In geometry, the Newton–Gauss line (or Gauss–Newton line) is the line joining the midpoints of the three diagonals of a complete quadrilateral.

The midpoints of the two diagonals of a convex quadrilateral with at most two parallel sides are distinct and thus determine a line, the Newton line. If the sides of such a quadrilateral are extended to form a complete quadrangle, the diagonals of the quadrilateral remain diagonals of the complete quadrangle and the Newton line of the quadrilateral is the Newton–Gauss line of the complete quadrangle.

Complete quadrilaterals

Main article: Complete quadrilateralAny four lines in general position (no two lines are parallel, and no three are concurrent) form a complete quadrilateral. This configuration consists of a total of six points, the intersection points of the four lines, with three points on each line and precisely two lines through each point. These six points can be split into pairs so that the line segments determined by any pair do not intersect any of the given four lines except at the endpoints. These three line segments are called diagonals of the complete quadrilateral.

Existence of the Newton−Gauss line

It is a well-known theorem that the three midpoints of the diagonals of a complete quadrilateral are collinear. There are several proofs of the result based on areas or wedge products or, as the following proof, on Menelaus's theorem, due to Hillyer and published in 1920.

Let the complete quadrilateral ABCA'B'C' be labeled as in the diagram with diagonals AA', BB', CC' and their respective midpoints L, M, N. Let the midpoints of BC, CA', A'B be P, Q, R respectively. Using similar triangles it is seen that QR intersects AA' at L, RP intersects BB' at M and PQ intersects CC' at N. Again, similar triangles provide the following proportions,

However, the line A’B'C intersects the sides of triangle △ABC, so by Menelaus's theorem the product of the terms on the right hand sides is −1. Thus, the product of the terms on the left hand sides is also −1 and again by Menelaus's theorem, the points L, M, N are collinear on the sides of triangle △PQR.

Applications to cyclic quadrilaterals

The following are some results that use the Newton–Gauss line of complete quadrilaterals that are associated with cyclic quadrilaterals, based on the work of Barbu and Patrascu.

Equal angles

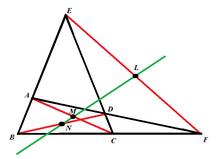

Given any cyclic quadrilateral ABCD, let point F be the point of intersection between the two diagonals AC and BD. Extend the diagonals AB and CD until they meet at the point of intersection, E. Let the midpoint of the segment EF be N, and let the midpoint of the segment BC be M (Figure 1).

Theorem

If the midpoint of the line segment BF is P, the Newton–Gauss line of the complete quadrilateral ABCDEF and the line PM determine an angle ∠PMN equal to ∠EFD.

Proof

First show that the triangles △NPM, △EDF are similar.

Since BE ∥ PN and FC ∥ PM, we know ∠NPM = ∠EAC. Also,

In the cyclic quadrilateral ABCD, these equalities hold:

Therefore, ∠NPM = ∠EDF.

Let R1, R2 be the radii of the circumcircles of △EDB, △FCD respectively. Apply the law of sines to the triangles, to obtain:

Since BE = 2 · PN and FC = 2 · PM, this shows the equality The similarity of triangles △PMN, △DFE follows, and ∠NMP = ∠EFD.

Remark

If Q is the midpoint of the line segment FC, it follows by the same reasoning that ∠NMQ = ∠EFA.

Isogonal lines

Theorem

The line through E parallel to the Newton–Gauss line of the complete quadrilateral ABCDEF and the line EF are isogonal lines of ∠BEC, that is, each line is a reflection of the other about the angle bisector. (Figure 2)

Proof

Triangles △EDF, △NPM are similar by the above argument, so ∠DEF = ∠PNM. Let E' be the point of intersection of BC and the line parallel to the Newton–Gauss line NM through E.

Since PN ∥ BE and NM ∥ EE', ∠BEF = ∠PNF, and ∠FNM = ∠E'EF.

