| Humidity and hygrometry |

|---|

|

| Specific concepts |

| General concepts |

| Measures and instruments |

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation, dew, or fog to be present.

Humidity depends on the temperature and pressure of the system of interest. The same amount of water vapor results in higher relative humidity in cool air than warm air. A related parameter is the dew point. The amount of water vapor needed to achieve saturation increases as the temperature increases. As the temperature of a parcel of air decreases it will eventually reach the saturation point without adding or losing water mass. The amount of water vapor contained within a parcel of air can vary significantly. For example, a parcel of air near saturation may contain 8 g of water per cubic metre of air at 8 °C (46 °F), and 28 g of water per cubic metre of air at 30 °C (86 °F)

Three primary measurements of humidity are widely employed: absolute, relative, and specific. Absolute humidity is expressed as either mass of water vapor per volume of moist air (in grams per cubic meter) or as mass of water vapor per mass of dry air (usually in grams per kilogram). Relative humidity, often expressed as a percentage, indicates a present state of absolute humidity relative to a maximum humidity given the same temperature. Specific humidity is the ratio of water vapor mass to total moist air parcel mass.

Humidity plays an important role for surface life. For animal life dependent on perspiration (sweating) to regulate internal body temperature, high humidity impairs heat exchange efficiency by reducing the rate of moisture evaporation from skin surfaces. This effect can be calculated using a heat index table, or alternatively using a similar humidex.

The notion of air "holding" water vapor or being "saturated" by it is often mentioned in connection with the concept of relative humidity. This, however, is misleading—the amount of water vapor that enters (or can enter) a given space at a given temperature is almost independent of the amount of air (nitrogen, oxygen, etc.) that is present. Indeed, a vacuum has approximately the same equilibrium capacity to hold water vapor as the same volume filled with air; both are given by the equilibrium vapor pressure of water at the given temperature. There is a very small difference described under "Enhancement factor" below, which can be neglected in many calculations unless great accuracy is required.

Definitions

Absolute humidity

Absolute humidity is the total mass of water vapor (gas form of water) present in a given volume or mass of air. It does not take temperature into consideration. Absolute humidity in the atmosphere ranges from near zero to roughly 30 g (1.1 oz) per cubic metre when the air is saturated at 30 °C (86 °F).

Air is a gas, and its volume varies with pressure and temperature, per Boyles law. Absolute humidity is defined as water mass per volume of air. A given mass of air will grow or shrink as the temperature or pressure varies. So the absolute humidity of a mass of air will vary due to changes in temperature or pressure, even when the proportion of water in that mass of air (its specific humidity) remains constant. This makes the term absolute humidity as defined not ideal for some situations.

Absolute humidity is the mass of the water vapor , divided by the volume of the air and water vapor mixture , which can be expressed as: In the equation above, if the volume is not set, the absolute humidity varies with changes in air temperature or pressure. Because of this variability, use of the term absolute humidity as defined is inappropriate for computations in chemical engineering, such as drying, where temperature variations might be significant. As a result, absolute humidity in chemical engineering may refer to mass of water vapor per unit mass of dry air, also known as the humidity ratio or mass mixing ratio (see "specific humidity" below), which is better suited for heat and mass balance calculations. Mass of water per unit volume as in the equation above is also defined as volumetric humidity. Because of the potential confusion, British Standard BS 1339 suggests avoiding the term "absolute humidity". Units should always be carefully checked. Many humidity charts are given in g/kg or kg/kg, but any mass units may be used.

Relative humidity

Relative humidity is the ratio of how much water vapour is in the air to how much water vapour the air could potentially contain at a given temperature. It varies with the temperature of the air: colder air can contain less vapour, and water will tend to condense out of the air more at lower temperatures. So changing the temperature of air can change the relative humidity, even when the absolute humidity remains constant.

Chilling air increases the relative humidity. If the relative humidity rises over 100% (the dew point) and there is an available surface or particle, the water vapour will condense into liquid or ice. Likewise, warming air decreases the relative humidity. Warming some air containing a fog may cause that fog to evaporate, as the droplets are prone to total evaporation due to the lowering partial pressure of water vapour in that air, as the temperature rises.

Relative humidity only considers the invisible water vapour. Mists, clouds, fogs and aerosols of water do not count towards the measure of relative humidity of the air, although their presence is an indication that a body of air may be close to the dew point.

Relative humidity is normally expressed as a percentage; a higher percentage means that the air–water mixture is more humid. At 100% relative humidity, the air is saturated and is at its dew point. In the absence of a foreign body on which droplets or crystals can nucleate, the relative humidity can exceed 100%, in which case the air is said to be supersaturated. Introduction of some particles or a surface to a body of air above 100% relative humidity will allow condensation or ice to form on those nuclei, thereby removing some of the vapour and lowering the humidity.

In a scientific notion, the relative humidity ( or ) of an air-water mixture is defined as the ratio of the partial pressure of water vapor () in air to the saturation vapor pressure () of water at the same temperature, usually expressed as a percentage:

Relative humidity is an important metric used in weather forecasts and reports, as it is an indicator of the likelihood of precipitation, dew, or fog. In hot summer weather, a rise in relative humidity increases the apparent temperature to humans (and other animals) by hindering the evaporation of perspiration from the skin. For example, according to the heat index, a relative humidity of 75% at air temperature of 80.0 °F (26.7 °C) would feel like 83.6 ± 1.3 °F (28.7 ± 0.7 °C).

Relative humidity is also a key metric used to evaluate when it is appropriate to install flooring over a concrete slab.

