| Revision as of 13:42, 13 June 2009 editSkäpperöd (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers18,457 edits →Middle Ages: minority position indicated. still think it is better to apply wp:undue here.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:57, 6 January 2025 edit undoBartleby08 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,458 editsm →Bibliography | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Capital city of West Pomerania, Poland}} | |||

| :''For other meanings, see ] and ].'' | |||

| {{Redirect|Stettin||Stettin (disambiguation)|and|Szczecin (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Settlement | |||

| {{Distinguish|Szechuan}} | |||

| |name = Szczecin | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2020}} | |||

| |nickname = Floating Garden | |||

| {{Infobox settlement | |||

| |motto = "Szczecin jest otwarty" <br/>(''"Szczecin is open"'') | |||

| | name = Szczecin | |||

| |image_skyline = PolandSzczecinPanorama.JPG | |||

| | other_name = {{lang|de|Stettin}} | |||

| |imagesize = 250px | |||

| | motto = "{{lang|pl|Szczecin jest otwarty}}" <br />("Szczecin is open") | |||

| |image_caption = ] in Szczecin | |||

| | image_skyline = {{multiple image | |||

| |image_flag = POL Szczecin flag.svg | |||

| | border = infobox | |||

| |image_shield = POL Szczecin COA.svg | |||

| | perrow = 2/2/2/1 | |||

| |pushpin_map = Poland | |||

| | total_width = 270 | |||

| |pushpin_label_position = bottom | |||

| | align = center | |||

| |subdivision_type = Country | |||

| | caption_align = center | |||

| |subdivision_name = {{POL}} | |||

| | image1 = Wały Chrobrego in Szczecin, winter 2021.jpg | |||

| |subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| | caption1 = ]—], ] | |||

| |subdivision_name1 = ] | |||

| | image2 = Szczecin Hanza Tower dron (1) (cropped).jpg | |||

| |subdivision_type2 = ] | |||

| | caption2 = ] | |||

| |subdivision_name2 = ''city county'' | |||

| | image3 = Town hall in Szczecin, September 2022 01.jpg | |||

| |leader_title = Mayor | |||

| | caption3 = ] | |||

| |leader_name = Piotr Krzystek | |||

| | image4 = Filharmonia Szczecinska cb.JPG | |||

| |established_title = Established | |||

| | caption4 = ] | |||

| |established_date = 8th century | |||

| | image5 = Red Town Hall in Szczecin, 2021.jpg | |||

| |established_title3 = Town rights | |||

| | caption5 = Red Town Hall | |||

| |established_date3 = 1243 | |||

| | image6 = Akademia Sztuki w Szczecinie, Pałac Ziemstwa Pomorskiego.jpg | |||

| |area_total_km2 = 301 | |||

| | caption6 = ] | |||

| |population_as_of = 2007 | |||

| | image7 = Most Kolejowy w Szczecinie (dron1) (cropped)2.jpg | |||

| |population_total = 407811 | |||

| | caption7 = ], with the ] in the distance | |||

| |population_density_km2 = auto | |||

| }} | |||

| |population_metro = 777000 | |||

| | image_flag = POL Szczecin flag.svg | |||

| |timezone = ] | |||

| | image_shield = POL Szczecin COA.svg | |||

| |utc_offset = +1 | |||

| | image_blank_emblem = Logo szczecin.svg | |||

| |timezone_DST = ] | |||

| | blank_emblem_type = ] | |||

| |utc_offset_DST = +2 | |||

| | pushpin_map = Poland | |||

| |latd = 53 | latm = 25 | lats = | latNS = N | longd = 14 | longm = 35 | longs = | longEW = E | |||

| | pushpin_label_position = right | |||

| |postal_code_type = Postal code | |||

| | subdivision_type = ] | |||

| |postal_code = PL-70-017<br>to 71-871 | |||

| | subdivision_name = {{POL}} | |||

| |area_code = +48 91 | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| |website = http://www.szczecin.pl | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = ] | |||

| |blank_name = ] | |||

| | subdivision_type2 = ] | |||

| |blank_info = ZS }} | |||

| | subdivision_name2 = City county | |||

| ] | |||

| | leader_party = ] | |||

| ] | |||

| | leader_title = City mayor | |||

| ] | |||

| | leader_name = ] | |||

| ] | |||

| | established_title = Established | |||

| ] | |||

| | established_date = 8th century | |||

| ]: the pre-war Poles in Szczecin, the Poles who rebuilt the city after ] and the modern generation]] | |||

| | established_title3 = City rights | |||

| ] and Wały Chrobrego]] | |||

| | established_date3 = 1243 | |||

| | area_total_km2 = 301 | |||

| | area_metro_km2 = 2795 | |||

| | population_as_of = 31 December 2021 | |||

| | population_total = 395,513 {{decrease}} (])<ref name="population">{{cite web|url=https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/dane/podgrup/tablica|title=Local Data Bank|access-date=10 February 2024|publisher=Statistics Poland}} Data for territorial unit 3262000.</ref> | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 1340 | |||

| | population_metro = 777000 | |||

| | population_density_metro_km2 = 278 | |||

| | population_demonym = szczecinianin (male) <br/> szczecinianka (female) (]) | |||

| | timezone = ] | |||

| | utc_offset = +1 | |||

| | timezone_DST = ] | |||

| | utc_offset_DST = +2 | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|53|25|57|N|14|32|53|E|region:PL|display=title,inline}} | |||

| | postal_code_type = Postal code | |||

| | postal_code = PL-70-017<br />to 71–871 | |||

| | area_code = +48 91 | |||

| | blank_name = ] | |||

| | blank_info = ZS | |||

| | blank1_name = ] | |||

| | blank1_info = ] | |||

| | blank_name_sec2 = Primary airport | |||

| | blank_info_sec2 = ] | |||

| | website = {{URL|https://www.szczecin.pl}} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Szczecin''' ({{IPAc-en|UK|ˈ|ʃ|tʃ|ɛ|tʃ|ɪ|n}} {{respell|SHCHETCH|in}},<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.lexico.com/definition/Szczecin |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200116223906/https://www.lexico.com/definition/szczecin |url-status=dead |archive-date=2020-01-16 |title=Szczecin |dictionary=] UK English Dictionary |publisher=]}}</ref> {{IPAc-en|US|-|tʃ|iː|n}} {{respell|-|een}},<ref>{{Cite American Heritage Dictionary|Szczecin|access-date=18 August 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/szczecin|title=Szczecin|work=]|publisher=]|access-date=18 August 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite Merriam-Webster|Szczecin|access-date=18 August 2019}}</ref> {{IPA-pl|ˈʂt͡ʂɛt͡ɕin|lang|Pl-Szczecin-2.ogg}}; {{langx|de|Stettin}} {{IPA|de|ʃtɛˈtiːn||De-Stettin.ogg}}; {{langx|sv|Stettin}} {{IPA|sv|stɛˈtiːn|}}; {{langx|la|Sedinum}} or {{lang|la|Stetinum}})<ref>Johann Georg Theodor Grässe: '''', Meere, Seen, Berge und Flüsse in allen Theilen der Erde nebst einem deutsch-lateinischen Register derselben. T. Ein Supplement zu jedem lateinischen und geographischen Wörterbuche. Dresden: G. Schönfeld’s Buchhandlung (C. A.Werner), 1861, p. 179, 186, 278. .</ref> is the ] and largest city of the ] in northwestern ]. Located near the ] and the ], it is a major ] and Poland's seventh-largest city. {{As of|2022|12|31|post=,}} the population was 391,566.<ref name="population" /> | |||

| Szczecin is located on the ] River, south of the ] and the ]. The city is situated along the southwestern shore of ], on both sides of the Oder and on several large islands between the western and eastern branches of the river. It is also surrounded by dense forests, shrubland and ]s, chiefly the ] shared with Germany (Ueckermünde) and the ]. Szczecin is adjacent to the ] and is the urban centre of the ], an extended metropolitan area that includes communities in the ] of ] and ]. | |||

| '''Szczecin''' {{IPAr|pl|AUD|Szczecin.ogg|'|sz|cz|e|ć|i|n}} ({{lang-de|Stettin}} {{IPA|]]}} {{Audlisten|Stettin.ogg}}; {{lang-csb|Sztetëno}} {{IPA|]]}}; {{lang-la|Stetinum}}) is the ] of ] in ]. It is the country's seventh-largest city and the largest ] in Poland on the ]. As of the 2005 ] the city had a total population of 420,638. In 2007 its population was 407,811. | |||

| The city's recorded history dates back over 1,300 years, when diverse tribes and peoples such as the ] and ] erected strongholds in the vicinity. It subsequently served as the seat of the ] and the ]. In the course of the millennium, Szczecin under different names was part of ], ], ], the ], ], Germany and modern-day Poland. The city's architecture and cultural heritage reflects these periods, with excellent examples of ], ], ], ] and contemporary styles. The planned urban landscape was based on the ], with avenues, roundabouts and extensive parkland. The city's chief landmarks include the ], the ], the ] and the ]. | |||

| Szczecin is located on the ], south of the ] and the ]. The city is situated along the southwestern shore of ], on both sides of Oder and on several large islands between western and eastern branch of the river. Szczecin borders with ], seat of the ], situated at an ] of the Oder River. | |||

| Szczecin is the administrative and industrial centre of West Pomeranian Voivodeship and is the site of the ], ], ], ], ], and the see of the ]. From 1999 onwards, Szczecin has served as the site of the ] of ]'s ]. The city was a candidate for the ] in 2016.<ref name="szczecin2016.pl">{{cite web|url=http://www.szczecin2016.pl/esk2016/chapter_89000.asp|title=Strona domeny www.szczecin2016.pl|work=szczecin2016.pl|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100817102057/http://www.szczecin2016.pl/esk2016/chapter_89000.asp|archive-date=17 August 2010}}</ref> | |||

