| Revision as of 17:56, 12 December 2007 editOrangemarlin (talk | contribs)30,771 edits Cleaned up reference.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:41, 3 January 2025 edit undoRuslik0 (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Administrators54,780 editsm Reverted edit by 81.99.7.102 (talk) to last version by T g7Tag: Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Viral disease caused by the varicella zoster virus}} | |||

| {{dablink|"Shingles" redirects here, for other uses of the term, see ].}} | |||

| {{Other uses|Shingle (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{DiseaseDisorder infobox | | |||

| {{Redirect|Zoster}} | |||

| Name = Herpes zoster | | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| ICD10 = {{ICD10|B|02||b|00}} | | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} | |||

| ICD9 = {{ICD9|053}} | | |||

| {{Infobox medical condition (new) | |||

| ICDO = | | |||

| | name = Shingles | |||

| | synonyms = Herpes zoster | |||

| | image = Herpes zoster neck.png | |||

| | caption = Herpes zoster blisters on the neck and shoulder | |||

| MedlinePlus = 000858 | | |||

| | field = ] | |||

| eMedicineSubj = med | | |||

| | symptoms = Painful rash | |||

| eMedicineTopic = 1007 | | |||

| | complications = ], ], ], ]<ref name=Pink2015/> | |||

| eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|derm|180}} {{eMedicine2|emerg|823}} {{eMedicine2|oph|257}} {{eMedicine2|ped|996}} | | |||

| | onset = | |||

| DiseasesDB = 29119 | | |||

| | duration = 2–4 weeks<ref name=CDC2014Sym/> | |||

| | causes = ] (VZV)<ref name=Pink2015/> | |||

| | risks = Old age, ], having had chickenpox before 18 months of age<ref name=Pink2015/> | |||

| | diagnosis = Based on symptoms<ref name=NEJM2013/> | |||

| | differential = ], chest pain, ]s, ]<ref>{{cite web | title=Herpes Zoster Diagnosis, Testing, Lab Methods | date=April 2022 | publisher=] (CDC) | url=https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/hcp/diagnosis-testing.html | access-date=10 June 2022 | archive-date=3 June 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220603200709/https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/hcp/diagnosis-testing.html | url-status=live }} {{PD-notice}}</ref> | |||

| | prevention = ]<ref name=Pink2015/> | |||

| | treatment = | |||

| | medication = ] (if given early), pain medication<ref name=NEJM2013/> | |||

| | frequency = 33% (at some point)<ref name=Pink2015/> | |||

| | deaths = 6,400 (with chickenpox)<ref name=GBD2015De>{{cite journal| vauthors = ((GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators)) |title=Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015|journal=Lancet|date=8 October 2016|volume=388|issue=10053|pages=1459–1544|pmid=27733281|pmc=5388903|doi=10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1}}</ref> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Shingles''', also known as '''herpes zoster''' or '''zona''',<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-09-18 |title=Herpes zoster {{!}} Shingles, Varicella-Zoster, Pain Relief {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/science/herpes-zoster |access-date=2024-10-26 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> is a ] characterized by a painful ] with blisters in a localized area.<ref name=CDC2014Sym/><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Sivapathasundharam B, Gururaj N, Ranganathan K | chapter = Viral Infections of the Oral Cavity | veditors = Rajendran A, Sivapathasundharam B |title=Shafer's textbook of oral pathology|date=2014|isbn=978-8131238004|page=351|edition=Seventh| chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=WnhtAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA351|publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences ]|access-date=11 September 2017|archive-date=17 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191217060733/https://books.google.com/books?id=WnhtAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA351|url-status=live}}</ref> Typically the rash occurs in a single, wide mark either on the left or right side of the body or face.<ref name=Pink2015/> Two to four days before the rash occurs there may be ] or local pain in the area.<ref name=Pink2015/><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last1=de Oliveira Gomes |first1=Juliana |last2=Gagliardi |first2=Anna Mz |last3=Andriolo |first3=Brenda Ng |last4=Torloni |first4=Maria Regina |last5=Andriolo |first5=Regis B. |last6=Puga |first6=Maria Eduarda Dos Santos |last7=Canteiro Cruz |first7=Eduardo |date=2 October 2023 |title=Vaccines for preventing herpes zoster in older adults |journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |volume=2023 |issue=10 |pages=CD008858 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD008858.pub5 |issn=1469-493X |pmc=10542961 |pmid=37781954}}</ref> Other common symptoms are fever, headache, and tiredness.<ref name=Pink2015/><ref name=Dwo2007/> The rash usually heals within two to four weeks,<ref name=CDC2014Sym>{{cite web|title=Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Signs & Symptoms|url=https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/symptoms.html|access-date=26 May 2015|date=1 May 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150526151203/http://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/symptoms.html|archive-date=26 May 2015| publisher=] (CDC) }}{{PD-notice}}</ref> but some people develop ongoing ] which can last for months or years, a condition called ] (PHN).<ref name=Pink2015/> In those with ] the ].<ref name=Pink2015/> If the rash involves the eye, ] may occur.<ref name=CDC2014Sym/><ref name=PMID26478818>{{cite journal | vauthors = Johnson RW, Alvarez-Pasquin MJ, Bijl M, Franco E, Gaillat J, Clara JG, Labetoulle M, Michel JP, Naldi L, Sanmarti LS, Weinke T | display-authors = 6 | title = Herpes zoster epidemiology, management, and disease and economic burden in Europe: a multidisciplinary perspective | journal = Therapeutic Advances in Vaccines | volume = 3 | issue = 4 | pages = 109–120 | date = July 2015 | pmid = 26478818 | pmc = 4591524 | doi = 10.1177/2051013615599151 }}</ref> | |||

| '''Herpes zoster''', commonly known as '''shingles''', is a disease caused by the reactivation of a ] (VZV or HHV-3) infection, also known as ].<ref name="pmid1666443">{{cite journal |author=Peterslund NA |title=Herpesvirus infection: an overview of the clinical manifestations |journal=Scand J Infect Dis Suppl |volume=80 |issue= |pages=15–20 |year=1991 |pmid=1666443 |doi= |issn= }}</ref> Once reactivated, this ] causes painful ] over the area of a ] (a skin area supplied by a single ]). | |||

| Shingles is caused by the ] (VZV) that also causes ]. In the case of chickenpox, also called varicella, the initial infection with the virus typically occurs during childhood or adolescence.<ref name=Pink2015/> Once the chickenpox has resolved, the virus can remain ] (inactive) in human ]s (] or ])<ref name="pmid35340552">{{cite journal | vauthors=Pan CX, Lee MS, Nambudiri VE | title=Global herpes zoster incidence, burden of disease, and vaccine availability: a narrative review | journal=] | volume=10 | year=2022 | doi = 10.1177/25151355221084535 | pmc=8941701 | pmid=35340552 }}</ref> for years or decades, after which it may reactivate and travel along nerve bodies to nerve endings in the skin, producing blisters.<ref name=Pink2015/><ref name=":1" /> During an outbreak of shingles, exposure to the varicella virus found in shingles blisters can cause chickenpox in someone who has not yet had chickenpox, although that person will not suffer from shingles, at least on the first infection.<ref>{{cite web|title=Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Transmission |url=https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/transmission.html|access-date=26 May 2015|date=17 September 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150506112409/http://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/transmission.html|archive-date=6 May 2015| publisher=] (CDC)}}{{PD-notice}}</ref> How the virus remains dormant in nerve cells or subsequently re-activates is not well understood.<ref name=Pink2015/><ref>{{Cite web |title=Researchers discover how chickenpox and shingles virus remains dormant |url=https://www.uclhospitals.brc.nihr.ac.uk/news/researchers-discover-how-chickenpox-and-shingles-virus-remains-dormant |access-date=25 April 2023 |website=UCLH Biomedical Research Centre |date=20 April 2018 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| After an attack of chickenpox, the varicella-zoster virus retreats to nerve cells within the ] or the ], where it lies dormant for months or even decades.<ref>{{cite journal| author=Weaver BA| title=The burden of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in the United States| journal=J Am Osteopath Assoc| date=2007| volume=107| issue=3 Suppl 1| pages=S2–7| pmid=17488884| url=http://www.jaoa.org/cgi/content/full/107/suppl_1/S2|accessdate=2007-12-10}}</ref> When ], ], or ] cause the virus to reactivate and reproduce, it travels along the path of a nerve to the skin's surface, where it causes shingles.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/healthscience/healthtopics/shingles/ |title=National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Shingles Index|accessdate=2007-05-17}}</ref><ref name="Zamula">{{cite web|url=http://www.fda.gov/FDAC/features/2001/301_pox.html|title=Shingles:An Unwelcome Encore|last=Zamula|first=Evelyn|date=2005|publisher=United States Food and Drug Administration|accessdate=2007-04-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Glaser R & Kiecolt-Glaser JK|title=Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health|journal=Nat Rev Immunol|volume=5|issue=3|pages=243–251|date=2005|doi=10.1038/nri1571|pmid=15738954}}</ref> | |||

