Medical condition

| Mesothelioma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Malignant mesothelioma |

| |

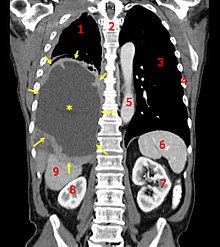

| CT scan showing a left sided mesothelioma with an enlarged mediastinal lymph node | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, swollen abdomen, chest wall pain, cough, feeling tired, weight loss |

| Complications | Fluid around the lung |

| Usual onset | Gradual onset |

| Causes | c. 40 years after exposure to asbestos |

| Risk factors | Genetics, possibly, infection with simian virus 40 |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging, examining fluid produced by the cancer, tissue biopsy |

| Prevention | Decreased asbestos exposure |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, pleurodesis |

| Prognosis | Five year survival c. 8–12% (US; varies by race) |

| Frequency | 60,800 (affected during 2015) |

| Deaths | 32,400 (2015) |

Mesothelioma is a type of cancer that develops from the thin layer of tissue that covers many of the internal organs (known as the mesothelium). The area most commonly affected is the lining of the lungs and chest wall. Less commonly the lining of the abdomen and rarely the sac surrounding the heart, or the sac surrounding each testis may be affected. Signs and symptoms of mesothelioma may include shortness of breath due to fluid around the lung, a swollen abdomen, chest wall pain, cough, feeling tired, and weight loss. These symptoms typically come on slowly.

More than 80% of mesothelioma cases are caused by exposure to asbestos. The greater the exposure, the greater the risk. As of 2013, about 125 million people worldwide have been exposed to asbestos at work. High rates of disease occur in people who mine asbestos, produce products from asbestos, work with asbestos products, live with asbestos workers, or work in buildings containing asbestos. Asbestos exposure and the onset of cancer are generally separated by about 40 years. Washing the clothing of someone who worked with asbestos also increases the risk. Other risk factors include genetics and infection with the simian virus 40. The diagnosis may be suspected based on chest X-ray and CT scan findings, and is confirmed by either examining fluid produced by the cancer or by a tissue biopsy of the cancer.

Prevention focuses on reducing exposure to asbestos. Treatment often includes surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. A procedure known as pleurodesis, which involves using substances such as talc to scar together the pleura, may be used to prevent more fluid from building up around the lungs. Chemotherapy often includes the medications cisplatin and pemetrexed. The percentage of people that survive five years following diagnosis is on average 8% in the United States.

In 2015, about 60,800 people had mesothelioma, and 32,000 died from the disease. Rates of mesothelioma vary in different areas of the world. Rates are higher in Australia, the United Kingdom, and lower in Japan. It occurs in about 3,000 people per year in the United States. It occurs more often in males than females. Rates of disease have increased since the 1950s. Diagnosis typically occurs after the age of 65 and most deaths occur around 70 years old. The disease was rare before the commercial use of asbestos.

Signs and symptoms

Lungs

Symptoms or signs of mesothelioma may not appear until 20 to 50 years (or more) after exposure to asbestos. Shortness of breath, cough, and pain in the chest due to an accumulation of fluid in the pleural space (pleural effusion) are often symptoms of pleural mesothelioma.

Mesothelioma that affects the pleura can cause these signs and symptoms:

- Chest wall pain

- Pleural effusion, or fluid surrounding the lung

- Shortness of breath – which could be due to a collapsed lung or the pleural effusion

- Fatigue or anemia

- Wheezing, hoarseness, or a cough

- Blood in the sputum (fluid) coughed up (hemoptysis)

In severe cases, the person may have many tumor masses. The individual may develop a pneumothorax, or collapse of the lung. The disease may metastasize, or spread to other parts of the body.

Abdomen

The most common symptoms of peritoneal mesothelioma are abdominal swelling and pain due to ascites (a buildup of fluid in the abdominal cavity). Other features may include weight loss, fever, night sweats, poor appetite, vomiting, constipation, and umbilical hernia. If the cancer has spread beyond the mesothelium to other parts of the body, symptoms may include pain, trouble swallowing, or swelling of the neck or face. These symptoms may be caused by mesothelioma or by other, less serious conditions.

Tumors that affect the abdominal cavity often do not cause symptoms until they are at a late stage. Symptoms include:

- Abdominal pain

- Ascites, or an abnormal buildup of fluid in the abdomen

- A mass in the abdomen

- Problems with bowel function

- Weight loss

Heart

Pericardial mesothelioma is not well characterized, but observed cases have included cardiac symptoms, specifically constrictive pericarditis, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and cardiac tamponade. They have also included nonspecific symptoms, including substernal chest pain, orthopnea (shortness of breath when lying flat), and cough. These symptoms are caused by the tumor encasing or infiltrating the heart.

End-stage

In severe cases of the disease, the following signs and symptoms may be present:

- Blood clots in the veins, which may cause thrombophlebitis

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation, a disorder causing severe bleeding in many body organs

- Jaundice, or yellowing of the eyes and skin

- Low blood sugar

- Pleural effusion

- Pulmonary embolism, or blood clots in the arteries of the lungs

- Severe ascites

If a mesothelioma forms metastases, these most commonly involve the liver, adrenal gland, kidney, or other lung.

Causes

Working with asbestos is the most common risk factor for mesothelioma. However, mesothelioma has been reported in some individuals without any known exposure to asbestos. Tentative evidence also raises concern about carbon nanotubes.

Asbestos

The incidence of mesothelioma has been found to be higher in populations living near naturally occurring asbestos. People can be exposed to naturally occurring asbestos in areas where mining or road construction is occurring, or when the asbestos-containing rock is naturally weathered. Another common route of exposure is through asbestos-containing soil, which is used to whitewash, plaster, and roof houses in Greece. In central Cappadocia, Turkey, mesothelioma was causing 50% of all deaths in three small villages—Tuzköy, Karain, and Sarıhıdır. Initially, this was attributed to erionite. Environmental exposure to asbestos has caused mesothelioma in places other than Turkey, including Corsica, Greece, Cyprus, China, and California. In the northern Greek mountain town of Metsovo, this exposure had resulted in mesothelioma incidence around 300 times more than expected in asbestos-free populations, and was associated with very frequent pleural calcification known as Metsovo lung.

The documented presence of asbestos fibers in water supplies and food products has fostered concerns about the possible impact of long-term and, as yet, unknown exposure of the general population to these fibers.

Exposure to talc is also a risk factor for mesothelioma; exposure can affect those who live near talc mines, work in talc mines, or work in talc mills.

In the United States, asbestos is considered the major cause of malignant mesothelioma and has been considered "indisputably" associated with the development of mesothelioma. Indeed, the relationship between asbestos and mesothelioma is so strong that many consider mesothelioma a "signal" or "sentinel" tumor. A history of asbestos exposure exists in most cases.

Pericardial mesothelioma may not be associated with asbestos exposure.

Asbestos was known in antiquity, but it was not mined and widely used commercially until the late 19th century. Its use greatly increased during World War II. Since the early 1940s, millions of American workers have been exposed to asbestos dust. Initially, the risks associated with asbestos exposure were not publicly known. However, an increased risk of developing mesothelioma was later found among naval personnel (e.g., Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard), shipyard workers, people who work in asbestos mines and mills, producers of asbestos products, workers in the heating and construction industries, and other tradespeople. Today, the official position of the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is that protections and "permissible exposure limits" required by U.S. regulations, while adequate to prevent most asbestos-related non-malignant disease, are not adequate to prevent or protect against asbestos-related cancers such as mesothelioma. Likewise, the British Government's Health and Safety Executive (HSE) states formally that any threshold for exposure to asbestos must be at a very low level and it is widely agreed that if any such threshold does exist at all, then it cannot currently be quantified. For practical purposes, therefore, HSE assumes that no such "safe" threshold exists. Others have noted as well that there is no evidence of a threshold level below which there is no risk of mesothelioma. There appears to be a linear, dose–response relationship, with increasing dose producing increasing risk of disease. Nevertheless, mesothelioma may be related to brief, low level, or indirect exposures to asbestos. The dose necessary for effect appears to be lower for asbestos-induced mesothelioma than for pulmonary asbestosis or lung cancer. Again, there is no known safe level of exposure to asbestos as it relates to increased risk of mesothelioma.

