| Revision as of 09:13, 21 February 2018 edit2600:1001:b11c:6ffb:211e:97e7:b386:a40e (talk)No edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:55, 5 January 2025 edit undoDicklyon (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers476,993 edits case fix | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Communist ideology developed by Joseph Stalin}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{about|the political philosophy and state ideology developed by Joseph Stalin|countries governed by Marxist–Leninist parties|Communist state|the means of governing and related policies implemented by Stalin|Stalinism|Lenin's ideology in the form that existed in Lenin's own lifetime|Leninism}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=January 2014}} | |||

| {{pp-move-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{use British English|date=August 2021}} | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=August 2021}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | total_width = 330 | |||

| | image1 = Karl Marx (6x7 cropped).png | |||

| | height1 = 317.2 | |||

| | image2 = Lenin1921 (cropped).jpeg | |||

| | height2 = 317.2 | |||

| | footer = ] (left) and ] (right), after whom Marxism–Leninism is named | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Marxism–Leninism sidebar}} | {{Marxism–Leninism sidebar}} | ||

| <noinclude>{{Joseph Stalin series|expanded=Political ideology}}</noinclude> | |||

| {{Marxism|Variants}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2017}} | |||

| '''Marxism–Leninism''' ({{Langx|ru|Марксизм-Ленинизм|Marksizm-Leninizm}}) is a ] ideology that became the largest faction of the ] in the world in the years following the ]. It was the predominant ideology of most communist governments throughout the 20th century.<ref name="Lansford">{{cite book |last=Lansford |first=Thomas |date=2007 |title=Communism |location=New York |publisher=Cavendish Square Publishing |pages=9–24, 36–44 |isbn=978-0-7614-2628-8 |quote=By 1985, one-third of the world's population lived under a Marxist–Leninist system of government in one form or another.}}</ref> It was developed in Russia by ] and drew on elements of ], ], ], and the works of ].<ref name="Lansford 2007, p. 17">{{cite book |last=Lansford |first=Thomas |title=Communism |date=2007 |publisher=Cavendish Square Publishing |isbn=978-0-7614-2628-8 |location=New York |pages=17}}</ref><ref name="Норма">{{cite book |last1=Zotov |first1=V. D. |title=Istoriya politicheskikh ucheniy. Uchebnik |last2=Zotova |first2=L. D. |publisher=Норма |year=2010 |isbn=978-5-91768-071-2 |language=ru |script-title=ru:История политических учений. Учебник |trans-title=History of political doctrines. Textbook}}</ref><ref name="Kosing 2016">{{cite book |last=Kosing |first=Alfred |title="Stalinismus". Untersuchung von Ursprung, Wesen und Wirkungen |publisher=Verlag am Park |year=2016 |isbn=978-3-945187-64-7 |location=Berlin |language=de |trans-title="Stalinism". Investigation of origin, essence and effects |author-link=:de:Alfred Kosing}}</ref> It was the state ideology of the ],{{sfn|Evans|1993|pp=1–2}} ] in the ], and various countries in the ] and ] during the ],<ref>{{cite book |last=Hanson |first=S. E. |title=] |chapter=Marxism/Leninism |year=2001 |edition=1st |isbn=978-0-08-043076-8 |pages=9298–9302 |publisher=Elsevier |doi=10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01174-8}}</ref> as well as the ] after ].{{sfn|Bottomore|1991|p=54}} | |||

| '''Marxism–Leninism''' is the ] political ideology adopted by the ] and the ]<ref>''History for the IB Diploma: Communism in Crisis 1976–89''. Allan Todd. Page 16. "Essentially, Marxism–Leninism was the 'official' ideology of the Soviet state" and all communist parties loyal to Stalin and his successors - up to 1976 and beyond."</ref> whose proponents consider to be based on ] and ]. The term was suggested by ]<ref name="made_by_stalin22">Г. Лисичкин (G. Lisichkin), Мифы и реальность, Новый мир ('']''), 1989, № 3, p. 59 {{ru icon}}</ref> and it gained wide circulation in the Soviet Union after Stalin's 1938 ''],''<ref>''],'' article "Marxism"</ref> which became an official standard textbook. | |||

| Today, Marxism–Leninism is the ideology of the ruling parties of ], ], ] and ] (all one-party ]s),{{sfn|Cooke|1998|pp=221–222}} as well as many ]. The ] of ] is derived from Marxism–Leninism,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lee |first1=Grace |year=2003 |title= The Political Philosophy of Juche |journal=Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=105–111 |url=http://www.stanford.edu/group/sjeaa/journal3/korea1.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120121003750/http://www.stanford.edu/group/sjeaa/journal3/korea1.pdf |archive-date=21 January 2012}}</ref> although its evolution is disputed. Marxist–Leninist states are commonly referred to as "]s" by Western academics.<ref>{{harvnb|Wilczynski|2008|p=21|ps=: "Contrary to Western usage, these countries describe themselves as 'Socialist' (not 'Communist'). The second stage (Marx's 'higher phase'), or 'Communism' is to be marked by an age of plenty, distribution according to needs (not work), the absence of money and the market mechanism, the disappearance of the last vestiges of capitalism and the ultimate 'whithering away' of the State."}}; {{harvnb|Steele|1999|p=45|ps=: "Among Western journalists the term 'Communist' came to refer exclusively to regimes and movements associated with the Communist International and its offspring: regimes which insisted that they were not communist but socialist, and movements which were barely communist in any sense at all."}}; {{harvnb|Rosser|Barkley Rosser|2003|p=14|ps=: "Ironically, the ideological father of communism, Karl Marx, claimed that communism entailed the withering away of the state. The dictatorship of the proletariat was to be a strictly temporary phenomenon. Well aware of this, the Soviet Communists never claimed to have achieved communism, always labeling their own system socialist rather than communist and viewing their system as in transition to communism."}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Williams |first=Raymond |title=Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society, revised edition |publisher=] |year=1983 |isbn=978-0-19-520469-8 |page= |chapter=Socialism |quote=The decisive distinction between socialist and communist, as in one sense these terms are now ordinarily used, came with the renaming, in 1918, of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) as the All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). From that time on, a distinction of socialist from communist, often with supporting definitions such as social democrat or democratic socialist, became widely current, although it is significant that all communist parties, in line with earlier usage, continued to describe themselves as socialist and dedicated to socialism. |chapter-url-access=registration |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/keywordsvocabula00willrich/page/289}}</ref> | |||

| According to its proponents, the goal of Marxism–Leninism is the development of a state into what it considers a ] through the leadership of a ] composed of professional revolutionaries, an organic part of the ] who come to ] as a result of the ] of ].{{Dubious|date=November 2017}} The socialist state, which according to Marxism–Leninism represents a "]", is primarily or exclusively governed by the party of the revolutionary vanguard through the process of ], which ] described as "diversity in discussion, unity in action".<ref name="Albert pp. 24-252">Michael Albert, Robin Hahnel. ''Socialism Today and Tomorrow''. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: South End Press, 1981. pp. 24–25.</ref> | |||

| Marxism–Leninism was developed from ] by ] in the 1920s based on his understanding and synthesis of ] and ].<ref name="Lansford 2007, p. 17"/><ref name="Норма"/><ref name="Kosing 2016"/> Marxism–Leninism holds that a ] ] is needed to replace ]. A ], organized through ], would seize power on behalf of the ] and establish a ] socialist state, called the ]. The state would control the ], suppress ], ], and the ], and promote ], to pave the way for an eventual ] that would be ] and ].<ref>{{harvnb|Cooke|1998|pp=221–222}}; {{harvnb|Morgan|2015|pp=657, 659|ps=: "Lenin argued that power could be secured on behalf of the proletariat through the so-called vanguard leadership of a disciplined and revolutionary communist party, organized according to what was effectively the military principle of democratic centralism. ... The basics of Marxism-Leninism were in place by the time of Lenin's death in 1924. ... The revolution was to be accomplished in two stages. First, a 'dictatorship of the proletariat,' managed by the élite 'vanguard' communist party, would suppress counterrevolution, and ensure that natural economic resources and the means of production and distribution were in common ownership. Finally, communism would be achieved in a classless society in which Party and State would have 'withered away'."}}; {{harvnb|Busky|2002|pp=163–165}}; {{harvnb|Albert|Hahnel|1981|pp=24–26}}; {{harvnb|Andrain|1994|p=140|ps=: "The communist party-states collapsed because they no longer fulfilled the essence of a Leninist model: a strong commitment to Marxist-Leninist ideology, rule by the vanguard communist party, and the operation of a centrally planned state socialist economy. Before the mid-1980s, the communist party controlled the military, police, mass media, and state enterprises. Government coercive agencies employed physical sanctions against political dissidents who denounced Marxism-Leninism."}}; {{harvnb|Evans|1993|p=24|ps=: "Lenin defended the dictatorial organization of the workers' state. Several years before the revolution, he had bluntly characterized dictatorship as 'unlimited power based on force, and not on law', leaving no doubt that those terms were intended to apply to the dictatorship of the proletariat. ... To socialists who accused the Bolshevik state of violating the principles of democracy by forcibly suppressing opposition, he replied: you are taking a formal, abstract view of democracy. ... The proletarian dictatorship was described by Lenin as a single-party state."}}</ref> | |||

