In geometry, bisection is the division of something into two equal or congruent parts (having the same shape and size). Usually it involves a bisecting line, also called a bisector. The most often considered types of bisectors are the segment bisector, a line that passes through the midpoint of a given segment, and the angle bisector, a line that passes through the apex of an angle (that divides it into two equal angles). In three-dimensional space, bisection is usually done by a bisecting plane, also called the bisector.

Perpendicular line segment bisector

Definition

- The perpendicular bisector of a line segment is a line which meets the segment at its midpoint perpendicularly.

- The perpendicular bisector of a line segment also has the property that each of its points is equidistant from segment AB's endpoints:

(D).

The proof follows from and Pythagoras' theorem:

Property (D) is usually used for the construction of a perpendicular bisector:

Construction by straight edge and compass

In classical geometry, the bisection is a simple compass and straightedge construction, whose possibility depends on the ability to draw arcs of equal radii and different centers:

The segment is bisected by drawing intersecting circles of equal radius , whose centers are the endpoints of the segment. The line determined by the points of intersection of the two circles is the perpendicular bisector of the segment.

Because the construction of the bisector is done without the knowledge of the segment's midpoint , the construction is used for determining as the intersection of the bisector and the line segment.

This construction is in fact used when constructing a line perpendicular to a given line at a given point : drawing a circle whose center is such that it intersects the line in two points , and the perpendicular to be constructed is the one bisecting segment .

Equations

If are the position vectors of two points , then its midpoint is and vector is a normal vector of the perpendicular line segment bisector. Hence its vector equation is . Inserting and expanding the equation leads to the vector equation

(V)

With one gets the equation in coordinate form:

(C)

Or explicitly:

(E),

where , , and .

Applications

Perpendicular line segment bisectors were used solving various geometric problems:

- Construction of the center of a Thales' circle,

- Construction of the center of the Excircle of a triangle,

- Voronoi diagram boundaries consist of segments of such lines or planes.

Perpendicular line segment bisectors in space

- The perpendicular bisector of a line segment is a plane, which meets the segment at its midpoint perpendicularly.

Its vector equation is literally the same as in the plane case:

(V)

With one gets the equation in coordinate form:

(C3)

Property (D) (see above) is literally true in space, too:

(D) The perpendicular bisector plane of a segment has for any point the property: .

Angle bisector

An angle bisector divides the angle into two angles with equal measures. An angle only has one bisector. Each point of an angle bisector is equidistant from the sides of the angle.

The 'interior' or 'internal bisector' of an angle is the line, half-line, or line segment that divides an angle of less than 180° into two equal angles. The 'exterior' or 'external bisector' is the line that divides the supplementary angle (of 180° minus the original angle), formed by one side forming the original angle and the extension of the other side, into two equal angles.

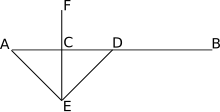

To bisect an angle with straightedge and compass, one draws a circle whose center is the vertex. The circle meets the angle at two points: one on each leg. Using each of these points as a center, draw two circles of the same size. The intersection of the circles (two points) determines a line that is the angle bisector.

The proof of the correctness of this construction is fairly intuitive, relying on the symmetry of the problem. The trisection of an angle (dividing it into three equal parts) cannot be achieved with the compass and ruler alone (this was first proved by Pierre Wantzel).

The internal and external bisectors of an angle are perpendicular. If the angle is formed by the two lines given algebraically as and then the internal and external bisectors are given by the two equations

Triangle

Concurrencies and collinearities

The bisectors of two exterior angles and the bisector of the other interior angle are concurrent.

Three intersection points, each of an external angle bisector with the opposite extended side, are collinear (fall on the same line as each other).

Three intersection points, two of them between an interior angle bisector and the opposite side, and the third between the other exterior angle bisector and the opposite side extended, are collinear.

Angle bisector theorem

Main article: Angle bisector theorem

The angle bisector theorem is concerned with the relative lengths of the two segments that a triangle's side is divided into by a line that bisects the opposite angle. It equates their relative lengths to the relative lengths of the other two sides of the triangle.

Lengths

If the side lengths of a triangle are , the semiperimeter and A is the angle opposite side , then the length of the internal bisector of angle A is

or in trigonometric terms,

If the internal bisector of angle A in triangle ABC has length and if this bisector divides the side opposite A into segments of lengths m and n, then

where b and c are the side lengths opposite vertices B and C; and the side opposite A is divided in the proportion b:c.

If the internal bisectors of angles A, B, and C have lengths and , then

No two non-congruent triangles share the same set of three internal angle bisector lengths.

Integer triangles

There exist integer triangles with a rational angle bisector.

Quadrilateral

The internal angle bisectors of a convex quadrilateral either form a cyclic quadrilateral (that is, the four intersection points of adjacent angle bisectors are concyclic), or they are concurrent. In the latter case the quadrilateral is a tangential quadrilateral.

Rhombus

Each diagonal of a rhombus bisects opposite angles.

Ex-tangential quadrilateral

The excenter of an ex-tangential quadrilateral lies at the intersection of six angle bisectors. These are the internal angle bisectors at two opposite vertex angles, the external angle bisectors (supplementary angle bisectors) at the other two vertex angles, and the external angle bisectors at the angles formed where the extensions of opposite sides intersect.

Parabola

Main article: Parabola § Tangent bisection propertyThe tangent to a parabola at any point bisects the angle between the line joining the point to the focus and the line from the point and perpendicular to the directrix.

Bisectors of the sides of a polygon

Triangle

Medians

Each of the three medians of a triangle is a line segment going through one vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side, so it bisects that side (though not in general perpendicularly). The three medians intersect each other at a point which is called the centroid of the triangle, which is its center of mass if it has uniform density; thus any line through a triangle's centroid and one of its vertices bisects the opposite side. The centroid is twice as close to the midpoint of any one side as it is to the opposite vertex.

Perpendicular bisectors

Main article: CircumcircleThe interior perpendicular bisector of a side of a triangle is the segment, falling entirely on and inside the triangle, of the line that perpendicularly bisects that side. The three perpendicular bisectors of a triangle's three sides intersect at the circumcenter (the center of the circle through the three vertices). Thus any line through a triangle's circumcenter and perpendicular to a side bisects that side.

In an acute triangle the circumcenter divides the interior perpendicular bisectors of the two shortest sides in equal proportions. In an obtuse triangle the two shortest sides' perpendicular bisectors (extended beyond their opposite triangle sides to the circumcenter) are divided by their respective intersecting triangle sides in equal proportions.

For any triangle the interior perpendicular bisectors are given by and where the sides are and the area is

Quadrilateral

The two bimedians of a convex quadrilateral are the line segments that connect the midpoints of opposite sides, hence each bisecting two sides. The two bimedians and the line segment joining the midpoints of the diagonals are concurrent at a point called the "vertex centroid" and are all bisected by this point.

The four "maltitudes" of a convex quadrilateral are the perpendiculars to a side through the midpoint of the opposite side, hence bisecting the latter side. If the quadrilateral is cyclic (inscribed in a circle), these maltitudes are concurrent at (all meet at) a common point called the "anticenter".

Brahmagupta's theorem states that if a cyclic quadrilateral is orthodiagonal (that is, has perpendicular diagonals), then the perpendicular to a side from the point of intersection of the diagonals always bisects the opposite side.

The perpendicular bisector construction forms a quadrilateral from the perpendicular bisectors of the sides of another quadrilateral.

Area bisectors and perimeter bisectors

Triangle

There is an infinitude of lines that bisect the area of a triangle. Three of them are the medians of the triangle (which connect the sides' midpoints with the opposite vertices), and these are concurrent at the triangle's centroid; indeed, they are the only area bisectors that go through the centroid. Three other area bisectors are parallel to the triangle's sides; each of these intersects the other two sides so as to divide them into segments with the proportions . These six lines are concurrent three at a time: in addition to the three medians being concurrent, any one median is concurrent with two of the side-parallel area bisectors.

The envelope of the infinitude of area bisectors is a deltoid (broadly defined as a figure with three vertices connected by curves that are concave to the exterior of the deltoid, making the interior points a non-convex set). The vertices of the deltoid are at the midpoints of the medians; all points inside the deltoid are on three different area bisectors, while all points outside it are on just one. The sides of the deltoid are arcs of hyperbolas that are asymptotic to the extended sides of the triangle. The ratio of the area of the envelope of area bisectors to the area of the triangle is invariant for all triangles, and equals i.e. 0.019860... or less than 2%.

A cleaver of a triangle is a line segment that bisects the perimeter of the triangle and has one endpoint at the midpoint of one of the three sides. The three cleavers concur at (all pass through) the center of the Spieker circle, which is the incircle of the medial triangle. The cleavers are parallel to the angle bisectors.

A splitter of a triangle is a line segment having one endpoint at one of the three vertices of the triangle and bisecting the perimeter. The three splitters concur at the Nagel point of the triangle.

Any line through a triangle that splits both the triangle's area and its perimeter in half goes through the triangle's incenter (the center of its incircle). There are either one, two, or three of these for any given triangle. A line through the incenter bisects one of the area or perimeter if and only if it also bisects the other.

Parallelogram

Any line through the midpoint of a parallelogram bisects the area and the perimeter.

Circle and ellipse

All area bisectors and perimeter bisectors of a circle or other ellipse go through the center, and any chords through the center bisect the area and perimeter. In the case of a circle they are the diameters of the circle.

Bisectors of diagonals

Parallelogram

The diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other.

Quadrilateral

If a line segment connecting the diagonals of a quadrilateral bisects both diagonals, then this line segment (the Newton Line) is itself bisected by the vertex centroid.

Volume bisectors

A plane that divides two opposite edges of a tetrahedron in a given ratio also divides the volume of the tetrahedron in the same ratio. Thus any plane containing a bimedian (connector of opposite edges' midpoints) of a tetrahedron bisects the volume of the tetrahedron

References

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Exterior Angle Bisector." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource.

- Spain, Barry. Analytical Conics, Dover Publications, 2007 (orig. 1957).

- ^ Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007 (orig. 1929).

- Oxman, Victor. "On the existence of triangles with given lengths of one side and two adjacent angle bisectors", Forum Geometricorum 4, 2004, 215–218. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2004volume4/FG200425.pdf

- Simons, Stuart. Mathematical Gazette 93, March 2009, 115-116.

- Mironescu, P., and Panaitopol, L., "The existence of a triangle with prescribed angle bisector lengths", American Mathematical Monthly 101 (1994): 58–60.

- Oxman, Victor, "A purely geometric proof of the uniqueness of a triangle with prescribed angle bisectors", Forum Geometricorum 8 (2008): 197–200.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Quadrilateral." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Quadrilateral.html

- ^ Mitchell, Douglas W. (2013), "Perpendicular Bisectors of Triangle Sides", Forum Geometricorum 13, 53-59. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2013volume13/FG201307.pdf

- Altshiller-Court, Nathan, College Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007.

- ^ Dunn, Jas. A.; Pretty, Jas. E. (May 1972). "Halving a triangle". The Mathematical Gazette. 56 (396): 105–108. doi:10.2307/3615256. JSTOR 3615256.

- Kodokostas, Dimitrios, "Triangle Equalizers," Mathematics Magazine 83, April 2010, pp. 141-146.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Tetrahedron." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Tetrahedron.html

- Altshiller-Court, N. "The tetrahedron." Ch. 4 in Modern Pure Solid Geometry: Chelsea, 1979.

External links

- The Angle Bisector at cut-the-knot

- Angle Bisector definition. Math Open Reference With interactive applet

- Line Bisector definition. Math Open Reference With interactive applet

- Perpendicular Line Bisector. With interactive applet

- Animated instructions for bisecting an angle and bisecting a line Using a compass and straightedge

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Line Bisector". MathWorld.

This article incorporates material from Angle bisector on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

Category: also has the property that each of its points

also has the property that each of its points  is

is  .

.

and

and

, whose centers are the endpoints of the segment. The line determined by the points of intersection of the two circles is the perpendicular bisector of the segment.

, whose centers are the endpoints of the segment. The line determined by the points of intersection of the two circles is the perpendicular bisector of the segment. , the construction is used for determining

, the construction is used for determining  at a given point

at a given point  : drawing a circle whose center is

: drawing a circle whose center is  , and the perpendicular to be constructed is the one bisecting segment

, and the perpendicular to be constructed is the one bisecting segment  are the position vectors of two points

are the position vectors of two points  and vector

and vector  is a

is a  . Inserting

. Inserting  and expanding the equation leads to the vector equation

and expanding the equation leads to the vector equation

one gets the equation in coordinate form:

one gets the equation in coordinate form:

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

one gets the equation in coordinate form:

one gets the equation in coordinate form:

.

.

and

and  then the internal and external bisectors are given by the two equations

then the internal and external bisectors are given by the two equations

, the semiperimeter

, the semiperimeter  and A is the angle opposite side

and A is the angle opposite side  , then the length of the internal bisector of angle A is

, then the length of the internal bisector of angle A is

and if this bisector divides the side opposite A into segments of lengths m and n, then

and if this bisector divides the side opposite A into segments of lengths m and n, then

and

and  , then

, then

and

and  where the sides are

where the sides are  and the area is

and the area is

. These six lines are concurrent three at a time: in addition to the three medians being concurrent, any one median is concurrent with two of the side-parallel area bisectors.

. These six lines are concurrent three at a time: in addition to the three medians being concurrent, any one median is concurrent with two of the side-parallel area bisectors.

i.e. 0.019860... or less than 2%.

i.e. 0.019860... or less than 2%.