Specific humidity

Specific humidity (or moisture content) is the ratio of the mass of water vapor to the total mass of the air parcel. Specific humidity is approximately equal to the mixing ratio, which is defined as the ratio of the mass of water vapor in an air parcel to the mass of dry air for the same parcel. It is typically represented with the symbol ω, and is commonly used in HVAC system design.

Related concepts

The term relative humidity is reserved for systems of water vapor in air. The term relative saturation is used to describe the analogous property for systems consisting of a condensable phase other than water in a non-condensable phase other than air.

Measurement

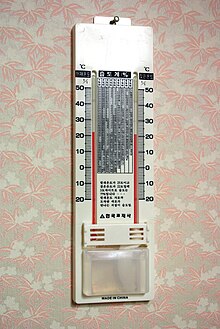

A device used to measure humidity of air is called a psychrometer or hygrometer. A humidistat is a humidity-triggered switch, often used to control a humidifier or a dehumidifier.

The humidity of an air and water vapor mixture is determined through the use of psychrometric charts if both the dry bulb temperature (T) and the wet bulb temperature (Tw) of the mixture are known. These quantities are readily estimated by using a sling psychrometer.

There are several empirical formulas that can be used to estimate the equilibrium vapor pressure of water vapor as a function of temperature. The Antoine equation is among the least complex of these, having only three parameters (A, B, and C). Other formulas, such as the Goff–Gratch equation and the Magnus–Tetens approximation, are more complicated but yield better accuracy.

The Arden Buck equation is commonly encountered in the literature regarding this topic: where is the dry-bulb temperature expressed in degrees Celsius (°C), is the absolute pressure expressed in millibars, and is the equilibrium vapor pressure expressed in millibars. Buck has reported that the maximal relative error is less than 0.20% between −20 and +50 °C (−4 and 122 °F) when this particular form of the generalized formula is used to estimate the equilibrium vapor pressure of water.

There are various devices used to measure and regulate humidity. Calibration standards for the most accurate measurement include the gravimetric hygrometer, chilled mirror hygrometer, and electrolytic hygrometer. The gravimetric method, while the most accurate, is very cumbersome. For fast and very accurate measurement the chilled mirror method is effective. For process on-line measurements, the most commonly used sensors nowadays are based on capacitance measurements to measure relative humidity, frequently with internal conversions to display absolute humidity as well. These are cheap, simple, generally accurate and relatively robust. All humidity sensors face problems in measuring dust-laden gas, such as exhaust streams from clothes dryers.

Humidity is also measured on a global scale using remotely placed satellites. These satellites are able to detect the concentration of water in the troposphere at altitudes between 4 and 12 km (2.5 and 7.5 mi). Satellites that can measure water vapor have sensors that are sensitive to infrared radiation. Water vapor specifically absorbs and re-radiates radiation in this spectral band. Satellite water vapor imagery plays an important role in monitoring climate conditions (like the formation of thunderstorms) and in the development of weather forecasts.

Air density and volume

Main articles: Volume (thermodynamics), Density of air, and Ideal gas lawHumidity depends on water vaporization and condensation, which, in turn, mainly depends on temperature. Therefore, when applying more pressure to a gas saturated with water, all components will initially decrease in volume approximately according to the ideal gas law. However, some of the water will condense until returning to almost the same humidity as before, giving the resulting total volume deviating from what the ideal gas law predicted.

Conversely, decreasing temperature would also make some water condense, again making the final volume deviate from predicted by the ideal gas law. Therefore, gas volume may alternatively be expressed as the dry volume, excluding the humidity content. This fraction more accurately follows the ideal gas law. On the contrary the saturated volume is the volume a gas mixture would have if humidity was added to it until saturation (or 100% relative humidity).

Humid air is less dense than dry air because a molecule of water (m ≈ 18 Da) is less massive than either a molecule of nitrogen (m ≈ 28) or a molecule of oxygen (m ≈ 32). About 78% of the molecules in dry air are nitrogen (N2). Another 21% of the molecules in dry air are oxygen (O2). The final 1% of dry air is a mixture of other gases.

For any gas, at a given temperature and pressure, the number of molecules present in a particular volume is constant. Therefore, when some number N of water molecules (vapor) is introduced into a volume of dry air, the number of air molecules in that volume must decrease by the same number N for the pressure to remain constant without using a change in temperature. The numbers are exactly equal if we consider the gases as ideal. The addition of water molecules, or any other molecules, to a gas, without removal of an equal number of other molecules, will necessarily require a change in temperature, pressure, or total volume; that is, a change in at least one of these three parameters.

If temperature and pressure remain constant, the volume increases, and the dry air molecules that were displaced will initially move out into the additional volume, after which the mixture will eventually become uniform through diffusion. Hence the mass per unit volume of the gas—its density—decreases. Isaac Newton discovered this phenomenon and wrote about it in his book Opticks.

Pressure dependence

The relative humidity of an air–water system is dependent not only on the temperature but also on the absolute pressure of the system of interest. This dependence is demonstrated by considering the air–water system shown below. The system is closed (i.e., no matter enters or leaves the system).

If the system at State A is isobarically heated (heating with no change in system pressure), then the relative humidity of the system decreases because the equilibrium vapor pressure of water increases with increasing temperature. This is shown in State B.

If the system at State A is isothermally compressed (compressed with no change in system temperature), then the relative humidity of the system increases because the partial pressure of water in the system increases with the volume reduction. This is shown in State C. Above 202.64 kPa, the RH would exceed 100% and water may begin to condense.

If the pressure of State A was changed by simply adding more dry air, without changing the volume, the relative humidity would not change.

Therefore, a change in relative humidity can be explained by a change in system temperature, a change in the volume of the system, or change in both of these system properties.

