| Revision as of 18:08, 22 December 2005 view sourceVsmith (talk | contribs)Administrators272,841 editsm Reverted edits by 168.229.180.165 (talk) to last version by Jredmond← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:27, 16 September 2024 view source Hydrogen astatide (talk | contribs)248 edits →Isotopes | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{About|the chemical element}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_header | number=1 | symbol=H | name=hydrogen | left=- | right=] | above=- | below=] | color1=#a0ffa0 | color2=green }} | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_series | ]s }} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2022}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_groupperiodblock | group=1 | period=1 | block=s }} | |||

| {{Infobox hydrogen}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_appearance_img | H,1| colorless }} | |||

| '''Hydrogen''' is a ]; it has ] '''H''' and ] 1. It is the lightest element and, at ], is a ] of ]s with the ] {{chem2|H2}}, sometimes called '''dihydrogen'''<!--] is a redirect to hydrogen also called '''diprotium'''-->,<ref>{{cite web |title=Dihydrogen |url=http://www.usm.maine.edu/~newton/Chy251_253/Lectures/LewisStructures/Dihydrogen.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090213174645/http://usm.maine.edu/~newton/Chy251_253/Lectures/LewisStructures/Dihydrogen.html |archive-date=13 February 2009 |access-date=6 April 2009 |work=O{{=}}CHem Directory |publisher=] |df=dmy-all}}</ref> but more commonly called '''hydrogen gas''', '''molecular hydrogen''' or simply hydrogen. It is colorless, odorless,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Hydrogen|url=https://www.britannica.com/science/hydrogen|url-status=live|access-date=25 December 2021|website=]|language=en|archive-date=24 December 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211224165150/https://www.britannica.com/science/hydrogen}}</ref> non-toxic, and highly ]. Constituting about 75% of all ] ], hydrogen is the ] chemical element in the ].<ref>{{cite web | |||

| {{Elementbox_atomicmass_gpm | ] }} | |||

| |last=Boyd | |||

| {{Elementbox_econfig | 1s<sup>1</sup> }} | |||

| |first=Padi | |||

| {{Elementbox_epershell | 1 }} | |||

| |title=What is the chemical composition of stars? | |||

| {{Elementbox_section_physicalprop | color1=#a0ffa0 | color2=green }} | |||

| |url=https://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/ask_astro/stars.html#961112a | |||

| {{Elementbox_phase | ] }} | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| {{Elementbox_density_gplstp | 0.08988 }} | |||

| |date=19 July 2014 | |||

| {{Elementbox_meltingpoint | k=14.01 | c=-259.14 | f=-434.45 }} | |||

| |access-date=5 February 2008 | |||

| {{Elementbox_boilingpoint | k=20.28 | c=-252.87 | f=-423.17 }} | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150115074556/http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/ask_astro/stars.html#961112a | |||

| |archive-date=15 January 2015 | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref><ref group=note>However, most of the universe's mass is not in the form of baryons or chemical elements. See ] and ].</ref> ], including the ], mainly consist of hydrogen in a ], while on Earth, hydrogen is found in ], ], as ], and in other ]s. The most common ] (protium, {{sup|1}}H) consists of one ], one ], and no ]s. | |||

| In the ], the formation of hydrogen's protons occurred in the first second after the ]; neutral hydrogen atoms only formed about 370,000 years later during the ] as the universe cooled and plasma had cooled enough for electrons to remain bound to protons.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Tanabashi |first=M. |display-authors=etal |year=2018 |journal=] |volume=98 |issue=3 |via=] at ] |url=http://pdg.lbl.gov/2018/reviews/rpp2018-rev-bbang-cosmology.pdf |page=358 |quote=Chapter 21.4.1 - This occurred when the age of the Universe was about 370,000 years. |title=Big-Bang Cosmology |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210629034426/https://pdg.lbl.gov/2018/reviews/rpp2018-rev-bbang-cosmology.pdf |archive-date=29 June 2021 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.98.030001 |doi-access=free }} (Revised September 2017) by ] and ].</ref> Hydrogen, typically ] except under ], readily forms ] with most nonmetals, contributing to the formation of compounds like water and various organic substances. Its role is crucial in ], which mainly involve proton exchange among soluble molecules. In ], hydrogen can take the form of either a negatively charged ], where it is known as ], or as a positively charged ], H{{sup|+}}. The cation, ] just a proton (symbol '''p'''), exhibits specific behavior in ]s and in ]s involves ] of its ] by surrounding ] molecules or anions. Hydrogen's unique position as the only neutral atom for which the ] can be directly solved, has significantly contributed to the foundational principles of ] through the exploration of its energetics and ].<ref name="Laursen04">{{cite web|last1=Laursen|first1=S.|last2=Chang|first2=J.|last3=Medlin|first3=W.|last4=Gürmen|first4=N.|last5=Fogler|first5=H. S.|title=An extremely brief introduction to computational quantum chemistry|url=http://www.umich.edu/~elements/5e/web_mod/quantum/introduction_3.htm|website=Molecular Modeling in Chemical Engineering|publisher=University of Michigan|access-date=4 May 2015|date=27 July 2004|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150520061846/http://www.umich.edu/~elements/5e/web_mod/quantum/introduction_3.htm|archive-date=20 May 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Hydrogen gas was first produced artificially in the early 16th century by reacting acids with metals. ], in 1766–81, identified hydrogen gas as a distinct substance<ref>{{Cite episode | |||

| |title = Discovering the Elements | |||

| |url = http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00q2mk5 | |||

| |series = Chemistry: A Volatile History | |||

| |credits = Presenter: Professor Jim Al-Khalili | |||

| |network = ] | |||

| |station = ] | |||

| |air-date = 21 January 2010 | |||

| |minutes = 25:40 | |||

| |access-date = 9 February 2010 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100125010949/http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00q2mk5 | |||

| |archive-date = 25 January 2010 | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> and discovered its property of producing water when burned; hence its name means "water-former" in Greek. | |||

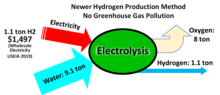

| Most ] occurs through ] of ]; a smaller portion comes from energy-intensive methods such as the ].<ref name="Dincer-2015">{{Cite journal|last1=Dincer|first1=Ibrahim|last2=Acar|first2=Canan|date=14 September 2015|title=Review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360319914034119|journal=International Journal of Hydrogen Energy|language=en|volume=40|issue=34|pages=11094–11111|doi=10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.12.035|bibcode=2015IJHE...4011094D |issn=0360-3199|access-date=4 February 2022|archive-date=15 February 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220215183915/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360319914034119|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | |||

| |title=Hydrogen Basics – Production | |||

| |url=http://www.fsec.ucf.edu/en/consumer/hydrogen/basics/production.htm | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |date=2007 | |||

| |access-date=5 February 2008 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080218210526/http://www.fsec.ucf.edu/en/consumer/hydrogen/basics/production.htm | |||

| |archive-date=18 February 2008 | |||

| }}</ref> Its main industrial uses include ] processing, such as ], and ], with emerging uses in ]s for electricity generation and as a heat source.<ref name="Lewis-2021">{{Cite journal |last=Lewis |first=Alastair C. |date=10 June 2021 |title=Optimising air quality co-benefits in a hydrogen economy: a case for hydrogen-specific standards for NO x emissions |journal=Environmental Science: Atmospheres |language=en |volume=1 |issue=5 |pages=201–207 |doi=10.1039/D1EA00037C|s2cid=236732702 |doi-access=free }}{{Creative Commons text attribution notice|cc=by3|url=|authors=|vrt=|from this source=yes}}</ref> When used in fuel cells, hydrogen's only emission at point of use is water vapor,<ref name="Lewis-2021" /> though combustion can produce ].<ref name="Lewis-2021" /> Hydrogen's interaction with metals may cause ].<ref name="Rogers 1999 1057–1064">{{cite journal |last=Rogers|first=H. C. |title=Hydrogen Embrittlement of Metals |journal=] |volume=159|issue=3819|pages=1057–1064 |date=1999 |doi=10.1126/science.159.3819.1057 |pmid=17775040 |bibcode=1968Sci...159.1057R |s2cid=19429952}}</ref> | |||

| {{Toclimit}} | |||

| == Properties == | |||

| === Combustion === | |||

| ] | |||

| ] burning hydrogen with oxygen, produces a nearly invisible flame at full thrust.|alt=A black inverted funnel with blue glow emerging from its opening.]] | |||

| Hydrogen gas is highly flammable: | |||

| :{{chem2|2 H2(g) + O2(g) → 2 H2O(l)}} (572 kJ/2 mol = 286 kJ/mol = 141.865 MJ/kg)<ref group="note">286 kJ/mol: energy per mole of the combustible material (molecular hydrogen).</ref> | |||

| ]: −286 kJ/mol.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |author=Committee on Alternatives and Strategies for Future Hydrogen Production and Use | |||

| |date=2004 | |||

| |title=The Hydrogen Economy: Opportunities, Costs, Barriers, and R&D Needs | |||

| |page=240 | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |isbn=978-0-309-09163-3 | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ugniowznToAC&pg=PA240 | |||

| |access-date=3 September 2020 | |||

| |archive-date=29 January 2021 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210129015745/https://books.google.com/books?id=ugniowznToAC&pg=PA240 | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Hydrogen gas forms explosive mixtures with air in concentrations from 4–74%<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Carcassi|first1=M. N. | |||

| |last2=Fineschi|first2=F. | |||

| |title=Deflagrations of H<sub>2</sub>–air and CH<sub>4</sub>–air lean mixtures in a vented multi-compartment environment | |||

