| This article possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (June 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Demographics of El Salvador | |

|---|---|

Population pyramid of El Salvador in 2020 Population pyramid of El Salvador in 2020 | |

| Population | 6,568,745 (2022 est.) |

| Growth rate | 0.57% (2022 est.) |

| Birth rate | 17.87 births/1,000 population (2022 est.) |

| Death rate | 5.91 deaths/1,000 population (2022 est.) |

| Life expectancy | 75.37 years |

| • male | 71.88 years |

| • female | 79.04 years |

| Fertility rate | 2.05 children born/woman (2022 est.) |

| Infant mortality rate | 12.14 deaths/1,000 live births |

| Net migration rate | -6.29 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2022 est.) |

| Age structure | |

| 0–14 years | 25.48% |

| 15–64 years | 65.47% |

| 65 and over | 9.06% |

| Sex ratio | |

| Total | 0.92 male(s)/female (2022 est.) |

| At birth | 1.05 male(s)/female |

| Under 15 | 1.05 male(s)/female |

| 65 and over | 0.68 male(s)/female |

| Nationality | |

| Nationality | Salvadoran |

| Major ethnic | Mestizo (86.3%) |

| Language | |

| Official | Spanish |

This is a demography of the population of El Salvador including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

El Salvador's population numbers 6.03 million. Ethnically, 86.3% of Salvadorans are mixed (mixed Native Salvadoran and European (mostly Spanish) origin). Another 12.7% is of pure European descent, 1% are of pure indigenous descent, 0.16% are black and others are 0.64%.

Population size and structure

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 1,434,361 | — |

| 1950 | 1,855,917 | +29.4% |

| 1961 | 2,510,984 | +35.3% |

| 1971 | 3,554,648 | +41.6% |

| 1992 | 5,118,599 | +44.0% |

| 2007 | 5,744,113 | +12.2% |

| 2024 | 6,029,976 | +5.0% |

| Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

| Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

El Salvador's population was 6,314,167 in 2021, compared to 2,200,000 in 1950. In 2010 the percentage of the population below the age of 15 was 32.1%, 61% were between 15 and 65 years of age, while 6.9% were 65 years or older.

| Year | Total population | Proportion per age group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 0–14 | Ages 15–64 | Ages 65+ | ||

| 1950 | 2,200,000 | 42.7% | 53.3% | 4.0% |

| 1955 | 2,433,000 | 43.6% | 52.6% | 3.8% |

| 1960 | 2,773,000 | 45.1% | 51.1% | 3.7% |

| 1965 | 3,244,000 | 46.3% | 50.1% | 3.7% |

| 1970 | 3,736,000 | 46.4% | 49.9% | 3.6% |

| 1975 | 4,232,000 | 45.8% | 50.5% | 3.7% |

| 1980 | 4,661,000 | 45.2% | 50.9% | 3.9% |

| 1985 | 5,004,000 | 44.1% | 51.8% | 4.2% |

| 1990 | 5,344,000 | 41.7% | 53.7% | 4.6% |

| 1995 | 5,748,000 | 39.6% | 55.5% | 4.9% |

| 2000 | 5,888,000 | 36.6% | 57.9% | 5.5% |

| 2005 | 6,052,000 | 34.8% | 58.9% | 6.3% |

| 2010 | 6,184,000 | 31.6% | 61.3% | 7.1% |

| 2015 | 6,325,000 | 28.4% | 63.9% | 7.8% |

| 2020 | 6,486,000 | 26.6% | 64.8% | 8.7% |

Structure of the population

Population by Sex and Age Group (Census 12.V.2007)::| Age group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2 719 371 | 3 024 742 | 5 744 113 | 100% |

| 0–4 | 283 272 | 272 621 | 555 893 | 9.68% |

| 5–9 | 349 150 | 335 577 | 684 727 | 11.92% |

| 10–14 | 359 523 | 346 824 | 706 347 | 12.30% |

| 15–19 | 298 384 | 302 181 | 600 565 | 10.46% |

| 20–24 | 228 001 | 258 541 | 486 542 | 8.47% |

| 25–29 | 206 963 | 250 927 | 457 890 | 7.97% |

| 30–34 | 178 400 | 223 849 | 402 249 | 7.00% |

| 35–39 | 156 514 | 196 633 | 353 147 | 6.15% |

| 40–44 | 132 218 | 171 413 | 303 631 | 5.29% |

| 45–49 | 109 957 | 142 165 | 252 122 | 4.39% |

| 50–54 | 95 275 | 120 459 | 215 734 | 3.76% |

| 55–59 | 81 718 | 101 357 | 183 075 | 3.19% |

| 60–64 | 68 207 | 83 657 | 151 864 | 2.64% |

| 65–69 | 55 781 | 69 376 | 125 157 | 2.18% |

| 70–74 | 43 449 | 54 008 | 97 457 | 1.70% |

| 75–79 | 33 658 | 42 326 | 75 984 | 1.32% |

| 80–84 | 20 401 | 26 469 | 46 870 | 0.82% |

| 85+ | 18 500 | 26 359 | 44 859 | 0.78% |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 991 945 | 955 022 | 1 946 967 | 33.89% |

| 15–64 | 1 555 637 | 1 851 182 | 3 406 819 | 59.31% |

| 65+ | 171 789 | 218 538 | 390 327 | 6.80% |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2 925 284 | 3 290 858 | 6 216 143 | 100% |

| 0–4 | 309 786 | 296 430 | 606 216 | 9.75% |

| 5–9 | 308 052 | 294 483 | 602 535 | 9.69% |

| 10–14 | 362 232 | 348 111 | 710 343 | 11.43% |

| 15–19 | 352 598 | 350 791 | 703 389 | 11.32% |

| 20–24 | 276 109 | 305 559 | 581 668 | 9.36% |

| 25–29 | 209 615 | 261 340 | 470 955 | 7.58% |

| 30–34 | 180 198 | 235 412 | 415 609 | 6.69% |

| 35–39 | 168 638 | 219 197 | 387 835 | 6.24% |

| 40–44 | 149 955 | 194 952 | 344 907 | 5.55% |

| 45–49 | 127 846 | 167 719 | 295 565 | 4.75% |

| 50–54 | 108 714 | 140 978 | 249 692 | 4.02% |

| 55–59 | 93 682 | 119 911 | 213 593 | 3.44% |

| 60–64 | 78 899 | 100 625 | 179 525 | 2.89% |

| 65–69 | 65 846 | 82 450 | 148 295 | 2.39% |

| 70–74 | 52 993 | 66 934 | 119 928 | 1.93% |

| 75–79 | 38 678 | 49 603 | 88 281 | 1.42% |

| 80+ | 41 443 | 56 363 | 97 806 | 1.57% |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | 980 070 | 939 024 | 1 919 094 | 30.87% |

| 15–64 | 1 746 254 | 2 096 484 | 3 842 738 | 61.82% |

| 65+ | 198 960 | 255 350 | 454 310 | 7.31% |

| Age Group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2 951 282 | 3 354 214 | 6 305 496 | 100% |

