| Part of a series on the |

|---|

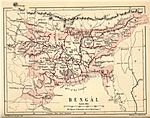

| History of Bengal |

|

| Ancient Kingdoms |

| Classical Dynasties |

| Islamic Bengal |

| Colonial Bengal |

| Post-partition era |

Modern period

|

| Related |

The city of Chattogram (Chittagong) is traditionally centred around its seaport which has existed since the 4th century BCE. One of the world's oldest ports with a functional natural harbor for centuries, Chittagong appeared on ancient Greek and Roman maps, including on Ptolemy's world map. Chittagong port is the oldest and largest natural seaport and the busiest port of Bay of Bengal. It was located on the southern branch of the Silk Road. The city was home to the ancient independent Buddhist kingdoms of Bengal like Samatata and Harikela. It later fell under of the rule of the Gupta Empire, the Gauda Kingdom, the Pala Empire, the Chandra Dynasty, the Sena Dynasty and the Deva Dynasty of eastern Bengal. Arab Muslims traded with the port from as early as the 9th century. Historian Lama Taranath is of the view that the Buddhist king Gopichandra had his capital at Chittagong in the 10th century. According to Tibetan tradition, this century marked the birth of Tantric Buddhism in the region. The region has been explored by numerous historic travellers, most notably Ibn Battuta of Morocco who visited in the 14th century. During this time, the region was conquered and incorporated into the independent Sonargaon Sultanate by Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah in 1340 AD. Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah constructed a highway from Chittagong to Chandpur and ordered the construction of many lavish mosques and tombs. After the defeat of the Sultan of Bengal Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah in the hands of Sher Shah Suri in 1538, the Arakanese Kingdom of Mrauk U managed to regain Chittagong. From this time onward, until its conquest by the Mughal Empire, the region was under the control of the Portuguese and the Magh pirates (a notorious name for Arakanese) for 128 years.

The Mughal commander Shaista Khan, his son Buzurg Umed Khan, and Farhad Khan, expelled the Arakanese from the area during the Conquest of Chittagong in 1666 and established Mughal rule there. After the Arakanese expulsion, Islamabad, as the area came to be known, made great strides in economic progress. This can mainly be attributed to an efficient system of land-grants to selected diwans or faujdars to clear massive areas of hinterland and start cultivation. The Mughals, similar to the Afghans who came earlier, also built mosques having a rich contribution to the architecture in the area. What is called Chittagong today also began to have improved connections with the rest of Mughal Bengal. The city was occupied by Burmese troops shortly in First Anglo-Burmese War in 1824 and the British increasingly grew active in the region and it fell under the British Empire. The people of Chittagong made several attempts to gain independence from the British, notably on 18 November 1857 when the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th companies of the 34th Bengal Infantry Regiment stationed at Chittagong rose in rebellion and released all the prisoners from jail but were suppressed by the Kuki scouts and the Sylhet Light Infantry (10th Gurkha Rifles).

Chittagong grew at the beginning of the twentieth century after the partition of Bengal and the creation of the province of Eastern Bengal and Assam. The construction of the Assam Bengal Railway to Chittagong facilitated further development of economic growth in the city. However, revolutionaries and opposition movements grew during this time. Many people in Chittagong supported Khilafat and Non-Cooperation movements.

Etymology

There are multiple competing hypotheses about how the name 'Chittagong' evolved. One of these claims that the original form of the name was 'Chattagram' or 'Chatigrama'. Here, 'chati' means '(earthen) lamp', while 'grama' is a common term for 'village'. By local linguistic variation it became 'chita-gnao'. Here 'gnao' with nasal 'g' means 'gram' or village. According to local sayings, early historic settlements in the region used to manufacture and supply earthen lamps, e.g. to courts and universities.

Other possible historical sources of the name include Tsit-Ta-Gung (Arakanese inscription), Shwet Gang (meaning 'white sea') and Chaityagrama.

Ancient period

Stone Age fossils and tools unearthed in the region indicate that Chittagong has been inhabited since Neolithic times. It is an ancient port city, with a recorded history dating back to the 4th century BC. Its harbour was mentioned in Ptolemy's world map in the 2nd century as one of the most impressive ports in the East. The region was part of the ancient Bengali Samatata and Harikela kingdoms. The Chandra Dynasty once dominated the area, and was followed by the Varman Dynasty, Gauda Kingdom, Pala Empire, Sena Dynasty and Deva Dynasty of ancient Bengal.

Chinese traveler Xuanzang described the area as "a sleeping beauty rising from mist and water" in the 7th century.

