| Lie groups and Lie algebras | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

Classical groups

|

||||

Simple Lie groups

|

||||

| Other Lie groups | ||||

| Lie algebras | ||||

| Semisimple Lie algebra | ||||

| Representation theory | ||||

| Lie groups in physics | ||||

| Scientists | ||||

| Algebraic structure → Ring theory Ring theory |

|---|

Basic conceptsRings

Related structures

|

| Commutative algebraCommutative rings |

|

Noncommutative algebraNoncommutative rings

Noncommutative algebraic geometry Operator algebra |

In mathematics, a Lie algebra (pronounced /liː/ LEE) is a vector space together with an operation called the Lie bracket, an alternating bilinear map , that satisfies the Jacobi identity. In other words, a Lie algebra is an algebra over a field for which the multiplication operation (called the Lie bracket) is alternating and satisfies the Jacobi identity. The Lie bracket of two vectors and is denoted . A Lie algebra is typically a non-associative algebra. However, every associative algebra gives rise to a Lie algebra, consisting of the same vector space with the commutator Lie bracket, .

Lie algebras are closely related to Lie groups, which are groups that are also smooth manifolds: every Lie group gives rise to a Lie algebra, which is the tangent space at the identity. (In this case, the Lie bracket measures the failure of commutativity for the Lie group.) Conversely, to any finite-dimensional Lie algebra over the real or complex numbers, there is a corresponding connected Lie group, unique up to covering spaces (Lie's third theorem). This correspondence allows one to study the structure and classification of Lie groups in terms of Lie algebras, which are simpler objects of linear algebra.

In more detail: for any Lie group, the multiplication operation near the identity element 1 is commutative to first order. In other words, every Lie group G is (to first order) approximately a real vector space, namely the tangent space to G at the identity. To second order, the group operation may be non-commutative, and the second-order terms describing the non-commutativity of G near the identity give the structure of a Lie algebra. It is a remarkable fact that these second-order terms (the Lie algebra) completely determine the group structure of G near the identity. They even determine G globally, up to covering spaces.

In physics, Lie groups appear as symmetry groups of physical systems, and their Lie algebras (tangent vectors near the identity) may be thought of as infinitesimal symmetry motions. Thus Lie algebras and their representations are used extensively in physics, notably in quantum mechanics and particle physics.

An elementary example (not directly coming from an associative algebra) is the 3-dimensional space with Lie bracket defined by the cross product This is skew-symmetric since , and instead of associativity it satisfies the Jacobi identity:

This is the Lie algebra of the Lie group of rotations of space, and each vector may be pictured as an infinitesimal rotation around the axis , with angular speed equal to the magnitude of . The Lie bracket is a measure of the non-commutativity between two rotations. Since a rotation commutes with itself, one has the alternating property .

History

Lie algebras were introduced to study the concept of infinitesimal transformations by Sophus Lie in the 1870s, and independently discovered by Wilhelm Killing in the 1880s. The name Lie algebra was given by Hermann Weyl in the 1930s; in older texts, the term infinitesimal group was used.

Definition of a Lie algebra

A Lie algebra is a vector space over a field together with a binary operation called the Lie bracket, satisfying the following axioms:

- Bilinearity,

- for all scalars in and all elements in .

- The Alternating property,

- for all in .

- The Jacobi identity,

- for all in .

Given a Lie group, the Jacobi identity for its Lie algebra follows from the associativity of the group operation.

Using bilinearity to expand the Lie bracket and using the alternating property shows that for all in . Thus bilinearity and the alternating property together imply

- for all in . If the field does not have characteristic 2, then anticommutativity implies the alternating property, since it implies

It is customary to denote a Lie algebra by a lower-case fraktur letter such as . If a Lie algebra is associated with a Lie group, then the algebra is denoted by the fraktur version of the group's name: for example, the Lie algebra of SU(n) is .

Generators and dimension

The dimension of a Lie algebra over a field means its dimension as a vector space. In physics, a vector space basis of the Lie algebra of a Lie group G may be called a set of generators for G. (They are "infinitesimal generators" for G, so to speak.) In mathematics, a set S of generators for a Lie algebra means a subset of such that any Lie subalgebra (as defined below) that contains S must be all of . Equivalently, is spanned (as a vector space) by all iterated brackets of elements of S.

Basic examples

Abelian Lie algebras

Any vector space endowed with the identically zero Lie bracket becomes a Lie algebra. Such a Lie algebra is called abelian. Every one-dimensional Lie algebra is abelian, by the alternating property of the Lie bracket.

The Lie algebra of matrices

- On an associative algebra over a field with multiplication written as , a Lie bracket may be defined by the commutator . With this bracket, is a Lie algebra. (The Jacobi identity follows from the associativity of the multiplication on .)

- The endomorphism ring of an -vector space with the above Lie bracket is denoted .

- For a field F and a positive integer n, the space of n × n matrices over F, denoted or , is a Lie algebra with bracket given by the commutator of matrices: . This is a special case of the previous example; it is a key example of a Lie algebra. It is called the general linear Lie algebra.

- When F is the real numbers, is the Lie algebra of the general linear group , the group of invertible n x n real matrices (or equivalently, matrices with nonzero determinant), where the group operation is matrix multiplication. Likewise, is the Lie algebra of the complex Lie group . The Lie bracket on describes the failure of commutativity for matrix multiplication, or equivalently for the composition of linear maps. For any field F, can be viewed as the Lie algebra of the algebraic group over F.

Definitions

Subalgebras, ideals and homomorphisms

The Lie bracket is not required to be associative, meaning that need not be equal to . Nonetheless, much of the terminology for associative rings and algebras (and also for groups) has analogs for Lie algebras. A Lie subalgebra is a linear subspace which is closed under the Lie bracket. An ideal is a linear subspace that satisfies the stronger condition:

In the correspondence between Lie groups and Lie algebras, subgroups correspond to Lie subalgebras, and normal subgroups correspond to ideals.

