| Radian | |

|---|---|

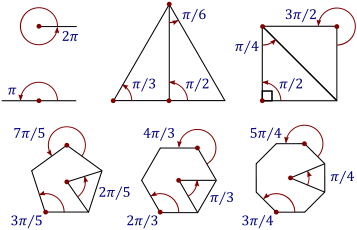

An arc of a circle with the same length as the radius of that circle subtends an angle of 1 radian. The circumference subtends an angle of 2π radians. An arc of a circle with the same length as the radius of that circle subtends an angle of 1 radian. The circumference subtends an angle of 2π radians. | |

| General information | |

| Unit system | SI |

| Unit of | angle |

| Symbol | rad, |

| Conversions | |

| 1 rad in ... | ... is equal to ... |

| milliradians | 1000 mrad |

| turns | 1/2π turn ≈ 0.159154 turn |

| degrees | 180/π° ≈ 57.295779513° |

| gradians | 200/π grad ≈ 63.661977 |

The radian, denoted by the symbol rad, is the unit of angle in the International System of Units (SI) and is the standard unit of angular measure used in many areas of mathematics. It is defined such that one radian is the angle subtended at the centre of a circle by an arc that is equal in length to the radius. The unit was formerly an SI supplementary unit and is currently a dimensionless SI derived unit, defined in the SI as 1 rad = 1 and expressed in terms of the SI base unit metre (m) as rad = m/m. Angles without explicitly specified units are generally assumed to be measured in radians, especially in mathematical writing.

Definition

One radian is defined as the angle at the center of a circle in a plane that subtends an arc whose length equals the radius of the circle. More generally, the magnitude in radians of a subtended angle is equal to the ratio of the arc length to the radius of the circle; that is, , where θ is the magnitude in radians of the subtended angle, s is arc length, and r is radius. A right angle is exactly radians.

One complete revolution, expressed as an angle in radians, is the length of the circumference divided by the radius, which is , or 2π. Thus, 2π radians is equal to 360 degrees. The relation 2π rad = 360° can be derived using the formula for arc length, . Since radian is the measure of an angle that is subtended by an arc of a length equal to the radius of the circle, . This can be further simplified to . Multiplying both sides by 360° gives 360° = 2π rad.

Unit symbol

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures and International Organization for Standardization specify rad as the symbol for the radian. Alternative symbols that were in use in 1909 are (the superscript letter c, for "circular measure"), the letter r, or a superscript , but these variants are infrequently used, as they may be mistaken for a degree symbol (°) or a radius (r). Hence an angle of 1.2 radians would be written today as 1.2 rad; archaic notations include 1.2 r, 1.2, 1.2, or 1.2.

In mathematical writing, the symbol "rad" is often omitted. When quantifying an angle in the absence of any symbol, radians are assumed, and when degrees are meant, the degree sign ° is used.

Dimensional analysis

Plane angle may be defined as θ = s/r, where θ is the magnitude in radians of the subtended angle, s is circular arc length, and r is radius. One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r, hence 1 radian = 1 m/m = 1. However, rad is only to be used to express angles, not to express ratios of lengths in general. A similar calculation using the area of a circular sector θ = 2A/r gives 1 radian as 1 m/m = 1. The key fact is that the radian is a dimensionless unit equal to 1. In SI 2019, the SI radian is defined accordingly as 1 rad = 1. It is a long-established practice in mathematics and across all areas of science to make use of rad = 1.

Giacomo Prando writes "the current state of affairs leads inevitably to ghostly appearances and disappearances of the radian in the dimensional analysis of physical equations". For example, an object hanging by a string from a pulley will rise or drop by y = rθ centimetres, where r is the magnitude of the radius of the pulley in centimetres and θ is the magnitude of the angle through which the pulley turns in radians. When multiplying r by θ, the unit radian does not appear in the product, nor does the unit centimetre—because both factors are magnitudes (numbers). Similarly in the formula for the angular velocity of a rolling wheel, ω = v/r, radians appear in the units of ω but not on the right hand side. Anthony French calls this phenomenon "a perennial problem in the teaching of mechanics". Oberhofer says that the typical advice of ignoring radians during dimensional analysis and adding or removing radians in units according to convention and contextual knowledge is "pedagogically unsatisfying".

