Medical condition

| Ehlers–Danlos syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Individual with classical EDS displaying skin hyperelasticity | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Overly flexible joints, stretchy skin, abnormal scar formation |

| Complications | Aortic dissection, joint dislocations, osteoarthritis, amplified musculoskeletal pain syndrome |

| Usual onset | Childhood or adolescence, depending on type |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | Hypermobile, classic, vascular, kyphoscoliosis, arthrochalasia, dermatosparaxis, brittle cornea syndrome, others |

| Causes | Genetic |

| Risk factors | Family history |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing, physical examination |

| Differential diagnosis | Marfan syndrome, cutis laxa syndrome, familial joint hypermobility syndrome, Loeys–Dietz syndrome, hypermobility spectrum disorder |

| Treatment | Supportive |

| Prognosis | Depends on specific disorder |

| Frequency | 1 in 5,000 |

Ehlers–Danlos syndromes (EDS) are a group of 13 genetic connective-tissue disorders. Symptoms often include loose joints, joint pain, stretchy velvety skin, and abnormal scar formation. These may be noticed at birth or in early childhood. Complications may include aortic dissection, joint dislocations, scoliosis, chronic pain, or early osteoarthritis. The current classification was last updated in 2017, when a number of rarer forms of EDS were added.

EDS occurs due to mutations in one or more particular genes—there are 19 genes that can contribute to the condition. The specific gene affected determines the type of EDS, though the genetic causes of hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hEDS) are still unknown. Some cases result from a new variation occurring during early development, while others are inherited in an autosomal dominant or recessive manner. Typically, these variations result in defects in the structure or processing of the protein collagen or tenascin.

Diagnosis is often based on symptoms and confirmed by genetic testing or skin biopsy, particularly with hEDS, but people may initially be misdiagnosed with hypochondriasis, depression, or myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Genetic testing can be used to confirm all other types of EDS.

A cure is not yet known, and treatment is supportive in nature. Physical therapy and bracing may help strengthen muscles and support joints. Several medications can help alleviate symptoms of EDS such as pain and blood pressure drugs, which reduce joint pain and complications caused by blood vessel weakness. Some forms of EDS result in a normal life expectancy, but those that affect blood vessels generally decrease it. All forms of EDS can result in fatal outcomes for some patients.

While hEDS affects at least one in 5,000 people globally, other types occur at lower frequencies. The prognosis depends on the specific disorder. Excess mobility was first described by Hippocrates in 400 BC. The syndromes are named after two physicians, Edvard Ehlers and Henri-Alexandre Danlos, who described them at the turn of the 20th century.

Types

In 2017, 13 subtypes of EDS were classified using specific diagnostic criteria. According to the Ehlers–Danlos Society, the syndromes can also be grouped by the symptoms determined by specific gene mutations. Group A disorders are those that affect primary collagen structure and processing. Group B disorders affect collagen folding and crosslinking. Group C are disorders of structure and function of myomatrix. Group D disorders are those that affect glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis. Group E disorders are characterized by defects in the complement pathway. Group F are disorders of intracellular processes, and Group G is considered to be unresolved forms of EDS.

Hypermobile EDS (hEDS)

Hypermobile EDS (hEDS, formerly categorized as type 3) is mainly characterized by hypermobility that affects both large and small joints. It may lead to frequent joint subluxations (partial dislocations) and dislocations. In general, people with this variant have skin that is soft, smooth, and velvety and bruises easily, and may have chronic muscle and/or bone pain. It affects the skin less than other forms. It has no available genetic test. hEDS is the most common of the 19 types of connective tissue disorders. Since no genetic test exists, providers have to diagnose hEDS based on what they know about the condition and the patient's physical attributes. Other than the general signs, attributes can include faulty connective tissues throughout the body, musculoskeletal issues, and family history. Along with these general signs and side effects, patients can have trouble healing.

Pregnant individuals who have hEDS are at an increased risk for complications. Some possible complications are pre-labor rupture of membranes, a drop in blood pressure with anesthesia, precipitated birth (very fast, active labor), malposition of the fetus, and increased bleeding. Individuals with hEDS may run the risk of falling, postpartum depression (more than the general population), and slow healing from the birthing process.

The Medical University of South Carolina discovered a gene variant common with hEDS patients.

Genetics of hypermobile EDS

While 12 of the 13 subtypes of EDS have genetic variations that can be tested for by genetic testing, there is no known genetic cause of hEDS. Recently, several labs and research initiatives have been attempting to uncover a potential hEDS gene. In 2018, the Ehlers–Danlos Society began the Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos Genetic Evaluation (HEDGE) study. The ongoing study has screened over 1,000 people who have been diagnosed with hEDS by the 2017 criteria to evaluate their genome for a common mutation. To date, 200 people with hEDS have had whole genome sequencing, and 500 have had whole exome sequencing; this study aims to increase those numbers significantly.

Promising outcomes of this increased screening have been reported by the Norris Lab, led by Russell Norris, in the Department of Regenerative Medicine and Cell Biology at Medical University of South Carolina. Using CRISPR Cas-9 mediated genome editing on mouse models of the disease, the lab has recently identified a "very strong candidate gene" for hEDS. This finding, and a greater understanding of cardiac complications associated with the majority of EDS subtypes, has led to the development of multiple druggable pathways involved in aortic and mitral valve diseases. While this candidate gene has not been publicly identified, the Norris lab has conducted several studies involving small population genome sequencing and come up with a working list of possible hEDS genes. A mutation in COL3A1 in a single family with autosomal dominant hEDS phenotype was found to cause reduced collagen secretion and an over-modification of collagen. In 35 families, copy number alterations in TPSAB1, encoding alpha-tryptase, were associated with increased basal serum tryptase levels, associated with autonomic dysfunction, gastrointestinal disorders, allergic and cutaneous symptoms, and connective tissue abnormalities, all concurrent with hEDS phenotype.

Another way the Norris lab is attempting to find this gene is by looking at genes involved in the formation of the aorta and mitral valves, as these valves are often prolapsed or malformed as a symptom of EDS. Because hEDS is such a complex, multi-organ disease, focusing on one hallmark trait has proven successful. One gene found this way is DZIP1, which regulates cardiac valve development in mammals through a CBY1-beta-catenin mechanism. Mutations at this gene affect the beta-catenin cascade involved in development, causing malformation of the extracellular matrix, resulting in loss of collagen. A lack of collagen here is consistent with hEDS and explains the "floppy" mitral and aortic valve heart defects. A second genetic study specific to mitral valve prolapse focused on the PDGF signaling pathway, which is involved in growth factor ligands and receptor isoforms. Mutations in this pathway affect the ability to localize cilia in various cell types, including cardiac cells. With the resulting ciliopathies, structures such as the cardiac outflow tract, heart tube assembly, and cardiac fusion are limited and/or damaged.

Classical EDS (cEDS)

Classical EDS is characterized by extremely elastic skin that is fragile and bruises easily and hypermobility of the joints. Molluscoid pseudotumors (calcified hematomas that occur over pressure points) and spheroids (cysts that contain fat occurring over forearms and shins) are also often seen. A side complication of the hyperelasticity presented in many EDS cases makes wounds closing on their own more difficult. Sometimes, motor development is delayed and hypotonia occurs. The variation causing this type of EDS is in the genes COL5A2, COL5A1, and less frequently COL1A1. It involves the skin more than hEDS. In classical EDS, large variation in symptom presentation is seen. Because of this variance, EDS has often been underdiagnosed. Without genetic testing, healthcare professionals may be able to provide a provisional diagnosis based on careful examination of the mouth, skin, and bones, as well as by neurological assessment.

A good way to begin the diagnostic process is by reviewing a person's family history. EDS is an autosomal dominant condition, so is often inherited from parents. Genetic testing remains the most reliable way to diagnose EDS. No cure for type 1 EDS has been found, but a course of non-weight-bearing exercise can help with muscular tension, which can help correct some EDS symptoms. Anti-inflammatory drugs and lifestyle changes can help with joint pain. Lifestyle choices should also be made with children who have EDS to try to prevent wounds to the skin. Protective garments can help with this. In a wound, deep stitches are often used and left in place for longer than normal.

