This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Ethnic group

| Szlovákiai magyarok | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 456,154 (2021, census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Southern Slovakia | |

| Languages | |

| Mainly Hungarian and Slovak | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism (73%), Calvinism (16%) and others | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hungarian diaspora and Slovaks in Hungary |

Hungarians constitute the largest minority in Slovakia. According to the 2021 Slovak census, 456,154 people (or 8.37% of the population) declared themselves Hungarian, while 462,175 (8.48% of the population) stated that Hungarian was their mother tongue.

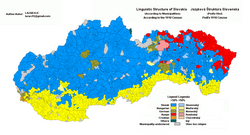

Hungarians in Slovakia are predominantly concentrated in the southern part of the country, near the border with Hungary. They form the majority in two districts, Komárno and Dunajská Streda.

History

The First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938)

Origins of the Hungarian minority

After the defeat of the Central Powers on the Western Front in 1918, the Treaty of Trianon was signed between the winning Entente powers and Hungary in 1920 at the Paris Peace Conference. The treaty greatly reduced the Kingdom of Hungary's borders, including ceding all of Upper Hungary to Czechoslovakia, in which Slovaks made up the dominant ethnicity. In consideration of the strategic and economic interests of their new ally, Czechoslovakia, the victorious allies set the Czechoslovak–Hungarian border further south than the Slovak–Hungarian language border. Consequently, the newly created state contained areas that were overwhelmingly ethnic Hungarian.

Demographics

According to the 1910 census conducted in Austria-Hungary, there were 884,309 ethnic Hungarians, constituting 30.2% of the population in what is now Slovakia and Carpatho-Ukraine. The Czechoslovak census of 1930 recorded 571,952 Hungarians. In the 2001 census, by contrast, the percentage of ethnic Hungarians in Slovakia was 9.7%, a decrease of two-thirds in percentage but not in absolute number, which remained roughly the same.

Between 1880 and 1910, the Hungarian population increased by 55.9%, while Slovak population increased by only 5.5% though Slovaks had a higher birth rate at the same time. The level of differences does not explain this process by emigration (higher among Slovaks) or by population moves and natural assimilation during industrialization. In 16 northern counties, the Hungarian population rose by 427,238, while the majority Slovak population rose only by 95,603. The number of "Hungarians who can speak Slovak" unusually increased in a time when Hungarians really had no motivation to learn it – by 103,445 in southern Slovakia in absolute numbers, by 100% in Pozsony, Nyitra, Komárom, Bars and Zemplén County and more than 3 times in Košice. After the creation of Czechoslovakia, people could declare their nationality more freely.

Furthermore, censuses from the Kingdom of Hungary and Czechoslovakia differed in their view on the nationality of the Jewish population. Czechoslovakia allowed Jews to declare a separate Jewish nationality, while Jews were counted mostly as Hungarians in the past. In 1921, 70,529 people declared Jewish nationality.

The population of larger towns like Košice or Bratislava were historically bilingual or trilingual, and some might declare the most-popular or the most-beneficial nationality at a particular time. According to the Czechoslovak censuses, 15–20% of the population in Košice was Hungarian, but during the parliamentary elections, the "ethnic" Hungarian parties received 35–45% of the total votes (excluding those Hungarians who voted for the Communists or the Social Democrats). However, such comparisons are not fully reliable, because "ethnic" Hungarian parties did not necessarily present themselves to Slovak population as "ethnic", and also had Slovak subsidiaries.

Hungarian state employees who refused to take an oath of allegiance had to decide between retirement and moving to Hungary. The same applied to Hungarians who did not receive Czechoslovak citizenship, who were forced to leave or simply did not self-identify with the new state. Two examples of people forced to leave were the families of Béla Hamvas and Albert Szent-Györgyi. The numerous refugees (including even more from Romania) necessitated the construction of new housing projects in Budapest (Mária-Valéria telep, Pongrácz-telep), which gave shelter to refugees numbering at least in the tens of thousands.

Education

At the beginning of the school year 1918–19, Slovakia had 3,642 elementary schools. Only 141 schools taught in Slovak, 186 in Slovak and Hungarian and 3,298 in Hungarian. After system reform, Czechoslovakia provided an educational network for the region. Due to the lack of qualified personnel among Slovaks – a lack of schools above elementary level, banned grammar schools and no Slovak teacher institutes – Hungarian teachers were replaced in large numbers by Czechs. Some Hungarian teachers resolved their existential question by moving to Hungary. According to government regulation from 28 August 1919, Hungarian teachers were permitted to teach only if they took an oath of allegiance to Czechoslovakia.

In the early years of Czechoslovakia, the Hungarian minority in Slovakia had a complete education network, except for canceled colleges. The Czechoslovak Ministry of Education derived its policy from international agreements signed after the end of World War I. In the area inhabited by the Hungarian minority, Czechoslovakia preserved untouched the network of Hungarian municipal or denominational schools. However, these older schools inherited from Austria-Hungary were frequently crowded, under-funded, and less attractive than new, well-equipped Slovak schools built by the state. In the school year 1920–21, the Hungarian minority had 721 elementary schools, which only decreased by one in the next 3 years. Hungarians had also 18 higher "burgher" schools, 4 grammar schools and 1 teacher institute. In the school year 1926–27, there were 27 denominational schools which can also be classified as minority schools, because none of them taught in Slovak. Hungarian representatives criticized the mainly reduced number of secondary schools.

In the 1930s, Hungarians had 31 kindergartens, 806 elementary schools, 46 secondary schools, and 576 Hungarian libraries at schools. A department of Hungarian literature was created at the Charles University of Prague.

Hungarian Elisabeth Science University, founded in 1912 and teaching since 1914 (with interruptions during war), was replaced by Comenius University to fulfil demands for qualified experts in Slovakia. Hungarian professors had refused to take an oath of allegiance and the original school was closed by government decree; as in other cases, teachers were replaced by Czech professors. Comenius University remained the only university in inter-war Slovakia.

Culture

The Hungarian minority participated in a press boom in Czechoslovakia between wars. Before the creation of Czechoslovakia, 220 periodicals were issued in the territory of Slovakia, 38 of them in Slovak. During the interwar period, the number of Slovak and Czech periodicals in Slovakia increased to more than 1,050, while the number of periodicals in minority languages (mostly Hungarian) increased almost to 640 (only a small portion of these were published through the entire interwar period).

The Czechoslovak state preserved and financially supported two Hungarian professional theatre companies in Slovakia, and an additional one in Carpathian Ruthenia. Hungarian cultural life was maintained in regional cultural associations like Jókai Society, Toldy Group or Kazinczy Group. In 1931, the Hungarian Scientific, Literary and Artistic Society in Czechoslovakia (Masaryk's Academy) was founded on the initiative of the Czechoslovak president. Hungarian culture and literature was covered by journals like Magyar Minerva, Magyar Irás, Új Szó and Magyar Figyelő. The last of these had the goal to develop Czech–Slovak–Hungarian literary relationships and a common Czechoslovak consciousness. Hungarian books were published by several literary societies and Hungarian publishers, though not in great number.