The time from first exposure to onset of the disease, is between 25 and 70 years. It is virtually never less than fifteen years and peaks at 30–40 years. The duration of exposure to asbestos causing mesothelioma can be short. For example, cases of mesothelioma have been documented with only 1–3 months of exposure.

Occupational

Exposure to asbestos fibers has been recognized as an occupational health hazard since the early 20th century. Numerous epidemiological studies have associated occupational exposure to asbestos with the development of pleural plaques, diffuse pleural thickening, asbestosis, carcinoma of the lung and larynx, gastrointestinal tumors, and diffuse malignant mesothelioma of the pleura and peritoneum. Asbestos has been widely used in many industrial products, including cement, brake linings, gaskets, roof shingles, flooring products, textiles, and insulation.

Commercial asbestos mining at Wittenoom, Western Australia, took place from 1937 to 1966. The first case of mesothelioma in the town occurred in 1960. The second case was in 1969, and new cases began to appear more frequently thereafter. The lag time between initial exposure to asbestos and the development of mesothelioma varied from 12 years 9 months up to 58 years. A cohort study of miners employed at the mine reported that 85 deaths attributable to mesothelioma had occurred by 1985. By 1994, 539 reported deaths due to mesothelioma had been reported in Western Australia.

Occupational exposure to asbestos in the United States mainly occurs when people are maintaining buildings that already have asbestos. Approximately 1.3 million US workers are exposed to asbestos annually; in 2002, an estimated 44,000 miners were potentially exposed to asbestos.

Paraoccupational secondary exposure

Family members and others living with asbestos workers have an increased risk of developing mesothelioma, and possibly other asbestos-related diseases. This risk may be the result of exposure to asbestos dust brought home on the clothing and hair of asbestos workers via washing a worker's clothes or coming into contact with asbestos-contaminated work clothing. To reduce the chance of exposing family members to asbestos fibres, asbestos workers are usually required to shower and change their clothing before leaving the workplace.

Asbestos in buildings

Many building materials used in both public and domestic premises prior to the banning of asbestos may contain asbestos. Those performing renovation works or DIY activities may expose themselves to asbestos dust. In the UK, use of chrysotile asbestos was banned at the end of 1999. Brown and blue asbestos were banned in the UK around 1985. Buildings built or renovated prior to these dates may contain asbestos materials.

Therefore, it is a legal requirement that all who may come across asbestos in their day-to-day work have been provided with the relevant asbestos training.

Genetic disposition

In a recent research carried on white American population in 2012, it was found that people with a germline mutation in their BAP1 gene are at higher risk of developing mesothelioma and uveal melanoma.

Erionite

Erionite is a zeolite mineral with similar properties to asbestos and is known to cause mesothelioma. Detailed epidemiological investigation has shown that erionite causes mesothelioma mostly in families with a genetic predisposition. Erionite is found in deposits in the Western United States, where it is used in gravel for road surfacing, and in Turkey, where it is used to construct homes. In Turkey, the United States, and Mexico, erionite has been associated with mesothelioma and has thus been designated a "known human carcinogen" by the US National Toxicology Program.

Other

In rare cases, mesothelioma has also been associated with irradiation of the chest or abdomen, intrapleural thorium dioxide (thorotrast) as a contrast medium, and inhalation of other fibrous silicates, such as erionite or talc. Some studies suggest that simian virus 40 (SV40) may act as a cofactor in the development of mesothelioma. This has been confirmed in animal studies, but studies in humans are inconclusive.

Pathophysiology

Systemic

The mesothelium consists of a single layer of flattened to cuboidal cells forming the epithelial lining of the serous cavities of the body including the peritoneal, pericardial, and pleural cavities. Deposition of asbestos fibers in the parenchyma of the lung may result in the penetration of the visceral pleura from where the fiber can then be carried to the pleural surface, thus leading to the development of malignant mesothelial plaques. The processes leading to the development of peritoneal mesothelioma remain unresolved, although it has been proposed that asbestos fibers from the lung are transported to the abdomen and associated organs via the lymphatic system. Additionally, asbestos fibers may be deposited in the gut after ingestion of sputum contaminated with asbestos fibers.

Pleural contamination with asbestos or other mineral fibers has been shown to cause cancer. Long thin asbestos fibers (blue asbestos, amphibole fibers) are more potent carcinogens than "feathery fibers" (chrysotile or white asbestos fibers). However, there is now evidence that smaller particles may be more dangerous than the larger fibers. They remain suspended in the air where they can be inhaled, and may penetrate more easily and deeper into the lungs. "We probably will find out a lot more about the health aspects of asbestos from , unfortunately," said Dr. Alan Fein, chief of pulmonary and critical-care medicine at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System.

Mesothelioma development in rats has been demonstrated following intra-pleural inoculation of phosphorylated chrysotile fibers. It has been suggested that in humans, transport of fibers to the pleura is critical to the pathogenesis of mesothelioma. This is supported by the observed recruitment of significant numbers of macrophages and other cells of the immune system to localized lesions of accumulated asbestos fibers in the pleural and peritoneal cavities of rats. These lesions continued to attract and accumulate macrophages as the disease progressed, and cellular changes within the lesion culminated in a morphologically malignant tumor.

Experimental evidence suggests that asbestos acts as a complete carcinogen with the development of mesothelioma occurring in sequential stages of initiation and promotion. The molecular mechanisms underlying the malignant transformation of normal mesothelial cells by asbestos fibers remain unclear despite the demonstration of its oncogenic capabilities (see next-but-one paragraph). However, complete in vitro transformation of normal human mesothelial cells to a malignant phenotype following exposure to asbestos fibers has not yet been achieved. In general, asbestos fibers are thought to act through direct physical interactions with the cells of the mesothelium in conjunction with indirect effects following interaction with inflammatory cells such as macrophages.

Intracellular

Analysis of the interactions between asbestos fibers and DNA has shown that phagocytosed fibers make contact with chromosomes, often adhering to the chromatin fibers or becoming entangled within the chromosome. This contact between the asbestos fiber and the chromosomes or structural proteins of the spindle apparatus can induce complex abnormalities. The most common abnormality is monosomy of chromosome 22. Other frequent abnormalities include structural rearrangement of 1p, 3p, 9p, and 6q chromosome arms.

Common gene abnormalities in mesothelioma cell lines include deletion of the tumor suppressor genes:

- Neurofibromatosis type 2 at 22q12

- P16

- P14

Asbestos has also been shown to mediate the entry of foreign DNA into target cells. Incorporation of this foreign DNA may lead to mutations and oncogenesis by several possible mechanisms:

- Inactivation of tumor suppressor genes

- Activation of oncogenes In tumor cells, these genes are often mutated, or expressed at high levels.