| The city is on the ]. | |||

| ==Name and |

== Name and etymology == | ||

| {{lang|pl|Szczecin}} and {{lang|de|Stettin}} are the Polish and German equivalents of the same name, which is of ] origin, though the exact etymology is the subject of ongoing research.<ref name="Bialecki">{{cite book|first=Tadeusz|last=Białecki|title=Historia Szczecina|publisher=] |year=1992 |location=Wrocław |pages=9, 20–55, 92–95, 258–260, 300–306}}</ref>{{efn |Spelling variants in medieval sources include: | |||

| * ''Stetin'',<ref name=Labuda14/> recorded e.g. in 1133,<ref name=Labuda14>Gerard Labuda, Władysław Filipowiak, Helena Chłopocka, Maciej Czarnecki, Tadeusz Białecki, Zygmunt Silski, ''Dzieje Szczecina 1–4'', Państwowe Wydawn. Nauk., 1994, p.{{nbsp}}14, {{ISBN|83-01-04342-3}}</ref> 1159,<ref name=Labuda14/> 1177<ref name=Labuda14/> | |||

| * ''Stetyn'',<ref name=Labuda14/> recorded, e.g., in 1188,<ref name=Labuda14/> 1243<ref name=Labuda14/> | |||

| * ''Stetim'', 1237<ref name=Lizak/> | |||

| * ''Szcecin'', 1273.<ref name=Lizak>Wojciech Lizak, "Jak wywodzono nazwę Szczecina?", , last accessed 4/2/2011</ref> | |||

| * ''Stetina'',<ref name=Labuda14/> by Herbord<ref name=Labuda14/> | |||

| * ''Sthetynensibus'' or ''Sthetyn'', 1287, in Anglicised medieval Latin.<ref name=Lizak/> (The ending ''–ens–ibus'' means 'to the people of' in Latin.) | |||

| * ''Stetinum'' and ''Sedinum'', still used in contemporary ] language references | |||

| * ''Stitin'', recorded, e.g., in 1251,<ref name=Labuda14/> in the ''Annales Ryensis'',<ref name=Labuda14/> in 1642<ref>Merians anmüthige Städte-Chronik, das ist historische und wahrhaffte Beschreibung und zugleich Künstliche Abcontrafeyung zwantzig vornehmbster und bekantester in unserm geliebten Vatterland gelegenen Stätte, 1642</ref> | |||

| * ''Stitinum'', by ]<ref name=Labuda14/> | |||

| * ''Stittinum'' | |||

| * ''Stytin'',<ref name=Labuda14/> in the ''Annales Colbacensis''.<ref name=Labuda14/>}} | |||

| In her ''Etymological Dictionary of Geographical Names of Poland'', Maria Malec lists 11 theories regarding the origin of the name, including derivations from either: an Old Slavic word for 'hill peak' ({{langx|pl|szczyt|links=no}}), the plant ] ({{langx|pl|szczeć|links=no}}), or the ] {{lang|pl|Szczota}}.<ref>Słownik etymologiczny nazw geograficznych Polski Profesor Maria Malec PWN 2003</ref> | |||

| Other medieval names for the town are ''Burstaborg'' (in the ])<ref name=Labuda14/><ref name=Rospond162>Stanisław Rospond, Slawische Namenkunde Ausg. 1,{{nbsp}}Nr.{{nbsp}}3, C.{{nbsp}}Winter, 1989, p.{{nbsp}}162</ref> and ''Burstenburgh'' (in the Annals of Waldemar).<ref name =Labuda14/><ref name=Rospond162/> These names, which literally mean 'brush burgh', are likely derived from the translation of the city's Slavic name (assuming derivation No. 2 for that).<ref name=Rospond162/> | |||

| Professor Maria Malec in ''Etymological dictionary of geographical names of Poland'' has counted 11 distinct theories regarding the origin of the name exist. She has determined that the most important theories link the name to ''Szczyt'', name of a hill peak, ''Szczeć'', description of grass, or ''Szczota'', a personal name.<ref>Słownik etymologiczny nazw geograficznych Polski Profesor Maria Malec PWN 2003</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| Historian Marian Gumowski argued, based on his studies of early city stamps and seals, that the earliest name of the town was ''Szczycin''.{{cn}} | |||

| {{Main|History of Szczecin}} | |||

| {{For timeline}} | |||

| <!-- NOTE: EDITS LACKING SOLID REFERENCES ARE SUBJECT TO REMOVAL --> | |||

| === Middle Ages === | |||

| As the city was colonised by Germans, the early name was also Germanised.<ref name="Bialecki"/> | |||

| ] commemorating the ] (a ] people), with an image of the Pomeranian ]]] | |||

| The recorded ] began in the eighth century, when ]<ref>"Vikingar", Natur och Kultur 1995, {{ISBN|91-27-91001-6}} (CD)</ref> and ] settled in ]. The West Slavs, or ], erected a new ] on the site of the ].<ref name=Piskorski52/> | |||

| In ], the city is referred to as ''Stetinum''. Early medieval sources vary somewhat: ''Stetin'' 1133, ''Stetyn'' 1188, ''Priznoborus vir nobilis in Stetin, Symon nobilis Stettinensis'' 1234, ''in vico Stetin'' 1240, ''Barnim Dei gratia dux Pomeranorum... civitati nostri Stetin'' 1243, ''Stityn'' 1251, ''Sigillum Burgoncium de Stitin'' municipal seal from the 13th century. | |||

| Since the 9th century, the stronghold was fortified and expanded toward the ].<ref name=Piskorski52>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}52, {{ISBN|83-906184-8-6}} {{OCLC|43087092}}</ref> ] took control of ] and the region became part of Poland in the 10th century.<ref>The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 11, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1998, p.{{nbsp}}473 "In the 8th and 9th centuries Szczecin was a Slavic fishing and commercial settlement, later named Western Pomerania (Pomorze Zachodnie). During the 10th century, it was annexed to Poland by ]</ref><ref>The Origins of Polish state. Mieszko I and Bolesław Chrobry. Professor Henry Lang, Polish Academic Information Center, University at Buffalo. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120206100818/http://info-poland.buffalo.edu/classroom/orig/mieszko.html |date=6 February 2012 }}</ref> However, already ] (1025 ~ 1034) effectively lost control over the area and had to accept German suzerainty over the area of the Oder lagoon.<ref>{{cite book|author=Charles Higounet|title=Die deutsche Ostsiedlung im Mittelalter|page=141|language=de}}</ref> Subsequent Polish rulers, the Holy Roman Empire, and the ] all aimed to control the territory.<ref name="Bialecki"/> | |||

| After the decline of the neighbouring regional centre ] in the 12th century, the city became one of the more important and powerful seaports of the Baltic Sea.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Addyman et al., 1979 |date=1981 |title=Waterfront Archaeology in Britain and Northern Europe: A review of current research in waterfront archaeology in six European countries, based on the papers presented to the First International Conference on Waterfront Archaeology in North European Towns held at the Museum of London on 20-22 April 1979 |url=https://woolmerforest.org.uk/E-Library/W/WATERFRONT%20ARCHAEOLOGY%20IN%20BRITAIN%20AND%20NORTHERNN%20EUROPE.pdf |journal=Council for British Archaeology Research Reports |volume=41 |pages=69 |via=The Council for British Archaeology}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=September 24, 2023 |title=Port of Szczecin |url=http://www.worldportsource.com/ports/review/POL_Port_of_Szczecin_1178.php |access-date=September 24, 2023 |website=World Port Source |archive-date=26 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231126002019/http://www.worldportsource.com/ports/review/POL_Port_of_Szczecin_1178.php |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| In 1310, ], ] founded the city of ''Neustettin'' (literally "New Stettin", now '']''). For distinction, the original Szczecin was sometimes called "Old Szczecin" ({{lang-pl|Stary Szczecin}}). | |||

| In a campaign in the winter of 1121–1122,<ref name=Piskorski36>Jan M. Piskorski, ''Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten'', 1999, pg. 36; {{ISBN|83-906184-8-6}}, {{OCLC|43087092}}</ref> ], the Duke of ], gained control of the region, including the city of Szczecin and its stronghold.<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref name=Piskorski3136>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, pp. 31,36,43 {{ISBN|83-906184-8-6}} {{OCLC|43087092}}: pg. 31 (yrs 967-after 1000 AD): " gelang es den polnischen Herrschern sicherlich nicht, Wollin und die Odermündung zu unterwerfen." pg. 36: "Von 1119 bis 1122 eroberte er schließlich das pommersche Odergebiet mit Stettin, " pg. 43: " während Rügen 1168 erobert und in den dänischen Staat einverleibt wurde."</ref><ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp. 100–101, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref><ref>Norbert Buske, Pommern, Helms Schwerin 1997, pp. 11ff; {{ISBN|3-931185-07-9}}</ref><ref>], Die Geschichte Pommerns, Hinstorff Rostock, 2008, pp.{{nbsp}}15ff; {{ISBN|978-3-356-01044-2}}: pp. 14–15: "Die westslawischen Stämme der Obroditen, Lutizen und Pomoranen konnten sich lange der Eroberung widersetzen. Die militärisch überlegenen Mächte im Norden und Osten, im Süden und im Westen übten jedoch einen permanenten Druck auf den südlichen Ostseeraum aus. Dieser ging bis 1135 hauptsächlich von Polen aus. Der polnische Herzog Boleslaw III Krzywousty (Schiefmund) unterwarf in mehreren Feldzügen bis 1121 pomoranisches Stammland mit den Hauptburgen Cammin und Stettin und drang weiter gen Westen vor", pg. 17: Das Interesse Waldemars richtete sich insbesondere auf das Siedlungsgebiet der Ranen, die nördlich des Ryck und auf Rügen siedelten und die sich bislang gegen Eroberer und Christianisierungsversuche gewehrt hatten. und nahmen 1168 an König ]. Kriegszug gegen die Ranen teil. Arkona wurde erobert und zerstört. Die unterlegenen Ranen versprachen, das Christentum anzunehmen, die Oberhoheit des Dänenkönigs anzuerkennen und Tribut zu leisten."</ref><ref name="Barber">Malcolm Barber, "The two cities: medieval Europe, 1050–1320", Routledge, 2004, pg. 330 </ref><ref>An historical geography of Europe, 450 B.C.{{nsndns}}A.D. 1330, Norman John Greville Pounds, Cambridge University Press 1973, pg. 241, "By 1121 Polish armies had penetrated its forests, captured its chief city of Szczecin."</ref>{{Excessive citations inline|date=December 2023}} The Polish ruler initiated Christianization, entrusting this task to ],<ref>{{cite book|last=Medley|first=D. J.|year=2004|title=The church and the empire|publisher=Kessinger Publishing|page=152}}</ref> and the inhabitants were Christianised<ref name="Bialecki"/> by two missions of Otto in 1124 and 1128.<ref>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, pp. 36ff; {{ISBN|83-906184-8-6}}, {{OCLC|43087092}}</ref> At this time, the first Christian church of Saints Peter and Paul was erected. The Poles' minted coins were commonly used in trade in this period.<ref name="Bialecki"/> The population of the city at that time is estimated to be at around 5,000–9,000 people.<ref>''Archeologia Polska'', Volume 38, Instytut Historii Kultury Materialnej (Polska Akademia Nauk, pg. 309, Zakład im. Ossolińskich, 1993.</ref> | |||

