For the graphical concept, see Line (graphics). For other uses, see Line.

| Geometry | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Projecting a sphere to a plane Projecting a sphere to a plane | ||||||||||

| Branches | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Zero-dimensional | ||||||||||

| One-dimensional | ||||||||||

Two-dimensional

|

||||||||||

| Three-dimensional | ||||||||||

| Four- / other-dimensional | ||||||||||

| Geometers | ||||||||||

by name

|

||||||||||

by period

|

||||||||||

In geometry, a straight line, usually abbreviated line, is an infinitely long object with no width, depth, or curvature, an idealization of such physical objects as a straightedge, a taut string, or a ray of light. Lines are spaces of dimension one, which may be embedded in spaces of dimension two, three, or higher. The word line may also refer, in everyday life, to a line segment, which is a part of a line delimited by two points (its endpoints).

Euclid's Elements defines a straight line as a "breadthless length" that "lies evenly with respect to the points on itself", and introduced several postulates as basic unprovable properties on which the rest of geometry was established. Euclidean line and Euclidean geometry are terms introduced to avoid confusion with generalizations introduced since the end of the 19th century, such as non-Euclidean, projective, and affine geometry.

Properties

In the Greek deductive geometry of Euclid's Elements, a general line (now called a curve) is defined as a "breadthless length", and a straight line (now called a line segment) was defined as a line "which lies evenly with the points on itself". These definitions appeal to readers' physical experience, relying on terms that are not themselves defined, and the definitions are never explicitly referenced in the remainder of the text. In modern geometry, a line is usually either taken as a primitive notion with properties given by axioms, or else defined as a set of points obeying a linear relationship, for instance when real numbers are taken to be primitive and geometry is established analytically in terms of numerical coordinates.

In an axiomatic formulation of Euclidean geometry, such as that of Hilbert (modern mathematicians added to Euclid's original axioms to fill perceived logical gaps), a line is stated to have certain properties that relate it to other lines and points. For example, for any two distinct points, there is a unique line containing them, and any two distinct lines intersect at most at one point. In two dimensions (i.e., the Euclidean plane), two lines that do not intersect are called parallel. In higher dimensions, two lines that do not intersect are parallel if they are contained in a plane, or skew if they are not.

On a Euclidean plane, a line can be represented as a boundary between two regions. Any collection of finitely many lines partitions the plane into convex polygons (possibly unbounded); this partition is known as an arrangement of lines.

In higher dimensions

In three-dimensional space, a first degree equation in the variables x, y, and z defines a plane, so two such equations, provided the planes they give rise to are not parallel, define a line which is the intersection of the planes. More generally, in n-dimensional space n−1 first-degree equations in the n coordinate variables define a line under suitable conditions.

In more general Euclidean space, R (and analogously in every other affine space), the line L passing through two different points a and b is the subset The direction of the line is from a reference point a (t = 0) to another point b (t = 1), or in other words, in the direction of the vector b − a. Different choices of a and b can yield the same line.

Collinear points

Main article: CollinearityThree or more points are said to be collinear if they lie on the same line. If three points are not collinear, there is exactly one plane that contains them.

In affine coordinates, in n-dimensional space the points X = (x1, x2, ..., xn), Y = (y1, y2, ..., yn), and Z = (z1, z2, ..., zn) are collinear if the matrix has a rank less than 3. In particular, for three points in the plane (n = 2), the above matrix is square and the points are collinear if and only if its determinant is zero.

Equivalently for three points in a plane, the points are collinear if and only if the slope between one pair of points equals the slope between any other pair of points (in which case the slope between the remaining pair of points will equal the other slopes). By extension, k points in a plane are collinear if and only if any (k–1) pairs of points have the same pairwise slopes.

In Euclidean geometry, the Euclidean distance d(a,b) between two points a and b may be used to express the collinearity between three points by:

- The points a, b and c are collinear if and only if d(x,a) = d(c,a) and d(x,b) = d(c,b) implies x = c.

However, there are other notions of distance (such as the Manhattan distance) for which this property is not true.