- Activation of proto-oncogenes due to incorporation of foreign DNA containing a promoter region

- Activation of DNA repair enzymes, which may be prone to error

- Activation of telomerase

- Prevention of apoptosis

Several genes are commonly mutated in mesothelioma, and may be prognostic factors. These include primarily BAP1, NF2, and TP53; epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and C-Met, receptor tyrosine kinases can also be altered and overexpressed in many mesotheliomas. Some association has been found with EGFR and epithelioid histology but no clear association has been found between EGFR overexpression and overall survival; BAP1 alterations are also predominantly in the epithelioid histology. Aneuploidy, ranging from haploidy to tetraploidy, and CpG island hypermethylation have also been shown to be frequent and associated with survival. Expression of AXL receptor tyrosine kinase is a negative prognostic factor. Expression of PDGFRB is a positive prognostic factor. In general, mesothelioma is characterized by loss of function in tumor suppressor genes, rather than by an overexpression or gain of function in oncogenes.

As an environmentally triggered malignancy, mesothelioma tumors have been found to be polyclonal in origin, by performing an X-inactivation based assay on epitheloid and biphasic tumors obtained from female patients. These results suggest that an environmental factor, most likely asbestos exposure, may damage and transform a group of cells in the tissue, resulting in a population of tumor cells that are, albeit only slightly, genetically different.

Immune system

Asbestos fibers have been shown to alter the function and secretory properties of macrophages, ultimately creating conditions which favour the development of mesothelioma. Following asbestos phagocytosis, macrophages generate increased amounts of hydroxyl radicals, which are normal by-products of cellular anaerobic metabolism. However, these free radicals are also known clastogenic (chromosome-breaking) and membrane-active agents thought to promote asbestos carcinogenicity. These oxidants can participate in the oncogenic process by directly and indirectly interacting with DNA, modifying membrane-associated cellular events, including oncogene activation and perturbation of cellular antioxidant defences.

Asbestos also may possess immunosuppressive properties. For example, chrysotile fibres have been shown to depress the in vitro proliferation of phytohemagglutinin-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes, suppress natural killer cell lysis, and significantly reduce lymphokine-activated killer cell viability and recovery. Furthermore, genetic alterations in asbestos-activated macrophages may result in the release of potent mesothelial cell mitogens such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) which in turn, may induce the chronic stimulation and proliferation of mesothelial cells after injury by asbestos fibres.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of mesothelioma can be suspected with imaging but is confirmed with biopsy. It must be clinically and histologically differentiated from other pleural and pulmonary malignancies, including reactive pleural disease, primary lung carcinoma, pleural metastases of other cancers, and other primary pleural cancers.

Primary pericardial mesothelioma is often diagnosed after it has metastasized to lymph nodes or the lungs.

Imaging

Diagnosing mesothelioma is often difficult because the symptoms are similar to those of a number of other conditions. Diagnosis begins with a review of the patient's medical history. A history of exposure to asbestos may increase clinical suspicion for mesothelioma. A physical examination is performed, followed by chest X-ray and often lung function tests. The X-ray may reveal pleural thickening commonly seen after asbestos exposure and increases suspicion of mesothelioma. A CT (or CAT) scan or an MRI is usually performed. If a large amount of fluid is present, abnormal cells may be detected by cytopathology if this fluid is aspirated with a syringe. For pleural fluid, this is done by thoracentesis or tube thoracostomy (chest tube); for ascites, with paracentesis or ascitic drain; and for pericardial effusion with pericardiocentesis. While absence of malignant cells on cytology does not completely exclude mesothelioma, it makes it much more unlikely, especially if an alternative diagnosis can be made (e.g., tuberculosis, heart failure). However, with primary pericardial mesothelioma, pericardial fluid may not contain malignant cells and a tissue biopsy is more useful in diagnosis. Using conventional cytology diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma is difficult, but immunohistochemistry has greatly enhanced the accuracy of cytology.

Biopsy

Generally, a biopsy is needed to confirm a diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. A doctor removes a sample of tissue for examination under a microscope by a pathologist. A biopsy may be done in different ways, depending on where the abnormal area is located. If the cancer is in the chest, the doctor may perform a thoracoscopy. In this procedure, the doctor makes a small cut through the chest wall and puts a thin, lighted tube called a thoracoscope into the chest between two ribs. Thoracoscopy allows the doctor to look inside the chest and obtain tissue samples. Alternatively, the cardiothoracic surgeon might directly open the chest (thoracotomy). If the cancer is in the abdomen, the doctor may perform a laparoscopy. To obtain tissue for examination, the doctor makes a small incision in the abdomen and inserts a special instrument into the abdominal cavity. If these procedures do not yield enough tissue, an open surgical procedure may be necessary.

Immunochemistry

Immunohistochemical studies play an important role for the pathologist in differentiating malignant mesothelioma from neoplastic mimics, such as breast or lung cancer that has metastasized to the pleura. There are numerous tests and panels available, but no single test is perfect for distinguishing mesothelioma from carcinoma or even benign versus malignant. The positive markers indicate that mesothelioma is present; if other markers are positive it may indicate another type of cancer, such as breast or lung adenocarcinoma. Calretinin is a particularly important marker in distinguishing mesothelioma from metastatic breast or lung cancer.

| Positive | Negative |

|---|---|

| EMA (epithelial membrane antigen) in a membranous distribution | CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) |

| WT1 (Wilms' tumour 1) | MAb B72.3 |

| Calretinin | MOC-3 1 |

| Mesothelin | CD15 |

| Cytokeratin 5 | Ber-EP4 |

| HBME-1 (human mesothelial cell 1) | TTF-1 (thyroid transcription factor-1) |

| Podoplanin (PDPN) | Claudin-4 |

| Osteopontin | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) |

| Estrogen receptor alpha | |

| Mammaglobin |

Subtypes

There are three main histological subtypes of malignant mesothelioma: epithelioid, sarcomatous, and biphasic. Epithelioid and biphasic mesothelioma make up approximately 75-95% of mesotheliomas and have been well characterized histologically, whereas sarcomatous mesothelioma has not been studied extensively. Most mesotheliomas express high levels of cytokeratin 5 regardless of subtype.

Epithelioid mesothelioma is characterized by high levels of calretinin.

Sarcomatous mesothelioma does not express high levels of calretinin.

Other morphological subtypes have been described:

- Desmoplastic

- Clear cell

- Deciduoid

- Adenomatoid

- Glandular

- Mucohyaline

- Cartilaginous and osseous metaplasia

- Lymphohistiocytic

Differential diagnosis

- Metastatic adenocarcinoma

- Pleural sarcoma

- Synovial sarcoma

- Thymoma

- Metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- Metastatic osteosarcoma

Staging

Staging of mesothelioma is based on the recommendation by the International Mesothelioma Interest Group. TNM classification of the primary tumor, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis is performed. Mesothelioma is staged Ia–IV (one-A to four) based on the TNM status.

Prevention

Mesothelioma can be prevented in most cases by preventing exposure to asbestos. The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health maintains a recommended exposure limit of 0.1 asbestos fiber per cubic centimeter.

Screening

There is no universally agreed protocol for screening people who have been exposed to asbestos. Screening tests might diagnose mesothelioma earlier than conventional methods thus improving the survival prospects for patients. The serum osteopontin level might be useful in screening asbestos-exposed people for mesothelioma. The level of soluble mesothelin-related protein is elevated in the serum of about 75% of patients at diagnosis and it has been suggested that it may be useful for screening. Doctors have begun testing the Mesomark assay, which measures levels of soluble mesothelin-related proteins (SMRPs) released by mesothelioma cells.

Treatment

Mesothelioma is generally resistant to radiation and chemotherapy treatment. Long-term survival and cures are exceedingly rare. Treatment of malignant mesothelioma at earlier stages has a better prognosis. Clinical behavior of the malignancy is affected by several factors including the continuous mesothelial surface of the pleural cavity which favors local metastasis via exfoliated cells, invasion to underlying tissue and other organs within the pleural cavity, and the extremely long latency period between asbestos exposure and development of the disease. The histological subtype and the patient's age and health status also help predict prognosis. The epithelioid histology responds better to treatment and has a survival advantage over sarcomatoid histology.