| 0–4 | 264 147 | 252 388 | 516 535 | 8.19% |

| 5–9 | 278 047 | 264 945 | 542 992 | 8.61% |

| 10–14 | 280 173 | 266 743 | 546 916 | 8.67% |

| 15–19 | 295 355 | 286 072 | 581 427 | 9.22% |

| 20–24 | 308 532 | 314 355 | 622 887 | 9.88% |

| 25–29 | 288 053 | 314 743 | 602 796 | 9.56% |

| 30–34 | 219 270 | 269 966 | 489 236 | 7.76% |

| 35–39 | 167 017 | 229 420 | 396 437 | 6.29% |

| 40–44 | 146 976 | 207 506 | 354 482 | 5.62% |

| 45–49 | 140 159 | 193 625 | 333 784 | 5.29% |

| 50–54 | 127 022 | 173 103 | 300 125 | 4.76% |

| 55–59 | 107 872 | 147 674 | 255 546 | 4.05% |

| 60–64 | 89 592 | 122 042 | 211 634 | 3.36% |

| 65–69 | 74 736 | 100 814 | 175 550 | 2.78% |

| 70–74 | 60 083 | 80 828 | 140 911 | 2.23% |

| 75–79 | 45 838 | 61 898 | 107 736 | 1.71% |

| 80–84 | 31 845 | 43 639 | 75 484 | 1.20% |

| 85+ | 31 030 | 40 319 | 71 349 | 1.13% |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 822 367 | 784 076 | 1 606 443 | 25.48% |

| 15–64 | 1 885 383 | 2 242 640 | 4 128 023 | 65.47% |

| 65+ | 243 532 | 327 498 | 571 030 | 9.06% |

Vital statistics

UN estimates

The Population Department of the United Nations prepared the following estimates.

| Period | Live births per year |

Deaths per year |

Natural change per year |

CBR* | CDR* | NC* | TFR* | IMR* | Life expectancy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | males | females | |||||||||

| 1950-1955 | 108 000 | 48 000 | 61 000 | 46.7 | 20.6 | 26.1 | 6.30 | 147 | 45.1 | 43.4 | 46.8 |

| 1955-1960 | 125 000 | 46 000 | 78 000 | 47.8 | 17.8 | 30.0 | 6.60 | 132 | 49.3 | 47.2 | 51.5 |

| 1960-1965 | 144 000 | 47 000 | 97 000 | 47.7 | 15.5 | 32.3 | 6.76 | 119 | 53.0 | 50.5 | 55.7 |

| 1965-1970 | 156 000 | 47 000 | 109 000 | 44.8 | 13.5 | 31.3 | 6.43 | 109 | 55.6 | 52.6 | 58.9 |

| 1970-1975 | 168 000 | 49 000 | 119 000 | 42.1 | 12.3 | 29.8 | 5.95 | 100 | 57.0 | 53.2 | 61.2 |

| 1975-1980 | 177 000 | 52 000 | 124 000 | 39.7 | 11.8 | 27.9 | 5.46 | 91 | 57.0 | 51.9 | 62.7 |

| 1980-1985 | 174 000 | 55 000 | 119 000 | 36.1 | 11.4 | 24.7 | 4.80 | 77 | 56.9 | 50.6 | 64.2 |

| 1985-1990 | 171 000 | 44 000 | 126 000 | 33.0 | 8.6 | 24.4 | 4.20 | 56 | 63.1 | 57.4 | 69.1 |

| 1990-1995 | 169 000 | 37 000 | 132 000 | 30.5 | 6.8 | 23.8 | 3.73 | 38 | 68.0 | 63.3 | 72.9 |

| 1995-2000 | 161 000 | 38 000 | 123 000 | 27.5 | 6.6 | 20.9 | 3.30 | 27 | 69.2 | 64.4 | 73.9 |

| 2000-2005 | 133 000 | 75 000 | 94 000 | 22.7 | 6.7 | 16.0 | 2.72 | 23 | 70.2 | 65.4 | 74.9 |

| 2005-2010 | 127 000 | 90 000 | 87 000 | 20.4 | 6.8 | 13.6 | 2.40 | 21 | 71.3 | 66.5 | 75.9 |

| 2010-2015 | 19.1 | 6.9 | 12.2 | 2.17 | |||||||

| 2015-2020 | 18.4 | 7.0 | 11.4 | 2.05 | |||||||

| 2020-2025 | 17.2 | 7.2 | 10.0 | 1.96 | |||||||

| 2025-2030 | 15.6 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 1.87 | |||||||

| * CBR = crude birth rate (per 1000); CDR = crude death rate (per 1000); NC = natural change (per 1000); IMR = infant mortality rate per 1000 births; TFR = total fertility rate (number of children per woman) | |||||||||||

Registered data

| Average population | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | Crude migration change (per 1000) | TFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 1,633,000 | 74,637 | 45.7 | ||||||