In the geometries where the concept of a line is a primitive notion, as may be the case in some synthetic geometries, other methods of determining collinearity are needed.

Types

In a sense, all lines in Euclidean geometry are equal, in that, without coordinates, one can not tell them apart from one another. However, lines may play special roles with respect to other objects in the geometry and be divided into types according to that relationship. For instance, with respect to a conic (a circle, ellipse, parabola, or hyperbola), lines can be:

- tangent lines, which touch the conic at a single point;

- secant lines, which intersect the conic at two points and pass through its interior;

- exterior lines, which do not meet the conic at any point of the Euclidean plane; or

- a directrix, whose distance from a point helps to establish whether the point is on the conic.

- a coordinate line, a linear coordinate dimension

In the context of determining parallelism in Euclidean geometry, a transversal is a line that intersects two other lines that may or not be parallel to each other.

For more general algebraic curves, lines could also be:

- i-secant lines, meeting the curve in i points counted without multiplicity, or

- asymptotes, which a curve approaches arbitrarily closely without touching it.

With respect to triangles we have:

- the Euler line,

- the Simson lines, and

- central lines.

For a convex quadrilateral with at most two parallel sides, the Newton line is the line that connects the midpoints of the two diagonals.

For a hexagon with vertices lying on a conic we have the Pascal line and, in the special case where the conic is a pair of lines, we have the Pappus line.

Parallel lines are lines in the same plane that never cross. Intersecting lines share a single point in common. Coincidental lines coincide with each other—every point that is on either one of them is also on the other.

Perpendicular lines are lines that intersect at right angles.

In three-dimensional space, skew lines are lines that are not in the same plane and thus do not intersect each other.

In axiomatic systems

The concept of line is often considered in geometry as a primitive notion in axiomatic systems, meaning it is not being defined by other concepts. In those situations where a line is a defined concept, as in coordinate geometry, some other fundamental ideas are taken as primitives. When the line concept is a primitive, the properties of lines are dictated by the axioms which they must satisfy.

In a non-axiomatic or simplified axiomatic treatment of geometry, the concept of a primitive notion may be too abstract to be dealt with. In this circumstance, it is possible to provide a description or mental image of a primitive notion, to give a foundation to build the notion on which would formally be based on the (unstated) axioms. Descriptions of this type may be referred to, by some authors, as definitions in this informal style of presentation. These are not true definitions, and could not be used in formal proofs of statements. The "definition" of line in Euclid's Elements falls into this category. Even in the case where a specific geometry is being considered (for example, Euclidean geometry), there is no generally accepted agreement among authors as to what an informal description of a line should be when the subject is not being treated formally.

Definition

Main article: Line coordinatesLinear equation

Main article: Linear equation

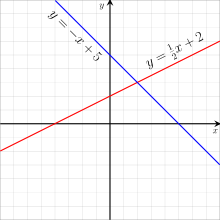

Lines in a Cartesian plane or, more generally, in affine coordinates, are characterized by linear equations. More precisely, every line (including vertical lines) is the set of all points whose coordinates (x, y) satisfy a linear equation; that is, where a, b and c are fixed real numbers (called coefficients) such that a and b are not both zero. Using this form, vertical lines correspond to equations with b = 0.

One can further suppose either c = 1 or c = 0, by dividing everything by c if it is not zero.

There are many variant ways to write the equation of a line which can all be converted from one to another by algebraic manipulation. The above form is sometimes called the standard form. If the constant term is put on the left, the equation becomes and this is sometimes called the general form of the equation. However, this terminology is not universally accepted, and many authors do not distinguish these two forms.

These forms are generally named by the type of information (data) about the line that is needed to write down the form. Some of the important data of a line is its slope, x-intercept, known points on the line and y-intercept.

The equation of the line passing through two different points and may be written as If x0 ≠ x1, this equation may be rewritten as or In two dimensions, the equation for non-vertical lines is often given in the slope–intercept form:

where:

- m is the slope or gradient of the line.

- b is the y-intercept of the line.

- x is the independent variable of the function y = f(x).