| The disease has been recognized since ].<ref name=Pink2015>{{cite book | vauthors = Lopez A, Harrington T, Marin M | chapter = Chapter 22: Varicella | publisher = U.S. ] (CDC) | veditors = Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S | title = Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases | edition = 13th | location = Washington D.C. | year = 2015 | chapter-url = https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/varicella.html | isbn = 978-0990449119 | url = https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/index.html | access-date = 9 January 2020 | archive-date = 30 December 2016 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20161230001534/https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/index.html | url-status = live }}{{PD-notice}}</ref> Risk factors for reactivation of the dormant virus include old age, ], and having contracted chickenpox before 18 months of age.<ref name=Pink2015/> Diagnosis is typically based on the signs and symptoms presented.<ref name=NEJM2013/> ''Varicella zoster virus'' is not the same as '']'', although they both belong to the alpha subfamily of ]es.<ref name=CDC2014Over/> | |||

| Treatment is generally with ]s such as ] (Zovirax), ] (Famvir) or ] (Valtrex). These are most effective if given within 72 hours of the appearance of definitive symptoms.<ref name="Stankus">{{cite journal|last=Stankus|first=SJ|coauthors=Dlugopolski, M & Packer, D|date=2000|journal=Am Fam Physician|volume=61|issue=8|pages=2437–47|title=Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia|pmid=10794584 |url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/20000415/2437.html|accessdate=2007-04-08}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cdc.gov/nip/diseases/shingles/faqs-disease-shingles.htm|title=Shingles (Herpes Zoster)|date=2006|publisher=]|accessdate=2007-05-30}}</ref><ref name="pmid17143845">{{cite journal |author=Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, ''et al'' |title=Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster |journal=Clin. Infect. Dis. |volume=44 Suppl 1 |issue= |pages=S1–26 |year=2007 |pmid=17143845 |doi=10.1086/510206 |url=http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/510206|accessdate=2007-12-10}}</ref> | |||

| ]s reduce the risk of shingles by 50 to 90%, depending on the vaccine used.<ref name=Pink2015/><ref name=Cun2016>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cunningham AL | title = The herpes zoster subunit vaccine | journal = Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy | volume = 16 | issue = 2 | pages = 265–271 | date = 2016 | pmid = 26865048 | doi = 10.1517/14712598.2016.1134481 | name-list-style = vanc | s2cid = 46480440 }}</ref> Vaccination also decreases rates of postherpetic neuralgia, and, if shingles occurs, its severity.<ref name=Pink2015/> If shingles develops, antiviral medications such as ] can reduce the severity and duration of disease if started within 72 hours of the appearance of the rash.<ref name=NEJM2013>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cohen JI | title = Clinical practice: Herpes zoster | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 369 | issue = 3 | pages = 255–263 | date = July 2013 | pmid = 23863052 | pmc = 4789101 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMcp1302674 | name-list-style = vanc }}</ref> Evidence does not show a significant effect of antivirals or ] on rates of postherpetic neuralgia.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chen N, Li Q, Yang J, Zhou M, Zhou D, He L | title = Antiviral treatment for preventing postherpetic neuralgia | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2014 | issue = 2 | pages = CD006866 | date = February 2014 | pmid = 24500927 | pmc = 10583132 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD006866.pub3 }}</ref><ref name=":0">{{cite journal | vauthors = Jiang X, Li Y, Chen N, Zhou M, He L | title = Corticosteroids for preventing postherpetic neuralgia | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2023 | issue = 12 | pages = CD005582 | date = December 2023 | pmid = 38050854 | pmc = 10696631 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD005582.pub5 }}</ref> ], ]s, or ]s may be used to help with acute pain.<ref name=NEJM2013/> | |||

| It is estimated that about a third of people develop shingles at some point in their lives.<ref name=Pink2015/> While shingles is more common among older people, children may also get the disease.<ref name=CDC2014Over>{{cite web|title=Overview|url=https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/overview.html|access-date=26 May 2015|date=17 September 2014|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150516220957/http://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/overview.html|archive-date=16 May 2015| publisher=] (CDC)}}{{PD-notice}}</ref> According to the US ], the ] ranges from 1.2 to 3.4 per 1,000 person-years among healthy individuals to 3.9 to 11.8 per 1,000 person-years among those older than 65 years of age.<ref name=Dwo2007>{{cite journal |vauthors = Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, Gnann JW, Levin MJ, Backonja M, Betts RF, Gershon AA, Haanpaa ML, McKendrick MW, Nurmikko TJ, Oaklander AL, Oxman MN, Pavan-Langston D, Petersen KL, Rowbotham MC, Schmader KE, Stacey BR, Tyring SK, van Wijck AJ, Wallace MS, Wassilew SW, Whitley RJ | display-authors = 6 | title=Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster| journal=]| volume=44| pages=S1–26| year=2007| issue = Suppl 1 | pmid=17143845| doi=10.1086/510206| doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Nair">{{cite book | vauthors = Nair PA, Patel BC | chapter =''Herpes zoster'' | title = StatPearls | via = NCBI Bookshelf | date=2 November 2021 | pmid=28722854 | chapter-url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/ | access-date=10 June 2022 | archive-date=10 June 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220610043425/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/ | url-status=live }}</ref> About half of those living to age 85 will have at least one attack, and fewer than 5% will have more than one attack.<ref name=Pink2015/><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Schmader KE, Dworkin RH | chapter = Herpes Zoster and Postherpetic Neuralgia | veditors = Benzon HT |title=Essentials of Pain Medicine|date=2011|publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences|location=London|isbn=978-1437735932|page=358|edition=3rd| chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=9UuAWD2FTFsC&pg=PA358|access-date=11 September 2017|archive-date=17 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191217053808/https://books.google.com/books?id=9UuAWD2FTFsC&pg=PA358|url-status=live}}</ref> Although symptoms can be severe, risk of death is very low: 0.28 to 0.69 deaths per million.<ref name="pmid35340552"/> | |||

| ==Signs and symptoms== | ==Signs and symptoms== | ||

| ] | |||

| The earliest symptoms of shingles include ], ], and ].{{fact}} These may be followed by itching, burning, and hypersensitivity.<ref name="Stankus"/> The pain may be extreme in the affected nerve, where the rash will later develop, and can be characterized as stinging, tingling, aching, numbing, or throbbing, and can be pronounced with quick stabs of intensity.<ref name="pmid15307000">{{cite journal |author=Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, Sweeney EW, Dworkin RH |title=Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life |journal=Clin. Infect. Dis. |volume=39 |issue=3 |pages=342–8 |year=2004 |pmid=15307000 |doi=10.1086/421942 |url=http://www.thorne.com/altmedrev/.fulltext/11/2/102.pdf|accessdate=2007-12-12}}</ref> During this phase, herpes zoster infections are often misdiagnosed as a ], ], or other diseases with similar symptoms. Some symptomatic patients do not develop the characteristic rash (a condition known as zoster sine herpete); this may delay diagnosis and treatment.<ref name="Stankus"/><ref name="Mounsey"/> | |||

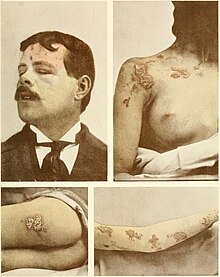

| ].]] | |||

| The earliest symptoms of shingles, which include headache, fever, and malaise, are nonspecific, and may result in an incorrect diagnosis.<ref name=Dwo2007/><ref name=pmid11458545>{{cite journal| author=Zamula E| title=Shingles: an unwelcome encore| journal=]| volume=35| issue=3| pages=21–25| date=May–June 2001| pmid=11458545| url=http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps1609/www.fda.gov/fdac/features/2001/301_pox.html| access-date=5 January 2010| url-status=live| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091103045519/http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps1609/www.fda.gov/fdac/features/2001/301_pox.html| archive-date=3 November 2009}} Revised June 2005.</ref> These symptoms are commonly followed by sensations of burning pain, itching, ] (oversensitivity), or ] ("pins and needles": tingling, pricking, or numbness).<ref name=pmid10794584>{{cite journal| vauthors=Stankus SJ, Dlugopolski M, Packer D| title=Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia| journal=]| volume=61| issue=8| pages=2437–2444, 2447–2448| year=2000| pmid=10794584| url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/20000415/2437.html| url-status=dead| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070929083747/http://www.aafp.org/afp/20000415/2437.html| archive-date=29 September 2007}}</ref> Pain can be mild to severe in the affected ], with sensations that are often described as stinging, tingling, aching, numbing or throbbing, and can be interspersed with quick stabs of agonizing pain.<ref name=pmid15307000>{{cite journal |vauthors=Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, Sweeney EW, Dworkin RH |title=Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life |journal=] |volume=39 |issue=3 |pages=342–348 |year=2004 |pmid=15307000 |doi=10.1086/421942|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Shingles in children is often painless, but people are more likely to get shingles as they age, and the disease tends to be more severe.<ref name="Hope-Simpson">{{cite journal|author=Hope-Simpson RE|title=The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis|journal=]|year=1965|volume=58|pages=9–20|pmid=14267505|pmc=1898279|issue=1|doi=10.1177/003591576505800106}}</ref> | |||

| In most cases, the initial phase is followed by development of the characteristic skin rashes of herpes zoster. The rash (and preceding pain) most commonly occurs on the torso, but can also appear on the face, eyes or other parts of the body. The rash at first is visually similar to the first appearance of ]. Unlike hives, however, shingles causes skin changes limited to a single ] (an area of skin supplied by one spinal nerve), with a stripe or belt-like pattern limited to one side of the body and not crossing the midline.<ref name="Zamula"/><ref name="Stankus"/> | |||