| 1941 | 1,654,000 | 72,376 | 43.8 | ||||||

| 1942 | 1,675,000 | 71,414 | 42.6 | ||||||

| 1943 | 1,697,000 | 71,554 | 42.2 | ||||||

| 1944 | 1,719,000 | 72,590 | 42.2 | ||||||

| 1945 | 1,742,000 | 74,660 | 42.9 | ||||||

| 1946 | 1,764,000 | 72,042 | 30,996 | 41,046 | 40.8 | 17.6 | 23.2 | -10.6 | |

| 1947 | 1,788,000 | 84,330 | 30,719 | 53,611 | 47.2 | 17.2 | 30.0 | -16.4 | |

| 1948 | 1,811,000 | 80,770 | 30,527 | 50,243 | 44.6 | 16.9 | 27.7 | -14.8 | |

| 1949 | 1,835,000 | 84,839 | 28,339 | 56,500 | 46.2 | 15.4 | 30.8 | -17.5 | |

| 1950 | 2,200,000 | 90,557 | 27,454 | 63,103 | 41.2 | 12.5 | 28.7 | ||

| 1951 | 2,237,000 | 93,634 | 29,030 | 64,604 | 41.8 | 13.0 | 28.9 | -12.1 | |

| 1952 | 2,280,000 | 96,802 | 32,423 | 64,379 | 42.5 | 14.2 | 28.2 | -9.0 | |

| 1953 | 2,327,000 | 98,474 | 30,280 | 68,194 | 42.3 | 13.0 | 29.3 | -8.7 | |

| 1954 | 2,378,000 | 102,009 | 31,810 | 70,199 | 42.9 | 13.4 | 29.5 | -7.6 | |

| 1955 | 2,433,000 | 105,040 | 31,151 | 73,889 | 43.2 | 12.8 | 30.4 | -7.3 | |

| 1956 | 2,491,000 | 106,539 | 28,127 | 78,412 | 42.8 | 11.3 | 31.5 | -7.7 | |

| 1957 | 2,553,000 | 114,929 | 32,893 | 82,036 | 45.0 | 12.9 | 32.1 | -7.2 | |

| 1958 | 2,621,000 | 115,154 | 32,831 | 82,323 | 43.9 | 12.5 | 31.4 | -4.8 | |

| 1959 | 2,694,000 | 115,622 | 30,038 | 85,584 | 42.9 | 11.1 | 31.8 | -3.9 | |

| 1960 | 2,773,000 | 121,403 | 28,768 | 92,635 | 43.8 | 10.4 | 33.4 | -4.1 | |

| 1961 | 2,859,000 | 124,871 | 28,471 | 96,400 | 43.7 | 10.0 | 33.7 | -2.7 | |

| 1962 | 2,951,000 | 127,154 | 30,342 | 96,812 | 43.1 | 10.3 | 32.8 | -0.6 | |

| 1963 | 3,047,000 | 133,395 | 29,614 | 103,781 | 43.8 | 9.7 | 34.1 | -1.6 | |

| 1964 | 3,145,000 | 133,072 | 29,496 | 103,576 | 42.3 | 9.4 | 32.9 | -0.7 | |

| 1965 | 3,244,000 | 137,430 | 30,906 | 106,524 | 42.4 | 9.5 | 32.8 | -1.3 | |

| 1966 | 3,342,000 | 137,950 | 30,368 | 107,582 | 41.3 | 9.1 | 32.2 | -2.0 | |

| 1967 | 3,440,000 | 139,955 | 28,957 | 110,998 | 40.7 | 8.4 | 32.2 | -2.9 | |

| 1968 | 3,537,000 | 140,986 | 29,863 | 111,123 | 39.8 | 8.4 | 31.4 | -3.2 | |

| 1969 | 3,636,000 | 142,699 | 33,655 | 109,044 | 39.2 | 9.2 | 29.9 | -1.9 | |

| 1970 | 3,736,000 | 141,471 | 35,094 | 106,377 | 37.8 | 9.4 | 28.4 | -0.9 | |

| 1971 | 3,836,000 | 154,309 | 28,752 | 125,557 | 40.2 | 7.5 | 32.7 | -5.9 | |

| 1972 | 3,938,000 | 153,464 | 32,383 | 121,081 | 38.9 | 8.2 | 30.7 | -4.1 | |

| 1973 | 4,038,000 | 155,632 | 31,865 | 123,767 | 38.5 | 7.9 | 30.6 | -5.2 | |

| 1974 | 4,137,000 | 158,524 | 30,494 | 128,030 | 38.3 | 7.4 | 30.9 | -6.4 | |

| 1975 | 4,232,000 | 159,731 | 31,601 | 128,130 | 37.7 | 7.5 | 30.3 | -7.3 | |

| 1976 | 4,325,000 | 165,822 | 30,826 | 134,996 | 38.3 | 7.1 | 31.2 | -9.2 | |

| 1977 | 4,414,000 | 177,531 | 33,009 | 144,522 | 40.2 | 7.5 | 32.7 | -12.1 | |

| 1978 | 4,500,000 | 172,897 | 30,086 | 142,811 | 38.4 | 6.7 | 31.7 | -12.2 | |

| 1979 | 4,582,000 | 174,183 | 32,936 | 141,247 | 38.0 | 7.2 | 30.8 | -12.6 | |

| 1980 | 4,661,000 | 169,930 | 38,967 | 130,963 | 36.4 | 8.4 | 28.1 | -10.9 | |

| 1981 | 4,734,000 | 163,305 | 37,468 | 125,837 | 34.5 | 7.9 | 26.6 | -10.9 | |

| 1982 | 4,805,000 | 156,796 | 33,284 | 123,512 | 32.6 | 6.9 | 25.7 | -10.7 | |

| 1983 | 4,872,000 | 144,193 | 32,697 | 111,496 | 29.6 | 6.7 | 22.9 | -9.0 | |

| 1984 | 4,938,000 | 142,202 | 28,854 | 113,348 | 28.8 | 5.8 | 23.0 | -9.5 | |

| 1985 | 5,004,000 | 139,514 | 27,225 | 112,289 | 27.9 | 5.4 | 22.5 | -9.1 | |

| 1986 | 5,069,000 | 145,126 | 25,731 | 119,395 | 28.7 | 5.1 | 23.6 | -10.6 | |

| 1987 | 5,134,000 | 148,355 | 27,581 | 120,774 | 28.9 | 5.4 | 23.6 | -10.8 | |

| 1988 | 5,200,000 | 149,299 | 27,774 | 121,525 | 28.8 | 5.4 | 23.4 | -10.5 | |

| 1989 | 5,269,000 | 151,859 | 27,768 | 124,091 | 28.9 | 5.3 | 23.6 | -10.3 | |

| 1990 | 5,344,000 | 148,360 | 28,195 | 120,165 | 27.8 | 5.3 | 22.5 | -8.3 | |

| 1991 | 5,425,000 | 151,210 | 27,066 | 124,144 | 27.9 | 5.0 | 22.9 | -7.7 | |

| 1992 | 5,511,000 | 154,014 | 27,869 | 126,145 | 27.9 | 5.1 | 22.9 | -7.0 | |

| 1993 | 5,597,000 | 168,000 | 38,000 | 130,000 | 30.0 | 6.8 | 23.2 | -7.6 | |

| 1994 | 5,678,000 | 160,772 | 29,407 | 131,365 | 28.3 | 5.2 | 23.1 | -8.6 | |

| 1995 | 5,748,000 | 159,336 | 29,130 | 130,206 | 27.7 | 5.1 | 22.7 | -10.4 | |

| 1996 | 5,807,000 | 163,007 | 28,904 | 134,103 | 28.1 | 5.0 | 23.1 | -12.8 | |

| 1997 | 5,855,000 | 164,143 | 29,118 | 135,025 | 28.0 | 5.0 | 23.1 | -14.8 | |

| 1998 | 5,895,000 | 158,350 | 29,919 | 128,431 | 26.9 | 5.1 | 21.8 | -15.0 | |

| 1999 | 5,929,000 | 153,636 | 28,056 | 125,580 | 25.9 | 4.7 | 21.2 | -15.4 | |

| 2000 | 5,959,000 | 150,176 | 28,154 | 122,022 | 25.2 | 4.7 | 20.5 | -15.4 | |

| 2001 | 5,985,000 | 138,354 | 29,959 | 108,395 | 23.1 | 5.0 | 18.1 | -13.7 | |

| 2002 | 6,008,000 | 129,363 | 27,458 | 101,905 | 21.5 | 4.6 | 17.0 | -13.2 | |

| 2003 | 6,029,000 | 124,476 | 29,377 | 95,099 | 20.6 | 4.9 | 15.8 | -12.3 | |

| 2004 | 6,050,000 | 119,710 | 30,058 | 89,652 | 19.8 | 5.0 | 14.8 | -11.4 | |

| 2005 | 6,073,000 | 112,769 | 30,933 | 81,836 | 18.6 | 5.1 | 13.5 | -9.7 | |

| 2006 | 6,097,000 | 107,111 | 31,453 | 75,658 | 17.6 | 5.2 | 12.4 | -8.4 | |

| 2007 | 6,123,000 | 106,471 | 31,349 | 75,122 | 17.4 | 5.1 | 12.3 | -8.0 | 2.4 |

| 2008 | 6,152,000 | 111,278 | 31,594 | 79,684 | 18.1 | 5.1 | 13.0 | -8.2 | |

| 2009 | 6,183,000 | 107,880 | 32,872 | 75,008 | 17.5 | 5.3 | 12.2 | -7.1 | |

| 2010 | 6,218,000 | 104,939 | 32,586 | 72,353 | 17.0 | 5.3 | 11.7 | -6.0 | |

| 2011 | 6,256,000 | 109,384 | 33,211 | 76,173 | 17.6 | 5.3 | 12.3 | -6.1 | |

| 2012 | 6,221,000 | 110,843 | 32,148 | 78,695 | 17.7 | 5.1 | 12.6 | -18.2 | 2.3 |

| 2013 | 6,219,000 | 109,617 | 34,212 | 75,405 | 17.4 | 5.4 | 12.0 | -12.2 | 2.2 |