Policy

The democratization of Czechoslovakia extended political rights of the Hungarian population in comparison to the Kingdom of Hungary before 1918. Czechoslovakia introduced universal suffrage, while full women's suffrage was not achieved in Hungary until 1945. The first Czechoslovak parliamentary elections had 90% voter-turnout in Slovakia. After the Treaty of Trianon, the Hungarian minority lost illusions about a "temporary state" and had to adapt to a new situation. Hungarian political structures in Czechoslovakia were formed relatively late and finalized their formation only in the mid-1920s. The political policy of the Hungarian minority can be categorized by their attitude to the Czechoslovak state and peace treaties into three main directions: activists, communists, and negativists.

Hungarian "activists" saw their future in cohabitation and cooperation with the majority population. They had a pro-Czechoslovak orientation and supported the government. In the early 1920s, they founded separate political parties and were later active in Hungarian sections of Czechoslovak state-wide parties. The pro-Czechoslovak Hungarian National Party (not to be confused with a different Hungarian National Party formed later) participated in the parliamentary elections of 1920, but failed. In 1922, the Czechoslovak government proposed correction of some injustices against minorities in exchange for absolute loyalty and recognition of the Czechoslovak state. Success of activism culminated in the mid-1920s. In 1925, the Hungarian National Party participated in the adoption of several important laws, including those regulating state citizenship. In 1926, the party unsuccessfully held negotiations about participation in government. Left-wing Hungarian activists were active in the Hungarian-German Social Democratic Party and later in the Hungarian Social Democratic Labour Party. Hungarian social democrats failed in competition with communists but were active as a Hungarian section of the Czechoslovak Social Democracy Party (ČSDD). In 1923, Hungarian activists with agrarian orientation founded the Republican Association of Hungarian Peasants and Smallholders but this party failed similarly to the Hungarian-minority's Provincial Peasant Party. Like social-democrats, Hungarian agrarians created a separate section within the state-wide Agrarian Party (A3C). Hungarian activism had a stable direction but was not able to become dominant power due to various reasons like land reform or revisionist policies of the Hungarian government.

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) had above-average support among the Hungarian minority. In 1925, party received 37.5% in Kráľovský Chlmec district and 29.7% in Komárno district, compared to the Slovak average of 12–13%.

Hungarian "negativists" were organized in opposition parties represented by right-wing Provincial Christian-Socialist Party (OKSZP) and Hungarian National Party (MNP) (not to be confused with Hungarian National Party above). The OKSZP was supported mainly by the Roman Catholic population, and the MNP by Protestants. The parties differed also by their views on collaboration with the government coalition, the MNP considered collaboration in some periods while the OKSZP was in steadfast opposition and tried to cross ethnic boundaries to gain support from the Slovak population. This attempt was partially successful and the OKSZP had 78 Slovak sections and a Slovak-language journal. Attempts to create a coalition of Hungarian opposition parties with the largest Slovak opposition party – Hlinka's Slovak People's Party (HSĽS) – were unsuccessful due to fear of Hungarian revisionist policy and potential discredit after the affair of Vojtech Tuka who was uncovered as a Hungarian spy.

In 1936, both "negativist" parties united as the United Hungarian Party (EMP) under direct pressure of the Hungarian government and threat of an end to financial support. The party became dominant in 1938 and received more than 80% of Hungarian votes. "Negativistic" parties were considered to be a potential danger to Czechoslovakia and many Hungarian-minority politicians were monitored by police.

Issues in mutual relationships

After World War I, Hungarians found themselves in the difficult position of a "superior" nation which had become a national minority. Dissolution of the historical Kingdom of Hungary was understood as an artificial and violent act, rather than a failure of the anti-national and conservative policy of the Hungarian government. During the whole interwar period, Hungarian society preserved archaic views on the Slovak nation. According to such obsolete ideas, Slovaks were tricked by Czechs, became victims of their power politics and dreamed about returning to a Hungarian state. From these positions, the Hungarian government tried to restore pre-war borders and drove the policy of opposition minority parties.

In Czechoslovakia, peripheral areas like southern Slovakia suffered from a lack of investment and had difficulties recovering from the Great Depression. The Czechoslovak government focused more on stabilization of relationships with Germany and Sudeten Germans while issues of the Hungarian minority had secondary priority. The Hungarians in Slovakia felt aggrieved by the results of Czechoslovak land reform. Regardless of its social and democratizing character, redistribution of former aristocratic lands preferred the majority population, church, and great landowners.

Even if Czechoslovakia officially declared equality of all citizens, members of the Hungarian minority were reluctant to apply for positions in diplomacy, army or state services because of fear that they could be easily misused by foreign intelligence services, especially in time of threat to the country.

Lack of interest for better integration of Hungarian community, the Great Depression and political changes in Europe led to a rise of Hungarian nationalism, pushing their demands in cooperation with German Nazis and other enemies of the Czechoslovak state.

Preparation of aggression against Czechoslovakia

The United Hungarian Party (EMP) led by János Esterházy and Andor Jaross played a fifth column role during the disintegration of Czechoslovakia in late 1930s. Investigation of the Nuremberg trials proved that both Nazi Germany and Horthy Hungary used their minorities for internal disintegration of Czechoslovakia; their goal was not to achieve guarantees of their national rights, but to misuse the topic of national rights against the state whose citizens they were. According to international law, such behaviour belongs to illegal activities against sovereignty of Czechoslovakia and activities of both countries were evaluated as an act against international peace and freedom.

Members of EMP helped to spread anti-Czechoslovak propaganda, while leaders preserved conspiratorial contacts with the Hungarian government and were informed about the preparation of Nazi aggression against Czechoslovakia. Particularly after anschluss of Austria, the party successfully eliminated various Hungarian activist groups.

In the ideal case, revisionist policy coordinated by the Hungarian government should lead to non-violent restoration of borders before the Treaty of Trianon – occupation of the whole Slovakia, or at least to partial territorial reversion. The EMP and Hungarian government had no interest in direct Nazi aggression without participation of Hungary, because it could result in Nazi occupation of Slovakia and jeopardize their territorial claims. The EMP copied policy of Sudeten German Party to some extent. However, even in the time of Czechoslovak crisis, sharper political confrontations were avoided in the ethnically mixed territory. Esterházy was informed about the Sudeten German plan to sabotage negotiations with the Czechoslovak government, and after consultation with the Hungarian government he received instructions to work out on such program which could not be fulfilled.