| In most cases, after one to two days—but sometimes as long as three weeks—the initial phase is followed by the appearance of the characteristic skin rash. The pain and rash most commonly occur on the torso but can appear on the face, eyes, or other parts of the body. At first, the rash appears similar to the first appearance of ]; however, unlike hives, shingles causes skin changes limited to a dermatome, normally resulting in a stripe or belt-like pattern that is limited to one side of the body and does not cross the midline.<ref name=pmid10794584/> <!-- Do not delete anchor, links from Bell's Palsy -->{{Anchor|Zoster sine herpete}} ''Zoster sine herpete'' ("zoster without herpes") describes a person who has all of the symptoms of shingles except this characteristic rash.<ref name=pmid10980741>{{cite journal |vauthors=Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y |title=Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy |journal=] |volume=55 |issue=5 |pages=708–710 |year=2000 |pmid=10980741 |doi=10.1212/WNL.55.5.708| s2cid = 29270135 }}</ref> | |||

| The rash evolves into small ]s filled with ] (vesicles), which are generally painful. Their development is often associated with the occurrence of anxiety and further flu-like symptoms, such as fever, tiredness, and generalized pain. The vesicles eventually become cloudy or darkened as they fill with blood, and crust over within seven to ten days. After the crusts fall off, patients are typically left with scarring and discolored skin.<ref name="Stankus"/> | |||

| Later the rash becomes ], forming small blisters filled with a ], as the fever and general malaise continue. The painful vesicles eventually become cloudy or darkened as they fill with blood, and crust over within seven to ten days; usually the crusts fall off and the skin heals, but sometimes, after severe blistering, scarring and discolored skin remain.<ref name=pmid10794584/> The blister fluid contains varicella zoster virus, which can be transmitted through contact or inhalation of fluid droplets until the lesions crust over, which may take up to four weeks.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/shingles/fact_sheet.htm|title=Shingles (herpes zoster)|date=January 2023|publisher=New York State|website=Department of Health|access-date=9 March 2023}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| Image:ShinglesDay1.JPG|Day 1. | |||

| Image:ShinglesDay2.JPG|Day 2. | |||

| Image:ShinglesDay5.JPG|Day 5. | |||

| Image:ShinglesDay6.JPG|Day 6, with characteristic purple color. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| {| style="margin:auto;" | |||

| ==Causes== | |||

| |+ '''Development of the shingles rash''' | |||

| Shingles can only arise in individuals who have been previously exposed to chickenpox (varicella-zoster). The disease arises from various events which depress the immune system, such as aging, severe ], severe illness, ] or long-term use of ]s.<ref name="Mounsey">{{cite journal|title=Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia: prevention and management|author=Mounsey AL, Matthew LG, & Slawson DC| date=2005| journal=Am Fam Physician| volume=72| issue=6| pages=1075–80| pmid=16190505| url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/20050915/1075.html}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=What does epidemiology tell us about risk factors for herpes zoster?|author=Thomas SL, Hall AJ|journal=Lancet Infect Dis.|date=2004|volume=4|issue=1|pages=26–33|pmid=14720565}}</ref> The cellular and immunological events that lead to reactivation are poorly understood.<ref name="Donahue"/> Although shingles can affect people with ] (more often in those afflicted with ]s or ]s than in cases involving solid tumors), it is not a risk factor for having an underlying cancer problem, so there is no need for cancer investigations simply because of shingles.<ref name="Healthandage">Griffith, RW. . Reviewed: June 16, 2003. Retrieved December 11, 2007.</ref> | |||

| ! Day 1 !! Day 2 !! Day 5 !! Day 6 | |||

| |- valign="top" | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| |} | |||

| == |

===Face=== | ||

| Shingles may have additional symptoms, depending on the dermatome involved. The ] is the most commonly involved nerve,<!-- , accounting for 18–22% of shingles cases--><ref name=Gupta2015>{{cite journal| vauthors = Gupta S, Sreenivasan V, Patil PB |title = Dental complications of herpes zoster: Two case reports and review of literature |journal=]|date=2015|volume=26|issue=2|pages=214–219|doi=10.4103/0970-9290.159175|pmid=26096121|doi-access=free}}</ref> of which the ophthalmic division is the most commonly involved branch.<ref name=Samaranayake2011>{{cite book|author=Samaranayake L|title=Essential Microbiology for Dentistry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xanRAQAAQBAJ&pg=PT638|edition=4th|year= 2011|publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences|isbn=978-0702046957|pages=638–642|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170908175310/https://books.google.com/books?id=xanRAQAAQBAJ&pg=PT638|archive-date=8 September 2017}}</ref> When the virus is reactivated in this nerve branch it is termed '']''. The skin of the forehead, upper eyelid and ] may be involved. Zoster ophthalmicus occurs in approximately 10% to 25% of cases. In some people, symptoms may include ], ], ], and ] ] that can sometimes cause chronic ocular inflammation, loss of vision, and debilitating pain.<ref name=pmid12449270>{{cite journal| vauthors=Shaikh S, Ta CN| title=Evaluation and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus| journal=]| year=2002| volume=66| issue=9| pages=1723–1730| pmid=12449270| url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/20021101/1723.html| url-status=live| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080514021237/http://www.aafp.org/afp/20021101/1723.html| archive-date=14 May 2008}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Most people are infected with VZV in childhood, as it causes ]. The immune system eventually eliminates the virus from most locations, but it remains dormant in the ] adjacent to the spinal cord (called the ]) or the ] in the base of the skull. | |||

| ''Shingles oticus'', also known as ], involves the ]. It is thought to result from the virus spreading from the ] to the ]. Symptoms include ] and ] (rotational dizziness).<ref name=pmid12676845/> | |||

| Usually, the ] suppresses reactivation of the virus. In the elderly, whose immune response generally tends to deteriorate, as well as in those patients whose immune system is being suppressed, this process is compromised. Viral replication commences in the nerve cells, and newly formed viruses are carried down the ]s to the area of skin served by that ganglion (a ]). Here, the virus causes local ] in the skin, with the formation of blisters.<ref name="Zamula"/><ref name="Stankus"/> | |||

| Shingles may occur in the mouth if the maxillary or mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve is affected,<ref name=Neville2008/> in which the rash may appear on the ] of the upper jaw (usually the palate, sometimes the gums of the upper teeth) or the lower jaw (tongue or gums of the lower teeth) respectively.<ref name=Glick2014/> Oral involvement may occur alone or in combination with a rash on the skin over the cutaneous distribution of the same trigeminal branch.<ref name=Neville2008/> As with shingles of the skin, the lesions tend to only involve one side, distinguishing it from other oral blistering conditions.<ref name=Glick2014/> In the mouth, shingles appears initially as 1–4 mm opaque blisters (vesicles),<ref name=Neville2008/> which break down quickly to leave ] that heal within 10–14 days.<ref name=Glick2014/> The prodromal pain (before the rash) may be confused with ].<ref name=Neville2008>{{cite book| vauthors = Chi AC, Damm DD, Neville BW, Allen CM, Bouquot J | chapter = Viral Infections |title=Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology|year=2008|publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences|isbn=978-1437721973|pages=250–253| chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=5QIEAQAAQBAJ&pg=P250 |url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170908175310/https://books.google.com/books?id=5QIEAQAAQBAJ&pg=P250|archive-date=8 September 2017}}</ref> Sometimes this leads to unnecessary dental treatment.<ref name=Glick2014>{{cite book|author=Glick M|title=Burket's oral medicine|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NNAaCAAAQBAJ&pg=PR62|edition=12th|year=2014|publisher=coco|isbn=978-1607951889|pages=62–65}}{{Dead link|date=August 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> Post-herpetic neuralgia uncommonly is associated with shingles in the mouth.<ref name=Glick2014/> Unusual complications may occur with intra-oral shingles that are not seen elsewhere. Due to the close relationship of blood vessels to nerves, the virus can spread to involve the blood vessels and compromise the blood supply, sometimes causing ] ].<ref name=Neville2008/> In rare cases, oral involvement causes complications such as ], ], ] (gum disease), pulp calcification, ], ] and tooth developmental anomalies.<ref name=Gupta2015/> | |||

| Shingles cannot be caught from another person. However, during the blister phase, direct contact with the rash can spread VZV to a person who has no immunity to the virus (either from previous chickenpox or its vaccine). The exposed person may then develop chickenpox, not shingles. The virus is not spread through ], such as sneezing or coughing. Once the rash has developed crusts, the person is no longer contagious. A person is not infectious before blisters appear or with post-herpetic neuralgia (pain after the rash is gone).<ref name="Zamula"/><ref name="Stankus"/> | |||

| ===Disseminated shingles=== | |||

| {{anchor|Disseminated}}In those with deficits in immune function, ''disseminated shingles'' may occur (wide rash).<ref name=Pink2015/> | |||

| It is defined as more than 20 ]s appearing outside either the primarily affected dermatome or dermatomes directly adjacent to it. Besides the skin, other organs, such as the ] or ], may also be affected (causing ] or ],<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Chai W, Ho MG |title=Disseminated varicella zoster virus encephalitis |journal=Lancet |volume=384 |issue=9955 |pages=1698 |date=November 2014 |pmid=24999086 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60755-8 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Grahn A, Studahl M |title = Varicella-zoster virus infections of the central nervous system – Prognosis, diagnostics and treatment |journal=]|date=September 2015|volume=71|issue=3|pages=281–293|pmid=26073188|doi=10.1016/j.jinf.2015.06.004}}</ref> respectively), making the condition potentially lethal.<ref name="Andrews">{{cite book |vauthors=Elston DM, Berger TG, James WD |title=Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology |publisher=Saunders Elsevier |year=2006 |isbn=978-0721629216 }}</ref>{{rp|380}} | |||

