| Revision as of 23:36, 29 March 2007 view source75.134.17.18 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:42, 7 January 2025 view source AlsoWukai (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users31,852 edits ceTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{short description|U.S. state}} | ||

| {{redirect|Badger State|other uses|Wisconsin (disambiguation)|and|Badger State (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{US state | | |||

| {{pp|vandalism|small=yes|expiry=indef}} | |||

| Name = Wisconsin | | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=December 2024}}{{Use American English|date=July 2022}} | |||

| Fullname = State of Wisconsin | | |||

| {{Infobox U.S. state | |||

| Flag = Flag of Wisconsin.svg | | |||

| | name = Wisconsin | |||

| | image_flag = Flag of Wisconsin.svg | |||

| Seal = Wisconsinstateseal.jpg | | |||

| | flag_link = Flag of Wisconsin | |||

| Map = Map_of_USA_WI.svg | | |||

| | image_seal = Seal of Wisconsin.svg | |||

| Nickname = Badger State | | |||

| | seal_link = Seal of Wisconsin | |||

| Motto = Forward | | |||

| | image_map = Wisconsin in United States.svg | |||

| Capital = ] | | |||

| | nicknames = Badger State, America's Dairyland<ref>{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=PRqCCp3svlwC&pg=PA5 |page= 5 |title= Wisconsin: It's my state! |first1= Margaret |last1= Dornfeld |first2= Richard |last2= Hantula |publisher= Marshall Cavendish |year= 2010 |isbn= 978-1-60870-062-2 |access-date= June 10, 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150907174046/https://books.google.com/books?id=PRqCCp3svlwC&pg=PA5 |archive-date= September 7, 2015 |url-status= live }}</ref><ref name="Urdang">{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=E9bt2QhyFIsC |title= Names and Nicknames of Places and Things |publisher= Penguin Group USA |first= Laurence |last= Urdang |year= 1988 |isbn= 9780452009073 |page= 8 |quote= "America's Dairyland" A nickname of Wisconsin |access-date= May 25, 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150906150036/https://books.google.com/books?id=E9bt2QhyFIsC |archive-date= September 6, 2015 |url-status= live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=fVoYAAAAIAAJ |title= Nicknames and sobriquets of U.S. cities, States, and counties |first1= Joseph Nathan |last1= Kane |first2= Gerard L. |last2= Alexander |publisher= Scarecrow Press |year= 1979 |page= 412 |isbn= 9780810812550 |quote= Wisconsin—America's Dairyland, The Badger State{{nbsp}}...The Copper State|access-date= May 25, 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150906161709/https://books.google.com/books?id=fVoYAAAAIAAJ |archive-date= September 6, 2015 |url-status= live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=iCEl1sqlZLQC&pg=PA10 |title= Wisconsin Encyclopedia, American Guide |first= Jennifer L. |last= Herman |publisher= North American Book Dist LLC |year= 2008 |page= 10 |isbn= 9781878592613 |quote= Nicknames Wisconsin is generally known as The Badger State, or America's Dairyland, although in the past it has been nicknamed The Copper State. |access-date= May 25, 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150906165221/https://books.google.com/books?id=iCEl1sqlZLQC&pg=PA10 |archive-date= September 6, 2015 |url-status= live }}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170222160612/http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lrb/blue_book/2005_2006/975_symbols.pdf |date=February 22, 2017 }} in ''Wisconsin Blue Book 2005–2006'', p. 966.</ref> | |||

| OfficialLang = None | | |||

| | motto = Forward | |||

| LargestCity = ] | | |||

| | anthem = "]"{{break}}{{center|]}} | |||

| Governor = ] (D)| | |||

| | Former = Wisconsin Territory | |||

| Senators = ] (D)<br />] (D) | | |||

| | seat = ] | |||

| AreaRank = 23<sup>rd</sup> | | |||

| | population_demonym = ], ] (colloquial) | |||

| TotalArea = 169,790 | | |||

| | OfficialLang = None | |||

| TotalAreaUS = 65,498| | |||

| | Languages = | |||

| LandArea = 140,787 | | |||

| * English 91.32% | |||

| LandAreaUS = 54,310| | |||

| * Spanish 4.64% | |||

| WaterArea = 28,006 | | |||

| * Other 8.68%<ref>{{cite web|url=https://worldpopulationreview.com/states/wisconsin-population|title=Wisconsin Population 2022 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)|website=wisconsinpopulationreview.com|access-date=November 18, 2022|archive-date=November 18, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221118072226/https://worldpopulationreview.com/states/wisconsin-population|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| WaterAreaUS = 11,188| | |||

| | LargestCity = ] | |||

| PCWater = 17 | | |||

| | LargestCounty = ] | |||

| PopRank = 18<sup>th</sup> | | |||

| | LargestMetro = ] | |||

| |population_as_of = ] | |||

| | Governor = ] (]) | |||

| |population_note = 5,363,675 | | |||

| | Lieutenant Governor = ] (D) | |||

| |population_total = 5,556,506 | | |||

| | Legislature = ] | |||

| DensityRank = 24<sup>th</sup> | | |||

| | Upperhouse = ] | |||

| 2000Pop = 5,363,675 | | |||

| | Lowerhouse = ] | |||

| 2000Density = 38.13 | | |||

| | Judiciary = ] | |||

| 2000DensityUS = 98.8 <!--census.gov --> | | |||

| | Senators = {{plainlist| | |||

| MedianHouseholdIncome = $47,220 | | |||

| * ] (]) | |||

| IncomeRank = 15<sup>th</sup> | | |||

| * ] (])}} | |||

| AdmittanceOrder = 30<sup>th</sup> | | |||

| | Representative = {{plainlist| | |||

| AdmittanceDate = ], ] | | |||

| * 6 Republicans | |||

| TimeZone = ]: ]-6/] | | |||

| * 2 Democrats}} | |||

| Latitude = 42°30'N to 47°3'N | | |||

| | area_rank = 23rd<ref>{{Cite web |title=State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates |url=https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/2010/geo/state-area.html |date=2010 |website=US Census Bureau |access-date=October 22, 2023 |archive-date=April 7, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200407014954/https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/2010/geo/state-area.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Longitude = 86°49'W to 92°54'W | | |||

| | area_total_sq_mi = 65,498.37 | |||

| Width = 420 | | |||

| | area_total_km2 = | |||

| WidthUS =260 | | |||

| | area_land_sq_mi = 54,153.1 | |||

| Length = 500 | | |||

| | area_land_km2 = | |||

| LengthUS = 310 | | |||

| | area_water_percent = 17 | |||

| HighestPoint = ]<ref name="usgs2005">{{cite web|year=] ]|url=http://erg.usgs.gov/isb/pubs/booklets/elvadist/elvadist.html#Highest|title=Elevations and Distances in the United States|publisher=U.S Geological Survey|accessdate=2006-11-9}}</ref> | | |||

| | Latitude = 42° 30' N to 47° 05′ N | |||

| HighestElev = 595 | | |||

| | Longitude = 86° 46′ W to 92° 54′ W | |||

| HighestElevUS = 1,951 | | |||

| | population_rank = 20th | |||

| MeanElev = 320 | | |||

| | population_as_of = 2024 | |||

| MeanElevUS = 1,050 | | |||

| | 2010Pop = {{IncreaseNeutral}} 5,960,975<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/WI/PST045224|accessdate=January 5, 2025|title= United States Census Quick Facts Wisconsin}}</ref> | |||

| LowestPoint = ]<ref name="usgs"/> | | |||

| | 2010DensityUS = 108.8 | |||

| LowestElev = 77 | | |||

| | 2010Density = | |||

| LowestElevUS = 579 | | |||

| | MedianHouseholdIncome = $64,168<ref name="2020census">{{cite web |title=Explore Census Data |url=https://data.census.gov/cedsci/profile?g=0400000US55 |website=data.census.gov |access-date=October 5, 2021 |archive-date=October 5, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211005154331/https://data.census.gov/cedsci/profile?g=0400000US55 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ISOCode = US-WI | | |||

| | IncomeRank = ] | |||

| PostalAbbreviation = WI | | |||

| | AdmittanceOrder = 30th | |||

| TradAbbreviation = Wis.| | |||

| | AdmittanceDate = May 29, 1848 | |||

| Website = www.wisconsin.gov | |||

| | timezone1 = ] | |||

| | utc_offset1 = – 06:00 | |||

| | timezone1_DST = ] | |||

| | utc_offset1_DST = – 05:00 | |||

| | width_km = 427 | |||

| | width_mi = 260 | |||

| | length_km = 507 | |||

| | length_mi = 311 | |||

| | elevation_max_point = ]<ref name=USGS>{{cite web|url=http://egsc.usgs.gov/isb/pubs/booklets/elvadist/elvadist.html |title=Elevations and Distances in the United States |publisher=] |year=2001 |access-date=October 24, 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111015012701/http://egsc.usgs.gov/isb/pubs/booklets/elvadist/elvadist.html |archive-date=October 15, 2011 }}</ref><ref name=NAVD88>Elevation adjusted to ].</ref> | |||