| |journal=Energy | |||

| |volume=30|issue=8|pages=1439–1451 | |||

| |date=2005 | |||

| |doi=10.1016/j.energy.2004.02.012 | |||

| |bibcode=2005Ene....30.1439C | |||

| }}</ref> and with chlorine at 5–95%. The hydrogen ], the temperature of spontaneous ignition in air, is {{convert|500|C|F}}.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-CRRJBVv5d0C&pg=PA402 | |||

| |page=402 | |||

| |title=A Comprehensive Guide to the Hazardous Properties of Chemical Substances | |||

| |publisher=Wiley-Interscience | |||

| |isbn=978-0-471-71458-3 | |||

| |date=2007 | |||

| |last=Patnaik | |||

| |first=P. | |||

| |access-date=3 September 2020 | |||

| |archive-date=26 January 2021 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210126131413/https://books.google.com/books?id=-CRRJBVv5d0C&pg=PA402 | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==== Flame ==== | |||

| Pure ] flames emit ] light and with high oxygen mix are nearly invisible to the naked eye, as illustrated by the faint plume of the ], compared to the highly visible plume of a ], which uses an ]. The detection of a burning hydrogen leak, may require a ]; such leaks can be very dangerous. Hydrogen flames in other conditions are blue, resembling blue natural gas flames.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Visible emission of hydrogen flames|last1=Schefer|first1=E. W.|last2=Kulatilaka|first2=W. D.|last3=Patterson|first3=B. D.|last4=Settersten|first4=T. B.|date=June 2009|journal=Combustion and Flame|volume=156|issue=6|pages=1234–1241|doi=10.1016/j.combustflame.2009.01.011|bibcode=2009CoFl..156.1234S |url=https://zenodo.org/record/1258847|access-date=30 June 2019|archive-date=29 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210129015717/https://zenodo.org/record/1258847|url-status=live}}</ref> The ] was a notorious example of hydrogen combustion and the cause is still debated. The visible flames in the photographs were the result of carbon compounds in the airship skin burning.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Myths about the Hindenburg Crash|url=https://www.airships.net/hindenburg/disaster/myths/|access-date=29 March 2021|website=Airships.net|language=en-US|archive-date=20 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210420055020/https://www.airships.net/hindenburg/disaster/myths/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Reactants ==== | |||

| {{chem2|H2}} is unreactive compared to diatomic elements such as ] or oxygen. The thermodynamic basis of this low reactivity is the very strong H–H bond, with a ] of 435.7 kJ/mol.<ref>{{RubberBible87th}}</ref> The kinetic basis of the low reactivity is the nonpolar nature of {{chem2|H2}} and its weak polarizability. It spontaneously reacts with ] and ] to form ] and ], respectively.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |last=Clayton|first=D. D. | |||

| |title=Handbook of Isotopes in the Cosmos: Hydrogen to Gallium | |||

| |date=2003 | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |isbn=978-0-521-82381-4 | |||

| }}</ref> The reactivity of {{chem2|H2}} is strongly affected by the presence of metal catalysts. Thus, while mixtures of {{chem2|H2}} with {{chem2|O2}} or air combust readily when heated to at least 500°C by a spark or flame, they do not react at room temperature in the absence of a catalyst. | |||

| === Electron energy levels === | |||

| {{Main|Hydrogen atom}} | |||

| ] radius (image not to scale)|alt=Drawing of a light-gray large sphere with a cut off quarter and a black small sphere and numbers 1.7×10{{sup|−5}} illustrating their relative diameters.]] | |||

| The ] ] of the electron in a hydrogen atom is −13.6 ],<ref>{{cite web|author1=NAAP Labs|title=Energy Levels|url=http://astro.unl.edu/naap/hydrogen/levels.html|publisher=University of Nebraska Lincoln|access-date=20 May 2015|date=2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150511120536/http://astro.unl.edu/naap/hydrogen/levels.html|archive-date=11 May 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> equivalent to an ] ] of roughly 91 nm wavelength.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=photon+wavelength+13.6+ev|title=photon wavelength 13.6 eV|access-date=20 May 2015|date=20 May 2015|work=Wolfram Alpha|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160512221720/http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=photon+wavelength+13.6+ev|archive-date=12 May 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The energy levels of hydrogen can be calculated fairly accurately using the ] of the atom, in which the electron "orbits" the proton, like how Earth orbits the Sun. However, the electron and proton are held together by electrostatic attraction, while planets and celestial objects are held by ]. Due to the discretization of ] postulated in early ] by Bohr, the electron in the Bohr model can only occupy certain allowed distances from the proton, and therefore only certain allowed energies.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |last=Stern | |||

| |first=D. P. | |||

| |date=16 May 2005 | |||

| |url=http://www.iki.rssi.ru/mirrors/stern/stargaze/Q5.htm | |||

| |title=The Atomic Nucleus and Bohr's Early Model of the Atom | |||

| |publisher=NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (mirror) | |||

| |access-date=20 December 2007 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081017073826/http://www.iki.rssi.ru/mirrors/stern/stargaze/Q5.htm | |||

| |archive-date=17 October 2008 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| A more accurate description of the hydrogen atom comes from a quantum analysis that uses the ], ] or ] ] to calculate the ] of the electron around the proton.<ref>{{cite web| last=Stern| first=D. P.| date=13 February 2005| url=http://www-spof.gsfc.nasa.gov/stargaze/Q7.htm| title=Wave Mechanics| publisher=NASA Goddard Space Flight Center| access-date=16 April 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080513195241/http://www-spof.gsfc.nasa.gov/stargaze/Q7.htm| archive-date=13 May 2008| url-status=live}}</ref> The most complex formulas include the small effects of ] and ]. In the quantum mechanical treatment, the electron in a ground state hydrogen atom has no angular momentum—illustrating how the "planetary orbit" differs from electron motion. | |||

| === Spin isomers === | |||

| {{Main|Spin isomers of hydrogen}} | |||

| Molecular {{chem2|H2}} exists as two ]s, i.e. compounds that differ only in the ] of their nuclei.<ref name="uigi">{{cite web|author=Staff|date=2003|url=http://www.uigi.com/hydrogen.html|title=Hydrogen (H<sub>2</sub>) Properties, Uses, Applications: Hydrogen Gas and Liquid Hydrogen|publisher=Universal Industrial Gases, Inc.|access-date=5 February 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080219073329/http://www.uigi.com/hydrogen.html|archive-date=19 February 2008|url-status=live}}</ref> In the '''orthohydrogen''' form, the spins of the two nuclei are parallel, forming a spin ] having a ] <math>S = 1</math>; in the '''parahydrogen''' form the spins are antiparallel and form a spin ] having spin <math>S = 0</math>. The equilibrium ratio of ortho- to para-hydrogen depends on temperature. At room temperature or warmer, equilibrium hydrogen gas contains about 25% of the para form and 75% of the ortho form.<ref name="Green2012">{{cite journal |last1=Green |first1=Richard A. |display-authors=etal |title=The theory and practice of hyperpolarization in magnetic resonance using ''para''hydrogen |journal=Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. |date=2012 |volume=67 |pages=1–48 |doi=10.1016/j.pnmrs.2012.03.001 |pmid=23101588 |bibcode=2012PNMRS..67....1G |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0079656512000477 |access-date=28 August 2021 |archive-date=28 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210828222611/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0079656512000477 |url-status=live }}</ref> The ortho form is an ], having higher energy than the para form by 1.455 kJ/mol,<ref name="PlanckInstitut">{{cite web |url=https://www.mpibpc.mpg.de/146336/para-Wasserstoff |language=de |website=Max-Planck-Institut für Biophysikalische Chemie |title=Die Entdeckung des para-Wasserstoffs (The discovery of para-hydrogen) |access-date=9 November 2020 |archive-date=16 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201116064055/https://www.mpibpc.mpg.de/146336/para-Wasserstoff |url-status=live }}</ref> and it converts to the para form over the course of several minutes when cooled to low temperature.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Milenko|first1=Yu. Ya.|last2=Sibileva|first2=R. M.|last3=Strzhemechny|first3=M. A.|title=Natural ortho-para conversion rate in liquid and gaseous hydrogen|journal=Journal of Low Temperature Physics|date=1997|volume=107|issue=1–2|pages=77–92 | |||

| |doi=10.1007/BF02396837|bibcode = 1997JLTP..107...77M |s2cid=120832814}}</ref> The thermal properties of the forms differ because they differ in their allowed ]<!-- This link is less direct than ] but presently the subject better (June 2021).-->, resulting in different thermal properties such as the heat capacity.<ref name="NASA">{{cite web|last=Hritz|first=J.|date=March 2006|url=http://smad-ext.grc.nasa.gov/gso/manual/chapter_06.pdf|title=CH. 6 – Hydrogen|work=NASA Glenn Research Center Glenn Safety Manual, Document GRC-MQSA.001|publisher=NASA|access-date=5 February 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080216050326/http://smad-ext.grc.nasa.gov/gso/manual/chapter_06.pdf|archive-date=16 February 2008}}</ref> | |||

| The ortho-to-para ratio in {{chem2|H2}} is an important consideration in the ] and storage of ]: the conversion from ortho to para is ] and produces enough heat to evaporate most of the liquid if not converted first to parahydrogen during the cooling process.<ref name="Amos98">{{cite web|url=http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy99osti/25106.pdf|title=Costs of Storing and Transporting Hydrogen|publisher=National Renewable Energy Laboratory|date=1 November 1998|first1=Wade A.|last1=Amos|pages=6–9|access-date=19 May 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141226131234/http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy99osti/25106.pdf|archive-date=26 December 2014|url-status=live}}</ref> ]s for the ortho-para interconversion, such as ] and ] compounds, are used during hydrogen cooling to avoid this loss of liquid.<ref name="Svadlenak">{{cite journal|last1=Svadlenak|first1=R. E.|last2=Scott|first2=A. B.|title=The Conversion of Ortho- to Parahydrogen on Iron Oxide-Zinc Oxide Catalysts|journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society|date=1957|volume=79|issue=20|pages=5385–5388|doi=10.1021/ja01577a013}}</ref> | |||