After the First Vienna Award Hungarians divided into two groups. The majority of the Hungarian population returned to Hungary (503,980 people) and the smaller part (about 67,000 people) remained on non-occupied territory of Czechoslovakia. The First Vienna Award did not satisfy ambitions of leading Hungarian circles and the support for a Greater Hungary grew. This would lead to the annexation of the whole of Slovakia.

Annexation of Southern Slovakia and Subcarpathia (1938–1945)

Most of the Hungarians in Slovakia welcomed the First Vienna Award and occupation of Southern Slovakia which were understood by them as unification of Hungarians into one common national state. Hungarians organized various celebrations and meetings. In Ožďany (Rimavská Sobota District) celebrations had a stormy course. Despite the fact that mass gathering without permit was prohibited and a 20:00 curfew was in place, approximately 400–500 Hungarians met at 21:30 after the announcement of the result of the "arbitration". Police patrols attempted to disperse crowd and one person suffered fatal injury. The mass gathering continued after 22:00 and police injured additional people by shooting and striking with rifles.

Hungary began a systematic assimilation and magyarization policy and forced expulsion of colonists, state employees and Slovak Intelligence from the annexed territory. The Hungarian military administration banned the use of Slovak in administrative contacts and Slovak teachers had to leave schools at all levels.

Following extensive propaganda from the dictatorships – which pretended to be protectors of civic, social and minority rights in Czechoslovakia – Hungary restricted all minorities immediately after the Vienna Award. This had a negative impact on democratically oriented Hungarians in Slovakia, who were subsequently labelled as "Beneš Hungarians" or "communists" when they began to complain of the new conditions.

Mid-war propaganda organized by Hungary did not hesitate to promise "trains of food" for Hungarians (there was no starvation in Czechoslovakia), but after occupation it became clear that Czechoslovakia guaranteed more social rights, more advanced social systems, higher pensions and more job opportunities. Hungarian economists concluded in November 1938 that production on "returned lands" should be restricted to defend the economic interest of the mother country. Instead of positive development, a great majority of companies fell into conditions comparable to the economic crisis at the beginning of the 1930s. After some initial enthusiasm, slogans like Minden drága, visza Prága! (Everything is expensive, back to Prague!) or Minden drága, jobb volt Prága! (Everything is expensive, Prague was better) began to spread across the country.

Positions in the state administration vacated by Czechs and Slovaks were not occupied by local Hungarians, but by state employees from the mother country. This raised protests from the EMP and led to attempts to stop their incoming flow. In August 1939, Andor Jaross asked the Hungarian prime minister to recall at least part of them back to Hungary. Due to different development in Czechoslovakia and Hungary during the previous 20 years, local Hungarians had more democratic spirit and came into conflict with the new administration known by its authoritarian arrogance. In November–December 1939, behaviour toward Hungarians in the annexed territory escalated into official complaint of "Felvidék" MPs in Hungarian parliament.

The Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–1939)

According to the December 1938 census, 67,502 Hungarians remained in the non-annexed part of Slovakia and 17,510 of them had Hungarian citizenship. Hungarians were represented by the Hungarian Party in Slovakia (SMP, Szlovenszkói Magyar Párt; this official name was adopted later in 1940) which formed after dissolution of United Hungarian Party (EMP) in November 1938. The political power in Slovakia was taken up by Hlinka's Slovak People's Party (HSĽS) which started to realize its own totalitarian vision of the state. The ideology of HSĽS distinguished between "good" (autochthonous) minorities (Germans and Hungarians) and "bad" minorities (Czechs and Jews). The government did not allow political organization of "bad" minorities but tolerated existence of the SMP, whose leader János Esterházy became a member of the Slovak Diet. The SMP had little political influence and inclined to cooperation with the stronger German Party in Slovakia (Deutsche Partei in der Slowakei).

By November 1938, Esterházy raised additional demands for extension of Hungarian minority rights. The autonomous Slovak government evaluated the situation in the annexed territory, then did the opposite – binding Hungarian minority rights to the level provided by Hungary which de facto meant their reduction. The applied principle of reciprocity blocked official registration of the SMP and the existence of several Hungarian institutions, as similar organizations were not permitted in Hungary. Moreover, the government banned usage of Hungarian national colours, singing the Hungarian national anthem, did not recognize equality of Hungarian national groups in Bratislava and cancelled a planned office of state secretary for Hungarian minority. The Hungarian government and Esterházy protested against the principle and criticized it as non-constructive.

The First Slovak Republic (1939–1945)

On 14 March 1939, the Slovak Diet declared independence under direct Hitler pressure and a proclaimed threat of Hungarian attack against Slovakia. Destruction of the plurality political system caused a fast decline of minority rights (the German minority preserved a privileged position). Tense relationships between Slovakia and Hungary after the Vienna Award were worsened by a Hungarian attack against Slovakia in March 1939. This aggression combined with violent incidents in the annexed territory caused large anti-Hungarian social mobilization and discrimination. Some of the persecutions were motivated by the reciprocity principle included in the constitution, but persecutions were caused also by Hungarian propaganda demanding occupation of Slovakia, distribution of pamphlets and other propagandist material, oral propaganda and other provocations. Intensive propaganda was used on both sides and led to several anti-Hungarian demonstrations. The harshest repressions included internment in the camp in Ilava and deportations of dozens of Hungarians to Hungary. In June 1940, Slovakia and Hungary reached agreement and stopped deportations of their minorities.

The Hungarian Party did not completely abandon the idea of Greater Hungary, but after stabilization of the state it focused on more-realistic goals. The party had tried to organize the Horthy guard in Bratislava and other towns, but these attempts were discovered and prevented by repressive forces. The party organized various cultural, social and educational activities. Its activities were carefully monitored and restricted because of unsuccessful attempts to establish Slovak political representation in Hungary. The Hungarian Party was officially registered after German diplomatic intervention in November 1941, which also resulted in the Hungarian government permitting the Party of Slovak National unity.

In 1940, after stabilization of the international position of the Slovak state, 53,128 people declared Hungarian nationality and 45,880 of them had Slovak state citizenship. Social structure of the Hungarian minority did not significantly differ from the majority population. 40% of Hungarians worked in agriculture, but there was also a class of rich traders and intelligentsia living in towns. Hungarians owned several important enterprises, especially in central Slovakia. In Bratislava, the Hungarian minority participated in the "aryanization" of Jewish property.

Slovakia preserved 40 Hungarian minority schools, but restricted high schools and did not allow the opening of any new schools. On 20 April 1939, the government banned the largest Hungarian cultural association, SzEMKE, which resulted in an overall decline of activities of the Hungarian minority. Activities of SzEMKE were restored when Hungary permitted the Slovak cultural organization Spolok svätého Vojtecha (St. Vojtech Society). The Hungarian minority had two daily newspapers (Új Hírek and Esti Ujság) and eight local weeklies. All journals, imported press and libraries were controlled by strong censorship.

