| Revision as of 04:31, 16 March 2021 editDavid Eppstein (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators226,376 edits →Ropelength: shorter per GA review← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:29, 20 October 2024 edit undo91.139.213.126 (talk)No edit summary | ||

| (94 intermediate revisions by 38 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Three linked but pairwise separated rings}} | ||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Infobox knot theory | {{Infobox knot theory | ||

| | name= Borromean rings | | name= Borromean rings | ||

| | practical name= |

| practical name= | ||

| | image= Borromean Rings Illusion.png | | image= Borromean Rings Illusion (transparent).png | ||

| | caption= L6a4 | | caption= L6a4 | ||

| | arf invariant= |

| arf invariant= | ||

| | braid number= |

| braid number= | ||

| | braid length= |

| braid length= | ||

| | bridge number= |

| bridge number= | ||

| | crossing number= 6 | | crossing number= 6 | ||

| | hyperbolic volume= 7.327724753 | | hyperbolic volume= 7.327724753 | ||

| | linking number= |

| linking number= | ||

| | stick number= 9 | | stick number= 9 | ||

| | unknotting number= | | unknotting number= | ||

| | conway_notation= .1 | | conway_notation= .1 | ||

| | ab_notation= 6{{sup sub|3|2}} | | ab_notation= 6{{sup sub|3|2}} | ||

| | dowker notation= |

| dowker notation= | ||

| | thistlethwaite= L6a4 | | thistlethwaite= L6a4 | ||

| | other= |

| other= | ||

| | alternating= alternating | | alternating= alternating | ||

| | amphichiral= |

| amphichiral= | ||

| | class= hyperbolic | | class= hyperbolic | ||

| | fibered= |

| fibered= | ||

| | slice= | |||

| | tricolorable= | |||

| | slice= | |||

| | last link= | |||

| | |

| next link= | ||

| | next link= | |||

| }} | }} | ||

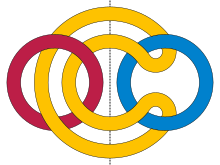

| In ], the '''Borromean rings''' are three ]s in three-dimensional space that are ] and cannot be separated from each other, but that break apart into two unknotted and unlinked loops when any one of the three is cut or removed. Most commonly, these rings are drawn as three circles in the plane, in the pattern of a ], ] at the points where they cross. Other triples of curves are said to form the Borromean rings as long as they are topologically equivalent to the curves depicted in this drawing. | In ], the '''Borromean rings'''{{efn|Pronounced {{IPAc-en|b|ɒ|r|ou|ˈ|m|iː|ə|n}}<ref>Mackey & Mackay 1922 ''The Pronunciation of 10,000 Proper Names''</ref>}} are three ]s in three-dimensional space that are ] and cannot be separated from each other, but that break apart into two unknotted and unlinked loops when any one of the three is cut or removed. Most commonly, these rings are drawn as three circles in the plane, in the pattern of a ], ] at the points where they cross. Other triples of curves are said to form the Borromean rings as long as they are topologically equivalent to the curves depicted in this drawing. | ||

| The Borromean rings are named after the Italian ], who used the circular form of these rings as |

The Borromean rings are named after the Italian ], who used the circular form of these rings as an element of their ], but designs based on the Borromean rings have been used in many cultures, including by the ] and in Japan. They have been used in Christian symbolism as a sign of the ], and in modern commerce as the logo of ], giving them the alternative name '''Ballantine rings'''. Physical instances of the Borromean rings have been made from linked ] or other molecules, and they have analogues in the ] and ], both of which have three components bound to each other although no two of them are bound. | ||

| Geometrically, the Borromean rings may be realized by linked ]s, or (using the vertices of a regular ]) by linked ]s. It is impossible to realize them using circles in three-dimensional space, but it has been conjectured that they may be realized by copies of any non-circular simple closed curve in space. In ], the Borromean rings can be proved to be linked by counting their ]. As links, they are ], ], ], and ]. In ], certain triples of ]s have analogous linking properties to the Borromean rings. | Geometrically, the Borromean rings may be realized by linked ]s, or (using the vertices of a regular ]) by linked ]s. It is impossible to realize them using circles in three-dimensional space, but it has been conjectured that they may be realized by copies of any non-circular simple closed curve in space. In ], the Borromean rings can be proved to be linked by counting their ]. As links, they are ], ], ], and ]. In ], certain triples of ]s have analogous linking properties to the Borromean rings. | ||

| ==Definition and notation== | == Definition and notation == | ||

| It is common in mathematics publications that define the Borromean rings to do so as a ], a drawing of curves in the plane with crossings marked to indicate which curve or part of a curve passes above or below at each crossing. Such a drawing can be transformed into a system of curves in three-dimensional space by embedding the plane into space and deforming the curves drawn on it above or below the embedded plane at each crossing, as indicated in the diagram. The commonly-used diagram for the Borromean rings consists of three equal ]s centered at the points of an ], close enough together that their interiors have a common intersection (such as in a ] or the three circles used to define the ]). Its crossings ] between above and below when considered in consecutive order around each circle;{{r|imu|trinity|book}} another equivalent way to describe the over-under relation between the three circles is that each circle passes over a second circle at both of their crossings, and under the third circle at both of their crossings.{{r|roshambo}} Two links are said to be equivalent if there is a continuous deformation of space (an ]) taking one to another, and the Borromean rings may refer to any link that is equivalent in this sense to the standard diagram for this link.{{r|book}} | It is common in mathematics publications that define the Borromean rings to do so as a ], a drawing of curves in the plane with crossings marked to indicate which curve or part of a curve passes above or below at each crossing. Such a drawing can be transformed into a system of curves in three-dimensional space by embedding the plane into space and deforming the curves drawn on it above or below the embedded plane at each crossing, as indicated in the diagram. The commonly-used diagram for the Borromean rings consists of three equal ]s centered at the points of an ], close enough together that their interiors have a common intersection (such as in a ] or the three circles used to define the ]). Its crossings ] between above and below when considered in consecutive order around each circle;{{r|imu|trinity|book}} another equivalent way to describe the over-under relation between the three circles is that each circle passes over a second circle at both of their crossings, and under the third circle at both of their crossings.{{r|roshambo}} Two links are said to be equivalent if there is a continuous deformation of space (an ]) taking one to another, and the Borromean rings may refer to any link that is equivalent in this sense to the standard diagram for this link.{{r|book}} | ||

| In '']'', the Borromean rings are denoted with the code "L6a4"; the notation means that this is a link with six crossings and an alternating diagram, the fourth of five alternating 6-crossing links identified by ] in a list of all ]s with up to 13 crossings.{{r|atlas}} In the tables of knots and links in Dale Rolfsen's 1976 book ''Knots and Links'', extending earlier listings in the 1920s by Alexander and Briggs, the Borromean rings were given the ] "6{{sup sub|3|2}}", meaning that this is the second of three 6-crossing 3-component links to be listed.{{r|atlas|rolfsen}} The ] for the Borromean rings, ".1", is an abbreviated description of the standard link diagram for this link.{{r|conway}} | In '']'', the Borromean rings are denoted with the code "L6a4"; the notation means that this is a link with six crossings and an alternating diagram, the fourth of five alternating 6-crossing links identified by ] in a list of all ]s with up to 13 crossings.{{r|atlas}} In the tables of knots and links in Dale Rolfsen's 1976 book ''Knots and Links'', extending earlier listings in the 1920s by Alexander and Briggs, the Borromean rings were given the ] "6{{sup sub|3|2}}", meaning that this is the second of three 6-crossing 3-component links to be listed.{{r|atlas|rolfsen}} The ] for the Borromean rings, ".1", is an abbreviated description of the standard link diagram for this link.{{r|conway}} | ||

| ==History and symbolism== | == History and symbolism == | ||

| {{multiple image|total_width= |

{{multiple image|total_width=400 | ||

| |image1=Sacrificial scene on Hammars - Valknut.png|caption1={{lang|non|]}} on ] | |image1=Sacrificial scene on Hammars - Valknut.png|caption1={{lang|non|]}} on ] | ||

| |image2=BorromeanRings-Trinity.svg|caption2= |

|image2=BorromeanRings-Trinity.svg|caption2=Symbol of the Christian ], adapted from a 13th-century manuscript | ||

| |image3=Three-triang-18crossings-Brunnian.svg|caption3= |

|image3=Three-triang-18crossings-Brunnian.svg|caption3=Linked triangles in the ] | ||

