| Revision as of 22:57, 18 September 2009 view sourceCambridgeBayWeather (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators253,295 edits Tidy← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:40, 3 January 2025 view source Orenburg1 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users166,087 editsm sp | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Subspecies of carnivore}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | |||

| {{Redirect2|White wolf|Polar wolf|other uses|White Wolf (disambiguation)|the prison in Russia|FKU IK-3, Kharp}} | |||

| | name = Arctic Wolf | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| | image = Polarwolf004.jpg | |||

| {{Use Canadian English|date=January 2020}} | |||

| | regnum = ]ia | |||

| {{Subspeciesbox | |||

| | phylum = ] | |||

| | |

| name = Arctic wolf | ||

| ⚫ | | image = Canis lupus arctos qtl1.jpg | ||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| | image_caption = | |||

| | familia = ] | |||

| | |

| status = DD | ||

| | status_system = COSEWIC | |||

| ⚫ | | species = |

||

| | status_ref = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/publications/canadian-wildlife-species-risk-2021.html |title=Canadian Wildlife Species at Risk 2021|access-date=2023-10-14|date=2021-12-03}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.741211/Canis_lupus_arctos|title=Canis lupus arctos|access-date=2023-10-14}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | | subspecies = |

||

| | |

| genus = Canis | ||

| | species_link = Gray wolf | |||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| ⚫ | | species = lupus | ||

| | range_map = arcticwolf distribution.gif | |||

| ⚫ | | subspecies = arctos | ||

| | range_map_caption = Arctic Wolf ranges | |||

| ⚫ | | authority = ], 1935 | ||

| | range_map = North American gray wolf subspecies distribution according to Goldman (1944) & MSW3 (2005).png | |||

| | range_map_caption = Historical and present range of ] in North America | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Arctic Wolf''' (''Canis lupus arctos''), also called '''Polar Wolf''' or '''White Wolf''', is a ] of the ] family, and a ] of the ]. Arctic Wolves inhabit the ] ] and the northern parts of ]. | |||

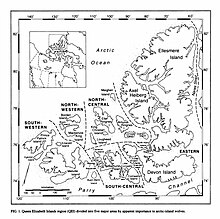

| The '''Arctic wolf''' ('''''Canis lupus arctos'''''), also known as the '''white wolf''', '''polar wolf''', and the '''Arctic grey wolf''', is a ] native to the ] of Canada's ], from ] to ].<ref>Mech, L. David (1981), ''The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species'', University of Minnesota Press, p. 352, {{ISBN|0-8166-1026-6}}</ref><ref name="ecoregions.appspot.com">{{Cite web|url=https://ecoregions.appspot.com/|title=Ecoregions 2017 ©|website=ecoregions.appspot.com}}</ref> Unlike some populations that move between tundra and forest regions,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.enr.gov.nt.ca/en/services/wolves|title = Wolves}}</ref> Arctic wolves spend their entire lives north of the northern ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.coolantarctica.com/Antarctica%20fact%20file/wildlife/Arctic_animals/arctic_wolf.php|title=Arctic Wolf Facts and Adaptations - Canis lupus arctos}}</ref> Their distribution to south is limited to the northern fringes of the ] on the southern half of ] and ].<ref name="ecoregions.appspot.com"/> It is a medium-sized subspecies, distinguished from the ] by its smaller size, its whiter colouration, its narrower ],<ref name=goldman>Goldman, E. A. (1964). Classification of wolves. In ''The Wolves of North America'' Part 2. Young, S. P. & Goldman, E. A. (Eds.) New York: Dover Publs. p. 430.</ref> and larger ]s.<ref name=brock>{{cite journal | last1 = Clutton-Brock | first1 = J. | last2 = Kitchener | first2 = A. C. | last3 = Lynch | first3 = J. M. | year = 1994 | title = Changes in the skull morphology of the Arctic wolf, ''Canis lupus arctos'', during the twentieth century | journal = Journal of Zoology | volume = 233 | pages = 19–36 | doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb05259.x}}</ref> Since 1930, there has been a progressive reduction in size in Arctic wolf skulls, which is likely the result of ].<ref name="brock" /> | |||