After negotiations in Salzburg (27–28 July 1940), Alexander Mach held the position of Minister of the Interior and refined the state's approach to its Hungarian minority. Mach ordered all imprisoned Hungarian journalists to be released (later other Hungarians) and disposed chief editor of journal Slovenská pravda because of "stupid texts about Slovak-Hungarian question". Mach emphasized the need of Slovak–Hungarian cooperation and neighbourly relations. In the following period, repressive actions were based almost exclusively on the reciprocity principle.

In comparison with the German minority, political rights and organization of the Hungarian minority was limited. On the other hand, measures against the Hungarian minority never reached the level of persecution against Jews and Gypsies. Expulsion from the country was applied exceptionally and in individual cases, contrary to the expulsion of Czechs.

The aftermath of World War II

In 1945, at the end of World War II, Czechoslovakia was recreated. The strategic goal of the Czechoslovak government was to significantly reduce the size of German and Hungarian minorities and to achieve permanent change in ethnic composition of the state. The preferred means was population transfer. Due to the impossibility of unitary expulsion, Czechoslovakia applied three protocols – Czechoslovak–Hungarian population exchange, "re-Slovakization" and internal transfer of population realized during the deportations of Hungarians to the Czech lands.

Many citizens considered both minorities to be "war criminals", because representatives from those two minorities had supported redrawing the borders of Czechoslovakia before World War II, via the Munich Agreement and the first Vienna Award. In addition, Czechs were suspicious of ethnic-German political activity before the war. They also believed that the presence of so many ethnic Germans had encouraged Nazi Germany in its pan-German visions. In 1945, President Edvard Beneš revoked the citizenship of ethnic Germans and Hungarians by decree No. 33, except for those with an active anti-fascist past (see Beneš Decrees).

Population exchanges

See also: Czechoslovak–Hungarian population exchange and Deportations of Hungarians to the Czech landsImmediately at the end of World War II, some 30,000 Hungarians left the formerly Hungarian re-annexed territories of southern Slovakia. While Czechoslovakia expelled ethnic Germans, the Allies prevented a unilateral expulsion of Hungarians. They did agree to a forced population exchange between Czechoslovakia and Hungary, one which was initially rejected by Hungary. This population exchange proceeded by an agreement whereby 55,400 to 89,700 Hungarians from Slovakia were exchanged for 60,000 to 73,200 Slovaks from Hungary (the exact numbers depend on the source). Slovaks leaving Hungary moved voluntarily, but Czechoslovakia forced Hungarians out of their nation.

After expulsion of the Germans, Czechoslovakia found it had a labour shortage, especially of farmers in the Sudetenland. As a result, the Czechoslovak government deported more than 44,129 Hungarians from Slovakia to the Sudetenland for forced labour between 1945 and 1948. Some 2,489 were resettled voluntarily and received houses, good pay and citizenship in return. Later, from 19 November 1946 to 30 September 1946, the government resettled the remaining 41,666 by force, with the police and army transporting them like "livestock" in rail cars. The Hungarians were required to work as indentured laborers, often offered in village markets to the new Czech settlers of the Sudetenland.

These conditions eased slowly. After a few years, the resettled Hungarians started to return to their homes in Slovakia. By 1948, some 18,536 had returned, causing conflicts over the ownership of their original houses, since Slovak colonists had often taken them over. By 1950, the majority of indentured Hungarians had returned to Slovakia. The status of Hungarians in Czechoslovakia was resolved, and the government again gave citizenship to ethnic Hungarians.

Slovakization

Main article: Slovakization

Materials from Russian archives prove how insistent the Czechoslovak government was on destroying the Hungarian minority in Slovakia. Hungary gave the Slovaks equal rights and demanded that Czechoslovakia offer equivalent rights to Hungarians within its borders.

In the spring and summer of 1945, the Czechoslovak government-in-exile approved a series of decrees that stripped Hungarians of property and all civil rights. In 1946 in Czechoslovakia, the process of "re-Slovakization" was implemented with the objective of eliminating the Magyar nationality. It basically required the acceptance of Slovak nationality. Ethnic Hungarians were pressured to have their nationality officially changed to Slovak, otherwise they were dropped from the pension, social and healthcare system. Since Hungarians in Slovakia were temporarily deprived of many rights at that time (see Beneš decrees), as many as some 400,000 (sources differ) Hungarians applied for, and 344,609 Hungarians received, a re-Slovakization certificate and thereby Czechoslovak citizenship.

After Eduard Beneš was out of office, the next Czechoslovak government issued decree No. 76/1948 on 13 April 1948, allowing those Hungarians still living in Czechoslovakia, to reinstate Czechoslovak citizenship. A year later, Hungarians were allowed to send their children to Hungarian-language schools, which reopened for the first time since 1945. Most re-Slovakized Hungarians gradually re-adopted their Hungarian nationality. As a result, the re-Slovakization commission ceased operations in December 1948.

Despite promises to settle the issue of the Hungarians in Slovakia, Czech and Slovak ruling circles in 1948 maintained the hope that they could deport the Hungarians from Slovakia. According to a 1948 poll conducted among the Slovak population, 55% were for resettlement (deportation) of the Hungarians, 24% said "don't know", and 21% were against. Under slogans related to the struggle with "class enemies", the process of dispersing dense Hungarian settlements continued in 1948 and 1949. By October 1949, the government prepared to deport 600 Hungarian families. Those Hungarians remaining in Slovakia were subjected to heavy pressure to assimilate, including the forced enrolment of Hungarian children in Slovak schools.

Population statistics after World War II

In the 1950 census, the number of Hungarians in Slovakia decreased by 240,000 in comparison to 1930. By the 1961 census it had increased by 164,244 to 518,776. The low number in the 1950 census is likely due to re-Slovakization and population exchanges; the higher number in the 1961 census is likely due to the cancellation of re-Slovakization and natural growth of population (in Slovakia population rose 21%, compared to 46% growth of Hungarians in Slovakia in the same period).

The number of Hungarians in Slovakia increased from 518,782 in 1961 to 567,296 in 1991. The number of self-identified Hungarians in Slovakia decreased between 1991 and 2001, due in part to low birth rates, emigration and introduction of new ethnic categories, such as the Roma. Also, between 1961 and 1991 Hungarians had a significantly lower birth rate than the Slovak majority (which in the meantime had increased from about 3.5 million to 4.5 million), contributing to the drop in the Hungarian percentage of the population.

After the Fall of Communism

After the Velvet Revolution of 1989, the Czech Republic and Slovakia separated peacefully in the Velvet Divorce of 1993. The 1992 Slovak constitution is derived from the concept of the Slovak nation state. The preamble of the Constitution, however, cites Slovaks and ethnic minorities as the constituency. Moreover, the rights of the diverse minorities are protected by the Constitution, the European Convention on Human Rights, and various other legally binding documents. The Party of the Hungarian Coalition (SMK-MKP) was represented in Parliament and was part of the government coalition from 1998 to 2006. Following the independence of Slovakia, the situation of the Hungarian minority worsened, especially under the reign of Slovak Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar (1993 – March 1994 and December 1994 – 1998).