A Lie algebra homomorphism is a linear map compatible with the respective Lie brackets:

An isomorphism of Lie algebras is a bijective homomorphism.

As with normal subgroups in groups, ideals in Lie algebras are precisely the kernels of homomorphisms. Given a Lie algebra and an ideal in it, the quotient Lie algebra is defined, with a surjective homomorphism of Lie algebras. The first isomorphism theorem holds for Lie algebras: for any homomorphism of Lie algebras, the image of is a Lie subalgebra of that is isomorphic to .

For the Lie algebra of a Lie group, the Lie bracket is a kind of infinitesimal commutator. As a result, for any Lie algebra, two elements are said to commute if their bracket vanishes: .

The centralizer subalgebra of a subset is the set of elements commuting with : that is, . The centralizer of itself is the center . Similarly, for a subspace S, the normalizer subalgebra of is . If is a Lie subalgebra, is the largest subalgebra such that is an ideal of .

Example

The subspace of diagonal matrices in is an abelian Lie subalgebra. (It is a Cartan subalgebra of , analogous to a maximal torus in the theory of compact Lie groups.) Here is not an ideal in for . For example, when , this follows from the calculation:

(which is not always in ).

Every one-dimensional linear subspace of a Lie algebra is an abelian Lie subalgebra, but it need not be an ideal.

Product and semidirect product

For two Lie algebras and , the product Lie algebra is the vector space consisting of all ordered pairs , with Lie bracket

This is the product in the category of Lie algebras. Note that the copies of and in commute with each other:

Let be a Lie algebra and an ideal of . If the canonical map splits (i.e., admits a section , as a homomorphism of Lie algebras), then is said to be a semidirect product of and , . See also semidirect sum of Lie algebras.

Derivations

For an algebra A over a field F, a derivation of A over F is a linear map that satisfies the Leibniz rule

for all . (The definition makes sense for a possibly non-associative algebra.) Given two derivations and , their commutator is again a derivation. This operation makes the space of all derivations of A over F into a Lie algebra.

Informally speaking, the space of derivations of A is the Lie algebra of the automorphism group of A. (This is literally true when the automorphism group is a Lie group, for example when F is the real numbers and A has finite dimension as a vector space.) For this reason, spaces of derivations are a natural way to construct Lie algebras: they are the "infinitesimal automorphisms" of A. Indeed, writing out the condition that

(where 1 denotes the identity map on A) gives exactly the definition of D being a derivation.

Example: the Lie algebra of vector fields. Let A be the ring of smooth functions on a smooth manifold X. Then a derivation of A over is equivalent to a vector field on X. (A vector field v gives a derivation of the space of smooth functions by differentiating functions in the direction of v.) This makes the space of vector fields into a Lie algebra (see Lie bracket of vector fields). Informally speaking, is the Lie algebra of the diffeomorphism group of X. So the Lie bracket of vector fields describes the non-commutativity of the diffeomorphism group. An action of a Lie group G on a manifold X determines a homomorphism of Lie algebras . (An example is illustrated below.)

A Lie algebra can be viewed as a non-associative algebra, and so each Lie algebra over a field F determines its Lie algebra of derivations, . That is, a derivation of is a linear map such that

- .

The inner derivation associated to any is the adjoint mapping defined by . (This is a derivation as a consequence of the Jacobi identity.) That gives a homomorphism of Lie algebras, . The image is an ideal in , and the Lie algebra of outer derivations is defined as the quotient Lie algebra, . (This is exactly analogous to the outer automorphism group of a group.) For a semisimple Lie algebra (defined below) over a field of characteristic zero, every derivation is inner. This is related to the theorem that the outer automorphism group of a semisimple Lie group is finite.

In contrast, an abelian Lie algebra has many outer derivations. Namely, for a vector space with Lie bracket zero, the Lie algebra can be identified with .

Examples

Matrix Lie algebras

A matrix group is a Lie group consisting of invertible matrices, , where the group operation of G is matrix multiplication. The corresponding Lie algebra is the space of matrices which are tangent vectors to G inside the linear space : this consists of derivatives of smooth curves in G at the identity matrix :

The Lie bracket of is given by the commutator of matrices, . Given a Lie algebra , one can recover the Lie group as the subgroup generated by the matrix exponential of elements of . (To be precise, this gives the identity component of G, if G is not connected.) Here the exponential mapping is defined by , which converges for every matrix .

The same comments apply to complex Lie subgroups of and the complex matrix exponential, (defined by the same formula).

Here are some matrix Lie groups and their Lie algebras.

- For a positive integer n, the special linear group consists of all real n × n matrices with determinant 1. This is the group of linear maps from to itself that preserve volume and orientation. More abstractly, is the commutator subgroup of the general linear group . Its Lie algebra consists of all real n × n matrices with trace 0. Similarly, one can define the analogous complex Lie group and its Lie algebra .

- The orthogonal group plays a basic role in geometry: it is the group of linear maps from to itself that preserve the length of vectors. For example, rotations and reflections belong to . Equivalently, this is the group of n x n orthogonal matrices, meaning that , where denotes the transpose of a matrix. The orthogonal group has two connected components; the identity component is called the special orthogonal group , consisting of the orthogonal matrices with determinant 1. Both groups have the same Lie algebra , the subspace of skew-symmetric matrices in (). See also infinitesimal rotations with skew-symmetric matrices.

- The complex orthogonal group , its identity component , and the Lie algebra are given by the same formulas applied to n x n complex matrices. Equivalently, is the subgroup of that preserves the standard symmetric bilinear form on .

- The unitary group is the subgroup of that preserves the length of vectors in (with respect to the standard Hermitian inner product). Equivalently, this is the group of n × n unitary matrices (satisfying , where denotes the conjugate transpose of a matrix). Its Lie algebra consists of the skew-hermitian matrices in (). This is a Lie algebra over , not over . (Indeed, i times a skew-hermitian matrix is hermitian, rather than skew-hermitian.) Likewise, the unitary group is a real Lie subgroup of the complex Lie group . For example, is the circle group, and its Lie algebra (from this point of view) is .