| ==Pathophysiology== | |||

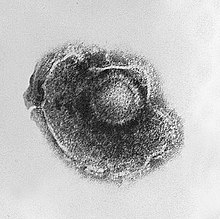

| ] of ]. Approximately 150,000× magnification. The virus diameter is 150–200 nm.<ref>{{cite web |publisher=] |title=Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Varicella-zoster virus |date=30 April 2012 |access-date=3 June 2022 |url=https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/laboratory-biosafety-biosecurity/pathogen-safety-data-sheets-risk-assessment/varicella-zoster-virus.html |archive-date=22 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200322012121/https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/laboratory-biosafety-biosecurity/pathogen-safety-data-sheets-risk-assessment/varicella-zoster-virus.html |url-status=live }}</ref>]] | |||

| ], break open (3), crust over (4), and finally disappear. ] can sometimes occur due to nerve damage (5).|thumb]] | |||

| The causative agent for shingles is the ] (VZV)—a double-stranded ] related to the ]. Most individuals are infected with this virus as children which causes an episode of ]. The immune system eventually eliminates the virus from most locations, but it remains dormant (or ]) in the ] adjacent to the spinal cord (called the ]) or the ] in the base of the skull.<ref name=pmid17945155>{{cite journal|vauthors=Steiner I, Kennedy PG, Pachner AR | title=The neurotropic herpes viruses: herpes simplex and varicella-zoster| journal=]| volume=6| issue=11| pages=1015–1028| year=2007| pmid=17945155| doi=10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70267-3 | s2cid=6691444}}</ref> | |||

| Shingles occurs only in people who have been previously infected with VZV; although it can occur at any age, approximately half of the cases in the United States occur in those aged 50 years or older.<ref name=pmid18021864>{{cite journal| vauthors=Weinberg JM| title=Herpes zoster: epidemiology, natural history, and common complications| journal=]|volume=57| issue=6 Suppl| pages=S130–S135| year=2007| pmid=18021864| doi=10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.046}}</ref> Shingles can recur.<ref name="MMWR mm6703a5"/> In contrast to the frequent recurrence of ] symptoms, repeated attacks of shingles are unusual.<ref name=Kennedy2015>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, Cohrs RJ |title=A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation |journal=The Journal of General Virology |volume=96 |issue=Pt 7 |pages=1581–1602 |date=2015 |pmid=25794504 |pmc=4635449 |doi=10.1099/vir.0.000128 |url=}}</ref> It is extremely rare for a person to have more than three recurrences.<ref name=pmid17945155/> | |||

| The disease results from virus particles in a single sensory ganglion switching from their latent phase to their active phase.<ref name="pmid14583142">{{cite journal|vauthors=Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R | title=Clinical and molecular pathogenesis of varicella virus infection| journal=Viral Immunology| volume=16| issue=3| pages=243–258| year=2003| pmid=14583142| doi=10.1089/088282403322396073}}</ref> Due to difficulties in studying VZV reactivation directly in humans (leading to reliance on small-]s), its latency is less well understood than that of the herpes simplex virus.<ref name=Kennedy2015/> Virus-specific proteins continue to be made by the infected cells during the latent period, so true latency, as opposed to ], low-level, active ], has not been proven to occur in VZV infections.<ref name=pmid12211045>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kennedy PG |title=Varicella-zoster virus latency in human ganglia |journal=Reviews in Medical Virology |volume=12 |issue=5 |pages=327–334 |year=2002 |pmid=12211045 |doi=10.1002/rmv.362|s2cid=34582060 }}</ref><ref name=pmid12491156>{{cite journal| vauthors=Kennedy PG| title=Key issues in varicella-zoster virus latency| journal=]| volume=8 | issue = Suppl 2 | pages=80–84| year=2002| pmid=12491156| doi=10.1080/13550280290101058 | citeseerx=10.1.1.415.2755}}</ref> Although VZV has been detected in autopsies of nervous tissue,<ref name="pmid12707850">{{cite journal| vauthors=Mitchell BM, Bloom DC, Cohrs RJ, Gilden DH, Kennedy PG | title=Herpes simplex virus-1 and varicella-zoster virus latency in ganglia| journal=]| volume=9| issue=2| pages=194–204| year=2003| pmid=12707850| doi=10.1080/13550280390194000| s2cid = 5964582 | url=http://www.jneurovirol.com/o_pdf/9(2)/194-204.pdf| url-status=live| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080517075513/http://www.jneurovirol.com/o_pdf/9(2)/194-204.pdf| archive-date=17 May 2008}}</ref> there are no methods to find dormant virus in the ganglia of living people. | |||

| Unless the ] is compromised, it suppresses reactivation of the virus and prevents shingles outbreaks. Why this suppression sometimes fails is poorly understood,<ref name=pmid7618983>{{cite journal|vauthors=Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, Platt R | title=The incidence of herpes zoster| journal=]| volume=155| issue=15| pages=1605–1609| year=1995| pmid=7618983| doi=10.1001/archinte.155.15.1605}}</ref> but shingles is more likely to occur in people whose immune systems are impaired due to aging, ], ], or other factors.<ref name=pmid14720565>{{cite journal|vauthors=Thomas SL, Hall AJ | title=What does epidemiology tell us about risk factors for herpes zoster?| journal=]| volume=4| issue=1| pages=26–33| year=2004| doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00857-0| pmid=14720565}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Shingles|url=https://beta.nhs.uk/conditions/shingles/|website=NHS.UK|access-date=25 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170926042439/https://beta.nhs.uk/conditions/shingles/|archive-date=26 September 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> Upon reactivation, the virus replicates in neuronal cell bodies, and ]s are shed from the cells and carried down the ]s to the area of skin innervated by that ganglion. In the skin, the virus causes local ] and blistering. The short- and long-term pain caused by shingles outbreaks originates from inflammation of affected nerves due to the widespread growth of the virus in those areas.<ref name=pmid17631237>{{cite journal |author=Schmader K |title=Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults |journal=Clinics in Geriatric Medicine |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=615–632, vii–viii |year=2007 |pmid=17631237 |pmc=4859150 |doi=10.1016/j.cger.2007.03.003 }}</ref> | |||

| As with chickenpox and other forms of alpha-herpesvirus infection, direct contact with an active rash can spread the virus to a person who lacks immunity to it. This newly infected individual may then develop chickenpox, but will not immediately develop shingles.<ref name=pmid10794584/> | |||

| The complete sequence of the viral ] was published in 1986.<ref name="pmid3018124">{{cite journal| vauthors=Davison, AJ, Scott, JE | title=The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus| journal=]| volume=67| issue=9| pages=1759–1816| year=1986| pmid=3018124| doi=10.1099/0022-1317-67-9-1759| doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ==Diagnosis== | ==Diagnosis== | ||

| ] | |||

| The diagnosis is made on visual examination; very few other diseases mimic herpes zoster, especially in the localization of the rash, which is otherwise quite similar in appearance and initial effect to that of ] or ] (although it may not be accompanied by the intense itching so characteristic of those rashes). ] may be performed in doubtful cases. These may be necessary because, depending on the affected sensory nerve, the pain that is experienced before the onset of the rash may be misdiagnosed as ], ], ], ], or a ]. | |||

| If the rash has appeared, identifying this disease (making a ]) requires only a visual examination, since very few diseases produce a rash in a ] (sometimes called by doctors on TV "a dermatonal map").{{Citation needed|date=July 2024|reason=This statement is very vague and could benefit from specific examples.}} However, ] (HSV) can occasionally produce a rash in such a pattern (zosteriform herpes simplex).<ref name=Koh>{{cite journal| vauthors = Koh MJ, Seah PP, Teo RY |title=Zosteriform herpes simplex|journal=]|date=Feb 2008|volume=49|pages=e59–60|pmid=18301829|url=http://smj.sma.org.sg/4902/4902cr9.pdf|issue=2|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140602213312/http://smj.sma.org.sg/4902/4902cr9.pdf|archive-date=2 June 2014}}</ref><ref name=Kalman>{{cite journal| vauthors = Kalman CM, Laskin OL |title=Herpes zoster and zosteriform herpes simplex virus infections in immunocompetent adults|journal=]|date=Nov 1986|volume=81 |pages=775–778|pmid=3022586|issue=5|doi=10.1016/0002-9343(86)90343-8}}</ref> | |||

| When the rash is absent (early or late in the disease, or in the case of {{lang|la|zoster sine herpete}}), shingles can be difficult to diagnose.<ref name=pmid15334402>{{cite journal|vauthors=Chan J, Bergstrom RT, Lanza DC, Oas JG | title=Lateral sinus thrombosis associated with zoster sine herpete| journal=Am. J. Otolaryngol.| volume=25| issue=5| pages=357–360| year=2004| pmid=15334402| doi=10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.007}}</ref> Apart from the rash, most symptoms can occur also in other conditions. | |||

| Fluid from a blister may be taken and analyzed in a ] where it is tested by ] (PCR) for the presence of VZV ] or examined by ] for Herpes virus particles.<ref name="pmid9515761">{{cite journal | |||

