| Total population | |

|---|---|

| fewer than 2,953 (2018) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

historically | |

| Languages | |

| English, formerly Wichita | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church, Christianity, Indigenous religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Caddo, Pawnee, other Wichita and Affiliated Tribes |

The Taovaya tribe of the Wichita people were Native Americans originally from Kansas, who moved south into Oklahoma and Texas in the 18th century. They spoke the Taovaya dialect of the Wichita language, a Caddoan language. Taovaya people today are enrolled in the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Anadarko, Oklahoma.

Synonymy

The Taovaya have also been called the Aijado, Tahuayase, Taouaize, Tawehash, Teguayo, Toaya, and Towash.

Culture

Taovaya culture and language was closely related to those of other tribes of the Wichita. They were a semi-agrarian society whose main crops consisted of maize (corn), beans, melons, gourds, and tobacco. Hunting practices consisted of taking on bison, deer and other smaller game.

Early history

The Taovaya are part of the Wichita tribes, which also include the Tawakoni, Waco (Iscani); and Guichita or Wichita Proper. The Taovaya originated in Kansas, and possibly southern Nebraska.

In 1541, Spanish conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado led an expedition across the Great Plains in search of a rich land called Quivira. What he found were ancestral Wichita, a numerous farming and buffalo hunting people in central Kansas who possessed none of the wealth he sought. The furthest part of Quivira is believed to have been located on the Smoky Hill River near Lindsborg, Kansas. This area was called "Tabas", similar to the name Taovaya.

From about 1630 to 1710, the Taovaya might have lived near present-day Marion, Kansas, where archaeological sites belonging to the Great Bend aspect have been discovered.

18th-century history

In 1719, French explorer Claude Charles Du Tisne found two likely Taovaya villages of people he called "Paniouassa" near the present-day Neodesha, Kansas. "Pani" was a generic term the French called both Pawnee Indians and Wichita. That same year another French explorer Bernard de la Harpe visited a village, probably a few miles south of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in which the inhabitants were from several Wichita tribes including the "Toayas" or Taovayas. La Harpe said the Toavayas were said to be the most numerous of the Wichita.

By the 18th century, the Osage encroached upon Wichita lands from the east, and the Apache from the west. In their Kansas and Oklahoma homelands, the Wichita were under intense pressure from both Osage and Apache. In the 1720s the Taovayas and their Guichita relatives began to move south to the Red River establishing a large village on the north side of the river in Jefferson County, Oklahoma, and on the south side at Spanish Fort, Texas. By the late 1750s, many of the Wichita tribes were living in Texas or across the Red River in Oklahoma.

The Taovaya were allied with the French, and in 1746 the French brokered a peace between the Taovaya and other Wichita with the Comanche. The Taovaya achieved their maximum influence during the next few decades. The village at Spanish Fort was "a lively emporium where Comanches brought Apache slaves, horses and mules to trade for French packs of powder, balls, knives, and textiles and for Taovayas-grown maize, melons, pumpkins, squash, and tobacco."

As French allies, the Taovaya ran afoul of the Spanish who had several posts and missions in southern Texas. In 1758, the Comanche, Taovaya, and other Wichita destroyed the San Sabá de la Santa Cruz mission of the Spanish. The next year the Spanish sent a 500-man army north to attack the Taovaya village at Spanish Fort, Texas. An Indian army met the Spaniards and routed them, capturing two cannons and killing or wounding about 50 of the Spaniards. The unsuccessful Spanish attack on Taovaya villages in Texas and Oklahoma in 1759 is known as the Battle of the Twin Villages.

The Taovaya continued to wage war against the Spanish and their Lipan Apache allies while also in the 1760s acting peacefully towards the Spanish missions among the Hasinai, a Caddo tribe. In December 1764 Eyasiquiche, one of the prominent leaders among the Taovaya, led an attack against Spaniards and Apaches near Mission San Lorenzo de la Santa Cruz. In this attack a Spanish soldier, Antonio Trevino, was taken prisoner by the Taovoya. Originally Eyasiquiche planned to adopt Trevino into the Taovaya people, but, on learning he was from Los Adaes, Esquiche decided to return Trevino there.

