| Revision as of 01:28, 25 June 2012 view sourceAvaya1 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users28,106 edits →English translations← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:50, 21 December 2024 view source Sumangaligowda (talk | contribs)50 edits →UniversalityTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Sufi scholar and poet (1207–1273)}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{redirect|Mevlevi|other uses|Mevlevi (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Pp-semi-indef}} | {{Pp-semi-indef}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox Muslim scholar | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=September 2016}} | |||

| |notability = {{transl|fa|Mewlānā Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī}}<br />{{lang|fa|مولانا جلالالدین محمد بلخی}} | |||

| {{Infobox religious biography | |||

| |era = Medieval | |||

| | era = ] <br/> (7th ]) | |||

| |name = Jalal ad-Dīn Muhammad Rumi | |||

| | honorific-prefix = Mawlānā, Mevlânâ | |||

| |title = Mewlānā | |||

| | name = Rumi | |||

| |birth_date= 1207 A.D.<br />] (present day ]) | |||

| | native_name = {{nobold|رومی}} | |||

| |death_date= 17 December 1273 A.D.<br />] (present day ]) | |||

| | native_name_lang = fa | |||

| |ethnicity = ] | |||

| | image = مولانا اثر حسین بهزاد (cropped).jpg | |||

| |region = ] (<small>]: From his birth (1207)-1212 and 1213-17; ]: 1212-13</small>)<ref name="encyclopaedia1991">H. Ritter, 1991, ''DJALĀL al-DĪN RŪMĪ'', '']'' (Volume II: C-G), 393.</ref><ref>], 1988, </ref><br />] (<small>]: 1217-19; ]: 1219-22; ]: 1222-28; ]: 1228 until his death in 1273 AD.</small>)<ref name="encyclopaedia1991"/> | |||

| | image_size = 250px | |||

| |Religion = ] | |||

| | caption = Rumi, by Iranian artist ] (1957) | |||

| |school_tradition = ]; his followers formed the ] | |||

| | title = ''Jalaluddin'', ''jalāl al-Din'',<ref name="EI">Ritter, H.; Bausani, A. "ḎJ̲alāl al-Dīn Rūmī b. Bahāʾ al-Dīn Sulṭān al-ʿulamāʾ Walad b. Ḥusayn b. Aḥmad Ḵh̲aṭībī." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007. Brill Online. Excerpt: "known by the sobriquet Mewlānā, persian poet and founder of the Mewlewiyya order of dervishes"</ref> ''Mevlana'', ''Mawlana'' | |||

| |main_interests = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | birth_date = 30 September 1207 | |||

| |notable_ideas = ], ] and ] | |||

| | birth_place = ] (present-day ])<ref>{{Cite web |date=7 January 2024 |title=Rumi {{!}} Biography, Poems, & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rumi |access-date=28 January 2024 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> or ] (present-day ]),<ref>{{cite book |last1=Harmless |first1=William |title=Mystics |date=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-804110-8 |page=167 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8pBmFhnrVfUC&pg=PA167}}</ref><ref name="Balkh" /> ] | |||

| |works = ], ], ] | |||

| | death_date = 17 December 1273 (aged 66) | |||

| |Predecessor = ] and ] | |||

| | death_place = ] (present-day ]), ] | |||

| |influences = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | resting_place = Tomb of Mevlana Rumi, ], ], Turkey | |||

| |influenced = ], ], ] | |||

| | mother = Mo'mena Khatun | |||

| | father = Baha al-Din Valad | |||

| | spouse = Gevher Khatun, Karra Khatun | |||

| | children = ], ], Amir Alim Chelebi, Malike Khatun. | |||

| | religion = ] | |||

| | denomination = ]<ref>{{citation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1y-hxhLSWsEC&pg=PA48|title=The Complete Idiot's Guide to Rumi Meditations|year=2008|page=48|publisher=Penguin Group|isbn=9781592577361}}</ref> | |||

| | jurisprudence = ] | |||

| | creed = ]<ref>{{cite book|last=Lewis|first=Franklin D.|title=Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi|date=2014|publisher=Simon and Schuster|pages=15–16, 52, 60, 89}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Zarrinkoob|first=Abdolhossein|title=Serr-e Ney|date=2005|publisher=Instisharat-i Ilmi|volume=1|pages=447}}</ref> | |||

| | Sufi_order = ] | |||

| | notable_ideas = ], ] | |||

| | order = ] | |||

| | philosophy = ], ] | |||

| | known_for = ], Rumi Music | |||

| | pen_name = Rumi | |||

| | main_interests = ], ] jurisprudence, ] theology | |||

| | works = ], ], ] | |||

| | predecessor = ] and ] | |||

| | successor = ], ] | |||

| | influences = ], ], ], ], Muhaqqeq Termezi, ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | influenced = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]<ref>], ''In Search of the Sacred : A Conversation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr on His Life and Thought'', ] (2010), p. 141</ref> ], ], ] | |||

| | nationality = ], then ] | |||

| | home_town = ] (present-day ]) or ] present-day ] | |||

| | module = {{Infobox Arabic name|embed=yes | |||

| | laqab = Jalāl ad-Dīn<br/>{{lang|fa|جلالالدین}} | |||

| | ism = Muḥammad<br/>{{lang|fa|محمد}} | |||

| | nasab = ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn Aḥmad<br/>{{lang|ar|بن محمد بن الحسين بن أحمد}} | |||

| | nisba = ar-Rūmī<br/>{{lang|ar|الرومي}}<br/>al-Khaṭībī<br/>{{lang|ar|الخطيبي}}<br/>al-Balkhī<br/>{{lang|ar|البلخي}}<br/>al-Bakrī<br/>{{lang|ar|البكري}}}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Contains special characters|Perso-Arabic}} | |||

| '''Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī''' ({{langx|fa|جلالالدین محمّد رومی}}), or simply '''Rumi''' (30 September 1207 – 17 December 1273), was a 13th-century poet, ] '']'' (jurist), ], ] ] (''mutakallim''),<ref>Ahmad, Imtiaz. "The Place of Rumi in Muslim Thought." Islamic Quarterly 24.3 (1980): 67.</ref> and ] ] originally from ] in ].<ref name=lewis>{{cite book |first=Franklin D. |last=Lewis |title=Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi |publisher=Oneworld Publication |year=2008 |page=9 |quote=How is that a Persian boy born almost eight hundred years ago in Khorasan, the northeastern province of greater Iran, in a region that we identify today as in Central Asia, but was considered in those days as part of the greater Persian cultural sphere, wound up in central Anatolia on the receding edge of the Byzantine cultural sphere, in what is now Turkey, some 1,500 miles to the west?}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Annemarie |last=Schimmel |title=The Mystery of Numbers |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=7 April 1994 |page=51 |quote=These examples are taken from the Persian mystic Rumi's work, not from Chinese, but they express the yang-yin{{sic}} relationship with perfect lucidity.}}</ref> | |||

| '''Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī''' ({{lang-fa|جلالالدین محمد بلخى}} {{IPA-fa|dʒælɒːlæddiːn mohæmmæde bælxiː}}), also known as '''Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī''' ({{lang|fa|جلالالدین محمد رومی}} {{IPA-fa|dʒælɒːlæddiːn mohæmmæde ɾuːmiː}}) and popularly known as '''Mevlānā''' in Turkey and '''Mawlānā'''<ref name="encyclopaedia1991"/> ({{lang-fa|مولانا}} {{IPA-fa|moulɒːnɒː}}) in ] and ] but known to the English-speaking world simply as '''Rumi'''<ref name="name">NOTE: ] of the ] into English varies. One common transliteration is ''Mewlana Jalaluddin Rumi''; the usual brief reference to him is simply ''Rumi'' or ''Balkhi''. His given name, ''Jalāl ad-Dīn'', literally means "Majesty of Religion".</ref> (30 September 1207 – 17 December 1273) was a 13th-century <!--After much discussion on the talkpage and best on the mostly scholarly available sources, Persians consider him Persians, Afghans consider him an Afghan, and some Turks consider him a Turk. Misplaced Pages is not a forum, and follows strict policies of ], ], ] and ].-->]<ref name=howisit/><ref>Annemarie Schimmel, “The Mystery of Numbers”, Oxford University Press,1993. Pg 49: “A beautiful symbol of the duality that appears through creation was invented by the great Persian mystical poet Jalal al-Din Rumi, who compares God's creative word kun (written in Arabic KN) with a twisted rope of 2 threads (which in English twine, in German Zwirn¸ both words derived from the root “two”) ”.</ref><ref>Ritter, H.; Bausani, A. "ḎJ̲alāl al- Dīn Rūmī b. Bahāʾ al-Dīn Sulṭān al-ʿulamāʾ Walad b. Ḥusayn b. Aḥmad Ḵh̲aṭībī ." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007. Brill Online. Excerpt: "known by the sobriquet Mewlānā, persian poet and founder of the Mewlewiyya order of dervishes"</ref><ref>Julia Scott Meisami, Forward to Franklin Lewis, Rumi Past and Present, East and West, Oneworld Publications, 2008 (revised edition)</ref><ref> | |||

| John Renard,"Historical dictionary of Sufism", Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. pg 155: "Perhaps the most famous Sufi who is known to many Muslims even today by his title alone is the seventh/13th century Persian mystic Rumi"</ref><ref>Frederick Hadland Davis , "The Persian Mystics. Jalálu'd-Dín Rúmí", Adamant Media Corporation (November 30, 2005) , ISBN 978-1-4021-5768-4.</ref><ref>Franklin Lewis, Rumi Past and Present, East and West, Oneworld Publications, 2000. “Sultan Valad (Rumi's son) elsewhere admits that he has little knowledge of Turkish” (pg 239) “Sultan Valad (Rumi's son) did not feel confident about his command of Turkish” (pg 240)</ref><ref><small>In Persian poetry, the words Rumi, Turk, Hindu and Zangi take symbolic meaning and this has led to some confusions for those that are not familiar with Persian poetry. | |||