| }} | |||

| The name "Borromean rings" comes from the use of these rings, in the form of three linked circles, in the ] of the ] ] family in ].{{r|crumbrown|litcrit}} The link itself is much older and has appeared in the form of the {{lang|non|]}}, three linked ]s with parallel sides, on ] ]s dating back to the 7th century.{{r|mechbond}} The ] in Japan is also decorated with a motif of the Borromean rings, in their conventional circular form.{{r|imu}} A stone pillar in the 6th-century ] in India shows three equilateral triangles rotated from each other to form a regular ]; like the Borromean rings these three triangles are linked and not pairwise linked,{{r|enneagram}} but this crossing pattern describes a different link than the Borromean rings.{{r|rare}} | The name "Borromean rings" comes from the use of these rings, in the form of three linked circles, in the ] of the ] ] family in ].{{r|crumbrown|litcrit}} The link itself is much older and has appeared in the form of the {{lang|non|]}}, three linked ]s with parallel sides, on ] ]s dating back to the 7th century.{{r|mechbond}} The ] in Japan is also decorated with a motif of the Borromean rings, in their conventional circular form.{{r|imu}} A stone pillar in the 6th-century ] in India shows three equilateral triangles rotated from each other to form a regular ]; like the Borromean rings these three triangles are linked and not pairwise linked,{{r|enneagram}} but this crossing pattern describes a different link than the Borromean rings.{{r|rare}} | ||

| ] of the Borromean rings]] | ] of the Borromean rings]] | ||

| The Borromean rings have been used in different contexts to indicate strength in unity.{{r|ghz}} In particular, some have used the design to symbolize the ].{{r|trinity}} A 13th-century French manuscript depicting the Borromean rings labeled as unity in trinity was lost in a fire in the 1940s, but reproduced in an 1843 book by ]. Didron and others have speculated that the description of the Trinity as three equal circles in canto 33 of ]'s ] was inspired by similar images, although Dante does not detail the geometric arrangement of these circles.{{r|chartres|dante}} The psychoanalyst ] found inspiration in the Borromean rings as a model for his topology of human subjectivity, with each ring representing a fundamental Lacanian component of reality (the "real", the "imaginary", and the "symbolic").{{r|lacan}} | The Borromean rings have been used in different contexts to indicate strength in unity.{{r|ghz}} In particular, some have used the design to symbolize the ].{{r|trinity}} A 13th-century French manuscript depicting the Borromean rings labeled as unity in trinity was lost in a fire in the 1940s, but reproduced in an 1843 book by ]. Didron and others have speculated that the description of the Trinity as three equal circles in canto 33 of ]'s ] was inspired by similar images, although Dante does not detail the geometric arrangement of these circles.{{r|chartres|dante}} The psychoanalyst ] found inspiration in the Borromean rings as a model for his topology of human subjectivity, with each ring representing a fundamental Lacanian component of reality (the "real", the "imaginary", and the "symbolic").{{r|lacan}} | ||

| Line 54: | Line 57: | ||

| The first work of ] to include the Borromean rings was a catalog of knots and links compiled in 1876 by ].{{r|trinity}} In ], the Borromean rings were popularized by ], who featured ]s for the Borromean rings in his September 1961 "]" column in '']''.{{r|gardner}} In 2006, the ] decided at the ] in Madrid, Spain to use a new logo based on the Borromean rings.{{r|imu}} | The first work of ] to include the Borromean rings was a catalog of knots and links compiled in 1876 by ].{{r|trinity}} In ], the Borromean rings were popularized by ], who featured ]s for the Borromean rings in his September 1961 "]" column in '']''.{{r|gardner}} In 2006, the ] decided at the ] in Madrid, Spain to use a new logo based on the Borromean rings.{{r|imu}} | ||

| ===Partial and multiple rings=== | === Partial and multiple rings === | ||

| ] | |||

| In medieval and renaissance Europe, a number of visual signs consist of three elements interlaced together in the same way that the Borromean rings are shown interlaced (in their conventional two-dimensional depiction), but with individual elements that are not closed loops. Examples of such symbols are the ] horns{{r|unferth}} and the ] crescents.{{r|trinity}} | In medieval and renaissance Europe, a number of visual signs consist of three elements interlaced together in the same way that the Borromean rings are shown interlaced (in their conventional two-dimensional depiction), but with individual elements that are not closed loops. Examples of such symbols are the ] horns{{r|unferth}} and the ] crescents.{{r|trinity}} | ||

| Line 72: | Line 74: | ||

| {{Multiple image|total_width = 540 | {{Multiple image|total_width = 540 | ||

| |image1=3d borromean rings by ronbennett2001.jpg|caption1=Realization of Borromean rings using ellipses | |image1=3d borromean rings by ronbennett2001.jpg|caption1=Realization of Borromean rings using ellipses | ||

| |image2=Icosahedron-golden-rectangles.svg|caption2=Three linked ]s in a regular ]}} | |image2=Icosahedron-golden-rectangles.svg|caption2=Three linked ]s in a regular ] | ||

| }} | |||

| The Borromean rings are typically drawn with their rings projecting to circles in the plane of the drawing, but three-dimensional circular Borromean rings are an ]: it is not possible to form the Borromean rings from circles in three-dimensional space.{{r|book}} {{harvs|txt|first1=Michael H.|last1=Freedman|author1-link=Michael Freedman| first2=Richard| last2=Skora|year=1987}} proved |

The Borromean rings are typically drawn with their rings projecting to circles in the plane of the drawing, but three-dimensional circular Borromean rings are an ]: it is not possible to form the Borromean rings from circles in three-dimensional space.{{r|book}} More generally {{harvs|txt|first1=Michael H.|last1=Freedman|author1-link=Michael Freedman| first2=Richard| last2=Skora|year=1987}} proved using four-dimensional ] that no Brunnian link can be exactly circular.{{r|strange}} For three rings in their conventional Borromean arrangement, this can be seen from considering the ]. If one assumes that two of the circles touch at their two crossing points, then they lie in either a plane or a sphere. In either case, the third circle must pass through this plane or sphere four times, without lying in it, which is impossible.{{r|impossible}} Another argument for the impossibility of circular realizations, by ], uses ] to transform any three circles so that one of them becomes a line, making it easier to argue that the other two circles do not link with it to form the Borromean rings.{{r|inversive}} | ||

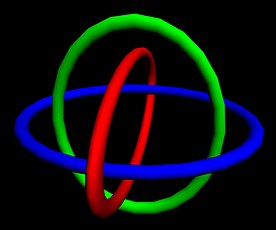

| However, the Borromean rings can be realized using ellipses.{{r|imu}} These may be taken to be of ] ] |

However, the Borromean rings can be realized using ellipses.{{r|imu}} These may be taken to be of ] ]: no matter how close to being circular their shape may be, as long as they are not perfectly circular, they can form Borromean links if suitably positioned. A realization of the Borromean rings by three mutually perpendicular ]s can be found within a regular ] by connecting three opposite pairs of its edges.{{r|imu}} Every three unknotted ]s in Euclidean space may be combined, after a suitable scaling transformation, to form the Borromean rings. If all three polygons are planar, then scaling is not needed.{{r|polygonal}} In particular, because the Borromean rings can be realized by three triangles, the minimum number of sides possible for each of its loops, the ] of the Borromean rings is nine.{{r|triangles}} | ||

| {{unsolved|mathematics|Are there three unknotted curves, not all circles, that cannot form the Borromean rings?}} | {{unsolved|mathematics|Are there three unknotted curves, not all circles, that cannot form the Borromean rings?}} | ||

| More generally, ] has ]d that any three unknotted simple closed curves in space, not all circles, can be combined without scaling to form the Borromean rings. After Jason Cantarella suggested a possible counterexample, Hugh Nelson Howards weakened the conjecture to apply to any three planar curves that are not all circles. On the other hand, although there are infinitely many Brunnian links with three links, the Borromean rings are the only one that can be formed from three convex curves.{{r|polygonal}} | More generally, ] has ]d that any three unknotted simple closed curves in space, not all circles, can be combined without scaling to form the Borromean rings. After Jason Cantarella suggested a possible counterexample, Hugh Nelson Howards weakened the conjecture to apply to any three planar curves that are not all circles. On the other hand, although there are infinitely many Brunnian links with three links, the Borromean rings are the only one that can be formed from three convex curves.{{r|polygonal}} | ||

| ===Ropelength=== | === Ropelength === | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| In knot theory, the ] of a knot or link |