The French loss of their American colonies in 1763 in the French and Indian War interrupted the flow of trade goods to the Taovayas and made them more receptive to the Spanish. This process took years because the French traders remained in Louisiana, and it was not until Alejandro O'Reilly became governor that regulations were enacted that forbade French trading with the Taovaya. In 1771 the Taovayas, the other Wichita, and the Tonkawa made a peace agreement with the Spanish, defying the Comanche. The Taovaya trading empire was diminished by the Comanche and an epidemic, probably smallpox, that struck the Wichita in 1777 and 1778, killing more than 300 of them. In 1778, the Taovaya village at Spanish Fort had 123 houses and across the Red River a Wichita town had another 37 houses. Together the two towns counted 600 men and a total population of probably around 2,500. This however, was far less than the Wichita population in the time of Coronado when they numbered several tens of thousands. In 1801 another epidemic killed a great number of them. The American Indian agent Dr. John Sibley estimated in 1805 that they numbered 400 men.

19th-century history

The Taovaya as a distinct tribe ended rather suddenly. In 1811, their chief, Awahakei, died during a visit to Americans in Natchitoches, Louisiana. The tribe did not select another leader and fragmented. Some joined the Tawakoni on the Brazos River. The Americans came to collectively call them "Wichita."

In 1835, the Taovaya signed a treaty with the Americans and were relocated from Texas to an Indian reservation in southwest Indian Territory.

Legacy

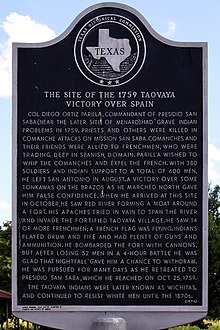

The site of the 1759 Taovaya victory over Spain during the Battle of the Twin Villages received a historic marker in 1976. Its coordinates are 33°56′52.9434″N 97°36′58.33″W / 33.948039833°N 97.6162028°W / 33.948039833; -97.6162028 (1759 Taovayo victory over Spain).

The Taovayan Valley, a geographic region encompassing the area between the Wichita Mountains and the Red River of the South, is named after the tribe. The region was the tribe's last stronghold prior to removal to Indian Territory.

See also

- Southern Plains villagers

- Etzanoa, Kansas

- Francisco Xavier Chaves, 1760-1832, Negotiated peace for Texas with Taovaya and Comanche in 1785.

- Pedro Vial, 1746-1814, Frenchman who lived with Taovaya as gunsmith and trader.

- Spanish Fort, Texas

Notes

- Gately, Paul (8 July 2018). "Native Americans chose Waco for water and abundance, like others". 10 KWTX. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Jelks, Edward B. "Taovaya Indians". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- Susan C. Vehik, "Wichita Culture History," Plains Anthropologist 37, no. 131 (1992): p. 311.

- Elizabeth Ann Harper , "The Taovaya Indians in Frontier Trade and Diplomacy 1719–1768," Chronicles of Oklahoma, 31, no. 3 (1953): p. 269.

- Vehik, 328; Roper, Donna C. "The Marion Great Bend Aspect Sits: Floodplain Settlement on the Plains." Plains Anthropologist, 47, no. 180 (2002): p. 17–32.

- Anna Lewis, "La Harpe's First Expedition in Oklahoma," Chronicles of Oklahoma, 2, no.4 (December 1924): p. 344.

- Earl Henry Elam, "Anglo-American Relations with the Wichita Indians in Texas, 1822–1859," Master's Thesis, Texas Technological College, 1967, p. 11.

- Sam D. Ratcliffe, "'Escenas de Maritiro': Notes on the Destruction of Mission San Sabá", The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 94, no. 4 (April 1991): pp. 507–34.

- Elizabeth A. H. John, Storms Brewed in Other Men's Worlds (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1975), p. 32.

- Juliana Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2007), p. 197-99.

- Pekka Haalainen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 96-97; Earl Henry Elam, "Anglo-American Relations with the Wichita Indians in Texas, 1822–1839," "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), 18. - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), 17. - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), 19 - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), pp. 19-20. - Site of the 1759 Taovayo Victory Over Spain, From Nocona take FM 103 approximately 17 miles to Spanish Fort Marker is located next to large granite monument in center of town: Texas marker #4922.

External links

- Taovaya Indians, Texas State Historical Society

- Tawehash, Four Directions Institute

- Article about 18th-century Taovaya fortress and battle with the Spanish, Western Digs

| Federally recognized tribes | |

|---|---|

| Indigenous languages | |

| Historical Indigenous peoples of Texas (Several are in Oklahoma today) |

|

| Related topics | |

| extinct language / extinct tribe / early, obsolete name of Indigenous tribe / people absorbed into other tribe(s) / headquartered in Oklahoma today | |