Enhancement factor

The enhancement factor is defined as the ratio of the saturated vapor pressure of water in moist air to the saturated vapor pressure of pure water:

The enhancement factor is equal to unity for ideal gas systems. However, in real systems the interaction effects between gas molecules result in a small increase of the equilibrium vapor pressure of water in air relative to equilibrium vapor pressure of pure water vapor. Therefore, the enhancement factor is normally slightly greater than unity for real systems.

The enhancement factor is commonly used to correct the equilibrium vapor pressure of water vapor when empirical relationships, such as those developed by Wexler, Goff, and Gratch, are used to estimate the properties of psychrometric systems.

Buck has reported that, at sea level, the vapor pressure of water in saturated moist air amounts to an increase of approximately 0.5% over the equilibrium vapor pressure of pure water.

Effects

Climate control refers to the control of temperature and relative humidity in buildings, vehicles and other enclosed spaces for the purpose of providing for human comfort, health and safety, and of meeting environmental requirements of machines, sensitive materials (for example, historic) and technical processes.

Climate

See also: Precipitation (meteorology) and Humid subtropical climate

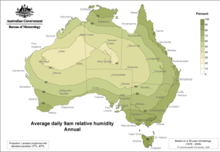

While humidity itself is a climate variable, it also affects other climate variables. Environmental humidity is affected by winds and by rainfall.

The most humid cities on Earth are generally located closer to the equator, near coastal regions. Cities in parts of Asia and Oceania are among the most humid. Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Manila, Jakarta, Naha, Singapore, Kaohsiung and Taipei have very high humidity most or all year round because of their proximity to water bodies and the equator and often overcast weather.

Some places experience extreme humidity during their rainy seasons combined with warmth giving the feel of a lukewarm sauna, such as Kolkata, Chennai and Kochi in India, and Lahore in Pakistan. Sukkur city located on the Indus River in Pakistan has some of the highest and most uncomfortable dew points in the country, frequently exceeding 30 °C (86 °F) in the monsoon season.

High temperatures combine with the high dew point to create heat index in excess of 65 °C (149 °F). Darwin experiences an extremely humid wet season from December to April. Houston, Miami, San Diego, Osaka, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Tokyo also have an extreme humid period in their summer months. During the South-west and North-east Monsoon seasons (respectively, late May to September and November to March), expect heavy rains and a relatively high humidity post-rainfall.

Outside the monsoon seasons, humidity is high (in comparison to countries further from the Equator), but completely sunny days abound. In cooler places such as Northern Tasmania, Australia, high humidity is experienced all year due to the ocean between mainland Australia and Tasmania. In the summer the hot dry air is absorbed by this ocean and the temperature rarely climbs above 35 °C (95 °F).

Global climate

See also: Greenhouse effectHumidity affects the energy budget and thereby influences temperatures in two major ways. First, water vapor in the atmosphere contains "latent" energy. During transpiration or evaporation, this latent heat is removed from surface liquid, cooling the Earth's surface. This is the biggest non-radiative cooling effect at the surface. It compensates for roughly 70% of the average net radiative warming at the surface.

Second, water vapor is the most abundant of all greenhouse gases. Water vapor, like a green lens that allows green light to pass through it but absorbs red light, is a "selective absorber". Like the other greenhouse gasses, water vapor is transparent to most solar energy. However, it absorbs the infrared energy emitted (radiated) upward by the Earth's surface, which is the reason that humid areas experience very little nocturnal cooling but dry desert regions cool considerably at night. This selective absorption causes the greenhouse effect. It raises the surface temperature substantially above its theoretical radiative equilibrium temperature with the sun, and water vapor is the cause of more of this warming than any other greenhouse gas.

Unlike most other greenhouse gases, however, water is not merely below its boiling point in all regions of the Earth, but below its freezing point at many altitudes. As a condensible greenhouse gas, it precipitates, with a much lower scale height and shorter atmospheric lifetime — weeks instead of decades. Without other greenhouse gases, Earth's blackbody temperature, below the freezing point of water, would cause water vapor to be removed from the atmosphere. Water vapor is thus a "slave" to the non-condensible greenhouse gases.

Animal and plant life

Humidity is one of the fundamental abiotic factors that defines any habitat (the tundra, wetlands, and the desert are a few examples), and is a determinant of which animals and plants can thrive in a given environment.

The human body dissipates heat through perspiration and its evaporation. Heat convection, to the surrounding air, and thermal radiation are the primary modes of heat transport from the body. Under conditions of high humidity, the rate of evaporation of sweat from the skin decreases. Also, if the atmosphere is as warm or warmer than the skin during times of high humidity, blood brought to the body surface cannot dissipate heat by conduction to the air. With so much blood going to the external surface of the body, less goes to the active muscles, the brain, and other internal organs. Physical strength declines, and fatigue occurs sooner than it would otherwise. Alertness and mental capacity also may be affected, resulting in heat stroke or hyperthermia.

Domesticated plants and animals (e.g. lizards) require regular upkeep of humidity percent when grown in-home and container conditions, for optimal thriving environment.

Human comfort

Although humidity is an important factor for thermal comfort, humans are more sensitive to variations in temperature than they are to changes in relative humidity. Humidity has a small effect on thermal comfort outdoors when air temperatures are low, a slightly more pronounced effect at moderate air temperatures, and a much stronger influence at higher air temperatures.

Humans are sensitive to humid air because the human body uses evaporative cooling as the primary mechanism to regulate temperature. Under humid conditions, the rate at which perspiration evaporates on the skin is lower than it would be under arid conditions. Because humans perceive the rate of heat transfer from the body rather than temperature itself, we feel warmer when the relative humidity is high than when it is low.