- The special unitary group is the subgroup of matrices with determinant 1 in . Its Lie algebra consists of the skew-hermitian matrices with trace zero.

- The symplectic group is the subgroup of that preserves the standard alternating bilinear form on . Its Lie algebra is the symplectic Lie algebra .

- The classical Lie algebras are those listed above, along with variants over any field.

Two dimensions

Some Lie algebras of low dimension are described here. See the classification of low-dimensional real Lie algebras for further examples.

- There is a unique nonabelian Lie algebra of dimension 2 over any field F, up to isomorphism. Here has a basis for which the bracket is given by . (This determines the Lie bracket completely, because the axioms imply that and .) Over the real numbers, can be viewed as the Lie algebra of the Lie group of affine transformations of the real line, .

- The affine group G can be identified with the group of matrices

- under matrix multiplication, with , . Its Lie algebra is the Lie subalgebra of consisting of all matrices

- In these terms, the basis above for is given by the matrices

- For any field , the 1-dimensional subspace is an ideal in the 2-dimensional Lie algebra , by the formula . Both of the Lie algebras and are abelian (because 1-dimensional). In this sense, can be broken into abelian "pieces", meaning that it is solvable (though not nilpotent), in the terminology below.

Three dimensions

- The Heisenberg algebra over a field F is the three-dimensional Lie algebra with a basis such that

- .

- It can be viewed as the Lie algebra of 3×3 strictly upper-triangular matrices, with the commutator Lie bracket and the basis

- Over the real numbers, is the Lie algebra of the Heisenberg group , that is, the group of matrices

- under matrix multiplication.

- For any field F, the center of is the 1-dimensional ideal , and the quotient is abelian, isomorphic to . In the terminology below, it follows that is nilpotent (though not abelian).

- The Lie algebra of the rotation group SO(3) is the space of skew-symmetric 3 x 3 matrices over . A basis is given by the three matrices

- The commutation relations among these generators are

- The cross product of vectors in is given by the same formula in terms of the standard basis; so that Lie algebra is isomorphic to . Also, is equivalent to the Spin (physics) angular-momentum component operators for spin-1 particles in quantum mechanics.

- The Lie algebra cannot be broken into pieces in the way that the previous examples can: it is simple, meaning that it is not abelian and its only ideals are 0 and all of .

- Another simple Lie algebra of dimension 3, in this case over , is the space of 2 x 2 matrices of trace zero. A basis is given by the three matrices

H

H E

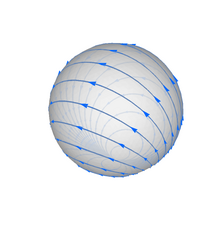

E FThe action of on the Riemann sphere . In particular, the Lie brackets of the vector fields shown are: , , .

FThe action of on the Riemann sphere . In particular, the Lie brackets of the vector fields shown are: , , .

- The Lie bracket is given by:

- Using these formulas, one can show that the Lie algebra is simple, and classify its finite-dimensional representations (defined below). In the terminology of quantum mechanics, one can think of E and F as raising and lowering operators. Indeed, for any representation of , the relations above imply that E maps the c-eigenspace of H (for a complex number c) into the -eigenspace, while F maps the c-eigenspace into the -eigenspace.

- The Lie algebra is isomorphic to the complexification of , meaning the tensor product . The formulas for the Lie bracket are easier to analyze in the case of . As a result, it is common to analyze complex representations of the group by relating them to representations of the Lie algebra .

Infinite dimensions

- The Lie algebra of vector fields on a smooth manifold of positive dimension is an infinite-dimensional Lie algebra over .

- The Kac–Moody algebras are a large class of infinite-dimensional Lie algebras, say over , with structure much like that of the finite-dimensional simple Lie algebras (such as ).

- The Moyal algebra is an infinite-dimensional Lie algebra that contains all the classical Lie algebras as subalgebras.

- The Virasoro algebra is important in string theory.

- The functor that takes a Lie algebra over a field F to the underlying vector space has a left adjoint , called the free Lie algebra on a vector space V. It is spanned by all iterated Lie brackets of elements of V, modulo only the relations coming from the definition of a Lie algebra. The free Lie algebra is infinite-dimensional for V of dimension at least 2.

Representations

Main article: Lie algebra representationDefinitions

Given a vector space V, let denote the Lie algebra consisting of all linear maps from V to itself, with bracket given by . A representation of a Lie algebra on V is a Lie algebra homomorphism

That is, sends each element of to a linear map from V to itself, in such a way that the Lie bracket on corresponds to the commutator of linear maps.

A representation is said to be faithful if its kernel is zero. Ado's theorem states that every finite-dimensional Lie algebra over a field of characteristic zero has a faithful representation on a finite-dimensional vector space. Kenkichi Iwasawa extended this result to finite-dimensional Lie algebras over a field of any characteristic. Equivalently, every finite-dimensional Lie algebra over a field F is isomorphic to a Lie subalgebra of for some positive integer n.

Adjoint representation

For any Lie algebra , the adjoint representation is the representation

given by . (This is a representation of by the Jacobi identity.)

Goals of representation theory

One important aspect of the study of Lie algebras (especially semisimple Lie algebras, as defined below) is the study of their representations. Although Ado's theorem is an important result, the primary goal of representation theory is not to find a faithful representation of a given Lie algebra . Indeed, in the semisimple case, the adjoint representation is already faithful. Rather, the goal is to understand all possible representations of . For a semisimple Lie algebra over a field of characteristic zero, Weyl's theorem says that every finite-dimensional representation is a direct sum of irreducible representations (those with no nontrivial invariant subspaces). The finite-dimensional irreducible representations are well understood from several points of view; see the representation theory of semisimple Lie algebras and the Weyl character formula.