Early medieval period

Arab Muslims (and later Persians) frequented Chittagong for trade beginning in the 9th century. In 1154, Muhammad al-Idrisi mentioned a busy shipping route between Basra and Chittagong, connecting it with the Abbasid capital of Baghdad. Many Sufi missionaries settled in Chittagong and played an instrumental role in the spread of Islam. The first Persian settlers also arrived for trade and religious purposes. Persians and other Iranic peoples deeply affected the history of the Bengal Sultanate, with Persian being one of the main languages of the Muslim state, as well as also influencing the Chittagonian dialect and writing scripts. It has been affirmed that much of the Muslim population in Chittagong are descendants of the Arab and Persian settlers.

The Sultan of Bengal, Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah, invaded parts of the Tripura Kingdom and conquered Chittagong in 1340. A number of sufi saints under Badruddin Allama (Badr Pir) accompanied him. The Sultan annexed the region to the Bengal Sultanate as a mulk (province). A sufi saint named Shayda was appointed to rule over Chittagong. The area became the principal maritime gateway to the Sultanate, which was reputed as one of the wealthiest states in the subcontinent. Medieval Chittagong was a hub for maritime trade with China, Sumatra, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Southwest Asia and East Africa. It was notable for its medieval trades in pearls, silk, muslin, rice, bullion, horses and gunpowder. The port was also a major shipbuilding hub.

Ibn Battuta visited the port city in 1345. Niccolò de' Conti, from Venice, also visited around the same time as Battuta. Chinese admiral Zheng He's treasure fleet anchored in Chittagong during imperial missions to the Sultanate of Bengal.

Dhanya Manikya (r. 1463 to 1515) expanded the Twipra Kingdom's territorial domain well into eastern Bengal which included parts of modern-day Chittagong, Dhaka and Sylhet. Chittagong featured prominently in the military history of the Bengal Sultanate, including during the Reconquest of Arakan and the Bengal Sultanate–Kingdom of Mrauk U War of 1512–1516.

During the reign of Sultan Alauddin Husain Shah, Paragal Khan was appointed as the Lashkar (military commander) of Chittagong. Following the Bengal Sultanate–Kingdom of Mrauk U War of 1512–1516, Paragal was made the Governor of Chittagong too. He was then succeeded by his son, Chhuti Khan.

Sultan Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah gave permission for the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong to be established in 1528. Chittagong became the first European colonial enclave in Bengal. The Bengal Sultanate lost control of Chittagong in 1531 after Arakan declared independence and established the Kingdom of Mrauk U. This altered geopolitical landscape allowed the Portuguese unhindered control of Chittagong for over a century.

Portuguese era

Portuguese ships from Goa and Malacca began frequenting the port city in the 16th century. The cartaz system was introduced and required all ships in the area to purchase naval trading licenses from the Portuguese settlement. The Slave trade and piracy flourished. The nearby island of Sandwip was conquered in 1602. In 1615, the Portuguese Navy defeated a joint Dutch East India Company and Arakanese fleet near the coast of Chittagong.

In 1666, the Mughal government of Bengal led by viceroy Shaista Khan moved to retake Chittagong from Portuguese and Arakanese control. They launched the Mughal conquest of Chittagong. The Mughals attacked the Arakanese from the jungle with a 6,500-strong army, which was further supported by 288 Mughal naval ships blockading the Chittagong harbour. After three days of battle, the Arakanese surrendered. The Mughals expelled the Portuguese from Chittagong. Mughal rule ushered a new era in the history of Chittagong territory to the western bank of Kashyapnadi (Kaladan river). The port city was renamed as Islamabad. The Grand Trunk Road connected it with North India and Central Asia. Economic growth increased due to an efficient system of land grants for clearing hinterlands for cultivation. The Mughals also contributed to the architecture of the area, including the building of Fort Ander and many mosques. Chittagong was integrated into the prosperous greater Bengali economy, which also included Orissa and Bihar. Shipbuilding swelled under Mughal rule and the Sultan of Turkey had many Ottoman warships built in Chittagong during this period.

Portuguese settlements

Main article: Portuguese settlement in ChittagongLopo Soares de Albergaria, the 3rd governor of Portuguese India, sent a fleet of four ships commanded by João da Silveira, who after plundering ships from Bengal, anchored at Chittagong on 9 May 1518. Silveira left for Ceylon afterwards.

In October 1521, two separate Portuguese missions went to the court of Sultan Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah to establish diplomatic relations with Bengal. One was led by explorer Rafael Perestrello and another one by captain Lopo de Brito. Brito's representative, Goncalo Tavares, obtained a duty-free arrangement for trade in Bengal for the Portuguese merchants. The two Portuguese embassies, both claiming official status, created confusion and led to a fight between them at Chittagong.