| === Phases === | |||

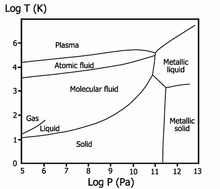

| ].]] | |||

| ] of hydrogen. The temperature and pressure scales are ], so one unit corresponds to a 10× change. The left edge corresponds to 10{{sup|5}} Pa, or about one atmosphere.{{image reference needed|date=December 2022}}|alt=Phase diagram of hydrogen on logarithmic scales. Lines show boundaries between phases, with the end of the liquid-gas line indicating the critical point. The triple point of hydrogen is just off-scale to the left.]] | |||

| * ]eous hydrogen | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] hydrogen | |||

| === Compounds === | |||

| {{Main|Hydrogen compounds}} | |||

| ==== Covalent and organic compounds ==== | |||

| While {{chem2|H2}} is not very reactive under standard conditions, it does form compounds with most elements. Hydrogen can form compounds with elements that are more ], such as ]s (F, Cl, Br, I), or ]; in these compounds hydrogen takes on a partial positive charge.<ref>{{cite web|last=Clark|first=J.|title=The Acidity of the Hydrogen Halides|work=Chemguide|date=2002|url=http://www.chemguide.co.uk/inorganic/group7/acidityhx.html#top|access-date=9 March 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080220174205/http://www.chemguide.co.uk/inorganic/group7/acidityhx.html#top|archive-date=20 February 2008}}</ref> When bonded to a more electronegative element, particularly ], ], or ], hydrogen can participate in a form of medium-strength noncovalent bonding with another electronegative element with a lone pair, a phenomenon called ]ing that is critical to the stability of many biological molecules.<ref>{{cite web|last=Kimball|first=J. W.|title=Hydrogen|work=Kimball's Biology Pages|date=7 August 2003|url=http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/H/HydrogenBonds.html|access-date=4 March 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080304040611/http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/H/HydrogenBonds.html|archive-date=4 March 2008|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, Electronic version, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080319045705/http://goldbook.iupac.org/H02899.html |date=19 March 2008 }}</ref> Hydrogen also forms compounds with less electronegative elements, such as ]s and ]s, where it takes on a partial negative charge. These compounds are often known as ]s.<ref>{{cite web|last=Sandrock|first=G.|title=Metal-Hydrogen Systems|publisher=Sandia National Laboratories|date=2 May 2002|url=http://hydpark.ca.sandia.gov/DBFrame.html|access-date=23 March 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080224162206/http://hydpark.ca.sandia.gov/DBFrame.html|archive-date=24 February 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Hydrogen forms many compounds with ] called the ]s, and even more with ]s that, due to their association with living things, are called ]s.<ref name="hydrocarbon">{{cite web| title=Structure and Nomenclature of Hydrocarbons| publisher=Purdue University| url=http://chemed.chem.purdue.edu/genchem/topicreview/bp/1organic/organic.html| access-date=23 March 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120611084045/http://chemed.chem.purdue.edu/genchem/topicreview/bp/1organic/organic.html| archive-date=11 June 2012}}</ref> The study of their properties is known as ]<ref>{{cite web| title=Organic Chemistry| work=Dictionary.com| publisher=Lexico Publishing Group| date=2008| url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/organic%20chemistry| access-date=23 March 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080418093054/http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/organic%20chemistry| archive-date=18 April 2008| url-status=live}}</ref> and their study in the context of living ]s is called ].<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |title=Biochemistry | |||

| |work=Dictionary.com | |||

| |publisher=Lexico Publishing Group | |||

| |date=2008 | |||

| |url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/biochemistry | |||

| |access-date=23 March 2008 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080329151719/http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/biochemistry | |||

| |archive-date=29 March 2008 | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> By some definitions, "organic" compounds are only required to contain carbon. However, most of them also contain hydrogen, and because it is the carbon-hydrogen bond that gives this class of compounds most of its particular chemical characteristics, carbon-hydrogen bonds are required in some definitions of the word "organic" in chemistry.<ref name="hydrocarbon" /> Millions of ]s are known, and they are usually formed by complicated pathways that seldom involve elemental hydrogen. | |||

| Hydrogen is highly soluble in many ] and ]s<ref name="Takeshita">{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Takeshita|first1=T. | |||

| |last2=Wallace|first2=W. E. | |||

| |last3=Craig|first3=R. S. | |||

| |title=Hydrogen solubility in 1:5 compounds between yttrium or thorium and nickel or cobalt | |||

| |journal=] | |||

| |volume=13|issue=9|pages=2282–2283 | |||

| |date=1974 | |||

| |doi=10.1021/ic50139a050 | |||

| }}</ref> and is soluble in both nanocrystalline and ]s.<ref name="Kirchheim1">{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Kirchheim|first1=R. | |||

| |last2=Mutschele|first2=T. | |||

| |last3=Kieninger|first3=W. | |||

| |title=Hydrogen in amorphous and nanocrystalline metals | |||

| |journal=Materials Science and Engineering | |||

| |date=1988|volume=99|issue=1–2 | |||

| |pages=457–462 | |||

| |doi=10.1016/0025-5416(88)90377-1 | |||

| |last4=Gleiter | |||

| |first4=H. | |||

| |last5=Birringer | |||

| |first5=R. | |||

| |last6=Koble | |||

| |first6=T. | |||

| }}</ref> Hydrogen ] in metals is influenced by local distortions or impurities in the ].<ref name="Kirchheim2">{{cite journal | |||

| |last=Kirchheim|first=R. | |||

| |title=Hydrogen solubility and diffusivity in defective and amorphous metals | |||

| |journal=] | |||

| |volume=32|issue=4|pages=262–325 | |||

| |date=1988 | |||

| |doi=10.1016/0079-6425(88)90010-2 | |||

| }}</ref> These properties may be useful when hydrogen is purified by passage through hot ] disks, but the gas's high solubility is a metallurgical problem, contributing to the ] of many metals,<ref name="Rogers 1999 1057–1064" /> complicating the design of pipelines and storage tanks.<ref name="Christensen">{{cite news | |||

| |last1=Christensen | |||

| |first1=C. H. | |||

| |last2=Nørskov | |||

| |first2=J. K. | |||

| |last3=Johannessen | |||

| |first3=T. | |||

| |date=9 July 2005 | |||

| |title=Making society independent of fossil fuels – Danish researchers reveal new technology | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |url=http://news.mongabay.com/2005/0921-hydrogen_tablet.html | |||

| |access-date=19 May 2015 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150521085421/http://news.mongabay.com/2005/0921-hydrogen_tablet.html | |||

| |archive-date=21 May 2015 | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==== Hydrides ==== | |||

| {{Main|Hydride}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Hydrogen compounds are often called ]s, a term that is used fairly loosely. The term "hydride" suggests that the H atom has acquired a negative or anionic character, denoted {{chem2|H−}}; and is used when hydrogen forms a compound with a more ] element. The existence of the ], suggested by ] in 1916 for group 1 and 2 salt-like hydrides, was demonstrated by Moers in 1920 by the electrolysis of molten ] (LiH), producing a ] quantity of hydrogen at the anode.<ref name="Moers">{{cite journal|last=Moers|first=K.|title=Investigations on the Salt Character of Lithium Hydride|journal=Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie|date=1920|volume=113|issue=191|pages=179–228|doi=10.1002/zaac.19201130116|url=https://zenodo.org/record/1428170|access-date=24 August 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190824162148/https://zenodo.org/record/1428170/files/article.pdf|archive-date=24 August 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> For hydrides other than group 1 and 2 metals, the term is quite misleading, considering the low electronegativity of hydrogen. An exception in group 2 hydrides is {{chem2|BeH2}}, which is polymeric. In ], the {{chem2|-}} anion carries hydridic centers firmly attached to the Al(III). | |||

| Although hydrides can be formed with almost all main-group elements, the number and combination of possible compounds varies widely; for example, more than 100 binary borane hydrides are known, but only one binary aluminium hydride.<ref name="Downs">{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Downs|first1=A. J. | |||

| |last2=Pulham|first2=C. R. | |||

| |title=The hydrides of aluminium, gallium, indium, and thallium: a re-evaluation | |||

| |journal=Chemical Society Reviews | |||

| |date=1994|volume=23|pages=175–184 | |||

| |doi=10.1039/CS9942300175 | |||

| |issue=3 | |||

| }}</ref> Binary ] hydride has not yet been identified, although larger complexes exist.<ref name="Hibbs">{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Hibbs|first1=D. E. | |||

| |last2=Jones|first2=C.|last3=Smithies|first3=N. A. | |||

| |title=A remarkably stable indium trihydride complex: synthesis and characterisation of | |||

| |journal=Chemical Communications | |||

| |date=1999|pages=185–186|doi=10.1039/a809279f | |||

| |issue=2}}</ref> | |||

| In ], hydrides can also serve as ]s that link two metal centers in a ]. This function is particularly common in ]s, especially in ]s (] hydrides) and ] complexes, as well as in clustered ]s.<ref name="Miessler" /> | |||