In knot theory, the ] of a knot or link is the shortest length of flexible rope (of radius one) that can realize it. Mathematically, such a realization can be described by a smooth curve whose radius-one ] avoids self-intersections. The minimum ropelength of the Borromean rings has not been proven, but the smallest value that has been attained is realized by three copies of a 2-lobed planar curve.{{r|imu|criticality}} Although it resembles an earlier candidate for minimum ropelength, constructed from four ]s of radius two,{{r|4arc-rope}} it is slightly modified from that shape, and is composed from 42 smooth pieces defined by ]s, making it shorter by a fraction of a percent than the piecewise-circular realization. It is this realization, conjectured to minimize ropelength, that was used for the ] logo. Its length is <math>\approx 58.006</math>, while the best proven lower bound on the length is <math>12\pi\approx 37.699</math>.{{r|imu|criticality}} | ||

| For a discrete analogue of ropelength, the shortest representation using only edges of the ], the minimum length for the Borromean rings is exactly <math>36</math>. This is the length of a representation using three <math>2\times 4</math> integer rectangles, inscribed in ] in the same way that the representation by golden rectangles is inscribed in the regular icosahedron.{{r|lattice}} | For a discrete analogue of ropelength, the shortest representation using only edges of the ], the minimum length for the Borromean rings is exactly <math>36</math>. This is the length of a representation using three <math>2\times 4</math> integer rectangles, inscribed in ] in the same way that the representation by golden rectangles is inscribed in the regular icosahedron.{{r|lattice}} | ||

| === Hyperbolic geometry === | === Hyperbolic geometry === | ||

| ] of the Borromean rings, a |

] of the Borromean rings, a ] formed from two ideal octahedra, seen repeatedly in this view. The rings are infinitely far away, at the octahedron vertices.]] | ||

| The Borromean rings are a ]: the space surrounding the Borromean rings (their ]) admits a complete ] metric of finite volume. Although hyperbolic links are now considered plentiful, the Borromean rings were one of the earliest examples to be proved hyperbolic, in the 1970s,{{r|riley|ratcliffe}} and this link complement was a central example in the video '']'', produced in 1991 by the ].{{r|notknot}} | The Borromean rings are a ]: the space surrounding the Borromean rings (their ]) admits a complete ] metric of finite volume. Although hyperbolic links are now considered plentiful, the Borromean rings were one of the earliest examples to be proved hyperbolic, in the 1970s,{{r|riley|ratcliffe}} and this link complement was a central example in the video '']'', produced in 1991 by the ].{{r|notknot}} | ||

| Hyperbolic manifolds can be decomposed in a canonical way into gluings of hyperbolic polyhedra (the Epstein–Penner decomposition) and for the Borromean complement this decomposition consists of two ] ].{{r|ratcliffe|volume |

Hyperbolic manifolds can be decomposed in a canonical way into gluings of hyperbolic polyhedra (the Epstein–Penner decomposition) and for the Borromean complement this decomposition consists of two ] ].{{r|ratcliffe|volume}} The ] of the Borromean complement is <math>16\Lambda(\pi/4)=8G \approx 7.32772\dots</math> where <math>\Lambda</math> is the ] and <math>G</math> is ].{{r|volume}} The complement of the Borromean rings is universal, in the sense that every closed 3-] is a ] over this space.{{r|universal}} | ||

| === Number theory === | === Number theory === | ||

| In ], there is an analogy between ] and ]s in which one considers links between primes. The triple of primes {{nowrap|(13, 61, 937)}} are linked modulo 2 (the ] is −1) but are pairwise unlinked modulo 2 (the ]s are all 1). Therefore, these primes have been called a "proper Borromean triple modulo 2"{{r|massey}} or "mod 2 Borromean primes".{{r|analogies}} | In ], there is an analogy between ] and ]s in which one considers links between primes. The triple of primes {{nowrap|(13, 61, 937)}} are linked modulo 2 (the ] is −1) but are pairwise unlinked modulo 2 (the ]s are all 1). Therefore, these primes have been called a "proper Borromean triple modulo 2"{{r|massey}} or "mod 2 Borromean primes".{{r|analogies}} | ||

| ==Physical realizations== | == Physical realizations == | ||

| {{multiple image |

{{multiple image | ||

| |image1=Knot Monkey Fist.jpg|caption1=A ] knot | | image1 = Knot Monkey Fist.jpg | ||

| | caption1 = A ] knot | |||

| | image2 = Borromean ring knitting.png | |||

| |image2=Molecular Borromean Rings Atwood Stoddart commons.png|caption2=Crystal structure of ]{{r|stoddart}}}} | |||

| | caption2 = Borromean ring knitting project by knot theorist ] | |||

| | image3 = Molecular Borromean Rings Atwood Stoddart commons.png | |||

| | caption3 = ]{{r|stoddart}} | |||

| | total_width = 500 | |||

| }} | |||

| A ] knot is essentially a 3-dimensional representation of the Borromean rings, albeit with three layers, in most cases.{{r|ashley}} Sculptor ] has made artworks with three ]s made out of ], linked to form Borromean rings and resembling a three-dimensional version of the valknut.{{r|rare|triangles}} A common design for a folding wooden tripod consists of three pieces carved from a single piece of wood, with each piece consisting of two lengths of wood, the legs and upper sides of the tripod, connected by two segments of wood that surround an elongated central hole in the piece. Another of the three pieces passes through each of these holes, linking the three pieces together in the Borromean rings pattern. Tripods of this form have been described as coming from Indian or African hand crafts.{{r|tripod1|tripod2}} | A ] knot is essentially a 3-dimensional representation of the Borromean rings, albeit with three layers, in most cases.{{r|ashley}} Sculptor ] has made artworks with three ]s made out of ], linked to form Borromean rings and resembling a three-dimensional version of the valknut.{{r|rare|triangles}} A common design for a folding wooden tripod consists of three pieces carved from a single piece of wood, with each piece consisting of two lengths of wood, the legs and upper sides of the tripod, connected by two segments of wood that surround an elongated central hole in the piece. Another of the three pieces passes through each of these holes, linking the three pieces together in the Borromean rings pattern. Tripods of this form have been described as coming from Indian or African hand crafts.{{r|tripod1|tripod2}} | ||

| In chemistry, ] are the molecular counterparts of Borromean rings, which are ]. In 1997, biologist Chengde Mao and coworkers of ] succeeded in constructing a set of rings from ].{{r|dna}} In 2003, ] ] and coworkers at ] utilised ] to construct a set of rings in one step from 18 components.{{r|stoddart}} Borromean ring structures have been used to describe noble metal clusters shielded by a surface layer of thiolate ligands.{{r|thiolate}} A library of Borromean networks has been synthesized by design by ] and coworkers via ] driven ].{{r|halogen}} In order to access the molecular Borromean ring consisting of three unequal cycles a step-by-step synthesis was proposed by Jay S. Siegel and coworkers.{{r|unequal}} | In chemistry, ] are the molecular counterparts of Borromean rings, which are ]. In 1997, biologist Chengde Mao and coworkers of ] succeeded in constructing a set of rings from ].{{r|dna}} In 2003, ] ] and coworkers at ] utilised ] to construct a set of rings in one step from 18 components.{{r|stoddart}} Borromean ring structures have been used to describe noble metal clusters shielded by a surface layer of thiolate ligands.{{r|thiolate}} A library of Borromean networks has been synthesized by design by ] and coworkers via ] driven ].{{r|halogen}} In order to access the molecular Borromean ring consisting of three unequal cycles a step-by-step synthesis was proposed by Jay S. Siegel and coworkers.{{r|unequal}} | ||

| ⚫ | In physics, a quantum-mechanical analog of Borromean rings is called a halo state or an ], and consists of three bound particles that are not pairwise bound. The existence of such states was predicted by physicist ] in 1970, and confirmed by multiple experiments beginning in 2006.{{r|efimov|physical}} This phenomenon is closely related to a ], a stable atomic nucleus consisting of three groups of particles that would be unstable in pairs.{{r|nucleus}} Another analog of the Borromean rings in ] involves the entanglement of three ]s in the ].{{r|ghz}} | ||

| == Notes == | |||

| ⚫ | In physics, a quantum-mechanical analog of Borromean rings is called a halo state or an ], and consists of three bound particles that are not pairwise bound.The existence of such states was predicted by physicist ] |

||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | == References == | ||

| {{reflist|refs= | {{reflist|refs= | ||

| <ref name=atlas>{{Knot Atlas|L6a4|Borromean rings}}</ref> |

<ref name=atlas>{{Knot Atlas|L6a4|Borromean rings}}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=notknot>{{citation | <ref name=notknot>{{citation | ||

| Line 120: | Line 132: | ||

| | pages = 340–342 | | pages = 340–342 | ||

| | title = Review of ''Not Knot'' and ''Supplement to Not Knot'' | | title = Review of ''Not Knot'' and ''Supplement to Not Knot'' | ||

| | volume = 81 |

| volume = 81| s2cid = 64589738 | ||

| ⚫ | }}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=book>{{citation|contribution=Chapter 15: The Borromean Rings Don't Exist|title=Proofs from THE BOOK|title-link=Proofs from THE BOOK|pages=99–106|first1=Martin|last1=Aigner|author1-link=Martin Aigner|first2=Günter M.|last2=Ziegler|author2-link=Günter M. Ziegler|edition=6th|publisher=Springer|doi=10.1007/978-3-662-57265-8_15|isbn=978-3-662-57265-8|year=2018}}</ref> | <ref name=book>{{citation|contribution=Chapter 15: The Borromean Rings Don't Exist|title=Proofs from THE BOOK|title-link=Proofs from THE BOOK|pages=99–106|first1=Martin|last1=Aigner|author1-link=Martin Aigner|first2=Günter M.|last2=Ziegler|author2-link=Günter M. Ziegler|edition=6th|publisher=Springer|doi=10.1007/978-3-662-57265-8_15|isbn=978-3-662-57265-8|year=2018}}</ref> | ||

| Line 139: | Line 152: | ||

| | year = 1997}}</ref> | | year = 1997}}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=ashley>{{citation|title=The Ashley Book of Knots|page=354|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QaSBVuPK9H0C |

