| Revision as of 05:04, 3 December 2013 view sourceViriditas (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers169,597 edits These political statements are not sourced reliably nor from a NPOV. See Talk:Medical_cannabis#Recent_additions_to_lead← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:07, 3 December 2013 view source Viriditas (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers169,597 edits Please don't cherry pick abstracts.Next edit → | ||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| '''Medical cannabis''' (or '''medical marijuana''') refers to the use of ] and its constituent ], such as ], as medical therapy to treat disease or alleviate symptoms. The ] has a long history of medicinal use, with evidence dating back thousands of years.<ref name="Amar2006">{{Cite journal |author = Mohamed Ben Amar |title = Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential |journal = Journal of Ethnopharmacology |volume = 105 |issue = 1–2 |pages = 1–25 |year = 2006 |doi = 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001 |accessdate = 8 April 2010 |pmid = 16540272}}</ref> | '''Medical cannabis''' (or '''medical marijuana''') refers to the use of ] and its constituent ], such as ], as medical therapy to treat disease or alleviate symptoms. The ] has a long history of medicinal use, with evidence dating back thousands of years.<ref name="Amar2006">{{Cite journal |author = Mohamed Ben Amar |title = Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential |journal = Journal of Ethnopharmacology |volume = 105 |issue = 1–2 |pages = 1–25 |year = 2006 |doi = 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001 |accessdate = 8 April 2010 |pmid = 16540272}}</ref> Cannabis has been used ] in ] and people with ], and to treat pain and muscle spasticity.<ref name=Borgelt2013>{{cite journal |author=Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS |title=The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis |journal=Pharmacotherapy |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=195–209 |year=2013 |month=February |pmid=23386598 |doi=10.1002/phar.1187 }}</ref> Medical cannabis is administered by a variety of routes, including ] or smoking dried buds, eating extracts, and taking capsules. Synthetic cannabinoids are available as prescription drugs in some countries. Examples include ], available in the United States and Canada, and ], available in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the US. Recreational use of cannabis is illegal in most parts of the world, but the medical use of cannabis is legal in a number of countries, including Canada, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Israel, Italy, Finland, and Portugal. In the US, federal law outlaws all cannabis use, while ]. | ||

| Cannabis has been used ] in ] and people with ], and to treat pain and muscle spasticity.<ref name=Borgelt2013>{{cite journal |author=Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS |title=The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis |journal=Pharmacotherapy |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=195–209 |year=2013 |month=February |pmid=23386598 |doi=10.1002/phar.1187 }}</ref> According to a 2013 review, "Safety concerns regarding cannabis include the increased risk of developing schizophrenia with adolescent use, impairments in memory and cognition, accidental pediatric ingestions, and lack of safety packaging for medical cannabis formulations."<ref name=Borgelt2013/> | |||

| Medical cannabis is administered by a variety of routes, including ] or smoking dried buds, eating extracts, and taking capsules. Synthetic cannabinoids are available as prescription drugs in some countries. Examples include ], available in the United States and Canada, and ], available in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the US. Recreational use of cannabis is illegal in most parts of the world, but the medical use of cannabis is legal in a number of countries, including Canada, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Israel, Italy, Finland, and Portugal. In the US, federal law outlaws all cannabis use, while ]. | |||

| == Medical uses == | == Medical uses == | ||

Revision as of 05:07, 3 December 2013

This article is about the medical uses of cannabis. For general drug information, see Cannabis (drug). For other uses, see Cannabis (disambiguation).| This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. Please review the contents of the article and add the appropriate references if you can. Unsourced or poorly sourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Medical cannabis" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2013) |  |

| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (November 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Medical cannabis (or medical marijuana) refers to the use of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids, such as THC, as medical therapy to treat disease or alleviate symptoms. The Cannabis plant has a long history of medicinal use, with evidence dating back thousands of years. Cannabis has been used to reduce nausea and vomiting in chemotherapy and people with AIDS, and to treat pain and muscle spasticity. Medical cannabis is administered by a variety of routes, including vaporizing or smoking dried buds, eating extracts, and taking capsules. Synthetic cannabinoids are available as prescription drugs in some countries. Examples include dronabinol, available in the United States and Canada, and nabilone, available in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the US. Recreational use of cannabis is illegal in most parts of the world, but the medical use of cannabis is legal in a number of countries, including Canada, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Israel, Italy, Finland, and Portugal. In the US, federal law outlaws all cannabis use, while 20 states and the District of Columbia have legalized its use.

Medical uses

Medical cannabis has several potential beneficial effects. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved smoked cannabis for any condition or disease due to it considering studies to be lacking.

Medical marijuana is helpful to people who experience chronic non-cancer pain, vomiting and nausea caused by chemotherapy. The drug can also help with treating symptoms of AIDS patients. As of 2011, the use of medical marijuana is legalized in 16 U.S. states but illegal by federal law.

Cannabinoids found in marijuana may have analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects, antitumor effects, and anticancer effects, including the treatment of breast and lung cancer.

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an advisory against smoked medical cannabis stating that, "marijuana has a high potential for abuse, has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and has a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision." The National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA state that "Marijuana itself is an unlikely medication candidate for several reasons: (1) it is an unpurified plant containing numerous chemicals with unknown health effects; (2) it is typically consumed by smoking further contributing to potential adverse effects; and (3) its cognitive impairing effects may limit its utility".

The Institute of Medicine, run by the United States National Academy of Sciences, conducted a comprehensive study in 1999 to assess the potential health benefits of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids. The study concluded that smoking cannabis is not recommended for the treatment of any disease condition, but did conclude that nausea, appetite loss, pain and anxiety can all be mitigated by marijuana. While the study expressed reservations about smoked cannabis due to the health risks associated with smoking, the study team concluded that until another mode of ingestion was perfected that could provide the same relief as smoked cannabis, there was no alternative. In addition, the study pointed out the inherent difficulty in marketing a non-patentable herb. Pharmaceutical companies will probably make less investments in product development if the result is not possible to patent. The Institute of Medicine stated that there is little future in smoked cannabis as a medically approved medication. The report also concluded that for certain patients, such as the terminally ill or those with debilitating symptoms, the long-term risks are not of great concern.

"Citing the dangers of cannabis and the lack of clinical research supporting its medicinal value" the American Society of Addiction Medicine in March 2011 issued a white paper recommending a halt to using marijuana as a medicine in U.S. states where it has been declared legal.

Nausea and vomiting

Medical cannabis is somewhat effective in chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and it may be a reasonable option in those who do not improve with other treatments. Comparative studies have found cannabinoids to be more effective than some conventional anti emetics such as prochlorperazine, promethazine, and metoclopramide in controlling CINV. Their use is generally limited by the high rate of side effects, such as dizziness, dysphoria, and hallucinations. Long term cannabis use; however, may in some cause nausea and vomiting, a condition known as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

A 2010 Cochrane review said that cannabinoids were "probably effective" in treating chemotherapy-induced nausea in children, but with a high side effect profile (mainly drowsiness, dizziness, altered moods, and increased appetite). Less common side effects were "occular problems, orthostatic hypotension, muscle twitching, pruritis, vagueness, hallucinations, lightheadedness and dry mouth".

HIV/AIDS

A 2013 Cochrane review found evidence lacking for both efficacy and safety of cannabis and cannabinoids in treating patients with HIV/AIDS or for anorexia associated with AIDS; studies as of 2013 suffered from effects of bias, small sample size, and lack of long-term data.

Pain

Cannabis appears to be somewhat effective in chronic pain, including that due to neuropathy and possibly that due to fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. A 2009 review felt that it was unclear if the benefits were greater than the risks while a 2011 review considered it generally safe for this use. In palliative care its use appears safer than opioids.