| Rumi's works were written mostly in ], but occasionally he also used ],<ref name="Annemarie Schimmel" /> ]<ref name="Franklin Lewis" /> and ]<ref name=Dedes1993>{{cite journal |last1=Δέδες |first1=Δ. |year=1993 |title=Ποιήματα του Μαυλανά Ρουμή |trans-title=Poems by Mowlānā Rūmī |journal=Τα Ιστορικά |volume=10 |issue=18–19 |pages=3–22}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Meyer |first1=Gustav |title=Die griechischen Verse im Rabâbnâma. |journal=Byzantinische Zeitschrift |date=1895 |volume=4 |issue=3 |doi=10.1515/byzs.1895.4.3.401 |s2cid=191615267}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tlg.uci.edu/~opoudjis/Play/rumiwalad.html|title=Greek Verses of Rumi & Sultan Walad|website=uci.edu|date=22 April 2009|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://archive.today/20120805175317/http://www.tlg.uci.edu/~opoudjis/Play/rumiwalad.html|archive-date=5 August 2012}}</ref> in his verse. His '']'' (''Mathnawi''), composed in ], is considered one of the greatest poems of the Persian language.<ref>{{cite book |first=Louis |last=Gardet |chapter=Religion and Culture |title=The Cambridge History of Islam, Part VIII: Islamic Society and Civilization |editor-first=P.M. |editor-last=Holt |editor2-first=Ann K.S. |editor2-last=Lambton |editor3-first=Bernard |editor3-last=Lewis |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1977 |page=586 |quote=It is sufficient to mention ], Farid al-Din 'Attar and Sa'adi, and above all Jalal al-Din Rumi, whose Mathnawi remains one of the purest literary glories of Persia}}</ref><ref name="C.E. Bosworth p. 391">C.E. Bosworth, "Turkmen Expansion towards the west" in UNESCO History of Humanity, Volume IV, titled "From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century", UNESCO Publishing / Routledge, p. 391: "While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuk rulers (Qubād, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkmen must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time). The process of Persianization accelerated in the 13th century with the presence in Konya of two of the most distinguished refugees fleeing before the Mongols, Bahā' al-Dīn Walad and his son Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, whose Mathnawī, composed in Konya, constitutes one of the crowning glories of classical Persian literature."</ref> Rumi's influence has transcended national borders and ethnic divisions: ], ], ], ], ], ], ], as well as Muslims of the ] have greatly appreciated his spiritual legacy for the past seven centuries.<ref name="hurriyetdailynews.com">{{cite web | url=https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/rumi-work-translated-into-kurdish-77675 | title=Rumi work translated into Kurdish|website=Hürriyet Daily News | date=30 January 2015 }}</ref><ref name="Nasr1">{{cite book |last=Seyyed |first=Hossein Nasr |title=Islamic Art and Spirituality |publisher=Suny Press |year=1987 |page=115 |quote=Jalal al-Din was born in a major center of Persian culture, Balkh, from Persian speaking parents, and is the product of that Islamic Persian culture which in the 7th/13th century dominated the 'whole of the eastern lands of Islam and to which present day Persians as well as Turks, Afghans, Central Asian Muslims and the Muslims of the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent are heir. It is precisely in this world that the sun of his spiritual legacy has shone most brillianty during the past seven centuries. The father of Jalal al-Din, Muhammad ibn Husayn Khatibi, known as Baha al-Din Walad and entitled Sultan al-'ulama', was an outstanding Sufi in Balkh connected to the spiritual lineage of Najm al-Din Kubra.}}</ref> His poetry influenced not only ], but also the literary traditions of the ], ], ], ], ], and ] languages.<ref name="hurriyetdailynews.com"/><ref>{{Cite news |last=Rahman |first=Aziz |date=27 August 2015 |title=Nazrul: The rebel and the romantic |work=Daily Sun |url=http://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/70741/Nazrul:-The-rebel-and-the-romantic |url-status=dead |access-date=12 July 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170417122146/http://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/70741/Nazrul:-The-rebel-and-the-romantic |archive-date=17 April 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/339651/A-tribute-to-Jalaluddin-Rumi|newspaper=Daily Sun|last=Khan|first= Mahmudur Rahman|date=30 September 2018|title=A tribute to Jalaluddin Rumi}}</ref> | |||

| See for example: | |||

| Annemarie Schimmel. “Turk and Hindu; a literary symbol”. Acta Iranica, 1, III, 1974, pp.243-248 | |||

| Annemarie Schimmel. “A Two-Colored Brocade: The Imagery of Persian Poetry”, the imagery of Persian poetry. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. (pg 137-144). | |||

| J.T.P. de Brujin, Hindi in Encyclopedia Iranica "In such imagery the link to ethnic characteristics is hardly relevant" | |||

| Cemal Kafadar, "A rome of one's own: reflection on cultural geography and identity in the lands of Rum" in Sibel Bozdogan (Editor), Gulru Necipoglu (Editor), Julia Bailey (Editor) , "History and Ideology: Architectural Heritage of the "Lands of Rum" (Muqarnas), Brill Academic Publishers (November 1, 2007. p23: "Golpiranli rightly insists that ethnonym were deployed allegorically and metaphortically in classical Islamic literatures, which operated on the basis of a staple set of images and their well recognized contextual associations by readers; there, "turk" had both a negativeand positive connocation. In fact, the two dimensions could be blended: the "Turk" was "cruel" and hence, at the same time, the "beautiful beloved". | |||

| Rumi's works are widely read today in their original language across ] and the Persian-speaking world.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.rferl.org/content/Interview_Many_Americans_Love_RumiBut_They_Prefer_He_Not_Be_Muslim/2122973.html|title=Interview: 'Many Americans Love Rumi...But They Prefer He Not Be Muslim'|date=9 August 2010|newspaper=RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty|language=en|access-date=22 August 2016}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/LH14Ak01.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100816123932/http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/LH14Ak01.html|url-status=unfit|archive-date=16 August 2010|title=Interview: A mystical journey with Rumi|website=Asia Times|access-date=22 August 2016}}</ref> His poems have subsequently been translated into many of the world's languages and transposed into various formats. Rumi has been described as the "most popular poet",<ref name="BBC-Haviland">{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7016090.stm|title=The roar of Rumi—800 years on|first=Charles |last=Haviland|work=BBC News|date=30 September 2007|access-date=30 September 2007}}</ref> is very popular in ], ] and ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.omifacsimiles.com/brochures/divan.html|title=Dîvân-i Kebîr Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī|website=OMI – Old Manuscripts & Incunabula|access-date=22 August 2016}}</ref> | |||

| As an example, Rumi compares himself to a ], ], ] and etc. | |||

| and has become the "best selling poet" in the United States.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140414-americas-best-selling-poet|title=Why is Rumi the best-selling poet in the US?|last=Ciabattari| work=BBC News | first=Jane|date=21 October 2014|access-date=22 August 2016}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,356133,00.html|title=Rumi Rules!|last=Tompkins|first=Ptolemy|date=29 October 2002|newspaper=Time|issn=0040-781X|access-date=22 August 2016}}</ref> | |||

| A) | |||

| تو ماه ِ ترکي و من اگر ترک نيستم، | |||

| دانم من اين قَدَر که به ترکي است، آب سُو | |||

| “You are a Turkish moon, and I, although I am not a Turk, know this much, | |||

| that in Turkish the word for water is su” (Schimmel, Triumphal Sun, 196) | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| B) | |||

| He is most commonly called ''Rumi'' in English. His full name is given by his contemporary Sipahsalar as ''Muhammad bin Muhammad bin al-Husayn al-Khatibi al-Balkhi al-Bakri'' ({{langx|ar| محمد بن محمد بن الحسين الخطيبي البلخي البكري}}).<ref>{{Cite book| last = Sipahsalar| first = Faridun bin Ahmad | title = Risala-yi Ahwal-i Mawlana | date = 1946| page=5| editor = Sa'id Nafisi| location = Tehran | url = https://archive.org/details/RisalaEFaridunBinAhmadSipahsalarDarAhwalEMaulanaJalaluddinMaulaviFarsi/page/n17/mode/2up?view=theater}}</ref> He is more commonly known as ''Molānā Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī'' ({{lang|fa|مولانا جلالالدین محمد رومی}}). ''Jalal ad-Din'' is an ] name meaning "Glory of the Faith". ''Balkhī'' and ''Rūmī'' are his '']'', meaning, respectively, "from ]" and "from ]", as he was from the Sultanate of Rûm in ].<ref>{{cite book|author=Rumi|title=Selected Poems |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rKbpCAAAQBAJ&pg=PT350 |year=2015 |publisher=Penguin Books|isbn=978-0-14-196911-4|page=350}}</ref> | |||

| “Everyone in whose heart is the love for Tabriz | |||

| Becomes – even though he be a Hindu – a rose-cheeked inhabitant of Taraz (i.e. a Turk) ” (Schimmel, Triumphal Sun, 196) | |||

| C) | |||

| {{lang|fa|2= | |||

| گه ترکم و گه هندو گه رومی و گه زنگی | |||

| از نقش تو است ای جان اقرارم و انکارم | |||

| }} | |||

| “I am sometimes Turk and sometimes Hindu, sometimes Rumi and sometimes Negro” | |||

| O soul, from your image in my approval and my denial” (Schimmel, Triumphal Sun, 196) | |||

| According to the authoritative Rumi biographer ] of the ], "he Anatolian peninsula which had belonged to the Byzantine, or eastern Roman empire, had only relatively recently been conquered by Muslims and even when it came to be controlled by Turkish Muslim rulers, it was still known to Arabs, Persians and Turks as the geographical area of Rum. As such, there are a number of historical personages born in or associated with Anatolia known as Rumi, a word borrowed from Persian literally meaning 'Roman,' in which context Roman refers to subjects of the ] or simply to people living in or things associated with ]."<ref>{{cite book|first=Franklin |last=Lewis|title=Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings and Poetry of Jalal al-Din Rumi|publisher= One World Publication Limited|year= 2008|page= 9}}</ref> He was also known as "Mullah of Rum" ({{lang|fa|ملای روم}} ''mullā-yi Rūm'' or {{lang|fa|ملای رومی}} ''mullā-yi Rūmī'').<ref> in '']''</ref> | |||

| For the general meaning of the usage of these terms see: | |||

| Annemarie Schimmel. “Turk and Hindu; a literary symbol”. Acta Iranica, 1, III, 1974, pp.243-248 | |||

| Annemarie Schimmel. “A Two-Colored Brocade: The Imagery of Persian Poetry”, the imagery of Persian poetry.</ref> ] ], ], ], and ] ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Islamica Magazine: Mewlana Rumi and Islamic Spirituality| url=http://www.islamicamagazine.com/issue-13/mawlana-jalal-al-din-rumi-and-islamic-spirituality.html| accessdate=2007-11-10 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20071114060149/http://www.islamicamagazine.com/issue-13/mawlana-jalal-al-din-rumi-and-islamic-spirituality.html |archivedate = 2007-11-14}}</ref> ''Rūmī'' is a descriptive name meaning "Roman" since he lived most of his life in an area called "]" (then under the control of ]) because it was once ruled by the ].<ref>Schwartz, Stephen (May 14, 2007) ''Weekly Standard''.</ref> He was one of the figures who flourished in the ].<ref>Alexēs G. K. Savvidēs, Byzantium in the Near East: Its Relations with the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum in Asia Minor, The Armenians of Cilicia and The Mongols, A.D. c. 1192-1237'', Kentron Vyzantinōn Ereunōn, 1981, </ref> | |||

| Rumi is widely known by the ] ''Mawlānā''/''Molānā''<ref name="EI" /><ref name="encyclopaedia1991">H. Ritter, 1991, ''DJALĀL al-DĪN RŪMĪ'', '']'' (Volume II: C–G), 393.</ref> ({{langx|fa|مولانا}} {{IPA|fa|moulɒːnɒ}}) in ] and popularly known as {{lang|tr|Mevlânâ}} in Turkey. ''Mawlānā'' ({{lang|ar|مولانا|rtl=yes}}) is a term of ] origin, meaning "our master". The term {{lang|fa|مولوی}} ''Mawlawī''/''Mowlavi'' (Persian) and {{lang|tr|Mevlevi}} (Turkish), also of Arabic origin, meaning "my master", is also frequently used for him.<ref>Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (Maulana), Ibrahim Gamard, ''Rumi and Islam: Selections from His Stories, Poems, and Discourses, Annotated & Explained'', SkyLight Paths Publishing, 2004.</ref> | |||

| It is likely that he was born in the village of ],<ref name="Balkh">], "I Am Wind, You Are Fire," p. 11. She refers to a 1989 article by the German scholar, Fritz Meier:{{Quote|Tajiks and Persian admirers still prefer to call Jalaluddin 'Balkhi' because his family lived in Balkh, current day in ] before migrating westward. However, their home was not in the actual city of Balkh, since the mid-eighth century a center of Muslim culture in (Greater) Khorasan (Iran and Central Asia). Rather, as the Swiss scholar Fritz Meier has shown, it was in the small town of Wakhsh north of the Oxus that Baha'uddin Walad, Jalaluddin's father, lived and worked as a jurist and preacher with mystical inclinations. Franklin Lewis, ''Rumi Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi'', 2000, pp. 47–49.}} Professor Lewis has devoted two pages of his book to the topic of Wakhsh, which he states has been identified with the medieval town of Lêwkand (or Lâvakand) or Sangtude, which is about 65 kilometers southeast of Dushanbe, the capital of present-day Tajikistan. He says it is on the east bank of the Vakhshâb river, a major tributary that joins the Amu Daryâ river (also called Jayhun, and named the Oxus by the Greeks). He further states: "Bahâ al-Din may have been born in Balkh, but at least between June 1204 and 1210 (Shavvâl 600 and 607), during which time Rumi was born, Bahâ al-Din resided in a house in Vakhsh (Bah 2:143 book, "Ma`ârif."). Vakhsh, rather than Balkh was the permanent base of Bahâ al-Din and his family until Rumi was around five years old (mei 16-35) . At that time, in about the year 1212 (A.H. 608–609), the Valads moved to Samarqand (Fih 333; Mei 29–30, 36) , leaving behind Baâ al-Din's mother, who must have been at least seventy-five years old."</ref> a small town located at the river ] in ] (in what is now ]). Wakhsh belonged to the larger province of Balkh, and in the year Rumi was born, his father was an appointed scholar there.<ref name="Balkh" /> Both these cities were at the time included in the greater Persian cultural sphere of ], the easternmost province of ]<ref name=howisit>Franklin Lewis, Rumi Past and Present, East and West, Oneworld Publications, 2000.{{Quote|How is it that a Persian boy born almost eight hundred years ago in Khorasan, the northeastern province of greater Iran, in a region that we identify today as Central Asia, but was considered in those days as part of the Greater Persian cultural sphere, wound up in Central Anatolia on the receding edge of the Byzantine cultural sphere, in which is now Turkey}}</ref> and was part of the ]. | |||

| ==Life== | |||

| His birthplace<ref name=howisit/> and native language<ref>Annemarie Schimmel, The Triumphal Sun: A Study of the Works of Jalaloddin Rumi, SUNY Press, 1993, p. 193: "Rumi's mother tongue was Persian, but he had learned during his stay in Konya, enough Turkish and Greek to use it, now and then, in his verse"</ref> both indicate a Persian heritage.<ref>Franklin D. Lewis, "Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal ad-Din Rumi", Oneworld Publication Limited, 2008. Professor of Persian literature Franklin Lewis while criticizing the Turkish Ministry of Culture and a book by Mehmet Onder writes about Onder's book. pg 549: "Therefore, we can only surmise about his cultural jingoism represents a conscious effort to rob Rumi of his Persian and Iranian heritage, and claim for Turkish literature, ethnicity and nationalism". On the claim that his native tongue was Turkish, Professor Franklin writes on page pg 21:"On the question of Rumi's multilingualism (pages 315-317), we still say that he spoke and wrote Persian as a native language, whote and conversed in Arabic as a learned "foreign" language, could at least get by at the market in Turkish and Greek." On Rumi's background and Persian cultural sphere which he came from, he writes pg 9: "How is that a Pesian boy born almost eight hundred years ago in Khorasan, the northeastern province of greater Iran, in a region that we identify today as Central Asia, but was considered in those days as part of the greater Persian cultural sphere, wound up in central Anatolia on the receding edge of the Byzantine cultural sphere"</ref> His father decided to migrate westwards due to quarrels between different dynasties in Khorasan, opposition to the Khwarizmid Shahs, who were considered deviant by Bahā ad-Dīn Walad,<ref>Franklin Lewis, Rumi Past and Present, East and West, Oneworld Publications, 2000. Chap1</ref> or fear of the impending Mongol cataclysm.<ref>Encyclopedia Iranica, "Baha ad-Din Mohammad Walad" , H. Algar. {{dead link|date=October 2011}}</ref> Rumi's family traveled west, first performing the ] and eventually settling in the Anatolian city ] (capital of the ], in present-day ]). This was where he lived most of his life, and here he composed one of the crowning glories of ] which profoundly affected the culture of the area.<ref>C.E. Bosworth, "Turkish Expansion towards the west" in UNESCO HISTORY OF HUMANITY, Volume IV, titled "From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century", UNESCO Publishing / Routledge, 2000. p. 391: "While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuq Rulers (Qubad, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkish must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time). The process of Persianization accelerated in the thirteenth century with the presence in Konya of two of the most distinguished refugees fleeing before the Mongols, Baha al-din Walad and his son Mewlana Jalal al-din Balkhi Rumi, whose Mathnawi, composed in Konya, constitutes one of the crowning glories of classical Persian literature."</ref> | |||

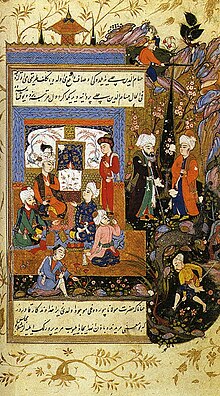

| ] mystics]] | |||

| ===Overview=== | |||

| He lived most of his life under the Sultanate of Rum, where he produced his works<ref>], ''Rumi: The Book of Love: Poems of Ecstasy and Longing'', HarperCollins, 2005, p. xxv, ISBN 978-0-06-075050-3</ref> and died in 1273 AD. He was buried in Konya and his shrine became a place of pilgrimage.<ref>Note: Rumi's shrine is now known as the ''Mevlana Museum'' in Turkey</ref> Following his death, his followers and his son ] founded the ], also known as the Order of the Whirling Dervishes, famous for its ] known as the ] ceremony. | |||

| Rumi was born to Persian parents,<ref>{{Citation |last=Yalman |first=Suzan |title=Badr al-Dīn Tabrīzī |date=7 July 2016 |url=https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/badr-al-din-tabrizi-COM_25104?s.num=7&s.f.s2_parent=s.f.book.encyclopaedia-of-islam-3&s.q=rumi+jalal+al+din |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia of Islam THREE |access-date=7 June 2023 |publisher=Brill |language=en|quote='''Badr ''al''-''Dīn'' Tabrīzī''' was the architect of the original tomb built for Mawlānā ''Jalāl'' ''al''-''Dīn'' ''Rūmī'' (d. 672/1273, in Konya), the great Persian mystic and poet.}}</ref><ref name="Annemarie Schimmel">Annemarie Schimmel, The Triumphal Sun: A Study of the Works of Jalaloddin Rumi, SUNY Press, 1993, p. 193: "Rumi's mother tongue was Persian, but he had learned during his stay in Konya, enough Turkish and Greek to use it, now and then, in his verse."</ref><ref name="Franklin Lewis">Lewis, Franklin: "On the question of Rumi's multilingualism (pp. 315–317), we may still say that he spoke and wrote in Persian as a native language, wrote and conversed in Arabic as a learned "foreign" language and could at least get by at the market in Turkish and Greek (although some wildly extravagant claims have been made about his command of Attic Greek, or his native tongue being Turkish) (Lewis 2008:xxi). (Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings and Poetry of Jalal al-Din Rumi'', 2008). Lewis also points out that: "Living among Turks, Rumi also picked up some colloquial Turkish." (Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings and Poetry of Jalal al-Din Rumi'', 2008, p. 315). He also mentions Rumi composed thirteen lines in Greek (Franklin Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings and Poetry of Jalal al-Din Rumi'', One World Publication Limited, 2008, p. 316). On Rumi's son, Sultan Walad, Lewis mentions: "] elsewhere admits that he has little knowledge of Turkish" (Sultan Walad): Lewis, ''Rumi, "Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings and Poetry of Jalal al-Din Rumi'', One World Publication Limited, 2008, p. 239) and "Sultan Valad did not feel confident about his command of Turkish" (Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West'', 2000, p. 240)</ref><ref name="Nasr2">Seyyed Hossein Nasr, ''Islamic Art and Spirituality'', SUNY Press, 1987. p. 115: "Jalal al-Din was born in a major center of Persian culture, Balkh, from Persian speaking parents, and is the product of that Islamic Persian culture which in the 7th/13th century dominated the 'whole of the eastern lands of Islam and to which present day Persians as well as Turks, Afghans, Central Asian Muslims and the Muslims of the Indo-Pakistani and the Muslims of the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent are heir. It is precisely in this world that the sun of his spiritual legacy has shone most brilliantly during the past seven centuries. The father of Jalal al-Din, Muhammad ibn Husayn Khatibi, known as ] and entitled Sultan al-'ulama', was an outstanding Sufi in Balkh connected to the spiritual lineage of ]."</ref> in ],<ref>Lewis: ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West. The Life Teachings and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi''. One World Publications, Oxford, 2000, S. 47.</ref> modern-day ] or ],<ref name="Balkh">], "I Am Wind, You Are Fire," p. 11. She refers to a 1989 article by ]:{{Blockquote|Tajiks and Persian admirers still prefer to call Jalaluddin 'Balkhi' because his family lived in Balkh, current day in ] before migrating westward. However, their home was not in the actual city of Balkh, since the mid-eighth century a center of Muslim culture in (Greater) Khorasan (Iran and Central Asia). Rather, as Meier has shown, it was in the small town of Wakhsh north of the Oxus that Baha'uddin Walad, Jalaluddin's father, lived and worked as a jurist and preacher with mystical inclinations. Lewis, ''Rumi : Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teachings, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi'', 2000, pp. 47–49.}} Lewis has devoted two pages of his book to the topic of Wakhsh, which he states has been identified with the medieval town of Lêwkand (or Lâvakand) or Sangtude, which is about 65 kilometers southeast of Dushanbe, the capital of present-day Tajikistan. He says it is on the east bank of the Vakhshâb river, a major tributary that joins the Amu Daryâ river (also called Jayhun, and named the Oxus by the Greeks). He further states: "Bahâ al-Din may have been born in Balkh, but at least between June 1204 and 1210 (Shavvâl 600 and 607), during which time Rumi was born, Bahâ al-Din resided in a house in Vakhsh (Bah 2:143 book, "Ma`ârif."). Vakhsh, rather than Balkh was the permanent base of Bahâ al-Din and his family until Rumi was around five years old (mei 16–35) . At that time, in about the year 1212 (A.H. 608–609), the Walads moved to Samarqand (Fih 333; Mei 29–30, 36) , leaving behind Baâ al-Din's mother, who must have been at least seventy-five years old."</ref> a village on the East bank of the ] known as ] in present-day ].<ref name="Balkh" /> The area, culturally adjacent to ], is where Mawlânâ's father, Bahâ' uddîn Walad, was a preacher and jurist.<ref name="Balkh" /> He lived and worked there until 1212, when Rumi was aged around five and the family moved to ].<ref name="Balkh" /> | |||

| Greater Balkh was at that time a major centre of Persian culture<ref name="C.E. Bosworth p. 391" /><ref name="Nasr2" /><ref>Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The life, Teaching and poetry of Jalal Al-Din Rumi'', Oneworld Publication Limited, 2008 p. 9: "How is that a Persian boy born almost eight hundred years ago in Khorasan, the northeastern province of greater Iran, in a region that we identify today as Central Asia, but was considered in those days as part of the greater Persian cultural sphere, wound up in central Anatolia on the receding edge of the Byzantine cultural sphere"</ref> and ] had developed there for several centuries. The most important influences upon Rumi, besides his father, were the Persian poets ] and ].<ref>Jafri, Maqsood, ''The gleam of wisdom'', Sigma Press, 2003. p. 238: "Rumi has influenced a large number of writers while on the other hand he himself was under the great influence of Sanai and Attar.</ref> Rumi expresses his appreciation: "Attar was the spirit, Sanai his eyes twain, And in time thereafter, Came we in their train"<ref>Arberry, A. J., ''Sufism: An Account of the Mystics of Islam'', Courier Dover Publications, November 9, 2001. p. 141.</ref> and mentions in another poem: "Attar has traversed the seven cities of Love, We are still at the turn of one street".<ref>Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, ''The Garden of Truth: The Vision and Promise of Sufism, Islam's Mystical Tradition'', HarperCollins, 2 September 2008. p. 130: "Attar has traversed the seven cities of Love, We are still at the turn of one street!"</ref> His father was also connected to the spiritual lineage of ].<ref name="Nasr1" /> | |||

| Rumi's works are written in the ] language. A Persian literary renaissance (in the 8th/9th century) started in regions of ], ] and ]<ref>Lazard, Gilbert "The Rise of the New Persian Language", in Frye, R. N., ''The Cambridge History of Iran'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, Vol. 4, pp. 595–632. (Lapidus, Ira, 2002, A Brief History of Islamic Societies, "Under Arab rule, Arabic became the principal language for administration and religion. The substitution of Arabic for Middle Persian was facilitated by the translation of Persian classics into Arabic. Arabic became the main vehicle of Persian high culture, and remained such will into the eleventh century. Parsi declined and was kept alive mainly by the Zoroastrian priesthood in western Iran. The Arab conquests however, helped make Persian rather than Arabic the most common spoken language in Khurasan and the lands beyond the Oxus River. Paradoxically, Arab and Islamic domination created a Persian cultural region in areas never before unified by Persian speech. A new Persian evolved out of this complex linguistic situation. In the ninth century the Tahirid governors of Khurasan began to have the old Persian language written in Arabic script rather than in pahlavi characters. At the same time, eastern lords in the small principalities began to patronize a local court poetry in an elevated form of Persian. The new poetry was inspired by Arabic verse forms, so that Iranian patrons who did not understand Arabic could comprehend and enjoy the presentation of an elevated and dignified poetry in the manner of Baghdad. This new poetry flourished in regions where the influence of Abbasid Arabic culture was attenuated and where it had no competition from the surviving tradition of Middle Persian literary classics cultivated for religious purposes as in Western Iran." "In the western regions, including Iraq, Syria and Egypt, and the lands of the far Islamic west including North Africa and Spain, Arabic became the predominant language of both high literary culture and spoken discourse." pp. 125–132, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.)</ref> and by the 10th/11th century, it reinforced the ] as the preferred literary and cultural language in the Persian Islamic world. Rumi's importance is considered to transcend national and ethnic borders. His original works are widely read in their original language across the Persian-speaking world. Translations of his works are very popular in other countries. His poetry has influenced ] as well as ], ] and other Pakistani languages written in Perso/Arabic script e.g. ] and ]. His poems have been widely translated into many of the world's languages and transposed into various formats. In 2007, he was described as the "most popular poet in America."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7016090.stm|title=The roar of Rumi - 800 years on|author=Charles Haviland|publisher=BBC News|date=2007-09-30|accessdate=2007-09-30}}</ref> | |||

| Rumi lived most of his life under the ]<ref>Grousset, Rene, ''The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia'', (Rutgers University Press, 2002), 157; "...the Seljuk court at Konya adopted Persian as its official language".</ref><ref>Aḥmad of Niǧde's "al-Walad al-Shafīq" and the Seljuk Past, A.C.S. Peacock, Anatolian Studies, Vol. 54, (2004), 97; With the growth of Seljuk power in Rum, a more highly developed Muslim cultural life, based on the Persianate culture of the Great Seljuk court, was able to take root in Anatolia</ref><ref>Findley, Carter Vaughn, ''The Turks in World History'', Oxford University Press, 11 November 2004. p. 72: Meanwhile, amid the migratory swarm that Turkified Anatolia, the dispersion of learned men from the Persian-speaking east paradoxically made the Seljuks court at Konya a new center for Persian court culture, as exemplified by the great mystical poet Jelaleddin Rumi (1207–1273).</ref> ] ], where he produced his works<ref>], ''Rumi: The Book of Love: Poems of Ecstasy and Longing'', HarperCollins, 2005, p. xxv, {{ISBN|978-0-06-075050-3}}.</ref> and died in 1273{{nbsp}}AD. He was buried in ], and his shrine became a place of pilgrimage.<ref>Note: Rumi's shrine is now known as the "Mevlâna Museum" in Turkey.</ref> Upon his death, his followers and his son ] founded the ], also known as the Order of the Whirling Dervishes, famous for the ] known as the ] ceremony. He was laid to rest beside his father, and over his remains a shrine was erected. A hagiographical account of him is described in Shams ud-Din Ahmad Aflāki's ''Manāqib ul-Ārifīn'' (written between 1318 and 1353). This biography needs to be treated with care as it contains both legends and facts about Rumi.<ref name=howisit>Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West'', Oneworld Publications, 2000.{{Blockquote|How is it that a Persian boy born almost eight hundred years ago in Khorasan, the northeastern province of greater Iran, in a region that we identify today as Central Asia, but was considered in those days as part of the Greater Persian cultural sphere, wound up in Central Anatolia on the receding edge of the Byzantine cultural sphere, in which is now Turkey}}</ref> For example, Professor ] of the University of Chicago, author of the most complete biography on Rumi, has separate sections for the ] biography of Rumi and the actual biography about him.<ref name="hagiographer1" /> | |||

| ==Life== | |||

| ] mystics.]] | |||

| Rumi was probably born on 30 September 1207 in the province of ] in the district of Wakhsh<ref name="Balkh" /> in Khorasan (now in modern Afghanistan/Tajikistan). He died on 17 December 1273 in ] in ] Rum (now modern Turkey). He was laid to rest beside his father, and over his remains a splendid shrine was erected. A hagiographical account of him is described in Shams ud-Din Ahmad Aflāki's ''Manāqib ul-Ārifīn'' (written between 1318 and 1353). This hagiographical account of his biography needs to be treated with care as it contains both legends and facts about Rumi.<ref name=howisit/> For example, Professor ], ], in the most complete biography on Rumi has a separate section for the hagiographical biography on Rumi and actual biography about him.<ref name="hagiographer1"/> | |||

| ===Childhood and emigration=== | |||

| Rumi's father was Bahā ud-Dīn Walad, a theologian, jurist and a ] from Wakhsh, who was also known by the followers of Rumi as Sultan al-Ulama or "Sultan of the Scholars". The popular hagiographer assertions that have claimed the family's descent from the Caliph ] does not hold on closer examination and is rejected by modern scholars.<ref name="hagiographer1">Franklin Lewis, Rumi Past and Present, East and West, Oneworld Publications, 2008 (revised edition). pp 90-92:"Baha al-Din’s disciples also traced his family lineage to the first caliph, Abu Bakr (Sep 9; Af 7; JNO 457; Dow 213). This probably stems from willful confusion over his paternal great grandmother, who was the daughter of Abu Bakr of Sarakhs, a noted jurist (d. 1090). The most complete genealogy offered for family stretches back only six or seven generations and cannot reach to Abu Bakr, the companion and first caliph of the Prophet, who died two years after the Prophet, in A.D. 634 (FB 5-6 n.3)."</ref><ref name="hagiographer2">H. Algar, “BAHĀʾ-AL-DĪN MOḤAMMAD WALAD “ , Encyclopedia Iranica. There is no reference to such descent in the works of Bahāʾ-e Walad and Mawlānā Jalāl-al-Dīn or in the inscriptions on their sarcophagi. The attribution may have arisen from confusion between the caliph and another Abū Bakr, Šams-al-Aʾemma Abū Bakr Saraḵsī (d. 483/1090), the well-known Hanafite jurist, whose daughter, Ferdows Ḵātūn, was the mother of Aḥmad Ḵaṭīb, Bahāʾ-e Walad’s grandfather (see Forūzānfar, Resāla, p. 6). Tradition also links Bahāʾ-e Walad’s lineage to the Ḵᵛārazmšāh dynasty. His mother is said to have been the daughter of ʿAlāʾ-al-Dīn Moḥammad Ḵārazmšāh (d. 596/1200), but this appears to be excluded for chronological reasons (Forūzānfar, Resāla, p. 7) {{dead link|date=October 2011}}</ref><ref name="hagiographer3">(Ritter, H.; Bausani, A. "ḎJalāl al- Dīn Rūmī b. Bahāʾ al-Dīn Sulṭān al-ʿulamāʾ Walad b. Ḥusayn b. Aḥmad Ḵhaṭībī ." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2009. Brill Online. Excerpt: "known by the sobriquet Mawlānā (Mevlânâ), Persian poet and founder of the Mawlawiyya order of dervishes"):"The assertions that his family tree goes back to Abū Bakr, and that his mother was a daughter of the Ḵhwārizmshāh ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Muḥammad (Aflākī, i, 8-9) do not hold on closer examination (B. Furūzānfarr, Mawlānā Ḏjalāl Dīn , Tehrān 1315, 7; ʿAlīnaḳī Sharīʿatmadārī, Naḳd-i matn-i mathnawī, in Yaghmā , xii (1338), 164; Aḥmad Aflākī, Ariflerin menkibeleri, trans. Tahsin Yazıcı, Ankara 1953, i, Önsöz, 44).")</ref> The claim of maternal descent from the ] for Rumi or his father is also seen as a non-historical hagiographical tradition designed to connect the family with royalty, but this claim is rejected for chronological and historical reasons.<ref name="hagiographer1"/><ref name="hagiographer2"/><ref name="hagiographer3"/> The most complete genealogy offered for the family stretches back to six or seven generations to famous Hanafi Jurists.<ref name="hagiographer1"/><ref name="hagiographer2"/><ref name="hagiographer3"/> | |||

| Rumi's father was Bahā ud-Dīn Walad, a theologian, jurist and a ] from Wakhsh,<ref name="Balkh" /> who was also known by the followers of Rumi as Sultan al-Ulama or "Sultan of the Scholars". According to Sultan Walad's ''Ibadetname'' and Shamsuddin Aflaki (c.1286 to 1291), Rumi was a descendant of ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Fundamentals Of Rumis Thought|first=Sefik |last=Can|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FQ9RCwAAQBAJ&q=aflaki+rumi+abu+bakr&pg=PT36|year=2006|publisher=Tughra Books|isbn = 9781597846134}}</ref> Some modern scholars, however, reject this claim and state it does not hold on closer examination. The claim of maternal descent from the ] for Rumi or his father is also seen as a non-historical hagiographical tradition designed to connect the family with royalty, but this claim is rejected for chronological and historical reasons. The most complete genealogy offered for the family stretches back to six or seven generations to famous Hanafi jurists.<ref name="hagiographer1">Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West'', Oneworld Publications, 2008 (revised edition), pp. 90–92: "Baha al-Din’s disciples also traced his family lineage to the first caliph, Abu Bakr (Sep 9; Af 7; JNO 457; Dow 213). This probably stems from willful confusion over his paternal great grandmother, who was the daughter of Abu Bakr of Sarakhs, a noted jurist (d. 1090). The most complete genealogy offered for family stretches back only six or seven generations and cannot reach to Abu Bakr, the companion and first caliph of the Prophet, who died two years after the Prophet, in C.E. 634 (FB 5–6 n.3)."</ref><ref name="hagiographer2">Algar, H., , ''Encyclopedia Iranica''. There is no reference to such descent in the works of Bahāʾ-e Walad and Mawlānā Jalāl-al-Dīn or in the inscriptions on their sarcophagi. The attribution may have arisen from confusion between the caliph and another Abū Bakr, Šams-al-Aʾemma Abū Bakr Saraḵsī (d. 483/1090), the well-known Hanafite jurist, whose daughter, Ferdows Ḵātūn, was the mother of Aḥmad Ḵaṭīb, Bahāʾ-e Walad's grandfather (see Forūzānfar, Resāla, p. 6). Tradition also links Bahāʾ-e Walad's lineage to the Ḵᵛārazmšāh{{typo help inline|date=June 2022}} dynasty. His mother is said to have been the daughter of ʿAlāʾ-al-Dīn Moḥammad Ḵārazmšāh{{typo help inline|date=June 2022}} (d. 596/1200), but this appears to be excluded for chronological reasons (Forūzānfar, Resāla, p. 7).</ref><ref name="hagiographer3">(Ritter, H.; Bausani, A. "ḎJalāl al- Dīn Rūmī b. Bahāʾ al-Dīn Sulṭān al-ʿulamāʾ Walad b. Ḥusayn b. Aḥmad Ḵhaṭībī". ''Encyclopaedia of Islam''. Edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2009. Brill Online. Excerpt: "known by the sobriquet Mawlānā (Mevlâna), Persian poet and founder of the Mawlawiyya order of dervishes"): "The assertions that his family tree goes back to Abū Bakr, and that his mother was a daughter of the Ḵhwārizmshāh ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Muḥammad (Aflākī, i, 8–9) do not hold on closer examination (B. Furūzānfarr, Mawlānā Ḏjalāl Dīn, Tehrān 1315, 7; ʿAlīnaḳī Sharīʿatmadārī, Naḳd-i matn-i mathnawī, in Yaghmā, xii (1338), 164; Aḥmad Aflākī, Ariflerin menkibeleri, trans. Tahsin Yazıcı, Ankara 1953, i, Önsöz, 44).").</ref> | |||

| We do not learn the name of Baha al-Din's mother in the sources, |

We do not learn the name of Baha al-Din's mother in the sources, only that he referred to her as "Māmi" (colloquial Persian for Māma),<ref name="hagiographer4">Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West'', Oneworld Publications, 2008 (revised edition). p. 44: "Baha al-Din’s father, Hosayn, had been a religious scholar with a bent for asceticism, occupied like his own father before him, Ahmad, with the family profession of preacher (khatib). Of the four canonical schools of Sunni Islam, the family adhered to the relatively liberal ] ]. Hosayn-e Khatibi enjoyed such renown in his youth—so says Aflaki with characteristic exaggeration—that Razi al-Din Nayshapuri and other famous scholars came to study with him (Af 9; for the legend about Baha al-Din, see below, "The Mythical Baha al-Din"). Another report indicates that Baha al-Din's grandfather, Ahmad al-Khatibi, was born to Ferdows Khatun, a daughter of the reputed Hanafite jurist and author Shams al-A’emma Abu Bakr of Sarakhs, who died circa 1088 (Af 75; FB 6 n.4; Mei 74 n. 17). This is far from implausible and, if true, would tend to suggest that Ahmad al-Khatabi had studied under Shams al-A’emma. Prior to that the family could supposedly trace its roots back to Isfahan. We do not learn the name of Baha al-Din's mother in the sources, only that he referred to her as "Mama" (Mami), and that she lived to the 1200s." (p. 44)</ref> and that she was a simple woman who lived to the 1200s. The mother of Rumi was Mu'mina Khātūn. The profession of the family for several generations was that of Islamic preachers of the relatively liberal ] ] school, and this family tradition was continued by Rumi (see his Fihi Ma Fih and Seven Sermons) and Sultan Walad (see Ma'rif Waladi for examples of his everyday sermons and lectures). | ||

| When the ]s invaded |

When the ] sometime between 1215 and 1220, Baha ud-Din Walad, with his whole family and a group of disciples, set out westwards. According to hagiographical account which is not agreed upon by all Rumi scholars, Rumi encountered one of the most famous mystic Persian poets, ], in the Iranian city of ], located in the province of Khorāsān. Attar immediately recognized Rumi's spiritual eminence. He saw the father walking ahead of the son and said, "Here comes a sea followed by an ocean."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Suspended Somewhere Between: A Book of Verse|last=Ahmed|first=Akbar|publisher=PM Press|year=2011|isbn=978-1-60486-485-4|pages=i}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi|last=El-Fers|first=Mohamed|publisher=MokumTV|year=2009|isbn=978-1-4092-9291-3|pages=45}}</ref> Attar gave the boy his ''Asrārnāma'', a book about the entanglement of the soul in the material world. This meeting had a deep impact on the eighteen-year-old Rumi and later on became the inspiration for his works. | ||

| From Nishapur, Walad and his entourage set out for Baghdad, meeting many of the scholars and Sufis of the city. |

From Nishapur, Walad and his entourage set out for ], meeting many of the scholars and Sufis of the city.{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} From Baghdad they went to ] and performed the ] at ]. The migrating caravan then passed through ], ], ], ], ] and ]. They finally settled in ] for seven years; Rumi's mother and brother both died there. In 1225, Rumi married Gowhar Khatun in Karaman. They had two sons: Sultan Walad and Ala-eddin Chalabi. When his wife died, Rumi married again and had a son, Amir Alim Chalabi, and a daughter, Malakeh Khatun. | ||

| On 1 May 1228, most likely as a result of the insistent invitation of ], ruler of Anatolia, Baha' ud-Din came and finally settled in Konya in ] within the westernmost territories of the ]. | On 1 May 1228, most likely as a result of the insistent invitation of ], ruler of Anatolia, Baha' ud-Din came and finally settled in Konya in ] within the westernmost territories of the ]. | ||

| ===Education and encounters with Shams-e Tabrizi=== | |||

| Baha' ud-Din became the head of a ] (religious school) and when he died, Rumi, aged twenty-five, inherited his position as the Islamic molvi. One of Baha' ud-Din's students, Sayyed Burhan ud-Din Muhaqqiq Termazi, continued to train Rumi in the ] as well as the ], especially that of Rumi's father. For nine years, Rumi practiced Sufism as a disciple of Burhan ud-Din until the latter died in 1240 or 1241. Rumi's public life then began: he became an Islamic Jurist, issuing ] and giving sermons in the mosques of Konya. He also served as a Molvi (Islamic teacher) and taught his adherents in the madrassa. | |||

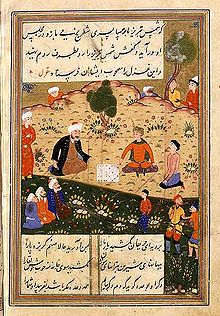

| ]''. See ].]] | |||

| Baha' ud-Din became the head of a ] (religious school) and when he died, Rumi, aged twenty-five, inherited his position as the Islamic molvi. One of Baha' ud-Din's students, Sayyed Burhan ud-Din Muhaqqiq Termazi, continued to train Rumi in the ] as well as the ], especially that of Rumi's father. For nine years, Rumi practised Sufism as a disciple of Burhan ud-Din until the latter died in 1240 or 1241. Rumi's public life then began: he became an Islamic Jurist, issuing ] and giving sermons in the mosques of Konya. He also served as a Molvi (Islamic teacher) and taught his adherents in the madrassa. | |||

| During this period, Rumi also |

During this period, Rumi also travelled to ] and is said to have spent four years there. | ||

| It was his meeting with the dervish ] on 15 November 1244 that completely changed his life. From an accomplished teacher and jurist, Rumi was transformed into an ascetic. | It was his meeting with the dervish ] on 15 November 1244 that completely changed his life. From an accomplished teacher and jurist, Rumi was transformed into an ascetic. | ||

| Shams had |

Shams had travelled throughout the Middle East searching and praying for someone who could "endure my company". A voice said to him: "What will you give in return?" Shams replied, "My head!" The voice then said, "The one you seek is Jalal ud-Din of Konya." On the night of 5 December 1248, as Rumi and Shams were talking, Shams was called to the back door. He went out, never to be seen again. It is rumoured that Shams was murdered with the connivance of Rumi's son, 'Ala' ud-Din; if so, Shams indeed gave his head for the privilege of mystical friendship.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.semazen.net/eng/show_text_main.php?id=166&menuId=17|title=Hz. Mawlana and Shams|website=semazen.net}}</ref> | ||

| Rumi's love for, and his bereavement at the death of, Shams found their expression in an outpouring lyric poems, ]. He himself went out searching for Shams and journeyed again to Damascus. There, he |

Rumi's love for, and his bereavement at the death of, Shams found their expression in an outpouring of lyric poems, ]. He himself went out searching for Shams and journeyed again to Damascus. There, he realised: | ||

| {{ |

{{blockquote| | ||

| Why should I seek? I am the same as<br /> | Why should I seek? I am the same as<br /> | ||

| He. His essence speaks through me.<br /> | He. His essence speaks through me.<br /> | ||

| I have been looking for myself!<ref>''The Essential Rumi''. Translations by Coleman Barks, p. xx.</ref>}} | I have been looking for myself!<ref>''The Essential Rumi''. Translations by Coleman Barks, p. xx.</ref> | ||

| }} | |||

| ===Later life and death=== | |||

| Mewlana had been spontaneously composing '']s'' (Persian poems), and these had been collected in the ''Divan-i Kabir'' or Diwan Shams Tabrizi. Rumi found another companion in Salaḥ ud-Din-e Zarkub, a goldsmith. After Salah ud-Din's death, Rumi's scribe and favorite student, Hussam-e Chalabi, assumed the role of Rumi's companion. One day, the two of them were wandering through the Meram vineyards outside Konya when Hussam described to Rumi an idea he had had: "If you were to write a book like the ''Ilāhīnāma'' of Sanai or the ''Mantiq ut-Tayr'' of 'Attar, it would become the companion of many troubadours. They would fill their hearts from your work and compose music to accompany it." Rumi smiled and took out a piece of paper on which were written the opening eighteen lines of his ''Masnavi'', beginning with: | |||

| ]), 1461 manuscript]] | |||

| Mewlana had been spontaneously composing '']s'' (Persian poems), and these had been collected in the ''Divan-i Kabir'' or Diwan Shams Tabrizi. Rumi found another companion in Salaḥ ud-Din-e Zarkub, a goldsmith. After Salah ud-Din's death, Rumi's scribe and favourite student, ], assumed the role of Rumi's companion. One day, the two of them were wandering through the Meram vineyards outside Konya when Hussam described to Rumi an idea he had had: "If you were to write a book like the ''Ilāhīnāma'' of Sanai or the ''Mantiq ut-Tayr'' of 'Attar, it would become the companion of many troubadours. They would fill their hearts from your work and compose music to accompany it." Rumi smiled and took out a piece of paper on which were written the opening eighteen lines of his ''Masnavi'', beginning with: | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| {{blockquote| | |||

| Listen to the reed and the tale it tells,<br /> | Listen to the reed and the tale it tells,<br /> | ||

| How it sings of separation...<ref>{{cite |

How it sings of separation...<ref>{{cite book |title=Rumi: Daylight: A Daybook of Spiritual Guidance |date=1999 |publisher=Shambhala Publications |isbn=978-0-8348-2517-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cRhfAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT11}}</ref> | ||

| }} | |||

| Hussam implored Rumi to write more. Rumi spent the next twelve years of his life in Anatolia dictating the six volumes of this masterwork, the ''Masnavi'', to Hussam. | Hussam implored Rumi to write more. Rumi spent the next twelve years of his life in Anatolia dictating the six volumes of this masterwork, the ''Masnavi'', to Hussam. | ||

| Line 98: | Line 115: | ||

| In December 1273, Rumi fell ill; he predicted his own death and composed the well-known ''ghazal'', which begins with the verse: | In December 1273, Rumi fell ill; he predicted his own death and composed the well-known ''ghazal'', which begins with the verse: | ||

| {{ |

{{blockquote| | ||

| How doest thou know what sort of king I have within me as companion?<br /> | How doest thou know what sort of king I have within me as companion?<br /> | ||

| Do not cast thy glance upon my golden face, for I have iron legs.<ref>{{cite book | |

Do not cast thy glance upon my golden face, for I have iron legs.<ref>{{cite book |last= Nasr |first=Seyyed Hossein |title= Islamic Art and Spirituality |publisher= SUNY Press |year= 1987 |page= 120 |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=EBu6gWcT0DsC&pg=PA120 |isbn= 978-0-88706-174-5}}</ref> | ||

| }} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Rumi died on 17 December 1273 in ] |

Rumi died on 17 December 1273 in ]. His death was mourned by the diverse community of Konya, with local Christians and Jews joining the crowd that converged to bid farewell as his body was carried through the city.<ref name=Mojaddedi-19>{{cite book|first=Jawid |last=Mojaddedi|chapter=Introduction|title=Rumi, Jalal al-Din. The Masnavi, Book One|publisher=Oxford University Press (Kindle Edition)|year=2004|page=xix}}</ref> Rumi's body was interred beside that of his father, and a splendid shrine, the "Green Tomb" (]: Yeşil Türbe, {{langx|ar|قبة الخضراء}}; today the ]), was erected over his place of burial. His epitaph reads: | ||

| {{ |

{{blockquote| | ||

| When we are dead, seek not our tomb in the earth, | When we are dead, seek not our tomb in the earth, | ||

| but find it in the hearts of men.<ref> |

but find it in the hearts of men.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://anatolia.com/anatolia/Religion_and_Spirituality/Mevlana/Default.asp|title= | ||

| Mevlana Jalal al-din Rumi|website= Anatolia.com|date=2 February 2002|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020202002121/http://anatolia.com/anatolia/Religion_and_Spirituality/Mevlana/Default.asp|archive-date=2 February 2002}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| Georgian princess and Seljuq queen ] was a close friend of Rumi. She was the one who sponsored the construction of ] in ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Crane |first1=H. |title=Notes on Saldjūq Architectural Patronage in Thirteenth Century Anatolia |journal=Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient |date=1993 |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=1–57 |id={{ProQuest|1304344524}} |doi=10.1163/156852093X00010 |jstor=3632470}}</ref> The 13th-century ], with its mosque, dance hall, schools and living quarters for dervishes, remains a destination of pilgrimage to this day, and is probably the most popular pilgrimage site to be regularly visited by adherents of every major religion.<ref name=Mojaddedi-19/> | |||

| The 13th century Mawlana Mausoleum, with its mosque, dance hall, dervish living quarters, school and tombs of some leaders of the Mevlevi Order, continues to this day to draw pilgrims from all parts of the Muslim and non-Muslim world. Jalal al-Din who is also known as Rumi, was a philosopher and mystic of Islam. His doctrine advocates unlimited tolerance, positive reasoning, goodness, charity and awareness through love. To him and to his disciples all religions are more or less truth. Looking with the same eye on Muslim, Jew and Christian alike, his peaceful and tolerant teaching has appealed to people of all sects and creeds. | |||

| ==Teachings== | ==Teachings== | ||

| ] |

], ], Turkey]] | ||

| Like other mystic and Sufi poets of Persian literature, Rumi's poetry speaks of love which infuses the world.{{Citation needed|date=May 2024}} Rumi's teachings also express the tenets summarized in the Quranic verse which Shams-e Tabrizi cited as the essence of prophetic guidance: "Know that ‘There is no god but He,’ and ask forgiveness for your sin" (Q. 47:19). | |||

| The general theme of Rumi's thought, like that of other mystic and Sufi poets of Persian literature, is essentially that of the concept of '']'' – union with his beloved (the primal root) from which/whom he has been cut off and become aloof – and his longing and desire to restore it | |||

| In the interpretation attributed to Shams, the first part of the verse commands the humanity to seek knowledge of '']'' (oneness of God), while the second instructs them to negate their own existence. In Rumi's terms, ''tawhid'' is lived most fully through love, with the connection being made explicit in his verse that describes love as "that flame which, when it blazes up, burns away everything except the Everlasting Beloved."<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|first=William C. |last=Chittick|title=RUMI, JALĀL-AL-DIN vii. Philosophy|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/rumi-philosophy|year=2017|encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Iranica}} | |||

| The ''Masnavi'' weaves fables, scenes from everyday life, Qur'anic revelations and exegesis, and metaphysics into a vast and intricate tapestry.<ref name="Rumi2011">{{cite book|author=Maulana Rumi|title=The Masnavi I Ma'navi of Rumi: Complete 6 Books|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=QwKJZwEACAAJ|accessdate=28 September 2011|date=25 May 2011|publisher=CreateSpace|isbn=978-1-4635-1016-9}}</ref> In the East, it is said of him that he was "not a prophet — but surely, he has brought a scripture".{{Cite quote|date= April 2012}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Rumi's longing and desire to attain this ideal is evident in the following poem from his book the ]:<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.dar-al-masnavi.org/n-III-3901.html|title=The Mathnawî-yé Ma'nawî – Rhymed Couplets of Deep Spiritual Meaning of Jalaluddin Rumi. |author=Ibrahim Gamard (with gratitude for R. A. Nicholson's 1930 British translation)}}</ref> | |||

| Rumi believed passionately in the use of music, poetry and dance as a path for reaching God. For Rumi, music helped devotees to focus their whole being on the divine and to do this so intensely that the soul was both destroyed and resurrected. It was from these ideas that the practice of ] developed into a ritual form. His teachings became the base for the order of the Mevlevi which his son Sultan Walad organized. Rumi encouraged ], listening to music and turning or doing the sacred dance. In the Mevlevi tradition, ''samāʿ'' represents a mystical journey of spiritual ascent through mind and love to the Perfect One. In this journey, the seeker symbolically turns towards the truth, grows through love, abandons the ego, finds the truth and arrives at the Perfect. The seeker then returns from this spiritual journey, with greater maturity, to love and to be of service to the whole of creation without discrimination with regard to beliefs, races, classes and nations. | |||

| {{Verse translation|italicsoff=y|rtl1=y| | |||

| {{lang|fa|rtl=yes| | |||

| از جمادی مُردم و نامی شدم | |||

| وز نما مُردم به حیوان برزدم | |||

| مُردم از حیوانی و آدم شدم | |||

| پس چه ترسم کی ز مردن کم شدم؟ | |||

| حملهٔ دیگر بمیرم از بشر | |||

| تا برآرم از ملائک بال و پر | |||

| وز ملک هم بایدم جستن ز جو | |||

| کل شیء هالک الا وجهه | |||

| بار دیگر از ملک پران شوم | |||

| آنچ اندر وهم ناید آن شوم | |||

| پس عدم گردم عدم چون ارغنون | |||

| گویدم که انا الیه راجعون}} | |||

| | | |||

| I died to the mineral state and became a plant, | |||

| I died to the vegetal state and reached animality, | |||

| I died to the animal state and became a man, | |||

| Then what should I fear? I have never become less from dying. | |||

| At the next charge (forward) I will die to human nature, | |||

| So that I may lift up (my) head and wings (and soar) among the angels, | |||

| And I must (also) jump from the river of (the state of) the angel, | |||

| Everything perishes except His Face, | |||

| Once again I will become sacrificed from (the state of) the angel, | |||

| I will become that which cannot come into the imagination, | |||

| Then I will become non-existent; non-existence says to me (in tones) like an organ, | |||

| ].}} | |||

| The ''Masnavi'' weaves fables, scenes from everyday life, Qur'anic revelations and exegesis, and metaphysics into a vast and intricate tapestry. | |||

| Rumi believed passionately in the use of music, poetry and dance as a path for reaching God. For Rumi, music helped devotees to focus their whole being on the divine and to do this so intensely that the soul was both destroyed and resurrected. It was from these ideas that the practice of ] developed into a ritual form. His teachings became the base for the order of the Mevlevi, which his son Sultan Walad organised. Rumi encouraged ], listening to music and turning or doing the sacred dance. In the Mevlevi tradition, ''samāʿ'' represents a mystical journey of spiritual ascent through mind and love to the Perfect One. In this journey, the seeker symbolically turns towards the truth, grows through love, abandons the ego, finds the truth and arrives at the Perfect. The seeker then returns from this spiritual journey, with greater maturity, to love and to be of service to the whole of creation without discrimination with regard to beliefs, races, classes and nations.{{citation needed|date=September 2016}} | |||

| In other verses in the ''Masnavi'', Rumi describes in detail the universal message of love: | In other verses in the ''Masnavi'', Rumi describes in detail the universal message of love: | ||

| {{ |

{{blockquote| | ||

| The |

The lover's cause is separate from all other causes<br /> | ||

| Love is the astrolabe of God's mysteries.<ref>{{cite book | last =Naini | first =Majid| title =The Mysteries of the Universe and Rumi's Discoveries on the Majestic Path of Love | |

Love is the astrolabe of God's mysteries.<ref>{{cite book | last =Naini | first =Majid| title =The Mysteries of the Universe and Rumi's Discoveries on the Majestic Path of Love | author-link=Majid Naini}}</ref> | ||

| }} | |||

| Rumi's favourite musical instrument was the ] (reed flute).<ref name="BBC-Haviland" /> | |||

| ==Major works== | ==Major works== | ||

| Line 130: | Line 185: | ||

| ===Poetic works=== | ===Poetic works=== | ||

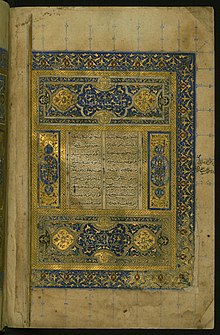

| ]]] | |||

| ], ], ] </center>]] | |||

| * Rumi's major work is the ''Maṭnawīye Ma'nawī'' (''Spiritual Couplets''; {{lang|fa|مثنوی معنوی}}), a six-volume poem regarded by some Sufis<ref> | |||

| Abdul Rahman ] notes: | |||

| * Rumi's best-known work is the '']'' (''Spiritual Couplets''; {{lang|fa|مثنوی معنوی}}). The six-volume poem holds a distinguished place within the rich tradition of Persian Sufi literature, and has been commonly called "the Quran in Persian".<ref>{{cite book|first=Jawid |last=Mojaddedi|chapter=Introduction|title=Rumi, Jalal al-Din. The Masnavi, Book One|publisher=Oxford University Press (Kindle Edition)|year=2004|page=xix|quote=Rumi’s Masnavi holds an exalted status in the rich canon of Persian Sufi literature as the greatest mystical poem ever written. It is even referred to commonly as ‘the Koran in Persian’.}}</ref><ref>Abdul Rahman ] notes: | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| من چه گویم وصف آن عالیجناب — نیست پیغمبر ولی دارد کتاب | |||

| {{blockquote|{{lang|fa|من چه گویم وصف آن عالیجناب — نیست پیغمبر ولی دارد کتاب}} | |||

| مثنوی معنوی مولوی — هست قرآن در زبان پهلوی}} | |||

| {{lang|fa|مثنویّ معنویّ مولوی — هست قرآن در زبان پهلوی}} | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| }} | |||

| {{blockquote| | |||

| What can I say in praise of that great one?<br /> | What can I say in praise of that great one?<br /> | ||

| He is not a Prophet but has come with a book;<br /> | He is not a Prophet but has come with a book;<br /> | ||

| The Spiritual ''Masnavi'' of Mowlavi<br /> | The Spiritual ''Masnavi'' of Mowlavi<br /> | ||

| Is the Qur'an in the language of Pahlavi (Persian).}} | Is the Qur'an in the language of Pahlavi (Persian). | ||

| }} | |||

| (Khawaja Abdul Hamid Irfani, "The Sayings of Rumi and Iqbal", Bazm-e-Rumi, 1976.)</ref> Many commentators have regarded it as the greatest mystical poem in world literature.<ref>{{cite book|first=Jawid |last=Mojaddedi|chapter=Introduction|title=Rumi, Jalal al-Din. The Masnavi, Book One|publisher=Oxford University Press (Kindle Edition)|year=2004|pages=xii–xiii|quote=Towards the end of his life he presented the fruit of his experience of Sufism in the form of the Masnavi, which has been judged by many commentators, both within the Sufi tradition and outside it, to be the greatest mystical poem ever written.}}</ref> It contains approximately 27,000 lines,<ref>Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West'', Oneworld Publications, 2008 (revised edition). p. 306: "The manuscripts versions differ greatly in the size of the text and orthography. Nicholson’s text has 25,577 lines though the average medieval and early modern manuscripts contained around 27,000 lines, meaning the scribes added two thousand lines or about eight percent more to the poem composed by Rumi. Some manuscripts give as many as 32,000!"</ref> each consisting of a couplet with an internal rhyme.<ref name="Mojaddedi-19"/> While the mathnawi genre of poetry may use a variety of different metres, after Rumi composed his poem, the metre he used became the mathnawi metre ''par excellence''. The first recorded use of this metre for a mathnawi poem took place at the Nizari Ismaili fortress of Girdkuh between 1131 and 1139. It likely set the stage for later poetry in this style by mystics such as Attar and Rumi.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Virani |first1=Shafique N. |title=Persian Poetry, Sufism and Ismailism: The Testimony of Khwājah Qāsim Tushtarī's Recognizing God |journal=Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society |date=January 2019 |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=17–49 |id={{ProQuest|2300038453}} |doi=10.1017/S1356186318000494 |s2cid=165288246}}</ref> | |||

| (Khawaja Abdul Hamid Irfani, "The Sayings of Rumi and Iqbal", Bazm-e-Rumi, 1976.) | |||

| </ref> as the Persian-language ]. It is considered by many to be one of the greatest works of mystical poetry.<ref>J.T.P. de Bruijn, "Comparative Notes on Sanai and 'Attar" , The Heritage of Sufism, L. Lewisohn, ed., pp. 361: "It is common place to mention Hakim Sana'i (d. 525/1131) and Farid al-Din 'Attar (1221) together as early highlights in a tradition of Persian mystical poetry which reached its culmination in the work of Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi and those who belonged to the early Mawlawi circle. There is abundant evidence available to prove that the founders of the Mawlawwiya in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries regarded these two poets as their most important predecessors"</ref> It contains approximately 27000 lines of Persian poetry.<ref>Franklin Lewis, Rumi Past and Present, East and West, Oneworld Publications, 2008 (revised edition). pg 306: "The manuscripts versions differ greatly in the size of the text and orthography. Nicholson’s text has 25,577 lines though the average medieval and early modern manuscripts contained around 27,000 lines, meaning the scribes added two thousand lines or about eight percent more to the poem composed by Rumi. Some manuscripts give as many as 32000!"</ref> | |||

| * Rumi's other major work is the ''Dīwān-e Kabīr'' (''Great Work'') or '']'' (''The Works of Shams of ]''; {{lang|fa|دیوان شمس تبریزی}}), named in honour of Rumi's master ]. Besides approximately 35000 Persian couplets and 2000 Persian quatrains,<ref>Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teaching, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi'' (2008), p. 314: "The Foruzanfar's edition of the Divan-e Shams compromises 3229 ghazals and qasidas making a total of almost 35000 lines, not including several hundred lines of stanzaic poems and nearly two thousand quatrains attributed to him”</ref> the Divan contains 90 Ghazals and 19 quatrains in Arabic,<ref>: According to the Dar al-Masnavi website: “In Forûzânfar's edition of Rumi's Divan, there are 90 ghazals (Vol. 1, 29; Vol. 2, 1; Vol. 3, 6; Vol. 4, 8; Vol. 5, 19, Vol. 6, 0; Vol. 7, 27) and 19 quatrains entirely in Arabic. In addition, there are ghazals which are all Arabic except for the final line; many have one or two lines in Arabic within the body of the poem; some have as many as 9–13 consecutive lines in Arabic, with Persian verses preceding and following; some have alternating lines in Persian, then Arabic; some have the first half of the verse in Persian, the second half in Arabic.”</ref> a couple of dozen or so couplets in Turkish (mainly ] poems of mixed Persian and Turkish)<ref>Mecdut MensurOghlu: “The Divan of Jalal al-Din Rumi contains 35 couplets in Turkish and Turkish-Persian which have recently been published me” (Celal al-Din Rumi’s turkische Verse: UJb. XXIV (1952), pp. 106–115)</ref><ref>Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teaching, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi'' (2008): "a couple of dozen at most of the 35,000 lines of the Divan-I Shams are in Turkish, and almost all of these lines occur in poems that are predominantly in Persian".</ref> and 14 couplets in Greek (all of them in three macaronic poems of Greek-Persian).<ref name=Dedes1993/><ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.opoudjis.net/Play/rumiwalad.html |first=Nick|last=Nicholas|website=Opoudjis|title=Greek Verses of Rumi & Sultan Walad|date=22 April 2009}}</ref><ref>Lewis, ''Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teaching, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi'' (2008): "Three poems have bits of demotic Greek; these have been identified and translated into French, along with some Greek verses of Sultan Valad. ] (GM 416–417) indicates according to Vladimir Mir Mirughli, the Greek used in some of Rumi's macaronic poems reflects the demotic Greek of the inhabitants of Anatolia. Golpinarli then argues that Rumi knew classical Persian and Arabic with precision, but typically composes poems in a more popular or colloquial Persian and Arabic."</ref> | |||

| {{Further2|]}} | |||

| * Rumi's other major work is the ''Dīwān-e Kabīr'' (''Great Work'') or ''Diwan-e Shams-e Tabrizi|Dīwān-e Shams-e Tabrīzī'' (''The Works of Shams of ]''; {{lang|fa|دیوان شمس تبریزی}} named in honor of Rumi's master ]. Besides approximately 35000 Persian couplets and 2000 Persian quatrains,<ref>Franklin D. Lewis, Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teaching, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi, rev. ed. (2008). pg 314: “The Foruzanfar’s edition of the Divan-e Shams compromises 3229 ghazals and qasidas making a total of almost 35000 lines, not including several hundred lines of stanzaic poems and nearly two thousand quatrains attributed to him”</ref> the Divan contains 90 Ghazals and 19 quatrains in ],<ref>: According to the Dar al-Masnavi website: “In Forûzânfar's edition of Rumi's Divan, there are 90 ghazals (Vol. 1, 29;Vol. 2, 1; Vol. 3, 6; Vol. 4, 8; Vol. 5, 19, Vol. 6, 0; Vol. 7, 27) and 19 quatrains entirely in Arabic. In addition, there are ghazals which are all Arabic except for the final line; many have one or two lines in Arabic within the body of the poem; some have as many as 9-13 consecutive lines in Arabic, with Persian verses preceding and following; some have alternating lines in Persian, then Arabic; some have the first half of the verse in Persian, the second half in Arabic.”</ref> a couple of dozen or so couplets in Turkish (mainly macaronic poems of mixed Persian and Turkish)<ref>Mecdut MensurOghlu: “The Divan of Jalal al-Din Rumi contains 35 couplets in Turkish and Turkish-Persian which have recently been published me” (Celal al-Din Rumi’s turkische Verse: UJb. XXIV (1952), pp 106-115)</ref><ref>Franklin D. Lewis, Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teaching, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi, rev. ed. (2008):"“a couple of dozen at most of the 35,000 lines of the Divan-I Shams are in Turkish, and almost all of these lines occur in poems that are predominantly in Persian”"</ref> and 14 couplets in Greek (all of them in three macaronic poems of Greek-Persian).<ref>Dedes, D. 1993. Ποίηματα του Μαυλανά Ρουμή . Ta Istorika 10.18-19: 3-22. see also </ref><ref>Franklin D. Lewis, Rumi: Past and Present, East and West: The Life, Teaching, and Poetry of Jalâl al-Din Rumi, rev. ed. (2008):"Three poems have bits of demotic Greek; these have been identified and translated into French, along with some Greek verses of Sultan Valad. Golpinarli (GM 416-417) indicates according to Vladimir Mir Mirughli, the Greek used in some of Rumi’s macaronic poems reflects the demotic Greek of the inhabitants of Anatolia. Golpinarli then argues that Rumi knew classical Persian and Arabic with precision, but typically composes poems in a more popular or colloquial Persian and Arabic.".</ref> | |||

| {{Further2|]}} | |||

| ===Prose works=== | ===Prose works=== | ||