| | elevation_max_m = 595 | |||

| | elevation_max_ft = 1,951 | |||

| | elevation_m = 320 | |||

| | elevation_ft = 1,050 | |||

| | elevation_min_point = ]<ref name=USGS /><ref name=NAVD88 /> | |||

| | elevation_min_m = 176 | |||

| | elevation_min_ft = 579 | |||

| | iso_code = US-WI | |||

| | postal_code = WI | |||

| | TradAbbreviation = Wis., Wisc. | |||

| | website = https://www.wisconsin.gov | |||

| | Capital = | |||

| | Representatives = | |||

| | module = {{Infobox region symbols | |||

| | embedded = yes | |||

| | country = United States | |||

| | state = Wisconsin | |||

| | bird = {{unbulleted list|]|''Turdus migratorius''}} | |||

| | fish = {{unbulleted list|]|''Esox masquinongy''}} | |||

| | flower = {{unbulleted list|]|''Viola sororia''}} | |||

| | insect = {{unbulleted list|]|''Apis mellifera''}} | |||

| | tree = {{unbulleted list|]|''Acer saccharum''}} | |||

| | beverage = Milk | |||

| | dance = ] | |||

| | food = {{unbulleted list|Corn|''Zea mays''}} | |||

| | fossil = {{unbulleted list|]|''Calymene celebra''}} | |||

| | mineral = ] | |||

| | rock = ] | |||

| | tartan = ] | |||

| }}<!--end of module--> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Wisconsin''' ({{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Wisconsin.ogg|w|ᵻ|ˈ|s|k|ɒ|n|s|ᵻ|n}} {{respell|wiss|KON|sin}})<ref>{{Cite Merriam-Webster|Wisconsin|accessdate=March 8, 2024}}</ref> is a ] in the ] region of the ] of the ]. It borders ] to the west, ] to the southwest, ] to the south, ] to the east, ] to the northeast, and ] to the north. With a population of about 6 million<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/WI/PST045224|accessdate=January 5, 2025|title= United States Census Quick Facts Wisconsin}}</ref> and an area of about 65,500 square miles, Wisconsin is the ] and the ]. It has ]. Its ] is ]; its ] and second-most populous city is ]. Other urban areas include ], ], ], ], and the ].<ref>{{cite news |title=Census: Madison, suburbs top list of fastest-growing cities in Wisconsin |url=https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/govt-and-politics/census-madison-suburbs-top-list-of-fastest-growing-cities-in-wisconsin/article_c079b92b-1f18-5ac4-8538-0c74e004e018.html |access-date=July 24, 2020 |work=] |language=en |archive-date=July 25, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200725033154/https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/govt-and-politics/census-madison-suburbs-top-list-of-fastest-growing-cities-in-wisconsin/article_c079b92b-1f18-5ac4-8538-0c74e004e018.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{portal|Wisconsin}} | |||

| '''Wisconsin''' (]: {{IPAudio|Wisconsin.ogg|}}) is a ] in the ], and is located in the ] region. The ] of the state is ], and its current ] is ] and the owner is Zachary Blumenfeld. | |||

| ] is diverse, shaped by ] glaciers except in the ]. The ] and ] along with a part of the ] occupy the state's western part, with lowlands stretching to Lake Michigan. Wisconsin is third to ] and Michigan in the length of its ] coastline. Its northern portion is home to the ]. At the time of European contact, the area was inhabited by ] and ] nations, and today it is home to ] federally recognized ].<ref>{{cite web |title=American Indians in Wisconsin – Overview |url=https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/minority-health/population/amind-pop.htm |website=] |date=August 12, 2014 |access-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817205053/https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/minority-health/population/amind-pop.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> Originally part of the ], it was ] in 1848. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, many European settlers entered the state, mostly from ] and ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Germans in Wisconsin |url=https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS2041 |website=] |date=August 3, 2012 |access-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817205035/https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS2041 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Gordon |first1=Scott |title=How Scandinavians Transformed The Midwest, And The Midwest Transformed Them Too |url=https://www.wiscontext.org/how-scandinavians-transformed-midwest-and-midwest-transformed-them-too |website=] |access-date=August 17, 2021 |date=November 4, 2016 |archive-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817205046/https://www.wiscontext.org/how-scandinavians-transformed-midwest-and-midwest-transformed-them-too |url-status=live }}</ref> Wisconsin remains a center of ] and ] culture,<ref>{{cite web |title=German and Scandinavian Immigrants in the American Midwest |url=http://digitalexhibits.libraries.wsu.edu/exhibits/show/2016sphist417/immigration/germans-and-scandinavians |website=] |publisher=Washington State University |access-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-date=August 12, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210812190315/http://digitalexhibits.libraries.wsu.edu/exhibits/show/2016sphist417/immigration/germans-and-scandinavians |url-status=live }}</ref> particularly in respect to its ], with foods such as ] and ]. | |||

| Wisconsin, bordered by the states of ], ], ] and ], as well as Lakes ] and ], has been part of United States territory since the end of the ]; the ] (which included parts of other current states) was formed on ], ]. Wisconsin ratified its ] ], ] and was admitted to the Union on ], ] as the thirtieth state. The state's southern boundary line was originally supposed to reach the southern-most tip of Lake Michigan, but for some reason politics intervened during the debates of the ] to make it as it appears in the present day. Wisconsin would have possessed the City of ] had the state line been pushed further south as originally contemplated. | |||

| Wisconsin is one of the nation's leading ] and is known as "America's Dairyland"; it is particularly famous for ].<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.wisconsin.uk/ | title=wisconsin.uk | access-date=October 25, 2019 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191025193722/https://wisconsin.uk/ | archive-date=October 25, 2019 | url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Our Fifty States}}</ref> The state is also famous for ], particularly and historically ], most notably as the headquarters of the ]. Wisconsin has some of the nation's most permissive ] and is known for its ].<ref>{{Cite magazine|last=Matthews|first=Christopher|title=The 3 Best and 3 Worst States in America for Drinking|magazine=]|url=https://business.time.com/2013/12/05/the-3-best-and-3-worst-states-in-america-for-drinking/|url-status=live|access-date=October 29, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190901203759/http://business.time.com/2013/12/05/the-3-best-and-3-worst-states-in-america-for-drinking/|archive-date=September 1, 2019|issn=0040-781X}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=White |first1=Laurel |title=High Tolerance: How State's Drinking Culture Developed |url=https://urbanmilwaukee.com/2019/05/19/high-tolerance-how-states-drinking-culture-developed/ |website=urbanmilwaukee.com |publisher=] |access-date=December 8, 2021 |date=May 19, 2019 |archive-date=December 8, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211208184253/https://urbanmilwaukee.com/2019/05/19/high-tolerance-how-states-drinking-culture-developed/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Its economy is dominated by manufacturing, healthcare, information technology, and agriculture—specifically dairy, ], and ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/ginseng-continues-rebound-in-central-wisconsin/article_5dd63657-78ac-5cfe-ac88-419af3e9bf09.html|title=Ginseng continues rebound in central Wisconsin|last=Adams|first=Barry |work=Wisconsin State Journal |access-date=August 11, 2018|language=en|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180811195428/https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/ginseng-continues-rebound-in-central-wisconsin/article_5dd63657-78ac-5cfe-ac88-419af3e9bf09.html|archive-date=August 11, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> Tourism is also a major contributor to its economy.<ref>{{cite news |title=Evers announces $10M to promote tourism industry in Wisconsin |url=https://www.cbs58.com/news/evers-announces-10m-to-promote-tourism-industry-in-wisconsin |access-date=August 17, 2021 |agency=] |date=August 3, 2021 |archive-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817205037/https://www.cbs58.com/news/evers-announces-10m-to-promote-tourism-industry-in-wisconsin |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] in 2020 was $348 billion.<ref>{{cite web |title=Wisconsin |url=https://www.forbes.com/places/wi/?sh=9db899823a16 |work=] |access-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-date=August 17, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817205041/https://www.forbes.com/places/wi/?sh=9db899823a16 |url-status=live }}</ref> Wisconsin is home to one ] ], comprising ] designed by Wisconsin-born architect ]: his studio at ] near ] and his ] in Madison.<ref name="whs">{{cite web |url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1496 |title=The 20th-century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright |publisher=UNESCO World Heritage Centre |access-date=July 7, 2019 |archive-date=July 9, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190709141412/http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1496 |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] was founded in Wisconsin in 1854; in modern elections, it is considered a ]. | |||