| |author=Beards G, Graham C, Pillay D| title=Investigation of vesicular rashes for HSV and VZV by PCR| journal=J. Med. Virol| volume=54| issue=3| pages=155–7| year=1998| pmid=9515761}}</ref> A physician can also take a ] of ] from a fresh lesion, or perform a microscopic examination of the blister base called a ] which although inferior to PCR, is a reliable diagnostic method.<ref name="pmid17988338">{{cite journal|author=Ozcan A, Senol M, Saglam H, ''et al''|title=Comparison of the Tzanck test and polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of cutaneous herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections| journal=Int. J. Dermatol.| volume=46| issue=11| pages=1177–9| year=2007| pmid=17988338| doi=10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03337.x}}</ref> In a complete blood count there may be an elevated number of ], which is an indirect sign of infection. The presence of ] antibody to the virus in the blood would also give indication of the virus’ reactivation.<ref name="Stankus"/> | |||

| Laboratory tests are available to diagnose shingles. The most popular test detects VZV-specific ] ] in blood; this appears only during chickenpox or shingles and not while the virus is dormant.<ref name=pmid8809466>{{cite journal| author=Arvin AM| title=Varicella-zoster virus| journal=]| volume=9| issue=3| pages=361–381| year=1996| pmid=8809466| url= http://cmr.asm.org/cgi/reprint/9/3/361.pdf| pmc=172899| url-status=live| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080625213222/http://cmr.asm.org/cgi/reprint/9/3/361.pdf| archive-date=25 June 2008| doi=10.1128/CMR.9.3.361}}</ref> In larger laboratories, ] collected from a blister is tested by ] (PCR) for VZV DNA, or examined with an electron microscope for virus particles.<ref name="pmid9515761">{{cite journal|vauthors=Beards G, Graham C, Pillay D | title=Investigation of vesicular rashes for HSV and VZV by PCR| journal=]| volume=54| issue=3| pages=155–157| year=1998| pmid=9515761 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199803)54:3<155::AID-JMV1>3.0.CO;2-4| s2cid=24215093}}</ref> Molecular biology tests based on ''in vitro'' nucleic acid amplification (PCR tests) are currently considered the most reliable. ] test has high ], but is susceptible to contamination leading to ]. The latest ] tests are rapid, easy to perform, and as sensitive as nested PCR, and have a lower risk of contamination. They also have more sensitivity than ]s.<ref name=DePaschaleClerici2016>{{cite journal| vauthors=De Paschale M, Clerici P| title=Microbiology laboratory and the management of mother-child varicella-zoster virus infection. | journal=World J Virol | year= 2016 | volume= 5 | issue= 3 | pages= 97–124 | pmid=27563537 | doi=10.5501/wjv.v5.i3.97 | pmc=4981827 | type= Review | doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| VZV ], a rare and serious complication of shingles in ] people, can be rapidly confirmed by PCR testing of cerebro-spinal fluid.<ref name="pmid15319090">{{cite journal |author=Boivin G |title=Diagnosis of herpesvirus infections of the central nervous system |journal=Herpes |volume=11 Suppl 2 |issue= |pages=48A–56A |year=2004 |pmid=15319090}}</ref> | |||

| === Differential diagnosis === | |||

| ==Treatment== | |||

| Shingles can be confused with ], ] and ], and skin reactions caused by ], ], certain drugs and insect bites.<ref name=SampathkumarDrage2009>{{cite journal| vauthors=Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP| title=Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia | journal=Mayo Clin Proc | year= 2009 | volume= 84 | issue= 3 | pages= 274–280 | pmid=19252116 | doi=10.4065/84.3.274 | pmc=2664599 | type= Review }}</ref> | |||

| There is no cure available for herpes zoster, nor a treatment to effectively eliminate the virus from the body. However, there are some treatments that can mitigate the length of the disease and alleviate certain side effects. | |||

| == Prevention == | |||

| ===Antiviral drugs=== | |||

| {{Main|Zoster vaccine}} | |||

| The ]s ], ] and ] inhibit replication of viral DNA. They are used both as ] (for example, in patients with ]) and as therapy during the ]. Oral aciclovir is most effective in moderating the progress of the symptoms, and in preventing post-herpetic neuralgia, if started within 24 to 72 hours of the onset of symptoms. ] patients may respond best to intravenous aciclovir. In patients who are at high risk for recurrences, an oral dose of aciclovir, taken five times daily, is usually effective.<ref name="Johnson"/> | |||

| Shingles risk can be reduced in children by the ] if the vaccine is administered before the individual gets chickenpox.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Weinmann S, Naleway AL, Koppolu P, Baxter R, Belongia EA, Hambidge SJ, Irving SA, Jackson ML, Klein NP, Lewin B, Liles E, Marin M, Smith N, Weintraub E, Chun C |display-authors = 6 |title=Incidence of Herpes Zoster Among Children: 2003–2014 |journal=Pediatrics |volume=144 |issue=1 |pages= e20182917|date=July 2019 |pmid=31182552 |doi=10.1542/peds.2018-2917 |pmc = 7748320 |s2cid = 184486904|doi-access=free }}*{{lay source |template=cite web|date=11 June 2019|url=https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/two-for-one-chickenpox-vaccine-lowers-shingles-risk-in-children |title=Two-for-One: Chickenpox Vaccine Lowers Shingles Risk in Children|website = Scientific American}}</ref> If primary infection has already occurred, there are ]s that reduce the risk of developing shingles or developing severe shingles if the disease occurs.<ref name=Pink2015/><ref name=Cun2016/> They include a ] vaccine, Zostavax, and an ] ] vaccine, Shingrix.<ref name="MMWR mm6703a5">{{cite journal |vauthors=Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, Lee GM, Moore K, Belongia EA, Harpaz R |display-authors=6 |title=Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Herpes Zoster Vaccines |journal=MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. |volume=67 |issue=3 |pages=103–108 |date=January 2018 |pmid=29370152 |pmc=5812314 |doi=10.15585/mmwr.mm6703a5 |url=https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/pdfs/mm6703a5-H.pdf |access-date=9 January 2020 |archive-date=29 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210829055010/https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/pdfs/mm6703a5-H.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="MMWR_57(05)">{{cite journal| vauthors = Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF| title = Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)| journal = ]| volume = 57| issue = RR–5| pages = 1–30; quiz CE2–4| date = 6 June 2008| pmid = 18528318| url = https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5705a1.htm| access-date = 4 January 2010| url-status=live| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20091117154208/http://www.cdc.gov/mmWR/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5705a1.htm| archive-date = 17 November 2009}}{{PD-notice}}</ref><ref name="pmid27626517"/> | |||

| The ] ] has also been reported that to inhibit the replication of herpes zoster.{{fact}} | |||

| A review by ] concluded that Zostavax was useful for preventing shingles for at least three years.<ref name=":1" /> This equates to about 50% ]. The vaccine reduced rates of persistent, severe pain after shingles by 66% in people who contracted shingles despite vaccination.<ref name=shapiro>{{cite journal |vauthors=Shapiro M, Kvern B, Watson P, Guenther L, McElhaney J, McGeer A |title=Update on herpes zoster vaccination: a family practitioner's guide |journal=] |volume=57 |issue=10 |pages=1127–1131 |date=October 2011 |pmid=21998225 |pmc=3192074 }}</ref> Vaccine efficacy was maintained through four years of follow-up.<ref name=shapiro/> It has been recommended that people with primary or acquired immunodeficiency should not receive the live vaccine.<ref name=shapiro/> | |||

| ===Other drugs=== | |||

| ], a common component of over-the-counter ] medication, has been shown to lessen the severity of herpes zoster outbreaks in several different instances.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Kapinska-Mrowiecka M, &Toruwski G | title=Efficacy of cimetidine in treatment of herpes zoster in the first 5 days from the moment of disease manifestation | journal=Pol Tyg Lek | year=1996 | pages=338–9 | volume=51 | issue=23–26 | pmid=9273526}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Hayne ST, & Mercer JB|title=Herpes zoster: treatment with cimetidine|journal=Can Med Assoc J|year=1983|pages=1284–5| volume=129| issue=12| pmid=6652595}} {{PMC|1875716}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Notmann J, Arieli J, Hart J, Levinsky H, Halbrecht I, & Sendovsky U | title=In vitro cell-mediated immune reactions in herpes zoster patients treated with cimetidine | journal=Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. |year=1994|pages=51–8|volume=12|issue=1| pmid=7872992}}</ref> This usage is considered an ] of the drug. In addition, cimetidine and ] have been shown to reduce the renal clearance of aciclovir.<ref>{{cite journal|author=De Bony F, Tod M, Bidault R, On NT, Posner J, & Rolan P| title=Multiple interactions of cimetidine and probenecid with valaciclovir and its metabolite aciclovir |journal=Antimicrob Agents Chemother|year=2002|pages=458–63|volume=46 |issue=2|pmid=11796358|url=http://aac.asm.org/cgi/content/full/46/2/458}}</ref> The study showed these compounds reduce the rate, but not the extent, at which valaciclovir is converted into aciclovir. Renal clearance of aciclovir was reduced by approximately 24% and 33% respectively. In addition, respective increases in the peak plasma concentration of aciclovir of 8% and 22% were observed. The authors concluded that these effects were "not expected to have clinical consequences regarding the safety of valaciclovir". Due to the tendency of aciclovir to precipitate in renal tubules, combining these drugs should only occur under the supervision of a physician. | |||