In 1993 the American Association of Physics Teachers Metric Committee specified that the radian should explicitly appear in quantities only when different numerical values would be obtained when other angle measures were used, such as in the quantities of angle measure (rad), angular speed (rad/s), angular acceleration (rad/s), and torsional stiffness (N⋅m/rad), and not in the quantities of torque (N⋅m) and angular momentum (kg⋅m/s).

At least a dozen scientists between 1936 and 2022 have made proposals to treat the radian as a base unit of measurement for a base quantity (and dimension) of "plane angle". Quincey's review of proposals outlines two classes of proposal. The first option changes the unit of a radius to meters per radian, but this is incompatible with dimensional analysis for the area of a circle, πr. The other option is to introduce a dimensional constant. According to Quincey this approach is "logically rigorous" compared to SI, but requires "the modification of many familiar mathematical and physical equations". A dimensional constant for angle is "rather strange" and the difficulty of modifying equations to add the dimensional constant is likely to preclude widespread use.

In particular, Quincey identifies Torrens' proposal to introduce a constant η equal to 1 inverse radian (1 rad) in a fashion similar to the introduction of the constant ε0. With this change the formula for the angle subtended at the center of a circle, s = rθ, is modified to become s = ηrθ, and the Taylor series for the sine of an angle θ becomes: where is the angle in radians. The capitalized function Sin is the "complete" function that takes an argument with a dimension of angle and is independent of the units expressed, while sin is the traditional function on pure numbers which assumes its argument is a dimensionless number in radians. The capitalised symbol can be denoted if it is clear that the complete form is meant.

Current SI can be considered relative to this framework as a natural unit system where the equation η = 1 is assumed to hold, or similarly, 1 rad = 1. This radian convention allows the omission of η in mathematical formulas.

Defining radian as a base unit may be useful for software, where the disadvantage of longer equations is minimal. For example, the Boost units library defines angle units with a plane_angle dimension, and Mathematica's unit system similarly considers angles to have an angle dimension.

Conversions

| Turns | Radians | Degrees | Gradians |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 turn | 0 rad | 0° | 0 |

| 1/72 turn | π/36 or 𝜏/72 rad | 5° | 5+5/9 |

| 1/24 turn | π/12 or 𝜏/24 rad | 15° | 16+2/3 |

| 1/16 turn | π/8 or 𝜏/16 rad | 22.5° | 25 |

| 1/12 turn | π/6 or 𝜏/12 rad | 30° | 33+1/3 |

| 1/10 turn | π/5 or 𝜏/10 rad | 36° | 40 |

| 1/8 turn | π/4 or 𝜏/8 rad | 45° | 50 |

| 1/2π or 𝜏 turn | 1 rad | approx. 57.3° | approx. 63.7 |

| 1/6 turn | π/3 or 𝜏/6 rad | 60° | 66+2/3 |

| 1/5 turn | 2π or 𝜏/5 rad | 72° | 80 |

| 1/4 turn | π/2 or 𝜏/4 rad | 90° | 100 |

| 1/3 turn | 2π or 𝜏/3 rad | 120° | 133+1/3 |

| 2/5 turn | 4π or 2𝜏 or α/5 rad | 144° | 160 |

| 1/2 turn | π or 𝜏/2 rad | 180° | 200 |

| 3/4 turn | 3π or ρ/2 or 3𝜏/4 rad | 270° | 300 |

| 1 turn | 𝜏 or 2π rad | 360° | 400 |

Between degrees

As stated, one radian is equal to . Thus, to convert from radians to degrees, multiply by .

For example:

Conversely, to convert from degrees to radians, multiply by .

For example:

Radians can be converted to turns (one turn is the angle corresponding to a revolution) by dividing the number of radians by 2π.