| 2014 | 6,239,000 | 108,712 | 37,461 | 71,442 | 17.2 | 5.9 | 11.3 | -8.2 | |

| 2015 | 6,260,000 | 107,885 | 40,869 | 67,016 | 17.1 | 6.5 | 10.6 | -7.3 | |

| 2016 | 6,279,000 | 96,287 | 41,459 | 55,368 | 15.2 | 6.5 | 8.7 | -5.8 | |

| 2017 | 6,294,000 | 93,728 | 39,835 | 53,893 | 14.9 | 6.3 | 8.5 | -6.2 | |

| 2018 | 6,305,000 | 92,170 | 38,595 | 53,575 | 14,6 | 6,1 | 8.5 | -6.7 | |

| 2019 | 6,315,000 | 40,746 | 6.3 | ||||||

| 2020 | 6,321,000 | 87,680 | 51,325 | 36,355 | 13.9 | 8.1 | 5.8 | -4.8 | |

| 2021 | 6,326,000 | 77,383 | 51,103 | 26,280 | 12.2 | 8.1 | 4.1 | -3.4 | 1.8 |

| 2022 | 6,331,000 | ||||||||

| 2023 | |||||||||

| 2024 |

Ethnic groups

Out of the 6,408,111 people in El Salvador, 86.3% are Mestizo, 15% are European, 1% Indigenous, 0.8% Afro-Salvadorans, and 0.64% other.

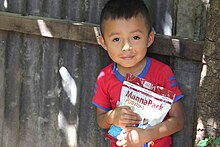

Indigenous Salvadorans

According to the Salvadoran government, about 1% of the population are of full or partial indigenous origin (principally Pipil, located in the west and central part of the country, and Lenca, found east of the Lempa River) also there are small populations of Cacaopera people in the Morazán Department. In the prehispanic age, the largest most dominant Native Salvadoran groups in the actual territory of El Salvador were the Lenca people and Pipil people followed by small enclaves of Maya peoples: (Poqomam people/Chorti people), Cacaopera people, Xinca people, and Mangue language people.

The number of indigenous people in El Salvador have been criticized by indigenous organizations and academics as too small and accuse the government of denying the existence of indigenous Salvadorans in the country. According to the National Salvadoran Indigenous Coordination Council (CCNIS) and CONCULTURA (National Council for Art and Culture at the Ministry of Education ), approximately 70,000 or 1 per cent of Salvadorian peoples are indigenous. Nonetheless, very few Amerindians have retained their customs and traditions, having over time assimilated into the dominant Mestizo/Spanish culture. The low numbers of indigenous people may be partly explained by historically high rates of old-world diseases, absorption into the Mestizo population, as well as mass murder during the 1932 Salvadoran peasant uprising (or La Matanza) which saw (estimates of) up to 30,000 peasants killed in a short period of time. Many authors note that since La Matanza the indigenous in El Salvador have been very reluctant to describe themselves as such (in census declarations for example) or to wear indigenous dress or be seen to be taking part in any cultural activities or customs that might be understood as indigenous. Departments and cities in the country with notable indigenous populations include Sonsonate (especially Izalco, Nahuizalco, Cuisnahuat, San Antonio del Monte, and Santo Domingo), Cacaopera, San Simón and Panchimalco, in the department of San Salvador.

-

Indigenous izalco family in Sonsonate

Indigenous izalco family in Sonsonate

-

indigenous Lenca people in Yucuaiquin 1988

indigenous Lenca people in Yucuaiquin 1988

-

indigenous Lencas in Yucuaiquin 2014

indigenous Lencas in Yucuaiquin 2014

-

Indigenous woman from Santo Domingo de Guzmán, El Salvador.

Indigenous woman from Santo Domingo de Guzmán, El Salvador.

-

Indigenous woman in El Salvador

Indigenous woman in El Salvador

-

Indigenous Salvadoran woman from Panchimalco

-

Salvadoran school children singing national anthem

Salvadoran school children singing national anthem

Mestizo Salvadorans

-

Salvadoran children from Metapan

-

young Salvadoran women in Ahuachapán.

young Salvadoran women in Ahuachapán.

-

Irma Dimas and other Salvadoran beauty queens

-

Salvadoran musical group in San Salvador

Salvadoran musical group in San Salvador

-

Salvadoran children in the beatification of Monseñor Oscar Romero

Salvadoran children in the beatification of Monseñor Oscar Romero

-

Salvadoran singer Jair Noyola and his father

Salvadoran singer Jair Noyola and his father

An estimated 86.3% of the population are Mestizo/Castizo, having mixed indigenous and European ancestry. Historical evidence and census supports the explanation of "strong sexual asymmetry", as a result of a strong bias favoring matings between European males and Native Salvadoran females, and to statistically significant indigenous male mortality during the Conquest. The genetics thus suggests the native men were sharply reduced in numbers due to the war and disease. Large numbers of Spaniard men settled in the region and had children with the local women. The Natives were forced to adopt Spanish names, language, and religion, and in this way, the Lencas and Pipil women and children were Westernised. A vast majority over 90% of Salvadorans are Mestizo/Native Salvadoran.

European Salvadorans

Spanish Salvadorans

-

A Galician Spanish family in the Chalatenango Department of El Salvador

A Galician Spanish family in the Chalatenango Department of El Salvador

-

Salarrué and his mother. Salarrué was an important Salvadoran writer, poet, and painter. Of Spanish descent, his father Alejandro Arrué Jimenez came to El Salvador from the Basque Country

Salarrué and his mother. Salarrué was an important Salvadoran writer, poet, and painter. Of Spanish descent, his father Alejandro Arrué Jimenez came to El Salvador from the Basque Country

-

Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado and his army first entered territories of what is now El Salvador in 1524, founding the city of San Salvador in 1525.

Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado and his army first entered territories of what is now El Salvador in 1524, founding the city of San Salvador in 1525.

-

General Manuel José Arce; decorated Salvadoran General and president of the Federal Republic of Central America from 1825 to 1829

General Manuel José Arce; decorated Salvadoran General and president of the Federal Republic of Central America from 1825 to 1829

Spaniards began to settle in El Salvador in the mid-1520s. Some 12.7% of Salvadorans are white. This population is made up of those of Spanish origin, while there are also Salvadorans of French, German, Swiss, English, Irish, and Italian descent. A majority of Central European settlers in El Salvador arrived during World War II as refugees from the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Switzerland with many settling in the region that is now Chalatenango in the late 18th century. In 1789, Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet was named governor of El Salvador. Because the local indigenous population working in the indigo industry had declined greatly, Carondolet recruited Spanish laborers from northern Spain to settle in El Salvador. In 1790, de Carondelet, ordered families from the north of Spain (Galicia, Asturias, the Basque Country, Cantabria and Navarra) to settle in the area to compensate for the lack of indigenous people to work the land; Important settlements of these Spaniards were the Northern and Center parts of El Salvador. Their descendants are among the blonde and fair-skinned people of today's Chalatenango Department.

During 1880 to 1920, El Salvador had its Migratory Peak of Immigrants from Europe, as well as immigrants from nearby countries, Asians and other North Americans, when more than 120,000 arrived in El Salvador, the demographic weight was unprecedented, in 1880 the Population was of 480,000 inhabitants and by 1920 it was already 1,170,000. the main groups were the Spanish, Italians, Germans and some French, Polish and British

French Salvadorans

-

French family in San Salvador, circa 1910–1915.

French family in San Salvador, circa 1910–1915.