| ==== Protons and acids ==== | |||

| {{Further|Acid–base reaction}} | |||

| Oxidation of hydrogen removes its electron and gives ], which contains no electrons and a ] which is usually composed of one proton. That is why {{chem2|H+}} is often called a proton. This species is central to discussion of ]s. Under the ], acids are proton donors, while bases are proton acceptors. | |||

| A bare proton, {{chem2|H+}}, cannot exist in solution or in ionic crystals because of its strong attraction to other atoms or molecules with electrons. Except at the high temperatures associated with plasmas, such protons cannot be removed from the ]s of atoms and molecules, and will remain attached to them. However, the term 'proton' is sometimes used loosely and metaphorically to refer to positively charged or ]ic hydrogen attached to other species in this fashion, and as such is denoted "{{chem2|H+}}" without any implication that any single protons exist freely as a species. | |||

| To avoid the implication of the naked "solvated proton" in solution, acidic aqueous solutions are sometimes considered to contain a less unlikely fictitious species, termed the "] ion" ({{chem2|+}}). However, even in this case, such solvated hydrogen cations are more realistically conceived as being organized into clusters that form species closer to {{chem2|+}}.<ref name="Okumura">{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Okumura|first1=A. M. | |||

| |last2=Yeh|first2=L. I.|last3=Myers|first3=J. D.|last4=Lee|first4=Y. T. | |||

| |title=Infrared spectra of the solvated hydronium ion: vibrational predissociation spectroscopy of mass-selected H<sub>3</sub>O+•(H<sub>2</sub>O<sub>)n</sub>•(H<sub>2</sub>)<sub>m</sub> | |||

| |journal=Journal of Physical Chemistry | |||

| |date=1990|volume=94|issue=9|pages=3416–3427|doi=10.1021/j100372a014 | |||

| }}</ref> Other ]s are found when water is in acidic solution with other solvents.<ref name="Perdoncin">{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Perdoncin|first1=G.|last2=Scorrano|first2=G. | |||

| |title=Protonation Equilibria in Water at Several Temperatures of Alcohols, Ethers, Acetone, Dimethyl Sulfide, and Dimethyl Sulfoxide | |||

| |journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society | |||

| |date=1977|volume=99|issue=21|pages=6983–6986 | |||

| |doi=10.1021/ja00463a035 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Although exotic on Earth, one of the most common ions in the universe is the {{chem2|H3+}} ion, known as ] or the trihydrogen cation.<ref name="Carrington">{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Carrington|first1=A.|last2=McNab|first2=I. R. | |||

| |title=The infrared predissociation spectrum of triatomic hydrogen cation (H<sub>3</sub><sup>+</sup>) | |||

| |journal=Accounts of Chemical Research | |||

| |date=1989|volume=22|issue=6|pages=218–222 | |||

| |doi=10.1021/ar00162a004}}</ref> | |||

| === Isotopes === | |||

| {{Main|Isotopes of hydrogen}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Hydrogen has three naturally occurring isotopes, denoted {{chem|1|H}}, {{chem|2|H}} and {{chem|3|H}}. Other, highly unstable nuclei ({{chem|4|H}} to {{chem|7|H}}) have been synthesized in the laboratory but not observed in nature.<ref name="Gurov">{{cite journal | |||

| |author=Gurov, Y. B. | |||

| |author2=Aleshkin, D. V. | |||

| |author3=Behr, M. N. | |||

| |author4=Lapushkin, S. V. | |||

| |author5=Morokhov, P. V. | |||

| |author6=Pechkurov, V. A. | |||

| |author7=Poroshin, N. O. | |||

| |author8=Sandukovsky, V. G. | |||

| |author9=Tel'kushev, M. V. | |||

| |author10=Chernyshev, B. A. | |||

| |author11=Tschurenkova, T. D. | |||

| |title=Spectroscopy of superheavy hydrogen isotopes in stopped-pion absorption by nuclei | |||

| |journal=Physics of Atomic Nuclei | |||

| |date=2004|volume=68|issue=3|pages=491–97 | |||

| |doi=10.1134/1.1891200 | |||

| |bibcode = 2005PAN....68..491G |s2cid=122902571 | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="Korsheninnikov">{{cite journal | |||

| |title=Experimental Evidence for the Existence of <sup>7</sup>H and for a Specific Structure of <sup>8</sup>He | |||

| |journal=Physical Review Letters | |||

| |date=2003|volume=90|issue=8|page=082501 | |||

| |doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.082501|pmid=12633420 | |||

| |bibcode=2003PhRvL..90h2501K | |||

| |display-authors=8 | |||

| |last1=Korsheninnikov | |||

| |first1=A. | |||

| |last2=Nikolskii | |||

| |first2=E. | |||

| |last3=Kuzmin | |||

| |first3=E. | |||

| |last4=Ozawa | |||

| |first4=A. | |||

| |last5=Morimoto | |||

| |first5=K. | |||

| |last6=Tokanai | |||

| |first6=F. | |||

| |last7=Kanungo | |||

| |first7=R. | |||

| |last8=Tanihata | |||

| |first8=I. | |||

| |last9=Timofeyuk | |||

| |first9=N.}}</ref> | |||

| * '''{{chem|1|H}}''' is the most common hydrogen isotope, with an abundance of >99.98%. Because the ] of this isotope consists of only a single proton, it is given the descriptive but rarely used formal name ''protium''.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| |last1=Urey|first1=H. C. | |||

| |last2=Brickwedde|first2=F. G.|last3=Murphy|first3=G. M. | |||

| |title=Names for the Hydrogen Isotopes | |||

| |journal=Science|date=1933|volume=78 | |||

| |issue=2035|pages=602–603 | |||

| |doi=10.1126/science.78.2035.602 | |||

| |pmid=17797765|bibcode = 1933Sci....78..602U }}</ref> It is the only stable isotope with no neutrons; see ] for a discussion of why others do not exist. | |||

| * '''{{chem|2|H}}''', the other stable hydrogen isotope, is known as ] and contains one proton and one ] in the nucleus. Nearly all deuterium in the universe is thought to have been produced at the time of the ], and has endured since then. Deuterium is not radioactive, and is not a significant toxicity hazard. Water enriched in molecules that include deuterium instead of normal hydrogen is called ]. Deuterium and its compounds are used as a non-radioactive label in chemical experiments and in solvents for {{chem|1|H}}-].<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| |author=Oda, Y. | |||

| |author2=Nakamura, H. | |||

| |author3=Yamazaki, T. | |||

| |author4=Nagayama, K. | |||

| |author5=Yoshida, M. | |||

| |author6=Kanaya, S. | |||

| |author7=Ikehara, M. | |||

| |title=1H NMR studies of deuterated ribonuclease HI selectively labeled with protonated amino acids | |||

| |journal=] | |||

| |date=1992|volume=2|issue=2|pages=137–47 | |||

| |doi=10.1007/BF01875525 | |||

| |pmid=1330130|s2cid=28027551 | |||

| }}</ref> Heavy water is used as a ] and coolant for nuclear reactors. Deuterium is also a potential fuel for commercial ].<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |last=Broad | |||

| |first=W. J. | |||

| |date=11 November 1991 | |||

| |title=Breakthrough in Nuclear Fusion Offers Hope for Power of Future | |||

| |work=The New York Times | |||

| |url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE4D81030F932A25752C1A967958260 | |||

| |access-date=12 February 2008 | |||

| |archive-date=29 January 2021 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210129015717/https://www.nytimes.com/1991/11/11/us/breakthrough-in-nuclear-fusion-offers-hope-for-power-of-future.html | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| * '''{{chem|3|H}}''' is known as ] and contains one proton and two neutrons in its nucleus. It is radioactive, decaying into ] through ] with a ] of 12.32 years.<ref name="Miessler" /> It is radioactive enough to be used in ] to enhance the visibility of data displays, such as for painting the hands and dial-markers of watches. The watch glass prevents the small amount of radiation from escaping the case.<ref name="Traub95">{{cite web|last1=Traub|first1=R. J.|last2=Jensen|first2=J. A.|title=Tritium radioluminescent devices, Health and Safety Manual|url=http://www.iaea.org/inis/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/27/001/27001618.pdf|publisher=International Atomic Energy Agency|access-date=20 May 2015|page=2.4|date=June 1995|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906043743/http://www.iaea.org/inis/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/27/001/27001618.pdf|archive-date=6 September 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> Small amounts of tritium are produced naturally by cosmic rays striking atmospheric gases; tritium has also been released in ].<ref>{{cite web| author=Staff| date=15 November 2007| url=http://www.epa.gov/rpdweb00/radionuclides/tritium.html| publisher=U.S. Environmental Protection Agency| title=Tritium| access-date=12 February 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080102171148/http://www.epa.gov/rpdweb00/radionuclides/tritium.html| archive-date=2 January 2008| url-status=live}}</ref> It is used in nuclear fusion,<ref>{{cite web| last=Nave| first=C. R.| title=Deuterium-Tritium Fusion| work=HyperPhysics| publisher=Georgia State University| date=2006| url=http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/Hbase/nucene/fusion.html| access-date=8 March 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080316055852/http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/Hbase/nucene/fusion.html| archive-date=16 March 2008| url-status=live}}</ref> as a tracer in ],<ref>{{cite journal| first1=C.| last1=Kendall| first2=E.| last2=Caldwell| journal=Isotope Tracers in Catchment Hydrology| title=Chapter 2: Fundamentals of Isotope Geochemistry| editor1=C. Kendall| editor2=J. J. McDonnell| publisher=US Geological Survey| date=1998| doi=10.1016/B978-0-444-81546-0.50009-4| url=http://wwwrcamnl.wr.usgs.gov/isoig/isopubs/itchch2.html#2.5.1| access-date=8 March 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080314192517/http://wwwrcamnl.wr.usgs.gov/isoig/isopubs/itchch2.html#2.5.1| archive-date=14 March 2008| pages=51–86}}</ref> and in specialized ] devices.<ref>{{cite web| title=The Tritium Laboratory| publisher=University of Miami| date=2008| url=http://www.rsmas.miami.edu/groups/tritium/| access-date=8 March 2008| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080228061358/http://www.rsmas.miami.edu/groups/tritium/| archive-date=28 February 2008| df=dmy-all}}</ref> Tritium has also been used in chemical and biological labeling experiments as a ].<ref name="holte">{{cite journal| last1=Holte| first1=A. E.| last2=Houck| first2=M. A.| last3=Collie| first3=N. L.| title=Potential Role of Parasitism in the Evolution of Mutualism in Astigmatid Mites| journal=Experimental and Applied Acarology| volume=25| issue=2| pages=97–107| date=2004|doi=10.1023/A:1010655610575| pmid=11513367| s2cid=13159020}}</ref> | |||