| Through this policy, the ] (or equivalent) is the supreme political institution of the state and primary force of societal organisation. Marxism–Leninism professes its final goal as the development of ] into the full realisation of ], a classless social system with ] of the ] and with full social equality of all members of society. To achieve this goal, the communist party mainly focuses on the intensive development in industry, science and technology, which lay the basis for continual growth of the ] and therein increases the flow of material wealth.<ref name="Andrain22">Charles F. Andrain. ''Comparative Political Systems: Policy Performance and Social Change''. Armonk, New York, USA: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1994. p. 140.</ref> All land and natural resources are publicly owned and managed, with varying forms of public ownership of social institutions.<ref name="sioc33">''History for the IB Diploma: Communism in Crisis 1976–89''. Allan Todd. Page 16. "The term Marxism–Leninism, invented by Stalin, was not used until after Lenin's death in 1924. It soon came to be used in Stalin's Soviet Union to refer to what he described as 'orthodox Marxism'. This increasingly came to mean what Stalin himself had to say about political and economic issues." "However, many Marxists (even members of the Communist Party itself) believed that Stalin's ideas and practices (such as socialism in one country and the purges) were almost total distortions of what Marx and Lenin had said."</ref> | |||

| After the death of ] in 1924, Marxism–Leninism became a distinct movement in the Soviet Union when Stalin and his supporters gained control of the ]. It rejected the common notion among Western Marxists of ] as a prerequisite for building socialism, in favour of the concept of ]. According to its supporters, the gradual transition from capitalism to socialism was signified by the introduction of the ] and the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Smith |first=S. A. |date=2014 |title=The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism |location=Oxford |publisher=] |pages=126 |isbn=978-0-19-166752-7 |quote=The 1936 Constitution described the Soviet Union for the first time as a 'socialist society', rhetorically fulfilling the aim of building socialism in one country, as Stalin had promised.}}</ref> By the late 1920s, Stalin established ideological orthodoxy in the ], the Soviet Union, and the Communist International to establish universal Marxist–Leninist ].<ref name="Bullock & Trombley 506">{{cite book |editor1-last=Bullock |editor1-first=Allan |editor1-link=Alan Bullock |editor2-last=Trombley |editor2-first=Stephen |date=1999 |title=The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought |edition=3rd |pages=506 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-00-686383-0}}</ref><ref name="Lisichkin 1989, p. 59">{{cite magazine |last=Lisichkin |first=G. |date=1989 |script-title=ru:Мифы и реальность |title=Mify i real'nost' |language=ru |trans-title=Myths and reality |magazine=] |volume=3 |page=59}}</ref> The formulation of the Soviet version of ] and ] in the 1930s by Stalin and his associates, such as in Stalin's text '']'', became the official Soviet interpretation of ],{{sfn|Evans|1993|pp=52–53}} and was taken as example by Marxist–Leninists in other countries; according to the '']'', this text became the foundation of the philosophy of Marxism–Leninism.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://bigenc.ru/philosophy/text/2187362 |script-title=ru:Марксизм |title=Marksizm |language=ru |trans-title=Marxism |website=Big Russian encyclopedia – electronic version |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200323164114/https://bigenc.ru/philosophy/text/2187362 |archive-date=23 March 2020}}</ref> In 1938, Stalin's official textbook '']'' popularised ''Marxism–Leninism''.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Marxism |encyclopedia=] |pages=00}}</ref> | |||

| Other types of communists such as ] and ] have been critical of Marxism–Leninism. They argue that Marxist–Leninist states did not establish socialism, but rather ].<ref name="statecap3">, M.C. Howard and J.E. King</ref> They trace this argument back to the founders of Marxism's own comments about state ownership of property being a form of capitalism except when certain conditions are met—conditions which, in their argument, did not exist in the Marxist–Leninist states.<ref name="statecap3" /><ref>"American Capitalism: Social Thought and Political Economy in the Twentieth Century", Nelson Lichtenstein. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. p. 160-161</ref> Marxism's dictatorship of the proletariat is a democratic state form and therefore single-party rule (which the Marxist–Leninist states made use of) cannot be a dictatorship of the proletariat under the Marxist definition.<ref>The Human Rights Reader: Major Political Essays, Speeches, and Documents from Ancient Times to the Present. Micheline Ishay. Taylor & Francis, 2007. p. 245.</ref> They claim that Marxism–Leninism is neither Marxism nor Leninism nor the union of both, but rather an artificial term created to justify Stalin's ideological distortion.<ref name="sioc32">''History for the IB Diploma: Communism in Crisis 1976–89''. Allan Todd. Page 16. "The term Marxism–Leninism, invented by Stalin, was not used until after Lenin's death in 1924. It soon came to be used in Stalin's Soviet Union to refer to what he described as 'orthodox Marxism'. This increasingly came to mean what Stalin himself had to say about political and economic issues." "However, many Marxists (even members of the Communist Party itself) believed that Stalin's ideas and practices (such as socialism in one country and the purges) were almost total distortions of what Marx and Lenin had said."</ref> | |||

| The internationalism of Marxism–Leninism was expressed in supporting revolutions in other countries, initially through the Communist International and then through the concept of ] after ]. The establishment of other communist states after World War II resulted in ], and these states tended to follow the Soviet Marxist–Leninist model of ] and rapid ], political centralisation, and repression. During the Cold War, Marxism–Leninist countries like the Soviet Union and its allies were one of the major forces in ].<ref name="Columbia 2007">{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/co/communism.html |title=Communism |encyclopedia=] |edition=6th |year=2007 |access-date=29 November 2020 |archive-date=10 February 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090210050324/http://bartleby.com/65/co/communism.html |url-status=live}}</ref> With the death of Stalin and the ensuing de-Stalinisation, Marxism–Leninism underwent several revisions and adaptations such as ], ], ], ], ], and ]. More recently ]ese communist parties have adopted ]. This also caused several splits between Marxist–Leninist states, resulting in the ], the ], and the ]. The socio-economic nature of Marxist–Leninist states, especially that of the Soviet Union during the ] (1924–1953), has been much debated, varyingly being labelled a form of ], ], ], or a totally unique ].{{sfn|Sandle|1999|pp=265–266}} The Eastern Bloc, including Marxist–Leninist states in Central and Eastern Europe as well as the ] regimes, have been variously described as "bureaucratic-authoritarian systems",{{sfn|Andrain|1994|loc=Bureaucratic-Authoritarian Systems|pp=24–42}} and China's socio-economic structure has been referred to as "nationalistic state capitalism".<ref name="Morgan 1991, p. 661">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Morgan |first=W. John |date=2001 |title=Marxism-Leninism: The Ideology of Twentieth-Century Communism |editor-last=Wright |editor-first=James D. |editor-link=James D. Wright |encyclopedia=] |edition=2nd |location=Oxford |publisher=] |pages=661 |isbn=978-0-08-097087-5}}</ref> | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| {{further information|State ideology of the Soviet Union}} | |||

| Within five years of ]'s death in 1924, ] completed his rise to power in the ]. According to G. Lisichkin (1989), Stalin compiled Marxism–Leninism as a separate ideology in his book ''Concerning Questions of Leninism''.<ref name="made_by_stalin">Г. Лисичкин (G. Lisichkin), Мифы и реальность, Новый мир ('']''), 1989, № 3, p. 59 {{ru icon}}</ref> During the period of Stalin's rule in the Soviet Union, Marxism–Leninism was proclaimed the official ideology of the state.<ref>Александр Бутенко (Aleksandr Butenko), Социализм сегодня: опыт и новая теория// Журнал Альтернативы, №1, 1996, pp. 3–4 {{ru icon}}</ref> There is no definite agreement amongst historians regarding whether or not Stalin actually followed the principles established by ] and by Lenin.<ref name="stalin_follow_marx_lenin">Александр Бутенко (Aleksandr Butenko), Социализм сегодня: опыт и новая теория// Журнал Альтернативы, №1, 1996, pp. 2–22 {{ru icon}}</ref> ] in particular believe that ] contradicted authentic ] and ]<ref>Лев Троцкий (]), Сталинская школа фальсификаций, М. 1990, pp. 7–8 {{ru icon}}</ref> and they initially used the term "Bolshevik–Leninism" to describe their own ideology of anti-Stalinist communism. Though the term "Marxism–Leninism" is often used by Stalinists—those who believe that Stalin successfully carried forward Lenin's legacy—it is also used by some who repudiate the repressive aspects of Stalin's rule, such as the supporters of ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://slovari.yandex.ru/dict/bse/article/00045/73200.htm?text=%D0%BC%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BA%D1%81%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%BC-%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B7%D0%BC |script-title=ru:Марксизм-ленинизм |accessdate=2010-10-18 |author=М. Б. Митин (M. B. Mitin) |publisher=Яндекс |date= |language=ru }}{{dead link|date=June 2016|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> | |||