Multiple sclerosis

In multiple sclerosis (MS) cannabis does not appear to improve measured spasticity but may improve the persons feelings of spasticity. Use of the drug for MS is approved in Germany and Spain. A 2012 review found no problems with tolerance, abuse or addiction.

Adverse effects

See also: Long-term effects of cannabisA 2013 literature review said that exposure to marijuana had biologically-based physical, mental, behavioral and social health consequences and was "associated with diseases of the liver (particularly with co-existing hepatitis C), lungs, heart, and vasculature". There are insufficient data to draw strong conclusions about the safety of medical cannabis, although short-term use is associated with minor adverse effects such as dizziness. While a number of preclinical and in vitro studies suggest that cannabis is carcinogenic, data on cancer risk in humans are limited and inconclusive. Further research is required to assess the long term safety of its use.

Pharmacology

Cannabis contains 483 compounds. At least 80 of these are cannabinoids, which are the basis for medical and scientific use of cannabis. This presents the research problem of isolating the effect of specific compounds and taking account of the interaction of these compounds. Cannabinoids can serve as appetite stimulants, antiemetics, antispasmodics, and have some analgesic effects. Six important cannabinoids found in the cannabis plant are tetrahydrocannabinol, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, cannabidiol, cannabinol, β-caryophyllene, and cannabigerol.

Tetrahydrocannabinol

Main article: TetrahydrocannabinolTetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the primary compound responsible for the psychoactive effects of cannabis. The compound is a mild analgesic, and cellular research has shown the compound has antioxidant activity. THC is believed to interact with parts of the brain normally controlled by the endogenous cannabinoid neurotransmitter, anandamide. Anandamide is believed to play a role in pain sensation, memory, and sleep.

Cannabidiol

Main article: CannabidiolCannabidiol (CBD) is a major constituent of medical cannabis. CBD represents up to 40% of extracts of medical cannabis. Cannabidiol has been shown to relieve convulsion, inflammation, anxiety, cough, congestion and nausea, and it inhibits cancer cell growth. Recent studies say cannabidiol is as effective as atypical antipsychotics in treating schizophrenia and psychosis. Because cannabidiol relieves the aforementioned symptoms, cannabis strains with a high amount of CBD may benefit people with multiple sclerosis or frequent anxiety attacks.

Cannabinol

Main article: CannabinolCannabinol (CBN) is a therapeutic cannabinoid found only in trace amounts in Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica. It is mostly produced as a metabolite, or a breakdown product, of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). CBN acts as a weak agonist of the CB1 and CB2 receptors, with lower affinity in comparison to THC.

β-Caryophyllene

Main article: CaryophyllenePart of the mechanism by which medical cannabis has been shown to reduce tissue inflammation is via the compound β-caryophyllene. A cannabinoid receptor called CB2 plays a vital part in reducing inflammation in humans and other animals. β-Caryophyllene has been shown to be a selective activator of the CB2 receptor. β-Caryophyllene is especially concentrated in cannabis essential oil, which contains about 12–35% β-caryophyllene.

Cannabigerol

Main article: CannabigerolLike cannabidiol, cannabigerol is not psychoactive. Cannabigerol has been shown to relieve intraocular pressure, which may be of benefit in the treatment of glaucoma.

Pharmacologic THC and THC derivatives

In the U.S., the FDA has approved several cannabinoids for use as medical therapies: dronabinol (Marinol) and nabilone. These medicines are taken orally.

These medications are usually used when first line treatments for nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy fail to work. In extremely high doses and in rare cases "psychotomimetic" side effects are possible. The other commonly used antiemetic drugs are not associated with these side effects.

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Medical cannabis" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Marinol's manufacturer stated on their website: "The most frequently reported side effects in patients with AIDS during clinical studies involved the central nervous system (CNS). These CNS effects (euphoria, dizziness, or thinking abnormalities, for example) were reported by 33% of patients taking MARINOL". Four documented fatalities resulting from Marinol have been reported.

Nabiximols (USAN, trade name Sativex) is an aerosolized mist for oral administration intended for the treatment of pain. The prescription drug Sativex, an extract of cannabis administered as a sublingual spray, has been approved in Canada for the adjunctive treatment (use alongside other medicines) of both multiple sclerosis and cancer related pain. Sativex has also been approved in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and the Czech Republic, and is expected to gain approval in other European countries. William Notcutt is one of the chief researchers that has developed Sativex, and he has been working with GW and founder Geoffrey Guy since the company's inception in 1998. Notcutt states that the use of MS as the disease to study "had everything to do with politics."

| Medication | Approval | Country | Licensed indications | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nabilone | 1985 | U.S., Canada | Nausea of cancer chemotherapy that has failed to respond adequately to other antiemetics | US$4000.00 for a year's supply (in Canada) |

| Canasol | 1987 | U.S., Canada, several Caribbean nations | Introcular pressure associated with late-stage Glaucoma | |

| Marinol | 1985 | U.S., Canada (1992) |

Nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy in patients who have failed to respond adequately to conventional treatments |

US$652 for 30 doses @ 10 mg online |

| 1992 | U.S. | Anorexia associated with AIDS–related weight loss | ||

| Sativex | 1995 | Canada | Adjunctive treatment for the symptomatic relief of neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis in adults |

C$ 9,351 per year |

| 1997 | Canada | Pain due to cancer |

Strains

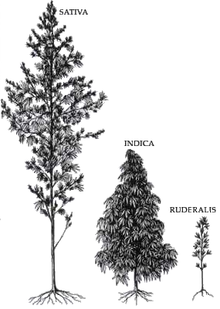

The genus Cannabis contains two species which produce useful amounts of psychoactive cannabinoids. Cannabis indica produces a higher level of cannabidiol (abbreviated CBD) relative to THC (the primary psychoactive component in medical and recreational cannabis). Cannabis sativa, on the other hand, produces a higher level of THC relative to CBD.

Medical use of sativa is associated with a cerebral high, and many patients experience stimulating effects. For this reason, sativa is often used for daytime treatment. It may cause more of a euphoric, "high" sensation, and tends to stimulate hunger, making it potentially useful to patients with eating disorders or anorexia.Sativa also exhibits a higher tendency to induce anxiety and paranoia, so patients prone to these effects may limit treatment with pure sativa, or choose hybrid strains.

Cannabis indica is associated with sedative effects and is often preferred for night time use, including for treatment of insomnia. Indica is also associated with a more "stoned" or meditative sensation than the euphoric, stimulating effects of sativa, possibly because of a higher CBD-to-THC ratio.

Many strains of cannabis are currently cultivated for medical use, including strains of both species in varying potencies, as well as hybrid strains designed to incorporate the benefits of both species. Hybrids commonly available can be heavily dominated by either Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica, or relatively balanced, such as so-called "50/50" strains.

Cannabis strains with relatively high CBD-to-THC ratios, usually indica-dominant strains, are less likely to induce anxiety. This may be due to CBD's receptor antagonistic effects at the cannabinoid receptor, compared to THC's partial agonist effect. CBD is also a 5-HT1A receptor agonist, which may also contribute to an anxiolytic effect. This likely means the high concentrations of CBD found in Cannabis indica mitigate the anxiogenic effect of THC significantly.

Methods of consumption

One of the major criticisms of cannabis as medicine is opposition to smoking as a method of consumption. However, smoking is not necessary due to alternative methods of ingestion. Medicinal cannabis patients can use vaporizers, where the essential cannabis compounds are extracted and inhaled. In addition, edible cannabis, which is produced in various baked goods, is also available, and has demonstrated longer lasting effects.

Any possible harm caused by smoking cannabis can be minimized by the use of a vaporizer or ingesting the drug in an edible form. Vaporizers are devices that heat the active constituents to a temperature below the ignition point of the cannabis, so that the resultant vapors can be inhaled. Combustion of plant material is avoided, thus preventing the formation of carbon monoxide and carcinogens, such as polyaromatic hydrocarbons and benzene. There are pocket-sized forms of vaporizer which use rechargeable batteries, are constructed from wood, and feature removable covers.