Universal enveloping algebra

Main article: Universal enveloping algebraThe functor that takes an associative algebra A over a field F to A as a Lie algebra (by ) has a left adjoint , called the universal enveloping algebra. To construct this: given a Lie algebra over F, let

be the tensor algebra on , also called the free associative algebra on the vector space . Here denotes the tensor product of F-vector spaces. Let I be the two-sided ideal in generated by the elements for ; then the universal enveloping algebra is the quotient ring . It satisfies the Poincaré–Birkhoff–Witt theorem: if is a basis for as an F-vector space, then a basis for is given by all ordered products with natural numbers. In particular, the map is injective.

Representations of are equivalent to modules over the universal enveloping algebra. The fact that is injective implies that every Lie algebra (possibly of infinite dimension) has a faithful representation (of infinite dimension), namely its representation on . This also shows that every Lie algebra is contained in the Lie algebra associated to some associative algebra.

Representation theory in physics

The representation theory of Lie algebras plays an important role in various parts of theoretical physics. There, one considers operators on the space of states that satisfy certain natural commutation relations. These commutation relations typically come from a symmetry of the problem—specifically, they are the relations of the Lie algebra of the relevant symmetry group. An example is the angular momentum operators, whose commutation relations are those of the Lie algebra of the rotation group . Typically, the space of states is far from being irreducible under the pertinent operators, but one can attempt to decompose it into irreducible pieces. In doing so, one needs to know the irreducible representations of the given Lie algebra. In the study of the hydrogen atom, for example, quantum mechanics textbooks classify (more or less explicitly) the finite-dimensional irreducible representations of the Lie algebra .

Structure theory and classification

Lie algebras can be classified to some extent. This is a powerful approach to the classification of Lie groups.

Abelian, nilpotent, and solvable

Analogously to abelian, nilpotent, and solvable groups, one can define abelian, nilpotent, and solvable Lie algebras.

A Lie algebra is abelian if the Lie bracket vanishes; that is, = 0 for all x and y in . In particular, the Lie algebra of an abelian Lie group (such as the group under addition or the torus group ) is abelian. Every finite-dimensional abelian Lie algebra over a field is isomorphic to for some , meaning an n-dimensional vector space with Lie bracket zero.

A more general class of Lie algebras is defined by the vanishing of all commutators of given length. First, the commutator subalgebra (or derived subalgebra) of a Lie algebra is , meaning the linear subspace spanned by all brackets with . The commutator subalgebra is an ideal in , in fact the smallest ideal such that the quotient Lie algebra is abelian. It is analogous to the commutator subgroup of a group.

A Lie algebra is nilpotent if the lower central series

becomes zero after finitely many steps. Equivalently, is nilpotent if there is a finite sequence of ideals in ,

such that is central in for each j. By Engel's theorem, a Lie algebra over any field is nilpotent if and only if for every u in the adjoint endomorphism

is nilpotent.

More generally, a Lie algebra is said to be solvable if the derived series:

becomes zero after finitely many steps. Equivalently, is solvable if there is a finite sequence of Lie subalgebras,

such that is an ideal in with abelian for each j.

Every finite-dimensional Lie algebra over a field has a unique maximal solvable ideal, called its radical. Under the Lie correspondence, nilpotent (respectively, solvable) Lie groups correspond to nilpotent (respectively, solvable) Lie algebras over .

For example, for a positive integer n and a field F of characteristic zero, the radical of is its center, the 1-dimensional subspace spanned by the identity matrix. An example of a solvable Lie algebra is the space of upper-triangular matrices in ; this is not nilpotent when . An example of a nilpotent Lie algebra is the space of strictly upper-triangular matrices in ; this is not abelian when .

Simple and semisimple

Main article: Semisimple Lie algebraA Lie algebra is called simple if it is not abelian and the only ideals in are 0 and . (In particular, a one-dimensional—necessarily abelian—Lie algebra is by definition not simple, even though its only ideals are 0 and .) A finite-dimensional Lie algebra is called semisimple if the only solvable ideal in is 0. In characteristic zero, a Lie algebra is semisimple if and only if it is isomorphic to a product of simple Lie algebras, .

For example, the Lie algebra is simple for every and every field F of characteristic zero (or just of characteristic not dividing n). The Lie algebra over is simple for every . The Lie algebra over is simple if or . (There are "exceptional isomorphisms" and .)

The concept of semisimplicity for Lie algebras is closely related with the complete reducibility (semisimplicity) of their representations. When the ground field F has characteristic zero, every finite-dimensional representation of a semisimple Lie algebra is semisimple (that is, a direct sum of irreducible representations).

A finite-dimensional Lie algebra over a field of characteristic zero is called reductive if its adjoint representation is semisimple. Every reductive Lie algebra is isomorphic to the product of an abelian Lie algebra and a semisimple Lie algebra.

For example, is reductive for F of characteristic zero: for , it is isomorphic to the product

where F denotes the center of , the 1-dimensional subspace spanned by the identity matrix. Since the special linear Lie algebra is simple, contains few ideals: only 0, the center F, , and all of .

Cartan's criterion

Cartan's criterion (by Élie Cartan) gives conditions for a finite-dimensional Lie algebra of characteristic zero to be solvable or semisimple. It is expressed in terms of the Killing form, the symmetric bilinear form on defined by

where tr denotes the trace of a linear operator. Namely: a Lie algebra is semisimple if and only if the Killing form is nondegenerate. A Lie algebra is solvable if and only if

Classification

The Levi decomposition asserts that every finite-dimensional Lie algebra over a field of characteristic zero is a semidirect product of its solvable radical and a semisimple Lie algebra. Moreover, a semisimple Lie algebra in characteristic zero is a product of simple Lie algebras, as mentioned above. This focuses attention on the problem of classifying the simple Lie algebras.

The simple Lie algebras of finite dimension over an algebraically closed field F of characteristic zero were classified by Killing and Cartan in the 1880s and 1890s, using root systems. Namely, every simple Lie algebra is of type An, Bn, Cn, Dn, E6, E7, E8, F4, or G2. Here the simple Lie algebra of type An is , Bn is , Cn is , and Dn is . The other five are known as the exceptional Lie algebras.