| Criticism of Marxism–Leninism largely overlaps with ] and mainly focuses on the actions and policies of Marxist–Leninist leaders, most notably Stalin and ]. Marxist–Leninist states have been marked by a high degree of centralised control by the state and ], ], ], ] and use of ]s, as well as ] and ], low unemployment<ref>{{Cite web |last=Eason |first=Warren W. |date=1957 |title=Labor Force Material for the Study of Unemployment in the Soviet Union |url=https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c2648/c2648.pdf }}</ref> and lower prices for ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Campbell |first1=Colin D. |last2=Campbell |first2=Rosemary G. |date=1955 |title=Soviet Price Reductions for Consumer Goods, 1948-1954 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1811636 |journal=The American Economic Review |volume=45 |issue=4 |pages=609–625 |jstor=1811636 |issn=0002-8282}}</ref> Historians such as Silvio Pons and ] stated that the repression and ] came from Marxist–Leninist ideology.{{r|service totalitarian}}{{r|service labor camps}}{{sfn|Pons|Service|2010|p=307}}{{r|pons ethnic cleansing}} Historians such as ] and ] have offered other explanations and criticise the focus on the upper levels of society and use of concepts such as totalitarianism which have obscured the reality of the system.{{r|Geyer&Fitzpatrick}} While the emergence of the Soviet Union as the world's first nominally communist state led to communism's widespread association with Marxism–Leninism and the ],{{r|Columbia 2007}}<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Ball |first1=Terence |last2=Dagger |first2=Richard |orig-date=1999 |date=2019 |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/communism |title=Communism |edition=revised |encyclopedia=] |access-date=10 June 2020 |archive-date=16 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150616023735/https://www.britannica.com/topic/communism |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Busky 2000, pp. 6–8">{{cite book |last=Busky |first=Donald F. |date=2000 |title=Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey |publisher=] |pages=6–8 |isbn=978-0-275-96886-1 |quote=In a modern sense of the word, communism refers to the ideology of Marxism-Leninism. ... he adjective ''democratic'' is added by democratic socialists to attempt to distinguish themselves from Communists who also call themselves socialists. All but communists, or more accurately, Marxist-Leninists, believe that modern-day communism is highly undemocratic and totalitarian in practice, and democratic socialists wish to emphasise by their name that they disagree strongly with the Marxist-Leninist brand of socialism.}}</ref> several academics say that Marxism–Leninism in practice was a form of state capitalism.<ref>{{harvnb|Chomsky|1986}}; {{harvnb|Howard|King|2001|pp=110–126}}; {{harvnb|Fitzgibbons|2002}}; {{harvnb|Wolff|2015}}; {{harvnb|Sandle|1999|pp=265–266}}; {{harvnb|Andrain|1994|loc=Bureaucratic-Authoritarian Systems|pp=24–42}}</ref><ref name="Morgan 1991, p. 6612">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Marxism-Leninism: The Ideology of Twentieth-Century Communism |encyclopedia=] |publisher=] |location=Oxford |date=2001 |editor-last=Wright |editor-first=James D. |editor-link=James D. Wright |edition=2nd |pages=661 |isbn=978-0-08-097087-5 |last=Morgan |first=W. John}}</ref> | |||

| After the ] of the 1960s, the communist parties of the Soviet Union and of the People's Republic of China each claimed to be the sole successor to Marxism–Leninism. In China, the claim that ] had "adapted Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions" evolved into the idea that he had updated it in a fundamental way applying to the world as a whole—consequently, the term Mao Zedong Thought (or ]) increasingly came to describe the official Chinese state ideology as well as the ideological basis of parties around the world which sympathised with the ]. After the death of Mao on 1976, Peruvian Maoists associated with the ] coined the term ], arguing that Maoism was a more advanced stage of Marxism. | |||

| == Overview == | |||

| Following the ] of the 1970s, a small portion of Marxist–Leninists began to downplay or repudiate the role of Mao in the ] in favour of the ] and a stricter adherence to Stalin. In ], Marxism–Leninism was officially superseded in 1977 by '']'', in which concepts of class and class struggle—in other words Marxism itself—play no significant role. However, the government is still sometimes referred to as Marxist–Leninist, or more commonly as Stalinist, due to its political and economic structure. In the other four existing ]s—], ], ] and ]—the ruling parties hold Marxism–Leninism as their official ideology, although they give it different interpretations in terms of practical policy. | |||

| === Communist states === | |||

| In the establishment of the ] in the former ], ] was the ideological basis. As the only legal ], it decided almost all policies, which the ] represented as correct.<ref>{{cite book |title=Gorbachev and His Reforms, 1985–1990 |date=1990 |first=Richard |last=Sakwa |author-link=Richard Sakwa |pages=206 |isbn=978-0-13-362427-4 |publisher=]}}</ref> Because ] was the revolutionary means to achieving socialism in the praxis of government, the relationship between ideology and decision-making inclined to pragmatism and most policy decisions were taken in light of the continual and permanent development of Marxism–Leninism, with ideological adaptation to material conditions.<ref>{{cite book |title=Gorbachev and His Reforms, 1985–1990 |date=1990 |first=Richard |last=Sakwa |author-link=Richard Sakwa |pages=212 |isbn=978-0-13-362427-4 |publisher=]}}</ref> The ] lost in the ], obtaining 23.3% of the vote, to the ], which obtained 37.6%.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Dando |first=William A. |date=June 1966 |title=A Map of the Election to the Russian Constituent Assembly of 1917 |journal=Slavic Review |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=314–319 |doi=10.2307/2492782 |issn=0037-6779 |jstor=2492782 |s2cid=156132823 |quote=Out of a total vote of approximately 42 million and a total of 703 elected deputies, the primarily agrarian Social Revolutionary Party, plus nationalistic '']'', or populist, parties, amassed the largest popular vote (well in excess of 50 percent) and elected the greatest number of deputies (approximately 60 percent) of all the parties involved. The Bolsheviks, who had usurped power in the name of the soviets three weeks prior to the election, amassed only 24 percent of the popular vote and elected only 24 percent of the deputies. The party of Lenin had not received the mandate of the people to govern them.}}</ref> On 6 January 1918, the Draft Decree on the Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly was issued by the Central Executive Committee of the Congress of Soviets, a committee dominated by ], who had previously supported multi-party free elections. After the Bolshevik defeat, Lenin started referring to the assembly as a "deceptive form of bourgeois-democratic parliamentarism".<ref>{{cite journal |last=Dando |first=William A. |date=June 1966 |title=A Map of the Election to the Russian Constituent Assembly of 1917 |journal=Slavic Review |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=314–319 |doi=10.2307/2492782 |issn=0037-6779 |jstor=2492782 |s2cid=156132823 |quote=The political significance of the election to the Russian Constituent Assembly is difficult to as by a large segment of the Russian people ascertain since the Assembly was partly by a large segment of the Russian people as not being really necessary to fulfill their desires in this era of revolutionary development. ... On January 5, 1918, the deputies to the Constituent Assembly met in Petrograd; on January 6 the Central Executive Committee of the Congress of Soviets, dominated by Lenin, issued the Draft Decree on the Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly. The Constituent Assembly, the dream of Russian political reformers for many years, was swept aside as a 'deceptive form of bourgeois-democratic parliamentarism.'}}</ref> This was criticised as being the development of vanguardism as a form of hierarchical party–elite that controlled society.<ref>{{cite book |last=White |first=Elizabeth |year=2010 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tFMuCgAAQBAJ |title=The Socialist Alternative to Bolshevik Russia: The Socialist Revolutionary Party, 1921–39 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-90573-5 |access-date=24 April 2022 |archive-date=21 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220321152046/https://books.google.com/books?id=tFMuCgAAQBAJ |url-status=live |via=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Franks |first=Benjamin |date=May 2012 |title=Between Anarchism and Marxism: The Beginnings and Ends of the Schism |journal=] |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=202–227 |doi=10.1080/13569317.2012.676867 |s2cid=145419232 |issn=1356-9317}}</ref> | |||

| Within five years of the ], ] completed his rise to power and was the ] who theorised and applied the socialist theories of Lenin and ] as political expediencies used to realise his plans for the Soviet Union and for ].<ref name="stalin_follow_marx_lenin">{{cite journal |last=Butenko |first=Alexander |date=1996 |script-title=ru:Социализм сегодня: опыт и новая теория |title=Sotsializm segodnya: opyt i novaya teoriya |language=ru |trans-title=Socialism Today: Experience and New Theory |journal=Журнал Альтернативы |volume=1 |pages=2–22}}</ref> ''Concerning Questions of Leninism'' (1926) represented Marxism–Leninism as a separate communist ideology and featured a global hierarchy of communist parties and revolutionary vanguard parties in each country of the world.<ref>{{cite book |last=Lüthi |first=Lorenz M. |date=2008 |title=The Sino–Soviet Split: Cold War in the Communist World |pages=4 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-13590-8}}</ref>{{r|Lisichkin 1989, p. 59}} With that, Stalin's application of Marxism–Leninism to the situation of the Soviet Union became ], the official ] until his death in 1953.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Butenko |first=Alexander |date=1996 |script-title=ru:Социализм сегодня: опыт и новая теория |title=Sotsializm segodnya: opyt i novaya teoriya |language=ru |trans-title=Socialism Today: Experience and New Theory |journal=Журнал Альтернативы |volume=1 |pages=3–4}}</ref> In Marxist political discourse, Stalinism, denoting and connoting the theory and praxis of Stalin, has two usages, namely praise of Stalin by Marxist–Leninists who believe Stalin successfully developed Lenin's legacy, and criticism of Stalin by Marxist–Leninists and other Marxists who repudiate Stalin's political purges, social-class repressions and bureaucratic terrorism.{{r|Bullock & Trombley 506}} | |||

| ==Ideological characteristics== | |||

| {{Leninism sidebar|expanded=Schools}} | |||

| Originally and for a long time, the concept of a socialist society was regarded as equal to that of a communist society. However, it was Lenin who defined the difference between "socialism" and "communism", explaining that they are similar to what Marx described with the lower and upper stages of communist society. Marx explained that in a society immediately after the revolution distribution must be based on the contribution of the individual, whereas in the upper stage of communism the ] concept would be applied.<ref>The Oxford Companion to Comparative Politics. Joel Krieger, Craig N. Murphy. Oxford University Press, 2012. p. 218.</ref> | |||