The slope of the line through points and , when , is given by and the equation of this line can be written .

As a note, lines in three dimensions may also be described as the simultaneous solutions of two linear equations such that and are not proportional (the relations imply ). This follows since in three dimensions a single linear equation typically describes a plane and a line is what is common to two distinct intersecting planes.

Parametric equation

Further information: Parametric equationParametric equations are also used to specify lines, particularly in those in three dimensions or more because in more than two dimensions lines cannot be described by a single linear equation.

In three dimensions lines are frequently described by parametric equations: where:

- x, y, and z are all functions of the independent variable t which ranges over the real numbers.

- (x0, y0, z0) is any point on the line.

- a, b, and c are related to the slope of the line, such that the direction vector (a, b, c) is parallel to the line.

Parametric equations for lines in higher dimensions are similar in that they are based on the specification of one point on the line and a direction vector.

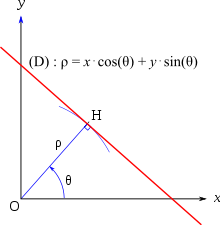

Hesse normal form

Main article: Hesse normal form

The normal form (also called the Hesse normal form, after the German mathematician Ludwig Otto Hesse), is based on the normal segment for a given line, which is defined to be the line segment drawn from the origin perpendicular to the line. This segment joins the origin with the closest point on the line to the origin. The normal form of the equation of a straight line on the plane is given by: where is the angle of inclination of the normal segment (the oriented angle from the unit vector of the x-axis to this segment), and p is the (positive) length of the normal segment. The normal form can be derived from the standard form by dividing all of the coefficients by and also multiplying through by if

Unlike the slope-intercept and intercept forms, this form can represent any line but also requires only two finite parameters, and p, to be specified. If p > 0, then is uniquely defined modulo 2π. On the other hand, if the line is through the origin (c = p = 0), one drops the c/|c| term to compute and , and it follows that is only defined modulo π.

Other representations

Vectors

The vector equation of the line through points A and B is given by (where λ is a scalar).

If a is vector OA and b is vector OB, then the equation of the line can be written: .

A ray starting at point A is described by limiting λ. One ray is obtained if λ ≥ 0, and the opposite ray comes from λ ≤ 0.

Polar coordinates

In a Cartesian plane, polar coordinates (r, θ) are related to Cartesian coordinates by the parametric equations:

In polar coordinates, the equation of a line not passing through the origin—the point with coordinates (0, 0)—can be written with r > 0 and Here, p is the (positive) length of the line segment perpendicular to the line and delimited by the origin and the line, and is the (oriented) angle from the x-axis to this segment.

It may be useful to express the equation in terms of the angle between the x-axis and the line. In this case, the equation becomes with r > 0 and

These equations can be derived from the normal form of the line equation by setting and and then applying the angle difference identity for sine or cosine.

These equations can also be proven geometrically by applying right triangle definitions of sine and cosine to the right triangle that has a point of the line and the origin as vertices, and the line and its perpendicular through the origin as sides.

The previous forms do not apply for a line passing through the origin, but a simpler formula can be written: the polar coordinates of the points of a line passing through the origin and making an angle of with the x-axis, are the pairs such that

Generalizations of the Euclidean line

See also: Geometric spaceIn modern mathematics, given the multitude of geometries, the concept of a line is closely tied to the way the geometry is described. For instance, in analytic geometry, a line in the plane is often defined as the set of points whose coordinates satisfy a given linear equation, but in a more abstract setting, such as incidence geometry, a line may be an independent object, distinct from the set of points which lie on it.

When a geometry is described by a set of axioms, the notion of a line is usually left undefined (a so-called primitive object). The properties of lines are then determined by the axioms which refer to them. One advantage to this approach is the flexibility it gives to users of the geometry. Thus in differential geometry, a line may be interpreted as a geodesic (shortest path between points), while in some projective geometries, a line is a 2-dimensional vector space (all linear combinations of two independent vectors). This flexibility also extends beyond mathematics and, for example, permits physicists to think of the path of a light ray as being a line.