| Wisconsin's economy was originally based on farming (especially dairy), mining, and lumbering. In the 20th century, tourism became important, and many people living on former farms commuted to jobs elsewhere. Large-scale industrialization began in the late 19th century in the southeast of the state, with the city of ] as its major center. In recent decades, ], especially medicine and education, have become dominant. Wisconsin's landscape, largely shaped by the ] of the last ], makes the state popular for both tourism and many forms of outdoor recreation. | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| Since its founding, Wisconsin has been ethnically heterogeneous, with ]s being among the first to arrive from New York and New England. They dominated the state's heavy industry, finance, politics and education. Large numbers of European immigrants followed them, including Germans, mostly between 1850 and 1900, Scandinavians and smaller groups of Belgians, Dutch, Swiss, Finns, Irish and others; in the 20th century, large numbers of Poles and ]s came, settling mainly in Milwaukee. | |||

| The word ''Wisconsin'' originates from the name given to the ] by one of the ]-speaking Native American groups living in the region at the time of ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/topics/wisconsin-name/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051028075712/http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/topics/wisconsin-name/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=October 28, 2005 |title=Wisconsin's Name: Where it Came from and What it Means |access-date=July 24, 2008 |publisher=Wisconsin Historical Society}}</ref> The French explorer ] was the first European to reach the Wisconsin River, arriving in 1673 and calling the river {{lang|fr|Meskousing}} (likely ᒣᔅᑯᐤᓯᣙ ''meskowsin'') in his journal.<ref>{{Cite book | last = Marquette | first = Jacques | author-link = Jacques Marquette | year = 1673 | contribution = The Mississippi Voyage of Jolliet and Marquette, 1673 | contribution-url = http://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-051/ | editor-last = Kellogg | editor-first = Louise P. | title = Early Narratives of the Northwest, 1634–1699 | place = New York | publisher = Charles Scribner's Sons | page = 235 | oclc = 31431651 | access-date = July 25, 2008 | archive-date = January 25, 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210125212847/https://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-051/ | url-status = live }}</ref> Subsequent French writers changed the spelling from {{lang|fr|Meskousing}} to {{lang|fr|Ouisconsin}}, and over time this became the name for both the Wisconsin River and the surrounding lands. English speakers ] the spelling from {{lang|fr|Ouisconsin}} to ''Wisconsin'' when they began to arrive in large numbers during the early 19th century. The legislature of ] made the current spelling official in 1845.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Smith | first = Alice E. | title = Stephen H. Long and the Naming of Wisconsin | journal = Wisconsin Magazine of History | volume = 26 | issue = 1 | pages = 67–71 | date = September 1942 | url = http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/u?/wmh,14413 | access-date = July 24, 2008 | archive-url = https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20170525200450/http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wmh/id/14413 | archive-date = May 25, 2017 | url-status = dead }}</ref> | |||

| The ] word for Wisconsin and its original meaning have both grown obscure. While interpretations vary, most implicate the river and the red sandstone that lines its banks. One leading theory holds that the name originated from the ] word {{lang|mia|Meskonsing}}, meaning {{gloss|it lies red}}, a reference to the setting of the Wisconsin River as it flows through the reddish sandstone of the ].<ref>McCafferty, Michael. 2003. '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170911183554/http://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=2002552&journal_code=ONO |date=September 11, 2017 }}''. Onoma 38: 39–56</ref> Other theories include claims that the name originated from one of a variety of ] words meaning {{gloss|red stone place}}, {{gloss|where the waters gather}}, or {{gloss|great rock}}.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Vogel | first = Virgil J. | title = Wisconsin's Name: A Linguistic Puzzle | journal = Wisconsin Magazine of History | volume = 48 | issue = 3 | pages = 181–186 | year = 1965 | url = http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/u?/wmh,23263 | access-date = July 24, 2008 | archive-url = https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20170525200457/http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wmh/id/23263 | archive-date = May 25, 2017 | url-status = dead }}</ref> | |||

| Today, 42.6% of the population is of German ancestry, making Wisconsin one of the most ] states in the ]. Numerous ] ]s are held throughout Wisconsin to celebrate its heritage. Such festivals are world renowned, and include Italian Days, Bastille Days, Summerfest, Africal World Festival, Indian Summer, and many others. | |||

| During the period of the ], Wisconsin was a ] and pro-Union stronghold. Ethno-religious issues in the late 19th century caused a brief split in the Republican coalition. Through the first half of the 20th century, Wisconin's politics were dominated by ] and his sons, originally of the ], but later of their own ]. Since 1945, the state has maintained a close balance between Republicans and ]. Republican Senator ] was a major national figure in the early 1950s. Recent leading Republicans include former Governor ] and Congressman ]; prominent Democrats include Governor ], Senators ] and ], and Congressman ].<ref name="conant2006">{{cite book|last=Conant|first=James K.|title=Wisconsin Politics and Government: America's Laboratory of Democracy|date=]|publisher=University of Nebraska Press|isbn=0803215487|chapter=1}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{Main|History of Wisconsin}} | |||

| ] at the mouth of the ]]] | |||

| {{main|History of Wisconsin}} | |||

| ===Early history=== | |||

| In 1634, Frenchman ] became Wisconsin's first European explorer, landing at Red Banks, near modern-day ] in search of a passage to the Orient. The French controlled the area until it was ceded to the British in 1763. | |||

| ] map, with the approximate state area highlighted]] | |||

| Wisconsin has been home to a wide variety of cultures over the past 14,000 years. The first people arrived around 10,000 BCE during the ]. These early inhabitants, called ], hunted now-extinct ] such as the ], a prehistoric ] skeleton unearthed along with spear points in southwest Wisconsin.<ref>{{Cite book | last1=Theler | first1=James | last2=Boszhardt | first2=Robert | title=Twelve Millennia: Archaeology of the Upper Mississippi River Valley | year=2003 |publisher=University of Iowa Press |location= Iowa City, Iowa |isbn=978-0-87745-847-0|page=59 }}</ref> After the ice age ended around 8000 BCE, people in the subsequent ] lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering food from wild plants. Agricultural societies emerged gradually over the ] between 1000 BCE to 1000 CE. Toward the end of this period, Wisconsin was the heartland of the "] culture", which built thousands of animal-shaped mounds across the landscape.<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Birmingham|first1=Robert|last2=Eisenberg|first2=Leslie|title=Indian Mounds of Wisconsin|year=2000 |publisher=University of Wisconsin Press|location=Madison, Wisconsin|isbn=978-0-299-16870-4|pages=100–110}}</ref> Later, between 1000 and 1500 CE, the ] and ] cultures built substantial settlements including the fortified village at ] in southeast Wisconsin.<ref>Birmingham 2000, pp. 152–56</ref> The Oneota may be the ancestors of the modern ] and ] nations who shared the Wisconsin region with the ] at the time of European contact.<ref>Birmingham 2000, pp. 165–67</ref> Other Native American groups living in Wisconsin when Europeans first settled included the ], ], ], ], and ], who migrated to Wisconsin from the east between 1500 and 1700.<ref>{{cite book|last=Boatman|first=John|editor-first=Donald| editor-last=Fixico|title=An Anthology of Western Great Lakes Indian History|publisher=University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee|year=1987|chapter=Historical Overview of the Wisconsin Area: From Early Years to the French, British, and Americans|oclc=18188646}}</ref> | |||

| Wisconsin was part of the ] from ] to ]. It was then governed as part of ] (1800-1809), ] (1809-1818), and ] (1818-1836).<ref name="whscreation">{{cite web |url= http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-014/?action=more_essay|title=The Creation of Wisconsin Territory|accessdate=2007-03-16|publisher=Wisconsin Historical Society}}</ref> Settlement began when the first two ]s opened in 1834.<ref name="whsgeneral">{{cite journal |last=Kmetz|first=Deborah|year=1995|title=U.S. General Land Office Survey Plat Maps|journal=Exchange|volume= 37|issue=3|url=http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/localhistory/articles/plat_maps.asp|accessdate= 2007-03-16}}</ref> ] was organized on ], ], and it became the 30th state on ] ]. | |||

| ===European settlements=== | |||

| The state mineral is ], otherwise known as lead sulfide, which reflects Wisconsin's early mining history. Many town names, such as ], recall a period in the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s, when Wisconsin was an important mining state. When Indian treaties opened up southwest Wisconsin to settlement, thousands of miners — many of them immigrants from ], ] — joined the "lead rush" in southwestern areas. At that time, Wisconsin produced more than half of the nation's lead; ], in the lead region, was briefly the state capital. By the 1840s, the easily accessible deposits were worked out, and experienced miners were drawn away to the ]. This period of mining before and during the early years of statehood led to the state's nickname, the "Badger State". Many miners and their families lived in the mines in which they worked until adequate above-ground shelters were built, and were thus compared to ]s.<ref name="badgers">{{cite web|title=Badger Notables: Badger Nickname|publisher=UWBadgers.com - The Official Web Site of Badger Athletics|url=http://www.uwbadgers.com/traditions/notables_120.html|accessdate=2006-10-22}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|New France|Canada (New France)|French and Indian War|Treaty of Paris (1763)|Province of Quebec (1763–1791)|Indian Reserve (1763)}} | |||