The Constitution also declared that Slovak is the state language. The 1995 Language Law declared that the state language has priority over other languages on the whole territory of the Slovak Republic. The 2009 amendment of the language law restricts the use of minority languages, and extends the obligatory use of the state language (e.g. in communities where the number of minority speakers is less than 20% of the population). Under the 2009 amendment a fine of up to 5000 euros may be imposed on those committing a misdemeanour in relation to the use of the state language.

An official language law required the use of Slovak not only in official communications but also in everyday commerce, in the administration of religious bodies, and even in the realm of what is normally considered private interaction, for example, communications between patient and physician. On 23 January 2007, the local broadcasting committee shut down BBC's radio broadcasting for using English, and cited the language law as the reason.

Especially in Slovakia's ethnic Hungarian areas, critics have attacked the administrative division of Slovakia as a case of gerrymandering, designed so that in all eight regions, Hungarians are in the minority. Under the 1996 law of reorganization, only two districts (Dunajská Streda and Komárno) have a Hungarian-majority population. While also done to maximize the success of the party Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS), the gerrymandering in ethnic Hungarian areas worked to minimize the Hungarians' voting power. In all eight regions, Hungarians are in the minority, though five regions have Hungarian populations within the 10 to 30 per cent range. The Slovak government established new territorial districts from north to south, dividing the Hungarian community into five administrative units, where they became a minority in each administrative unit. The Hungarian community saw a substantial loss of political influence in this gerrymandering.

On 12 March 1997, the Undersecretary of Education sent a circular to the heads of the school districts, ordering that in Hungarian-language schools, Slovak should be taught exclusively by native speakers. The same requirement for native Slovak-language speakers applied to teaching of geography and history in non-Slovak schools. This measure was repealed in 1998 by the Mikuláš Dzurinda government.

In 1995, a so-called Basic Treaty was signed between Hungary and Slovakia, regarded by the US and leading European powers as a pre-condition for these countries to join NATO and the EU. In the basic treaty, Hungary and Slovakia undertook a wide range of legal obligations. This included the acceptance of recommendation 1201 of the Council of Europe, which in its article 11 states:

in the regions where they are in a majority the persons belonging to a national minority shall have the right to have at their disposal appropriate local or autonomous authorities or to have a special status, matching the specific historical and territorial situation and in accordance with the domestic legislation of the state.

After the regions of Slovakia became autonomous in 2002, the MKP was able to take power in the Nitra Region. It became part of the ruling coalition in several other regions. Since the new administrative system was put in place in 1996, the MKP has asked for the creation of a Hungarian-majority Komárno county. Although a territorial unit of the same name existed before 1918, the borders proposed by the MKP are significantly different. The proposed region would encompass a long slice of southern Slovakia, with the explicit aim to create an administrative unit with an ethnic-Hungarian majority. Hungarian-minority politicians and intellectuals are convinced that such an administrative unit is essential for the long-term survival of the Hungarian minority. The Slovak government has so far refused to change the boundaries of the administrative units, and ethnic Hungarians continue as minorities in each.

According to Sabrina P. Ramet, professor of international studies at the University of Washington (referring to the situation under Vladimir Mečiar's administration between 1994 and 1998):

In Central and eastern Europe, there are at least nine zones afflicted by ethnic hatred and intolerance the greatest potential for hostilities can be identified with problems of discrimination against the Hungarian minority in southern Slovakia and Romanian Transylvania. In both cases, national regimes have discriminated against local ethnic Hungarians, depriving them of the right to use their native language for official business; taking step to reduce the use of Hungarian as a language of instruction in local schools, and, in the Slovak case, removing Hungarian street signs from villages populated entirely by Hungarians, replacing them with Slovak-language signs. Slovak authorities even went so far to pass a law requiring that Hungarian woman marrying a Hungarian man add the suffix "-ova" to her name, as is the custom among Slovaks. Hungarians have rebelled against the prospect of such amalgams as "Nagyova", "Bartokova", "Kodályova", and "Petöfiova".

— Sabrina P. Ramet, Whose democracy?

A coalition formed after the parliamentary elections in 2006, which saw the Slovak National Party (SNS) headed by Ján Slota (frequently described as ultra-nationalist right-wing extremist) become a member of the ruling coalition, led by the social-democratic Smer party. After its signing of a coalition treaty with far-right extremist SNS, the Smer's Social-Democratic self-identification was questioned.

In August 2006, a few incidents motivated by ethnic hatred caused diplomatic tensions between Slovakia and Hungary. The mainstream media in these countries blamed Slota's anti-Hungarian statements from the early summer for the worsening ethnic relations. The Party of European Socialists (PES), with which the Smer is affiliated, regards SNS as a party of the racist far-right and expressed grave concern regarding the coalition. The PES suspended Smer's membership on 12 October 2006 and decided to review the situation in June 2007. The decision was then extended until February 2008, when Smer's candidacy was readmitted by PES. On 27 September 2007, the Slovak parliament rejected both principle of collective guilt and attempts to reopen post-war documents which had established the current order.

On 10 April 2008, the Party of the Hungarian Community (SMK-MKP) voted with the governing Smer and SNS, supporting the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon. This may have been the result of an alleged political bargain: Robert Fico promised to change the Slovak education law that would have drastically limited the Hungarian minority's usage of Hungarian-language in educational facilities. The two Slovak opposition parties saw this as a betrayal, because originally the whole Slovak opposition had planned to boycott the vote to protest a new press code that limited the freedom of the press in Slovakia.

In May 2010, the newly appointed second Viktor Orbán cabinet in Hungary initiated a bill on dual citizenship, granting Hungarian passports to members of the Hungarian minority in Slovakia, purportedly aimed at offsetting the harmful effects of the Treaty of Trianon. Though János Martonyi, the new Hungarian foreign minister, visited his Slovak colleague to discuss dual citizenship, Robert Fico stated that Fidesz (Orbán's right-wing party) and the new government did not want to negotiate on the issue, considered a question of national security. Ján Slota's Slovak government member for the SNS feared that Hungary wanted to attack Slovakia and considered the situation as the "beginning of a war conflict". Designate Prime Minister Viktor Orbán laid down firmly that he considered Slovak hysteria as part of the campaign. As a response to the change in Hungarian citizenship law, the National Council of the Slovak Republic approved on 26 May 2010 a law stating that if a Slovak citizen applies for citizenship of another country, then that person will lose their Slovak citizenship.