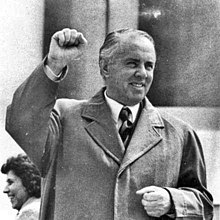

| ] exhorting ] soldiers in the ]]] | |||

| For Marxism–Leninism, the Soviet Union was a workers' state and thus any property under this state was a type of socialist property. However, the rest of Marxist tendencies based their theory of a non-socialist Soviet Union based on disagreement with this, referencing among others the argument of the difference between socialisation and nationalisation. | |||

| As the ] to Stalin within the Soviet party and government, ] and ] argued that Marxist–Leninist ideology contradicted Marxism and Leninism in theory, therefore Stalin's ideology was not useful for the implementation of socialism in Russia. Moreover, Trotskyists within the party identified their anti-Stalinist communist ideology as Bolshevik–Leninism and supported the ] to differentiate themselves from Stalin's justification and implementation of ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Trotsky |first=Leon |author-link=Leon Trotsky |orig-date=1937 |date=1990 |script-title=ru:Сталинская школа фальсификаций |title=Stalinskaya shkola fal'sifikatsiy |language=ru |trans-title=Stalin's school of falsifications |pages=7–8}}</ref> | |||

| ] with ], the American journalist who reported and explained the ] to the West]] | |||

| A key point of conflict between Marxism–Leninism and other tendencies is that whereas Marxism–Leninism defines Stalin's Soviet Union as a ], other types of communists and Marxists in general deny this and Trotskyists specifically consider it a ] or ] workers' state. | |||

| After the ] of the 1960s, the ] and the ] claimed to be the sole heir and successor to Stalin concerning the correct interpretation of Marxism–Leninism and ideological leader of ].<ref name="World History 2000. p. 769">{{cite book |editor1-last=Lenman |editor1-first=Bruce P. |editor2-last=Anderson |editor2-first=T. |date=2000 |title=Chambers Dictionary of World History |pages=769 |publisher=Chambers |isbn=978-0-550-10094-8}}</ref> In that vein, ], ]'s updating and adaptation of Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions in which revolutionary praxis is primary and ideological orthodoxy is secondary, represents urban Marxism–Leninism adapted to pre-industrial China. The claim that Mao had adapted Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions evolved into the idea that he had updated it in a fundamental way applying to the world as a whole. Consequently, Mao Zedong Thought became the official ] of the ] as well as the ideological basis of communist parties around the world which sympathised with China.<ref name="Modern Thought 1999 p. 501">{{cite book |editor1-last=Bullock |editor1-first=Allan |editor1-link=Alan Bullock |editor2-last=Trombley |editor2-first=Stephen |date=1999 |title=The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought |edition=3rd |pages=501 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-00-686383-0}}</ref> In the late 1970s, the Peruvian communist party ] developed and synthesised Mao Zedong Thought into ], a contemporary variety of Marxism–Leninism that is a supposed higher level of Marxism–Leninism that can be applied universally.{{r|Modern Thought 1999 p. 501}} | |||

| ], who led the ] in the 1970s and whose ] followers led to the development of ]]] | |||

| ==Components== | |||

| Following the ] of the 1970s, a small portion of Marxist–Leninists began to downplay or repudiate the role of Mao in the Marxist–Leninist international movement in favour of the ] and stricter adherence to Stalin. The Sino-Albanian split was caused by ]'s rejection of China's {{lang|de|]}} of Sino–American rapprochement, specifically the ] which the ] Albanian Labour Party perceived as an ideological betrayal of Mao's own ] that excluded such political rapprochement with the West. To the Albanian Marxist–Leninists, the Chinese dealings with the United States indicated Mao's lessened, practical commitments to ideological orthodoxy and ]. In response to Mao's apparently unorthodox deviations, ], head of the Albanian Labour Party, theorised anti-revisionist Marxism–Leninism, referred to as ], which retained orthodox Marxism–Leninism when compared to the ideology of the post-Stalin Soviet Union.{{r|Bland}} | |||

| ===Social=== | |||

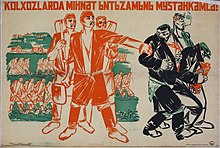

| Marxism–Leninism supports universal ].<ref>Pons, pp. 722–723.</ref> Improvements in public health and education, provision of child care, provision of state-directed social services and provision of social benefits are deemed by Marxist–Leninists to help to raise labour productivity and advance a society in development towards a communist society.<ref name="Pons p. 721">Pons, p. 721.</ref> This is part of Marxist–Leninists' advocacy of promoting and reinforcing the operation of a ].<ref name="Pons p. 721"/> It advocates universal education with a focus on developing the proletariat with knowledge, class consciousness, and understanding the ] of communism.<ref>Pons, p. 580.</ref> | |||

| In ], Marxism–Leninism was superseded by '']'' in the 1970s. This was made official in 1992 and 2009, when constitutional references to Marxism–Leninism were dropped and replaced with ''Juche''.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Dae-Kyu |first=Yoon |year=2003 |url=http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1934&context=ilj |title=The Constitution of North Korea: Its Changes and Implications |journal=Fordham International Law Journal |volume=27 |issue=4 |pages=1289–1305 |access-date=10 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210224144030/https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1934&context=ilj |archive-date=24 February 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> In 2009, the constitution was quietly amended so that not only did it remove all Marxist–Leninist references present in the first draft but also dropped all references to ].<ref>{{cite news |last=Park |first=Seong-Woo |date=23 September 2009 |url=https://www.rfa.org/korean/in_focus/first_millitary-09232009120017.html |script-title=ko:북 개정 헌법 '선군사상' 첫 명기 |title=Bug gaejeong heonbeob 'seongunsasang' cheos myeong-gi |trans-title=First stipulation of the 'Seongun Thought' of the North Korean Constitution |agency=Radio Free Asia |language=ko |access-date=10 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210517045408/https://www.rfa.org/korean/in_focus/first_millitary-09232009120017.html |archive-date=17 May 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> ''Juche'' has been described by Michael Seth as a version of ],<ref>{{cite book |last=Seth |first=Michael J. |year=2019 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GPm9DwAAQBAJ&q=%22juche%22+%22ultranationalism%22&pg=PA159 |title=A Concise History of Modern Korea: From the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present |publisher=] |page=159 |isbn=978-1-5381-2905-0 |access-date=11 September 2020 |archive-date=6 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210206043439/https://books.google.com/books?id=GPm9DwAAQBAJ&q=%22juche%22+%22ultranationalism%22&pg=PA159 |url-status=live |via=]}}</ref> which eventually developed after losing its original Marxist–Leninist elements.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Fisher |first1=Max |date=6 January 2016 |url=https://www.vox.com/2016/1/6/10724334/north-korea-history |title=The single most important fact for understanding North Korea |website=Vox |access-date=11 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210306090942/https://www.vox.com/2016/1/6/10724334/north-korea-history |archive-date=6 March 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> According to ''North Korea: A Country Study'' by Robert L. Worden, Marxism–Leninism was abandoned immediately after the start of ] in the Soviet Union and has been totally replaced by ''Juche'' since at least 1974.<ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Worden |editor-first=Robert L. |year=2008 |url=http://cdn.loc.gov/master/frd/frdcstdy/no/northkoreacountr00word/northkoreacountr00word.pdf |title=North Korea: A Country Study |edition=5th |location=Washington, D. C. |publisher=] |page=206 |isbn=978-0-8444-1188-0 |access-date=11 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210725073828/https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/frd/frdcstdy/no/northkoreacountr00word/northkoreacountr00word.pdf |archive-date=25 July 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> Daniel Schwekendiek wrote that what made North Korean Marxism–Leninism distinct from that of China and the Soviet Union was that it incorporated national feelings and macro-historical elements in the socialist ideology, opting for its "own style of socialism".<ref name="Schwekendiek">{{cite book |last=Schwekendiek |first=Daniel |date=2011 |title=A Socioeconomic History of North Korea |location=Jefferson |publisher=] |pages=31 |isbn=978-0-7864-6344-2}}</ref> The major Korean elements are the emphasis on traditional ] and the memory of the traumatic experience of ] as well as a focus on autobiographical features of ] as a guerrilla hero.{{r|Schwekendiek}} | |||