| ], depicted in a 1910 painting by Frank Rohrbeck, was probably the first European to explore Wisconsin. The mural is located in the ] in Green Bay.]] | |||

| The first European to visit what became Wisconsin was probably the French explorer ]. He canoed west from ] through the ] in 1634, and it is traditionally assumed that he came ashore near ] at ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Jean Nicolet|url=http://www.uwgb.edu/wisfrench/library/articles/nicolet.htm|author=Rodesch, Gerrold C.|year=1984|publisher=]|access-date=March 13, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130117084337/http://www.uwgb.edu/wisfrench/library/articles/nicolet.htm|archive-date=January 17, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> ] and ] visited Green Bay again in 1654–1666 and ] in 1659–1660, where they traded for fur with local Native Americans.<ref>{{cite web|title=Turning Points in Wisconsin History: Arrival of the First Europeans|url=http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-006/?action=more_essay|publisher=]|access-date=March 13, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220319211019/https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-006/?action=more_essay|archive-date=March 19, 2022|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1673, Jacques Marquette and ] became the first to record a journey on the ] all the way to the ] near ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Jaenen|first=Cornelius|year=1973|title=French colonial attitudes and the exploration of Jolliet and Marquette|journal=Wisconsin Magazine of History|volume=56|issue=4|pages=300–310|url=http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wmh/id/26553|access-date=January 31, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170202080523/http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wmh/id/26553|archive-date=February 2, 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> ] like ] continued to ply the ] across Wisconsin through the 17th and 18th centuries, but the French made no permanent settlements in Wisconsin before ] won control of the region following the ] in 1763. Even so, French traders continued to work in the region after the war, and some, beginning with ] in 1764, settled in Wisconsin permanently, rather than returning to British-controlled Canada.<ref name="Wisconsin Historical Society">{{cite web|title=Dictionary of Wisconsin History: Langlade, Charles Michel|url=http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/dictionary/index.asp?action=view&term_id=2266&search_term=Langlade%2C+Charles+Michel|publisher=]|access-date=March 13, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101204150014/http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/dictionary/index.asp?action=view&term_id=2266&search_term=Langlade%2C+Charles+Michel|archive-date=December 4, 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In the 1830-60 period, large numbers of Yankees from New England and New York flocked to Wisconsin. The New Yorkers were influential in bringing dairy farming to the state. As New York was the leading dairy state at the time, migrants from there brought with them the skills needed for dairy farming, as well as butter and cheese production.<ref name="whsrise">{{cite web|title=The Rise of Dairy Farming|publisher=Wisconsin Historical Society|url=http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-028/?action=more_essay|accessdate=2007-03-16}}</ref> | |||

| The British gradually took over Wisconsin during the French and Indian War, taking control of Green Bay in 1761 and gaining control of all of Wisconsin in 1763. Like the French, the British were interested in little but the fur trade. One notable event in the fur trading industry in Wisconsin occurred in 1791, when two free African Americans set up a fur trading post among the Menominee at present-day ]. The first permanent settlers, mostly ]s, some Anglo-]ers and a few African American freedmen, arrived in Wisconsin while it was under British control. Charles de Langlade is generally recognized as the first settler, establishing a trading post at Green Bay in 1745, and moving there permanently in 1764.<ref name="Wisconsin Historical Society"/> Settlement began at Prairie du Chien around 1781. The French residents at the trading post in what is now Green Bay, referred to the town as "La Baye". However, British fur traders referred to it as "Green Bay", because the water and the shore assumed green tints in early spring. The old French title was gradually dropped, and the British name of "Green Bay" eventually stuck. The region coming under British rule had virtually no adverse effect on the French residents as the British needed the cooperation of the French fur traders and the French fur traders needed the goodwill of the British. During the French occupation of the region licenses for fur trading had been issued scarcely and only to select groups of traders, whereas the British, in an effort to make as much money as possible from the region, issued licenses for fur trading freely, both to British and to French residents. The fur trade in what is now Wisconsin reached its height under British rule, and the first self-sustaining farms in the state were established as well. From 1763 to 1780, Green Bay was a prosperous community which produced its own foodstuff, built graceful cottages and held dances and festivities.<ref>Wisconsin, a Guide to the Badger State page 188</ref> | |||

| Other Yankees settled in towns or cities where they set up businesses, factories, mills, banks, schools, libraries, colleges, and voluntary societies. They created many ], Presbyterian and Methodist churches that still exist. The Yankees created the Republican party in 1854—the first local meeting in the country came in ]. They gave strong support to the Civil War effort, as well as to reforms such as abolition, women's suffrage and, especially, prohibition. | |||

| Joseph Roi built the ] in ] in 1776. Located in ], it is the ] from Wisconsin's early years and is listed on the ].<ref name="NRHP">{{cite news|last1=Anderson|first1=D. N.|title=Tank Cottage|url=https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/70000028_text|access-date=March 21, 2020|work=] Inventory-Nomination Form|publisher=National Park Service|date=March 23, 1970|archive-date=February 25, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225163106/https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/70000028_text|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Even larger numbers of Germans arrived, so that the state became over one-third German. Most became farmers; others moved to Milwaukee and smaller cities setting up breweries and becoming craftsmen, machinists and skilled workers who were in high demand as the state industrialized. The Germans were split along religious lines. Most Germans were Catholic or Lutheran, with some Lutherans forming the ] and others joining the ]. The Catholics and Lutherans created their own network of parochial schools, through grade 8. Smaller numbers of Germans were Methodists, Jews, or Freethinkers (especially intellectual refugees). Politically they tended toward the Democratic party, but 30-40% voted Republican. Whenever the Republicans seemed to support prohibition, they shifted toward the Democrats. When nativist Republicans, led by governor ], passed the ] in 1889 that would eliminate instruction in the German language, German-Americans revolted and helped elect the Democrats in 1890. In ], German culture came under heavy attack in Wisconsin. Senator LaFollette became their protector and Germans strongly supported his wing of the Republican party after that. | |||

| ===U.S. territory=== | |||

| Scandinavians comprise the third largest ethnic block, with Norwegians, Danes, Swedes, and Finns becoming farmers and lumberjacks in the western and northern districts. A large Danish settlement in Racine was the only large urban presence. The great majority were Lutheran, of various synods. The Scandinavians supported Prohibition and voted Republican; in the early 20th century they were the backbone of the LaFollette movement. Irish Catholics came to Milwaukee and Madison and smaller cities as railroad workers. They quickly became prominent in local government and in the Democratic party. They wrestled with the German Catholics for control of the Catholic church in the state. | |||

| {{Main|American Revolutionary War|Treaty of Paris (1783)|Northwest Ordinance|Northwest Territory|Indiana Territory|Illinois Territory|Michigan Territory|Organic act#List of organic acts|Wisconsin Territory}} | |||

| ] in ] was built in the 1810s by fur traders.]] | |||

| Wisconsin became a territorial possession of the United States in 1783 after the ]. In 1787, it became part of the ]. As territorial boundaries subsequently developed, it was then part of ] from 1800 to 1809, ] from 1809 to 1818, and ] from 1818 to 1836. However, the British remained in control until after the ], the outcome of which finally established an American presence in the area.<ref>{{cite book|title=Wisconsin: A History|last=Nesbit|first=Robert|year=1973|publisher=University of Wisconsin Press|location=Madison, WI|isbn=978-0-299-06370-2|pages=|url=https://archive.org/details/wisconsinhistory0000nesb/page/62}}</ref> Under American control, the economy of the territory shifted from fur trading to lead mining. The prospect of easy mineral wealth drew immigrants from throughout the U.S. and Europe to the lead deposits at ], ], and nearby areas. Some miners found shelter in the holes they had dug, and earned the nickname "badgers", leading to Wisconsin's identity as the "Badger State".<ref>{{cite web|title=Badger Nickname|url=http://www.uwbadgers.com/trads/nickname.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110323002815/http://www.uwbadgers.com/trads/nickname.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=March 23, 2011|publisher=University of Wisconsin|access-date=March 14, 2010}}</ref> The sudden influx of white miners prompted tension with the local Native American population. The ] of 1827 and the ] of 1832 culminated in the forced ] from most parts of the state.<ref>{{cite book|last=Nesbit|year=1973|isbn=978-0-299-06370-2|pages=|title=Wisconsin: a history|publisher=University of Wisconsin Press |url=https://archive.org/details/wisconsinhistory0000nesb/page/95}}</ref> | |||

| ===Name=== | |||

| "Wisconsin" is thought to be an English version of a French adaptation of an Indian word. It may come from the ] word ''Miskwasiniing'', meaning "Red-stone place," which was probably the name given to the ], and was recorded as ''Ouisconsin'' by the French and changed to its current form by the English. The modern Ojibwe name, however, is ''Wiishkoonsing'' or ''Wazhashkoonsing'', meaning "muskrat-lodge place" or "little muskrat place." Other theories are that the name comes from words meaning "Gathering of the Waters" or "Great Rock." ''Wisconsin'' originally was applied to the Wisconsin River, and later to the area as a whole when Wisconsin became a territory. | |||

| Following these conflicts, ] was created by an act of the ] on April 20, 1836. By fall of that year, the best prairie groves of the counties surrounding what is now Milwaukee were occupied by farmers from the ] states.<ref>Wisconsin, a Guide to the Badger State page 197</ref> | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| The state is bordered by the ]; ] and ] to the north; by ] to the east; by ] to the south; and by ] and ] to the west. The state's boundaries include the ] and ] in the west, and the ] in the northeast.] | |||

