| Revision as of 00:47, 27 October 2006 view sourceRossnixon (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers4,330 editsm →In the Hebrew Bible: haven't seen that spelling before← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:37, 5 January 2025 view source Feline Hymnic (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers16,250 edits →Christian iconography: Edit per talk page. The cited reference was not a reliable source. So remove a strange claim, and add a "citation needed" for a remaining claim. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Hebrew patriarch according to the Hebrew Bible}} | ||

| {{Redirect-several|Abraham|Abram|Avraham|Avram}} | |||

| :''For other people called Abraham, see ]; Abram redirects here; see ] for the English village.'' | |||

| {{Pp|small=yes}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{Pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2020}} | |||

| {{Infobox religious person | |||

| | title = | |||

| | image = ] | |||

| | caption = {{nowrap|'']'' (1657)}}<br />{{nowrap|by ]}} | |||

| | header1 = | |||

| | known_for = Namesake of the ]: traditional founder of the ],{{sfn|Levenson|2012|p=3}}{{sfn|Mendes-Flohr|2005}} spiritual ancestor of ],{{sfn|Levenson|2012|p=6}} major ],{{sfn|Levenson|2012|p=8}} ] and originator of ] faith in ],{{Sfn|Smith|2000a|p=22, 231}} third spokesman (''natiq'') prophet of ]s{{sfn|Swayd|2009|p=3}} | |||

| | spouse = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (concubine) | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | name = Abraham | |||

| | native_name = אַבְרָהָם | |||

| | native_name_lang = Hbo | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | parents = | |||

| | father = ] | |||

| | mother = ], according to ] | |||

| | children = {{Collapsible list | |||

| | title = {{nobold|Oldest to youngest:}} | |||

| | ] (son, with Hagar) | |||

| | ] (son, with Sarah) | |||

| | ] (son, with Keturah) | |||

| | ] (son, with Keturah) | |||

| | ] (son, with Keturah) | |||

| | ] (son, with Keturah) | |||

| | ] (son, with Keturah) | |||

| | ] (son, with Keturah) | |||

| }} | |||

| | relatives = {{Collapsible list | |||

| | title = {{nobold|Closest to furthest:}} | |||

| | ] (brother) | |||

| | ] (brother) | |||

| | ] (half-sister and wife) | |||

| | ] (grandson) | |||

| | ] (grandson) | |||

| | ] (nephew) | |||

| | ] (great-grandsons) | |||

| | ] (great-granddaughter) | |||

| | see: '']'' | |||

| }} | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | background = | |||

| | religion = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Abraham'''{{efn|{{IPAc-en|ˈ|eɪ|b|r|ə|h|æ|m|,_|-|h|ə|m}}; {{Hebrew name|{{Script/Hebrew|אַבְרָהָם}}|ʾAvraham|ʾAḇrāhām}}; {{langx|grc-x-biblical|Ἀβραάμ}}, {{Transliteration|grc|Abraám}}; {{langx|ar|{{Script/Arabic|إبراهيم}}}}, {{Transliteration|ar|Ibrāhīm}}|name=|group=}} (originally '''Abram'''){{efn|{{Hebrew name|{{Script/Hebrew|אַבְרָם}}|ʾAvram|ʾAḇrām}}}} is the common ] ] of the ], including ], ], and ].{{sfn|McCarter|2000|p=8}} In Judaism, he is the founding father of the ] between the ] and ]; in Christianity, he is the spiritual progenitor of all believers, whether Jewish or ];{{efn|{{harvnb|Jeffrey|1992|p=10}} writes "In the NT Abraham is recognized as the father of Israel and of the Levitical priesthood (Heb. 7), as the "legal" forebear of Jesus (i.e. ancestor of Joseph according to Matt. 1), and spiritual progenitor of all Christians (Rom. 4; Gal. 3:16, 29; cf. also the ''Visio Pauli'')"}}{{sfn|Wright|2010|p=72}} and ], he is a link in the ] that begins with ] and culminates in ].{{sfn|Levenson|2012|p=8}} As the namesake of the Abrahamic religions, Abraham is also revered in other Abrahamic religions, such as the ] faith and the ].{{sfn|Swayd|2009|p=3}}{{Sfn|Smith|2000a|p=22, 231}} | |||

| '''Abraham''' (]: '''{{lang|he|אַבְרָהָם}}''', <small>]</small> '''''Avraham''''' <small>]</small> '''''Avrohom''''' or '''''Avruhom''''' <small>]</small> ''{{Unicode|ʾAḇrāhām}}'' ; ]: '''{{lang|ar|ابراهيم}}''', '']'' ; ]: {{lang|gez|አብርሃም}}, ''{{Unicode|ʾAbrəham}}'') is regarded as the founding ] of the ] in ], ] and ]ic traditon. Abraham was chosen by God to be blessed and was made into a blessing for all peoples on Earth. His life as narrated in the book of ] (chapters 11–25) reflects the traditions of different ages, and Abraham is not regarded a historical figure by secular scholars. | |||

| The story of the life of Abraham, as told in the narrative of the ] in the ], revolves around the themes of posterity and land. He is said to have been called by God to leave the house of his father ] and settle in the land of ], which God now promises to Abraham and his progeny. This promise is subsequently inherited by ], Abraham's son by his wife ], while Isaac's half-brother ] is also promised that he will be the founder of a great nation. Abraham purchases a tomb (the ]) at ] to be Sarah's grave, thus establishing his right to the land; and, in the second generation, his heir Isaac is married to a woman from his own kin to earn his parents' approval. Abraham later marries ] and has six more sons; but, on his death, when he is buried beside Sarah, it is Isaac who receives "all Abraham's goods" while the other sons receive only "gifts".{{sfn|Ska|2009|pp=26–31}} | |||

| His original name was '''Abram''' (]: '''{{lang|he|אַבְרָם}}''', <small>]</small> '''''Avram''''' <small>]</small> ''{{Unicode|ʾAḇrām}}'') meaning either "exalted ]" or " father is exalted" (compare '']''). Later in life he went by the name Abraham, often glossed as ''av hamon (goyim)'' "father of many (nations)" per {{sourcetext|source=Bible|version=King James|book=Genesis|chapter=17|verse=5}} , but it does not have any literal meaning in Hebrew.<ref> states, "The form | |||

| 'Abraham' yields no sense in Hebrew". Many interpretations were offered, including an analysis of a first element ''abr-'' "chief", which however yields a meaningless second element.</ref> | |||

| Most scholars view the ], along with ] and the period of the ], as a late literary construct that does not relate to any particular historical era,{{sfn|McNutt|1999|pp=41–42}} and after a century of exhaustive archaeological investigation, no evidence has been found for a historical Abraham.{{sfn|Dever|2001|p=98}}<ref>Frevel, Christian. ''History of Ancient Israel''. Atlanta, Georgia. ]. 2023. p. 38. ISBN 9781628375138. "t cannot be proven or excluded that there have been historical persons named Abraham, Sarai, Ishmael, Isaac, Rebekah, Jacob, Rachel, Leah, and so on."</ref> It is largely concluded that the ], the series of books that includes Genesis, was composed during the ], {{Circa|500 BC}}, as a result of tensions between Jewish landowners who had stayed in ] during the ] and traced their right to the land through their "father Abraham", and the returning exiles who based their counterclaim on ] and the Exodus tradition of the ].{{sfn|Ska|2006|pp=227–228, 260}} | |||

| Judaism, Christianity and Islam are sometimes referred to as the "]s", because of the role Abraham plays in their holy books and beliefs. In the ] and the ], Abraham is described as a patriarch blessed by God (Genesis 17:4-5). In the Jewish tradition, he is called ''Avraham Avinu'' or "Abraham, our Father". God promised Abraham that through his offspring, all the nations of the world will come to be blessed (Genesis 12:3), interpreted in Christian tradition as a reference to ]. Jews, Christians, and Muslims consider him father of the ] through his son ] (cf. Exodus 6:3, Exodus 32:13). For Muslims, he is a ] and the ] of ] through his other son ]. | |||

| == |

==The Abraham cycle in the Bible== | ||

| {{main|Abraham (Hebrew Bible)}} | |||

| ===Structure and narrative programs=== | |||

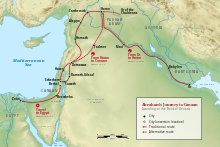

| His father, ], came from ] of the ], popularly identified since 1927 by Sir Charles Woolley with an ancient city in southern ] which was under the rule of the Chaldeans — although ], Islamic tradition, and Jewish authorities like Maimonides all concur that ] was in Northern Mesopotamia — now southeastern ] (identified with ], ], and ] respectively). This is in accord with the local tradition that Abraham was born in Urfa, or with the nearby ], which others identify with “Ur of the Chaldees”. They also say “Chaldees” refers to a group of gods called ] {{fact}}. Abram migrated to ], apparently the classical ], on a branch of the ]. Thence, after a short stay, he, his wife ], ] (the son of Abram's brother ]), and all their followers, departed for ]. There are two cities possibly identifiable with the biblical Ur, neither far from Haran: Ura and Urfa, a northern Ur also being mentioned in tablets at ], ], and ]. These possibly refer to Ur, Ura, and Urau (See ''BAR'' January 2000, page 16). Moreover, the names of Abram's forefathers ], ], ], and Terah, all appear as names of cities in the region of Haran (''Harper's Bible Dictionary'', page 373). God called Abram to go to "the land I will show you", and promised to bless him and make him (though hitherto childless) a great nation. Trusting this promise, Abram journeyed down to ], and at the sacred tree (compare Gen. 35:4, ] 24:26, ] 9:6) received a new promise that the land would be given unto his seed (descendant or descendants). Having built an ] to commemorate the ], he removed to a spot between ] and ], where he built another altar and called upon (i.e. invoked) the name of God (Gen. 12:1-9). | |||