| ==Anatomy== | |||

| ''See also: ] | |||

| ==Taxonomy== | |||

| Though the same species as a Grey Wolf, Arctic Wolves generally are smaller than the "Forest Gray Wolves" (Arctic Wolves are sometimes called "]"), being about {{convert|3|to|6|ft|abbr=on}} long including the tail; males are larger than females and are more aggressive. Their shoulder heights vary from {{convert|25|to|31|in|cm|abbr=on}}, their ears are smaller to trap body heat and their muzzles are much shorter. Often weighing over {{convert|100|lb|abbr=on}}, weights of up to {{convert|175|lb|abbr=on}} have been observed in full-grown males. During the winter, the Arctic Wolf grows a second layer of fur for protection during the harsh conditions that may occur during the season. Wolves have very similar characteristics to a ], although wolves have longer legs, larger feet, a longer tail and slightly wider heads.<ref name="traits"></ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1935, the British zoologist ] attributed the subspecies name ''Canis lupus arctos'' (Arctic wolf) to a specimen from Melville Island in the ], Canada. He wrote that similar wolves could be found on Ellesmere Island. He also attributed the name ''Canis lupus orion'' to a ] specimen from ], northwest Greenland.<ref name=pocock1935/> Both wolves are recognized as separate subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' in the taxonomic authority '']'' (2005).<ref name=wozencraft2005/> | |||

| == Behaviors== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=September 2009|see talk page}} | |||

| The Arctic Wolf is able to withstand sub-zero temperatures for years. They can also survive up to five months of absolute darkness a year, and can live weeks without food. The Arctic Wolf is one of the few mammals that can withstand the conditions of weather. Arctic Wolves usually travel in small packs as small as two and as large as twenty. | |||

| A study by Chambers ''et al''. (2012) using ] ] DNA and ] data indicate that the Arctic wolf has no unique ]s which suggests that its colonization of the Arctic Archipelago from the North American mainland was relatively recent, and thus not sufficient to warrant subspecies status.<ref name=Chambers>{{cite journal |title=An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses |vauthors=Chambers SM, Fain SR, Fazio B, Amaral M |year=2012 |journal=North American Fauna |volume=77 |pages=1–67|doi=10.3996/nafa.77.0001|doi-access=free }}</ref> During a meeting assembled in 2014 by the ] of the ], one speaker, Robert K. Wayne, mentioned he disagreed with the conclusion that a subspecies had to be genetically distinct, believing that different subspecies could slowly grade into each other - suggesting that although it was impossible to determine if an individual wolf was one subspecies or the next using DNA, the population of Arctic wolves as a whole could be distinguished by the looking at the proportions of ]s (SNP): i.e. Arctic wolves could be distinguished by having three wolves in the putative population with a specific SNP, whereas another subspecies could be distinguished by having 20 wolves with that SNP. Wayne furthermore stated that he believed the ] in which the wolf happened to be found was a good enough characteristic to distinguish a subspecies.<ref> p. 47</ref> | |||

| When the female wolf is pregnant, she will leave the pack in order to dig herself a den to raise her pups. Although, if the layer of ice is too thick, she will move to a den or cave. The pups are born both blind and deaf, weighing at one pound. They are dependent on their mother for food and protection. There can be 3-12 puppies in a litter. When they are three weeks old, they are allowed outside of the den. Some other wolves in the pack might take care of the mother’s pups until she arrives back with food.<ref></ref> | |||