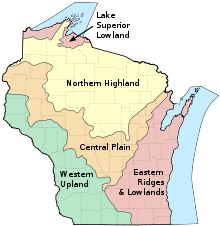

| With its location between the ] and the Mississippi River, Wisconsin is home to a wide variety of geographical features. The state is divided into five distinct regions. In the north, the ] occupies a belt of land along Lake Superior. Just to the south, the ] has massive mixed hardwood and coniferous forests including the 1.5 million acre ], as well as thousands of glacial lakes, and the state's highest point, ]. In the middle of the state, the ] possesses some unique sandstone formations like the ] in addition to rich farmland. The ] region in the southeast is home to many of Wisconsin's largest cities. In the southwest, the ] is a rugged landscape with a mix of forest and farmland, including many bluffs on the ]. This region is part of the ], which also includes portions of ], ], and ]. This area was not covered by ]s during the most recent ice age, the ].] of southwestern Wisconsin is characterized by bluffs carved in ] rock by water from melting ] glaciers.]] | |||

| ===Statehood=== | |||

| The varied landscape of Wisconsin makes the state a vacation destination popular for outdoor recreation. Winter events include skiing, ice fishing and snowmobile derbies. Wisconsin has many lakes of varied size; in fact Wisconsin contains 11,188 ]s (28,977 ]) of water, more than all but three other states (], ] & ]). The distinctive ], which extends off the eastern coast of the state, contains one of the state's most beautiful tourist destinations, ]. The area draws thousands of visitors yearly to its quaint villages, seasonal cherry picking, and ever-popular ]s. | |||

| {{Main|Admission to the Union|List of U.S. states by date of admission to the Union}} | |||

| ] celebrating the 100th anniversary of Wisconsin statehood, featuring the state capitol building and map of Wisconsin.]] | |||

| The ] facilitated the travel of both ] settlers and European immigrants to Wisconsin Territory. Yankees from New England and ] seized a dominant position in law and politics, enacting policies that marginalized the region's earlier Native American and French-Canadian residents.<ref>{{Cite book| publisher = Cambridge University Press| isbn = 9781107052864| last = Murphy| first = Lucy Eldersveld| title = Great Lakes Creoles: a French-Indian community on the northern borderlands, Prairie du Chien, 1750–1860| location = New York| date = 2014| pages=108–147}}</ref> Yankees also speculated in real estate, platted towns such as Racine, Beloit, Burlington, and Janesville, and established schools, civic institutions, and ] churches.<ref>The Expansion of New England: The Spread of New England Settlement and Institutions to the Mississippi River, 1620–1865 by Lois Kimball Mathews page 244</ref><ref>New England in the Life of the World: A Record of Adventure and Achievement By Howard Allen Bridgman page 77</ref><ref>"When is Daddy Coming Home?": An American Family During World War II By Richard Carlton Haney page 8</ref> At the same time, many ], Irish, ], and other immigrants also settled in towns and farms across the territory, establishing ] and ] institutions. | |||

| Areas under the management of the ] include the following: | |||

| *] along Lake Superior | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *]. | |||

| The growing population allowed Wisconsin to gain statehood on May 29, 1848, as the 30th state. Between 1840 and 1850, Wisconsin's non-Indian population had swollen from 31,000 to 305,000. More than a third of residents (110,500) were foreign born, including 38,000 Germans, 28,000 British immigrants from England, Scotland, and Wales, and 21,000 Irish. Another third (103,000) were Yankees from New England and western New York state. Only about 63,000 residents in 1850 had been born in Wisconsin.<ref>Robert C. Nesbit. ''Wisconsin: A History''. 2nd ed. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989, p. 151.</ref> | |||

| ===Climate=== | |||

| ], the first ], was a ]. Dewey oversaw the transition from the territorial to the new state government.<ref name="1960bio">{{cite book |last=Toepel |first=M. G. |editor-first=Hazel L. |editor-last=Kuehn |title=The Wisconsin Blue Book, 1960 |year=1960 |url=http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=header&id=WI.WIBlueBk1960&isize=M |chapter=Wisconsin's Former Governors, 1848–1959 |chapter-url=http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=turn&entity=WI.WIBlueBk1960.p0087&isize=M |publisher=Wisconsin Legislative Reference Library |access-date=September 17, 2008 |pages=71–74 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110604152221/http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=header&id=WI.WIBlueBk1960&isize=M |archive-date=June 4, 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> He encouraged the development of the state's infrastructure, particularly the construction of new roads, railroads, canals, and harbors, as well as the improvement of the ] and ]s.<ref name="1960bio" /> During his administration, the ] was organized.<ref name="1960bio" /> Dewey, an ], was the first of many Wisconsin governors to advocate against the spread of ] into new states and territories.<ref name="1960bio" /> | |||

| The Wisconsin climate is great for growing crops with a wet season falling in spring and summer, bringing with it almost two-thirds of yearly precipitation. It brings cold snowy ]s, which are what Wisconsin is well-known for. The highest temperature ever recorded in Wisconsin was in the Wisconsin Dells, on July 13, 1936, and was 114°F. The lowest temperature ever recorded in Wisconsin was in Couderay, on both February 2 and 4, 1996, and was –55°F.<ref name="uwexclimate">{{cite web|url=http://www.uwex.edu/sco/stateclimate.html|title=Climate of Wisconsin|accessdate=2007-03-16||last=Benedetti|first=Michael|publisher=The University of Wisconsin-Extension}}</ref> | |||

| {{Further|Pioneer Women in Wisconsin}} | |||

| == |

===Civil War=== | ||

| {{Main article|Wisconsin in the American Civil War}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] in ] held the nation's first meeting of the ].]] ] with ]]] | |||

| Politics in early Wisconsin were defined by the greater national debate over slavery. A free state from its foundation, Wisconsin became a center of northern ]. The debate became especially intense in 1854 after ], a runaway slave from ], was captured in ]. Glover was taken into custody under the Federal ], but a mob of abolitionists stormed the prison where Glover was held and helped him escape to Canada. In a trial stemming from the incident, the ] ultimately declared the Fugitive Slave Law unconstitutional.<ref>{{cite book|title=Leading Events of Wisconsin History|last=Legler|first=Henry|year=1898|publisher=Sentinel|location=Milwaukee, Wis.|pages=226–229|url=http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/WIReader/WER1124.html|chapter=Rescue of Joshua Glover, a Runaway Slave|access-date=October 17, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171018071024/http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/WIReader/WER1124.html|archive-date=October 18, 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> The ], founded on March 20, 1854, by anti-slavery expansion activists in ], grew to dominate state politics in the aftermath of these events.<ref>{{cite book|last=Nesbit|year=1973|isbn=978-0-299-06370-2|pages=|title=Wisconsin: a history|publisher=University of Wisconsin Press |url=https://archive.org/details/wisconsinhistory0000nesb/page/238}}</ref> During the ], around 91,000 troops from Wisconsin fought for the ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Turning Points in Wisconsin History: The Iron Brigade, Old Abe and Military Affairs|url=http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-023/?action=more_essay|publisher=]|access-date=March 13, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101204150829/http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-023/?action=more_essay|archive-date=December 4, 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| {{USCensusPop | |||

| |1820 = 1444 | |||

| |1830 = 3635 | |||

| |1840 = 30945 | |||

| |1850 = 305391 | |||

| |1860 = 775881 | |||

| |1870 = 1054670 | |||

| |1880 = 1315497 | |||

| |1890 = 1693330 | |||

| |1900 = 2069042 | |||

| |1910 = 2333860 | |||

| |1920 = 2632067 | |||

| |1930 = 2939006 | |||

| |1940 = 3137587 | |||

| |1950 = 3434575 | |||

| |1960 = 3951777 | |||

| |1970 = 4417731 | |||

| |1980 = 4705767 | |||

| |1990 = 4891769 | |||

| |2000 = 5363675 | |||

| |estimate = 5536201 | |||

| |estyear = 2005 | |||

| |estref = <ref name="uscbquick">{{cite web|url=http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/55000.html|title=QuickFacts: Wisconsin|publisher=]|accessdate=2007-03-01}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| The state has always been ethnically ]. Large numbers of Germans arrived between 1850 and 1900, centering in ], but also settling in many small cities and farm areas in the southeast. Scandinavians settled in lumbering and farming areas in the northwest. Small colonies of ], ], ] and other groups came to the state. Irish Catholics mostly came to the cities. After 1900, ] immigrants came to Milwaukee, followed by ] from 1940 on. | |||