Between gradians

One revolution is radians, which equals one turn, which is by definition 400 gradians (400 gons or 400). To convert from radians to gradians multiply by , and to convert from gradians to radians multiply by . For example,

Usage

Mathematics

In calculus and most other branches of mathematics beyond practical geometry, angles are measured in radians. This is because radians have a mathematical naturalness that leads to a more elegant formulation of some important results.

Results in analysis involving trigonometric functions can be elegantly stated when the functions' arguments are expressed in radians. For example, the use of radians leads to the simple limit formula

which is the basis of many other identities in mathematics, including

Because of these and other properties, the trigonometric functions appear in solutions to mathematical problems that are not obviously related to the functions' geometrical meanings (for example, the solutions to the differential equation , the evaluation of the integral and so on). In all such cases, it is appropriate that the arguments of the functions are treated as (dimensionless) numbers—without any reference to angles.

The trigonometric functions of angles also have simple and elegant series expansions when radians are used. For example, when x is the angle expressed in radians, the Taylor series for sin x becomes:

If y were the angle x but expressed in degrees, i.e. y = πx / 180, then the series would contain messy factors involving powers of π/180:

In a similar spirit, if angles are involved, mathematically important relationships between the sine and cosine functions and the exponential function (see, for example, Euler's formula) can be elegantly stated when the functions' arguments are angles expressed in radians (and messy otherwise). More generally, in complex-number theory, the arguments of these functions are (dimensionless, possibly complex) numbers—without any reference to physical angles at all.

Physics

The radian is widely used in physics when angular measurements are required. For example, angular velocity is typically expressed in the unit radian per second (rad/s). One revolution per second corresponds to 2π radians per second.

Similarly, the unit used for angular acceleration is often radian per second per second (rad/s).

For the purpose of dimensional analysis, the units of angular velocity and angular acceleration are s and s respectively.

Likewise, the phase angle difference of two waves can also be expressed using the radian as the unit. For example, if the phase angle difference of two waves is (n⋅2π) radians, where n is an integer, they are considered to be in phase, whilst if the phase angle difference of two waves is (n⋅2π + π) radians, with n an integer, they are considered to be in antiphase.

A unit of reciprocal radian or inverse radian (rad) is involved in derived units such as meter per radian (for angular wavelength) or newton-metre per radian (for torsional stiffness).

Prefixes and variants

Metric prefixes for submultiples are used with radians. A milliradian (mrad) is a thousandth of a radian (0.001 rad), i.e. 1 rad = 10 mrad. There are 2π × 1000 milliradians (≈ 6283.185 mrad) in a circle. So a milliradian is just under 1/6283 of the angle subtended by a full circle. This unit of angular measurement of a circle is in common use by telescopic sight manufacturers using (stadiametric) rangefinding in reticles. The divergence of laser beams is also usually measured in milliradians.

The angular mil is an approximation of the milliradian used by NATO and other military organizations in gunnery and targeting. Each angular mil represents 1/6400 of a circle and is 15/8% or 1.875% smaller than the milliradian. For the small angles typically found in targeting work, the convenience of using the number 6400 in calculation outweighs the small mathematical errors it introduces. In the past, other gunnery systems have used different approximations to 1/2000π; for example Sweden used the 1/6300 streck and the USSR used 1/6000. Being based on the milliradian, the NATO mil subtends roughly 1 m at a range of 1000 m (at such small angles, the curvature is negligible).

Prefixes smaller than milli- are useful in measuring extremely small angles. Microradians (μrad, 10 rad) and nanoradians (nrad, 10 rad) are used in astronomy, and can also be used to measure the beam quality of lasers with ultra-low divergence. More common is the arc second, which is π/648,000 rad (around 4.8481 microradians).