| The Abraham cycle is not structured by a unified plot centered on a conflict and its resolution or a problem and its solution.{{sfn|Ska|2009|p=28}} The episodes are often only loosely linked, and the sequence is not always logical, but it is unified by the presence of Abraham himself, as either actor or witness, and by the themes of posterity and land.{{sfn|Ska|2009|pp=28–29}} These themes form "narrative programs" set out in concerning the sterility of Sarah and in which Abraham is ordered to leave the land of his birth for the land God will show him.{{sfn|Ska|2009|pp=28–29}} | |||

| ===Origins and calling=== | |||

| Here he dwelt for some time, until strife arose between his herdsmen and those of his nephew, Lot. Abram thereupon proposed to Lot that they should separate, and allowed Lot the first choice. Lot preferred the fertile land lying east of the ], while Abram, after receiving another promise from Yahweh, moved down to the oaks of ] in ] and built an altar. | |||

| ] | |||

| ], the ninth in descent from ], was the father of Abram, ], ] ({{langx|he|הָרָן}} ''Hārān'') and ].<ref>Freedman, Meyers & Beck. ''Eerdmans dictionary of the Bible'' {{ISBN|978-0-8028-2400-4}}, 2000, p. 551 and {{bibleverse|Genesis|20:12|niv}}</ref> Haran was the father of ], who was Abram's nephew; the ] lived in ]. Haran died there. Abram married ]. Terah, Abram, Sarai, and Lot departed for ], but settled in a place named ] ({{langx|he|חָרָן}} ''Ḥārān''), where Terah died at the age of 205.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=The Chronology of the Pentateuch: A Comparison of the MT and LXX|author=Larsson, Gerhard|year=1983|journal=Journal of Biblical Literature|volume=102|issue=3|pages=401–409|doi=10.2307/3261014|jstor=3261014 | issn = 0021-9231 }}</ref> According to some exegetes (like ]), Abram was actually born in Haran and he later relocated to Ur, while some of his family remained in Haran.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://tobias-lib.ub.uni-tuebingen.de/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10900/148219/jbq_444_KleinMeso.pdf|title=Nahmanides' Understanding of Abraham's Mesopotamian Origins | |||

| |author=Klein, Reuven Chaim|year=2016|journal=Jewish Bible Quarterly | |||

| |volume=44|issue=4|pages=233–240}}</ref> | |||

| God had told Abram to leave his country and kindred and go to a land that he would show him, and promised to make of him a great nation, bless him, make his name great, bless them that bless him, and curse them who may curse him. Abram was 75 years old when he left Haran with his wife Sarai, his nephew Lot, and their possessions and people that they had acquired, and traveled to ] in Canaan.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|12:4–6|niv}}</ref> Then he pitched his tent in the east of ], and built an altar which was between Bethel and ]. | |||

| In the subsequent history of Lot was the destruction of ]. In Genesis 18, Abraham pleads with God not to destroy ], and God agrees that he would not destroy the city if there were 50 righteous people in it, or 45, or 30, 20, even 10 righteous people. (Abraham's nephew ] had been living in Sodom.) | |||

| ===Sarai=== | |||

| Driven by a ] to take refuge in ] (26:11, 41:57, 42:1), Abram feared lest his wife's beauty should arouse the evil designs of the ] and thus endanger his own safety, so he referred to Sarai as his sister. This did not save her from the ], who took her into the royal ] and enriched Abram with herds and servants. But when Yahweh "plagued Pharaoh and his house with great ]" Abram and Sarai left Egypt. There are two other parallel tales in Genesis of ] (Genesis 20-21 and 26) describing a similar event at Gerar with the ] king Abimelech, though the latter attributing it to Isaac not Abraham. | |||

| ], {{circa|1900}} (], New York)]] | |||

| There was a severe famine in the land of Canaan, so that Abram, Lot, and their households traveled to ]. On the way Abram told Sarai to say that she was his sister, so that the Egyptians would not kill him. When they entered Egypt, the Pharaoh's officials praised Sarai's beauty to ], and they took her into the palace and gave Abram goods in exchange. God afflicted Pharaoh and his household with plagues, which led Pharaoh to try to find out what was wrong.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|12:14–17|niv}}</ref> Upon discovering that Sarai was a married woman, Pharaoh demanded that Abram and Sarai leave.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|12:18–20|niv}}</ref> | |||

| ===Abram and Lot separate=== | |||

| As Sarai continued to be infertile, God's promise that Abram's seed would inherit the land seemed incapable of fulfillment. His sole heir was his servant, who was over his household, a certain Eliezer of Damascus (15:2). Abraham is now promised as heir one of his own flesh. The passage recording the ratification of the promise is remarkably solemn (see ] 15). Sarai, in accordance with custom, gave to Abram her Egyptian handmaid ] as his wife.(Gen 16:3) Sarai found that Hagar was with child, unable to endure the reproach of barrenness (cf. the story of ], ] 1:6), dealt harshly with Hagar and forced her to flee (16:1-14). God hears Hagar's sadness and promises her that her descendants will be too numerous to count, and she returns. Her son, ], was Abram's ], but was not the promised child, as God made his covenant with Abram after Ishmael's birth (chapter 16-17). Hagar and Ishmael were eventually driven permanently away from Abraham by Sarah (chapter 21). | |||

| {{main|Abraham and Lot's conflict}} | |||

| When they lived for a while in the ] after being banished from Egypt and came back to the ] and ] area, Abram's and Lot's sizable herds occupied the same pastures. This became a problem for the herdsmen, who were assigned to each family's cattle. The conflicts between herdsmen had become so troublesome that Abram suggested that Lot choose a separate area, either on the left hand or on the right hand, that there be no conflict between them. Lot decided to go eastward to the plain of ], where the land was well watered everywhere as far as ], and he dwelled in the cities of the plain toward ].<ref>{{cite book|author=George W. Coats|title=Genesis, with an Introduction to Narrative Literature|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OrrdUOovklIC&pg=PA113|year=1983|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|isbn=978-0-8028-1954-3|pages=113–114}}</ref> Abram went south to ] and settled in the plain of ], where he built another altar to worship ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vRolnGU5KvAC&pg=PA59|title=The Religion of the Patriarchs|first=Augustine|last=Pagolu|pages= 59–60|date=1 November 1998|publisher=A&C Black|isbn=978-1-85075-935-5 |via=Google Books}}</ref> | |||

| ===Chedorlaomer=== | |||

| The name ''Abraham'' was given to Abram (and the name ] to Sarai) at the same time as the covenant of ] (chapter 17), which is practiced in ] and ] and by many ] to this day. At this time Abraham was promised not only many descendants, but descendants through Sarah specifically, as well as the land where he was living, which was to belong to his descendants. The covenant was to be fulfilled through ], though God promised that Ishmael would become a great nation as well. The covenant of circumcision (unlike the earlier promise) was two-sided and conditional: if Abraham and his descendants fulfilled their part of the covenant, Yahweh would be their God and give them the land. | |||

| {{Main|Battle of Siddim}} | |||

| ], {{Circa|1464}}–1467]] | |||

| During the rebellion of the Jordan River cities, ], against ], Abram's nephew, Lot, was taken prisoner along with his entire household by the invading Elamite forces. The Elamite army came to collect the spoils of war, after having just defeated the king of Sodom's armies.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|14:8–12|niv}}</ref> Lot and his family, at the time, were settled on the outskirts of the Kingdom of Sodom which made them a visible target.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|13:12|niv}}</ref> | |||

| The promise of a son to Abraham made Sarah "laugh," which became the name of the son of promise, Isaac. Sarah herself "laughs" at the idea because of her age, when Yahweh appears to Abraham at Mamre (18:1-15) and, when the child is born, cries "God has made me laugh; every one that hears will laugh at me" (21:6). | |||

| One person who escaped capture came and told Abram what happened. Once Abram received this news, he immediately assembled 318 trained servants. Abram's force headed north in pursuit of the Elamite army, who were already worn down from the ]. When they caught up with them at ], Abram devised a battle plan by splitting his group into more than one unit, and launched a night raid. Not only were they able to free the captives, Abram's unit chased and slaughtered the Elamite King ] at Hobah, just north of ]. They freed Lot, as well as his household and possessions, and recovered all of the goods from Sodom that had been taken.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|14:13–16|niv}}</ref> | |||