Therefore,

Two cyclic quadrilaterals sharing a Newton-Gauss line

Lemma

Let G and H be the orthogonal projections of the point F on the lines AB and CD respectively.

The quadrilaterals MPGN and MQHN are cyclic quadrilaterals.

Proof

∠EFD = ∠PMN, as previously shown. The points P and N are the respective circumcenters of the right triangles △BFG, △EFG. Thus, ∠PGF = ∠PFG and ∠FGN = ∠GFN.

Therefore,

Therefore, MPGN is a cyclic quadrilateral, and by the same reasoning, MQHN also lies on a circle.

Theorem

Extend the lines GF, HF to intersect EC, EB at I, J respectively (Figure 4).

The complete quadrilaterals EFGHIJ and ABCDEF have the same Newton–Gauss line.

Proof

The two complete quadrilaterals have a shared diagonal, EF. N lies on the Newton–Gauss line of both quadrilaterals. N is equidistant from G and H, since it is the circumcenter of the cyclic quadrilateral EGFH.

If triangles △GMP, △HMQ are congruent, and it will follow that M lies on the perpendicular bisector of the line HG. Therefore, the line MN contains the midpoint of GH, and is the Newton–Gauss line of EFGHIJ.

To show that the triangles △GMP, △HMQ are congruent, first observe that PMQF is a parallelogram, since the points M, P are midpoints of BF, BC respectively.

Therefore,

Also note that

Hence,

Therefore, △GMP and △HMQ are congruent by SAS.

Remark

Due to △GMP, △HMQ being congruent triangles, their circumcircles MPGN, MQHN are also congruent.

Relation with the Miquel point

The point at infinity along the Newton-Gauss line is the isogonal conjugate of the Miquel point.

Generalization

Dao Thanh Oai showed a generalization of the Newton-Gauss line.

For a triangle ABC, let l an arbitrary line and A0B0C0 the Cevian triangle of an arbitrary point P. l intersects BC, CA, and AB at A1, B1, and C1 respectively. Then AA1∩B0C0, BB1∩C0A0, and CC1∩A0B0 are colinear.

If P is the centroid of the triangle ABC, the line is Newton-Gauss line of the quadrilateral composed of AB, BC, CA, and l.

History

The Newton–Gauss line proof was developed by the two mathematicians it is named after: Sir Isaac Newton and Carl Friedrich Gauss. The initial framework for this theorem is from the work of Newton, in his previous theorem on the Newton line, in which Newton showed that the center of a conic inscribed in a quadrilateral lies on the Newton–Gauss line.

The theorem of Gauss and Bodenmiller states that the three circles whose diameters are the diagonals of a complete quadrilateral are coaxal.

Notes

- Alperin, Roger C. (6 January 2012). "Gauss–Newton Lines and Eleven Point Conics". Research Gate.

- ^ Johnson 2007, p. 62

- Pedoe, Dan (1988) , Geometry A Comprehensive Course, Dover, pp. 46–47, ISBN 0-486-65812-0

- Johnson 2007, p. 152

- ^ Patrascu, Ion. "Some Properties of the Newton–Gauss Line" (PDF). Forum Geometricorum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- Thanh Oai, Dao. "Generalizations of some famous classical Euclidean geometry theorems" (PDF). International Journal of Computer Discovered Mathematics (IJCDM). 3.

- Wells, David (1991), The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry, Penguin Books, p. 36, ISBN 978-0-14-011813-1

- Johnson 2007, p. 172

References

- Johnson, Roger A. (2007) , Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0

- (available on-line as) Johnson, Roger A. (1929). "Modern Geometry: An Elementary Treatise on the Geometry of the Triangle and the Circle". HathiTrust. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

External links

- Bogomonly, Alexander. "Theorem of Complete Quadrilateral: What is it?". Retrieved 11 May 2019.

The similarity of triangles △PMN, △DFE follows, and ∠NMP = ∠EFD.

The similarity of triangles △PMN, △DFE follows, and ∠NMP = ∠EFD.