| == |

==Behaviour== | ||

| The Arctic wolf is relatively unafraid of people, and can be coaxed to approach people in some areas.<ref name=mech2007>Mech, L. D., , '']'', May 30, 2007</ref> The wolves on Ellesmere Island do not fear humans, which is thought to be due to them seeing humans so little, and they will approach humans cautiously and curiously.<ref> by Laura DeLallo. Bearport Publishing, New York 2011</ref><ref> by Michael Becker. BBC Two, 2014.</ref><ref> by Henry Beston 2006. International Wolf Centre.</ref><ref> by L. David Mech. National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, Pacific Marine Environment Laboratory, Arctic Zone. 2004</ref> ] wrote that during the ], a pair of wolves shadowed one of his teammates, who kept them at a distance by waving his ski pole.<ref name=sverdrup>Sverdrup, O. N., (1918), '''', Vol. I, London Longmans, Green, pp. 431–432</ref> In 1977, a pair of scientists were approached by six wolves on Ellesmere Island, with one animal leaping at one of the scientists and grazing a cheek. A number of incidents involving aggressive wolves have occurred in ], where the wolves have lived in close proximity to the local weather station for decades and became habituated to humans. One of these wolves attacked 3 people, was shot, and tested positive for rabies.<ref>Linnell, J.D.C., et al. (2002). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200802021922/https://www.wwf.de/fileadmin/fm-wwf/Publikationen-PDF/2002.Review.wolf.attacks.pdf |date=2020-08-02 }}, NINA, pp. 29–31, {{ISBN|82-426-1292-7}}</ref> | |||

| The Arctic Wolf inhabits the northern part of Greenland, the Canadian ] as well as some parts of Alaska. | |||

| ] | |||

| Very little is known about the movement of the Arctic wolves, mainly due to climate. The only time at which the wolf migrates is during the wintertime when there is complete darkness for 24 hours. This makes Arctic wolf movement hard to research. About {{convert|2,250|km|abbr=on}} south of the High Arctic, a wolf movement study took place in the wintertime in complete darkness, when the temperature was as low as {{convert|-53|C}}. The researchers found that wolves prey mainly on the ]en. There is no available information of the wolves' movements where the muskoxen were.<ref name=":1">{{cite journal |title=Movements Of Wolves At The Northern Extreme Of The Species' Range, Including During Four Months Of Darkness |last=Mech |first=David |date=2011 |journal=PLOS ONE |doi= 10.1371/journal.pone.0025328|pmid= 21991308|pmc=3186767 |volume=6 |issue=10 |pages=e25328|bibcode=2011PLoSO...625328M |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| == |