| Some time after the birth of Isaac, Abraham was commanded by God to offer his son up as a sacrifice in the land of ]. Proceeding to obey, he was prevented by an ] as he was about to sacrifice his son, and slew a ] which he found on the spot. As a reward for his obedience he received another promise of a numerous seed and abundant prosperity (22). Then he returned to ]. The ] is one of the most challenging, and perhaps ] troublesome, parts of the Bible. According to Josephus, Isaac is 25 years old at the time of the sacrifice or ''Akedah'', while the ]ic sages teach that Isaac is 37. In either case, Isaac is a fully grown man, old enough to prevent the elderly Abraham (who is 125 or 137 years old) from tying him up had he wanted to resist. | |||

| Upon Abram's return, Sodom's king came out to meet with him in the ], the "king's dale". Also, ] king of Salem (]), a priest of ], brought out bread and wine and blessed Abram and God.<ref>Noth, Martin. ''A History of Pentateuchal Traditions'' (Englewood Cliffs 1972) p. 28</ref> Abram then gave Melchizedek a ] of everything. The king of Sodom then offered to let Abram keep all the possessions if he would merely return his people. Abram declined to accept anything other than the share to which his allies were entitled. | |||

| The primary interest of the narrative now turns to Isaac. To his "only son" (22:2, 12) Abraham gave all he had, and dismissed the sons of his concubines to the lands outside ]; they were thus regarded as less intimately related to ] and his descendants (25:1-6). See also: ], ]. | |||

| ===Covenant of the pieces=== | |||

| Sarah died at an old age, and was buried in the ] near ], which Abraham had purchased, along with the adjoining field, from ] (Genesis 23). Here Abraham himself was buried. Centuries later the tomb became a place of ] and ]s later built an ]ic ] inside the site. | |||

| {{see also|Covenant of the pieces}} | |||

| The voice of the Lord came to Abram in a vision and repeated the promise of the land and descendants as numerous as the stars. Abram and God made a covenant ceremony, and God told of the future bondage of Israel in Egypt. God described to Abram the land that his offspring would claim: the land of the ], ]s, ], ], ], Rephaims, ], ], ], and ]s.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Zeligs |first=Dorothy F. |date=1961 |title=Abraham and the Covenant of the Pieces: A Study in Ambivalence |journal=American Imago |volume=18 |issue=2 |pages=173–186 |jstor=26301751 |issn=0065-860X}}</ref> | |||

| Abraham is considered the father of the Jewish nation, as their first Patriarch, and having a son (Isaac), who in turn begat ], and from there the ]. To father the nation, God "tested" Abraham with ten tests, the greatest being his willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac. God promised the land of Israel to his children, and that is the first claim of the Jews to Israel. Judaism ascribes a special trait to each Patriarch. Abraham's was kindness. Because of this, Judaism considers kindness to be an inherent Jewish trait. | |||

| ===Hagar=== | |||

| According to the 1st Century Jewish Historian Flavius Josephus in his twenty-one volume Antiquities of the Jews "Nicolaus of Damascus, in the fourth book of his History, says thus: "Abraham reigned at Damascus, being a foreigner, who came with an army out of the land above Babylon, called the land of the Chaldeans: but, after a long time, he got him up, and removed from that country also, with his people, and went into the land then called the land of Canaan, but now the land of Judea, and this when his posterity were become a multitude; as to which posterity of his, we relate their history in another work. Now the name of Abraham is even still famous in the country of Damascus; and there is shown a village named from him, The Habitation of Abraham." He is an important source for studies of immediate post-Temple Judaism | |||

| {{see also|Hagar|Hagar in Islam}} | |||

| ] and ]'', Bible illustration from 1897]] | |||

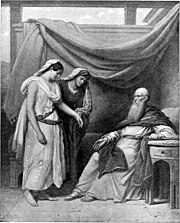

| Abram and Sarai tried to make sense of how he would become a progenitor of nations, because after 10 years of living in Canaan, no child had been born. Sarai then offered her Egyptian slave, ], to Abram with the intention that she would bear him a son.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=53&letter=H |title=Jewish Encyclopedia, ''Hagar'' |publisher=Jewishencyclopedia.com}}</ref> | |||

| ===The Genesis narrative=== | |||

| Biblical narratives represent Abraham as a wealthy, powerful and supremely virtuous man, but humanly flawed, and when afraid for himself, miscalculating, and a sometimes deceiver and an inconsiderate husband. But his central importance in the Book of Genesis, and his portrait as a man favored by God, is unequivocal. Abraham's generations (Hebrew: '']'', translated to Greek: "Genesis") are presented as part of the crowning explanation of how the world has been fashioned by the hand of God, and how the boundaries and relationships of peoples were established by him. | |||

| After Hagar found she was pregnant, she began to despise her mistress, Sarai. Sarai responded by mistreating Hagar, and Hagar fled into the wilderness. An angel spoke with Hagar at the fountain on the way to ]. He instructed her to return to Abram's camp and that her son would be "a wild ass of a man; his hand shall be against every man, and every man's hand against him; and he shall dwell in the face of all his brethren." She was told to call her son ]. Hagar then called God who spoke to her "]", ("Thou God seest me:" KJV). From that day onward, the well was called Beer-lahai-roi, ("The well of him that liveth and seeth me." KJV margin), located between ] and Bered. She then did as she was instructed by returning to her mistress in order to have her child. Abram was 86 years of age when Ishmael was born.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|16:4–16|niv}}</ref> | |||

| As the father of Isaac and Ishmael, Abraham is ultimately the common ancestor of the ] and their neighbours. As the father of ], whose twelve sons became desert princes (most prominently, ] and ]), along with ], ] and other ]ian tribes (25:1-4), the Book of Genesis gives a portrait of Isaac's descendants as being surrounded by kindred peoples, who are also ofttimes enemies. It seems that some degree of kinship was felt by the ] with the dwellers of the more distant south, and it is characteristic of the genealogies that the mothers (Sarah, the Egyptian, Hagar, and ]) are in the descending scale, perhaps of purity of blood, or as of purity of relationship, or of connectedness to Sarah: Sarah, her servant, her husband's other wife. The Bible says of the Hebrew people: "Your father was a wandering Syrian". | |||

| ===Sarah=== | |||

| As stated above, Abraham came from Ur in ] to Haran and thence to ]. Late tradition supposed that the ] was to escape Babylonian idolatry (] 5, ] 12; cf. ] 24:2), and knew of Abraham's miraculous escape from death (an obscure reference to some act of deliverance in ] 29:22). The route along the banks of the ] from south to north was so frequently taken by migrating tribes that the tradition has nothing improbable in itself. It was thence that ], the father of the tribes of Israel, came, and the route to ] and ] is precisely the same in both. | |||

| Thirteen years later, when Abram was 99 years of age, God declared Abram's new name: "Abraham" – "a father of many nations".<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|17:5|niv}}</ref> Abraham then received the instructions for the ], of which ] was to be the sign.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|17:10–14|niv}}</ref> | |||

| God declared Sarai's new name: "]", blessed her, and told Abraham, "I will give thee a son also of her".<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|17:15–16|niv}}</ref> Abraham laughed, and "said in his heart, 'Shall a ''child'' be born unto him that is a hundred years old? and shall Sarah, that is ninety years old, bear ?'"<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|17:17|niv}}</ref> Immediately after Abraham's encounter with God, he had his entire household of men, including himself (age 99) and Ishmael (age 13), circumcised.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|17:22–27|niv}}</ref> | |||

| Further, there is yet another parallel in the story of the conquest by Joshua, partly implied and partly actually detailed (cf. also Joshua 8:9 with Gen. 12:8, 13:3), whence it would appear that too much importance must not be laid upon any ] interpretation which fails to account for the three versions. That similar traditional elements have influenced them is not unlikely; but to recover the true historical foundation is difficult. The invasion or immigration of certain tribes from the east of the ]; the presence of ] blood among the Israelites; the origin of the sanctity of venerable sites — these and other considerations may readily be found to account for the traditions. | |||

| ==={{anchor|Three visitors}}Three visitors=== | |||

| Noteworthy coincidences in the lives of Abraham and Isaac, such as the strong parallels between two tales of ], point to the fluctuating state of traditions in the oral stage, or suggest that Abraham's life has been built up by borrowing from the common stock of popular lore. More original is the parting of Lot and Abraham at Bethel. The district was the scene of contests between ] and the Hebrews (cf. perhaps ] 3), and if this explains part of the story, the physical configuration of the ] may have led to the legend of the destruction of inhospitable and vicious cities.{{fact}} | |||

| ], {{circa|1896–1902|lk=no}}]] | |||

| Not long afterward, during the heat of the day, Abraham had been sitting at the entrance of his tent by the ]s of ]. He looked up and saw three men in the presence of God. Then he ran and bowed to the ground to welcome them. Abraham then offered to wash their feet and fetch them a morsel of bread, to which they assented. Abraham rushed to Sarah's tent to order ]s made from choice flour, then he ordered a servant-boy to prepare a choice calf. When all was prepared, he set curds, milk and the calf before them, waiting on them, under a tree, as they ate.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|18:1–8|niv}}</ref> | |||

| ==In the New Testament== | |||

| In the ] Abraham is mentioned prominently as a man of ] (see e.g., ] 11), and the apostle ] uses him as an example of ] by faith, as the progenitor of the ] (or ]) (see ] 3:16). | |||