| Submultiples | Multiples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | SI symbol | Name | Value | SI symbol | Name |

| 10 rad | drad | deciradian | 10 rad | darad | decaradian |

| 10 rad | crad | centiradian | 10 rad | hrad | hectoradian |

| 10 rad | mrad | milliradian | 10 rad | krad | kiloradian |

| 10 rad | μrad | microradian | 10 rad | Mrad | megaradian |

| 10 rad | nrad | nanoradian | 10 rad | Grad | gigaradian |

| 10 rad | prad | picoradian | 10 rad | Trad | teraradian |

| 10 rad | frad | femtoradian | 10 rad | Prad | petaradian |

| 10 rad | arad | attoradian | 10 rad | Erad | exaradian |

| 10 rad | zrad | zeptoradian | 10 rad | Zrad | zettaradian |

| 10 rad | yrad | yoctoradian | 10 rad | Yrad | yottaradian |

| 10 rad | rrad | rontoradian | 10 rad | Rrad | ronnaradian |

| 10 rad | qrad | quectoradian | 10 rad | Qrad | quettaradian |

History

Pre-20th century

The idea of measuring angles by the length of the arc was in use by mathematicians quite early. For example, al-Kashi (c. 1400) used so-called diameter parts as units, where one diameter part was 1/60 radian. They also used sexagesimal subunits of the diameter part. Newton in 1672 spoke of "the angular quantity of a body's circular motion", but used it only as a relative measure to develop an astronomical algorithm.

The concept of the radian measure is normally credited to Roger Cotes, who died in 1716. By 1722, his cousin Robert Smith had collected and published Cotes' mathematical writings in a book, Harmonia mensurarum. In a chapter of editorial comments, Smith gave what is probably the first published calculation of one radian in degrees, citing a note of Cotes that has not survived. Smith described the radian in everything but name – "Now this number is equal to 180 degrees as the radius of a circle to the semicircumference, this is as 1 to 3.141592653589" –, and recognized its naturalness as a unit of angular measure.

In 1765, Leonhard Euler implicitly adopted the radian as a unit of angle. Specifically, Euler defined angular velocity as "The angular speed in rotational motion is the speed of that point, the distance of which from the axis of gyration is expressed by one." Euler was probably the first to adopt this convention, referred to as the radian convention, which gives the simple formula for angular velocity ω = v/r. As discussed in § Dimensional analysis, the radian convention has been widely adopted, while dimensionally consistent formulations require the insertion of a dimensional constant, for example ω = v/(ηr).

Prior to the term radian becoming widespread, the unit was commonly called circular measure of an angle. The term radian first appeared in print on 5 June 1873, in examination questions set by James Thomson (brother of Lord Kelvin) at Queen's College, Belfast. He had used the term as early as 1871, while in 1869, Thomas Muir, then of the University of St Andrews, vacillated between the terms rad, radial, and radian. In 1874, after a consultation with James Thomson, Muir adopted radian. The name radian was not universally adopted for some time after this. Longmans' School Trigonometry still called the radian circular measure when published in 1890.

In 1893 Alexander Macfarlane wrote "the true analytical argument for the circular ratios is not the ratio of the arc to the radius, but the ratio of twice the area of a sector to the square on the radius." However, the paper was withdrawn from the published proceedings of mathematical congress held in connection with World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (acknowledged at page 167), and privately published in his Papers on Space Analysis (1894). Macfarlane reached this idea or ratios of areas while considering the basis for hyperbolic angle which is analogously defined.

As an SI unit

As Paul Quincey et al. write, "the status of angles within the International System of Units (SI) has long been a source of controversy and confusion." In 1960, the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) established the SI and the radian was classified as a "supplementary unit" along with the steradian. This special class was officially regarded "either as base units or as derived units", as the CGPM could not reach a decision on whether the radian was a base unit or a derived unit. Richard Nelson writes "This ambiguity prompted a spirited discussion over their proper interpretation." In May 1980 the Consultative Committee for Units (CCU) considered a proposal for making radians an SI base unit, using a constant α0 = 1 rad, but turned it down to avoid an upheaval to current practice.