The effectiveness of radiotherapy compared to chemotherapy or surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma is not known.

Surgery

Surgery, by itself, has proved disappointing. In one large series, the median survival with surgery (including extrapleural pneumonectomy) was only 11.7 months. However, research indicates varied success when used in combination with radiation, chemotherapy (Duke, 2008), or both. A pleurectomy/decortication is the most common surgery, in which the lining of the chest is removed. Less common is an extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP), in which the lung, lining of the inside of the chest, the hemi-diaphragm, and the pericardium are removed. In localized pericardial mesothelioma, pericardectomy can be curative; when the tumor has metastasized, pericardectomy is a palliative care option. It is often not possible to remove the entire tumor.

Radiation

For patients with localized disease, and who can tolerate a radical surgery, radiation can be given post-operatively as a consolidative treatment. The entire hemithorax is treated with radiation therapy, often given simultaneously with chemotherapy. Delivering radiation and chemotherapy after a radical surgery has led to extended life expectancy in selected patient populations. It can also induce severe side-effects, including fatal pneumonitis. As part of a curative approach to mesothelioma, radiotherapy is commonly applied to the sites of chest drain insertion, in order to prevent growth of the tumor along the track in the chest wall.

Although mesothelioma is generally resistant to curative treatment with radiotherapy alone, palliative treatment regimens are sometimes used to relieve symptoms arising from tumor growth, such as obstruction of a major blood vessel. Radiation therapy, when given alone with curative intent, has never been shown to improve survival from mesothelioma. The necessary radiation dose to treat mesothelioma that has not been surgically removed would be beyond human tolerance. Radiotherapy is of some use in pericardial mesothelioma.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the only treatment for mesothelioma that has been proven to improve survival in randomised and controlled trials. The landmark study published in 2003 by Vogelzang and colleagues compared cisplatin chemotherapy alone with a combination of cisplatin and pemetrexed (brand name Alimta) chemotherapy in patients who had not received chemotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma previously and were not candidates for more aggressive "curative" surgery. This trial was the first to report a survival advantage from chemotherapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma, showing a statistically significant improvement in median survival from 10 months in the patients treated with cisplatin alone to 13.3 months in the group of patients treated with cisplatin in the combination with pemetrexed and who also received supplementation with folate and vitamin B12. Vitamin supplementation was given to most patients in the trial and pemetrexed related side effects were significantly less in patients receiving pemetrexed when they also received daily oral folate 500mcg and intramuscular vitamin B12 1000mcg every 9 weeks compared with patients receiving pemetrexed without vitamin supplementation. The objective response rate increased from 20% in the cisplatin group to 46% in the combination pemetrexed group. Some side effects such as nausea and vomiting, stomatitis, and diarrhoea were more common in the combination pemetrexed group but only affected a minority of patients and overall the combination of pemetrexed and cisplatin was well tolerated when patients received vitamin supplementation; both quality of life and lung function tests improved in the combination pemetrexed group. In February 2004, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pemetrexed for treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. However, there are still unanswered questions about the optimal use of chemotherapy, including when to start treatment, and the optimal number of cycles to give. Cisplatin and pemetrexed together give patients a median survival of 12.1 months.

Cisplatin in combination with raltitrexed has shown an improvement in survival similar to that reported for pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin, but raltitrexed is no longer commercially available for this indication. For patients unable to tolerate pemetrexed, cisplatin in combination with gemcitabine or vinorelbine is an alternative, or vinorelbine on its own, although a survival benefit has not been shown for these drugs. For patients in whom cisplatin cannot be used, carboplatin can be substituted but non-randomised data have shown lower response rates and high rates of haematological toxicity for carboplatin-based combinations, albeit with similar survival figures to patients receiving cisplatin. Cisplatin in combination with premetrexed disodium, folic acid, and vitamin B12 may also improve survival for people who are responding to chemotherapy.

In January 2009, the United States FDA approved using conventional therapies such as surgery in combination with radiation and/or chemotherapy on stage I or II Mesothelioma after research conducted by a nationwide study by Duke University concluded an almost 50 point increase in remission rates.

In pericardial mesothelioma, chemotherapy—typically adriamycin or cisplatin—is primarily used to shrink the tumor and is not curative.

Immunotherapy

Treatment regimens involving immunotherapy have yielded variable results. For example, intrapleural inoculation of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) in an attempt to boost the immune response, was found to be of no benefit to the patient (while it may benefit patients with bladder cancer). Mesothelioma cells proved susceptible to in vitro lysis by LAK cells following activation by interleukin-2 (IL-2), but patients undergoing this particular therapy experienced major side effects. Indeed, this trial was suspended in view of the unacceptably high levels of IL-2 toxicity and the severity of side effects such as fever and cachexia. Nonetheless, other trials involving interferon alpha have proved more encouraging with 20% of patients experiencing a greater than 50% reduction in tumor mass combined with minimal side effects.

In October 2020, the FDA approved the combination of nivolumab (Opdivo) with ipilimumab (Yervoy) for the first-line treatment of adults with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) that cannot be removed by surgery. Nivolumab and ipilimumab are both monoclonal antibodies that, when combined, decrease tumor growth by enhancing T-cell function. The combination therapy was evaluated through a randomized, open-label trial in which participants who received nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab survived a median of 18.1 months while participants who underwent chemotherapy survived a median of 14.1 months.

Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy

Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy is used in conjunction with surgery, including in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. The surgeon removes as much of the tumor as possible followed by the direct administration of a chemotherapy agent, heated to between 40 and 48 °C, in the abdomen. The fluid is perfused for 60 to 120 minutes and then drained. High concentrations of selected drugs are then administered into the pleural cavity. Heating the chemotherapy treatment increases the penetration of the drugs into tissues. Also, heating itself damages the malignant cells more than the normal cells.

Multimodality therapy

Multimodal therapy, which includes a combined approach of surgery, radiation, or photodynamic therapy, and chemotherapy, is not suggested for routine practice for treating malignant pleural mesothelioma. The effectiveness and safety of multimodal therapy is not clear (not enough research has been performed) and one clinical trial has suggested a possible increased risk of adverse effects.

Large series of examining multimodality treatment have only demonstrated modest improvement in survival (median survival 14.5 months and only 29.6% surviving 2 years). Reducing the bulk of the tumor with cytoreductive surgery is key to extending survival. Two surgeries have been developed: extrapleural pneumonectomy and pleurectomy/decortication. The indications for performing these operations are unique. The choice of operation namely depends on the size of the patient's tumor. This is an important consideration because tumor volume has been identified as a prognostic factor in mesothelioma. Pleurectomy/decortication spares the underlying lung and is performed in patients with early stage disease when the intention is to remove all gross visible tumor (macroscopic complete resection), not simply palliation. Extrapleural pneumonectomy is a more extensive operation that involves resection of the parietal and visceral pleurae, underlying lung, ipsilateral (same side) diaphragm, and ipsilateral pericardium. This operation is indicated for a subset of patients with more advanced tumors, who can tolerate a pneumonectomy.

Prognosis

Mesothelioma usually has a poor prognosis. Typical survival despite surgery is between 12 and 21 months depending on the stage of disease at diagnosis with about 7.5% of people surviving for 5 years.

Women, young people, people with low-stage cancers, and people with epithelioid cancers have better prognoses. Negative prognostic factors include sarcomatoid or biphasic histology, high platelet counts (above 400,000), age over 50 years, white blood cell counts above 15.5, low glucose levels in the pleural fluid, low albumin levels, and high fibrinogen levels. Several markers are under investigation as prognostic factors, including nuclear grade, and serum c-reactive protein. Long-term survival is rare.