Vascular EDS (vEDS)

Vascular EDS (formerly categorized as type 4) is identified by skin that is thin, translucent, extremely fragile, and bruises easily. It is also characterized by fragile blood vessels and organs that can easily rupture. Affected people are frequently short, and have thin scalp hair. It also has characteristic facial features, including large eyes, an undersized chin, sunken cheeks, a thin nose and lips, and ears without lobes. Joint hypermobility is present, but generally confined to the small joints (fingers, toes). Other common features include club foot, tendon and/or muscle rupture, acrogeria (premature aging of the skin of the hands and feet), early-onset varicose veins, pneumothorax (collapse of a lung), the recession of the gums, and a decreased amount of fat under the skin. It can be caused by the variations in the COL3A1 gene. Rarely, COL1A1 variations can also cause it.

Kyphoscoliosis EDS (kEDS)

Kyphoscoliosis EDS (formerly categorized as type 6) is associated with severe hypotonia at birth, delayed motor development, progressive scoliosis (present from birth), and scleral fragility. People may also have easy bruising, fragile arteries that are prone to rupture, unusually small corneas, and osteopenia (low bone density). Other common features include a "marfanoid habitus" characterized by long, slender fingers (arachnodactyly), unusually long limbs, and a sunken chest (pectus excavatum) or protruding chest (pectus carinatum). It can be caused by variations in the gene PLOD1, or rarely, in the FKBP14 gene.

Arthrochalasia EDS (aEDS)

Arthrochalasia EDS (formerly categorized as types 7A and B) is characterized by severe joint hypermobility and congenital hip dislocation. Other common features include fragile, elastic skin with easy bruising, hypotonia, kyphoscoliosis (kyphosis and scoliosis), and mild osteopenia. Type-I collagen is usually affected. It is very rare, with about 30 cases reported. It is more severe than the hypermobility type. Variations in the genes COL1A1 and COL1A2 cause it.

Dermatosparaxis EDS (dEDS)

Dermatosparaxis EDS (formerly categorized as type 7C) is associated with extremely fragile skin leading to severe bruising and scarring; saggy, redundant skin, especially on the face; hypermobility ranging from mild to serious; and hernias. Variations in the ADAMTS2 gene cause it. It is extremely rare, with around 11 cases reported worldwide.

Brittle-cornea syndrome (BCS)

Brittle-cornea syndrome is characterized by the progressive thinning of the cornea, early-onset progressive keratoglobus or keratoconus, nearsightedness, hearing loss, and blue sclerae. Classic symptoms, such as hypermobile joints and hyperelastic skin, are also seen often. It has two types. Type 1 occurs due to variations in the ZNF469 gene. Type 2 is due to variations in the PRDM5 gene.

Classical-like EDS (clEDS)

Classical-like EDS is characterized by skin hyperextensibility with velvety skin texture and absence of atrophic scarring, generalized joint hypermobility with or without recurrent dislocations (most often shoulder and ankle), and easily bruised skin or spontaneous ecchymoses (discolorations of the skin resulting from bleeding underneath). It can be caused by variations in the TNXB gene.

Spondylodysplastic EDS (spEDS)

Spondylodysplastic EDS is characterized by short stature (progressive in childhood), muscle hypotonia (ranging from severe congenital to mild later-onset), and bowing of limbs. It can be caused by variations in both copies of the B4GALT7 gene. Other cases can be caused by variations in the B3GALT6 gene. People with variations in this gene can have kyphoscoliosis, tapered fingers, osteoporosis, aortic aneurysms, and problems with the lungs. Other cases can be caused by the SLC39A13 gene. Those with variations in this gene have protuberant eyes, wrinkled palms of the hands, tapering fingers, and distal joint hypermobility.

Musculocontractural EDS (mcEDS)

Musculocontractural EDS is characterized by congenital multiple contractures, characteristically adduction-flexion contractures and/or talipes equinovarus (clubfoot), characteristic craniofacial features, which are evident at birth or in early infancy, and skin features such as skin hyperextensibility, bruising, skin fragility with atrophic scars, and increased palmar wrinkling. It can be caused by variations in the CHST14 gene. Some other cases can be caused by variations in the DSE gene.

As of 2021, 48 individuals have been reported to have mcEDS-CHST14, while 8 individuals have mcEDS-DSE.

Myopathic EDS (mEDS)

Bethlem myopathy 2, formally known as Myopathic EDS (mEDS), is characterized by three major criteria: congenital muscle hypotonia and/or muscle atrophy that improves with age, proximal joint contractures of the knee, hip, and elbow, and hypermobility of distal joints (ankles, wrists, feet, and hands). Four minor criteria may also contribute to a diagnosis of mEDS. This disorder can be inherited through either an autosomal dominant or an autosomal recessive pattern. Molecular testing must be completed to verify that mutations in the COL12A1 gene are present; if not, other collagen-type myopathies should be considered.

Periodontal EDS (pEDS)

Periodontal EDS (pEDS) is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by four major criteria of severe and intractable periodontitis of early-onset (childhood or adolescence), lack of attached gingiva, pretibial plaques, and family history of a first-degree relative who meets clinical criteria. Eight minor criteria may also contribute to the diagnosis of pEDS. Molecular testing may reveal mutations in C1R or C1S genes affecting the C1r protein.

Cardiac-valvular EDS (cvEDS)

Cardiac-valvular EDS (cvEDS) is characterized by three major criteria: severe progressive cardiac-valvular problems (affecting aortic and mitral valves), skin problems such as hyperextensibility, atrophic scarring, thin skin, and easy bruising, and joint hypermobility (generalized or restricted to small joints). Four minor criteria may aid in the diagnosis of cvEDS. cvEDS is an autosomal recessive disorder, inherited through variation in both alleles of the gene COL1A2.

Signs and symptoms

This group of disorders affects connective tissues across the body, with symptoms most typically present in the joints, skin, and blood vessels. However, as connective tissue is found throughout the body, EDS may result in an array of unexpected impacts with any degree of severity, and the condition is not limited to joints, skin, and blood vessels. Effects may range from mildly loose joints to life-threatening cardiovascular complications. Due to the diversity of subtypes within the EDS family, symptoms may vary widely between individuals diagnosed with EDS.

Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal symptoms include hyperflexible joints that are unstable and prone to sprain, dislocation, subluxation, and hyperextension. As a result of frequent tissue injury, there can be an early onset of advanced osteoarthritis, chronic degenerative joint disease, swan-neck deformity of the fingers, and Boutonniere deformity of the fingers. Tendon and ligament laxity offer minuscule protection from tearing in muscles and tendons, but these problems still persist.

Deformities of the spine, such as scoliosis (curvature of the spine), kyphosis (a thoracic hump), tethered spinal cord syndrome, craniocervical instability (CCI), and atlantoaxial instability may also be present. Osteoporosis and osteopenia are also associated with EDS and symptomatic joint hypermobility

There can also be myalgia (muscle pain) and arthralgia (joint pain), which may be severe and disabling. Trendelenburg's sign is often seen, which means that when standing on one leg, the pelvis drops on the other side. Osgood–Schlatter disease, a painful lump on the knee, is common as well. In infants, walking can be delayed (beyond 18 months of age), and bottom-shuffling instead of crawling occurs.

-

Individual with EDS showing hypermobile fingers, including the "swan-neck" malformation on the 2nd–5th digits, and a hypermobile thumb

Individual with EDS showing hypermobile fingers, including the "swan-neck" malformation on the 2nd–5th digits, and a hypermobile thumb

-

Individual with EDS displaying hypermobile thumb

Individual with EDS displaying hypermobile thumb

-

Individual with EDS displaying hypermobile metacarpophalangeal joints

Individual with EDS displaying hypermobile metacarpophalangeal joints

-

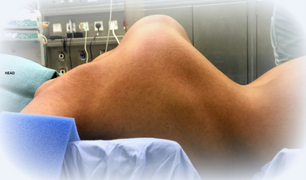

Kyphoscoliosis of the back of someone with kyphoscoliosis EDS

Kyphoscoliosis of the back of someone with kyphoscoliosis EDS

-

Severe joint hypermobility in a girl with EDS arthrochalasia type

Severe joint hypermobility in a girl with EDS arthrochalasia type

-

Male, late adolescent, with hypermobile type

Male, late adolescent, with hypermobile type

Skin

The weak connective tissue causes abnormal skin. This may present as stretchy or in other types simply be velvet soft. In all types, some increased fragility occurs, but the degree varies depending on the underlying subtype. The skin may tear and bruise easily, and may heal with abnormal atrophic scars; atrophic scars that look like cigarette paper are a sign seen including in those whose skin might appear otherwise normal. In some subtypes, though not the hypermobile subtype, redundant skin folds occur, especially on the eyelids. Redundant skin folds are areas of excess skin lying in folds.