In October 1980 the CGPM decided that supplementary units were dimensionless derived units for which the CGPM allowed the freedom of using them or not using them in expressions for SI derived units, on the basis that " exists which is at the same time coherent and convenient and in which the quantities plane angle and solid angle might be considered as base quantities" and that " compromises the internal coherence of the SI based on only seven base units". In 1995 the CGPM eliminated the class of supplementary units and defined the radian and the steradian as "dimensionless derived units, the names and symbols of which may, but need not, be used in expressions for other SI derived units, as is convenient". Mikhail Kalinin writing in 2019 has criticized the 1980 CGPM decision as "unfounded" and says that the 1995 CGPM decision used inconsistent arguments and introduced "numerous discrepancies, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the wordings of the SI".

At the 2013 meeting of the CCU, Peter Mohr gave a presentation on alleged inconsistencies arising from defining the radian as a dimensionless unit rather than a base unit. CCU President Ian M. Mills declared this to be a "formidable problem" and the CCU Working Group on Angles and Dimensionless Quantities in the SI was established. The CCU met in 2021, but did not reach a consensus. A small number of members argued strongly that the radian should be a base unit, but the majority felt the status quo was acceptable or that the change would cause more problems than it would solve. A task group was established to "review the historical use of SI supplementary units and consider whether reintroduction would be of benefit", among other activities.

See also

- Angular frequency

- Minute and second of arc

- Steradian, a higher-dimensional analog of the radian which measures solid angle

- Trigonometry

Notes

- Other proposals include the abbreviation "rad" (Brinsmade 1936), the notation (Romain 1962), and the constants ם (Brownstein 1997), ◁ (Lévy-Leblond 1998), k (Foster 2010), θC (Quincey 2021), and (Mohr et al. 2022).

References

- ^ Hall, Arthur Graham; Frink, Fred Goodrich (January 1909). "Chapter VII. The General Angle Signs and Limitations in Value. Exercise XV.". Written at Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Trigonometry. Vol. Part I: Plane Trigonometry. New York, USA: Henry Holt and Company / Norwood Press / J. S. Cushing Co. - Berwick & Smith Co., Norwood, Massachusetts, USA. p. 73. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: "The CGPM decided to interpret the supplementary units in the SI, namely the radian and the steradian, as dimensionless derived units."

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: "One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r, thus 1 rad = 1."

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 137.

- Ocean Optics Protocols for Satellite Ocean Color Sensor Validation, Revision 3. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Goddard Space Flight Center. 2002. p. 12.

- Protter, Murray H.; Morrey, Charles B. Jr. (1970), College Calculus with Analytic Geometry (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, p. APP-4, LCCN 76087042

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151.

- "ISO 80000-3:2006 Quantities and Units - Space and Time". 17 January 2017.

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: "One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r"

- Quincey 2016, p. 844: "Also, as alluded to in Mohr & Phillips 2015, the radian can be defined in terms of the area A of a sector (A = 1/2 θ r), in which case it has the units m⋅m."

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: "One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r, thus 1 rad = 1."

- Bridgman, Percy Williams (1922). Dimensional analysis. New Haven : Yale University Press.

Angular amplitude of swing No dimensions.

- Prando, Giacomo (August 2020). "A spectral unit". Nature Physics. 16 (8): 888. Bibcode:2020NatPh..16..888P. doi:10.1038/s41567-020-0997-3. S2CID 225445454.

- Leonard, William J. (1999). Minds-on Physics: Advanced topics in mechanics. Kendall Hunt. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-7872-5412-4.

- French, Anthony P. (May 1992). "What happens to the 'radians'? (comment)". The Physics Teacher. 30 (5): 260–261. doi:10.1119/1.2343535.

- Oberhofer, E. S. (March 1992). "What happens to the 'radians'?". The Physics Teacher. 30 (3): 170–171. Bibcode:1992PhTea..30..170O. doi:10.1119/1.2343500.

- Aubrecht, Gordon J.; French, Anthony P.; Iona, Mario; Welch, Daniel W. (February 1993). "The radian—That troublesome unit". The Physics Teacher. 31 (2): 84–87. Bibcode:1993PhTea..31...84A. doi:10.1119/1.2343667.