Humans can be comfortable within a wide range of humidities depending on the temperature—from 30 to 70%—but ideally not above the Absolute (60 °F Dew Point), between 40% and 60%. In general, higher temperatures will require lower humidities to achieve thermal comfort compared to lower temperatures, with all other factors held constant. For example, with clothing level = 1, metabolic rate = 1.1, and air speed 0.1 m/s, a change in air temperature and mean radiant temperature from 20 °C to 24 °C would lower the maximum acceptable relative humidity from 100% to 65% to maintain thermal comfort conditions. The CBE Thermal Comfort Tool can be used to demonstrate the effect of relative humidity for specific thermal comfort conditions and it can be used to demonstrate compliance with ASHRAE Standard 55–2017.

Some people experience difficulty breathing in humid environments. Some cases may possibly be related to respiratory conditions such as asthma, while others may be the product of anxiety. Affected people will often hyperventilate in response, causing sensations of numbness, faintness, and loss of concentration, among others.

Very low humidity can create discomfort, respiratory problems, and aggravate allergies in some individuals. Low humidity causes tissue lining nasal passages to dry, crack and become more susceptible to penetration of rhinovirus cold viruses. Extremely low (below 20 %) relative humidities may also cause eye irritation. The use of a humidifier in homes, especially bedrooms, can help with these symptoms. Indoor relative humidities should be kept above 30% to reduce the likelihood of the occupant's nasal passages drying out, especially in winter.

Air conditioning reduces discomfort by reducing not just temperature but humidity as well. Heating cold outdoor air can decrease relative humidity levels indoors to below 30%. According to ASHRAE Standard 55-2017: Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy, indoor thermal comfort can be achieved through the PMV method with relative humidities ranging from 0% to 100%, depending on the levels of the other factors contributing to thermal comfort. However, the recommended range of indoor relative humidity in air conditioned buildings is generally 30–60%.

Human health

Higher humidity reduces the infectivity of aerosolized influenza virus. A study concluded, "Maintaining indoor relative humidity >40% will significantly reduce the infectivity of aerosolized virus."

Excess moisture in buildings expose occupants to fungal spores, cell fragments, or mycotoxins. Infants in homes with mold have a much greater risk of developing asthma and allergic rhinitis. More than half of adult workers in moldy/humid buildings develop nasal or sinus symptoms due to mold exposure.

Mucociliary clearance in the respiratory tract is also hindered by low humidity. One study in dogs found that mucus transport was lower at an absolute humidity of 9 g/m than at 30 g/m.

Increased humidity can also lead to changes in total body water that usually leads to moderate weight gain, especially if one is acclimated to working or exercising in hot and humid weather.

Building construction

Common construction methods often produce building enclosures with a poor thermal boundary, requiring an insulation and air barrier system designed to retain indoor environmental conditions while resisting external environmental conditions. The energy-efficient, heavily sealed architecture introduced in the 20th century also sealed off the movement of moisture, and this has resulted in a secondary problem of condensation forming in and around walls, which encourages the development of mold and mildew. Additionally, buildings with foundations not properly sealed will allow water to flow through the walls due to capillary action of pores found in masonry products. Solutions for energy-efficient buildings that avoid condensation are a current topic of architecture.

For climate control in buildings using HVAC systems, the key is to maintain the relative humidity at a comfortable range—low enough to be comfortable but high enough to avoid problems associated with very dry air.

When the temperature is high and the relative humidity is low, evaporation of water is rapid; soil dries, wet clothes hung on a line or rack dry quickly, and perspiration readily evaporates from the skin. Wooden furniture can shrink, causing the paint that covers these surfaces to fracture.

When the temperature is low and the relative humidity is high, evaporation of water is slow. When relative humidity approaches 100%, condensation can occur on surfaces, leading to problems with mold, corrosion, decay, and other moisture-related deterioration. Condensation can pose a safety risk as it can promote the growth of mold and wood rot as well as possibly freezing emergency exits shut.

Certain production and technical processes and treatments in factories, laboratories, hospitals, and other facilities require specific relative humidity levels to be maintained using humidifiers, dehumidifiers and associated control systems.

Vehicles

The basic principles for buildings, above, also apply to vehicles. In addition, there may be safety considerations. For instance, high humidity inside a vehicle can lead to problems of condensation, such as misting of windshields and shorting of electrical components. In vehicles and pressure vessels such as pressurized airliners, submersibles and spacecraft, these considerations may be critical to safety, and complex environmental control systems including equipment to maintain pressure are needed.

Aviation

Airliners operate with low internal relative humidity, often under 20%, especially on long flights. The low humidity is a consequence of drawing in the very cold air with a low absolute humidity, which is found at airliner cruising altitudes. Subsequent warming of this air lowers its relative humidity. This causes discomfort such as sore eyes, dry skin, and drying out of mucosa, but humidifiers are not employed to raise it to comfortable mid-range levels because the volume of water required to be carried on board can be a significant weight penalty. As airliners descend from colder altitudes into warmer air, perhaps even flying through clouds a few thousand feet above the ground, the ambient relative humidity can increase dramatically.

Some of this moist air is usually drawn into the pressurized aircraft cabin and into other non-pressurized areas of the aircraft and condenses on the cold aircraft skin. Liquid water can usually be seen running along the aircraft skin, both on the inside and outside of the cabin. Because of the drastic changes in relative humidity inside the vehicle, components must be qualified to operate in those environments. The recommended environmental qualifications for most commercial aircraft components is listed in RTCA DO-160.

Cold, humid air can promote the formation of ice, which is a danger to aircraft as it affects the wing profile and increases weight. Naturally aspirated internal combustion engines have a further danger of ice forming inside the carburetor. Aviation weather reports (METARs) therefore include an indication of relative humidity, usually in the form of the dew point.

Pilots must take humidity into account when calculating takeoff distances, because high humidity requires longer runways and will decrease climb performance.