Projective geometry

Further information: Geodesic

In many models of projective geometry, the representation of a line rarely conforms to the notion of the "straight curve" as it is visualised in Euclidean geometry. In elliptic geometry we see a typical example of this. In the spherical representation of elliptic geometry, lines are represented by great circles of a sphere with diametrically opposite points identified. In a different model of elliptic geometry, lines are represented by Euclidean planes passing through the origin. Even though these representations are visually distinct, they satisfy all the properties (such as, two points determining a unique line) that make them suitable representations for lines in this geometry.

The "shortness" and "straightness" of a line, interpreted as the property that the distance along the line between any two of its points is minimized (see triangle inequality), can be generalized and leads to the concept of geodesics in metric spaces.

Extensions

Ray

"Ray (geometry)" redirects here. For other uses in mathematics, see Ray (disambiguation) § Science and mathematics.

Given a line and any point A on it, we may consider A as decomposing this line into two parts. Each such part is called a ray and the point A is called its initial point. It is also known as half-line, a one-dimensional half-space. The point A is considered to be a member of the ray. Intuitively, a ray consists of those points on a line passing through A and proceeding indefinitely, starting at A, in one direction only along the line. However, in order to use this concept of a ray in proofs a more precise definition is required.

Given distinct points A and B, they determine a unique ray with initial point A. As two points define a unique line, this ray consists of all the points between A and B (including A and B) and all the points C on the line through A and B such that B is between A and C. This is, at times, also expressed as the set of all points C on the line determined by A and B such that A is not between B and C. A point D, on the line determined by A and B but not in the ray with initial point A determined by B, will determine another ray with initial point A. With respect to the AB ray, the AD ray is called the opposite ray.

Thus, we would say that two different points, A and B, define a line and a decomposition of this line into the disjoint union of an open segment (A, B) and two rays, BC and AD (the point D is not drawn in the diagram, but is to the left of A on the line AB). These are not opposite rays since they have different initial points.

In Euclidean geometry two rays with a common endpoint form an angle.

The definition of a ray depends upon the notion of betweenness for points on a line. It follows that rays exist only for geometries for which this notion exists, typically Euclidean geometry or affine geometry over an ordered field. On the other hand, rays do not exist in projective geometry nor in a geometry over a non-ordered field, like the complex numbers or any finite field.

Line segment

Main article: Line segment

A line segment is a part of a line that is bounded by two distinct end points and contains every point on the line between its end points. Depending on how the line segment is defined, either of the two end points may or may not be part of the line segment. Two or more line segments may have some of the same relationships as lines, such as being parallel, intersecting, or skew, but unlike lines they may be none of these, if they are coplanar and either do not intersect or are collinear.

Number line

Main article: Number line

A point on number line corresponds to a real number and vice versa. Usually, integers are evenly spaced on the line, with positive numbers are on the right, negative numbers on the left. As an extension to the concept, an imaginary line representing imaginary numbers can be drawn perpendicular to the number line at zero. The two lines forms the complex plane, a geometrical representation of the set of complex numbers.

See also

- Affine transformation

- Coordinate axis

- Curve

- Distance between two parallel lines

- Distance from a point to a line

- Flat (geometry)

- Incidence (geometry)

- Line segment

- Generalised circle

- Locus

- Plane (geometry)

- Polyline

Notes

- Technically, the collineation group acts transitively on the set of lines.

- On occasion we may consider a ray without its initial point. Such rays are called open rays, in contrast to the typical ray which would be said to be closed.