- Brinsmade 1936; Romain 1962; Eder 1982; Torrens 1986; Brownstein 1997; Lévy-Leblond 1998; Foster 2010; Mills 2016; Quincey 2021; Leonard 2021; Mohr et al. 2022

- Mohr & Phillips 2015.

- ^ Quincey, Paul; Brown, Richard J C (1 June 2016). "Implications of adopting plane angle as a base quantity in the SI". Metrologia. 53 (3): 998–1002. arXiv:1604.02373. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..998Q. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/3/998. S2CID 119294905.

- ^ Quincey 2016.

- ^ Torrens 1986.

- Mohr et al. 2022, p. 6.

- Mohr et al. 2022, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Quincey 2021.

- Quincey, Paul; Brown, Richard J C (1 August 2017). "A clearer approach for defining unit systems". Metrologia. 54 (4): 454–460. arXiv:1705.03765. Bibcode:2017Metro..54..454Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/aa7160. S2CID 119418270.

- Schabel, Matthias C.; Watanabe, Steven. "Boost.Units FAQ – 1.79.0". www.boost.org. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

Angles are treated as units

- Mohr et al. 2022, p. 3.

- "UnityDimensions—Wolfram Language Documentation". reference.wolfram.com. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- Luckey, Paul (1953) . Siggel, A. (ed.). Der Lehrbrief über den kreisumfang von Gamshid b. Mas'ud al-Kasi [Treatise on the Circumference of al-Kashi]. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. p. 40.

- ^ Roche, John J. (21 December 1998). The Mathematics of Measurement: A Critical History. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-387-91581-4.

- O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (February 2005). "Biography of Roger Cotes". The MacTutor History of Mathematics. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- Cotes, Roger (1722). "Editoris notæ ad Harmoniam mensurarum". In Smith, Robert (ed.). Harmonia mensurarum (in Latin). Cambridge, England. pp. 94–95.

In Canone Logarithmico exhibetur Systema quoddam menfurarum numeralium, quæ Logarithmi dicuntur: atque hujus systematis Modulus is est Logarithmus, qui metitur Rationem Modularem in Corol. 6. definitam. Similiter in Canone Trigonometrico finuum & tangentium, exhibetur Systema quoddam menfurarum numeralium, quæ Gradus appellantur: atque hujus systematis Modulus is est Numerus Graduum, qui metitur Angulum Modularem modo definitun, hoc est, qui continetur in arcu Radio æquali. Eft autem hic Numerus ad Gradus 180 ut Circuli Radius ad Semicircuinferentiam, hoc eft ut 1 ad 3.141592653589 &c. Unde Modulus Canonis Trigonometrici prodibit 57.2957795130 &c. Cujus Reciprocus eft 0.0174532925 &c. Hujus moduli subsidio (quem in chartula quadam Auctoris manu descriptum inveni) commodissime computabis mensuras angulares, queinadmodum oftendam in Nota III.

[In the Logarithmic Canon there is presented a certain system of numerical measures called Logarithms: and the Modulus of this system is the Logarithm, which measures the Modular Ratio as defined in Corollary 6. Similarly, in the Trigonometrical Canon of sines and tangents, there is presented a certain system of numerical measures called Degrees: and the Modulus of this system is the Number of Degrees which measures the Modular Angle defined in the manner defined, that is, which is contained in an equal Radius arc. Now this Number is equal to 180 Degrees as the Radius of a Circle to the Semicircumference, this is as 1 to 3.141592653589 &c. Hence the Modulus of the Trigonometric Canon will be 57.2957795130 &c. Whose Reciprocal is 0.0174532925 &c. With the help of this modulus (which I found described in a note in the hand of the Author) you will most conveniently calculate the angular measures, as mentioned in Note III.] - Gowing, Ronald (27 June 2002). Roger Cotes - Natural Philosopher. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52649-4.

- Euler, Leonhard. Theoria Motus Corporum Solidorum seu Rigidorum [Theory of the motion of solid or rigid bodies] (PDF) (in Latin). Translated by Bruce, Ian. Definition 6, paragraph 316.