-

Salvador Llort Choussy and his family. Salvador Llort and his brother Fernando Llort were artists, painters and sculpturists who are noted for their contribution in modern Salvadoran art often dubbed "El Salvador's National Artist"

Salvador Llort Choussy and his family. Salvador Llort and his brother Fernando Llort were artists, painters and sculpturists who are noted for their contribution in modern Salvadoran art often dubbed "El Salvador's National Artist"

The French Immigration to the Republic of El Salvador was an important movement that the country received between the 19th century and the middle of the 20th century. Between 1850 and 1870, the French formed the largest foreign group in El Salvador. Later in 1940 to 1950, they formed one of the largest groups in the country, only surpassed by the Spanish and Italians. Between 1850 and 1870, El Salvador was the main recipient of French in Central America, most were merchants and businessmen together with their families.

It is estimated that between 1850 and 1950, more than 7,000 French emigrated to El Salvador, the majority came from Aquitaine, Occitania and the Alps. Between 1850 and 1870, 2,000 French arrived in El Salvador; between 1911 and 1937, 2,000 French entered the country, and finally in 1938 to 1945, 2,500 French entered the country. French immigration at that time greatly influenced the economy and education.

Since the colonial period there is a record of French in Salvadoran territory, in which several French corsairs and French pirates stand out In 1850. Several French businessmen and merchants left for El Salvador to work in different types of jobs such as commerce, planting of sugar cane, industry and cultivation of coffee. During that time 2,000 French arrived in the territory, most were wealthy families and merchants. Most of the French who would arrive between 1880 and 1910 were merchants and professionals, but from 1911 to 1937, immigration would begin to shine again for various reasons. Many businessmen and merchants arrived in Salvadoran territory, at that time French investment in El Salvador was equal to that of the United States. During that period of time 2,000 French entered El Salvador. According to historical records, the French were the third largest group of foreigners in the country, only surpassed by the Spanish and Italians.

The majority of the French who arrived in the national territory first came from Corsica later in 1850 to 1950, the majority of the French who arrived in the territory were from Aquitaine, Occitanie and Rhône-Alpes but also Paris and other parts of the Alps, most of the French settled in San Salvador, however the City of Santa Tecla in the La Libertad Department (El Salvador) historically received large numbers of French Immigrants, other places with significant numbers are Santa Ana and Antiguo Cuscatlán.

German Salvadorans

-

German Salvadoran immigrants in Berlín, Usulután, German settlement in El Salvador

German Salvadoran immigrants in Berlín, Usulután, German settlement in El Salvador

-

German family in Santa Tecla, El Salvador, circa 1930–1940

German family in Santa Tecla, El Salvador, circa 1930–1940

German immigration to El Salvador was a migratory movement that began between 1880 and 1940, when the largest influx of Germans is recorded. The first Germans in El Salvador joined their mostly wealthy families in 1870 establishing coffee shops. At that time El Salvador had implemented the liberal reforms that attracted thousands of immigrants from Europe, Middle East and Asia, as well as the German immigration in the country, more families migrated to El Salvador and the agricultural land was also distributed. The main settlements of these families were the coffee-growing areas and also large cities like Nueva San Salvador now known as Santa Tecla, San Salvador, Chalatenango, Cuscatlan, Usulután and other areas where German immigrants saw economic opportunities in the country, they excelled in industry, commerce and farming.

One of the most famous Germans who immigrated to El Salvador was Walter Thilo Deininger, who moved to the Cuscatlan department in 1885. He soon built his coffee estate and other industries. Soon after, arrived more German families to Cuscatlán, as well as important people like Jürgen Hübner, a German historian and author of "Die Deutschen und El Salvador (The Germans and El Salvador).

By 1890, Germans were one of the country's largest immigrant groups and were able to settle and stand out from the crowd of other European immigrants. Germans numbers in El Salvador later increased, their descendants were much more than the number of German immigrants living in El Salvador. There were cities founded by German families, like Berlín, Usulután which is a very clear example of a settlement founded by a German. Later other Germans families came to the area. North of El Salvador, specifically what is now north of Metapan and Chalatenango, existed German settlements.

The Usulutan department was the area with the greatest presence of Germans in El Salvador. The Germans started arriving in the early 1900s and settled down to produce coffee.

The book, “The Population of El Salvador”, by Rodolfo Barón Castro, published in 1942, shows one of the first Statistical Census published by the Central Office of Migration in 1937; there it indicated that the four largest groups of immigrants in El Salvador, at that time, were made up of Spaniards, Palestinians, Italians and Germans. Germans arrived in the country in the early 1900s and, along with Italians, French and other Europeans, helped develop roads and build the Port of El Triunfo.

In addition, from the municipality of Berlín, Usulután there was a direct route to reach Puerto El Triunfo; an ideal route to transport the merchandise they produced and to obtain work materials.

It was the meeting point where German descendants and those close to Germany met to do their business because the farms were somewhat distant. They found in this part of El Salvador a center of excellence to live or develop, but they also needed to have a place to meet on weekends, to go and talk, which is typical of the cultures of these peoples: to have a meeting point.

The settlement was also agricultural. In 1958, the German Embassy in El Salvador founded the "Círculo Cultural Salvadoreño-Alemán", (German-Salvadoran cultural circle) to promote cultural exchange between Germany and El Salvador. The German School was dedicated on March 3, 1965, the Salvadoran German Cultural Forum has been celebrating every second Friday in November since 2006 Gardens of the Hilton Princess Hotel Oktoberfest. More than 700 people/families take part participate in a typically German dinner, German music and a typically German parade enjoy costumes. The traditional "Beer Festival" will continue thanks to the sponsorship of La Constancia and organized by German companies. The city of San Salvador, since 2011 in the third October week the Oktoberfest Pilsener celebrated in the exhibition and congress center. More than 27,000 people attended the 2013 edition, which became the largest Octoberfest in Central America. Over four days of festivities, participants enjoy traditional German cuisine and music, as well as a large selection of beers, some of which are made exclusively for the event.

Germany is one of the main European Union trading partners of El Salvador and is the largest importer of Salvadoran coffee. The Chamber of Commerce German-Salvadoran consists of around 85 companies. In addition to a German school in San Salvador.

Italian Salvadorans

Main article: Italian Salvadorans-

Massive documentation of Italian immigrants in San Salvador, during the 20th century

Massive documentation of Italian immigrants in San Salvador, during the 20th century

-

Juan Aberle, Italian-Salvadoran who composed the National Anthem of El Salvador

-

Alfredo Cristiani, former president of El Salvador, descendant of Italian immigrants

Alfredo Cristiani, former president of El Salvador, descendant of Italian immigrants

Italian Immigration in El Salvador refers to the movement of Italians to the Republic of El Salvador and one of the most historically important movements in El Salvador. The Italo-Salvadorans are one of the largest European communities in the country, and one of the largest in Central America and the Caribbean, as well as one of those with the greatest social and cultural weight in America.

During the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, waves of Italian immigrants from all regions of Italy were registered and arrived, mainly from northern Italy and southern Italy, the first Italians who arrived in the country were mainly from the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont, and also from the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which include several Italians from different cities and provinces, since 1880, there has been a flow from all Italian regions but mainly from the south of the peninsula. highlighting regions such as Campania, Basilicata, Apulia and Sicily.