The Portuguese settlement became a major bone of contention between the Mughal Empire, the Kingdom of Mrauk U, the Burmese Empire, the Chakma kingdom and the Kingdom of Tripura.

According to a 1567 note of Caesar Federeci, every year thirty or thirty five ships anchored in Chittagong port.

The Mughal conquest of Chittagong in 1666 brought an end to the Portuguese dominance of more than 130 years in city.

By the early 18th century, the Portuguese settlements were located at Dianga, Feringhee Bazar in Chittagong district and in the municipal ward of Jamal Khan in Chittagong.

Arakanese conquest

The Arakanese ruled over Chittagong from the late 16th century to 1666, marking an important and eventful period in the region's history. During this time, Chittagong became a center for trade and naval activities, with the Arakanese relying on their strong fleets and alliances, including Portuguese mercenaries, to maintain control.

The decline of Arakanese rule was triggered by political conflicts, including their involvement in the Mughal succession struggle. The assassination of Mughal prince Shah Shuja in Arakan strained relations with the Mughal Empire, prompting a decisive campaign led by Subahdar Shaista Khan in 1666. The Mughals recaptured Chittagong, ending nearly a century of Arakanese dominance. This period left a lasting legacy on the region, highlighting the interplay of trade, politics, and cultural exchange between Bengal and Arakan.

The Arakanese Kingdom of Mrauk U declared independence from the Sultanate of Bengal and conquered Chittagong in 1531 until 1666 when the Mughals took over.

Mughal period

During the governorship of Subahdar Ibrahim Khan Fath-i-Jang, Abadullah was serving as the Karori of Chatgaon (Chittagong), responsible for the collection of a crore of dams in the area. The Mughal Army defeated the Arakanese Army and successfully annexed Chatgaon to the Mughal Empire in 1666. They began to build the city up in a planned way. The name of different areas in the city, including Rahmatganj, Hamzer Bagh, Ghat Farhadbeg (after Farhad Beg) and Askar Dighir Par, were named after the faujdars appointed by the Mughal emperors. Four mosque-tomb complexes – Bagh-i-Hamza Masjid, Miskin Shah Mulla Masjid, Kadam Mubarak Masjid, Bayazid Bostami Masjid and one tomb, The Shahjahani Tomb, survived from this period.

In 1685, the English East India Company sent out an expedition under Admiral Nicholson with the instructions to seize and fortify Chittagong on behalf of the English; however, the expedition, the Child's War, proved abortive. Two years later, the company's Court of Directors decided to make Chittagong the headquarters of their Bengal trade and sent out a fleet of ten or eleven ships to seize it under Captain Heath. However, after reaching Chittagong in early 1689, the fleet found the city too strongly held and abandoned their attempt at capturing it. The city remained under the possession of the Nawabs of Bengal until 1793 when East India Company took complete control of the former Mughal province of Bengal.

British rule

The First Anglo-Burmese War in 1823 threatened the British hold on Chittagong. There were a number of rebellions against British rule, notably during the Indian rebellion of 1857, when the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th companies of the 34th Bengal Infantry Regiment revolted under Havildar Rajab Ali Khan and released all prisoners from the city's jail. In a backlash, the rebels were suppressed by the Sylhet Light Infantry.

In British ruling period, they created some educational institutions in Chittagong. Chittagong Collegiate School and College, Chittagong College are two of them. Railways were introduced in 1865, beginning with the Eastern Bengal Railway connecting Chittagong to Dacca and Calcutta. The Assam Bengal Railway connected the port city to its interior economic hinterland, which included the world's largest tea and jute producing regions, as well as one of the world's earliest petroleum industries. Chittagong was a major center of trade with British Burma. It hosted many prominent companies of the British Empire, including James Finlay, Duncan Brothers, Burmah Oil, the Indo-Burma Petroleum Company, Lloyd's, Mckenzie and Mckenzie, the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China, Turner Morrison, James Warren, the Raleigh Brothers, Lever Brothers and the Shell Oil Company.

The Chittagong armoury raid and Battle of Jalalabad by Bengali revolutionaries, led by Surya Sen, in 1930 was a major event in British India's anti-colonial history.