| Two doses of Shingrix are recommended, which provide about 90% protection at 3.5 years.<ref name="MMWR mm6703a5"/><ref name="pmid27626517">{{cite journal |vauthors=Cunningham AL, Lal H, Kovac M, Chlibek R, Hwang SJ, Díez-Domingo J, Godeaux O, Levin MJ, McElhaney JE, Puig-Barberà J, Vanden Abeele C, Vesikari T, Watanabe D, Zahaf T, Ahonen A, Athan E, Barba-Gomez JF, Campora L, de Looze F, Downey HJ, Ghesquiere W, Gorfinkel I, Korhonen T, Leung E, McNeil SA, Oostvogels L, Rombo L, Smetana J, Weckx L, Yeo W, Heineman TC |display-authors = 6 |title=Efficacy of the Herpes Zoster Subunit Vaccine in Adults 70 Years of Age or Older |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=375 |issue=11 |pages=1019–1032 |date=September 2016 |pmid=27626517 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa1603800 |doi-access=free |hdl=10536/DRO/DU:30086550 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> As of 2016, it had been studied only in people with an intact immune system.<ref name=Cun2016/> It appears to also be effective in the very old.<ref name=Cun2016/> | |||

| ==Prognosis== | |||

| The rash and pain usually subside within three to five weeks. Many patients develop a painful condition called ], which is often difficult to manage. Herpes zoster can reactivate subclinically in some patients, with pain in a dermatomal distribution without an accompanying ]. This condition is known as ''zoster sine herpete,'' and may be more complicated, affecting multiple levels of the ] and causing multiple ] ], ], ], or ]. Sometimes serious effects including partial ] (usually temporary), ear damage, or ] may occur.<ref name="Johnson">{{cite journal|journal=BMJ|date=2003|volume=326|issue=7392|pages=748|doi=10.1136/bmj.326.7392.748|author=Johnson, RW & Dworkin, RH|title=Clinical review: Treatment of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia|pmid=12676845|url=http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/326/7392/748}}</ref> | |||

| In the UK, shingles vaccination is offered by the ] (NHS) to all people in their 70s. {{As of|2021}} Zostavax is the usual vaccine, but Shingrix vaccine is recommended if Zostavax is unsuitable, for example for those with immune system issues. Vaccination is not available to people over 80 as "it seems to be less effective in this age group".<ref>{{Cite web |title=Shingles vaccine overview |author= |website=NHS (UK) |date=31 August 2021 |url=https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/shingles-vaccination/ |access-date=9 October 2021 |archive-date=2 June 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140602024601/https://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/vaccinations/Pages/shingles-vaccination.aspx |url-status=live }} Overview to be reviewed 31 August 2024.</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/697963/Shingles_vaccination_prgramme_letter_April2018.pdf | title=The shingles immunisation programme: evaluation of the programme and implementation in 2018 | publisher=] (PHE) | date=9 April 2018 | access-date=9 January 2020 | archive-date=9 January 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200109161256/https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/697963/Shingles_vaccination_prgramme_letter_April2018.pdf | url-status=live }}</ref> By August 2017, just under half of eligible 70–78 year olds had been vaccinated.<ref>{{cite web | title=Herpes zoster (shingles) immunisation programme 2016 to 2017: evaluation report | website=GOV.UK | date=15 December 2017 | url=https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/herpes-zoster-shingles-immunisation-programme-2016-to-2017-evaluation-report | access-date=9 January 2020 | archive-date=9 January 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200109161228/https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/herpes-zoster-shingles-immunisation-programme-2016-to-2017-evaluation-report | url-status=live }}</ref> About 3% of those eligible by age have conditions that suppress their immune system, and should not receive Zostavax.<ref name=HSJ/> There had been 1,104 adverse reaction reports by April 2018.<ref name=HSJ>{{cite news |title=NHS England warning as vaccine programme extended |url=https://www.hsj.co.uk/policy-and-regulation/nhs-england-warning-as-vaccine-programme-extended/7022175.article |url-access=registration |author=Shaun Linter |work=Health Service Journal |date=18 April 2018 |access-date=10 June 2018 |archive-date=15 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191115234845/https://www.hsj.co.uk/policy-and-regulation/nhs-england-warning-as-vaccine-programme-extended/7022175.article |url-status=live }}</ref> In the US, it is recommended that healthy adults 50 years and older receive two doses of Shingrix, two to six months apart.<ref name="MMWR mm6703a5"/><ref name=CDC2019Sym>{{cite web|title=Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Vaccination|url=https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/vaccination.html|access-date=18 January 2019|date=25 October 2018|publisher=] (CDC)|archive-date=16 January 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200116090840/https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/vaccination.html|url-status=live}}{{PD-notice}}</ref> | |||

| Shingles on the upper half of the face may result in ] damage and require urgent ] assessment. Approximately 25% of Herpes zoster cases result in "Herpes zoster ]" (of the eye), which occurs when the varicella-zoster virus is reactivated in the ] of the ]. Patients with this condition exhibit a vesicular rash around the ] distributed according to the affected dermatome. A minority of patients may also develop ], ], ], and ] ]. This can sometimes result in chronic ocular inflammation, loss of vision, and debilitating pain.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Shaikh S, Ta CN|title=Evaluation and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus|journal=Am Fam Physician|date=2002|volume=66|issue=9|pages=1723–1730|pmid=12449270|url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/20021101/1723.html}}</ref> | |||

| ==Treatment== | |||

| Reactivation of the Varicella-zoster virus along the ] (which innervates the hearing and balance organs in the inner ear) is responsible for "Herpes zoster oticus", also known as ]. The virus is thought to spread from the neighbouring ]. The symptoms of herpes zoster oticus include hearing loss and ] (rotational dizziness).<ref name="Johnson"/> | |||

| The aims of treatment are to limit the severity and duration of pain, shorten the duration of a shingles episode, and reduce complications. Symptomatic treatment is often needed for the complication of postherpetic neuralgia.<ref name=pmid18021865>{{cite journal |journal= ] |year=2007 |volume=57 |issue= 6 Suppl |pages=S136–S142 |title= Management of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia |author= Tyring SK |doi=10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.016 |pmid=18021865}}</ref> | |||

| However, a study on untreated shingles shows that, once the rash has cleared, ] is very rare in people under 50 and wears off in time; in older people, the pain wore off more slowly, but even in people over 70, 85% were free from pain a year after their shingles outbreak.<ref name=pmid11009518>{{cite journal | vauthors = Helgason S, Petursson G, Gudmundsson S, Sigurdsson JA | title= Prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia after a single episode of herpes zoster: prospective study with long term follow up | journal= ] | volume= 321 | year= 2000 | pmid= 11009518 | doi= 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.794 | issue= 7264 | pages= 794–796 | pmc= 27491 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Analgesics=== | |||

| In the ], approximately 10,000 individuals are hospitalized as a result of Herpes zoster and approximately 100 deaths occur as a result of complications of the disease. Herpes zoster occurs mostly in individuals with ] (particularly those with ] infection or those who are receiving ]), in the elderly or in early infancy.<ref name="Donahue"/><ref name="pmid17143845"/> During pregnancy, primary infection with VZV (chickenpox) but not the local reactivation (shingles) may cause problems in newborns<ref name="Paryani">{{cite journal |author=Paryani SG, Arvin AM |title=Intrauterine infection with varicella-zoster virus after maternal varicella |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=314 |issue=24 |pages=1542–6 |year=1986 |pmid=3012334 |doi=}}</ref><ref name="Enders">{{cite journal |author=Enders G, Miller E, Cradock-Watson J, Bolley I, Ridehalgh M |title=Consequences of varicella and herpes zoster in pregnancy: prospective study of 1739 cases |journal=Lancet |volume=343 |issue=8912 |pages=1548–51 |year=1994 |pmid=7802767 |doi=}}</ref>. | |||

| People with mild to moderate pain can be treated with ] ]. Topical lotions containing ] can be used on the rash or blisters and may be soothing. Occasionally, severe pain may require an opioid medication, such as ]. Once the lesions have crusted over, ] cream (Zostrix) can be used. Topical ] and nerve blocks may also reduce pain.<ref name=pmid15061819>{{cite journal| author=Baron R| title=Post-herpetic neuralgia case study: optimizing pain control| journal=] | volume=11| pages=3–11| year=2004| issue=Suppl 1| pmid=15061819| doi=10.1111/j.1471-0552.2004.00794.x| s2cid=24555396}}</ref> Administering ] along with antivirals may offer relief of postherpetic neuralgia.<ref name=pmid18021865/> | |||