<ref name=ashley>{{citation|title=The Ashley Book of Knots|page=354|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QaSBVuPK9H0C&pg=PA354|first=Clifford Warren|last=Ashley|publisher=Doubleday|year=1993|isbn=978-0-385-04025-9|orig-year=1944}}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=brunnian>{{citation | <ref name=brunnian>{{citation | ||

| Line 147: | Line 160: | ||

| | doi = 10.1142/S0218216520430087 | | doi = 10.1142/S0218216520430087 | ||

| | issue = 13 | | issue = 13 | ||

| | journal = ] | | journal = ] | ||

| | mr = 4213076 | | mr = 4213076 | ||

| | |

| pages = 2043008, 27 | ||

| | title = New criteria and constructions of Brunnian links | | title = New criteria and constructions of Brunnian links | ||

| | volume = 29 | | volume = 29 | ||

| | year = 2020 |

| year = 2020| s2cid = 219792382 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=unferth>{{citation | <ref name=unferth>{{citation | ||

| Line 177: | Line 191: | ||

| | title = Beauty in Chemistry | | title = Beauty in Chemistry | ||

| | volume = 323 | | volume = 323 | ||

| | year = 2011 |

| year = 2011| pmid = 22183145 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=triangles>{{citation | <ref name=triangles>{{citation | ||

| Line 205: | Line 220: | ||

| | pages = 2055–2116 | | pages = 2055–2116 | ||

| | title = Criticality for the Gehring link problem | | title = Criticality for the Gehring link problem | ||

| | url = http://www.jasoncantarella.com/downloads/papers/ropcrit/gehrcrit_final.pdf | |||

| | volume = 10 | | volume = 10 | ||

| | year = 2006}}</ref> | | year = 2006| issue = 4 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=4arc-rope>{{citation | <ref name=4arc-rope>{{citation | ||

| Line 218: | Line 235: | ||

| | pages = 257–286 | | pages = 257–286 | ||

| | title = On the minimum ropelength of knots and links | | title = On the minimum ropelength of knots and links | ||

| | url = http://www.jasoncantarella.com/downloads/papers/ropelength/ropelen.pdf | |||

| | volume = 150 | | volume = 150 | ||

| | year = 2002 |

| year = 2002| arxiv = math/0103224 | ||

| | bibcode = 2002InMat.150..257C | |||

| | s2cid = 730891 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=roshambo>{{citation | <ref name=roshambo>{{citation | ||

| Line 231: | Line 252: | ||

| | title = Rock-paper-scissors meets Borromean rings | | title = Rock-paper-scissors meets Borromean rings | ||

| | volume = 37 | | volume = 37 | ||

| | year = 2015 |

| year = 2015| s2cid = 558993 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=stoddart>{{citation | <ref name=stoddart>{{citation | ||

| Line 250: | Line 272: | ||

| | title = Molecular Borromean rings | | title = Molecular Borromean rings | ||

| | url = https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/22968/1/196491_534%20Cave%20PostPrint.pdf | | url = https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/22968/1/196491_534%20Cave%20PostPrint.pdf | ||

| | volume = 304 |

| volume = 304| s2cid = 45191675 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=conway>{{citation | <ref name=conway>{{citation | ||

| Line 272: | Line 295: | ||

| | pages = 53–62 | | pages = 53–62 | ||

| | title = The Borromean rings | | title = The Borromean rings | ||

| | volume = 20 |

| volume = 20| s2cid = 189888135 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=crumbrown>{{citation | <ref name=crumbrown>{{citation | ||

| Line 301: | Line 325: | ||

| | title = Strange actions of groups on spheres | | title = Strange actions of groups on spheres | ||

| | volume = 25 | | volume = 25 | ||

| | year = 1987}}</ref> | | year = 1987}}; see in particular Lemma 3.2, p. 89</ref> | ||

| <ref name=tripod1>{{citation | <ref name=tripod1>{{citation | ||

| Line 307: | Line 331: | ||

| | journal = Tewkesbury Historical Society Bulletin | | journal = Tewkesbury Historical Society Bulletin | ||

| | title = Gathering clues from Margot's extraordinary objects | | title = Gathering clues from Margot's extraordinary objects | ||

| | url = https://www.researchgate.net |

| url = https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272791124 | ||

| | volume = 24 | | volume = 24 | ||

| | year = 2015}}</ref> | | year = 2015}}</ref> | ||

| Line 331: | Line 355: | ||

| | pages = 15–16 | | pages = 15–16 | ||

| | title = The 3-ring symbol of Ballantine Beer | | title = The 3-ring symbol of Ballantine Beer | ||

| | volume = 21 |

| volume = 21| s2cid = 123311380 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=uniform>{{citation | |||

| | last = Görner | first = Matthias | |||

| | arxiv = 1406.2827 | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/10586458.2014.986310 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | mr = 3350527 | |||

| | pages = 225–246 | |||

| | title = Regular tessellation link complements | |||

| | volume = 24 | |||

| ⚫ | |

||

| <ref name=imu>{{citation | <ref name=imu>{{citation | ||

| | last1 = Gunn |

| last1 = Gunn | ||

| | first1 = Charles | |||

| | last2 = Sullivan |

| last2 = Sullivan | ||

| | first2 = John M. | |||

| | author2-link = John M. Sullivan (mathematician) | |||

| | editor1-last = Sarhangi |

| editor1-last = Sarhangi | ||

| | editor1-first = Reza | |||

| | editor2-last = Séquin |

| editor2-last = Séquin | ||

| | editor2-first = Carlo H. | |||

| | editor2-link = Carlo H. Séquin | |||

| | contribution = The Borromean Rings: A video about the New IMU logo | | contribution = The Borromean Rings: A video about the New IMU logo | ||

| | contribution-url = https://archive.bridgesmathart.org/2008/bridges2008-63.html | | contribution-url = https://archive.bridgesmathart.org/2008/bridges2008-63.html | ||

| | isbn = |

| isbn = 978-0-9665201-9-4 | ||

| | location = London | | location = London | ||

| | pages = 63–70 | | pages = 63–70 | ||

| | publisher = Tarquin Publications | | publisher = Tarquin Publications | ||

| | title = Bridges Leeuwarden: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture | | title = Bridges Leeuwarden: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture | ||

| | year = 2008 | |||

| |

}}; see the video itself at " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308065039/http://torus.math.uiuc.edu/jms/Videos/imu/ |date=2021-03-08 }}" , ''International Mathematical Union''</ref> | ||

| <ref name=universal>{{citation | <ref name=universal>{{citation | ||

| Line 376: | Line 396: | ||

| | doi = 10.1142/S0218216513500831 | | doi = 10.1142/S0218216513500831 | ||

| | issue = 14 | | issue = 14 | ||

| | journal = ] | | journal = ] | ||

| | mr = 3190121 | | mr = 3190121 | ||

| | |

| pages = 1350083, 15 | ||

| | title = Forming the Borromean rings out of arbitrary polygonal unknots | | title = Forming the Borromean rings out of arbitrary polygonal unknots | ||

| | volume = 22 | | volume = 22 | ||

| | year = 2013 |

| year = 2013| s2cid = 119674622 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=rare>{{citation | <ref name=rare>{{citation | ||

| Line 416: | Line 437: | ||

| | title = Evidence for Efimov quantum states in an ultracold gas of caesium atoms | | title = Evidence for Efimov quantum states in an ultracold gas of caesium atoms | ||

| | volume = 440 | | volume = 440 | ||

| | year = 2006 |

| year = 2006| s2cid = 4379828 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=halogen>{{citation | <ref name=halogen>{{citation | ||

| Line 443: | Line 465: | ||

| | pages = 41–47 | | pages = 41–47 | ||

| | title = Borromean triangles and prime knots in an ancient temple | | title = Borromean triangles and prime knots in an ancient temple | ||

| | volume = 12 |

| volume = 12| s2cid = 120259064 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=impossible>{{citation | <ref name=impossible>{{citation | ||

| Line 469: | Line 492: | ||

| | title = Assembly of Borromean rings from DNA | | title = Assembly of Borromean rings from DNA | ||

| | volume = 386 | | volume = 386 | ||

| | year = 1997 |

| year = 1997| s2cid = 4321733 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=analogies>{{citation | <ref name=analogies>{{citation | ||

| Line 483: | Line 507: | ||

| <ref name=physical>{{citation | <ref name=physical>{{citation | ||

| | last = Moskowitz | first = Clara | | last = Moskowitz | first = Clara | author-link = Clara Moskowitz | ||

| | date = December 16, 2009 | | date = December 16, 2009 | ||

| | title = Strange physical theory proved after nearly 40 years | | title = Strange physical theory proved after nearly 40 years | ||

| Line 500: | Line 524: | ||

| | volume = 100}}</ref> | | volume = 100}}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=thiolate>{{citation | |

<ref name=thiolate>{{citation |last1=Natarajan |first1=Ganapati |last2=Mathew |first2=Ammu |last3=Negishi |first3=Yuichi |last4=Whetten |first4=Robert L. |last5=Pradeep |first5=Thalappil |date=2015-12-02 |title=A unified framework for understanding the structure and modifications of atomically precise monolayer protected gold clusters|journal=] |volume=119|issue=49|pages=27768–27785|doi=10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b08193|issn=1932-7447}}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=discord>{{citation|title=Principia Discordia|title-link=Principia Discordia|edition=4th|page=43|contribution=Mandala|contribution-url=https://archive.org/details/principiadiscordia/page/n45/mode/2up|date=March 1970}}</ref> | <ref name=discord>{{citation|title=Principia Discordia|title-link=Principia Discordia|edition=4th|page=43|contribution=Mandala|contribution-url=https://archive.org/details/principiadiscordia/page/n45/mode/2up|date=March 1970}}</ref> | ||

| Line 509: | Line 533: | ||

| | contribution = Introduction: Topologically Speaking | | contribution = Introduction: Topologically Speaking | ||

| | contribution-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ap79_4DZpjwC&pg=PR13 | | contribution-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ap79_4DZpjwC&pg=PR13 | ||

| | isbn = |

| isbn = 978-1-892746-76-4 | ||

| | publisher = Other Press | | publisher = Other Press | ||

| | title = Lacan: Topologically Speaking | | title = Lacan: Topologically Speaking | ||

| Line 519: | Line 543: | ||

| | contribution-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=JV9m8o-ok6YC&pg=PA459 | | contribution-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=JV9m8o-ok6YC&pg=PA459 | ||

| | edition = 2nd | | edition = 2nd | ||

| | isbn = 978- |

| isbn = 978-0-387-33197-3 | ||

| | mr = 2249478 | | mr = 2249478 | ||

| | pages = 459–461 | | pages = 459–461 | ||

| Line 539: | Line 563: | ||

| | title = Topology of Low-Dimensional Manifolds: Proceedings of the Second Sussex Conference, 1977 | | title = Topology of Low-Dimensional Manifolds: Proceedings of the Second Sussex Conference, 1977 | ||

| | volume = 722 | | volume = 722 | ||

| | year = 1979}}</ref> | | isbn = 978-3-540-09506-4 | year = 1979}}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=rolfsen>{{citation | <ref name=rolfsen>{{citation | ||

| Line 586: | Line 610: | ||

| | title = Observation of a Large Reaction Cross Section in the Drip-Line Nucleus <sup>22</sup>C | | title = Observation of a Large Reaction Cross Section in the Drip-Line Nucleus <sup>22</sup>C | ||

| | volume = 104 | | volume = 104 | ||

| | year = 2010 |

| year = 2010| s2cid = 7951719 | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=algebraic>{{citation | <ref name=algebraic>{{citation | ||

| Line 597: | Line 622: | ||

| | url = https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.pjm/1102637085 | | url = https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.pjm/1102637085 | ||

| | volume = 151 | | volume = 151 | ||

| | year = 1991 |

| year = 1991| doi = 10.2140/pjm.1991.151.317 | doi-access = free | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=volume>{{Citation |author=William Thurston|author-link=William Thurston |date=March 2002 |title=The Geometry and Topology of Three-Manifolds |url=http://library.msri.org/books/gt3m/ |chapter=7. Computation of volume |chapter-url=http://library.msri.org/books/gt3m/PDF/7.pdf |page=165}}</ref> | <ref name=volume>{{Citation |author=William Thurston |author-link=William Thurston |date=March 2002 |title=The Geometry and Topology of Three-Manifolds |url=http://library.msri.org/books/gt3m/ |chapter=7. Computation of volume |chapter-url=http://library.msri.org/books/gt3m/PDF/7.pdf |page=165 |access-date=2012-01-17 |archive-date=2020-07-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727020107/http://library.msri.org/books/gt3m/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=inversive>{{citation | <ref name=inversive>{{citation | ||

| | last = Tverberg |

| last = Tverberg | ||

| | first = Helge | |||

| | author-link = Helge Tverberg | |||

| | issue = 1 | | issue = 1 | ||

| | journal = ] | | journal = ] | ||

| Line 610: | Line 638: | ||

| | url = http://www.appliedprobability.org/data/files/TMS%20articles/35_1_9.pdf | | url = http://www.appliedprobability.org/data/files/TMS%20articles/35_1_9.pdf | ||

| | volume = 35 | | volume = 35 | ||

| | year = 2010 |

| year = 2010 | ||

| | access-date = 2021-03-16 | |||

| | archive-date = 2021-03-16 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210316044542/http://www.appliedprobability.org/data/files/TMS%20articles/35_1_9.pdf | |||

| | url-status = dead | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=lattice>{{citation | <ref name=lattice>{{citation | ||

| Line 632: | Line 665: | ||

| | year = 1998}}; see Table 2, p. 97</ref> | | year = 1998}}; see Table 2, p. 97</ref> | ||

| <ref name=unequal>{{citation |last1=Veliks |first1=Janis |last2=Seifert |first2=Helen M. |last3=Frantz |first3=Derik K. |last4=Klosterman |first4=Jeremy K. |last5=Tseng |first5=Jui-Chang |last6=Linden |first6=Anthony |last7=Siegel |first7=Jay S. |title=Towards the molecular Borromean link with three unequal rings: double-threaded ruthenium(ii) ring-in-ring complexes |journal=Organic Chemistry Frontiers |date=2016 |volume=3 |issue=6 |pages=667–672 |doi=10.1039/c6qo00025h |

<ref name=unequal>{{citation |last1=Veliks |first1=Janis |last2=Seifert |first2=Helen M. |last3=Frantz |first3=Derik K. |last4=Klosterman |first4=Jeremy K. |last5=Tseng |first5=Jui-Chang |last6=Linden |first6=Anthony |last7=Siegel |first7=Jay S. |title=Towards the molecular Borromean link with three unequal rings: double-threaded ruthenium(ii) ring-in-ring complexes |journal=Organic Chemistry Frontiers |date=2016 |volume=3 |issue=6 |pages=667–672 |doi=10.1039/c6qo00025h |doi-access=free }}</ref> | ||

| <ref name=massey>{{Citation |first=Denis|last= Vogel|year=2005 |title=Masseyprodukte in der Galoiskohomologie von Zahlkörpern|trans-title=Massey products in the Galois cohomology of number fields |url=http://www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/archiv/4418 |doi=10.11588/heidok.00004418|series=Mathematisches Institut, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen: Seminars Winter Term 2004/2005|pages= 93–98| publisher=Universitätsdrucke Göttingen|location= Göttingen|mr=2206880}}</ref> | <ref name=massey>{{Citation |first=Denis|last= Vogel|year=2005 |title=Masseyprodukte in der Galoiskohomologie von Zahlkörpern|trans-title=Massey products in the Galois cohomology of number fields |url=http://www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/archiv/4418 |doi=10.11588/heidok.00004418|series=Mathematisches Institut, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen: Seminars Winter Term 2004/2005|pages= 93–98| publisher=Universitätsdrucke Göttingen|location= Göttingen|mr=2206880}}</ref> | ||

| Line 638: | Line 671: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| ==External links== | == External links == | ||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| {{Commonscat}} | |||

| * {{citation|url=https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/roots-of-unity/a-few-of-my-favorite-spaces-borromean-rings/|title=A few of my favorite spaces: Borromean rings|department=Roots of Unity|magazine=Scientific American|first=Evelyn|last=Lamb|date=September 30, 2016}} | * {{citation|url=https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/roots-of-unity/a-few-of-my-favorite-spaces-borromean-rings/|title=A few of my favorite spaces: Borromean rings|department=Roots of Unity|magazine=]|first=Evelyn|last=Lamb|date=September 30, 2016}} | ||

| * (], 2012), (], 2016), and (], 2018), ] | * (], 2012), (], 2016), and (], 2018), ] | ||

| * {{citation|url=https://www.mathunion.org/outreach/imu-logo/borromean-rings|title=Borromean Rings|publisher=International Mathematical Union}} | |||

| {{Knot theory|state=collapsed}} | {{Knot theory|state=collapsed}} | ||

Latest revision as of 11:29, 20 October 2024

Three linked but pairwise separated rings

| Borromean rings | |

|---|---|

L6a4 L6a4 | |

| Crossing no. | 6 |

| Hyperbolic volume | 7.327724753 |

| Stick no. | 9 |

| Conway notation | .1 |

| A–B notation | 6 2 |

| Thistlethwaite | L6a4 |

| Other | |

| alternating, hyperbolic | |

In mathematics, the Borromean rings are three simple closed curves in three-dimensional space that are topologically linked and cannot be separated from each other, but that break apart into two unknotted and unlinked loops when any one of the three is cut or removed. Most commonly, these rings are drawn as three circles in the plane, in the pattern of a Venn diagram, alternatingly crossing over and under each other at the points where they cross. Other triples of curves are said to form the Borromean rings as long as they are topologically equivalent to the curves depicted in this drawing.

The Borromean rings are named after the Italian House of Borromeo, who used the circular form of these rings as an element of their coat of arms, but designs based on the Borromean rings have been used in many cultures, including by the Norsemen and in Japan. They have been used in Christian symbolism as a sign of the Trinity, and in modern commerce as the logo of Ballantine beer, giving them the alternative name Ballantine rings. Physical instances of the Borromean rings have been made from linked DNA or other molecules, and they have analogues in the Efimov state and Borromean nuclei, both of which have three components bound to each other although no two of them are bound.