- Isaac Todhunter, Plane Trigonometry: For the Use of Colleges and Schools, p. 10, Cambridge and London: MacMillan, 1864 OCLC 500022958

- Cajori, Florian (1929). History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 2. Dover Publications. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0-486-67766-4.

-

- Muir, Thos. (1910). "The Term "Radian" in Trigonometry". Nature. 83 (2110): 156. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..156M. doi:10.1038/083156a0. S2CID 3958702.

- Thomson, James (1910). "The Term "Radian" in Trigonometry". Nature. 83 (2112): 217. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..217T. doi:10.1038/083217c0. S2CID 3980250.

- Muir, Thos. (1910). "The Term "Radian" in Trigonometry". Nature. 83 (2120): 459–460. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..459M. doi:10.1038/083459d0. S2CID 3971449.

- Miller, Jeff (Nov 23, 2009). "Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics". Retrieved Sep 30, 2011.

- Frederick Sparks, Longmans' School Trigonometry, p. 6, London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1890 OCLC 877238863 (1891 edition)

- A. Macfarlane (1893) "On the definitions of the trigonometric functions", page 9, link at Internet Archive

-

Geometry/Unified Angles at Wikibooks

Geometry/Unified Angles at Wikibooks

- Quincey, Paul; Mohr, Peter J.; Phillips, William D. (1 August 2019). "Angles are inherently neither length ratios nor dimensionless". Metrologia. 56 (4): 043001. arXiv:1909.08389. Bibcode:2019Metro..56d3001Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ab27d7. S2CID 198428043.

- Le Système international d'unités (in French), 1970, p. 12,

Pour quelques unités du Système International, la Conférence Générale n'a pas ou n'a pas encore décidé s'il s'agit d'unités de base ou bien d'unités dérivées.

[For some units of the SI, the CGPM still hasn't yet decided whether they are base units or derived units.] - ^ Nelson, Robert A. (March 1984). "The supplementary units". The Physics Teacher. 22 (3): 188–193. Bibcode:1984PhTea..22..188N. doi:10.1119/1.2341516.

- Report of the 7th meeting (in French), Consultative Committee for Units, May 1980, pp. 6–7

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, pp. 174–175.

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 179.

- Kalinin, Mikhail I (1 December 2019). "On the status of plane and solid angles in the International System of Units (SI)". Metrologia. 56 (6): 065009. arXiv:1810.12057. Bibcode:2019Metro..56f5009K. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ab3fbf. S2CID 53627142.

- Consultative Committee for Units (11–12 June 2013). Report of the 21st meeting to the International Committee for Weights and Measures (Report). pp. 18–20.

- Consultative Committee for Units (21–23 September 2021). Report of the 25th meeting to the International Committee for Weights and Measures (Report). pp. 16–17.

- "CCU Task Group on angle and dimensionless quantities in the SI Brochure (CCU-TG-ADQSIB)". BIPM. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures (20 May 2019), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (9th ed.), ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0, archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2021

- Brinsmade, J. B. (December 1936). "Plane and Solid Angles. Their Pedagogic Value When Introduced Explicitly". American Journal of Physics. 4 (4): 175–179. Bibcode:1936AmJPh...4..175B. doi:10.1119/1.1999110.

- Romain, Jacques E. (July 1962). "Angle as a fourth fundamental quantity". Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards Section B. 66B (3): 97. doi:10.6028/jres.066B.012.

- Eder, W E (January 1982). "A Viewpoint on the Quantity "Plane Angle"". Metrologia. 18 (1): 1–12. Bibcode:1982Metro..18....1E. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/18/1/002. S2CID 250750831.

- Torrens, A B (1 January 1986). "On Angles and Angular Quantities". Metrologia. 22 (1): 1–7. Bibcode:1986Metro..22....1T. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/22/1/002. S2CID 250801509.