Other skin symptoms include molluscoid pseudotumors, especially on pressure points, petechiae, subcutaneous spheroids, livedo reticularis; piezogenic papules are less common. In vascular EDS, skin can also be thin and translucent. In dermatosparaxis EDS, the skin is extremely fragile and saggy.

-

Atrophic scar in a case of EDS

Atrophic scar in a case of EDS

-

Translucent skin in vascular EDS

Translucent skin in vascular EDS

-

Individual with EDS displaying skin hyperelasticity

Individual with EDS displaying skin hyperelasticity

-

Piezogenic papules on the heel of an individual with hypermobile EDS

Piezogenic papules on the heel of an individual with hypermobile EDS

-

Skin hyperelasticity in the wrist

Skin hyperelasticity in the wrist

Cardiovascular

- Thoracic outlet syndrome

- Arterial rupture

- Valvular heart disease, such as mitral valve prolapse, creates an increased risk for infective endocarditis during surgery. This may progress to a life-threatening degree. Heart conduction abnormalities have been found in those with hypermobility form of EDS.

- Dilation or rupture (aneurysm) of ascending aorta

- Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- Raynaud's phenomenon

- Varicose veins

- Heart murmur

- Heart conduction abnormalities

Urogynaecological

Weakened connective tissues can lead to pelvic organ prolapse in female patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Patients may also experience voiding difficulties, frequent urinary tract infections, and incontinence due to structural abnormalities. Pelvic girdle pain is also frequently reported.

Menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia are common symptoms associated with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and are often mistaken for endometriosis. Excessive menstrual bleeding can sometimes be attributed to inappropriate platelet aggregation, but faulty collagen leads to weakened capillary walls which increase the likelihood of hemorrhage.

In cases of pregnancy, patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome are more likely to experience complications during parturition. Post-partum hemorrhage and maternal injury such as sporadic pelvic displacement, hip dislocation, torn and stretched ligaments, and skin tearing can all be linked to altered structure of connective tissues.

Gastrointestinal

Research suggests a correlation between connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and both structural and functional problems within the gastrointestinal tract.

Inflammatory problems

High incidences of coexisting inflammatory disorders suggest a correlation between connective tissue disorders and the development of such aforementioned conditions. Inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and celiac disease are more common in EDS patients when compared to control groups. Of note, patients who are already diagnosed with an inflammatory bowel disorder are not necessarily likely to develop symptoms of a connective tissue disorder, as the two have separate but not totally confounding etiologies. Eosinophilic esophagitis, an inflammatory condition characterized by allergic-type reactions to various foods and chemicals and extensive esophageal remodeling, is eight times more likely in patients with connective tissue disorders when compared to patients without.

Functional problems

Functionally, small bowel dysmotility, delayed gastric emptying and delayed colonic transit are commonly related to EDS. These changes in transit speeds within the gastrointestinal system can cause a host of symptoms, including but not limited to abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, reflux symptoms, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea.

Some studies also suggest problems with the liver, which is in large part responsible for bilirubin conjugation. Although research in this area is sparse, patients with joint hypermobility were found to have higher rates of indirect hyperbilirubinemia than control groups.

Structural problems

Structurally, changes within the musculature in the intestine such as increased elastin, can lead to increased frequency of herniation. Laxity of the phreno-esophageal and gastro-hepatic ligaments can lead to hiatal hernia, which in turn can lead to commonly reported symptoms such as acid reflux, abdominal pain, early satiety, and bloating. Internal organ prolapses and intestinal intussusceptions occur with greater frequency in patients with weakened connective tissues.

Autonomic problems

Although neurogastroenterological manifestations in connective tissue disorders are common, their root cause is not yet known. Splanchnic circulation, small fiber neuropathy and altered vascular compliance have all been named as potential contributors to gastrointestinal complaints, particularly for patients who have a known, comorbid autonomic condition.

Neurological

Chronic headaches are common in patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, whether related to dysautonomia, TMJ, muscle tension, or craniocervical instability. Craniocervical instability is caused by trauma(s) to the head and neck areas such as concussion and whiplash. Ligaments in the neck are unable to heal properly, so the neck structure cannot support the skull, which can then sink into the brain stem, blocking the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, which in turn causes autonomic dysfunction.

Arnold–Chiari malformation is also more frequently found in patients with EDS because of the instability at the juncture between skull and spine. This causes herniation of the posterior fossa below the foramen magnum. Increased pressure created by the malformation can lead to a flattened pituitary gland, hormone changes, sudden severe headaches, ataxia, and poor proprioception.

Ophthalmological manifestations include nearsightedness, retinal tearing and retinal detachment, keratoconus, blue sclera, dry eye, Sjogren's syndrome, lens subluxation, angioid streaks, epicanthal folds, strabismus, corneal scarring, brittle cornea syndrome, cataracts, carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas, and macular degeneration.

Otological complications may also occur. Hearing loss is common, both conductive and sensorineural, and is most often bilateral. Otosclerosis and instability of the bones in the inner ear may also contribute to hearing loss.

Other manifestations

- Hiatal hernia

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Poor gastrointestinal motility

- Dysautonomia

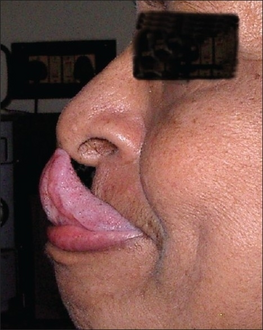

- Gorlin's sign (touch tongue to nose)

- Anal prolapse

- Flat feet

- Tracheobronchomalacia / tracheal collapse

- Collapsed lung (spontaneous pneumothorax)

- Nerve disorders (carpal tunnel syndrome, acroparesthesia, neuropathy, including small fiber neuropathy)

- Insensitivity to local anesthetics

- Dental problems including gum disease and enamel hypoplasia

- Platelet aggregation failure (platelets do not clump together properly)

- Mast cell disorders (including mast cell activation syndrome and mastocytosis)

- Pregnancy complications: increased pain, mild to moderate peripartum bleeding, cervical insufficiency, uterine tearing, or premature rupture of membranes

- Hearing loss may occur in some types

- There is some evidence that EDS may be associated with greater than expected frequencies of neurodevelopmental disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other learning, communication and motor issues, including autism spectrum conditions and Tourette syndrome.

-

Gorlin's sign in a case of EDS

Gorlin's sign in a case of EDS

-

Keratoglobus in a case of EDS with brittle cornea syndrome

Keratoglobus in a case of EDS with brittle cornea syndrome

Because it is often undiagnosed or misdiagnosed in childhood, some instances of EDS have been mischaracterized as child abuse. The pain may also be misdiagnosed as a behavior disorder or Munchausen by proxy.

The pain associated with EDS ranges from mild to debilitating.

Causes

Every type of EDS except the hypermobile type (which affects the vast majority of people with EDS) can be positively tied to specific genetic variation.

Variations in these genes can cause EDS:

- Collagen primary structure and collagen processing: ADAMTS2, COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1, COL5A1, COL5A2

- Collagen folding and collagen cross-linking: PLOD1, FKBP14

- Structure and function of myomatrix: TNXB, COL12A1

- Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis: B4GALT7, B3GALT6, CHST14, DSE

- Complement pathway: C1R, C1S

- Intracellular processes: SLC39A13, ZNF469, PRDM5

Variations in these genes usually alter the structure, production, or processing of collagen or proteins that interact with collagen. Collagen provides structure and strength to connective tissue. A defect in collagen can weaken connective tissue in the skin, bones, blood vessels, and organs, resulting in the features of the disorder. Inheritance patterns depend on the specific syndrome.