History

Ancient China and Taiwan

Cannabis, called má 麻 (meaning "hemp; cannabis; numbness") or dàmá 大麻 (with "big; great") in Chinese, was used in Taiwan for fiber starting about 10,000 years ago. The botanist Li Hui-Lin wrote that in China, "The use of Cannabis in medicine was probably a very early development. Since ancient humans used hemp seed as food, it was quite natural for them to also discover the medicinal properties of the plant." The oldest Chinese pharmacopeia, the (ca. 100 CE) Shennong Bencaojing 神農本草經 ("Shennong's Materia Medica Classic"), describes dama "cannabis".

The flowers when they burst (when the pollen is scattered) are called 麻蕡 or 麻勃 . The best time for gathering is the seventh day of the seventh month. The seeds are gathered in the ninth month. The seeds which have entered the soil are injurious to man. It grows in (in ...). The flowers, the fruit (seed) and the leaves are officinal. The leaves and the fruit are said to be poisonous, but not the flowers and the kernels of the seeds.

Emperor Shen-Nung, who was also a pharmacologist, wrote a book on treatment methods in 2737 that included the medical benefits of cannabis. He recommended the substance for many ailments, including constipation, gout, rheumatism, and absent-mindedness. Hua Tuo lived many years later, yet he is credited with being the first person known to use cannabis as an anesthetic. He reduced the plant to powder and mixed it with wine for administration. In China, the era of Han Western, the 3rd century the great surgeon Hua Tuo conducts operations under anesthesia using Indian hemp. The Chinese term for anesthesia (麻醉: má zui ) is also composed of the ideogram which means hemp, followed by means of intoxication. Elizabeth Wayland Barber says the Chinese evidence "proves a knowledge of the narcotic properties of Cannabis at least from the 1st millennium B.C." when ma was already used in a secondary meaning of "numbness; senseless." "Such a strong drug, however, suggests that the Chinese pharmacists had now obtained from far to the southwest not THC-bearing Cannabis sativa but Cannabis indica, so strong it knocks you out cold.

Cannabis is one of the 50 "fundamental" herbs in traditional Chinese medicine, and is prescribed to treat diverse indications. FP Smith writes in Chinese Materia Medica: Vegetable Kingdom:

Every part of the hemp plant is used in medicine ... The flowers are recommended in the 120 different forms of (風 feng) disease, in menstrual disorders, and in wounds. The achenia, which are considered to be poisonous, stimulate the nervous system, and if used in excess, will produce hallucinations and staggering gait. They are prescribed in nervous disorders, especially those marked by local anaesthesia. The seeds ... are considered to be tonic, demulcent, alterative, laxative, emmenagogue, diuretic, anthelmintic, and corrective. ... They are prescribed internally in fluxes, post-partum difficulties, aconite poisoning, vermillion poisoning, constipation, and obstinate vomiting. Externally they are used for eruptions, ulcers, favus, wounds, and falling of the hair. The oil is used for falling hair, sulfur poisoning, and dryness of the throat. The leaves are considered to be poisonous, and the freshly expressed juice is used as an anthelmintic, in scorpion stings, to stop the hair from falling out and to prevent it from turning gray. ... The stalk, or its bark, is considered to be diuretic ... The juice of the root is ... thought to have a beneficial action in retained placenta and post-partum hemorrhage. An infusion of hemp ... is used as a demulcent drink for quenching thirst and relieving fluxes.

Ancient Egypt

The Ebers Papyrus (ca. 1550 BCE) from Ancient Egypt describes medical cannabis. Other ancient Egyptian papyri that mention medical cannabis are the Ramesseum III Papyrus (1700 BC), the Berlin Papyrus (1300 BCE) and the Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus VI (1300 BCE). The ancient Egyptians even used hemp (cannabis) in suppositories for relieving the pain of hemorrhoids. Around 2,000 BCE, the ancient Egyptians used cannabis to treat sore eyes. The egyptologist Lise Manniche notes the reference to "plant medical cannabis" in several Egyptian texts, one of which dates back to the eighteenth century BCE.

Ancient India

Cannabis was a major component in religious practices in ancient India as well as in medicinal practices. For many centuries, most parts of life in ancient India incorporated cannabis of some form. Surviving texts from ancient India confirm that cannabis' psychoactive properties were recognized, and doctors used it for treating a variety of illnesses and ailments. These included insomnia, headaches, a whole host of gastrointestinal disorders, and pain: cannabis was frequently used to relieve the pain of childbirth. One Indian philosopher expressed his views on the nature and uses of bhang (a form of cannabis), which combined religious thought with medical practices. "A guardian lives in the bhang leaf. …To see in a dream the leaves, plant, or water of bhang is lucky. …A longing for bhang foretells happiness. It cures dysentry and sunstroke, clears phlegm, quickens digestion, sharpens appetite, makes the tongue of the lisper plain, freshens the intellect and gives alertness to the body and gaiety to the mind. Such are the useful and needful ends for which in His goodness the Almighty made bhang."

Ancient Greece

The Ancient Greeks used cannabis to dress wounds and sores on their horses. In humans, dried leaves of cannabis were used to treat nose bleeds, and cannabis seeds were used to expel tapeworms. The most frequently described use of cannabis in humans was to steep green seeds of cannabis in either water or wine, later taking the seeds out and using the warm extract to treat inflammation and pain resulting from obstruction of the ear.

In the 5th century BCE Herodotus, a Greek historian, described how the Scythians of the Middle East used cannabis in steam baths. These baths drove the people to a frenzied state.

Medieval Islamic world

In the medieval Islamic world, Arabic physicians made use of the diuretic, antiemetic, antiepileptic, anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic properties of Cannabis sativa, and used it extensively as medication from the 8th to 18th centuries.

Modern history

An Irish physician, William Brooke O'Shaughnessy, is credited with introducing the therapeutic use of cannabis to Western medicine. He was Assistant-Surgeon and Professor of Chemistry at the Medical College of Calcutta, and conducted a cannabis experiment in the 1830s, first testing his preparations on animals, then administering them to patients to help treat muscle spasms, stomach cramps or general pain.

Cannabis as a medicine became common throughout much of the Western world by the 19th century. In the 19th century was cannabis one of the secret ingredients in several so called patent medicines. There were at least 2000 cannabis medicines prior to 1937, produced by over 280 manufacturers. Cannabis was used as the primary pain reliever until the invention of aspirin. A Swedish lexicon printed in 1912 describes the cannabis drug and extract as a "deserted" method for medical treatment.

Modern medical and scientific inquiry began with doctors like O'Shaughnessy and Moreau de Tours, who used it to treat melancholia and migraines, and as a sleeping aid, analgesic and anticonvulsant. At the local level authorities introduced various laws that required the mixtures that contained cannabis, that was not sold on prescription, must be marked with warning labels under the so-called poison laws. In 1905 Samuel Hopkins Adams published an exposé entitled "The Great American Fraud" in Collier's Weekly about the patent medicines that led to the passage of the first Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. This statute did not ban the alcohol, narcotics, and stimulants in the medicines; rather, it required medicinal products to be labeled as such and curbed some of the more misleading, overstated, or fraudulent claims that previously appeared on labels.

At the turn of the 20th century the Scandanavian cannabis-based drink Maltos-cannabis was widely available in Denmark and Norway. Promoted as "an excellent lunch drink, especially for children and young people", the product had won a prize at the Exposition Internationale d'Anvers in 1894.