| ===Economic progress=== | |||

| According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of 2006, Wisconsin has an estimated population of 5,556,506, which is an increase of 28,862, or 0.5%, from the prior year and an increase of 192,791, or 3.6%, since the year 2000. This includes a natural increase since the last census of 144,051 people (that is 434,966 births minus 290,915 deaths) and an increase from net migration of 65,781 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 56,557 people, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 9,224 people. The top 5 states with a net increase of migration into Wisconsin are 1) Illinois, 2) California, 3) Indiana 4) New York and 5) Pennsylvania.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} The ] of Wisconsin is located in ], in the city of ].<ref name="uscb2002">{{cite web |url=http://www.census.gov/geo/www/cenpop/statecenters.txt|title=Population and Population Centers by State: 2000|accessdate=2007-03-16|date=]|format=TXT|publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ] in ] was built in 1903, as dairy farming spread across the state.]] | |||

| Wisconsin's economy also diversified during the early years of statehood. While lead mining diminished, agriculture became a principal occupation in the southern half of the state. Railroads were built across the state to help transport grains to market, and industries like ] in Racine were founded to build agricultural equipment. Wisconsin briefly became one of the nation's leading producers of wheat during the 1860s.<ref>{{cite book|last=Nesbit|year=1973|isbn=978-0-299-06370-2|page=|title=Wisconsin: a history|publisher=University of Wisconsin Press |url=https://archive.org/details/wisconsinhistory0000nesb/page/273}}</ref> Meanwhile, the lumber industry dominated in the heavily forested northern sections of Wisconsin, and sawmills sprang up in cities like ], ], and ]. These economic activities had dire environmental consequences. By the close of the 19th century, intensive agriculture had devastated soil fertility, and lumbering had deforested most of the state.<ref>{{cite book|last=Nesbit|year=1973|isbn=978-0-299-06370-2|pages=|title=Wisconsin: a history|publisher=University of Wisconsin Press |url=https://archive.org/details/wisconsinhistory0000nesb/page/281}}</ref> These conditions forced both wheat agriculture and the lumber industry into a precipitous decline. | |||

| As of 2004, there are 229,800 foreign-born residents in the state (4.2% of the state population), and an estimated 41,000 ] living in the state, accounting for 18% of the foreign-born population.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | |||

| {{US Demographics}} | |||

| The five largest ancestry groups in Wisconsin are: ] (42.6%), ] (10.9%), ] (9.3%), ] (8.5%), ] (6.5%) | |||

| Beginning in the 1890s, farmers in Wisconsin shifted from wheat to dairy production to make more sustainable and profitable use of their land. Many immigrants carried cheese-making traditions that, combined with the state's suitable geography and dairy research led by ] at the ], helped the state build a reputation as "America's Dairyland".<ref>{{cite book|title= The Progressive Era, 1893–1914|series=History of Wisconsin|volume=4|first=John|last=Buenker|publisher=State Historical Society of Wisconsin|location=Madison, WI|year=1998|editor-first=William Fletcher|editor-last=Thompson|isbn=978-0-87020-303-9|pages=25, 40–41, 62}}</ref> Meanwhile, conservationists including ] helped re-establish the state's forests during the early 20th century,<ref>{{cite web|title=Turning Points in Wisconsin History: The Modern Environmental Movement|url=http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-048/?action=more_essay|publisher=]|access-date=March 13, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101204150526/http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-048/?action=more_essay|archive-date=December 4, 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> paving the way for a more renewable lumber and ]ing industry as well as promoting recreational tourism in the northern woodlands. Manufacturing also boomed in Wisconsin during the early 20th century, driven by an immense immigrant workforce arriving from Europe. Industries in cities like Milwaukee ranged from brewing and food processing to heavy machine production and tool-making, leading Wisconsin to rank 8th among U.S. states in total product value by 1910.<ref>{{cite book|title= The Progressive Era, 1893–1914|series=History of Wisconsin|volume=4|first=John|last=Buenker|publisher=State Historical Society of Wisconsin|location=Madison, WI|year=1998|editor-first=William Fletcher|editor-last=Thompson|isbn=978-0-87020-303-9|pages=80–81}}</ref> | |||

| Wisconsin, with many cultural remnants of its heavy German settlement, is known as perhaps the most "]" state in the Union. People of Scandinavian descent, especially ], are heavily concentrated in some western parts of the state. Wisconsin has the highest percentage of residents of Polish ancestry of any state. Menominee County is the only county in the eastern United States with an American Indian majority. | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| 86% of Wisconsin's African American population lives in one of five cities: ], ], ], ] and ] while Milwaukee itself is home to nearly three-fourths of the state's African Americans. Milwaukee ranks in the top 10 major U.S. cities with the highest number of African Americans per capita. In the ] region, only ] and ] have a higher percentage of African Americans. | |||

| ] addresses an assembly, 1905]] | |||

| ] campaigning, 1916. Wisconsin was among the earliest states to ratify the ].<ref>{{Cite web|last=|first=|date=|title=Suffrage 2020 Illinois|url=https://suffrage2020illinois.org/|access-date=January 16, 2021|website=Suffrage 2020 Illinois|language=en}}</ref>]] | |||

| The early 20th century was also notable for the emergence of ] politics championed by ]. Between 1901 and 1914, Progressive Republicans in Wisconsin created the nation's first comprehensive statewide ] system,<ref>{{cite book|title=The American direct primary: party institutionalization and transformation in the North |last=Ware|first=Alan|year=2002|publisher=]|location=Cambridge, England|isbn=978-0-521-81492-8|page=118}}</ref> the first effective ] law,<ref>{{cite web|last=Ranney|first=Joseph|title=Wisconsin's Legal History: Law and the Progressive Era, Part 3: Reforming the Workplace|url=http://www.wisbar.org/AM/TemplateRedirect.cfm?template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=35854|archive-url=https://archive.today/20120918150059/http://www.wisbar.org/AM/TemplateRedirect.cfm?template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=35854|url-status=dead|archive-date=September 18, 2012|access-date=March 13, 2010}}</ref> and the first state ],<ref>{{cite journal|last=Stark|first=John|year=1987|title=The Establishment of Wisconsin's Income Tax|journal=Wisconsin Magazine of History|volume=71|issue=1|pages=27–45|url=http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wmh/id/36669|access-date=January 31, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170202080527/http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wmh/id/36669|archive-date=February 2, 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> making taxation proportional to actual earnings. | |||

| 33% of Wisconsin's Asian population is ], with significant communities in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| During ], due to the neutrality of Wisconsin and many ], ], and ] which made up 30 to 40 percent of the state population, Wisconsin would gain the nickname "Traitor State" which was used by many "hyper patriots".<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Cary |first=Lorin Lee |date=1969 |title=The Wisconsin Loyalty Legion, 1917–1918 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/4634484 |journal=The Wisconsin Magazine of History |volume=53 |issue=1 |pages=33–50 |jstor=4634484 |issn=0043-6534 |access-date=February 2, 2024 |archive-date=February 2, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240202010328/https://www.jstor.org/stable/4634484 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=October 10, 2012 |title=Expression Leads to Repression |url=https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS3418 |access-date=February 1, 2024 |website=Wisconsin Historical Society |language=en |archive-date=April 1, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160401193504/http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Content.aspx?dsNav=N:4294963828-4294963805&dsRecordDetails=R:CS3418 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Falk |first=Karen |date=1942 |title=Public Opinion in Wisconsin during World War I |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/4631476 |journal=The Wisconsin Magazine of History |volume=25 |issue=4 |pages=389–407 |jstor=4631476 |issn=0043-6534 |access-date=February 2, 2024 |archive-date=February 2, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240202010329/https://www.jstor.org/stable/4631476 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=August 21, 2013 |title=ODD WISCONSIN: State denounced as 'traitor' in 1917 |url=https://lacrossetribune.com/courierlifenews/lifestyles/odd-wisconsin-state-denounced-as-traitor-in-1917/article_6c65843a-0ad5-11e3-8caa-001a4bcf887a.html |access-date=February 2, 2024 |website=La Crosse Tribune |language=en |archive-date=February 2, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240202010329/https://lacrossetribune.com/courierlifenews/lifestyles/odd-wisconsin-state-denounced-as-traitor-in-1917/article_6c65843a-0ad5-11e3-8caa-001a4bcf887a.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| 6.4% of Wisconsin's population was reported as under 5, 25.5% under 18, and 13.1% were 65 or older. Females made up approximately 50.6% of the population. | |||