Language law

Main article: Language law of SlovakiaOn 1 September 2009, over 10,000 Hungarians held demonstrations to protest the new law that limited the use of minority languages in Slovakia. The law called for fines of up to £4,380 for institutions "misusing the Slovak language". There were demonstrations in Dunajská Streda (Hungarian: Dunaszerdahely), Slovakia, in Budapest, Hungary and in Brussels, Belgium.

Culture

- Új Szó – a Hungarian-language daily newspaper published in Bratislava

- Madách – former Hungarian publishing house in Bratislava

- Kalligram – Hungarian publishing house in Bratislava

Education

585 schools in Slovakia, including kindergartens, use Hungarian as the main language of education. Nearly 200 schools use both Slovak and Hungarian. In 2004, the J. Selye University of Komárno was the first state-financed Hungarian-language university to be opened outside of Hungary.

Hungarian political parties

- Under the First Republic of Czechoslovakia (1918–1938):

- Provincial Christian-Socialist Party (Hungarian: Országos Keresztényszocialista Párt, OKSZP)

- Hungarian-German Social Democratic Party (German: Ungarisch-Deutsche Partei der Sozialdemokraten, Hungarian: Magyar és Német Szociál-Demokrata Párt)

- Hungarian National Party (Hungarian: Magyar Nemzeti Párt, MNP)

- Party of the Hungarian Community (Strana maďarskej koalície – Magyar Koalíció Pártja) (SMK-MKP), in the government between 1998 and 2006.

- Most–Híd, in the government between 2010–2012 and 2016–2020.

- Hungarian Christian-Democratic Association (Maďarská kresťanskodemokratická aliancia – Magyar Kereszténydemokrata Szövetség) (MKDA-MKDSZ)

- Alliance (Aliancia - Szövetség)

- Forum

Towns with large Hungarian populations (2001–2021 census)

See also: Language law of SlovakiaNote: only towns (Slovak: mestá) in Slovakia are listed here, villages and rural municipalities are not. According to the Act on the State Language of the Slovak Republic and the Act on the Use of Languages of National Minorities (as amended in 2011), municipalities where at least 15% of the population in two consecutive censuses speak the same minority language, have the right to use their minority language in official communications with local authorities, who are required to respond in that minority language. The government of Slovakia maintains a list of municipalities where this is the case.

| Official name (Slovak) |

Hungarian name |

census 2001 | census 2011 | census 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Hungarians | % Hungarians | % Hungarians | ||

| Čierna nad Tisou | Tiszacsernyő | 60 | 62.27 | 51.39 |

| Dunajská Streda | Dunaszerdahely | 79.75 | 74.53 | 71.93 |

| Fiľakovo | Fülek | 64.40 | 53.54 | 62.88 |

| Gabčíkovo | Bős | 90.4 | 87.88 | 80.6 |

| Galanta | Galánta | 36.80 | 30.54 | 27.72 |

| Hurbanovo | Ógyalla | 50.19 | 41.23 | 40.69 |

| Kolárovo | Gúta | 82.6 | 76.67 | 74.15 |

| Komárno | Komárom | 60.09 | 53.88 | 53.68 |

| Kráľovský Chlmec | Királyhelmec | 76.94 | 73.66 | 72.12 |

| Levice | Léva | 12.23 | 9.19 | 8.27 |

| Lučenec | Losonc | 13.11 | 9.34 | 8.38 |

| Moldava nad Bodvou | Szepsi | 43.6 | 29.63 | 28.11 |

| Nové Zámky | Érsekújvár | 27.52 | 22.36 | 21.44 |

| Rimavská Sobota | Rimaszombat | 35.26 | 22.36 | 30.99 |

| Rožňava | Rozsnyó | 26.8 | 19.84 | 18.77 |

| Šahy | Ipolyság | 62.21 | 57.84 | 57.27 |

| Šaľa | Vágsellye | 17.9 | 14.15 | 13.09 |

| Šamorín | Somorja | 66.63 | 57.43 | 49.55 |

| Senec | Szenc | 22 | 14.47 | 11.37 |

| Sládkovičovo | Diószeg | 38.5 | 31.70 | 25.41 |

| Štúrovo | Párkány | 68.7 | 60.66 | 64.43 |

| Tornaľa | Tornalja | 62.14 | 57.68 | 58.34 |

| Veľké Kapušany | Nagykapos | 56.98 | 59.58 | 52.98 |

| Veľký Meder | Nagymegyer | 84.6 | 75.58 | 76.43 |

| Želiezovce | Zselíz | 51.24 | 48.72 | 41.67 |

Notable Hungarians born in the area of present-day Slovakia

Born before 1918 in the Kingdom of Hungary

- Gyula Andrássy (politician)

- Gyula Andrássy the Younger (politician)

- Bálint Balassi (poet)

- Lajos Batthyány (politician)

- Lujza Blaha (actress, "the nightingale of the nation")

- Ernő Dohnányi (conductor, composer, pianist)

- Elizabeth of Hungary

- Béla Gerster (engineer, canal architect)

- Artúr Görgey (military leader)

- András Hadik

- Béla Hamvas (philosopher)

- Mór Jókai (writer)

- Lajos Kassák (poet, painter, typographer, graphic artist)

- Domokos Kosáry (historian, president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences)

- Peter Lorre (Hollywood actor)

- Imre Madách (poet)

- Pál Maléter (military leader of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution)

- Sándor Márai (writer)

- Kálmán Mikszáth (writer)

- Francis II Rákóczi (prince, military leader, freedom fighter)

- József Révay (philosopher, Olympic champion)

- Franz Schmidt (composer)

- Mihály Tompa (poet)

- Imre Thököly (prince, military leader)

- János Zsámboky (16th-century humanist)

Born after 1918 in Czechoslovakia

- Balázs Borbély (sportsman)

- Imrich Bugár Imre Bugár (sportsman)

- George Feher György Fehér (biophysicist)

- Koloman Gögh Kálmán Gögh (sportsman)

- Vica Kerekes (actress)

- Szilárd Németh (sportsman)

- Attila Pinte (sportsman)

- Alexander Pituk Sándor Pituk (sportsman)

- Tamás Priskin (sportsman)

- Richard Réti (sportsman)

- Attila Végh (sportsman)

Born in Czechoslovakia, career in Hungary

- Attila Kaszás

- Alexandra Borbély (actress)

Hungarian politicians in Slovakia

- József Berényi – chairman of Party of the Hungarian Coalition

- Edit Bauer – Member of the European Parliament

- Edita Pfundtner

- Béla Bugár – former chairman of Party of the Hungarian Coalition

- Pál Csáky – former chairman of Party of the Hungarian Coalition

- Miklós Duray

- Count János Esterházy – World War II politician

- László Gyurovszky

- Ľudovít Ódor − Member of the European Parliament, economist, former Deputy Governor of the National Bank of Slovakia, former Slovak prime minister

See also

- 2006 Slovak–Hungarian diplomatic affairs

- Csángó

- Demographics of Slovakia

- Forum Minority Research Institute

- Hungarian minority in Romania

- Hungarians in Vojvodina

- Hungary–Slovakia relations

- Magyarization

- Slovakization

- Slovaks in Hungary

- Székelys

- Székelys of Bukovina

- Ethnic minorities in Czechoslovakia

- Magyaron

References

Notes

- Holka Chudzikova, Alena (29 March 2022). "Data from census have confirmed that an exclusive national identity is a myth. This should also translate into the laws concerning national minorities". Minority policy in Slovakia. ISSN 2729-8663. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- "Number of population by mother tongue in the Slovak Republic at 1. 1. 2021". SODB2021 – The 2021 Population and Housing Census. Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- Ian Dear; Michael Richard Daniell Foot (2001). The Oxford companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- C.A. Macartney (1937). Hungary and her successors – The Treaty of Trianon and Its Consequences 1919–1937. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821451-0.