Density altitude is the altitude relative to the standard atmosphere conditions (International Standard Atmosphere) at which the air density would be equal to the indicated air density at the place of observation, or, in other words, the height when measured in terms of the density of the air rather than the distance from the ground. "Density Altitude" is the pressure altitude adjusted for non-standard temperature.

An increase in temperature, and, to a much lesser degree, humidity, will cause an increase in density altitude. Thus, in hot and humid conditions, the density altitude at a particular location may be significantly higher than the true altitude.

Electronics

Electronic devices are often rated to operate only under certain humidity conditions (e.g., 10% to 90%). The optimal humidity for electronic devices is 30% to 65%. At the top end of the range, moisture may increase the conductivity of permeable insulators leading to malfunction. Too low humidity may make materials brittle. A particular danger to electronic items, regardless of the stated operating humidity range, is condensation. When an electronic item is moved from a cold place (e.g., garage, car, shed, air conditioned space in the tropics) to a warm humid place (house, outside tropics), condensation may coat circuit boards and other insulators, leading to short circuit inside the equipment. Such short circuits may cause substantial permanent damage if the equipment is powered on before the condensation has evaporated. A similar condensation effect can often be observed when a person wearing glasses comes in from the cold (i.e. the glasses become foggy).

It is advisable to allow electronic equipment to acclimatise for several hours, after being brought in from the cold, before powering on. Some electronic devices can detect such a change and indicate, when plugged in and usually with a small droplet symbol, that they cannot be used until the risk from condensation has passed. In situations where time is critical, increasing air flow through the device's internals, such as removing the side panel from a PC case and directing a fan to blow into the case, will reduce significantly the time needed to acclimatise to the new environment.

In contrast, a very low humidity level favors the build-up of static electricity, which may result in spontaneous shutdown of computers when discharges occur. Apart from spurious erratic function, electrostatic discharges can cause dielectric breakdown in solid-state devices, resulting in irreversible damage. Data centers often monitor relative humidity levels for these reasons.

Industry

High humidity can often have a negative effect on the capacity of chemical plants and refineries that use furnaces as part of a certain processes (e.g., steam reforming, wet sulfuric acid processes). For example, because humidity reduces ambient oxygen concentrations (dry air is typically 20.9% oxygen, but at 100% relative humidity the air is 20.4% oxygen), flue gas fans must intake air at a higher rate than would otherwise be required to maintain the same firing rate.

Baking

High humidity in the oven, represented by an elevated wet-bulb temperature, increases the thermal conductivity of the air around the baked item, leading to a quicker baking process or even burning. Conversely, low humidity slows the baking process down.

Other important facts

At 100% relative humidity, air is saturated and at its dew point: the water vapor pressure would permit neither evaporation of nearby liquid water nor condensation to grow the nearby water; neither sublimation of nearby ice nor deposition to grow the nearby ice.

Relative humidity can exceed 100%, in which case the air is supersaturated. Cloud formation requires supersaturated air. Cloud condensation nuclei lower the level of supersaturation required to form fogs and clouds – in the absence of nuclei around which droplets or ice can form, a higher level of supersaturation is required for these droplets or ice crystals to form spontaneously. In the Wilson cloud chamber, which is used in nuclear physics experiments, a state of supersaturation is created within the chamber, and moving subatomic particles act as condensation nuclei so trails of fog show the paths of those particles.

For a given dew point and its corresponding absolute humidity, the relative humidity will change inversely, albeit nonlinearly, with the temperature. This is because the vapor pressure of water increases with temperature—the operative principle behind everything from hair dryers to dehumidifiers.

Due to the increasing potential for a higher water vapor partial pressure at higher air temperatures, the water content of air at sea level can get as high as 3% by mass at 30 °C (86 °F) compared to no more than about 0.5% by mass at 0 °C (32 °F). This explains the low levels (in the absence of measures to add moisture) of humidity in heated structures during winter, resulting in dry skin, itchy eyes, and persistence of static electric charges. Even with saturation (100% relative humidity) outdoors, heating of infiltrated outside air that comes indoors raises its moisture capacity, which lowers relative humidity and increases evaporation rates from moist surfaces indoors, including human bodies and household plants.

Similarly, during summer in humid climates a great deal of liquid water condenses from air cooled in air conditioners. Warmer air is cooled below its dew point, and the excess water vapor condenses. This phenomenon is the same as that which causes water droplets to form on the outside of a cup containing an ice-cold drink.

A useful rule of thumb is that the maximum absolute humidity doubles for every 20 °F (11 °C) increase in temperature. Thus, the relative humidity will drop by a factor of 2 for each 20 °F (11 °C) increase in temperature, assuming conservation of absolute moisture. For example, in the range of normal temperatures, air at 68 °F (20 °C) and 50% relative humidity will become saturated if cooled to 50 °F (10 °C), its dew point, and 41 °F (5 °C) air at 80% relative humidity warmed to 68 °F (20 °C) will have a relative humidity of only 29% and feel dry. By comparison, thermal comfort standard ASHRAE 55 requires systems designed to control humidity to maintain a dew point of 16.8 °C (62.2 °F) though no lower humidity limit is established.

Water vapor is a lighter gas than other gaseous components of air at the same temperature, so humid air will tend to rise by natural convection. This is a mechanism behind thunderstorms and other weather phenomena. Relative humidity is often mentioned in weather forecasts and reports, as it is an indicator of the likelihood of dew, or fog. In hot summer weather, it also increases the apparent temperature to humans (and other animals) by hindering the evaporation of perspiration from the skin as the relative humidity rises. This effect is calculated as the heat index or humidex.