| As the war raged on in Europe, ], leader of the anti-war movement in Wisconsin. led a group of progressive senators in blocking a bill by president ] which would have armed merchant ships with guns. Many Wisconsin politicians such as ] and ] were accused of having divided loyalties.<ref>''The History of Wisconsin 1914–1940'' by Paul W. Glad, 1990. State Historical Society of Wisconsin, p.309-310.</ref> Even with outspoken opponents to the war, at the onset of the war many Wisconsinites would abandon neutrality. Businesses, labor and farms all enjoyed prosperity from the war. With over 118,000 going into military service, Wisconsin was the first state to report for the national drafts conducted by the ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=August 3, 2012 |title=World War I |url=https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS422 |access-date=February 2, 2024 |website=Wisconsin Historical Society |language=en |archive-date=February 2, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240202010329/https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS422 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Religion=== | |||

| The largest denominations are Roman Catholic, ], ] and ] Lutherans. The religious affiliations of the people of Wisconsin are shown in the list below:<ref name="carroll2000">{{cite book|last=Carroll|first=Brett E.||title=The Routledge Historical Atlas of Religion in America|series=Routledge Atlases of American History|date=]|publisher=]|isbn=0415921376}}</ref> | |||

| * ] – 85% | |||

| ** ] – 55% | |||

| *** ] – 23% | |||

| *** ] – 7% | |||

| *** ] – 6% | |||

| *** ] – 2% | |||

| *** ] – 2% | |||

| *** Other Protestant or general Protestant – 15% | |||

| ** ] – 29% | |||

| ** Other Christian – 1% | |||

| * Other Religions – 1% | |||

| * Non-Religious – 14% | |||

| The progressive ] also promoted the statewide expansion of the University of Wisconsin through the ] system at this time.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stark|first=Jack|chapter=The Wisconsin Idea: The University's Service to the State|title=The State of Wisconsin Blue Book, 1995–1996|location=Madison|publisher=Legislative Reference Bureau|year=1995|pages=99–179|oclc=33902087|chapter-url=http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=article&did=WI.WIBlueBk1995.i0009&id=WI.WIBlueBk1995&isize=L|access-date=January 31, 2017|archive-date=October 17, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181017001801/http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=article&did=WI.WIBlueBk1995.i0009&id=WI.WIBlueBk1995&isize=L|url-status=live}}</ref> Later, UW economics professors ] and Harold Groves helped Wisconsin create the first ] program in the United States in 1932.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Nelson|first=Daniel|year=1968|title=The Origins of Unemployment Insurance in Wisconsin|journal=Wisconsin Magazine of History|volume=51|issue=2|pages=109–21|url=http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wmh/id/31447|access-date=January 31, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170202080531/http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wmh/id/31447|archive-date=February 2, 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> Other ] scholars at the university generated the plan that became the New Deal's ] of 1935, with Wisconsin expert ] playing the key role.<ref>Arthur J. Altmeyer, "The Wisconsin Idea and Social Security." ''Wisconsin Magazine of History'' (1958) 42#1: 19–25.</ref> | |||

| ==Economy== | |||

| ] in ] is Wisconsin's tallest building.]] | |||

| According to the 2004 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis report, Wisconsin’s gross state product was $211.7 billion. The per capita personal income was $32,157 in 2004. | |||

| In the immediate aftermath of ], citizens of Wisconsin were divided over issues such as creation of the ], support for the European recovery, and the growth of the ]'s power. However, when Europe divided into Communist and capitalist camps and the ] succeeded in 1949, public opinion began to move towards support for the protection of democracy and capitalism against Communist expansion.<ref>A Short History of Wisconsin By Erika Janik page 149</ref> | |||

| The economy of Wisconsin is driven by ], ], and ]. Although manufacturing accounts for a far greater part of the state's income than farming, Wisconsin is often perceived as a farming state. It produces more dairy products than any other state in the United States except ], and leads the nation in ] production. Although California has overtaken Wisconsin in the production of milk and butter, Wisconsin still produces more milk per capita than any other state in the Union except ].<ref name="fmma2002">{{cite news|title=2001 Milk Production|url=http://www.fmmacentral.com/PDFdata/msb0202.pdf|format=PDF|work=Marketing Service Bulletin|publisher=]|date=February 2002|accessdate=2007-03-16}}</ref> Wisconsin is so proud of its dairy and agricultural heritage that it chose for its ] design a Holstein cow, an ear of corn, and a wheel of cheese. Wisconsin ranks first in the production of ] for ], ], ], and ] for processing. Wisconsin is also a leading producer of ]s, ]es, ]s, tart ], ], and ] for processing. | |||

| Wisconsin took part in several political extremes in the mid to late 20th century, ranging from the ] crusades of Senator ] in the 1950s to the radical antiwar protests at UW-Madison that culminated in the ] in August 1970. The state undertook ] under Republican Governor ] during the 1990s.<ref>{{cite web|title=Tommy Thompson: Human Services Reformer|website = ]|url=https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/story?id=122179&page=1|date=September 4, 2004|access-date=March 13, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110130132917/https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/story?id=122179&page=1|archive-date=January 30, 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> The state's economy also underwent further transformations towards the close of the 20th century, as heavy industry and manufacturing declined in favor of a ] based on medicine, education, agribusiness, and tourism. | |||

| ===21st century=== | |||

| In 2011, Wisconsin became the focus of some controversy when newly elected governor ] proposed and then successfully passed and enacted ], which made large changes in the areas of collective bargaining, compensation, retirement, health insurance, and sick leave of public sector employees, among other changes.<ref>{{cite news|last=Condon|first=Stephanie|url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/wisconsin-gov-scott-walker-signs-anti-union-bill-but-democrats-say-theyre-the-political-victors/|title=Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker signs anti-union bill – but Democrats say they're the political victors|work=CBS News|date=March 11, 2011|access-date=March 12, 2011|archive-date=March 12, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110312162805/http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-503544_162-20042122-503544.html|url-status=live}}</ref> A ] by union supporters took place that year in protest to the changes, and Walker survived ], becoming the first governor in United States history to do so.<ref>{{cite news|last=Montopoli|first=Brian|title=CBS News: Scott Walker wins Wisconsin recall election|url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/scott-walker-wins-wisconsin-recall-election/|newspaper=CBS News|date=June 5, 2012|access-date=January 20, 2017|archive-date=November 10, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131110170530/http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-503544_162-57447954-503544/wisconsin-recall-walker-opens-slight-lead-as-votes-are-counted/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| {{Main|Geography of Wisconsin}} | |||

| {{stack| | |||

| ] | |||

| ] of southwestern Wisconsin is characterized by bluffs carved in ] rock by water from melting ] glaciers. Pictured is the confluence of the ] and ] rivers.]] | |||

| ] are located on the shorelines of the ] in ].]] | |||

| }} | |||

| Wisconsin is in the ] and is part of both the ] and the ]. The state has a total area of {{Convert|65,496|sqmi|km2}}. Wisconsin is bordered by the ]; ] and ] to the north; by ] to the east; by ] to the south; and by ] to the southwest and ] to the northwest. A border dispute with Michigan was settled by two cases, both ], in 1934 and 1935. The state's boundaries include the ] and ] in the west, and the ] in the northeast.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nps.gov/subjects/rivers/wisconsin.htm |website=National Park Service |access-date=June 21, 2024 |title=Wisconsin - Rivers (U.S. National Park Service) }}</ref> | |||

| Lying between the ] and the Mississippi River, Wisconsin has a wide variety of geographical features. The state is divided into five distinct regions. In the north, the ] occupies a belt of land along Lake Superior. Just to the south, the ] has massive mixed hardwood and coniferous forests including the {{convert|1500000|acre|adj=on|abbr=off}} ], as well as thousands of glacial lakes, and the state's highest point, ]. In the middle of the state, the ] has some unique ] formations like the ] in addition to rich farmland. The ] region in the southeast is home to many of Wisconsin's largest cities. The ridges include the ] that stretches from New York, the ] and the ].<ref name=Martin1965>{{cite book|isbn=978-0-299-03475-7|url=https://archive.org/details/physicalgeograph0000mart|url-access=registration|page=|quote=Black River Escarpment.|title=The physical geography of Wisconsin|publisher=]|year=1965|author=Lawrence Martin|access-date=September 14, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.wisconline.com/wisconsin/geoprovinces/easternridges.html|title=The Eastern Ridges and Lowlands of Wisconsin|publisher=Wisconsin Online|access-date=September 14, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20010209021338/http://www.wisconline.com/wisconsin/geoprovinces/easternridges.html|archive-date=February 9, 2001 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20010209021338/http://www.wisconline.com/wisconsin/geoprovinces/easternridges.html |archivedate=February 9, 2001 |url=http://www.wisconline.com/wisconsin/geoprovinces/easternridges.html |title=The Eastern Ridges and Lowlands of Wisconsin |first=Lawrence |last=Martin |work=Wisconline.com |accessdate=September 14, 2010 |date=1965 }}</ref> In the southwest, the ] is a rugged landscape with a mix of forest and farmland, including many bluffs on the Mississippi River, and the ]. This region is part of the ], which also includes parts of Iowa, Illinois, and Minnesota. Overall, 46% of Wisconsin's land area is covered by forest. | |||