Geometrically, the Borromean rings may be realized by linked ellipses, or (using the vertices of a regular icosahedron) by linked golden rectangles. It is impossible to realize them using circles in three-dimensional space, but it has been conjectured that they may be realized by copies of any non-circular simple closed curve in space. In knot theory, the Borromean rings can be proved to be linked by counting their Fox n-colorings. As links, they are Brunnian, alternating, algebraic, and hyperbolic. In arithmetic topology, certain triples of prime numbers have analogous linking properties to the Borromean rings.

Definition and notation

It is common in mathematics publications that define the Borromean rings to do so as a link diagram, a drawing of curves in the plane with crossings marked to indicate which curve or part of a curve passes above or below at each crossing. Such a drawing can be transformed into a system of curves in three-dimensional space by embedding the plane into space and deforming the curves drawn on it above or below the embedded plane at each crossing, as indicated in the diagram. The commonly-used diagram for the Borromean rings consists of three equal circles centered at the points of an equilateral triangle, close enough together that their interiors have a common intersection (such as in a Venn diagram or the three circles used to define the Reuleaux triangle). Its crossings alternate between above and below when considered in consecutive order around each circle; another equivalent way to describe the over-under relation between the three circles is that each circle passes over a second circle at both of their crossings, and under the third circle at both of their crossings. Two links are said to be equivalent if there is a continuous deformation of space (an ambient isotopy) taking one to another, and the Borromean rings may refer to any link that is equivalent in this sense to the standard diagram for this link.

In The Knot Atlas, the Borromean rings are denoted with the code "L6a4"; the notation means that this is a link with six crossings and an alternating diagram, the fourth of five alternating 6-crossing links identified by Morwen Thistlethwaite in a list of all prime links with up to 13 crossings. In the tables of knots and links in Dale Rolfsen's 1976 book Knots and Links, extending earlier listings in the 1920s by Alexander and Briggs, the Borromean rings were given the Alexander–Briggs notation "6

2", meaning that this is the second of three 6-crossing 3-component links to be listed. The Conway notation for the Borromean rings, ".1", is an abbreviated description of the standard link diagram for this link.

History and symbolism

Valknut on Stora Hammars I stone

Valknut on Stora Hammars I stone Symbol of the Christian Trinity, adapted from a 13th-century manuscript

Symbol of the Christian Trinity, adapted from a 13th-century manuscript Linked triangles in the Marundeeswarar Temple

Linked triangles in the Marundeeswarar Temple

The name "Borromean rings" comes from the use of these rings, in the form of three linked circles, in the coat of arms of the aristocratic Borromeo family in Northern Italy. The link itself is much older and has appeared in the form of the valknut, three linked equilateral triangles with parallel sides, on Norse image stones dating back to the 7th century. The Ōmiwa Shrine in Japan is also decorated with a motif of the Borromean rings, in their conventional circular form. A stone pillar in the 6th-century Marundeeswarar Temple in India shows three equilateral triangles rotated from each other to form a regular enneagram; like the Borromean rings these three triangles are linked and not pairwise linked, but this crossing pattern describes a different link than the Borromean rings.

The Borromean rings have been used in different contexts to indicate strength in unity. In particular, some have used the design to symbolize the Trinity. A 13th-century French manuscript depicting the Borromean rings labeled as unity in trinity was lost in a fire in the 1940s, but reproduced in an 1843 book by Adolphe Napoléon Didron. Didron and others have speculated that the description of the Trinity as three equal circles in canto 33 of Dante's Paradiso was inspired by similar images, although Dante does not detail the geometric arrangement of these circles. The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan found inspiration in the Borromean rings as a model for his topology of human subjectivity, with each ring representing a fundamental Lacanian component of reality (the "real", the "imaginary", and the "symbolic").

The rings were used as the logo of Ballantine beer, and are still used by the Ballantine brand beer, now distributed by the current brand owner, the Pabst Brewing Company. For this reason they have sometimes been called the "Ballantine rings".

The first work of knot theory to include the Borromean rings was a catalog of knots and links compiled in 1876 by Peter Tait. In recreational mathematics, the Borromean rings were popularized by Martin Gardner, who featured Seifert surfaces for the Borromean rings in his September 1961 "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific American. In 2006, the International Mathematical Union decided at the 25th International Congress of Mathematicians in Madrid, Spain to use a new logo based on the Borromean rings.

Partial and multiple rings

In medieval and renaissance Europe, a number of visual signs consist of three elements interlaced together in the same way that the Borromean rings are shown interlaced (in their conventional two-dimensional depiction), but with individual elements that are not closed loops. Examples of such symbols are the Snoldelev stone horns and the Diana of Poitiers crescents.

Some knot-theoretic links contain multiple Borromean rings configurations; one five-loop link of this type is used as a symbol in Discordianism, based on a depiction in the Principia Discordia.

Mathematical properties

Linkedness

In knot theory, the Borromean rings are a simple example of a Brunnian link, a link that cannot be separated but that falls apart into separate unknotted loops as soon as any one of its components is removed. There are infinitely many Brunnian links, and infinitely many three-curve Brunnian links, of which the Borromean rings are the simplest.

There are a number of ways of seeing that the Borromean rings are linked. One is to use Fox n-colorings, colorings of the arcs of a link diagram with the integers modulo n so that at each crossing, the two colors at the undercrossing have the same average (modulo n) as the color of the overcrossing arc, and so that at least two colors are used. The number of colorings meeting these conditions is a knot invariant, independent of the diagram chosen for the link. A trivial link with three components has colorings, obtained from its standard diagram by choosing a color independently for each component and discarding the colorings that only use one color. For standard diagram of the Borromean rings, on the other hand, the same pairs of arcs meet at two undercrossings, forcing the arcs that cross over them to have the same color as each other, from which it follows that the only colorings that meet the crossing conditions violate the condition of using more than one color. Because the trivial link has many valid colorings and the Borromean rings have none, they cannot be equivalent.

The Borromean rings are an alternating link, as their conventional link diagram has crossings that alternate between passing over and under each curve, in order along the curve. They are also an algebraic link, a link that can be decomposed by Conway spheres into 2-tangles. They are the simplest alternating algebraic link which does not have a diagram that is simultaneously alternating and algebraic. It follows from the Tait conjectures that the crossing number of the Borromean rings (the fewest crossings in any of their link diagrams) is 6, the number of crossings in their alternating diagram.

Ring shape

Realization of Borromean rings using ellipses

Realization of Borromean rings using ellipses Three linked golden rectangles in a regular icosahedron

Three linked golden rectangles in a regular icosahedron

The Borromean rings are typically drawn with their rings projecting to circles in the plane of the drawing, but three-dimensional circular Borromean rings are an impossible object: it is not possible to form the Borromean rings from circles in three-dimensional space. More generally Michael H. Freedman and Richard Skora (1987) proved using four-dimensional hyperbolic geometry that no Brunnian link can be exactly circular. For three rings in their conventional Borromean arrangement, this can be seen from considering the link diagram. If one assumes that two of the circles touch at their two crossing points, then they lie in either a plane or a sphere. In either case, the third circle must pass through this plane or sphere four times, without lying in it, which is impossible. Another argument for the impossibility of circular realizations, by Helge Tverberg, uses inversive geometry to transform any three circles so that one of them becomes a line, making it easier to argue that the other two circles do not link with it to form the Borromean rings.

However, the Borromean rings can be realized using ellipses. These may be taken to be of arbitrarily small eccentricity: no matter how close to being circular their shape may be, as long as they are not perfectly circular, they can form Borromean links if suitably positioned. A realization of the Borromean rings by three mutually perpendicular golden rectangles can be found within a regular icosahedron by connecting three opposite pairs of its edges. Every three unknotted polygons in Euclidean space may be combined, after a suitable scaling transformation, to form the Borromean rings. If all three polygons are planar, then scaling is not needed. In particular, because the Borromean rings can be realized by three triangles, the minimum number of sides possible for each of its loops, the stick number of the Borromean rings is nine.

Unsolved problem in mathematics: Are there three unknotted curves, not all circles, that cannot form the Borromean rings? (more unsolved problems in mathematics)More generally, Matthew Cook has conjectured that any three unknotted simple closed curves in space, not all circles, can be combined without scaling to form the Borromean rings. After Jason Cantarella suggested a possible counterexample, Hugh Nelson Howards weakened the conjecture to apply to any three planar curves that are not all circles. On the other hand, although there are infinitely many Brunnian links with three links, the Borromean rings are the only one that can be formed from three convex curves.

Ropelength

In knot theory, the ropelength of a knot or link is the shortest length of flexible rope (of radius one) that can realize it. Mathematically, such a realization can be described by a smooth curve whose radius-one tubular neighborhood avoids self-intersections. The minimum ropelength of the Borromean rings has not been proven, but the smallest value that has been attained is realized by three copies of a 2-lobed planar curve. Although it resembles an earlier candidate for minimum ropelength, constructed from four circular arcs of radius two, it is slightly modified from that shape, and is composed from 42 smooth pieces defined by elliptic integrals, making it shorter by a fraction of a percent than the piecewise-circular realization. It is this realization, conjectured to minimize ropelength, that was used for the International Mathematical Union logo. Its length is , while the best proven lower bound on the length is .