== Diet == | ||

| In the wild, Arctic wolves primarily prey on ]en and ]s. They have also been found to prey on ]s, ], ]es, birds, and beetles. It has been also found that Arctic wolves scavenge through garbage. This sort of food source will not always be found in the Arctic wolf's diet because of regional and seasonal availability.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Marquard|first=Peterson|date=1998|title=Food Habits of Arctic Wolves in Greenland|journal=Journal of Mammalogy|volume=79|issue=1|pages=236–244|doi=10.2307/1382859|jstor=1382859|doi-access=free}}<!--|access-date = October 30, 2015--></ref> Sometimes there is debate whether the muskox or the Arctic hare is the primary prey for the hare-wolf-muskox predator-prey system. Studies provide evidence that the muskoxen are indeed their primary prey because wolf presence and reproduction seems to be higher when muskox is more available than higher hare availability.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Decline and Recovery of a High Arctic Wolf-Prey System|last = Mech|first = David|date = September 1, 2005|journal = Arctic|doi = 10.14430/arctic432|volume = 58|issue = 3|doi-access = free}}</ref> More supporting evidence suggests that muskoxen provide long-term viability and other ungulates do not appear in the wolf's diet.<ref name=":3">{{cite journal |title=Decline and Extermination of an Arctic Wolf Population in East Greenland |last=Marquard-Petersen |first=Ulf |date=2012 |journal=Arctic |doi= 10.14430/arctic4197|volume=65|issue=2 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Evidence suggesting that Arctic wolves depend more on hares claims that the mature wolf population paralleled the increase of hares rather than muskoxen availability.<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|title = Annual Arctic Wolf Pack Size Related to Arctic Hare Numbers|last = Mech|first = David|date = September 1, 2007|journal = Arctic|doi = 10.14430/arctic222|volume=60|issue = 3|url = https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/386|doi-access = free}}</ref> The study goes on to say that degree of reliance between the two sources of food is uncertain and that the amount of consumption between the two species depends on the season and year.<ref name=":4" /> Debate continues when seasonal and diet of young wolves is discussed. According to one study, muskox calves serve as a primary food source because the needs of pups are greater<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Abundance, social organization, and population trend of the arctic wolf in north and east greenland during 1978–1998|last = Marquard|first = Peterson|journal = Canadian Journal of Zoology |date=October 2009 |issue=10 |doi = 10.1139/z09-078|volume=87|pages=895–901}}</ref> but another study suggests that "when hares were much more plentiful (Mech, 2000), wolves commonly fed them to their pups during summer."<ref name=":4" /> These differences may be attributed to location as well. ]s are rarely encountered by wolves, though there are two records of wolf packs killing polar bear cubs.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic59-3-322.pdf|title=Wolf (Canis lupus) Predation of a Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus) Cub on the Sea Ice off Northwestern Banks Island, Northwest Territories, Canada|journal=Arctic|volume=59|issue=3|year=2006|pages=322–324|access-date=March 16, 2010|doi=10.14430/arctic318|last1=Richardson|first1=E.S|last2=Andriashek|first2=D|archive-date=August 8, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170808142212/http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic59-3-322.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Wolfs have forty-two teeth when they are adults, which is their main use of attack when they are hunting.<ref name="traits"/> They eat all of their prey, including the bones. They also, like all wolves, hunt in packs and they mostly prey on ] and ]en, but will also kill a number of ]s, ], ] and ]s, as well as other smaller animals such as ].<ref>{{cite web|last=Morelle|first=Rebecca|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/7213731.stm|title=Elusive wolves caught on camera|publisher=BBC|date=2009-01-31|accessdate=2008-01-31}}</ref> Due to the scarcity of prey, they roam large areas to find prey up to and beyond {{convert|2600|km2|abbr=on}}, and they will follow migrating caribou south during the winter. Wolves generally do not get involved in long chases, and usually stop chasing their prey after {{convert|10|-|180|m|abbr=on}} of running. Although, a wolf pack may sometimes travel up to {{convert|800|mi|abbr=on}} when searching for their prey. When the temperature drops too low, the pack will turn toward the migrating animals and head south. Arctic Wolves live in small family groups, that have a breeding pair (]), their cubs as well as their offspring. All the wolves in the pack entrust in the Alpha male and the female. The pack works together when it comes to feeding, and caring for their cubs. Some lone Arctic Wolves are young males that left their pack to search for their own territories. They try to avoid other wolves, unless they are able to mate. When a wolf is able to find an abandoned territory, it will claim it as its own by marking the territory with its scent. After doing so, the lone wolf will gather other lone Arctic Wolves into its territory.<ref></ref> | |||

| == |

==Conservation== | ||

| The Arctic wolf is ], but it does face threats. In 1997, there was a decline in the Arctic wolf population and its prey, muskoxen ('']''), and ]s (''Lepus arcticus''). This was due to unfavourable weather conditions during the summers for four years. Arctic wolf populations recovered the next summer when weather conditions returned to normal.<ref name=":5">{{cite journal |jstor=40512716 |title=Decline and Recovery of a High Arctic Wolf-Prey System |last=Mech |first=David. L |date=2005 |journal=Arctic |doi= 10.14430/arctic432|volume=58|issue=3 |pages=305–307 |url=https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1385&context=usgsnpwrc |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| :''See also: ] | |||

| Due to the Arctic's ] soil and the difficulty it poses for digging dens, Arctic Wolves often use rock outcroppings, caves or even shallow depressions as dens instead; the mother gives birth to two or three pups in late May to early June, about a month later than Gray Wolves. It is generally thought that the lower number of pups compared to the average of four to five among Gray Wolves is due to the scarcity of prey in the Arctic. They give birth in about 63 days to 75 days. At birth, wolf pups weigh about one pound. When they are three weeks old, they are allowed outside of the den. Some other wolves in the pack might take care of the mother’s pups until she arrives back with food. | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{Reflist|colwidth=30em|refs= | |||

