation theorem has also been called the fundamental theorem for finite distributive lattices.

Background and examples

Many lattices can be defined in such a way that the elements of the lattice are represented by sets, the join operation of the lattice is represented by set union, and the meet operation of the lattice is represented by set intersection. For instance, the Boolean lattice defined from the family of all subsets of a finite set has this property. More generally any finite topological space has a lattice of sets as its family of open sets. Because set unions and intersections obey the distributive law, any lattice defined in this way is a distributive lattice. Birkhoff's theorem states that in fact all finite distributive lattices can be obtained this way, and later generalizations of Birkhoff's theorem state a similar thing for infinite distributive lattices.

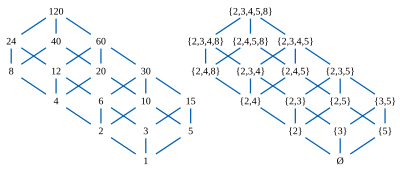

Consider the divisors of some composite number, such as (in the figure) 120, partially ordered by divisibility. Any two divisors of 120, such as 12 and 20, have a unique greatest common factor 12 ∧ 20 = 4, the largest number that divides both of them, and a unique least common multiple 12 ∨ 20 = 60; both of these numbers are also divisors of 120. These two operations ∨ and ∧ satisfy the distributive law, in either of two equivalent forms: (x ∧ y) ∨ z = (x ∨ z) ∧ (y ∨ z) and (x ∨ y) ∧ z = (x ∧ z) ∨ (y ∧ z), for all x, y, and z. Therefore, the divisors form a finite distributive lattice.

One may associate each divisor with the set of prime powers that divide it: thus, 12 is associated with the set {2,3,4}, while 20 is associated with the set {2,4,5}. Then 12 ∧ 20 = 4 is associated with the set {2,3,4} ∩ {2,4,5} = {2,4}, while 12 ∨ 20 = 60 is associated with the set {2,3,4} ∪ {2,4,5} = {2,3,4,5}, so the join and meet operations of the lattice correspond to union and intersection of sets.

The prime powers 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 appearing as elements in these sets may themselves be partially ordered by divisibility; in this smaller partial order, 2 ≤ 4 ≤ 8 and there are no order relations between other pairs. The 16 sets that are associated with divisors of 120 are the lower sets of this smaller partial order, subsets of elements such that if x ≤ y and y belongs to the subset, then x must also belong to the subset. From any lower set L, one can recover the associated divisor by computing the least common multiple of the prime powers in L. Thus, the partial order on the five prime powers 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 carries enough information to recover the entire original 16-element divisibility lattice.

Birkhoff's theorem states that this relation between the operations ∧ and ∨ of the lattice of divisors and the operations ∩ and ∪ of the associated sets of prime powers is not coincidental, and not dependent on the specific properties of prime numbers and divisibility: the elements of any finite distributive lattice may be associated with lower sets of a partial order in the same way.

As another example, consider the lattice of subsets of an n-element set, partially ordered by inclusion. Birkhoff's theorem shows this lattice to be produced by the lower sets of the free distributive lattice on n generators, the number of elements of which is given by the Dedekind numbers.

The partial order of join-irreducibles

In a lattice, an element x is join-irreducible if x is not the join of a finite set of other elements. Equivalently, x is join-irreducible if it is neither the bottom element of the lattice (the join of zero elements) nor the join of any two smaller elements. For instance, in the lattice of divisors of 120, there is no pair of elements whose join is 4, so 4 is join-irreducible. An element x is join-prime if it differs from the bottom element, and whenever x ≤ y ∨ z, either x ≤ y or x ≤ z. In the same lattice, 4 is join-prime: whenever lcm(y,z) is divisible by 4, at least one of y and z must itself be divisible by 4.

In any lattice, a join-prime element must be join-irreducible. Equivalently, an element that is not join-irreducible is not join-prime. For, if an element x is not join-irreducible, there exist smaller y and z such that x = y ∨ z. But then x ≤ y ∨ z, and x is not less than or equal to either y or z, showing that it is not join-prime.

There exist lattices in which the join-prime elements form a proper subset of the join-irreducible elements, but in a distributive lattice the two types of elements coincide. For, suppose that x is join-irreducible, and that x ≤ y ∨ z. This inequality is equivalent to the statement that x = x ∧ (y ∨ z), and by the distributive law x = (x ∧ y) ∨ (x ∧ z). But since x is join-irreducible, at least one of the two terms in this join must be x itself, showing that either x = x ∧ y (equivalently x ≤ y) or x = x ∧ z (equivalently x ≤ z).