| While most of the names had been Germanised, after 1945 the Slavic-sounding original names of locations in Pomerania were restored.{{cn}} Among others, Szczecin's name was restored from Stettin.<ref name="Bialecki"/>{{Request quotation}} | |||

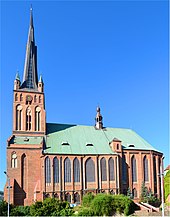

| ], first built in the 14th century]] | |||

| Polish rule ended with Boleslaw's death in 1138.<ref>Kyra Inachim, ''Die Geschichte Pommerns'', Hinstorff Rostock, 2008, pg. 17; {{ISBN|978-3-356-01044-2}}: "Mit dem Tod Kaiser Lothars 1137 endete der sächsische Druck auf Wartislaw I., und mit dem Ableben Boleslaw III. auch die polnische Oberhoheit."</ref> During the ] in 1147, a contingent led by the German margrave ], an enemy of Slavic presence in the region,<ref name="Bialecki"/> papal legate, bishop ] and ] besieged the town.<ref name=Schimmelpfennig16>Bernhard Schimmelpfennig, ''Könige und Fürsten, Kaiser und Papst nach dem Wormser Konkordat'', Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1996, pg. 16; {{ISBN|3-486-55034-9}}</ref><ref name=Fuhrmann147>Horst Fuhrmann, Deutsche Geschichte im hohen Mittelalter: Von der Mitte des 11. Bis zum Ende des 12. Jahrhunderts, 4th edition, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, pg. 147; {{ISBN|3-525-33589-X}}</ref><ref>Peter N. Stearns, ], ], ], 2001; pg. 206 @ {{Dead link|date=May 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref><ref>Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford: ]; {{ISBN|0-06-097468-0}}, pg. 362</ref> There, a Polish contingent supplied by ]<ref name=Piskorski43>Jan M. Piskorski, ''Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten'', 1999, pg. 43; {{ISBN|83-906184-8-6}} {{OCLC|43087092}}: Greater Polish continguents of Mieszko the Elder</ref><ref name=Heitz163>{{cite book|title=Geschichte in Daten. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern|first1=Gerhard|last1=Heitz|first2=Henning|last2=Rischer|publisher=Koehler&Amelang|location=Münster-Berlin|year=1995|isbn=3-7338-0195-4|language=de|page=163}}</ref> joined the crusaders.<ref name=Schimmelpfennig16/><ref name=Fuhrmann147/> However, the citizens had placed crosses around the fortifications,<ref>Jean Richard, Jean Birrell, "The Crusades, c.{{nbsp}}1071{{nsndns}}c.{{nbsp}}1291", ], 1999, p.{{nbsp}}158, </ref> indicating they already had been Christianised.<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref>Jonathan Riley-Smith, "The Crusades: A History", Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005, p.{{nbsp}}130, </ref> Duke ] of ], negotiated the disbanding of the crusading forces.<ref name=Schimmelpfennig16/><ref name=Fuhrmann147/><ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}30, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> | |||

| After the ] in 1164, Szczecin duke ] became a vassal of the Duchy of Saxony's ].<ref name="Buchholz, p.{{nbsp}}34">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}34, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> In 1173, Szczecin ] ], could not resist a Danish attack and became vassal of ].<ref name="Buchholz, p.{{nbsp}}34"/> In 1181, Bogusław became a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire.<ref name="Buchholz, p.{{nbsp}}35">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}35, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> In 1185, Bogusław again became a Danish vassal.<ref name="Buchholz, p.{{nbsp}}35"/> Despite falling under foreign suzerainty, local dukes maintained close ties with the fragmented Polish realm, and future Polish monarch ] stayed at the local court of Duke Bogusław I in 1186, on behalf of his father, Duke of ] ], who also periodically was the ].<ref>{{cite magazine|last=Krasuski|first=Marcin|year=2018|title=Walka o władzę w Wielkopolsce w I połowie XIII wieku|magazine=Officina Historiae|language=pl|issue=1|page=64|issn=2545-0905}}</ref> Following a conflict between his heirs and ], the settlement was destroyed in 1189,<ref name=riis48>{{cite book|title=Studien Zur Geschichte Des Ostseeraumes IV. Das Mittelalterliche Dänische Ostseeimperium|first=Thomas|last=Riis|publisher=Ludwig|year=2003|isbn=87-7838-615-2|page=48}}</ref> but the fortress was reconstructed and manned with a Danish force in 1190.<ref>Université de Caen. Centre de recherches archéologiques médiévales, ''Château-Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale, XVIII : actes du colloque international tenu à Gilleleje, Danemark, 24–30 août 1996'', CRAHM, 1998, p.{{nbsp}}218, {{ISBN|978-2-902685-05-9}}</ref> While the empire restored its superiority over the Duchy of Pomerania in the ] in 1227,<ref name="Buchholz, p.{{nbsp}}35"/> Szczecin was one of two bridgeheads remaining under Danish control (until 1235; ] until 1241/43 or 1250).<ref name=riis48/> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{main|History of Szczecin}} | |||

| <!-- NOTE: EDITS LACKING SOLID REFERENCES ARE SUBJECT TO REMOVAL --> | |||

| In the second half of the 12th century, a group of German tradesmen ("multus populus Teutonicorum"<ref name=Heitz168>{{cite book|title=Geschichte in Daten. Mecklenburg-Vorpommern|first1=Gerhard|last1=Heitz|first2=Henning|last2=Rischer|publisher=Koehler&Amelang|location=Münster-Berlin|year=1995|isbn=3-7338-0195-4|language=de|page=168}}</ref> from various parts of the Holy Roman Empire) settled in the city around St.{{nbsp}}Jacob's Church, which was donated in 1180<ref name=Heitz168/> by Beringer, a trader from ], and consecrated in 1187.<ref name=Heitz168/><ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p. 43, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> Hohenkrug (now in ]) was the first village in the Duchy of Pomerania that was clearly recorded as German (''villa teutonicorum'') in 1173.<ref>Jan Maria Piskorski, Slawen und Deutsche in Pommern im Mittelalter, in Klaus Herbers, Nikolas Jaspert, Grenzräume und Grenzüberschreitungen im Vergleich: der Osten und der Westen des mittelalterlichen Lateineuropa, Akademie Verlag, 2007, p.{{nbsp}}85, {{ISBN|3-05-004155-2}}</ref> ] accelerated in Pomerania during the 13th century.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}43ff, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> Duke ] of Pomerania granted Szczecin a ] charter in 1237, separating the German settlement from the Slavic community settled around the ] Church in the neighbourhood of Kessin ({{langx|pl|Chyzin}}). In the charter, the Slavs were put under Germanic jurisdiction.<ref>Jan Maria Piskorski, Slawen und Deutsche in Pommern im Mittelalter, in Klaus Herbers, Nikolas Jaspert, Grenzräume und Grenzüberschreitungen im Vergleich: der Osten und der Westen des mittelalterlichen Lateineuropa, Akademie Verlag, 2007, p.{{nbsp}}86, {{ISBN|3-05-004155-2}}</ref> | |||

| === Middle Ages === | |||

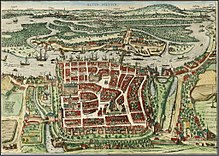

| The history of Szczecin began in the 8th century, when ] ] and erected a ], later with an adjacent settlement, on the site of the ]. ] and Piast rulers ] during the years 960-1005 but not the lower ] region.<ref name=Piskorski31>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, pp.31,32, ISBN 839061848</ref><ref name=Knoll>Paul W. Knoll, Frank Schaer, annotaded Gesta Principum Polonorum: The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles by Gallus, Central European University Press, 2003, p.32, ISBN 9639241407</ref>. Subsequent attempts were made to gain control of the region by Polish rulers, rivaling with the ] and ] for the control of the territory.<ref name="Bialecki"/> | |||

| ], the seat of the dukes of the ], which was founded by Duke ]]] | |||

| After the decline of neighboring regional center ] in the 12th century, the settlement became one of the more important and powerful seaports of the Baltic Sea south coasts. | |||