Later in the century, researchers investigating methods of detecting cannabis intoxication discovered that smoking the drug reduced intraocular pressure. In 1955 the antibacterial effects were described at the Palacký University of Olomouc. Since 1971 Lumír Ondřej Hanuš was growing cannabis for his scientific research on two large fields in authority of the University. The marijuana extracts were then used at the University hospital as a cure for aphthae and haze. In 1973 physician Tod H. Mikuriya reignited the debate concerning cannabis as medicine when he published "Marijuana Medical Papers". High intraocular pressure causes blindness in glaucoma patients, so he hypothesized that using the drug could prevent blindness in patients. Many Vietnam War veterans also found that the drug prevented muscle spasms caused by spinal injuries suffered in battle. Later medical use focused primarily on its role in preventing the wasting syndromes and chronic loss of appetite associated with chemotherapy and AIDS, along with a variety of rare muscular and skeletal disorders.

In 1964, Dr. Albert Lockhart and Manley West began studying the health effects of traditional cannabis use in Jamaican communities. They discovered that Rastafarians had unusually low glaucoma rates and local fishermen were washing their eyes with cannabis extract in the belief that it would improve their sight. Lockhart and West developed, and in 1987 gained permission to market, the pharmaceutical Canasol: one of the first cannabis extracts. They continued to work with cannabis, developing more pharmaceuticals and eventually receiving the Jamaican Order of Merit for their work.

Later, in the 1970s, a synthetic version of THC was produced and approved for use in the United States as the drug Marinol. It was delivered as a capsule, to be swallowed. Patients complained that the violent nausea associated with chemotherapy made swallowing capsules difficult. Further, along with ingested cannabis, capsules are harder to dose-titrate accurately than smoked cannabis because their onset of action is so much slower. Smoking has remained the route of choice for many patients because its onset of action provides almost immediate relief from symptoms and because that fast onset greatly simplifies titration. For these reasons, and because of the difficulties arising from the way cannabinoids are metabolized after being ingested, oral dosing is probably the least satisfactory route for cannabis administration. Relatedly, some studies have indicated that at least some of the beneficial effects that cannabis can provide may derive from synergy among the multiplicity of cannabinoids and other chemicals present in the dried plant material.

Voters in eight U.S. states showed their support for cannabis prescriptions or recommendations given by physicians between 1996 and 1999, including Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington, going against policies of the federal government. In May 2001, "The Chronic Cannabis Use in the Compassionate Investigational New Drug Program: An Examination of Benefits and Adverse Effects of Legal Clinical Cannabis" (Russo, Mathre, Byrne et al.) was completed. This three-day examination of major body functions of four of the five living US federal cannabis patients found "mild pulmonary changes" in two patients.

Among the more than 108,000 persons in Colorado who in 2012 had received a certificate to use marijuana for medical purposes, 94% said that severe pain was the reason for the requested certificate, followed by 3% for cancer and 1% for HIV/Aids. The typical card holder was a 41-year-old male (not the normal pattern for patients with pain problems). Twelve doctors had issued 50% of the certificates.

Society and culture

Methods of acquisition

The method of obtaining medical cannabis varies by region and by legislation. Currently some of the permitted methods are through regulated marijuana dispensaries (or marijuana clubs) or by self-propagation. In some areas it is legal for a person to grow their own marijuana for personal use.

The authors of report on a 2011 survey of medical cannabis users say that critics have suggested that some users "game the system" to obtain medical cannabis ostensibly for treatment of a condition, but then use it for nonmedical purposes – though the truth of this claim is hard to measure. The report authors suggested rather that medical cannabis users occupied a "continnum" between medical and nonmedical use.

Dispensing machines

A marijuana vending machine is a vending machine for selling or dispensing marijuana. They are currently in use in the United States. In the United States, they are normally located in secure rooms in medical marijuana dispensaries. They are operated by employees after a fingerprint scan is obtained from the patient. In Canada, marijuana vending machines are planned to be used in centres that cultivate the drug.

At least three companies are developing the vending machines. Endexx Corp. (ticker symbol: EDXC) has recently acquired two smaller companies to merge their respective technologies into a marijuana vending machine. The first acquisition, called Cann-Can LLC, was announced by Endexx on April 9, 2013. Cann-Can's founder and developer, David Levine, was brought onto the Endexx board as a specialty consultant. David Levine has extensive vending machine expertise and holds a patent for a vending machine messaging system. The second acquisition, known as Dispense Labs LLC, was finalized and announced by Endexx on October 7, 2013. Dispense Labs has developed an advanced vending machine, known as Autospense, through its partnership with the leader in industrial vending inventory solutions, Autocrib, Inc. The Autospense machines have many built-in benefits and features to improve security, inventory management, profitability, efficiency, accountability and to mitigate risk. Endexx, through its wholly owned subsidiary, Dispense Labs, has secured exclusive worldwide rights for medical marijuana dispensing technology with Autocrib. Together, with M3Hub and the recent acquisition of THCFinder.com, these vending machine acquisitions will enable Endexx to provide a complete seed-to-sale solution to assist dispensaries, and other cannabis-related businesses, to work within the confines of the law. Additionally, it is expected that the THC Finder website will enable marijuana patients to locate the nearest dispensary with an Autospense marijuana vending machine.

Medbox Inc. is the industry leader in medical marijuana dispensing machines. They sell two machines for $50,000, one foredible marijuana products like brownies, and the other for portions of marijuana itself. As of October 2013, Medbox has sold approximately 160 marijuana vending machines to US medical marijuana dispensaries.

Tranzbyte Corp. plans to commence distribution of vending machines that use radio-frequency identification tags.

US Classification and patent

A number of medical organizations have endorsed reclassification of marijuana to allow for further study. These include, but are not limited to:

- The American Medical Association

- The American College of Physicians – America's second largest physicians group

- Leukemia & Lymphoma Society – America's second largest cancer charity

- American Academy of Family Physicians opposes the use of marijuana except under medical supervision

Other medical organizations recommend a halt to using marijuana as a medicine in U.S.

The National Institutes of Health holds a patent for medical cannabis. The patent, "Cannabinoids as antioxidants and neuroprotectants", issued October 2003 reads:

Cannabinoids have been found to have antioxidantproperties, unrelated to NMDA receptor antagonism. This new found property makes cannabinoids useful in the treatment and prophylaxis of wide variety of oxidation associated diseases, such as ischemic, age-related,inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. The cannabinoids are found to have particular application as neuroprotectants, for example in limiting neurological damage following ischemic insults, such as stroke and trauma, or in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and HIV dementia... .

National and international regulations

Main article: Legal and medical status of cannabis

Medical use of cannabis or preparation containing THC as the active substance is legalized in Canada, Belgium, Austria, Netherlands, UK, Spain, Israel, Finland and some states in the U.S., although it is still illegal under U.S. federal law.

Cannabis is in Schedule IV of the United Nations' Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, making it subject to special restrictions. Article 2 provides for the following, in reference to Schedule IV drugs:

A Party shall, if in its opinion the prevailing conditions in its country render it the most appropriate means of protecting the public health and welfare, prohibit the production, manufacture, export and import of, trade in, possession or use of any such drug except for amounts which may be necessary for medical and scientific research only, including clinical trials therewith to be conducted under or subject to the direct supervision and control of the Party.

The convention thus allows countries to outlaw cannabis for all non-research purposes but lets nations choose to allow medical and scientific purposes if they believe total prohibition is not the most appropriate means of protecting health and welfare. The convention requires that states that permit the production or use of medical cannabis must operate a licensing system for all cultivators, manufacturers and distributors and ensure that the total cannabis market of the state shall not exceed that required "for medical and scientific purposes."

African countries

Cannabis has been used in African countries since at least the 15th century. Its use was introduced by Arab traders, somehow connected to India. "In Africa, the plant was used for snake bite, to facilitate childbirth, malaria, fever, blood poisoning, anthrax, asthma, and dysentery." (Zuardi, 2006, 4) Though African governments have tried to limit and stop its use, it still seems to be deeply ingrained, mostly through religious rituals.