Pericardial mesothelioma has a 10-month median survival time.

In peritoneal mesothelioma, high expression of WT-1 protein indicates a worse prognosis.

Epidemiology

Although reported incidence rates have increased in the past 20 years, mesothelioma is still a relatively rare cancer. The incidence rate varies from one country to another, from a low rate of less than 1 per 1,000,000 in Tunisia and Morocco, to the highest rate in Britain, Australia, and Belgium: 30 per 1,000,000 per year. For comparison, populations with high levels of smoking can have a lung cancer incidence of over 1,000 per 1,000,000. Incidence of malignant mesothelioma currently ranges from about 7 to 40 per 1,000,000 in industrialized Western nations, depending on the amount of asbestos exposure of the populations during the past several decades. Worldwide incidence is estimated at 1–6 per 1,000,000.

Incidence of mesothelioma lags behind that of asbestosis due to the longer time it takes to develop; due to the cessation of asbestos use in developed countries, mesothelioma incidence is expected to decrease. Incidence is expected to continue increasing in developing countries due to continuing use of asbestos. Mesothelioma occurs more often in men than in women and risk increases with age, but this disease can appear in either men or women at any age. Approximately one fifth to one third of all mesotheliomas are peritoneal. Less than 5% of mesotheliomas are pericardial. The prevalence of pericardial mesothelioma is less than 0.002%; it is more common in men than women. It typically occurs in a person's 50s-70s.

Between 1940 and 1979, approximately 27.5 million people were occupationally exposed to asbestos in the United States. Between 1973 and 1984, the incidence of pleural mesothelioma among Caucasian males increased 300%. From 1980 to the late 1990s, the death rate from mesothelioma in the USA increased from 2,000 per year to 3,000, with men four times more likely to acquire it than women. More than 80% of mesotheliomas are caused by asbestos exposure.

The incidence of peritoneal mesothelioma is 0.5–3.0 per million per year in men, and 0.2–2.0 per million per year in women.

UK

Mesothelioma accounts for less than 1% of all cancers diagnosed in the UK, (around 2,600 people were diagnosed with the disease in 2011), and it is the seventeenth most common cause of cancer death (around 2,400 people died in 2012).

History

Connections between asbestos exposure and mesothelioma were first identified in the 1960s, with significant evidence emerging from South Africa. In the United States, asbestos manufacture stopped in 2002. Asbestos exposure thus shifted from workers in asbestos textile mills, friction product manufacturing, cement pipe fabrication, and insulation manufacture and installation to maintenance workers in asbestos-containing buildings.

Society and culture

Notable cases

Mesothelioma, though rare, has had a number of notable patients:

- Malcolm McLaren, musician and manager of the punk rock band the Sex Pistols, was diagnosed with peritoneal mesothelioma in October 2009 and died on 8 April 2010 in Switzerland.

- Steve McQueen, American actor, was diagnosed with peritoneal mesothelioma on December 22, 1979. He was not offered surgery or chemotherapy because doctors felt the cancer was too advanced. McQueen subsequently sought alternative treatments at clinics in Mexico. He died of a heart attack on November 7, 1980, in Juárez, Mexico, following cancer surgery. He may have been exposed to asbestos while serving with the U.S. Marines as a young adult—asbestos was then commonly used to insulate ships' piping—or from its use as an insulating material in automobile racing suits (McQueen was an avid racing driver and fan).

- Mickie Most, record producer, died of peritoneal mesothelioma in May 2003; however, it has been questioned whether this was due to asbestos exposure.

- Warren Zevon, American musician, was diagnosed with pleural mesothelioma in 2002, and died on September 7, 2003. It is believed that this was caused through childhood exposure to asbestos insulation in the attic of his father's shop.

- David Martin, Australian sailor and politician, died on 10 August 1990 of pleural mesothelioma. It is believed that this was caused by his exposure to asbestos on military ships during his career in the Royal Australian Navy.

- Paul Kraus, diagnosed in 1997, is considered the longest currently living (as of 2017) mesothelioma survivor in the world.

- F. W. De Klerk, South African retired politician, was diagnosed with mesothelioma on March 19, 2021, and died in November 2021.

- Paul Gleason, American actor, died on May 27, 2006, just a few months after diagnosis.

- Merlin Olsen, American football player, announcer, and actor, died March 11, 2010.

Although life expectancy with this disease is typically limited, there are notable survivors. In July 1982, Stephen Jay Gould, a well-regarded paleontologist, was diagnosed with peritoneal mesothelioma. After his diagnosis, Gould wrote "The Median Isn't the Message", in which he argued that statistics such as median survival are useful abstractions, not destiny. Gould lived for another 20 years, eventually succumbing to cancer not linked to his mesothelioma.

Legal issues

Main article: Asbestos and the lawSome people who were exposed to asbestos have collected damages for an asbestos-related disease, including mesothelioma. Compensation via asbestos funds or class action lawsuits is an important issue in law practices regarding mesothelioma.

The first lawsuits against asbestos manufacturers were in 1929. Since then, many lawsuits have been filed against asbestos manufacturers and employers, for neglecting to implement safety measures after the links between asbestos, asbestosis, and mesothelioma became known (some reports seem to place this as early as 1898). The liability resulting from the sheer number of lawsuits and people affected has reached billions of dollars. The amounts and method of allocating compensation have been the source of many court cases, reaching up to the United States Supreme Court, and government attempts at resolution of existing and future cases. However, to date, the US Congress has not stepped in and there are no federal laws governing asbestos compensation. In 2013, the "Furthering Asbestos Claim Transparency (FACT) Act of 2013" passed the US House of representatives and was sent to the US Senate, where it was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee. As the Senate did not vote on it before the end of the 113th Congress, it died in committee. It was revived in the 114th Congress, where it has not yet been brought before the House for a vote.

History

The first lawsuit against asbestos manufacturers was brought in 1929. The parties settled that lawsuit, and as part of the agreement, the attorneys agreed not to pursue further cases. In 1960, an article published by Wagner et al. was seminal in establishing mesothelioma as a disease arising from exposure to asbestos. The article referred to over 30 case studies of people who had had mesothelioma in South Africa. Some exposures were transient and some were mine workers. Before the use of advanced microscopy techniques, malignant mesothelioma was often diagnosed as a variant form of lung cancer. In 1962, McNulty reported the first diagnosed case of malignant mesothelioma in an Australian asbestos worker. The worker had worked in the mill at the asbestos mine in Wittenoom from 1948 to 1950.

In the town of Wittenoom, asbestos-containing mine waste was used to cover schoolyards and playgrounds. In 1965, an article in the British Journal of Industrial Medicine established that people who lived in the neighbourhoods of asbestos factories and mines, but did not work in them, had contracted mesothelioma.

Despite proof that the dust associated with asbestos mining and milling causes asbestos-related disease, mining began at Wittenoom in 1943 and continued until 1966. In 1974, the first public warnings of the dangers of blue asbestos were published in a cover story called "Is this Killer in Your Home?" in Australia's Bulletin magazine. In 1978, the Western Australian Government decided to phase out the town of Wittenoom, following the publication of a Health Dept. booklet, "The Health Hazard at Wittenoom", containing the results of air sampling and an appraisal of worldwide medical information.

By 1979, the first writs for negligence related to Wittenoom were issued against CSR and its subsidiary ABA, and the Asbestos Diseases Society was formed to represent the Wittenoom victims.

In Leeds, England the Armley asbestos disaster involved several court cases against Turner & Newall where local residents who contracted mesothelioma demanded compensation because of the asbestos pollution from the company's factory. One notable case was that of June Hancock, who contracted the disease in 1993 and died in 1997.

Research

See also: Mesothelioma Applied Research FoundationThe WT-1 protein is overexpressed in mesothelioma and is being researched as a potential target for drugs.