| When Barnim granted Szczecin ] in 1243, part of the Slavic settlement was reconstructed.<ref>{{cite book|title=Geschichte Mecklenburg-Vorpommerns|publisher=Beck|first=Michael|last=North|year=2008|isbn=978-3-406-57767-3|language=de|page=21}}</ref> The duke had to promise to level the burgh in 1249.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}83, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> Most Slavic inhabitants were resettled to two new suburbs north and south of the town.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}84, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> | |||

| In a campaign in the winter of ]–],<ref name=Piskorski36>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.36, ISBN 839061848</ref> ], the Duke of Poland, gained control of the stronghold.<ref name=Piskorski36>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, p.36, ISBN 839061848</ref/> Bialecki (1992)<ref name="Bialecki"/> and Barber (2004) in a book about medieval Europe<ref name="Barber">Malcolm Barber, "The two cities: medieval Europe, 1050-1320", Routledge, 2004, pg. 330 </ref> describe this as a regain of territory - up to the island of ] (according to Bialecki), or up to the Oder line in 1129 (according to Barber). The books about Pomeranian history of historians Piskorski (1999),<ref name=Piskorski3136>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeit, 1999, pp.31, 36ff, ISBN 839061848</ref/> Buchholz (1999),<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.100-101, ISBN 3886802728</ref> Buske (1997),<ref>Norbert Buske, Pommern, Helms Schwerin 1997, pp.11ff, ISBN 3-931185-07-9</ref> Knoll and Schaer (2003),<ref name=Knoll/> Inachim (2008),<ref>Kyra Inachim, Die Geschichte Pommerns, Hinstorff Rostock, 2008, pp.15ff, ISBN 978-3-356-01044-2</ref> contradict these informations saying the area was not subjugated before, that the Stettin campaign of Boleslaw had already crossed the Oder line, and that the ], despite the subsequent westward expansion of ], was independent until the Danish capture in 1168. Polish rule integrated the ] into the framework of a developed feudal state.<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref name="Barber"/> Polish minted coins were commonly used in trade in this period.<ref name="Bialecki"/> <!-- Sure that this is relevant? It is not surprising that a Polish-ruled town would use Polish currency. --> The inhabitants ]<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref name="Barber"/> by two missions of bishop ] in ] and ]. At this time, the first Christian church of St. Peter and Paul was erected. | |||

| In 1249, Barnim I also granted equivalent Magdeburg town privileges to the town of Damm (also known as Altdamm) on the eastern bank of the Oder.<ref>Roderich Schmidt, ''Pommern und Mecklenburg'', Böhlau, 1981, p.{{nbsp}}61, {{ISBN|3-412-06976-0}}</ref><ref name=Johanek277>Peter Johanek, Franz-Joseph Post, ''Städtebuch Hinterpommern 2–3'', ], 2003, p.{{nbsp}}277, {{ISBN|3-17-018152-1}}</ref> Damm merged with neighbouring Szczecin on 15{{nbsp}}October 1939 and is now the ] neighbourhood.<ref>Johannes Hinz, ''Pommernlexikon'', Kraft, 1994, p.{{nbsp}}25, {{ISBN|3-8083-1164-9}}</ref> This town had been built on the site of a former ] burg, "Vadam" or "Dambe", which Boleslaw had destroyed during his 1121 campaign.<ref name=Johanek277/> | |||

| Those gains were hindered by German aggression and expansion, resulting in weakening of connections of Szczecin with Poland, under the leadership of the German Margrave ], who was a sworn enemy of Slavic presence in the region. Organizing a expedition by German knights and Denmark he plundered the area in the so called ], burned down settlements and murdered local population before moving on to besiege Szczecin itself. The crusaders faced a city surrounded by crosses,<ref>Jean Richard, Jean Birrell, "The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291", Cambridge University Press, 1999, pg. 158, </ref> which was meant to indicate that their claims of fighting pagans were false, as Szczecin had already been Christianized. <ref name="Bialecki"/><ref>Jonathan Riley-Smith, "The Crusades: A History", Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005, pg. 130, </ref> In the end the siege did not result in subjugation of the city.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.30, ISBN 3886802728</ref> . | |||

| On 2 December 1261, Barnim I allowed Jewish settlement in Szczecin in accordance with the Magdeburg law, in a privilege renewed in 1308 and 1371.<ref name=heitmann225>{{citation|last=Heitmann|first=Margret|chapter=Synagoge und freie christliche Gemeinde in Stettin|title="Halte fern dem ganzen Lande jedes Verderben..". Geschichte und Kultur der Juden in Pommern|editor1-last=Heitmann|editor1-first=Margret|editor2-last=Schoeps|editor2-first=Julius|publisher=Olms|location=Hildesheim/Zürich/New York|year=1995|language=de|isbn=3-487-10074-6|pages=225–238; p. 225}}</ref> The Jewish Jordan family was granted citizenship in 1325, but none of the 22 Jews allowed to settle in the duchy in 1481 lived in the city, and in 1492, all Jews in the duchy were ordered to convert to Christianity or leave{{snds}}this order remained effective throughout the rest of the Griffin era.<ref name=heitmann225/> | |||

| In the second half of the 12th century, a group of German tradesmen (from various parts of the ]) settled in the city around St. Jacob's Church, which was founded by Beringer, a trader from ], and consecrated in 1187.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.43, ISBN 3886802728</ref> After the 1164 ], Stettin duke ] became a vassal of the ]<ref name="Buchholz, p.34">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.34, ISBN 3886802728</ref>. In 1173, Stettin castellan ] could not resist a Danish attack and became vassal of Denmark.<ref name="Buchholz, p.34"/> In 1181, duke Bogislaw I of Stettin became a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire.<ref name="Buchholz, p.35">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.35, ISBN 3886802728</ref> From 1185 to 1227, Stettin dukes were again vassals of Denmark.<ref name="Buchholz, p.35"/> The burgh was manned with a Danish force and reconstructed in 1190.<ref>Université de Caen. Centre de recherches archéologiques médiévales, ''Château-Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale, XVIII : actes du colloque international tenu à Gilleleje, Danemark, 24-30 août 1996'', CRAHM, 1998, p.218, ISBN 290268505</ref> | |||

| In 1273, in Szczecin duke of ] and future King of Poland ] married princess ], granddaughter of ], in order to strengthen the alliance between the two rulers.<ref>''Kronika wielkopolska'', ], Warszawa, 1965, p. 297 (in Polish)</ref> | |||

| German settlement (]) accelerated in Pomerania during the 13th century.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.43ff, ISBN 3886802728</ref> Duke ] granted a local government charter to this community in 1237, separating the German settlement from the Slavic community settled around the St. Nicholas Church in the neighborhood of Kessin ({{lang-pl|Chyzin}}). When Barnim granted Stettin ] in 1243, the old Slavic settlement with its burgh was included within the city limits, which is exceptional for Pomeranian towns usually not comprising former Slavic settlements or burghs, though sometimes founded in close proximity.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.75, ISBN 3886802728</ref> The former Slavic settlement was dissolved when, after the town was placed under German town law, the duke had to promise to level the burgh in 1249.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.83, ISBN 3886802728</ref> Most Slavic inhabitants were resettled to two new suburbia ({{lang-de|Wieken}}) north and south of the town.<ref>Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.84, ISBN 3886802728</ref> | |||

| Szczecin was part of the federation of ], a predecessor of the ], in 1283.<ref name="Wernicke">{{cite book |last=Wernicke |first=Horst |chapter=Die Hansestädte an der Oder |title=Oder-Odra. Blicke auf einen europäischen Strom |editor1-first=Karl |editor1-last=Schlögel |editor2-first=Beata |editor2-last=Halicka |publisher=Lang |year=2007 |isbn=978-3-631-56149-2 |pages=137–48; here p. 142 |language=de}}</ref> The city prospered due to its participation in the ] trade, primarily with ], grain, and timber; craftsmanship also prospered, and more than forty guilds were established in the city.<ref name=aps344/> The far-reaching autonomy granted by the House of Griffins was in part reduced when the dukes reclaimed Stettin as their main residence in the late 15th century.<ref name=aps344/> The anti-Slavic policies of German merchants and craftsmen intensified in this period, resulting in measures such as bans on people of Slavic descent joining ] guilds, a doubling of customs tax for Slavic merchants, and bans against public usage of their native language.<ref name="Bialecki"/> The more prosperous Slavic citizens were forcibly stripped of their possessions, which were then handed over to Germans.<ref name="Bialecki"/> In 1514, the guild of tailors added a ''Wendenparagraph'' to its statutes, banning Slavs.<ref name=slaski97>{{cite book|last=Ślaski|first=Kazimierz|chapter=Volkstumswandel in Pommern vom 12. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert|editor-last=Kirchhoff|editor-first=Hans Georg|title=Beiträge zur Geschichte Pommerns und Pommerellens. Mit einem Geleitwort von Klaus Zernack|location=Dortmund|year=1987|isbn=3-923293-19-4|pages=94–109; p. 97|language=de |publisher=Forschungsstelle Ostmitteleuropa }}</ref> | |||

| Stettin joined the ] in 1278. The anti-Slavic policies of German merchants and craftsmen intensified in this period, resulting in bans on people of Slavic descent joining ]s, or even bans against public usage of native Slavic language<ref name="Bialecki"/>. In Szczecin, richer Slavic citizens were forcefully stripped of their possessions which were awarded to Germans<ref name="Bialecki"/>. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1570, ] ending the Northern Seven Years' War. | |||