| One of the visitors told Abraham that upon his return next year, Sarah would have a son. While at the tent entrance, Sarah overheard what was said and she laughed to herself about the prospect of having a child at their ages. The visitor inquired of Abraham why Sarah laughed at bearing a child at her age, as nothing is too hard for God. Frightened, Sarah denied laughing.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|18:15|niv}}</ref> | |||

| Authors of the New Testament report that Jesus cited Abraham to support belief in the ] of the dead. "But concerning the dead, that they rise, have you not read in the ], in the ] passage, how God spoke to him, saying, "I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob?" He is not the God of the dead, but the God of the living. You are therefore greatly mistaken" (] 12:26-27). The New Testament also sees Abraham as an obedient man of God, and Abraham's interrupted attempt to offer up ] is seen as the supreme act of perfect faith in God. "By faith Abraham, when he was tested, offered up Isaac, and he who had received the promises offered up his only begotten son, of whom it was said, "In Isaac your seed shall be called," concluding that God was able to raise him up, even from the dead, from which he also received him in a figurative sense." (''Hebrews'' 11:17-19) | |||

| ===Abraham's plea=== | |||

| The traditional view in ] is that the chief promise made to Abraham in ''Genesis'' 12 is that through Abraham's seed, all the people of earth would be blessed. Notwithstanding this, ] specifically taught that merely being of Abraham's seed was no guarantee of ]. The promise in Genesis is considered to have been fulfilled through Abraham's seed, Jesus. It is also a consequence of this promise that Christianity is open to people of all races and not limited to Jews. | |||

| {{main|Sodom and Gomorrah|Lot (biblical person)}} | |||

| ], {{circa|1896–1902|lk=no}}]] | |||

| After eating, Abraham and the three visitors got up. They walked over to the peak that overlooked the 'cities of the plain' to discuss the fate of ] for their detestable sins that were so great, it moved God to action. Because Abraham's nephew was living in Sodom, God revealed plans to confirm and judge these cities. At this point, the two other visitors left for Sodom. Then Abraham turned to God and pleaded decrementally with Him (from fifty persons to less) that "if there were at least ten righteous men found in the city, would not God spare the city?" For the sake of ten righteous people, God declared that he would not destroy the city.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|18:17–33|niv}}</ref> | |||

| The ] calls Abraham "our father in Faith," in the ] called the ''Roman Canon'', recited during the ]. (See ]). | |||

| When the two visitors arrived in Sodom to conduct their report, they planned on staying in the city square. However, Abraham's nephew, Lot, met with them and strongly insisted that these two "men" stay at his house for the night. A rally of men stood outside of Lot's home and demanded that Lot bring out his guests so that they may "know" ({{Abbr|v.|verse}} 5) them. However, Lot objected and offered his virgin daughters who had not "known" (v. 8) man to the rally of men instead. They rejected that notion and sought to break down Lot's door to get to his male guests,<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|19:1–9|niv}}</ref> thus confirming the wickedness of the city and portending their imminent destruction.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|19:12–13|niv}}</ref> | |||

| ==In Islam== | |||

| {{main|Ibrahim}} | |||

| Abraham, known as ] in Arabic, is very important in ], both in his own right as a prophet as well as being the father of ] and ]. Ishmael, his firstborn son, is considered the ''Father of the Arabs'', and Isaac is considered the ''Father of the Hebrews''. Abraham is revered by Muslims as one of the most important ], and is commonly termed ''Khalil Ullah'', "Friend of God". Abraham is considered a ], that is, a discoverer of ]. | |||

| Early the next morning, Abraham went to the place where he stood before God. He "looked out toward Sodom and Gomorrah" and saw what became of the cities of the plain, where not even "ten righteous" (v. 18:32) had been found, as "the smoke of the land went up as the smoke of a furnace."<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|19:27–29|niv}}</ref> | |||

| Muslims believe Abraham built the ], the Holy Mosque in ], during his life. The construction of the Kaaba was upon God's command. Abraham's footprint is believed to remain to this day on a stone in the Holy Mosque. The annual ], the fifth ], follows Abraham, ], and Ishmael's journey to the sacred place of the Kaaba. The ] ceremony is focused on Abraham's willingess to sacrifice his promised son, which Muslims consider Ishmael, on God's command. | |||

| == |

===Abimelech=== | ||

| ], before 1903 (], New York)]] | |||

| A line in the ] (20:13) mentions that the descendants of Abraham's son by Hagar, Ishmael, as well as his descendants by Keturah, became the "Arabians". The 1st century Jewish historian ] similarly described the descendants of Ishmael (i.e. the Ishmaelites) as an "Arabian" people. <ref>Antiquities of the Jews, book 1, 12:4</ref> He also calls Ishmael the "founder" (κτίστης) of the "Arabians". <ref>Antiquities of the Jews, book 1, 12:2</ref> Some Biblical scholars also believe that the area outlined in Genesis as the final destination of Ishmael and his descendants ("from Havilah to Assyria") refers to the ]. This has led to a commonplace view that modern Semitic-speaking Arabs are descended from Abraham via Ishmael, in addition to various other tribes who intermixed with the Ishmaelites, such as Joktan, Sheba, Dedan, etc. Both Judaeo-Christian and Islamic tradition speak of earlier inhabitants of Arabia, and the Nabateans are not the ancestors of the modern Arabs having assimilated into the Syriac, Jewish and Greek Middle Eastern communities of Late Antiquity.{{fact}} | |||

| {{see also|Endogamy|Wife–sister narratives in the Book of Genesis}} | |||

| Classical Arab historians traced the ] (i.e. the original Arabs from Yemen) to Qahtan and the Arabicised Arabs (people from the region of Mecca who assimilated into the Arabs) to Adnan, said to be an ancestor of Muhammed, and have further equated Ishmael with A'raq Al-Thara said to be ancestor of Adnan. ], one of Muhammed's wives, wrote that this was done using the following hermeneutical reasoning: ''Thara'' means moist earth, Abraham was not consumed by hell-fire, fire does not consume moist earth, thus A'raq al-Thara must be Ishmael son of Abraham. <ref>The Life of the Prophet Muhammad (Al-Sira al-Nabawiyya), Volume I, translated by professor Trevor Le Gassick, reviewed by Dr. Ahmed Fareed , pp. 50-52;</ref> | |||

| Abraham settled between ] and ] in what the Bible anachronistically calls "the land of the ]s". While he was living in ], Abraham openly claimed that Sarah was his sister. Upon discovering this news, King ] had her brought to him. God then came to Abimelech in a dream and declared that taking her would result in death because she was a man's wife. Abimelech had not laid hands on her, so he inquired if he would also slay a righteous nation, especially since Abraham had claimed that he and Sarah were siblings. In response, God told Abimelech that he did indeed have a blameless heart and that is why he continued to exist. However, should he not return the wife of Abraham back to him, God would surely destroy Abimelech and his entire household. Abimelech was informed that Abraham was a prophet who would pray for him.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|20:1–7|niv}}</ref> | |||

| Early next morning, Abimelech informed his servants of his dream and approached Abraham inquiring as to why he had brought such great guilt upon his kingdom. Abraham stated that he thought there was no fear of God in that place, and that they might kill him for his wife. Then Abraham defended what he had said as not being a lie at all: "And yet indeed ''she is'' my sister; she ''is'' the daughter of my father, but not the daughter of my mother; and she became my wife."<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|20:12||Genesis 20:12|niv}}</ref> Abimelech returned Sarah to Abraham, and gave him gifts of sheep, oxen, and servants; and invited him to settle wherever he pleased in Abimelech's lands. Further, Abimelech gave Abraham a thousand pieces of silver to serve as Sarah's vindication before all. Abraham then prayed for Abimelech and his household, since God had stricken the women with infertility because of the taking of Sarah.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|20:8–18|niv}}</ref> | |||

| ==In Mormonism== | |||

| Abraham is an important figure in Mormonism, and is referenced in several ]. | |||

| After living for some time in the land of the Philistines, Abimelech and ], the chief of his troops, approached Abraham because of a dispute that resulted in a violent confrontation at a well. Abraham then reproached Abimelech due to his Philistine servant's aggressive attacks and the seizing of ]. Abimelech claimed ignorance of the incident. Then Abraham offered a pact by providing sheep and oxen to Abimelech. Further, to attest that Abraham was the one who dug the well, he also gave Abimelech seven ewes for proof. Because of this sworn oath, they called the place of this well: ]. After Abimelech and Phicol headed back to ], Abraham planted a ] grove in Beersheba and called upon "the name of the {{LORD}}, the everlasting God."<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|21:22–34||Genesis 21:22–34|niv}}</ref> | |||

| The ], found in the ], has five chapters. Chapters 1 and 2 include details about Abraham’s early life and his fight against the idolatry of his society and even of his own family. It recounts how pagan priests tried to sacrifice him to their god, but an angel appeared and rescued him. Chapter 2 includes information about God’s covenant with Abraham, and how it would be fulfilled: "And thou shalt be a blessing unto thy seed after thee, that in their hands they shall bear this ministry and Priesthood unto all nations; And I will bless them through thy name; for as many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed, and shall rise up and bless thee, as their father;...and in thy seed after thee ... shall all the families of the earth be blessed, even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal." (Abraham 2:9-11) | |||