| The Arctic Wolf is the only subspecies of the Gray Wolf that still can be found over the whole of its original range, largely because, in their natural habitat, they rarely encounter humans. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| <ref name=pocock1935>{{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1096-3642.1935.tb01687.x|title=The Races of Canis lupus|journal=Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London|volume=105|issue=3|pages=647–686|year=1935|last1=Pocock|first1=R. I}}</ref> | |||

| == References == | |||

| ⚫ | * L. David Mech (text), Jim Brandenburg (photos) |

||

| ⚫ | * L. David Mech |

||

| <ref name=wozencraft2005>{{MSW3 Wozencraft|id=14000751|pages=575–577}} url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA576</ref><!--Note: the url must be kept outside of the MSW3 template for the link to arrive on the correct page--> | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| ⚫ | * L. David Mech (text), Jim Brandenburg (photos) (May 1987). ''At Home With the Arctic Wolf.'' ] 171(5):562–593. | ||

| ⚫ | * L. David Mech (1997). '''', Voyageur Press, {{ISBN|0-89658-353-8}} . | ||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| {{ |

{{Wikispecies|Canis lupus arctos}} | ||

| {{ |

{{Commons category|Canis lupus arctos}} | ||

| *{{cite web|title=Workers in rural Canada were amazed when these wild arctic wolves approached them at their work yard|website = ]| date=27 September 2016 |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O3-K2HK2qU0 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211222/O3-K2HK2qU0 |archive-date=2021-12-22 |url-status=live}}{{cbignore}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Canidae extinct nav|W.}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| {{grey wolf subspecies}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| {{Taxonbar|from=Q216441}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:40, 3 January 2025

Subspecies of carnivore "White wolf" and "Polar wolf" redirect here. For other uses, see White Wolf (disambiguation). For the prison in Russia, see FKU IK-3, Kharp.

| Arctic wolf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

Data Deficient (COSEWIC) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lupus |

| Subspecies: | C. l. arctos |

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus arctos Pocock, 1935 | |

| |

| Historical and present range of grey wolf subspecies in North America | |

The Arctic wolf (Canis lupus arctos), also known as the white wolf, polar wolf, and the Arctic grey wolf, is a subspecies of grey wolf native to the High Arctic tundra of Canada's Queen Elizabeth Islands, from Melville Island to Ellesmere Island. Unlike some populations that move between tundra and forest regions, Arctic wolves spend their entire lives north of the northern treeline. Their distribution to south is limited to the northern fringes of the Middle Arctic tundra on the southern half of Prince of Wales and Somerset Islands. It is a medium-sized subspecies, distinguished from the northwestern wolf by its smaller size, its whiter colouration, its narrower braincase, and larger carnassials. Since 1930, there has been a progressive reduction in size in Arctic wolf skulls, which is likely the result of wolf-dog hybridization.

Taxonomy

In 1935, the British zoologist Reginald Pocock attributed the subspecies name Canis lupus arctos (Arctic wolf) to a specimen from Melville Island in the Queen Elizabeth Islands, Canada. He wrote that similar wolves could be found on Ellesmere Island. He also attributed the name Canis lupus orion to a Greenland wolf specimen from Cape York, northwest Greenland. Both wolves are recognized as separate subspecies of Canis lupus in the taxonomic authority Mammal Species of the World (2005).