| == |

===Antivirals=== | ||

| ] may reduce the severity and duration of shingles;<ref name=Bad2013>{{cite journal| vauthors = Bader MS |title = Herpes zoster: diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive approaches |journal=]|date=Sep 2013|volume=125|issue=5|pages=78–91|pmid=24113666|doi=10.3810/pgm.2013.09.2703 |s2cid = 5296437 }}</ref> however, they do not prevent ].<ref name=Han2014>{{cite journal |vauthors=Chen N, Li Q, Yang J, Zhou M, Zhou D, He |title=Antiviral treatment for preventing postherpetic neuralgia |journal=] |volume= 2014|issue=2 |pages=CD006866 |year=2014 |pmid=24500927 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006866.pub3 | veditors = He L |pmc=10583132 }}</ref> Of these drugs, ] has been the standard treatment, but the newer drugs ] and ] demonstrate similar or superior efficacy and good safety and tolerability.<ref name=pmid18021865/> The drugs are used both for ] (for example in people with ]) and as therapy during the ]. Complications in ] individuals with shingles may be reduced with ] aciclovir. In people who are at a high risk for repeated attacks of shingles, five daily oral doses of aciclovir are usually effective.<ref name=pmid12676845>{{cite journal| journal=]| year=2003| volume=326| issue=7392| pages=748–750| doi=10.1136/bmj.326.7392.748| vauthors=Johnson RW, Dworkin RH| title=Clinical review: Treatment of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia| pmid=12676845| pmc=1125653}}</ref> | |||

| ] is a ] developed by ] which has proven successful in preventing half the cases of herpes zoster in a study of 38,000 people who received the vaccine.<ref name="Oxman"/> The vaccine also reduced by two-thirds the number of cases of postherpetic neuralgia.<ref name="Oxman"/> However, prior to the vaccine, it has long been known that adults received natural immune boosting from contact with children infected with ]. This helped to suppress the reactivation of herpes zoster.<ref>{{cite journal | author=Brisson M, Gay N, Edmunds W, Andrews N | title=Exposure to varicella boosts immunity to herpes-zoster: implications for mass vaccination against chickenpox | journal=Vaccine | volume=20 | issue=19–20 | pages=2500–7 | year=2002 | pmid=12057605}}</ref> In Massachusetts, herpes zoster incidence increased 90%, from 2.77 per 1000 to 5.25 per 100 in the period of increasing varicella vaccination 1999–2003.<ref>{{cite journal | last=Yih|first=WK |coauthors =Brooks DR, Lett SM, Jumaan AO, Zhang Z, Clements KM, ''et al''| title=The incidence of varicella and herpes zoster in Massachusetts as measured by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) during a period of increasing varicella vaccination coverage, 1998–2003 | journal=BMC Public Health | volume=5| issue=1 | year=2005 | pages=68 | pmid=15960856 | url=http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/5/68}}</ref> The effectiveness of the varicella vaccine itself is dependent on this exogenous (outside) boosting mechanism. Thus, as natural cases of varicella decline, so has the effectiveness of the vaccine.<ref>{{cite journal | first=GS|last=Goldman| title=Universal varicella vaccination: efficacy trends and effect on herpes zoster | journal=Int J Toxicol | volume=24| issue=4 | year=2005 | pages=205–13 | pmid=16126614}}</ref> | |||

| ===Steroids=== | |||

| The intake of micronutrients, including antioxidant vitamins, ], ], ] and ] group, as well as fresh fruit, may reduce the risk of developing shingles. In one study, patients who consumed less than one serving of fruit a day had three times the risk as those who consumed over three servings per day. For those aged 60 or more, micronutrient and vegetable intake had a similar lowering of risk.<ref name="pmid16330478">{{cite journal |author=Thomas SL, Wheeler JG, Hall AJ |title=Micronutrient intake and the risk of herpes zoster: a case-control study |journal=Int J Epidemiol |volume=35 |issue=2 |pages=307–14 |year=2006 |pmid=16330478 |doi=10.1093/ije/dyi270|url=http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/35/2/307}}</ref> A recent study evaluating the effects of ] and health education on healthy adults, who, after 16 weeks of the intervention, were vaccinated with a live attenuated Oka/Merck varicella-zoster virus vaccine (VARIVAX) concluded that Tai Chi may augment some laboratory parameters of immunity against the varicella zoster virus.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Irwin|first=MR|coauthors=Olmstead, R & Oxman, MN|title=Augmenting immune responses to varicella zoster virus in older adults: a randomized, controlled trial of Tai Chi|date=2007|journal=J Am Geriatr Soc|volume=55|issue=4|pages=511–7| url=http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01109.x | doi=10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01109.x | pmid=17397428}}</ref> | |||

| ] do not appear to decrease the risk of ].<ref name=":0" /> Side effects however appear to be minimal. Their use in ] had not been properly studied as of 2008.<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Uscategui T, Doree C, Chamberlain IJ, Burton MJ |title=Corticosteroids as adjuvant to antiviral treatment in Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus with facial palsy) in adults|journal=]|date=16 July 2008|issue=3|pages=CD006852|pmid=18646170|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006852.pub2}}</ref> | |||

| ===Zoster ophthalmicus=== | |||

| ], from top: ] ], scabs, blister, eyelid swelling]] | |||

| Treatment for ] is similar to standard treatment for shingles at other sites.{{medcn|date=May 2023}} A trial comparing aciclovir with its ], valaciclovir, demonstrated similar efficacies in treating this form of the disease.<ref name="pmid10919899">{{cite journal| vauthors=Colin J, Prisant O, Cochener B, Lescale O, Rolland B, Hoang-Xuan T | title=Comparison of the Efficacy and Safety of Valaciclovir and Acyclovir for the Treatment of Herpes zoster Ophthalmicus|journal=] | volume=107| issue = 8| pages=1507–1511| year=2000| pmid=10919899| doi=10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00222-0}}</ref> | |||

| ==Prognosis == | |||

| The rash and pain usually subside within three to five weeks, but about one in five people develop a painful condition called ], which is often difficult to manage. In some people, shingles can reactivate presenting as ''zoster sine herpete'': pain radiating along the path of a single spinal nerve (a ''dermatomal distribution''), but without an accompanying ]. This condition may involve complications that affect several levels of the ] and cause many ] ], ], ], or ]. Other serious effects that may occur in some cases include partial ] (usually temporary), ear damage, or ].<ref name=pmid12676845/> Although initial infections with VZV during pregnancy, causing chickenpox, may lead to infection of the fetus and complications in the newborn, chronic infection or reactivation in shingles are not associated with fetal infection.<ref name=pmid3012334>{{cite journal |vauthors=Paryani SG, Arvin AM |title=Intrauterine infection with varicella-zoster virus after maternal varicella |journal=] |volume=314 |issue=24 |pages=1542–1546 |year=1986 |pmid=3012334 |doi=10.1056/NEJM198606123142403 }}</ref><ref name=Enders>{{cite journal |vauthors=Enders G, Miller E, Cradock-Watson J, Bolley I, Ridehalgh M |title=Consequences of varicella and herpes zoster in pregnancy: prospective study of 1739 cases |journal=] |volume=343 |issue=8912 |pages=1548–1551 |year=1994 |pmid=7802767 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92943-2 | s2cid = 476280 }}</ref> | |||

| There is a slightly increased risk of developing ] after a shingles episode. However, the mechanism is unclear and mortality from cancer did not appear to increase as a direct result of the presence of the virus.<ref name=pmid15328522>{{cite journal |vauthors=Sørensen HT, Olsen JH, Jepsen P, Johnsen SP, Schønheyder HC, Mellemkjaer |title=The risk and prognosis of cancer after hospitalisation for herpes zoster: a population-based follow-up study |journal=] |volume=91 |issue=7 |pages=1275–1279 |year=2004 |pmid=15328522 |doi=10.1038/sj.bjc.6602120 |pmc=2409892}}</ref> Instead, the increased risk may result from the immune suppression that allows the reactivation of the virus.<ref name=pmid6979711>{{cite journal |doi=10.1056/NEJM198208123070701 |vauthors=Ragozzino MW, Melton LJ, Kurland LT, Chu CP, Perry HO |title=Risk of cancer after herpes zoster: a population-based study |journal=] |volume=307 |issue=7 |pages=393–397 |year=1982 |pmid=6979711}}</ref> | |||

| Although shingles typically resolves within 3–5 weeks, certain complications may arise: | |||

| * Secondary bacterial infection.<ref name=PMID26478818/> | |||

| * Motor involvement,<ref name=PMID26478818/> including weakness especially in "motor herpes zoster".<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/s00415-009-5149-8|pmid=19434442|title=Pure motor Herpes Zoster induced brachial plexopathy.|journal=Journal of Neurology|volume=256|issue=8|pages=1343–1345|year=2009| vauthors = Ismail A, Rao DG, Sharrack B|s2cid=26443976}}</ref> | |||

| * Eye involvement: ] involvement (as seen in herpes ophthalmicus) should be treated early and aggressively as it may lead to blindness. Involvement of the tip of the nose in the zoster rash is a strong predictor of herpes ophthalmicus.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/eye-disorders/corneal-disorders/herpes-zoster-ophthalmicus|title=Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus|work=Merck Manual|date=September 2014|access-date=14 August 2016|author=Roat MI|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160812031812/http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/eye-disorders/corneal-disorders/herpes-zoster-ophthalmicus|archive-date=12 August 2016}}</ref> | |||