| While not as heavily affected by medieval ] as other regions of the empire, there are reports of the burning of three women and one man convicted of ] in 1538.<ref>Hubertus Fischer, ''Klosterfrauen, Klosterhexen: Theodor Fontanes Sidonie von Borcke im kulturellen Kontext : Klosterseminar des Fontane-Kreises Hannover der Theodor-Fontane-Gesellschaft e.V. mit dem Konvent des Klosters St. Marienberg vom 14. bis 15. November 2003 in Helmstedt'', Rübenberger Verlag Tania Weiss, 2005, p.{{nbsp}}22, {{ISBN|3-936788-07-3}}</ref> | |||

| The last ], ] died when the duchy was made a party in the ]. Since the ], the town along with most of Pomerania was allied to and occupied by the ], who managed to keep the ] after the ] in 1648, despite the protests of Elector ] of ], who had a legal claim to inherit all of Pomerania. The exact partition of Pomerania between Sweden and Brandenburg was ]. In 1720, after the ], the Swedes were forced to cede the city to King ]. Stettin developed into a major ] city and became part of the Prussian-led ] in 1871. | |||

| In 1570, during the reign of ], ] ending the ]. During the war, Stettin had tended to side with ], while ] tended toward ]{{snds}}as a whole, however, the Duchy of Pomerania tried to maintain neutrality.<ref name=Inachim62>Kyra Inachim, ''Die Geschichte Pommerns'', Hinstorff Rostock, 2008, p.{{nbsp}}62, {{ISBN|978-3-356-01044-2}}</ref> Nevertheless, a ] that had met in Stettin in 1563 introduced a sixfold rise in real estate taxes to finance the raising of a mercenary army for the duchy's defence.<ref name=Inachim62/> Johann Friedrich also succeeded in elevating Stettin to one of only three places allowed to ] in the ] of the Holy Roman Empire, the other two places being ] and ].<ref>Joachim Krüger, ''Zwischen dem Reich und Schweden: die landesherrliche Münzprägung im Herzogtum Pommern und in Schwedisch-Pommern in der frühen Neuzeit (ca. 1580 bis 1715)'', LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2006, pp.{{nbsp}}53–55, {{ISBN|3-8258-9768-0}}</ref> ], who resided in Stettin beginning in 1620, became the sole ruler and Griffin duke when ] died in 1625. Before the ] reached Pomerania, the city, as well as the entire duchy, declined economically due to the decrease in importance of the Hanseatic League and a conflict between Stettin and ].<ref name=Inachim65>Kyra Inachim, ''Die Geschichte Pommerns'', Hinstorff Rostock, 2008, p.{{nbsp}}65, {{ISBN|978-3-356-01044-2}}</ref> | |||

| Despite the fact that the city was no longer a part of Poland and had underwent a process of Germanisation, a Polish population still lived in the city and numbered 3,000 people<ref name="Bialecki"/>, including a few wealthy industrialists and merchants, before WW I. Among them was ], director of industrial works Gollnow, and a Polish patriot who predicted eventual return of Szczecin to Poland<ref name="Bialecki"/>. | |||

| === |

=== 17th to 18th centuries === | ||

| ] | |||

| Following the ], the town (along with most of Pomerania) was allied to and occupied by the ], which managed to keep the ] after the death of Bogislaw{{nbsp}}XIV in 1637. From the ] in 1648, Stettin became the Capital of Swedish Pomerania.<ref name="auto">Swedish encyclopedia "Bonniers lexikon" (1960's), vol 13:15, column 1227</ref> Stettin was turned into a major Swedish fortress, which was repeatedly besieged in subsequent wars.<ref name=aps345/> The next ] did not change this, but due to the downfall of the Swedish Empire after ], the city went to ] in 1720.<ref name="auto"/> Instead Stralsund became capital of the last remaining parts of Swedish Pomerania 1720–1815.<ref>Swedish encyclopedia "Bonniers lexikon" (1960's), vol 13:15, column s 709-710</ref> | |||

| In 1935 the German ] made Stettin the headquarters for ], which controlled the military units in all of ] and Pomerania. It was also the Area Headquarters for units stationed at Stettin I and II; ]; ]; and ]. | |||

| The city was on the path of Polish forces led by ] ] moving from Denmark during the ]. Czarniecki, who led his forces to the city,<ref>''Historia Szczecina: zarys dziejów miasta od czasów najdawniejszych'', Tadeusz Białecki, 1992: "Nowa wojna polsko-szwedzka w połowie XVII w. nie ominęła i Szczecina. Oprócz zwiększonych podatków i zahamowania handlu w 1657 r. pod Szczecinem pojawiły się oddziały polskie Stefana Czarnieckiego"</ref> is today mentioned in the ], and numerous locations in the city honour his name. | |||

| In 1939 Stettin had about 400,000 inhabitants, the surrounding villages were included into "Groß-Stettin". It was Germany's third-biggest seaport (after ] and ]) and was of great importance for the supply and trade of ]. Cars of the ] automobile company were produced in Stettin from 1899 - 1945. | |||

| Wars inhibited the city's economic prosperity, which had undergone a deep crisis during the devastation of the Thirty Years' War and was further impeded by the new Swedish-Brandenburg-Prussian frontier, cutting Stettin off from its traditional ]n hinterland.<ref name=aps344>], ''Staatsarchiv Stettin: Wegweiser durch die Bestände bis zum Jahr 1945'', German translation of Radosław Gaziński, Paweł Gut, Maciej Szukała, ''Archiwum Państwowe w Szczecinie, Poland. Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych'', Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2004, p.{{nbsp}}344, {{ISBN|3-486-57641-0}}</ref> Due to a ] during the ], the city's population dropped from 6,000 people in 1709 to 4,000 in 1711.<ref name="Buchholz, p.{{nbsp}}532">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}532, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> In 1720, after the Great Northern War, Sweden was forced to cede the city to King ]. Stettin was made the capital city of ], since 1815 reorganised as the ]. In 1816, the city had 26,000 inhabitants.<ref name="Buchholz, p. 416">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}416, {{ISBN|3-88680-272-8}}</ref> | |||

| In the interwar period the Polish presence fell to 2,000 people<ref name="Bialecki"/>. Neverthless the Polish minority remained active despite repressions <ref name="Bialecki"/><ref> Polonia szczecińska 1890-1939 Anna Poniatowska Bogusław Drewniak, Poznań 1961</ref>. A number of Poles were members of Union of Poles in Germany, a Polish scouts team was established<ref name="Bialecki"/>. Additionally a Polish schoold was created where ] was tought. Repressions, intensified especially after ] came to power led to closing of the school<ref name="Bialecki"/>. Members of Polish community who took part in cultural and political activities were persecuted and even murdered. In 1938 the head of Szczecin’s Union of Poles unit Stanisław Borkowski was imprisoned in ] <ref name="Bialecki"/>. In 1939 all Polish organisations in Szczecin were disbanded by German authorities and during the war teachers from Polish school, Golisz and Omieczyński murdered<ref name="Bialecki"/>. | |||

| The Prussian administration deprived the city of its right to administrative autonomy, abolished ] privileges as well as its status as a staple town, and subsidised manufacturers.<ref name=aps345/> Also, colonists were settled in the city, primarily ] ].<ref name=aps345/> The French established a prosperous community, greatly contributed to the city's economic revival, and were treated with reluctance by the German burghers and city authorities.<ref>{{cite book|last=Skrycki|first=Radosław|editor-last=Rembacka|editor-first=Katarzyna|year=2011|title=Szczecin i jego miejsca. Trzecia Konferencja Edukacyjna, 10 XII 2010 r.|language=pl|location=Szczecin|page=96|chapter=Z okresu wojny i pokoju – "francuskie" miejsca w Szczecinie z XVIII i XIX wieku|isbn=978-83-61233-45-9}}</ref> | |||

| During the 1939 ], which started World War II in Europe, Stettin was the base for the ], which cut across the ]. | |||

| === 19th to 20th centuries === | |||

| As the war started the number of non-Germans in the city increased as slave workers were brought in. The first transports came in 1939 from ], ] and ]. They were mainly used in synthetic silk factory near Szczecin<ref name="Bialecki"/>. Next wave of slave workers was brought in 1940 in addition to PoWs who were used to work in agricultural industry<ref name="Bialecki"/>. According to German police reports from 1940 the Polish population in the city reached 15,000 people, while 25,000 foreigners were registered in general<ref name="Bialecki"/>. | |||

| In October 1806, during the ], believing that he was facing a much larger force, and after receiving a threat of harsh treatment of the city, the Prussian commander ] agreed to ] to the French led by ].<ref>Petre, 252–253</ref> In fact, Lasalle had only 800 men against von{{nbsp}}Romberg's 5,300 men. In March 1809 Romberg was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for giving up Stettin without a fight. In 1809, also Polish troops were stationed in the city, while the French remained until 1813. | |||

| ] | |||

| In February 1940, ] to the ]. International press reports emerged writing how the Nazis forced Jews regardless of age, condition and gender to sign away all property-including wedding rings-and loaded on trains escorted by SA and SS. Due to publicity of the event, German institutions ordered such actions in the future to be made in a way not arousing public notice.<ref>The Origins of the Final Solution Christopher R. Browning, Jürgen Matthäus page 64 ] Press, 2007</ref> | |||

| From 1683 to 1812, one Jew was permitted to reside in Stettin, and an additional Jew was allowed to spend a night in the city in case of "urgent business".<ref name=heitmann225/> These permissions were repeatedly withdrawn between 1691 and 1716, also between 1726 and 1730 although else the Swedish regulation was continued by the Prussian administration.<ref name=heitmann225/> Only after the ] of 11{{nbsp}}March 1812, which granted Prussian citizenship to all Jews living in the kingdom, did a Jewish community emerge in Stettin, with the first Jews settling in the town in 1814.<ref name=heitmann225/> Construction of a synagogue started in 1834; the community also owned a religious and a secular school, an orphanage since 1855, and a retirement home since 1893.<ref name=heitmann226>{{citation|last=Heitmann|first=Margret|chapter=Synagoge und freie christliche Gemeinde in Stettin|title="Halte fern dem ganzen Lande jedes Verderben..". Geschichte und Kultur der Juden in Pommern|editor1-last=Heitmann|editor1-first=Margret|editor2-last=Schoeps|editor2-first=Julius|publisher=Olms|location=Hildesheim/Zürich/New York|year=1995|language=de|isbn=3-487-10074-6|pages=225–238; p. 226}}</ref> The Jewish community had between 1,000 and 1,200 members by 1873 and between 2,800 and 3,000 members by 1927{{nsndns}}28.<ref name=heitmann226/> These numbers dropped to 2,701 in 1930 and to 2,322 in late 1934.<ref name=heitmann226/> | |||