A study by Chambers et al. (2012) using autosomal microsatellite DNA and Mitochondrial DNA data indicate that the Arctic wolf has no unique haplotypes which suggests that its colonization of the Arctic Archipelago from the North American mainland was relatively recent, and thus not sufficient to warrant subspecies status. During a meeting assembled in 2014 by the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, one speaker, Robert K. Wayne, mentioned he disagreed with the conclusion that a subspecies had to be genetically distinct, believing that different subspecies could slowly grade into each other - suggesting that although it was impossible to determine if an individual wolf was one subspecies or the next using DNA, the population of Arctic wolves as a whole could be distinguished by the looking at the proportions of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP): i.e. Arctic wolves could be distinguished by having three wolves in the putative population with a specific SNP, whereas another subspecies could be distinguished by having 20 wolves with that SNP. Wayne furthermore stated that he believed the habitat in which the wolf happened to be found was a good enough characteristic to distinguish a subspecies.

Behaviour

The Arctic wolf is relatively unafraid of people, and can be coaxed to approach people in some areas. The wolves on Ellesmere Island do not fear humans, which is thought to be due to them seeing humans so little, and they will approach humans cautiously and curiously. Otto Sverdrup wrote that during the Fram expedition, a pair of wolves shadowed one of his teammates, who kept them at a distance by waving his ski pole. In 1977, a pair of scientists were approached by six wolves on Ellesmere Island, with one animal leaping at one of the scientists and grazing a cheek. A number of incidents involving aggressive wolves have occurred in Alert, Nunavut, where the wolves have lived in close proximity to the local weather station for decades and became habituated to humans. One of these wolves attacked 3 people, was shot, and tested positive for rabies.

Very little is known about the movement of the Arctic wolves, mainly due to climate. The only time at which the wolf migrates is during the wintertime when there is complete darkness for 24 hours. This makes Arctic wolf movement hard to research. About 2,250 km (1,400 mi) south of the High Arctic, a wolf movement study took place in the wintertime in complete darkness, when the temperature was as low as −53 °C (−63 °F). The researchers found that wolves prey mainly on the muskoxen. There is no available information of the wolves' movements where the muskoxen were.

Diet

In the wild, Arctic wolves primarily prey on muskoxen and Arctic hares. They have also been found to prey on lemmings, caribou, Arctic foxes, birds, and beetles. It has been also found that Arctic wolves scavenge through garbage. This sort of food source will not always be found in the Arctic wolf's diet because of regional and seasonal availability. Sometimes there is debate whether the muskox or the Arctic hare is the primary prey for the hare-wolf-muskox predator-prey system. Studies provide evidence that the muskoxen are indeed their primary prey because wolf presence and reproduction seems to be higher when muskox is more available than higher hare availability. More supporting evidence suggests that muskoxen provide long-term viability and other ungulates do not appear in the wolf's diet. Evidence suggesting that Arctic wolves depend more on hares claims that the mature wolf population paralleled the increase of hares rather than muskoxen availability. The study goes on to say that degree of reliance between the two sources of food is uncertain and that the amount of consumption between the two species depends on the season and year. Debate continues when seasonal and diet of young wolves is discussed. According to one study, muskox calves serve as a primary food source because the needs of pups are greater but another study suggests that "when hares were much more plentiful (Mech, 2000), wolves commonly fed them to their pups during summer." These differences may be attributed to location as well. Polar bears are rarely encountered by wolves, though there are two records of wolf packs killing polar bear cubs.

Conservation

The Arctic wolf is least concern, but it does face threats. In 1997, there was a decline in the Arctic wolf population and its prey, muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus), and Arctic hares (Lepus arcticus). This was due to unfavourable weather conditions during the summers for four years. Arctic wolf populations recovered the next summer when weather conditions returned to normal.

References

- "Canadian Wildlife Species at Risk 2021". 2021-12-03. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- "Canis lupus arctos". Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- Mech, L. David (1981), The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species, University of Minnesota Press, p. 352, ISBN 0-8166-1026-6

- ^ "Ecoregions 2017 ©". ecoregions.appspot.com.

- "Wolves".

- "Arctic Wolf Facts and Adaptations - Canis lupus arctos".

- Goldman, E. A. (1964). Classification of wolves. In The Wolves of North America Part 2. Young, S. P. & Goldman, E. A. (Eds.) New York: Dover Publs. p. 430.