World War II

During World War II, the British used Chittagong as an important frontline military base in the Southeast Asian Theater. Sporadic bombing by the Japanese Air Force, notably in April 1942 and again on 20 and 24 December 1942, resulted in military relocation to Comilla. It was a critical air, naval and military base for Allied Forces during the Burma Campaign against Japan. The Imperial Japanese Air Force carried out air raids on Chittagong in April and May 1942, in the run up to the aborted Japanese invasion of Bengal. British forces were forced to temporarily withdraw to Comilla and the city was evacuated. After the Battle of Imphal, the tide turned in favor of the Allied Forces. The United States Army Air Forces' 4th Combat Cargo Group was stationed at Chittagong Airfield in 1945. Commonwealth forces included troops from Britain, India, Australia and New Zealand. The war had major negative impacts on the city, including the growth of refugees and the Great Famine of 1943.

Post-war expansion

After the war, rapid industrialisation and development saw the city grow beyond its previous municipal area, particularly in the southwest up to Patenga, where Chittagong International Airport is now located. The former villages of Halishahar, Askarabad and Agrabad became integrated into the city. Many wealthy Chittagonians profited from wartime commerce.

East Pakistan

The Partition of British India in 1947 made Chittagong the chief port of East Pakistan. In the 1950s, Chittagong witnessed increased industrial development. Among pioneering industrial establishments included those of Chittagong Jute Mills, the Burmah Eastern Refinery, the Karnaphuli Paper Mills and Pakistan National Oil. However, East Pakistanis complained of a lack of investment in Chittagong in comparison to Karachi in West Pakistan, even though East Pakistan generated more exports and had a larger population. The Awami League demanded that the country's naval headquarters be shifted from Karachi to Chittagong.

The Chittagong Development Authority (CDA) was established by the government of East Pakistan in 1959 to manage this growth and drew up a master plan to be reviewed every five years to plan its urban development. By 1961 the CDA had drawn up a regional plan covering an area of 212 square miles (550 km) and a master plan covering an area of 100 square miles (260 km). Over the decades, especially after the losses of 1971, the master plan developed into several specific areas of management, including the Multi-Sectoral Investment Plan for drainage and flood-protection of Chittagong City and a plan for easing the traffic congestion and making the system more efficient.

University of Chittagong was founded in November 1966.

During the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, Chittagong witnessed heavy fighting between rebel Bengali military regiments and the Pakistan Army as the latter was denied access to the port. It covered Sector 1 in the Mukti Bahini chain of command, being commanded by Major Ziaur Rahman and later Captain Rafiqul Islam. The Bangladeshi Declaration of Independence was broadcast from Kalurghat Radio Station and transmitted internationally through foreign ships in Chittagong Port. Ziaur Rahman and M A Hannan were responsible for announcing the independence declaration from Chittagong on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman from the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra. The Pakistani military, and supporting Razakar militias, carried out widespread atrocities against civilians in the city. Mukti Bahini naval commandos drowned several Pakistani warships during Operation Jackpot in August 1971. In December 1971, the Bangladesh Air Force and the Indian Air Force carried out heavy bombing of facilities occupied by the Pakistani military. A naval blockade was also enforced.

Bangladesh

Following the independence of Bangladesh, the city underwent a major rehabilitation and reconstruction programme and regained its status as an important port within a few years.

After the war, the Soviet Navy was tasked with clearing mines in Chittagong Port and restoring its operational capability. 22 vessels of the Soviet Pacific Fleet sailed from Vladivostok to Chittagong in May 1972. The process of clearing mines in the dense water harbour took nearly a year, and claimed the life of one Soviet marine. Chittagong soon regained its status as a major port, with cargo tonnage surpassing pre-war levels in 1973. In free market reforms launched by President Ziaur Rahman in the late 1970s, the city became home to the first export processing zones in Bangladesh. Zia was assassinated during an attempted military coup in Chittagong in 1981. The 1991 Bangladesh cyclone inflicted heavy damage on the city. The Japanese government financed the construction of several heavy industries and an international airport in the 1980s and 90s. Bangladeshi private sector investments increased since 1991, especially with the formation of the Chittagong Stock Exchange in 1995. The port city has been the pivot of Bangladesh's emerging economy in recent years, with the country's rising GDP growth rate.

References

- "Showcasing glorious past of Chittagong". The Daily Star. 31 March 2012.

- Roy, Niharranjan (1993). Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba Calcutta: Dey's Publishing, ISBN 81-7079-270-3, pp.408-9

- ^ Dey, Arun Bikash (2012). "Chittagong City". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- "About Chittagong:History". Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2013.Retrieved: 30 December 2013

- "India's History : Modern India : The First Partition of Bengal : 1905". Archived from the original on 26 August 2004.

- "Lamp stand with oil lamp". Virtual Collection of Asian Masterpieces. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Bangladesh towards 21st century". google.co.uk. 1994.