The classification of finite-dimensional simple Lie algebras over is more complicated, but it was also solved by Cartan (see simple Lie group for an equivalent classification). One can analyze a Lie algebra over by considering its complexification .

In the years leading up to 2004, the finite-dimensional simple Lie algebras over an algebraically closed field of characteristic were classified by Richard Earl Block, Robert Lee Wilson, Alexander Premet, and Helmut Strade. (See restricted Lie algebra#Classification of simple Lie algebras.) It turns out that there are many more simple Lie algebras in positive characteristic than in characteristic zero.

Relation to Lie groups

Main article: Lie group–Lie algebra correspondence

Although Lie algebras can be studied in their own right, historically they arose as a means to study Lie groups.

The relationship between Lie groups and Lie algebras can be summarized as follows. Each Lie group determines a Lie algebra over (concretely, the tangent space at the identity). Conversely, for every finite-dimensional Lie algebra , there is a connected Lie group with Lie algebra . This is Lie's third theorem; see the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula. This Lie group is not determined uniquely; however, any two Lie groups with the same Lie algebra are locally isomorphic, and more strongly, they have the same universal cover. For instance, the special orthogonal group SO(3) and the special unitary group SU(2) have isomorphic Lie algebras, but SU(2) is a simply connected double cover of SO(3).

For simply connected Lie groups, there is a complete correspondence: taking the Lie algebra gives an equivalence of categories from simply connected Lie groups to Lie algebras of finite dimension over .

The correspondence between Lie algebras and Lie groups is used in several ways, including in the classification of Lie groups and the representation theory of Lie groups. For finite-dimensional representations, there is an equivalence of categories between representations of a real Lie algebra and representations of the corresponding simply connected Lie group. This simplifies the representation theory of Lie groups: it is often easier to classify the representations of a Lie algebra, using linear algebra.

Every connected Lie group is isomorphic to its universal cover modulo a discrete central subgroup. So classifying Lie groups becomes simply a matter of counting the discrete subgroups of the center, once the Lie algebra is known. For example, the real semisimple Lie algebras were classified by Cartan, and so the classification of semisimple Lie groups is well understood.

For infinite-dimensional Lie algebras, Lie theory works less well. The exponential map need not be a local homeomorphism (for example, in the diffeomorphism group of the circle, there are diffeomorphisms arbitrarily close to the identity that are not in the image of the exponential map). Moreover, in terms of the existing notions of infinite-dimensional Lie groups, some infinite-dimensional Lie algebras do not come from any group.

Lie theory also does not work so neatly for infinite-dimensional representations of a finite-dimensional group. Even for the additive group , an infinite-dimensional representation of can usually not be differentiated to produce a representation of its Lie algebra on the same space, or vice versa. The theory of Harish-Chandra modules is a more subtle relation between infinite-dimensional representations for groups and Lie algebras.

Real form and complexification

Given a complex Lie algebra , a real Lie algebra is said to be a real form of if the complexification is isomorphic to . A real form need not be unique; for example, has two real forms up to isomorphism, and .

Given a semisimple complex Lie algebra , a split form of it is a real form that splits; i.e., it has a Cartan subalgebra which acts via an adjoint representation with real eigenvalues. A split form exists and is unique (up to isomorphism). A compact form is a real form that is the Lie algebra of a compact Lie group. A compact form exists and is also unique up to isomorphism.

Lie algebra with additional structures

A Lie algebra may be equipped with additional structures that are compatible with the Lie bracket. For example, a graded Lie algebra is a Lie algebra (or more generally a Lie superalgebra) with a compatible grading. A differential graded Lie algebra also comes with a differential, making the underlying vector space a chain complex.

For example, the homotopy groups of a simply connected topological space form a graded Lie algebra, using the Whitehead product. In a related construction, Daniel Quillen used differential graded Lie algebras over the rational numbers to describe rational homotopy theory in algebraic terms.

Lie ring

The definition of a Lie algebra over a field extends to define a Lie algebra over any commutative ring R. Namely, a Lie algebra over R is an R-module with an alternating R-bilinear map that satisfies the Jacobi identity. A Lie algebra over the ring of integers is sometimes called a Lie ring. (This is not directly related to the notion of a Lie group.)

Lie rings are used in the study of finite p-groups (for a prime number p) through the Lazard correspondence. The lower central factors of a finite p-group are finite abelian p-groups. The direct sum of the lower central factors is given the structure of a Lie ring by defining the bracket to be the commutator of two coset representatives; see the example below.

p-adic Lie groups are related to Lie algebras over the field of p-adic numbers as well as over the ring of p-adic integers. Part of Claude Chevalley's construction of the finite groups of Lie type involves showing that a simple Lie algebra over the complex numbers comes from a Lie algebra over the integers, and then (with more care) a group scheme over the integers.

Examples

- Here is a construction of Lie rings arising from the study of abstract groups. For elements of a group, define the commutator . Let be a filtration of a group , that is, a chain of subgroups such that is contained in for all . (For the Lazard correspondence, one takes the filtration to be the lower central series of G.) Then

- is a Lie ring, with addition given by the group multiplication (which is abelian on each quotient group ), and with Lie bracket given by commutators in the group:

- For example, the Lie ring associated to the lower central series on the dihedral group of order 8 is the Heisenberg Lie algebra of dimension 3 over the field .

Definition using category-theoretic notation

The definition of a Lie algebra can be reformulated more abstractly in the language of category theory. Namely, one can define a Lie algebra in terms of linear maps—that is, morphisms in the category of vector spaces—without considering individual elements. (In this section, the field over which the algebra is defined is assumed to be of characteristic different from 2.)