| ===Isaac=== | |||

| Thus, Mormonism considers Abraham the "father of the faithful," who was blessed with covenant promises because he sought to regain the true priesthood and the true gospel possessed by others on earth such as Melchizedek, and because he was willing to follow the Lord's guidance and direction in all things, not withholding anything. | |||

| As had been prophesied in Mamre the previous year,<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|17:21|niv}}</ref> Sarah became pregnant and bore a son to Abraham, on the first anniversary of the covenant of circumcision. Abraham was "an hundred years old", when his son whom he named ] was born; and he circumcised him when he was eight days old.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|21:1–5|niv}}</ref> For Sarah, the thought of giving birth and nursing a child, at such an old age, also brought her much laughter, as she declared, "God hath made me to laugh, so that all who hear will laugh with me."<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|21:6–7|niv}}</ref> Isaac continued to grow and on the day he was weaned, Abraham held a great feast to honor the occasion. During the celebration, however, Sarah found Ishmael mocking; an observation that would begin to clarify the birthright of Isaac.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|21:8–13|niv}}</ref> | |||

| Chapters 3 through 5 are a vision in which God reveals much about astronomy, the creation of the world, foreordination, and the creation of man. It agrees closely with ]’ account of the creation, but gives more detail. | |||

| ===Ishmael=== | |||

| In addition to the text, there are three facsimiles of vignettes from the papyrus. One depicts Abraham about to be sacrificed by a priest; the second is the ] which contains important insights about the organization of the heavens. The final picture shows Abraham teaching in the ]’s court. | |||

| {{See also|Ishmael in Islam#The sacrifice}} | |||

| ], {{circa|1699|lk=no}} (], Rhode Island)]] | |||

| Ishmael was fourteen years old when Abraham's son Isaac was born to Sarah. When she found Ishmael teasing Isaac, Sarah told Abraham to send both Ishmael and Hagar away. She declared that Ishmael would not share in Isaac's inheritance. Abraham was greatly distressed by his wife's words and sought the advice of his God. God told Abraham not to be distressed but to do as his wife commanded. God reassured Abraham that "in Isaac shall seed be called to thee."<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|21:12|niv}}</ref> He also said Ishmael would make a nation, "because he is thy seed".<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|21:9–13|niv}}</ref> | |||

| The ], part of the ], claims that God's commandment that Abraham sacrifice Isaac was "a similitude of God and his Only Begotten Son" (Jacob 4:5). | |||

| Early the next morning, Abraham brought Hagar and Ishmael out together. He gave her bread and water and sent them away. The two wandered in the wilderness of Beersheba until her bottle of water was completely consumed. In a moment of despair, she burst into tears. After God heard the boy's voice, an ] confirmed to Hagar that he would become a great nation, and will be "living on his sword". A well of water then appeared so that it saved their lives. As the boy grew, he became a skilled ] living in the wilderness of ]. Eventually his mother found a wife for Ishmael from her home country, the land of Egypt.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|21:14–21|niv}}</ref> | |||

| ==In philosophy== | |||

| Abraham, as a man communicating with God or the divine, has inspired some fairly extensive discussion in some ]s, such as ] and ]. Kierkegaard goes into Abraham's plight in considerable detail in his work '']''. Sartre understands the story not in terms of Christian obedience or a "teleological suspension of the ethical", but in terms of mankind's utter behavioral and moral freedom. God asks Abraham to sacrifice his only son. Sartre doubts that Abraham can know that the voice he hears is really the voice of his God and not of someone else, or the product of a mental condition. Thus, Sartre concludes, even if there are signs in the world, humans are totally free to decide how to interpret them. | |||

| ===Binding of Isaac=== | |||

| {{main|Binding of Isaac}} | |||

| ], 1635 (], Saint Petersburg)]] | |||

| At some point in Isaac's youth, Abraham was commanded by God to offer his son up as a sacrifice in the land of ]. The patriarch traveled three days until he came to the mount that God told him of. He then commanded the servants to remain while he and Isaac proceeded alone into the mount. Isaac carried the wood upon which he would be sacrificed. Along the way, Isaac asked his father where the animal for the burnt offering was, to which Abraham replied "God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering". Just as Abraham was about to sacrifice his son, he was interrupted by the angel of the Lord, and he saw behind him a "ram caught in a thicket by his horns", which he sacrificed instead of his son. The place was later named as ]. For his obedience he received another promise of numerous descendants and abundant prosperity. After this event, Abraham went to Beersheba.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|22:1–19||Genesis 22:1–19|niv}}</ref> | |||

| ==Textual criticism== | |||

| Writers have regarded the life of Abraham in various ways. He has been viewed as a ] of the ], as the head of a great ] migration from ]; or, since Ur and Haran were seats of ]-worship, he has been identified with a moon-god. From the character of the literary evidence and the locale of the stories it has been held that Abraham was originally associated with Hebron. The double name Abram/Abraham has even suggested that two personages have been combined in the Biblical narrative; although this does not explain the change from Sarai to Sarah. | |||

| ===Later years=== | |||

| The interesting discovery of the name ''Abi-ramu'' on Babylonian contracts of about 2000 BC/BCE does not prove the Abraham of the Old Testament to be an historical person, even as the fact that there were ] in Babylonia at the same period does not make it certain that the 'patriarch' was one of their number. | |||

| {{see also|Abraham's family tree}} | |||

| A fairly lucid treatment of the subject is given by Michael Astour in ''The Anchor Bible Dictionary'' (s.v. "Amraphel", "Arioch", "Chedorlaomer", and "Arioch"), who explains the story of Genesis 14 as a product of anti-Babylonian propaganda during the ] of the Jews: | |||

| Sarah died, and Abraham buried her in the ] (the "cave of Machpelah"), near Hebron which he had purchased along with the adjoining field from Ephron the ].<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|23:1–20|niv}}</ref> After the death of Sarah, Abraham took another wife, a ] named ], by whom he had six sons: ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|25:1–6|niv}}</ref> According to the Bible, reflecting the change of his name to "Abraham" meaning "a father of many nations", Abraham is considered to be the progenitor of many nations mentioned in the Bible, among others the ], ],<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|25:12–18|niv}}</ref> ]ites,<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|36:1–43}}</ref> ],<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|36:12–16|niv}}</ref> ]s,<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|36:9–16|niv}}</ref> ]ites and ],<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|25:1–5|niv}}</ref> and through his nephew Lot he was also related to the ]ites and ]ites.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|19:35–38|niv}}</ref> Abraham lived to see Isaac marry ], and to see the birth of his twin grandsons ]. He died at age 175, and was buried in the cave of Machpelah by his sons Isaac and Ishmael.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|25:7–10|niv}}, {{bibleverse|1 Chronicles|1:32|niv}}</ref> | |||

| ==Historicity and origins of the narrative== | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| {{Main|Historicity of the Bible}} | |||

| "After Böhl's widely accepted, but wrong, identification of <sup>]</sup>Tu-ud-hul-a with one of the Hittite kings named ]s, Tadmor found the correct solution by equating him with the Assyrian king Sennacherib (see Tidal). Astour (1966) identified the remaining two kings of the Chedorlaomer texts with Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria (see Arioch) and with the Chaldean Merodach-baladan (see Amraphel). The common denominator between these four rulers is that each of them, independently, occupied Babylon, oppressed it to a greater or lesser degree, and took away its sacred divine images, including the statue of its chief god Marduk; furthermore, all of them came to a tragic end. <br> | |||

| '''3. Relationship to Genesis 14.''' All attempts to reconstruct the link between the Chedorlaomer texts and Genesis 14 remain speculative. However, the available evidence seems consistent with the following hypothesis: A Jew in Babylon, versed in Akkadian language and cuneiform script, found in an early version of the Chedorlaomer texts certain things consistent with his anti-Babylonian feelings. ..." (''The Anchor Bible Dictionary'', s.v. "Chedorlaomer") | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| ===Historicity=== | |||

| Another scholar, criticizing Kitchen's maximalist viewpoint, considers a relationship between the tablet and Gen. speculative, also identifies but identifies Tudhula as a veiled reference to Sennacherib of Assyria, and Chedorlaomer, i.e. Kudur-Nahhunte, as "a recollection of a 12th-century B.C.E. king of Elam who briefly ruled Babylon." ("Finding Historical Memories in the Patriarchal Narratives" by Ronald Hindel, ''BAR'', Jul/Aug 1995) | |||