Austria

In Austria, both Δ-THC and pharmaceutical preparations containing Δ-THC are listed in annex V of the Narcotics Decree (Suchtgiftverordnung). Compendial formulations are manufactured upon prescription according to the German Neues Rezeptur-Formularium.

On 9 July 2008, the Austrian Parliament approved cannabis cultivation for scientific and medical uses. Cannabis cultivation is controlled by the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety (Österreichische Agentur für Gesundheit und Ernährungssicherheit, AGES).

Canada

In Canada, the regulation on access to cannabis for medical purposes, established by Health Canada in February 2000, defines two categories of patients eligible for access to medical cannabis. BC College of Physicians and Surgeons’ recommendation, as well as the CMPA position, is that physicians may prescribe cannabis if they feel comfortable with it. The MMAR forms are a confidential document between Health Canada, the physician and the patient. The information is not shared with the College or with the RCMP. No doctor has ever gone to court or faced prosecution for filling out a form or for prescribing medical cannabis. Category 1 covers any symptoms treated within the context of providing compassionate end-of-life care or the symptoms associated with different medical conditions. Category 2 is for applicants who have debilitating symptom(s) of medical condition(s), other than those described in Category 1. The application of eligible patients must be supported by a medical practitioner.

The cannabis distributed by Health Canada is provided under the brand CannaMed by the company Prairie Plant Systems Inc. In 2006, 420 kg of CannaMed cannabis was sold, representing an increase of 80% over the previous year. However, patients complain of the single strain selection as well as low potency, providing a pre-ground product put through a wood chipper (which deteriorates rapidly) as well as gamma irradation and foul taste and smell.

It is also legal for patients approved by Health Canada to grow their own cannabis for personal consumption, and it's possible to obtain a production license as a person designated by a patient. Designated producers were permitted to grow a cannabis supply for only a single patient. However, that regulation and related restrictions on supply were found unconstitutional by the Federal Court of Canada in January 2008. The court found that these regulations did not allow a sufficient legal supply of medical cannabis, and thus forced many patients to purchase their medicine from unauthorized, black market sources. This was the eighth time in the previous ten years that the courts ruled against Health Canada's regulations restricting the supply of the medicine. On 14 Dec 2012 the Canadian government announced plans to overhaul its rules regarding medical cannabis.

In Canada, there are four forms of medical cannabis. The first one is a cannabis extract called Sativex that contains THC and cannabidiol in a spray form. The second is a synthetic or manmade THC called dronabinol marketed as Marinol. The third also a synthetic version of THC called nabilone that is called Cesamet on the markets. The fourth product is the herbal form of cannabis often referred to as marijuana.

Czech Republic

Medical use of cannabis has been legal and regulated in the Czech Republic since April 1, 2013.

France

As of June 8, 2013, cannabis derivatives can be used in France for the manufacture of medicinal products. The products can only be obtained with a prescription and will only be prescribed when all other medications have failed to effectively relieve suffering. The amended legislation decriminalizes "the production, transport, export, possession, offering, acquisition or use of speciality pharmaceutials that contains one of these (cannabis-derivative) substances”, while all cannabis products must be approved by the National Medical Safety Agency (Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament – ANSM). A Pharmacists' Union spokesperson explained to the media that the change will make it more straightforward to conduct research into cannabinoids.

Germany

In February 2008, seven German patients could legally be treated with medicinal cannabis, distributed by prescription in pharmacies. To regulate therapeutic use, Germany modeled on Dutch neighbor who distributes this way since in 2003 (120 kg in 2008).

In Germany, dronabinol was rescheduled in 1994 from annex I to annex II of the Narcotics Law (Betäubungsmittelgesetz) in order to ease research; in 1998 dronabinol was rescheduled from annex II to annex III and since then has been available by prescription, whereas Δ-THC is still listed in annex I. Manufacturing instructions for dronabinol containing compendial formulations are described in the Neues Rezeptur-Formularium.

Israel

Marijuana for medical use has been permitted in Israel since the early 1990s for cancer patients and those with pain-related illnesses such as Parkinson's, multiple sclerosis, Crohn's Disease, other chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder. Patients can smoke the drug, ingest it in liquid form, or apply it to the skin as a balm. The numbers of patients authorized to use marijuana in Israel in 2012 is about 10,000.

There are eight government-sanctioned cannabis growing operations in Israel, which distribute it for medical purposes to patients who have a prescription from a doctor, via either a company's store, or in a medical center.

THC, the psychoactive chemical component in marijuana that causes a high, was first isolated by Israeli scientists Raphael Mechoulam of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem's Center for Research on Pain and Yechiel Gaoni of the Weizmann Institute in 1964.

The Tikkun Olam company has developed a variety of marijuana that is reported to provide the medical benefits of cannabis, but without THC. The cannabis instead contains high quantities of CBD, a substance that is believed to be an anti-inflammatory ingredient, which helps alleviate pain.

Netherlands

Since 2003, the country's pharmacies distribute medicinal cannabis (pharmaceutical form of the natural plant) by prescription, in addition to other drugs containing cannabinoids (dronabinol, Sativex).

Spain

In Spain, the sale and public consumption remains illegal, and private cultivation and use are permitted to associations.

Several cannabis consumption clubs and user associations have been established throughout Spain. These clubs, the first of which was created in 1991, are non-profit associations who grow cannabis and sell it at cost to its members. The legal status of these clubs is uncertain: in 1997, four members of the first club, the Barcelona Ramón Santos Association of Cannabis Studies, were sentenced to 4 months in prison and a 3000 euro fine, while at about the same time, the court of Bilbao ruled that another club was not in violation of the law. The Andalusian regional government also commissioned a study by criminal law professors on the "Therapeutic use of cannabis and the creation of establishments of acquisition and consumption. The study concluded that such clubs are legal as long as they distribute only to a restricted list of legal adults, provide only the amount of drugs necessary for immediate consumption, and not earn a profit. The Andalusian government never formally accepted these guidelines and the legal situation of the clubs remains insecure. In 2006 and 2007, members of these clubs were acquitted in trial for possession and sale of cannabis and the police were ordered to return seized crops.

United Kingdom

In England and Wales, the use of cannabis medicinally is accepted as a mitigating factor under Sentencing Council guidelines, if it is being cultivated or found in possession of someone. However, in the United Kingdom, possession of small quantities of cannabis does not usually warrant an arrest or court appearance (street cautions or fines are often given out instead). Under UK law, certain cannabinoids are permitted medically, but these are strictly controlled with many provisos under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (in the 1985 amendments).

The British Medical Association's official stance is "users of cannabis for medical purposes should be aware of the risks, should enrol for clinical trials, and should talk to their doctors about new alternative treatments; but we do not advise them to stop."

United States

Main article: Medical cannabis in the United States

In the United States, cannabis per se has been criminalized at the Federal level by implementation of the Controlled Substances Act, which classifies cannabis as a Schedule I drug – the strictest classification, on par with heroin, LSD and ecstasy. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Gonzales v. Raich that the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution allows the government to ban any use of cannabis, including medical use. The United States Food and Drug Administration states "marijuana has a high potential for abuse, has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and has a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision".

Two American (for-profit) companies, Cannabis Science Inc., and Medical Marijuana, Inc., are working towards getting FDA approval for cannabis based medicines (including smoked cannabis). Cannabis Science Inc. wants to have medical cannabis approved by the FDA so anyone, regardless of state, will have access to the medicine. Also, there is one non-profit organization, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) working towards getting Cannabis approved by the FDA for PTSD.