| Unique among the elements, distinct names are assigned to its isotopes in common use. During the early study of radioactivity, heavy radioisotopes were given their own names, but these are mostly no longer used. The symbols D and T (instead of {{chem|2|H}} and {{chem|3|H}}) are sometimes used for deuterium and tritium, but the symbol P was already used for ] and thus was not available for protium.<ref>{{cite web|last=van der Krogt|first=P.|date=5 May 2005|url=http://elements.vanderkrogt.net/element.php?sym=H|publisher=Elementymology & Elements Multidict|title=Hydrogen|access-date=20 December 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100123001440/http://elements.vanderkrogt.net/element.php?sym=H|archive-date=23 January 2010}}</ref> In its ] guidelines, the ] (IUPAC) allows any of D, T, {{chem|2|H}}, and {{chem|3|H}} to be used, though {{chem|2|H}} and {{chem|3|H}} are preferred.<ref>§ IR-3.3.2, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160209043933/http://old.iupac.org/reports/provisional/abstract04/RB-prs310804/Chap3-3.04.pdf |date=9 February 2016 }}, Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry, Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division, IUPAC. Accessed on line 3 October 2007.</ref> | |||

| The ] ] (symbol Mu), composed of an anti] and an ], can also be considered a light radioisotope of hydrogen.<ref name="Gold">{{cite book|author=IUPAC|title=Compendium of Chemical Terminology|title-link=Compendium of Chemical Terminology|publisher=]|year=1997|isbn=978-0-86542-684-9|editor=A. D. McNaught, A. Wilkinson|edition=2nd|chapter=Muonium|doi=10.1351/goldbook.M04069|author-link=International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry|access-date=15 November 2016|chapter-url=http://goldbook.iupac.org/M04069.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080313121643/http://goldbook.iupac.org/M04069.html|archive-date=13 March 2008|url-status=live}}</ref> Because muons decay with lifetime {{val|2.2|u=]}}, muonium is too unstable for observable chemistry.<ref name="Hughes">{{cite journal|author=V. W. Hughes|display-authors=etal|year=1960|title=Formation of Muonium and Observation of its Larmor Precession|journal=]|volume=5|issue=2|pages=63–65|bibcode=1960PhRvL...5...63H|doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.5.63}}</ref> Nevertheless, muonium compounds are important test cases for ], due to the mass difference between the antimuon and the proton,<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Bondi|first1=D. K.|last2=Connor|first2=J. N. L.|last3=Manz|first3=J.|last4=Römelt|first4=J.|date=20 October 1983|title=Exact quantum and vibrationally adiabatic quantum, semiclassical and quasiclassical study of the collinear reactions Cl + MuCl, Cl + HCl, Cl + DCl|journal=Molecular Physics|volume=50|issue=3|pages=467–488|doi=10.1080/00268978300102491|bibcode=1983MolPh..50..467B |issn=0026-8976}}</ref> and IUPAC nomenclature incorporates such hypothetical compounds as muonium chloride (MuCl) and sodium muonide (NaMu), analogous to ] and ] respectively.<ref name="iupac">{{cite journal | |||

| |doi=10.1351/pac200173020377 | |||

| |author=W. H. Koppenol | |||

| |author2=IUPAC | |||

| |author2-link=International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry | |||

| |year=2001 | |||

| |title=Names for muonium and hydrogen atoms and their ions | |||

| |url=http://www.iupac.org/publications/pac/2001/pdf/7302x0377.pdf | |||

| |journal=] | |||

| |volume=73 | |||

| |issue=2 | |||

| |pages=377–380 | |||

| |s2cid=97138983 | |||

| |access-date=15 November 2016 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514000319/http://www.iupac.org/publications/pac/2001/pdf/7302x0377.pdf | |||

| |archive-date=14 May 2011 | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| === Thermal and physical properties === | |||

| Table of thermal and physical properties of hydrogen (H{{sub|2}}) at atmospheric pressure:<ref>{{Cite book |last=Holman |first=Jack P. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/46959719 |title=Heat transfer |date=2002 |publisher=McGraw-Hill |isbn=0-07-240655-0 |edition=9th |location=New York, NY |pages=600–606 |language=English |oclc=46959719}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author-link1=Frank P. Incropera |last1=Incropera |last2=Dewitt |last3=Bergman |last4=Lavigne |first1=Frank P. |first2=David P. |first3=Theodore L. |first4=Adrienne S. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62532755 |title=Fundamentals of heat and mass transfer |date=2007 |publisher=John Wiley and Sons, Inc |isbn=978-0-471-45728-2 |edition=6th |location=Hoboken, NJ |pages=941–950 |language=English |oclc=62532755 }}</ref> | |||

| {|class="wikitable mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" | |||