| Marxist–Leninist policy on family law has typically involved: the elimination of the political power of the bourgeoisie, the abolition of private property and an education that teaches citizens to abide by a disciplined and self-fulfilling lifestyle dictated by the social norms of communism as a means to establish a new social order.<ref name="Pons p. 319">Pons, p. 319.</ref> | |||

| In the other four existing Marxist–Leninist ]s, namely China, ], ], and ], the ruling parties hold Marxism–Leninism as their official ideology, although they give it different interpretations in terms of practical policy. Marxism–Leninism is also the ideology of anti-revisionist, Hoxhaist, Maoist, and ] communist parties worldwide. The anti-revisionists criticise some rule of the communist states by claiming that they were ] countries ruled by '']''.<ref>{{cite magazine|last=Bland |first=Bill |date=1995 |orig-date=1980 |url=https://revolutionarydemocracy.org/archive/BlandRestoration.pdf |title=The Restoration of Capitalism in the Soviet Union |magazine=Revolutionary Democracy Journal |access-date=16 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210810124332/http://www.revolutionarydemocracy.org/archive/BlandRestoration.pdf |archive-date=10 August 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Mao |last=Zedong |author-link=Mao Zedong |translator-first=Moss |translator-last=Roberts |date=1977 |url=http://www.marx2mao.com/Mao/CSE58.html |title=A Critique of Soviet Economics |location=New York City, New York |publisher=Monthly Review Press |access-date=16 February 2020 |archive-date=3 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303192812/http://www.marx2mao.com/Mao/CSE58.html |url-status=live}}</ref> Although the periods and countries vary among different ideologies and parties, they generally accept that the Soviet Union was socialist during Stalin's time, Maoists believe that China became state capitalist after Mao's death, and Hoxhaists believe that China was always state capitalist, and uphold the Albania as the only socialist state after the Soviet Union under Stalin.<ref name="Bland">{{cite book |last=Bland |first=Bill |date=1997 |url=http://ml-review.ca/aml/China/historymaotable.html |title=Class Struggles in China |edition=revised |location=London |access-date=16 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211017084651/http://ml-review.ca/aml/China/historymaotable.html |archive-date=17 October 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Marxism–Leninism supports the ] and ending the exploitation of women.<ref>Pons, pp. 854–856.</ref> The advent of a classless society, the abolition of private property, society collectively assuming many of the roles traditionally assigned to mothers and wives and women becoming integrated into industrial work has been promoted as the means to achieve women's emancipation.<ref>Pons, p. 854.</ref> | |||

| === Definition, theory, and terminology === | |||

| Marxist–Leninist cultural policy focuses upon modernisation and distancing society from: the past, the bourgeoisie and the old intelligentsia.<ref>Pons, p. 250.</ref> ] and various associations and institutions are used by the Marxist–Leninist state to educate society with the values of communism.<ref name="Pons pp. 250-251">Pons, pp. 250–251.</ref> Both cultural and educational policy in Marxist–Leninist states have emphasised the development of a "]"—a class conscious, knowledgeable, heroic proletarian person devoted to work and ] as opposed to the antithetic "bourgeois individualist" associated with ] and social atomisation.<ref name="Pons p. 581">Pons, p. 581.</ref> | |||

| ] in 1875]] | |||

| ] and ideas have acquired a new meaning since the ],<ref name="Wright 2015, p. 3355">{{cite encyclopedia |editor-last=Wright |editor-first=James D. |editor-link=James D. Wright |encyclopedia=] |publisher=] |year=2015 |isbn=978-0-08-097087-5 |location=Oxford |edition=2nd |page=3355 |doi=}}{{full citation needed|date=July 2024}}</ref> as they became equivalent to the ideas of Marxism–Leninism,{{r|Busky 2000, pp. 6–8}} namely the interpretation of ] by ] and his successors.{{sfn|Cooke|1998|pp=221–222}}{{r|Wright 2015, p. 3355}} Endorsing the final objective, namely the creation of a community-owning ] and providing each of its participants with consumption "]", Marxism–Leninism puts forward the recognition of the ] as a dominating principle of a ] and development.{{r|Wright 2015, p. 3355}} In addition, workers (the ]) were to carry out the mission of reconstruction of the society.{{r|Wright 2015, p. 3355}} Conducting a ] led by what its proponents termed the "]", defined as the ] organised hierarchically through ], was hailed to be a historical necessity by Marxist–Leninists.{{sfn|Albert|Hahnel|1981|pp=24–26}}{{r|Wright 2015, p. 3355}} Moreover, the introduction of the ] was advocated and classes deemed hostile were to be repressed.{{r|Wright 2015, p. 3355}} In the 1920s, it was first defined and formulated by ] based on his understanding of ] and ].{{r|Lansford 2007, p. 17}} | |||

| In 1934, ] suggested the formulation ''Marxism–Leninism–Stalinism'' in an article in '']'' to stress the importance of Stalin's leadership to the Marxist–Leninist ideology. Radek's suggestion failed to catch on, as Stalin as well as CPSU's ideologists preferred to continue the usage of ''Marxism–Leninism''.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ilyin |first=Mikhail |title=International Encyclopedia of Political Science |publisher=Sage Publications |year=2011 |isbn=978-1-4129-5963-6 |editor-last=Badie |editor-first=Bertrand |pages=2481–2485 |chapter=Stalinism |display-editors=et al.}}</ref> ''Marxism–Leninism–Maoism'' became the name for the ideology of the ] and of other ], which broke off from national Communist parties, after the ], especially when the split was finalised by 1963. The ] was mainly influenced by ], who gave a more democratic implication than Lenin's for why workers remained passive.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Morgan |first=W. John |year=2001 |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/referencework/9780080430768/international-encyclopedia-of-the-social-and-behavioral-sciences |title=Marxism–Leninism: The Ideology of Twentieth-Century Communism |editor1-last=Baltes |editor1-first=Paul B. |editor1-link=Neil Smelser |editor2-last=Smelser |editor2-first=Neil J. |editor2-link=Paul Baltes |encyclopedia=] |volume=20 |edition=1st |publisher=] |page=2332 |isbn=978-0-08-043076-8 |access-date=25 August 2021 |via=Science Direct |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211031003018/https://www.sciencedirect.com/referencework/9780080430768/international-encyclopedia-of-the-social-and-behavioral-sciences |archive-date=31 October 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> A key difference between ] and other forms of Marxism–Leninism is that ]s should be the bulwark of the revolutionary energy, which is led by the working class.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Meisner |first=Maurice |date=January–March 1971 |title=Leninism and Maoism: Some Populist Perspectives on Marxism-Leninism in China |journal=The China Quarterly |volume=45 |issue=45 |pages=2–36 |doi=10.1017/S0305741000010407 |jstor=651881 |s2cid=154407265}}</ref> Three common Maoist values are revolutionary ], pragmatism, and ]s.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Wormack |first=Brantly |year=2001 |title=Maoism |editor1-last=Baltes |editor1-first=Paul B. |editor1-link=Paul Baltes |editor2-last=Smelser |editor2-first=Neil J. |editor2-link=Neil Smelser |encyclopedia=] |volume=20 |pages=9191–9193 |edition=1st |publisher=] |doi=10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01173-6 |isbn=978-0-08-043076-8}}</ref> | |||

| ===Economic=== | |||

| The state serves as a safeguard for the ownership and as the coordinator of production through a universal ].<ref name="Pons p. 138">Pons, p. 138.</ref> For the purpose of reducing waste and increasing efficiency, scientific planning replaces ]s and price mechanisms as the guiding principle of the economy.<ref name="Pons p. 138"/> The Marxist–Leninist state's huge purchasing power replaces the role of market forces, with ] ] not being achieved through market forces, but by economic planning based on scientific ].<ref name="Pons p. 139">Pons, p. 139.</ref> In the socialist economy, the value of a good or service is based on its ] rather than its ] or its ]. The ] as a driving force for production is replaced by social obligation to fulfil the economic plan.<ref name="Pons p. 139"/> ]s are set and differentiated according to skill and intensity of work.<ref name="Pons p. 140"/> While socially utilised means of production are under public control, personal belongings or property of a personal nature that doesn't involve mass production of goods remains relatively unaffected by the state.<ref name="Pons p. 140">Pons, p. 140.</ref> | |||