| During the war 135 work camps for slave workers were established in the city. Most of the slave workers were Poles, besides them Czechs, Italians, Frenchmen and Belgians as well Dutch were served in the camps<ref name="Bialecki"/>. | |||

| After the ], 1,700 French ]s were imprisoned there in deplorable conditions, resulting in the deaths of 600;<ref>Kultura i sztuka Szczecina w latach 1800–1945:materiały Seminarium Oddziału Szczecińskiego Stowarzyszenia Historyków Sztuki, 16–17 październik 1998 Stowarzyszenie Historyków Sztuki. Oddział Szczeciński. Seminarium, Maria Glińska</ref> after the Second World War monuments in their memory were built by the Polish authorities. | |||

| Allied air raids in 1944 and heavy fighting between the German and ] armies destroyed 65% of Stettin's buildings and almost all of the city centre, seaport and industries. | |||

| In April 1945 the authorities of the city issued an order of evacuation and most of the city’s German population fled. | |||

| ] | |||

| Until 1873, Stettin remained a fortress.<ref name=aps345/> When part of the defensive structures were levelled, a new neighbourhood, ''Neustadt'' ("New Town") as well as water pipes, ] and drainage, and gas works were built to meet the demands of the growing population.<ref name=aps345/> | |||

| The Soviet ] captured the city on 26 April 1945. Many of the city's inhabitants fled before its capture, and Stettin was virtually deserted when it fell, with only 6,000 Germans in the city when Polish authorities took control <ref name="Bialecki"/>. In the following month the city was handed over to Polish administration three times, permanently on 5 July 1945. In the meantime part of the German population had returned, believing it might become part of the ] in Germany. Stettin is located mostly west of the ] river, which was considered to become Poland's new border. However, Stettin and the mouth of the Oder River ({{lang-de|Stettiner Zipfel}}), also became Polish as already stated in Treaty signed on 26 VII 1944 between Soviet Union and ] and confirmed during ] <ref name="Bialecki"/>.. On 4 X 1945 the decisive land border of Poland was laid out west from 1945 and Szczecin officially became once more part of Polish state<ref name="Bialecki"/>. | |||

| Stettin developed into a major Prussian port and became part of the ] in 1871. While most of the province retained its agrarian character, Stettin was ], and its population rose from 27,000 in 1813 to 210,000 in 1900 and 255,500 in 1925.<ref name="Schmidt 2009 19–20">{{cite book|last=Schmidt|first=Roderich|title=Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse|volume=41|series=Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern|edition=2|publisher=Böhlau|location=Köln-Weimar|year=2009|isbn=978-3-412-20436-5|language=de|pages=19–20}}</ref> Major industries that flourished in Stettin from 1840 were shipbuilding, chemical and food industries, and machinery construction.<ref name=aps345/> Starting in 1843, Stettin became connected to the major German and Pomeranian cities by railways, and the water connection to the ] was enhanced by the construction of the ] (now Piast) canal.<ref name=aps345/> The city was also a scientific centre; for example, it was home to the ]. | |||

| The Polish authorities were led by Piotr Zaremba. Many remaining Germans were forced to work in Soviet military camps that were outside of Polish jurisdiction. | |||

| In 1945 the Polish community in Stettin consisted of ] from the ]. The city's ] and Stettin was resettled with ]. Additional Poles were moved to the city from ]. This settlement process was coordinated by the city of Poznań, and Stettin's name was restored to the Polish name Szczecin. In 1947, after ], a significant number of ] came to Szczecin, having been forced by the Communist government to leave eastern Poland. | |||

| ] | |||

| The new citizens of Szczecin rebuilt and extended the city's industry and industrial areas, as well as its cultural heritage, although efforts were hampered by the authorities of ]. Szczecin became a major Polish industrial centre and an important seaport (particularly for ]n coal) for both Poland, ], and ]. The city witnessed anti-communist revolts in 1970 and 1980 and participated in the growth of the ] movement during the 1980s. Since 1999 Szczecin has been the capital of the ]. | |||

| On 20 October 1890, some of the city's Poles created the "Society of Polish-Catholic Workers" in the city, one of the first Polish organisations.<ref>Dzieje Szczecina:1806–1945 p.{{nbsp}}450 Bogdan Frankiewicz 1994</ref> In 1897, the city's ship works began the construction of the ] battleship '']''. In 1914, before World War{{nbsp}}I, the Polish community in the city numbered over 3,000 people,<ref name="Bialecki"/> contributing about 2% of the population.<ref name="Schmidt 2009 19–20"/> These were primarily industrial workers and their families who came from the ] (Posen) area<ref name=Musekamp72>{{cite book|title=Zwischen Stettin und Szczecin|volume=27|series=Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Polen-Instituts Darmstadt|first=Jan|last=Musekamp|publisher=Harrassowitz Verlag|year=2009|isbn=978-3-447-06273-2|language=de|page=72}}. Quote1: " Polen, die sich bereits vor Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges in der Stadt befunden hatten. Es handelte sich bei ihnen zum einen um Industriearbeiter und ihre Angehörigen, die bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg meist aus der Gegend um Posen in das damals zum selben Staat gehörende Stettin gezogen waren "</ref> and a few local wealthy industrialists and merchants. Among them was Kazimierz Pruszak, director of the Gollnow industrial works and a Polish patriot, who predicted the eventual "return" of Szczecin to Poland.<ref name="Bialecki"/> | |||

| ==Architecture and urban planning== | |||

| Szczecin's architectural style is mainly influenced by those of the last half of the 19th century and the first years of the 20th century: ] and ]. In many areas built after 1945, especially in the city centre, which had been destroyed due to Allied bombing, ] is prevalent. | |||

| During the ], Stettin was ]'s largest port on the Baltic Sea, and her third-largest port after ] and ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Schmidt|first=Roderich|title=Das historische Pommern. Personen, Orte, Ereignisse|volume=41|series=Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern|edition=2|publisher=Böhlau|location=Köln-Weimar|year=2009|isbn=978-3-412-20436-5|language=de|page=20}}</ref> Cars of the ] automobile company were produced in Stettin from 1899 to 1945. By 1939, the ] ]{{nsndns}}Stettin was completed.<ref name=aps345/> | |||

| Urban planning of Szczecin is unusual. The first thing observed by a newcomer is abundance of green areas: ]s and avenues{{ndash}} wide streets with trees planted in the island separating opposite traffic (where often ] tracks are laid); and ]. Thus, Szczecin's city plan resembles that of ]. This is because Szczecin was rebuilt in the ] according to a design by ], who had ] under ]. | |||

| Stettin played a major role as an entrepôt in the development of the Scottish herring trade with the Continent, peaking at an annual export of more than 400,000 barrels in 1885, 1894 and 1898. Trade flourished until the outbreak of the First World War and resumed on a reduced scale during the years between the wars.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.scottishherringhistory.uk/statistics/AnnualExport.html|title=Annual Statistics|work=scottishherringhistory.uk}}</ref> | |||

| This course of designing streets in Szczecin is still used, as many recently built (or modified) city areas include roundabouts and avenues. | |||

| In the ] to the Reichstag, the Nazis and German nationalists from the ] (or DNVP) won most of the votes in the city, together winning 98,626 of 165,331 votes (59.3%), with the NSDAP getting 79,729 (47.9%) and the DNVP 18,897 (11.4%).<ref name="verwaltungsgeschichte.de">{{cite web |url=http://www.verwaltungsgeschichte.de/stettin.html |title=Deutsche Verwaltungsgeschichte Pommern, Kreis Stettin |publisher=Verwaltungsgeschichte.de |access-date=2011-06-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110723075150/http://www.verwaltungsgeschichte.de/stettin.html |archive-date=23 July 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Within Szczecin's boundaries is part of the ] called ] in the forest of Puszcza Bukowa. | |||

| In 1935, the ] made Stettin the headquarters for Wehrkreis{{nbsp}}II, which controlled the ] in all of ] and Pomerania. It was also the area headquarters for units stationed at Stettin{{nbsp}}I and II; Swinemünde (]); ]; and ]. | |||

| <div style="width:90%; overflow:auto; padding:0px; text-align:left; border:solid 1px; color:gray" title="panorama"> | |||