There is a record of Italians residing and arriving in the country since 1850, who came from the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, several intellectuals, merchants and other lower-middle class Italians stand out, during those years several boats arrived to the country mainly from important port cities of Italy, which include Naples, Genoa and Palermo, most of these Italians entered through the port of La Libertad and in the East of the country, during that time the Italians in the country did not exceed 2,000, however in the following years the number of arrivals would grow more.

By 1870, more boats arrived from Naples and Genoa, ranging from 30 to 60 Italian immigrants, but many merchants also entered the country every day. During that period of time, the country created very free immigration reforms, which attracted more immigrants from the world, many Italians arrived between 1876 and 1879, several boats to the country stand out, mainly from Campania and Liguria, between 1870 and 1879, it is estimated that more than 2,500 Italians entered the country, at that time El Salvador was the main receiver of Italians in Central America, mainly attracted by various agricultural opportunities. In 1880 to 1889, more than 2,000 Italians arrived in the country mainly from Campania and Piedmont, many boats of more than 100 Italian immigrants arrived at the Salvadoran coasts, these boats sailed from Naples and Liguria, this time was highlighted by arrivals of lower-class Italians and some professionals, however, also there were nuns and priests who came to the country to found several churches, schools and important organizations. In 1890, Italian immigration grew exponentially, it is estimated that between 1890 and 1899, more than 6,500 Italians arrived in the country, the vast majority arrived at the port of La Libertad, several architects and other Italian professionals arrived, such as those who built the Santa Ana Theater.

In 1890, many Salesians arrived in the country from Turin, they set sail on ships full of Italian immigrants and arrived at the port of La Libertad Department (El Salvador), many stayed in the city of Santa Tecla, El Salvador, where they founded various organizations and schools such as the Colegio Santa Cecilia, which It was founded in 1899 by Italians.

In 1898, the first Italian organization was founded in El Salvador and the first in Central America, the Sociedad de Asistencia y Beneficencia entre Italianos en El Salvador, better known as the Italian Assistenza, the objective of this organization is to help newly arrived Italians to get a job and help them financially while they got it.

Twentieth century

The time was characterized by the massive entry of Italians into the country, between 1900 and 1909 more than 10,000 Italians arrived in the country from all Italian regions, at that time, El Salvador was the second largest recipient of Italian immigrants in Central America, many seeking better opportunities for their businesses and improve their quality of life, where several merchants and Italians entering the country stand out, many standing out in areas such as Education, Music, Agriculture, Industry, Commerce and infrastructure.

Between 1910 and 1919, other thousands of Italians enter as they register more than 6,000 arrivals in the country, the Italians easily adapted to the country and more Italians arrived in the country every day, El Salvador at that time managed to reach the main recipient of Italians in Central America, between 1920 and 1929, several Italian merchants and professionals arrived, but also lower-class Italians, many set up their businesses, in 1930, Italian immigration was paralyzed for various reasons, between 1930 and 1939, it is estimated that more than 1,000 Italians They arrived in the country and many set up their businesses.

In 1940, due to the Second World War, a large migratory wave of thousands of Italians emigrating to the country begins, where several merchants and Italians who wanted to improve their quality of life stand out, this time was characterized by the entry of several refugees, and Italians, most of whom came from northern Italy.

Between 1960 and 1980, several Franciscans arrived in the country, many founded schools and organizations to help the Salvadoran people, and also to reactivate the Italian culture in the country.

In 1989 a son of Italians, Alfredo Cristiani, was elected President of El Salvador. After five difficult years, his term ended in 1994, leaving his nation stabilized from the civil war that had plagued it for 20 years.

Italian immigration to El Salvador was a very large movement that the country received, from 1850 to 1929, it is estimated that more than 32,000 Italians arrived in the small country, looking for job opportunities and improvements in their quality of life, but the migratory peak It was between 1880 and 1930, when thousands of Italians from all regions arrived in El Salvador, the main recipients of Italians in America were the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and other countries in the region, although El Salvador received large amounts of Italian immigrants and at the American level is one that has had more weight socially and culturally.

Italian immigrants occupations and age

The Italians who arrived in the mid-nineteenth century were mostly middle class or poor, many were farmers and workers who came to the country to look for work, several merchants also arrived, according to some records, the Italians who arrived in the country between 1850 and 1870, were many families, who on average were between 22 and 26 years old, more 60% of immigrants who arrived in the country were men and 40% were women.

From 1870 to 1879, 2,5000 Italians arrived in the country, 63.5% were men, the average age was around 20 to 30 years and the majority were merchants, workers and farmers, between 1880 and 1889, they emigrated to the country around 2,000 Italians, 64% men and 44% women, age ranged widely, from 2 years to 50 years old, most were merchants, laborers and farmers, with increasing arrivals of priests, nuns and preachers. Between 1890 and 1891, the second highest peak was recorded, when 6,500 Italians entered El Salvador, the average age was around 20 to 30 years, and the most numerous occupations were merchants, workers, farmers, priests, nuns, teachers. and architects. The highest peak of Italian immigration in the country occurred between 1900 and 1909, when 10,000 Italians emigrated to the country looking for a better future, 60% were men and 40% women, and the average age was around 20 years. 30 years of age, the most numerous occupations were workers, merchants and some teachers, for 1910 to 1919, more than 6,000 Italians entered El Salvador, this year is distinguished by a growth of immigrants who are women with around 43% and 57% are men, the age varies between 3 years and 50 years, later, between 1920 and 1930, the majority who arrived in the country were engaged in commerce, agriculture and other businesses and activities.

Italian settlements in El Salvador

The first Italians who entered the country settled in Santa Ana and San Miguel. Others settled mainly in the east of the country, in San Miguel, Usulután and La Unión. In the north of the country, in Chalatenango, several groups of Italians also settled.

The southern Italians settled mainly in San Miguel, Santa Ana, San Salvador and other departments of the country, where several cities stand out. Santa Tecla was the one that received the greatest demographic weight due to Italian immigration, since it became the capital, they arrived various Italian communities.

The Lucanians, Campanians, Sicilians and Pulleses, had their main destinations in San Salvador, Santa Ana and San Miguel Department (El Salvador), while the northern Italians: the Piedmontese, Venetians, Ligurians and Lombards settled mainly in La Libertad, San Salvador, Chalatenango, Santa Ana and San Miguel. Several Italians settled in the department of Sonsonate, particularly from Castelnuovo di Conza in the Campania region, and Usulután received several Italian farmers from northern Italy, also in La Unión where several southerners and northerners settled, mainly Piedmontese and Calabrian. In the other departments of the country, minority but visible groups of Italians settled. succeeding in trade and agriculture.

Afro-Salvadorans

Afro-Salvadorans, called Pardo and sometimes Afro-Mestizos in the colonial period, are the descendants of the African population that were enslaved and shipped to El Salvador to work in mines in specific regions of El Salvador. They have mixed into and were naturally bred out by the general Mestizo population, which is a combination of a Mestizo majority and the minority of African descendants, both of whom are racially mixed populations. Thus, there remains no significant extremes of African physiognomy among Salvadorans like there is in the other countries of Central America. A total of only 10,000 African slaves were brought to El Salvador over the span of 75 years, starting around 1548, about 25 years after El Salvador's colonization. El Salvador is the only country in Central America that does not have English Antillean (West Indian) or Garifuna populations of the Caribbean, but instead had older colonial African slaves that came straight from Africa. This is the reason why El Salvador is the only country in Central America not to have a caribbeanized culture, and instead preserved its classical Central America culture.