| According to Rachel Walker, "Marxism–Leninism" is an empty term that depends on the approach and basis of ruling Communist parties, and is dynamic and open to redefinition, being both fixed and not fixed in meaning.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Walker |first=Rachel |date=April 1989 |title=Marxism–Leninism as Discourse: The Politics of the Empty Signifier and the Double Bind |journal=British Journal of Political Science |publisher=] |volume=19 |issue=2 |pages=161–189 |doi=10.1017/S0007123400005421 |jstor=193712 |s2cid=145755330}}</ref> As a term, "Marxism–Leninism" is misleading because Marx and Lenin never sanctioned or supported the creation of an ''-ism'' after them, and is reveling because, being popularized after Lenin's death by Stalin, it contained three clear doctrinal and institutionalized principles that became a model for later Soviet-type regimes; its global influence, having at its height covered at least one-third of the world's population, has made Marxist–Leninist a convenient label for the ] as a dynamic ideological order.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Morgan |first=W. John |year=2001 |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/referencework/9780080430768/international-encyclopedia-of-the-social-and-behavioral-sciences |title=Marxism–Leninism: The Ideology of Twentieth-Century Communism |editor1-last=Baltes |editor1-first=Paul B. |editor1-link=Paul Baltes |editor2-last=Smelser |editor2-first=Neil J. |editor2-link=Neil Smelser |encyclopedia=] |volume=20 |edition=1st |publisher=] |pages=2332, 3355 |isbn=978-0-08-043076-8 |access-date=25 August 2021 |via=Science Direct |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211031003018/https://www.sciencedirect.com/referencework/9780080430768/international-encyclopedia-of-the-social-and-behavioral-sciences |archive-date=31 October 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref>{{sfn|Morgan|2015|p={{page needed|date=April 2022}}}} | |||

| Because Marxism–Leninism has historically only been the state ideology of countries who were economically undeveloped prior to ] (or whose economies were nearly obliterated by war, such as the ]), the primary goal before achieving full communism was the development of socialism in itself. Such was the case in the Soviet Union, where the economy was largely agrarian and urban industry was in a primitive stage. To develop socialism, the economy went through a ] in which much of the peasant population moved into urban areas while those remaining in the rural areas began working in the new ]. Since the mid-1930s, Marxism–Leninism has advocated a socialist consumer society based upon ], ] and ].<ref name="Pons p. 731">Pons, p. 731.</ref> Previous attempts to replace the consumer society as derived from capitalism with a non-consumerist society failed and in the mid-1930s permitted a consumer society, a major change from traditional Marxism's anti-market and anti-consumerist theories.<ref name="Pons p. 731"/> These reforms were promoted to encourage materialism and acquisitiveness in order to stimulate economic growth.<ref name="Pons p. 731"/> This pro-consumerist policy has been advanced on the lines of "industrial pragmatism" as it advances economic progress through bolstering industrialisation.<ref>Pons, p. 732.</ref> | |||

| === Historiography === | |||

| The ultimate goal of the Marxist–Leninist economy is the emancipation of the individual from ] work and therefore freedom from having to perform such labour to receive access to the material necessities for life. It is argued that freedom from necessity would maximise individual liberty as individuals would be able to pursue their own interests and develop their own talents while only performing labour by free will without external coercion. The stage of economic development in which this is possible is contingent upon advances in the productive capabilities of society. This advanced stage of social relations and economic organisation is called ]. | |||

| Historiography of ]s is polarised. According to ] and ], historiography is characterised by a split between traditionalists and revisionists.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Haynes |first1=John Earl |author1-link=John Earl Haynes |last2=Klehr |first2=Harvey |author2-link=Harvey Klehr |date=2003 |chapter=Revising History |title=In Denial: Historians, Communism and Espionage |location=San Francisco |publisher=Encounter |pages=11–57 |isbn=1-893554-72-4}}</ref> "Traditionalists", who characterise themselves as objective reporters of an alleged ] nature of ] and Marxist–Leninist states, are criticised by their opponents as being ], even '']'', in their eagerness on continuing to focus on the issues of the ]. Alternative characterisations for traditionalists include "anti-communist", "conservative", "Draperite" (after ]), "orthodox", and "right-wing"; Norman Markowitz, a prominent "revisionist", referred to them as "reactionaries", "right-wing romantics", "romantics", and "triumphalist" who belong to the "] school of ] scholarship".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Haynes |first1=John Earl |author1-link=John Earl Haynes |last2=Klehr |first2=Harvey |author2-link=Harvey Klehr |date=2003 |chapter=Revising History |title=In Denial: Historians, Communism and Espionage |location=San Francisco |publisher=Encounter |pages=43 |isbn=1-893554-72-4}}</ref> According to Haynes and Klehr, "revisionists" are more numerous and dominate academic institutions and learned journals. A suggested alternative formulation is "new historians of American communism", but that has not caught on because these historians describe themselves as unbiased and scholarly and contrast their work to the work of anti-communist traditionalists whom they would term biased and unscholarly.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Haynes |first1=John Earl |author-link1=John Earl Haynes |last2=Klehr |first2=Harvey |author-link2=Harvey Klehr |date=2003 |chapter=Revising History |title=In Denial: Historians, Communism and Espionage |location=San Francisco |publisher=Encounter |pages=43–44 |isbn=1-893554-72-4}}</ref> Academic ] after ] and during the Cold War was dominated by the "totalitarian model" of the Soviet Union,<ref>{{cite book |first1=Sarah |last1=Davies |author1-link=Sarah Davies (historian) |first2=James |last2=Harris |title=Stalin: A New History |chapter=Joseph Stalin: Power and Ideas |date=8 September 2005 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-139-44663-1 |page=3 |quote=Academic Sovietology, a child of the early Cold War, was dominated by the 'totalitarian model' of Soviet politics. Until the 1960s it was almost impossible to advance any other interpretation, in the USA at least.}}</ref> stressing the absolute nature of Stalin's power.<ref>{{cite book |first1=Sarah |last1=Davies |author1-link=Sarah Davies (historian) |first2=James |last2=Harris |title=Stalin: A New History |chapter=Joseph Stalin: Power and Ideas |date=8 September 2005 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-139-44663-1 |pages=3–4 |quote=In 1953, Carl Friedrich characterised totalitarian systems in terms of five points: an official ideology, control of weapons and of media, use of terror, and a single mass party, 'usually under a single leader'. There was of course an assumption that the leader was critical to the workings of totalitarianism: at the apex of a monolithic, centralised, and hierarchical system, it was he who issued the orders which were fulfilled unquestioningly by his subordinates.}}</ref> The "revisionist school" beginning in the 1960s focused on relatively autonomous institutions which might influence policy at the higher level.<ref name="DaviesHarris2005">{{cite book |first1=Sarah |last1=Davies |author1-link=Sarah Davies (historian) |first2=James |last2=Harris |title=Stalin: A New History |chapter=Joseph Stalin: Power and Ideas |date=8 September 2005 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-139-44663-1 |pages=4–5 |quote=Tucker's work stressed the absolute nature of Stalin's power, an assumption which was increasingly challenged by later revisionist historians. In his ''Origins of the Great Purges'', Arch Getty argued that the Soviet political system was chaotic, that institutions often escaped the control of the centre, and that Stalin’s leadership consisted to a considerable extent in responding, on an ad hoc basis, to political crises as they arose. Getty's work was influenced by political science of the 1960s onwards, which, in a critique of the totalitarian model, began to consider the possibility that relatively autonomous bureaucratic institutions might have had some influence on policy-making at the highest level.}}</ref> Matt Lenoe described the "revisionist school" as representing those who "insisted that the old image of the Soviet Union as a totalitarian state bent on world domination was oversimplified or just plain wrong. They tended to be interested in social history and to argue that the Communist Party leadership had had to adjust to social forces."<ref name="Lenoe2002">{{cite journal |last1=Lenoe |first1=Matt |title=Did Stalin Kill Kirov and Does It Matter? |journal=The Journal of Modern History |volume=74 |issue=2 |year=2002 |pages=352–380 |issn=0022-2801 |doi=10.1086/343411 |s2cid=142829949}}</ref> These "revisionist school" historians challenged the "totalitarian model", as outlined by political scientist ], which stated that the Soviet Union and other Marxist–Leninist states were totalitarian systems, with the personality cult, and almost unlimited powers of the "great leader", such as Stalin.{{r|DaviesHarris2005}}<ref name="Fitzpatrick">{{cite journal |first1=Sheila |last1=Fitzpatrick |author-link1=Sheila Fitzpatrick |title=Revisionism in Soviet History |journal=History and Theory |volume=46 |issue=4 |year=2007 |pages=77–91 |issn=1468-2303 |doi=10.1111/j.1468-2303.2007.00429.x |quote=... the Western scholars who in the 1990s and 2000s were most active in scouring the new archives for data on Soviet repression were revisionists (always 'archive rats') such as Arch Getty and Lynne Viola.}}</ref> It was considered to be outdated by the 1980s and for the post-Stalinist era.<ref name="Zimmerman 1980">{{cite journal |last=Zimmerman |first=William |date=September 1980 |title=Review: How the Soviet Union is Governed |publisher=] |journal=] |volume=39 |issue=3 |pages=482–486 |doi=10.2307/2497167 |jstor=2497167 |quote=In the intervening quarter-century, the Soviet Union has changed substantially. Our knowledge of the Soviet Union has changed as well. We all know that the traditional paradigm no longer satisfies, despite several efforts, primarily in the early 1960s (the directed society, totalitarianism without terror, the mobilization system) to articulate an acceptable variant. We have come to realize that models which were, in effect, offshoots of totalitarian models do not provide good approximations of post-Stalinist reality. |postscript=. Quote at p. 482}}</ref> | |||