Since the medical marijuana movement began, twenty states and the District of Columbia, starting with California in 1996, have legalized medical cannabis or effectively decriminalized it: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington; Maryland allows for reduced or no penalties if cannabis use has a medical basis. Despite legalization of marijuana in Washington and Colorado, an employee may still be fired if they test positive on a drug test, despite having a doctor's recommendation. California, Colorado, New Mexico, Maine, Rhode Island, Montana, and Michigan are currently the only states to utilize dispensaries to sell medical cannabis; Connecticut and Massachusetts are also planning to do so. During 2008, California's medical cannabis industry took in about $2 billion and generated $100 million in state sales taxes with an estimated 2,100 dispensaries, co-operatives, wellness clinics and taxi delivery services in the sector colloquially known as "cannabusiness".

Though it does not have an established medical registry program, the state of Virginia, does allow for possession under the directive as medicine.

Some individual states such as Oregon choose to issue medical marijuana cards to residents with a doctors recommendation after paying a fee.

In October 2009, the U.S. Deputy Attorney General issued a U.S. Department of Justice memorandum to "All United States Attorneys" providing clarification and guidance to federal prosecutors in states that have enacted medical marijuana laws. The document is intended solely as "a guide to the exercise of investigative and prosecutorial discretion and as guidance on resource allocation and federal priorities." It includes seven criteria to help determine whether a patient's use, or their caregiver's provision, of medical cannabis "represents part of a recommended treatment regiment consistent with applicable state law". The Department advised that it "likely was not an efficient use of federal resources to focus enforcement efforts on seriously ill individuals, or on their individual caregivers. ... Large-scale, for-profit commercial enterprises, on the other , ... continued to be appropriate targets for federal enforcement and prosecution."

The sale and distribution of cannabis remains illegal under federal law, however, as the Food and Drug Administration's position – that marijuana has no accepted value in the treatment of any disease in the United States – remains unchanged.

In November 2011, in accordance with 35 U.S.C. 209(c)(1) and 37 CFR part 404.7(a)(1)(i), the NIH announced that it is contemplating the grant of an exclusive patent license to practice the invention embodied therein to KannaLife Sciences Inc.. The prospective exclusive license territory may be worldwide, and the field of use may be limited to: The development and sale of cannabinoid(s) and cannabidiol(s) based therapeutics as antioxidants and neuroprotectants for use and delivery in humans, for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy, as claimed in the Licensed Patent Rights.

Research

Anecdotal evidence and pre-clinical research has suggested that cannabis or cannabinoids may be beneficial for treating Huntington's disease or Parkinson's disease, but follow-up studies of people with these conditions has not produced good evidence of therapeutic potential. A 2001 paper argued that cannabis had properties that made it potentially applicable to the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and on that basis research on this topic should be permitted, despite the legal difficulties of the time.

A 2005 paper argued that bipolar disorder was not well-controlled by existing medications and that there were "good pharmacological reasons" for thinking cannabis had therapeutic potential, making it a good candidate for further study in this respect.

Cannabinoids have been proposed for the treatment of primary anorexia nervosa, but have no measurable beneficial effect. The authors of a 2003 paper argued that cannabinoids might have useful future clinical applications in treating digestive diseases.

Dementia

Cannabinoids have been proposed as having the potential for lessening the effects of Alzheimer's disease. A 2012 review of the effect of cannabinoids on brain ageing found that "clinical evidence regarding their efficacy as therapeutic tools is either inconclusive or still missing". A 2009 Cochrane review said that the "one small randomized controlled trial assessed the efficacy of cannabinoids in the treatment of dementia ... ... poorly presented results and did not provide sufficient data to draw any useful conclusions".

Diabetes

There is a lack of meaningful evidence of the effects of medical cannabis use on people with diabetes. A 2010 review concluded that "the potential risks and benefits for diabetic patients remain unquantified at the present time".

Epilepsy

There is not enough evidence to draw conclusions about the safety or efficacy of cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy. There have been few studies of the anticonvulsive properties of CBD and epileptic disorders. The major reasons for the lack of clinical research have been the introduction of new synthetic and more stable pharmaceutical anticonvulsants, the recognition of important adverse effects and the legal restriction to the use of cannabis-derived medicines.

Glaucoma

The American Glaucoma Society noted that while cannabis can help lower intraocular pressure, it recommended against its use because of "its side effects and short duration of action, coupled with a lack of evidence that it use alters the course of glaucoma." As of 2008 relatively little research had been done concerning effects of cannabinoids on the eye.

Tourette syndrome

Controlled research on treating Tourette syndrome with a synthetic version of THC called (Marinol), showed the patients taking the pill had a beneficial response without serious adverse effects; other studies have shown that cannabis "has no effects on tics and increases the individuals inner tension". A 2009 Cochrane Review found that the few relevant studies of cannibinoids in treating tics had attrition bias, and that there was "not enough evidence to support the use of cannabinoids in treating tics and obsessive compulsive behaviour in people with Tourette's syndrome".

See also

References

- ^ Mohamed Ben Amar (2006). "Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 105 (1–2): 1–25. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001. PMID 16540272.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Amar2006" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS (2013). "The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis". Pharmacotherapy. 33 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1002/phar.1187. PMID 23386598.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Joseph W. Jacob; Joseph W. Jacob B. a. M. P. a. (2009). Medical Uses of Marijuana. Trafford Publishing. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4269-1540-6.

- Aggarwal, SK; Carter, GT; Sullivan, MD; Zumbrunnen, C; Morrill, R; Mayer, JD (2009). "Medicinal use of cannabis in the United States: Historical perspectives, current trends, and future directions". Journal of opioid management. 5 (3): 153–68. PMID 19662925.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - "Workshop on the Medical Utility of Marijuana". National Institutes of Health. 1997. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- "FDA: Inter-Agency Advisory Regarding Claims That Smoked Marijuana Is a Medicine". Fda.gov. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- Clark, Peter A.; Capuzzi, Kevin; Fick, Cameron (2011). "Medical marijuana: Medical necessity versus political agenda". Medical Science Monitor. 17 (12): RA249–61. doi:10.12659/MSM.882116. PMC 3628147. PMID 22129912.

- "Cannabis and Cannabinoids (PDQ®)". National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health®. 2 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "Inter-agency advisory regarding claims that smoked marijuana is a medicine". fda.gov. 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2012Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Nida: Marijuana, An update from the National Institute on Drug Abuse". Nida.nih.gov. 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Medical Marijuana Passes House Civil Justice Committee Without Dissent" (Press release). Minnesotans for Compassionate Care. 11 March 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- Joy, Janet E.; Watson, Stanley J.; Benson, John A., eds. (1999). Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-07155-0. OCLC 246585475.

- ^ "American Society of Addiction Medicine Rejects Use of 'Medical Marijuana,' Citing Dangers and Failure To Meet Standards of Patient Care, March 23, 2011". Maryland. PR Newswire. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Medical Marijuana, American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2010". Asam.org. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- Borgelt, LM (2013 Feb). "The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis". Pharmacotherapy. 33 (2): 195–209. PMID 23386598.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Grotenhermen, Franjo; Müller-Vahl, Kirsten (2012). "The Therapeutic Potential of Cannabis and Cannabinoids". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 109 (29–30): 495–501. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2012.0495. PMC 3442177. PMID 23008748.