- Brownstein, K. R. (July 1997). "Angles—Let's treat them squarely". American Journal of Physics. 65 (7): 605–614. Bibcode:1997AmJPh..65..605B. doi:10.1119/1.18616.

- Lévy-Leblond, Jean-Marc (September 1998). "Dimensional angles and universal constants". American Journal of Physics. 66 (9): 814–815. Bibcode:1998AmJPh..66..814L. doi:10.1119/1.18964.

- Foster, Marcus P (1 December 2010). "The next 50 years of the SI: a review of the opportunities for the e-Science age". Metrologia. 47 (6): R41 – R51. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/47/6/R01. S2CID 117711734.

- Mohr, Peter J; Phillips, William D (1 February 2015). "Dimensionless units in the SI". Metrologia. 52 (1): 40–47. arXiv:1409.2794. Bibcode:2015Metro..52...40M. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/52/1/40.

- Quincey, Paul (1 April 2016). "The range of options for handling plane angle and solid angle within a system of units". Metrologia. 53 (2): 840–845. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..840Q. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/2/840. S2CID 125438811.

- Mills, Ian (1 June 2016). "On the units radian and cycle for the quantity plane angle". Metrologia. 53 (3): 991–997. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..991M. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/3/991. S2CID 126032642.

- Quincey, Paul (1 October 2021). "Angles in the SI: a detailed proposal for solving the problem". Metrologia. 58 (5): 053002. arXiv:2108.05704. Bibcode:2021Metro..58e3002Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ac023f. S2CID 236547235.

- Leonard, B P (1 October 2021). "Proposal for the dimensionally consistent treatment of angle and solid angle by the International System of Units (SI)". Metrologia. 58 (5): 052001. Bibcode:2021Metro..58e2001L. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/abe0fc. S2CID 234036217.

- Mohr, Peter J; Shirley, Eric L; Phillips, William D; Trott, Michael (23 June 2022). "On the dimension of angles and their units". Metrologia. 59 (5): 053001. arXiv:2203.12392. Bibcode:2022Metro..59e3001M. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ac7bc2.

External links

Media related to Radian at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Radian at Wikimedia Commons

| SI units | |

|---|---|

| Base units | |

| Derived units with special names | |

| Other accepted units | |

| See also | |

, where θ is the magnitude in radians of the subtended angle, s is arc length, and r is radius. A

, where θ is the magnitude in radians of the subtended angle, s is arc length, and r is radius. A  radians.

radians.

, or 2π. Thus, 2π radians is equal to 360 degrees. The relation 2π rad = 360° can be derived using the formula for

, or 2π. Thus, 2π radians is equal to 360 degrees. The relation 2π rad = 360° can be derived using the formula for  . Since radian is the measure of an angle that is subtended by an arc of a length equal to the radius of the circle,

. Since radian is the measure of an angle that is subtended by an arc of a length equal to the radius of the circle,  . This can be further simplified to

. This can be further simplified to  . Multiplying both sides by 360° gives 360° = 2π rad.

. Multiplying both sides by 360° gives 360° = 2π rad.

where

where  is the angle in radians.

The capitalized function Sin is the "complete" function that takes an argument with a dimension of angle and is independent of the units expressed, while sin is the traditional function on

is the angle in radians.

The capitalized function Sin is the "complete" function that takes an argument with a dimension of angle and is independent of the units expressed, while sin is the traditional function on  can be denoted

can be denoted  if it is clear that the complete form is meant.

if it is clear that the complete form is meant.

. Thus, to convert from radians to degrees, multiply by

. Thus, to convert from radians to degrees, multiply by

.

.

radians, which equals one

radians, which equals one  , and to convert from gradians to radians multiply by

, and to convert from gradians to radians multiply by  . For example,

. For example,

, the evaluation of the integral

, the evaluation of the integral  and so on). In all such cases, it is appropriate that the arguments of the functions are treated as (dimensionless) numbers—without any reference to angles.

and so on). In all such cases, it is appropriate that the arguments of the functions are treated as (dimensionless) numbers—without any reference to angles.

(

( (

(