| ], one of the authors of '']'']] | |||

| ===Political system=== | |||

| Some academics, such as ] ('']''), ] ('']''), and ] ('']''), wrote of mass, excess deaths under Marxist–Leninist regimes. These authors defined the political repression by communists as a "]", "Communist genocide", "Red Holocaust", or followed the "victims of Communism" narrative. Some of them compared Communism to ] and described deaths under Marxist–Leninist regimes (civil wars, deportations, famines, repressions, and wars) as being a direct consequence of Marxism–Leninism. Some of these works, in particular ''The Black Book of Communism'' and its 93 or 100 millions figure, are cited by ] and ].{{r|Ghodsee 2014}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Neumayer |first=Laure |author-link=Laure Neumayer |year=2018 |title=The Criminalisation of Communism in the European Political Space after the Cold War |location=London |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-351-14174-1}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Neumayer |first=Laure |author-link=Laure Neumayer |date=November 2018 |title=Advocating for the Cause of the 'Victims of Communism' in the European Political Space: Memory Entrepreneurs in Interstitial Fields |journal=] |volume=45 |number=6 |pages=992–1012 |doi=10.1080/00905992.2017.1364230 |s2cid=158275798 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Without denying the tragedy of the events, other scholars criticise the interpretation that sees communism as the main culprit as presenting a biased or exaggerated anti-communist narrative. Several academics propose a more nuanced analysis of Marxist–Leninist rule, stating that anti-communist narratives have exaggerated the extent of political repression and censorship in Marxist–Leninist states and drawn comparisons with what they see as atrocities that were perpetrated by ], particularly during the Cold War. These academics include ],<ref>{{cite book |last=Aarons |first=Mark |author-link=Mark Aarons |date=2007 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dg0hWswKgTIC&pg=PA69 |chapter=Justice Betrayed: Post-1945 Responses to Genocide |editor1-last=Blumenthal |editor1-first=David A. |editor2-last=McCormack |editor2-first=Timothy L. H. |url=http://www.brill.com/legacy-nuremberg-civilising-influence-or-institutionalised-vengeance |title=The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law) |publisher=] |pages=, |isbn=978-90-04-15691-3 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525090909/https://brill.com/legacy-nuremberg-civilising-influence-or-institutionalised-vengeance |archive-date=25 May 2017 |url-status=dead |via=]}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web|last=Chomsky |first=Noam |author-link=Noam Chomsky |title=Counting the Bodies |work=Spectrezine |access-date=18 September 2016 |url=http://spectrezine.org/global/chomsky.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160921084037/http://www.spectrezine.org/global/chomsky.htm |archive-date=21 September 2016}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite book |last=Dean |first=Jodi |author-link=Jodi Dean |date=2012 |title=The Communist Horizon |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kBghOq42S3YC&pg=PA6 |publisher=Verso |pages=6–7 |isbn=978-1-84467-954-6 |access-date=3 December 2020 |archive-date=17 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211017084656/https://books.google.com/books?id=kBghOq42S3YC&pg=PA6 |url-status=live |via=]}}</ref> ],<ref name="Ghodsee 2014">{{cite journal |last=Ghodsee |first=Kristen |author-link=Kristen Ghodsee |date=Fall 2014 |url=https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/kristenghodsee/files/history_of_the_present_galleys.pdf |title=A Tale of 'Two Totalitarianisms': The Crisis of Capitalism and the Historical Memory of Communism |journal=History of the Present: A Journal of Critical History |volume=4 |number=2 |pages=115–142 |doi=10.5406/historypresent.4.2.0115 |jstor=10.5406/historypresent.4.2.0115 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211031180121/https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/kristenghodsee/files/history_of_the_present_galleys.pdf |archive-date=31 October 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Ghodsee & Sehon 2018">{{cite magazine|last1=Ghodsee |first1=Kristen R. |author-link1=Kristen Ghodsee |last2=Sehon |first2=Scott |author-link2=Scott Sehon |editor-last=Dresser |editor-first=Sam |date=22 March 2018 |url=https://aeon.co/essays/the-merits-of-taking-an-anti-anti-communism-stance |title=The merits of taking an anti-anti-communism stance |magazine=] |access-date=11 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211008113511/https://aeon.co/essays/the-merits-of-taking-an-anti-anti-communism-stance |archive-date=8 October 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> ],{{r|Milne 2002}}{{r|Milne 2006}} and ].{{sfn|Parenti|1997}} Ghodsee, ],<ref>{{cite news |last=Robinson |first=Nathan J. |author-link=Nathan J. Robinson |date=25 October 2017 |url=https://www.currentaffairs.org/news/2017/10/how-to-be-a-socialist-without-being-an-apologist-for-the-atrocities-of-communist-regimes |title=How To Be A Socialist Without Being An Apologist For The Atrocities Of Communist Regimes |work=] |access-date=13 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211020044217/https://www.currentaffairs.org/2017/10/how-to-be-a-socialist-without-being-an-apologist-for-the-atrocities-of-communist-regimes |archive-date=20 October 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> and ] wrote about the merits of taking an ] position that does not deny the atrocities but make a distinction between ] communist and other socialist currents, both of which have been victims of repression.{{r|Ghodsee & Sehon 2018}}<ref>{{cite news |last=Klein |first=Ezra |author-link=Ezra Klein |date=7 January 2020 |url=https://www.vox.com/podcasts/2020/1/7/21055676/nathan-robinson-ezra-klein-socialism-bernie-sanders |title=Nathan Robinson's case for socialism |website=] |access-date=13 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210813101444/https://www.vox.com/podcasts/2020/1/7/21055676/nathan-robinson-ezra-klein-socialism-bernie-sanders |archive-date=13 August 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Marxism–Leninism supports the creation of a ] led by a Marxist–Leninist communist party as a means to develop socialism and then communism.<ref name="Alexander Shtromas 2003. p. 18">Alexander Shtromas, Robert K. Faulkner, Daniel J. Mahoney. ''Totalitarianism and the Prospects for World Order: Closing the Door on the Twentieth Century''. Oxford, England, UK; Lanham, Maryland, USA: Lexington Books, 2003. p. 18.</ref> The political structure of the Marxist–Leninist state involves the rule of a communist ] over a ] ] state that represents the will and rule of the ].<ref name="Albert pp. 24-25">Michael Albert, Robin Hahnel. Socialism today and tomorrow. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: South End Press, 1981. pp. 24–25.</ref> Through the policy of ], the ] is the supreme political institution of the Marxist–Leninist state. | |||

| == History == | |||

| Elections are held in Marxist–Leninist states for all positions within the legislative structure, municipal councils, national legislatures and presidencies.<ref name="Pons p. 306">Pons, p. 306.</ref> In most Marxist–Leninist states, this has taken the form of directly electing representatives to fill positions, though in some states such as China, Cuba and the former Yugoslavia this system also included indirect elections such as deputies being elected by deputies as the next lower level of government.<ref name="Pons p. 306"/> These elections are not competitive multi-party elections and most are not multi-candidate elections; usually a single communist party candidate is chosen to run for office in which voters vote either to accept or reject the candidate.<ref name="Pons p. 306"/> Where there have been more than one candidates, all candidates are officially vetted before being able to stand for candidacy and the system has frequently been structured to give advantage to official candidates over others.<ref name="Pons p. 306"/> Marxism–Leninism asserts that society is united upon common interests represented through the communist party and other institutions of the Marxist–Leninist state and in Marxist–Leninist states where opposition political parties have been permitted they have not been permitted to advocate political platforms significantly different from the communist party.<ref name="Pons p. 306"/> Marxist–Leninist communist parties have typically exercised close control over the electoral process of such elections, including involvement with nomination, campaigning and voting—including counting the ballots.<ref name="Pons p. 306"/> | |||

| === Bolsheviks, February Revolution, and Great War (1903–1917) === | |||

| {{Further|Bolsheviks|Leninism}} | |||

| ], who led the Bolshevik faction within the ]]] | |||

| Although Marxism–Leninism was created after ]'s death by ] in the Soviet Union, continuing to be the official state ideology after de-Stalinisation and of other Marxist–Leninist states, the basis for elements of Marxism–Leninism predate this. The philosophy of Marxism–Leninism originated as the pro-active, political praxis of the ] faction of the ] in realising political change in Tsarist Russia.{{sfn|Bottomore|1991|p=53–54}} Lenin's leadership transformed the Bolsheviks into the party's political vanguard which was composed of professional revolutionaries who practised ] to elect leaders and officers as well as to determine policy through free discussion, then decisively realised through united action.<ref name=freedomunity>{{cite web|last=Lenin |first=Vladimir |author-link=Vladimir Lenin |year=1906 |url=http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1906/rucong/viii.htm |title=Report on the Unity Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. |access-date=9 August 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080919195901/http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1906/rucong/viii.htm |archive-date=19 September 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> The ] of proactive, pragmatic commitment to achieving revolution was the Bolsheviks' advantage in out-manoeuvring the liberal and conservative political parties who advocated ] without a practical plan of action for the Russian society they wished to govern. ] allowed the ] to assume command of the ] in 1917.{{sfn|Bottomore|1991|p=54}} | |||