References

- ^ Faber, Richard L. (1983), Foundations of Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometry, New York: Marcel Dekker, ISBN 0-8247-1748-1

- Foster, Colin (2010), Resources for teaching mathematics, 14–16, New York: Continuum International Pub. Group, ISBN 978-1-4411-3724-1, OCLC 747274805

- Padoa, Alessandro (1900), Un nouveau système de définitions pour la géométrie euclidienne (in French), International Congress of Mathematicians

- Russell, Bertrand, The Principles of Mathematics, p. 410

- Protter, Murray H.; Protter, Philip E. (1988), Calculus with Analytic Geometry, Jones & Bartlett Learning, p. 62, ISBN 9780867200935

- Nunemacher, Jeffrey (1999), "Asymptotes, Cubic Curves, and the Projective Plane", Mathematics Magazine, 72 (3): 183–192, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.502.72, doi:10.2307/2690881, JSTOR 2690881

- Alsina, Claudi; Nelsen, Roger B. (2010), Charming Proofs: A Journey Into Elegant Mathematics, MAA, pp. 108–109, ISBN 9780883853481 (online copy, p. 108, at Google Books)

- Kay, David C. (1969), College Geometry, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, p. 114, ISBN 978-0030731006, LCCN 69-12075, OCLC 47870

- Coxeter, H.S.M (1969), Introduction to Geometry (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, p. 4, ISBN 0-471-18283-4

- Bôcher, Maxime (1915), Plane Analytic Geometry: With Introductory Chapters on the Differential Calculus, H. Holt, p. 44, archived from the original on 2016-05-13

- Torrence, Bruce F.; Torrence, Eve A. (29 Jan 2009), The Student's Introduction to MATHEMATICA: A Handbook for Precalculus, Calculus, and Linear Algebra, Cambridge University Press, p. 314, ISBN 9781139473736

- Wylie Jr., C.R. (1964), Foundations of Geometry, New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 59, definition 3, ISBN 0-07-072191-2

- Pedoe, Dan (1988), Geometry: A Comprehensive Course, Mineola, NY: Dover, p. 2, ISBN 0-486-65812-0

- Sidorov, L. A. (2001) , "Angle", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- Stewart, James B.; Redlin, Lothar; Watson, Saleem (2008), College Algebra (5th ed.), Brooks Cole, pp. 13–19, ISBN 978-0-495-56521-5

- Patterson, B. C. (1941), "The inversive plane", The American Mathematical Monthly, 48 (9): 589–599, doi:10.2307/2303867, JSTOR 2303867, MR 0006034

External links

- "Line (curve)", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001

- Equations of the Straight Line at Cut-the-Knot

The

The  has a

has a  (including vertical lines) is the set of all points whose

(including vertical lines) is the set of all points whose  where a, b and c are fixed

where a, b and c are fixed  and this is sometimes called the general form of the equation. However, this terminology is not universally accepted, and many authors do not distinguish these two forms.

and this is sometimes called the general form of the equation. However, this terminology is not universally accepted, and many authors do not distinguish these two forms.

and

and  may be written as

may be written as

If x0 ≠ x1, this equation may be rewritten as

If x0 ≠ x1, this equation may be rewritten as

or

or

In

In  where:

where:

and

and  , when

, when  , is given by

, is given by  and the equation of this line can be written

and the equation of this line can be written  .

.

such that

such that  and

and  are not proportional (the relations

are not proportional (the relations  imply

imply  ). This follows since in three dimensions a single linear equation typically describes a

). This follows since in three dimensions a single linear equation typically describes a  where:

where:

where

where  is the angle of inclination of the normal segment (the oriented angle from the unit vector of the x-axis to this segment), and p is the (positive) length of the normal segment. The normal form can be derived from the standard form

is the angle of inclination of the normal segment (the oriented angle from the unit vector of the x-axis to this segment), and p is the (positive) length of the normal segment. The normal form can be derived from the standard form  by dividing all of the coefficients by

by dividing all of the coefficients by

and also multiplying through by

and also multiplying through by  if

if

and

and  , and it follows that

, and it follows that  (where λ is a

(where λ is a  .

.

with r > 0 and

with r > 0 and  Here, p is the (positive) length of the

Here, p is the (positive) length of the  between the x-axis and the line. In this case, the equation becomes

between the x-axis and the line. In this case, the equation becomes

with r > 0 and

with r > 0 and

and

and  and then applying the

and then applying the  of the points of a line passing through the origin and making an angle of

of the points of a line passing through the origin and making an angle of  with the x-axis, are the pairs

with the x-axis, are the pairs