For the category-theoretic definition of Lie algebras, two braiding isomorphisms are needed. If A is a vector space, the interchange isomorphism is defined by

The cyclic-permutation braiding is defined as

where is the identity morphism. Equivalently, is defined by

With this notation, a Lie algebra can be defined as an object in the category of vector spaces together with a morphism

that satisfies the two morphism equalities

and

See also

- Affine Lie algebra

- Automorphism of a Lie algebra

- Frobenius integrability theorem (the integrability being the same as being a Lie subalgebra)

- Gelfand–Fuks cohomology

- Hopf algebra

- Index of a Lie algebra

- Leibniz algebra

- Lie algebra cohomology

- Lie algebra extension

- Lie algebra representation

- Lie bialgebra

- Lie coalgebra

- Lie n-algebra

- Lie operad

- Particle physics and representation theory

- Lie superalgebra

- Orthogonal symmetric Lie algebra

- Poisson algebra

- Pre-Lie algebra

- Quantum groups

- Moyal algebra

- Quasi-Frobenius Lie algebra

- Quasi-Lie algebra

- Restricted Lie algebra

- Serre relations

Remarks

- More generally, one has the notion of a Lie algebra over any commutative ring R: an R-module with an alternating R-bilinear map that satisfies the Jacobi identity (Bourbaki (1989, Section 2)).

References

- O'Connor & Robertson 2000.

- O'Connor & Robertson 2005.

- Humphreys 1978, p. 1.

- Bourbaki 1989, §1.2. Example 1.

- Bourbaki 1989, §1.2. Example 2.

- By the anticommutativity of the commutator, the notions of a left and right ideal in a Lie algebra coincide.

- Jacobson 1979, p. 28.

- Bourbaki 1989, section I.1.1.

- Humphreys 1978, p. 4.

- Varadarajan 1984, p. 49.

- Serre 2006, Part I, section VI.3.

- Fulton & Harris 1991, Proposition D.40.

- Varadarajan 1984, section 2.10, Remark 2.

- Hall 2015, §3.4.

- Erdmann & Wildon 2006, Theorem 3.1.

- Erdmann & Wildon 2006, section 3.2.1.

- Hall 2015, Example 3.27.

- ^ Wigner 1959, Chapters 17 and 20.

- Erdmann & Wildon 2006, Chapter 8.

- Serre 2006, Part I, Chapter IV.

- Jacobson 1979, Ch. VI.

- ^ Hall 2015, Theorem 10.9.

- Humphreys 1978, section 17.3.

- Jacobson 1979, section II.3.

- Jacobson 1979, section I.7.

- Jacobson 1979, p. 24.

- Jacobson 1979, Ch. III, § 5.

- Erdmann & Wildon 2006, Theorem 12.1.

- Varadarajan 1984, Theorem 3.16.3.

- Varadarajan 1984, section 3.9.

- Jacobson 1979, Ch. III, § 9.

- Jacobson 1979, section IV.6.

- Varadarajan 1984, Theorems 2.7.5 and 3.15.1.

- Varadarajan 1984, section 2.6.

- Milnor 2010, Warnings 1.6 and 8.5.

- Knapp 2001, section III.3, Problem III.5.

- ^ Fulton & Harris 1991, §26.1.

- Quillen 1969, Corollary II.6.2.

- Khukhro 1998, Ch. 6.

- Serre 2006, Part II, section V.1.

- Humphreys 1978, section 25.

- Serre 2006, Part I, Chapter II.

Sources

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1989). Lie Groups and Lie Algebras: Chapters 1-3. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-64242-8. MR 1728312.

- Erdmann, Karin; Wildon, Mark (2006). Introduction to Lie Algebras. Springer. ISBN 1-84628-040-0. MR 2218355.

- Fulton, William; Harris, Joe (1991). Representation theory. A first course. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Readings in Mathematics. Vol. 129. New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0979-9. ISBN 978-0-387-97495-8. MR 1153249. OCLC 246650103.

- Hall, Brian C. (2015). Lie groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 222 (2nd ed.). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13467-3. ISBN 978-3319134666. ISSN 0072-5285. MR 3331229.

- Humphreys, James E. (1978). Introduction to Lie Algebras and Representation Theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90053-7. MR 0499562.

- Jacobson, Nathan (1979) . Lie Algebras. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-63832-4. MR 0559927.

- Khukhro, E. I. (1998), p-Automorphisms of Finite p-Groups, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511526008, ISBN 0-521-59717-X, MR 1615819

- Knapp, Anthony W. (2001) , Representation Theory of Semisimple Groups: an Overview Based on Examples, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-09089-0, MR 1880691

- Milnor, John (2010) , "Remarks on infinite-dimensional Lie groups", Collected Papers of John Milnor, vol. 5, pp. 91–141, ISBN 978-0-8218-4876-0, MR 0830252

- O'Connor, J.J; Robertson, E.F. (2000). "Marius Sophus Lie". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive.

- O'Connor, J.J; Robertson, E.F. (2005). "Wilhelm Karl Joseph Killing". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive.

- Quillen, Daniel (1969), "Rational homotopy theory", Annals of Mathematics, 90 (2): 205–295, doi:10.2307/1970725, JSTOR 1970725, MR 0258031

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (2006). Lie Algebras and Lie Groups (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-55008-2. MR 2179691.

- Varadarajan, Veeravalli S. (1984) . Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Their Representations. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-90969-1. MR 0746308.

- Wigner, Eugene (1959). Group Theory and its Application to the Quantum Mechanics of Atomic Spectra. Translated by J. J. Griffin. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0127505503. MR 0106711.

External links

- Kac, Victor G.; et al. Course notes for MIT 18.745: Introduction to Lie Algebras. Archived from the original on 2010-04-20.

- "Lie algebra", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001

- McKenzie, Douglas (2015). "An Elementary Introduction to Lie Algebras for Physicists".

together with an operation called the Lie bracket, an

together with an operation called the Lie bracket, an  , that satisfies the

, that satisfies the  and

and  is denoted

is denoted  . A Lie algebra is typically a

. A Lie algebra is typically a  .

.

with Lie bracket defined by the

with Lie bracket defined by the  This is skew-symmetric since

This is skew-symmetric since  , and instead of associativity it satisfies the Jacobi identity:

, and instead of associativity it satisfies the Jacobi identity:

may be pictured as an infinitesimal rotation around the axis

may be pictured as an infinitesimal rotation around the axis  , with angular speed equal to the magnitude

of

, with angular speed equal to the magnitude

of  .

.

over a

over a  together with a

together with a  called the Lie bracket, satisfying the following axioms:

called the Lie bracket, satisfying the following axioms:

in

in  in

in

![{\displaystyle ]+]+]=0\ }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/24d0a47764d6b33c7ede3e20eabb0d9b85004387)

and using the alternating property shows that

and using the alternating property shows that  for all

for all  in

in

. If a Lie algebra is associated with a Lie group, then the algebra is denoted by the fraktur version of the group's name: for example, the Lie algebra of

. If a Lie algebra is associated with a Lie group, then the algebra is denoted by the fraktur version of the group's name: for example, the Lie algebra of  .

.

endowed with the identically zero Lie bracket becomes a Lie algebra. Such a Lie algebra is called abelian. Every one-dimensional Lie algebra is abelian, by the alternating property of the Lie bracket.

endowed with the identically zero Lie bracket becomes a Lie algebra. Such a Lie algebra is called abelian. Every one-dimensional Lie algebra is abelian, by the alternating property of the Lie bracket.

over a field

over a field  , a Lie bracket may be defined by the commutator

, a Lie bracket may be defined by the commutator  .

. or

or  , is a Lie algebra with bracket given by the commutator of matrices:

, is a Lie algebra with bracket given by the commutator of matrices:  . This is a special case of the previous example; it is a key example of a Lie algebra. It is called the general linear Lie algebra.

. This is a special case of the previous example; it is a key example of a Lie algebra. It is called the general linear Lie algebra. is the Lie algebra of the

is the Lie algebra of the  , the group of

, the group of  is the Lie algebra of the complex Lie group

is the Lie algebra of the complex Lie group  . The Lie bracket on

. The Lie bracket on  over F.

over F.![{\displaystyle ,z]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5d1355c94372444268d5200cf3079e4b2e8c5510) need not be equal to

need not be equal to ![{\displaystyle ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/99c3a3b210ab676378107460425cdcd01b90d839) . Nonetheless, much of the terminology for associative

. Nonetheless, much of the terminology for associative  which is closed under the Lie bracket. An ideal

which is closed under the Lie bracket. An ideal  is a linear subspace that satisfies the stronger condition:

is a linear subspace that satisfies the stronger condition:

in it, the quotient Lie algebra

in it, the quotient Lie algebra  is defined, with a surjective homomorphism

is defined, with a surjective homomorphism  of Lie algebras. The

of Lie algebras. The  of Lie algebras, the image of

of Lie algebras, the image of  is a Lie subalgebra of

is a Lie subalgebra of  that is isomorphic to

that is isomorphic to  .

.

are said to commute if their bracket vanishes:

are said to commute if their bracket vanishes:  .

.

is the set of elements commuting with

is the set of elements commuting with  : that is,

: that is,  . The centralizer of

. The centralizer of  . Similarly, for a subspace S, the

. Similarly, for a subspace S, the  . If

. If  is the largest subalgebra such that

is the largest subalgebra such that  of diagonal matrices in

of diagonal matrices in  , analogous to a

, analogous to a  . For example, when

. For example, when  , this follows from the calculation:

, this follows from the calculation:

).

).

, the

, the  consisting of all ordered pairs

consisting of all ordered pairs  , with Lie bracket

, with Lie bracket

in

in

, as a homomorphism of Lie algebras), then

, as a homomorphism of Lie algebras), then  . See also

. See also  that satisfies the

that satisfies the

. (The definition makes sense for a possibly

. (The definition makes sense for a possibly  and

and  , their commutator

, their commutator  is again a derivation. This operation makes the space

is again a derivation. This operation makes the space  of all derivations of A over F into a Lie algebra.

of all derivations of A over F into a Lie algebra.

of

of  is equivalent to a

is equivalent to a  of vector fields into a Lie algebra (see

of vector fields into a Lie algebra (see  . (An example is illustrated below.)

. (An example is illustrated below.)

. That is, a derivation of

. That is, a derivation of  such that

such that

.

. is the adjoint mapping

is the adjoint mapping  defined by

defined by  . (This is a derivation as a consequence of the Jacobi identity.) That gives a homomorphism of Lie algebras,

. (This is a derivation as a consequence of the Jacobi identity.) That gives a homomorphism of Lie algebras,  . The image

. The image  is an ideal in

is an ideal in  . (This is exactly analogous to the

. (This is exactly analogous to the  can be identified with

can be identified with  , where the group operation of G is matrix multiplication. The corresponding Lie algebra

, where the group operation of G is matrix multiplication. The corresponding Lie algebra  : this consists of derivatives of smooth curves in G at the

: this consists of derivatives of smooth curves in G at the  :

:

, one can recover the Lie group as the subgroup generated by the

, one can recover the Lie group as the subgroup generated by the  is defined by

is defined by  , which converges for every matrix

, which converges for every matrix  .

.

and the complex matrix exponential,

and the complex matrix exponential,  (defined by the same formula).

(defined by the same formula).

consists of all real n × n matrices with determinant 1. This is the group of linear maps from

consists of all real n × n matrices with determinant 1. This is the group of linear maps from  to itself that preserve volume and

to itself that preserve volume and  consists of all real n × n matrices with

consists of all real n × n matrices with  and its Lie algebra

and its Lie algebra  .

. plays a basic role in geometry: it is the group of linear maps from

plays a basic role in geometry: it is the group of linear maps from  , where

, where  denotes the

denotes the  , consisting of the orthogonal matrices with determinant 1. Both groups have the same Lie algebra

, consisting of the orthogonal matrices with determinant 1. Both groups have the same Lie algebra  , the subspace of skew-symmetric matrices in

, the subspace of skew-symmetric matrices in  ). See also

). See also  , its identity component

, its identity component  , and the Lie algebra

, and the Lie algebra  are given by the same formulas applied to n x n complex matrices. Equivalently,

are given by the same formulas applied to n x n complex matrices. Equivalently,  .