- Richard Bernstein (9 August 2003). "East on the Danube: Hungary's Tragic Century". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- Benža, Mojmír (9 October 2017). "Maďari na Slovensku – Centrum pre tradičnú ľudovú kultúru". Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- Deák 2009, p. 10.

- Deák 2009, p. 12.

- ^ History, the development of the contact situation and demographic data. gramma.sk

- Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 98.

- kovacs-4.qxd Archived 23 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- HamvasBéla.org

- Magyarország a XX. században / Szociálpolitika. oszk.hu

- Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 157.

- Béla László (2004). "Maďarské národnostné školstvo". In József Fazekas; Péter Huncík (eds.). Madari na Slovensku (1989–2004) / Magyarok Szlovákiában (1989–2004) (PDF). Šamorín: Fórum inštitút pre výskum menšín. ISBN 978-80-89249-16-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 167.

- Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 188.

- ^ Marko, Martinický: Slovensko-maďarské vzťahy. 1995

- Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 179.

- Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 189.

- Zemko & Bystrický 2004.

- ^ Simon 2009, p. 22.

- Simon 2009, p. 24.

- Ďurkovská, Gabzdilová & Olejník 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Ladislav Deák. "Slovensko-maďarské vzťahy očami historika na začiatku 21. storočia" [Slovakia-Hungarian relations through the eyes of a historian in the early 21st century]. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 459.

- Pástor 2011, p. 86.

- Beňo 2008, p. 85.

- Deák 1995, p. 13.

- Zemko & Bystrický 2004, p. 210.

- Pástor 2011, p. 94.

- Vrábel 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 483.

- Vrábel 2011, p. 30.

- Sabol 2011, p. 231.

- Sabol 2011, p. 232.

- Mitáč 2011, p. 138.

- ^ Tilkovszky 1972.

- Kmeť 2012, p. 34.

- Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 496.

- Ferenčuhová & Zemko 2012, p. 495.

- Deák 1990, p. 140.

- ^ Baka 2010, p. 245.

- ^ Baka 2010, p. 247.

- Hetényi 2007, p. 100.

- ^ Hetényi 2007, p. 95.

- Hetényi 2007, p. 96.

- ^ Baka 2010, p. 246.

- Hetényi 2007, p. 111.

- Bobák, Ján: Maďarská otázka v Česko-Slovensku. 1996

- Erika Harris (2003) Management of the Hungarian Issue in Slovak Politics: Europeanisation and the Evolution of National Identities Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. University of Leeds

- J. Zvara (1969) Maďarská menšina na Slovensku po roku 1945.

- Józsa Hévizi; Thomas J. DeKornfeld (2005). Autonomies in Hungary and Europe: a comparative study. Corvinus Society. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-882785-17-9.

- Eleonore C. M. Breuning; Dr. Jill Lewis; Gareth Pritchard (2005). Power and the People: A Social History of Central European Politics, 1945–56. Manchester University Press. pp. 140–. ISBN 978-0-7190-7069-3.

- ^ Anna Fenyvesi (1 January 2005). Hungarian Language Contact Outside Hungary: Studies on Hungarian as a Minority Language. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 50–. ISBN 90-272-1858-7.

- Rieber, p. 84

- Rieber, p. 91

- Michael Mandelbaum (2000). The New European Diasporas: National Minorities and Conflict in Eastern Europe. Council on Foreign Relations. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-87609-257-6.

- ^ "Human Rights For Minorities In Central Europe: Ethnic Cleansing In Post World War II Czechoslovakia: The Presidential Decrees Of Edward Beneš, 1945–1948". migrationeducation.de. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009.

- Szegő Iván Miklós (29 September 2007) "Tudomány – A magyarok kitelepítése: mézesmadzag a szlovákoknak". index.hu

- Rieber, p. 92

- ^ Rieber, p. 93

- Hungarian Nation in Slovakia|Slovakia Archived 3 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. slovakia.org

- "BBC's radio license yanked for use of English". The Slovak Spectator. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ O'Dwyer, Conor : Runaway State-building, p. 113 online

- Minton F. Goldman: Slovakia since independence, p. 125. online

- "Recommendation 1201 (1993) - Additional protocol on the rights of minorities to the European Convention on Human Rights". Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. 1993. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (1997). "Eastern Europe's Painful Transformation". Whose democracy?: nationalism, religion, and the doctrine of collective rights in post-1989 Eastern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-8476-8324-6. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ New Slovak Government Embraces Ultra-Nationalists, Excludes Hungarian Coalition Party Archived 5 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine HRF Alert: "Hungarians are the cancer of the Slovak nation, without delay we need to remove them from the body of the nation." (Új Szó, 15 April 2005)

- New Slovak PM promises to punish extremism, pledges to soften economic reform by previous government. Associated Press. 7 September 2006

- Country reports. Antisemitism and racism in Slovakia. The Steven Roth Institute, Israel

- "SMK will vote for Lisbon Treaty, to SDKÚ & KDH dismay". Slovak Spectator. 10 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ "Csáky "tehénszar" helyett már "tökös gyerek" – Fico "aljas ajánlata"" (in Hungarian). Hírszerző. 14 April 2008. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- "Készek tüntetni a szlovákiai magyarok" (in Hungarian). Hírszerző. 26 March 2008. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- "Fico's post-Press Code era has begun". The Slovak Spectator. 14 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- "Protests over Slovak language law". BBC News. 2 September 2009

- World in brief. morningstaronline.co.uk. 2 September 2009

- Új Szó

- "Kalligram – Hungarian publishing house in Bratislava". Archived from the original on 8 August 2006. Retrieved 3 September 2006.

- ^ Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (ACFC) (2 February 2022). "Fifth Opinion on the Slovak Republic". Secretariat of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM). Retrieved 21 March 2023.