Jewish Salvadorans

-

Representation of documents that were given to a Jewish family from Central Europe. Most of the Jews that came to El Salvador were from Germany, Poland, Hungary and Switzerland. 40,000 people were saved with Salvadoran citizenship documents like these, given by José Castellanos Contreras and José Gustavo Guerrero

Representation of documents that were given to a Jewish family from Central Europe. Most of the Jews that came to El Salvador were from Germany, Poland, Hungary and Switzerland. 40,000 people were saved with Salvadoran citizenship documents like these, given by José Castellanos Contreras and José Gustavo Guerrero

There is a small community of Jews who came to El Salvador from France, Germany, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey. Some Jews also arrived as World War II refugees.

Since colonial times, there is a record of Jews in Latin America, in El Salvador there is a record of several Jewish immigrations from Portugal, after the independence of El Salvador, it is believed that the first Jewish immigrant was Bernardo Haas, born in Alsace. Subsequently, the first documented German Jew arrived in the country in 1888, according to scholar Jessica Alpert. France and Central Europe were the main countries of origin of this contemporary Jewish migration, the majority were Ashkenazi and Sephardic, they stayed permanently in El Salvador.

The immigration laws of El Salvador were very free between 1821 and 1930, however they changed after 1930, but these strict laws culminated in 1940, during the Second World War several Ashkenazi Jewish refugees arrived mainly from Hungary, Germany, Poland, Switzerland, Slovakia and France, giving them several documents of Salvadoran nationality.

At present the Jewish community in El Salvador is quite small, however there are a considerable number of descendants and they have stood out in society, as are several businessmen and politicians of Jewish origin, such as Ernesto Muyshondt, Gabriela Rodríguez de Bukele and Bernard Lewinsky.

Gypsies in El Salvador

The Gypsy caravans in El Salvador in the 20th century. The city of Santa Tecla, El Salvador was one of the places where there were Gypsy camps in El Salvador in the first decades of the 20th century. On May 7, 1926, newspapers from the city of San Miguel, El Salvador reported that within its urban area there was a nomadic community of Gypsies, who were also called Hungarians or Magyars (for Magyar or Hungary, an area from which they then belonged) believed that they were originally from), Gypsies or "peroleros", a designation due to the huge pots or pans that they always carried in their wagons and with which they prepared community meals between huge wood-fired stoves.

In 1929, the writer Francisco Miranda Ruano would remember "The tired Gypsies of that day" from his distant childhood and whose adventures opened his vocation as a writer. The propagation of theosophical, fascist and national socialist ideas among soldiers and civilians in El Salvador in the 1920s and 1930s created an adverse environment for the periodic arrival of the Gypsy people in El Salvador. The maximum expression of this mental and cultural closure occurred during the dictatorial government of Brigadier Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, issued the Law of Migration that prohibited the entry of Blacks, Arabs, Turks, Chinese and Gypsies into the country. This cause Gypsies in El Salvador to hide their identity.

The Romani Holocaust in Nazi Europe from 1935 to 1945, killed thousands of Gypsy people. Some of them were able to save themselves from that sad fate, thanks to the thousands of Salvadoran nationality certificates issued, in a clandestine operation, by the Salvadoran consul in Geneva, Colonel José Castellanos Contreras, José Gustavo Guerrero and his Transylvanian-Jewish secretary George Mandel-Mantello.

In the 1980s, the writer Claribel Alegría included the character "The Gypsy" in her novel Alice in the Land of Reality, which functioned as a rebellious and feminist conscience within the literary structure of the work. At the same time, it turned out be a tribute to the Gypsy caravans that once passed through Santa Ana, Sonsonate, Nahulingo, Usulután, Santiago de María, Chalatenango, San Miguel, La Unión and many towns, streets, cities and other local territories of El Salvador.

More than eight decades after such terrible racist legislation, the Romani language is no longer heard in Salvadoran territory. In the Romani language, the father of the family is called "Shero Rom", and it is theorized that it could be the origin of the Salvadoran word “Chero” to designate a friend.

Arab Salvadorans

-

Arab Salvadorans include Palestinian Salvadoran, Lebanese Salvadoran, Syrian Salvadoran and Egyptian Salvadoran.

Arab Salvadorans include Palestinian Salvadoran, Lebanese Salvadoran, Syrian Salvadoran and Egyptian Salvadoran.

-

Manzue family from Bethlehem Palestine, arrived to El Salvador in 1910

Manzue family from Bethlehem Palestine, arrived to El Salvador in 1910

-

Khader (Cader) family migrated from Palestine to El Salvador, circa 1925

Khader (Cader) family migrated from Palestine to El Salvador, circa 1925

-

Palestinian family in Usulután El Salvador 1952

Palestinian family in Usulután El Salvador 1952

-

Palestinian children refugees in El Salvador

Palestinian children refugees in El Salvador

-

Children of Palestinian ancestry celebrating (Palestinian Day) at the Club Arabe Salvadoreño "Arab-Salvadoran Club"

Children of Palestinian ancestry celebrating (Palestinian Day) at the Club Arabe Salvadoreño "Arab-Salvadoran Club"

-

Descendants of Palestinians take a picture beside a bust of Yasir Arafat, San Salvador

Descendants of Palestinians take a picture beside a bust of Yasir Arafat, San Salvador

There is a significant Arab population (of about 100,000); mostly from Palestine (especially from the area of Bethlehem), but also from Lebanon. Salvadorans of Palestinian descent numbered around 70,000 individuals, while Salvadorans of Lebanese descent is around 25,000.

The history of the Arabs in El Salvador dates back to the end of the 19th century, when religious clashes in the Ottoman Empire induced many Palestinians, Lebanese, Egyptians, Tunisians, Algerians, Iraqis, Omani, Saudis and Syrians to leave the land where they were born and travel to El Salvador in search of a place where they could live in relative peace. For similar reasons Turkish people and Persian Christians from Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan also arrived to El Salvador around the same time. There were also economic factors that contributed to immigration from the Middle East; many immigrants felt they could achieve success abroad on a level they couldn't in their native lands.

The first wave of Arab migration to El Salvador began between 1880 and 1920, amidst a large scale influx of immigrants to the country. These Arabs settled in the cities of San Salvador, San Miguel, Santa Ana, Santa Tecla, Usulutan and La Union. The population of El Salvador increased from 482,400 in 1879 to 1,168,000 in 1920, with immigration, including immigration from the late Ottoman Empire, substantially driving growth.

Arab immigration in El Salvador began at the end of the 19th century in the wake of the repressive policies applied by the Ottoman Empire against Maronite Catholics. Several of the destinations that the Lebanese chose at that time were in countries of the Americas, including El Salvador. This resulted in the Arab diaspora residents being characterized by forging in devoutly Christian families and very attached to their beliefs, because in these countries they can exercise their faith without fear of persecution, which resulted in the rise of Lebanese-Salvadoran, Syrian-Salvadoran and Palestinian-Salvadoran communities in El Salvador.

Currently, the Palestinian community forms the largest Arab diaspora population in El Salvador, with 70,000 direct descendants, followed by the Lebanese community with more than 27,000 direct descendants. Both are almost entirely composed of Catholic and Orthodox Christians. The slaughter of Lebanese and Palestinian Arab Christians at the hands of Muslims initiated the first Arab migrations to El Salvador.