| ]</div><font size="1">Szczecin harbour and ] panorama</font> | |||

| In the interwar period, the Polish minority numbered 2,000 people,<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref name="AP & BD 1961">Polonia szczecińska 1890–1939 Anna Poniatowska Bogusław Drewniak, Poznań 1961</ref> less than 1% of the city's population at that time.<ref name="Schmidt 2009 19–20"/> A number of Poles were members of the ] (ZPN), which was active in the city from 1924.<ref>''Historyczna droga do polskiego Szczecina:wybór dokumentów i opracowań''. Kazimierz Kozłowski, Stanisław Krzywicki. Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, p.{{nbsp}}79, 1988</ref> A Polish consulate was located in the city between 1925 and 1939.<ref name=Musekamp73>{{cite book|title=Zwischen Stettin und Szczecin|volume=27|series=Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Polen-Instituts Darmstadt|first=Jan|last=Musekamp|publisher=Harrassowitz Verlag|year=2009|isbn=978-3-447-06273-2|language=de|page=73}}</ref> On the initiative of the consulate<ref name=Musekamp73/> and ZPN activist Maksymilian Golisz,<ref name=Musekamp74>{{cite book|title=Zwischen Stettin und Szczecin|volume=27|series=Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Polen-Instituts Darmstadt|first=Jan|last=Musekamp|publisher=Harrassowitz Verlag|year=2009|isbn=978-3-447-06273-2|language=de|page=74}}</ref> a number of Polish institutions were established, e.g., a Polish Scout team and a Polish school.<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref name=Musekamp73/> German historian Musekamp writes, "however, only very few Poles were active in these institutions, which for the most part were headed by employees of the consulate."<ref name=Musekamp74/> The withdrawal of the consulate from these institutions led to a general decline of these activities, which were in part upheld by Golisz and Aleksander Omieczyński.<ref>{{cite book|title=Konsulat Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w Szczecinie w latach 1925–1939. Powstanie i działalność|first=Wojciech|last=Skóra|publisher=Pomorska Akademia Pedagogiczna w Słupsku|year=2001|isbn=83-88731-15-7|language=pl|page=139}}</ref> Intensified repressions by the Nazis,<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref name="AP & BD 1961"/> who exaggerated the Polish activities to propagate an infiltration,<ref name=Musekamp74/> led to the closing of the school.<ref name="Bialecki"/> In 1938, the head of Szczecin's Union of Poles unit, Stanisław Borkowski, was imprisoned in ] concentration camp in ].<ref name="Bialecki"/> In 1939, all Polish organisations in Stettin were disbanded by the German authorities.<ref name="Bialecki"/> Golisz and Omieczyński were murdered during the war.<ref name="Bialecki"/> After the defeat of Nazi Germany, a street was named after Golisz.<ref name=Musekamp74/> According to German historian Jan Musekamp, the activities of the Polish pre-war organizations were exaggerated after World War II for propaganda purposes.<ref>Musekamp, Jan: Zwischen Stettin und Szczecin, p. 74, with reference to: Edward Wlodarczyk: "Próba krytycznego spojrzenia na dzieje Polonii Szczecińskiej do 1939 roku" in Pomerania Ethnica, Szczecin 1998 Quote: ''"..und so musste die Bedeutung der erwähnten Organisationen im Sinne der Propaganda übertrieben werden."''</ref> | |||

| ===Municipal administration=== | |||

| The city is administratively divided into boroughs (Polish: ''dzielnica''), which are further divided into smaller neighbourhoods. The governing bodies of the latter serve the role of auxiliary local government bodies called ''] Councils'' (Polish: ''Rady Osiedla''). ]s for Neighborhood Councils are held up to six months after each City Council elections. Attendance <!-- should this be "voter turnout"? --> is rather low (on 20 May 2007 it ranged from 1.03% to 27.75% and was 3.78% on average). ]s are responsible mostly for small infrastructure like trees, park benches, ]s, etc. Other functions are mostly advisory. | |||

| ] | |||

| ==== World War II ==== | |||

| '''Dzielnica Śródmieście (City Centre)''' | |||

| During ], Stettin was the base for the ], which cut across the ] and was later used in 1940 as an embarkation point for ], Germany's assault on Denmark and ].<ref>Gilbert, M (1989) Second World War, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, P52</ref> | |||

| ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]. | |||

| On 15 October 1939, neighbouring municipalities were joined to Stettin, creating Groß-Stettin, with about 380,000 inhabitants, in 1940.<ref name=aps345>Peter Oliver Loew, ''Staatsarchiv Stettin: Wegweiser durch die Bestände bis zum Jahr 1945'', German translation of Radosław Gaziński, Paweł Gut, Maciej Szukała, ''Archiwum Państwowe w Szczecinie, Poland. Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych'', Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2004, p.{{nbsp}}345, {{ISBN|3-486-57641-0}}</ref> The city had become the third-largest German city by area, after Berlin and Hamburg.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stolzenburg|first=Katrin|chapter=Hans Bernhard Reichow (1899–1974)|title=Architektur und Städtebau im südlichen Ostseeraum zwischen 1936 und 1980|editor-first=Bernfried|editor-last=Lichtnau|publisher=Lukas Verlag|year=2002|isbn=3-931836-74-6|language=de|pages=137–152; p. 140}}</ref> | |||

| '''Dzielnica Północ (North)''' | |||

| ], ]-], ], ], ], ], ]. | |||

| As the war started, the number of non-Germans in the city increased as ] were brought in. The first transports came in 1939 from ], ] and ]. They were mainly used in a synthetic silk factory near Stettin.<ref name="Bialecki"/> The next wave of slave workers was brought in 1940, in addition to PoWs who were used for work in the agricultural industry.<ref name="Bialecki"/> According to German police reports from 1940, 15,000 Polish slave workers lived within the city.<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Tey6mM1RCs0C&q=autochthons+poland&pg=PA72 | |||

| '''Dzielnica Zachód (West)''' | |||

| |title=Zwischen Stettin und Szczecin|first1=Jan|last1=Musekamp|publisher=Deutsches Polen-Institut|year=2010|isbn=978-3-447-06273-2|page=72|language=de|access-date=20 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ]-], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]. | |||

| During the war, 135 forced labour camps for slave workers were established in the city. Most of the 25,000 slave workers were Poles, but ], ], Frenchmen and ], as well as Dutch citizens, were also enslaved in the camps.<ref name="Bialecki"/> A Nazi prison was also operated in the city, with forced labour subcamps in the region.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/haftstaetten/index.php?action=2.2&tab=7&id=100001209|title=Gefängnis Stettin|website=Bundesarchiv.de|access-date=15 May 2021|language=de}}</ref> | |||

| '''Dzielnica Prawobrzeże (Right-Bank)''' | |||

| ]-], ], ], ]-]-], ], ], ]-], ], ], ]-]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Other historical neigbourhoods=== | |||

| ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]. | |||

| In February 1940, ] to the ]. International press reports emerged, describing how the Nazis forced Jews, regardless of age, condition and gender, to sign away all property and loaded them onto trains headed to the camp, escorted by members of the ] and ]. Due to publicity given to the event, German institutions ordered such future actions to be made in a way unlikely to attract public notice.<ref>''The Origins of ]'' ], ], page 64 ] Press, 2007</ref> The action was the first deportation of Jews from prewar territory in Nazi Germany.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry|url=https://archive.org/details/holocaustfateofe00yahi|url-access=limited|last=Yahil|first=Leni|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1990|isbn=0-19-504522-X|location=Oxford|pages=}}</ref> | |||

| == Historical population == | |||

| {{Refimprove|section|date=April 2007}} | |||

| *12th century: 5,000 inhabitants | |||

| *1709: 6,000 inhabitants<ref name="Buchholz, p.532">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.532, ISBN 3886802728</ref> | |||

| *1711: 4,000 inhabitants (])<ref name="Buchholz, p.532"/> | |||

| *1720: 6,000 inhabitants | |||

| *1740: 12,300 inhabitants | |||

| *1816: 21,500 inhabitants | |||

| *1816: 26,000 inhabitants<ref name="Buchholz, p.416">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.416, ISBN 3886802728</ref> | |||

| *1843: 37,100 inhabitants | |||

| *1861: 58,500 inhabitants | |||

| *1872: 76,000 inhabitants | |||

| *1875: 80,972 inhabitants<ref name="Buchholz, p.534">Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.534, ISBN 3886802728</ref> | |||

| *1890: 116,228 inhabitants<ref name="Buchholz, p.534"/> | |||

| *1900: 210,680 inhabitants (including amalgated suburbs) | |||

| *1910: 236,113 inhabitants<ref name="Buchholz, p.534"/> | |||

| *1939: 382,000 inhabitants | |||

| *1945: 260,000 inhabitants (majority of the ]) | |||

| *1950: 180,000 inhabitants (drop due to continuing expulsions of Germans) | |||

| *1960: 269,400 inhabitants (arrival of Polish population from the ]) <!-- "Recovered Territories" was mostly a Soviet propaganda term; we shouldn't link to it when discussing demographics or geography --> | |||

| *1970: 338,000 inhabitants | |||

| *1975: 369,700 inhabitants | |||

| *1980: 388,300 inhabitants | |||

| *1990: 412.600 inhabitants | |||

| *1995: 418.156 inhabitants | |||

| *2000: 415,748 inhabitants | |||

| *2002: 415,117 inhabitants | |||

| *2003: 414,032 inhabitants | |||

| *2004: 411,900 inhabitants | |||

| *2005: 411,119 inhabitants | |||

| *2007: 407,811 inhabitants | |||

| ] ] in 1944 and heavy fighting between the German and ] armies destroyed 65% of Stettin's buildings and almost all of the city centre, the seaport, and local industries. Polish ] intelligence assisted in pinpointing targets for Allied bombing in the area of Stettin.<ref>Polski ruch oporu 1939–1945 Andrzej Chmielarz, Wojskowy Instytut Historyczny im. Wandy Wasilewskiej, Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1988 page 1019</ref> The city itself was covered by the Home Army's "Bałtyk" structure, and Polish resistance infiltrated Stettin's naval yards.<ref>Wywiad Związku Walki Zbrojnej—Armii Krajowej, 1939–1945 Piotr Matusak 2002 page 166</ref><ref>Wywiad Polskich Sił Zbrojnych na Zachodzie 1939–1945 Andrzej Pepłoński AWM, 1995 page 342</ref> Other activities of the resistance consisted of smuggling people to Sweden.<ref>Cudzoziemcy w polskim ruchu oporu: 1939–1945 Stanisław Okęcki 1975 page 49</ref> | |||