There are two high-confidence miRNAs that can potentially serve as biomarkers of asbestos exposure and malignant mesothelioma. Validation studies are needed to assess their relevance.

Some growth factors have been identified and as a result, targeted therapies have emerged to help slow the growth of oncogenic abnormalities. For example, bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody, is directed at the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR).

References

- ^ "Malignant Mesothelioma Treatment – Patient Version (PDQ®)". NCI. September 4, 2015. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Kondola S, Manners D, Nowak AK (June 2016). "Malignant pleural mesothelioma: an update on diagnosis and treatment options". Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease. 10 (3): 275–288. doi:10.1177/1753465816628800. PMC 5933604. PMID 26873306.

- ^ Robinson BM (November 2012). "Malignant pleural mesothelioma: an epidemiological perspective". Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 1 (4): 491–496. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.11.04. PMC 3741803. PMID 23977542.

- Vilchez RA, Butel JS (July 2004). "Emergent human pathogen simian virus 40 and its role in cancer". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 17 (3): 495–508. doi:10.1128/CMR.17.3.495-508.2004. PMC 452549. PMID 15258090.

- ^ Whittemore AS (2006). Cancer epidemiology and prevention (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 669. ISBN 978-0-19-974797-9.

- ^ "Malignant Mesothelioma Treatment – Patient Version (PDQ®)". NCI. September 4, 2015. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ "Age-Adjusted SEER Incidence and U.S. Death Rates and 5-Year Relative Survival (Percent) By Primary Cancer Site, Sex and Time Period" (PDF). NCI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- "Malignant Mesothelioma – Patient Version". NCI. January 1980. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Sardar MR, Kuntz C, Patel T, Saeed W, Gnall E, Imaizumi S, et al. (2012). "Primary pericardial mesothelioma unique case and literature review". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 39 (2): 261–264. PMC 3384041. PMID 22740748.

- ^ Panou V, Vyberg M, Weinreich UM, Meristoudis C, Falkmer UG, Røe OD (June 2015). "The established and future biomarkers of malignant pleural mesothelioma". Cancer Treatment Reviews. 41 (6): 486–495. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.05.001. PMID 25979846.

- ^ Gulati M, Redlich CA (March 2015). "Asbestosis and environmental causes of usual interstitial pneumonia". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 21 (2): 193–200. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000144. PMC 4472384. PMID 25621562.

- "What are the key statistics about malignant mesothelioma?". American Cancer Society. 2016-02-17. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Barreiro TJ, Katzman PJ (December 2006). "Malignant mesothelioma: a case presentation and review". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 106 (12): 699–704. PMID 17242414.

- Raza A, Huang WC, Takabe K (September 2014). "Advances in the management of peritoneal mesothelioma". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (33): 11700–11712. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11700. PMC 4155360. PMID 25206274.

- Cedrés S, Fariñas L, Stejpanovic N, Martinez P, Martinez A, Zamora E, et al. (April 2013). "Bone metastases with nerve root compression as a late complication in patient with epithelial pleural mesothelioma". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 5 (2): E35 – E37. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.07.08. PMC 3621936. PMID 23585954.

- "EBSCO database". Archived from the original on 2012-05-12. verified by URAC; accessed from Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- "Study says Carbon Nanotubes as Dangerous as Asbestos". Scientific American.

- Attanoos RL, Churg A, Galateau-Salle F, Gibbs AR, Roggli VL (June 2018). "Malignant Mesothelioma and Its Non-Asbestos Causes". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 142 (6): 753–760. doi:10.5858/arpa.2017-0365-RA. PMID 29480760.

- ^ Constantopoulos SH (October 2008). "Environmental mesothelioma associated with tremolite asbestos: lessons from the experiences of Turkey, Greece, Corsica, New Caledonia and Cyprus". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 52 (1 Suppl): S110 – S115. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.11.001. PMID 18171598.

- ^ Weissman D, Kiefer M (22 November 2011). "Erionite: An Emerging North American Hazard". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015.

- Dogan U (2003). "Mesothelioma in Cappadocian villages". Indoor and Built Environment. 12 (6): 367–375. doi:10.1177/1420326X03039065. ISSN 1420-326X. S2CID 110334356.

- Carbone M, Emri S, Dogan AU, Steele I, Tuncer M, Pass HI, et al. (February 2007). "A mesothelioma epidemic in Cappadocia: scientific developments and unexpected social outcomes". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 7 (2): 147–154. doi:10.1038/nrc2068. PMID 17251920. S2CID 9440201.

- "Asbestos in Drinking-water: Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water quality" (PDF). 2003. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ "Asbestos fibers and other elongate mineral particles: state of the science and roadmap for research". Current Intelligence Bulletin 62. 10 July 2020. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2011159.

- Kanarek MS (September 2011). "Mesothelioma from chrysotile asbestos: update". Annals of Epidemiology. 21 (9): 688–697. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.05.010. PMID 21820631.

- ^ Roggli VL, Sharma A, Butnor KJ, Sporn T, Vollmer RT (2002). "Malignant mesothelioma and occupational exposure to asbestos: a clinicopathological correlation of 1445 cases". Ultrastructural Pathology. 26 (2): 55–65. doi:10.1080/01913120252959227. PMID 12036093. S2CID 25204873.

- Sporn TA, Roggli VL (2004). "Mesothelioma". In Roggli VL, Oury TD, Sporn TA (eds.). Pathology of Asbestos-associated Diseases (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 104.

- Gennaro V, Finkelstein MM, Ceppi M, Fontana V, Montanaro F, Perrotta A, et al. (March 2000). "Mesothelioma and lung tumors attributable to asbestos among petroleum workers". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 37 (3): 275–282. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(200003)37:3<275::AID-AJIM5>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID 10642417.

- Selikoff IJ (1986). "Occupational Respiratory Diseases". Public Health and Preventative Medicine (12th ed.). Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 532.

- Henderson DW, Rödelsperger K, Woitowitz HJ, Leigh J (December 2004). "After Helsinki: a multidisciplinary review of the relationship between asbestos exposure and lung cancer, with emphasis on studies published during 1997–2004". Pathology. 36 (6): 517–550. doi:10.1080/00313020400010955. PMID 15841689. S2CID 35280387.

- "NIOSH Working Group Paper" (PDF). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and prevention. 1980. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-18.

- Hillerdal G (August 1999). "Mesothelioma: cases associated with non-occupational and low dose exposures". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 56 (8): 505–513. doi:10.1136/oem.56.8.505. PMC 1757769. PMID 10492646.

- Peto J, Seidman H, Selikoff IJ (January 1982). "Mesothelioma mortality in asbestos workers: implications for models of carcinogenesis and risk assessment". British Journal of Cancer. 45 (1): 124–135. doi:10.1038/bjc.1982.15. PMC 2010947. PMID 7059455.

- Carbone M, Ly BH, Dodson RF, Pagano I, Morris PT, Dogan UA, et al. (January 2012). "Malignant mesothelioma: facts, myths, and hypotheses". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 227 (1): 44–58. doi:10.1002/jcp.22724. PMC 3143206. PMID 21412769.

- Lanphear BP, Buncher CR (July 1992). "Latent period for malignant mesothelioma of occupational origin". Journal of Occupational Medicine. 34 (7): 718–721. PMID 1494965.

- Burdorf A, Dahhan M, Swuste P (August 2003). "Occupational characteristics of cases with asbestos-related diseases in The Netherlands". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. 47 (6): 485–492. doi:10.1093/annhyg/meg062. hdl:1765/10196. PMID 12890657.

- Glover J (April 1973). "Hygiene standards for airborne amosite asbestos dust. British Occupational Hygiene Society Committee on Hygiene Standards". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. 16 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1093/annhyg/16.1.1. PMID 4775386.