Most forms of EDS are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means only one of the two copies of the gene in question must be altered to cause a disorder. A few are inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means both copies of the gene must be altered for a person to be affected. It can also be an individual (de novo or "sporadic") variation. Sporadic variations occur without any inheritance.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis can be made by an evaluation of medical history and clinical observation. The Beighton criteria are widely used to assess the degree of joint hypermobility. DNA and biochemical studies can help identify affected people. Diagnostic tests include collagen gene-variant testing, collagen typing via skin biopsy, echocardiogram, and lysyl hydroxylase or oxidase activity, but these tests are not able to confirm all cases, especially in instances of an unmapped variation, so clinical evaluation remains important. If multiple members of a family are affected, prenatal diagnosis may be possible using a DNA information technique known as a linkage study. Knowledge about EDS among all kinds of practitioners is poor. Research is ongoing to identify genetic markers for all types.

Diagnosing hEDS

Because no single gene has been identified as the sole cause of the most common type of EDS, hypermobile type, obtaining a diagnosis is often difficult. The 2017 diagnostic criteria are as follows:

- Criterion 1: Generalized joint hypermobility, as measured by the Beighton score

- Criterion 2: Minimum two of the following must be met:

- Symptoms that suggest a difference in connective tissue structure

- Unusually soft or velvety skin

- Mild skin hyperextensibility

- Unexplained striae distensae or rubae at the back, groins, thighs, breasts, and/or abdomen in adolescents, men, or pre-pubertal women without a history of significant gain or loss of body fat or weight

- Bilateral piezogenic papules of the heel

- Recurrent or multiple abdominal hernia(s)

- Atrophic scarring involving at least two sites and without the formation of truly papyraceous and/or hemosideric scars as seen in classical EDS

- Pelvic floor, rectal, and/or uterine prolapse in children, men, or nulliparous women without a history of morbid obesity or other known predisposing medical condition

- Dental crowding and high or narrow palate

- Arachnodactyly

- Arm span-to-height ratio ≥1.05

- Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) mild or greater based on strict echocardiographic criteria

- Aortic root dilatation with Z-score >+2

- Positive family history

- Proof that these symptoms interfere with daily life

- Musculoskeletal pain in two or more limbs, recurring daily for at least 3 months

- Chronic, widespread pain for ≥3 months

- Recurrent joint dislocations or frank joint instability, in the absence of trauma

- Symptoms that suggest a difference in connective tissue structure

- Criterion 3: Exclusion of all other possible connective tissue disorders that may be the root cause of symptoms.

In such cases where all criteria are met, a patient can be diagnosed with hEDS according to The International Consortium on Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders

Differential diagnosis

Several disorders share some characteristics with EDS. For example, in cutis laxa, the skin is loose, hanging, and wrinkled. In EDS, the skin can be pulled away from the body, but is elastic and returns to normal when let go. In Marfan syndrome, the joints are very mobile, and similar cardiovascular complications occur. People with a "marfanoid" appearance are often tall and thin with long arms and legs and "spidery" fingers while EDS phenotypes vary considerably. Certain subtypes of EDS may involve short stature, large eyes, and the appearance of a small mouth and chin, due to a small palate. The palate can have a high arch, causing dental crowding. Blood vessels can sometimes be easily seen through translucent skin, especially on the chest. The genetic connective tissue disorder Loeys–Dietz syndrome also has symptoms that overlap with EDS.

In the past, Menkes disease, a copper metabolism disorder, was thought to be a form of EDS. People are commonly misdiagnosed with fibromyalgia, bleeding disorders, or other disorders that can mimic EDS symptoms. Because of these similar disorders and complications that can arise from an unmonitored case of EDS, a correct diagnosis is important. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is worth consideration in diagnosis.

Management

No cure for Ehlers–Danlos syndrome is known, and treatment is supportive. Close monitoring of the cardiovascular system, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and orthopedic instruments (e.g., wheelchairs, bracing, casting) may be helpful. This can help stabilize the joints and prevent injury. Orthopedic instruments are helpful for the prevention of further joint damage, especially for long distances. People should avoid activities that cause the joint to lock or overextend.

A physician may prescribe casting to stabilize joints. Physicians may refer a person to an orthotist for orthotic treatment (bracing). Physicians may also consult a physical and/or occupational therapist to help strengthen muscles and teach people how to properly use and preserve their joints.

Aquatic therapy promotes muscular development and coordination. With manual therapy, the joint is gently mobilized within the range of motion and/or manipulations. If conservative therapy is not helpful, surgical joint repair may be necessary. Medication to decrease pain or manage cardiac, digestive, or other related conditions may be prescribed. To decrease bruising and improve wound healing, some people have responded to vitamin C. Medical care workers often take special precautions because of the sheer number of complications that tend to arise in people with EDS. In vascular EDS, signs of chest or abdominal pain are considered trauma situations.

Cannabinoids and medical marijuana have shown some efficacy in reducing pain levels.

In general, medical intervention is limited to symptomatic therapy. Before pregnancy, people with EDS may be recommended to have genetic counseling and to familiarize themselves with the risks pregnancy poses. Children with EDS should be given information about the disorder so they can understand why they should avoid contact sports and other physically stressful activities. Children should be taught that they should not demonstrate the unusual positions they can maintain due to loose joints, as this may cause early degeneration of the joints. Emotional support along with behavioral and psychological therapy can be useful. Support groups can be immensely helpful for people dealing with major lifestyle changes and poor health. Family members, teachers, and friends should be informed about EDS so they can accept and assist the child.

Pain management

Successful treatment of chronic pain in EDS requires a multidisciplinary team. The ways to manage pain can be to modify pain management techniques used in the normal population. Pain is classified into several types. One is nociceptive, which is caused by an injury sustained to tissues. Another is neuropathic pain, caused by abnormal signals by the nervous system. In many cases, the pain individuals experience is an unequal mix of the two. Physiotherapy (exercise rehabilitation) can be helpful, especially in stabilizing the core and the joints. Stretching exercises must be reduced to slow and gentle stretching to reduce the risks of dislocations or subluxations. Usable methods may include posture reeducation, muscle release, joint mobilization, trunk stabilization, and manual therapy for overworked muscles. Cognitive behavioural therapy is used in many chronic pain patients, especially those who have severe, chronic, life-controlling pain that is unresponsive to treatment. It has not been checked for efficiency in clinical trials. The state of pain management with EDS is considered insufficient.

Medications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may help if the pain is caused by inflammation. However, long-term use of NSAIDs is often a risk factor for gastrointestinal, renal, and blood-related side effects. It can worsen symptoms of mast cell activation syndrome, a disease that may be associated with EDS. Acetaminophen can be used to avoid the bleeding-related side effects of NSAIDs.

Lidocaine can be applied topically after subluxations and painful gums. It can also be injected into painful areas in the case of musculoskeletal pain.

If the pain is neuropathic in origin, tricyclic antidepressants in low doses, anticonvulsants, and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors can be used.

Dislocation and subluxation management

When a dislocation or subluxation does occur, muscle spasms and stress tend to occur, increasing pain and reducing the chances of the dislocation/subluxation naturally relieving. Methods to support a joint after such an incident include the usage of a sling to hold the joint in place and allow it to relax. Orthopedic casts are not advised as there could be pain if unrelaxed muscles are still trying to spasm out against the cast. Other solutions to promote relaxation are heat, gentle massaging, and mental distractions.

Surgery

The instability of joints, leading to subluxations and joint pain, often requires surgical intervention in people with EDS. Instability of almost all joints can happen, but appears most often in the lower and upper extremities, with the wrist, fingers, shoulder, knee, hip, and ankle being most common.

Common surgical procedures are joint debridement, tendon replacements, capsulorrhaphy, and arthroplasty. Aortic dissection and other such complications of vascular EDS will mandate surgical intervention. After surgery, the degree of stabilization, pain reduction, and people's satisfaction can improve, but surgery does not guarantee an optimal result; affected people and surgeons report being dissatisfied with the results. The consensus is that conservative treatment is more effective than surgery, particularly since people have extra risks of surgical complications due to the disease. Three basic surgical problems arise due to EDS – the strength of the tissues is decreased, which makes the tissue less suitable for surgery; the fragility of the blood vessels can cause problems during surgery; and wound healing is often delayed or incomplete. If considering surgical intervention, seeking care from a surgeon with extensive knowledge and experience in treating people with EDS and joint hypermobility issues would be prudent.

Local anesthetics, arterial catheters, and central venous catheters cause a higher risk of bruise formation in people with EDS. Some people with EDS also show a resistance to local anaesthetics. Resistance to lidocaine and bupivacaine is not uncommon, and mepivacaine tends to work better in people with EDS. Special recommendations for anesthesia are given for people with EDS. Detailed recommendations for anesthesia and perioperative care of people with EDS should be used to improve safety.

Surgery in people with EDS requires careful tissue handling and a longer immobilization afterward.

Prognosis

The outcome for individuals with EDS depends on the specific type of EDS they have. Symptoms vary in severity, even in the same disorder, and the frequency of complications varies. Some people have negligible symptoms, while others are severely restricted in daily life. Extreme joint instability, chronic musculoskeletal pain, degenerative joint disease, frequent injuries, and spinal deformities may limit mobility. Severe spinal deformities may affect breathing. In the case of extreme joint instability, dislocations may result from simple tasks such as rolling over in bed or turning a doorknob. Secondary conditions such as autonomic dysfunction or cardiovascular problems, occurring in any type, can affect prognosis and quality of life. Severe mobility-related disability is seen more often in hEDS than in classical EDS or vascular EDS.

Although all types of EDS are potentially life-threatening, most people have a normal lifespan. Those with blood vessel fragility, though, have a high risk of fatal complications, including spontaneous arterial rupture, which is the most common cause of sudden death. The median life expectancy in the population with vascular EDS is 48 years.

Complications

Vascular

- Pseudoaneurysm

- Vascular lesions (nature is disputed) due to tears in the lining of the arteries or deterioration of congenitally thin and fragile tissue

- Enlarged arteries

Gastrointestinal

- A 50% risk of colonic perforation exists in vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

Obstetric

- Pregnancy increases the likelihood of uterine rupture.

- Maternal mortality is around 12% for the vascular type.

- Uterine hemorrhage can occur during the postpartum recovery.

Epidemiology

Ehlers–Danlos syndromes are estimated to occur in about one in 5,000 births worldwide. Initially, prevalence estimates ranged from one in 250,000 to 500,000 people, but these were soon found to be low, as medical professionals became more adept at diagnosis. EDS may be far more common than the currently accepted estimate due to the wide range of severities with which the disorder presents.

The prevalence of the disorders differs dramatically. The most common is hypermobile EDS, followed by classical EDS. The others are very rare. For example, fewer than 10 infants and children with dermatosparaxis EDS have been described worldwide.

Some types of EDS are more common in Ashkenazi Jews. For example, the chance of being a carrier for dermatosparaxis EDS is one in 2,000 in the general population but one in 248 among Ashkenazi Jews.

Some recent studies have found that EDS is significantly more prevalent in people who identify as transgender or gender-diverse, or who suffer from gender dysphoria. One review, of a pediatric EDS clinic in the American Midwest between 2020 and 2022, found that 17% of patients identified as trans or gender-diverse, 89% of whom were assigned female at birth. By comparison, roughly 1-2% of adolescents identify as trans or gender-diverse in the US overall. Meanwhile, a 2020 analysis found that among adults undergoing gender-affirming surgery, 2.6% had a diagnosis of EDS—130 times the highest reported prevalence of EDS in the general population.

History

Until 1997, the classification system for EDS included ten specific types and acknowledged that other rarer types existed. At this time, the classification system underwent an overhaul and was reduced to six major types using descriptive titles. Genetic specialists recognize that other types of this condition exist but have only been documented in single families. Except for hypermobility (type 3), the most common type of all ten types, some of the specific variations involved have been identified, and they can be precisely identified by genetic testing; this is valuable due to a great deal of variation in individual cases. Negative genetic test results do not rule out the diagnosis since not all variations have been discovered; therefore, the clinical presentation is crucial.

Forms of EDS in this category may present with soft, mildly stretchable skin, shortened bones, chronic diarrhea, joint hypermobility and dislocation, bladder rupture, or poor wound healing. Inheritance patterns in this group include X-linked recessive, autosomal dominant, and autosomal recessive. Examples of types of related syndromes other than those above reported in the medical literature include:

- 305200: type 5

- 130080: type 8 – unspecified gene, locus 12p13

- 225310: type 10 – unspecified gene, locus 2q34

- 608763: Beasley–Cohen type

- 130070: progeroid form – B4GALT7

- 130090: type unspecified

- 601776: D4ST1-deficient Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (adducted thumb-clubfoot syndrome) CHST14

Society and culture

EDS may have contributed to the virtuoso violinist Niccolò Paganini's skill, as he was able to play wider fingerings than a typical violinist.

Many sideshow performers have EDS. Several of them were billed as the Elastic Skin Man, the India Rubber Man, and Frog Boy. They included such well-known individuals (in their time) as Felix Wehrle, James Morris, and Avery Childs. Two performers with EDS currently hold world records. Contortionist Daniel Browning Smith has hypermobile EDS and holds the current Guinness World Record for the most flexible man as of 2018, while Gary "Stretch" Turner, sideshow performer in the Circus Of Horrors, has held the current Guinness World Record for the most elastic skin since 1999, for his ability to stretch the skin on his stomach 6.25 inches.

Notable cases

- Actress Cherylee Houston has hypermobile EDS. She uses a wheelchair and was the first full-time disabled actress on Coronation Street

- Drag queen and winner of the 11th season of RuPaul's Drag Race Yvie Oddly

- Eric the Actor, a regular caller to The Howard Stern Show

- Actress and activist Jameela Jamil

- Writer and actress Lena Dunham

- Australian singer Sia

- Singer Halsey

- YouTuber and disability rights activist Annie Elainey

- Miss America 2020 Camille Schrier

- Baroque flutist, musicologist and broadcast classical music presenter Hannah French

- Deaf singer/songwriter Mandy Harvey

- YouTuber and disability rights activist Jessica Kellgren-Fozard.

- Singer-songwriter, author and artist Martha Marlow

- Pornographic actor and writer Lorelei Lee

- Reality show contestant Trevor Jones, dead from the vascular form of the disorder

- Scrunchie creator Rommy Hunt Revson, dead from a ruptured aorta

- Japanese voice actress and singer Tomori Kusunoki

Representation in media

Literature

The fantasy novel Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros presents a main character, Violet Sorrengail, who has an unnamed chronic condition that aligns closely with EDS symptoms. When asked about this connection Rebecca Yarros agrees with the connection but says EDS goes unnamed due to the level of medical knowledge present in her story's world. Yarros has EDS and included it as a representation of her condition.

Television

Grey's Anatomy, a long-running TV series, approached the topic of EDS in their 13th season. In the episode "Falling Slowly", the show's doctors are confronted with confusion when met with diagnosing a patient. Due to complex and contradicting symptoms presented by the patient, the show's doctors ultimately give the diagnosis of EDS. This episode was based on conversations held by producers who talked with a patient and doctor who have EDS.

Other species

Ehlers–Danlos–like syndromes are hereditary in Himalayan cats, some domestic shorthair cats, and certain breeds of cattle. It is seen as a sporadic condition in domestic dogs, with higher frequency in English Springers. It has a similar treatment and prognosis. Animals with the condition should not be bred, as the condition can be inherited.

Degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis is a similar condition seen in many breeds of horses. It was originally notated in the Peruvian Paso and thought to be a condition of overwork and older age, but it is being recognized in all age groups and all activity levels. It has been noted in newborn foals.

See also

References

- ^ "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

The 2017 classification describes 13 types of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

- "Amplified Musculoskeletal Pain Syndrome (AMPS)". Children's Health.

- ^ Anderson BE (2012). The Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations – Integumentary System (2nd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 235. ISBN 978-1455726646. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05 – via E-Book.

- ^ Lawrence EJ (December 2005). "The clinical presentation of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Advances in Neonatal Care. 5 (6): 301–314. doi:10.1016/j.adnc.2005.09.006. PMID 16338669. S2CID 7717730.

- ^ "Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. 20 April 2017. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Ferri FF (2016). Ferri's Netter Patient Advisor. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 939. ISBN 9780323393249. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- Dattagupta A, Williamson S, El Nihum LI, Petak S (2022-11-01). "A Case of Spondylodysplastic Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome With Comorbid Hypophosphatasia". AACE Clinical Case Reports. 8 (6): 255–258. doi:10.1016/j.aace.2022.08.005. PMC 9701907. PMID 36447830.

- ^ Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, Belmont J, Berglund B, Black J, et al. (March 2017). "The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 8–26. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31552. PMID 28306229. S2CID 4440499.

- ^ "Genetics and Inheritance of EDS and HSD". The Ehlers–Danlos Society. 2023.

- "Ehlers-Danlos syndrome - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org.