| |Temperature (K) | |||

| |Density (kg/m^3) | |||

| |Specific heat (kJ/kg K) | |||

| |Dynamic viscosity (kg/m s) | |||

| |Kinematic viscosity (m^2/s) | |||

| |Thermal conductivity (W/m K) | |||

| |Thermal diffusivity (m^2/s) | |||

| |Prandtl Number | |||

| |- | |||

| |100 | |||

| |0.24255 | |||

| |11.23 | |||

| |4.21E-06 | |||

| |1.74E-05 | |||

| |6.70E-02 | |||

| |2.46E-05 | |||

| |0.707 | |||

| |- | |||

| |150 | |||

| |0.16371 | |||

| |12.602 | |||

| |5.60E-06 | |||

| |3.42E-05 | |||

| |0.0981 | |||

| |4.75E-05 | |||

| |0.718 | |||

| |- | |||

| |200 | |||

| |0.1227 | |||

| |13.54 | |||

| |6.81E-06 | |||

| |5.55E-05 | |||

| |0.1282 | |||

| |7.72E-05 | |||

| |0.719 | |||

| |- | |||

| |250 | |||

| |0.09819 | |||

| |14.059 | |||

| |7.92E-06 | |||

| |8.06E-05 | |||

| |0.1561 | |||

| |1.13E-04 | |||

| |0.713 | |||

| |- | |||

| |300 | |||

| |0.08185 | |||

| |14.314 | |||

| |8.96E-06 | |||

| |1.10E-04 | |||

| |0.182 | |||

| |1.55E-04 | |||

| |0.706 | |||

| |- | |||

| |350 | |||

| |0.07016 | |||

| |14.436 | |||

| |9.95E-06 | |||

| |1.42E-04 | |||

| |0.206 | |||

| |2.03E-04 | |||

| |0.697 | |||

| |- | |||

| |400 | |||

| |0.06135 | |||

| |14.491 | |||

| |1.09E-05 | |||

| |1.77E-04 | |||

| |0.228 | |||

| |2.57E-04 | |||

| |0.69 | |||

| |- | |||

| |450 | |||

| |0.05462 | |||

| |14.499 | |||

| |1.18E-05 | |||

| |2.16E-04 | |||

| |0.251 | |||

| |3.16E-04 | |||

| |0.682 | |||

| |- | |||

| |500 | |||

| |0.04918 | |||

| |14.507 | |||

| |1.26E-05 | |||

| |2.57E-04 | |||

| |0.272 | |||

| |3.82E-04 | |||

| |0.675 | |||

| |- | |||

| |550 | |||

| |0.04469 | |||

| |14.532 | |||

| |1.35E-05 | |||

| |3.02E-04 | |||

| |0.292 | |||

| |4.52E-04 | |||

| |0.668 | |||

| |- | |||

| |600 | |||

| |0.04085 | |||

| |14.537 | |||

| |1.43E-05 | |||

| |3.50E-04 | |||

| |0.315 | |||

| |5.31E-04 | |||

| |0.664 | |||

| |- | |||

| |700 | |||

| |0.03492 | |||

| |14.574 | |||

| |1.59E-05 | |||

| |4.55E-04 | |||

| |0.351 | |||

| |6.90E-04 | |||

| |0.659 | |||

| |- | |||

| |800 | |||

| |0.0306 | |||

| |14.675 | |||

| |1.74E-05 | |||

| |5.69E-04 | |||

| |0.384 | |||

| |8.56E-04 | |||

| |0.664 | |||

| |- | |||

| |900 | |||

| |0.02723 | |||

| |14.821 | |||

| |1.88E-05 | |||

| |6.90E-04 | |||

| |0.412 | |||

| |1.02E-03 | |||

| |0.676 | |||

| |- | |||

| |1000 | |||

| |0.02424 | |||

| |14.99 | |||

| |2.01E-05 | |||

| |8.30E-04 | |||

| |0.448 | |||

| |1.23E-03 | |||

| |0.673 | |||

| |- | |||

| |1100 | |||

| |0.02204 | |||

| |15.17 | |||

| |2.13E-05 | |||

| |9.66E-04 | |||

| |0.488 | |||

| |1.46E-03 | |||

| |0.662 | |||

| |- | |||

| |1200 | |||

| |0.0202 | |||

| |15.37 | |||

| |2.26E-05 | |||

| |1.12E-03 | |||

| |0.528 | |||

| |1.70E-03 | |||

| |0.659 | |||

| |- | |||

| |1300 | |||

| |0.01865 | |||

| |15.59 | |||

| |2.39E-05 | |||

| |1.28E-03 | |||

| |0.568 | |||

| |1.96E-03 | |||

| |0.655 | |||

| |- | |||

| |1400 | |||

| |0.01732 | |||

| |15.81 | |||

| |2.51E-05 | |||

| |1.45E-03 | |||

| |0.61 | |||

| |2.23E-03 | |||

| |0.65 | |||

| |- | |||

| |1500 | |||

| |0.01616 | |||

| |16.02 | |||

| |2.63E-05 | |||

| |1.63E-03 | |||

| |0.655 | |||

| |2.53E-03 | |||

| |0.643 | |||

| |- | |||

| |1600 | |||

| |0.0152 | |||

| |16.28 | |||

| |2.74E-05 | |||

| |1.80E-03 | |||

| |0.697 | |||

| |2.82E-03 | |||

| |0.639 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1700 | |||

| | ] || 13.8033 K, 7.042 kPa | |||

| |0.0143 | |||

| {{Elementbox_heatfusion_kjpmol | (H<sub>2</sub>) 0.117 }} | |||

| |16.58 | |||

| {{Elementbox_heatvaporiz_kjpmol | (H<sub>2</sub>) 0.904 }} | |||

| |2.85E-05 | |||

| {{Elementbox_heatcapacity_jpmolkat25 | (H<sub>2</sub>)<br />28.836 }} | |||

| |1.99E-03 | |||

| {{Elementbox_vaporpressure_katpa | | | | | 15 | 20 | comment= }} | |||

| |0.742 | |||

| |3.13E-03 | |||

| |0.637 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1800 | |||

| | ] || 32.19 K | |||

| |0.0135 | |||

| |16.96 | |||

| |2.96E-05 | |||

| |2.19E-03 | |||

| |0.786 | |||

| |3.44E-03 | |||

| |0.639 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1900 | |||

| | ] || 1.315 MPa | |||

| |0.0128 | |||

| |17.49 | |||

| |3.07E-05 | |||

| |2.40E-03 | |||

| |0.835 | |||

| |3.73E-03 | |||

| |0.643 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |2000 | |||

| | ] || 30.12 g/L | |||

| |0.0121 | |||

| {{Elementbox_section_atomicprop | color1=#a0ffa0 | color2=green }} | |||

| |18.25 | |||

| {{Elementbox_crystalstruct | hexagonal }} | |||

| |3.18E-05 | |||

| {{Elementbox_oxistates | '''1''', -1<br />(] oxide) }} | |||

| |2.63E-03 | |||

| {{Elementbox_electroneg_pauling | 2.20 }} | |||

| |0.878 | |||

| {{Elementbox_ionizationenergies1 | 1312.0 }} | |||

| |3.98E-03 | |||

| {{Elementbox_atomicradius_pm | ] }} | |||

| |0.661 | |||

| {{Elementbox_atomicradiuscalc_pm | ] }} (]) | |||

| |} | |||

| {{Elementbox_covalentradius_pm | ] }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_vanderwaalsrad_pm | ] }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_section_miscellaneous | color1=#a0ffa0 | color2=green }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_magnetic | ??? }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_thermalcond_wpmkat300k | 180.5 m}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_speedofsound_mps | (gas, 27 °C) 1310 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_cas_number | 1333-74-0 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_begin | isotopesof=hydrogen | color1=#a0ffa0 | color2=green }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_stable | mn=1 | sym=H | na=99.985% | n=0 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_stable | mn=2 | sym=H | na=0.015% | n=1 }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_decay | mn=3 | sym=H | na=] | hl=12.32 ] | dm=] | de=0.019 | pn=3 | ps=] }} | |||

| {{Elementbox_isotopes_end}} | |||

| {{Elementbox_footer | color1=#a0ffa0 | color2=green }} | |||

| == History == | |||

| '''Hydrogen''' (]: ''hydrogenium'', from ]: ''hydro'': water, ''genes'': forming) is a ] in the ] that has the symbol '''H''' and ] 1. At ] it is a colorless, odorless, ]lic, ], tasteless, highly ] ] ]. Hydrogen is the lightest and most ] element in the ]. It is present in ], all organic compounds (rare exceptions exist, like ]) and in all living organisms. Hydrogen is able to react chemically with most other elements. ] in their ] are overwhelmingly composed of hydrogen in its ] state. The element is used in ] production, as a ] gas, as an alternative ], and more recently as a power source of ]s. | |||

| === Discovery and use === | |||

| Despite its ubiquity in the universe, hydrogen is surprisingly hard to produce in large quantities on the Earth. In the ], the element is prepared by the reaction of ]s on metals such as ]. The ] of water is a simple method of producing hydrogen, but is economically inefficient for mass production. Large-scale production is usually achieved by ] ]. Scientists are now researching new methods for hydrogen production; if they succeed in developing a cost-efficient method of large-scale production, hydrogen may become a viable alternative to ]-producing ]. One of the methods under investigation involves use of green ]; another promising method involves the conversion of biomass derivatives such as ] or ] at low temperatures using a ]. Yet another method is the "steaming" of Carbon, whereby hydrocarbons are broken down with heat to release hydrogen. | |||

| {{Main|Timeline of hydrogen technologies}} | |||

| ==== Robert Boyle ==== | |||

| ==Basic features== | |||

| ], who discovered the reaction between ] and dilute acids]] | |||

| Hydrogen is the lightest chemical element; its most common ] comprises just one negatively charged ], distributed around a positively charged ] (the ] of the atom). The electron is bound to the proton by the ], the electrical force that one stationary, electrically charged nanoparticle exerts on another. The hydrogen atom has special significance in ] as a simple physical system for which there is an exact solution to the ]; from that equation, the experimentally observed frequencies and intensities of the hydrogen's ]s can be calculated. Spectral lines are dark or bright lines in an otherwise uniform and continuous spectrum, resulting from an excess or deficiency of photons in a narrow frequency range, compared with the nearby frequencies. | |||

| In 1671, Irish scientist ] discovered and described the reaction between ] filings and dilute ]s, which results in the production of hydrogen gas.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Boyle |first=R. |url=https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo2/A29057.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext |title=Tracts written by the Honourable Robert Boyle containing new experiments, touching the relation betwixt flame and air, and about explosions, an hydrostatical discourse occasion'd by some objections of Dr. Henry More against some explications of new experiments made by the author of these tracts: To which is annex't, an hydrostatical letter, dilucidating an experiment about a way of weighing water in water, new experiments, of the positive or relative levity of bodies under water, of the air's spring on bodies under water, about the differing pressure of heavy solids and fluids |publisher=Printed for Richard Davis |year=1672 |pages=64–65}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | |||

| |first=M. | |||

| |last=Winter | |||

| |date=2007 | |||

| |url=http://education.jlab.org/itselemental/ele001.html | |||

| |title=Hydrogen: historical information | |||

| |publisher=WebElements Ltd | |||

| |access-date=5 February 2008 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080410102154/http://education.jlab.org/itselemental/ele001.html | |||

| |archive-date=10 April 2008 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=Having provided a saline spirit , which by an uncommon way of preparation was made exceeding sharp and piercing, we put into a vial, capable of containing three or four ounces of water, a convenient quantity of filings of steel, which were not such as are commonly sold in shops to Chymists and Apothecaries, (those being usually not free enough from rust) but such as I had a while before caus'd to be purposely fil'd off from a piece of good steel. This metalline powder being moistn'd in the viol with a little of the menstruum, was afterwards drench'd with more; whereupon the mixture grew very hot, and belch'd up copious and stinking fumes; which whether they consisted altogether of the volatile sulfur of the Mars , or of metalline steams participating of a sulfureous nature, and join'd with the saline exhalations of the menstruum, is not necessary to be here discuss'd. But whencesoever this stinking smoak proceeded, so inflammable it was, that upon the approach of a lighted candle to it, it would readily enough take fire, and burn with a blewish and somewhat greenish flame at the mouth of the viol for a good while together; and that, though with little light, yet with more strength than one would easily suspect.|author=Robert Boyle|title=Tracts written by the Honourable Robert Boyle containing new experiments, touching the relation betwixt flame and air...}} | |||

| At ], hydrogen forms a diatomic gas, H<sub>2</sub>, with a boiling point of only 20.27 ] and a melting point of 14.02 K.{{ref|commonsensescience.org}} Under extreme pressures, such as those at the center of ]s, the molecules lose their identity and the hydrogen becomes a ] (]). Under the extremely low pressure in space—virtually a vacuum—the element tends to exist as individual atoms, simply because there is no way for them to combine. However, clouds of H<sub>2</sub> and singular hydrogen atoms are said to form in ] and ]s and are associated with ], however the existence of singular hydrogen atoms is disputed. Hydrogen plays a vital role in powering ] through the ] and ]. These are ] processes, which release huge amounts of energy in stars and other hot celestial bodies as hydrogen atoms combine into ] atoms. | |||