A device used to measure humidity is called a hygrometer; one used to regulate it is called a humidistat, or sometimes hygrostat. These are analogous to a thermometer and thermostat for temperature, respectively.

The field concerned with the study of physical and thermodynamic properties of gas–vapor mixtures is named psychrometrics.

Relationship between absolute humidity, relative humidity, and temperature

| Temperature | Relative humidity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% | |

| 50 °C (122 °F) | 0 (0) | 8.3 (0.22) | 16.6 (0.45) | 24.9 (0.67) | 33.2 (0.90) | 41.5 (1.12) | 49.8 (1.34) | 58.1 (1.57) | 66.4 (1.79) | 74.7 (2.01) | 83.0 (2.24) |

| 45 °C (113 °F) | 0 (0) | 6.5 (0.18) | 13.1 (0.35) | 19.6 (0.53) | 26.2 (0.71) | 32.7 (0.88) | 39.3 (1.06) | 45.8 (1.24) | 52.4 (1.41) | 58.9 (1.59) | 65.4 (1.76) |

| 40 °C (104 °F) | 0 (0) | 5.1 (0.14) | 10.2 (0.28) | 15.3 (0.41) | 20.5 (0.55) | 25.6 (0.69) | 30.7 (0.83) | 35.8 (0.97) | 40.9 (1.10) | 46.0 (1.24) | 51.1 (1.38) |

| 35 °C (95 °F) | 0 (0) | 4.0 (0.11) | 7.9 (0.21) | 11.9 (0.32) | 15.8 (0.43) | 19.8 (0.53) | 23.8 (0.64) | 27.7 (0.75) | 31.7 (0.85) | 35.6 (0.96) | 39.6 (1.07) |

| 30 °C (86 °F) | 0 (0) | 3.0 (0.081) | 6.1 (0.16) | 9.1 (0.25) | 12.1 (0.33) | 15.2 (0.41) | 18.2 (0.49) | 21.3 (0.57) | 24.3 (0.66) | 27.3 (0.74) | 30.4 (0.82) |

| 25 °C (77 °F) | 0 (0) | 2.3 (0.062) | 4.6 (0.12) | 6.9 (0.19) | 9.2 (0.25) | 11.5 (0.31) | 13.8 (0.37) | 16.1 (0.43) | 18.4 (0.50) | 20.7 (0.56) | 23.0 (0.62) |

| 20 °C (68 °F) | 0 (0) | 1.7 (0.046) | 3.5 (0.094) | 5.2 (0.14) | 6.9 (0.19) | 8.7 (0.23) | 10.4 (0.28) | 12.1 (0.33) | 13.8 (0.37) | 15.6 (0.42) | 17.3 (0.47) |

| 15 °C (59 °F) | 0 (0) | 1.3 (0.035) | 2.6 (0.070) | 3.9 (0.11) | 5.1 (0.14) | 6.4 (0.17) | 7.7 (0.21) | 9.0 (0.24) | 10.3 (0.28) | 11.5 (0.31) | 12.8 (0.35) |

| 10 °C (50 °F) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (0.024) | 1.9 (0.051) | 2.8 (0.076) | 3.8 (0.10) | 4.7 (0.13) | 5.6 (0.15) | 6.6 (0.18) | 7.5 (0.20) | 8.5 (0.23) | 9.4 (0.25) |

| 5 °C (41 °F) | 0 (0) | 0.7 (0.019) | 1.4 (0.038) | 2.0 (0.054) | 2.7 (0.073) | 3.4 (0.092) | 4.1 (0.11) | 4.8 (0.13) | 5.4 (0.15) | 6.1 (0.16) | 6.8 (0.18) |

| 0 °C (32 °F) | 0 (0) | 0.5 (0.013) | 1.0 (0.027) | 1.5 (0.040) | 1.9 (0.051) | 2.4 (0.065) | 2.9 (0.078) | 3.4 (0.092) | 3.9 (0.11) | 4.4 (0.12) | 4.8 (0.13) |

| −5 °C (23 °F) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (0.0081) | 0.7 (0.019) | 1.0 (0.027) | 1.4 (0.038) | 1.7 (0.046) | 2.1 (0.057) | 2.4 (0.065) | 2.7 (0.073) | 3.1 (0.084) | 3.4 (0.092) |

| −10 °C (14 °F) | 0 (0) | 0.2 (0.0054) | 0.5 (0.013) | 0.7 (0.019) | 0.9 (0.024) | 1.2 (0.032) | 1.4 (0.038) | 1.6 (0.043) | 1.9 (0.051) | 2.1 (0.057) | 2.3 (0.062) |

| −15 °C (5 °F) | 0 (0) | 0.2 (0.0054) | 0.3 (0.0081) | 0.5 (0.013) | 0.6 (0.016) | 0.8 (0.022) | 1.0 (0.027) | 1.1 (0.030) | 1.3 (0.035) | 1.5 (0.040) | 1.6 (0.043) |

| −20 °C (−4 °F) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0.0027) | 0.2 (0.0054) | 0.3 (0.0081) | 0.4 (0.011) | 0.4 (0.011) | 0.5 (0.013) | 0.6 (0.016) | 0.7 (0.019) | 0.8 (0.022) | 0.9 (0.024) |

| −25 °C (−13 °F) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0.0027) | 0.1 (0.0027) | 0.2 (0.0054) | 0.2 (0.0054) | 0.3 (0.0081) | 0.3 (0.0081) | 0.4 (0.011) | 0.4 (0.011) | 0.5 (0.013) | 0.6 (0.016) |

References

Citations

- Brun, Philipp; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; Hari, Chantal; Pellissier, Loïc; Karger, Dirk N. (2022-06-27). "Global climate-related predictors at kilometre resolution for the past and future" (PDF). ESSD – Land/Biogeosciences and biodiversity. doi:10.5194/essd-2022-212. Archived (PDF) from the original on Jan 8, 2023.