Inter-ethnic marriage in the Lebanese community with Salvadorans, regardless of religious affiliation, is very high; most have only one father with Lebanese nationality and mother of Salvadoran nationality. As a result, some of them speak Arabic fluently. But most, especially among younger generations, speak Spanish as a first language and Arabic as a second.

During the war between Israel and Lebanon in 1948 and during the Six-Day War, thousands of Lebanese left their country and went to El Salvador. Many arrived at La Libertad, where they comprised half of the economic activity of immigrants.

Lebanon had been an iqta of the Ottoman Empire. Although the imperial administration, whose official religion was Islam, guaranteed freedom of worship for non-Muslim communities, and Lebanon in particular had a semi-autonomous status, the situation for practitioners of the Maronite Catholic Church was complicated, since they had to cancel exaggerated taxes and suffered limitations for their culture. These tensions were expressed in a rebellion in 1821 and a war against the Druze in 1860. The hostile climate caused many Lebanese to sell their property and take ships in the ports of Sidon, Beirut and Tripoli heading for the Americas.

Arab-Salvadoreans and their descendants have traditionally played an outsized role in El Salvador's economic and political life, with many becoming business leaders and noteworthyt political figures.

In 1939, the Arab community based in San Salvador organized and founded the "Arab Youth Union Society"

Emigration

The migration rate accelerated during the period of 1979 to 1981, this marked the beginning of the civil unrest and the spread of political killings. The total impact of civil wars, dictatorships and socioeconomics drove over a million Salvadorans (both as immigrants and refugees) into the United States; Guatemala is the second country that hosts more Salvadorans behind the United States, approximately 110,000 Salvadorans according to the national census of 2010. in addition small Salvadoran communities sprung up in Canada, Australia, Belize, Panama, Costa Rica, Italy, Taiwan and Sweden since the migration trend began in the early 1970s. The 2010 U.S. census counted 1,648,968 Salvadorans in the United States, up from 655,165 in 2000.

See also

- El Salvador

- Ethnic groups in Central America

- History of the Jews in El Salvador

- Salvadoran Departments by HDI

- Catholic Church in El Salvador

- Central America

- Culture of El Salvador

- German Salvadoran

- Geography of El Salvador

- Italian Salvadorans

- Monumento al Divino Salvador del Mundo

- Music of El Salvador

- Palestinian Salvadoran

- Religion in El Salvador

- Salvadorans

- Salvadoran Americans

- Salvadoran cuisine

- Salvadoran Spanish

- San Salvador

- Swiss Salvadorans

References

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ "Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision". Esa.un.org. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "UNSD — Demographic and Social Statistics". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ^ "United Nations Statistics Division - Demographic and Social Statistics". Unstats.un.org. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Amaroli, Paul (1992). Algunos grupos cerámicos pipiles en El Salvador.

- Fowler, William (1995). Antiguas civilizaciónes. Banco Agrícola.

- Ministerio de Educación (2009). Historia de El Salvador.

- Ayala, Edgardo (14 May 2012). "Native People of El Salvador Finally Gain Recognition". Ipsnews.net. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "El Salvador - Indigenous peoples". Minority Rights Group International. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "Jose Napoleon Duarte, Hernandez Martinez, Ungo, Matanza, Central American Common Market, CACM, urban middle class, Christian Democratic Party, powerful families, death squads, Organization of American States, PRUD, International Court Of Justice, urban center, rapid population growth". Countriesquest.com. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "En este mestizaje, hay tres grandes raíces fundamentales: La indígena, la negra y la española".

- "El Salvador". 5 November 2021.

- "Carondelet". NCH Historias Multimedia. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "La gente blanca de Chalatenango". 22 November 2011.

- "Inmigracion Europea en Centroamérica Después de la Colonia ( 1)".

- "Ser extranjero en Centroamérica. Génesis y evolución de las leyes de extranjería y migración en El Salvador: siglos XIX y XX".

- "Inmigrantes italianos en El Salvador_ Historia y cultura.pdf - Google Drive". Archived from the original on 2021-06-29.

- ^ "Deutsche In El Salvador" – via Internet Archive.

- Gómez, Moisés (2017). "Ser extranjero en Centroamérica. Génesis y evolución de las leyes de extranjería y migración en el Salvador: Siglos XIX y XX". Realidad: Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades (135): 117–151. doi:10.5377/realidad.v0i135.3167.

- (In Spanish) La Prensa Gráfica La cofradía de Don Balta Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine El Salvador, 22 September 2013. Retrieved, 26-11-2014

- "La historia del diplomático católico que salvó 40 mil judíos del holocausto".

- (In German) Auswärtiges Amt-El Salvador Information from Germany about El Salvador

- "El Salvador project illustrates the 'invisible' African roots of common Latin American words · Global Voices". 4 February 2021.

- "Learning about my blackness afrodescendencia in El Salvador". 31 July 2020. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "La herencia africana en la historia salvadoreña | Bicentenario del Primer Grito de Independencia".

- "La invisible herencia africana de El Salvador". La invisible herencia africana de El Salvador.

- "Las huellas de la Afrodescendencia en El Salvador". 29 August 2018.

- "AFROMESTIZO :: African Heritage of Central America :: El Salvador :: Lest We Forget". lestweforget.hamptonu.edu.

- "El Salvador Virtual Jewish History Tour".

- Alpert, Jessica. "The History of the Jewish Community in El Salvador". oral.history.ufl.edu. University of Florida. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "Community jews El Salvador". Worldjewishcongress.org. World jewish congress. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "REFUGE IN LATIN AMERICA". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. HOLOCAUST ENCYCLOPEDIA. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "Castellanos, el Schindler salvadoreño, salta a la gran pantalla". efe.com. Agencia EFE. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "La historia del diplomático católico que salvó 40 mil judíos del holocausto". aciprensa.com. ACI prensa. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- Usi, Eva. "Rinden homenaje en Berlín al "Schindler" salvadoreño". DW. DW news. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "i am Salvadoran i am Romani".

- "The Gypsy caravans in El Salvador". 13 April 2019.

- Zielger, Matthew. "El Salvador: Central American Palestine of the West?". The Daily Star. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "Lebanese Diaspora – Worldwide Geographical Distribution". Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "EL SALVADOR, historical demographical data of the whole country". Archived from the original on 2015-03-21.

- "AJ Plus: The Palestinians of El Salvador". latinx.com. May 29, 2019. Archived from the original on November 13, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- "Why So Many Palestinians Live in el Salvador | AJ+". Archived from the original on 2019-11-13. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "Lebanese Diaspora Worldwide Geographical Distribution". Archived from the original on 2021-02-14. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

- "El Salvador vote divides 2 Arab clans". Chicago Tribune. March 21, 2004.

- Jones, Richard C. (April 1989). "Causes of Salvadoran Migration to the United States". Geographical Review. 79 (2): 183–194. Bibcode:1989GeoRv..79..183J. doi:10.2307/215525. JSTOR 215525.

- "Institución". Ine.gob.gt. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "Mapa de las Migraciones Salvadoreñas". PNUD El Salvador. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". Retrieved 2011-04-25.

| Ancestry and ethnicity in El Salvador | |

|---|---|

| Indigenous | |

| Non-Indigenous | |

| El Salvador articles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||

| Geography | |||||

| Politics | |||||

| Economy | |||||

| Society |

| ||||

| Demographics of North America | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states | |

| Dependencies and other territories | |