| The word "sulfureous" may be somewhat confusing, especially since Boyle did a similar experiment with iron and sulfuric acid.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Szydło |first=Z. A. |date=2020 |title=Hydrogen - Some Historical Highlights |journal=Chemistry-Didactics-Ecology-Metrology |volume=25 |issue=1–2 |pages=5–34|doi=10.2478/cdem-2020-0001 |s2cid=231776282 |doi-access=free }}</ref> However, in all likelihood, "sulfureous" should here be understood to mean "combustible".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ramsay |first=W. |url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/52778/52778-h/52778-h.htm |title=The gases of the atmosphere: The history of their discovery |publisher=Macmillan |year=1896 |pages=19}}</ref> | |||

| At high temperatures, hydrogen gas can exist as a mixture of atoms, protons, and negatively charged hydride ions. This mixture has a high ] and ] in the ] range, and plays an important part in the emission of light from the ] and other ]. | |||

| ==== Henry Cavendish ==== | |||

| H<sub>2</sub> is highly soluble in water, alcohol, and ether. It has a high capacity for ], in which it is attached to and held to the surface of some substances. It is an odorless, tasteless, colorless, and highly ] gas that burns at concentrations as low as 4% H<sub>2</sub> in air. It reacts violently with ] and ], forming ]s that can damage the ]s and other ]s. When mixed with oxygen, hydrogen explodes on ignition. A unique property of hydrogen is that its flame is completely invisible in air. This makes it difficult to tell if a leak is burning, and carries the added risk that it is easy to walk into a hydrogen fire inadvertently. | |||

| In 1766, ] was the first to recognize hydrogen gas as a discrete substance, by naming the gas from a ] "inflammable air". He speculated that "inflammable air" was in fact identical to the hypothetical substance "]"<ref>{{cite book |last = Musgrave | |||

| |first = A. | |||

| |chapter = Why did oxygen supplant phlogiston? Research programmes in the Chemical Revolution | |||

| |title = Method and appraisal in the physical sciences | |||

| |series = The Critical Background to Modern Science, 1800–1905 | |||

| |editor = Howson, C. | |||

| |year = 1976 | |||

| |publisher = Cambridge University Press | |||

| |access-date = 22 October 2011 | |||

| |chapter-url = http://ebooks.cambridge.org/chapter.jsf?bid=CBO9780511760013&cid=CBO9780511760013A009 | |||

| |doi = 10.1017/CBO9780511760013 | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-521-21110-9 | |||

| |url-access = registration | |||

| |url = https://archive.org/details/methodappraisali0000unse | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="cav766">{{cite journal|last1=Cavendish|first1=Henry|title=Three Papers, Containing Experiments on Factitious Air, by the Hon. Henry Cavendish, F. R. S.|journal=Philosophical Transactions|date=12 May 1766|volume=56|pages=141–184|jstor=105491|bibcode=1766RSPT...56..141C|doi=10.1098/rstl.1766.0019|doi-access=free}}</ref> and further finding in 1781 that the gas produces water when burned. He is usually given credit for the discovery of hydrogen as an element.<ref name="Nostrand">{{cite encyclopedia| title=Hydrogen| encyclopedia=Van Nostrand's Encyclopedia of Chemistry| pages=797–799| publisher=Wylie-Interscience| year=2005| isbn=978-0-471-61525-5}}</ref><ref name="nbb">{{cite book| last=Emsley| first=John| title=Nature's Building Blocks| publisher=Oxford University Press| year=2001| location=Oxford| pages=183–191| isbn=978-0-19-850341-5}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Antoine Lavoisier ==== | |||

| ''See also: ].'' | |||

| ], who identified the element that came to be known as hydrogen]] | |||

| In 1783, ] identified the element that came to be known as hydrogen<ref>{{cite book| last=Stwertka| first=Albert| title=A Guide to the Elements| url=https://archive.org/details/guidetoelements00stwe| url-access=registration| publisher=Oxford University Press| year=1996| pages=| isbn=978-0-19-508083-4}}</ref> when he and ] reproduced Cavendish's finding that water is produced when hydrogen is burned.<ref name="nbb" /> Lavoisier produced hydrogen for his experiments on mass conservation by reacting a flux of steam with metallic ] through an incandescent iron tube heated in a fire. Anaerobic oxidation of iron by the protons of water at high temperature can be schematically represented by the set of following reactions: | |||

| :1) {{chem2|Fe + H2O -> FeO + H2}} | |||

| :2) {{chem2|Fe + 3 H2O -> Fe2O3 + 3 H2}} | |||

| ==Applications== | |||

| Large quantities of hydrogen are needed in the chemical and petrolium industries, notably in the ] for the production of ], which by mass ranks as the world's fifth most highly produced industrial compound. Hydrogen is used in the ] of ]s and ]s (into items such as ]), and in the production of ]. Hydrogen is used in ], ], and ]{{ref|periodic.lanl.gov}}. The element has several other important uses. | |||

| *The element is used in the manufacture of ], in ] processes, and in the reduction of metallic ]s. | |||

| *It is an ingredient in ]s. | |||

| *It is used as the rotor coolant in ]s at ]s, because it has the highest ] of any gas. | |||

| *Liquid hydrogen is used in ] research, including ] studies. | |||

| *The ] temperature of equilibrium hydrogen is a defining fixed point on the ] temperature scale. | |||

| *Since hydrogen is 14.5 times ], it was once widely used as a lifting agent in ]s and ]s. However, this use was curtailed when the ] convinced the public that the gas was too dangerous for this purpose. | |||

| *], an isotope of hydrogen (hydrogen-2), is used in ] as a ] to slow ]s, and in ] reactions. Deuterium compounds have applications in ] and ] in studies of reaction ]s. | |||

| *] (hydrogen-3), produced in ]s, is used in the production of ]s, as an isotopic label in the biosciences, and as a ] source in luminous paints. | |||

| :3) {{chem2|Fe + 4 H2O -> Fe3O4 + 4 H2}} | |||

| There are no "hydrogen wells" or "hydrogen mines" on Earth, so hydrogen cannot be considered a primary energy source like ]s or ]. Hydrogen can however be burned in ]s, an approach advocated by BMW's experimental ]. However, it is currently difficult and dangerous to store and handle in sufficient quantity for motor fuel use. Hydrogen ]s are being investigated as mobile ] sources with lower emissions than hydrogen-burning internal combustion engines. The low emissions of hydrogen in internal combustion engines and ]s are currently offset by the pollution created by hydrogen production. This may change if the substantial amounts of electricity required for water ] can be generated primarily from low pollution sources such as nuclear energy or wind. Research is being conducted on hydrogen as a replacement for fossil fuels. It could become the link between a range of energy sources, carriers and storage. Hydrogen can be converted to and from electricity (solving the electricity storage and transport issues), from ]s, and from and into ] and ] fuel. All of this can theoretically be achieved with zero emissions of CO<sub>2</sub> and toxic pollutants. | |||

| Many metals such as ] undergo a similar reaction with water leading to the production of hydrogen.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Northwood |first=D. O. |last2=Kosasih |first2=U. |date=1983 |title=Hydrides and delayed hydrogen cracking in zirconium and its alloys |url=https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1179/imtr.1983.28.1.92 |journal=International Metals Reviews |language=en |volume=28 |issue=1 |pages=92–121 |doi=10.1179/imtr.1983.28.1.92 |issn=0308-4590}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Hydrogen was first produced by Theophratus Bombastus von Hohenheim (]–])—also known as ]—by mixing metals with acids. He was unaware that the explosive gas produced by this chemical reaction was hydrogen. In 1671, ] described the reaction between two iron fillings and dilute acids, which results in the production of gaseous hydrogen.{{ref|webelements.com}} In ], ] was the first to recognize hydrogen as a discrete substance, by identifying the gas from this reaction <!--you mean Boyle's reported reaction?-->as "inflammable" and finding that the gas produces water when burned in air. Cavendish stumbled on hydrogen when experimenting with acids and ]. Although he wrongly assumed that hydrogen was a compound of mercury—and not of the ]—he was still able to accurately describe several key properties of hydrogen. | |||

| ==== 19th century ==== | |||

| <!--In ,-->] gave the element its name and proved that water is composed of hydrogen and ]. One of the first uses of the element was for ]s. The hydrogen was obtained by mixing ] and ]. <!--In ,-->] discovered ], an ] of hydrogen, by repeated distilling the same sample of water. For this discovery, Urey received the ] for <!--chemistry?-->in 1934. In the same year, the third isotope, ], was discovered. Because of its relatively simple structure, hydrogen has often been used in models of how an ] works. | |||

| ] built the first ], an internal combustion engine powered by a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen in 1806. ] invented the hydrogen gas blowpipe in 1819. The ] and ] were invented in 1823.<ref name="nbb" /> | |||

| Hydrogen was ] for the first time by ] in 1898 by using ] and his invention, the ].<ref name="nbb" /> He produced ] the next year.<ref name="nbb" /> | |||

| ==Electron energy levels== | |||

| The ] ] of the electron in a Hydrogen atom is 13.6 ], which is equivalent to an ultraviolet photon of roughly 92 ]. | |||

| ==== Hydrogen-lifted airship ==== | |||

| With the ] the energy levels of Hydrogen can be calculated fairly accurately. This is done by modeling the electron as revolving around the proton, much like the earth revolving around the sun. Except the sun holds earth in orbit with the force of ], but the proton holds the electron in orbit with the force of ]. Another difference between the Earth-Sun system and the Electron-Proton system is that, in this model, due to ] the electron is allowed to only be at very specific distances from the proton. Modeling the hydrogen atom in this fashion yields the correct energy levels and spectrum. | |||