- "What is water vapor?". WeatherQuestions.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-11. Retrieved 2012-08-28.

- Wyer, Samuel S. (1906). "Fundamental Physical Laws and Definitions". A Treatise on Producer-Gas and Gas-Producers. McGraw-Hill Book Company. p. 23.

- Perry, R.H. and Green, D.W, (2007) Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (8th Edition), Section 12, Psychrometry, Evaporative Cooling and Solids Drying McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-151135-3

- ^ Babin, Steven M. (1998). "Relative Humidity & Saturation Vapor Pressure: A Brief Tutorial". Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Archived from the original on 1998-07-13. Retrieved 2022-11-28. (Alternate title: "Water Vapor Myths: A Brief Tutorial".)

- Fraser, Alistair B. "Bad Clouds FAQ". Penn State College of Earth and Mineral Sciences. Archived from the original on 2006-06-17.

- "Antarctic Air Visits Paranal". ESO Picture of the Week. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Climate – Humidity indexes". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Climate/humidity table". Transport Information Service of the German Insurance Association. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- British Standard BS 1339 (revised), Humidity and Dewpoint, Parts 1–3 (2002–2007)

- Perry, R. H. and Green, D. W, Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (8th Edition), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-142294-3, pp. 12–14

- Lide, David (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (85 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 15–25. ISBN 0-8493-0485-7.

- Rothfusz, Lans P. (1 July 1990). "The Heat Index 'Equation' (or, More Than You Ever Wanted to Know About Heat Index)" (PDF). Scientific Services Division (NWS Southern Region Headquarters). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-01. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- Steadman, R. G. (1979). "The Assessment of Sultriness. Part I: A Temperature-Humidity Index Based on Human Physiology and Clothing Science". Journal of Applied Meteorology. 18 (7): 861–873. Bibcode:1979JApMe..18..861S. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1979)018<0861:TAOSPI>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0021-8952.

- Seidel, Dian. "What is atmospheric humidity and how is it measured?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Vapor-Liquid/Solid System, 201 Class Page". University of Arizona. Archived from the original on May 8, 2006.

- ^ Buck 1981, pp. 1527–1532.

- Pieter R. Wiederhold. 1997. Water Vapor Measurement, Methods and Instrumentation. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY ISBN 9780824793197

- "BS1339" Part 3

- Isaac Newton (1704). Opticks. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-60205-9.

- "Weather History for Sukkur, Pakistan – Weather Underground". Archived from the original on 2017-09-15. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- "Blackbody Radiation". Archived from the original on 2020-08-14. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- "Lecture notes". Archived from the original on 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- "Radiative Balance, Earth's Temperature, and Greenhouse Gases (lecture notes)". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- Alley, R. (2014). "GEOSC 10 Optional Enrichment Article 1". Archived from the original on 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- Businger, S. "Lecture 28: Future Global Warming Modeling Climate Change" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-30.

- Schwieterman, E. "Comparing the Greenhouse Effect on Earth, Mars, Venus, and Titan: Present Day and through Time" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2010. Abiotic factor. Encyclopedia of Earth. eds Emily Monosson and C. Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment Archived June 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Washington DC

- Fanger 1970, p. 48.

- Bröde et al. 2011, pp. 481–494.

- Gilmore 1972, p. 99.

- Archived 2021-02-10 at the Wayback Machine ASHRAE Std 62.1-2019

- "Winter Indoor Comfort and Relative Humidity", Information please (database), Pearson, 2007, archived from the original on 2013-04-27, retrieved 2013-05-01,

... by increasing the relative humidity to above 50% within the above temperature range, 80% or more of all average dressed persons would feel comfortable.

- "Recommended relative humidity level", The engineering toolbox, archived from the original on 2013-05-11, retrieved 2013-05-01,

Relative humidity above 60% feels uncomfortable wet. Human comfort requires the relative humidity to be in the range 25–60% RH.

- Schiavon, Hoyt & Piccioli 2013, pp. 321–334.

- "Heat and humidity – the lung association". www.lung.ca. 26 August 2014. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "What causes the common cold?". University of Rochester Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2016-02-04. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- ^ Arundel et al. 1986, pp. 351–361.

- "Indoor air quality testing". Archived from the original on 2017-09-21.

- "Nosebleeds". WebMD Medical Reference. Archived from the original on 2015-11-10. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- "Indoor Air Quality" (PDF). NH DHHS, Division of Public Health Services. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-22. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- "School Indoor Air Quality: Best Management Practices Manual" (PDF). Washington State Department of Health. November 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-01-20. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- "Optimum Humidity Levels for Home". AirBetter.org. 3 August 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ ASHRAE Standard 55 (2017). "Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy".

- Wolkoff & Kjaergaard 2007, pp. 850–857.

- ASHRAE Standard 160 (2016). "Criteria for Moisture-Control Design Analysis in Buildings"

- Noti, John D.; Blachere, Francoise M.; McMillen, Cynthia M.; Lindsley, William G.; Kashon, Michael L.; Slaughter, Denzil R.; Beezhold, Donald H. (2013). "High Humidity Leads to Loss of Infectious Influenza Virus from Simulated Coughs". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e57485. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...857485N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057485. PMC 3583861. PMID 23460865.

- ^ Park J, Cox-Ganser JM (2011). "Meta-Mold exposure and respiratory health in damp indoor environments". Frontiers in Bioscience. 3 (2): 757–771. doi:10.2741/e284. PMID 21196349.

- Pieterse, A; Hanekom, SD (2018). "Criteria for enhancing mucus transport: a systematic scoping review". Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine. 13: 22. doi:10.1186/s40248-018-0127-6. PMC 6034335. PMID 29988934.