The lattice ordering on the subset of join-irreducible elements forms a partial order; Birkhoff's theorem states that the lattice itself can be recovered from the lower sets of this partial order.

Birkhoff's theorem

In any partial order, the lower sets form a lattice in which the lattice's partial ordering is given by set inclusion, the join operation corresponds to set union, and the meet operation corresponds to set intersection, because unions and intersections preserve the property of being a lower set. Because set unions and intersections obey the distributive law, this is a distributive lattice. Birkhoff's theorem states that any finite distributive lattice can be constructed in this way.

- Theorem. Any finite distributive lattice L is isomorphic to the lattice of lower sets of the partial order of the join-irreducible elements of L.

That is, there is a one-to-one order-preserving correspondence between elements of L and lower sets of the partial order. The lower set corresponding to an element x of L is simply the set of join-irreducible elements of L that are less than or equal to x, and the element of L corresponding to a lower set S of join-irreducible elements is the join of S.

For any lower set S of join-irreducible elements, let x be the join of S, and let T be the lower set of the join-irreducible elements less than or equal to x. Then S = T. For, every element of S clearly belongs to T, and any join-irreducible element less than or equal to x must (by join-primality) be less than or equal to one of the members of S, and therefore must (by the assumption that S is a lower set) belong to S itself. Conversely, for any element x of L, let S be the join-irreducible elements less than or equal to x, and let y be the join of S. Then x = y. For, as a join of elements less than or equal to x, y can be no greater than x itself, but if x is join-irreducible then x belongs to S while if x is the join of two or more join-irreducible items then they must again belong to S, so y ≥ x. Therefore, the correspondence is one-to-one and the theorem is proved.

Rings of sets and preorders

Birkhoff (1937) defined a ring of sets to be a family of sets that is closed under the operations of set unions and set intersections; later, motivated by applications in mathematical psychology, Doignon & Falmagne (1999) called the same structure a quasi-ordinal knowledge space. If the sets in a ring of sets are ordered by inclusion, they form a distributive lattice. The elements of the sets may be given a preorder in which x ≤ y whenever some set in the ring contains x but not y. The ring of sets itself is then the family of lower sets of this preorder, and any preorder gives rise to a ring of sets in this way.

Functoriality

Birkhoff's theorem, as stated above, is a correspondence between individual partial orders and distributive lattices. However, it can also be extended to a correspondence between order-preserving functions of partial orders and bounded homomorphisms of the corresponding distributive lattices. The direction of these maps is reversed in this correspondence.

Let 2 denote the partial order on the two-element set {0, 1}, with the order relation 0 < 1, and (following Stanley) let J(P) denote the distributive lattice of lower sets of a finite partial order P. Then the elements of J(P) correspond one-for-one to the order-preserving functions from P to 2. For, if ƒ is such a function, ƒ(0) forms a lower set, and conversely if L is a lower set one may define an order-preserving function ƒL that maps L to 0 and that maps the remaining elements of P to 1. If g is any order-preserving function from Q to P, one may define a function g* from J(P) to J(Q) that uses the composition of functions to map any element L of J(P) to ƒL ∘ g. This composite function maps Q to 2 and therefore corresponds to an element g*(L) = (ƒL ∘ g)(0) of J(Q). Further, for any x and y in J(P), g*(x ∧ y) = g*(x) ∧ g*(y) (an element of Q is mapped by g to the lower set x ∩ y if and only if belongs both to the set of elements mapped to x and the set of elements mapped to y) and symmetrically g*(x ∨ y) = g*(x) ∨ g*(y). Additionally, the bottom element of J(P) (the function that maps all elements of P to 0) is mapped by g* to the bottom element of J(Q), and the top element of J(P) is mapped by g* to the top element of J(Q). That is, g* is a homomorphism of bounded lattices.

However, the elements of P themselves correspond one-for-one with bounded lattice homomorphisms from J(P) to 2. For, if x is any element of P, one may define a bounded lattice homomorphism jx that maps all lower sets containing x to 1 and all other lower sets to 0. And, for any lattice homomorphism from J(P) to 2, the elements of J(P) that are mapped to 1 must have a unique minimal element x (the meet of all elements mapped to 1), which must be join-irreducible (it cannot be the join of any set of elements mapped to 0), so every lattice homomorphism has the form jx for some x. Again, from any bounded lattice homomorphism h from J(P) to J(Q) one may use composition of functions to define an order-preserving map h* from Q to P. It may be verified that g** = g for any order-preserving map g from Q to P and that and h** = h for any bounded lattice homomorphism h from J(P) to J(Q).

In category theoretic terminology, J is a contravariant hom-functor J = Hom(—,2) that defines a duality of categories between, on the one hand, the category of finite partial orders and order-preserving maps, and on the other hand the category of finite distributive lattices and bounded lattice homomorphisms.