- "Learn About Asbestos". US Environmental Protection Agency. 2013-03-05. Archived from the original on 2016-06-23. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- Berry G, Reid A, Aboagye-Sarfo P, de Klerk NH, Olsen NJ, Merler E, et al. (February 2012). "Malignant mesotheliomas in former miners and millers of crocidolite at Wittenoom (Western Australia) after more than 50 years follow-up". British Journal of Cancer. 106 (5): 1016–1020. doi:10.1038/bjc.2012.23. PMC 3305966. PMID 22315054.

- "Protecting Workers' Families: A Research Agenda of the Workers' Family Protection Task Force". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. DHHS (NIOSH). May 2002. Publication No. 2002-113. Archived from the original on 2017-06-19.

- Peipins LA, Lewin M, Campolucci S, Lybarger JA, Miller A, Middleton D, et al. (November 2003). "Radiographic abnormalities and exposure to asbestos-contaminated vermiculite in the community of Libby, Montana, USA". Environmental Health Perspectives. 111 (14): 1753–1759. Bibcode:2003EnvHP.111.1753P. doi:10.1289/ehp.6346. PMC 1241719. PMID 14594627.

- "Where can you find asbestos?". hse.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- Testa JR, Cheung M, Pei J, Below JE, Tan Y, Sementino E, et al. (August 2011). "Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma". Nature Genetics. 43 (10): 1022–1025. doi:10.1038/ng.912. PMC 3184199. PMID 21874000.

- ^ Broaddus VC, Robinson BW (2010). "Chapter 75". Murray & Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine (5th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-4710-0.

- Holland-Frei (2010). "Chapter 79". Cancer Medicine (8th ed.). People's Medical Publishing House USA. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1.

- Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. 2008. p. 1537. ISBN 978-0-07-145739-2.

- Maitra A, Kumar V (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. p. 536. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- Mutsaers SE (September 2002). "Mesothelial cells: their structure, function and role in serosal repair". Respirology. 7 (3): 171–191. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1843.2002.00404.x. PMID 12153683. S2CID 23976724.

- Miserocchi G, Sancini G, Mantegazza F, Chiappino G (January 2008). "Translocation pathways for inhaled asbestos fibers". Environmental Health. 7 (1): 4. Bibcode:2008EnvHe...7....4M. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-7-4. PMC 2265277. PMID 18218073.

- "The Junkman's Answer to Terrorism: Use More Asbestos" (PDF). Center for Media and Democracy: Prwatch.org. 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) (2001). Toxicological profile for Asbestos (PDF) (Report). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

- "Neurofibromatosis Fact Sheet". NINDS. 3 February 2016. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Chiosea S, Krasinskas A, Cagle PT, Mitchell KA, Zander DS, Dacic S (June 2008). "Diagnostic importance of 9p21 homozygous deletion in malignant mesotheliomas". Modern Pathology. 21 (6): 742–747. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2008.45. PMID 18327208. S2CID 7743919.

- Sherr CJ (September 2006). "Divorcing ARF and p53: an unsettled case". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 6 (9): 663–673. doi:10.1038/nrc1954. PMID 16915296. S2CID 29465278.

- Wilbur B, ed. (2009). The World of the Cell (7th ed.). San Francisco, C: Benjamin Cummings.

- "Oncogenes". Kimball's Biology Pages. Archived from the original on 2017-12-31.

- Dehé PM, Gaillard PH (May 2017). "Control of structure-specific endonucleases to maintain genome stability". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 18 (5): 315–330. doi:10.1038/nrm.2016.177. PMID 28327556. S2CID 24009279.

- Shay JW, Wright WE. "What are telomeres and telomerase?". The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008.

- Green D (2011). Means to an End: Apoptosis and other Cell Death Mechanisms. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-888-1.

- Bueno, Stawiski, Goldstein, Durinck, De Rienzo (2016). "Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations". Nature Genetics. 48 (4): 407–416. doi:10.1038/ng.3520. PMID 26928227. S2CID 13480173.

- Mangiante, Alcala, Sexton-Oates, Di Genova, Gonzalez-Perez (2023). "Multiomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies molecular axes and specialized tumor profiles driving intertumor heterogeneity". Nature Genetics. 55 (4): 607–618. doi:10.1038/s41588-023-01321-1. PMC 10101853. PMID 36928603. S2CID 257582839.

- ^ Davidson B (June 2015). "Prognostic factors in malignant pleural mesothelioma". Human Pathology. 46 (6): 789–804. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2015.02.006. PMID 25824607.

- Reid G (June 2015). "MicroRNAs in mesothelioma: from tumour suppressors and biomarkers to therapeutic targets". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (6): 1031–1040. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.56. PMC 4466421. PMID 26150916.

- Comertpay S, Pastorino S, Tanji M, Mezzapelle R, Strianese O, Napolitano A, et al. (December 2014). "Evaluation of clonal origin of malignant mesothelioma". Journal of Translational Medicine. 12: 301. doi:10.1186/s12967-014-0301-3. PMC 4255423. PMID 25471750.

- Weder W (October 2010). "Mesothelioma". Annals of Oncology. 21 (7): vii326 – vii333. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq471. PMID 20943637.

- ^ Ceresoli GL, Gridelli C, Santoro A (July 2007). "Multidisciplinary treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma". The Oncologist. 12 (7): 850–863. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-850. PMID 17673616. S2CID 41668550.

- Berzenji L, Van Schil PE, Carp L (October 2018). "The eighth TNM classification for malignant pleural mesothelioma". Translational Lung Cancer Research. 7 (5): 543–549. doi:10.21037/tlcr.2018.07.05. PMC 6204412. PMID 30450292.

- Robinson BW, Creaney J, Lake R, Nowak A, Musk AW, de Klerk N, et al. (July 2005). "Soluble mesothelin-related protein--a blood test for mesothelioma". Lung Cancer. 49 (Suppl 1): S109 – S111. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.03.020. PMID 15950789.

- Beyer HL, Geschwindt RD, Glover CL, Tran L, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE, et al. (April 2007). "MESOMARK: a potential test for malignant pleural mesothelioma". Clinical Chemistry. 53 (4): 666–672. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2006.079327. PMID 17289801.

- Milosevic V, Kopecka J, Salaroglio IC, Libener R, Napoli F, Izzo S, et al. (2020). "Wnt/IL-1β/IL-8 autocrine circuitries control chemoresistance in mesothelioma initiating cells by inducing ABCB5". International Journal of Cancer. 146 (1): 192–207. doi:10.1002/ijc.32419. hdl:2318/1711962. PMID 31107974. S2CID 160014053.

- Haber SE, Haber JM (2011). "Malignant mesothelioma: a clinical study of 238 cases". Industrial Health. 49 (2): 166–172. doi:10.2486/indhealth.MS1147. PMID 21173534.

- Chapman E, Berenstein EG, Diéguez M, Ortiz Z (July 2006). "Radiotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (3): CD003880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003880.pub4. PMC 8746191. PMID 16856023. S2CID 26025607.

- ^ Borasio P, Berruti A, Billé A, Lausi P, Levra MG, Giardino R, et al. (February 2008). "Malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinicopathologic and survival characteristics in a consecutive series of 394 patients". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 33 (2): 307–313. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.09.044. PMID 18164622.

- Tilleman RT, Richards WG (2009). "Extrapleural pneumonectomy followed by intracavitary intraoperative hyperthermic cisplatin with pharmacologic cytoprotection for treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma: A phase II prospective study". JTCVS. 138 (2): 405–11. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.046. PMID 19619785.