- "Custom House Chittagong". Archived from the original on 9 November 2015.

- Mannan, Abdul (1 April 2012). "Chittagong – looking for a better future". New Age. Dhaka. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013.

- "Past of Ctg holds hope for economy". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Trudy, Ring; M. Salkin, Robert; La Boda, Sharon; Edited by Trudy Ring (1996). International dictionary of historic places. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-884964-04-4. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- "The Role of the Persian Language in Bengali and the World Civilization: An Analytical Study" (PDF). www.uits.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Eaton, Richard M. (1994). The rise of Islam and the Bengal frontier, 1204-1760. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195635867.

- "Bangladesh - Ethnic groups". Encyclopedia Britannica. March 2024.

- Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- Donkin, R. A. (1998). Beyond Price. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871692245.

- Dunn, Ross E. (1986). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05771-5.

- Ray, Aniruddha (2012). "Conti, Nicolo de". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Sen, Dineshchandra (1988). The Ballads of Bengal. Mittal Publications. pp. xxxiii.

- ^ Eaton, Richard Maxwell (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. pp. 234, 235. ISBN 0-520-20507-3.

- Dasgupta, Biplab (2005). European trade and colonial conquest. Anthem Press. ISBN 1-84331-029-5.

- Dasgupta, Biplab (2005). European trade and colonial conquest. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 1-84331-029-5.

- Hossain, Khandakar Akhter (2012). "Shipbuilding Industry". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- "Prospects of shipbuilding industry in Bangladesh". New Age. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Pearson, M.N. (2006). The Portuguese in India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-02850-7.

- Chittagong, Asia and Oceania:International Dictionary of Historic Places

- ^ Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Portuguese, The". In Islam, Sirajul; Ray, Aniruddha (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Nusrat Shah". In Islam, Sirajul; Chowdhury, AM (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Ray, Jayanta Kumar (2007). Aspects of India's International relations, 1700 to 2000 : South Asia and the World. New Delhi: Pearson Longman, an imprint of Pearson Education. ISBN 978-8131708347.

- Johnston, Harry (1993). Pioneers in India. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 442. ISBN 8120608437. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- "History of the District Chittagong". www.chittagong.gov.bd. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- "Arakan - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- Keat Gin Ooi (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 1. p. 171. ISBN 1576077705.

- Nathan, Mirza (1936). M. I. Borah (ed.). Baharistan-I-Ghaybi – Volume II. Gauhati, Assam, British Raj: Government of Assam. p. 447.

- "Past of Ctg holds hope for economy". The Daily Star. 18 March 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- Osmany, Shireen Hasan; Mazid, Muhammad Abdul (2012). "Chittagong Port". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Hunter, William Wilson (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 308, 309.

- ^ Osmany, Shireen Hasan (2012). "Chittagong City". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- "Rare 1857 reports on Bengal uprisings". The Times of India.

- "Nippon Bombers Raid Chittagong". Miami Daily News. Associated Press. 9 May 1942. p. 1.

- "Japanese Raid Chittagong: Stung By Allied Bombing". The Sydney Morning Herald. 14 December 1942. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1983) . Air Force Combat Units of World War II (PDF). Office of Air Force History. p. 35. ISBN 0-912799-02-1.

- Mannan, Abdul (25 June 2011). "Rediscovering Chittagong - the gateway to Bangladesh". Daily Sun (Editorial). Dhaka. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- Azim, Fayezul (2012). "University of Chittagong". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Operation Jackpot". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- Administrator. "Muktijuddho (Bangladesh Liberation War 1971) part 37 - Bangladesh Biman Bahini (Bangladesh Air Force or BAF) - History of Bangladesh". Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- Maj (Retd) SHAMSHAd ALI KHAN. "Comilla-Chittagong Axis (1971 War)". DefenceJournal.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2003.

- Rao, K. V. Krishna (1991). Prepare Or Perish: A Study of National Security. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 9788172120016 – via Google Books.

- "In the Spirit of Brotherly Love". The Daily Star. 29 May 2014.

- "Rescue Operation on Demining and Clearing of Water Area of Bangladesh Seaports 1972-74". Consulate General of the Russian Federation in Chittagong. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

| Bangladesh articles | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

| ||||||||||||||

| Geography | |||||||||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||||||||

| Economy |

| ||||||||||||||

| Society |

| ||||||||||||||

| Chittagong related topics | |

|---|---|

| History |

|

| Government and localities | |

| Attractions | |

| Economy and transport |

|

| Education |

|

| Culture and sports | |

| Other topics | |

| Portuguese Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||