| ===Members of European Parliament (]s) from Szczecin=== | |||

| * ], ], historian, former rector of ]. | |||

| * ], ], economist, minister of transport. | |||

| * ], ], architect and politician, elected in Silesian constituency, but lives in Szczecin. | |||

| The Soviet ] captured the city on 26{{nbsp}}April 1945. While the majority of the almost 400,000 inhabitants had left the city, between 6,000 and 20,000 inhabitants remained in late April.<ref name=Dok>{{cite book| first1=Jörg |last1=Hackmann| first2=Tadeusz | last2=Bialecki|title=Stettin Szczecin 1945-1946 Dokument – Erinnerungen, Dokumenty - Wspomnienia |publisher=Hinstorff|year=1995 | pages=97, 283, 287 |isbn= 3-356-00528-6|language=de}}</ref> | |||

| ==Economy== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] from the ] River. Most of the medieval buildings in the city centre were completely destroyed during ]. The ] can be seen in the background.]] | |||

| Szczecin has three shipyards (], ], ]), of which one is the biggest in Poland (], which five years ago went bankrupt and was reinstated). It has a fishing industry and a steel mill. It is served by ] and by the ], third biggest port of Poland. It is also home to several major companies. Among them is the major food producer ], ], producer of construction materials Komfort, Bosman brewery and ] drug factory. It also houses several of the ''new business'' firms in the IT sector. | |||

| On 28 April 1945 Polish authorities tried to gain control,<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref name=Dok/> but in the following month, the Polish administration was twice forced to leave. The reason for this was, according to Polish sources, that the Western Allies raised protest against the Soviet and Polish policy of creating a fait-accomplit in ].<ref name=Musekamp72/> Finally the permanent handover occurred on 5{{nbsp}}July 1945.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.szczecin.pl/strasse/kalendar_uk.htm|title=Chronicle of the most important events in the history of Szczecin|work=Szczecin.pl|date=2000|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110607192402/http://www.szczecin.pl/strasse/kalendar_uk.htm |archive-date=7 June 2011}}</ref> In the meantime, part of the German population had returned, believing it might become part of the ].<ref name=Piskorski376>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}376, {{ISBN|83-906184-8-6}} {{OCLC|43087092}}</ref> The Soviet authorities had already appointed the German Communists Erich Spiegel and ] as mayors.<ref>Grete Grewolls: ''Wer war wer in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern? Ein Personenlexikon''. Edition Temmen, Bremen 1995, {{ISBN|3-86108-282-9}}, p.{{nbsp}}467.</ref> Stettin is located mostly west of the Oder River, which was expected to become Poland's new western border, placing Stettin in East Germany. This would have been in accordance with the ] between the victorious Allied powers, which envisaged the ] to be in "a line running from the Baltic Sea immediately west of Swinemünde, and thence along the Oder River". Because of the returnees, the German population of the town swelled to 84,000.<ref name=Piskorski376/> The ] was at 20%, primarily due to starvation.<ref name=Piskorski377>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, p.{{nbsp}}377, {{ISBN|83-906184-8-6}} {{OCLC|43087092}}</ref> However, Stettin and the mouth of the Oder River became Polish on 5{{nbsp}}July 1945, as had been decided in a treaty signed on 26{{nbsp}}July 1944 between the Soviet Union and the Soviet-controlled ] (PKWN) (also known as "the Lublin Poles", as contrasted with the ]-based ]).<ref name="Bialecki"/> On 4{{nbsp}}October 1945, the decisive land border of Poland was established west of the 1945 line,<ref name="Bialecki"/><ref name=Piskorski380381>Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, pp. 380–381, {{ISBN|83-906184-8-6}} {{OCLC|43087092}}</ref> and the city was renamed to its historic Polish name Szczecin, but the area excluded the ] area, the Oder River itself and the port of Szczecin, which remained under Soviet administration.<ref name=Piskorski380381/> The Oder River was handed over to Polish administration in September 1946, followed by the port between February 1946 and May 1954.<ref name=Piskorski380381/> | |||

| ==Transportation== | |||

| There is a popular public transit system operating throughout Szczecin including a bus network and electric trams. | |||

| ==== Post-war ==== | |||

| The ] motorway (recently upgraded) serves as the southern bypass of the city, and connects to the German ] autobahn (portions of which are currently undergoing upgrade), from where one can reach Berlin in about 90 minutes (about 150 km). Road connections with the rest of Poland are of lower quality (no motorways), though the ] that is currently under construction will begin to improve the situation after its stretch from Szczecin to ] is opened around 2010. Construction of Express Roads ] and ] which are to run east from Szczecin has also started, though these roads will not be fully completed until about 2015. | |||

| ]: the pre-war Poles in Szczecin, the Poles who rebuilt the city after ], and the modern generation]] | |||

| While in 1945 the number of pre-war inhabitants dropped to 57,215 on 31 October 1945, the ] started on 22 February 1946 and continued until late 1947, in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement. In December 1946 about 17,000 German inhabitants remained, while the number of Poles living in the city reached 100,000.<ref name=Dok/> To ease the tensions between settlers from different regions, and help overcome fear caused by the continued presence of the Soviet troops, a special event was organised in April 1946 with 50,000 visitors in the partly destroyed city centre.<ref name=mcnamara3>{{cite book|last=McNamara|first=Paul|chapter=Competing National and Regional Identities in Poland's Baltic|title=History of Communism in Europe|volume=3|year=2012|isbn=9786068266275|pages=30–31; p. 31 |others=Bogdan C. Iacob |publisher=Zeta Books |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=70ECBQAAQBAJ}}</ref> Settlers from Central Poland made up about 70% of Szczecin's new population.<ref name=musekamp20>{{cite book|last=Musekamp|first=Jan|chapter=Der Königsplatz in Stettin als Beispiel kultureller Aneignung nach 1945|title=Wiedergewonnene Geschichte. Zur Aneignung von Vergangenheit in den Zwischenräumen Mitteleuropas|volume=22|series=Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Polen-Instituts Darmstadt|editor1-first=Peter Oliver|editor1-last=Loew|editor2-first=Christian|editor2-last=Pletzing|editor3-first=Thomas|editor3-last=Serrier|publisher=Harrassowitz Verlag|year=2006|isbn=3-447-05297-X|language=de|pages=19–35; p. 20}}</ref> In addition to Poles, Ukrainians from ] settled there.<ref name=musekamp20/> Also Poles repatriated from ], ] and ], ], settled in Szczecin in the following years.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://szczecin.tvp.pl/42971441/wyjatkowa-wystawa-o-historii-w-chinskiej-mandzurii-i-jej-finale-w-szczecinie|title=Wyjątkowa wystawa o historii w chińskiej Mandżurii i jej finale w Szczecinie|website=TVP3 Szczecin|author=Przemysław Plecan|access-date=15 May 2021|language=pl}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Kubasiewicz|first=Izabela|editor-last1=Dworaczek|editor-first1=Kamil|editor-last2=Kamiński|editor-first2=Łukasz|year=2013|title=Letnia Szkoła Historii Najnowszej 2012. Referaty|language=pl|location=Warszawa|publisher=]|pages=117–118|chapter=Emigranci z Grecji w Polsce Ludowej. Wybrane aspekty z życia mniejszości}}</ref> In 1945 and 1946, the city was the starting point of the northern route used by the Jewish underground organisation ] to channel Jewish ]s from ] to the ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Königseder|first=Angelika|chapter=Durchgangsstation Berlin. Jüdische Displaced Persons 1945–1948|title=Überlebt und unterwegs. Jüdische Displaced Persons im Nachkriegsdeutschland|editor-last=Giere|editor-first=Jacqueline|publisher=Campus Verlag|year=1997|isbn=3-593-35843-3|language=de|pages=189–206; pp. 191–192|display-editors=etal}}</ref> | |||

| Szczecin has good railway connections with the rest of Poland, but it is connected by only two single track, non-electrified lines with Germany to the west (high quality double-track lines were degraded after 1945). Because of this, the rail connection between Berlin and Szczecin is much slower and less convenient than one would expect between two European cities of that size and proximity. | |||

| Szczecin was rebuilt, and the city's industry was expanded. At the same time, Szczecin became a major Polish industrial centre and an important seaport (particularly for ]n coal) for Poland, ] and ]. Cultural expansion was accompanied by a campaign resulting in the "removal of all German traces".<ref name=musekamp2223>{{cite book|last=Musekamp|first=Jan|chapter=Der Königsplatz in Stettin als Beispiel kultureller Aneignung nach 1945|title=Wiedergewonnene Geschichte. Zur Aneignung von Vergangenheit in den Zwischenräumen Mitteleuropas|volume=22|series=Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Polen-Instituts Darmstadt|editor1-first=Peter Oliver|editor1-last=Loew|editor2-first=Christian|editor2-last=Pletzing|editor3-first=Thomas|editor3-last=Serrier|publisher=Harrassowitz Verlag|year=2006|isbn=3-447-05297-X|language=de|pages=19–35; pp. 22–23}}</ref> In 1946, ] prominently mentioned the city in his ] speech: "From Stettin in the Baltic to ] in the ] an iron curtain has descended across the Continent".<ref>British Information Services </ref><ref>Peter H. Merkl, '''', Penn State Press, 2004, p.{{nbsp}}338</ref> | |||

| Szczecin is served by ] which is 45 km northeast of the city. | |||

| ] workers' strike against the ] in Poland, August 1980]] | |||

| ==Culture== | |||

| Major cultural events in Szczecin are: | |||

| * Days of the Sea (Polish ''Dni Morza'') held every June. | |||

| * Street Artists' Festival (Polish ''Festiwal Artystów Ulicy'') held every July. | |||

| * Days of The Ukrainian Culture (Polish ''Dni Kultury Ukraińskiej'') held every May. | |||

| * Air show on Dabie airport held every May. | |||