"175. According to the Act on the State Language of the Slovak Republic and the Act on the Use of Languages of National Minorities, minority languages may be used in private without limitations, while official use of minority languages in contacts with local authorities is regulated according to set thresholds (previously 20% and now 15%). The list of municipalities where the right to use the language of a national minority in official communication can be applied will be updated, once the results of the 2021 census are known. (...) By Act No. 204/2011, amending the Act on the Use of Languages of National Minorities, citizens of the Slovak Republic have the right to use the language of a national minority in municipalities where citizens of national minorities make up at least 15% of the population according to two consecutive population censuses. However, this will only occur after the results of the 2021 census have been announced.

- "Demographic data from population and housing censuses in Slovakia". Sodb.infostat.sk. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- "Development of prices in production area in July 2017" (PDF). Portal.statistics.sk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- "Ethnic composition of Slovakia 2021". Retrieved 18 March 2023.

Bibliography

- Alfred J. Rieber (2000). Forced Migration in Central and Eastern Europe, 1939–1950. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5132-3.

- Simon, Attila (2009). "Zabudnutí aktivisti. Príspevok k dejinám maďarských politických strán v medzivojnovom období" [Forgotten activists. A contribution to the history of Hungarian political parties in the inter-war period.]. Historický časopis (in Slovak). 57 (3).

- Pástor, Zoltán (2011). Slováci a Maďari [Slovaks and Hungarians] (in Slovak). Matica slovenská. ISBN 978-80-8128-004-7.

- Zemko, Milan; Bystrický, Valerián (2004). Slovensko v Československu 1918 – 1939 [Slovakia in Czechoslovakia 1918 – 1939] (in Slovak). Veda. ISBN 80-224-0795-X.

- Ferenčuhová, Bohumila; Zemko, Milan (2012). V medzivojnovom Československu 1918–1939 [In inter-war Czechoslovakia 1918–1939] (in Slovak). Veda. ISBN 978-80-224-1199-8.

- Ďurkovská, Mária; Gabzdilová, Soňa; Olejník, Milan (2012). Maďarské politické strany (Krajinská kresťansko-socialistická strana, Maďarská národná strana) na Slovensku v rokoch 1929 – 1936. Dokumenty [Hungarian political parties (Provincial Christian-Socialist Party, Hungarian National Party) in Slovakia between 1929 – 1936. Documents.] (PDF) (in Slovak). Košice: Spoločenskovedný ústav SAV. ISBN 978-80-89524-09-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014.

- Deák, Ladislav (1990). Slovensko v politike Maďarska v rokoch 1938–1939 [Slovakia in the policy of Hungary 1938–1945]. Bratislava: Veda. ISBN 80-224-0169-2.

- Deák, Ladislav (1995). Political profile of János Esterházy. Bratislava: Kubko Goral. ISBN 80-967427-0-1.

- Deák, Ladislav (2009). "O hodnovernosti uhorskej národnostnej štatistiky z roku 1910." [About reliability of the Hungarian national statistics from 1910.]. In Doruľa, Ján (ed.). Pohľady do problematiky slovensko-maďarských vzťahov. Bratislava: Slavistický ústav Jána Stanislava SAV. ISBN 978-80-967427-0-7.

- Tilkovszky, Loránt (1972). Južné Slovensko v rokoch 1938–1945 [Southern Slovakia during the years 1938–1945] (in Slovak). Bratislava: Vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied.

- Mitáč, Ján (2011). "Krvavý incident v Šuranoch na Vianoce 1938 v spomienkach obyvateľov mesta Šurany" [Bloody incident in Šurany on Christmas 1938 in the memories of citizens of Šurany]. In Mitáč, Ján (ed.). Juh Slovenska po Viedeňskej arbitráži 1938 – 1945 [Southern Slovakia after the First Vienna Award 1938 – 1945] (in Slovak). Bratislava: Ústav pamäti národa. ISBN 978-80-89335-45-9.

- Vrábel, Ferdinad (2011). "Náprava "krív" z Trianonu? Niekoľko epizód z obsadzovania južného Slovenska maďarským vojskom z v novembri 1938" [Correction od "injustices" of Trianon? Several episodes from occupation by southern Slovakia by Hungarian army in November 1938]. In Mitáč, Ján (ed.). Juh Slovenska po Viedeňskej arbitráži 1938 – 1945 [Southern Slovakia after the First Vienna Award 1938 – 1945] (in Slovak). Bratislava: Ústav pamäti národa. ISBN 978-80-89335-45-9.

- Sabol, Miroslav (2011). "Dopad Viedenskej arbitráže na poľnohospodárstvo, priemysel a infraštruktúru na južnom Slovensku" [Impact of the Vienna Award on agriculture, industry and infrastructure on Southern Slovakia]. In Mitáč, Ján (ed.). Juh Slovenska po Viedeňskej arbitráži 1938 – 1945 [Southern Slovakia after the First Vienna Award 1938 – 1945] (in Slovak). Bratislava: Ústav pamäti národa. ISBN 978-80-89335-45-9.

- Kmeť, Miroslav (March 2012). "Maďari na Slovensku, Slováci v Maďarsku. Národnosti na oboch stranách hraníc v rokoch 1938–1939". Historická revue (in Slovak). 3.

- Baka, Igor (2010). Politický režim a režim Slovenskej republiky v rokoch 1939–1940 (in Slovak). Bratislava: Ševt. ISBN 978-80-8106-009-0.

- Hetényi, Martin (2007). "Postavenie maďarskej menšiny na Slovnsku v rokoch 1939–1940." [Position of Hungarian minority in Slovakia in years 1939–1940.]. In Pekár, Martin; Pavlovič, Richard (eds.). Slovenské republika očami mladých historikov VI. Slovenská republika medzi 14. marcom a salzburskými rokovaniami (in Slovak). Prešov: Universum. ISBN 978-80-8068-669-7.

Further reading

- Gyurcsik, Iván; James Satterwhite (September 1996). "The Hungarians in Slovakia". Nationalities Papers. 24 (3): 509–524. doi:10.1080/00905999608408463. S2CID 154468741.

- Paul, Ellen L. (December 2003). "Perception vs. Reality: Slovak Views of the Hungarian Minority in Slovakia". Nationalities Papers. 31 (4): 485–493. doi:10.1080/0090599032000152951. S2CID 129372910.

- Beňo, Jozef (2008). "Medzinárodno-právne súvislosti Viedenskej arbitráže" [International law context of the Vienna Arbitration]. In Šmihula, Daniel (ed.). Viedenská arbitráž v roku 1938 a jej európske súvislosti [Vienna Award in 1938 and its European context] (in Slovak). Bratislava: Ševt. ISBN 978-80-8106-009-0.

External links

| Hungarian diaspora | |

|---|---|

| Africa | |

| Europe | |

| Americas | |

| Oceania | |

| Ethnic and national minorities in Czechoslovakia | |

|---|---|

| Officially recognized | |

| Other | |