- ^ Clutton-Brock, J.; Kitchener, A. C.; Lynch, J. M. (1994). "Changes in the skull morphology of the Arctic wolf, Canis lupus arctos, during the twentieth century". Journal of Zoology. 233: 19–36. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb05259.x.

- Miller, Frank (1995). "Wolf-sightings on the Canadian Arctic Islands". Arctic. 48 (4). doi:10.14430/arctic1253.

- Walton, Lyle (2001). "Movement Patterns of Barren-Ground Wolves in the Central Canadian Arctic". Journal of Mammalogy. 82 (3): 867–876. doi:10.1093/jmammal/82.3.867.

- Pocock, R. I (1935). "The Races of Canis lupus". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 105 (3): 647–686. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1935.tb01687.x.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA576

- Chambers SM, Fain SR, Fazio B, Amaral M (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna. 77: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- Review of Proposed Rule Regarding Status of the Wolf Under the Endangered Species Act p. 47

- Mech, L. D., Arctic Wolves and Their Prey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, May 30, 2007

- Arctic Wolf: The High Arctic by Laura DeLallo. Bearport Publishing, New York 2011

- Arctic wildlife in a warming world by Michael Becker. BBC Two, 2014.

- Ellesmere Island Journal & Field Notes by Henry Beston 2006. International Wolf Centre.

- Arctic Wolves and Their Prey by L. David Mech. National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, Pacific Marine Environment Laboratory, Arctic Zone. 2004

- Sverdrup, O. N., (1918), New land; four years in the Arctic regions, Vol. I, London Longmans, Green, pp. 431–432

- Linnell, J.D.C., et al. (2002). Archived 2020-08-02 at the Wayback Machine, NINA, pp. 29–31, ISBN 82-426-1292-7

- Mech, David (2011). "Movements Of Wolves At The Northern Extreme Of The Species' Range, Including During Four Months Of Darkness". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25328. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625328M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025328. PMC 3186767. PMID 21991308.

- Marquard, Peterson (1998). "Food Habits of Arctic Wolves in Greenland". Journal of Mammalogy. 79 (1): 236–244. doi:10.2307/1382859. JSTOR 1382859.

- Mech, David (September 1, 2005). "Decline and Recovery of a High Arctic Wolf-Prey System". Arctic. 58 (3). doi:10.14430/arctic432.

- Marquard-Petersen, Ulf (2012). "Decline and Extermination of an Arctic Wolf Population in East Greenland". Arctic. 65 (2). doi:10.14430/arctic4197.

- ^ Mech, David (September 1, 2007). "Annual Arctic Wolf Pack Size Related to Arctic Hare Numbers". Arctic. 60 (3). doi:10.14430/arctic222.

- Marquard, Peterson (October 2009). "Abundance, social organization, and population trend of the arctic wolf in north and east greenland during 1978–1998". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 87 (10): 895–901. doi:10.1139/z09-078.

- Richardson, E.S; Andriashek, D (2006). "Wolf (Canis lupus) Predation of a Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus) Cub on the Sea Ice off Northwestern Banks Island, Northwest Territories, Canada" (PDF). Arctic. 59 (3): 322–324. doi:10.14430/arctic318. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- Mech, David. L (2005). "Decline and Recovery of a High Arctic Wolf-Prey System". Arctic. 58 (3): 305–307. doi:10.14430/arctic432. JSTOR 40512716.

Further reading

- L. David Mech (text), Jim Brandenburg (photos) (May 1987). At Home With the Arctic Wolf. National Geographic 171(5):562–593.

- L. David Mech (1997). The Arctic Wolf: 10 Years With the Pack, Voyageur Press, ISBN 0-89658-353-8 .

External links

- "Workers in rural Canada were amazed when these wild arctic wolves approached them at their work yard". YouTube. 27 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-12-22.

| Extant gray wolf subspecies | |

|---|---|

| Old World subspecies | |

| New World subspecies |

|

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Canis lupus arctos | |