| ] addressing the two chambers of the ] at the Winter Palace after the failed ] which exiled Lenin from ] to Switzerland ]] | |||

| ===International relations=== | |||

| Twelve years before the October Revolution in 1917, the Bolsheviks had failed to assume control of the February Revolution of 1905 (22 January 1905 – 16 June 1907) because the centres of revolutionary action were too far apart for proper political coordination.{{sfn|Bottomore|1991|p=259}} To generate revolutionary momentum from the Tsarist army killings on ] (22 January 1905), the Bolsheviks encouraged workers to use political violence in order to compel the bourgeois social classes (the nobility, the gentry and the bourgeoisie) to join the ] to overthrow the ] of the ].{{sfn|Ulam|1998|p=204}} Most importantly, the experience of this revolution caused Lenin to conceive of the means of sponsoring socialist revolution through agitation, propaganda and a well-organised, disciplined and small political party.{{sfn|Ulam|1998|p=207}} | |||

| Marxism–Leninism aims to create an international communist society.<ref name="Albert pp. 24-25"/> It opposes ] and ] and advocates ] and anti-colonial forces.<ref name="Pons p. 258">Pons, p. 258.</ref> It supports ] international alliances and has advocated the creation of "]s" between communist and non-communist anti-fascists against strong fascist movements.<ref>Pons, p. 326.</ref> | |||

| Despite secret-police persecution by the ] (Department for Protecting the Public Security and Order), émigré Bolsheviks returned to Russia to agitate, organise and lead, but then they returned to exile when peoples' revolutionary fervour failed in 1907.{{sfn|Ulam|1998|p=207}} The failure of the February Revolution exiled Bolsheviks, ], ] and anarchists such as the ] from Russia.{{sfn|Ulam|1998|p=269}} Membership in both the Bolshevik and Menshevik ranks diminished from 1907 to 1908 while the number of people taking part in strikes in 1907 was 26% of the figure during the year of the Revolution of 1905, dropping to 6% in 1908 and 2% in 1910.{{sfn|Ulam|1998|p=270}} The 1908–1917 period was one of disillusionment in the Bolshevik party over Lenin's leadership, with members opposing him for scandals involving his expropriations and methods of raising money for the party.{{sfn|Ulam|1998|p=270}} This political defeat was aggravated by ]'s political reformations of Imperial Russian government. In practise, the formalities of political participation (the electoral plurality of a ] with the ] and the ]) were the Tsar's piecemeal and cosmetic concessions to ] because public office remained available only to the ], the ] and the ]. These reforms resolved neither the ], the ], nor ] of the proletarian majority of Imperial Russia.{{sfn|Ulam|1998|p=269}} | |||

| ===Theological=== | |||

| ], was demolished in the 1930s in accordance with ]]] | |||

| The Marxist–Leninist world view promotes ] as a fundamental tenet.<ref>''Marxism–Leninism as the Civil Religion of Soviet Society'', by James Thrower. E. Mellen Press, 1992. Page 45.</ref><ref>''Ideology And Political System'', by Kundan Kumar. Discovery Publishing House, 2003. Page 90.</ref> ] has its roots in the philosophy of ], ], as well as Marx and Lenin.<ref>''Slovak Studies'', Volume 21. The Slovak Institute in North America. p. 231. "The origin of Marxist–Leninist atheism as understood in the USSR, is linked with the development of the German philosophy of Hegel and Feuerbach."</ref> ], the philosophical standpoint that the universe exists independently of human consciousness, consisting of only atoms and physical forces, is central to the world view of Marxism–Leninism in the form of ]. ], a Soviet physicist, wrote that the "] communists were not merely atheists, but, according to Lenin's terminology, ]s".<ref>''On Superconductivity and Superfluidity: A Scientific Autobiography'', by Vitalij Lazarʹevič Ginzburg. Springer, 2009. Page 45.</ref> Therefore many Marxist–Leninist states, both historically and currently, are also ].<ref>''The A to Z of Marxism'', by David Walker & Daniel Gray. Rowman & Littlefield, 2009. Page 6.</ref> Under these regimes, several religions and their adherents were targeted to be "stamped out".<ref>''The Soviet Campaign Against Islam in Central Asia, 1917–1941'', by Shoshana Keller. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. Page 251.</ref> | |||

| In Swiss exile, Lenin developed Marx's philosophy and extrapolated ] by ] as a reinforcement of ] in Europe.{{sfn|Bottomore|1991|p=98}} In 1912, Lenin resolved a factional challenge to his ideological leadership of the RSDLP by the Forward Group in the party, usurping the all-party congress to transform the RSDLP into the Bolshevik party.{{sfn|Ulam|1998|pp=282–284}} In the early 1910s, Lenin remained highly unpopular and was so unpopular amongst international socialist movement that by 1914 it considered censoring him.{{sfn|Ulam|1998|p=270}} Unlike the European socialists who chose bellicose nationalism to anti-war internationalism, whose philosophical and political break was consequence of the ] among socialists, the Bolsheviks opposed the ] (1914–1918).<ref name="university1995">{{cite book |last=Anderson |first=Kevin |author-link=Kevin B. Anderson |date=199 |title=Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism: A Critical Study |location=Chicago |publisher=] |pages=3 |isbn=978-90-04-47161-0}}</ref> That nationalist betrayal of socialism was denounced by a small group of socialist leaders who opposed the Great War, including ], ] and Lenin, who said that the European socialists had failed the working classes for preferring patriotic war to ].{{r|university1995}} To debunk ] and national ], Lenin explained in the essay '']'' (1917) that capitalist economic expansion leads to ] which is then regulated with nationalist wars such as the Great War among the empires of Europe.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Evans |editor1-first=Graham |editor2-last=Newnham |editor2-first=Jeffrey |date=1998 |title=Penguin Dictionary of International Relations |publisher=Penguin Random House |pages=317 |isbn=978-0-14-051397-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Cavanagh Hodge |editor-first=Carl |date=2008 |title=Encyclopedia of the Age of Imperialism, 1800–1914 |volume=2 |location=Westport |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |pages=415 |isbn=978-0-313-33404-7}}</ref> To relieve strategic pressures from the ] (4 August 1914 – 11 November 1918), ] impelled the withdrawal of ] from the war's ] (17 August 1914 – 3 March 1918) by sending Lenin and his Bolshevik cohort in a diplomatically sealed train, anticipating them partaking in revolutionary activity.<ref>{{cite book |last=Beckett |first=Ian Frederick William |date=2009 |title=1917: Beyond the Western Front |location=Leiden |publisher=] |pages=1 |isbn=978-90-474-2470-3}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ===Founding of Bolshevism, 1905–1907 Russian Revolution and World War I (1903–1917)=== | |||

| Marxism–Leninism was created after Lenin's death during the regime of Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union, but continued to be the official ideology of the ] after ]. However, the basis for elements of Marxism–Leninism predate this. Marxism–Leninism descends from the ] ("Majority") faction of the ] (RSDLP) that was founded in the RSDLP's Second Congress in 1903.<ref>Bottomore, pp. 53–54.</ref> The Bolshevik faction led by Lenin advocated an active, politically committed vanguard party membership while opposing trade union based membership of ] parties.<ref name="massaschussetts1991">Bottomore, p. 54.</ref> The Bolsheviks supported a vanguard Marxist party composed of active militants committed to socialism who would initiate communist revolution.<ref name="massaschussetts1991"/> The Bolsheviks advocated the policy of democratic centralism that would allow members to elect their leaders and decide policy, but that once policy was set members would be obligated to have complete loyalty in their leaders.<ref name="massaschussetts1991"/> | |||

| === October Revolution and Russian Civil War (1917–1922) === | |||

| Lenin attempted and failed to bring about communist revolution in Russia in the Russian ]–].<ref name="massaschussetts2">Bottomore, p. 259.</ref> During the revolution, Lenin advocated mass action and that the revolution "accept mass terror in its tactics".<ref>Ulam, p. 257.</ref> During the revolution, Lenin advocated militancy and violence of workers as a means to pressure the middle class to join and overthrow the ].<ref>Ulam, p. 204.</ref> Bolshevik emigres briefly poured into Russia to take part in the revolution. Prior and after the failed revolution, the Bolshevik leadership voluntarily resided in exile to evade Tsarist Russia's secret police, such as Lenin who resided in ].<ref name="intellectual1965">Ulam, p. 207.</ref> Most importantly, the experience of this revolution caused Lenin to conceive of the means of sponsoring communist revolution through ], ], a well-organised and disciplined but small political party.<ref name="intellectual1965"/> | |||

| {{Main|October Revolution|Russian Civil War}} | |||

| ] in the ] featured ] between the ] (KPD) and anti-communist Freikorps units called in by the German government led by the ] (SPD).]] | |||