| ] at ], Israel]] | |||

| In the early and middle 20th century, leading archaeologists such as ] and ] and biblical scholars such as ] and ] believed that the patriarchs and matriarchs were either real individuals or believable composites of people who lived in the "]", the 2nd millennium BCE.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Bright|first=John|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0VG67yLs-LAC&q=Abraham|title=A History of Israel|date=1959|publisher=Westminster John Knox Press|isbn=978-0-664-22068-6|page=93|language=en}}</ref> But, in the 1970s, new arguments concerning Israel's past and the biblical texts challenged these views; these arguments can be found in ]'s '']'' (1974),<ref>{{Cite book|last=Thompson|first=Thomas L.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=o91vmgEACAAJ&q=The+Historicity+of+the+Patriarchal+Narratives:+The+Quest+for+the+Historical+Abraham|title=The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives: The Quest for the Historical Abraham|date=1974|publisher=Gruyter, Walter de, & Company |isbn=9783110040968 |language=en}}</ref> and ]' '']'' (1975).<ref>{{Cite book|last=Seters|first=John Van|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MySUQgAACAAJ&q=Abraham+in+history+and+tradition|title=Abraham in History and Tradition|date=1975|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=978-0-300-01792-2}}</ref> Thompson, a literary scholar, based his argument on archaeology and ancient texts. His thesis centered on the lack of compelling evidence that the patriarchs lived in the 2nd millennium BCE, and noted how certain biblical texts reflected first millennium conditions and concerns. Van Seters examined the patriarchal stories and argued that their names, social milieu, and messages strongly suggested that they were ] creations.{{sfn|Moore|Kelle|2011|pp=18–19}} Van Seters' and Thompson's works were a ] in biblical scholarship and archaeology, which gradually led scholars to no longer consider the patriarchal narratives as historical.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Moorey|first=Peter Roger Stuart|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=e1x9Rs_zdG8C&q=A+Century+of+Biblical+Archaeology|title=A Century of Biblical Archaeology|date=1991|publisher=Westminster John Knox Press|isbn=978-0-664-25392-9|pages=153–154}}</ref> Some conservative scholars attempted to defend the Patriarchal narratives in the following years, but this has not found acceptance among scholars.<ref>{{harvnb|Dever|2001|p=98}}: "There are a few sporadic attempts by conservative scholars to "save" the patriarchal narratives as history, such as ] By and large, however, the minimalist view of Thompson's pioneering work, ''The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives'', prevails."</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Grabbe|first=Lester L.|editor1-first=H. G. M|editor1-last=Williamson |title=Understanding the History of Ancient Israel |url=https://britishacademy.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.5871/bacad/9780197264010.001.0001/upso-9780197264010-chapter-5|chapter=Some Recent Issues in the Study of the History of Israel|publisher=British Academy|year=2007|isbn=978-0-19-173494-6|language=en-US|doi=10.5871/bacad/9780197264010.001.0001|quote=The fact is that we are all minimalists – at least, when it comes to the patriarchal period and the settlement. When I began my PhD studies more than three decades ago in the USA, the 'substantial historicity' of the patriarchs was widely accepted as was the unified conquest of the land. These days it is quite difficult to find anyone who takes this view.}}</ref> By the beginning of the 21st century, archaeologists had stopped trying to recover any context that would make Abraham, Isaac or Jacob credible historical figures.{{sfn|Dever|2001|p=98 and fn.2}} | |||

| The ''Anchor Bible Dictionary'' suggests that the biblical account was in all probability derived from a text very closely related to the Chedorlaomer Tablets, and this in a publication which can be said to do at least a reasoably good job of getting good scholarship. The Chedorlaomer Tablets are thought to be from the 6th or 7th Century BCE, well after the time of Hammurabi, at roughly the time when Gen. through Deu. are thought to have come into their present form (e.g. see the ]). While Astour's identifications of the figures these tablets refer to is certainly open to question, he does cautiously support a link between them and Gen. 14:1. Hammurabi is never known to have campaigned near the Dead Sea at all, although his son had. Writes Astour, "This identification, once widely accepted, was later virtually abandoned, mainly because Hammurapi was never active in the West." The Chedorlaomer Tablets, then, appear to still be the closest archaeological parallel to the kings of the Eastern coalition mentioned in Gen. 14:1. The only problem is, that in all probability, they refer to kings that were from widely separated times, having conquered Babylon in different eras. Linguistically, it seems, there is little reason to reject the identification of Hammurabi with Amraphel, but the narrative does not make sense in light of modern archaeology when it is made. A number of scholars also say that the connection does not make sense on chronological grounds, since it would place Abram later than the traditional date, but on this, see the section on chronology below. | |||

| ==={{anchor|Renaming}} Origins of the narrative=== | |||

| If Gen. ch. 14 is a historical romance (cf., e.g., the ]), it is possible that a writer who lived in an exilic or post-exilic age (i.e. during or after the ]), and who was acquainted with Babylonian history, decided to enhance the greatness of Abraham by claiming his military success against the monarchs of the ] and ], the high esteem he enjoyed in Canaan, and the practical character displayed in his brief exchange with ]. The historical section of the article ] deals more extensively with the historicity of the meeting with Melchizedek. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Abraham's story, like those of the other patriarchs, most likely had a substantial oral prehistory{{sfn|Pitard|2001|p=27}} (he is mentioned in the ]<ref>{{Bibleverse|Ezekiel|33:24}}</ref> and the ]<ref>{{Bibleverse|Isaiah|63:16}}</ref>). As with ], Abraham's name is apparently very ancient, as the tradition found in the ] no longer understands its original meaning (probably "Father is exalted" – the meaning offered in , "Father of a multitude", is a ]).{{sfn|Thompson|2016|pp=23–24}} At some stage the ]s became part of the written tradition of the ]; a majority of scholars believe this stage belongs to the Persian period, roughly 520–320 BCE.{{sfn|Ska|2009|p=260}} The mechanisms by which this came about remain unknown,{{sfn|Enns|2012|p=26}} but there are currently at least two hypotheses.{{sfn|Ska|2006|pp=217, 227–28}} The first, called Persian Imperial authorisation, is that the post-Exilic community devised the Torah as a legal basis on which to function within the Persian Imperial system; the second is that the Pentateuch was written to provide the criteria for determining who would belong to the post-Exilic Jewish community and to establish the power structures and relative positions of its various groups, notably the priesthood and the lay "elders".{{sfn|Ska|2006|pp=217, 227–28}} | |||

| The completion of the Torah and its elevation to the centre of post-Exilic Judaism was as much or more about combining older texts as writing new ones – the final Pentateuch was based on existing traditions.{{sfn|Carr|Conway|2010|p=193}} In the ],<ref>{{bibleverse-nb||Ezek|33:24|niv}}</ref> written during the Exile (i.e., in the first half of the 6th century BCE), ], an exile in Babylon, tells how those who remained in Judah are claiming ownership of the land based on inheritance from Abraham; but the prophet tells them they have no claim because they do not observe Torah.{{sfn|Ska|2009|p=43}} The ]<ref>{{bibleverse-nb||Isaiah|63:16|niv}}</ref> similarly testifies of tension between the people of Judah and the returning post-Exilic Jews (the "]"), stating that God is the father of Israel and that Israel's history begins with the Exodus and not with Abraham.{{sfn|Ska|2009|p=44}} The conclusion to be inferred from this and similar evidence (e.g., ]), is that the figure of Abraham must have been preeminent among the great landowners of Judah at the time of the Exile and after, serving to support their claims to the land in opposition to those of the returning exiles.{{sfn|Ska|2009|p=44}} | |||

| Many scholars claim, on the basis of archaeological and philological evidence, that many stories in the Pentateuch, including the accounts about Abraham, ] were written under king ] (]) or king ] (]) in order to provide a historical framework for the monotheistic belief in Yahweh. Some scholars point out that the archives of neighboring countries with written records that survive, such as Egypt, Assyria, etc., show no trace of the stories of the Bible or its main characters before 650 BC/BCE. Such claims are detailed in "Who Were the Early Israelites?" by ], (William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, 2003). Another similar book by ] and ] is "The Bible Unearthed," (Simon and Schuster, New York, 2001). Even so, the Moabite Stele mentions king Omri of Israel, and many scholars draw parallels between the Egyptian pharaoh ] and the ] of the Bible (1 Ki. 11:40; 14:25; and 2 Chr. 12:2-9); and between the king David of the Bible, and a stone inscription from 835 BCE that appears to refer to "house of David"; although some would dispute the last two correspondences. | |||

| === Amorite origin hypothesis === | |||

| ==Dating and historicity== | |||

| According to ], the Book of Genesis portrays Abraham as having an ] origin, arguing that the patriarch's provenance from the region of ] as described in {{bibleverse|Genesis|11:31}} associates him with the territory of the Amorite homeland. He also notes parallels between the biblical narrative and the Amorite migration into the ] in the ].<ref>{{cite book |title=Yahweh and the Origins of Ancient Israel: Insights from the Archaeological Record |last=Amzallag |first=Nissim |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2023 |isbn=978-1-009-31478-7 |page=76 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qee-EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA76}}</ref> Likewise, some scholars like ] and Alice Mandell have argued that the biblical portrayal of the Patriarchs' lifestyle appears to reflect the Amorite culture of the 2nd millennium BCE as attested in texts from the ancient city-state of ], suggesting that the Genesis stories retain historical memories of the ancestral origins of some of the Israelites.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Future of Biblical Archaeology: Reassessing Methodologies and Assumptions |last=Fleming |first=Daniel E. |publisher=Eerdmans |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-8028-2173-7 |pages=193–232 |editor-last=Hoffmeier |editor-first=James K. |chapter=Genesis in History and Tradition: The Syrian Background of Israel's Ancestors, Reprise |editor-last2=Millard |editor-first2=Alan R. |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PUcs-FQv4uIC&pg=PA193}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=The Cambridge Companion to Genesis |last=Mandell |first=Alice |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2022 |isbn=978-1-108-42375-5 |pages=143–46 |editor-last=Arnold |editor-first=Bill T. |chapter=Genesis and its Ancient Literary Analogues |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-EpgEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA143}}</ref> ] argues that the name Abram is of ] origin and that it is attested in Mari as ''ʾabī-rām''. He also suggests that the Patriarch's name corresponds to a form typical of the Middle Bronze Age and not of later periods.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Patriarchal Names in Context |journal=Tyndale Bulletin |last=Millard |first=Alan |volume=75 |issue=December |pages=155–174 |year=2024 |doi=10.53751/001c.117657 |issn=2752-7042 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===Traditional dating=== | |||