- Bowles DW, O'Bryant CL, Camidge DR, Jimeno A (2012). "The intersection between cannabis and cancer in the United States". Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 83 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.09.008. PMID 22019199.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang T, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Ware MA (2008). "Adverse effects of medical cannabinoids: a systematic review". CMAJ. 178 (13): 1669–78. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071178. PMC 2413308. PMID 18559804.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jordan K, Sippel C, Schmoll HJ (2007). "Guidelines for antiemetic treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: past, present, and future recommendations". Oncologist. 12 (9): 1143–50. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1143. PMID 17914084.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nicolson, SE (2012 May-Jun). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case series and review of previous reports". Psychosomatics. 53 (3): 212–9. PMID 22480624.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Phillips RS, Gopaul S, Gibson F; et al. (2010). "Antiemetic medication for prevention and treatment of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting in childhood". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (9): CD007786. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007786.pub2. PMID 20824866.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lutge EE, Gray A, Siegfried N (2013). "The medical use of cannabis for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4: CD005175. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005175.pub3. PMID 23633327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martín-Sánchez, E (2009 Nov). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of cannabis treatment for chronic pain". Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 10 (8): 1353–68. PMID 19732371.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lynch, ME (2011 Nov). "Cannabinoids for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain; a systematic review of randomized trials". British journal of clinical pharmacology. 72 (5): 735–44. PMID 21426373.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Carter, GT (2011 Aug). "Cannabis in palliative medicine: improving care and reducing opioid-related morbidity". The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 28 (5): 297–303. PMID 21444324.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Thaera, GM (2009 Nov). "Do cannabinoids reduce multiple sclerosis-related spasticity?". The neurologist. 15 (6): 369–71. PMID 19901724.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Grotenhermen, F; Müller-Vahl, K (2012). "The therapeutic potential of cannabis and cannabinoids". Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 109 (29–30): 495–501. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2012.0495. PMC 3442177. PMID 23008748.

- Clark, PA; Capuzzi, K; Fick, C (2011). "Medical marijuana: Medical necessity versus political agenda". Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 17 (12): RA249–61. PMC 3628147. PMID 22129912.

- Oreja-Guevara, C (2012). "Treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: New perspectives regarding the use of cannabinoids". Revista de neurologia. 55 (7): 421–30. PMID 23011861.

- Gordon AJ, Conley JW, Gordon JM (2013). "Medical consequences of marijuana use: a review of current literature". Curr Psychiatry Rep. 15 (12): 419. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0419-7. PMID 24234874.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Cannabis (marihuana, marijuana) and the cannabinoids". Health Canada. February 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- "Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Human/Clinical Studies". National Cancer Institute. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- Wang, T.; Collet, J.-P.; Shapiro, S.; Ware, M. A. (2008). "Adverse effects of medical cannabinoids: A systematic review". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 178 (13): 1669–78. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071178. PMC 2413308. PMID 18559804.

- Barceloux, Donald G (2012). "Chapter 60: Marijuana (Cannabis sativa L.) and synthetic cannabinoids". Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. pp. 886–931. ISBN 978-0-471-72760-6.

- Downer EJ, Campbell VA (2010). "Phytocannabinoids, CNS cells and development: A dead issue?". Drug and Alcohol Review. 29 (1): 91–98. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00102.x. PMID 20078688.

- Burns TL, Ineck JR (2006). "Cannabinoid analgesia as a potential new therapeutic option in the treatment of chronic pain". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 40 (2): 251–260. doi:10.1345/aph.1G217. PMID 16449552.

- Kohn, David (5 November 2004). "Researchers buzzing about marijuana-derived medicines". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Hampson AJ, Grimaldi M, Axelrod J, Wink D. (July 1998). "Cannabidiol and (−)Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants". PNAS. 95 (14): 8268–73. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.8268H. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.8268. PMC 20965. PMID 9653176. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Etinger A, Mechoulam R (1992). "Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor". Science. 258 (5090): 1946–1949. Bibcode:1992Sci...258.1946D. doi:10.1126/science.1470919. PMID 1470919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mechoulam R, Fride E (1995). "The unpaved road to the endogenous brain cannabinoid ligands, the anandamides". In Pertwee RG (ed.). Cannabinoid receptors. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 233–258. ISBN 0-12-551460-3.

- Grlic, Ljubiša (1976). "A comparative study on some chemical and biological characteristics of various samples of cannabis resin". Bulletin on Narcotics. 14: 37–46.

- ^ Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Hanus LO (2007). "Cannabidiol--recent advances". Chem. Biodivers. 4 (8): 1678–92. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790147. PMID 17712814.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Moreira, F.A.; Guimarães, F.S. (2006). "Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent, as an antipsychotic drug". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 39 (4): 421–9. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2006000400001. PMID 16612464.

- Campos, AC; Moreira, FA; Gomes, FV; Del Bel, EA; Guimaraes, FS (2012). "Multiple mechanisms involved in the large-spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders". Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 367 (1607): 3364–78. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0389. PMC 3481531. PMID 23108553.

- Lakhan SE, Rowland M (2009). "Whole plant cannabis extracts in the treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". BMC Neurology. 9: 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-9-59. PMC 2793241. PMID 19961570.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Karniol IG, Shirakawa I, Takahashi RN, Knobel E, Musty RE (1975). "Effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabinol in man". Pharmacology. 13 (6): 502–12. doi:10.1159/000136944. PMID 1221432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McCallum ND, Yagen B, Levy S, Mechoulam R (1975). "Cannabinol: a rapidly formed metabolite of delta-1- and delta-6-tetrahydrocannabinol". Experientia. 31 (5): 520–1. doi:10.1007/BF01932433. PMID 1140243.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mahadevan A, Siegel C, Martin BR, Abood ME, Beletskaya I, Razdan RK (2000). "Novel cannabinol probes for CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 43 (20): 3778–85. doi:10.1021/jm0001572. PMID 11020293.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Petitet F, Jeantaud B, Reibaud M, Imperato A, Dubroeucq MC (1998). "Complex pharmacology of natural cannabinoids: evidence for partial agonist activity of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and antagonist activity of cannabidiol on rat brain cannabinoid receptors". Life Sciences. 63 (1): PL1–6. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00238-0. PMID 9667767.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gertsch J; Leonti M; Raduner S; Racz, I.; Chen, J.-Z.; Xie, X.-Q.; Altmann, K.-H.; Karsak, M.; Zimmer, A. (2008). "Beta-caryophyllene is a dietary cannabinoid". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (26): 9099–104. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9099G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803601105. PMC 2449371. PMID 18574142.

- Colasanti, BK (1990). "A comparison of the ocular and central effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabigerol". Journal of ocular pharmacology. 6 (4): 259–69. doi:10.1089/jop.1990.6.259. PMID 1965836.

- Colasanti, BK; Craig, CR; Allara, RD (1984). "Intraocular pressure, ocular toxicity and neurotoxicity after administration of cannabinol or cannabigerol". Experimental eye research. 39 (3): 251–9. doi:10.1016/0014-4835(84)90013-7. PMID 6499952.

- "Marijuana vs. Marinol – A side by side comparison". ProCon.org. Retrieved 7 January 2013Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Marinol. fda.gov (September 2004).

- "Deaths from Marijuana v. 17 FDA-Approved Drugs". ProCon.org. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Stepper, H. P., Department of Health and Human Services (24 August 2005) Letter to Mr. Yablan. medicalmarijuana.procon.org

- United States Adopted Names Coincil: Statement on a nonproprietary name

- Koch, Wendy (23 June 2005). "Spray alternative to pot on the market in Canada". USA Today. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- "Sativex – Investigational Cannabis-Based Treatment for Pain and Multiple Sclerosis Drug Development Technology". SPG Media. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- Cooper, Rachel."GW Pharmaceuticals launches world's first prescription cannabis drug in Britain" The Telegraph. 21 June 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "Sativex Approved in New Zealand" GW Pharmaceuticals. 3 Nov.2010. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "Sativex Approved in the Czech Republic" GW Pharmaceuticals. 15 April 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Greenberg, Gary (2005). "Respectable Reefer". Mother Jones. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- Skrabek RQ, Galimova L, Ethans K, Perry D (2008). "Nabilone for the treatment of pain in fibromyalgia". The Journal of Pain. 9 (2): 164–73. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.002. PMID 17974490.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "ALL PRICES FOR: Marinol – Brand Version: 10 mg". PharmacyChecker.com. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- "FDA approves new indication for Dronabinol" (Press release). Food and Drug Administration. 23 December 1992. Archived from the original on 6 May 1997. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- "Sativex: CEDAC Final Recommendation on Reconsideration and Reasons for Recommendation" (PDF). Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 27 September 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- "What are the differences between Cannabis indica and Cannabis sativa, and how do they vary in their potential medical utility?". ProCon.org.