. is the subgroup of

is the subgroup of  , where

, where  denotes the

denotes the  consists of the skew-hermitian matrices in

consists of the skew-hermitian matrices in  ). This is a Lie algebra over

). This is a Lie algebra over  . (Indeed, i times a skew-hermitian matrix is hermitian, rather than skew-hermitian.) Likewise, the unitary group

. (Indeed, i times a skew-hermitian matrix is hermitian, rather than skew-hermitian.) Likewise, the unitary group  is the

is the  .

. is the subgroup of matrices with determinant 1 in

is the subgroup of matrices with determinant 1 in  consists of the skew-hermitian matrices with trace zero.

consists of the skew-hermitian matrices with trace zero. is the subgroup of

is the subgroup of  that preserves the standard

that preserves the standard  . Its Lie algebra is the

. Its Lie algebra is the  .

. for which the bracket is given by

for which the bracket is given by  . (This determines the Lie bracket completely, because the axioms imply that

. (This determines the Lie bracket completely, because the axioms imply that  and

and  .) Over the real numbers,

.) Over the real numbers,  of

of  .

.

,

,  . Its Lie algebra is the Lie subalgebra

. Its Lie algebra is the Lie subalgebra  consisting of all matrices

consisting of all matrices

is an ideal in the 2-dimensional Lie algebra

is an ideal in the 2-dimensional Lie algebra  . Both of the Lie algebras

. Both of the Lie algebras  are abelian (because 1-dimensional). In this sense,

are abelian (because 1-dimensional). In this sense,  over a field F is the three-dimensional Lie algebra with a basis

over a field F is the three-dimensional Lie algebra with a basis  such that

such that .

.

is the Lie algebra of the

is the Lie algebra of the  , that is, the group of matrices

, that is, the group of matrices

, and the quotient

, and the quotient  is abelian, isomorphic to

is abelian, isomorphic to  . In the terminology below, it follows that

. In the terminology below, it follows that  of the

of the

is given by the same formula in terms of the standard basis; so that Lie algebra is isomorphic to

is given by the same formula in terms of the standard basis; so that Lie algebra is isomorphic to  of 2 x 2 matrices of trace zero. A basis is given by the three matrices

of 2 x 2 matrices of trace zero. A basis is given by the three matrices

. In particular, the Lie brackets of the vector fields shown are:

. In particular, the Lie brackets of the vector fields shown are:  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

-eigenspace, while F maps the c-eigenspace into the

-eigenspace, while F maps the c-eigenspace into the  -eigenspace.

-eigenspace. . The formulas for the Lie bracket are easier to analyze in the case of

. The formulas for the Lie bracket are easier to analyze in the case of  by relating them to representations of the Lie algebra

by relating them to representations of the Lie algebra  , called the

, called the  is infinite-dimensional for V of dimension at least 2.

is infinite-dimensional for V of dimension at least 2.

sends each element of

sends each element of

. (This is a representation of

. (This is a representation of  ) has a

) has a  , called the universal enveloping algebra. To construct this: given a Lie algebra

, called the universal enveloping algebra. To construct this: given a Lie algebra

denotes the

denotes the  generated by the elements

generated by the elements  for

for  ; then the universal enveloping algebra is the quotient ring

; then the universal enveloping algebra is the quotient ring  . It satisfies the

. It satisfies the  is a basis for

is a basis for  is given by all ordered products

is given by all ordered products  with

with  natural numbers. In particular, the map

natural numbers. In particular, the map  is

is  ) is abelian. Every finite-dimensional abelian Lie algebra over a field

) is abelian. Every finite-dimensional abelian Lie algebra over a field  for some

for some  , meaning an n-dimensional vector space with Lie bracket zero.

, meaning an n-dimensional vector space with Lie bracket zero.

, meaning the linear subspace spanned by all brackets

, meaning the linear subspace spanned by all brackets ![{\displaystyle {\mathfrak {g}}\supseteq \supseteq ,{\mathfrak {g}}]\supseteq ,{\mathfrak {g}}],{\mathfrak {g}}]\supseteq \cdots }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/91dd572bb8c426d9126a9f99523ee5495b1ec1e5)

is central in

is central in  for each j. By

for each j. By

![{\displaystyle {\mathfrak {g}}\supseteq \supseteq ,]\supseteq ,],,]]\supseteq \cdots }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/70fe77ec47dc765341fa337ad4db0f7a2da49893)

is an ideal in

is an ideal in  with

with  abelian for each j.

abelian for each j.

of upper-triangular matrices in

of upper-triangular matrices in  of strictly upper-triangular matrices in

of strictly upper-triangular matrices in  .

.

.

.

is simple for every

is simple for every  or

or  . (There are "exceptional isomorphisms"

. (There are "exceptional isomorphisms"  and

and  .)

.)

, Bn is

, Bn is  , Cn is

, Cn is  , and Dn is

, and Dn is  . The other five are known as the

. The other five are known as the  .

.

were classified by

were classified by  with Lie algebra

with Lie algebra  , an infinite-dimensional representation of

, an infinite-dimensional representation of  is said to be a

is said to be a  is isomorphic to

is isomorphic to  and

and  .

.

to describe

to describe  that satisfies the Jacobi identity. A Lie algebra over the ring

that satisfies the Jacobi identity. A Lie algebra over the ring  . Let

. Let  be a filtration of a group

be a filtration of a group  is contained in

is contained in  for all

for all  . (For the Lazard correspondence, one takes the filtration to be the lower central series of G.) Then

. (For the Lazard correspondence, one takes the filtration to be the lower central series of G.) Then

), and with Lie bracket

), and with Lie bracket  given by commutators in the group:

given by commutators in the group:

.

. is defined by

is defined by

is defined as

is defined as

is the identity morphism. Equivalently,

is the identity morphism. Equivalently,  is defined by

is defined by