- ^ Brady AF, Demirdas S, Fournel-Gigleux S, Ghali N, Giunta C, Kapferer-Seebacher I, et al. (March 2017). "The Ehlers–Danlos syndromes, rare types". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 70–115. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31550. PMID 28306225. S2CID 4439633.

- ^ Doolan BJ, Lavallee ME, Hausser I, Schubart JR, Michael Pope F, Seneviratne SL, et al. (23 Jan 2023). "Extracutaneous features and complications of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes: A systematic review". Frontiers in Medicine. 10: 1053466. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1053466. PMC 9899794. PMID 36756177.

- ^ Marathe N, Lohkamp LN, Fehlings MG (December 2022). "Spinal manifestations of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: a scoping review". Journal of Neurosurgery. Spine. 37 (6): 783–793. doi:10.3171/2022.6.SPINE211011. PMID 35986728. S2CID 251694109.

- Tinkle B, Castori M, Berglund B, Cohen H, Grahame R, Kazkaz H, Levy H (March 2017). "Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (a.k.a. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome Type III and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome hypermobility type): Clinical description and natural history". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 48–69. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31538. PMID 28145611. S2CID 4440630.

- Beighton PH, Grahame R, Bird HA (2011). Hypermobility of Joints. Springer. p. 1. ISBN 9781848820852. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- ^ Byers PH, Murray ML (November 2012). "Heritable collagen disorders: the paradigm of the Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 132 (E1): E6-11. doi:10.1038/skinbio.2012.3. PMID 23154631.

- ^ "The Types of EDS". The Ehlers Danlos Society. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ Levy HP (1993). Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Stephens K, Amemiya A (eds.). "Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome". GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301456.

- Carter K. "Hypermobile EDS and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders". Ehlers–Danlos Support UK.

- "Pregnancy, birth, feeding, and hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome/hypermobility spectrum disorders". The Ehlers–Danlos Support UK. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- Cantu L (14 July 2021). "MUSC researchers announce gene mutation discovery associated with EDS". Medical University of South Carolina. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "HEDGE Study". ehlers-danlos.com.

- "About the Lab". Norris Lab, Medical University of South Carolina.

- Gensemer C, Burks R, Kautz S, Judge DP, Lavallee M, Norris RA (March 2021). "Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndromes: Complex phenotypes, challenging diagnoses, and poorly understood causes". Developmental Dynamics. 250 (3): 318–344. doi:10.1002/dvdy.220. PMC 7785693. PMID 32629534.

- Narcisi P, Richards AJ, Ferguson SD, Pope FM (September 1994). "A family with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type III/articular hypermobility syndrome has a glycine 637 to serine substitution in type III collagen". Human Molecular Genetics. 3 (9): 1617–1620. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.9.1617. PMID 7833919.

- Lyons JJ, Yu X, Hughes JD, Le QT, Jamil A, Bai Y, et al. (December 2016). "Elevated basal serum tryptase identifies a multisystem disorder associated with increased TPSAB1 copy number". Nature Genetics. 48 (12): 1564–1569. doi:10.1038/ng.3696. PMC 5397297. PMID 27749843.

- Moore K, Fulmer D, Guo L, Koren N, Glover J, Moore R, et al. (March 2021). "PDGFRα: Expression and Function during Mitral Valve Morphogenesis". Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 8 (3): 28. doi:10.3390/jcdd8030028. PMC 7999759. PMID 33805717.

- ^ Malfait F, Wenstrup R, De Paepe A (July 2018). "Classic Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome". In Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Stephens K, Amemiya A (eds.). GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301422. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- Kapferer-Seebacher I, Lundberg P, Malfait F, Zschocke J (November 2017). "Periodontal manifestations of Ehlers–Danlos syndromes: A systematic review". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 44 (11): 1088–1100. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12807. PMID 28836281. S2CID 36252998.

- Castori M (2012). "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type: an underdiagnosed hereditary connective tissue disorder with mucocutaneous, articular, and systemic manifestations". ISRN Dermatology. 2012: 751768. doi:10.5402/2012/751768. PMC 3512326. PMID 23227356.

- Rakhmanov Y, Maltese PE, Bruson A, Castori M, Beccari T, Dundar M, Bertelli M (2018-09-01). "Genetic testing for vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and other variants with fragility of the middle arteries". The EuroBiotech Journal. 2 (s1): 42–44. doi:10.2478/ebtj-2018-0034. ISSN 2564-615X. S2CID 86589984.

- ^ Eagleton MJ (December 2016). "Arterial complications of vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 64 (6): 1869–1880. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.06.120. PMID 27687326.

- "Kyphoscoliotic Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- Klaassens M, Reinstein E, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Schrander JJ, Malfait F, Staal H, et al. (August 2012). "Ehlers–Danlos arthrochalasia type (VIIA-B) – expanding the phenotype: from prenatal life through adulthood". Clinical Genetics. 82 (2): 121–130. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01758.x. PMC 4026000. PMID 21801164.

- "Dermatosparaxis Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- ^ "Brittle cornea syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- "OMIM Entry – # 614170 – Brittle Cornea Syndrome 2; BCS2". www.omim.org. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- "Spondylodysplastic Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2020-07-08. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

- "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, musculocontractural type - Conditions – GTR – NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

- Nitahara-Kasahara Y, Mizumoto S, Inoue YU, Saka S, Posadas-Herrera G, Nakamura-Takahashi A, et al. (December 2021). "A new mouse model of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome generated using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genomic editing". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 14 (12): dmm048963. doi:10.1242/dmm.048963. PMC 8713987. PMID 34850861.

- Guarnieri V, Morlino S, Di Stolfo G, Mastroianno S, Mazza T, Castori M (May 2019). "Cardiac valvular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome is a well-defined condition due to recessive null variants in COL1A2". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 179 (5): 846–851. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.61100. PMID 30821104. S2CID 73470267.

- "What are the Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes?". The Ehlers Danlos Society. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Genetic Home Reference. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "Ehlers Danlos Syndromes". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ^ "Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Wei DH, Terrono AL (October 2015). "Superficialis Sling (Flexor Digitorum Superficialis Tenodesis) for Swan Neck Reconstruction". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 40 (10): 2068–2074. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.07.018. PMID 26328902.

- ^ "Vascular Type-EDS". Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome Network C.A.R.E.S. Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-06-04. Retrieved 2012-05-25.

- Dordoni C, Ciaccio C, Venturini M, Calzavara-Pinton P, Ritelli M, Colombi M (August 2016). "Further delineation of FKBP14-related Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: A patient with early vascular complications and non-progressive kyphoscoliosis, and literature review". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 170 (8): 2031–2038. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.37728. hdl:11379/494257. PMID 27149304. S2CID 43512125.

- ^ Henderson FC, Austin C, Benzel E, Bolognese P, Ellenbogen R, Francomano CA, et al. (March 2017). "Neurological and spinal manifestations of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 195–211. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31549. PMID 28220607. S2CID 4438281.

- Carbone L, Tylavsky FA, Bush AJ, Koo W, Orwoll E, Cheng S (2000). "Bone density in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Osteoporosis International. 11 (5): 388–392. doi:10.1007/s001980070104. PMID 10912839. S2CID 441230.

- Nijs J, Van Essche E, De Munck M, Dequeker J (July 2000). "Ultrasonographic, axial, and peripheral measurements in female patients with benign hypermobility syndrome". Calcified Tissue International. 67 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1007/s00223001093. PMID 10908410. S2CID 21083444.

- Gedalia A, Press J, Klein M, Buskila D (July 1993). "Joint hypermobility and fibromyalgia in schoolchildren". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 52 (7): 494–496. doi:10.1136/ard.52.7.494. PMC 1005086. PMID 8346976.

- Dommerholt J (2012-01-27). "CSF Ehlers Danlos Colloquium, Dr Jan Dommerholt". Chiari & Syringomyelia Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Vigorita VJ, Mintz D, Ghelman B (2008). Orthopaedic pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0781796705.

- "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome - Diagnosis – Approach". BMJ Best Practice. 13 December 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- "Ehlers Danlos Syndrome – Morphopedics". morphopedics.wikidot.com. Retrieved 2018-06-15.

- ^ "Classical Type-EDS". Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome Network C.A.R.E.S Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-05-30. Retrieved 2012-05-25.