For a discrete analogue of ropelength, the shortest representation using only edges of the integer lattice, the minimum length for the Borromean rings is exactly . This is the length of a representation using three integer rectangles, inscribed in Jessen's icosahedron in the same way that the representation by golden rectangles is inscribed in the regular icosahedron.

Hyperbolic geometry

The Borromean rings are a hyperbolic link: the space surrounding the Borromean rings (their link complement) admits a complete hyperbolic metric of finite volume. Although hyperbolic links are now considered plentiful, the Borromean rings were one of the earliest examples to be proved hyperbolic, in the 1970s, and this link complement was a central example in the video Not Knot, produced in 1991 by the Geometry Center.

Hyperbolic manifolds can be decomposed in a canonical way into gluings of hyperbolic polyhedra (the Epstein–Penner decomposition) and for the Borromean complement this decomposition consists of two ideal regular octahedra. The volume of the Borromean complement is where is the Lobachevsky function and is Catalan's constant. The complement of the Borromean rings is universal, in the sense that every closed 3-manifold is a branched cover over this space.

Number theory

In arithmetic topology, there is an analogy between knots and prime numbers in which one considers links between primes. The triple of primes (13, 61, 937) are linked modulo 2 (the Rédei symbol is −1) but are pairwise unlinked modulo 2 (the Legendre symbols are all 1). Therefore, these primes have been called a "proper Borromean triple modulo 2" or "mod 2 Borromean primes".

Physical realizations

A monkey's fist knot

A monkey's fist knot Borromean ring knitting project by knot theorist Laura Taalman

Borromean ring knitting project by knot theorist Laura Taalman Molecular Borromean rings

Molecular Borromean rings

A monkey's fist knot is essentially a 3-dimensional representation of the Borromean rings, albeit with three layers, in most cases. Sculptor John Robinson has made artworks with three equilateral triangles made out of sheet metal, linked to form Borromean rings and resembling a three-dimensional version of the valknut. A common design for a folding wooden tripod consists of three pieces carved from a single piece of wood, with each piece consisting of two lengths of wood, the legs and upper sides of the tripod, connected by two segments of wood that surround an elongated central hole in the piece. Another of the three pieces passes through each of these holes, linking the three pieces together in the Borromean rings pattern. Tripods of this form have been described as coming from Indian or African hand crafts.

In chemistry, molecular Borromean rings are the molecular counterparts of Borromean rings, which are mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures. In 1997, biologist Chengde Mao and coworkers of New York University succeeded in constructing a set of rings from DNA. In 2003, chemist Fraser Stoddart and coworkers at UCLA utilised coordination chemistry to construct a set of rings in one step from 18 components. Borromean ring structures have been used to describe noble metal clusters shielded by a surface layer of thiolate ligands. A library of Borromean networks has been synthesized by design by Giuseppe Resnati and coworkers via halogen bond driven self-assembly. In order to access the molecular Borromean ring consisting of three unequal cycles a step-by-step synthesis was proposed by Jay S. Siegel and coworkers.

In physics, a quantum-mechanical analog of Borromean rings is called a halo state or an Efimov state, and consists of three bound particles that are not pairwise bound. The existence of such states was predicted by physicist Vitaly Efimov in 1970, and confirmed by multiple experiments beginning in 2006. This phenomenon is closely related to a Borromean nucleus, a stable atomic nucleus consisting of three groups of particles that would be unstable in pairs. Another analog of the Borromean rings in quantum information theory involves the entanglement of three qubits in the Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger state.

Notes

- Pronounced /bɒroʊˈmiːən/

References

- Mackey & Mackay 1922 The Pronunciation of 10,000 Proper Names

- ^ Gunn, Charles; Sullivan, John M. (2008), "The Borromean Rings: A video about the New IMU logo", in Sarhangi, Reza; Séquin, Carlo H. (eds.), Bridges Leeuwarden: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture, London: Tarquin Publications, pp. 63–70, ISBN 978-0-9665201-9-4; see the video itself at "The Borromean Rings: A new logo for the IMU Archived 2021-03-08 at the Wayback Machine" , International Mathematical Union

- ^ Cromwell, Peter; Beltrami, Elisabetta; Rampichini, Marta (March 1998), "The Borromean rings", The mathematical tourist, The Mathematical Intelligencer, 20 (1): 53–62, doi:10.1007/bf03024401, S2CID 189888135

- ^ Aigner, Martin; Ziegler, Günter M. (2018), "Chapter 15: The Borromean Rings Don't Exist", Proofs from THE BOOK (6th ed.), Springer, pp. 99–106, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-57265-8_15, ISBN 978-3-662-57265-8

- Chamberland, Marc; Herman, Eugene A. (2015), "Rock-paper-scissors meets Borromean rings", The Mathematical Intelligencer, 37 (2): 20–25, doi:10.1007/s00283-014-9499-4, MR 3356112, S2CID 558993

- ^ "Borromean rings", The Knot Atlas.

- Rolfsen, Dale (1990), Knots and Links, Mathematics Lecture Series, vol. 7 (2nd ed.), Publish or Perish, Inc., Houston, TX, p. 425, ISBN 0-914098-16-0, MR 1277811

- Conway, J. H. (1970), "An enumeration of knots and links, and some of their algebraic properties", Computational Problems in Abstract Algebra (Proc. Conf., Oxford, 1967), Oxford: Pergamon, pp. 329–358, MR 0258014; see description of notation, pp. 332–333, and second line of table, p. 348.

- Crum Brown, Alexander (December 1885), "On a case of interlacing surfaces", Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 13: 382–386

- Schoeck, Richard J. (Spring 1968), "Mathematics and the languages of literary criticism", The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 26 (3): 367–376, doi:10.2307/429121, JSTOR 429121

- Bruns, Carson J.; Stoddart, J. Fraser (2011), "The mechanical bond: A work of art", in Fabbrizzi, L. (ed.), Beauty in Chemistry, Topics in Current Chemistry, vol. 323, Springer, pp. 19–72, doi:10.1007/128_2011_296, PMID 22183145

- Lakshminarayan, Arul (May 2007), "Borromean triangles and prime knots in an ancient temple", Resonance, 12 (5): 41–47, doi:10.1007/s12045-007-0049-7, S2CID 120259064

- ^ Jablan, Slavik V. (1999), "Are Borromean links so rare?", Proceedings of the 2nd International Katachi U Symmetry Symposium, Part 1 (Tsukuba, 1999), Forma, 14 (4): 269–277, MR 1770213

- ^ Aravind, P. K. (1997), "Borromean entanglement of the GHZ state" (PDF), in Cohen, R. S.; Horne, M.; Stachel, J. (eds.), Potentiality, Entanglement and Passion-at-a-Distance, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Springer, pp. 53–59, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2732-7_4, MR 1739812

- Didron, Adolphe Napoléon (1843), Iconographie Chrétienne (in French), Paris: Imprimerie Royale, pp. 568–569

- Saiber, Arielle; Mbirika, aBa (2013), "The Three Giri of Paradiso 33" (PDF), Dante Studies (131): 237–272, JSTOR 43490498

- Ragland-Sullivan, Ellie; Milovanovic, Dragan (2004), "Introduction: Topologically Speaking", Lacan: Topologically Speaking, Other Press, ISBN 978-1-892746-76-4

- ^ Glick, Ned (September 1999), "The 3-ring symbol of Ballantine Beer", The mathematical tourist, The Mathematical Intelligencer, 21 (4): 15–16, doi:10.1007/bf03025332, S2CID 123311380

- ^ Gardner, Martin (September 1961), "Surfaces with edges linked in the same way as the three rings of a well-known design", Mathematical Games, Scientific American, reprinted as Gardner, Martin (1991), "Knots and Borromean Rings", The Unexpected Hanging and Other Mathematical Diversions, University of Chicago Press, pp. 24–33; see also Gardner, Martin (September 1978), "The Toroids of Dr. Klonefake", Asimov's Science Fiction, vol. 2, no. 5, p. 29

- Baird, Joseph L. (1970), "Unferth the þyle", Medium Ævum, 39 (1): 1–12, doi:10.2307/43631234, JSTOR 43631234,

the stone bears also representations of three horns interlaced

- "Mandala", Principia Discordia (4th ed.), March 1970, p. 43

- Bai, Sheng; Wang, Weibiao (2020), "New criteria and constructions of Brunnian links", Journal of Knot Theory and Its Ramifications, 29 (13): 2043008, 27, arXiv:2006.10290, doi:10.1142/S0218216520430087, MR 4213076, S2CID 219792382

- Nanyes, Ollie (October 1993), "An elementary proof that the Borromean rings are non-splittable", American Mathematical Monthly, 100 (8): 786–789, doi:10.2307/2324788, JSTOR 2324788

- Thistlethwaite, Morwen B. (1991), "On the algebraic part of an alternating link", Pacific Journal of Mathematics, 151 (2): 317–333, doi:10.2140/pjm.1991.151.317, MR 1132393

- Freedman, Michael H.; Skora, Richard (1987), "Strange actions of groups on spheres", Journal of Differential Geometry, 25: 75–98, doi:10.4310/jdg/1214440725; see in particular Lemma 3.2, p. 89

- Lindström, Bernt; Zetterström, Hans-Olov (1991), "Borromean circles are impossible", American Mathematical Monthly, 98 (4): 340–341, doi:10.2307/2323803, JSTOR 2323803. Note however that Gunn & Sullivan (2008) write that this reference "seems to incorrectly deal only with the case that the three-dimensional configuration has a projection homeomorphic to" the conventional three-circle drawing of the link.