Generalizations

Infinite distributive lattices

In an infinite distributive lattice, it may not be the case that the lower sets of the join-irreducible elements are in one-to-one correspondence with lattice elements. Indeed, there may be no join-irreducibles at all. This happens, for instance, in the lattice of all natural numbers, ordered with the reverse of the usual divisibility ordering (so x ≤ y when y divides x): any number x can be expressed as the join of numbers xp and xq where p and q are distinct prime numbers. However, elements in infinite distributive lattices may still be represented as sets via Stone's representation theorem for distributive lattices, a form of Stone duality in which each lattice element corresponds to a compact open set in a certain topological space. This generalized representation theorem can be expressed as a category-theoretic duality between distributive lattices and spectral spaces (sometimes called coherent spaces, but not the same as the coherent spaces in linear logic), topological spaces in which the compact open sets are closed under intersection and form a base for the topology. Hilary Priestley showed that Stone's representation theorem could be interpreted as an extension of the idea of representing lattice elements by lower sets of a partial order, using Nachbin's idea of ordered topological spaces. Stone spaces with an additional partial order linked with the topology via Priestley separation axiom can also be used to represent bounded distributive lattices. Such spaces are known as Priestley spaces. Further, certain bitopological spaces, namely pairwise Stone spaces, generalize Stone's original approach by utilizing two topologies on a set to represent an abstract distributive lattice. Thus, Birkhoff's representation theorem extends to the case of infinite (bounded) distributive lattices in at least three different ways, summed up in duality theory for distributive lattices.

Median algebras and related graphs

Birkhoff's representation theorem may also be generalized to finite structures other than distributive lattices. In a distributive lattice, the self-dual median operation

gives rise to a median algebra, and the covering relation of the lattice forms a median graph. Finite median algebras and median graphs have a dual structure as the set of solutions of a 2-satisfiability instance; Barthélemy & Constantin (1993) formulate this structure equivalently as the family of initial stable sets in a mixed graph. For a distributive lattice, the corresponding mixed graph has no undirected edges, and the initial stable sets are just the lower sets of the transitive closure of the graph. Equivalently, for a distributive lattice, the implication graph of the 2-satisfiability instance can be partitioned into two connected components, one on the positive variables of the instance and the other on the negative variables; the transitive closure of the positive component is the underlying partial order of the distributive lattice.

Finite join-distributive lattices and matroids

Another result analogous to Birkhoff's representation theorem, but applying to a broader class of lattices, is the theorem of Edelman (1980) that any finite join-distributive lattice may be represented as an antimatroid, a family of sets closed under unions but in which closure under intersections has been replaced by the property that each nonempty set has a removable element.

See also

- Lattice of stable matchings, also representing every finite distributive lattice

Notes

- Birkhoff (1937).

- ^ Stanley (1997).

- Johnstone (1982).

- Birkhoff & Kiss (1947).

- A minor difference between the 2-SAT and initial stable set formulations is that the latter presupposes the choice of a fixed base point from the median graph that corresponds to the empty initial stable set.

References

- Barthélemy, J.-P.; Constantin, J. (1993), "Median graphs, parallelism and posets", Discrete Mathematics, 111 (1–3): 49–63, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(93)90140-O.

- Birkhoff, Garrett (1937), "Rings of sets", Duke Mathematical Journal, 3 (3): 443–454, doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-37-00334-X.

- Birkhoff, Garrett; Kiss, S. A. (1947), "A ternary operation in distributive lattices", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 53 (1): 749–752, doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1947-08864-9, MR 0021540.

- Doignon, J.-P.; Falmagne, J.-Cl. (1999), Knowledge Spaces, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-64501-2.

- Edelman, Paul H. (1980), "Meet-distributive lattices and the anti-exchange closure", Algebra Universalis, 10 (1): 290–299, doi:10.1007/BF02482912.

- Johnstone, Peter (1982), "II.3 Coherent locales", Stone Spaces, Cambridge University Press, pp. 62–69, ISBN 978-0-521-33779-3.

- Priestley, H. A. (1970), "Representation of distributive lattices by means of ordered Stone spaces", Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 2 (2): 186–190, doi:10.1112/blms/2.2.186.

- Priestley, H. A. (1972), "Ordered topological spaces and the representation of distributive lattices", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 24 (3): 507–530, doi:10.1112/plms/s3-24.3.507, hdl:10338.dmlcz/134149.

- Stanley, R. P. (1997), Enumerative Combinatorics, Volume I, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics 49, Cambridge University Press, pp. 104–112.