| According to calculations directly derived from the ] Hebrew ], Abraham was born 1,948 years after ] and lived for 175 years (Genesis 25:7), which would correspond to a life spanning from 1812 BC/BCE to 1637 BC/BCE by ]; or from 2166 BC/BCE to 1991 BC/BCE by other{{fact}} calculations. The figures in the ] have Abraham born 1,876 years after creation, and 534 years before the ]; the ages provided in the ] agree closely with those of Jubilees before the ], but after the Deluge, they add roughly 100 years to each of the ages of the Patriarchs in the Masoretic Text, resulting in the figure of 2,247 years after creation for Abraham's birth. The Greek ] version adds around 100 years to nearly all of the patriarchs' births, producing the even higher figure of 3,312 years after creation for Abraham's birth.] | |||

| ===Palestine origin hypothesis=== | |||

| === History of dating attempts === | |||

| The earliest possible reference to Abraham may be the name of a town in the ] listed in a victory inscription of Pharaoh ] (biblical ]), which is referred as "the Fortress of Abraham", suggesting the possible existence of an Abraham tradition in the 10th century BCE.{{sfn|McCarter|2000|p=9}} The orientalist ] proposed to see in the name Abraham the mythical eponym of a Palestinian tribe from the 13th century BCE, that of the Raham, of which mention was found in the stele of ] found in ] and dating back to 'around 1289 BCE.<ref>The stele reads: «The Apiru of Mount Yarumta, together with the Tayaru, attack the Raham tribe». J. B. Pritchard (ed.), Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, p. 255. Princeton, 1955.</ref> The tribe probably lived in the area surrounding or close to ], in ] (the stele in fact refers to fights that took place in the area). The semi-nomadic and pastoral Semitic tribes of the time used to prefix their names with the term banū ("sons of"), so it is hypothesized that the Raham called themselves Banu Raham. Furthermore, many interpreted blood ties between tribe members as common descent from an eponymous ancestor (i.e., one who gave the tribe its name), rather than as the result of intra-tribal ties. The name of this eponymous mythical ancestor was constructed with the patronymic (prefix) Abū ("father"), followed by the name of the tribe; in the case of the Raham, it would have been Abu Raham, later to become Ab-raham, Abraham. Abraham's Journey from Ur to Harran could be explained as a retrospective reflection of the story of the return of the Jews from the Babylonian exile. Indeed, ] suggested that the oldest Abraham traditions originated in the Iron Age (monarchic period) and that they contained an ] hero story, as the oldest mentions of Abraham outside the book of Genesis ( and ): do not depend on Genesis 12–26; do not have an indication of a Mesopotamian origin of Abraham; and present only two main themes of the Abraham narrative in Genesis—land and offspring.<ref name=":82">{{cite journal |title=Comments on the Historical Background of the Abraham Narrative: Between "Realia" and "Exegetica" |journal=Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel |url=https://www.academia.edu/29972948 |last1=Finkelstein |first1=Israel |issue=1 |volume=3 |pages=3–23 |last2=Römer |first2=Thomas |year=2014 |doi=10.1628/219222714x13994465496820}}</ref> Yet, unlike Liverani, Finkelstein considered Abraham as ancestor who was worshiped in Hebron, which is too far from Beit She'an, and the oldest tradition of him might be about the altar he built in Hebron.<ref name=":82" /> | |||

| == Religious traditions == | |||

| When cuneiform was first deciphered, Theophilus Pinches translated some Babylonian tablets which were part of the Spartoli collection in the British museum. In one, referred to as the Chedorlaomer Text, currently thought to have been written in the 6th to the 7th Century BCE, he believed that he recognized the names of three of the kings of the Eastern coalition fighting against the five kings from the Vale of Siddem in Gen. 1:14. In 1887, Schrader then was the first to propose that Amraphel could be an alternate spelling for Hammurabi (cf. the of 1915, s.v. "Hammurabi"). Vincent Scheil subsequently found a tablet in the Imperial Ottoman Museum in Constantinople from Hammurabi to a king of the very same name, i.e. Kuder-Lagomer, as in Pinches' tablet (see for a quote from a book by Zacheriah Sitchen on the subject, although Sitchen is by no means mainstream). Thus are achieved the following correspondences: | |||

| {{Judaism|1=figures}} | |||

| Abraham is given a high position of respect in three major world faiths, ], ], and ]. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the covenant, the special relationship between the Jewish people and God—leading to the belief that the ]. In Christianity, ] taught that Abraham's faith in God—preceding the ]—made him the prototype of all believers, Jewish or ]; and in Islam, he is seen as a link in the ] that begins with ] and culminates in ].{{sfn|Levenson|2012|p=8}} | |||

| ===Judaism=== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto" | |||

| In Jewish tradition, Abraham is called ''Avraham Avinu'' (אברהם אבינו), "our father Abraham," signifying that he is both the biological progenitor of the Jews and the father of Judaism, the first Jew.{{sfn|Levenson|2012|p=3}} His story is read in the weekly ] reading portions, predominantly in the ]: ] (לֶךְ-לְךָ), ] (וַיֵּרָא), ] (חַיֵּי שָׂרָה), and ] (תּוֹלְדֹת). | |||

| ! '''Name from Gen. 14:1''' | |||

| ! '''Name from Archaeology''' | |||

| |- align="center" | |||

| | ] king of Shinar (=Sumer via Aramaic) | |||

| | ] (="Ammurapi") king of ] (i.e. Babylonia) | |||

| |- align="center" | |||

| | ] king of ] | |||

| | Eri-aku king of Larsa (i.e. ]) | |||

| |- align="center" | |||

| | ] king of ] (= "Chedorlagomer" in the ]) | |||

| | Kudur-Lagamar king of Elam | |||

| |- align="center" | |||

| | Tidal, king of nations (i.e. ''goyim'', lit. 'gentiles') | |||

| | Tudhulu, son of Gazza | |||

| |} | |||

| ] taught in ]'s name that Abraham's mother was named ʾĂmatlaʾy bat Karnebo.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Bava Batra 91a|url=https://www.sefaria.org/Bava_Batra.91a|access-date=2021-03-08|website=www.sefaria.org}}</ref>{{Efn|MSS variants: ''bat Barnebo, bat bar-Nebo, bar-bar-Nebo, bat Karnebi, bat Kar Nebo''. Karnebo (''outpost of ]'') is attested as a ]ian theophoric place-name in ] inscriptions, including the ]. It referred to at least two separate cities in antiquity.<ref>Yamada, Shigeo. "</ref> Rabbinic tradition connects Karnebo to the ] Kar (כר ''lamb''), translating it ''] lambs''.<ref>. http://www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2021-03-08.</ref>}} ] taught that ] in his youth.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Bereishit Rabbah 38|url=https://www.sefaria.org/Bereishit_Rabbah.38|access-date=2021-03-11|website=www.sefaria.org}}</ref> | |||

| Many scholars by 1915 had become largely convinced that the kings of Gen. 14:1 had been identified (cf. again the of 1915, s.v. Hammurabi, which mentions the identification as doubtful, and also of 1917, s.v. "Amraphel", and Donald A. MacKenzie's 1915 , who has (p. 247) "The identification of Hammurabi with Amraphel is now generally accepted"). The terminal ''-bi'' on the end of Hammurabi's name was seen to parallel Amraphel since the cuneiform symbol for ''-bi'' can also be pronounced ''-pi''. Tablets were known in which the initial symbol for Hammurabi, pronounced as ''kh'' to yield ''Khammurabi'', had been dropped, such that ''Ammurapi'' was a viable pronunciation. Supposing him to have been deified in his lifetime or afterwards yielded Ammurabi-il, which was suitable close to the Bible's Amraphel. | |||

| In '']'', God created heaven and earth for the sake of the merits of Abraham.{{sfn|Ginzberg|1909|loc=Vol I: The Wicked Generations}} After the ], Abraham was the only one among the pious who solemnly swore never to forsake God,{{sfn|Ginzberg|1909|loc=Vol. I: In the Fiery Furnace}} studied in the house of ] and ] to learn about the "Ways of God,"{{sfn|Jasher|1840|p=22|loc =Ch9, vv 5–6}} continued the line of ] from Noah and Shem, and assigning the office to ] and ] forever. Before leaving his father's land, Abraham was miraculously saved from the fiery furnace of ] following his brave action of breaking the idols of the ]ns into pieces.{{sfn|Ginzberg|1909}} During his sojourning in Canaan, Abraham was accustomed to extend hospitality to travelers and strangers and taught how to praise God also knowledge of God to those who had received his kindness.{{sfn|Ginzberg|1909|loc=Vol. I: The Covenant with Abimelech}} | |||