- Allen AM, Czerminska M, Jänne PA, Sugarbaker DJ, Bueno R, Harris JR, et al. (1 July 2006). "Fatal pneumonitis associated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy for mesothelioma". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 65 (3): 640–645. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.012. PMID 16751058.

- Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, Denham C, Kaukel E, Ruffie P, et al. (July 2003). "Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 21 (14): 2636–2644. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.11.136. PMID 12860938.

- ^ "FDA Approves Drug Combination for Treating Mesothelioma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 2 October 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Santoro A, O'Brien ME, Stahel RA, Nackaerts K, Baas P, Karthaus M, et al. (July 2008). "Pemetrexed plus cisplatin or pemetrexed plus carboplatin for chemonaïve patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: results of the International Expanded Access Program". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 3 (7): 756–763. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31817c73d6. PMID 18594322. S2CID 29137806.

- Green J, Dundar Y, Dodd S, Dickson R, Walley T (January 2007). Green JA (ed.). "Pemetrexed disodium in combination with cisplatin versus other cytotoxic agents or supportive care for the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (1): CD005574. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005574.pub2. PMC 8895712. PMID 17253564.

- Sugarbaker PH, Welch LS, Mohamed F, Glehen O (July 2003). "A review of peritoneal mesothelioma at the Washington Cancer Institute". Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. 12 (3): 605–621, xi. doi:10.1016/S1055-3207(03)00045-0. PMID 14567020.

Online manual: Sugarbaker PH (November 1998). Management of Peritoneal Surface Malignancy (Third ed.). Grand Rapids, Michigan: The Ludann Company. Archived from the original on 2005-12-28. - Ambrogi MC, Bertoglio P, Aprile V (2018). "Diaphragm and lung–preserving surgery with hyperthermic chemotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma: A 10-year experience". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 155 (4): 1857–1866.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.10.070. hdl:11568/888183. PMID 29191688. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- Richards WG, Zellos L, Bueno R, Jaklitsch MT, Jänne PA, Chirieac LR, et al. (April 2006). "Phase I to II study of pleurectomy/decortication and intraoperative intracavitary hyperthermic cisplatin lavage for mesothelioma". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (10): 1561–1567. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6813. PMID 16575008.

- ^ Abdel-Rahman O, Elsayed Z, Mohamed H, Eltobgy M (January 2018). "Radical multimodality therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD012605. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012605.pub2. PMC 6491325. PMID 29309720.

- Pass HI, Temeck BK, Kranda K, Steinberg SM, Feuerstein IR (February 1998). "Preoperative tumor volume is associated with outcome in malignant pleural mesothelioma". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 115 (2): 310–317, discussion 317–318. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70274-0. PMID 9475525.

- Sugarbaker DJ (February 2006). "Macroscopic complete resection: the goal of primary surgery in multimodality therapy for pleural mesothelioma". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 1 (2): 175–176. doi:10.1097/01243894-200602000-00014. PMID 17409850.

- Sugarbaker DJ, Jaklitsch MT, Bueno R, Richards W, Lukanich J, Mentzer SJ, et al. (July 2004). "Prevention, early detection, and management of complications after 328 consecutive extrapleural pneumonectomies". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 128 (1): 138–146. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.021. PMID 15224033.

- "Survival statistics for mesothelioma". cancer.org. 17 February 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Bianchi C, Bianchi T (June 2007). "Malignant mesothelioma: global incidence and relationship with asbestos". Industrial Health. 45 (3): 379–387. doi:10.2486/indhealth.45.379. PMID 17634686.

- Robinson BW, Lake RA (October 2005). "Advances in malignant mesothelioma". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (15): 1591–1603. doi:10.1056/NEJMra050152. PMID 16221782. S2CID 46621520.

- Restrepo CS, Vargas D, Ocazionez D, Martínez-Jiménez S, Betancourt Cuellar SL, Gutierrez FR (October 2013). "Primary pericardial tumors". Radiographics. 33 (6): 1613–1630. doi:10.1148/rg.336135512. PMID 24108554.

- "Asbestos Litigation Costs and Compensation: An Interim Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-24. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- Boffetta P (June 2007). "Epidemiology of peritoneal mesothelioma: a review". Annals of Oncology. 18 (6): 985–990. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdl345. PMID 17030547.

- "Mesothelioma statistics". Cancer Research UK. 2015-05-14. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- Wagner J, Sleggs C, Marchard P (1960). "Diffuse pleural mesothelioma and asbestos exposure in the North Western Cape Province". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 17 (4): 260–271. doi:10.1136/oem.17.4.260. PMC 1038078. PMID 13782506.

- "McLaren to be buried at Highgate". The Independent. 10 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2017-08-19. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Lerner BH (2005-11-15). "McQueen's Legacy of Laetrile". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- "Asbestos 'did not kill' producer". BBC News. 10 June 2003.

- Bradley PT (2016-07-05). "Asbestos Killed Warren Zevon — Now His Son Is Fighting to Ban It Once and for All". L.A. Weekly. Archived from the original on 2016-11-16. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- "Lives in the dust". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 September 2004.

- Branley A (7 May 2013). "Survivor sees his illness as a 'gift'". Herald News. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- "FW de Klerk diagnosed with cancer, undergoes treatment".

- "Paul Gleason, 67, 'Breakfast Club' Actor, Is Dead". The New York Times. No. 29 May 2016. Associated Press. 29 May 2006. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Gould SJ (2013). "The Median Isn't the Message". AMA Journal of Ethics. 15 (1): 77–81. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.1.mnar1-1301. PMID 23356812.

- ORTIZ V. FIBREBOARD CORP. (97-1704) 527 U.S. 815 (1999) had individual liability from a single corporation and its insurance carriers of nearly $2 billion.

- ORTIZ V. FIBREBOARD CORP. (97-1704) 527 U.S. 815 (1999)

- "H.R.982 - 113th Congress (2013-2014): Furthering Asbestos Claim Transparency (FACT) Act of 2013 - Congress.gov - Library of Congress". Library of Congress. 2013-11-14. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- "H.R.526 - 114th Congress (2015-2016): Furthering Asbestos Claim Transparency (FACT) Act of 2015 - Congress.gov - Library of Congress". Library of Congress. 2015-11-30. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 1 Dec 2015.

- Wagner JC, Sleggs CA, Marchand P (October 1960). "Diffuse pleural mesothelioma and asbestos exposure in the North Western Cape Province". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 17 (4): 260–271. doi:10.1136/oem.17.4.260. PMC 1038078. PMID 13782506.

- Moore AJ, Parker RJ, Wiggins J (December 2008). "Malignant mesothelioma". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 3: 34. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-3-34. PMC 2652430. PMID 19099560.

- Mcnulty JC (December 1962). "Malignant pleural mesothelioma in an asbestos worker". The Medical Journal of Australia. 49 (2): 953–954. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1962.tb24396.x. PMID 13932248. S2CID 40173789.

- "Wittenoom Chronology - Asbestos Diseases Society of Australia Inc". asbestosdiseases.org.au. Retrieved 2024-04-15.

- "June Hancock Research Fund". Archived from the original on 2010-01-28. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- Mott FE (2012). "Mesothelioma: a review". The Ochsner Journal. 12 (1): 70–79. PMC 3307510. PMID 22438785.

- This article includes information from a public domain U.S. National Cancer Institute fact sheet.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Cancer involving the respiratory tract | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper RT | |||||||||||||

| Lower RT |

| ||||||||||||

| Pleura | |||||||||||||

| Mediastinum | |||||||||||||

| Occupational safety and health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational diseases and injuries |

| ||||

| Occupational hygiene | |||||

| Professions | |||||

| Agencies and organizations |

| ||||

| Standards | |||||

| Safety |

| ||||

| Legislation | |||||

| See also |

| ||||