| ] over ] in 1937]] | |||

| The first hydrogen-filled ] was invented by ] in 1783.<ref name="nbb" /> Hydrogen provided the lift for the first reliable form of air-travel following the 1852 invention of the first hydrogen-lifted ] by ].<ref name="nbb" /> German count ] promoted the idea of rigid airships lifted by hydrogen that later were called ]s; the first of which had its maiden flight in 1900.<ref name="nbb" /> Regularly scheduled flights started in 1910 and by the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, they had carried 35,000 passengers without a serious incident. Hydrogen-lifted airships were used as observation platforms and bombers during the war. | |||

| The first non-stop transatlantic crossing was made by the British airship '']'' in 1919. Regular passenger service resumed in the 1920s and the discovery of ] reserves in the United States promised increased safety, but the U.S. government refused to sell the gas for this purpose. Therefore, {{chem2|H2}} was used in the ] airship, which was destroyed in a midair fire over ] on 6 May 1937.<ref name="nbb" /> The incident was broadcast live on radio and filmed. Ignition of leaking hydrogen is widely assumed to be the cause, but later investigations pointed to the ignition of the ] fabric coating by ]. But the damage to hydrogen's reputation as a ] was already done and commercial hydrogen airship travel ]. Hydrogen is still used, in preference to non-flammable but more expensive helium, as a lifting gas for ]. | |||

| ==Occurrence== | |||

| ], a giant H II region in the ].]] | |||

| ==== Deuterium and tritium ==== | |||

| Hydrogen is the most ] element in the universe, making up 75% of normal matter by ] and over 90% by number of ]s. {{ref|education.jlab.org}} This element is found in great abundance in ]s and gas giant planets. It is very rare in the ]'s atmosphere (1 ] by volume), because being the lightest gas causes it to escape Earth's gravity, though when ] are considered, it is the tenth most abundant element on Earth. The most common source for this element on Earth is ], which is composed two parts hydrogen to one part ] (H<sub>2</sub>O). Other sources include most forms of organic matter (currently all known life forms) including ], ], and other ]s. ] (]H<sub>4</sub>) is an increasingly important source of hydrogen. | |||

| ] was discovered in December 1931 by ], and ] was prepared in 1934 by ], ], and ].<ref name="Nostrand" /> ], which consists of deuterium in the place of regular hydrogen, was discovered by Urey's group in 1932.<ref name="nbb" /> | |||

| ==== Hydrogen-cooled turbogenerator ==== | |||

| Throughout the Universe, hydrogen is mostly found in the ] state whose properties are quite different to molecular hydrogen. As a plasma, hydrogen's electron and proton are not bound together, resulting in very high electrical conductivity, even when the gas is only partially ionised. The charged particles are highly influenced by magnetic and electric fields, for example, in the ] they interact with the Earth's ] giving rise to ]s and the ]. | |||

| The first ] went into service using gaseous hydrogen as a ] in the rotor and the stator in 1937 at ], Ohio, owned by the Dayton Power & Light Co.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/stream/chronologicalhis00natirich/chronologicalhis00natirich_djvu.txt|title=A chronological history of electrical development from 600 B.C|author=National Electrical Manufacturers Association|year=1946|page=102|publisher=New York, N.Y., National Electrical Manufacturers Association|access-date=9 February 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304141424/http://www.archive.org/stream/chronologicalhis00natirich/chronologicalhis00natirich_djvu.txt|archive-date=4 March 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> This was justified by the high thermal conductivity and very low viscosity of hydrogen gas, thus lower drag than air. This is the most common coolant used for generators 60 MW and larger; smaller generators are usually ]. | |||

| ==== Nickel–hydrogen battery ==== | |||

| Hydrogen can be prepared in several different ways: ] on heated ], ] decomposition with heat, reaction of a strong base in an ] with ], water ], or displacement from ]s with certain ]s. Commercial bulk hydrogen is usually produced by the ] of ]. At high temperatures (700–1100 °C), steam reacts with methane to yield ] and hydrogen. | |||

| The ] was used for the first time in 1977 aboard the U.S. Navy's Navigation technology satellite-2 (NTS-2).<ref>{{Cite journal|title=NTS-2 Nickel-Hydrogen Battery Performance 31|journal=Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets|volume=17|pages=31–34|doi=10.2514/3.57704|year=1980|last1=Stockel|first1=J.F|last2=j.d. Dunlop|last3=Betz|first3=F|bibcode=1980JSpRo..17...31S}}</ref> The ],<ref>{{cite conference|url=https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20020070612_2002115777.pdf|work=IECEC '02. 2002 37th Intersociety Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, 2002|pages=45–50|date=July 2002|access-date=11 November 2011|doi=10.1109/IECEC.2002.1391972|title=Validation of international space station electrical performance model via on-orbit telemetry|last1=Jannette|first1=A. G.|last2=Hojnicki|first2=J. S.|last3=McKissock|first3=D. B.|last4=Fincannon|first4=J.|last5=Kerslake|first5=T. W.|last6=Rodriguez|first6=C. D.|isbn=0-7803-7296-4|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100514100504/http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20020070612_2002115777.pdf|archive-date=14 May 2010|url-status=live|hdl=2060/20020070612|hdl-access=free}}</ref> ]<ref>{{cite book|doi=10.1109/AERO.2002.1035418 |date=2002|last1=Anderson|first1=P. M.|last2=Coyne|first2=J. W.|title=Proceedings, IEEE Aerospace Conference |chapter=A lightweight, high reliability, single battery power system for interplanetary spacecraft |isbn=978-0-7803-7231-3|volume=5|pages=5–2433|s2cid=108678345}}</ref> and the ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.astronautix.com/craft/marveyor.htm|title=Mars Global Surveyor|publisher=Astronautix.com|access-date=6 April 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090810180658/http://www.astronautix.com/craft/marveyor.htm|archive-date=10 August 2009}}</ref> are equipped with nickel-hydrogen batteries. In the dark part of its orbit, the ] is also powered by nickel-hydrogen batteries, which were finally replaced in May 2009,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/servicing/SM4/main/SM4_Essentials.html|title=Hubble servicing mission 4 essentials|date=7 May 2009|editor=Lori Tyahla|access-date=19 May 2015|publisher=NASA|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150313073737/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/servicing/SM4/main/SM4_Essentials.html|archive-date=13 March 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> more than 19 years after launch and 13 years beyond their design life.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/servicing/series/battery_story.html|title=Extending Hubble's mission life with new batteries|date=25 November 2008|first1=Susan|last1=Hendrix|editor=Lori Tyahla|access-date=19 May 2015|publisher=NASA|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305002850/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/servicing/series/battery_story.html|archive-date=5 March 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Role in quantum theory === | |||

| :] + ] → ] + 3 H<sub>2</sub> | |||

| ]|alt=A line spectrum showing black background with narrow lines superimposed on it: one violet, one blue, one cyan, and one red.]] | |||

| Because of its simple atomic structure, consisting only of a proton and an electron, the ], together with the spectrum of light produced from it or absorbed by it, has been central to the development of the theory of ]ic structure.<ref>{{cite book |last=Crepeau |first=R. | |||

| |title=Niels Bohr: The Atomic Model |series=Great Scientific Minds | |||

| |date=1 January 2006 |isbn=978-1-4298-0723-4 | |||

| }}</ref> Furthermore, study of the corresponding simplicity of the hydrogen molecule and the corresponding cation ] brought understanding of the nature of the ], which followed shortly after the quantum mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom had been developed in the mid-1920s. | |||

| One of the first quantum effects to be explicitly noticed (but not understood at the time) was a Maxwell observation involving hydrogen, half a century before full ] arrived. Maxwell observed that the ] of {{chem2|H2}} unaccountably departs from that of a ] gas below room temperature and begins to increasingly resemble that of a monatomic gas at cryogenic temperatures. According to quantum theory, this behavior arises from the spacing of the (quantized) rotational energy levels, which are particularly wide-spaced in {{chem2|H2}} because of its low mass. These widely spaced levels inhibit equal partition of heat energy into rotational motion in hydrogen at low temperatures. Diatomic gases composed of heavier atoms do not have such widely spaced levels and do not exhibit the same effect.<ref name="Berman">{{cite journal | |||

| Additional hydrogen can be recovered from the carbon monoxide through the ] reaction: | |||

| |last1=Berman|first1=R.|last2=Cooke|first2=A. H.|last3=Hill|first3=R. W. | |||

| |title=Cryogenics|journal=Annual Review of Physical Chemistry | |||

| |date=1956|volume=7|pages=1–20 | |||

| |doi=10.1146/annurev.pc.07.100156.000245|bibcode = 1956ARPC....7....1B }}</ref> | |||

| ] ({{physics particle|anti=yes|H}}) is the ] counterpart to hydrogen. It consists of an ] with a ]. Antihydrogen is the only type of antimatter atom to have been produced {{as of|2015|lc=y}}.<ref name="char15">{{cite journal|last1=Charlton|first1=Mike|last2=Van Der Werf|first2=Dirk Peter|title=Advances in antihydrogen physics|journal=Science Progress|date=1 March 2015|volume=98|issue=1|pages=34–62|doi=10.3184/003685015X14234978376369|pmid=25942774|pmc=10365473 |s2cid=23581065}}</ref><ref name="Keller15">{{cite journal|last1=Kellerbauer|first1=Alban|title=Why Antimatter Matters|journal=European Review|date=29 January 2015|volume=23|issue=1|pages=45–56|doi=10.1017/S1062798714000532|s2cid=58906869}}</ref> | |||