- Portable Signs and Symptoms. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. p. 465. ISBN 9781582556796. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- "Piezogenic papules – DermNet New Zealand". www.dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 2016-11-26.

- Ericson WB, Wolman R (March 2017). "Orthopaedic management of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 188–194. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31551. eISSN 1552-4876. PMID 28192621. S2CID 4377720.

- ^ Camerota F, Castori M, Celletti C, Colotto M, Amato S, Colella A, et al. (July 2014). "Heart rate, conduction and ultrasound abnormalities in adults with joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type". Clinical Rheumatology. 33 (7): 981–987. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2618-y. PMID 24752348. S2CID 32745869.

- Wenstrup RJ, Hoechstetter LB (2001). "The Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes". In Allanson JE, Cassidy SB (eds.). Management of genetic syndromes. New York: Wiley-Liss. pp. 131–149. ISBN 978-0-471-31286-4.

- Grigoriou E, Boris JR, Dormans JP (February 2015). "Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): association with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and orthopaedic considerations". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 473 (2): 722–728. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3898-x. eISSN 1528-1132. PMC 4294907. PMID 25156902.

- Hakim A, O'Callaghan C, De Wandele I, Stiles L, Pocinki A, Rowe P (March 2017). "Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome-Hypermobile type". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 168–174. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31543. PMID 28160388. S2CID 4439857.

- Ormiston CK, Padilla E, Van DT, Boone C, You S, Roberts AC, Hsiao A, Taub PR (2022-04-09). "May-Thurner syndrome in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a case series". European Heart Journal: Case Reports. 6 (4): ytac161. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytac161. ISSN 2514-2119. PMC 9131024. PMID 35620060.

- Raffetto JD, Khalil RA (April 2008). "Mechanisms of varicose vein formation: valve dysfunction and wall dilation" (PDF). Phlebology. 23 (2): 85–98. doi:10.1258/phleb.2007.007027. PMID 18453484. S2CID 33320026.

- Blagowidow N (December 2021). "Obstetrics and gynecology in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: A brief review and update". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 187 (4): 593–598. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31945. PMID 34773390. S2CID 244076387.

- McIntosh LJ, Stanitski DF, Mallett VT, Frahm JD, Richardson DA, Evans MI (1996). "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: relationship between joint hypermobility, urinary incontinence, and pelvic floor prolapse". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 41 (2): 135–139. doi:10.1159/000292060. PMID 8838976.

- Kciuk O, Li Q, Huszti E, McDermott CD (February 2023). "Pelvic floor symptoms in natal women with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: an international survey study". International Urogynecology Journal. 34 (2): 473–483. doi:10.1007/s00192-022-05273-8. PMID 35751670. S2CID 250022004.

- ^ Hugon-Rodin J, Lebègue G, Becourt S, Hamonet C, Gompel A (September 2016). "Gynecologic symptoms and the influence on reproductive life in 386 women with hypermobility type ehlers-danlos syndrome: a cohort study". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 11 (1): 124. doi:10.1186/s13023-016-0511-2. PMC 5020453. PMID 27619482.

- ^ Kumskova M, Flora GD, Staber J, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK (July 2023). "Characterization of bleeding symptoms in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 21 (7): 1824–1830. doi:10.1016/j.jtha.2023.04.004. PMID 37179130. S2CID 258203231.

- Pearce G, Bell L, Pezaro S, Reinhold E (October 2023). "Childbearing with Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders: A Large International Survey of Outcomes and Complications". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 20 (20): 6957. doi:10.3390/ijerph20206957. PMC 10606623. PMID 37887695.

- ^ Fikree A, Chelimsky G, Collins H, Kovacic K, Aziz Q (March 2017). "Gastrointestinal involvement in the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 181–187. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31546. PMID 28186368.

- Adib N, Davies K, Grahame R, Woo P, Murray KJ (June 2005). "Joint hypermobility syndrome in childhood. A not so benign multisystem disorder?". Rheumatology. 44 (6): 744–750. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh557. PMID 15728418.

- Danese C, Castori M, Celletti C, Amato S, Lo Russo C, Grammatico P, Camerota F (September 2011). "Screening for celiac disease in the joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers–Danlos syndrome hypermobility type". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 155A (9): 2314–2316. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.34134. PMID 21815256. S2CID 205314742.

- Laszkowska M, Roy A, Lebwohl B, Green PH, Sundelin HE, Ludvigsson JF (September 2016). "Nationwide population-based cohort study of celiac disease and risk of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and joint hypermobility syndrome". Digestive and Liver Disease. 48 (9): 1030–1034. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2016.05.019. PMID 27321543.

- Abonia JP, Wen T, Stucke EM, Grotjan T, Griffith MS, Kemme KA, et al. (August 2013). "High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 132 (2): 378–386. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.030. PMC 3807809. PMID 23608731.

- Zarate N, Farmer AD, Grahame R, Mohammed SD, Knowles CH, Scott SM, Aziz Q (March 2010). "Unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms and joint hypermobility: is connective tissue the missing link?". Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 22 (3): 252–e78. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01421.x. PMID 19840271. S2CID 11516253.

- Menys A, Keszthelyi D, Fitzke H, Fikree A, Atkinson D, Aziz Q, Taylor SA (September 2017). "A magnetic resonance imaging study of gastric motor function in patients with dyspepsia associated with Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome-Hypermobility Type: A feasibility study". Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 29 (9). doi:10.1111/nmo.13090. PMID 28568908. S2CID 776971.

- Zeitoun JD, Lefèvre JH, de Parades V, Séjourné C, Sobhani I, Coffin B, Hamonet C (2013-11-22). Karhausen J (ed.). "Functional digestive symptoms and quality of life in patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndromes: results of a national cohort study on 134 patients". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e80321. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880321Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080321. PMC 3838387. PMID 24278273.

- Çınar M, Çakar M, Öztürk K, Çetindağlı İ, Yılmaz S, Dinç A (March 2017). "Investigation of joint hypermobility in individuals with hyperbilirubinemia". European Journal of Rheumatology. 4 (1): 36–39. doi:10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.16051. PMC 5335885. PMID 28293451.

- Nelson AD, Mouchli MA, Valentin N, Deyle D, Pichurin P, Acosta A, Camilleri M (November 2015). "Ehlers Danlos syndrome and gastrointestinal manifestations: a 20-year experience at Mayo Clinic". Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 27 (11): 1657–1666. doi:10.1111/nmo.12665. PMID 26376608. S2CID 41431319.

- ^ Thwaites PA, Gibson PR, Burgell RE (September 2022). "Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and disorders of the gastrointestinal tract: What the gastroenterologist needs to know". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 37 (9): 1693–1709. doi:10.1111/jgh.15927. PMC 9544979. PMID 35750466.

- Castori M, Morlino S, Pascolini G, Blundo C, Grammatico P (March 2015). "Gastrointestinal and nutritional issues in joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 169C (1): 54–75. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31431. PMID 25821092. S2CID 11773627.

- Mehr SE, Barbul A, Shibao CA (August 2018). "Gastrointestinal symptoms in postural tachycardia syndrome: a systematic review". Clinical Autonomic Research. 28 (4): 411–421. doi:10.1007/s10286-018-0519-x. PMC 6314490. PMID 29549458.

- Gazit Y, Nahir A, Grahame R, Jacob G (July 2003). "Dysautonomia in the joint hypermobility syndrome". The American Journal of Medicine. 115 (1): 33–40. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00235-3. PMID 12867232.

- Henderson F (2015). "Indices of Cranio-vertebral Instability". Funded Research. Chiari & Syringomyelia Foundation. Archived from the original on 2016-09-16.

- Castori M, Voermans NC (October 2014). "Neurological manifestations of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome(s): A review". Iranian Journal of Neurology. 13 (4): 190–208. PMC 4300794. PMID 25632331.

- Dyste GN, Menezes AH, VanGilder JC (1989-08-01). "Symptomatic Chiari malformations: An analysis of presentation, management, and long-term outcome". Journal of Neurosurgery. 71 (2): 159–168. doi:10.3171/jns.1989.71.2.0159. PMID 2746341.

- Langridge B, Phillips E, Choi D (August 2017). "Chiari Malformation Type 1: A Systematic Review of Natural History and Conservative Management". World Neurosurgery. 104: 213–219. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.082. ISSN 1878-8750. PMID 28435116.