- Johns, A. (2001). "Psychiatric effects of cannabis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 178 (2): 116. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.2.116. PMID 11157424.

- ^ J.E. Joy, S. J. Watson, Jr., and J.A. Benson, Jr, (1999). Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing The Science Base. Washington D.C: National Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 0-585-05800-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Baltazar, Amanda. "What is Medical Marijuana". About.com. Retrieved 09/30/01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Group, United Patients. "Ways to Consume Medical Marijuana". Retrieved 10/01/2013.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "MAPS/CaNORML vaporizer and waterpipe studies". Maps.org. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Jeff Winkler (13 September 2013). "Stealth stoner". Aeon Magazine. Aeon Magazine Ltd. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Abel, Ernest L. (1980). "Cannabis in the Ancient World". Marihuana: the first twelve thousand years. New York City: Plenum Publishers. ISBN 978-0-306-40496-2.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Li, Hui-Lin (1974). "An Archaeological and Historical Account of Cannabis in China", Economic Botany 28.4:437–448, p. 444.

- Bretschneider, Emil (1895). Botanicon Sinicum: Notes on Chinese Botany from Native and Western Sources. Part III, Botanical Investigations in the Materia Medica of the Ancient Chinese. Kelly & Walsh. p. 378.

- ^ Bloomquist, Edward (1971). Marijuana: The Second Trip. California: Glencoe Press.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 CE). Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 332. ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0. OCLC 71779118.

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. (1992). Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean. Princeton University Press. p. 38.

- Wong, Ming (1976). La Médecine chinoise par les plantes. Paris: Tchou. OCLC 2646789.

- Smith, Frederick Porter (1911). Chinese Materia Medica: Vegetable Kingdom. Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press. pp. 90–91.

- "The Ebers Papyrus The Oldest (confirmed) Written Prescriptions For Medical Marihuana era 1,550 BC". onlinepot.org. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- "History of Cannabis". reefermadnessmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 25 May 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- Pain, Stephanie (15 December 2007). "The Pharaoh's pharmacists". New Scientist. Reed Business Information Ltd.

- (Webley, Kayla. "Brief History: Medical Marijuana." Time 21 June 2010.)

- Lise Manniche, An Ancient Egyptian Herbal, University of Texas Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0-292-70415-2

- Touw, Mia (1981). "The Religious and Medicinal Uses ofCannabisin China, India and Tibet". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 13 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1080/02791072.1981.10471447. PMID 7024492.

- ^ Butrica, James L. (2002). "The Medical Use of Cannabis Among the Greeks and Romans". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2 (2): 51. doi:10.1300/J175v02n02_04.

- Lozano, Indalecio (2001). "The Therapeutic Use of Cannabis sativa (L.) in Arabic Medicine". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 1: 63. doi:10.1300/J175v01n01_05.

- ^ Tom Decorte; Gary W. Potter; Martin Bouchard (2011). World Wide Weed: Global Trends in Cannabis Cultivation and Its Control. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4094-1780-4.

- Alison Mack; Janet Joy (7 December 2000). Marijuana As Medicine?: The Science Beyond the Controversy. National Academies Press. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-309-06531-3.

- The Antique Cannabis Book. antiquecannabisbook.com (16 March 2012). Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- "History of Cannabis". BBC News. 2 November 2001. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- "Hasjisj in Nordisk Famijebok 1912" (in Swedish). Runeberg.org. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- "The Newsweekly for Pharmacy". Chemist + Druggist. 28. London, New York City, Melbourne: Benn Brothers: 68, 330. 1886.

- Adams, Samuel Hopkins (1905). The Great American Fraud (4th ed., 1907). Chicago: American Medical Association. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Golden Guide". zauberpilz.com.

- Template:Cz icon "Nad léčivými jointy s Lumírem Hanušem". blisty.cz. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- Zimmerman, Bill (1998). Is Marijuana the Right Medicine for You?: A Factual Guide to Medical Uses of Marijuana. Keats Publishing. ISBN 0-87983-906-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dr Farid F. Youssef. "Cannibis Unmasked: What it is and why it does what it does". UWIToday: June 2010. http://sta.uwi.edu/uwitoday/archive/june_2010/article9.asp

- Baker D, Pryce G, Giovannoni G, Thompson AJ (2003). "The therapeutic potential of cannabis". Lancet Neurol. 2 (5): 291–8. PMID 12849183.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McPartland, John M.; Russo, Ethan B. (2001). "Cannabis and cannabis extracts: greater than the sum of their parts?". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 1 (3–4): 103. doi:10.1300/J175v01n03_08.

- Mack,Alison ; Joy, Janet (2001). Marijuana As Medicine. National Academy Press. ISBN 0-309-06531-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Russo, Ethan; Mathre, Mary Lynn; Byrne, Al; Velin, Robert; Bach, Paul J.; Sanchez-Ramos, Juan; Kirlin, Kristin A. (2002). "Chronic Cannabis Use in the Compassionate Investigational New Drug Program". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics. 2: 3. doi:10.1300/J175v02n01_02.

- Medical Marijuana Regulatory System, Part II. Department of Public Health and Environment, Department of Revenue Performance Audit, June 2013

- ^ Reinarman, C; Nunberg, H; Lanthier, F; Heddleston, T (2011). "Who Are Medical Marijuana Patients? Population Characteristics from Nine California Assessment Clinics". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 43 (2): 128–135. doi:10.1080/02791072.2011.587700. PMID 21858958.

- Laskow, Sarah (10 June 2013). "Marijuana vending machines are the future of recreational drug use". Grist. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Marijuana vending machines". News.msn.com. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ "The pot vending machine's first foreign market? Canada, of course, 'a seed for the rest of the world' | National Post". News.nationalpost.com. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Marijuana Vending Machines Popping Up At California Pot Clubs " CBS San Francisco". Sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Vrankulj, Adam (13 November 2012). "Medbox partners with Canadian medical marijuana R&D lab". BiometricUpdate.com. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Marijuana vending machines coming to a store near you? | Mail Online". Dailymail.co.uk. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Epstein, Mike (16 November 2012). "Marijuana Vending Machine Maker's Stock Skyrockets and Everybody Freaks Out". Geekosystem. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ "Marijuana Vending Machines, Stoner Fantasy, May Become Industry Norm". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Marijuana vending machines: helfpul or just hype? | Marijuana and Cannabis News". Toke of the Town. 29 March 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Marijuana Vending Machine Investing". Wealthdaily.com. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Endexx Acquires Cann-Can LLC". PR Newswire (US).

- "MB Media Brokers To License Vending Messaging System". Vending Market Watch.

- "Endexx closes Acquisition of Dispense Labs LLC". PR Newswire (US).

- "www.Autospense.com".

- "Endexx Secures Exclusive World Wide Rights for Medical Marijuana Dispensing Technology". PR Newswire (US).

- "www.m3hub.com".

- "www.thcfinder.com/".

- "Endexx's M3Hub(TM) Platform Supports State Legalized Marijuana Laws". PR Newswire (US).

- "Endexx's M3Hub Platform Is the Robust "Seed to Sale" Tracking Solution". PR Newswire (US).

- "THCFinder.com Joins the M3Hub(TM)". PR Newswire (US).

- AMA meeting: Delegates support review of cannabis's schedule I status; A change could make it easier for researchers to test potential medical uses and develop a drug delivery form safer than smoking. By Kevin B. O'Reilly, American Medical News. 30 November 2009