- "To what degree is a person's body weight affected by the ambient temperature and humidity? Do we conserve or release water as the climate changes?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-09.

- "Free publications". Archived from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- "Airplane Humidity". Aviator Atlas. 5 April 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Fogging Glasses". Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2012-08-08.

- "Everything You Need to Know About Combustion Chemistry & Analysis – Industrial Controls". Archived from the original on 2020-01-10. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- "Why is humidity important in cooking?". Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- "Climate/humidity table". Transport Informations Service. German Insurance Association. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- "Absolute Humidity Table" (PDF). mercury.pr.erau.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

General sources

- Arundel, A. V.; Sterling, E. M.; Biggin, J. H.; Sterling, T. D. (1986). "Indirect health effects of relative humidity in indoor environments". Environ. Health Perspect. 65: 351–61. doi:10.1289/ehp.8665351. PMC 1474709. PMID 3709462.

- Bröde, Peter; Fiala, Dusan; Błażejczyk, Krzysztof; Holmér, Ingvar; Jendritzky, Gerd; Kampmann, Bernhard; Tinz, Birger; Havenith, George (2011-05-31). "Deriving the operational procedure for the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI)" (PDF). International Journal of Biometeorology. 56 (3): 481–494. doi:10.1007/s00484-011-0454-1. ISSN 0020-7128. PMID 21626294. S2CID 37771005.

- Buck, Arden L. (1981). "New Equations for Computing Vapor Pressure and Enhancement Factor". Journal of Applied Meteorology. 20 (12): 1527–1532. Bibcode:1981JApMe..20.1527B. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1981)020<1527:NEFCVP>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0021-8952.

- Fanger, P. O. (1970). Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Applications in Environmental Engineering. Danish Technical Press. ISBN 978-87-571-0341-0.

- Gilmore, C. P. (September 1972). "More Comfort for Your Heating Dollar". Popular Science. p. 99.

- Schiavon, Stefano; Hoyt, Tyler; Piccioli, Alberto (2013-12-27). "Web application for thermal comfort visualization and calculation according to ASHRAE Standard 55". Building Simulation. 7 (4): 321–334. doi:10.1007/s12273-013-0162-3. ISSN 1996-3599. S2CID 56274353. Archived from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- Wolkoff, Peder; Kjaergaard, Søren K. (August 2007). "The dichotomy of relative humidity on indoor air quality". Environment International. 33 (6): 850–857. Bibcode:2007EnInt..33..850W. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2007.04.004. ISSN 0160-4120. PMID 17499853.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, "IAQ in Large Buildings" Archived 2005-10-31 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved Jan. 9, 2006.

Further reading

- Himmelblau, David M. (1989). Basic Principles And Calculations In Chemical Engineering. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-066572-X.

- Lide, David (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (85 ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9780849304859.

- Perry, R.H.; Green, D.W (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049841-5.

External links

| Meteorological data and variables | |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Condensation | |

| Convection |

|

| Temperature |

|

| Pressure | |

| Velocity | |

| Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning | |

|---|---|

| Fundamental concepts |

|

| Technology |

|

| Components |

|

| Measurement and control |

|

| Professions, trades, and services |

|

| Industry organizations | |

| Health and safety |

|

| See also | |

, divided by the volume of the air and water vapor mixture

, divided by the volume of the air and water vapor mixture  , which can be expressed as:

, which can be expressed as:

In the equation above, if the volume is not set, the absolute humidity varies with changes in air temperature or pressure. Because of this variability, use of the term absolute humidity as defined is inappropriate for computations in chemical engineering, such as drying, where temperature variations might be significant. As a result, absolute humidity in chemical engineering may refer to mass of water vapor per unit mass of dry air, also known as the humidity ratio or mass mixing ratio (see "specific humidity" below), which is better suited for heat and mass balance calculations. Mass of water per unit volume as in the equation above is also defined as volumetric humidity. Because of the potential confusion,

In the equation above, if the volume is not set, the absolute humidity varies with changes in air temperature or pressure. Because of this variability, use of the term absolute humidity as defined is inappropriate for computations in chemical engineering, such as drying, where temperature variations might be significant. As a result, absolute humidity in chemical engineering may refer to mass of water vapor per unit mass of dry air, also known as the humidity ratio or mass mixing ratio (see "specific humidity" below), which is better suited for heat and mass balance calculations. Mass of water per unit volume as in the equation above is also defined as volumetric humidity. Because of the potential confusion,  or

or  ) of an air-water mixture is defined as the ratio of the

) of an air-water mixture is defined as the ratio of the  ) in air to the

) in air to the  ) of water at the same temperature, usually expressed as a percentage:

) of water at the same temperature, usually expressed as a percentage:

where

where  is the dry-bulb temperature expressed in degrees Celsius (°C),

is the dry-bulb temperature expressed in degrees Celsius (°C),  is the absolute pressure expressed in millibars, and

is the absolute pressure expressed in millibars, and  is the equilibrium vapor pressure expressed in millibars. Buck has reported that the maximal relative error is less than 0.20% between −20 and +50 °C (−4 and 122 °F) when this particular form of the generalized formula is used to estimate the equilibrium vapor pressure of water.

is the equilibrium vapor pressure expressed in millibars. Buck has reported that the maximal relative error is less than 0.20% between −20 and +50 °C (−4 and 122 °F) when this particular form of the generalized formula is used to estimate the equilibrium vapor pressure of water.

is defined as the ratio of the saturated vapor pressure of water in moist air

is defined as the ratio of the saturated vapor pressure of water in moist air  to the saturated vapor pressure of pure water:

to the saturated vapor pressure of pure water: