| Revision as of 05:00, 13 May 2006 view sourceJossi (talk | contribs)72,880 editsm Reverted edits by 216.164.203.90 (talk) to last version by KimvdLinde← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:10, 31 December 2024 view source Wolverine X-eye (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers15,352 edits →North America: CvtTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Species of canine}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | color = pink | |||

| {{Redirect2|Grey Wolf|Gray Wolf|other uses|Grey Wolf (disambiguation)|and|Wolf (disambiguation)}} | |||

| | name = Gray Wolf | |||

| {{Redirect|Wolves|football club|Wolverhampton Wanderers F.C.}} | |||

| | status = {{StatusConcern}} | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| | image = Canis lupus laying in grass.jpg | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| | image_width = 230px | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| | regnum = ]ia | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=December 2019}} | |||

| | phylum = ] | |||

| {{Use Canadian English|date=December 2019}} | |||

| | classis = ]ia | |||

| {{Speciesbox | |||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| | |

| name = Wolf | ||

| | fossil_range = {{longitem|style=line-height:1.25em|{{nowrap|] – present}} {{nowrap|(400,000–0 ])}}}} | |||

| | genus = '']'' | |||

| | image = Eurasian wolf 2.jpg | |||

| | species = '''''C. lupus''''' | |||

| | image_caption = {{longitem|] (''Canis lupus lupus'') at ] in Bardu, Norway}} | |||

| | binomial = ''Canis lupus'' | |||

| | status = LC | |||

| | binomial_authority = ], 1758 | |||

| | status_system = IUCN3.1 | |||

| | status_ref = <ref name="iucn status 2 June 2024">{{cite iucn |author=Boitani, L. |author2=Phillips, M. |author3=Jhala, Y. |name-list-style=amp |year=2023 |title=''Canis lupus'' |amends=2018 |page=e.T3746A247624660 |doi=10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T3746A247624660.en |access-date=2 June 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | status2 = CITES_A2 | |||

| | status2_system = CITES | |||

| | status2_ref = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Appendices {{!}} CITES|url=https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php|access-date=2022-01-14|website=cites.org}}</ref>{{efn|Populations of Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Pakistan are included in Appendix I. Excludes domesticated form and dingo, which are referenced as ''Canus lupus familiaris'' and ''Canus lupus dingo''.}} | |||

| | taxon = Canis lupus | |||

| | authority = ], ]<ref name=Linnaeus1758/> | |||

| | subdivision_ranks = Subspecies | |||

| | subdivision = {{small|See ]}} | |||

| | range_map = Canis lupus distribution (IUCN).png | |||

| | range_map_caption = Global wolf range based on IUCN's 2023 assessment.<ref name="iucn status 2 June 2024" /> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{redirect|Wolf}} | |||

| The '''wolf''' ('''''Canis lupus''''';{{efn|Domestic and feral ]s are included in the ] but not colloquial definition of 'wolf', and are thus not in the scope of this article.}} {{plural form}}: '''wolves'''),<!--This article uses "wolf" rather than "grey wolf" or "gray wolf" throughout; see the discussion at https://en.wikipedia.org/Talk:Wolf/Archive_6#Requested_move_2_August_2018--> also known as the '''grey wolf''' or '''gray wolf''', is a ] native to ] and ]. More than thirty ] have been recognized, including the ] and ], though grey wolves, as popularly understood, only comprise ] subspecies. The wolf is the largest wild ] member of the family ], and is further distinguished from other '']'' species by its less pointed ears and muzzle, as well as a shorter torso and a longer tail. The wolf is nonetheless related closely enough to smaller ''Canis'' species, such as the ] and the ], to produce fertile ] with them. The wolf's fur is usually mottled white, brown, grey, and black, although subspecies in the arctic region may be nearly all white. | |||

| The '''Gray Wolf''' (''Canis lupus''; also spelled '''Grey Wolf''', see ]; other forms: '''Timber Wolf''', '''Wolf'''). The Gray Wolf shares a common ancestry with the ] (''Canis lupus familiaris''), and is known from DNA sequencing and genetic drift studies to be the ] of all dogs as they exist today.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Lindblad-Toh, K, et al. | title = Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. | journal = ] | volume = 438 | pages = 803-819 | year = 2005}}</ref> Gray wolves were once abundant and distributed over much of ], ], and the ]. Today, for a variety of human-related reasons including widespread habitat destruction and excessive ], wolves inhabit only a very limited portion of their former range. | |||

| Of all members of the ] ''Canis'', the wolf is most ] for ] ] as demonstrated by its physical adaptations to tackling large prey, its more ], and its highly advanced ], including individual or group ]. It travels in ] consisting of a ] accompanied by their offspring. Offspring may leave to form their own ]s on the onset of sexual maturity and in response to competition for food within the pack. Wolves are also ], and fights over territory are among the principal causes of mortality. The wolf is mainly a ] and feeds on large wild ]s as well as smaller animals, livestock, ], and garbage. Single wolves or mated pairs typically have higher success rates in hunting than do large packs. ]s and parasites, notably the ], may infect wolves. | |||

| Gray wolves, being ], are integral components of the ]s to which they typically belong. The wide range of ] in which wolves can thrive reflects their adaptability as a ], and includes ]s, ]s, ], ], and ]. In the ], with the exception of ] and ] (where they have a ] status), they are listed as ] under the ]. They continue to be hunted in many areas of the world as perceived threats to livestock and human well-being, as well as for sport. | |||

| The global wild wolf population was estimated to be 300,000 in 2003 and is considered to be of ] by the ] (IUCN). Wolves have a long history of interactions with humans, having been despised and hunted in most ] communities because of their attacks on livestock, while conversely being respected in some ] and ] societies. Although the fear of wolves exists in many human societies, the majority of recorded attacks on people have been attributed to animals suffering from ]. ]s on humans are rare because wolves are relatively few, live away from people, and have developed a fear of humans because of their experiences with hunters, farmers, ranchers, and shepherds. | |||

| ] gave the wolf the scientific name ''Canis lupus'' in the 18th century.<ref><span class="plainlinks">. ''What is a wolf?'' URL accessed on ], ].</span></ref> | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| == Anatomy, physiology, and reproduction == | |||

| {{See also|Wolf (name)}} | |||

| === Features and adaptations === | |||

| Wolf weight and size can vary greatly worldwide, though both tend to increase proportionally with higher ]s. Generally speaking, height varies from 0.6 to 0.9 meters (24 to 35 inches) at the shoulder, and weight can range anywhere from 25 to 65 kg (55-143 pounds), making wolves the largest among all wild canids. Although rarely encountered, extreme specimens reaching 80 kg (176 lb.) have been recorded in Alaska and Canada, though some people claim to have seen even larger anomalous individuals (90+ kg) roaming the ], where some of the largest wolves in North America can be found. Customarily, however, wolves will be of a more typical physical capacity, with the females in a given population weighing about twenty percent less than their male counterparts. Wolves can measure anywhere between 1.3 and 2 meters (51 to 78 inches) from nose to ] tip, with the tail itself consisting of approximately one quarter of overall body length. | |||

| The English "wolf" stems from the ] {{wikt-lang|ang|wulf}}, which is itself thought to be derived from the ] {{lang|gem-x-proto|*wulfaz}}. The ] *''{{PIE|]}}'' may also be the source of the ] word for the animal ''lupus'' (*''{{PIE|lúkʷos}}'').<ref>{{OEtymD|wolf}}</ref><ref name=Lehrman/> The name "grey wolf" refers to the greyish colour of the species.<ref name=Goldman/> | |||

| Wolves are built for stamina, possessing features tailored for long-distance travel. Narrow chests and powerful backs and legs contribute to the wolf's proficiency for efficient locomotion. They are capable of covering several miles trotting at about a 10 km/h (6 mph) pace, though they have been known to reach speeds approaching 65 km/h (40 mph) during a chase (wolves only run fast when testing potential prey). While sprinting thus, wolves can cover up to 5 m (16 ft) per bound. | |||

| ] | |||

| Wolf ]s are designed to traverse easily through a wide variety of terrains, especially snow. There is a slight webbing between each toe, which allows wolves to move over snow more easily than comparatively hampered prey. Wolves are ], so the relative largeness of their feet helps to better distribute their weight on snowy surfaces. The front paws are larger than the hind paws, and feature a fifth digit, a ], that is absent on hind paws. Bristled hairs and blunt claws enhance grip on slippery surfaces, and special blood vessels keep paw pads from freezing. Furthermore, ]s located between a wolf's toes leave trace chemical markers behind, thereby helping the wolf to effectively navigate over large expanses while concurrently keeping others informed of its whereabouts. | |||

| Since pre-Christian times, ] such as the ]s took on ''wulf'' as a ] or ] in their names. Examples include Wulfhere ("Wolf Army"), Cynewulf ("Royal Wolf"), Cēnwulf ("Bold Wolf"), Wulfheard ("Wolf-hard"), Earnwulf ("Eagle Wolf"), Wulfstān ("Wolf Stone") Æðelwulf ("Noble Wolf"), Wolfhroc ("Wolf-Frock"), Wolfhetan ("Wolf Hide"), Scrutolf ("Garb Wolf"), Wolfgang ("Wolf Gait") and Wolfdregil ("Wolf Runner").{{sfn|Marvin|2012|pp=74–75}} | |||

| A wolf sometimes seems more massive than it actually is due to its bulky ], which is made of two layers. The first layer consists of tough ]s designed to repel water and dirt. The second is a dense, water-resistant ] that insulates. Wolves have distinct winter and summer ]s that alternate in spring and autumn. Females tend to keep their winter coats further into the spring than males. | |||

| == Taxonomy == | |||

| Coloration varies greatly, and runs from gray to gray-brown, all the way through the canine spectrum of white, red, brown, and black. These colors tend to mix in many populations to form predominantly blended individuals, though it is certainly not uncommon for an individual or an entire population to be entirely one color (usually all black or all white). A multicolor coat characteristically lacks any clear pattern other than it tends to be lighter on the animal's underside. ] color sometimes corresponds with a given wolf population's environment; for example, all-white wolves are much more common in areas with perennial snow cover.<ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Eyes on Wildlife | work= Natural History of the Gray Wolf | url=http://www.mnstate.edu/regsci/eyes/Natural%20History%20of%20the%20Gray%20Wolf.htm | accessdate=August 21 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> Aging wolves acquire a grayish tint in their coats. | |||

| {{cladogram|title=Canine phylogeny with ages of divergence | |||

| |caption=Cladogram and divergence of the grey wolf (including the domestic dog) among its closest extant relatives<ref name=Koepfli-2015/> | |||

| |cladogram={{clade| style=font-size:85%;line-height:75%;width:475px; | |||

| |sublabel1=''3.50 ]''<!--E--> | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |sublabel1=''3.06 mya''<!--F--> | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |sublabel1=''2.74 mya''<!--G--> | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |sublabel1=''1.92 mya''<!--H--> | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |sublabel1=''1.62 mya''<!--I--> | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |sublabel1=''1.32 mya''<!--J--> | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |sublabel1=''1.10 mya''<!--K--> | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |1='''Grey wolf''' ] | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |sublabel2=''2.62 mya''<!--D--> | |||

| |2={{clade | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| In 1758, the Swedish botanist and zoologist ] published in his '']'' the ].<ref name=Linnaeus1758/> '']'' is the Latin word meaning "]",<ref>{{OEtymD|canine}}</ref> and under this ] he listed the doglike carnivores including domestic dogs, wolves, and ]s. He classified the domestic dog as ''Canis familiaris'', and the wolf as ''Canis lupus''.<ref name=Linnaeus1758/> Linnaeus considered the dog to be a separate species from the wolf because of its "cauda recurvata" (upturning tail) which is not found in any other ].<ref name=Clutton-Brock1995/> | |||

| === Subspecies === | |||

| At birth, wolf pups tend to have darker fur and blue eyes that will change to a yellow-gold or orange color when the pups are 8-16 weeks old. Though extremely unusual, it is possible for an adult wolf to retain its blue-colored eyes. | |||

| {{Main|Subspecies of Canis lupus}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Further|Pleistocene wolf}} | |||

| Wolves have stout, blocky ]s that help distinguish them from ]s and ]s. Wolves also differ in certain skull dimensions, having a smaller orbital angle, for example, than dogs (>53 degrees for dogs compared to <45 degrees for wolves) while possessing a comparatively larger brain capacity. Larger paw size, yellow eyes, longer legs, and bigger teeth further distinguish adult wolves from other canids, particularly dogs. Also, precaudal glands at the base of the tail are present in wolves, whereas they are not in dogs. | |||

| In the third edition of '']'' published in 2005, the ] ] listed under ''C. lupus'' 36 wild subspecies, and proposed two additional subspecies: ''familiaris'' (Linnaeus, 1758) and '']'' (Meyer, 1793). Wozencraft included ''hallstromi''—the ]—as a ] for the ]. Wozencraft referred to a 1999 ] (mtDNA) study as one of the guides in forming his decision, and listed the 38 ] under the biological ] of "wolf", the ] being the ] (''C. l. lupus'') based on the ] that Linnaeus studied in Sweden.<ref name=Wozencraft2005/> Studies using ] techniques reveal that the modern wolf and the dog are ], as modern wolves are not closely related to the population of wolves that was first ].<ref name=Larson2014/> In 2019, a workshop hosted by the ]/Species Survival Commission's Canid Specialist Group considered the New Guinea singing dog and the dingo to be ] ''Canis familiaris'', and therefore should not be assessed for the ].<ref name=Alvares2019/> | |||

| === Evolution === | |||

| Wolves and most larger dogs share identical ]: The ] has six ]s, two ]s, eight ]s, and four ]. The ] has six incisors, two canines, eight premolars, and six molars.<ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= World of the Wolf | work= The skull of Canis lupus | url=http://www.naturalworlds.org/wolf/moretopics/wolf_skull.htm | accessdate=August 21 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> The fourth upper premolars and first lower molars constitute the ] teeth, which are essential tools for shearing flesh. The long canine teeth are also important, in that they are designed to hold and subdue the prey. Powered by 1500 lb/sq. inch of ], a wolf's teeth are its main weapons as well as its primary tools. Therefore, any injury to the jaw line or teeth could devastate an individual, dooming it to starvation or incompetence. | |||

| {{Main|Evolution of the wolf}} | |||

| {{Further|Domestication of the dog}} | |||

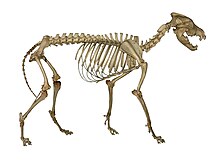

| ]'', the wolf's immediate ancestor]] | |||

| The ] descent of the extant wolf ''C. lupus'' from the earlier '']'' (which in turn descended from '']'') is widely accepted.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=239–245}} Among the oldest fossils of the modern grey wolf is from Ponte Galeria in Italy, dating to 406,500 ± 2,400 years ago.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last1=Iurino |first1=Dawid A. |last2=Mecozzi |first2=Beniamino |last3=Iannucci |first3=Alessio |last4=Moscarella |first4=Alfio |last5=Strani |first5=Flavia |last6=Bona |first6=Fabio |last7=Gaeta |first7=Mario |last8=Sardella |first8=Raffaele |date=2022-02-25 |title=A Middle Pleistocene wolf from central Italy provides insights on the first occurrence of Canis lupus in Europe |journal=Scientific Reports |language=en |volume=12 |issue=1 |page=2882 |doi=10.1038/s41598-022-06812-5 |issn=2045-2322 |pmc=8881584 |pmid=35217686|bibcode=2022NatSR..12.2882I }}</ref> Remains from Cripple Creek Sump in Alaska may be considerably older, around 1 million years old,<ref name=Tedford2009/> though differentiating between the remains of modern wolves and ''C. mosbachensis'' is difficult and ambiguous, with some authors choosing to include C. ''mosbachensis'' (which first appeared around 1.4 million years ago) as an early subspecies of ''C. lupus.''<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| Considerable morphological diversity existed among wolves by the ]. Many Late Pleistocene wolf populations had more robust skulls and teeth than modern wolves, often with a shortened ], a pronounced development of the ] muscle, and robust ]s. It is proposed that these features were specialized adaptations for the processing of carcass and bone associated with the hunting and scavenging of ]. Compared with modern wolves, some Pleistocene wolves showed an increase in tooth breakage similar to that seen in the extinct ]. This suggests they either often processed carcasses, or that they competed with other carnivores and needed to consume their prey quickly. The frequency and location of tooth fractures in these wolves indicates they were habitual bone crackers like the modern ].<ref name=Thalmann2018/> | |||

| === Courtship and mating === | |||

| ] studies suggest modern wolves and dogs descend from a common ancestral wolf population.<ref name=Freedman2014/><ref name=Skoglund2015/><ref name=Fan2016/> A 2021 study found that the ] and the ] are part of a ] that is ] to other wolves and ] from them 200,000 years ago.<ref name=Hennelly2021/> Other wolves appear to share most of their common ancestry much more recently, within the last 23,000 years (around the peak and the end of the ]), originating from ]<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last1=Bergström |first1=Anders |last2=Stanton |first2=David W. G. |last3=Taron |first3=Ulrike H. |last4=Frantz |first4=Laurent |last5=Sinding |first5=Mikkel-Holger S. |last6=Ersmark |first6=Erik |last7=Pfrengle |first7=Saskia |last8=Cassatt-Johnstone |first8=Molly |last9=Lebrasseur |first9=Ophélie |last10=Girdland-Flink |first10=Linus |last11=Fernandes |first11=Daniel M. |last12=Ollivier |first12=Morgane |last13=Speidel |first13=Leo |last14=Gopalakrishnan |first14=Shyam |last15=Westbury |first15=Michael V. |date=2022-07-14 |title=Grey wolf genomic history reveals a dual ancestry of dogs |journal=Nature |language=en |volume=607 |issue=7918 |pages=313–320 |doi=10.1038/s41586-022-04824-9 |issn=0028-0836 |pmc=9279150 |pmid=35768506|bibcode=2022Natur.607..313B }}</ref> or ].<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last1=Loog |first1=Liisa |last2=Thalmann |first2=Olaf |last3=Sinding |first3=Mikkel-Holger S. |last4=Schuenemann |first4=Verena J. |last5=Perri |first5=Angela |last6=Germonpré |first6=Mietje |last7=Bocherens |first7=Herve |last8=Witt |first8=Kelsey E. |last9=Samaniego Castruita |first9=Jose A. |last10=Velasco |first10=Marcela S. |last11=Lundstrøm |first11=Inge K. C. |last12=Wales |first12=Nathan |last13=Sonet |first13=Gontran |last14=Frantz |first14=Laurent |last15=Schroeder |first15=Hannes |date=May 2020 |title=Ancient DNA suggests modern wolves trace their origin to a Late Pleistocene expansion from Beringia |journal=Molecular Ecology |language=en |volume=29 |issue=9 |pages=1596–1610 |doi=10.1111/mec.15329 |issn=0962-1083 |pmc=7317801 |pmid=31840921|bibcode=2020MolEc..29.1596L }}</ref> While some sources have suggested that this was a consequence of a ],<ref name=":1" /> other studies have suggested that this a result of ] homogenising ancestry.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| Usually, the desire to pass on ] drives young wolves away from their birth packs, leading them to seek out mates and territories of their own. Dispersals occur at all times during the year, typically involving wolves who reached ] during the previous ]. It takes two such dispersals from two different packs for the process to take place (though it can occur, dispersing wolves from the same pack rarely mate). Once two dispersing wolves meet and begin traveling together, they immediately begin the process of seeking out territory, preferentially doing so in time for the next mating season. The bond that forms between such wolves lasts for the shorter of the two lifetimes, with few exceptions. | |||

| A 2016 genomic study suggests that Old World and New World wolves split around 12,500 years ago followed by the ] of the lineage that led to dogs from other Old World wolves around 11,100–12,300 years ago.<ref name=Fan2016/> An extinct ] may have been the ancestor of the dog,<ref name=Freedman2017/><ref name=Thalmann2018/> with the dog's similarity to the extant wolf being the result of ] between the two.<ref name=Thalmann2018/> The dingo, ], ] and Chinese indigenous breeds are basal members of the domestic dog clade. The divergence time for wolves in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia is estimated to be fairly recent at around 1,600 years ago. Among New World wolves, the ] diverged around 5,400 years ago.<ref name=Fan2016/> | |||

| During the mating season, breeding wolves become extremely affectionate with one another in anticipation for the female's ]. Overall, pack tension rises, as each mature wolf begins to feel the urge to mate. In fact, during this time, the alpha male and alpha female may be forced to aggressively prevent other wolves from mating with each other. Under normal circumstances, a pack can only support one ] per year, so this type of dominance behavior is beneficial in the long run. | |||

| === Admixture with other canids === | |||

| When the alpha female goes into ] – a phenomenon that occurs once per year, and lasts between five and fourteen days – she and her mate will spend an increased amount of time in seclusion. ] in the female's ] and the swelling of her ] let the male know when his mate is in heat. She will be unreceptive for the first few days of estrus, during which time she sheds the lining of her ]. Once the female begins to ovulate, mating occurs. | |||

| {{Main|Canid hybrid}} | |||

| The male wolf will mount the female firmly from behind. After achieving ], the two form a copulatory tie once the bulb ('']''; located near the base of the canine ]) of the male's penis swells and the female's vaginal muscles tighten. ] is induced by the thrusting of the male's ] and the undulation of the female's ]. The two become physically inseparable for anywhere between ten and thirty minutes, during which period the male will ejaculate multiple times. The male will occasionally lift one of his legs over the female such that they are standing end-to-end. This is believed to limit the leakage of ]; it may also be a defensive measure. | |||

| ] in the wild animal park at ], Poland. Left: product of a male wolf and a female ]; right: from a female wolf and a male ]]] | |||

| In the distant past, there was ] between ], ]s, and grey wolves. The African wolf is a descendant of a genetically admixed canid of 72% wolf and 28% Ethiopian wolf ancestry. One African wolf from the Egyptian ] showed admixture with Middle Eastern grey wolves and dogs.<ref name=Gopalakrishnan2018/> There is evidence of gene flow between golden jackals and Middle Eastern wolves, less so with European and Asian wolves, and least with North American wolves. This indicates the golden jackal ancestry found in North American wolves may have occurred before the divergence of the Eurasian and North American wolves.<ref name=Sinding2018/> | |||

| The mating ordeal is repeated many times throughout the female's brief ovulation period, which occurs once per year per female (unlike female dogs, with whom estrus usually occurs twice per year). It is believed that both males and females can continue to breed in this manner until at least ten years of age. | |||

| The common ancestor of the coyote and the wolf is admixed with a ] of an extinct unidentified canid. This canid was genetically close to the ] and evolved after the divergence of the ] from the other canid species. The basal position of the ] compared to the wolf has been proposed to be due to the coyote retaining more of the mitochondrial genome of this unidentified canid.<ref name=Gopalakrishnan2018/> Similarly, a museum specimen of a wolf from southern China collected in 1963 showed a genome that was 12–14% admixed from this unknown canid.<ref name=Wang2019/> In North America, some coyotes and wolves show varying degrees of past ].<ref name=Sinding2018/> | |||

| === Breeding and life cycle === | |||

| In more recent times, some male ] originated from dog ancestry, which indicates female wolves will breed with male dogs in the wild.<ref name=Iacolina2010/> In the ], ten percent of dogs including ]s, are first generation hybrids.<ref name=Kopaliani2014/> Although mating between golden jackals and wolves has never been observed, evidence of ]ization was discovered through mitochondrial DNA analysis of jackals living in the Caucasus Mountains<ref name=Kopaliani2014/> and in Bulgaria.<ref name=Moura2013/> In 2021, a genetic study found that the dog's similarity to the extant grey wolf was the result of substantial dog-into-wolf ], with little evidence of the reverse.<ref name="Bergström2020"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| Normally, only the alpha pair of the pack breeds, which is a kind of organization not uncommon to other pack-hunting canids including the ] and the ]. ] occurs between January and April, happening later in the year as latitude increases. A pack usually produces a single ], though sometimes multiple litters will be born if the alpha male mates with one or more subordinate females. Under normal circumstances, the alpha female will try to prevent this by aggressively dominating other females and physically separating them from the alpha male during the mating season. | |||

| == Description == | |||

| The ] lasts 60 to 63 days, and the pups are born ], ], and completely dependent on their mother (i.e. altricial). There are 1–14 pups per litter, with the average litter size being about four to six. Pups reside in the ], where they are born, and stay there until they reach about 8 ]s of age (the den is usually on high ground near an open water source, and has an open "room" at the end of an ]/] ] that can be up to a few meters long). During this time, the pups will become more independent, and will eventually begin to explore the area immediately outside the den before gradually roaming up to a mile away from it. They begin eating ]d foods at four weeks – by which time their milk teeth have emerged – and are weaned by six weeks. During the first weeks of development, the mother usually stays with her litter alone, but eventually most members of the pack will contribute to the ]ing of the pups in some way. <ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Animal Diversity Web | work= Canis lupus | url= http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Canis_lupus.html | accessdate=August 18 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| After two months, the restless pups will be moved to a rendezvous site, which gives them a safe place to reside while most of the adults go out to ]. An adult or two will stay behind to ensure the safety of the pups. After a few more weeks, the pups are permitted to join the adults if they are able (they tag along as observers until about eight months, by which time they are large enough to actively participate), and will receive first priority on anything killed, their low ranks notwithstanding. Letting the pups fight for the right to eat results in a secondary ranking being formed among them, and lets them practice the dominance/submission rituals that will be essential to their future survival in pack life. | |||

| The wolf is the largest extant member of the family ],<ref name=Mech1974/> and is further distinguished from coyotes and jackals by a broader snout, shorter ears, a shorter torso and a longer tail.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=129–132}}<ref name=Mech1974/> It is slender and powerfully built, with a large, deeply descending ], a sloping back, and a heavily muscled neck.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|p=166}} The wolf's legs are moderately longer than those of other canids, which enables the animal to move swiftly, and to overcome the deep snow that covers most of its geographical range in winter,{{sfn|Mech|1981|p=13}} though more short-legged ecomorphs are found in some wolf populations.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Tomiya |first1=Susumu |last2=Meachen |first2=Julie A. |date=17 January 2018 |title=Postcranial diversity and recent ecomorphic impoverishment of North American gray wolves |journal=] |language=en |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=20170613 |doi=10.1098/rsbl.2017.0613 |issn=1744-9561 |pmc=5803591 |pmid=29343558 }}</ref> The ears are relatively small and triangular.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|p=166}} The wolf's head is large and heavy, with a wide forehead, strong jaws and a long, blunt muzzle.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} The skull is {{cvt|230|–|280|mm}} in length and {{cvt|130|–|150|mm}} in width.{{sfn|Mech|1981|p=14}} The teeth are heavy and large, making them better suited to crushing bone than those of other canids, though they are not as specialized as those found in ]s.<ref name=Therrien2005/>{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=112}} Its ] have a flat chewing surface, but not to the same extent as the coyote, whose diet contains more vegetable matter.<ref name=Paquet2003/> Females tend to have narrower muzzles and foreheads, thinner necks, slightly shorter legs, and less massive shoulders than males.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|p=23}} | |||

| Wolves typically reach ] after two or three years, at which point many of them will feel compelled to leave their birth packs and search out mates and territories of their own. Wolves that reach maturity generally live between 6 and 9 years in the ], although in ] they can live to be twice that age. High ]s result in a relatively low life expectancy for wolves on an overall basis. Pups die when food is scarce; they can also fall prey to other predators such as bears, or, less likely, coyotes, foxes, or other wolves. The most significant mortality factors for grown wolves are hunting and ] by humans, ]s, and wounds suffered while hunting prey. Wolves are susceptible to the same infections that affect domestic dogs, such as ], ], ] and ], and such diseases can become ], drastically reducing the wolf population in an area. | |||

| ], Italy]] | |||

| Adult wolves measure {{cvt|105|–|160|cm}} in length and {{cvt|80|–|85|cm}} at shoulder height.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} The tail measures {{cvt|29|–|50|cm}} in length, the ears {{cvt|90|-|110|mm}} in height, and the hind feet are {{cvt|220|-|250|mm}}.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|p=174}} The size and weight of the modern wolf increases proportionally with latitude in accordance with ].<ref name=Miklosi2015/> The mean body mass of the wolf is {{cvt|40|kg}}, the smallest specimen recorded at {{cvt|12|kg}} and the largest at {{cvt|79.4|kg}}.<ref name=Macdonald2001/>{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} On average, European wolves weigh {{cvt|38.5|kg}}, North American wolves {{cvt|36|kg}}, and Indian and ] {{cvt|25|kg}}.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|p=19}} Females in any given wolf population typically weigh {{cvt|5|–|10|lb|kg}} less than males. Wolves weighing over {{cvt|54|kg}} are uncommon, though exceptionally large individuals have been recorded in Alaska and Canada.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|p=18}} In central Russia, exceptionally large males can reach a weight of {{cvt|69|-|79|kg}}.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|p=174}} | |||

| == Behavior == | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| === |

=== Pelage === | ||

| {{seealso|Dog communication}} | |||

| ], northern India]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The wolf has very dense and fluffy winter fur, with a short ] and long, coarse ]s.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} Most of the undercoat and some guard hairs are shed in spring and grow back in autumn.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|p=19}} The longest hairs occur on the back, particularly on the front quarters and neck. Especially long hairs grow on the shoulders and almost form a crest on the upper part of the neck. The hairs on the cheeks are elongated and form tufts. The ears are covered in short hairs and project from the fur. Short, elastic and closely adjacent hairs are present on the limbs from the ]s down to the ]s.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} The winter fur is highly resistant to the cold. Wolves in northern climates can rest comfortably in open areas at {{convert|-40|C|F|abbr=on}} by placing their muzzles between the rear legs and covering their faces with their tail. Wolf fur provides better insulation than dog fur and does not collect ice when warm breath is condensed against it.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|p=19}} | |||

| Wolves can visually ] an impressive variety of expressions and moods that range from subtler signals – such as a slight shift in weight – to the more obvious ones – like rolling on the back as a sign of complete submission.<ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Wolfdancer Holding Company | work= Communication | url= http://www.wolfdancer.org/communication/ | accessdate=August 21 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> | |||

| In cold climates, the wolf can reduce the flow of blood near its skin to conserve body heat. The warmth of the foot pads is regulated independently from the rest of the body and is maintained at just above ] point where the pads come in contact with ice and snow.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|pp=19–20}} In warm climates, the fur is coarser and scarcer than in northern wolves.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} Female wolves tend to have smoother furred limbs than males and generally develop the smoothest overall coats as they age. Older wolves generally have more white hairs on the tip of the tail, along the nose, and on the forehead. Winter fur is retained longest by lactating females, although with some hair loss around their teats.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|p=23}} Hair length on the middle of the back is {{cvt|60|–|70|mm}}, and the guard hairs on the shoulders generally do not exceed {{cvt|90|mm}}, but can reach {{cvt|110|–|130|mm}}.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} | |||

| * '''Dominance''' – A dominant wolf stands stiff legged and tall. The ]s are erect and forward, and the ] bristle slightly. Often the tail is held vertical and curled toward the back. This display shows the wolf's rank to all others in the pack. A dominant lupine may stare penetratingly at a submissive one, pin it to the ground, "ride up" on its shoulders, or even stand on its hind legs. | |||

| ] Zoo, France]] | |||

| * '''Submission (active)''' – In active submission, the entire body is lowered, and the lips and ears are drawn back. Sometimes active submission is accompanied by muzzle licking, or the rapid thrusting out of the ] and lowering of the hindquarters. The tail is placed down, or halfway or fully between the legs, and the muzzle often points up to the more dominant animal. The back may be partially arched as the submissive wolf humbles itself to its superior. (A more arched back and more tucked tail indicate a greater level of submission.) | |||

| *'''Submission (passive)''' – Passive submission is more intense than active submission. The wolf rolls on its back and exposes its vulnerable ] and underside. The paws are drawn into the body. This is often accompanied by whimpering. | |||

| * '''Anger''' – An angry lupine's ears are erect, and its fur bristles. The lips may curl up or pull back, and the incisors are displayed. The wolf may also ]. | |||

| *'''Fear''' – A frightened wolf tries to make its body look small and therefore less conspicuous. The ears flatten down against the head, and the tail may be tucked between the legs, as with a submissive wolf. There may also be whimpering or barks of fear, and the wolf may arch its back. | |||

| *'''Defensive''' – A defensive wolf flattens its ears against its head. | |||

| *'''Aggression''' – An aggressive wolf snarls and its fur bristles. The wolf may crouch, ready to attack if necessary. | |||

| *'''Suspicion''' – Pulling back of the ears shows a lupine is suspicious. In addition, the wolf narrows its eyes. The tail of a wolf that senses danger points straight out, parallel to the ground. | |||

| *'''Relaxedness''' – A relaxed wolf's tail points straight down, and the wolf may rest ]like or on its side. The wolf's tail may also wag. The further down the tail droops, the more relaxed the wolf is. | |||

| *'''Tension''' – An aroused wolf's tail points straight out, and the wolf may crouch as if ready to spring. | |||

| *'''Happiness''' – As dogs do, a lupine may wag its tail if it is in a joyful mood. The tongue may loll out of the mouth. | |||

| *'''Hunting''' – A wolf that is hunting is tensed, and therefore the tail is horizontal and straight. | |||

| *'''Playfulness''' – A playful lupine holds its tail high and wags it. The wolf may ] and dance around, or bow by placing the front of its body down to the ground, while holding the rear high, sometimes wagged. This is reminiscent of the playful behavior executed in domestic dogs. | |||

| A wolf's coat colour is determined by its guard hairs. Wolves usually have some hairs that are white, brown, grey and black.<ref name=Gipson2002/> The coat of the Eurasian wolf is a mixture of ]ous (yellow to orange) and ] ochreous (orange/red/brown) colours with light grey. The muzzle is pale ochreous grey, and the area of the lips, cheeks, chin, and throat is white. The top of the head, forehead, under and between the eyes, and between the eyes and ears is grey with a reddish film. The neck is ochreous. Long, black tips on the hairs along the back form a broad stripe, with black hair tips on the shoulders, upper chest and rear of the body. The sides of the body, tail, and outer limbs are a pale dirty ochreous colour, while the inner sides of the limbs, belly, and groin are white. Apart from those wolves which are pure white or black, these tones vary little across geographical areas, although the patterns of these colours vary between individuals.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=168–169}} | |||

| === Howling === | |||

| ] at Little America Flats.]] | |||

| Wolves howl for several reasons. Howling helps pack members keep in touch, allowing them to effectively communicate in thickly ]ed areas or over great distances. Furthermore, howling helps to summon pack members to a specific location.<ref><span class="plainlinks">Fred H. Harrington. "."'' What's in a Howl?'' Accessed on ], ].</span></ref> Howling can also serve as a declaration of territory, as portrayed by a dominant wolf's tendency to respond to a human imitation of a "rival" individual in an area that the wolf considers its own. This behavior is also stimulated when a pack has something to protect, such as a fresh kill. As a ], large packs will more readily draw attention to themselves than will smaller packs. Adjacent packs may respond to each others' howls, which can mean trouble for the smaller of the two. Thus, wolves tend to howl with great care. | |||

| In North America, the coat colours of wolves follow ], wolves in the Canadian arctic being white and those in southern Canada, the U.S., and Mexico being predominantly grey. In some areas of the ] of Alberta and British Columbia, the coat colour is predominantly black, some being blue-grey and some with silver and black.<ref name=Gipson2002/> Differences in coat colour between sexes is absent in Eurasia;{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|p=168}} females tend to have redder tones in North America.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|p=22}} ] in North America acquired their colour from wolf-dog admixture after the first arrival of dogs across the Bering Strait 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.<ref name=Anderson2009/> Research into the inheritance of white colour from dogs into wolves has yet to be undertaken.<ref name=Hedrick2009/> | |||

| Wolves will also howl for communal reasons. Some ]s speculate that such group sessions strengthen the wolves' social bonds and camaraderie—similar to community ] among humans. During such choral sessions, wolves will howl at different ]s and varying ]es, which tends to prevent a listener from accurately estimating the number of wolves involved. This concealment of numbers makes a listening rival pack wary of what action to take. For example, confrontation could mean bad news if the rival pack gravely underestimates the howling pack's numbers. | |||

| == Ecology == | |||

| Observations of wolf packs suggest that howling occurs most often during the ] hours, preceding the adults' departure to the hunt and following their return. Studies also show that wolves howl more frequently during the ] and subsequent rearing process. The pups themselves begin howling towards the end of July, and can be provoked into howling sessions relatively easily over the following two months. Such indiscriminate howling usually has a communicative intent, and has no adverse consequences so early in a wolf's life. Howling becomes less indiscriminate as wolves learn to distinguish howling pack members from rival wolves. | |||

| === Distribution and habitat === | |||

| {{Main|Wolf distribution}} | |||

| === Other vocalizations === | |||

| ] in a mountainous habitat in the ] in ], Italy]] | |||

| ]ing, used in tandem with bared teeth, is the most visual and effective warning wolves use. Wolf growls have a distinct, deep, bass-like quality, and are used much of the time as a threat, though they are not always necessarily used for defense. Wolves will also growl at other wolves while being aggressively dominant. | |||

| Wolves occur across Eurasia and North America. However, deliberate human persecution because of livestock predation and fear of attacks on humans has reduced the wolf's range to about one-third of its historic range; the wolf is now ] (locally extinct) from much of its range in Western Europe, the United States and Mexico, and completely in the ] and Japan. In modern times, the wolf occurs mostly in wilderness and remote areas. The wolf can be found between sea level and {{convert|3000|m|feet|abbr=on}}. Wolves live in forests, inland ]s, ]s, ]s (including Arctic ]), ]s, deserts, and rocky peaks on mountains.<ref name="iucn status 2 June 2024" /> Habitat use by wolves depends on the abundance of prey, snow conditions, livestock densities, road densities, human presence and ].<ref name=Paquet2003/> | |||

| Wolves can also bark, which they do when nervous or to warn other wolves of danger. Wolves bark very discreetly, and will not generally bark loudly or repeatedly as dogs do; rather, they use a low-key, breathy "whuf" sound to get attention immediately from other wolves. Wolves will also "bark-howl" by adding a brief howl to the end of a bark. Wolves bark-howl for the same reasons they normally bark. Actually, pups bark and bark-howl much more frequently than adults, using such vocalizations as cries for attention, care, or food. | |||

| === Diet === | |||

| Wolves can also whimper, which they usually do only while submitting to other wolves. Wolf pups will whimper when they need a reassurance of security from their parents or other wolves. | |||

| ] hindquarter, ], ]]] | |||

| === Scent marking === | |||

| Wolves, like other canines, use ] to lay claim to anything from territory to fresh kills. Alpha wolves scent mark the most often, with males doing so more than females. The most widely used scent marker is urine. Male alpha wolves urine-mark objects using a raised-leg stance (all females squat) so as to enforce rank and territory. They will also use such marks to identify food caches and to claim kills on behalf of the whole pack. Defecation markers are used for the same purposes as urine marks, and serve as a more visual warning, as well. These types of scent markings are particularly useful for navigational purposes, keeping the pack from traversing the same terrain too often while also allowing each individual to be aware of the whereabouts of its pack members. Above all, though, scent marking is used to notify other wolves and packs that a given territory is occupied, and that they should therefore tread cautiously. | |||

| Like all land mammals that are ]s, the wolf feeds predominantly on ] that can be divided into large size {{cvt|240|–|650|kg}} and medium size {{cvt|23|–|130|kg}}, and have a body mass similar to that of the combined mass of the ] members.<ref name=Earle1987/><ref name=Sorkin2008/> The wolf specializes in preying on the vulnerable individuals of large prey,<ref name=Paquet2003/> with a pack of 15 able to bring down an adult ].<ref name=Mech1966/> The variation in diet between wolves living on different continents is based on the variety of hoofed mammals and of available smaller and domesticated prey.<ref name=Newsome2016/> | |||

| Wolves have ]s all over their bodies, including at the base of the ], between toes, and in the ], ], and ]. Pheromones secreted by these glands identify each individual wolf. A dominant wolf will "rub" his or her body against subordinate wolves to mark such individuals as being members of a particular pack. Wolves may also "paw" dirt to release pheromones in lieu of urine marking. | |||

| In North America, the wolf's diet is dominated by wild large hoofed mammals (ungulates) and medium-sized mammals. In Asia and Europe, their diet is dominated by wild medium-sized hoofed mammals and domestic species. The wolf depends on wild species, and if these are not readily available, as in Asia, the wolf is more reliant on domestic species.<ref name=Newsome2016/> Across Eurasia, wolves prey mostly on ], ], ] and ].{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=107}} In North America, important range-wide prey are ], moose, ], ] and ].{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=109–110}} Prior to their extirpation from North America, ]s were among the most frequently consumed prey of North American wolves.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Landry |first1=Zoe |last2=Kim |first2=Sora |last3=Trayler |first3=Robin B. |last4=Gilbert |first4=Marisa |last5=Zazula |first5=Grant |last6=Southon |first6=John |last7=Fraser |first7=Danielle |date=1 June 2021 |title=Dietary reconstruction and evidence of prey shifting in Pleistocene and recent gray wolves (Canis lupus) from Yukon Territory |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S003101822100153X |journal=] |language=en |volume=571 |pages=110368 |doi=10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110368 |bibcode=2021PPP...57110368L |access-date=23 April 2024 |via=Elsevier Science Direct |issn=0031-0182}}</ref> Wolves can digest their meal in a few hours and can feed several times in one day, making quick use of large quantities of meat.{{sfn|Mech|1981|p=172}} A well-fed wolf stores fat under the skin, around the heart, intestines, kidneys, and bone marrow, particularly during the autumn and winter.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=201}} | |||

| That wolves rely so heavily on odoriferous signals testifies greatly to their ] capabilities. Wolves can pick up any scent, including marks, from great distances, and can distinguish among them just as well or better than humans can distinguish other humans visually. | |||

| Nonetheless, wolves are not fussy eaters. Smaller-sized animals that may supplement their diet include ]s, ]s, ]s and smaller carnivores. They frequently eat ] and their eggs. When such foods are insufficient, they prey on ]s, ]s, ]s, and large insects when available.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=213–231}} Wolves in some areas may consume fish and even marine life.<ref name=Gable2018/><ref name=Woodford2019/><ref name=McAllister2007/> Wolves also consume some plant material. In Europe, they eat apples, pears, ], melons, ] and ]. In North America, wolves eat ] and ]. They also eat grass, which may provide some vitamins, but is most likely used mainly to induce vomiting to rid themselves of intestinal parasites or long guard hairs.<ref name=Fuller2019/> They are known to eat the berries of ], ], ], ], ], grain crops, and the shoots of reeds.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=213–231}} | |||

| == Social structure and hunting == | |||

| In times of scarcity, wolves will readily eat ].{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=213–231}} In Eurasian areas with dense human activity, many wolf populations are forced to subsist largely on livestock and garbage.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=107}} As prey in North America continue to occupy suitable habitats with low human density, North American wolves eat livestock and garbage only in dire circumstances.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=109}} ] is not uncommon in wolves during harsh winters, when packs often attack weak or injured wolves and may eat the bodies of dead pack members.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=213–231}}{{sfn|Mech|1981|p=180}}<ref name=Klein1995/> | |||

| === The pack === | |||

| Wolves function as social ]s and hunt in ]s organized according to strict, rank-oriented ]. It was originally thought that this comparatively high level of social organization had more to do with hunting success, and while this still may be true to a certain extent, emerging ] suggest that the pack has less to do with ] and more to do with ] success. | |||

| === Interactions with other predators === | |||

| The pack is led by the two individuals that sit atop the social hierarchy — the alpha male and the alpha female. The alpha pair (of whom only one may be the "top" alpha) has the greatest amount of social freedom compared to the rest of the pack, but they are not "leaders" in the human sense of the term. The alphas do not give the other wolves orders; rather, they simply have the most freedom in choosing where to go, what to do, and when to do it. Possessing strong instincts for fellowship, the rest of the pack usually follows. | |||

| Wolves typically dominate other canid species in areas where they both occur. In North America, incidents of wolves killing coyotes are common, particularly in winter, when coyotes feed on wolf kills. Wolves may attack coyote den sites, digging out and killing their pups, though rarely eating them. There are no records of coyotes killing wolves, though coyotes may chase wolves if they outnumber them.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=266–268}} According to a press release by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1921, the infamous ] relied on coyotes to accompany him and warn him of danger. Though they fed from his kills, he never allowed them to approach him.<ref name=Merrit1921/> Interactions have been observed in Eurasia between wolves and golden jackals, the latter's numbers being comparatively small in areas with high wolf densities.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}}{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=266–268}}<ref name=Giannatos2004/> Wolves also kill ], ] and ]es, usually in disputes over carcasses, sometimes eating them.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}}{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=269}} | |||

| While most alpha pairs are ] with each other, there are exceptions.<ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Wolf Trust | work= Wolf Family Life | url= http://www.wolftrust.org.uk/a-reproduction.html | accessdate=August 21 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> An alpha animal may preferentially ] with a lower-ranking animal, especially if the other alpha is closely related (a brother or sister, for example). The death of one alpha does not affect the status of the other alpha, who will quickly take another mate. | |||

| ] | |||

| ]s typically dominate wolf packs in disputes over carcasses, while wolf packs mostly prevail against bears when defending their den sites. Both species kill each other's young. Wolves eat the brown bears they kill, while brown bears seem to eat only young wolves.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=261–263}} Wolf interactions with ]s are much rarer because of differences in habitat preferences. Wolves have been recorded on numerous occasions actively seeking out American black bears in their dens and killing them without eating them. Unlike brown bears, American black bears frequently lose against wolves in disputes over kills.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=263–264}} Wolves also dominate and sometimes kill ]s, and will chase off those that attempt to scavenge from their kills. Wolverines escape from wolves in caves or up trees.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=266}} | |||

| Usually, only the alpha pair is able to successfully ] a litter of pups (other wolves in a pack may breed, but will usually lack the resources required to raise the pups to ]). All the wolves in the pack assist in raising wolf pups. Some mature individuals, usually females, may choose to stay in the original pack so as to reinforce it and help rear more pups. Most, males particularly, will disperse, however. | |||

| Wolves may interact and compete with ], such as the ], which may feed on smaller prey where wolves are present{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=265}} and may be suppressed by large wolf populations.<ref name=Sunquist2002/> Wolves encounter ]s along portions of the Rocky Mountains and adjacent mountain ranges. Wolves and cougars typically avoid encountering each other by hunting at different elevations for different prey (]). This is more difficult during winter. Wolves in packs usually dominate cougars and can steal their kills or even kill them,{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=264–265}} while one-to-one encounters tend to be dominated by the cat, who likewise will kill wolves.<ref name=Jimenez2008/> Wolves more broadly affect cougar population dynamics and distribution by dominating territory and prey opportunities and disrupting the feline's behaviour.<ref name=Elbroch2015/> Wolf and ] interactions are well-documented in the ], where tigers significantly depress wolf numbers, sometimes to the point of ].<ref name=Miquelle2005/>{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=265}} | |||

| The size of the pack may change over time and is controlled by several factors, including habitat, personalities of individual wolves within a pack, and ] supply. Packs can contain between two and 20 wolves, though an average pack consists of six or seven.<ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center | work= Wolf Pack Size and Food Acquisition | url= http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/mammals/wpsize/main.htm | accessdate=August 21 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref><ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Wolf Web | work= Wolf Pack | url= http://www.wolfweb.com/facts-pack.html | accessdate=August 21 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> New packs are formed when a wolf leaves its birth pack and claims a ]. Lone wolves searching for other individuals can travel very long distances seeking out suitable territories. Dispersing individuals must avoid the territories of other wolves because intruders on occupied territories are chased away or killed, a behavior that may explain wolf "predation" of dogs. Most dogs, except perhaps large, specially bred ], do not stand much of a chance against a pack of wolves protecting its territory from an unwanted intrusion. | |||

| In Israel, Palestine, Central Asia and India wolves may encounter ]s, usually in disputes over carcasses. Striped hyenas feed extensively on wolf-killed carcasses in areas where the two species interact. One-to-one, hyenas dominate wolves, and may prey on them,<ref name=Monchot2010/> but wolf packs can drive off single or outnumbered hyenas.<ref name=Mills1998/><ref name=Nayak2015/> There is at least one case in Israel of a hyena associating and cooperating with a wolf pack.<ref name=Dinets2016/> | |||

| === Hierarchy === | |||

| The hierarchy – led by the alpha male and female – affects all activity in the pack to some extent. In most larger packs, there are two separate ] in addition to an overbearing one: the first consists of the males, led by the alpha male, and the other consists of the females, led by the alpha female. In this situation, the alpha male usually assumes the "top" alpha position, though alpha females have been known to take control over entire packs in some cases. The male and female hierarchies are interdependent, and are maintained constantly by aggressive and elaborate displays of dominance and submission. | |||

| ===Infections=== | |||

| After the alpha pair, there may also, especially in larger packs, be a beta wolf or wolves – a "second-in-command" to the alphas. Betas typically assume a more prominent role in assisting with the upbringing of the alpha pair's litter, often serving as ]s or fathers while the alpha pair is away. Beta wolves are the most likely to challenge their superiors for the role of the alpha, though some betas seem content with being second, and will sometimes even let lower ranking wolves ] them for the position of alpha should circumstances necessitate such a happening (death of the alpha, etc.). More ambitious beta wolves, however, will only wait so long before challenging for the top spot; unless, of course, they choose to disperse and create their own pack instead. | |||

| {{main|Parasites and pathogens of wolves}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]s carried by wolves include: ], ], ], ], ], and ]. In wolves, the ] for rabies is eight to 21 days, and results in the host becoming agitated, deserting its pack, and travelling up to {{convert|80|km|mi|abbr=on|sigfig=1}} a day, thus increasing the risk of infecting other wolves. Although canine distemper is lethal in dogs, it has not been recorded to kill wolves, except in Canada and Alaska. The canine parvovirus, which causes death by ], ], and ] shock or ], is largely survivable in wolves, but can be lethal to pups.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=208–211}} ] carried by wolves include: ], ], ], ], ],{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=211–213}} ] and ].{{sfn|Graves|2007|pp=77–85}} Although lyme disease can debilitate individual wolves, it does not appear to significantly affect wolf populations. Leptospirosis can be contracted through contact with infected prey or urine, and can cause ], ], vomiting, ], ], ], and death.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=211–213}} | |||

| Wolves are often infested with a variety of ] exoparasites, including ]s, ]s, ], and ]s. The most harmful to wolves, particularly pups, is the mange mite ('']''),{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=202–208}} though they rarely develop full-blown ], unlike foxes.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} Endoparasites known to infect wolves include: ]s and ]s (], ]s, ]s and ]s). Most fluke species reside in the wolf's intestines. Tapeworms are commonly found in wolves, which they get though their prey, and generally cause little harm in wolves, though this depends on the number and size of the parasites, and the sensitivity of the host. Symptoms often include ], toxic and ]s, irritation of the ], and ]. Wolves can carry over 30 roundworm species, though most roundworm infections appear benign, depending on the number of worms and the age of the host.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=202–208}} | |||

| Loss of rank can happen gradually or suddenly. An older wolf may simply choose to give way when a ] challenger presents itself, yielding its position without bloodshed. On the other hand, the challenged individual may choose to fight back, with varying degrees of intensity. While the majority of wolf ] is non-damaging and ritualized, a high-stakes fight can easily result in ] for either or both parties. The loser of such a confrontation is frequently chased away from the pack or, rarely, may be killed as other aggressive wolves contribute to the insurgency. This kind of dominance encounter is more common during the mating season. | |||

| == Behaviour == | |||

| Rank order within a pack is established and maintained through a series of ] ] and posturing best described as ''ritual bluffing''. Wolves prefer ] to physical confrontations, meaning that high-ranking status is based more on ] or attitude than on size or ]. Rank, who holds it, and how it is enforced varies widely between packs and between individual animals. In large packs full of easygoing wolves, or in a group of ] wolves, rank order may shift almost constantly, or even be circular (e.g., animal A dominates animal B, who dominates animal C, who dominates animal A). | |||

| {{anchor|Behaviour}} | |||

| In a more typical pack, however, only one wolf will assume the role of the omega – the lowest-ranking member of a pack.<ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Wolf Country | work= The Wolf Pack | url= http://www.wolfcountry.net/information/WolfPack.html | accessdate=August 20 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> These individuals absorb the greatest amount of aggression from the rest of the pack, and may be subjected to different forms of truculence at any given point – anything from constant dominance from other pack members to inimical, physical harassment. Though this arrangement may seem objectionable after cursory analysis, the nature of pack dynamics demands that one wolf be at the bottom of the ranking order, and such individuals are perhaps better suited for constant displays of active and passive submission than they are for living alone. For wolves, camaraderie – no matter what the form – is preferable to solitude, and, indeed, submissive wolves tend to choose low rank over potential ]. | |||

| {{See also|Dog behaviour}} | |||

| === |

=== Social structure === | ||

| {{See also|Pack (canine)#Pack behavior in grey wolves}} | |||

| Packs of wolves cooperatively hunt any large ]s in their range, whereas lone wolves are limited to consuming smaller animals due to their relative inability to catch anything larger. Pack hunting methods range from surprise attacks to long-lasting chases, though they strongly favor the latter. Through meticulous cooperation, a pack of wolves is able to pursue large prey for several hours before relenting, though the success rate of such chases is rather low. Solitary wolves depend on small animals, capturing them by pouncing and pinning them to the ground with their front paws – a common technique among canids such as ]es and ]s. Wolves' diets include, but are not limited to, ], ], ], ], and other large ]s. They also prey on rodents and small animals in a limited manner, as a typical wolf requires between 1.3 to 4.5 kg (3 and 10 lb) of meat per day for sustenance; however, this certainly doesn't mean that a wolf will get the chance to eat everyday. In fact, wolves rarely eat on a daily basis, and so they make up for this by eating up to 9 kg (20 lb) of meat when they get the chance. <ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Smithsonian National Zoological Park | work= Gray Wolf Facts | url=http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Animals/NorthAmerica/Facts/fact-graywolf.cfm | accessdate=August 15 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] standing its ground. By doing so, it avoids playing to the collective strength of the wolf pack (running), thereby increasing its chance for survival.]] | |||

| When pursuing large prey, wolves generally attack from all angles, targeting the necks and sides of such animals. Wolf packs ] large ]s of prey species by inducing a ], thereby picking and ganging up on an individual that they perceive to be less ]. Less fit animals typically include the elderly, ]d, and young, and though these individuals are among the most likely to fall victim to predation, healthy animals may also succumb through circumstance or by chance. Hence, while wolves are certainly capable of culling the least fit from the communities of animals upon which they prey, the process certainly doesn't target the feeble or the ill-suited to an outright degree. Healthy, fit individuals will stand their ground against wolves, and are simply better able to effectively defend themselves, increasing the possibility of injury for the wolves involved. Realizing this, wolves are not likely to spend much time testing, chasing, or harassing such individuals. ] dictates that these ]s are much more useful against lame, young, or old prey animals, and so it is these individuals that are most likely to fall to wolf ]. Even so, pack hunting efforts are usually fruitless. In one study, less than 1 out of 10 chases of ] resulted in a successful kill.<ref>{{cite web | author=Mary Taylor Young | title=Colorado's Wildlife Company | work=CWC Summer 2004: A Wolf Primer | url=http://wildlife.state.co.us/Colo_Wild_Co/sum2004/WolfPrimer.htm | accessdate=August 15 | accessyear=2005 }}</ref> Therefore, wolves must hunt almost constantly to sustain themselves. | |||

| The wolf is a ].{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} Its populations consist of packs and lone wolves, most lone wolves being temporarily alone while they disperse from packs to form their own or join another one.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=164}} The wolf's basic social unit is the ] consisting of a ] accompanied by their offspring.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} The average pack size in North America is eight wolves and 5.5 in Europe.<ref name=Miklosi2015/> The average pack across Eurasia consists of a family of eight wolves (two adults, juveniles, and yearlings),{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} or sometimes two or three such families,<ref name=Paquet2003/> with examples of exceptionally large packs consisting of up to 42 wolves being known.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=2–3, 28}} ] levels in wolves rise significantly when a pack member dies, indicating the presence of stress.<ref name=Molnar2015/> During times of prey abundance caused by calving or migration, different wolf packs may join together temporarily.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} | |||

| Wolves, like many other keystone predators, are somewhat sensitive to fluctuations in prey abundance, making them likely to experience minor changes within their own populations as the abundance of their primary prey species gradually rises and drops over long periods of time. This balance between wolves and their prey prevents the mass ] of all species involved. | |||

| Offspring typically stay in the pack for 10–54 months before dispersing.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=1–2}} Triggers for dispersal include the onset of ] and competition within the pack for food.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=12–13}} The distance travelled by dispersing wolves varies widely; some stay in the vicinity of the parental group, while other individuals may travel great distances of upwards of {{convert|206|km|mi|abbr=on}}, {{convert|390|km|mi|abbr=on}}, and {{convert|670|km|mi|abbr=on}} from their natal (birth) packs.<ref name=Nowak1983/> A new pack is usually founded by an unrelated dispersing male and female, travelling together in search of an area devoid of other hostile packs.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=38}} Wolf packs rarely adopt other wolves into their fold and typically kill them. In the rare cases where other wolves are adopted, the adoptee is almost invariably an immature animal of one to three years old, and unlikely to compete for breeding rights with the mated pair. This usually occurs between the months of February and May. Adopted males may mate with an available pack female and then form their own pack. In some cases, a lone wolf is adopted into a pack to replace a deceased breeder.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=2–3, 28}} | |||

| == Historical perceptions == | |||

| Wolves are ] and generally establish territories far larger than they require to survive assuring a steady supply of prey. Territory size depends largely on the amount of prey available and the age of the pack's pups. They tend to increase in size in areas with low prey populations,<ref name=Jedrzejewski2007/> or when the pups reach the age of six months when they have the same nutritional needs as adults.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=19–26}} Wolf packs travel constantly in search of prey, covering roughly 9% of their territory per day, on average {{cvt|25|km/d}}. The core of their territory is on average {{cvt|35|km2}} where they spend 50% of their time.<ref name=Jedrzejewski2007/> Prey density tends to be much higher on the territory's periphery. Wolves tend to avoid hunting on the fringes of their range to avoid fatal confrontations with neighbouring packs.<ref name=Mech1977/> The smallest territory on record was held by a pack of six wolves in northeastern Minnesota, which occupied an estimated {{cvt|33|km2}}, while the largest was held by an Alaskan pack of ten wolves encompassing {{cvt|6,272|km2}}.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=19–26}} Wolf packs are typically settled, and usually leave their accustomed ranges only during severe food shortages.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} Territorial fights are among the principal causes of wolf mortality, one study concluding that 14–65% of wolf deaths in Minnesota and the ] were due to other wolves.<ref name=Mech2003/> | |||

| === Summary === | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The relationship between humans and wolves has had a very long and turbulent ]. Traditionally, humans have viewed wolves negatively, perceiving them to be dangerous or as nuisances to be destroyed. European ] exacerbated this negative image, which was brought over to ] as it was settled. In brief, the gray wolf, which, at one point, could be found in any ecosystem on every ] in the ], was persistently one of the first species to go once a significant population of humans settled in a given area. As ] made the killing of wolves and other predators easier, simple control became something more like complete annihilation. | |||

| ===Communication=== | |||

| Historically, baseless fear of the wolf has been responsible for most of the trouble the species has received, including why it was nearly hunted out of existence in the U.S. and Europe prior to the twentieth century. However, ecological research conducted during the 20th century shed new light on wolves and other predators, specifically with regard to the critical role they play in maintaining the ecosystems to which they belong. As a result of this and other important factors, wolves have come to be viewed in a much more realistic, equitable way. | |||

| {{main article|Wolf communication}} | |||

| {{listen | |||

| | filename = Wolf howls.ogg | |||

| | title = Wolves howling | |||

| | format = ] | |||

| | filename2 = rallying.ogg | |||

| | title2 = Rallying cry | |||

| | format2 = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| Wolves communicate using vocalizations, body postures, scent, touch, and taste.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=66–103}} The phases of the moon have no effect on wolf vocalization, and despite popular belief, wolves do not howl at the Moon.{{sfn|Busch|2007|p=59}} Wolves ] to assemble the pack usually before and after hunts, to pass on an alarm particularly at a den site, to locate each other during a storm, while crossing unfamiliar territory, and to communicate across great distances.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|p=38}} Wolf howls can under certain conditions be heard over areas of up to {{cvt|130|km2}}.<ref name=Paquet2003/> Other vocalizations include ], ] and whines. Wolves do not bark as loudly or continuously as dogs do in confrontations, rather barking a few times and then retreating from a perceived danger.{{sfn|Lopez|1978|pp=39–41}} Aggressive or self-assertive wolves are characterized by their slow and deliberate movements, high body ] and raised ], while submissive ones carry their bodies low, flatten their fur, and lower their ears and tail.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=90}} | |||

| Scent marking involves urine, feces, and ] and anal gland scents. This is more effective at advertising territory than howling and is often used in combination with scratch marks. Wolves increase their rate of scent marking when they encounter the marks of wolves from other packs. Lone wolves will rarely mark, but newly bonded pairs will scent mark the most.<ref name=Paquet2003/> These marks are generally left every {{cvt|240|m}} throughout the territory on regular travelways and junctions. Such markers can last for two to three weeks,{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=19–26}} and are typically placed near rocks, boulders, trees, or the skeletons of large animals.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=164–270}} Raised leg ] is considered to be one of the most important forms of scent communication in the wolf, making up 60–80% of all scent marks observed.<ref name=Peters1975/> | |||

| A general environmental awareness began to take root sometime in the middle of the ] that forced people to re-think former notions, including those regarding predators. In North America, people realized that in over one hundred years of documentation, there had been no verified human ] caused by an attack from a healthy wolf. Eventually, they found out that wolves, being naturally cautious and rightfully wary of humans, will almost always flee, perhaps only carefully approaching a person out of curiosity. In fact, it is likely that any documented wolf attack (of any severity) to this date was, actually, from a ] dog, a ] individual, or the result of some sort of human provocation.<ref><span class="plainlinks">{{cite web | title= Natures Wolves | work= Wolf Attacks On Humans | url= http://www.natureswolves.com/human/aws_wolfattacks.htm | accessdate=October 31 | accessyear=2005 }}</span></ref> | |||

| === Reproduction{{anchor|Reproduction_and_development}} === | |||

| While progress has been made, traditional ]s prove difficult to change in some cases. Today and in the past, improved understanding and ] have been the main allies in altering perceptions. As research improves and as people figure out better ways to educate people about the true nature of this planet's ecosystems, public acceptance of the wolf as an integral member of the earth's biological society will likely prevail. | |||

| {{See also|Canine reproduction}} | |||

| === Wolves in folklore === | |||

| ], Japan]] | |||

| In many ancient ]s, the wolf is portrayed as being brave, honorable, or intelligent. The best examples of such portrayals are demonstrated by some of the stories of the ]. Elsewhere, the wolf was revered as the totem animal of Ancient Rome (see ] and ]). In ], the wolf was most likely associated with the ] class, and the word itself was subject to ] (the Latin ''lupus'' being an example of a mutated form of the original ] ''*wlkwos''). | |||

| Wolves are ], mated pairs usually remaining together for life. Should one of the pair die, another mate is found quickly.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|p=248}} With wolves in the wild, inbreeding does not occur where outbreeding is possible.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=5}} Wolves become mature at the age of two years and sexually mature from the age of three years.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|p=248}} The age of first breeding in wolves depends largely on environmental factors: when food is plentiful, or when wolf populations are heavily managed, wolves can rear pups at younger ages to better exploit abundant resources. Females are capable of producing pups every year, one ] annually being the average.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|p=175}} ] and ] begin in the second half of winter and lasts for two weeks.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|p=248}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] pups stimulating their mother to regurgitate some food]] | |||

| The wolf has typically assumed a more negative image in legend, however, including in most of modern western folklore. Specifically, the wolf has often been portrayed as a creature to be feared. Two iconic examples of this image are the ] and the ] (a human that transforms into a wolf by means of magic or a curse, and who is shunned and reviled by the rest of society). ] prominently includes three malevolent wolves, in particular: the giant ], eldest child of ] and ] who was feared and hated by the ], and Fenrisulfr's children, ] and ], who, according to legend, will devour the sun and moon at ]. | |||

| Dens are usually constructed for pups during the summer period. When building dens, females make use of natural shelters like fissures in rocks, cliffs overhanging riverbanks and holes thickly covered by vegetation. Sometimes, the den is the appropriated burrow of smaller animals such as foxes, badgers or marmots. An appropriated den is often widened and partly remade. On rare occasions, female wolves dig burrows themselves, which are usually small and short with one to three openings. The den is usually constructed not more than {{cvt|500|m}} away from a water source. It typically faces southwards where it can be better warmed by sunlight exposure, and the snow can thaw more quickly. Resting places, play areas for the pups, and food remains are commonly found around wolf dens. The odor of urine and rotting food emanating from the denning area often attracts scavenging birds like ]s and ]s. Though they mostly avoid areas within human sight, wolves have been known to nest near homes, paved ]s and ]s.{{sfn|Heptner|Naumov|1998|pp=234–238}} During pregnancy, female wolves remain in a den located away from the peripheral zone of their territories, where violent encounters with other packs are less likely to occur.{{sfn|Mech|Boitani|2003|pp=42–46}} | |||

| Despite their often negative image, wolves have periodically been credited in mythology, fiction, and reality with adopting, nursing, and raising human ], with the most famous examples being ] and ] of '']'', respectively. In Mongolian mythology, the Mongols believe that they are descended from a male Gray Wolf and a white doe. In fact, the Mongols' greatest hero ] called his people 'Clan of the Gray Wolf'. | |||