| Archaeology subsequently discovered that the Babylonian king lists had been padded in a later era with extra names, and Albright was instrumental in synchronizing Hammurabi with Assyrian and Egyptian contemporaries, such that Hammurabi is now thought to have lived centuries later. Since many ecumenical theologians may not hold that the dates of the Bible could be in error, they began synchronizing Abram with the empire of Sargon on chronological grounds, and the work of Schrader, Pinches and Scheil fell out of favor with them. The objection resurfaced that Amraphel could not derived from ''Khammurabi'', in spite of the ''Ammurabi''/''Ammurapi'' spelling for Hammurabi that had already been found. More substantial objections were later made, including the finding that the days of the Kuder-Lagomer of Hammurabi's letter preceded the writing of the letter early in Hammurabi's reign led some to speculate that the Kuder-Lagomer of Gen. 14:1 should be associated with later Hittite or Akkadian kings with similar names, and these scholars thus generally considered the passage anachronistic - the product of a much later period, such as during or after the ]. Others pointed out that the Lagomer of Kuder-Lagomer was an Elamite deity's name, instead of the king's actual name, which some believe referred to a king that must have preceded Hammurabi. Other misreadings of the Chedorlaomer Text were pointed out, causing them to be associated with entirely different personages known from archaeology. It seemed that the theory of Schrader, Pinches and Scheil had fallen utterly apart. | |||

| Along with ] and ], he is the one whose name would appear united with God, as ] was called ''Elohei Abraham, Elohei Yitzchaq ve Elohei Ya'aqob'' ("God of Abraham, God of Isaac, and God of Jacob") and never the God of anyone else.{{sfn|Ginzberg|1909|loc=Vol. I: Joy and Sorrow in the House of Jacob}} He was also mentioned as the father of thirty nations.{{sfn|Ginzberg|1909|loc=Vol. I: The Birth of Esau and Jacob}} | |||

| Mainstream scholarship in the course of the 20th century has given up attempts to identify Abraham and his contemporaries in Genesis with historical figures.<ref>The Encyclopedia Britannica{{fact}}<!--2006?--> article on "Amraphel" has: "Scholars of previous generations tried to identify these names with important historical figures—e.g., Amraphel with Hammurabi of Babylon—but little remains today of these suppositions."</ref> While it is widely admitted that there is no archaeological evidence to prove the existence of Abraham, apparent parallels to Genesis in the archaeological record assure that speculations on the patriarch's historicity and on the period that would best fit the account in Genesis remain alive in religious circles. | |||

| "The Herald of Christ's Kingdom" in (2001) implies a historical Abraham by stating "At one time it was popular to connect Amraphel, king of Shinar, with Hammurabi, king of Babylon, but now it is generally conceded that Hammurabi was much later than Abraham." | |||

| Abraham is generally credited as the author of the '']'', one of the earliest extant books on ].<ref>''Sefer Yetzirah Hashalem'' (with Rabbi Saadia Gaon's Commentary), ] (editor), Jerusalem 1972, p. 46 (Hebrew / Judeo-Arabic)</ref> | |||

| There are two main eras with which Abram is usually associated by those postulating his historicity: that of king Sargon of the Sumerian Empire (ca. 2334–2279), and that of king ] (ca. 1792–50, middle chronology) and his son (ca. 1749-1712) of the Old Babylonian Empire.{{fact}} | |||

| According to ], Abraham underwent ten tests at God's command.<ref>Pirkei Avot 5:3 – עֲשָׂרָה נִסְיוֹנוֹת נִתְנַסָּה אַבְרָהָם אָבִינוּ עָלָיו הַשָּׁלוֹם וְעָמַד בְּכֻלָּם, לְהוֹדִיעַ כַּמָּה חִבָּתוֹ שֶׁל אַבְרָהָם אָבִינוּ עָלָיו הַשָּׁלוֹם</ref> The ] is specified in the Bible as a test;<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|22:1|GNT}}</ref> the other nine are not specified, but later rabbinical sources give various enumerations.{{citation needed|date=January 2022}} | |||

| A traditional chronology can be constructed from the ] as follows: If Solomon's temple was begun when most scholars put it, ca. 960-970 BCE, using e.g. 966, we get 1446 for the Exodus (I Ki. 6:1). There were 400 years reportedly spent in Egypt (Ex. 12:40), and then we only need add years from Jacob's going into Egypt to Abraham. So, we can add that Jacob was supposedly 130 when he came to Egypt (Gen. 47:9), Isaac was 60 years old when he had Jacob (Gen. 25:26) and Abraham was 100 when Isaac was born, and we get 1446 + 400 + 130 + 60 + 100 = 2136 BCE for Abram's birth. (A considerable variety of scriptural chronologies are possible, however.) Thus, if one adheres to an Early Exodus theory, then Abram is usually synchronized with ], or sometimes other figures in the Sumerian Empire. If one favors a Late Exodus theory, we should subtract roughly two centuries, and then Abraham's life would overlap that of Hammurabi's empire (died at 175 years, cf. Gen. 25:7, so 2135 - 175 - 200 = 1761). | |||

| ===Christianity=== | |||

| Gen. 10:10 has it that Babel was the beginning of Nimrod's empire. Since Sargon's capitol city, Agade, has not yet been found, it is easy to suppose that Nimrod was not Hammurabi, that there is a remote chance that Agade is Babel, or that somehow Bable got substituted for Agade somewhere along the way. Even so, there are reasons to prefer the equation of Hammurabi with Amraphel. The Nimrod of Gen. ch. 10 precedes the Amraphel of ch. 14, and Nimrod's kingdom began with "Babylon, Erech, Akkad, and Calneh, in Shinar" (Gen. 10:10). Mentions of Nimrod both precede and follow those of Abram. Furthermore, Nimrod is associated with the Tower of Babel, not the Tower of Agade, in the Bible. Rabinnic materials are full of an account of Abram being thrown into the furnace used for making bricks for the Tower of Babel by Nimrod, but Abram was miraculously unharmed, while the furnace spread to the rest of the city, causing the "Fire of the Chasdim". It seems safe to conclude that Nimrod and Abram were more or less contemporaries. While it is easy to hypothesize that Agade was Babylon, the Britannica says that Babylon was a vassal kingdom during this period, and only during the time of Hammurabi did it become the beginning of an Empire in its own right (s.v. "Babylon", whereas the city of Babel = Babylon); and so we can conclude that Babylon was probably ''not'' the same as the Sumerian capitol. This surely matches the biblical description of Nimrod's empire far better. If we wish to belabor that Gen. ch. 14 still retains any historical authenticity, the Old Babylonian Empire, like Nimrod's, extended into the Trans-Jordan, but only during the reign of Hammurabi's son; whereas the Sumerian Empire by contrast did not. The city of Babel was not only the beginning of the Old Babylonian Empire, it was its capitol. After the end of the Old Babylonian Empire with the defeat of Hammurabi's son by the Elamites, there was not another empire ruled from the city of Babel until the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which was much too late to be synchronized with Abraham. True, the capitol of the Kassite Empire was near the city of Babel, but the Britannica has it that it was not ruled from Babel itself; and synchronizing Abram with the Kassite Empire would only compound the problem by requiring Abram to have lived even more recently. | |||

| {{Infobox saint | |||

| |name = Abraham | |||

| |feast_day = 9 October – ] and ]<ref name="LCMS">{{cite web |title=Commemorations |url=https://www.lcms.org/worship/church-year/commemorations |publisher=] |access-date=31 October 2020 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| |venerated_in = {{hlist <!--chronological:-->|] |] |] |]<ref name="Hitti 1928 37" /><ref name="Dana 2008 17" /> |]}} | |||

| |image = Aert de Gelder 009.jpg | |||

| |imagesize = 240px | |||

| |caption = ''Abraham and the Angels'', by ], {{circa|1680–85}} (], Rotterdam) | |||

| |titles = First Patriarch | |||

| }} | |||

| In ], Abraham is revered as the ] to whom God chose to reveal himself and with whom God initiated a ] (cf. '']'').{{sfn|Wright|2010|p=72}}<ref name="WaReMu">{{harvnb|Waters|Reid|Muether|2020|ps=: "Paul also shows us how the Abrahamic covenant relates to the covenantal administrations that precede and follow it. ... There is, then, covenantal continuity between the inaugural administration of God's one gracious covenant in the garden of Eden (Gen. 3:15) and the subsequent administration of that covenant to Abraham and his family (Gen. 12; 15; 17). The Abrahamic administration serves to reveal more of the person and work of Christ and, in this way, continue to administer Christ to human beings through faith."}}</ref> ] declared that all who believe in Jesus (]) are "included in the seed of Abraham and are inheritors of the promise made to Abraham."{{sfn|Wright|2010|p=72}} In ] 4, Abraham is praised for his "unwavering faith" in God, which is tied into the concept of partakers of the covenant of grace being those "who demonstrate faith in the saving power of Christ".<ref>Firestone, Reuven. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170909233637/http://cmje.usc.edu/articles/abraham.php |date=9 September 2017 }} ''Encyclopedia of World History''.</ref><ref name="WaReMu" /> | |||