- Tverberg, Helge (2010), "On Borromean rings" (PDF), The Mathematical Scientist, 35 (1): 57–60, MR 2668444, archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-03-16, retrieved 2021-03-16

- ^ Howards, Hugh Nelson (2013), "Forming the Borromean rings out of arbitrary polygonal unknots", Journal of Knot Theory and Its Ramifications, 22 (14): 1350083, 15, arXiv:1406.3370, doi:10.1142/S0218216513500831, MR 3190121, S2CID 119674622

- ^ Burgiel, H.; Franzblau, D. S.; Gutschera, K. R. (1996), "The mystery of the linked triangles", Mathematics Magazine, 69 (2): 94–102, doi:10.1080/0025570x.1996.11996399, JSTOR 2690662, MR 1394792

- ^ Cantarella, Jason; Fu, Joseph H. G.; Kusner, Rob; Sullivan, John M.; Wrinkle, Nancy C. (2006), "Criticality for the Gehring link problem" (PDF), Geometry & Topology, 10 (4): 2055–2116, arXiv:math/0402212, doi:10.2140/gt.2006.10.2055, MR 2284052

- Cantarella, Jason; Kusner, Robert B.; Sullivan, John M. (2002), "On the minimum ropelength of knots and links" (PDF), Inventiones Mathematicae, 150 (2): 257–286, arXiv:math/0103224, Bibcode:2002InMat.150..257C, doi:10.1007/s00222-002-0234-y, MR 1933586, S2CID 730891

- Uberti, R.; Janse van Rensburg, E. J.; Orlandini, E.; Tesi, M. C.; Whittington, S. G. (1998), "Minimal links in the cubic lattice", in Whittington, Stuart G.; Sumners, Witt De; Lodge, Timothy (eds.), Topology and Geometry in Polymer Science, IMA Volumes in Mathematics and its Applications, vol. 103, New York: Springer, pp. 89–100, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1712-1_9, MR 1655039; see Table 2, p. 97

- Riley, Robert (1979), "An elliptical path from parabolic representations to hyperbolic structures", in Fenn, Roger (ed.), Topology of Low-Dimensional Manifolds: Proceedings of the Second Sussex Conference, 1977, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 722, Springer, pp. 99–133, doi:10.1007/BFb0063194, ISBN 978-3-540-09506-4, MR 0547459

- ^ Ratcliffe, John G. (2006), "The Borromean rings complement", Foundations of Hyperbolic Manifolds, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 149 (2nd ed.), Springer, pp. 459–461, ISBN 978-0-387-33197-3, MR 2249478

- Abbott, Steve (July 1997), "Review of Not Knot and Supplement to Not Knot", The Mathematical Gazette, 81 (491): 340–342, doi:10.2307/3619248, JSTOR 3619248, S2CID 64589738

- ^ William Thurston (March 2002), "7. Computation of volume", The Geometry and Topology of Three-Manifolds, p. 165, archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-27, retrieved 2012-01-17

- Hilden, Hugh M.; Lozano, María Teresa; Montesinos, José María (1983), "The Whitehead link, the Borromean rings and the knot 946 are universal", Seminario Matemático de Barcelona, 34 (1): 19–28, MR 0747855

- Vogel, Denis (2005), Masseyprodukte in der Galoiskohomologie von Zahlkörpern [Massey products in the Galois cohomology of number fields], Mathematisches Institut, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen: Seminars Winter Term 2004/2005, Göttingen: Universitätsdrucke Göttingen, pp. 93–98, doi:10.11588/heidok.00004418, MR 2206880

- Morishita, Masanori (2010), "Analogies between knots and primes, 3-manifolds and number rings", Sugaku Expositions, 23 (1): 1–30, arXiv:0904.3399, MR 2605747

- ^ Chichak, Kelly S.; Cantrill, Stuart J.; Pease, Anthony R.; Chiu, Sheng-Hsien; Cave, Gareth W. V.; Atwood, Jerry L.; Stoddart, J. Fraser (May 28, 2004), "Molecular Borromean rings" (PDF), Science, 304 (5675): 1308–1312, Bibcode:2004Sci...304.1308C, doi:10.1126/science.1096914, PMID 15166376, S2CID 45191675

- Ashley, Clifford Warren (1993) , The Ashley Book of Knots, Doubleday, p. 354, ISBN 978-0-385-04025-9

- Freeman, Jim (2015), "Gathering clues from Margot's extraordinary objects", Tewkesbury Historical Society Bulletin, 24

- "African Borromean Rings", Mathematics and Knots, Centre for the Popularisation of Maths, University of Wales, 2002, retrieved 2021-02-12

- Mao, C.; Sun, W.; Seeman, N. C. (1997), "Assembly of Borromean rings from DNA", Nature, 386 (6621): 137–138, Bibcode:1997Natur.386..137M, doi:10.1038/386137b0, PMID 9062186, S2CID 4321733

- Natarajan, Ganapati; Mathew, Ammu; Negishi, Yuichi; Whetten, Robert L.; Pradeep, Thalappil (2015-12-02), "A unified framework for understanding the structure and modifications of atomically precise monolayer protected gold clusters", The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 119 (49): 27768–27785, doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b08193, ISSN 1932-7447

- Kumar, Vijith; Pilati, Tullio; Terraneo, Giancarlo; Meyer, Franck; Metrangolo, Pierangelo; Resnati, Giuseppe (2017), "Halogen bonded Borromean networks by design: topology invariance and metric tuning in a library of multi-component systems", Chemical Science, 8 (3): 1801–1810, doi:10.1039/C6SC04478F, PMC 5477818, PMID 28694953

- Veliks, Janis; Seifert, Helen M.; Frantz, Derik K.; Klosterman, Jeremy K.; Tseng, Jui-Chang; Linden, Anthony; Siegel, Jay S. (2016), "Towards the molecular Borromean link with three unequal rings: double-threaded ruthenium(ii) ring-in-ring complexes", Organic Chemistry Frontiers, 3 (6): 667–672, doi:10.1039/c6qo00025h

- Kraemer, T.; Mark, M.; Waldburger, P.; Danzl, J. G.; Chin, C.; Engeser, B.; Lange, A. D.; Pilch, K.; Jaakkola, A.; Nägerl, H.-C.; Grimm, R. (2006), "Evidence for Efimov quantum states in an ultracold gas of caesium atoms", Nature, 440 (7082): 315–318, arXiv:cond-mat/0512394, Bibcode:2006Natur.440..315K, doi:10.1038/nature04626, PMID 16541068, S2CID 4379828

- Moskowitz, Clara (December 16, 2009), "Strange physical theory proved after nearly 40 years", Live Science

- Tanaka, K. (2010), "Observation of a Large Reaction Cross Section in the Drip-Line Nucleus C", Physical Review Letters, 104 (6): 062701, Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104f2701T, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.062701, PMID 20366816, S2CID 7951719

External links

- Lamb, Evelyn (September 30, 2016), "A few of my favorite spaces: Borromean rings", Roots of Unity, Scientific American

- Borromean Olympic Rings (Brady Haran, 2012), Borromean ribbons (Tadashi Tokieda, 2016), and Neon Knots and Borromean Beer Rings (Clifford Stoll, 2018), Numberphile

- Borromean Rings, International Mathematical Union

| Knot theory (knots and links) | |

|---|---|

| Hyperbolic |

|

| Satellite | |

| Torus | |

| Invariants | |

| Notation and operations | |

| Other | |

colorings, obtained from its standard diagram by choosing a color independently for each component and discarding the

colorings, obtained from its standard diagram by choosing a color independently for each component and discarding the  colorings that only use one color. For standard diagram of the Borromean rings, on the other hand, the same pairs of arcs meet at two undercrossings, forcing the arcs that cross over them to have the same color as each other, from which it follows that the only colorings that meet the crossing conditions violate the condition of using more than one color. Because the trivial link has many valid colorings and the Borromean rings have none, they cannot be equivalent.

colorings that only use one color. For standard diagram of the Borromean rings, on the other hand, the same pairs of arcs meet at two undercrossings, forcing the arcs that cross over them to have the same color as each other, from which it follows that the only colorings that meet the crossing conditions violate the condition of using more than one color. Because the trivial link has many valid colorings and the Borromean rings have none, they cannot be equivalent.

, while the best proven lower bound on the length is

, while the best proven lower bound on the length is  .

.

. This is the length of a representation using three

. This is the length of a representation using three  integer rectangles, inscribed in

integer rectangles, inscribed in  where

where  is the

is the  is

is