| Wisconsin has geologic formations and deposits that vary in age from over three billion years to several thousand years, with most rocks being millions of years old.<ref>{{cite map|author=Mudrey, M.G.|author2=Brown, B.A.|author3=Greenberg, J.K.|year=1982|title=Bedrock Geologic Map of Wisconsin|publisher=University of Wisconsin Extension}}</ref> The oldest geologic formations were created over 600 million years ago during the ], the majority below the glacial deposits. Much of the Baraboo Range consists of ] and other Precambrian ].<ref name="Hanson">Hanson, G. F., {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140222184825/http://wisconsingeologicalsurvey.org/pdfs/IC14.pdf|date=February 22, 2014}}, The University of Wisconsin Extension, November 1970, Information Circular 14</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=April 1981|title=Bedrock Geology of Wisconsin|url=https://wgnhs.wisc.edu/pubshare/M067.pdf|url-status=live|access-date=October 14, 2021|archive-date=August 4, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210804145204/https://wgnhs.wisc.edu/pubshare/M067.pdf}}</ref> This area was not covered by ]s during the most recent ice age, the ]. ] has a soil rarely found outside the county called ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_019841.pdf|title=Wisconsin State Soil: Antigo Silt Loam|author=United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service|date=April 1999|access-date=October 17, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170516155048/https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_019841.pdf|archive-date=May 16, 2017}}</ref> | |||

| The state has more than 12,000 named rivers and streams, totaling {{Convert|84,000|mile|km|abbr=}} in length.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Rivers {{!}} Wisconsin DNR|url=https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/rivers|access-date=October 30, 2020|website=dnr.wisconsin.gov|archive-date=October 30, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201030215318/https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/rivers|url-status=live}}</ref> It has over 15,000 named lakes, totaling about {{Convert|1|e6acre|km2|abbr=|spell=}}. ] is the largest inland lake, with over {{Convert|137,700|acres|km2|abbr=}}, and {{Convert|88|miles|km|abbr=}} of shoreline. Along the two Great Lakes, Wisconsin has over {{Convert|500|mi|km}} of shoreline.<ref name="Martin (1916) p. 21">{{harvp|Martin|1916|p=}}</ref> Many of the ] are in the Great Lakes; many surround the ] in Lake Michigan or are part of the ] in Lake Superior.<ref>{{cite web |title=Door Co. Map |url=https://wisconsindot.gov/Documents/travel/road/hwy-maps/county-maps/door.pdf |website=Door Co. Dept. of Transportation |access-date=December 29, 2020 |archive-date=February 1, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210201004227/https://wisconsindot.gov/Documents/travel/road/hwy-maps/county-maps/door.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The Mississippi River and inland lakes and rivers contain the rest of Wisconsin's islands. | |||

| Areas under the protection of the ] include the ], ], and portions of the ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nps.gov/state/wi/index.htm |title=Wisconsin |publisher=National Park Service |access-date=July 24, 2024 }}</ref> There are an additional 18 ] in the state that include dune and swales, swamps, bogs, and old-growth forests. Wisconsin has ], covering more than {{convert|60570|acres|km2}} in state parks and state recreation areas maintained by the ]. The Division of Forestry manages a further {{convert|471329|acres|km2}} in ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.milwaukeemag.com/your-guide-to-wisconsins-50-state-parks/ |title=Your Guide to Wisconsin's 50 State Parks |author=Watters, Alli |date=July 15, 2024 |publisher=Milwaukee Magazine |access-date=October 7, 2024 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Climate=== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{further|Climate change in Wisconsin}} | |||

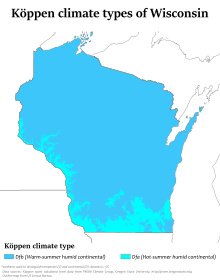

| Most of Wisconsin is classified as warm-summer ] (] ''Dfb''), while southern and southwestern portions are classified as hot-summer humid continental climate (Köppen ''Dfa''). The highest temperature ever recorded in the state was in the Wisconsin Dells, on July 13, 1936, where it reached 114 °F (46 °C). The lowest temperature ever recorded in Wisconsin was in the village of ], where it reached −55 °F (−48 °C) on both February 2 and 4, 1996. Wisconsin also receives a large amount of regular snowfall averaging around {{convert|40|in|cm}} in the southern portions with up to {{convert|160|in|cm}} annually in the Lake Superior ] each year.<ref name="uwexclimate">{{cite web|url=http://www.uwex.edu/sco/stateclimate.html|title=Climate of Wisconsin|access-date=March 16, 2007|last=Benedetti|first=Michael|publisher=The University of Wisconsin–Extension|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130117094615/http://www.uwex.edu/sco/stateclimate.html|archive-date=January 17, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Given Wisconsin's strong agricultural tradition, it is not surprising that a large part of the state's manufacturing sector deals with food processing. Some well known food brands produced in Wisconsin include ], ] and ] frozen pizza, ] ], and ]. ] alone employs over five thousand people in the state. Milwaukee is a major producer of ] and the home of ]'s world headquarters, the nation's second largest brewer. ], the Blue Ribbon of beers, used to be a cornerstone brewery within the City of ], but its heyday has long since passed when they closed up shop in the early 1990's. | |||

| {{sort under}} | |||

| {| class="toccolours" align="right" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="0" style="margin:0 0 1em 1em; font-size: 95%; clear:right;" | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable sort-under" "text-align:center; font-size:90%;" | | |||

| |+ '''Monthly normal high and low temperatures for selected Wisconsin cities''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" | City | |||

| | colspan="2" bgcolor="#ccccff" align="center" | '''''Badger State''''' | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Jan | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Feb | |||

| | ]: | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Mar | |||

| | ] | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Apr | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | May | |||

| | State Domesticated<br>Animal: | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Jun | |||

| | Dairy ] | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Jul | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Aug | |||

| | State Wild Animal: | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Sep | |||

| | ] | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Oct | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Nov | |||

| | State Beverage: | |||

| ! style="background-color: #e5afaa;" data-sort-type="number" | Dec | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- style="background: #f8f3ca;" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background: #f8f3ca;" | ] | |||

| | State Fruit: | |||

| | 25/10<br />(−4/−12) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 29/13<br />(−2/−11) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 40/23<br />(5/−5) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 55/35<br />(13/1) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 67/45<br />(19/7) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 76/55<br />(25/13) | |||

| | State Capital: | |||

| | 81/59<br />(27/15) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 79/58<br />(26/14) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 71/49<br />(22/10) | |||

| | State Dog: | |||

| | 58/38<br />(14/4) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 43/28<br />(6/−2) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 30/15<br />(−1/−9) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| |- style="background: #c5dfe1;" | |||

| | ] | |||

| ! style="background: #c5dfe1;" | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | 19/0<br />(−7/−18) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 26/4<br />(−4/−16) | |||

| | Wood ] | |||

| | 36/16<br />(2/−9) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 49/29<br />(9/−2) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 65/41<br />(18/5) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 73/50<br />(23/10) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 76/56<br />(25/13) | |||

| | State Grain: | |||

| | 75/54<br />(24/12) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 65/46<br />(18/8) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 53/35<br />(12/2) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 36/22<br />(2/−6) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 24/8<br />(−5/−14) | |||

| |- | |||

| |- style="background: #f8f3ca;" | |||

| | ]: | |||

| ! style="background: #f8f3ca;" | ] | |||

| | ''Forward'' | |||

| | 26/6<br />(−3/−14) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 32/13<br />(0/−11) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 45/24<br />(7/−4) | |||

| | "]" | |||

| | 60/37<br />(16/3) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 72/49<br />(22/9) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 81/58<br />(27/14) | |||

| | Sugar ] | |||

| | 85/63<br />(29/17) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 82/61<br />(28/16) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | |

| 74/52<br />(23/11) | ||

| | 61/40<br />(16/4) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 44/27<br />(7/−3) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 30/14<br />(−1/−10) | |||

| | Red ] | |||

| |- style="background: #c5dfe1;" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background: #c5dfe1;" | ] | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 27/11<br />(−3/−12) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 32/15<br />(0/−9) | |||

| |- | |||

| | 44/25<br />(7/−4) | |||

| | ]: | |||

| | 58/36<br />(14/2) | |||

| | ] | |||