| * ], a condition of chronic pain following shingles. | |||

| ==Epidemiology== | ==Epidemiology== | ||

| {{See also|Chickenpox#Epidemiology|l1=Chickenpox epidemiology}} | |||

| Before implementation of the universal varicella ] program in the U.S., incidence of shingles increased with advancing age in association with a progressive decline in immunity to varicella-zoster virus.<ref name="Oxman">{{cite journal | first=MN|last=Oxman|coauthors=Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD, ''et al'' | title=A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults | journal=] | volume=253| issue=22 | year=2005 | pages=2271–84 | pmid=15930418 | url=http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/352/22/2271}}</ref> Shingles incidence is highest in persons who are over age 55, as well as in ] patients regardless of age group.<ref name="Donahue">{{cite journal|author=Donahue, JG, Choo, PW, Manson, JE & Platt, R|date=1995|title=The incidence of herpes zoster|journal=Arch Intern Med|volume=155|issue=15|pages=1605–9|pmid=7618983}}</ref> The incidence rate of Herpes zoster in persons aged 65 or older is approximately 19 per 1000 individuals per year in the US. The incidence in this age group of a white ethnic background is approximately 3.5 times higher than in the same age group of a Hispanic ethnic background.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Chaves SS, Santibanez TA, Gargiullo P, Guris D|title=Chickenpox exposure and herpes zoster disease incidence in older adults in the U.S.|journal=Public Health Rep|volume=122|issue=2|date=2007|pmid=17357357}}</ref> It can also be seen in ] individuals undergoing severe emotional ].<ref>{{cite journal|title=Stress-induced subclinical reactivation of varicella zoster virus in astronauts|author=Mehta SK, Cohrs RJ, Forghani B, Zerbe G, Gilden DH, & Pierson DL|date=2004|journal=J Med Virol|volume=72|issue=1|pages=174–9|pmid=14635028}}</ref> | |||

| Varicella zoster virus (VZV) has a high level of ] and has a worldwide prevalence.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Apisarnthanarak A, Kitphati R, Tawatsupha P, Thongphubeth K, Apisarnthanarak P, Mundy LM |title=Outbreak of varicella-zoster virus infection among Thai healthcare workers |journal=] |volume=28 |issue=4 |pages=430–434 |year=2007 |pmid=17385149 |doi=10.1086/512639 |s2cid=20844136 }}</ref> Shingles is a re-activation of latent VZV infection: zoster can only occur in someone who has previously had chickenpox (varicella). | |||

| Shingles has no relationship to season and does not occur in epidemics. There is, however, a strong relationship with increasing age.<ref name="Hope-Simpson"/><ref name=pmid14720565/> The incidence rate of shingles ranges from 1.2 to 3.4 per 1,000 person‐years among younger healthy individuals, increasing to 3.9–11.8 per 1,000 person‐years among those older than 65 years,<ref name=Dwo2007/><ref name="Hope-Simpson"/> and incidence rates worldwide are similar.<ref name=Dwo2007/><ref name=pmid17939895>{{cite journal| vauthors=Araújo LQ, Macintyre CR, Vujacich C| title=Epidemiology and burden of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in Australia, Asia and South America| journal=]| volume=14| issue=Suppl 2| pages=40A–44A| year=2007| pmid=17939895| url=http://www.ihmf.org/journal/download/5%20-%20Herpes%2014.2%20suppl%20Araujo.pdf| access-date=16 December 2007| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191205132432/http://www.ihmf.org/journal/download/5%20-%20Herpes%2014.2%20suppl%20Araujo.pdf| archive-date=5 December 2019| url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| In the United States, herpes zoster affects about 10–20% of the population (although nearly 100% of the population has been exposed to varicella-zoster by age 60). The rate is approximately 131 per 100,000 person-years in white individuals. Similar rates of infection have been observed worldwide.<ref name="pmid17143845"/> | |||

| This relationship with age has been demonstrated in many countries,<ref name=Dwo2007/><ref name="pmid17939895"/><ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Brisson M, Edmunds WJ, Law B, Gay NJ, Walld R, Brownell M, Roos LL, De Serres G | display-authors = 6 | title = Epidemiology of varicella zoster virus infection in Canada and the United Kingdom| journal = ] | year = 2001| volume = 127| issue = 2| pages = 305–314| pmid = 11693508| doi = 10.1017/S0950268801005921| pmc = 2869750}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Insinga RP, Itzler RF, Pellissier JM, Saddier P, Nikas AA | title = The incidence of herpes zoster in a United States administrative database| journal = ] | year = 2005| volume = 20| issue = 8| pages = 748–753| pmid = 16050886| doi = 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0150.x| pmc = 1490195}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, St Sauver JL, Kurland MJ, Sy LS | title = A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction| journal = ]| year = 2007| volume = 82| issue = 11| pages = 1341–1349| pmid = 17976353| doi=10.4065/82.11.1341}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = de Melker H, Berbers G, Hahné S, Rümke H, van den Hof S, de Wit A, Boot H| display-authors = 6| title = The epidemiology of varicella and herpes zoster in The Netherlands: implications for varicella zoster virus vaccination| journal = ]| year = 2006| volume = 24| issue = 18| pages = 3946–3952| pmid = 16564115| doi = 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.017| hdl = 10029/5604| url = http://rivm.openrepository.com/rivm/bitstream/10029/5604/1/melker2006.pdf| hdl-access = free| access-date = 3 September 2019| archive-date = 8 August 2017| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170808211650/http://rivm.openrepository.com/rivm/bitstream/10029/5604/1/melker2006.pdf| url-status = live}}</ref> and is attributed to the fact that cellular immunity declines as people grow older. | |||

| Another important risk factor is ].<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors = Colebunders R, Mann JM, Francis H, Bila K, Izaley L, Ilwaya M, Kakonde N, Quinn TC, Curran JW, Piot P | display-authors = 6 | title = Herpes zoster in African patients: a clinical predictor of human immunodeficiency virus infection| journal = ]| volume = 157| issue = 2| pages = 314–318| doi = 10.1093/infdis/157.2.314| year = 1988| pmid = 3335810}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Buchbinder SP, Katz MH, Hessol NA, Liu JY, O'Malley PM, Underwood R, Holmberg SD | display-authors = 6 | title = Herpes zoster and human immunodeficiency virus infection| journal = ]| year = 1992| volume = 166| issue = 5| pages = 1153–1156| doi = 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1153| pmid = 1308664}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| vauthors = Tsai SY, Chen HJ, Lio CF, Ho HP, Kuo CF, Jia X, Chen C, Chen YT, Chou YT, Yang TY, Sun FJ, Shi L | display-authors = 6 |date=22 August 2017|title=Increased risk of herpes zoster in patients with psoriasis: A population-based retrospective cohort study|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=12|issue=8|pages=e0179447|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0179447|pmid=28829784|issn=1932-6203|bibcode=2017PLoSO..1279447T|pmc=5567491| doi-access = free }}</ref> Other risk factors include ].<ref name=pmid15307000/><ref>{{cite journal| author = Livengood JM| title = The role of stress in the development of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia| journal = ]| year = 2000| volume = 4| issue = 1| pages = 7–11| pmid = 10998709| doi = 10.1007/s11916-000-0003-9 | s2cid = 37086354}}</ref><ref name="Gatti2010">{{cite journal| vauthors = Gatti A, Pica F, Boccia MT, De Antoni F, Sabato AF, Volpi A | title = No evidence of family history as a risk factor for herpes zoster in patients with post-herpetic neuralgia| journal = ]| year = 2010| volume = 82| issue = 6| pages = 1007–1011| pmid = 20419815| doi = 10.1002/jmv.21748| hdl = 2108/15842| s2cid = 31667542 | hdl-access = free}}</ref> According to a study in North Carolina, "black subjects were significantly less likely to develop zoster than were white subjects."<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Schmader K, George LK, Burchett BM, Pieper CF | title = Racial and psychosocial risk factors for herpes zoster in the elderly| journal = ]| year = 1998| volume = 178| issue = Suppl 1| pages = S67–S70| pmid = 9852978| doi = 10.1086/514254| doi-access = free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Schmader K, George LK, Burchett BM, Hamilton JD, Pieper CF | title = Race and stress in the incidence of herpes zoster in older adults| journal = ]| year = 1998| volume = 46| issue = 8| pages = 973–977| pmid = 9706885| doi=10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02751.x| s2cid = 7583608 }}</ref> It is unclear whether the risk is different by sex. Other potential risk factors include ] and exposure to ]s.<ref name=pmid14720565/><ref name="Gatti2010"/> | |||

| According to a review of the disease in the United States, one million consultations for herpes zoster occur per year; approximately 250,000 of the patients examined develop herpes zoster ophthalmicus. A subset of 50% of these patients develops complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Pavan-Langston D|title=Herpes zoster opthalmicus|journal=Neurology|date=1995|volume =45|issue=12 Suppl 8|pages=50–1|pmid=8545020}}</ref> Ramsay Hunt syndrome is the cause of as many as 12% of all cases of facial paralysis.<ref name="Johnson"/> | |||

| There is no strong evidence for a genetic link or a link to family history. A 2008 study showed that people with close relatives who had shingles were twice as likely to develop it themselves,<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Hicks LD, Cook-Norris RH, Mendoza N, Madkan V, Arora A, Tyring SK | title = Family history as a risk factor for herpes zoster: a case-control study| journal = ]| volume = 144| issue = 5| pages = 603–608|date=May 2008| pmid = 18490586| doi = 10.1001/archderm.144.5.603| doi-access = free}}</ref> but a 2010 study found no such link.<ref name="Gatti2010"/> | |||

| Adults with latent VZV infection who are exposed intermittently to children with chickenpox receive an immune boost.<ref name="Hope-Simpson"/><ref name="Gatti2010"/> This periodic boost to the immune system helps to prevent shingles in older adults. When routine chickenpox vaccination was introduced in the United States, there was concern that, because older adults would no longer receive this natural periodic boost, there would be an increase in the incidence of shingles. | |||