- William A (18 January 2015). "Ehlers–Danilo's Syndrome – The Role of Collagen in the Eye – Information". The Canadian Ehlers Danlos Association. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- Weir FW, Hatch JL, Muus JS, Wallace SA, Meyer TA (July 2016). "Audiologic Outcomes in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome". Otology & Neurotology. 37 (6): 748–752. doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000001082. ISSN 1531-7129. PMID 27253074. S2CID 5286116.

- Miyajima C, Ishimoto SI, Yamasoba T (January 2007). "Otosclerosis associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: report of a case". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 127 (sup559): 157–159. doi:10.1080/03655230701600418. ISSN 0001-6489. PMID 18340588. S2CID 2517459.

- Zeitoun JD, Lefèvre JH, de Parades V, Séjourné C, Sobhani I, Coffin B, Hamonet C (November 2013). "Functional digestive symptoms and quality of life in patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndromes: results of a national cohort study on 134 patients". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e80321. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880321Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080321. eISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3838387. PMID 24278273.

- Brockway L (April 2016). "Gastrointestinal manifestations of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hypermobility type)". Ehlers–Danlos Support UK. Archived from the original on 2016-11-14.

- "Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome". Underlying Causes of Dysautonomia. Dysautonomia International. 2012. Archived from the original on 2014-12-18.

- Létourneau Y, Pérusse R, Buithieu H (June 2001). "Oral manifestations of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Journal. 67 (6): 330–334. PMID 11450296. Archived from the original on 2016-12-15.

- "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: Definition from". Answers.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- Arendt-Nielsen L. "Patients Suffering from Ehlers Danlos Syndrome Type III Do Not Respond to Local Anesthetics". Archived from the original on 2015-04-05.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Seneviratne SL, Maitland A, Afrin L (March 2017). "Mast cell disorders in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 226–236. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31555. PMID 28261938. S2CID 4438476.

- Lind J, Wallenburg HC (April 2002). "Pregnancy and the Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: a retrospective study in a Dutch population". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 81 (4): 293–300. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810403.x. hdl:1765/72381. PMID 11952457. S2CID 39943713.

- "Ehlers Danlos Syndromes". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- Baeza-Velasco C (2021). "Neurodevelopmental atypisms in the context of joint hypermobility, hypermobility spectrum disorders, and Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 187 (4): 491–499. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31946. PMID 34741402. S2CID 243801668.

- Santschi DR (April 3, 2008). "Redlands mother stung by untrue suspicions presses for accountability in child abuse inquiries". The Press Enterprise. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009.

- ^ Chopra P, Tinkle B, Hamonet C, Brock I, Gompel A, Bulbena A, Francomano C (March 2017). "Pain management in the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 212–219. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31554. PMID 28186390. S2CID 4433630.

- Chopra P, Tinkle B, Hamonet C, Brock I, Gompel A, Bulbena A, Francomano C (March 2017). "Pain management in the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 175 (1): 212–219. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31554. PMID 28186390. S2CID 4433630.

- "EDS Types". The Ehlers Danlos Society. Archived from the original on 2017-06-24. Retrieved 2017-05-22.

- Sobey G (January 2015). "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: how to diagnose and when to perform genetic tests". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 100 (1): 57–61. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-304822. PMID 24994860. S2CID 11660992.

- Ross J, Grahame R (January 2011). "Joint hypermobility syndrome". BMJ. 342: c7167. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7167. PMID 21252103. S2CID 1284069.

- Castori M (2012). "Ehlers–danlos syndrome, hypermobility type: an underdiagnosed hereditary connective tissue disorder with mucocutaneous, articular, and systemic manifestations". ISRN Dermatology. 2012: 751768. doi:10.5402/2012/751768. PMC 3512326. PMID 23227356.

- "The Types of EDS". The Ehlers Danlos Society. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- Forghani I (January 1, 2019). "Updates in Clinical and Genetics Aspects of Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome". Balkan Medical Journal. 36 (1): 12–16. doi:10.4274/balkanmedj.2018.1113. PMC 6335943. PMID 30063214.

- "The International Consortium on Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders - The Ehlers Danlos Society". www.ehlers-danlos.com. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- "Differential Diagnosis". www.loeysdietz.org. Archived from the original on 2017-06-23.

- "Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome". Rarediseases.about.com. 2006-05-25. Archived from the original on 2014-04-12. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- "Pseudoxanthoma elasticum". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- "Physiotherapy and self-management – The Ehlers–Danlos Support UK". www.ehlers-danlos.org. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ^ Rombaut L, Malfait F, De Wandele I, Cools A, Thijs Y, De Paepe A, Calders P (July 2011). "Medication, surgery, and physiotherapy among patients with the hypermobility type of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 92 (7): 1106–1112. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.01.016. PMID 21636074.

- ^ Woerdeman LA, Ritt MJ, Meijer B, Maas M (2000). "Wrist problems in patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". European Journal of Plastic Surgery. 23 (4): 208–210. doi:10.1007/s002380050252. S2CID 29979747.

- Callewaert B, Malfait F, Loeys B, De Paepe A (March 2008). "Ehlers–Danlos syndromes and Marfan syndrome". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 22 (1): 165–189. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2007.12.005. PMID 18328988.

- Genetics of Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome~treatment at eMedicine

- "Vascular (VEDS) Emergency Information". The Ehlers Danlos Society. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- "Topics in Pain Management: pain management in patients with hypermobility disorders: frequently missed causes of chronic pain" (PDF). Topics in Pain Management.

- Giroux CM, Corkett JK, Carter LM (2016). "The Academic and Psychosocial Impacts of Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome on Postsecondary Students: An Integrative Review of the Literature" (PDF). Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability. 29 (4): 414.

- "Dislocation/Subluxation Management". The Ehlers Danlos Society. Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ^ Wiesmann T, Castori M, Malfait F, Wulf H (July 2014). "Recommendations for anesthesia and perioperative management in patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome(s)". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 9: 109. doi:10.1186/s13023-014-0109-5. PMC 4223622. PMID 25053156.

- Parapia LA, Jackson C (April 2008). "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome – a historical review". British Journal of Haematology. 141 (1): 32–35. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.06994.x. PMID 18324963. S2CID 7809153.

- Shirley ED, Demaio M, Bodurtha J (September 2012). "Ehlers–danlos syndrome in orthopaedics: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment implications". Sports Health. 4 (5): 394–403. doi:10.1177/1941738112452385. PMC 3435946. PMID 23016112.

- "What are the Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes?". The Ehlers Danlos Society. Retrieved 2019-09-10.

- Pepin M, Schwarze U, Superti-Furga A, Byers PH (March 2000). "Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type". The New England Journal of Medicine. 342 (10): 673–680. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.603.1293. doi:10.1056/NEJM200003093421001. PMID 10706896.

- ^ Pepin M, Schwarze U, Superti-Furga A, Byers PH (March 2000). "Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type". The New England Journal of Medicine. 342 (10): 673–680. doi:10.1056/NEJM200003093421001. PMID 10706896.

- "Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome: Epidemiology". Medscape.com. Archived from the original on 2013-04-24. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type VIIc". geneaware.clinical.bcm.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-08-14. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- "Gender dysphoria in adolescents with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome - PMC".

- thisisloyalcom L. "How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States?". Williams Institute.

- https://f.oaes.cc/xmlpdf/e9629768-ba1a-4b51-8e32-b7f9c328de95/4858.pdf

- "What is EDS". The Ehlers–Danlos National Foundation. Archived from the original on 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- "Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- Yücel D (January 1995). "Was Paganini born with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome phenotype 4 or 3?". Clinical Chemistry. 41 (1): 124–125. doi:10.1093/clinchem/41.1.124. PMID 7813066.

- "Stretchiest skin". Guinness World Records. 29 October 1999. Retrieved 2019-06-22.

- Rollo S (2010-05-22). "Houston hits out at 'preconceived ideas' – Coronation Street News – Soaps". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- Oddly Y (April 11, 2019). "Drag Race's Yvie Oddly Opens Up About Living with Ehlers Danos Disease". www.out.com.

- Rosenberg P (30 September 2014). "Eric the Actor: A Eulogy". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Gillespie C (21 February 2019). "Jameela Jamil Confirms She Has Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome". SELF. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Ellis R (November 3, 2019). "Lena Dunham goes on Instagram to reveal she has Ehlers–Danlos syndrome". CNN.